Submitted:

15 January 2025

Posted:

15 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

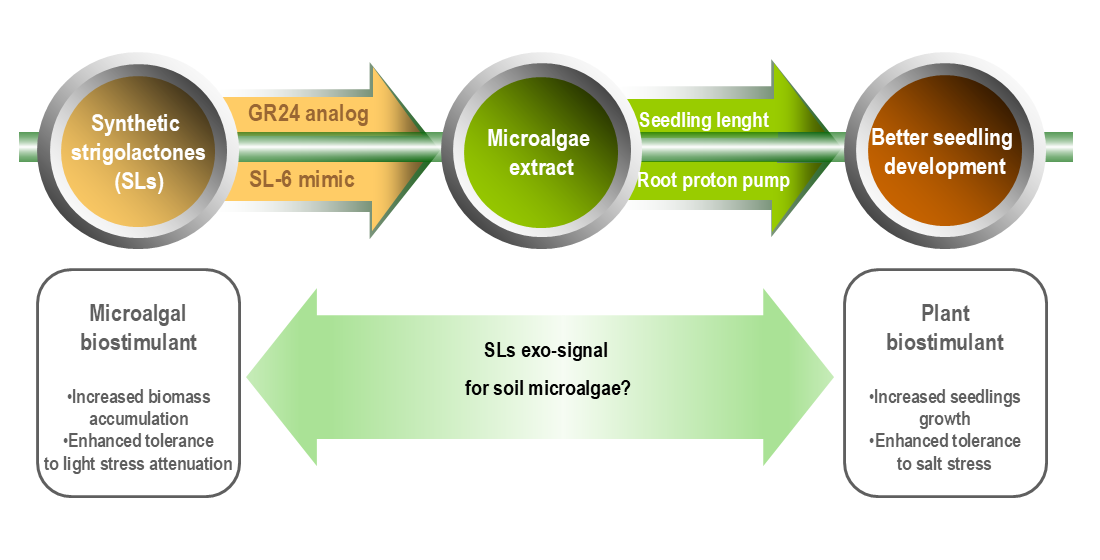

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

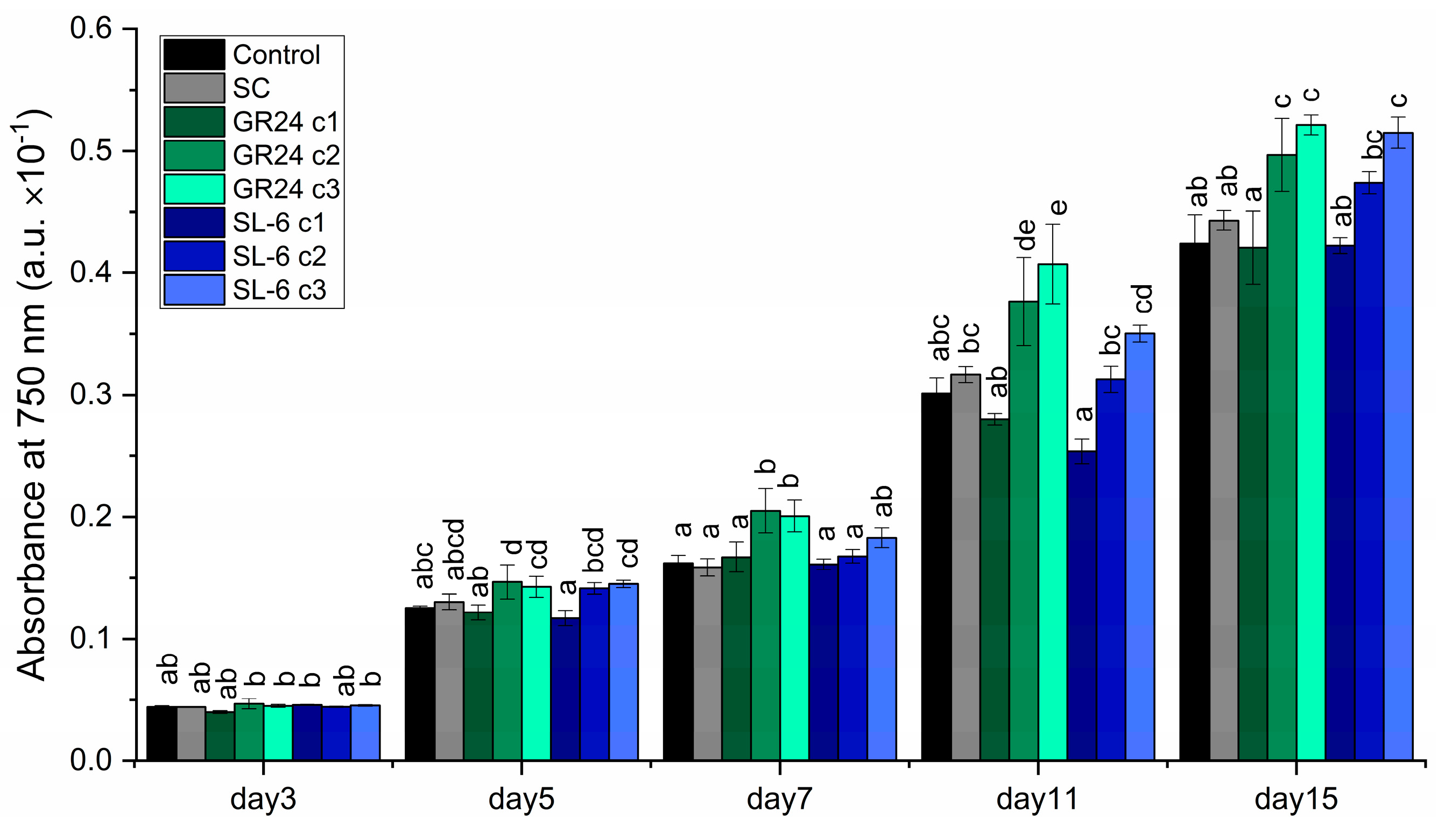

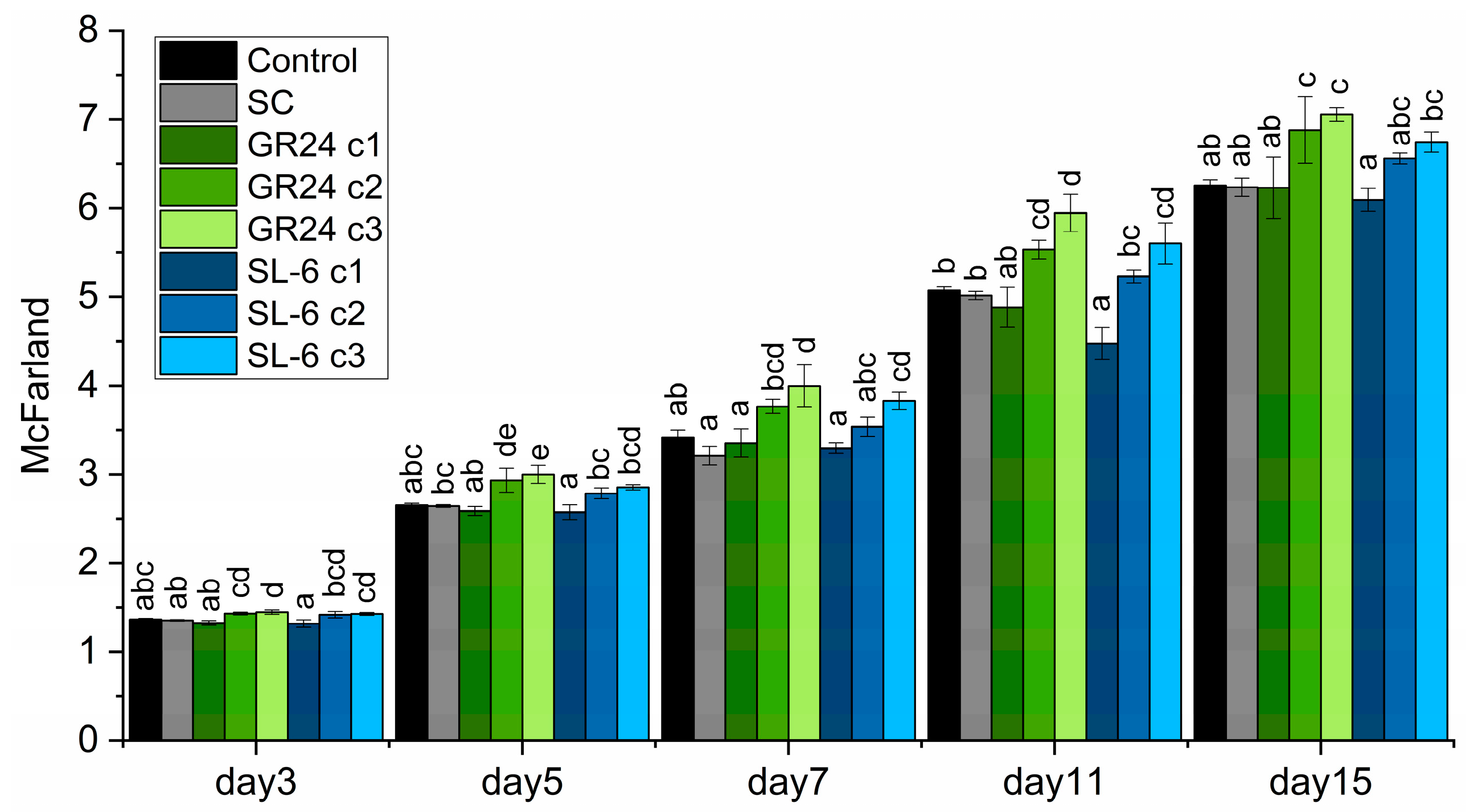

