Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Collection and Sample Preparation

2.2. Heavy Metals Analysis by ICP-MS

2.3. Fatty Acid Analysis by GC-MS

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

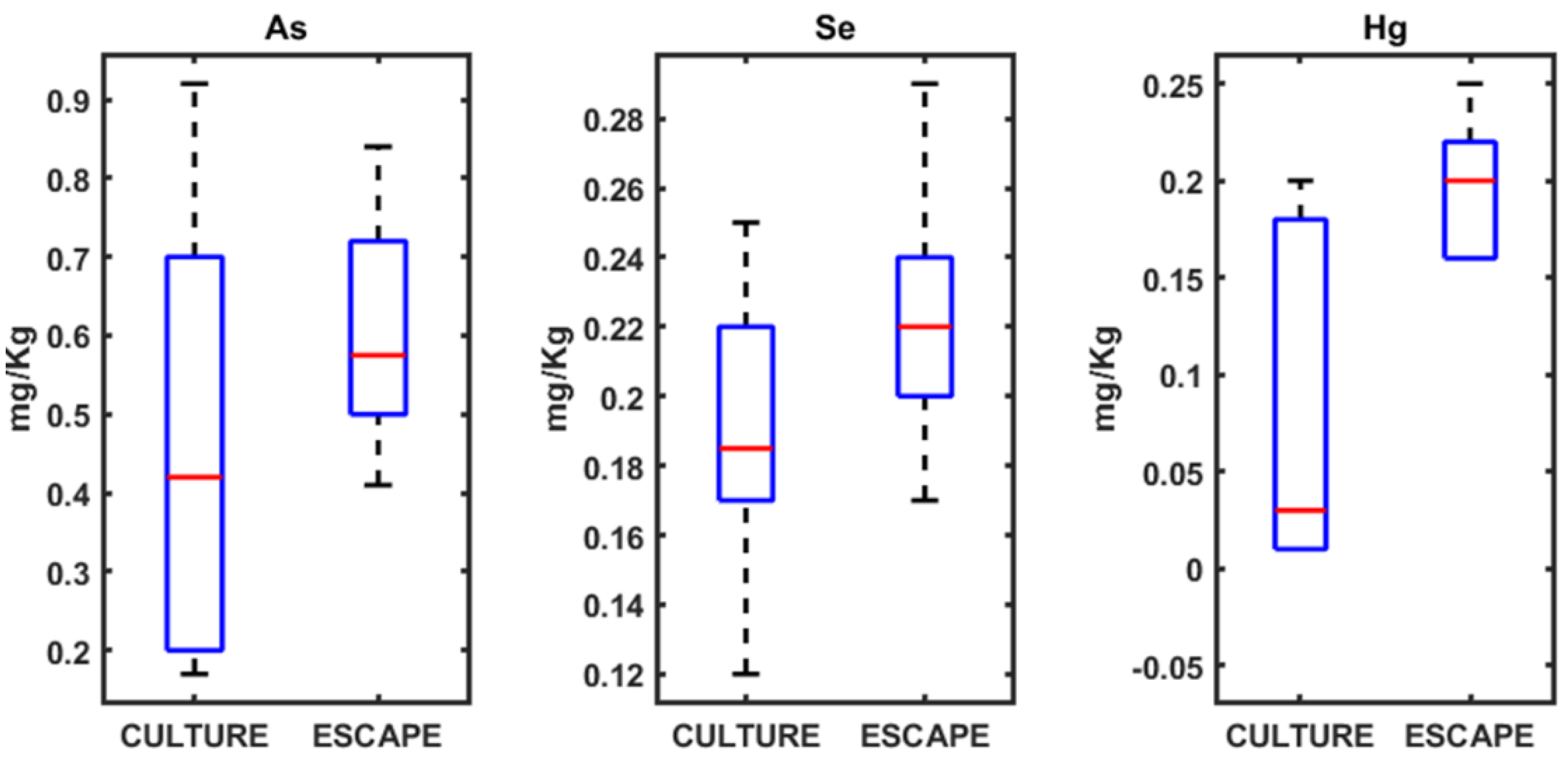

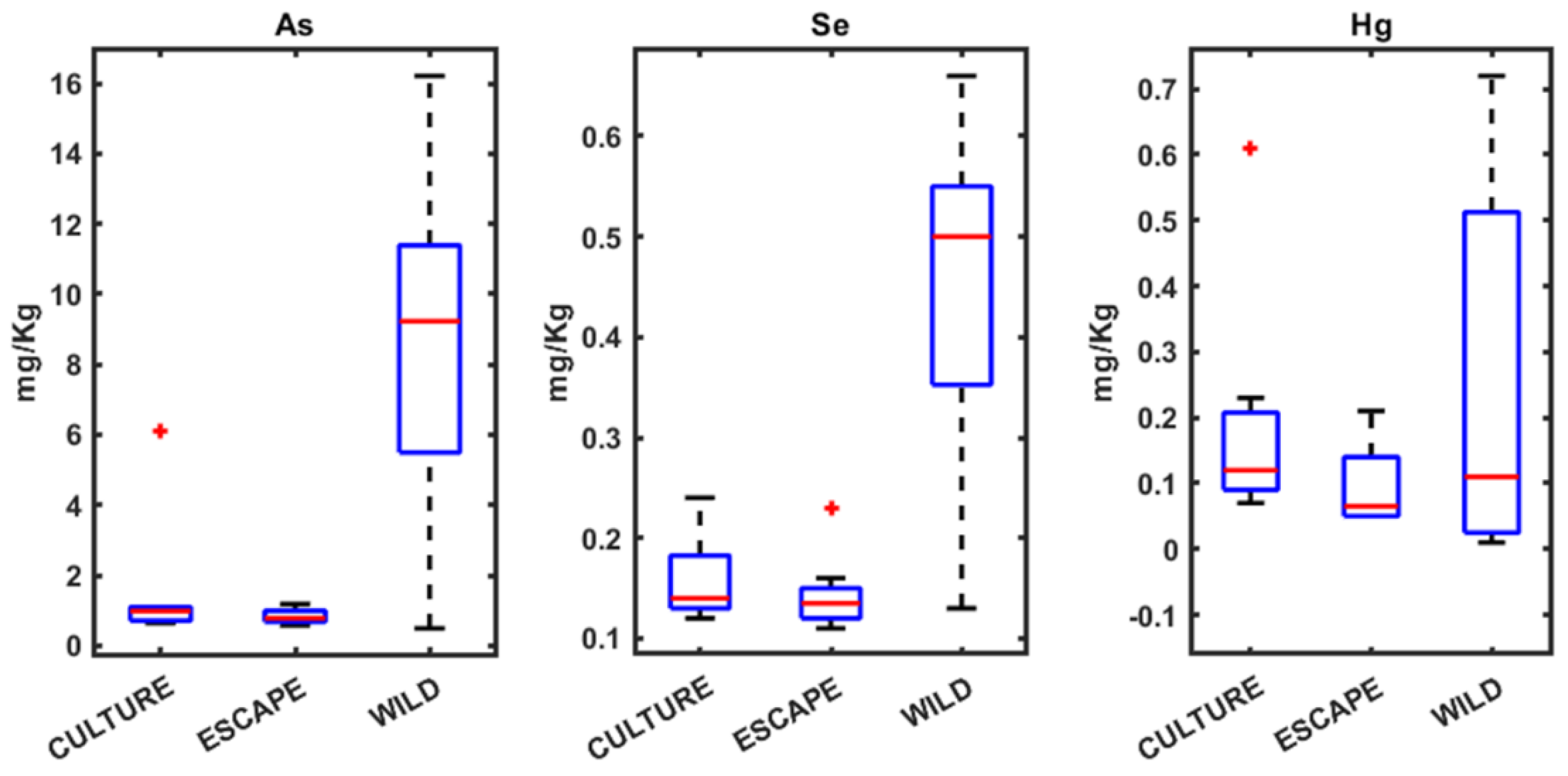

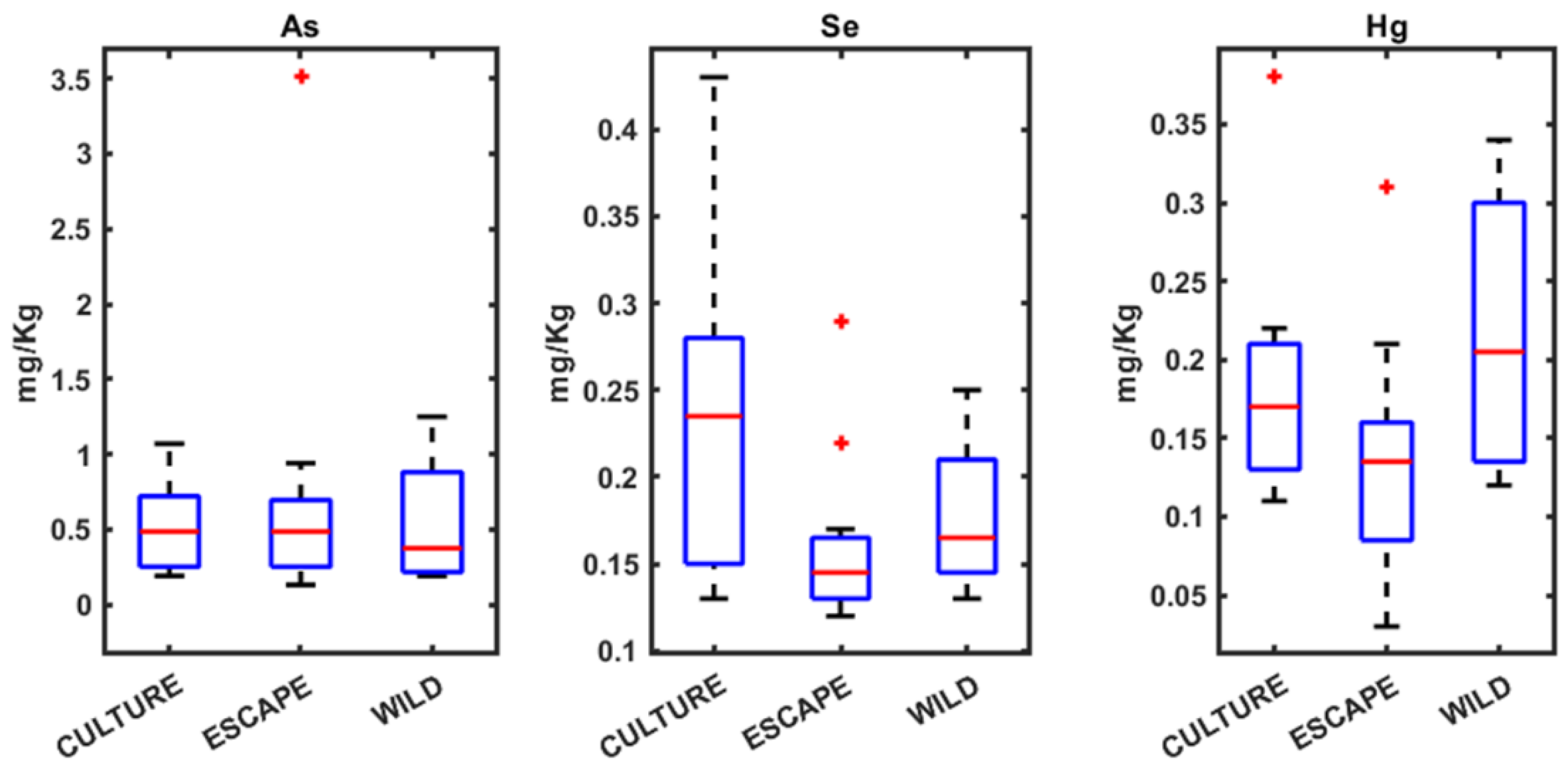

