Submitted:

16 January 2025

Posted:

16 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Cultivation of Cells

2.2. EMS Treatment, Determination of Cell Survival, and Screening for Mutants

2.3. Characterization of Euglena Mutants

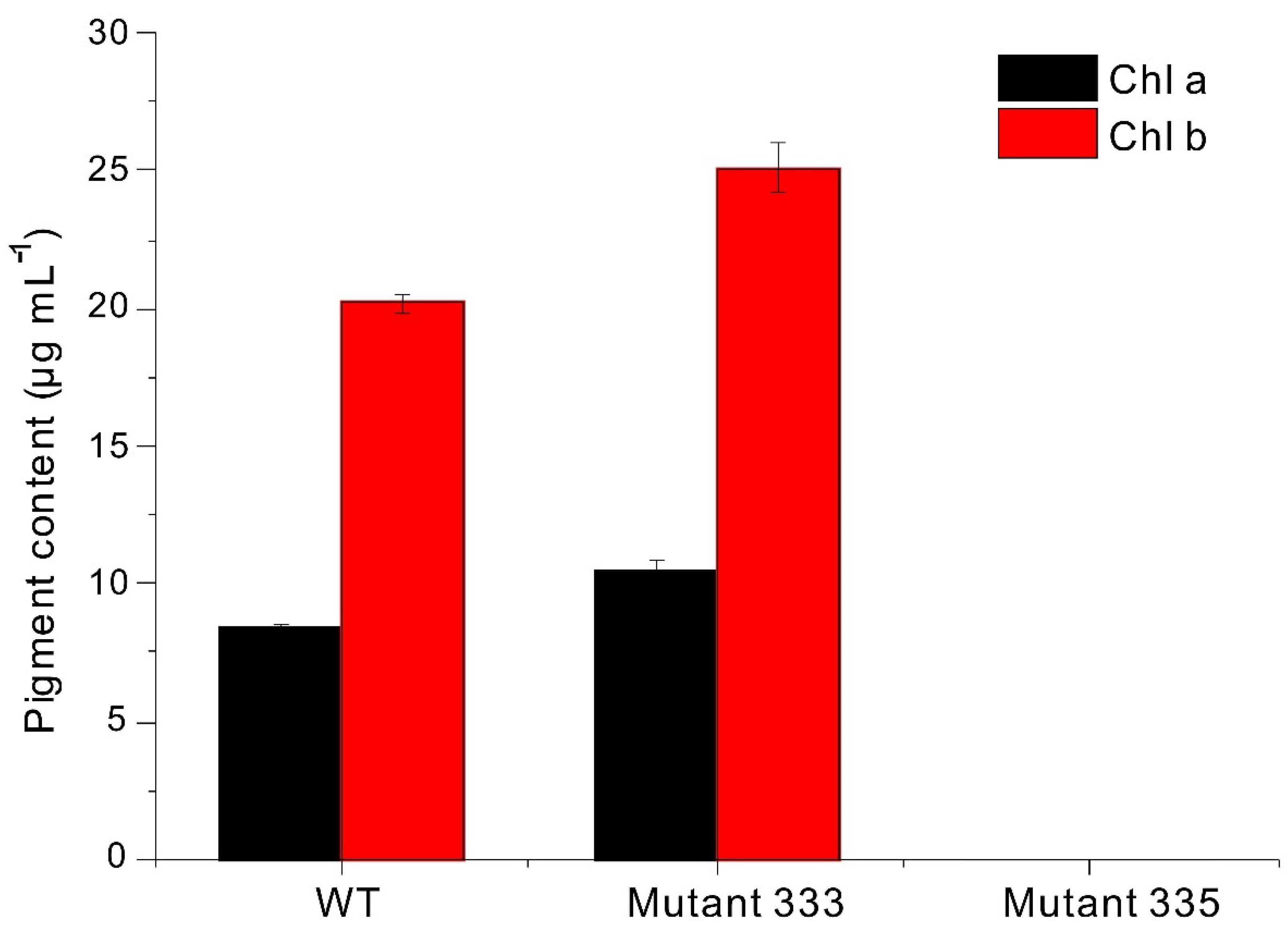

2.4. Measurement of Chlorophylls

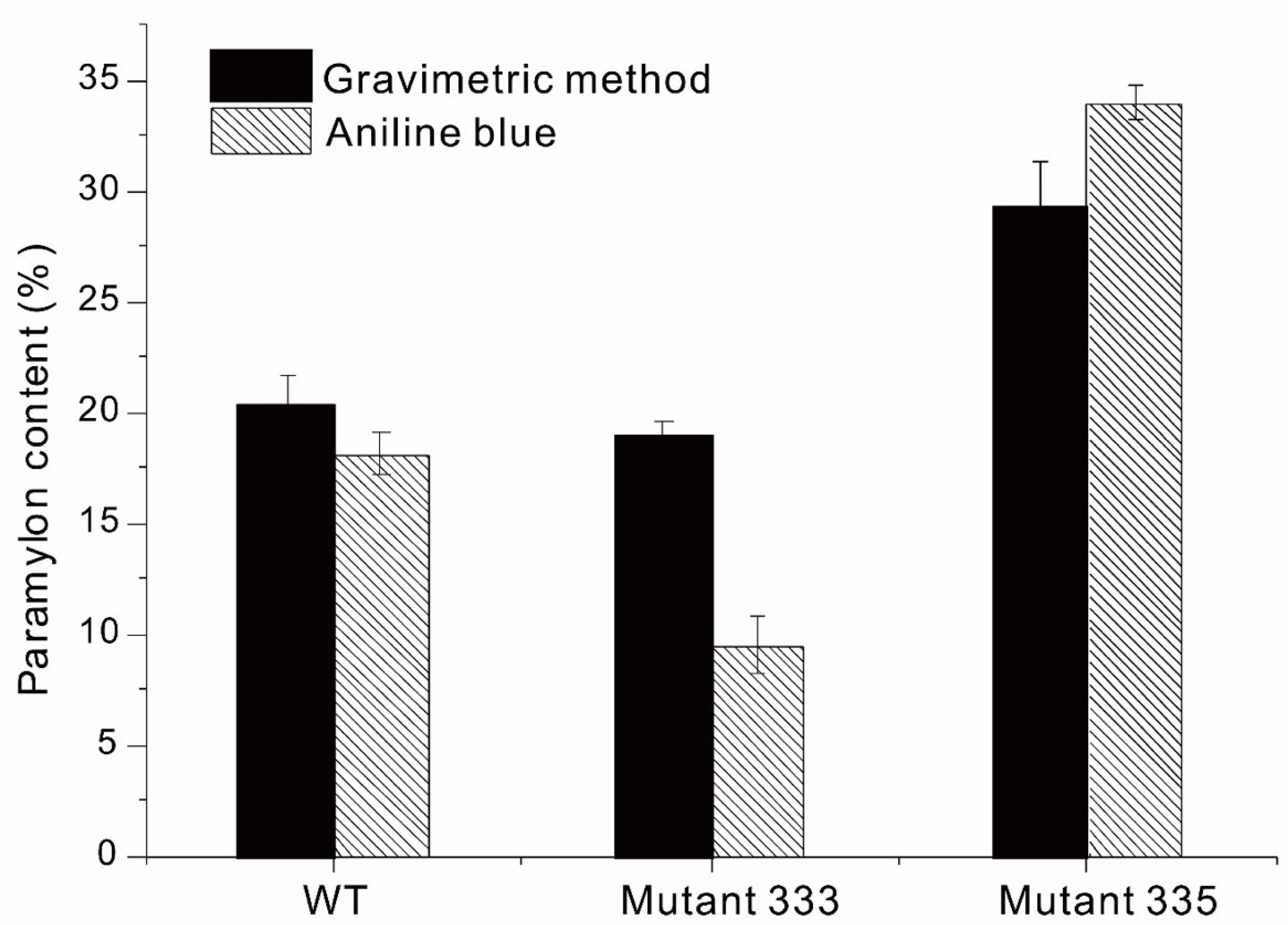

2.5. Measurement of Paramylon Using Gravimetry

2.6. Measurement of Paramylon Using Aniline Blue Staining

2.7. Analysis of Volatile Components

3. Results and Discussion

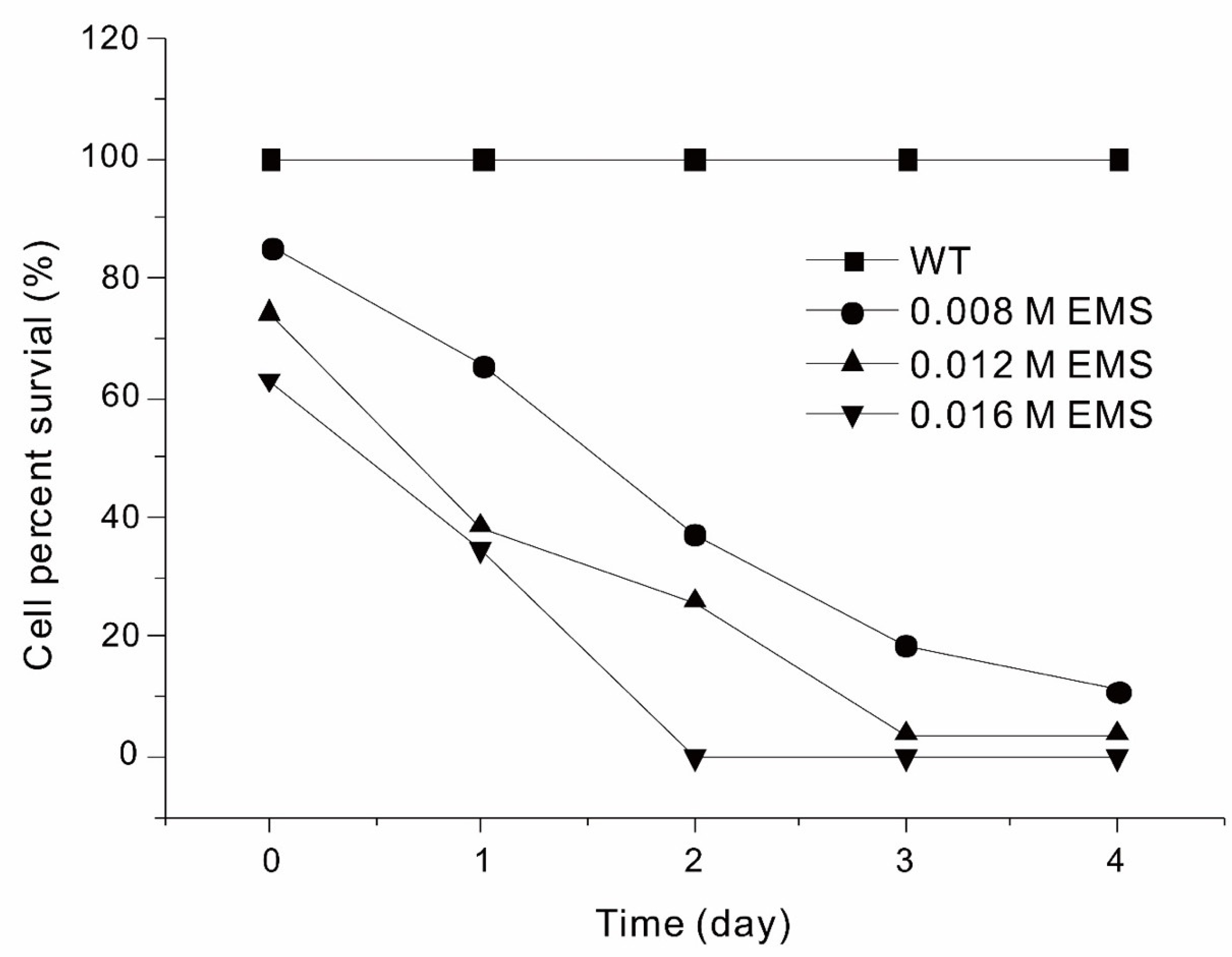

3.1. EMS Mutagenesis

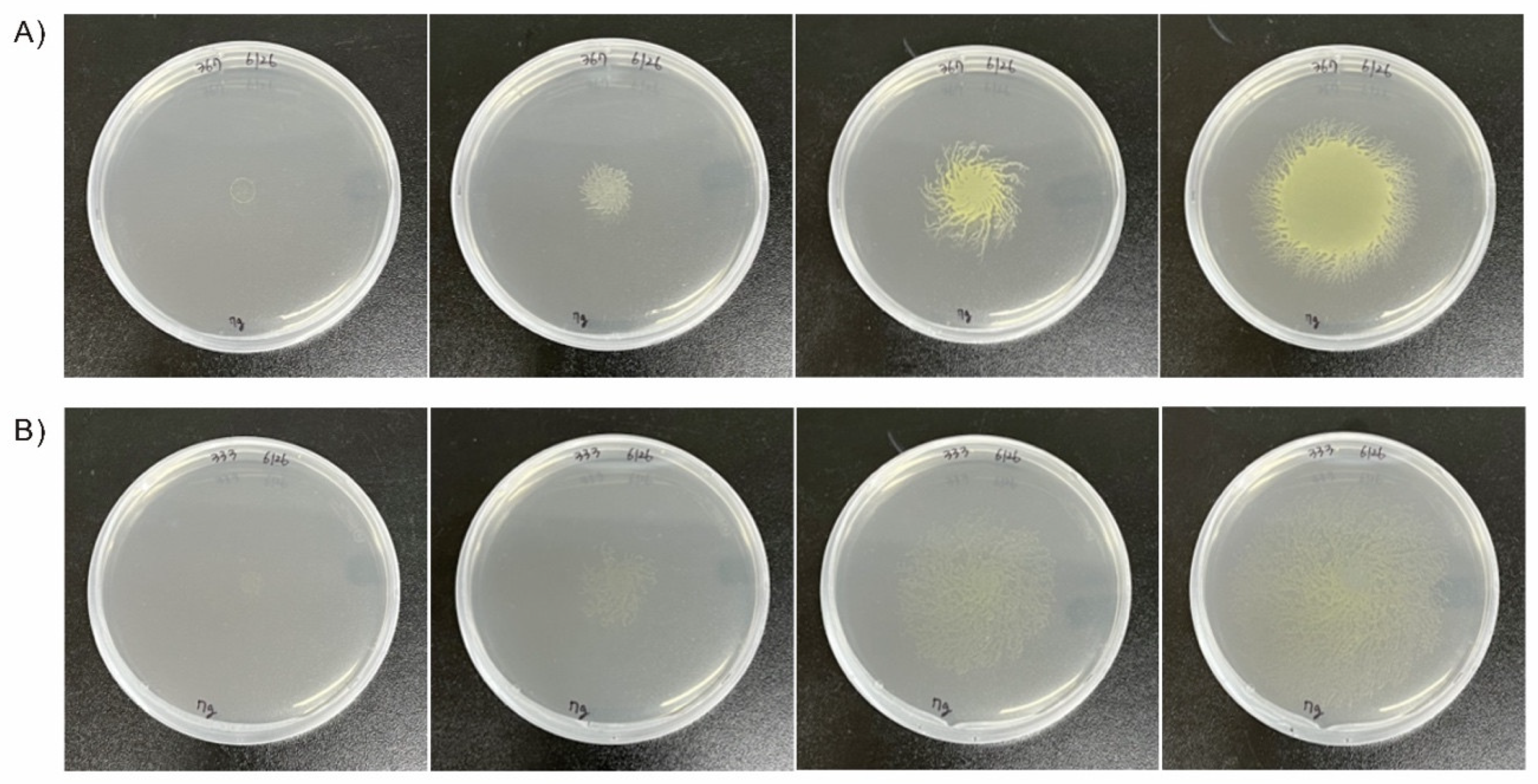

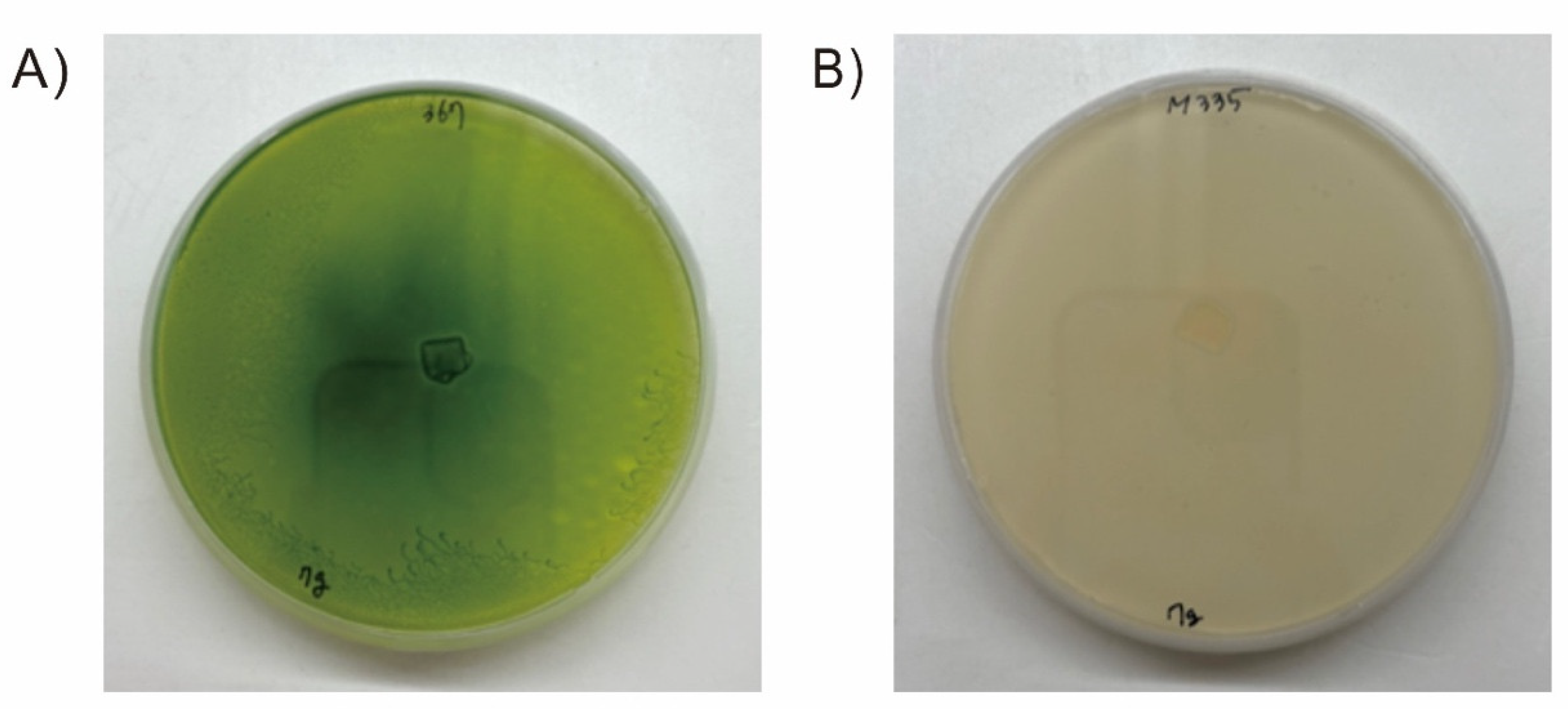

3.2. Screening EMS Mutants

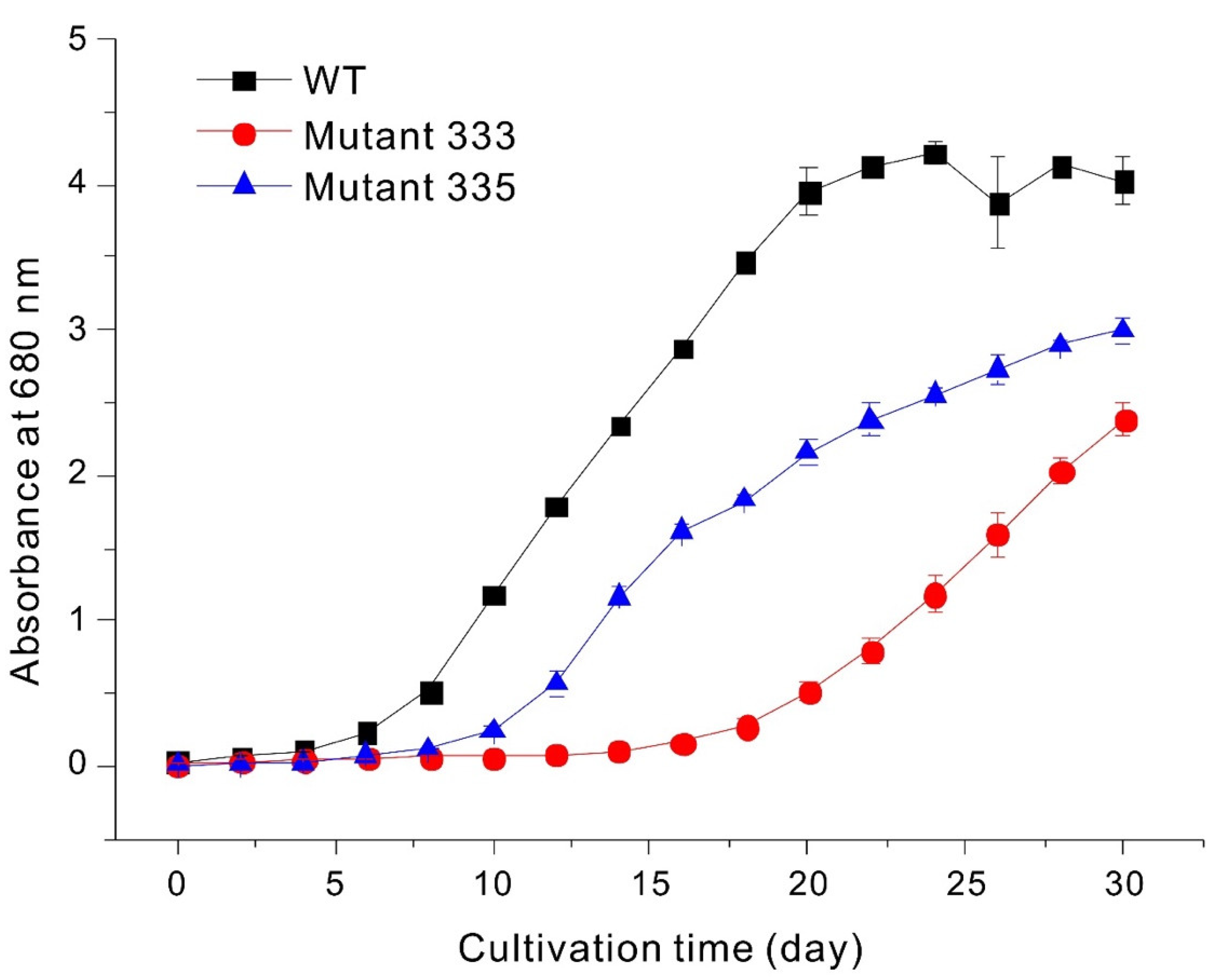

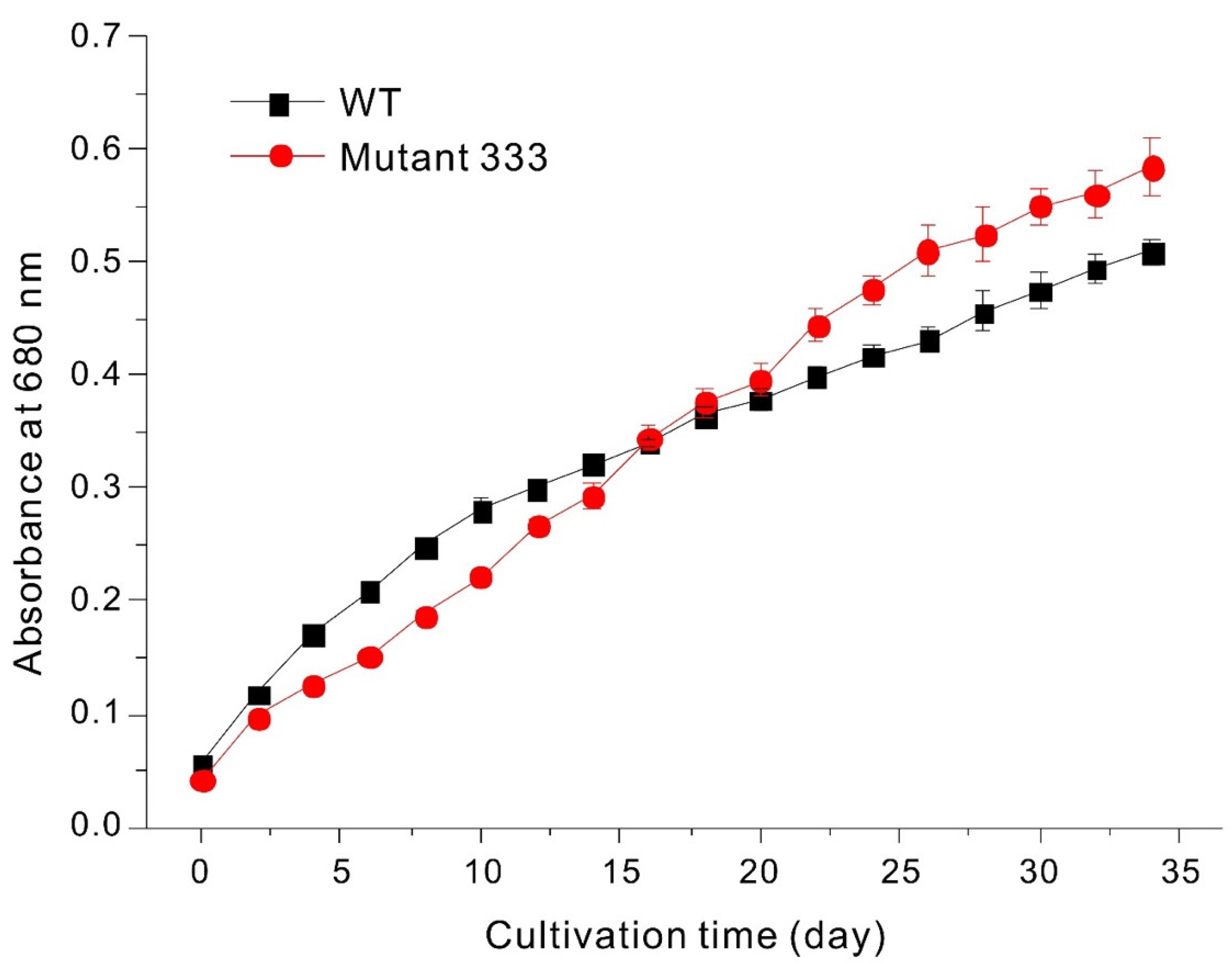

3.3. Paramylon Production

3.4. Volatile Compounds

4. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, J.; Liu, C.; Du, M.; Zhou, X.; Hu, Z.; Lei, A.; Wang, J. Metabolic responses of a model green microalga Euglena gracilis to different environmental stresses. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2021, 9, 662655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitaoka, S.; Hosotani, K. Studies on culture conditions for the determination of the nutritive value of Euglena gracilis protein and the general and amino acid compositions of the cells. 1977.

- Baker, E.R.; McLaughlin, J.J.; Hutner, S.H.; DeAngelis, B.; Feingold, S.; Frank, O.; Baker, H. Water-soluble vitamins in cells and spent culture supernatants of Poteriochromonas stipitata, Euglena gracilis, and Tetrahymena thermophila. Archives of Microbiology 1981, 129, 310–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kang, J.; Seo, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.Y.; Park, Y.; Yu, J.; Lee, T. A novel screening strategy utilizing aniline blue and calcofluor white to develop paramylon-rich mutants of Euglena gracilis. Algal Research 2024, 78, 103408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, C.; Chronopoulou, E.G.; Letsiou, S.; Maya, C.; Labrou, N.E.; Infante, C.; Power, D.M.; Manchado, M. Antioxidant