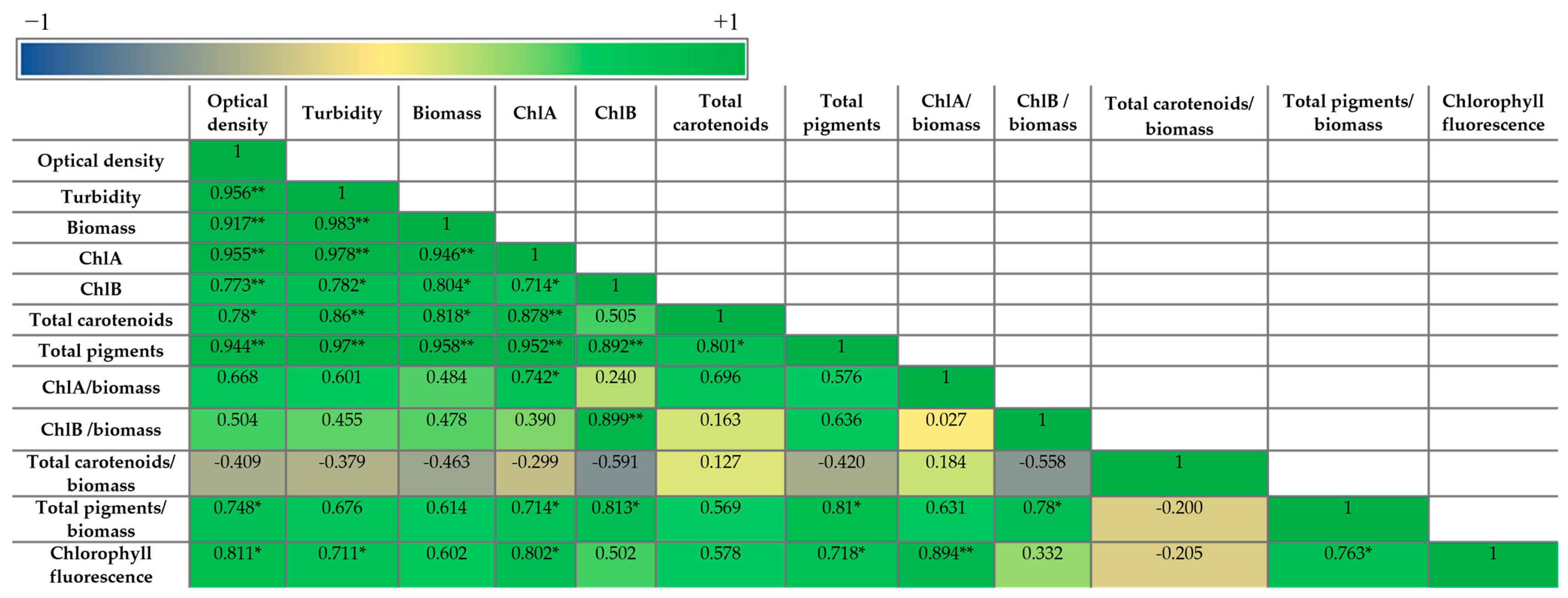

2.1. Microalgal Growth Parameters

2.1.1. Optical Density

2.1.2. Microalgal Culture Turbidity

2.1.3. Biomass Quantification

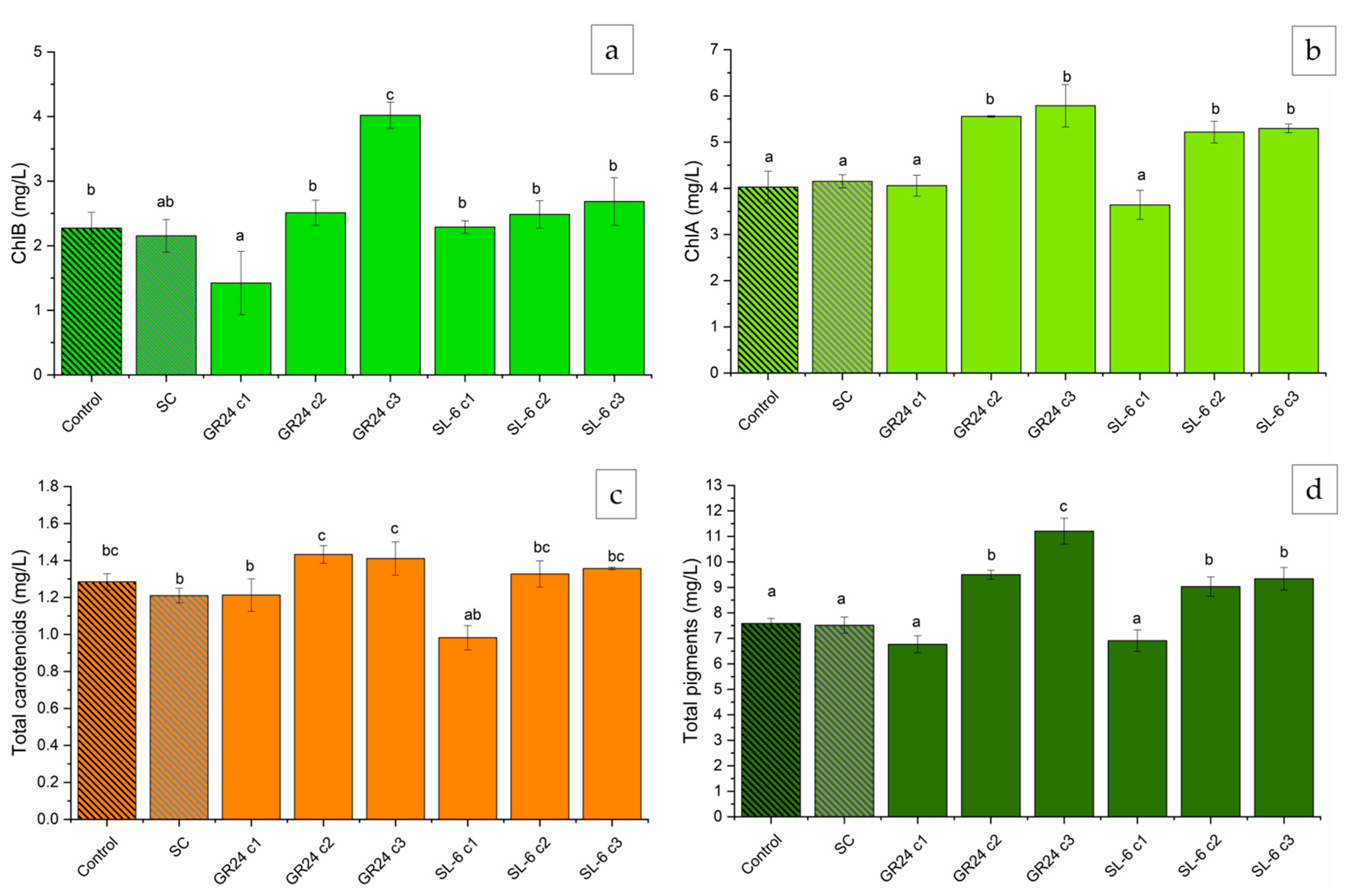

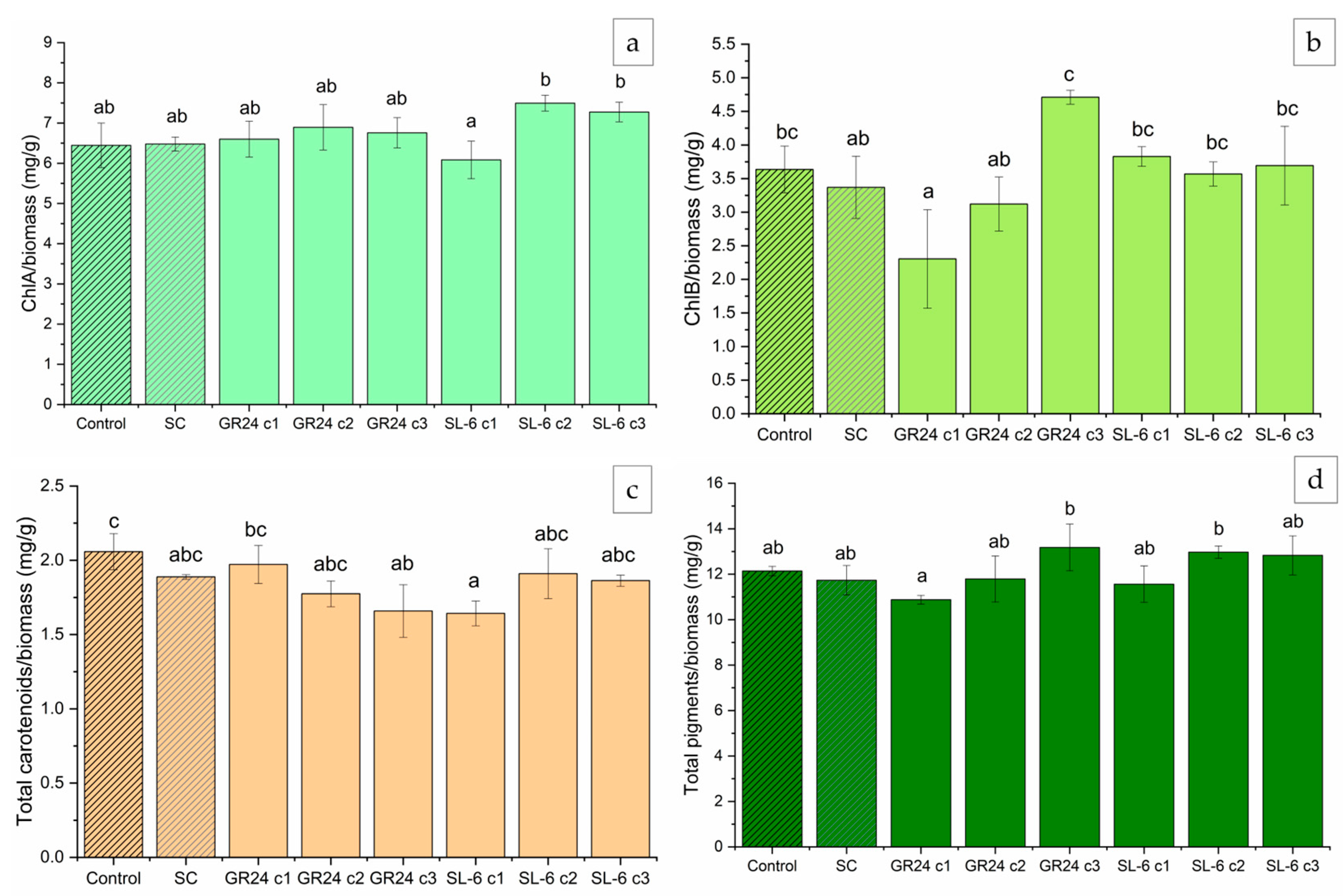

