Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

16 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

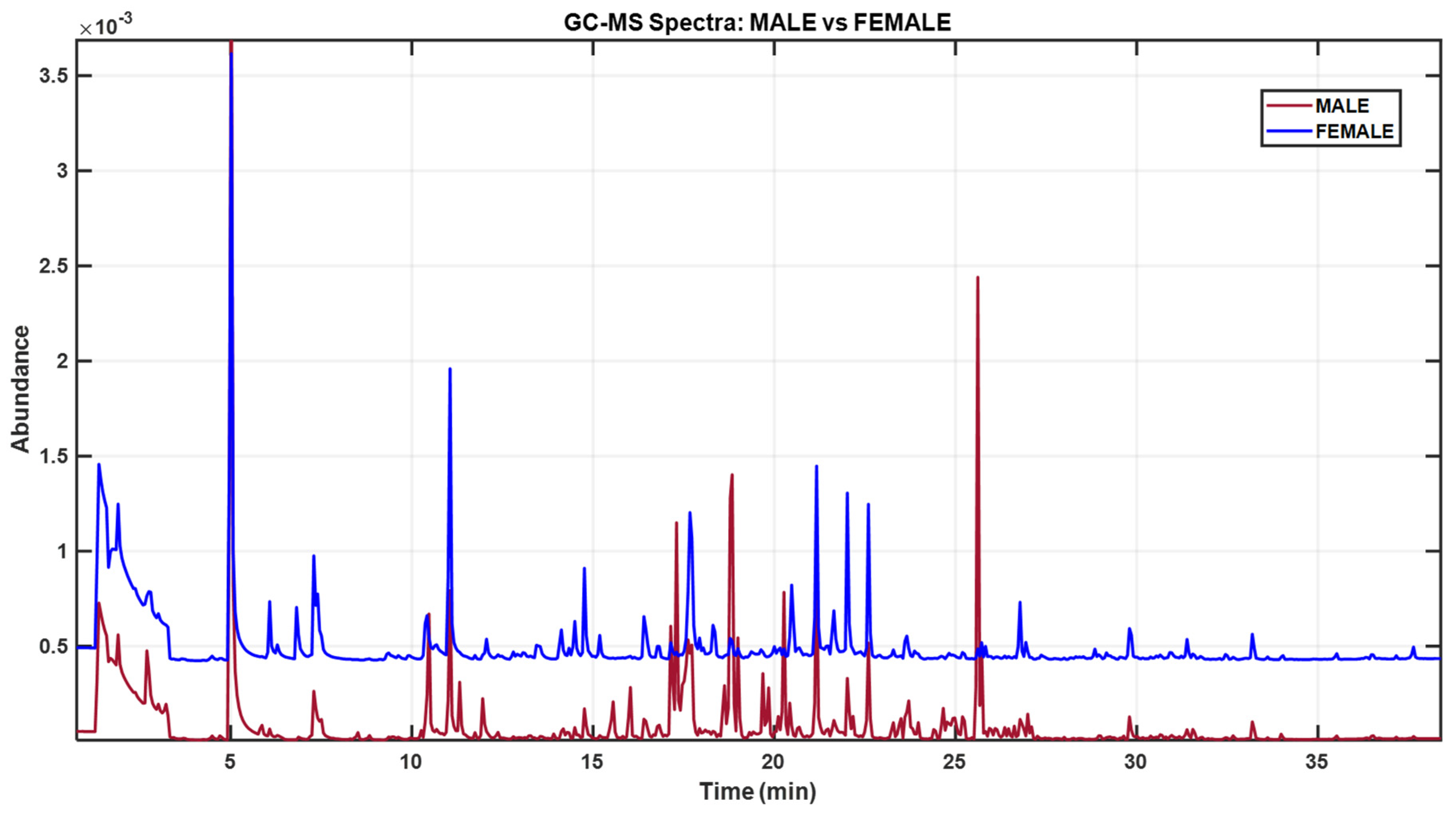

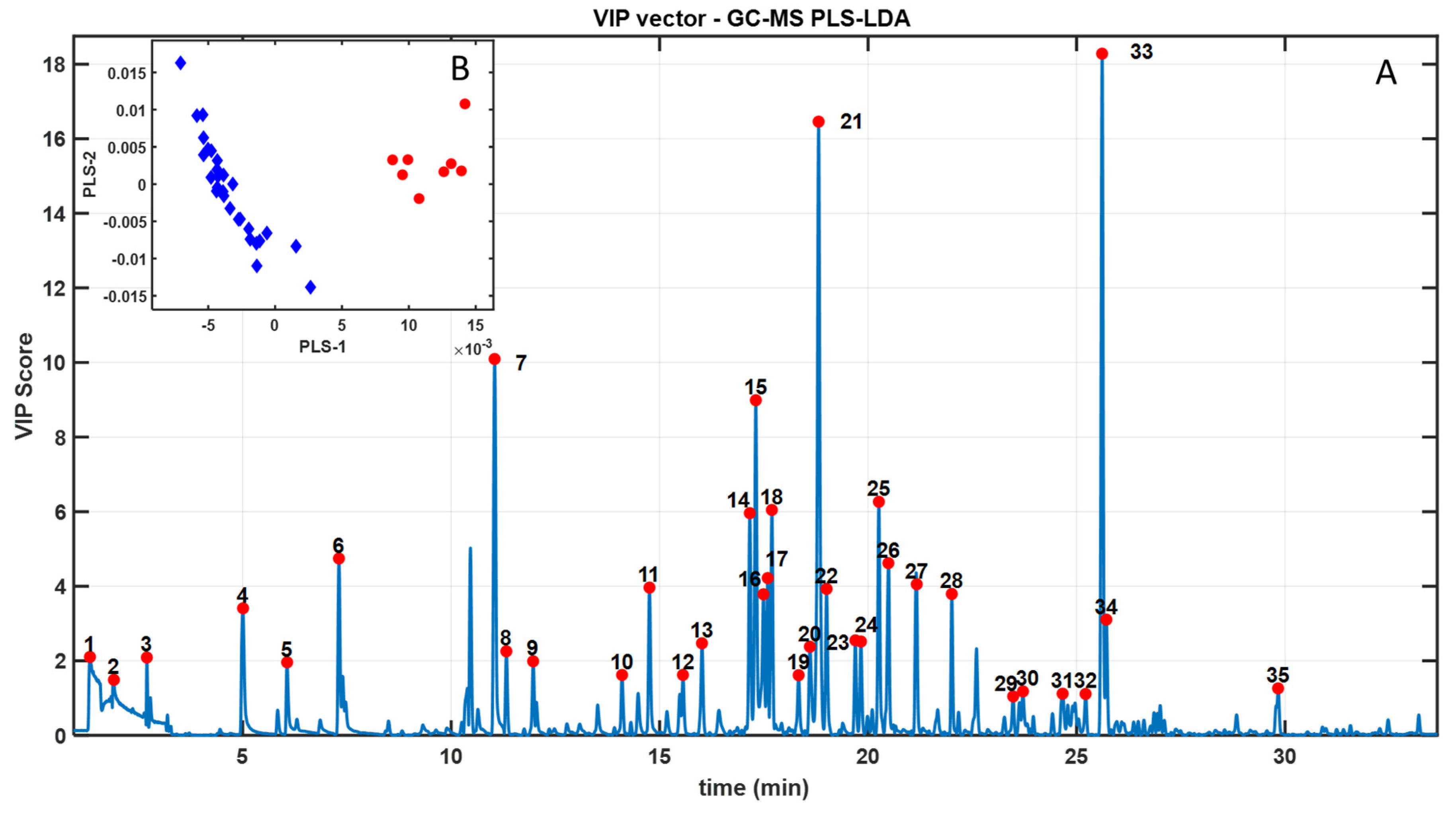

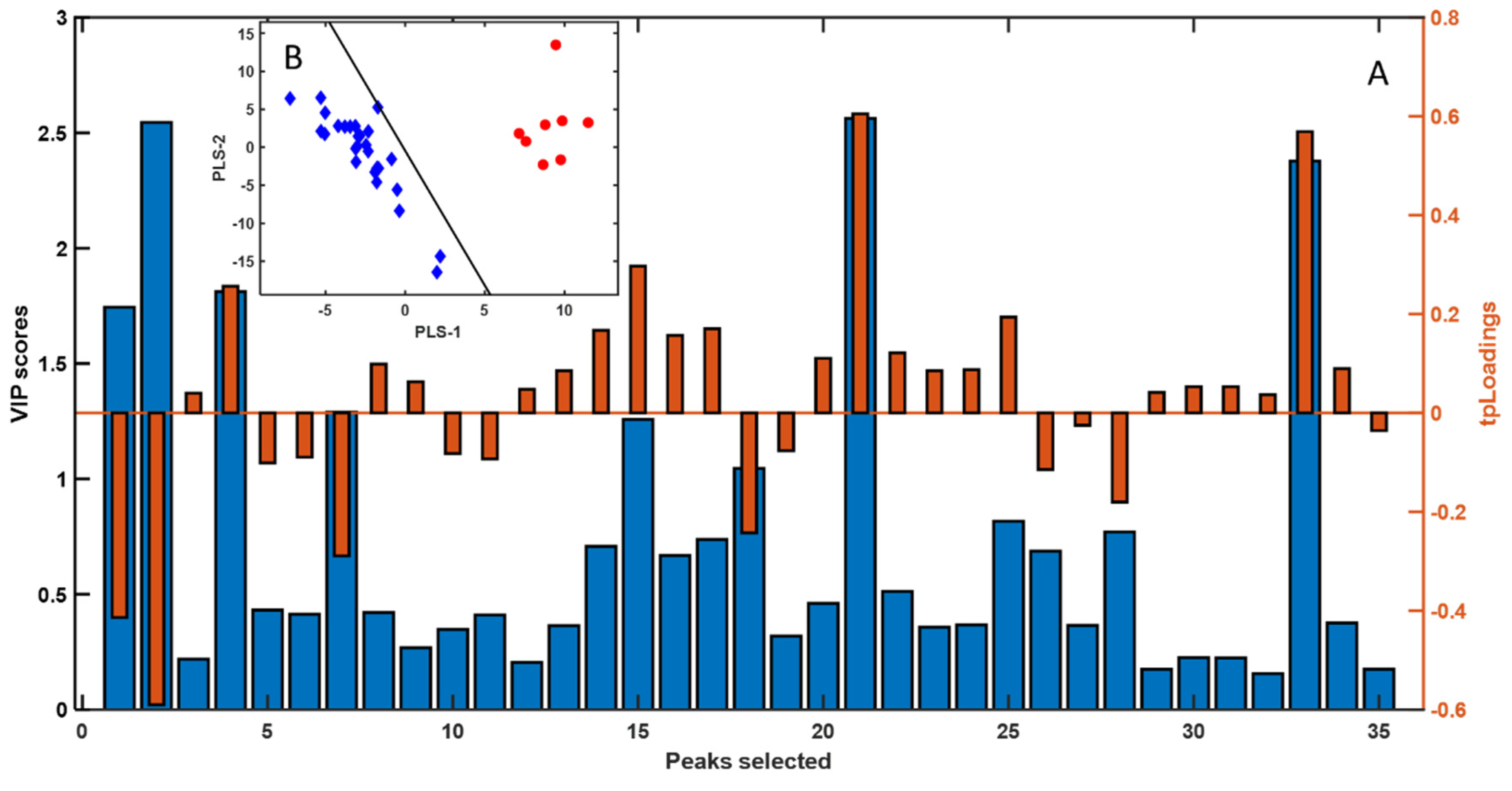

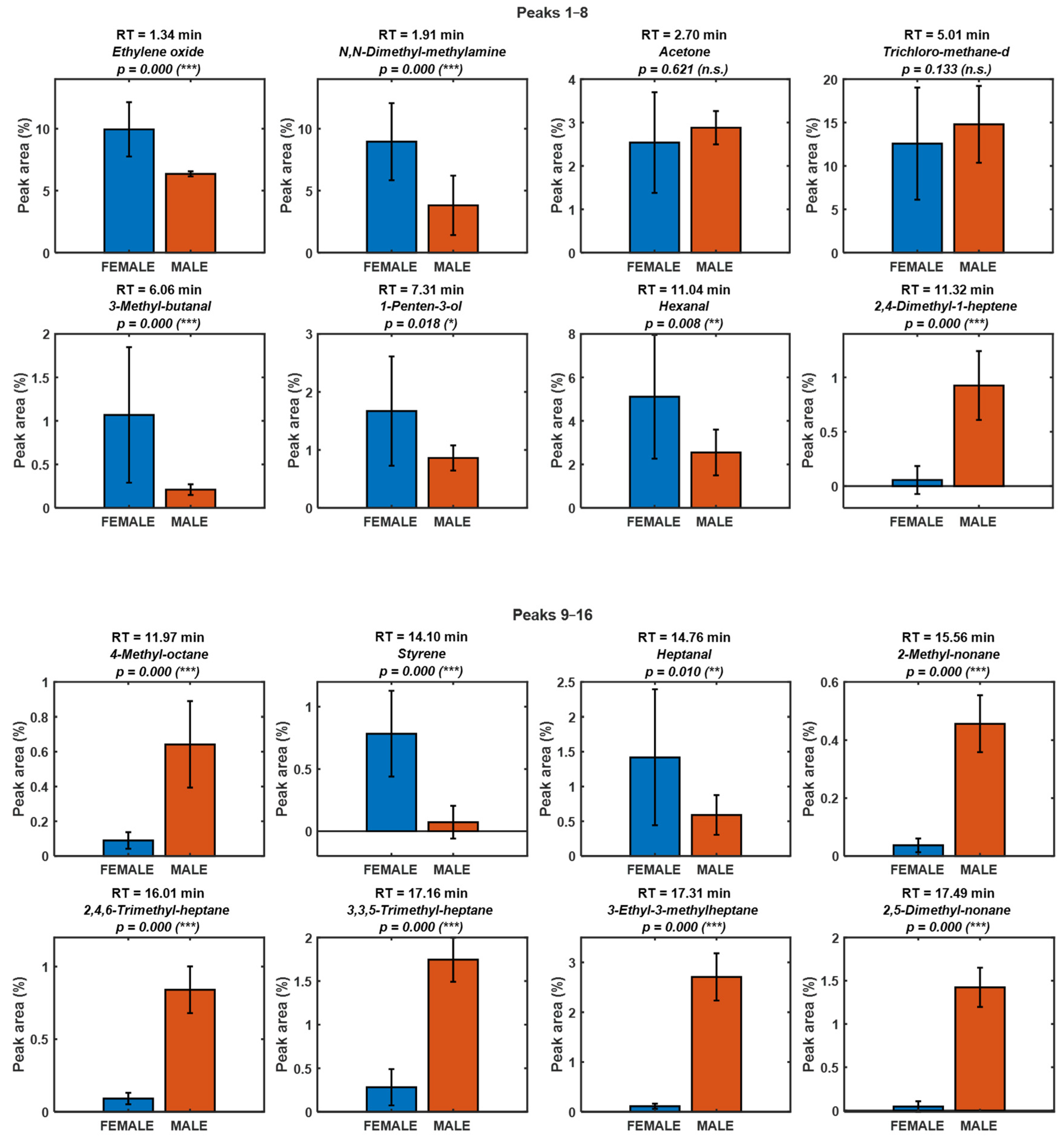

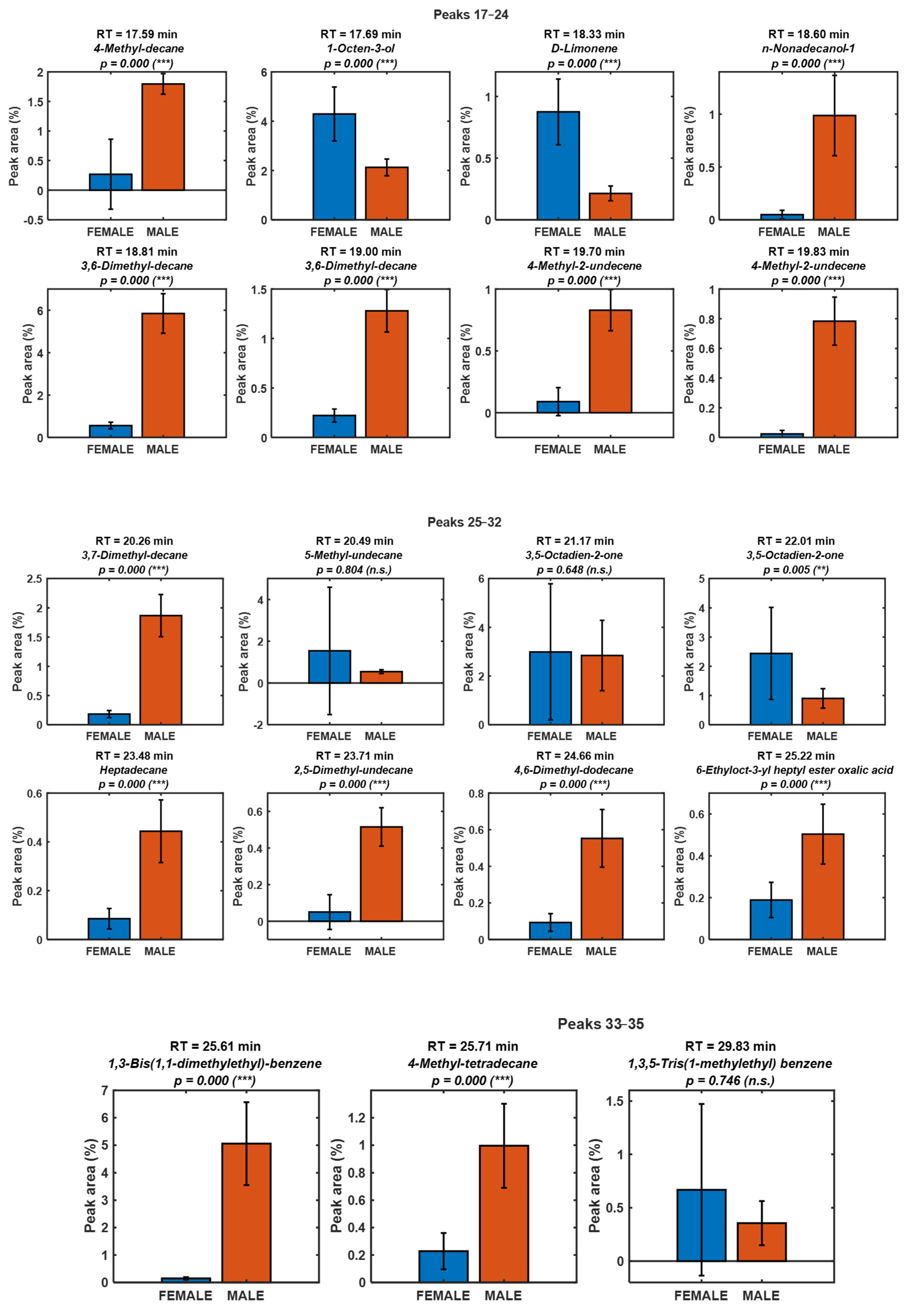

Background: The edible gonads of the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus are highly valued, yet sex