capacity and immunomodulatory effects of a chrysolaminarin-enriched extract in Senegalese sole. Fish & shellfish immunology 2018, 82, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Del Cornò, M.; Gessani, S.; Conti, L. Shaping the innate immune response by dietary glucans: any role in the control of cancer? Cancers 2020, 12, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stier, H.; Ebbeskotte, V.; Gruenwald, J. Immune-modulatory effects of dietary Yeast Beta-1, 3/1, 6-D-glucan. Nutrition journal 2014, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teerawanichpan, P.; Qiu, X. Fatty acyl-CoA reductase and wax synthase from Euglena gracilis in the biosynthesis of medium-chain wax esters. Lipids 2010, 45, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakku, R.K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Inaba, Y.; Hiranuma, T.; Gianino, E.; Amarianto, L.; Mahrous, W.; Suzuki, H.; Suzuki, K. New insights into raceway cultivation of Euglena gracilis under long-term semi-continuous nitrogen starvation. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 7123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Su, Y.; Xu, M.; Bergmann, A.; Ingthorsson, S.; Rolfsson, O.; Salehi-Ashtiani, K.; Brynjolfsson, S.; Fu, W. Chemical mutagenesis and fluorescence-based high-throughput screening for enhanced accumulation of carotenoids in a model marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Marine drugs 2018, 16, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, R.; Nomura, T.; Yamada, K.; Mochida, K.; Suzuki, K. Genetic engineering strategies for Euglena gracilis and its industrial contribution to sustainable development goals: A review. frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2020, 8, 556462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, M.; Nomura, T.; Tamaki, S.; Ozasa, K.; Suzuki, T.; Toyooka, K.; Hirota, K.; Yamada, K.; Suzuki, K.; Mochida, K. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated generation of non-motile mutants to improve the harvesting efficiency of mass-cultivated Euglena gracilis. Plant biotechnology journal 2022, 20, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.D.; Sojin, K.; Santhanam, P.; Dhanalakshmi, B.; Latha, S.; Park, M.S.; Kim, M.-K. Triggering of fatty acids on Tetraselmis sp. by ethyl methanesulfonate mutagenic treatment. Bioresource Technology Reports 2018, 2, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Suzuki, H.; Takeuchi, T.; Kazama, Y.; Mitra, S.; Abe, T.; Goda, K.; Suzuki, K.; Iwata, O. Efficient selective breeding of live oil-rich Euglena gracilis with fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 26327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, S.; Yamada, K.; Takebe, H.; Kiuchi, R.; Iwashita, H.; Toyokawa, C.; Suzuki, K.; Sakurai, A.; Takaya, K. Optimal conditions of algal breeding using neutral beam and applying it to breed Euglena gracilis strains with improved lipid accumulation. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 14716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, W.-S.; Lee, B.; Jeong, B.-r.; Chang, Y.K.; Kwon, J.-H. Truncated light-harvesting chlorophyll antenna size in Chlorella vulgaris improves biomass productivity. Journal of Applied Phycology 2016, 28, 3193–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellburn, A.R. The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. Journal of plant physiology 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurakit, T.; Pathom-Aree, W.; Pumas, C.; Brocklehurst, T.W.; Pekkoh, J.; Srinuanpan, S. High-efficiency production of biomass and biofuel under two-stage cultivation of a stable microalga Botryococcus braunii mutant generated by ethyl methanesulfonate-induced mutation. Renewable Energy 2022, 198, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, B.; Fritsch, J.; Lenz, O. Oxygen-tolerant hydrogenases in hydrogen-based technologies. Current opinion in biotechnology 2011, 22, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beacham, T.; Macia, V.M.; Rooks, P.; White, D.; Ali, S. Altered lipid accumulation in Nannochloropsis salina CCAP849/3 following EMS and UV induced mutagenesis. Biotechnology reports 2015, 7, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumin, J.; Carrier, G.; Rouxel, C.; Charrier, A.; Raimbault, V.; Cadoret, J.