Submitted:

16 June 2025

Posted:

17 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

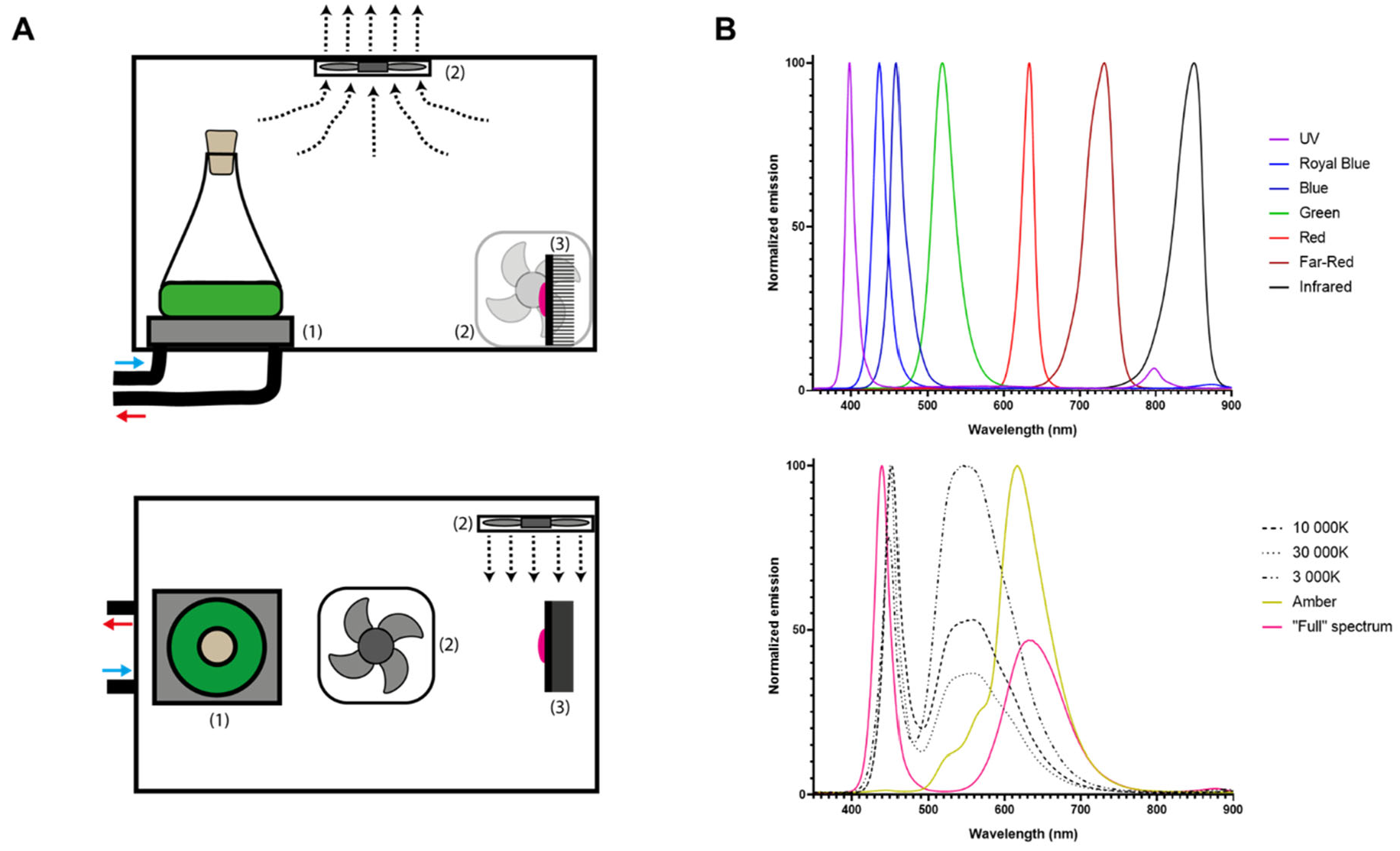

2. Culture System Design

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Culture Conditions and Growth Curves