cannot be determined externally, limiting selective harvest and quality control. Objective: To test whether headspace solid-phase microextraction gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (HS-SPME–GC–MS) combined with chemometrics can discriminate sex from gonadal volatilomes. Methods: Gonads from 29 individuals (21 females, 8 males) were profiled by HS-SPME–GC–MS. Spectral data were modeled with Partial Least Squares–Linear Discriminant Analysis (PLS–LDA); Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) scores highlighted key features, and Mann–Whitney tests (FDR-adjusted) assessed univariate differences. Tentative identifications were assigned by library match and curated for potential environmental artefacts. Results: Chemometric modeling yielded a clear female–male separation. Female gonads were enriched in low-odour-threshold oxygenates—aldehydes (hexanal, heptanal) and alcohols (1-penten-3-ol, 1-octen-3-ol)—together with diet-linked monoterpenes (e.g., D-limonene), consistent with PUFA LOX/HPL pathways and macroalgal inputs. Male gonads were dominated by saturated/branched hydrocarbons and long-chain alcohols with limited direct odour impact. Minor aromatic hydrocarbons (e.g., styrene; 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-benzene) were retained as environmental/artefact markers and excluded from biological interpretation. Conclusions: HS-SPME–GC–MS volatilomics coupled with PLS–LDA effectively distinguishes the sex of P. lividus gonads and rationalizes reported sensory differences. The marker set offers a basis for future non-destructive sexing workflows, pending confirmation with retention indices, authentic standards, and GC-olfactometry.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Preparation