-P.; Bougaran, G.; Saint-Jean, B. Towards the optimization of genetic polymorphism with EMS-induced mutagenesis in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Algal Research 2023, 74, 103148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharek, A.; Yahya, A.; Salleh, M.M.; Jamaluddin, H.; Yoshizaki, S.; Hara, H.; Iwamoto, K.; Suzuki, I.; Mohamad, S.E. Improvement and screening of astaxanthin producing mutants of newly isolated Coelastrum sp. using ethyl methane sulfonate induced mutagenesis technique. Biotechnology Reports 2021, 32, e00673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.K.; Maji, D.; Pandey, S.S.; Rout, P.K.; Sundaram, S.; Kalra, A. Rapid budding EMS mutants of Synechocystis PCC 6803 producing carbohydrate or lipid enriched biomass. Algal research 2016, 16, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muramatsu, S.; Atsuji, K.; Yamada, K.; Ozasa, K.; Suzuki, H.; Takeuchi, T.; Hashimoto-Marukawa, Y.; Kazama, Y.; Abe, T.; Suzuki, K. Isolation and characterization of a motility-defective mutant of Euglena gracilis. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsanti, L.; Vismara, R.; Passarelli, V.; Gualtieri, P. Paramylon (β-1, 3-glucan) content in wild type and WZSL mutant of Euglena gracilis. Effects of growth conditions. Journal of applied phycology 2001, 13, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsanti, L.; Gualtieri, P. Paramylon, a potent immunomodulator from WZSL mutant of Euglena gracilis. Molecules 2019, 24, 3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cen, C.; Zhang, K.; Fu, J.; Wu, X.; Wu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Y. Odor-producing response pattern by four typical freshwater algae under stress: Acute microplastic exposure as an example. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 821, 153350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.C.; Ferreira, J.; Raymundo, A. Volatile fingerprint impact on the sensory properties of microalgae and development of mitigation strategies. Current Opinion in Food Science 2023, 51, 101040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, C.; Ellen Harper, M. Metabolic functions of AMPK: aspects of structure and of natural mutations in the regulatory gamma subunits. IUBMB life 2010, 62, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Yanagida, A.; Knight, K.; Engel, A.L.; Vo, A.H.; Jankowski, C.; Sadilek, M.; Tran, V.T.B.; Manson, M.A.; Ramakrishnan, A. Reductive carboxylation is a major metabolic pathway in the retinal pigment epithelium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, 14710–14715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Tang, R.; Hao, X.; Tang, S.; Chen, W.; Jiang, C.; Long, M.; Chen, K.; Hu, X.; Xie, Q. Integrative Transcriptomic and Metabolic Analyses Reveal That Flavonoid Biosynthesis Is the Key Pathway Regulating Pigment Deposition in Naturally Brown Cotton Fibers. Plants 2024, 13, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Jiao, J.; Niu, Q.; Zhu, N.; Huang, Y.; Ke, L.; Tang, S.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y. Cloning and functional analysis of GhDFR1, a key gene of flavonoid synthesis pathway in naturally colored cotton. Molecular Biology Reports 2023, 50, 4865–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Gao, Q.; Luo, C.; Gong, W.; Tang, S.; Zhang, X.; Song, W.; Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Du, X. Flavonoid biosynthetic and starch and sucrose metabolic pathways are involved in the pigmentation of naturally brown-colored cotton fibers. Industrial Crops and Products 2020, 158, 113045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, A.; Felipe, L.d.O.; Bicas, J.L. Production, properties, and applications of α-terpineol. Food and bioprocess technology 2020, 13, 1261–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| EMS concentration | 2 h | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 96 h |