3.2. Pigment Quantification

3.4. Paramylon Quantification

3.5. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

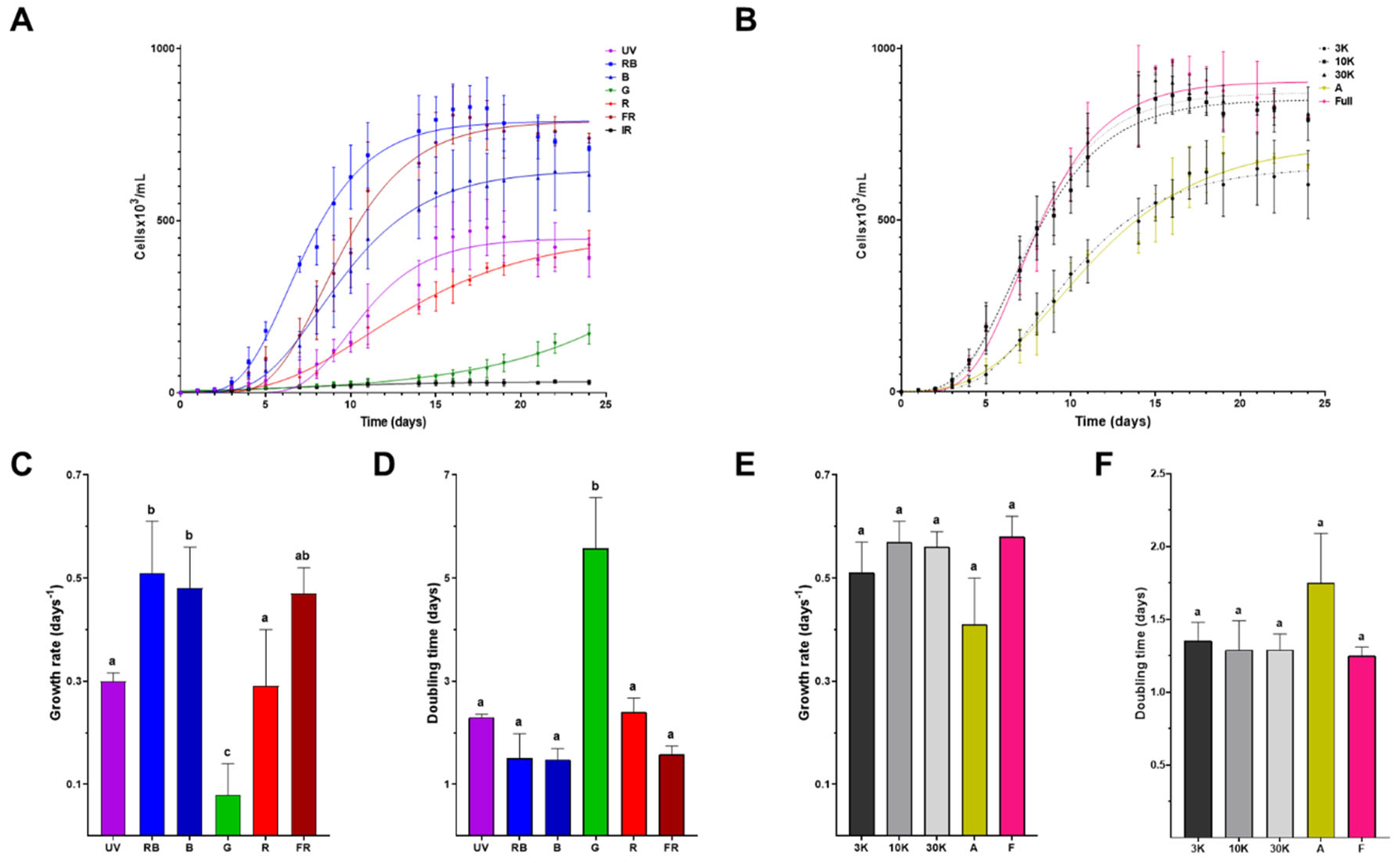

- Light wavelength as an