1. Introduction

Language ability is the most fundamental function of psychological life, bar none. I once took a course called Ancient Greek Philosophy, in which the creation of the Greek gods was discussed one by one. Among them, both Apollo and Hermes had some involvement with language, though it was not their main domain. I believe the ancient philosophers missed creating a dedicated god responsible solely for language. This may be because the creation of gods stems from awe of the unknown. However, the god of language is always with us, approachable and familiar, which diminishes people’s sense of reverence. In reality, language and linguistic behavior are the most mysterious entities in human life and in the universe. Though we think we know them well, they remain strangers to us, with their mysteries being among the hardest puzzles, incomparable even to the Millennium Problems of mathematics or the enigma of Einstein’s unified field theory.

It is often said that words reveal the person. Language affects the largest expanse of psychological phenomena in people, becoming the foundation upon which psychological life depends. Many things in the world arise from language. From household affairs to international relations, language can transform conflict into peace, but it can also cause misunderstandings, intensify contradictions, and lead to verbal battles. Human rationality comes from language; human emotions are influenced by language; human knowledge is accumulated through language; human cognition is passed down via language; human thought is filled with content through language; human information is transmitted by language; human communication is inspired by language; human interactions are executed through language. For individuals, "I speak, therefore I am"; for societies, without language, how could anything be shared? All of these layers are veiled, and the truth behind them is as elusive as the fog-shrouded peaks of Mount Lu. On one hand, language is omnipresent; on the other hand, linguistic behavior is richly diverse. How much do we truly understand about the interactions between language and linguistic behavior?

In short, language is a force, rippling through the psyche like a wave, a form of psychological vitality. Language is also a carrier of force, breaking into particles, with each particle coupling and interacting, forming the continuous cycle of psychological life. Language is a field, with fields interacting, revealing the ontological commitments of psychological reality. Language is an operator, acting upon mental intentions and revealing the contents of the mind’s cognition. Language is energy, sustaining psychological activities and reflecting the quality of mental life. Finally, language is a kind of metalogic, capable of generating self-referential statements, guiding psychological life towards reflection and introspection.

This paper’s discussion of language follows three intertwined threads. The first thread is the specific manifestations and new influences of Bourbaki structuralism in the analysis of language and linguistic behavior. The second thread is the modeling power and marvelous effects of theoretical physics in language and linguistic behavior. The third thread is the historical evolution and fresh interpretations of Wittgenstein’s philosophy of language. These three threads weave through one another, leading us to glimpse some previously undisclosed secrets of the linguistic world. Interestingly, Wittgenstein’s philosophical development can be embedded into the framework of gauge field theory. Gauge field theory distinctly separates the global and local levels. Early Wittgenstein focused on the global structure of language, while his later work shifted to local analyses of linguistic behavior. This remarkable convergence enhances our understanding of the period in which language plays a central role in psychological life.

Here is the structure of this paper. The entire text is divided into three parts:

The first part is titled:

Early Wittgenstein’s Philosophy of Language, Equilibrium, and Global Structure. This section discusses the prescriptiveness, stability, and certainty of language, especially scientific language. Within the framework of early Wittgenstein’s philosophy of language, these properties were the pursuits and inquiries of his youth. In the framework of Newtonian mechanics, these properties are closely connected to the concept of equilibrium and can be characterized within that framework. Within the framework of gauge field theory, these properties are intricately linked to the global level and are modeled accordingly. We will discuss a fundamental special linguistic structure, namely the "dual-leg structure" composed of syntax and semantics. This dual-leg structure can serve as a tool for characterizing language across logical language [

2], decision theoretic language [

9], game theoretic language [

6], quantum mechanics language [

4], gauge field theory language [

1], intrinsic dynamical geometrized language [

14], and more. These topics will be introduced in

Section 2,

Section 3,

Section 4,

Section 5 and

Section 6.

The second part is titled:

Wittgenstein and Gödel: Disputes and Turning Points. The dual-leg structure of language is not just for posing and taking pictures but enables the running function of language. So, is this dual-leg structure sound, with both legs of equal length, or is one leg longer than the other? In logic, this is called metaproperties, or the overall properties of a system. The study of system metaproperties is called metalogic or metamathematics. The famous Gödel incompleteness theorem and Tarski indefinability theorem, also known as the twin theorems, reached the pinnacle of constructing a dual-leg structure [

2], according to Bourbaki structuralism, and revealed the asymmetrical dual-leg structure that demonstrates the beauty of linguistic structure, like the Venus de Milo. In theoretical physics terms, the twin theorems represent the spontaneous symmetry-breaking mechanism of a language system at the global level. This is a metaproperty of linguistic structure. The debates between late Wittgenstein and Gödel foreshadowed Wittgenstein’s shift towards the localization of language systems and his focus on individual linguistic behavior, opening a new chapter in behaviorist linguistics. As a mental coordination of the dual-leg structure of syntax and semantics, this turn in Wittgenstein’s philosophy of language also paved the way for pragmatics and psycholinguistics [

7]. This part will be discussed in

Section 7,

Section 8 and

Section 9.

The third part is titled:

Beyond Wittgenstein: Structure and Models. Language games are a representative concept in Wittgenstein’s philosophy of language [

12], meaning that language communication can be viewed as language games. Wittgenstein even believed that language games themselves are language because language reflects forms of life. Language games and forms of life are mutually transformed through psychological games [

13]. However, in his middle period, Wittgenstein found it difficult to define language games with a complete set of rules, which led him to become a leader of 20th-century skeptical philosophy. In his later period, Wittgenstein turned to the view that language games should follow rules and strove to find them [

10]. The present author believes that Wittgenstein was a hero who didn’t quite complete his work, and this paper aims to offer some assistance.

The deep structure of language games is closely related to pragmatics, and their modeling exceeds the scope of this paper. This paper provides several modeling pathways for their surface structure. It discusses how, in an epistemological sense, Wittgenstein differs from the Platonic tradition. Language games vary by person, situation, and context, showing clear local characteristics in their structure. Because of this, they must follow causality and be limited in scope, which can be modeled by special relativity. Linguistic behavior is sensitive to sequence; the order in which things are said affects their impact. Even in rhetoric, there is sensitivity to sequence that word order affects meaning. This implies that the observation of linguistic behavior does not satisfy commutative relations but rather satisfies non-commutative relations. This is a condition for quantization and can be modeled by quantum mechanics. In fact, language games are themselves wave functions and are characterized by quantum field theory [

4]. Linguistic behavior is socialized. In language world, individual language abilities vary, and linguistic advantage is a scarce resource. This means that language society is a competitive and unequal society. Standard educational tests are a typical example of this analysis. This level of analysis can be modeled by general relativity. The topics mentioned above will be discussed in

Section 10 through 13. The paper concludes with a general discussion.