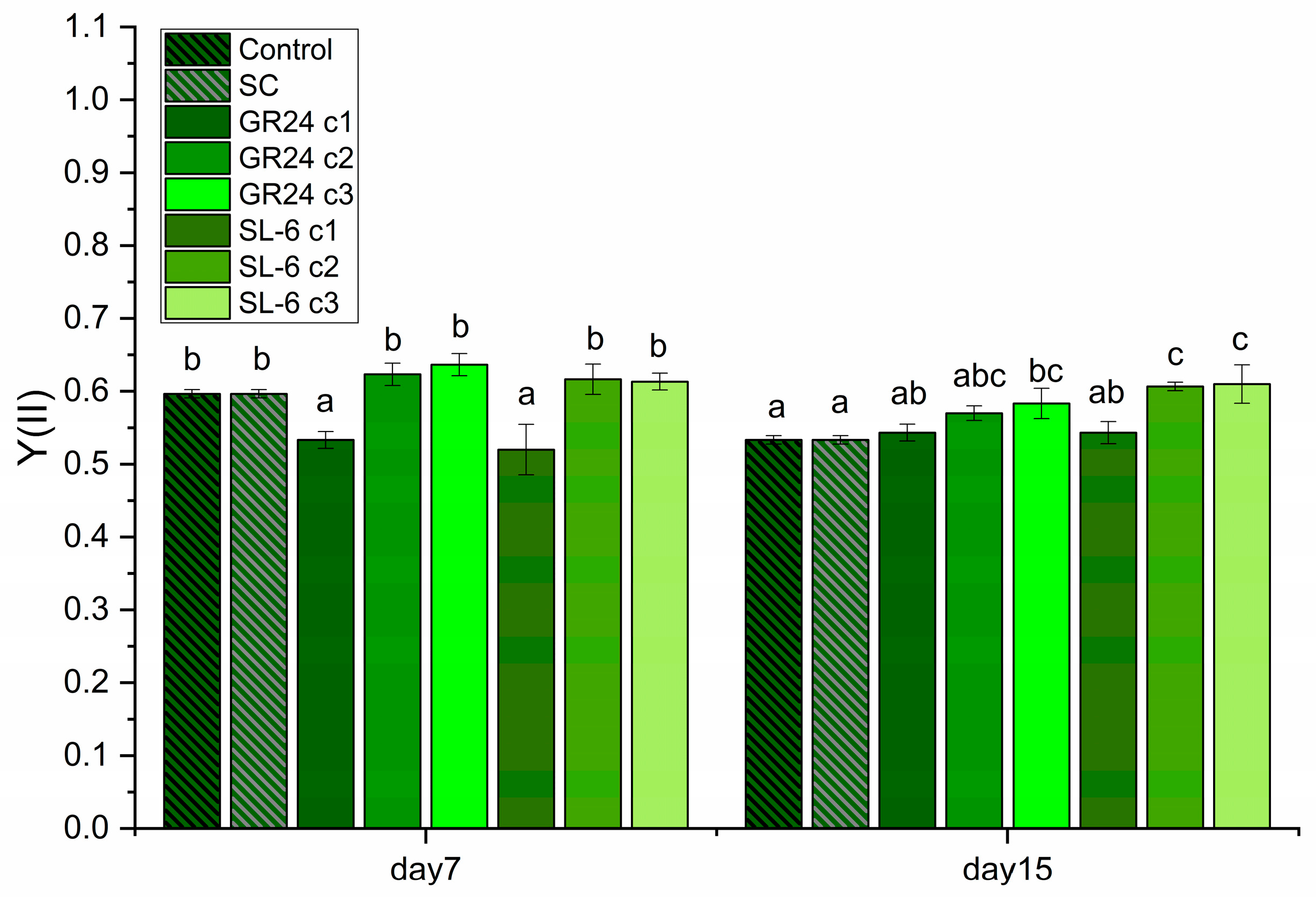

2.1.4. Extracted Pigments Concentration

2.2. Mung Seedlings Biotests

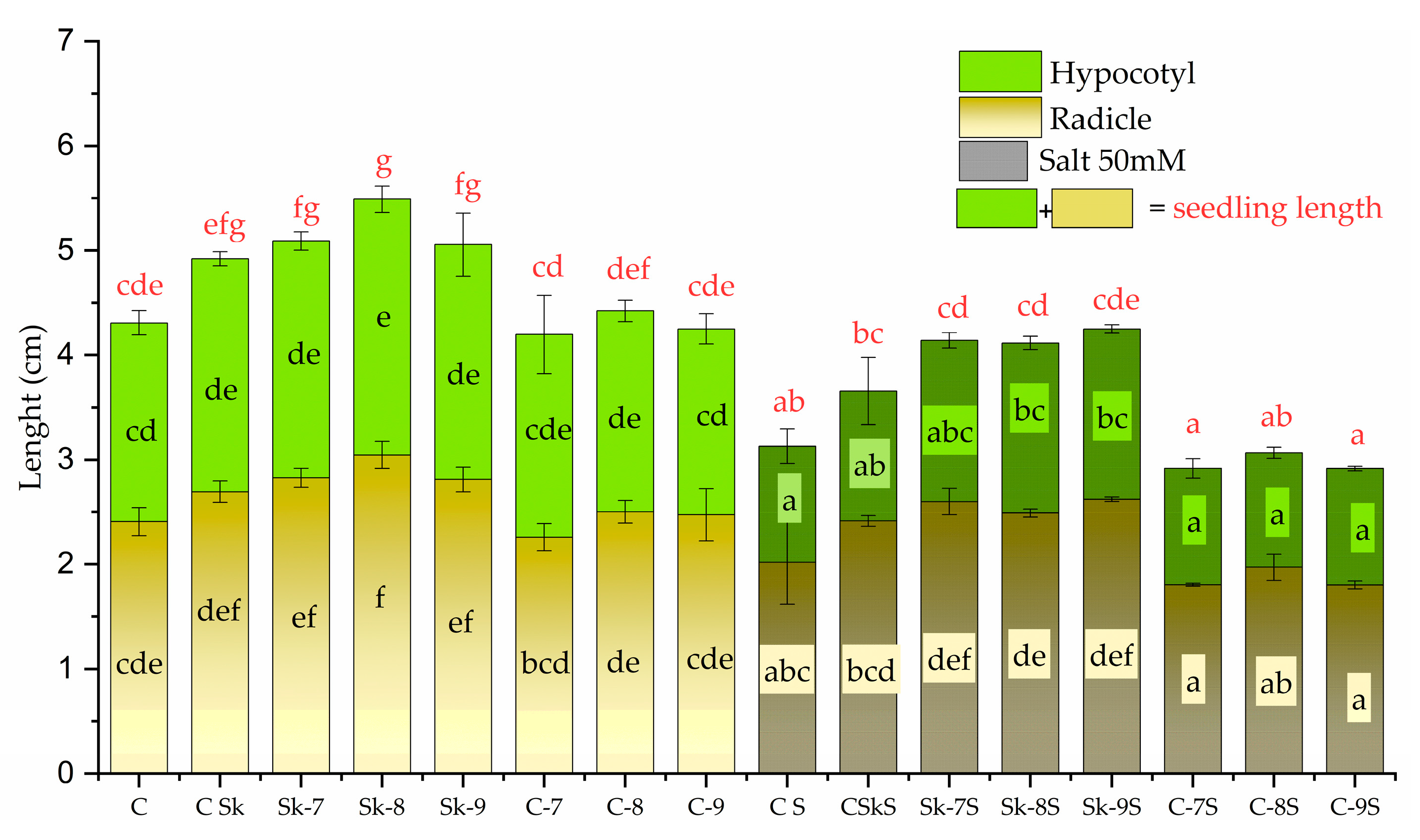

2.2.1. Effects on Seedlings Growth

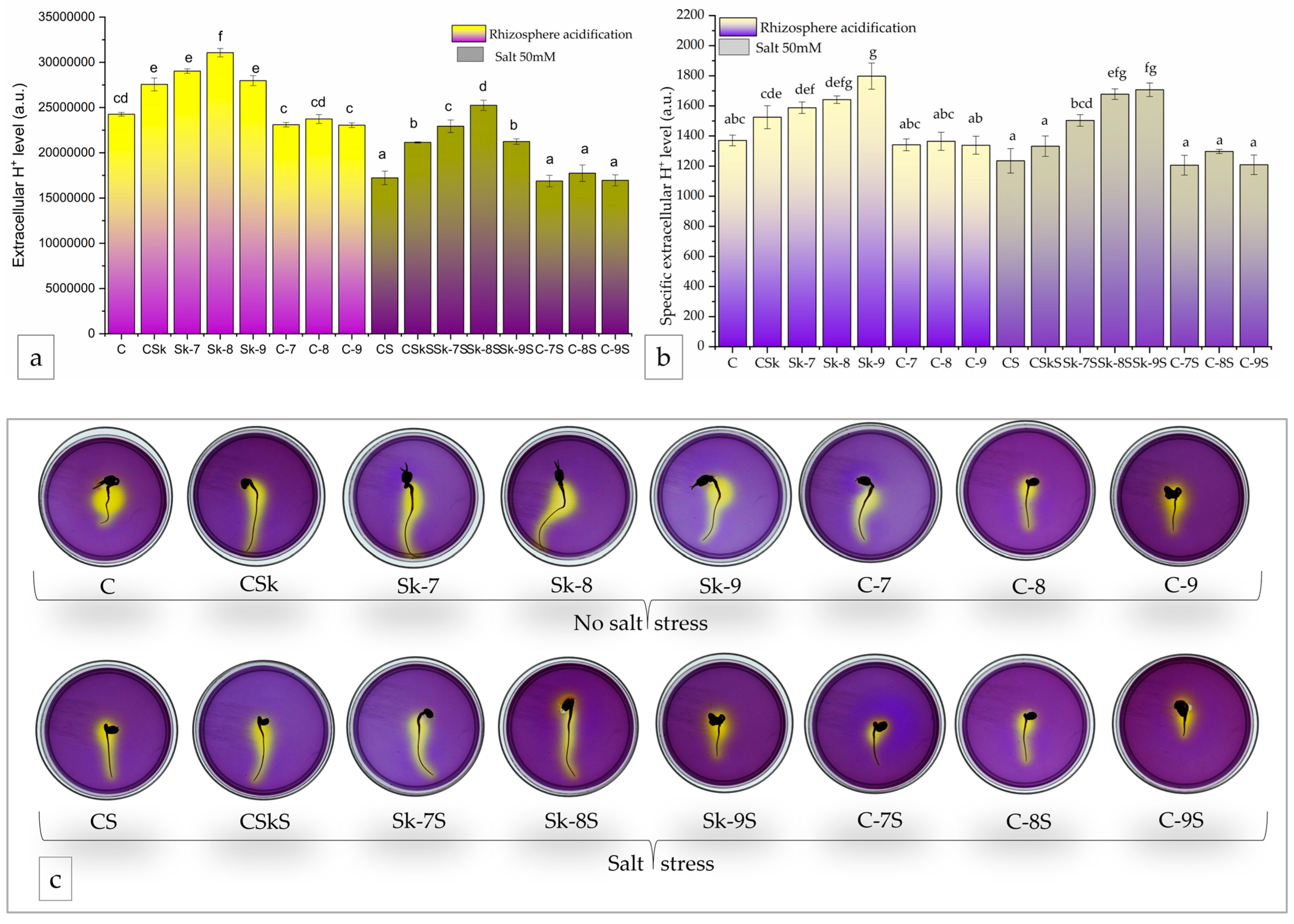

2.2.2. Acidification of the Growth Medium

3. Discussions

3.1. Lower Doses of Synthetic Strigolactones as Microalgal Biostimulant

3.2. Biostimulant Effects of Microalgal Extracts Towards Mung Seedlings

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Testing the Effect of SL-6 on Microalgal Growth