environmental factor of Euglena gracilis growth

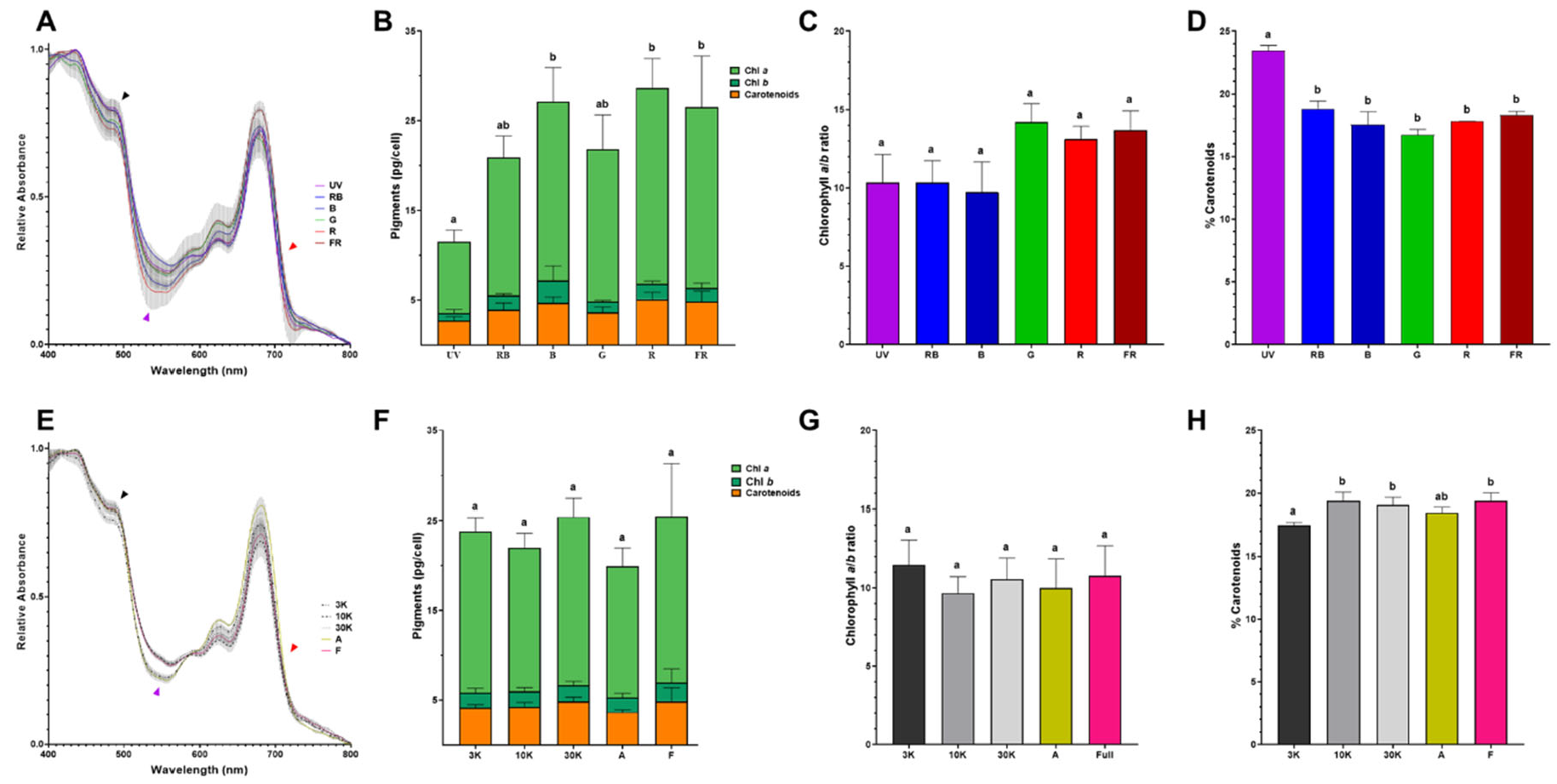

- E. gracilis adapts its Pigment composition as an acclimatization strategy to specific light regimes

