Submitted:

17 January 2025

Posted:

20 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

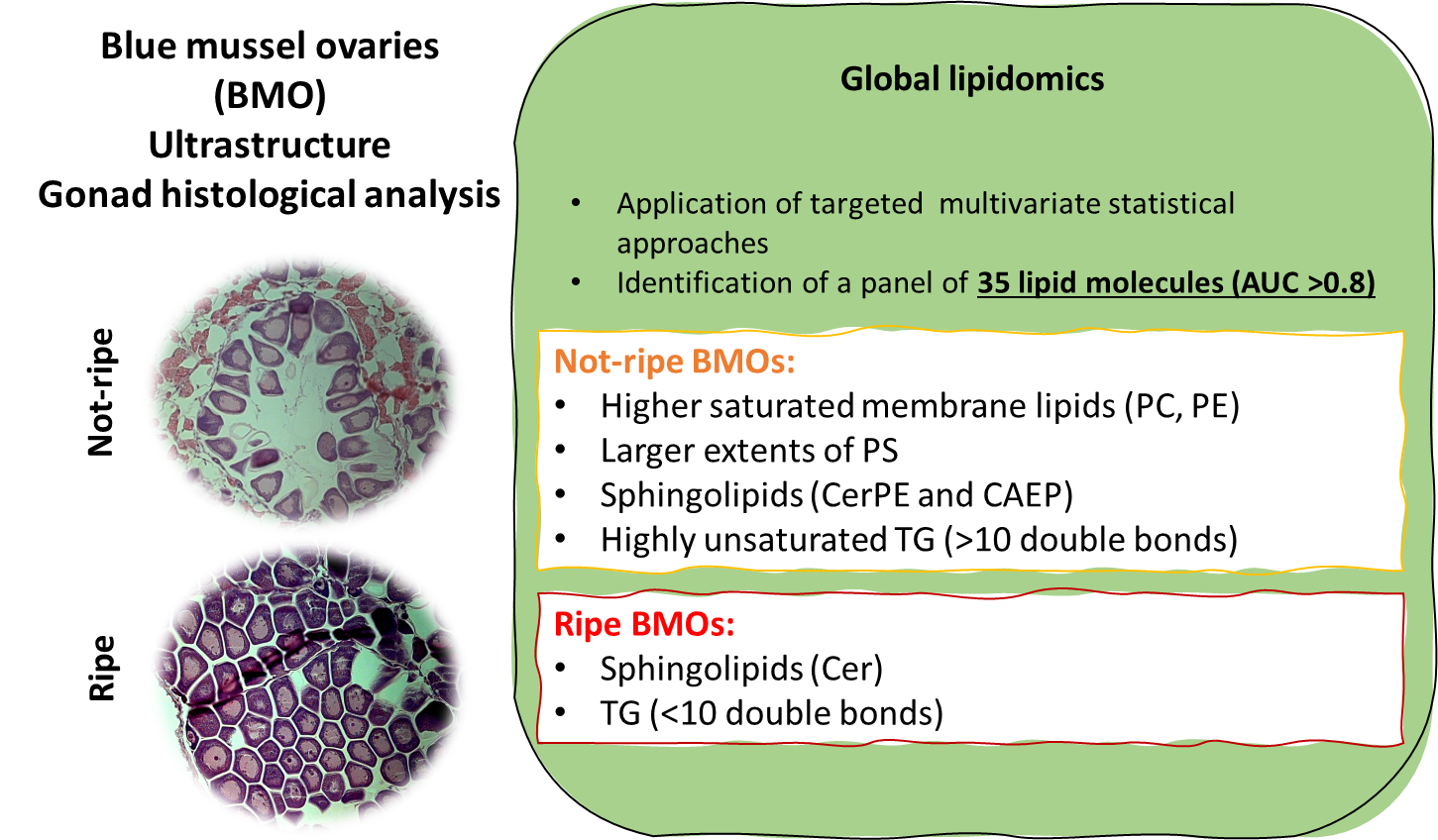

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mussels Collection and Sample Preparation