4.2.1. Microalgae Cultivation

4.2.2. Measurement of Growth Parameters

4.3. Preparation of Microalgal Biomass Extract

4.4. Plant Biostimulant Biotests on Seedlings

4.4.1. Mung Bean Seedling Measurement

4.4.2. Medium Acidification Assay

4.5. Statistical Analysis and Figure Design

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, C.; Tang, T.; Shi, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Fan, J. The potential and challenge of microalgae as promising future food sources. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2022, 126, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.; Ali, Z.; Yasin, M.T.; Amanat, K.; Sarwar, F.; Khan, J.; Ahmad, K. Advancements in sustainable production of biofuel by Microalgae: Recent insights and future directions. Environmental Research 2024, 262, 119902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, A.P.; Morais, R.C.; Teixeira, J.A.; Nunes, J. A comparison between microalgal autotrophic growth and metabolite accumulation with heterotrophic, mixotrophic and photoheterotrophic cultivation modes. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 159, 112247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velea, S.; Oancea, F.; Fischer, F. Heterotrophic and mixotrophic microalgae cultivation. Microalgae-based biofuels and bioproducts.

- Do, C.V.T.; Pham, M.H.T.; Pham, T.Y.T.; Dinh, C.T.; Bui, T.U.T.; Tran, T.D. Microalgae and bioremediation of domestic wastewater. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2022, 34, 100595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geremia, E.; Ripa, M.; Catone, C.M.; Ulgiati, S. A Review about Microalgae Wastewater Treatment for Bioremediation and Biomass Production—A New Challenge for Europe. Environments 2021, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Perumal, P.K.; Sumathi, Y.; Singhania, R.R.; Chen, C.-W.; Dong, C.-D.; Patel, A.K. Nano-Enabled Microalgae Bioremediation: Advances in Sustainable Pollutant Removal and Value-Addition. Environmental Research 2024, 263, 120011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigakis, N.C.; Nazos, T.T.; Chatzopoulou, M.; Mparka, N.; Spantidaki, M.; Lagouvardou-Spantidaki, A.; Ghanotakis, D.F. Cultivation of a naturally resilient Chlorella sp.: A bioenergetic strategy for valorization of cheese whey for high nutritional biomass production. Algal Research 2024, 82, 103616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, J.-M.; Roy, M.-L.; Hafsa, M.B.; Gagnon, J.; Faucheux, N.; Heitz, M.; Tremblay, R.; Deschênes, J.-S. Mixotrophic cultivation of green microalgae Scenedesmus obliquus on cheese whey permeate for biodiesel production. Algal Research 2014, 5, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, H.; Cereijo, C.R.; Teles, V.C.; Nascimento, R.C.; Fernandes, M.S.; Brunale, P.; Campanha, R.C.; Soares, I.P.; Silva, F.C.; Sabaini, P.S. Microalgae cultivation in sugarcane vinasse: Selection, growth and biochemical characterization. Bioresource Technology 2017, 228, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.; Melo, L.B.U.; Borrego, B.B.; Gracioso, L.H.; Perpetuo, E.A.; do Nascimento, C.A.O. Sugarcane vinasse as feedstock for microalgae cultivation: from wastewater treatment to bioproducts generation. Brazilian Journal of Chemical Engineering 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarponi, P.; Bravi, M.; Cavinato, C. Wine Lees as Alternative Substrate for Microalgae Cultivation: New Opportunity in Winery Waste Biorefinery Application. Waste 2023, 1, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastoras, P.; Zkeri, E.; Panara, A.; Dasenaki, M.E.; Maragou, N.C.; Vakalis, S.; Fountoulakis, M.S.; Thomaidis, N.S.; Stasinakis, A.S. Application of a pilot-scale solar still for wine lees management: Characterization of by-products and valorization potential. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2023, 11, 111227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Vaz, A.; León, R.; Díaz-Santos, E.; Vigara, J.; Raposo, S. Using agro-industrial wastes for mixotrophic growth and lipids production by the green microalga Chlorella sorokiniana. New biotechnology 2019, 51, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigbeder, J.-B.; Boboescu, I.-Z.; Lavoie, J.-M. Thin stillage treatment and co-production of bio-commodities through finely tuned Chlorella vulgaris cultivation. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 216, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miazek, K.; Remacle, C.; Richel, A.; Goffin, D. Effect of Lignocellulose Related Compounds on Microalgae Growth and Product Biosynthesis: A Review. Energies 2014, 7, 4446–4481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, J.W.R.; Khoo, K.S.; Yew, G.Y.; Leong, W.H.; Lim, J.W.; Lam, M.K.; Ho, Y.-C.; Ng, H.S.; Munawaroh, H.S.H.; Show, P.L. Advances in production of bioplastics by microalgae using food waste hydrolysate and wastewater: a review. Bioresource Technology 2021, 342, 125947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Xiao, M.; Liang, Q.; Ren, X.; Wang, Y.; Mou, H.; Sun, H. Realization process of microalgal biorefinery: The optional approach toward carbon net-zero emission. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 901, 165546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Castillo, G.A.; Navarro-Pineda, F.S.; Rodríguez, S.A.B.; Rivero, J.C.S. Advances on the processing of microalgal biomass for energy-driven biorefineries. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 125, 109606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyande, A.K.; Chew, K.W.; Rambabu, K.; Tao, Y.; Chu, D.-T.; Show, P.-L. Microalgae: A potential alternative to health supplementation for humans. Food Science and Human Wellness 2019, 8, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, B.d.S.; Moreira, J.B.; Morais, M.G.d.; Costa, J.A.V. Microalgae as a new source of bioactive compounds in food supplements. Current Opinion in Food Science 2016, 7, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaiese, P.; Corrado, G.; Colla, G.; Kyriacou, M.C.; Rouphael, Y. Renewable Sources of Plant Biostimulation: Microalgae as a Sustainable Means to Improve Crop Performance. Frontiers in Plant Science 2018, 9, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoore, R.V.; Wood, E.E.; Llewellyn, C.A. Algae biostimulants: A critical look at microalgal biostimulants for sustainable agricultural practices. Biotechnology Advances 2021, 49, 107754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chabili, A.; Minaoui, F.; Hakkoum, Z.; Douma, M.; Meddich, A.; Loudiki, M. A comprehensive review of microalgae and cyanobacteria-based biostimulants for agriculture uses. Plants 2024, 13, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EU. Regulation (EU) 2019/1009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 laying down rules on the making available on the market of EU fertilising products and amending Regulations (EC) No 1069/2009 and (EC) No 1107/2009 and repealing Regulation (EC) No 2003/2003. 2019/1009 2019.