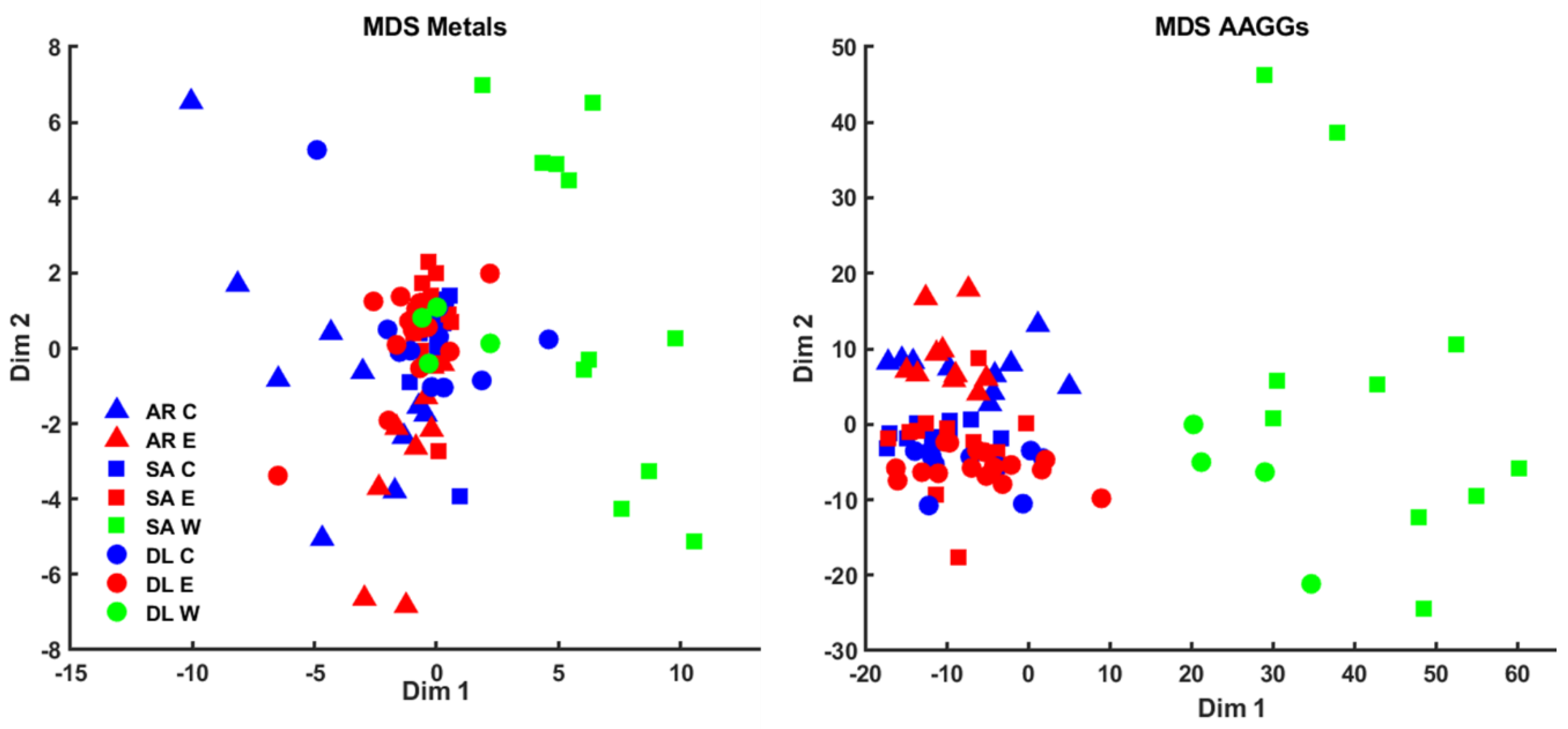

3.1. Heavy Metals Analysis in Seabream, Seabass, and Meagre

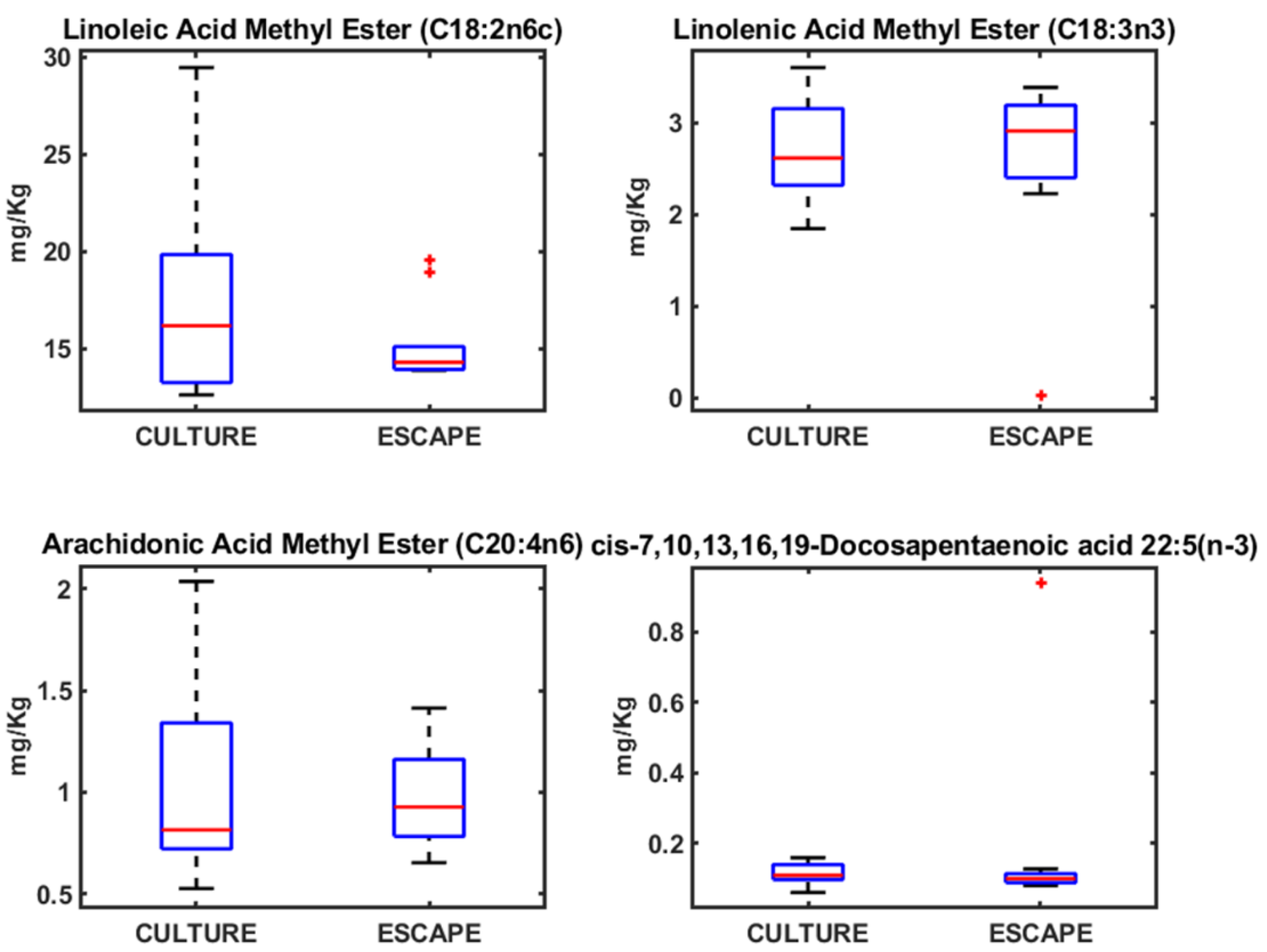

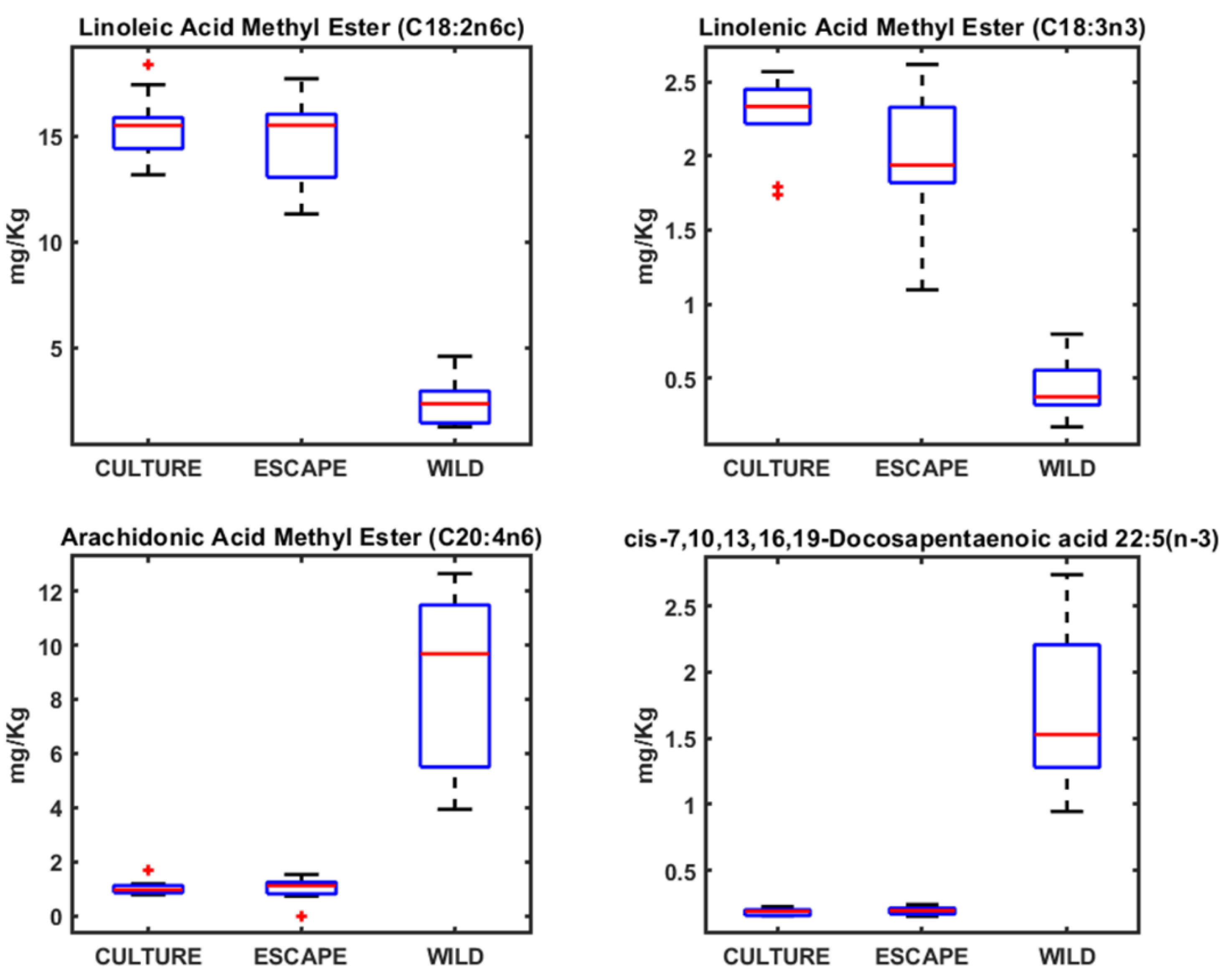

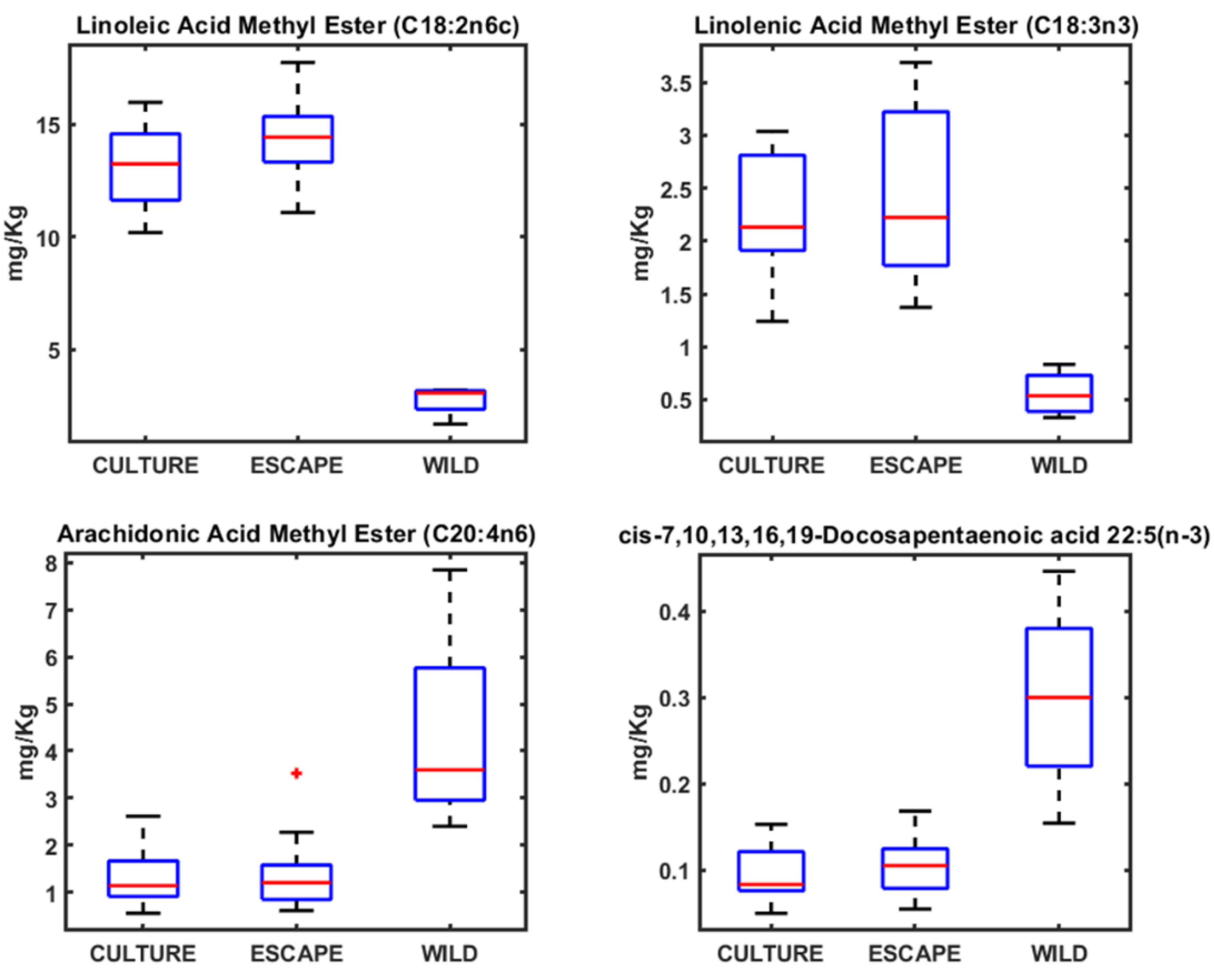

3.2. Fatty Acid Profiles in Seabream, Seabass, and Meagre

3.3. Implications for Food Safety and Traceability