2.2. Histological Analyses

2.3. Lipid Extraction

2.4. LC-MS Untargeted Lipidomics

2.5. Data Processing

2.6. Data Analysis

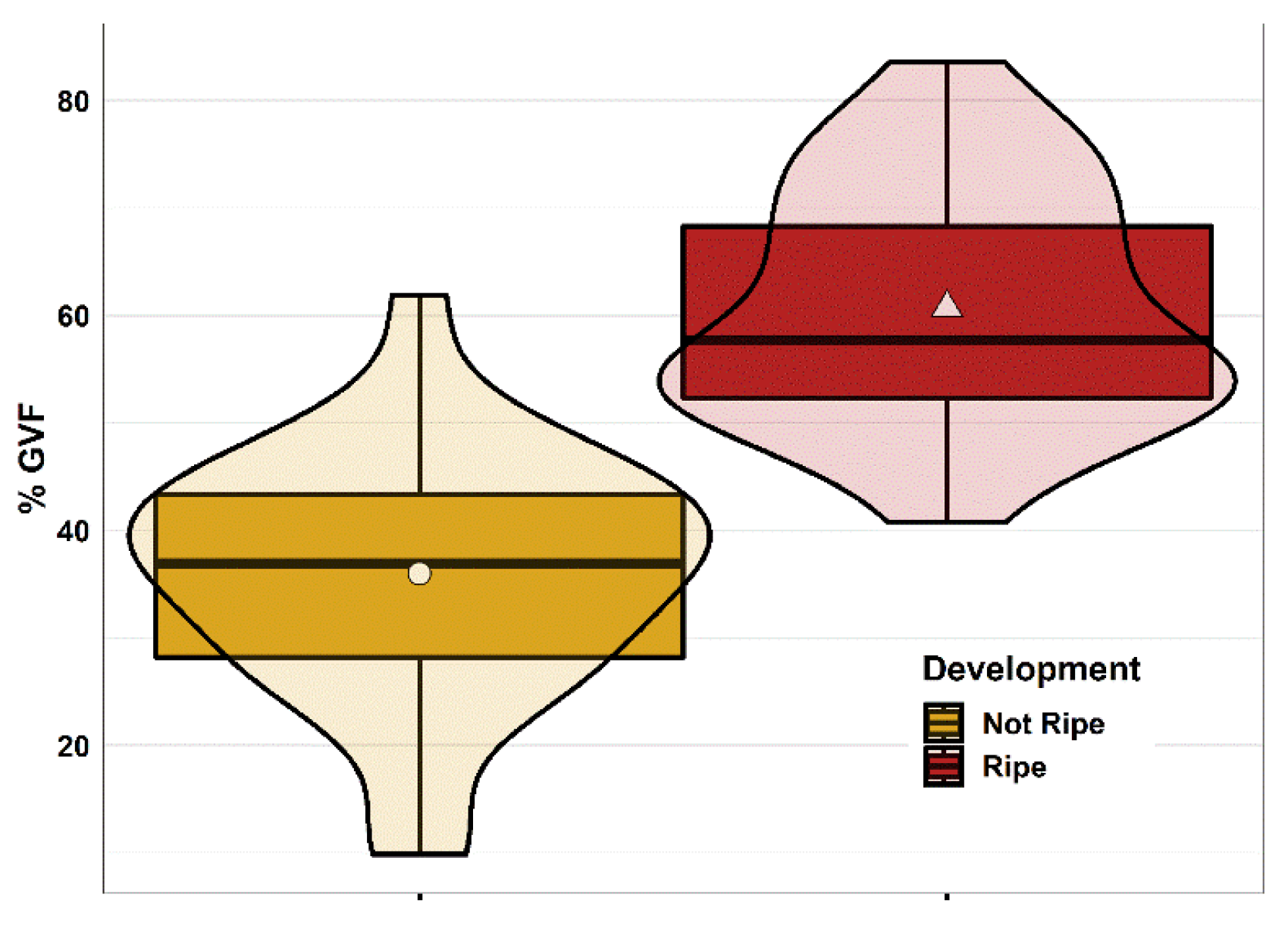

3. Results and Discussion

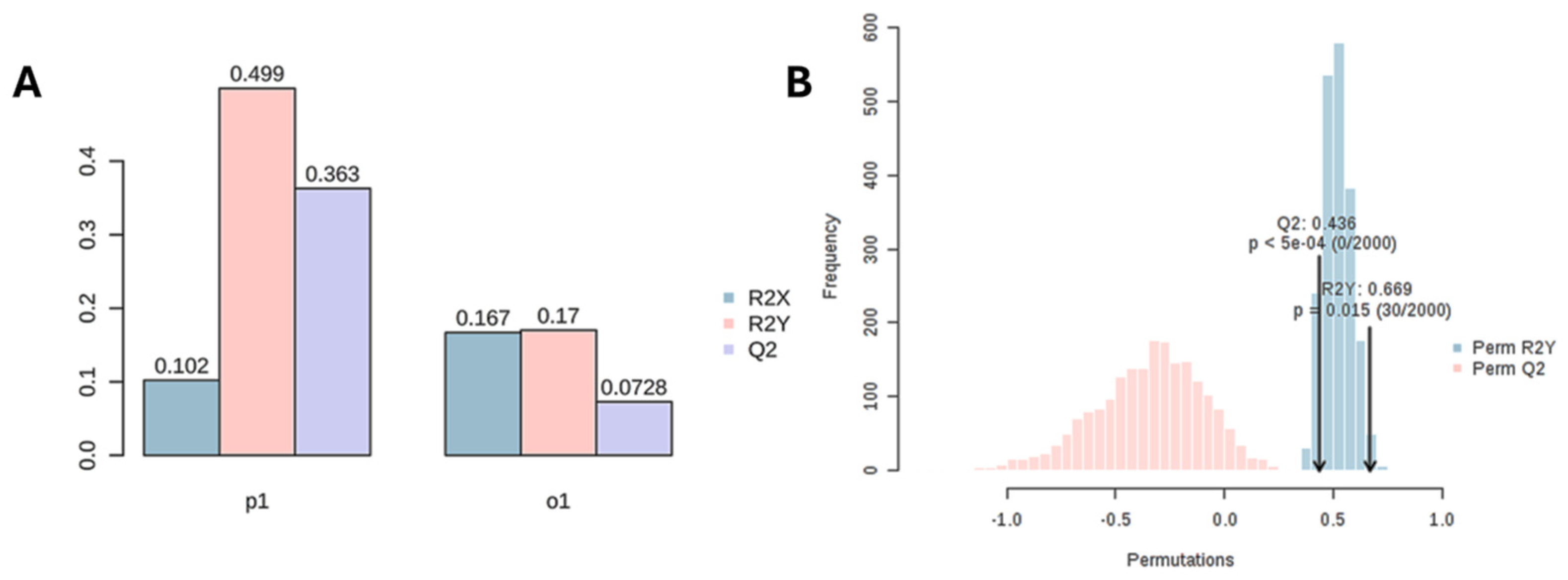

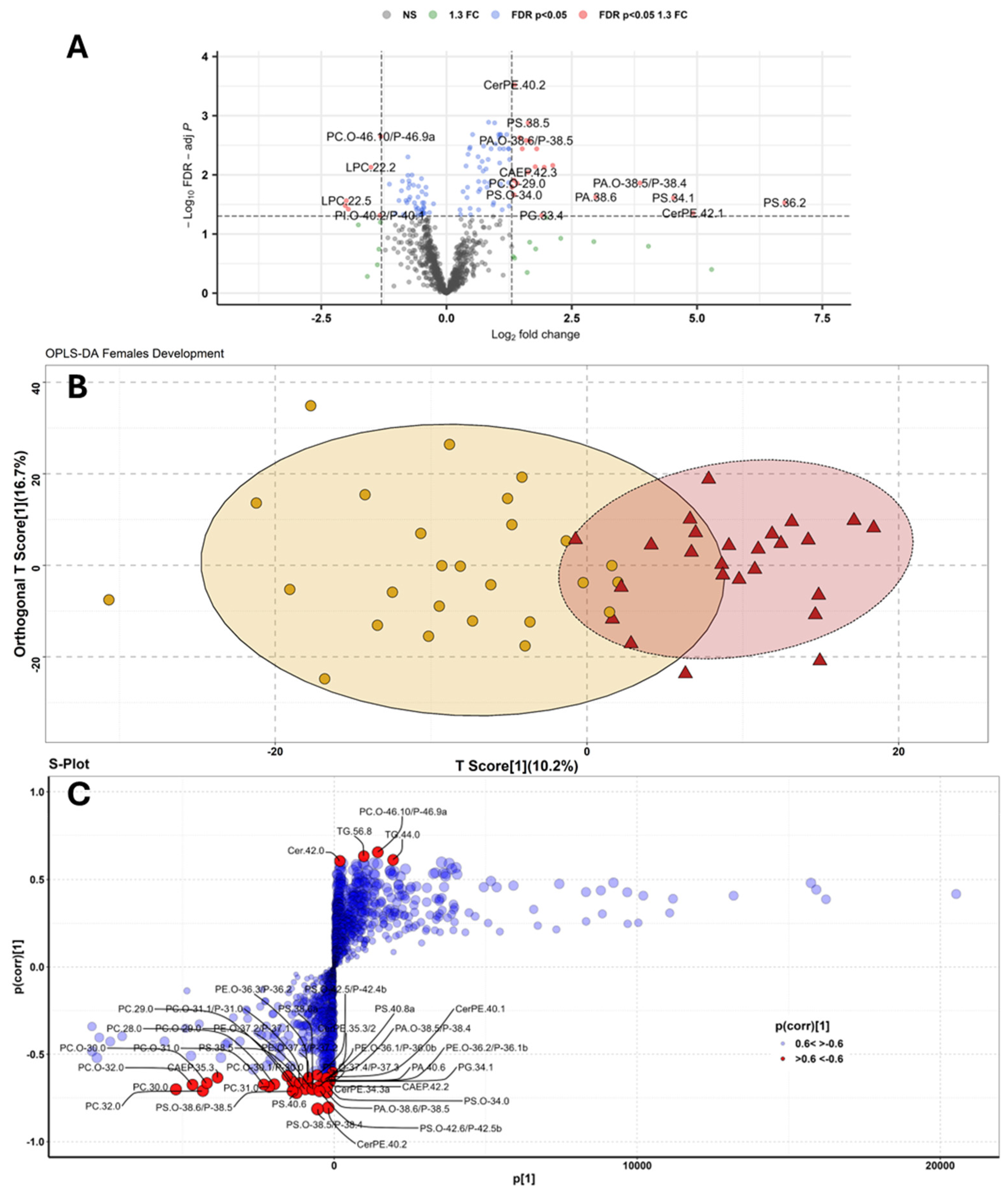

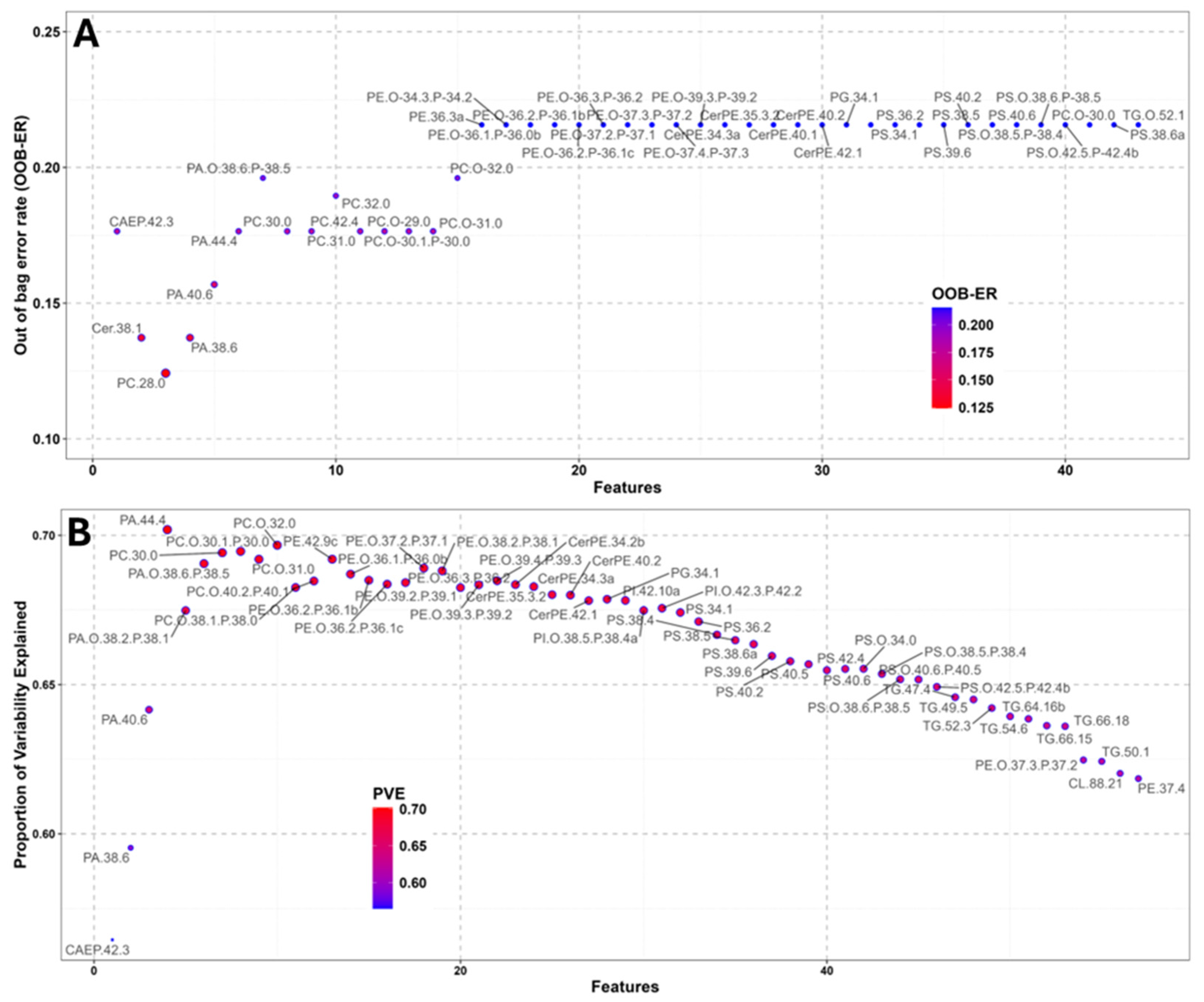

3.1. Multivariate Chemometrics

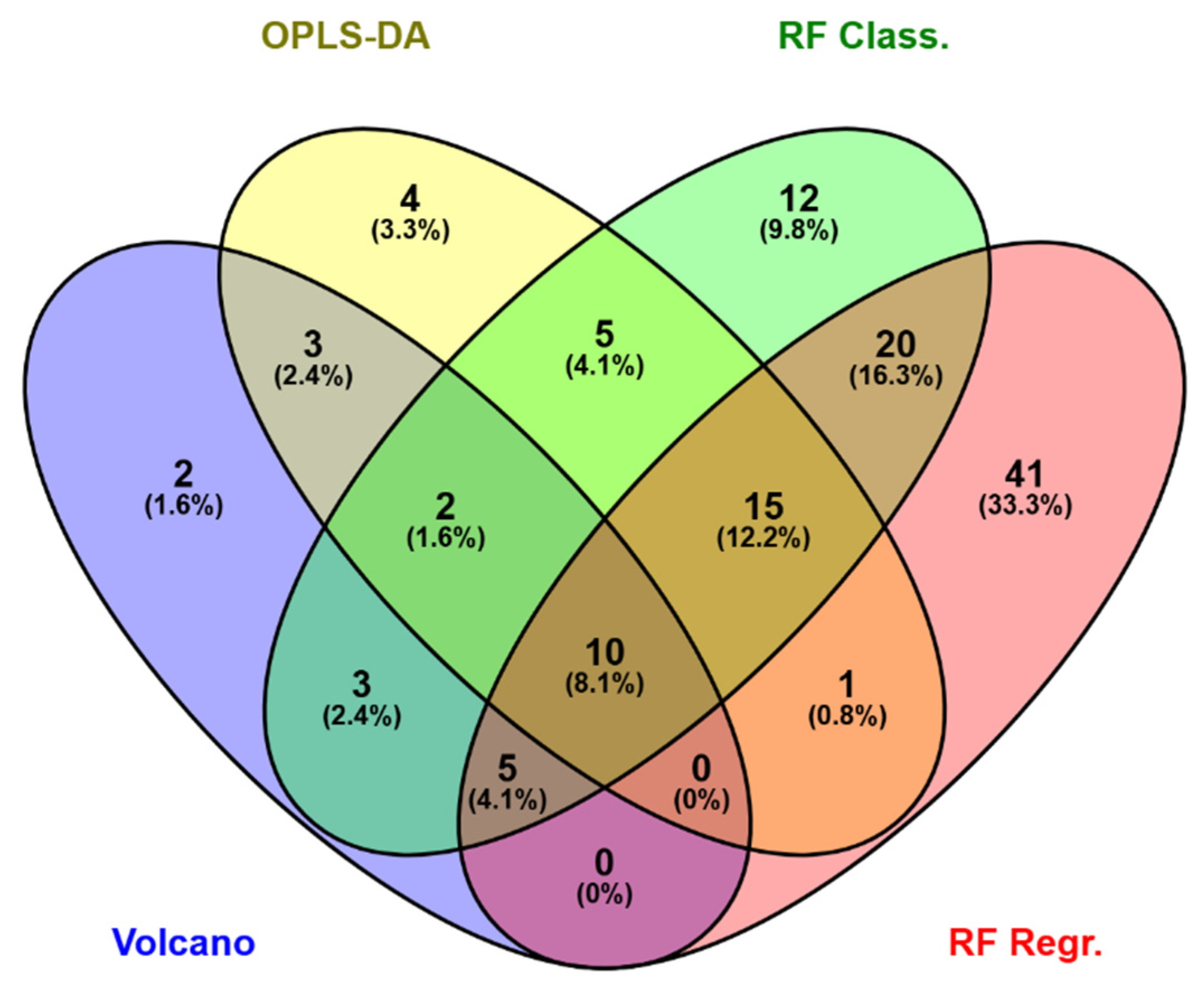

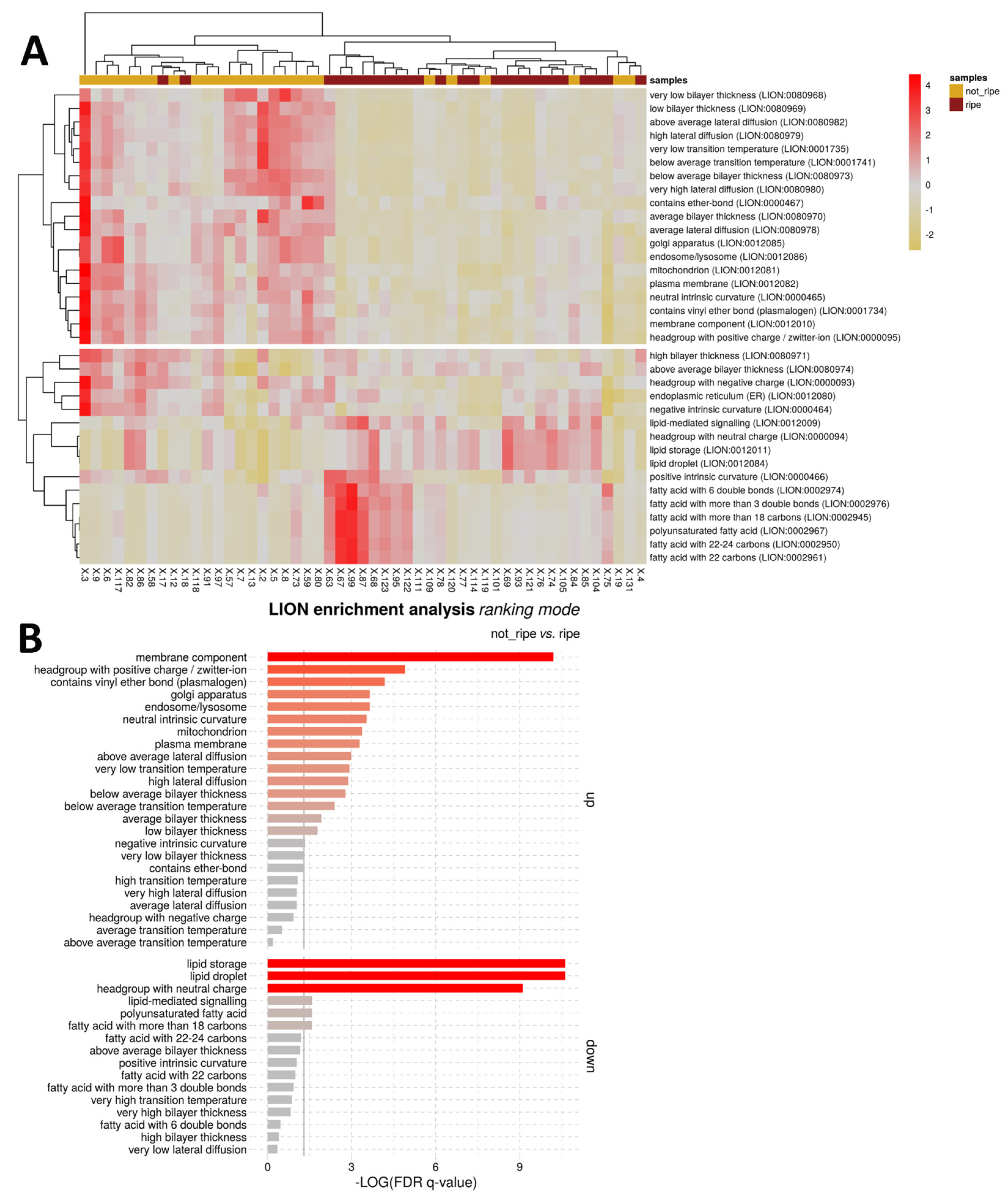

3.2. Comparison of the Outputs Obtained by the Different Statisatical Approaches

3.4. Ranking the Panel of Potential Biomarkers

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Lipid ID | AUC | Pval | FC | r | Volcano | OPLS-DA | RFclass | RFreg | Not-Ripe | Ripe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average ± CI (95%) | Average ± CI (95%) | |||||||||

| CAEP.35.3 | 0.74 | <0.01 | 0.39 | -0.48 | x | x | 1855.96 ± 247.94 | 1393.62 ± 125.7 | ||

| CAEP.42.2 | 0.81 | <0.01 | 1.58 | -0.60 | x | x | x | 47.59 ± 9.06 | 20.67 ± 7.5 | |