- Mutale-Joan, C.; Redouane, B.; Najib, E.; Yassine, K.; Lyamlouli, K.; Laila, S.; Zeroual, Y.; Hicham, E.A. Screening of microalgae liquid extracts for their bio stimulant properties on plant growth, nutrient uptake and metabolite profile of Solanum lycopersicum L. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oancea, F.; Velea, S.; Mincea, C.; Ilie, L. Micro-algae based plant biostimulant and its effect on water stressed tomato plants. Romanian Journal of Plant Protection 2013, 6, 104–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kusvuran, S. Microalgae (Chlorella vulgaris Beijerinck) alleviates drought stress of broccoli plants by improving nutrient uptake, secondary metabolites, and antioxidative defense system. Horticultural Plant Journal 2021, 7, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Park, Y.J.; Choi, Y.B.; Truong, T.Q.; Huynh, P.K.; Kim, Y.B.; Kim, S.M. Physiological Effects and Mechanisms of Chlorella vulgaris as a Biostimulant on the Growth and Drought Tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plants 2024, 13, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglisi, I.; La Bella, E.; Rovetto, E.I.; Lo Piero, A.R.; Baglieri, A. Biostimulant Effect and Biochemical Response in Lettuce Seedlings Treated with A Scenedesmus quadricauda Extract. Plants 2020, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chovanček, E.; Salazar, J.; Şirin, S.; Allahverdiyeva, Y. Microalgae from Nordic collections demonstrate biostimulant effect by enhancing plant growth and photosynthetic performance. Physiologia Plantarum 2023, 175, e13911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brück, W.M.; Alfonso, E.; Rienth, M.; Andlauer, W. Heat Stress Resistance in Chlorella vulgaris Enhanced by Hydrolyzed Whey Proteins. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.K.; Hu, R.; Wong, M.H.; Cheung, K.C. Comparative toxicity of hydrophobic contaminants to microalgae and higher plants. Ecotoxicology 2007, 16, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, C.; Whichard, L.P.; Turner, B.; Wall, M.E.; Egley, G.H. Germination of witchweed (Striga lutea Lour.): isolation and properties of a potent stimulant. Science 1966, 154, 1189–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoneyama, K.; Xie, X.; Yoneyama, K.; Takeuchi, Y. Strigolactones: structures and biological activities. Pest Management Science 2009, 65, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoneyama, K.; Xie, X.; Yoneyama, K.; Kisugi, T.; Nomura, T.; Nakatani, Y.; Akiyama, K.; McErlean, C.S. Which are the major players, canonical or non-canonical strigolactones? Journal of experimental botany 2018, 69, 2231–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalid, M.F.; Shafqat, W.; Khan, R.I.; Jawaid, M.Z.; Hussain, S.; Saqib, M.; Rizwan, M.; Ahmed, T. Unveiling the resilience mechanism: Strigolactones as master regulators of plant responses to abiotic stresses. Plant Stress 2024, 12, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Mao, Y.; Cui, J.; Lu, X.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, H.; Yu, W.; Li, C. The role of strigolactones in resistance to environmental stress in plants. Physiologia Plantarum 2024, 176, e14419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, F.; Fichtner, F.; Beveridge, C. The strigolactone pathway plays a crucial role in integrating metabolic and nutritional signals in plants. Nature Plants 2023, 9, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daignan-Fornier, S.; Keita, A.; Boyer, F.-D. Chemistry of Strigolactones, Key Players in Plant Communication. ChemBioChem 2024, 25, e202400133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.; Bennett, T. Cracking the enigma: understanding strigolactone signalling in the rhizosphere. Journal of Experimental Botany 2024, 75, 1159–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwanenburg, B.; Ćavar Zeljković, S.; Pospíšil, T. Synthesis of strigolactones, a strategic account. Pest Management Science 2016, 72, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangnus, E.M.; Dommerholt, F.J.; De Jong, R.L.P.; Zwanenburg, B. Improved synthesis of strigol analog GR24 and evaluation of the biological activity of its diastereomers. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 1992, 40, 1230–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Z.; Li, R.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, M.; Ju, Y.; Fang, Y. Alleviation of drought stress in grapevine by foliar-applied strigolactones. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2019, 135, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iftikhar, I.; Shahbaz, M.; Maqsood, M.F.; Zulfiqar, U.; Rana, S.; Farhat, F.; Farooq, H.; Ahmad, K.; Jamil, M.; Haider, F.U.; et al. Resilient mechanism of strigolactone (GR24) in regulating morphological and biochemical status of maize under salt stress. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2024, 60, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoarelojie, L.O.; Kulkarni, M.G.; Finnie, J.F.; Pospíšil, T.; Strnad, M.; Van Staden, J. Synthetic strigolactone (rac-GR24) alleviates the adverse effects of heat stress on seed germination and photosystem II function in lupine seedlings. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2020, 155, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tang, C.; Xie, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C. Exogenous strigolactones alleviate low-temperature stress in peppers seedlings by reducing the degree of photoinhibition. BMC Plant Biology 2024, 24, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, K.I.; Naeem, M.; Khan, M.M.A.; Aftab, T. Insights into strigolactone (GR24) mediated regulation of cadmium-induced changes and ROS metabolism in Artemisia annua. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 448, 130899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, D.; Panneerselvam, P.; Chidambaranathan, P.; Nayak, A.K.; Priyadarshini, A.; Senapati, A.; Mohapatra, P.K.D. Strigolactone GR24-mediated mitigation of phosphorus deficiency through mycorrhization in aerobic rice. Current Research in Microbial Sciences 2024, 6, 100229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, K.I.; Zehra, A.; Choudhary, S.; Naeem, M.; Khan, M.M.A.; Khan, R.; Aftab, T. Exogenous Strigolactone (GR24) Positively Regulates Growth, Photosynthesis, and Improves Glandular Trichome Attributes for Enhanced Artemisinin Production in Artemisia annua. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 2023, 42, 4606–4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lu, X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Yu, W. Strigolactone Alleviates the Adverse Effects of Salt Stress on Seed Germination in Cucumber by Enhancing Antioxidant Capacity. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Ma, C.; Su, M.; Wang, J.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, T. Exogenous strigolactones alleviate the photosynthetic inhibition and oxidative damage of cucumber seedlings under salt stress. Scientia Horticulturae 2022, 297, 110962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaux, P.-M.; Xie, X.; Timme, R.E.; Puech-Pages, V.; Dunand, C.; Lecompte, E.; Delwiche, C.F.; Yoneyama, K.; Bécard, G.; Séjalon-Delmas, N. Origin of strigolactones in the green lineage. New Phytologist 2012, 195, 857–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Z. Supplementation of 5-deoxystrigol for higher pollutant removal and biogas quality improvement by different microalgae-based technologies. Water Environment Research 2023, 95, e10895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Xue, Z.; Sun, L.; Zhao, C.; Sun, S.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J. Effect of GR24 concentrations on biogas upgrade and nutrient removal by microalgae-based technology. Bioresource Technology 2020, 312, 123563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popa, D.G.; Lupu, C.; Constantinescu-Aruxandei, D.; Oancea, F. Humic Substances as Microalgal Biostimulants—Implications for Microalgal Biotechnology. Marine Drugs 2022, 20, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglisi, I.; Barone, V.; Sidella, S.; Coppa, M.; Broccanello, C.; Gennari, M.; Baglieri, A. Biostimulant activity of humic-like substances from agro-industrial waste on Chlorella vulgaris and Scenedesmus quadricauda. European Journal of Phycology 2018, 53, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraon, V.A.; Popa, D.G.; Tudor-Popa, I.; Mihăilă, E.G.; Oancea, F. Effect of Humic Acids from Biomass Biostimulant on Microalgae Growth. Chemistry Proceedings 2022, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suparmaniam, U.; Lam, M.K.; Lim, J.W.; Rawindran, H.; Chai, Y.H.; Tan, I.S.; Fui Chin, B.L.; Kiew, P.L. The potential of waste chicken feather protein hydrolysate as microalgae biostimulant using organic fertilizer as nutrients source. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2022, 1074, 012028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, D.G.; Georgescu, F.; Dumitrascu, F.; Shova, S.; Constantinescu-Aruxandei, D.; Draghici, C.; Vladulescu, L.; Oancea, F. Novel Strigolactone Mimics That Modulate Photosynthesis and Biomass Accumulation in Chlorella sorokiniana. Molecules 2023, 28, 7059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oancea, F.; Georgescu, E.; Matusova, R.; Georgescu, F.; Nicolescu, A.; Raut, I.; Jecu, M.-L.; Vladulescu, M.-C.; Vladulescu, L.; Deleanu, C. New Strigolactone Mimics as Exogenous Signals for Rhizosphere Organisms. Molecules 2017, 22, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, I.; Airinei, A.; Georgescu, E.; Oancea, F.; Georgescu, F.; Nicolescu, A.; Tigoianu, R.; Deleanu, C. Photophysical and biological properties of a strigolactone mimic derived from 1, 8-naphthalic anhydride. Revue Roumaine de Chimie 2022, 67, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.J.; Gomes, T.; Almeida, A.C.; Christou, M.; Zheng, C.; Shaposhnikov, S.; Popa, D.G.; Georgescu, F.; Oancea, F. An ecotoxicological assessment of a strigolactone mimic used as the active ingredient in a plant biostimulant formulation. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2024, 275, 116244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, C.; Sun, S.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J. Performance of different microalgae-based technologies in nutrient removal and biogas upgrading in response to various GR24 concentrations. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation 2021, 158, 105166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltsev, Y.; Maltseva, K.; Kulikovskiy, M.; Maltseva, S. Influence of Light Conditions on Microalgae Growth and Content of Lipids, Carotenoids, and Fatty Acid Composition. Biology 2021, 10, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, T.; Han, B.; Zhao, P.; Xu, J.-W.; Yu, X. Enhancement of lipid accumulation in Monoraphidium sp. QLY-1 by induction of strigolactone. Bioresource Technology 2019, 288, 121607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez-Arjona, F.M.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, C.; Montesinos, J.C. The root apoplastic pH as an integrator of plant signaling. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Ding, M.; Xu, F.; Yan, F.; Kinoshita, T.; Zhu, Y. Plasma membrane H+-ATPases in mineral nutrition and crop improvement. Trends in Plant Science 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Yu, H.; Li, Q.; Chai, L.; Jiang, W. Improving Plant Growth and Alleviating Photosynthetic Inhibition and Oxidative Stress From Low-Light Stress With Exogenous GR24 in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Seedlings. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Wang, R.; Liu, B.; Zhu, T.; Li, H.; Long, S.; Liu, T.; Xu, Y. Regulatory mechanism of strigolactone in tall fescue to low-light stress. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2024, 215, 109054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zeng, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Xia, A.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q. Revealing the synergistic effects of cells, pigments, and light spectra on light transfer during microalgae growth: A comprehensive light attenuation model. Bioresource Technology 2022, 348, 126777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wágner, D.S.; Valverde-Pérez, B.; Plósz, B.G. Light attenuation in photobioreactors and algal pigmentation under different growth conditions – Model identification and complexity assessment. Algal Research 2018, 35, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serôdio, J.; Campbell, D.A. Photoinhibition in optically thick samples: Effects of light attenuation on chlorophyll fluorescence-based parameters. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2021, 513, 110580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Ghosh, S.; Fixler, D.; Dubinsky, Z.; Iluz, D. Flashing light in microalgae biotechnology. Bioresource Technology 2016, 203, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzobon, V. Chlorella vulgaris cultivation under super high light intensity: An application of the flashing light effect. Algal Research 2022, 68, 102874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khopkar, A.; Mahulkar, A.; Rajpoot, S.; Sapre, A. Identifying Opportunities for Improving the Light Utilization Efficiency of Microalgae in a Flashing Light Regime. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2023, 62, 19035–19042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, M.S.; Loures, C.C.A.; Naves, F.L.; Baeta, B.E.L.; Silva, M.B.; Prata, A.M.R. Evaluation of cell growth performance of microalgae Chlorella minutissima using an internal light integrated photobioreactor. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2020, 8, 104200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gong, P.; Cai, Q.; Zhang, C.; Gao, B. Maximizing fucoxanthin production in Odontella aurita by optimizing the ratio of red and blue light-emitting diodes in an auto-controlled internally illuminated photobioreactor. Bioresource Technology 2022, 344, 126260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahangar, A.K.; Yaqoubnejad, P.; Divsalar, K.; Mousavi, S.; Taghavijeloudar, M. Design a novel internally illuminated mirror photobioreactor to improve microalgae production through homogeneous light distribution. Bioresource Technology 2023, 387, 129577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.H.; Lee, Y.; Jeon, D.Y.; Han, J.-I. Enhancing the light utilization efficiency of microalgae using organic dyes. Bioresource Technology 2015, 181, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, Y.; Miao, X. Quantum dot-based light conversion strategy for customized cultivation of microalgae. Bioresource Technology 2024, 397, 130489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malapascua, J.; Ranglová, K.; Masojídek, J. Photosynthesis and growth kinetics of Chlorella vulgaris R-117 cultured in an internally LED-illuminated photobioreactor. Photosynthetica 2019, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, W.; Taidi, B.; Lacombe, R.; Perré, P.; Pozzobon, V. Impact of seconds to minutes photoperiods on Chlorella vulgaris growth rate and chlorophyll a and b content. Algal Research 2018, 36, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, R.; Latowski, D. Lipid Dependence of Xanthophyll Cycling in Higher Plants and Algae. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girolomoni, L.; Bellamoli, F.; de la Cruz Valbuena, G.; Perozeni, F.; D'Andrea, C.; Cerullo, G.; Cazzaniga, S.; Ballottari, M. Evolutionary divergence of photoprotection in the green algal lineage: a plant-like violaxanthin de-epoxidase enzyme activates the xanthophyll cycle in the green alga Chlorella vulgaris modulating photoprotection. New Phytologist 2020, 228, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guardini, Z.; Dall’Osto, L.; Barera, S.; Jaberi, M.; Cazzaniga, S.; Vitulo, N.; Bassi, R. High Carotenoid Mutants of Chlorella vulgaris Show Enhanced Biomass Yield under High Irradiance. Plants 2021, 10, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerchev, P.; van der Meer, T.; Sujeeth, N.; Verlee, A.; Stevens, C.V.; Van Breusegem, F.; Gechev, T. Molecular priming as an approach to induce tolerance against abiotic and oxidative stresses in crop plants. Biotechnology Advances 2020, 40, 107503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoarelojie, L.O.; Kulkarni, M.G.; Finnie, J.F.; van Staden, J. Biostimulants and the modulation of plant antioxidant systems and properties. In Biostimulants for Crops from Seed Germination to Plant Development, Gupta, S., Van Staden, J., Eds.; Academic Press: 2021; pp. 333–363.