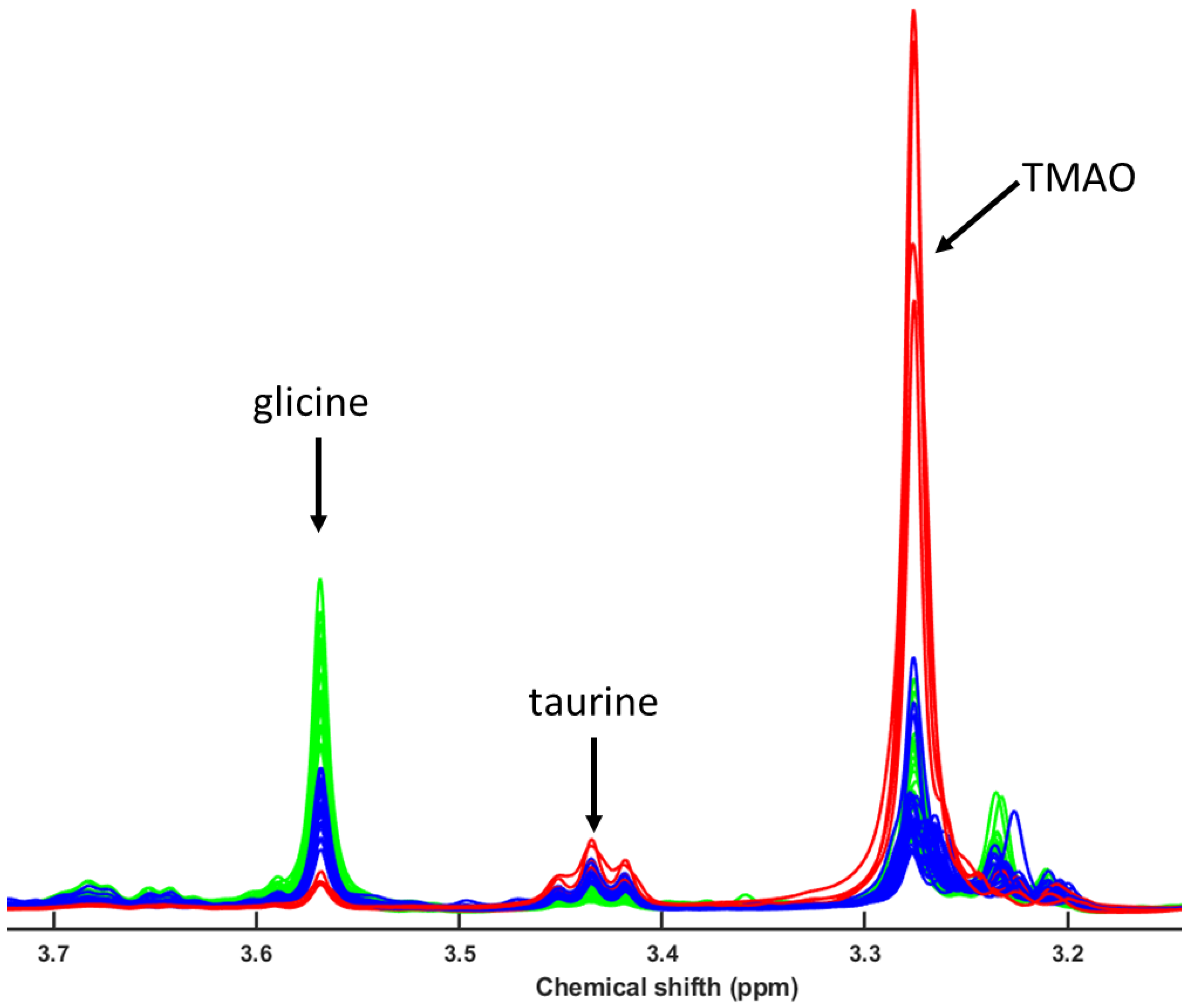

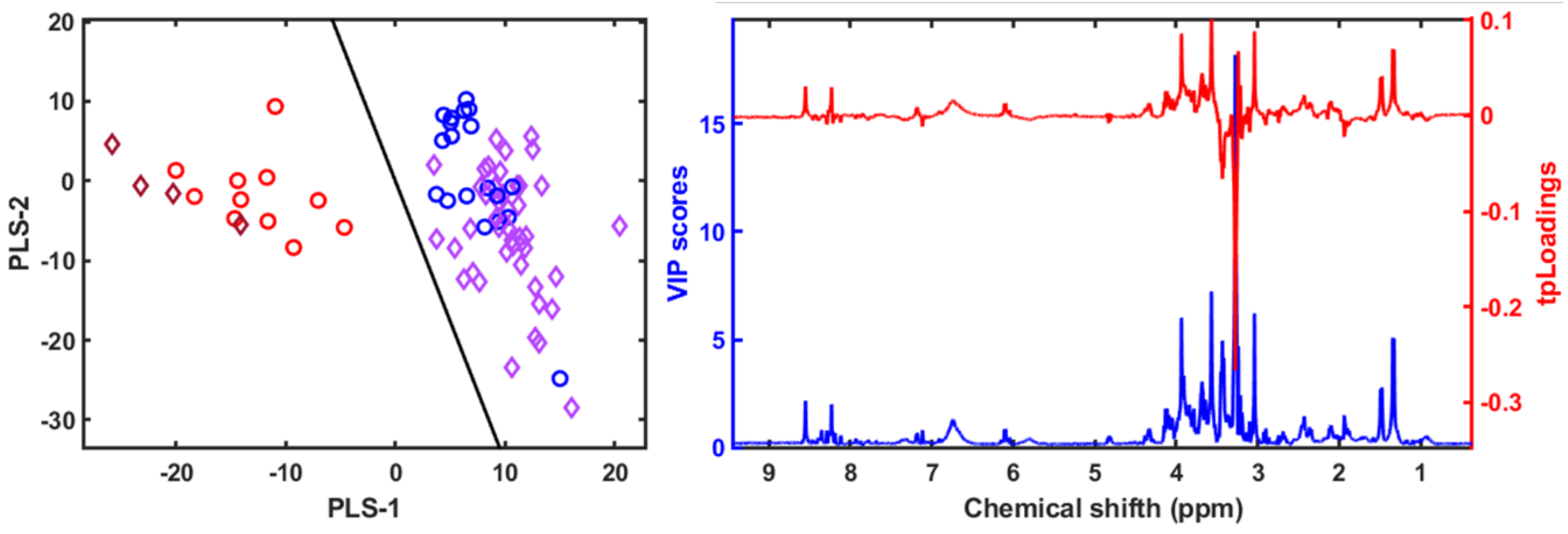

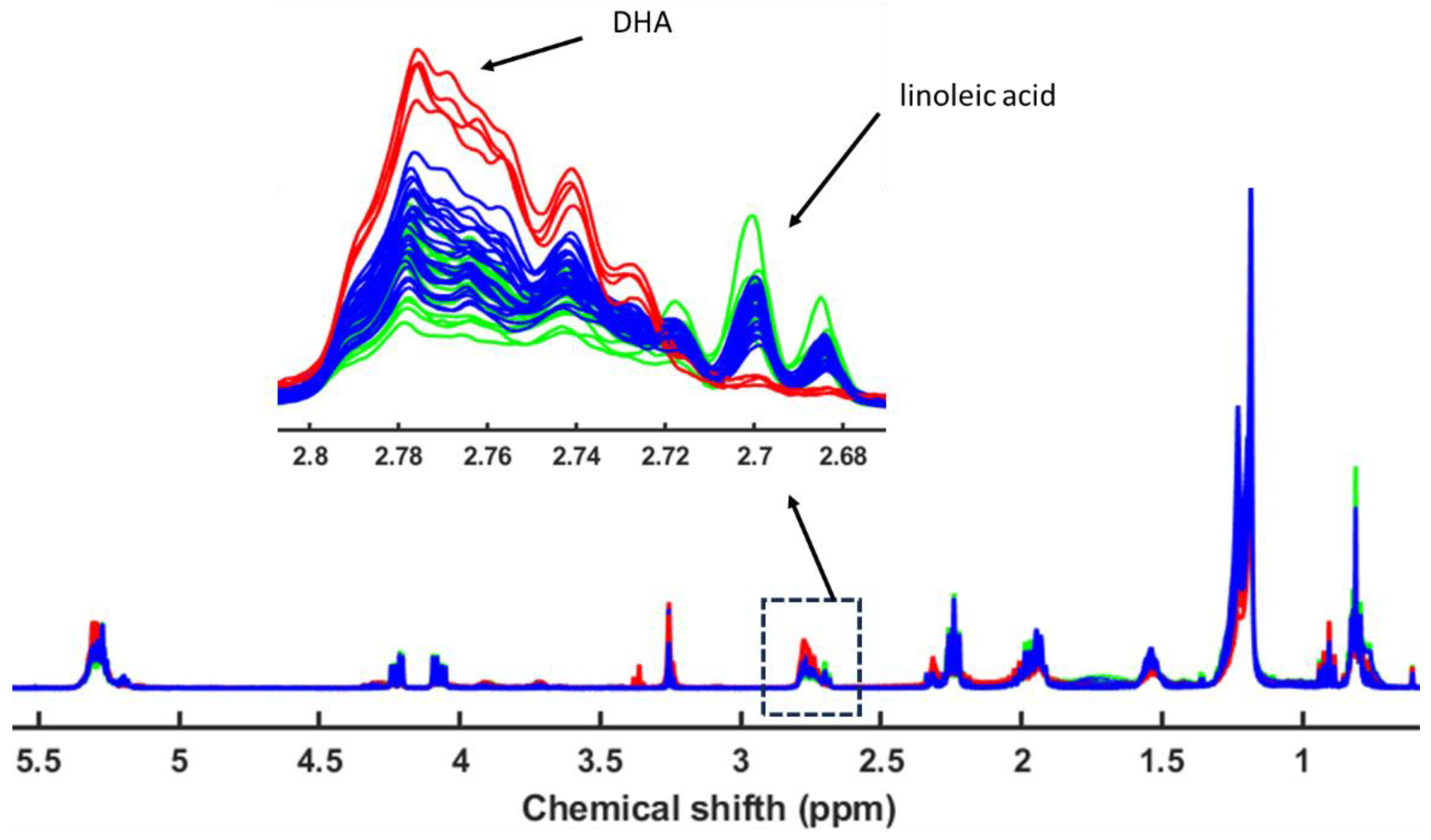

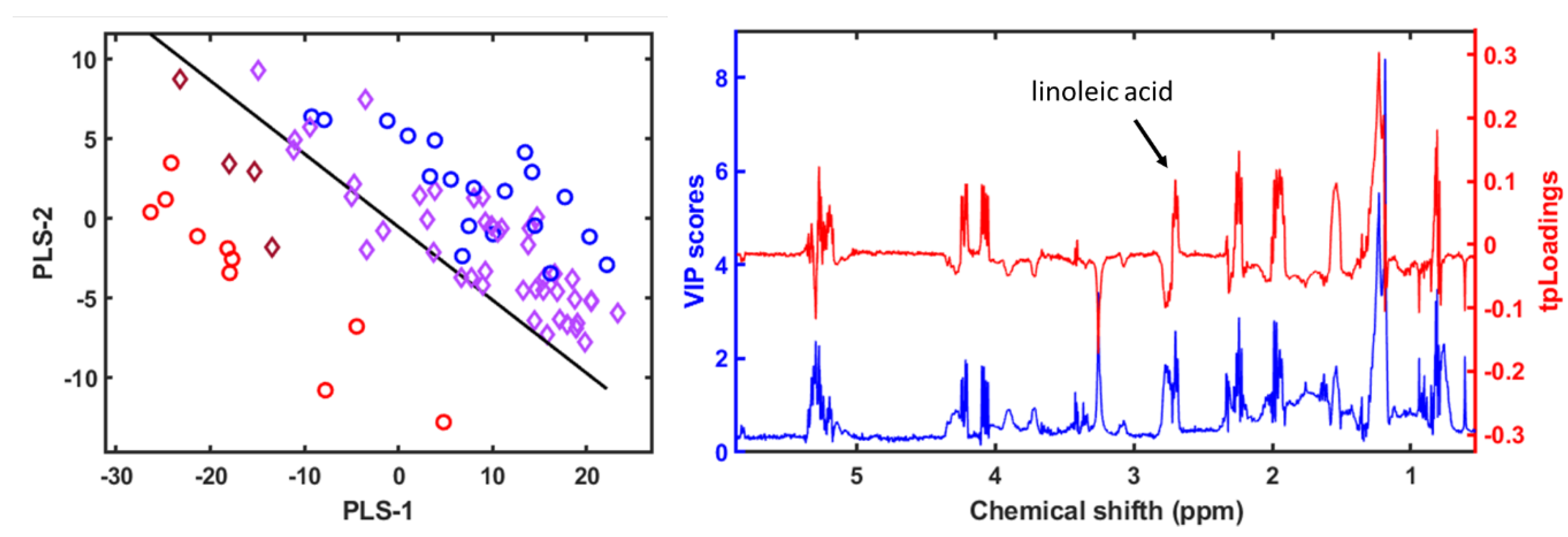

3.4. Metabolomic and Lipidomic Profiling Using NMR

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Makris, C. V., K. Tolika, V. N. Baltikas, K. Velikou and Y. N. Krestenitis. "The impact of climate change on the storm surges of the mediterranean sea: Coastal sea level responses to deep depression atmospheric systems." Ocean Modelling 181 (2023): 102149. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1463500322001639. [CrossRef]

- Lionello, P., I. F. Trigo, V. Gil, M. L. R. Liberato, K. M. Nissen, J. G. Pinto, C. C. Raible, M. Reale, A. Tanzarella, R. M. Trigo, et al. "Objective climatology of cyclones in the mediterranean region: A consensus view among methods with different system identification and tracking criteria." Tellus A: Dynamic Meteorology and Oceanography (2016). [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Guedes, K., J. Atalah, D. Izquierdo-Gomez, D. Fernandez-Jover, I. Uglem, P. Sanchez-Jerez, P. Arechavala-Lopez and T. Dempster. "Domesticating the wild through escapees of two iconic mediterranean farmed fish species." Scientific Reports 14 (2024): 23772. [CrossRef]

- FAO. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture (sofia). Rome, Italy FAO, 2022, #266 p.