| CAEP.42.3 | 0.8 | <0.01 | 3.13 | -0.56 | x | x | x | 36.95 ± 11.25 | 11.19 ± 6.08 | |

| Cer.36.2a | 0.58 | 0.09 | 0.21 | -0.10 | x | 267.81 ± 60.62 | 224.45 ± 23.52 | |||

| Cer.38.1 | 0.76 | <0.01 | -0.99 | 0.38 | x | 47.24 ± 13.18 | 75.37 ± 14.06 | |||

| Cer.42.0 | 0.76 | <0.01 | -0.5 | 0.51 | x | 61.06 ± 8.32 | 87.2 ± 11.11 | |||

| CerPE.34.1 | 0.76 | <0.01 | 0.57 | -0.43 | x | 450.48 ± 85.69 | 277.56 ± 41.11 | |||

| CerPE.34.2b | 0.75 | <0.01 | 0.58 | -0.54 | x | 128.16 ± 22.58 | 84.28 ± 13.44 | |||

| CerPE.34.3a | 0.84 | <0.01 | 0.98 | -0.67 | x | x | x | 95.62 ± 20.84 | 48.43 ± 8.13 | |

| CerPE.35.3/2 | 0.87 | <0.01 | 1.08 | -0.67 | x | x | x | 132.82 ± 29.82 | 55.95 ± 7.87 | |

| CerPE.40.1 | 0.81 | <0.01 | 1.17 | -0.57 | x | x | x | 34.15 ± 7.02 | 13.71 ± 5.25 | |

| CerPE.40.2 | 0.9 | <0.01 | 1.48 | -0.74 | x | x | x | x | 46.4 ± 7.88 | 17.69 ± 4.48 |

| CerPE.42.1 | 0.8 | 0.01 | 5.5 | -0.53 | x | x | x | 7.66 ± 5.08 | 0.23 ± 0.45 | |