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Parvin, K.; Bardhan, K.; Nahar, K.; Anee, T.I.; Masud, A.A.C.; Fotopoulos, V. Biostimulants for the Regulation of Reactive Oxygen Species Metabolism in Plants under Abiotic Stress. Cells 2021, 10, 2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Mou, J.-H.; Qin, Z.-H.; Hao, T.-B.; Zheng, L.; Buhagiar, J.; Liu, Y.-H.; Balamurugan, S.; He, Y.; Lin, C.S.K.; et al. Supplementation with rac-GR24 Facilitates the Accumulation of Biomass and Astaxanthin in Two Successive Stages of Haematococcus pluvialis Cultivation. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2022, 70, 4677–4689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürger, M.; Chory, J. The Many Models of Strigolactone Signaling. Trends in Plant Science 2020, 25, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbert, Z. Strigolactone-nitric oxide interplay in plants: The story has just begun. Physiologia Plantarum 2019, 165, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelo, D.M.; Annamaria, V.; Christophe, B.; Clementina, S. Bioprospecting of phytohormone biosynthetic pathways in the microalgal realm. Algal Research 2023, 76, 103307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motohashi, K.; Takagi, M.; Yamamura, H.; Hayakawa, M.; Shin-ya, K. A new angucycline and a new butenolide isolated from lichen-derived Streptomyces spp. The Journal of Antibiotics 2010, 63, 545–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallet, M.; Chong, Y.-M.; Tourneroche, A.; Genta-Jouve, G.; Hubas, C.; Lami, R.; Gachon, C.M.M.; Klochkova, T.; Chan, K.-G.; Prado, S. Novel α-Hydroxy γ-Butenolides of Kelp Endophytes Disrupt Bacterial Cell-to-Cell Signaling. Frontiers in Marine Science 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Li, J.; Xu, J.; Zheng, Z. Nutrient removal and biogas upgrade using co-cultivation of Chlorella vulgaris and three different bacteria under various GR24 concentrations by induction with 5-deoxystrigol. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2023, 39, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Xue, Z.; Liu, J.; Sun, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H. Observation of few GR24 induced fungal-microalgal pellets performance for higher pollutants removal and biogas quality improvement. Energy 2022, 244, 123171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Yang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, C.; Lu, B.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y. The effects of influent 5-Deoxystrigol concentrations on integral biogas upgrading and nutrient removal by different algal-fungal-bacterial consortium. Algal Research 2024, 84, 103770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proust, H.; Hoffmann, B.; Xie, X.; Yoneyama, K.; Schaefer, D.G.; Yoneyama, K.; Nogué, F.; Rameau, C. Strigolactones regulate protonema branching and act as a quorum sensing-like signal in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Development 2011, 138, 1531–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeldon, C.D.; Hamon-Josse, M.; Lund, H.; Yoneyama, K.; Bennett, T. Environmental strigolactone drives early growth responses to neighboring plants and soil volume in pea. Current Biology 2022, 32, 3593–3600.e3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peláez-Vico, M.A.; Bernabéu-Roda, L.; Kohlen, W.; Soto, M.J.; López-Ráez, J.A. Strigolactones in the Rhizobium-legume symbiosis: Stimulatory effect on bacterial surface motility and down-regulation of their levels in nodulated plants. Plant Science 2016, 245, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozes, C.; Meijler, M.M. Modulation of Bacterial Quorum Sensing by Strigolactones. ACS Chemical Biology 2020, 15, 2055–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruzzo, C.; Vezzulli, L.; Colwell, R.R. Global impact of Vibrio cholerae interactions with chitin. Environmental Microbiology 2008, 10, 1400–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, M.; Ali, M.M.A. Enhancement of microalgal biomass, lipid production and biodiesel characteristics by mixotrophic cultivation using enzymatically hydrolyzed chitin waste. Biomass and Bioenergy 2021, 154, 106251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colla, G.; Rouphael, Y. Microalgae: New Source of Plant Biostimulants. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, A.M.; Hernandez-Tenorio, F.; Villalta, F.; Vargas, G.J.; Sáez, A.A. Advances in the Development of Biofertilizers and Biostimulants from Microalgae. Biology 2024, 13, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Arroussi, H.; Elbaouchi, A.; Benhima, R.; Bendaou, N.; Smouni, A.; Wahby, I. Halophilic microalgae Dunaliella salina extracts improve seed germination and seedling growth of Triticum aestivum L. under salt stress. 2016; pp. 13–26.