- Arechavala-Lopez, P., K. Toledo-Guedes, D. Izquierdo-Gomez, T. Segvic-Bubic and P. Sanchez-Jerez. "Implications of sea bream and sea bass escapes for sustainable aquaculture management: A review of interactions, risks and consequences." Reviews in Fisheries Science & Aquaculture 26 (2018): 214-34. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000428059800006. [CrossRef]

- Badaoui, W., F. C. Marhuenda-Egea, J. M. Valero-Rodriguez, P. Sanchez-Jerez, P. Arechavala-Lopez and K. Toledo-Guedes. "Metabolomic and lipidomic tools for tracing fish escapes from aquaculture facilities." ACS Food Science & Technology 4 (2024): 871-79. [CrossRef]

- Arechavala-Lopez, P., J. M. Valero-Rodriguez, J. Penalver-Garcia, D. Izquierdo-Gomez and P. Sanchez-Jerez. "Linking coastal aquaculture of meagre argyrosomus regius and western mediterranean coastal fisheries through escapes incidents." Fisheries Management and Ecology 22 (2015): 317-25<Go to ISI>://WOS:000358453400006. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D., A. Drumm, S. McEvoy, O. Jensen, D. Mendiola, G. Gabina, J. A. Borg, N. Papageorgiou, I. Karakassis and K. D. Black. "A pan-european valuation of the extent, causes and cost of escape events from sea cage fish farming." Aquaculture 436 (2015): 21-26. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000346088200005. [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Gomez, D., P. Arechavala-Lopez, J. T. Bayle-Sempere and P. Sanchez-Jerez. "Assessing the influence of gilthead sea bream escapees in landings of mediterranean fisheries through a scale-based methodology." Fisheries Management and Ecology 24 (2017): 62-72. <Go to ISI>://WOS:000394962400006. [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R., S. Fang and J. Fanzo. "A global view of aquaculture policy." Food Policy 116 (2023): 102422. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306919223000209. [CrossRef]

- Šegvić-Bubić, T., I. Lepen, Ž. Trumbić, J. Ljubković, D. Sutlović, S. Matić-Skoko, L. Grubišić, B. Glamuzina and I. Mladineo. "Population genetic structure of reared and wild gilthead sea bream (sparus aurata) in the adriatic sea inferred with microsatellite loci." Aquaculture 318 (2011): 309-15. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S004484861100487X. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Segura, L. F., D. Restrepo-Santamaria, J. G. Ospina-Pabón, M. C. Castellanos-Mejía, D. Valencia-Rodríguez, A. F. Galeano-Moreno, J. L. Londoño-López, J. Herrera-Pérez, V. M. Medina-Ríos, J. Álvarez-Bustamante, et al. "Fish databases for improving their conservation in colombia." Scientific Data 12 (2025): 262. [CrossRef]

- Di Bella, C., A. Calagna, G. Cammilleri, P. Schembri, D. Lo Monaco, V. Ciprì, L. Battaglia, G. Barbera, V. Ferrantelli, S. Sadok, et al. "Risk assessment of cadmium, lead, and mercury on human health in relation to the consumption of farmed sea bass in italy: A meta-analytical approach." Frontiers in Marine Science 8 (2021): https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/marine-science/articles/10.3389/fmars.2021.616488.

- Lounas, R., H. Kasmi, S. Chernai, N. Amarni, L. Ghebriout and B. Hamdi. "Heavy metal concentrations in wild and farmed gilthead sea bream from southern mediterranean sea-human health risk assessment." Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 28 (2021): 30732-42. [CrossRef]

- Salem, A. M. and M. E. A. El-Metwally. "Bioaccumulation and health risk potential of heavy metals including cancer in wild and farmed meagre argyrosomus regius (asso, 1801), mediterreanean sea, egypt." Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology and Fisheries 28 (2024): 1277-301. https://ejabf.journals.ekb.eg/article_374235.html. [CrossRef]

- Lenas, D., D. Triantafillou, S. Chatziantoniou and C. Nathanailides. "Fatty acid profile of wild and farmed gilthead sea bream ( sparus aurata )." Journal für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit 6 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Lindon, J. C., J. K. Nicholson and E. Holmes. The handbook of metabonomics and metabolomics. Elsevier Science, 2011.

- Southam, A., A. Lange, R. Al-Salhi, E. Hill, C. Tyler and M. Viant. "Distinguishing between the metabolome and xenobiotic exposome in environmental field samples analysed by direct-infusion mass spectrometry based metabolomics and lipidomics." Metabolomics 10 (2014): 1050-58. [CrossRef]

- Marhuenda-Egea, F. C. and P. Sanchez-Jerez. Metabolomic insights into wild and farmed gilthead seabream (sparus aurata): Lipid composition, freshness indicators, and environmental adaptations. 30. 2025.

- Griboff, J., D. A. Wunderlin and M. V. Monferran. "Metals, as and se determination by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (icp-ms) in edible fish collected from three eutrophic reservoirs. Their consumption represents a risk for human health?" Microchemical Journal 130 (2017): 236-44. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0026265X16302016. [CrossRef]

- O'Fallon, J. V., J. R. Busboom, M. L. Nelson and C. T. Gaskins. "A direct method for fatty acid methyl ester synthesis: Application to wet meat tissues, oils, and feedstuffs." J Anim Sci 85 (2007): 1511-21. [CrossRef]

- Li, H. D., Q. S. Xu and Y. Z. Liang. "Libpls: An integrated library for partial least squares regression and linear discriminant analysis." Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 176 (2018): 34-43<Go to ISI>://WOS:000431936700004. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., A.-J. Miao, N.-X. Wang, C. Li, J. Sha, J. Jia, D. S. Alessi, B. Yan and Y. S. Ok. "Arsenic bioaccumulation and biotransformation in aquatic organisms." Environment International 163 (2022): 107221. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412022001477. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V. K. and M. Sohn. "Aquatic arsenic: Toxicity, speciation, transformations, and remediation." Environment International 35 (2009): 743-59. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412009000051. [CrossRef]

- Valko, M., H. Morris and M. T. D. Cronin. "Metals, toxicity and oxidative stress." Current Medicinal Chemistry 12 (2005): 1161-208. http://www.eurekaselect.com/article/5248. [CrossRef]

- Byeon, E., H.-M. Kang, C. Yoon and J.-S. Lee. "Toxicity mechanisms of arsenic compounds in aquatic organisms." Aquatic Toxicology 237 (2021): 105901. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0166445X21001600. [CrossRef]