Part I: Early Wittgenstein’s Philosophy of Language: Equilibrium and Global Structure

1. The Dual-Leg Structure of Language

Human society cannot function without the service of language. Do you know that, in order to support this linguistic service, scientists, including linguists, psychologists, philosophers, cognitive scientists, and others, have long worked diligently on language maintenance? Early Wittgenstein, following the lead of logician Russell, engaged in such language maintenance, a discipline called the philosophy of language. From the distinction between syntax/grammar and semantics, we can abstract the concept of a dual-leg structure for language, which helps us understand why language exhibits stability and certainty. The balance of this dual-leg structure is akin to the concept of equilibrium in Newtonian mechanics. In a sense, the demand for the stability and certainty of language echoes the Newtonian scientific tradition, continuing in its vein. The characteristics of the Newtonian scientific tradition mentioned here generally refer to the direct observability of phenomena, the certainty of theories, and the stability of systems. Building bridges and railways, calculating ballistic trajectories, or even constructing tables and chairs all involve Newtonian mechanics. Newtonian mechanics satisfies most of our physical needs in daily life. Similarly, ordinary linguistic expressions can meet most of our everyday communicative needs. Whether chatting with others, speaking in meetings, buying goods at the supermarket, sending emails, discussing things on WeChat, writing a blog post, or even writing an exam essay, clear expression is required so that people can understand and comprehend. In the terminology of psycholinguistics, it means that linguistic behavior must be directly observable. If someone speaks or writes with lexical, syntactic, and grammatical confusion, lacking logic and clarity, they will be regarded as linguistically incompetent.

The stability of natural language relies on the stability of its syntactic and grammatical structure, while its certainty is reflected in the certainty of its semantics [

10]. Clearly, the stability and certainty of natural language are based on the separation of its syntactic/grammatical structure from its semantics. This separation isn’t something granted; it represents a high stage of linguistic evolution. People often overlook how miraculous the formation of syntactic and grammatical structures is in the evolution of human language, akin to humans taking on divine work. Even more incredible is that humans also invented semantics, thereby determining the meaning of linguistic expressions—truly a masterpiece of ingenuity. This allowed humans to learn to stand and walk with just two linguistic legs in the mental world, freeing up the two mental hands to handle more complex tasks. Upright walking is a milestone in human evolution, as is the evolution of human language.

My doctoral advisor, the late Professor Martin D. S. Brain of the Department of Psychology at New York University, was an authoritative scholar in two fields: reasoning psychology and developmental psychology. In reasoning psychology, he built the theory of mental logic [

3] and developed experimental methods. In developmental psychology, he became famous for his research on children’s language acquisition. The theory of mental logic posits that people reason using reasoning patterns based on linguistic abilities, automatically triggered during reading comprehension. Therefore, the theory of mental logic is also regarded as a syntactic reasoning theory.

Cognitive revolution pioneer Noam Chomsky first distinguished between linguistic competence and performance. Chomsky believed that humans possess an innate internal configuration for language acquisition, unique to the human species and the result of long-term evolution. A four-year-old child can freely communicate using language, not merely due to four years of language acquisition but due to this internal linguistic configuration. You cannot train any other species to acquire language because they lack the necessary internal configuration. So, how do children activate this internal configuration and exhibit linguistic performance? This was once a mystery. Professor Brain continuously observed his own children’s language development. He found that children, before formally learning conventional grammar, autonomously generate a child grammar in advance to facilitate language performance. This child grammar demonstrated the relative stability of children’s language, making communication possible—a finding that became Brain’s hallmark work.

My postdoctoral advisor, former Princeton University Professor of Psychology, Philip Johnson-Laird, proposed and developed the theory of mental models [

5], asserting that people reason by constructing mental models. The construction of these mental models is based on the reasoner’s understanding of the meaning of premise sentences, which, in turn, is based on their perception of language. Another cognitive revolution pioneer, Professor George Miller, was also one of the founders of psycholinguistics. Miller and Johnson-Laird co-authored the magnum opus

Language and Perception [

8], which I believe was actually the prelude to the theory of mental models. I asked Professor Johnson-Laird about this more than 20 years ago, and he didn’t agree. Opinions of academic authorities should be regarded as references but not taken as gospel. For example, he also once said that there were no quantum events in the mental world—a view I obviously cannot endorse. Academic authorities have their strengths but also their limitations. At the same time, the formal representation of mental models bears comparability to logical semantics. Thus, the theory of mental models is regarded as a semantic reasoning theory. Together, the theories of mental logic and mental models provide syntactic stability and semantic certainty to reasoning psychology. Reasoning is the core capability of the mind and is also its representative linguistic performance. In experimental psychology, reasoning tasks are always linguistic tasks.

The stability and certainty brought about by the syntactic/grammatical structure and semantics of language—i.e., the so-called dual-leg structure of language—are even more evident in formal languages and scientific languages. I often tell my students that when learning a subject, the first step is to familiarize themselves with the language of the subject, then separate the syntactic/grammatical structure from the semantics, and finally comprehend the metaproperties that combine the two. In my courses, I analyze at least eight such scientific languages with dual-leg structures. The first involves logic, the second involves decision theory [

2], the third involves game theory [

6], the fourth involves metamathematics, the fifth involves quantum mechanical wave functions [

4], the sixth involves gauge field theory [

1], the seventh involves set theory [

15], and the eighth involves the geometrization program of the Standard Model of particle physics [

14].

In the kingdom of scientific languages, logic was the first discipline to use the dual-leg structure of language to stand upright and walk. Contemporary formal logic [

5], also called standard or symbolic logic, is characterized by various formal systems. A logic system is a formal system with its own specially designed formal language. There are three basic levels for analyzing natural language in logical terms. The simplest is propositional logic, also known as propositional calculus. Another level is quantifier predicate logic, and yet another level is modal logic.

2. The Standard "Dual-Leg" Structure of Logic and Formal Language

2.1. Propositional Logic and the Truth-Value Semantics

Consider the following sentence: "If all the beads are red, then Tom plays games with some girls." At the level of propositional logic, a simple statement such as "all the beads are red" is treated as a whole, called a proposition, without delving into its internal syntactic structure. Words that logically connect sentences are called logical connectives or logical operators, including conjunction (and), disjunction (or), implication (if-then), equivalence (if and only if), and negation (not). Thus, in the vocabulary of propositional logic, there are countably infinite propositional variables, five logical connectives, and parentheses used as punctuation marks. With these symbolized words, an infinite number of finite symbol strings can be formed. To mechanically determine which symbol strings are grammatically proper formulas—both atomic and compound—and which are improper, ungrammatical formulas, we need a set of formation rules. Formation rules must, and can only, be inductively defined. Logic studies reasoning, and deductive reasoning proceeds from given premises step by step to derive conclusions. Each step in the reasoning process applies a rule of inference, known as a proof. As we can see, the formal syntax of propositional logic language consists of a vocabulary, formation rules, and inference rules.

So, what is the logical meaning of this set of propositional logic syntax? In logic, there is only one logical meaning: truth or falsity, known as truth-value. Only sentences that can be evaluated as true or false are considered propositions; this is called the propositional attitude. The semantics of propositional logic is called truth-value semantics. The propositional variables in a propositional logic system are called atomic formulas. Truth-value semantics defines how the truth-values of finite compound formulas of any complexity are derived from the truth-values of atomic formulas. Truth-value semantics is governed by a truth table. Specifically, a conjunction is true if and only if both conjuncts are true; a disjunction is false if and only if both disjuncts are false; a conditional is false if and only if the antecedent is true and the consequent is false; an equivalence is true if and only if the two components have the same truth-value; and, finally, a formula and its negation have opposite truth-values.

Do not underestimate this seemingly simple truth table—it has played a landmark role in the history of modern science. First, it was the first truly scientific semantics, separating and formalizing the theory of meaning. Second, it defined the logical meaning of the five logical connectives, which (and, or, if-then, if and only if, and not) represent the core expressive functions of natural language. It is hard to imagine how impaired natural language would be without these five connectives, or how chaotic communication would become if they were ambiguous. Furthermore, replacing truth with 1 and falsity with 0 transforms the truth table into Boolean algebra. Boolean algebra is the foundation of computer science and the prototype of "and-not gates" in circuit design, including integrated circuits.