2.2. VOC Extraction and GC–MS Analysis

2.3. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Phillips, K., J. Niimi, N. Hamid, P. Silcock and P. Bremer. “Sensory and volatile analysis of sea urchin roe from different geographical regions in new zealand.” LWT - Food Science and Technology 43 (2010): 202-13. 10.1016/j.lwt.2009.08.008. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0023643809002333.

- Rocha, F., H. Peres, P. Diogo, R. Ozório and L. M. P. Valente. “The effect of sex, season and gametogenic cycle on gonad yield, biochemical composition and quality traits of paracentrotus lividus along the north atlantic coast of portugal.” PeerJ 7 (2019): 10.7717/peerj.6177. [CrossRef]

- Brattoli, M., G. De Gennaro, V. De Pinto, A. Demarinis Loiotile, S. Lovascio and M. Penza. “Odour detection methods: Olfactometry and chemical sensors.” Sensors 11 (2011): 5290-322. 10.3390/s110505290. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. “Discrimination of honeys by hs-spme–gc–ms volatile fingerprints.” Food Chemistry (2019): 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.07.111. [CrossRef]

- Acquaticci, L., S. Angeloni, C. Baldassarri, G. Sagratini, S. Vittori, E. Torregiani, R. Petrelli and G. Caprioli. “A new hs-spme-gc-ms analytical method to identify and quantify compounds responsible for changes in the volatile profile in five types of meat products during aerobic storage at 4 °c.” Food Research International 187 (2024): 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.114398. [CrossRef]

- Epping, R., M. O’Sullivan, S. Higgins, M. Cremonesi, A. Voilley and N. Cayot. “Changes in tuber melanosporum aroma during storage: Spme-gc-ms versus sensory.” Foods 13 (2024): 837. 10.3390/foods13060837. [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A. M., S. Angeloni, D. Abouelenein, S. Vittori and G. Caprioli. “An overview on truffle aroma and main volatile compounds.” Molecules 25 (2020): 5948. 10.3390/molecules25245948. [CrossRef]

- Gloaguen, Y., M. Riu-Boni, T. Stark and P. Schieberle. “Characterization of the volatilome of tuber canaliculatum by hs-spme-gc-ms.” ACS Omega 7 (2022): 26534-44. 10.1021/acsomega.2c02877. [CrossRef]

- Takagi, S., Y. Sato, Y. Murata, A. Kokubun, K. Touhata, N. Ishida and Y. Agatsuma. Quantification of the flavor and taste of gonads from the sea urchin mesocentrotus nudus using gc–ms and a taste-sensing system. 20. 2020,.

- Li, H., Y. Liang, Q. Xu and D. Cao. “Key wavelengths screening using competitive adaptive reweighted sampling method for multivariate calibration.” Anal Chim Acta 648 (2009): 77-84. 10.1016/j.aca.2009.06.046. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19616692.

- Tang, L., S. L. Peng, Y. M. Bi, P. Shan and X. Y. Hu. “A new method combining lda and pls for dimension reduction.” Plos One 9 (2014): 10.1371/journal.pone.0096944. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000336653300053.

- Wen, Z. C., T. Sun, X. Geng and M. H. Liu. “Discrimination of pressed and extracted camellia oils by vis/nir spectra combined with uve-pls-lda.” Spectroscopy and Spectral Analysis 33 (2013): 2354-58. 10.3964/j.issn.1000-0593(2013)09-2354-05. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000326064200011.

- Niimi, J., M. Leus, P. Silcock, N. Hamid and P. Bremer. “Characterisation of odour active volatile compounds of new zealand sea urchin (evechinus chloroticus) roe using gc-o-fscm.” Food Chemistry 121 (2010): 601-07. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.12.071. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0308814609014927.