- Burger, J. and M. Gochfeld. "Selenium and mercury molar ratios in saltwater fish from new jersey: Individual and species variability complicate use in human health fish consumption advisories." Environmental Research 114 (2012): 12-23. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0013935112000679. [CrossRef]

- Benedito-Palos, L., J. C. Navarro, A. Sitjà-Bobadilla, J. Gordon Bell, S. Kaushik and J. Pérez-Sánchez. "High levels of vegetable oils in plant protein-rich diets fed to gilthead sea bream (sparus aurata l.): Growth performance, muscle fatty acid profiles and histological alterations of target tissues." British Journal of Nutrition 100 (2008): 992-1003. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/AFBDB03ACA2AD6AA3B66016BD4BE5651. [CrossRef]

- Robin, J. H. and B. Vincent. "Microparticulate diets as first food for gilthead sea bream larva (sparus aurata): Study of fatty acid incorporation." Aquaculture 225 (2003): 463-74. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0044848603003107. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H., Q. Ai, K. Mai, W. Xu, J. Wang, H. Ma, W. Zhang, X. Wang and Z. Liufu. "Effects of dietary arachidonic acid on growth performance, survival, immune response and tissue fatty acid composition of juvenile japanese seabass, lateolabrax japonicus." Aquaculture 307 (2010): 75-82. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0044848610003960. [CrossRef]

- Calder, P. C. "The relationship between the fatty acid composition of immune cells and their function." Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids 79 (2008): 101-08. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0952327808001361. [CrossRef]

- Furne, M., E. Holen, P. Araujo, K. K. Lie and M. Moren. "Cytokine gene expression and prostaglandin production in head kidney leukocytes isolated from atlantic cod (gadus morhua) added different levels of arachidonic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid." Fish & Shellfish Immunology 34 (2013): 770-77. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1050464812004470. [CrossRef]

- Hardy, R. W. and C.-s. Lee. "Aquaculture feed and seafood quality." Bulletin of Fisheries Research and Development Agency 31 (2010): 43-50.

- Ralston, N. V. C. "Selenium health benefit values as seafood safety criteria." EcoHealth 5 (2008): 442-55. [CrossRef]

- Melis, R., R. Sanna, A. Braca, E. Bonaglini, R. Cappuccinelli, H. Slawski, T. Roggio, S. Uzzau and R. Anedda. "Molecular details on gilthead sea bream (sparus aurata) sensitivity to low water temperatures from 1h nmr metabolomics." Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 204 (2017): 129-36. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1095643316302574. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, I., T. Bathen, I. Standal, J. Halvorsen, M. Aursand, I. Gribbestad and D. Axelson. "Bioactive compounds in cod (gadus morhua) products and suitability of h-1 nmr metabolite profiling for classification of the products using multivariate data analyses." Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 53 (2005): 6889-95. [CrossRef]

- Yancey, P. H., A. L. Samerotte, G. L. Brand and J. C. Drazen. "Increasing contents of tmao with depth within species as well as among species of teleost fish." Integrative and Comparative Biology 44 (2004): 669-69<Go to ISI>://WOS:000226721401179.

- Solé-Jiménez, P., F. Naya-Català, M. C. Piazzon, I. Estensoro, J. À. Calduch-Giner, A. Sitjà-Bobadilla, D. Van Mullem and J. Pérez-Sánchez. "Reshaping of gut microbiota in gilthead sea bream fed microbial and processed animal proteins as the main dietary protein source." Frontiers in Marine Science 8 (2021): https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2021.705041. [CrossRef]

- Quero, G. M., R. Piredda, M. Basili, G. Maricchiolo, S. Mirto, E. Manini, A. M. Seyfarth, M. Candela and G. M. Luna. "Host-associated and environmental microbiomes in an open-sea mediterranean gilthead sea bream fish farm." Microbial Ecology 86 (2023): 1319-30. [CrossRef]

- Kunkel-Patterson, A., J. C. Fiess, L. Mathias, A. Samerotte, T. Hirano and P. H. Yancey. "Effects of salinity and temperature on osmolyte composition in tilapia." Integrative and Comparative Biology 45 (2005): 1156-56<Go to ISI>://WOS:000235337601284.

- Samerotte, A. L., J. C. Drazen, G. L. Brand, B. A. Seibel and P. H. Yancey. "Correlation of trimethylamine oxide and habitat depth within and among species of teleost fish: An analysis of causation." Physiological and Biochemical Zoology 80 (2007): 197-208<Go to ISI>://WOS:000243966400004. [CrossRef]

- Treberg, J. R. and W. R. Driedzic. "Maintenance and accumulation of trimethylamine oxide by winter skate (leucoraja ocellata):: Reliance on low whole animal losses rather than synthesis." American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology 291 (2006): R1790-R98<Go to ISI>://WOS:000241768400027. [CrossRef]

- Yancey, P. H. "Organic osmolytes as compatible, metabolic and counteracting cytoprotectants in high osmolarity and other stresses." Journal of Experimental Biology 208 (2005): 2819-30. 10.1242/jeb.01730. [CrossRef]

- Schrama, D., M. Cerqueira, C. S. Raposo, A. M. Rosa da Costa, T. Wulff, A. Gonçalves, C. Camacho, R. Colen, F. Fonseca and P. M. Rodrigues. "Dietary creatine supplementation in gilthead seabream (sparus aurata): Comparative proteomics analysis on fish allergens, muscle quality, and liver." Frontiers in Physiology 9 (2018): https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physiology/articles/10.3389/fphys.2018.01844. [CrossRef]

- Teles, A., L. Guzmán-Villanueva, M. A. Hernández-de Dios, M. Maldonado-García and D. Tovar-Ramírez. "Taurine enhances antioxidant enzyme activity and immune response in seriola rivoliana juveniles after lipopolysaccharide injection." (2024):.

- Sampath, W. W. H. A., R. M. D. S. Rathnayake, M. Yang, W. Zhang and K. Mai. "Roles of dietary taurine in fish nutrition." Marine Life Science & Technology 2 (2020): 360-75<Go to ISI>://WOS:000649454300005. [CrossRef]

- Houston, S. J. S., V. Karalazos, J. Tinsley, M. B. Betancor, S. A. M. Martin, D. R. Tocher and O. Monroig. "The compositional and metabolic responses of gilthead seabream (sparus aurata) to a gradient of dietary fish oil and associated n-3 long-chain pufa content." British Journal of Nutrition 118 (2017): https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/84301CB4F616131CACB2C2E07141C1C1. [CrossRef]

- Stubhaug, I., D. R. Tocher, J. G. Bell, J. R. Dick and B. E. Torstensen. "Fatty acid metabolism in atlantic salmon (salmo salar l.) hepatocytes and influence of dietary vegetable oil." Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 1734 (2005): 277-88. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1388198105000880. [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, M. S., A. Obach, L. Arantzamendi, D. Montero, L. Robaina and G. Rosenlund. "Dietary lipid sources for seabream and seabass: Growth performance, tissue composition and flesh quality." Aquaculture Nutrition 9 (2003): 397-407. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).