In the discourse of logic, there are two central concepts. One is "proof," which is purely syntactic; the other is "validity," which is purely semantic. Some authors even argue that logic is the science of validity. Validity is defined by a conditional statement: if all the premises of an argument are true, then the conclusion must also be true. In other words, if a false premise is introduced in an argument, the reasoning remains valid regardless of whether the conclusion is true or false.

Thus, the dual-leg structure of a logical system consists of two standard components: formal syntax and formal semantics (also called a model). Standard logic has its logical standard, requiring that its syntactic structure and semantics be dually equivalent. This dual equivalence is established through the relationship between provability and validity. If all proofs are valid, we say the logical system is semantically sound. If all valid formulas or arguments are provable, we say the system is complete. Therefore, soundness and completeness describe the overall properties of a logical system, also known as metaproperties. They act like a two-way bridge connecting logical syntax with its semantics, even though the two are constructed independently. Propositional logic possesses both soundness and completeness.

2.2. Quantified Predicate Logic and the Value-Assignment Semantics

Building upon propositional logic, quantifier predicate logic delves into the internal structure of sentences. Consider again the previous example: "If all the beads are red, then Tom plays games with some girls." In this sentence, "are red" is expressed by a unary predicate (to be) paired with an adjective (red), representing a property. Additionally, "plays games" (more precisely, "plays") is a binary predicate, indicating a relationship between Tom and some children. The beads and children are individual variables, while Tom is an individual constant. "All" serves as a universal quantifier, and "some" is an existential quantifier. It is also important to note that in English, the sentence contains a definite article, "the," which often functions as a pronoun. By adding these components to the formal language’s vocabulary, along with appropriate formation and inference rules, we obtain the formal syntax of quantifier predicate logic.

The additional syntactic content here clearly surpasses the explanatory scope of propositional logic’s truth-value semantics. This necessitates the creation of a new semantics for predicate logic, known as valuation semantics, or a new model. To achieve this, we must first introduce a universal domain of individuals—essentially, the set of all things, including both real entities and any imaginable objects. Then, for each predicate, we specify a truth condition. For example, in the case of a unary predicate, its truth condition is a subset of the universal domain. A universal statement, such as "all things are red," is true if and only if its truth-condition set equals the universal domain. Similarly, an existential statement like "some things are red" is true if and only if its truth-condition set is non-empty, and so on. In 1930, Gödel proved that first-order predicate logic is complete—i.e., every valid formula is provable. Predicate logic is highly powerful and encompasses a significant portion of mathematical language.

2.3. Modal Logic and Possible World Semantics

In standard propositional and predicate logic, the focus is on declarative statements that do not include modal words (also called modal operators). Modal words encompass concepts such as: possibility, necessity, obligation, permission, duty, subjunctive mood, conditionals, tense, etc. These modal expressions enrich natural language, giving it flexibility, varied functionality, and the ability to express nuances appropriately, providing room for negotiation and adaptation. By introducing modal words into standard logic and establishing corresponding formation and inference rules, we create the syntactic structure of modal logic.

The semantics of modal logic is known as possible world semantics. For instance, the possible world semantics for modal propositional logic consists of a set of possible worlds and a binary accessibility relation defined over them. Depending on the specific axiomatization, this accessibility relation must satisfy particular properties, such as transitivity or reflexivity. For example, a necessary statement, "necessarily A," is true in a certain possible world if and only if statement A is true in all possible worlds accessible from that world. Conversely, a possible statement, "possibly A," is true in a certain possible world if and only if there exists at least one accessible world where statement A is true. This possible world semantics is also called Kripke semantics, named after Princeton logician Saul Kripke, who introduced the concept of accessibility relations and proved a form of completeness for modal logic.

In scientific languages, traditionally, there hasn’t been a clear distinction between syntactic and semantic structures. These scientific languages, akin to mermaids in water—elegant and mesmerizing—are often aesthetically appealing but distant and difficult to approach. How do we know that these mermaids don’t wish to evolve legs and walk on land, dancing with humanity? I can often sense the mermaid’s lament—the scientists, frolicking on land, have left her confined to her watery palace. Whether in the dim green lights of the deep sea or the shimmering blue rays of shallow waters, she gazes longingly, wondering where the human world is. Finally, a linguistic surgeon, armed with a scalpel, pioneered a method for constructing "legs" for scientific language.

My teaching experience shows that students grasp scientific language more easily when it is endowed with this dual-legged structure. Whenever I begin learning a new field, my first task is to familiarize myself with its language and identify its dual-legged structure and meta-properties. My progress in understanding certain areas in recent years, particularly while contemplating theoretical physics puzzles, has been greatly aided by this approach. This is a habit innate to logicians.

3. Decision Theory Syntax Structure and Its Utility Semantics

The classical axiomatized decision theory syntax is structured in three layers. The first layer consists of a set of choices or options. The second layer states that each choice can lead to a set of possible outcomes. The third layer indicates that each outcome is characterized by two and only two attributes: desire and feasibility. To formulate a decision theory problem, one must place the issue within this syntactic structure. Solving a decision theory problem involves establishing a total order preference relation over the set of choices, meaning that for any two choices, one must be preferred, and "non-preference" is not allowed. Preference is a syntactic concept. We can observe that the classical decision theory syntax’s vocabulary consists of five and only five concepts: choice, outcome, desire, feasibility, and preference. These are organized into a three-layer grammatical structure and resolution conditions. If any concept is missing, it does not form a classical decision problem. If there is an extra concept, it indicates that the decision problem has not been properly refined. So, what does classical decision theory mean, and how is a classical preference relation established? This is a semantic inquiry.

The classical decision theory syntax is constructed from the top down, while its semantics are defined from the bottom up. First, the decision-theoretic meaning of "desire" is reduced to a single value: money. No matter what the desire is, within the framework of decision theory, it must be converted into a monetary value. You may find this statement uncomfortable, perhaps feeling insulted—thinking, "Do you take me for a materialist? I love my country, which is priceless! I have my faith, which is unconditional!" This is understandable. However, people typically don’t say, "I decided to love my country," as love for one’s country is an ethical issue. Nor do people typically say, "I decided to believe in God," as that is a religious issue. Ethics and religion fall outside the boundaries of decision theory. This is the boundary of decision theory: a theory without boundaries is not scientific, and a science without clear boundaries is not a mature discipline.

The next concept is the feasibility of a possible outcome. If you want to buy a new car, or even to buy an entire car company, the feasibility of these two options is evidently different. The natural mathematical representation of feasibility is probability. However, in standard probability theory, a single independent event cannot have a probability assigned. Of course, psychology has theories about subjective probability, which assign a probability to isolated independent events, often referred to as likelihood, but this is not suitable for inclusion in standard decision theory. Note that a single choice can lead to several or even many possible outcomes, and decision-makers assign different weights to these potential outcomes based on their importance. This distribution of weights is called a strategy. To convert this strategy into a probability distribution, a mathematical normalization process is applied, ensuring that the sum of all probabilities equals 1. The reason is that all possible outcomes belong to the same choice, and if this choice is seen as the optimal preference, it becomes reality, and the probability of a real event is 1. With this normalized probability distribution, it becomes possible to assign a probability to each possible outcome. Thus, we can say that the decision-theoretic semantics of syntactic feasibility is its probability.