| CerPE.d44.2 | 0.79 | <0.01 | 0.73 | -0.52 | x | 52.96 ± 10.36 | 31.51 ± 4.19 | |||

| CL.88.21 | 0.56 | 0.68 | -0.3 | -0.05 | x | 39.63 ± 15.32 | 44.23 ± 15.59 | |||

| DG.32.1 | 0.59 | 0.2 | -0.21 | 0.17 | x | 1223.06 ± 217.88 | 1396.08 ± 272.03 | |||

| DG.33.2 | 0.56 | 0.43 | -0.13 | 0.18 | x | 254.51 ± 47.85 | 270.76 ± 52.22 | |||

| LPC.22.2 | 0.81 | <0.01 | -1.63 | 0.41 | x | x | 115.47 ± 39.6 | 308.4 ± 101.03 | ||

| LPC.22.5 | 0.76 | <0.01 | -2.39 | 0.42 | x | 65.26 ± 37.91 | 244.7 ± 114.32 | |||

| LPC.22.6 | 0.72 | <0.01 | -1.86 | 0.41 | x | x | 131.28 ± 61.4 | 497.37 ± 246.18 | ||

| LPE.22.6 | 0.61 | 0.22 | -0.73 | 0.22 | x | x | 27 ± 10.79 | 38.01 ± 18.64 | ||

| PA.38.6 | 0.82 | <0.01 | 5.66 | -0.54 | x | x | x | 12.45 ± 6.38 | 1.46 ± 1.54 | |

| PA.40.6 | 0.86 | <0.01 | 2.85 | -0.70 | x | x | x | x | 33.14 ± 12.05 | 8.31 ± 3.64 |

| PA.44.4 | 0.81 | <0.01 | -1.76 | 0.63 | x | x | 102.52 ± 41.73 | 226.25 ± 58.24 | ||

| PA.O-38.2/P-38.1 | 0.74 | 0.01 | 1.36 | -0.48 | x | x | 32.04 ± 6.9 | 20.2 ± 7.86 | ||

| PA.O-38.5/P-38.4 | 0.72 | <0.01 | 4.13 | -0.41 | x | x | 6.66 ± 3.71 | 1.22 ± 1.53 | ||

| PA.O-38.6/P-38.5 | 0.85 | <0.01 | 2.12 | -0.68 | x | x | x | x | 46.5 ± 13.09 | 15.64 ± 4.86 |

| PC.28.0 | 0.84 | <0.01 | 1.35 | -0.55 | x | x | x | x | 426.29 ± 119.56 | 140.95 ± 36.64 |

| PC.29.0 | 0.79 | <0.01 | 0.94 | -0.42 | x | 326.9 ± 78.46 | 150.35 ± 29.08 | |||

| PC.30.0 | 0.85 | <0.01 | 1.37 | -0.60 | x | x | x | x | 1149.26 ± 291.11 | 396.62 ± 108.82 |

| PC.31.0 | 0.76 | <0.01 | 0.66 | -0.36 | x | x | 706.06 ± 121.33 | 419.14 ± 60.12 | ||

| PC.32.0 | 0.78 | <0.01 | 0.95 | -0.51 | x | x | 1181.4 ± 230.72 | 572.94 ± 110.41 | ||

| PC.42.3 | 0.73 | 0.1 | -0.49 | 0.40 | x | x | 435.88 ± 121.3 | 582.86 ± 82.68 | ||

| PC.42.4 | 0.72 | <0.01 | -0.53 | 0.30 | x | x | 76.01 ± 13.45 | 104.97 ± 12.52 | ||

| PC.O-29.0 | 0.8 | <0.01 | 1.57 | -0.51 | x | x | x | 274.36 ± 86.89 | 97.24 ± 36.48 | |

| PC.O-30.0 | 0.8 | <0.01 | 1.48 | -0.54 | x | x | x | 862.53 ± 256.36 | 318.65 ± 112.49 | |

| PC.O-30.1/P-30.0 | 0.72 | <0.01 | 0.6 | -0.39 | x | x | x | 479.19 ± 98.68 | 292.4 ± 56.3 | |

| PC.O-30.2/P-30.1 | 0.69 | <0.01 | 0.68 | -0.31 | x | 489.48 ± 140.93 | 197.21 ± 62.1 | |||

| PC.O-31.0 | 0.8 | <0.01 | 1.37 | -0.55 | x | x | x | 68.9 ± 21.25 | 41.64 ± 9.75 | |

| PC.O-31.1/P-31.0 | 0.75 | <0.01 | 0.85 | -0.45 | x | 313.33 ± 66.93 | 170.76 ± 36.29 | |||

| PC.O-32.0 | 0.8 | <0.01 | 1.35 | -0.56 | x | x | x | x | 923.78 ± 291.49 | 351.64 ± 111.32 |

| PC.O-38.1/P-38.0 | 0.76 | <0.01 | -0.69 | 0.51 | x | 400.67 ± 74.02 | 634.91 ± 112.22 | |||

| PC.O-38.5/P-38.4 | 0.68 | 0.02 | -0.37 | 0.33 | x | 3158.87 ± 452.94 | 4126.82 ± 599.14 | |||

| PC.O-39.2/P-39.1 | 0.71 | 0.02 | -0.5 | 0.41 | x | 587.31 ± 109.84 | 964.5 ± 162.84 | |||

| PC.O-40.2/P-40.1 | 0.78 | <0.01 | -0.73 | 0.51 | x | x | 587.31 ± 109.84 | 964.5 ± 162.84 | ||

| PC.O-42.10/P-42.9a | 0.81 | <0.01 | -1.43 | 0.14 | x | x | x | x | 145.61 ± 41.99 | 341.56 ± 83.65 |

| PE.36.3a | 0.65 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.26 | x | 33 ± 6.89 | 43.8 ± 10.85 | |||

| PE.38.4a | 0.57 | 0.28 | 0.1 | -0.42 | x | x | 102.72 ± 14.62 | 96.79 ± 11.17 | ||

| PE.37.4 | 0.72 | 0.01 | 1.19 | -0.37 | x | 33.96 ± 9.79 | 17.15 ± 5.86 | |||

| PE.39.5 | 0.76 | <0.01 | 0.72 | -0.48 | x | x | 75.17 ± 13.77 | 39.58 ± 7.07 | ||

| PE.41.5 | 0.64 | 0.01 | 0.62 | -0.28 | x | 33.31 ± 12.76 | 16.49 ± 4.91 | |||

| PE.42.9c | 0.56 | 0.59 | -0.22 | 0.23 | x | 185.63 ± 49.07 | 193.23 ± 41.74 | |||

| PE.O-34.3/P-34.2 | 0.83 | 0.01 | 0.98 | -0.51 | x | x | 53.51 ± 20.01 | 24.5 ± 4.84 | ||

| PE.O-35.3/P-35.2 | 0.77 | 0.01 | 0.97 | -0.46 | x | 40.95 ± 14.52 | 18.98 ± 4.37 | |||

| PE.O-36.1/P-36.0b | 0.87 | <0.01 | 1.63 | -0.74 | x | x | x | x | 65.23 ± 19.65 | 21.09 ± 4.88 |

| PE.O-36.1/P-36.0c | 0.77 | <0.01 | 0.88 | -0.58 | x | 91.33 ± 25.83 | 41.6 ± 7.31 | |||

| PE.O-36.2/P-36.1b | 0.85 | <0.01 | 0.96 | -0.62 | x | x | x | 94.97 ± 22.76 | 47.13 ± 7.8 | |

| PE.O-36.2/P-36.1c | 0.88 | <0.01 | 0.97 | -0.73 | x | x | 251.77 ± 50.85 | 121.82 ± 15.8 | ||

| PE.O-36.3/P-36.2 | 0.85 | <0.01 | 0.61 | -0.58 | x | x | 308.04 ± 55.87 | 193.04 ± 19.3 | ||

| PE.O-37.2/P-37.1 | 0.86 | <0.01 | 0.99 | -0.71 | x | x | x | 231.1 ± 39.56 | 121.75 ± 21.86 | |

| PE.O-37.3/P-37.2 | 0.84 | <0.01 | 0.51 | -0.55 | x | x | x | 428.34 ± 49.7 | 300.34 ± 26.36 | |

| PE.O-37.4/P-37.3 | 0.87 | <0.01 | 0.74 | -0.40 | x | x | x | 84.17 ± 14.05 | 50.25 ± 6.82 | |

| PE.O-38.2/P-38.1 | 0.8 | <0.01 | 0.63 | -0.62 | x | x | 627.28 ± 92.01 | 407.74 ± 58.2 | ||

| PE.O-38.3/P-38.2 | 0.78 | <0.01 | 0.38 | -0.52 | x | 1411.67 ± 151.08 | 1084.61 ± 86.66 | |||

| PE.O-39.2/P-39.1 | 0.73 | <0.01 | 0.51 | -0.47 | x | 125.68 ± 18.84 | 92.57 ± 15.07 | |||

| PE.O-39.3/P-39.2 | 0.8 | <0.01 | 0.45 | -0.56 | x | x | 360.03 ± 39.86 | 264.36 ± 23.89 | ||

| PE.O-39.4/P-39.3 | 0.73 | <0.01 | 0.38 | -0.38 | x | x | 194.69 ± 27 | 146.64 ± 13.67 | ||

| PE.O-40.7/P-40.6b | 0.67 | 0.07 | -0.24 | 0.35 | x | 886.89 ± 125.56 | 1034.58 ± 117.48 | |||

| PE.O-41.4/P-41.3 | 0.65 | 0.04 | 0.25 | -0.33 | x | 110.58 ± 15.74 | 92.1 ± 9.6 | |||