| 0 M (Control) | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ |

| 0.008 M | +++++ | +++++ | ++++ | ++ | ++ |

| 0.012 M | +++++ | ++++ | ++ | + | – |

| 0.016 M | +++++ | +++ | – | – | – |

| Volatile compound |

RT(1) (min) |

RI(2) | Mean±SD | I.D.(3) | |

| Mutant 335 | WT (367) | ||||

| Alcohols (19) | |||||

| 2,2-Dimethyl-3-(1-octylamino)-4-nonanol | 9.25 | 850 | ND(4) | 33.09±46.79 | MS |

| 1-Hexanol | 10.29 | 879 | ND | 80.01±113.15 | MS |

| 1-Octen-3-ol | 13.83 | 984 | ND | 362.54±512.71 | MS |

| 2-Ethylhexanol | 15.39 | 1032 | 148.42±91.16 | 546.36±414.41 | MS/RI(5) |

| 2,2-Dimethyl-1-octanol | 17.44 | 1096 | ND | 102.56±70.91 | MS |

| 1-Hexadecanol | 18.85 | 1145 | 78.01±58.64 | 50.64±46.75 | MS |

| 1-Nonanol | 19.64 | 1172 | ND | 98.97±139.97 | MS |

| 2-Methyl-1-undecanol | 20.23 | 1191 | 51.70±73.11 | ND | MS |

| 1-Decanol | 22.43 | 1271 | 210.94±134.27 | ND | MS |

| 2-Propylheptanol | 24.37 | 1344 | ND | 10.78±15.25 | MS |

| 1-Undecanol | 25.06 | 1370 | 35.14±49.69 | 165.37±233.87 | MS |

| Pentadecanol | 28.41 | 1503 | 123.05±174.02 | ND | MS |

| 1-Docosanol | 28.45 | 1505 | 51.48±72.81 | ND | MS |

| 2,5-Bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-phenol | 28.49 | 1507 | ND | 78.46±110.96 | MS |

| 1-Heptadecanol | 29.07 | 1532 | 75.86±107.28 | ND | MS |

| Tridecanol | 29.92 | 1568 | 686.01±970.17 | 1,342.40±396.45 | MS |

| Isoheptadecanol | 31.35 | 1630 | 64.10±90.66 | 57.52±81.35 | MS |

| (E)-3-Nonen-1-ol | 31.80 | 1650 | 7.95±11.25 | ND | MS |

| 1-Octadecanol | 33.69 | >1700 | 28.24±39.93 | 100.94±142.75 | MS |

| Aldehydes (7) | |||||

| Hexanal | 7.99 | 810 | ND | 231.23±327.01 | MS/RI |

| 2,2-Dideutero heptadecanal | 10.04 | 872 | ND | 73.52±103.97 | MS |

| Benzaldehyde | 13.24 | 967 | ND | 106.47±150.57 | MS/RI |

| Tetradecanal | 26.00 | 1406 | 145.74±206.11 | 149.41±211.29 | MS |

| 3-Methyl-3-cyclohexen-1-carboxaldehyde | 28.91 | 1525 | ND | 38.06±53.82 | MS |