A possible outcome is characterized by its syntactic attributes of desire and feasibility. The decision-theoretic semantics of desire is monetary value, and the semantics of feasibility is probability. The product of these two values is called utility. Hence, the decision-theoretic semantics of a syntactic possible outcome is its utility. This is the origin of the name "utility semantics" in decision theory. This is the second layer, called the outcome layer. Moving one layer up brings us back to the choice layer. A single choice can produce several or many possible outcomes, each of which has its own utility. The sum of these utilities is called the mathematical expectation. Therefore, the decision-theoretic semantics of a syntactic choice is its mathematical expectation.

It should be emphasized that money is a number, probability is a number, and their product, utility, is also a number. Adding utilities still results in a number. Thus, utility semantics is also called numerical semantics. The meta-properties of the decision theory system require that its syntactic structure and utility semantics be precisely balanced—neither more nor less, but just right. This meta-property is expressed by the decision theory representation theorem: for any two choices, one is preferred over the other if and only if the mathematical expectation of the first choice is greater than that of the second. It is evident that requirements for such meta-properties are modeled on those found in standard logic. Why use numerical semantics to explain decision theory syntax? The reason is that we are not always clear on what the preference relation between two choices means and find it difficult to determine, but we do understand what it means for one number to be greater than another. Using the latter to explain the former is the function of semantics.

4. Game Theory Syntax Structure and Its Utility Semantics

In their classic work Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (1944), von Neumann and Morgenstern developed game theory, defining the concept of a game and clearly distinguishing between cooperative and non-cooperative games, thereby laying the foundation for game theory. However, modern game theory truly flourished under what is known as the Nash framework. Nash not only rigorously defined cooperative and non-cooperative games using mathematical language but also proved systemic meta-properties, such as the Nash solution and Nash equilibrium, establishing the basic framework for game theory research.

The syntactic structure of non-cooperative games is not complex, but conceptually, there is a challenge. First, assume there are players. Second, each player has a set of possible actions, denoted as . This is similar to individual decision theory and poses no cognitive difficulty. Third, consider an -tuple of possible actions , where each player contributes an action from their own set of possible actions. This -tuple is called a scenario. A game is the set of all possible situations, which is the Cartesian product of the action sets of all players, denoted as . This is akin to a film, composed of individual frames. The essential difference from individual decision theory is that each player does not establish a preference relation over their own set of possible actions but must establish a preference relation over the set of all situations. This can cause cognitive discomfort for players because the mind is embodied in individuals, making it more natural in individual decision theory for decision-makers to establish preferences over their own action sets. Now, each player must establish preferences between any two situations, each involving the possible actions of all other players. This is the psychological reason behind the cognitive discomfort. Based on my teaching experience, once this cognitive discomfort is overcome, the language of game theory becomes more accessible.

The meta-property of non-cooperative games is the well-known Nash equilibrium, a purely syntactic property. A Nash equilibrium is a special situation, denoted

, that must hold to each player

. It satisfies the following condition:

The game-theoretic meaning of a situation is called utility. Similar to decision theory, utility is also a linear function of value and probability, so the semantics of non-cooperative games is called utility semantics. Note that, unlike in decision theory, assigning a value or probability to an individual action within a situation has no meaning. What matters is assigning a set of values and a normalized probability distribution to all actions within a situation simultaneously. Few people notice an interesting phenomenon: the "two-legged" structure of game theory also manifests in the distinction between the modes of expression of non-cooperative and cooperative games.

Cooperative games are characterized by a set of possible agreements. For example, in a two-person negotiation, the process of bargaining forms a price pair, denoted , which represents a possible agreement. In theory, there can be many possible agreements. An important concept in cooperative games is the negotiable point, or more colloquially, the "turning point." Understandably, not all possible agreements are negotiable. If or else is too large—i.e., if the values of and are too disparate—one party may lose interest in negotiating. Therefore, there should be a turning point that defines the range of negotiable agreements. Within this range, there exists a special possible agreement called the Nash solution, which maximizes the product of the two values, making it greater than the corresponding products of other possible agreements within the negotiable range.

The above describes how standard game theory textbooks introduce non-cooperative and cooperative games. When teaching this content, I have noticed an interesting phenomenon. I observed that non-cooperative games are introduced syntactically, with components like the set of possible actions, the -tuple of actions in a situation, and Nash equilibrium, all being syntactic elements. On the other hand, cooperative games are introduced semantically; concepts like possible agreements, value, and the Nash solution are semantic components. This distinctive "two-legged" structure, with one leg standing on the syntactic territory of non-cooperative games and the other on the semantic territory of cooperative games, allows the game theory framework to "stand upright." This phenomenon is ubiquitous in real life and even in international relations, with significant psychological implications. Imagine people in a conflict or fight threatening, "If you do this, I’ll do that." One country tells another, "If you continue doing this, I’ll sanction you." The other country retaliates, "If you sanction me, I’ll bomb a third country." This is the language of non-cooperative game theory. When one side starts naming prices and negotiating conditions, mentioning values, they begin signaling an intention to cooperate. Hence, the way textbooks introduce these concepts is not a coincidence or oversight but likely reflects the authors’ psychological understanding of the game theory framework.

5. Set Theory Generating Two-Legged Structure and Its Applications

Set theory is the universal language of contemporary mathematics. The Bourbaki group, representing structuralist mathematics, made significant contributions to this. Recently, the author has proposed a method for generating a two-legged structure directly from set theory. Consider a set

and its power set

, which is the set of all subsets of

. Let

be an arbitrary element of

, denoted

, where

represents the membership relation. Also, let

be an arbitrary subset of

, denoted

, where

represents the subset relation. Clearly,

. The definition of the power set is given by:

meaning

if and only if

. In terms of logic,

is called the

extension of

, and

is called the

intension of

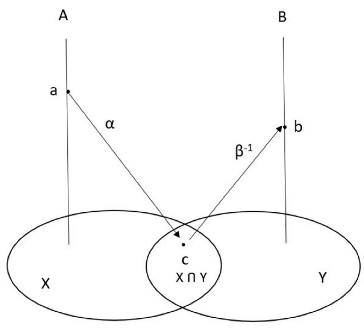

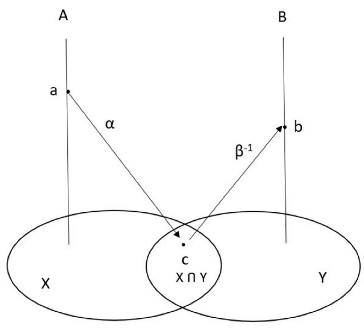

. Thus, through the linguistic analysis of power sets, we have constructed the extension syntax and its intension semantics for set theory language, also known as "membership syntax" and "inclusion semantics," respectively denoted as

syntax and

semantics. This is a two-legged structure self-generated by the intrinsic structure of set theory language and hence has generality. The meta-property of this generated two-legged structure is self-evident, being both complete and coherent, as every member of the power set uniquely denotes a subset of the set. Professor Hongbin Wang of Texas A & M University once reminded me (personal communication) that, for a category, the set of all denotations is called the index set in category theory.

The two-legged structure of set theory is foundational and has strong descriptive power in empirical scientific statistics. In empirical science, the necessity and exclusivity of statistical language arise from the assumption of the unobservability of the population. What we can observe are randomly drawn samples. The relationship between samples and populations is an inclusion relation. The relationship between samples and the power set of the population is a membership relation. The latter represents the sample syntax of statistical language, while the former represents the semantics of the sample. In traditional empirical scientific methods, the statistical significance of experiments lies in using sample means to predict population means, and the two-legged structure of sample language precisely characterizes this systemic feature.