| PG.34.1 | 0.86 | <0.01 | 2.19 | -0.70 | x | x | x | x | 25.61 ± 8.8 | 7.32 ± 2.83 |

| PI.40.3 | 0.62 | 0.05 | -0.28 | 0.21 | x | 294.18 ± 38.48 | 350.62 ± 36.02 | |||

| PI.40.4 | 0.65 | 0.04 | -0.39 | 0.32 | x | 266.66 ± 45.88 | 331.8 ± 43.8 | |||

| PI.40.8 | 0.71 | 0.01 | -0.39 | 0.47 | x | x | 118.42 ± 14.83 | 147.88 ± 16.72 | ||

| PI.41.5 | 0.6 | 0.26 | -0.2 | 0.33 | x | 102.64 ± 16.24 | 115.25 ± 13.04 | |||

| PI.41.6 | 0.74 | <0.01 | -0.49 | 0.54 | x | 103.73 ± 14.79 | 140.82 ± 13.95 | |||

| PI.42.3 | 0.79 | <0.01 | -0.95 | 0.53 | x | x | 45.08 ± 10.05 | 78.71 ± 12.29 | ||

| PI.42.10a | 0.71 | 0.02 | -0.71 | 0.43 | x | 27.67 ± 6.84 | 41.65 ± 10.88 | |||

| PI.44.7 | 0.61 | 0.03 | -0.61 | 0.22 | x | 11.63 ± 4.06 | 26.72 ± 12.24 | |||

| PI.O-38.5/P-38.4a | 0.76 | <0.01 | 1.03 | -0.59 | x | 55.34 ± 11.27 | 30.46 ± 8.17 | |||

| PI.O-40.2/P-40.1 | 0.73 | 0.01 | -1.37 | 0.35 | x | 16.8 ± 6.25 | 44.17 ± 17.7 | |||

| PS.34.1 | 0.8 | <0.01 | 6.82 | -0.54 | x | x | x | 13.17 ± 7.65 | 0.53 ± 0.75 | |

| PS.36.2 | 0.81 | <0.01 | 7.06 | -0.56 | x | x | x | 16.21 ± 10.11 | 0.14 ± 0.22 | |

| PS.38.2a | 0.64 | 0.1 | -0.42 | 0.32 | x | 55.04 ± 12.89 | 68.49 ± 13.29 | |||

| PS.38.4 | 0.64 | 0.03 | 1.55 | -0.35 | x | 27.56 ± 19.08 | 5.6 ± 1.94 | |||

| PS.38.5 | 0.89 | <0.01 | 1.61 | -0.71 | x | x | x | x | 215.46 ± 51.5 | 66.38 ± 17.26 |

| PS.38.6a | 0.84 | <0.01 | 1.23 | -0.60 | x | x | x | 164.04 ± 40.39 | 66.94 ± 16.21 | |

| PS.39.6 | 0.82 | <0.01 | 1.21 | -0.55 | x | x | 96.45 ± 35.18 | 39.88 ± 10.52 | ||

| PS.40.2 | 0.83 | <0.01 | 0.75 | -0.68 | x | x | 157.85 ± 32.77 | 91.97 ± 13.65 | ||

| PS.40.5 | 0.82 | <0.01 | 1.52 | -0.67 | x | 41.86 ± 11.05 | 18.17 ± 5.55 | |||

| PS.40.6 | 0.89 | <0.01 | 1.06 | -0.74 | x | x | x | 329.08 ± 66.25 | 155.36 ± 27.89 | |

| PS.40.8a | 0.78 | <0.01 | 4 | -0.46 | x | x | 46.14 ± 17.07 | 9.88 ± 4.45 | ||

| PS.42.3b | 0.6 | 0.26 | 0.11 | -0.25 | x | 82.48 ± 17.25 | 72.17 ± 12.55 | |||

| PS.42.4 | 0.61 | 0.03 | 0.3 | -0.23 | x | 265.25 ± 70.08 | 188.69 ± 29.82 | |||

| PS.O-34.0 | 0.78 | <0.01 | 1.45 | -0.58 | x | x | 41.47 ± 14.23 | 15.36 ± 4.76 | ||

| PS.O-38.1/P-38.0 | 0.58 | 0.15 | -0.41 | 0.03 | x | 49.83 ± 10.01 | 59.14 ± 5.8 | |||

| PS.O-38.2/P-38.1 | 0.7 | 0.04 | 0.41 | -0.44 | x | 403.79 ± 54.5 | 327.41 ± 58.89 | |||

| PS.O-38.5/P-38.4 | 0.88 | <0.01 | 0.82 | -0.74 | x | x | x | 163.08 ± 24.44 | 94.22 ± 13.23 | |

| PS.O-38.6/P-38.5 | 0.86 | <0.01 | 0.99 | -0.67 | x | x | x | 361.75 ± 74.27 | 168.69 ± 30.8 | |

| PS.O-40.0 | 0.7 | 0.01 | -0.6 | 0.36 | x | 66.34 ± 12.97 | 88.35 ± 13.27 | |||

| PS.O-40.6/P-40.5 | 0.75 | <0.01 | 0.36 | -0.46 | x | x | 372.13 ± 29.19 | 294.14 ± 34.19 | ||

| PS.O-42.5/P-42.4b | 0.79 | <0.01 | 0.44 | -0.57 | x | x | x | 313.53 ± 31.31 | 233.07 ± 24.54 | |

| PS.O-42.6/P-42.5b | 0.79 | <0.01 | 0.45 | -0.52 | x | x | 226.36 ± 26.28 | 165.82 ± 14.05 | ||

| TG.44.0 | 0.76 | <0.01 | -0.77 | 0.49 | x | 371.86 ± 72.65 | 620.47 ± 120.92 | |||

| TG.46.4 | 0.78 | <0.01 | -0.91 | 0.52 | x | x | 389.78 ± 87.09 | 641.69 ± 122.92 | ||

| TG.47.4 | 0.78 | <0.01 | -1.01 | 0.56 | x | 233.64 ± 57.24 | 399.27 ± 78.14 | |||

| TG.49.4 | 0.74 | 0.01 | -0.61 | 0.55 | x | 898.38 ± 176.02 | 1280.61 ± 184.12 | |||

| TG.49.5 | 0.73 | 0.01 | -0.58 | 0.51 | x | 967.3 ± 181.85 | 1356.58 ± 186.94 | |||

| TG.50.1 | 0.73 | 0.01 | -0.56 | 0.46 | x | 3679.66 ± 783.32 | 4970.1 ± 532.03 | |||

| TG.51.7 | 0.68 | 0.05 | -0.43 | 0.46 | x | 803.73 ± 148.86 | 1007.24 ± 129.46 | |||

| TG.52.1b | 0.72 | <0.01 | -0.62 | 0.45 | x | 2349.98 ± 497.12 | 3209.19 ± 324.5 | |||

| TG.52.2 | 0.73 | 0.01 | -0.5 | 0.47 | x | 5644.84 ± 1125.16 | 7359.71 ± 769.69 | |||

| TG.52.3 | 0.67 | 0.08 | -0.41 | 0.38 | x | 5871.8 ± 1225.93 | 7209.96 ± 967.84 | |||

| TG.54.1b | 0.75 | <0.01 | -0.69 | 0.52 | x | 1119.48 ± 233.54 | 1650.3 ± 207.51 | |||

| TG.54.6 | 0.71 | 0.02 | -0.44 | 0.51 | x | 10750.34 ± 1936.83 | 13813.28 ± 1289.65 | |||

| TG.55.5 | 0.69 | 0.03 | -0.41 | 0.48 | x | 1918.8 ± 352.6 | 2479.95 ± 257.98 | |||

| TG.56.8 | 0.76 | <0.01 | -0.98 | 0.58 | x | x | 150.5 ± 34.36 | 263.58 ± 60.64 | ||

| TG.58.2a | 0.74 | <0.01 | -0.69 | 0.35 | x | 350.25 ± 73.99 | 476.86 ± 48.03 | |||

| TG.62.13 | 0.64 | 0.03 | 0.34 | -0.21 | x | 3162.55 ± 736.72 | 2296.29 ± 325.35 | |||

| TG.63.13 | 0.64 | 0.03 | 0.53 | -0.24 | x | x | 539.74 ± 170.8 | 348.6 ± 78.85 | ||

| TG.64.16b | 0.7 | 0.01 | 0.58 | -0.33 | x | 740.92 ± 199.04 | 464.71 ± 88.7 | |||

| TG.66.15 | 0.61 | 0.07 | 1.33 | -0.22 | x | 332.46 ± 148.58 | 180.21 ± 61.03 | |||

| TG.66.18 | 0.62 | 0.03 | 0.47 | -0.22 | x | 910.13 ± 314.41 | 524.17 ± 151.27 | |||

| TG.O-52.1 | 0.76 | <0.01 | -0.93 | 0.46 | x | x | 369.81 ± 102.77 | 637.06 ± 140.8 |

References

- van den Burg, S.W.K., et al., Exploring mechanisms to pay for ecosystem services provided by mussels, oysters and seaweeds. Ecosystem Services, 2022. 54.

- Sea, M.A., J.R. Hillman, and S.F. Thrush, The influence of mussel restoration on coastal carbon cycling. Glob Chang Biol, 2022. 28(17): p. 5269-5282.

- Nijdam, D., T. Rood, and H. Westhoek, The price of protein: Review of land use and carbon footprints from life cycle assessments of animal food products and their substitutes. Food Policy, 2012. 37(6): p. 760-770.