| Tetradecanal | 30.78 | 1604 | 107.67±117.11 | ND | MS |

| 4-Octadecenal | 33.53 | >1700 | ND | 9.68±13.69 | MS |

| Sulfur-containing compounds (3) | |||||

| Di-tert-dodecyldisulfide | 17.81 | 1108 | 39.69±56.14 | ND | MS |

| Dihexylsulfide | 18.57 | 1136 | ND | 4.43±6.27 | MS |

| Benzothiazole | 21.26 | 1228 | 80.73±34.47 | 282.74±162.22 | MS/RI |

| Acids & esters (18) | |||||

| 2-Propenoic acid | 5.55 | <800 | ND | 525.59±743.30 | MS |

| Methyl methacrylate | 5.59 | <800 | ND | 118.93±168.20 | MS |

| Hexyl formate | 10.21 | 877 | ND | 454.78±643.16 | MS |

| 4-Ethylbenzoic acid | 11.31 | 907 | ND | 393.45±556.42 | MS |

| Sulfurous acid, butyl nonyl ester | 16.08 | 1055 | ND | 50.38±71.24 | MS |

| Octyl chloroformate | 16.68 | 1073 | ND | 275.03±388.96 | MS |

| Acetic acid, octyl ester | 16.69 | 1074 | ND | 96.28±136.16 | MS |

| Methyl salicylate | 20.41 | 1196 | ND | 236.47±334.42 | MS |

| Decyl ether | 20.96 | 1217 | ND | 26.67±0.05 | MS |

| Cyclohexyl isothiocyanate | 21.49 | 1237 | 35.79±50.61 | 252.89±106.97 | MS |

| Didecyl sebacate | 26.97 | 1446 | ND | 26.82±37.93 | MS |

| Heptadecyl heptadecanoate | 27.95 | 1485 | 47.75±67.53 | ND | MS |

| Octadecyl bromoacetate | 29.08 | 1533 | ND | 32.61±46.12 | MS |

| Chloroacetic acid, octadecyl ester | 34.29 | >1700 | ND | 48.87±69.11 | MS |

| Dodecyl fluoroacetate | 34.92 | >1700 | 9.68±13.69 | ND | MS |

| Undec-2-enylester dichloroacetic acid | 35.09 | >1700 | 6.17±8.73 | ND | MS |

| 8,11,14-Eicosatrienoic acid, methyl ester | 35.89 | >1700 | ND | 9.89±13.99 | MS |

| Hexadecyl bromoacetate | 36.34 | >1700 | ND | 47.08±66.57 | MS |

| Heterocyclic compounds (6) | |||||

| Pyridine | 6.52 | <800 | ND | 180.37±89.56 | MS |

| Pyridiniumfluorosulfate | 6.79 | <800 | ND | 6.07±8.58 | MS |

| 2-Pentylfuran | 14.24 | 995 | ND | 340.05±480.91 | MS |

| Camphor | 19.00 | 1150 | ND | 15.84±22.40 | MS/RI |

| 2-Chloro-3,4-diphenylbenzofuro [2,3-b] pyridine | 25.34 | 1381 | ND | 30.83±43.60 | MS |

| Hydrocarbons (67) | |||||

| 1,2-Bis(trimethylsilyl)-benzene | 7.91 | 807 | ND | 155.45±219.84 | MS |

| 2,4-Dimethylheptane | 8.34 | 821 | 12.15±17.18 | ND | MS |

| 4-Methyloctane | 9.78 | 865 | 170.19±240.69 | 392.21±554.66 | MS |

| 2,3,4-Trimethylhexane | 10.09 | 874 | 24.48±34.62 | ND | MS |

| 2-Methyl-1-heptene | 10.34 | 881 | ND | 30.58±43.25 | MS |

| Styrene | 10.98 | 897 | ND | 201.00±284.26 | MS/RI |

| 2,7-Dimethyloctane | 12.18 | 936 | ND | 43.37±61.34 | MS |

| 2,6-Dimethyloctane | 12.33 | 940 | ND | 31.72±44.85 | MS |

| Decane | 13.00 | 960 | 473.20±214.07 | 3,814.51±4,302.46 | MS |

| 2-Methylnonane | 13.29 | 969 | 96.32±136.21 | ND | MS |

| Nonadecane | 13.33 | 970 | 63.78±15.33 | 478.92±345.75 | MS |

| 3-Methylhexane | 13.54 | 976 | ND | 134.60±190.35 | MS |

| 2,4-Dimethylhexane | 13.73 | 981 | ND | 243.84±344.85 | MS |

| 1-Hexyl-3-methylcyclopentane | 14.08 | 990 | 92.92±131.41 | ND | MS |

| 3,6-Dimethylundecane | 14.78 | 1012 | 40.20±56.85 | 288.22±239.30 | MS |

| 2,7-Dimethylundecane | 14.94 | 1017 | 32.06±45.34 | 184.92±261.51 | MS |

| 2,5-Dimethylnonane | 15.11 | 1023 | 50.27±71.09 | 521.16±416.32 | MS |

| 4-Methyldecane | 15.19 | 1026 | 202.41±169.29 | 1,352.80±994.61 | MS |

| Pentyl-cyclopentane | 15.61 | 1040 | ND | 109.91±155.43 | MS |

| 3-Ethyl-5-(2-ethylbutyl)-octadecane | 15.75 | 1044 | 6.79±9.60 | 19.85±28.08 | MS |