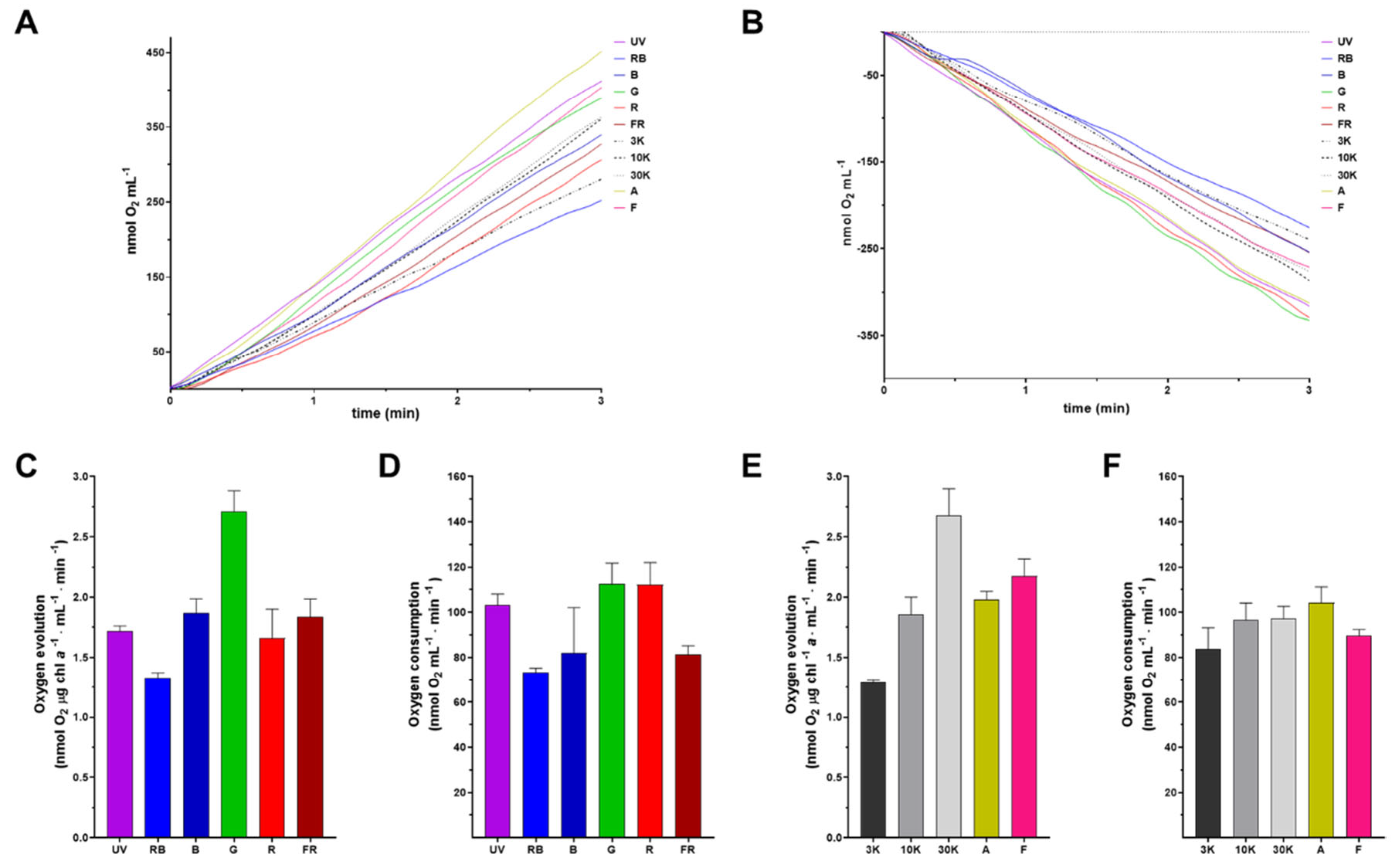

- E. gracilis photosystem II can use different wavelengths for oxygen evolution

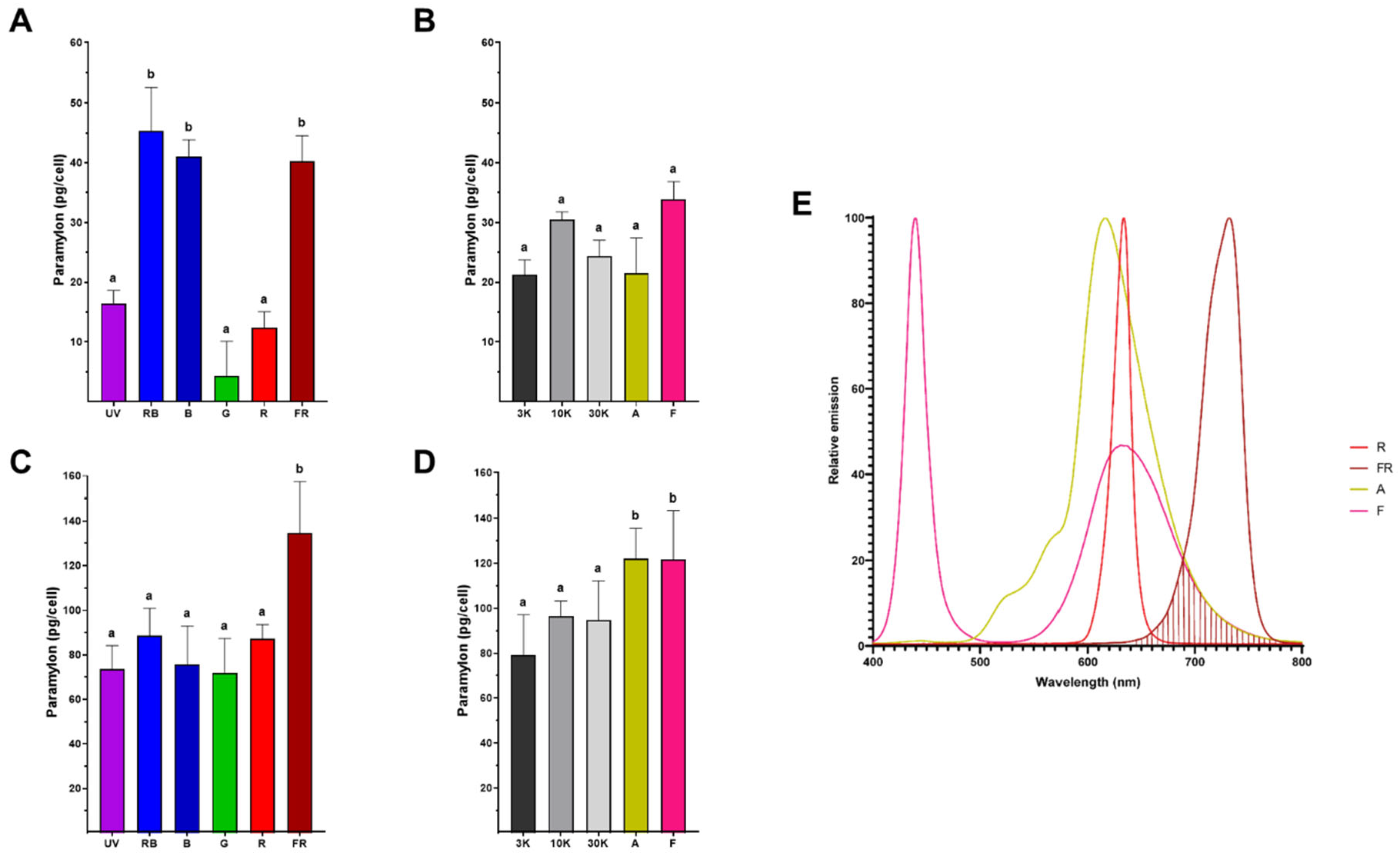

- Far-red improves paramylon production in photoautotrophically grown E. gracilis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UV | Ultraviolet light |