- Takagi, S., Y. Sato, A. Kokubun, E. Inomata and Y. Agatsuma. “Odor-active compounds from the gonads of mesocentrotus nudus sea urchins fed saccharina japonica kelp.” PLOS ONE 15 (2020): 10.1371/journal.pone.0231673. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0231673.

- Su, T., G. Zhang, Y. Zhao, J. Zhang, X. Shang, Q. Shen, S. Hua and X. Zhu. “The biosynthesis of 1-octen-3-ol by a multifunctional fatty acid dioxygenase and hydroperoxide lyase in agaricus bisporus.” Journal of Fungi 8 (2022): 10.3390/jof8080827. https://www.mdpi.com/2309-608X/8/8/827.

- Morawicki, R. O. and R. B. Beelman. “Study of the biosynthesis of 1-octen-3-ol using a crude homogenate of agaricus bisporus in a bioreactor.” Journal of Food Science 73 (2008): C135-C39. [CrossRef]

- Baião, L. F., C. Rocha, R. C. Lima, A. Marques, L. M. P. Valente and L. M. Cunha. “Sensory profiling, liking and acceptance of sea urchin gonads from the north atlantic coast of portugal, aiming future aquaculture applications.” Food Research International 140 (2021): 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109873. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33648191/.

- Sato, Y., S. Takagi, E. Inomata and Y. Agatsuma. “Odor-active volatile compounds from the gonads of the sea urchin mesocentrotus nudus in the wild in miyagi prefecture, tohoku, japan.” Food and Nutrition Sciences 10 (2019): 860-75.

- Rodríguez-Bernaldo de Quirós, A., J. López-Hernández, M. J. González-Castro, C. de la Cruz-García and J. Simal-Lozano. “Comparison of volatile components in fresh and canned sea urchin (paracentrotus lividus, lamarck) gonads by gc–ms using dynamic headspace sampling and microwave desorption.” European Food Research and Technology 212 (2001): 643-47. 10.1007/s002170100315. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s002170100315.

- Eriotou, E., I. K. Karabagias, S. Maina, D. Koulougliotis and N. Kopsahelis. “Geographical origin discrimination of “Ntopia” Olive oil cultivar from ionian islands using volatile compounds analysis and computational statistics.” Eur Food Res Technol 247 (2021): 3083-98. 10.1007/s00217-021-03863-2.

- Kopsahelis, N., I. K. Karabagias, H. Papapostolou and E. Eriotou. “Cultivar authentication of olive oil from ionian islands using volatile compounds and chemometric analyses.” Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 18 (2024): 4402-16. 10.1007/s11694-024-02502-0. [CrossRef]

| Number | RT (min) | Name | Chemical class | Putative origin |

| 1 | 1.34 | Ethylene oxide | Epoxide | Environmental/artefact |

| 2 | 1.91 | N,N-Dimethyl-methylamine | Amine | Biogenic amine / degradation |

| 3 | 2.70 | Acetone | Ketone | Uncertain |

| 4 | 5.01 | Trichloro-methane-d | Halogenated solvent | Environmental/artefact |

| 5 | 6.06 | 3-Methyl-butanal | Aldehyde | Biogenic (PUFA oxidation, LOX/HPL) |

| 6 | 7.31 | 1-Penten-3-ol | Alcohol | Biogenic (PUFA oxidation, LOX/HPL) |

| 7 | 11.04 | Hexanal | Aldehyde | Biogenic (PUFA oxidation, LOX/HPL) |

| 8 | 11.32 | 2,4-Dimethyl-1-heptene | Alkene | Biogenic (low odor impact) |

| 9 | 11.97 | 4-Methyl-octane | Other | Uncertain |

| 10 | 14.10 | Styrene | Aromatic hydrocarbon |

Environmental/artefact |

| 11 | 14.76 | Heptanal | Alkane | Biogenic (low odor impact) |

| 12 | 15.56 | 2-Methyl-nonane | Aromatic hydrocarbon |

Environmental (possible packaging/ambient) |

| 13 | 16.01 | 2,4,6-Trimethyl-heptane | Alkane | Biogenic (low odor impact) |

| 14 | 17.16 | 3,3,5-Trimethyl-heptane | Alkane | Biogenic (low odor impact) |

| 15 | 17.31 | 3-Ethyl-3-methylheptane | Monoterpene | Diet-derived (macroalgae) / biogenic |