The idea of the set theoretic two-legged structure was inspired by Professor Hong Qian of the University of Washington (Seattle, personal communication). Briefly, in thermodynamic statistical methods, the assumption is that the data population is infinite. Individual events have no independent statistical meaning because individual independent events lack measure. However, a data sample is measurable, and thus, within the power set of the population, i.e., within the sample set, a measurable density function can be formed, and its probability distribution can be found. This two-legged structure is called the measure semantics of sample syntax.

6. Two-Legged Structure in Theoretical Physics

The previously introduced language structures with two legs are attached to formal or analytical sciences. This section will introduce three types of two-legged structures in the local languages of quantum physics. The first two are relatively well-established, and detailed discussions can be found elsewhere; here, the discussion will be brief. The third one is a topic still under research and may not be fully developed, so it requires a more extensive explanation.

6.1. The Two-Legged Structure of the Wave Function

Classical quantum mechanics has three equivalent formulations. The first is Heisenberg’s matrix mechanics, which uses non-commutative relations and the uncertainty principle as its primary language. The second is Schrödinger’s wave mechanics, which uses the Hamiltonian equation of the wave function as its primary language. The third formulation, considered the most general, is Dirac’s bra-ket notation, where "bra" denotes the left bracket and "ket" denotes the right bracket. Dirac famously stated: "The higher the disturbance in the measurement, the smaller the world we can observe." In this sense, quantum mechanics is a theory about microscopic observations. Dirac’s formalism captures this essence, denoted as . For example, in standardized education testing, a student’s ability is a phenomenon difficult to observe directly, so an exam is given, with questions as stimuli and answers as responses. Thus, the variable becomes a function of the variable , denoted as , which is the wave function. The Dirac notation represents the syntax of the wave function language.

The wave function has a probabilistic interpretation from the Copenhagen school. This is called amplitude semantics (also known as complex number semantics). Any two values of the wave function can be expressed as a complex number representing a possibility. The square of the modulus of this complex number is called the amplitude of the wave function, which is its probability. In Dirac’s words, "the square of the possibility is equal to the probability." This probabilistic interpretation highlights the meaning of the wave function, known as the amplitude semantics of the wave function. We see that the Dirac syntax of the wave function and the Copenhagen amplitude semantics together constitute the two-legged structure of the wave function language.

6.2. The Two-Legged Structure of Gauge Transformation Language

In the language of gauge field theory, the wave function is placed within a two-layer, two-level grid structure. The two layers refer to the global and local levels, and the two levels at each layer include gauge potentials and gauge fields. To derive the gauge fields from the gauge potentials, appropriate differential operators must be applied to the wave function. The wave function changes as the gauge potential transforms from one state to another, multiplied by a transformation factor , i.e., . Correspondingly, under the action of differential operators, the gauge fields also transform as .

At the global level, such transformations are called first-class gauge transformations, where the transformation factor is a constant. At the local level, the transformation factor becomes a function , and the corresponding gauge transformation is called a second-class gauge transformation. Combining these two types of gauge transformations forms the syntax structure and grammatical rules of gauge transformation language.

The significance of gauge transformations lies in the concept of gauge invariance. Gauge invariance means maintaining the uniqueness and conformal properties of the transformation factors. The conformal property requires that in gauge potential transformations, the transformation factor is prefixed to the wave function state, and thus in the corresponding gauge field transformation, the transformation factor must also be prefixed to the wave function’s derivative. The uniqueness property requires that no redundant terms should appear in gauge field transformations. These two requirements are straightforward at the global level in first-class gauge transformations since the transformation factor is a constant. However, at the local level in second-class gauge transformations, redundant terms can appear because the transformation factor is a function. To eliminate these redundant terms, covariant derivatives and gauge fields are introduced as semantic techniques. Therefore, the semantics of gauge transformations is called gauge invariance semantics. The syntax structure of gauge transformations and its gauge invariance semantics together constitute the two-legged structure of gauge transformation language.

A fundamental property of gauge transformations, known as the gauge principle, states that if first-class gauge transformations are not valid, then second-class gauge transformations cannot be valid either. In other words, although the former is simpler than the latter, the former is a necessary condition for the latter.

6.3. The Two-Legged Structure of Phase Language

The contemporary Standard Model of particle physics consists of several dynamical systems, including quantum electrodynamics, quantum chromodynamics, isospin dynamics, electroweak dynamics, and the Higgs mechanism, all described by the language of gauge field theory. Dynamical analysis is source analysis, where the sources are various charges, such as the electric charge carried by electrons and the color charge and fractional electric charge carried by quarks, among others. Particles’ charges are assigned internal spaces, and the number of possible charges generally corresponds to the dimension of the internal space. For example, an electron carries only electric charge, so its internal space is one-dimensional; conversely, quarks can carry three types of color charge, making their internal space three-dimensional. When a particle transitions from one state to another, its internal space undergoes rotation, and this rotation changes the phase, known as the dynamical phase. The rate of change in the phase, referred to as momentum, is the origin of the concept of spin. In quantum mechanics, spin is an intrinsic property of particles, with no equivalent in Newtonian mechanics, which does not assume internal space for particles.

In quantum field theory, particles are characterized by their wave functions, making phase language naturally the "mother tongue" of wave functions. As discussed in

Section 6.2, in gauge field theory language, the wave function is placed within a given two-layer, two-level grid framework. Due to the action of differential operators, two types of gauge transformations are performed to ensure that the wave function remains invariant under these transformations. The purpose of invariance is to achieve gauge symmetry, which is described by symmetry groups. Symmetry groups are algebraic structures, so in this sense, the syntax structure of phase language is algebraic, referred to as the algebraic syntax of phase language.

To ensure the invariance of second-class gauge transformations, covariant derivatives and gauge fields must be introduced, expressed as follows:

Here, we see that the covariant derivative includes the gauge field, and the difference in gauge fields between two states corresponds exactly to the differential of the dynamical phase function. In other words, the integral of the gauge field represents a phase known as the Berry phase. Yang and Mills refer to this as a non-integrable phase factor. If the dynamical phase of the wave function is the internal space phase, then the Berry phase is the external phase. In fiber bundle theory, the Berry phase represents the trajectory of a particle on the base manifold. In social science terms, the dynamical phase characterizes changes in individual mental activities and behaviors, while the Berry phase characterizes the impact one has in society. The Berry phase is a type of geometric phase. Gauge fields are used to balance changes in the dynamical phase, and the Berry phase along with Yang and Mills’ theory of non-integrable phase factors are important aspects of the geometric formulation in particle physics. Thus, the phase language’s two-legged structure consists of its algebraic syntax and its geometric semantics.

Part II. Wittgenstein and Gödel: Debate and Turning Point

There was debate between Wittgenstein and Gödel. In the framework of modern gauge theoretic structure, this controversy can be well-formulated as a unified account. In the following, we introduce Gödel’s incompleteness theorem, Tarski’s indefinability theorem, and Wittgenstein’s principles of incomplete rules of language game. Briefly speaking, these three topics cover the contents of three categories of linguistics: the syntax, the semantics, and pragmatics.

7. Gödel and The Realm of Language

In 1900, Hilbert presented 23 unsolved mathematical conjectures at the International Congress of Mathematicians, including the Riemann Hypothesis and the Continuum Hypothesis, collectively known as Hilbert’s Program. One of these puzzles concerned the logical foundations of the edifice of mathematics, specifically the question of consistency. In 1931, Austrian mathematician and logician Kurt Gödel provided a negative result, proving the incompleteness of first-order theories, now known as Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem, or simply Gödel’s Theorem.