- Yaghubi, E., et al., Farmed Mussels: A Nutritive Protein Source, Rich in Omega-3 Fatty Acids, with a Low Environmental Footprint. Nutrients, 2021. 13(4).

- Lopez, A., F. Bellagamba, and V.M. Moretti, Nutritional quality traits of Mediterranean mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis): A sustainable aquatic food product available on Italian market all year round. Food Science and Technology International, 2022. 29(7): p. 718-728.

- Krause, G., et al., Prospects of Low Trophic Marine Aquaculture Contributing to Food Security in a Net Zero-Carbon World. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 2022. 6.

- Avdelas, L., et al., The decline of mussel aquaculture in the European Union: causes, economic impacts and opportunities. Reviews in Aquaculture, 2020. 13(1): p. 91-118.

- Stewart-Sinclair, P.J., et al., A global assessment of the vulnerability of shellfish aquaculture to climate change and ocean acidification. Ecol Evol, 2020. 10(7): p. 3518-3534.

- Navarro, E. and J.I.P. Iglesias, Energetics of reproduction related to evironmental variability in bivalve molluscs. Haliotis, 1995. 24: p. 43-55.

- Duinker, A., et al., Gonad development and spawning in one and two year old mussels (Mytilus edulis) from Western Norway. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 2008. 88(07).

- Murray, H.M., D. Gallardi, and T. Mills, Effect of culture depth and season on the condition and reproductive indices of blue mussels (Mytilus edulis L.) cultured in a cold-water coastal environment. Journal of Shellfish Research, 2019. 38(2): p. 351-362, 12.

- Seed, R. and R.A. Brown, A comparison of the reproductive cycles of Modiolus modiolus (L.), Cerastoderma (=Cardium) edule (L.), and Mytilus edulis L. in Strangford Lough, Northern Ireland. Oecologia, 1977. 30(2): p. 173-188.

- Villalba, A., Gametogenic cycle of cultured mussel, Mytilus galloprovincialis, in the bays of Galicia (NW Spain). Aquaculture, 1995. 130(2): p. 269-277.

- Pieters, H., J.H. Kluytmans, and D.I. Zandee, Tissue composition and reproduction of Mytilus edulis in relation to food availability. Netherlands Journal of Sea Research, 1980. 14(3/4): p. 349-361.

- Pipe, R.K., Ultrastructural and cytochemical study on interactions between nutrient storage cells and gametogenesis in the mussel Mytilus edulis. Marine Biology, 1987. 96: p. 519-528.

- Pipe, R.K., oogenesis in the marine mussel Mytilus edulis: an ultrastructural study. Marine Biology, 1987. 95: p. 405-414.

- Zandee, D.I., et al., Seasonal variations in biochemical composition of Mytilus edulis with reference to energy metabolism and gametogenesis. Netherlands Journal of Sea Research, 1980. 14(1): p. 1-29.

- Martínez-Pita, I., et al., Biochemical composition, lipid classes, fatty acids and sexual hormones in the mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis from cultivated populations in south Spain. Aquaculture, 2012. 358-359: p. 274-283.

- Dagorn, F., et al., Exploitable Lipids and Fatty Acids in the Invasive Oyster Crassostrea gigas on the French Atlantic Coast. Mar Drugs, 2016. 14(6): p. 104-116.

- Pazos, A.J., et al., Seasonal variations of the lipid content and fatty acid composition of Crassostrea gigas cultured in E1 Grove, Galicia, n.W. Spain. Comp. Biochem. Physiol., 1996. 114B(2): p. 171-179.

- Soudant, P., et al., Comparison of the lipid class and fatty acid composition between a reproductive cycle in nature and a standard hatchery conditioning of the Pacific Oyster Crassostrea gigas. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 1999. 123(2): p. 209-222.

- Abad, M., et al., Seasonal variations of lipid classes and fatty acids in flat oyster, Ostrea edulis, from San Cibran (Galicia, Spain). Camp. Biochem. Physiol., 1995. 110C(2): p. 109-118.

- Alkanani, T., et al., Role of fatty acids in cultured mussels, Mytilus edulis, grown in Notre Dame Bay, Newfoundland. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2007. 348(1-2): p. 33-45.

- Orban, E., et al., Seasonal changes in meat content, condition index and chemical composition of mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) cultured in two different Italian sites. Food Chem, 2002. 77: p. 57-65.

- Mladimeo, I., et al., The reproductive cycle, condition index and biochemical composition of the horse-bearded mussel Modiolus barbatus. Helgol Mar Res, 2007. 61: p. 183-192.

- Zheng, H., et al., Cloning and expression of vitellogenin (Vg) gene and its correlations with total carotenoids content and total antioxidant capacity in noble scallop Chlamys nobilis (Bivalve: Pectinidae). Aquaculture, 2012. 366-367: p. 46-53.

- Beninger, P.G., Seasonal variations of the major lipid classes in relation to the reproductive activity of two species of clams raised in a common habitat: Tapes decussatus l. (Jeffreys, 1863) and T. philippinarum (Adams & Reeve, 1850). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol., 1984. 79: p. 79-90.

- Beninger, P.G., Caveat observator: the many faces of pre-spawning atresia in marine bivalve reproductive cycles. Marine Biology, 2017. 164(8).

- Fearman, J. and N.A. Moltschaniwskyj, Warmer temperatures reduce rates of gametogenesis in temperate mussels, Mytilus galloprovincialis. Aquaculture, 2010. 305: p. 20-25.

- Helm, M.M. and N. Bourne, Hatchery culture of bivalves: a practical manual;. FAO Fisheries technical paper 471, ed. A. Lovatelli. 2004, Rome: FAO, Food and Agriculture Organizatio.

- Lucas, A. and P.G. Beninger, The use of physiological condition indices in marine bivalve aquaculture. Aquaculture, 1985. 44: p. 187-200.

- Toro, J.E., R.J. Thompson, and D.J. Innes, Reproductive isolation and reproductive output in two sympatric mussel species (Mytilus edulis, M. trossulus) and their hybrids from Newfoundland. Marine Biology, 2002. 141(5): p. 897-909.

- Chipperfield, P.N.J., Observations on the breeding and settlement of Mytilus edulis (L.) in British waters. Journal of Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 1953. 32(2): p. 449-476.

- Seed, R., Ecology, in Marine mussels: their ecology and physiology, B.L. Bayne, Editor. 1976, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

- Gosling, E., Bivalve mollusc, biology, ecology and culture. 2004: Fishing New books, Blakwell Science.

- Gosling, E., Bivalve Molluscs, Biology, Ecology and culture. 2004: Blackwell Publishing. 443.

- Beninger, P.G., A qualitative and quantitative study of the reproductive cycle of the giant scallop, Placopecten magellanicus, in the Bay of Fundy (New Brunswick, Canada). Canadian journal of Zoology, 1987. 65(3): p. 495-498.

- Fraser, M., et al., Sex determination in blue mussels: Which method to choose? Marine Environmental Research 120, 2016. 120: p. 78-85.

- Bayne, B.L., et al., Further studies on the effects of stress in the adult on the eggs of Mytilus edulis. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 1978. 58(4): p. 825-841.

- Newell, R. and B. Bayne, Seasonal changes in the physiology, reproductive condition and carbohydrate content of the cockle Cardium (= Cerastoderma) edule (Bivalvia: Cardiidae). Marine Biology, 1980. 56(1): p. 11-19.

- Pipe, R., Seasonal cycles in and effects of starvation on egg development in Mytilus edulis. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 1985: p. 121-128.

- Murray, H.M. and L.M.N. Ollerhead, A comparison of ArcGIS and Image J software tools for calculation of gonad volume fraction (GVF) froom histological sections of blue mussel cultured in deep and shallow sites on the Nortehrn coast of Newfoundland. Can. Tech. Rep. Fish. Aquat. Sci., 2018. 3275: p. vi-17.

- Hines, A., et al., Comparison of histological, genetic, metabolomics, and lipid-based methods for sex determination in marine mussels. Anal Biochem, 2007. 369(2): p. 175-86.

- Duinker, A., B.E. Torstersen, and Ø. Lie, Lipid classes and fatty acid composition of female gonads of great scallops: a selective field study. Journal of Shellfish Research, 2004. 23(2): p. 507-514.

- Martínez-Pita, I., et al., Effect of diet on the lipid composition of the commercial clam Donax trunculus (Mollusca: bivalvia): sex-related differences. Aquaculture Research, 2012. 43(8): p. 1134-1144.

- Soudant, P., et al., Impact of the quality of dietary fatty acids on metabolism and the composition of polar lipid classes in female gonads of Pecten maximus (L.). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 1996. 205: p. 149-163.

- Chérel, D. and P.G. Beninger, Oocyte atresia characteristics and effect on reproductive effort of Manila clam Tapes philippinarum (Adams and Reeve, 1850). Journal of Shellfish Research, 2017. 36(3): p. 549-557.

- Laudicella, V.A., et al., Application of lipidomics in bivalve aquaculture, a review. Reviews in Aquaculture, 2020. 12: p. 678-702.

- Chansela, P., et al., Composition and localization of lipids in Penaeus merguiensis ovaries during the ovarian maturation cycle as revealed by imaging mass spectrometry. PLoS One, 2012. 7(3): p. e33154.

- Laudicella, V.A., et al., Sexual dimorphism in the gonad lipidome of blue mussels (Mytilus sp.): New insights from a global lipidomics approach. Comp Biochem Physiol Part D Genomics Proteomics, 2023. 48: p. 101150.

- Breiman, L., Random forests. Machine Learning, 2001. 45: p. 5-32.

- Bayne, B.L., Marine mussels: their ecology and physiology. Vol. 10. 1976: Cambridge University Press.