- Guzmán-Murillo, M.A.; Ascencio, F.; Larrinaga-Mayoral, J.A. Germination and ROS detoxification in bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) under NaCl stress and treatment with microalgae extracts. Protoplasma 2013, 250, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezamdoost, D.; Ghahremani, Z.; Ranjbar, M.E. Seed priming with Chlorella vulgaris extract increases salt tolerance threshold of leafy lettuce more than two times based on germination indices (a modeling approach). Journal of Applied Phycology 2024, 36, 1247–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarsekeyeva, F.K.; Sadvakasova, A.K.; Sandybayeva, S.K.; Kossalbayev, B.D.; Huang, Z.; Zayadan, B.K.; Akmukhanova, N.R.; Leong, Y.K.; Chang, J.-S.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Microalgae- and cyanobacteria-derived phytostimulants for mitigation of salt stress and improved agriculture. Algal Research 2024, 82, 103686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Ding, M.; Xu, F.; Yan, F.; Kinoshita, T.; Zhu, Y. Plasma membrane H+-ATPases in mineral nutrition and crop improvement. Trends in Plant Science 2024, 29, 978–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandonadi, D.B.; Santos, M.P.; Caixeta, L.S.; Marinho, E.B.; Peres, L.E.P.; Façanha, A.R. Plant proton pumps as markers of biostimulant action. Scientia Agricola 2016, 73, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, B.; Maddela, N.R.; Venkateswarlu, K.; Megharaj, M. Potential of microalgae and cyanobacteria to improve soil health and agricultural productivity: a critical view. Environmental Science: Advances 2023, 2, 586–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-M.; Ryu, C.-M. Algae as New Kids in the Beneficial Plant Microbiome. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.; Freitas, J.; Fernandes, I.; Silva, P. Microalgae as Biofertilizers: A Sustainable Way to Improve Soil Fertility and Plant Growth. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigner, S.; Glaser, K.; Arc, E.; Holzinger, A.; Schletter, M.; Karsten, U.; Kranner, I. Adaptation to Aquatic and Terrestrial Environments in Chlorella vulgaris (Chlorophyta). Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholssi, R.; Marks, E.A.N.; Miñón, J.; Montero, O.; Debdoubi, A.; Rad, C. Biofertilizing Effect of Chlorella sorokiniana Suspensions on Wheat Growth. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 2019, 38, 644–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chader, S.; Mahmah, B.; Chetehouna, K.; Amrouche, F.; Abdeladim, K. Biohydrogen production using green microalgae as an approach to operate a small proton exchange membrane fuel cell. international journal of hydrogen energy 2011, 36, 4089–4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaoui, F.; Hakkoum, Z.; Chabili, A.; Douma, M.; Mouhri, K.; Loudiki, M. Biostimulant effect of green soil microalgae Chlorella vulgaris suspensions on germination and growth of wheat (Triticum aestivum var. Achtar) and soil fertility. Algal Research 2024, 82, 103655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Ráez, J.A.; Pozo, M.J.; García-Garrido, J.M. Strigolactones: a cry for help in the rhizosphere. Botany 2011, 89, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, F.; Shi, S.; Tian, L.; Chang, C.; Ma, L.; Li, X.; Gao, Y.; Tian, C. Strigolactones shape the rhizomicrobiome in rice (Oryza sativa). Plant Science 2019, 286, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Huang, P.; Yu, H.; Yu, H.; Xie, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, M.; Yao, R. Strigolactones shape the assembly of root-associated microbiota in response to phosphorus availability. mSystems 2024, 9, e01124–e01123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, S.; Wang, Y.; Han, Z.; Pervaiz, T.; El-kereamy, A. Strigolactones in Plants and Their Interaction with the Ecological Microbiome in Response to Abiotic Stress. Plants 2022, 11, 3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Ráez, J.A. How drought and salinity affect arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis and strigolactone biosynthesis? Planta 2016, 243, 1375–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisabeth, B.; Rayen, F.; Behnam, T. Microalgae culture quality indicators: a review. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2021, 41, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bala, I.; Airinei, A.; Georgescu, E.; Oancea, F.; Georgescu, F.; Nicolescu, A.; Tigoianu, R.; Deleanu, C. Photophysical and biological properties of a strigolactone mimic derived from 1,8-naphthalic anhydride. Rev Roum Chim 2022, 67, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.S.; Park, W.-K.; Lee, B.; Seon, G.; Suh, W.I.; Moon, M.; Chang, Y.K. Optimization of heterotrophic cultivation of Chlorella sp. HS2 using screening, statistical assessment, and validation. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 19383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MJ, G.; C, G.; RP, v.H.; ST, H. Interference by pigment in the estimation of microalgal biomass concentration by optical density. Journal of microbiological methods 2011, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, S.; Shi, J.; Huang, T.; Guo, Y.; Wei, J.; Guo, M.; Li, L.; Dou, S.; Liu, L.; Liu, G. Characterization of Chlorella sorokiniana growth properties in monosaccharide-supplemented batch culture. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0199873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, B.-H.; Choi, J.-A.; Kim, H.-C.; Hwang, J.-H.; Abou-Shanab, R.A.; Dempsey, B.A.; Regan, J.M.; Kim, J.R. Ultrasonic disintegration of microalgal biomass and consequent improvement of bioaccessibility/bioavailability in microbial fermentation. Biotechnology for Biofuels 2013, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, G.S.; Diaz, A.; Bregoff, H.A. Seed Disinfestation Practices to Control Seed-Borne Fungi and Bacteria in Home Production of Sprouts. Foods 2023, 12, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritean, N.; Trică, B.; Dima, Ş.-O.; Capră, L.; Gabor, R.-A.; Cimpean, A.; Oancea, F.; Constantinescu-Aruxandei, D. Mechanistic insights into the plant biostimulant activity of a novel formulation based on rice husk nanobiosilica embedded in a seed coating alginate film. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).