| 16 | 17.49 | 2,5-Dimethyl-nonane | Alkane | Biogenic (low odor impact) |

| 17 | 17.59 | 4-Methyl-decane | Alkane | Biogenic (low odor impact) |

| 18 | 17.69 | 1-Octen-3-ol | Aldehyde | Biogenic (PUFA oxidation, LOX/HPL) |

| 19 | 18.33 | D-Limonene | Alkane | Biogenic (low odor impact) |

| 20 | 18.60 | n-Nonadecanol-1 | Alkane | Biogenic (low odor impact) |

| 21 | 18.81 | 3,6-Dimethyl-decane | Alkane | Biogenic (low odor impact) |

| 22 | 19.00 | 3,6-Dimethyl-decane | Alkene | Biogenic (low odor impact) |

| 23 | 19.70 | 4-Methyl-2-undecene | Alkene | Biogenic (low odor impact) |

| 24 | 19.83 | 4-Methyl-2-undecene | Alkane | Biogenic (low odor impact) |

| 25 | 20.26 | 3,7-Dimethyl-decane | Ketone | Biogenic (PUFA oxidation, LOX/HPL) |

| 26 | 20.49 | 5-Methyl-undecane | Ketone | Biogenic (PUFA oxidation, LOX/HPL) |

| 27 | 21.17 | 3,5-Octadien-2-one | Alkane | Biogenic (low odor impact) |

| 28 | 22.01 | 3,5-Octadien-2-one | Alkane | Biogenic (low odor impact) |

| 29 | 23.48 | Heptadecane | Alkane | Biogenic (low odor impact) |

| 30 | 23.71 | 2,5-Dimethyl-undecane | Alkane | Biogenic (low odor impact) |

| 31 | 24.66 | 4,6-Dimethyl-dodecane | Alkane | Biogenic (low odor impact) |

| 32 | 25.22 | 6-Ethyloct-3-yl heptyl ester oxalic acid | Ester | Uncertain (low-volatility ester unlikely in HS-SPME; keep tentative) |

| 33 | 25.61 | 1,3-Bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-benzene | Aromatic hydrocarbon | Environmental/artefact |

| 34 | 25.71 | 4-Methyl-tetradecane | Alkane | Biogenic (low odor impact) |

| 35 | 29.83 | 1,3,5-Tris(1-methylethyl) benzene | Aromatic hydrocarbon | Environmental/artefact |

| Attribute | Female Gonads | Male Gonads |

| Dominant Chemical Families | Terpenes, Aldehydes, Alcohols, Ketones, Amines | Saturated and Branched Hydrocarbons, Long-chain Alcohols, Aromatic Hydrocarbons |

| Key Compounds | D-Limonene, Hexanal, Heptanal, 1-Penten-3-ol, 1-Octen-3-ol, 3-Methyl-butanal | 3,6-Dimethyldecane, 3-Ethyl-3-methylheptane, Heptadecane, n-Nonadecanol-1 |

| Sensory Attributes | Sweet, fruity, citrus, green-herbaceous, earthy-mushroom, marine freshness | Neutral, mild, smooth; negligible aroma intensity |

| Aromatic Complexity | High – Presence of low-threshold oxygenated volatiles and terpenes | Low – Dominance of high-threshold saturated hydrocarbons |

| Lipid Metabolic Activity Indicator | High lipid turnover and oxidative activity associated with reproductive phase | Stable lipid matrix, lower oxidative activity |

| Dietary Influence Markers | Presence of diet-derived terpenoids (e.g., D-limonene) | Minimal or absent; no terpenoid accumulation |

| Spoilage/Degradation Markers | Controlled levels of amines (e.g., N,N-dimethyl-methylamine) linked to freshness perception | Not detected; no significant spoilage-related VOCs |

| Environmental Contamination Indicators | Styrene (low levels, potential packaging or environmental marker) | 1,3-Bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-benzene (potential environmental marker) |

| Organoleptic Profile Summary | Rich, sweet, fruity-marine aroma with complex aromatic bouquet | Mild, bland, structurally neutral flavor, lacking fruity or marine aromatic complexity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).