| RB | Royal Blue light |

| B | Blue light |

| G | Green light |

| R | Red light |

| FR | Far-Red light |

| IR | Infrared light |

| 3K | White light 3000K temperature |

| 10K | White light 10000K temperature |

| 30K | White light 30000K temperature |

| A | Amber light |

| F | Full-spectrum light |

| Chl a | Chlorophyll a |

| Chl b | Chlorophyll b |

| TMP | Tris-minimum-phosphate medium |

References

- Yen, H.W.; Hu, I.C.; Chen, C.Y.; Ho, S.H.; Lee, D.J.; Chang, J.S. Microalgae-based biorefinery--from biofuels to natural products. Bioresour Technol 2013, 135, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rial, R.C. Biofuels versus climate change: Exploring potentials and challenges in the energy transition. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 196, 114369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, N.; Ben-Shem, A. The complex architecture of oxygenic photosynthesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2004, 5, 971–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.; Ulhassan, Z.; Brestic, M.; Zivcak, M. ; Weijun Zhou; Allakhverdiev, S. I.; Yang, X.; Safdar, M.E.; Yang, W.; Liu, W. Photosynthesis research under climate change. Photosynth Res 2021, 150, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Li, J.; Qian, J.; Wang, B.; Liu, J.; Xu, R.; Chen, P.; Zhou, W. Recent advances in CO. Chemosphere 2023, 319, 137987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, D.L.; McCauley, J.; Labeeuw, L.; Ray, P.; Kuzhiumparambil, U.; Hall, C.; Doblin, M.; Nguyen, L.N.; Ralph, P.J. How microalgal biotechnology can assist with the UN Sustainable Development Goals for natural resource management. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability 2021, 3, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V.; Pereira, R.N.; Vicente, A.A.; Dias, O.; Geada, P. Microalgae biomass as an alternative source of biocompounds: New insights and future perspectives of extraction methodologies. Food Res Int 2023, 173, 113282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leander, B.S.; Lax, G.; Karnkowska, A.; Simpson, A.G.B. Euglenida. In Handbook of the Protists, Archibald, J.M., Simpson, A.G.B., Slamovits, C.H., Margulis, L., Melkonian, M., Chapman, D.J., Corliss, J.O., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monfils, A.K. ; E. , T.R.; and Bellairs, E.F. Characterization of paramylon morphological diversity in photosynthetic euglenoids (Euglenales, Euglenophyta). Phycologia 2011, 50, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebenezer, T.E.; Low, R.S.; O'Neill, E.C.; Huang, I.; DeSimone, A.; Farrow, S.C.; Field, R.A.; Ginger, M.L.; Guerrero, S.A.; Hammond, M.; et al. Euglena International Network (EIN): Driving euglenoid biotechnology for the benefit of a challenged world. Biol Open 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gissibl, A.; Sun, A.; Care, A.; Nevalainen, H.; Sunna, A. Bioproducts From. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2019, 7, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedard, S.; Roxborough, E.; O'Neill, E.; Mangal, V. The biomolecules of Euglena gracilis: Harnessing biology for natural solutions to future problems. Protist 2024, 175, 126044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feuzing, F.; Mbakidi, J.P.; Marchal, L.; Bouquillon, S.; Leroy, E. A review of paramylon processing routes from microalga biomass to non-derivatized and chemically modified products. Carbohydr Polym 2022, 288, 119181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiyama, A.; Hata, S.; Suzuki, K.; Yoshida, E.; Nakano, R.; Mitra, S.; Arashida, R.; Asayama, Y.; Yabuta, Y.; Takeuchi, T. Oral administration of paramylon, a beta-1,3-D-glucan isolated from Euglena gracilis Z inhibits development of atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions in NC/Nga mice. J Vet Med Sci 2010, 72, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lim, D.; Lee, D.; Yu, J.; Lee, T. Valorization of corn steep liquor for efficient paramylon production using Euglena gracilis: The impact of precultivation and light-dark cycle. Algal Research 2022, 61, 102587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Bolaños, M.; Vargas-Romero, G.; Jaguer-García, G.; Aguilar-Gonzalez, Z.I.; Lagos-Romero, V.; Miranda-Astudillo, H.V. Antares I: a Modular Photobioreactor Suitable for Photosynthesis and Bioenergetics Research. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2024, 196, 2176–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Li, J.; Qin, H.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Liu, C.; Zheng, L.; Wang, J. Paramylon from. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 797096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubiyatno; Matsui, T. ; Mori, K.; Toyama, T. Paramylon production by Euglena gracilis via mixotrophic cultivation using sewage effluent and waste organic compounds. Bioresource Technology Reports 2021, 15, 100735. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Zavala, J.S.; Ortiz-Cruz, M.A.; Mendoza-Hernández, G.; Moreno-Sánchez, R. Increased synthesis of α-tocopherol, paramylon and tyrosine by Euglena gracilis under conditions of high biomass production. J Appl Microbiol 2010, 109, 2160–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoe, S.; Yamanaka, C.; Koketsu, K.; Nishioka, M.; Onaka, N.; Nishida, N.; Takahashi, M. Effects of Paramylon Extracted from Euglena gracilis EOD-1 on Parameters Related to Metabolic Syndrome in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, A.; Sugimoto, R.; Suzuki, K.; Shirakata, Y.; Hashiguchi, T.; Yoshida, C.; Nakano, Y. Anti-fibrotic activity of. Food Sci Nutr 2019, 7, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, K.; Ogushi, M.; Nakashima, A.; Nakano, Y.; Suzuki, K. Accelerated Wound Healing on the Skin Using a Film Dressing with β-Glucan Paramylon. In Vivo 2018, 32, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, H.; Zhao, J.; Li, H.; Fan, D. Paramylon hydrogel: A bioactive polysaccharides hydrogel that scavenges ROS and promotes angiogenesis for wound repair. Carbohydr Polym 2022, 289, 119467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadiveloo, A.; Moheimani, N.R.; Cosgrove, J.J.; Parlevliet, D.; Bahri, P.A. Effects of different light spectra on the growth, productivity and photosynthesis of two acclimated strains of Nannochloropsis sp.