Gödel’s theorem has widespread applications. For example, the "Halting Problem" in computer science is a version of it. Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem is one of the most well-known names in mathematical theorems and is widely discussed in various books. While the theorem is an intellectually rich and fascinating story, its content is simpler compared to other famous mathematical theorems and proofs. This section does not assume any prior knowledge. We will explore the profound ideas and exceptional wisdom contained in Gödel’s theorem and Tarski’s theorem through the introduction of their concepts, function construction, and proof techniques.

In this discussion, we will occasionally use a classical style, intentionally incorporating a certain literary touch to enhance cognitive engagement. The acquisition of knowledge involves more than just understanding—it also entails attention, memory, appreciation, and experience. Therefore, both teaching and learning must be appropriately paced. The Platonic tradition in epistemology emphasizes the three elements of truth, belief, and justification. Cognitive mechanics tells us that, for most learners, it is difficult to advance all three elements simultaneously; instead, they must proceed in a cyclical and iterative manner. Gödel’s and Tarski’s theorems are not only fascinating but also profound, making them valuable for personal intellectual development. Below are eight steps to understanding Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem.

7.1. First-Order Theory

Discussing Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem, it is not entirely accurate to say that no prior knowledge is needed. The one prerequisite is first-order logic. A logic system is a formal system, and mathematical logic is a formalization and logical treatment of mathematical language. For example, in mathematical language, we say, "For all ," which in formal logic is expressed as . The symbol is called a universal quantifier. represents a predicate structure, where is a predicate and is an individual variable. When the quantifier is restricted to quantifying individual variables, the logic is first-order. When the quantifier is allowed to quantify predicates, the logic is second-order. Second-order logic is equivalent to set theory, and with the addition of the axiom of choice and the continuum hypothesis, it can account for the entire edifice of mathematics. Note that first-order logic is complete—this was proven by Gödel in 1930, known as Gödel’s Completeness Theorem. Thus, Gödel was first and foremost a logician. It is important to be careful not to confuse this result with Gödel’s 1931 Incompleteness Theorem.

Logic includes logical connectives such as conjunction, disjunction, implication, and negation, which are also called logical operators. In mathematics, there are mathematical operations such as addition and multiplication. Logical operators and mathematical operations differ fundamentally, as shown in the following simple comparison. First, consider logical operators. Disjunction, or not , is a tautology, always true, and can be used to define the identity element 1 in Boolean algebra. Expressed formally, . For convenience, the equals sign here can denote either equality or equivalence. Conjunction, and not , is a contradiction, always false, and can be used to define the identity element 0 in Boolean algebra. Formally, . Now consider mathematical operations. Addition: . Multiplication: . It is clear that disjunction and addition, conjunction and multiplication cannot be functionally interchanged, because the resulting identity elements differ. Furthermore, disjunction and multiplication, conjunction and addition cannot functionally replace each other. For example, true or is still true, whereas 1 times equals . Similarly, false and is still false, whereas 0 plus equals . The reason lies in the essential difference between the identity elements in logic and those in mathematics. This fundamental distinction separates logic and mathematics, creating a significant divide between them. In the fourth step discussed later, we will see how Gödel’s "arithmetization" bridges this divide, enabling smooth passage between them.

When two mathematical operations (addition and multiplication) are added to the first-order logic described earlier and formalized as a new formal system, it becomes what is known as "first-order theory." The prototypical example is Peano Arithmetic, an axiomatic system. Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem characterizes two metamathematical properties of first-order theory, specifically its system properties. It is also worth noting that first-order theory is a very basic yet special level of mathematics, and Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem shows that at this level, our axiomatization methods are limited. Looking downward, first-order logic does not require stronger axiomatization methods; looking upward, more complex number fields, such as the real or complex numbers, allow for richer axiomatization methods, whose completeness theorem was later proven by Tarski.

Additionally, it is helpful for the reader to distinguish between three domains of discourse, which will aid in navigating this section. One is ordinary naïve arithmetic, where for an -ary relation, one can only speak in terms of whether it "holds." Another is the defined arithmetic structure, represented as a semantic model in first-order theory, where for an -ary function or formula, one can only speak in terms of whether it is "true." The final domain is the syntactic formal system of first-order theory, denoted as , where for a function or formula, one can only speak in terms of whether it is "provable." These three domains share a common origin in the natural numbers but are distinct from one another. The concept of expressibility used in Gödel’s theorem concerns the relationship between ordinary naïve arithmetic and the syntactic formal system of first-order theory. The concept of arithmetical definability used in Tarski’s theorem concerns the relationship between ordinary naïve arithmetic and the semantic model of first-order theory. Finally, Gödel’s and Tarski’s theorems themselves concern the relationship between the semantic model and the syntactic formal system of first-order theory.

7.2. Natural Numbers and Enumerers

The set of natural numbers is countably infinite: 0, 1, 2, 3, …, continuing indefinitely. This is well known, and in the literature, they are referred to as intuitive natural numbers. While number theorists regard natural numbers as familiar and fundamental, in other branches of mathematics, they are often seen as mere tools, akin to Cinderella serving others. Their primary role is to act as subscripts, superscripts, indices, explicit and implicit notations, as well as adhering to Einstein’s convention of upper and lower indices. In tensor transformations, due to the frequent appearance and manipulation of indices, natural numbers have often been a source of frustration for scholars. Although these "Cinderellas" seem content with their supporting roles, real and complex numbers may appear more glamorous, possessing a vast array of fields, continuous ecologies, rippling limits, and differentiability at every point. Nonetheless, one might argue that the variables moving across these fields still need to be countable, which ensures that natural numbers always have a place, however humble, to contribute their work as indices. It appears to be a situation of resigned acceptance.

However, Gödel had an extraordinary insight—he realized that natural numbers, far from being mere servants, were more akin to a hidden master, like the humble monk sweeping the floors in a Shaolin temple, secretly possessing great martial prowess. In subsections 7.4 and 7.5, Gödel’s method of arithmetization will be shown to encapsulate all proofs in a sweeping motion, and a self-referential statement will dramatically transform the very nature of formulas inside and outside the system. One is left speechless at the brilliance of this masterstroke.

In modern mathematics, natural numbers are no longer taken for granted—they must be defined and constructed. These constructed natural numbers are defined as ordinals. The construction process begins with the empty set , from which subsequent numbers are inductively defined by a successor function. The empty set, containing no elements, is defined as the first ordinal, 0. The next ordinal is the set containing only the empty set, , defined as the second ordinal, 1. Continuing this process, each subsequent ordinal is defined as a set containing all previously defined ordinals as its elements, denoted by . This method of construction is called the successor function.

At first glance, the difference between intuitive natural numbers and ordinals seems to be nothing more than a redefinition of natural numbers using the language of set theory. One might dismiss this as a mere display of trivial skills, no more than elementary techniques. But Gödel, with his ability to discern the subtle from the imperceptible, was able to extract the concept of the expressibility from this foundation.

7.3. Expressibility

Expressibility establishes a connection between arithmetic relations and provability within first-order theories. In this context, an -ary relation in arithmetic corresponds to an -ary function in a first-order theory. To ask whether natural numbers satisfy the relation is equivalent to asking whether substituting the corresponding ordinals into the function results in a provable statement within the first-order theory .

Expressibility conveys two essential propositions. First, if holds true, then is provable in . Second, if is false, then is provable in , where denotes the negation operator.