- Alfaro, A.C., A.G. Jeffs, and S.H. Hooker, Reproductive behavior of the green-lipped mussel, Perna canaliculus, in northern New Zealand. Bulletin Of Marine Science, 2001. 69(3): p. 1095–1108.

- Folch, J., M. Lees, and G.H. Sloane Stanley, A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J biol Chem, 1957. 226(1): p. 497-509.

- Facchini, L., et al., Ceramide lipids in alive and thermally stressed mussels: an investigation by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization Fourier transform mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom, 2016. 51(9): p. 768-81.

- Fahy, E., et al., A comprehensive classification system for lipids. J Lipid Res, 2005. 46(5): p. 839-61.

- Fahy, E., et al., Update of the LIPID MAPS comprehensive classification system for lipids. J Lipid Res, 2009. 50 Suppl: p. S9-14.

- Boselli, E., et al., Characterization of phospholipid molecular species in the edible parts of bony fish and shellfish. J Agric Food Chem, 2012. 60(12): p. 3234-45.

- Chen, S., N.A. Belikova, and P.V. Subbaiah, Structural elucidation of molecular species of pacific oyster ether amino phospholipids by normal-phase liquid chromatography/negative-ion electrospray ionization and quadrupole/multiple-stage linear ion-trap mass spectrometry. Anal Chim Acta, 2012. 735: p. 76-89.

- Liu, Z.Y., et al., Characterization of glycerophospholipid molecular species in six species of edible clams by high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. Food Chem, 2017. 219: p. 419-427.

- Yin, F.W., et al., Identification of glycerophospholipid molecular species of mussel (Mytilus edulis) lipids by high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. Food Chem, 2016. 213: p. 344-51.

- Facchini, L., et al., Seasonal variations in the profile of main phospholipids in Mytilus galloprovincialis mussels: A study by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization Fourier transform mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom, 2018. 53(1): p. 1-20.

- Facchini, L., et al., Structural characterization and profiling of lyso-phospholipids in fresh and in thermally stressed mussels by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-Fourier transform mass spectrometry. Electrophoresis, 2016. 37(13): p. 1823-38.

- Losito, I., et al., Fatty acidomics: Evaluation of the effects of thermal treatments on commercial mussels through an extended characterization of their free fatty acids by liquid chromatography - Fourier transform mass spectrometry. Food Chem, 2018. 255: p. 309-322.

- Guercia, C., P. Cianciullo, and C. Porte, Analysis of testosterone fatty acid esters in the digestive gland of mussels by liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry. Steroids, 2017. 123: p. 67-72.

- Donato, P., et al., Comprehensive lipid profiling in the Mediterranean mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis) using hyphenated and multidimensional chromatography techniques coupled to mass spectrometry detection. Anal Bioanal Chem, 2018. 410(14): p. 3297-3313.

- Yurekten, O., et al., MetaboLights: open data repository for metabolomics. Nucleic Acids Res, 2024. 52(D1): p. D640-D646.

- Xia, J. and J. Chong, MetaboanlystR: An R package for comprehensive analysis of metabolomics data. 2018.

- Kassambara, A. and F. Mudt, Package 'factoextra'. 2017.

- Wold, S., K. Esbensen, and P. Geladi, Principal Component Analysis. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 1987. 2: p. 37-52.

- van den Berg, R.A., et al., Centering, scaling, and transformations: improving the biological information content of metabolomics data. BMC Genomics, 2006. 7: p. 142.

- Blighe, K., S. Rana, and M. Lewis, EnhancedVolcano: Publication-ready volcano plots with enhanced colouring and labeling. 2019.

- Benjamini, Y. and Y. Hochberg, Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal statistical society: series B (Methodological), 1995. 57(1): p. 289-300.

- Bylesjö, M., et al., OPLS discriminant analysis: combining the strengths of PLS-DA and SIMCA classification. Journal of Chemometrics, 2006. 20(8-10): p. 341-351.

- Gromski, P.S., et al., A tutorial review: Metabolomics and partial least squares-discriminant analysis--a marriage of convenience or a shotgun wedding. Anal Chim Acta, 2015. 879: p. 10-23.

- Brieuc, M.S.O., et al., A practical introduction to Random Forest for genetic association studies in ecology and evolution. Mol Ecol Resour, 2018. 18(4): p. 755-766.

- Liaw, A. and M. Wieiner, Package 'randomForest'. 2018.

- Molenaar, M.R., et al., LION/web: a web-based ontology enrichment tool for lipidomic data analysis. Gigascience, 2019. 8(6).

- Wagner, F., GO-PCA: An Unsupervised Method to Explore Gene Expression Data Using Prior Knowledge. PLoS One, 2015. 10(11): p. e0143196.

- Newell, R.I., et al., Temporal variation in the reproductive cycle of Mytilus edulis L.(Bivalvia, Mytilidae) from localities on the east coast of the United States. The Biological Bulletin, 1982. 162(3): p. 299-310.

- Pernet, F., S. Gauthier-Clerc, and E. Mayrand, Change in lipid composition in eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica Gmelin) exposed to constant or fluctuating temperature regimes. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol, 2007. 147(3): p. 557-65.

- Ren, S., et al., Computational and statistical analysis of metabolomics data. Metabolomics, 2015. 11(6): p. 1492-1513.

- Checa, A., C. Bedia, and J. Jaumot, Lipidomic data analysis: tutorial, practical guidelines and applications. Anal Chim Acta, 2015. 885: p. 1-16.

- Franceschi, P., M. Giordan, and R. Wehrens, Multiple comparisons in mass-spectrometry-based -omics technologies. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 2013. 50: p. 11-21.

- Pazos, A.J., et al., Lipid Classes and Fatty Acid Composition in the Female Gonad of Pecten maximus in Relation to Reproductive Cycle and Environmental Variables. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 1997. 117(3): p. 393-402.

- Zeng, X., et al., Variations in lipid composition of ovaries and hepatopancreas during vitellogenesis in the mud crab Scylla paramamosain: Implications of lipid transfer from hepatopancreas to ovaries. Aquaculture Reports, 2024. 35.

- Koutsouveli, V., et al., Oogenesis and lipid metabolism in the deep-sea sponge Phakellia ventilabrum (Linnaeus, 1767). Sci Rep, 2022. 12(1): p. 6317.

- Merrill, A.H., et al., Sphingolipids—The enigmatic lipid class: Biochemistry, physiology, and pathophysiology. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 1997. 142: p. 208-225.

- Alexaki, A., et al., De Novo Sphingolipid Biosynthesis Is Required for Adipocyte Survival and Metabolic Homeostasis. J Biol Chem, 2017. 292(9): p. 3929-3939.

- Dudek, J., Role of Cardiolipin in Mitochondrial Signaling Pathways. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2017. 5: p. 90.

- Kraffe, E., et al., A striking parallel between cardiolipin fatty acid composition and phylogenetic belonging in marine bivalves: A possible adaptative evolution? Lipids, 2008. 43(10): p. 961.

- Fernández-Reiriz, M.J., J.L. Garrido, and J. Irisarri, Fatty acid composition in Mytilus galloprovincialis organs: trophic interactions, sexual differences and differential anatomical distribution. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 2015. 528: p. 221-234.

- Kraffe, E., et al., Effect of reproduction on escape responses, metabolic rates and muscle mitochondrial properties in the scallop Placopecten magellanicus. Marine Biology, 2008. 156(1): p. 25-38.

- Fan, J., S. Upadhye, and A. Worster, Understanding receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. CJEM, 2006. 8(1): p. 19-20.

- Youden, W.J., Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer, 1950. 3(1): p. 32-35.

- Ren, C., et al., Lipidomic analysis of serum samples from migraine patients. Lipids Health Dis, 2018. 17(1): p. 22.

- Liu, C., et al., Lipidomic characterisation discovery for coronary heart disease diagnosis based on high-throughput ultra-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. RSC Advances, 2018. 8(2): p. 647-654.

- Kariotoglou, D.M. and S.K. Mastronicolis, Phosphonolipids in the mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis. Z. Naturforsch., 1998. 53c: p. 888–896.

- Kariotoglou, D.M. and S.K. Mastronicolis, Sphingophosphonolipid molecular species from edible mollusks and a jellyfish. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 2003. 136(1): p. 27-44.

- Losito, I., et al., Tracing the Thermal History of Seafood Products through Lysophospholipid Analysis by Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography(-)Electrospray Ionization Fourier Transform Mass Spectrometry. Molecules, 2018. 23(9): p. 2212-2228.

- Le Grand, F., et al., Membrane phospholipid composition of hemocytes in the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas and the Manila clam Ruditapes philippinarum. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol, 2011. 159(4): p. 383-91.

- Vacaru, A.M., et al., Ceramide phosphoethanolamine biosynthesis in Drosophila is mediated by a unique ethanolamine phosphotransferase in the Golgi lumen. J Biol Chem, 2013. 288(16): p. 11520-30.

- Pauletto, M., et al., Insights into molecular features of Venerupis decussata oocytes: a microarray-based study. PLoS One, 2014. 9(12): p. e113925.

- Tilly, J.L. and R.N. Kolesnick, Sphingolipid signaling in gonadal development and function. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids, 1999. 102: p. 149-155.

- Vance, D.E., Glycerolipids biosynthesis in eukaryotes., in Biochemistry of lipids, lipoproteins and membranes, V.D.E.a.V. J., Editor. 1996, Elsevier. p. 153-180.

- Zhu, J., et al., Characterization of Ovarian Lipid Composition in the Largemouth Bronze Gudgeon (Coreius guichenoti) at Different Development Stages. Fishes, 2024. 9(7).