- Xin, K.; Guo, R.; Wang, X.; Yu, Z.; Mao, W.; Cheng, C.; Che, G.; Qian, L.; Cheng, J.; Yang, W.; et al. Photoautotrophic Growth and Cell Division of Euglena gracilis with Mixed Red and Blue Wavelengths. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2024, 63, 4746–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, R.J. Consistent Sets of Spectrophotometric Chlorophyll Equations for Acetone, Methanol and Ethanol Solvents. Photosynthesis Research 2006, 89, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspers, H. J. D. H. Strickland and T. R. Parsons: A Practical Handbook of Seawater Analysis. Ottawa: Fisheries Research Board of Canada, Bulletin 167, 1968. 293 pp. Internationale Revue der gesamten Hydrobiologie und Hydrographie 1970, 55, 167–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gain, G.; Vega de Luna, F.; Cordoba, J.; Perez, E.; Degand, H.; Morsomme, P.; Thiry, M.; Baurain, D.; Pierangelini, M.; Cardol, P. Trophic state alters the mechanism whereby energetic coupling between photosynthesis and respiration occurs in Euglena gracilis. New Phytol 2021, 232, 1603–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, S.; van Iersel, M.W.; Bugbee, B. Photosynthesis in sun and shade: the surprising importance of far-red photons. New Phytol 2022, 236, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, P.S.; Barreira, L.A.; Pereira, H.G.; Perales, J.A.; Varela, J.C. Light emitting diodes (LEDs) applied to microalgal production. Trends Biotechnol 2014, 32, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Slavens, S.; Crunkleton, D.W.; Johannes, T.W. Interactive effect of light quality and temperature on Chlamydomonas reinhardtii growth kinetics and lipid synthesis. Algal Research 2021, 53, 102127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Lee, Y.; Han, S.H.; Hwang, S.J. The effects of wavelength and wavelength mixing ratios on microalgae growth and nitrogen, phosphorus removal using Scenedesmus sp. for wastewater treatment. Bioresour Technol 2013, 130, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smayda, T.J.; Mitchell-Innes, B. Dark survival of autotrophic, planktonic marine diatoms. Marine Biology 1974, 25, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattos, E.R.; Singh, M.; Cabrera, M.L.; Das, K.C. Enhancement of biomass production in Scenedesmus bijuga high-density culture using weakly absorbed green light. Biomass and Bioenergy 2015, 81, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubín, Š.; Borns, E.; Doucha, J.; Seiss, U. Light Absorption and Production Rate of Chlorella vulgaris in Light of Different Spectral Composition. Biochemie und Physiologie der Pflanzen 1983, 178, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ievina, B.; Romagnoli, F. Unveiling underlying factors for optimizing light spectrum to enhance microalgae growth. Bioresour Technol 2025, 418, 131980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paper, M.; Glemser, M.; Haack, M.; Lorenzen, J.; Mehlmer, N.; Fuchs, T.; Schenk, G.; Garbe, D.; Weuster-Botz, D.; Eisenreich, W.; et al. Efficient Green Light Acclimation of the Green Algae. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10, 885977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, F.X.; Schiff, J.A. Chlorophyll-Protein Complexes from Euglena gracilis and Mutants Deficient in Chlorophyll b: II. Polypeptide Composition. Plant Physiol 1986, 80, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Astudillo, H.; Arshad, R.; Vega de Luna, F.; Aguilar-Gonzalez, Z.; Forêt, H. ; Feller, T; Gervasi, A.; Nawrocki, W.; Counson, C.; Morsomme, P.; Degand, H.; Baurain, D.; Kouřil, R.; Cardol, P., A Unique LHCE Light-Harvesting protein Family is involved in Photosystem I and II Far-Red Absorption in Euglena gracilis 2025, bioRxiv 2025.05.07.652572; [CrossRef]