In these two conditions of expressibility, the law of excluded middle is applied crosswise. Each proposition leads directly from one to the other, and the relationship between the two creates a sharp logical dichotomy, evoking a sense of the cold and unyielding nature of logical abstraction, where precision leaves little room for nuance. This may induce in the reader a powerful sense of logic’s conceptual reach, and of its unforgiving methods, eliciting feelings both of admiration and frustration. As Karl Popper’s philosophy of science teaches, any form of scientific abstraction comes with boundaries—what is gained in clarity often comes at the cost of something else. In mathematics, this is referred to as simplification: to establish two distinct dimensions, one must sacrifice certain entanglements, allowing the two to become orthogonal.

The second proposition of the expressibility, particularly, which forces a transition from the falsity of to the provability of in , is a strong condition that may even conflict with intuition. Whether examined through the lens of the competing mental logic theory or the mental models theory in the psychology of reasoning, this transition is handled differently by each. The expressibility represents a historical shift from naive arithmetic to syntactic formalization, embodying both the tragic grandeur of a Dunkirk-like retreat and the noble promise of humanity’s intellectual responsibility, reminiscent of the Normandy landing.

In the above discussion, we used the phrase "if the relation is true" as a semantic convenience for continuity. However, as we proceed to Tarski’s indefinability theorem, we will see the profound impact that the concept of "predicate truth" can have.

7.4. Gödel Numbering

This is the pinnacle of human intellect in the 20th century, the unrivaled summit of mathematical beauty. Comparable to Einstein’s principle of equivalence in general relativity, Gödel’s numbering method may be different in form but matches it in brilliance, excelling through its rigorous precision. No wonder Einstein once remarked that his daily walk to work at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton was merely an excuse to stroll with Gödel. Gödel’s numbering method can be explained in three steps.

Step 1: Each symbol can be mechanically assigned a unique odd number. In a formal system, such as first-order logic or first-order theory, the formal language may have infinitely many symbols, but they are always countable. Thus, it is always possible to arrange some mechanical procedure to assign each symbol a unique odd number, called the Gödel number of that symbol.

Step 2. Every formula is a finite sequence of symbols, and each formula can be mechanically assigned a unique composite number, its Gödel number. The generation of this Gödel number is profoundly sacred; with reverence, it is written as follows:

On the left-hand side of the equation, represents the Gödel number of the formula. On the right-hand side is a product of exponents, where the base of the -th exponent is the -th prime number, and the exponent is the Gödel number of the -th symbol in the formula .

Step 3. Each proof is an ordered sequence of a finite set of formulas. Each proof can be mechanically assigned a unique composite number, its Gödel number. The generation of this Gödel number is even more sacred; with continued reverence, it is written as follows:

On the left-hand side of the equation, represents the Gödel number of a proof, which is also a composite number; is short for “proof” in German. On the right-hand side is another finite product of exponents, where the base of the -th exponent is the -th prime number, and the exponent is the Gödel number of the -th formula in the proof sequence.

This is Gödel’s numbering method. Its magic lies in the reverse process: starting from the Gödel number of a proof, i.e., a composite number, using the uniqueness of prime factorization, one can recover the unique sequence of exponents that generated this Gödel number. Similarly, from the Gödel numbers of the formulas in the sequence, one can recover the sequences of symbols corresponding to each formula. Ultimately, this allows us to restore the sequence of formulas representing a proof. This enables a bidirectional conversion between a first-order theory and its arithmetic model.

7.5. Self-referential Sentences

One of the ingenious uses of Gödel’s numbering method is to generate self-referential sentences. Suppose is a formula with only one free variable, and let its Gödel number be . Substituting this Gödel number into gives a closed formula . The formula is a self-referential sentence since it contains the Gödel number of its parent formula. If is provable, it should have a proof, denoted as , which also has its own Gödel number.

We can now introduce a binary arithmetic relation , where is the Gödel number of a parent formula , which has one free variable, and is the Gödel number of the proof of its self-referential sentence , i.e., . As long as and satisfy the above conditions, holds, and by the definition of expressibility, is provable in the so called first-order theory .

This seems like constructive progress, quite positive. But who could have imagined that Gödel, while seemingly building in plain sight, was covertly undermining the foundations? By placing a negation operator in front of

, the situation changes drastically, and offense turns to defense. The result is like turning one of the 23 pearls of wisdom on Hilbert’s chain backward, leaving us with endless philosophical reflection and ontological inquiry, like the broken beauty of the Venus de Milo. The formula Gödel ingeniously constructed says: For all

,

does not hold. Formally, it is written as:

Recalling the definition of the function

, this formula clearly tells us that no

can be the Gödel number of any proof. Now, let the Gödel number of the formula

be

. This allows us to construct the self-referential sentence:

This formula is the main character of Gödel’s theorem. It gracefully embodies both the self-reference of its parent formula and the negation of the function , without any sense of contradiction. The only thing it leaves ambiguous is whether it itself can be proven. Gödel’s incompleteness theorem and its proof are built around the question of proving the identity of this self-referential sentence .

Gödel’s numbering method and the construction of self-referential sentences also evoke a deeper sense of aesthetics, blending the ancient mathematical traditions of East and West. Western mathematical culture, tracing back to Euclid’s Elements, emphasizes generalization and analysis. In contrast, ancient Eastern mathematical culture focused on examples—not ordinary examples, but exemplars of general principles, such as those found in China’s Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art, or the works of (modern) India’s Ramanujan. The late logician Youding Shen once explained this principle to me. He had a Ph.D. student who worked on the history of ancient Chinese logic, and his dissertation was on this very subject. Shen also wrote a book on the logical thought of the Mohists. A mathematical proof becoming a Gödel number exemplifies this principle to the extreme.

7.6. Consistency and -Consistency

After much groundwork and preparation, we are now nearing the main topic. We say that a formal system is syntactically consistent (also called simply consistent) if, for any given formula, either the formula is provable, or its negation is provable. This exhausts all possibilities and covers all cases. The proof of Gödel’s theorem also relies on an indispensable concept, namely, -consistency. It states that, given any formula with one free variable, if is provable for every , then is unprovable. There is a lemma that will be used later: -consistency implies consistency.

7.7. Gödel’s Independence Theorem

Statement 1: If is consistent, then is unprovable. Using proof by contradiction, assume is provable, then there exists a proof , and the Gödel number of this proof satisfies . By expressibility, is provable; however, by the construction of , holds for all , which is a contradiction. This contradiction disproves the assumption, so is unprovable.

Statement 2. If is -consistent, then is unprovable. Again, using proof by contradiction, assume is provable. Then, by the lemma, is consistent, so the assumption leads to being unprovable. This means that no proof of exists, and therefore no Gödel number of such a proof exists. Consequently, for any , the relation does not hold. Conversely, for any , the relation holds, which matches the formula . Hence, by the definition of -consistency, becomes provable. We previously deduced that is unprovable, but now we are claiming is provable. This contradiction disproves the assumption, proving that is unprovable.

From the proofs of Statements 1 and 2, we conclude that the sentence is indeed neither provable nor refutable within the first-order theory . We say that it is independent of the first-order theory. This result is known as Gödel’s Independence Theorem, or Gödel’s First Theorem. It is a general result; if one tries to add as an axiom to the first-order theory , new independent sentences can continue to be constructed.

7.8. Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem

Reflecting on this, the construction of the sentence asserts its own unprovability. We have now proven that is indeed unprovable, so is true. Hence, is true but unprovable, which implies that the first-order theory is incomplete. This is the famous Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem. Finally, let us not forget to define completeness: A first-order theory is complete if, for any sentence in , if is valid, then is provable.

Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem, stemming from Hilbert’s grand project, ultimately reached an unforeseen conclusion. Earlier, for convenience, we mentioned the phrase “a relation is true” and also said, “ is true.” But what does “true” really mean? This question belongs to the realm of philosophical inquiry known as the theory of truth. Next, we will discuss Tarski’s indefinability Theorem, which is a companion to Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem.

8. Tarski: Levels of Language

According to contemporary formal science, a formal system—such as a logical system—consists of two standard components: its syntax and its semantics. This reflects the nature of formal languages. In the formal syntax of the system, the focus is on provability, while in its semantics, the focus is on truth values, which can only be true or false. This is a binary situation, hence the term propositional attitudes. The semantics of a first-order theory, also known as its model, is an arithmetic structure. Syntax and semantics should have equal status, meaning that there should be an if-and-only-if relationship between provability and validity. This is a requirement from metalogic regarding the overall properties of the system. Any provable formula should be valid, a property called soundness, and any valid formula should be provable, known as completeness. We desire that the syntax and semantics of a system are of equal strength. If syntax is stronger than semantics, this is known as under formalization or over-modeling; if syntax is weaker, this is called over formalization or under modeling. In decision theory, incompleteness is also referred to as corresponding irrationality, while unsoundness is known as reflective irrationality. Below are four steps to understanding Tarski’s theorem.

8.1. Arithmetic Definability

In

Section 7.3, we introduced Gödel’s notion of expressibility, which establishes the connection between relations in naive arithmetic and provability in first-order syntactic theories. Tarski introduced the concept of arithmetic definability, which describes the relationship between relations in naive arithmetic and the semantics of first-order theories (i.e., the given arithmetic structure that serves as the model). It states that if an n-ary relation holds in naive arithmetic, then the corresponding function is declared true in the model of the first-order theory. Consequently, the relation

is said to be arithmetically definable in the model.

Consider a formula with one free variable, known as the base formula, whose Gödel number is . Substituting for results in a new formula , which is a closed expression (i.e., without free variables) and a self-referential statement of . We can further denote as the Gödel number of . Strictly speaking, Tarski’s theorem, compared to Gödel’s theorem, presents a conceptual difficulty. Gödel’s theorem involves two Gödel numbers: one for the base formula and another for the proof of its self-referential statement, and these two tasks are easily distinguishable without cognitive hindrances. However, Tarski’s theorem also involves two Gödel numbers: one for the base formula and another for its self-referential statement. Conceptually, this is more tangled and demands greater cognitive effort to avoid memory blocks. I have observed this problem in my lectures. Therefore, for ease of distinction, we refer to the Gödel number of a base formula as the first-order Gödel number, while the Gödel number of the self-referential statement generated from the base formula and its Gödel number is called the second-order Gödel number.

By constructing second-order Gödel numbers, Tarski maximized the potential of Gödel’s numbering method. His motivation was to introduce a natural number relation denoted by , where is the first-order Gödel number of the base formula, and is the second-order Gödel number of its self-referential statement. Furthermore, from , one can arithmetically define a function in the first-order theory and its model, which can also be said to be arithmetically defined by the former. This effort demonstrates a dual self-reference and clearly serves future purposes. It is important to point out that is a general binary relation that holds for any formula with one free variable, and thus is also a general binary predicate function.

Tarski was evidently influenced by Gödel’s work, as his use of Gödel’s numbering method attests. However, genius is genius. Gödel was a genius, a master of syntax, and Tarski was also a genius, a master of semantics. Both had a profound academic passion for the foundations of mathematical logic and the mission to communicate with the mysteries of the universe. They possessed the talent to cut through mountains and build bridges across rivers.

8.2. The Truth Predicate and Semantic Models

Truth, in mathematical logic, is essentially a semantic concept and only makes sense within models. One day, Tarski, the master of semantics, had a genius idea: what if one treated the propositional attitude "truth" syntactically? How would that feel? Hence, Tarski added a truth predicate to the formal language of the first-order theory. As a result, we obtain a hypothetical first-order theory with a truth predicate, denoted as . This single flash of insight stirred great waves.

Notice that with the truth predicate , one can construct sentences involving . Simultaneously, one must extend the original model to accommodate these new truth-predicate sentences. The truth predicate is a unary predicate. In English, the verb “to be”, followed by an adjective or noun to express a property, such as “is red,” “is round,” or “is plastic.” In this way, creating a property like “is true” seems unproblematic.

For convenience, let us introduce three notations. First, let us denote the closed expression

from

Section 8.1 as

. Second, since we have now introduced a truth predicate into the syntax, there should logically be truth sentences in the model, denoted by

. Finally, this sentence

should have a Gödel number, denoted as

. Thus, if

is an arithmetic model of the truth predicate, the condition

belongs to the extension of

holds if and only if

is interpreted as true under the intension of

. The model of the truth predicate is clearly and simply expressed by the definition of a set:

Thus, the extension of is a set of Gödel numbers, and the intension of states that each of them corresponds to and only to the Gödel number of a formula interpreted as true in the model.

8.3. The Liar Paradox

It is often mistakenly believed that Gödel’s incompleteness theorem is a paradox, but it is not. Tarski’s theorem, however, is indeed a formalized version of the so-called "Liar Paradox." The Liar Paradox arises from the sentence: "This statement is false." Upon reflection, if this sentence is true, it implies that it is false; if it is false, it implies that it is true. This is what we call the Liar Paradox. Tarski ingeniously embedded the Liar Paradox within first-order theory by carefully constructing the following sentence: "For all

, if

, then not

." Formally, this can be written as:

This formula contains one free variable

, making it an open formula. This formula has a unique Gödel number, which we denote as

. By substituting

for the free variable

, we obtain a closed formula

, which is a self-referential statement of the form:

This formula is the centerpiece of Tarski’s theorem. It also has a unique Gödel number, denoted , which is a second-order Gödel number. Later, we will see how Tarski skillfully utilizes this formula in his proof.

8.4. Tarski’s Theorem

Tarski, full of enthusiasm, introduced the truth predicate into first-order theory—an act of extraordinary insight and courage. The result, however, was the discovery that no model could be found for this truth predicate. Some might claim that Tarski’s original intention was to produce a negative result, but this is generally a post hoc rationalization. Very few mathematicians set out with the express goal of proving a negative result. Gödel himself initially aimed to contribute to Hilbert’s program by providing a solid logical foundation for the rapidly advancing field of mathematics—a tragic yet heroic endeavor in the backdrop of mathematical beauty.

In brief, Tarski’s theorem states that within the framework of first-order theory, the truth predicate cannot have an arithmetic model. The proof proceeds by contradiction, which we will outline in three steps.

Step 1: Using proof by contradiction, we assume that there exists a model as defined earlier, .

Step 2: Since such a model exists, should be interpreted as true in , meaning that belongs to .

Step 3: Recall that

is the Gödel number of

, and hence it is the second-order Gödel number of

. From the definition of

in

Section 8.1, it follows that

, and thus the function

, is arithmetically definable. However, recalling the conditional structure of

, we can conclude

, meaning that

is not true in

, so

does not belong to

.

The contradiction between steps 2 and 3 shows that the assumption in step 1 is false. In other words, the truth predicate cannot have an arithmetic model within the framework of first-order theory, meaning that the truth predicate is not arithmetically definable. This result is known as Tarski’s indefinability theorem.