- Fadok, V.A., et al., A receptor for phosphatidylserine-specific clearance of apoptotic cells. Nature, 2000. 405(6782): p. 85-90.

- Segawa, K. and S. Nagata, An Apoptotic ‘Eat Me’ Signal: Phosphatidylserine Exposure. Trends in Cell Biology, 2015. 25(11): p. 639-650.

- Gervais, O., T. Renault, and I. Arzul, Induction of apoptosis by UV in the flat oyster, Ostrea edulis. Fish Shellfish Immunol, 2015. 46(2): p. 232-42.

- Meehan, T.L., et al., Analysis of phagocytosis in the Drosophila ovary, in Oogenesis: Methods and Protocols, I.P. Nezis, Editor. 2016, Springer New York: New York, NY. p. 79-95.

- Serizier, S.B. and K. McCall, Scrambled eggs: apoptotic cell clearance by non-professional phagocytes in the Drosophila ovary. Frontiers in Immunology, 2017. 8.

- Mostafa, S., N. Nader, and K. Machaca, Lipid Signaling During Gamete Maturation. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2022. 10: p. 814876.

- Soudant, P., et al., Separation of major polar lipids in Pecten maximus by highperformance liquid chromatography and subsequent determination of their fatty acids using gas chromatography. Journal of Chromatography B, 1995. 673(15-26).

- Laudicella, V.A., et al., Lipidomics analysis of juveniles’ blue mussels (Mytilus edulis L. 1758), a key economic and ecological species. PLoS One, 2020. 15(2): p. e0223031.

- Rey, F., et al., Unravelling polar lipids dynamics during embryonic development of two sympatric brachyuran crabs (Carcinus maenas and Necora puber) using lipidomics. Sci Rep, 2015. 5: p. 14549.

- Whyte, J.N.C., N. Boume, and C.A. Hodgson, Assessment of biochemical composition and energy reserves in larvae of the scallop Patinopecten yessoensis. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol., 1987. 113: p. 113-124.

- Yamashita, A., et al., Acyltransferases and transacylases that determine the fatty acid composition of glycerolipids and the metabolism of bioactive lipid mediators in mammalian cells and model organisms. Prog Lipid Res, 2014. 53: p. 18-81.

- Johnstone, J., The spawning of the mussel (Mytilus edulis). Proceeding and Transactions of the Livrpool biological Society, 1898. 13: p. 104-121.

- Cuevas, N., et al., Development of histopathological indices in the digestive gland and gonad of mussels: integration with contamination levels and effects of confounding factors. Aquat Toxicol, 2015. 162: p. 152-164.

| Lipid ID(1) | AUC | 95% CI | p-value(2) | FC | Volcano | OPLS-DA | RFClass | RFreg | Not ripe Average ± CI (95%) |

Ripe Average ± CI (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAEP(42:2) | 0.808 | 0.671-0.925 | 3.63E-04 | 1.57 | X | X | X | 47.59 ± 9.06 | 20.67 ± 7.5 | |

| CAEP(42:3) | 0.804 | 0.683-0.916 | 9E-03 | 3.13 | X | X | X | 36.95 ± 11.25 | 11.19 ± 6.08 | |

| CerPE(34:3)a | 0.845 | 0.729-0.939 | 2.08E-03 | 0.98 | X | X | X | 95.62 ± 20.84 | 48.43 ± 8.13 | |

| CerPE(35:3/2) | 0.874 | 0.771-0.954 | 2.08E-03 | 1.08 | X | X | X | 132.82 ± 29.82 | 55.95 ± 7.87 | |

| CerPE(40:1) | 0.806 | 0.668-0.93 | 3.62E-03 | 1.17 | X | X | X | 34.15 ± 7.02 | 13.71 ± 5.25 | |

| CerPE(40:2) | 0.905 | 0.799-0.981 | 3.04E-04 | 1.48 | X | X | X | X | 46.4 ± 7.88 | 17.69 ± 4.48 |

| LPC(22:2) | 0.806 | 0.673-0.922 | 7.42E-03 | -1.62 | X | 115.47 ± 39.6 | 308.4 ± 101.03 | |||

| PA(38:6) | 0.815 | 0.69-0.917 | 0.023 | 5.66 | X | X | X | 12.45 ± 6.38 | 1.46 ± 1.54 | |

| PA(40:6) | 0.861 | 0.749-0.958 | 7.42E-03 | 2.85 | X | X | X | X | 33.14 ± 12.05 | 8.31 ± 3.64 |

| PA(44:4) | 0.811 | 0.685-0.925 | 0.014 | -1.75 | X | X | 102.52 ± 41.73 | 226.25 ± 58.24 | ||

| PA(O-38:6/P-38:5) | 0.851 | 0.735-0.94 | 2.62E-03 | 2.12 | X | X | X | X | 46.5 ± 13.09 | 15.64 ± 4.86 |

| PC(28:0) | 0.842 | 0.732-0.939 | 3.62E-03 | 1.35 | X | X | X | X | 426.29 ± 119.56 | 140.95 ± 36.64 |

| PC(30:0) | 0.848 | 0.717-0.943 | 2.36E-03 | 1.37 | X | X | X | X | 1149.26 ± 291.11 | 396.62 ± 108.82 |

| PC(O-30:0) | 0.803 | 0.672-0.927 | 0.012 | 1.48 | X | X | X | 862.53 ± 256.36 | 318.65 ± 112.49 | |

| PC(O-31:0) | 0.8 | 0.664-0.902 | 0.014 | 1.37 | X | X | X | 68.9 ± 21.25 | 41.64 ± 9.75 | |

| PC(O-32:0) | 0.802 | 0.668-0.919 | 0.016 | 1.35 | X | X | X | X | 923.78 ± 291.49 | 351.64 ± 111.32 |

| PC(O-46:10/P-46:9)a | 0.811 | 0.68-0.915 | 2.25E-03 | -1.42 | X | X | X | X | 145.61 ± 41.99 | 341.56 ± 83.65 |

| PE(O-34:3/P-34:2) | 0.828 | 0.717-0.942 | 0.059 | 0.98 | X | X | 53.51 ± 20.01 | 24.5 ± 4.84 | ||

| PE(O-36:1/P-36:0)b | 0.868 | 0.748-0.962 | 2.66E-03 | 1.63 | X | X | X | X | 65.23 ± 19.65 | 21.09 ± 4.88 |

| PE(O-36:2/P-36:1)b | 0.848 | 0.719-0.949 | 3.62E-03 | 0.96 | X | X | X | 94.97 ± 22.76 | 47.13 ± 7.8 | |

| PE(O-36:2/P-36:1)c | 0.875 | 0.772-0.948 | 2.08E-03 | 0.97 | X | X | 251.77 ± 50.85 | 121.82 ± 15.8 | ||

| PE(O-36:3/P-36:2) | 0.851 | 0.737-0.95 | 7.42E-03 | 0.61 | X | X | 308.04 ± 55.87 | 193.04 ± 19.3 | ||

| PE(O-37:2/P-37:1) | 0.858 | 0.749-0.948 | 1.32E-03 | 0.99 | X | X | X | 231.1 ± 39.56 | 121.75 ± 21.86 | |

| PE(O-37:3/P-37:2) | 0.845 | 0.719-0.938 | 2.08E-03 | 0.51 | X | X | X | 428.34 ± 49.7 | 300.34 ± 26.36 | |

| PE(O-37:4/P-37:3) | 0.868 | 0.752-0.964 | 3.26E-03 | 0.74 | X | X | X | 84.17 ± 14.05 | 50.25 ± 6.82 | |

| PE(O-39:3/P-39:2) | 0.8 | 0.692-0.905 | 3.62E-03 | 0.45 | X | X | 360.03 ± 39.86 | 264.36 ± 23.89 | ||

| PG(34:1) | 0.86 | 0.735-0.96 | 7.29E-03 | 2.19 | X | X | X | X | 25.61 ± 8.8 | 7.32 ± 2.83 |

| PS(36:2) | 0.81 | 0.65-0.913 | 3.0E-03 | 7.06 | X | X | X | 16.21 ± 10.11 | 0.14 ± 0.22 | |

| PS(38:5) | 0.894 | 0.79-0.962 | 1.32E-03 | 1.61 | X | X | X | X | 215.46 ± 51.5 | 66.38 ± 17.26 |

| PS(38:6)a | 0.84 | 0.728-0.935 | 3.62E-03 | 1.23 | X | X | X | 164.04 ± 40.39 | 66.94 ± 16.21 | |

| PS(39:6) | 0.823 | 0.695-0.926 | 0.033 | 1.21 | X | X | 96.45 ± 35.18 | 39.88 ± 10.52 | ||

| PS(40:2) | 0.828 | 0.72-0.926 | 7.94E-03 | 0.75 | X | X | 157.85 ± 32.77 | 91.97 ± 13.65 | ||

| PS(40:5) | 0.82 | 0.691-0.92 | 5.49E-03 | 1.52 | X | 41.86 ± 11.05 | 18.17 ± 5.55 | |||

| PS(40:6) | 0.889 | 0.785-0.981 | 2.08E-03 | 1.06 | X | X | X | 329.08 ± 66.25 | 155.36 ± 27.89 | |

| PS(O-38:5/P-38:4) | 0.875 | 0.777-0.957 | 1.29E-03 | 0.82 | X | X | X | 163.08 ± 24.44 | 94.22 ± 13.23 | |

| PS(O-38:6/P-38:5) | 0.855 | 0.732-0.956 | 2.36E-03 | 0.99 | X | X | X | 361.75 ± 74.27 | 168.69 ± 30.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).