| Dodecane | 16.15 | 1057 | 1,230.86±37.26 | 3,786.44±2624.40 | MS |

| 2,6,11-Trimethyldodecane | 16.20 | 1058 | ND | 53.89±76.21 | MS |

| Octadecane | 16.46 | 1066 | 107.69±152.30 | ND | MS |

| 2,4-Dimethylundecane | 16.47 | 1067 | 79.67±40.12 | 80.65±27.23 | MS |

| 4-Ethyl-1,2-dimethyl-benzene | 17.18 | 1088 | ND | 40.07±56.67 | MS |

| Undecane | 17.57 | 1100 | 23.69±33.50 | 229.53±85.60 | MS/RI |

| 4-Methylundecane | 17.64 | 1102 | 242.59±59.44 | 421.89±32.85 | MS |

| Heneicosane | 17.81 | 1109 | ND | 304.15±304.11 | MS |

| 1,2,3,4-Tetramethylbenzene | 18.23 | 1123 | ND | 41.85±59.18 | MS |

| 2-Methylundecane | 18.39 | 1129 | ND | 123.24±145.29 | MS |

| 2,6,10-Trimethyltetradecane | 18.57 | 1135 | ND | 23.03±32.57 | MS |

| (E)-1-Butyl-2-methylcyclopropane | 19.07 | 1153 | ND | 16.07±22.73 | MS |

| 6-Ethyl-2-methyloctane | 19.31 | 1161 | ND | 56.13±79.38 | MS |

| Squalane | 19.44 | 1165 | ND | 54.53±77.12 | MS |

| Cyclododecane | 20.24 | 1191 | 8,955.69±8,032.29 | 17,120.77±5,004.40 | MS |

| Tritetracontane | 20.61 | 1204 | ND | 123.01±173.96 | MS |

| 5-Methyloctadecane | 20.77 | 1210 | 17.02±24.07 | 55.07±77.87 | MS |

| 2,6-Dimethylundecane | 20.86 | 1213 | ND | 240.77±96.84 | MS |

| 2,4-Dimethylicosane | 20.96 | 1217 | ND | 25.64±36.26 | MS |

| 3-Ethyltetracosane | 21.08 | 1221 | ND | 120.26±170.08 | MS |

| Tetracosane | 21.69 | 1244 | ND | 140.68±0.59 | MS |

| 2,4,6-Trimethyldecane | 21.84 | 1249 | 39.19±21.94 | 64.26±90.88 | MS |

| 1,3-Bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-benzene | 22.03 | 1257 | 181.02±90.18 | 655.22±220.60 | MS |

| 4-Ethylundecane | 22.22 | 1263 | 51.18±72.38 | 10.07±14.24 | MS |

| Nonacosane | 22.23 | 1264 | ND | 126.54±178.95 | MS |

| Tetradecane | 22.67 | 1279 | 116.96±100.04 | 1,545.25±1,439.78 | MS |

| 1,3-Dichloro-2-methoxybenzene | 22.97 | 1290 | ND | 16.32±23.09 | MS |

| Tridecane | 23.04 | 1292 | 18.01±25.47 | 77.50±109.60 | MS/RI |

| 2,3,5,8-Tetramethyldecane | 23.18 | 1297 | 9.06±12.82 | ND | MS |

| Hexacosane | 23.25 | 1299 | ND | 32.14±45.45 | MS |

| 2,3,5-Trimethyldecane | 23.41 | 1306 | ND | 35.18±49.75 | MS |

| 4-Methyltetradecane | 24.31 | 1341 | ND | 10.17±14.39 | MS |

| 2,6,10-Trimethyltridecane | 24.32 | 1342 | ND | 6.31±8.93 | MS |

| 10-Methylnonadecane | 24.82 | 1361 | ND | 6.62±9.36 | MS |

| 1,1-Bis(dodecyloxy)-hexadecane | 26.68 | 1434 | 12.28±17.36 | 87.10±72.05 | MS |

| 2-Methyltetradecane | 27.29 | 1459 | ND | 112.17±21.79 | MS |

| Docosane | 28.10 | 1491 | ND | 108.51±55.08 | MS |

| 1-Chlorooctadecane | 28.85 | 1523 | ND | 7.81±11.05 | MS |

| 3-Methyltridecane | 29.15 | 1535 | ND | 38.21±54.03 | MS |

| (E)-3-Octadecene | 29.25 | 1540 | ND | 49.04±69.36 | MS |

| 2-Methyloctadecane | 29.81 | 1564 | ND | 58.60±82.87 | MS |

| Hexadecane | 30.46 | 1591 | 32.71±46.25 | 756.99±541.19 | MS/RI |

| 2-Methyltetracosane | 31.86 | 1652 | ND | 21.11±29.86 | MS |

| (E)-2-Tetradecene | 32.16 | 1665 | 4,124.93±4,333.01 | 8,371.63±1,937.56 | MS |

| 1-Fluorododecane | 32.64 | 1686 | 61.35±86.77 | ND | MS |

| Cyclotetradecane | 34.92 | >1700 | 80.22±113.44 | 77.86±8.47 | MS |

| 1,3-Cyclooctadiene | 40.67 | >1700 | ND | 50.93±72.03 | MS |

| Ketones (5) | |||||

| 2-(4′-Chloro) styrylchromone | 14.48 | 1002 | ND | 1,822.18±2,576.95 | MS |

| Acetophenone | 16.60 | 1071 | 10.63±15.04 | 119.97±63.45 | MS |

| 2-Nonanone | 17.35 | 1093 | ND | 41.34±58.46 | MS |

| 1,4-Hexadecansultone | 33.70 | >1700 | ND | 15.22±21.52 | MS |

| 2,11-Dodecanedione | 35.53 | >1700 | ND | 13.01±18.39 | MS |

| Volatile compound | RT(1) | Relative Intensity | Odor description | |

| (min) | Mutant 335 | WT (367) | ||

| Alcohols | ||||

| 1-Hexanol | 10.29 | 0 | 1 | Green |

| 1-Octen-3-ol | 13.83 | 0 | 2 | Mugwort |

| 2-Methyl-1-undecanol | 20.23 | 2 | 0 | Herbaceous |

| Aldehydes | ||||

| Hexanal | 7.99 | 0 | 1 | Green tea |

| Acid & esters | ||||

| Hexyl formate | 10.21 | 0 | 2 | Barley tea |

| 4-Ethylbenzoic acid | 11.31 | 0 | 2 | Green tea |

| Hydrocarbons | ||||

| 2-Methyl-1-heptene | 10.34 | 0 | 1 | Mugwort |

| Styrene | 10.98 | 0 | 1 | Mugwort |

| 2,6-Dimethyloctane | 12.33 | 0 | 2 | Roasted |

| 2,4,6-Trimethyldecane | 21.84 | 2 | 1 | Green |

| 1,3-Bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-benzene | 22.03 | 1 | 1 | Herbaceous |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).