- Tanno, Y.; Kato, S.; Takahashi, S.; Tamaki, S.; Takaichi, S.; Kodama, Y.; Sonoike, K.; Shinomura, T. Light dependent accumulation of β-carotene enhances photo-acclimation of Euglena gracilis. J Photochem Photobiol B 2020, 209, 111950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoka, T. Carotenoids as natural functional pigments. J Nat Med 2020, 74, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, F.X. and Gantt, E. One ring or two? Determination of ring number in carotenoids by lycopene ɛ-cyclases. PNAS 2001, 98(5) 2905-2910. [CrossRef]

- Mutschlechner, M.; Walter, A.; Colleselli, L.; Griesbeck, C.; Schöbel, H. Enhancing carotenogenesis in terrestrial microalgae by UV-A light stress. J Appl Phycol 2022, 34, 1943–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, S.; van Iersel, M. W.; Bugbee, B. Photosynthesis in sun and shade: the surprising importance of far-red photons. New Phytologist 2022, 236: 538–546. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Harvey, P.J. Carotenoid Production by Dunaliella salina under Red Light. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 123; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Feng, L.; Wu, X.; Fan, Y.; Raza, M.; Wang, X. , Yong, T.; Liu, W.; Liu, J.; Du, J.; Shu, K.; Yang, W. Low red/far-red ratio as a signal promotes carbon assimilation of soybean seedlings by increasing the photosynthetic capacity. BMC Plant Biol 2020, 20: 148. [CrossRef]

- Piiparinena, J.; Barthb, D.; Eriksenc, N.T.; Teirb, S.; Spillinga, K.; Wiebeb, M.G. Microalgal CO2 capture at extreme pH values. Algal Research 2018, 32: 321–328. [CrossRef]

- Krajcovic, J.; Vestega, M.; Schwartzbachc, S.D. Euglenoid flagellates: A multifaceted biotechnology platform. Journal of Biotechnology 2015, 202: 135–145. [CrossRef]

- Grimm, P.; Risse, J.M.; Cholewa, D.; Müller, J.M.; Beshay, U.; Friehs, K.; Flaschel, E. Applicability of Euglena gracilis for biorefineries demonstrated by the production of -tocopherol and paramylon followed by anaerobic digestion. Journal of Biotechnology 2015, 215: 72–79. [CrossRef]

- Inui, H.; Miyatake, K.; Nakano, Y.; Kitaoka, S. Production and Composition of Wax Esters by Fermentation of Euglena gracilis. Agricultural and Biological Chemistry 1983, 47:11, 2669-2671. [CrossRef]

- Yagi, K.; Hamada, K.; Hlrata, K.; Miyamoto, K.; Miura, Y.; Akano, T.; Fukatu, K.; Ikuta, Y.; Nakamura, H. Stimulatory effect of red light on starch accumulation in a marine green alga, Chlamydomonas sp. strain MGA161. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 1994, 45, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, A.; Dimitriades-Lemaire, A.; Lancelon-Pin, C.; Putaux, J.; Dauvillée, D.; Petroutsos, D.; Alvarez Diaz, P.; Sassi, J.; Li-Beisson, Y.; Fleury, G. Red light induces starch accumulation in Chlorella vulgaris without affecting photosynthesis efficiency, unlike abiotic stress. Algal Research 2024, 80: 103515. [CrossRef]

- 5Meeuse, B.J.D. Breakdown of paramylon and laminarin by digestive enzymes of Lamellibranchs - an important ecological feature. Basteria 1964, 28, 5: 67–86. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).