Submitted:

31 July 2024

Posted:

02 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Algae Strains Cultivation

2.2. Anaerobic Digestion Effluent Collection and Processing

2.3. Species Cultivation

2.4. Microalgae Pre-treatment for Composition Analysis

2.5. Analytical Measurements

2.5.1. Growth Determination and Nutrient Analysis

2.5.2. Lipids Determination

2.5.3. Proteins Determination

2.5.4. Carbohydrates Determination

3. Results

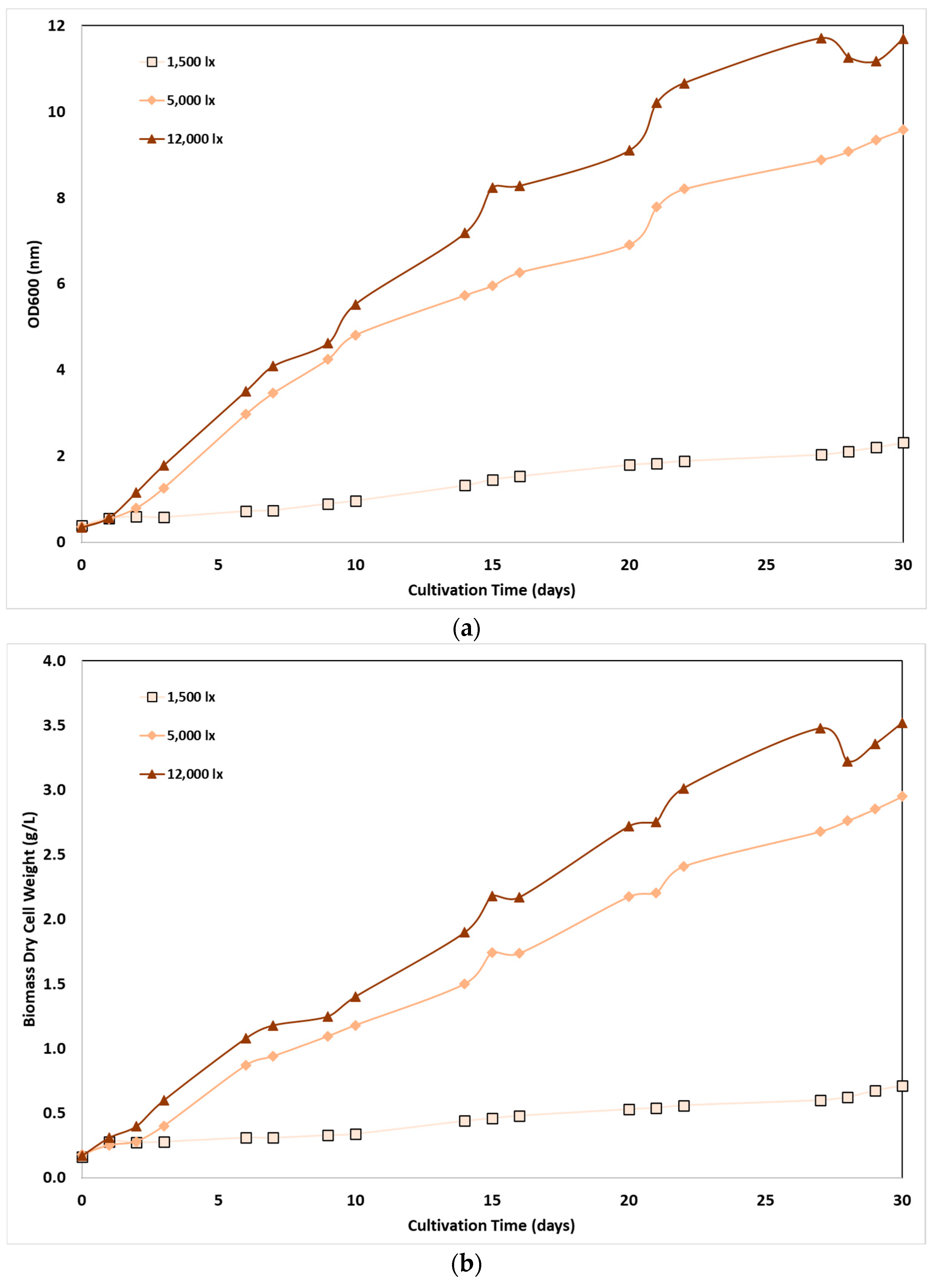

3.1. Effect of Light Intensity on Chlorella sorokiniana Growth

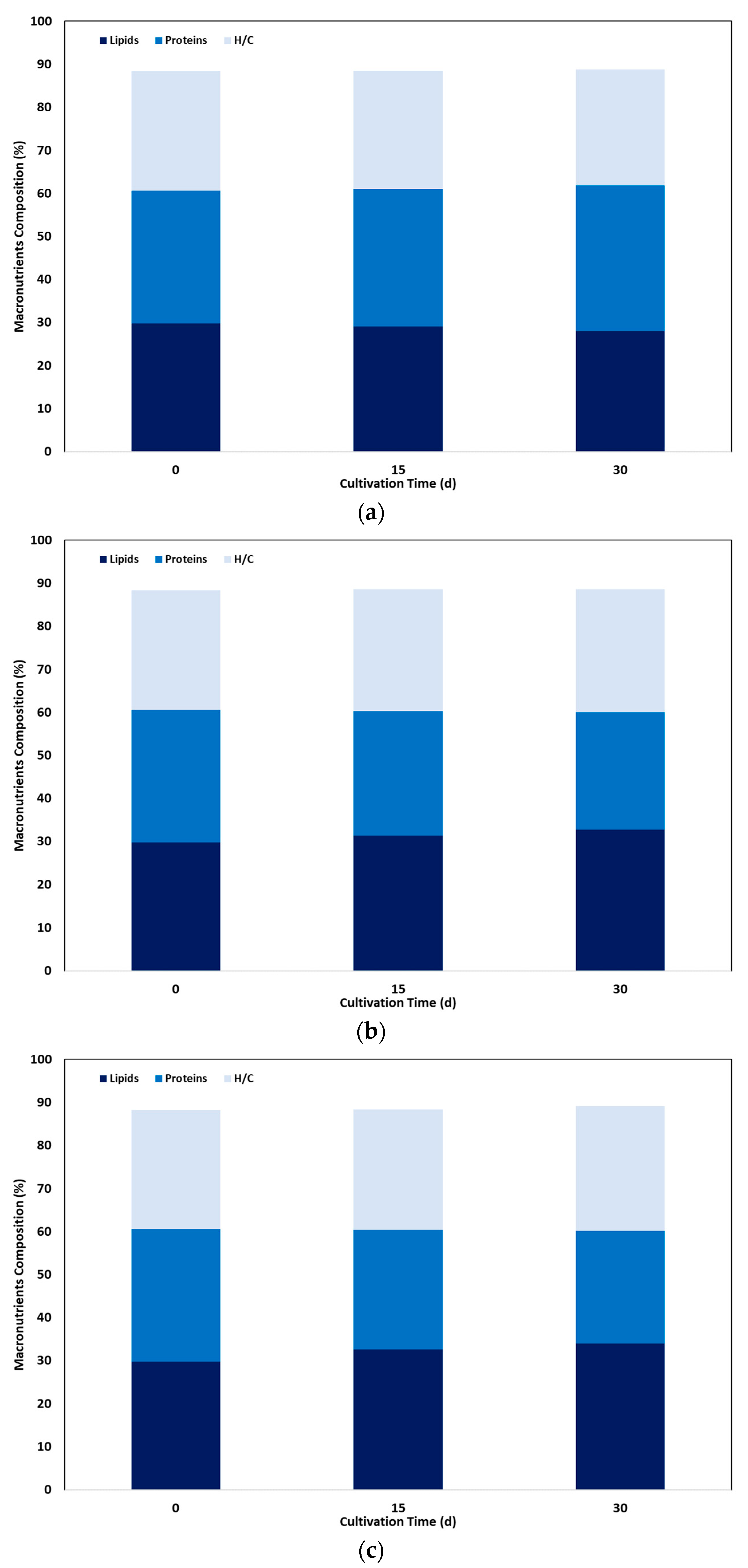

3.2. Effect of Light Intensity in the Macronutrient Concentration of Biomass

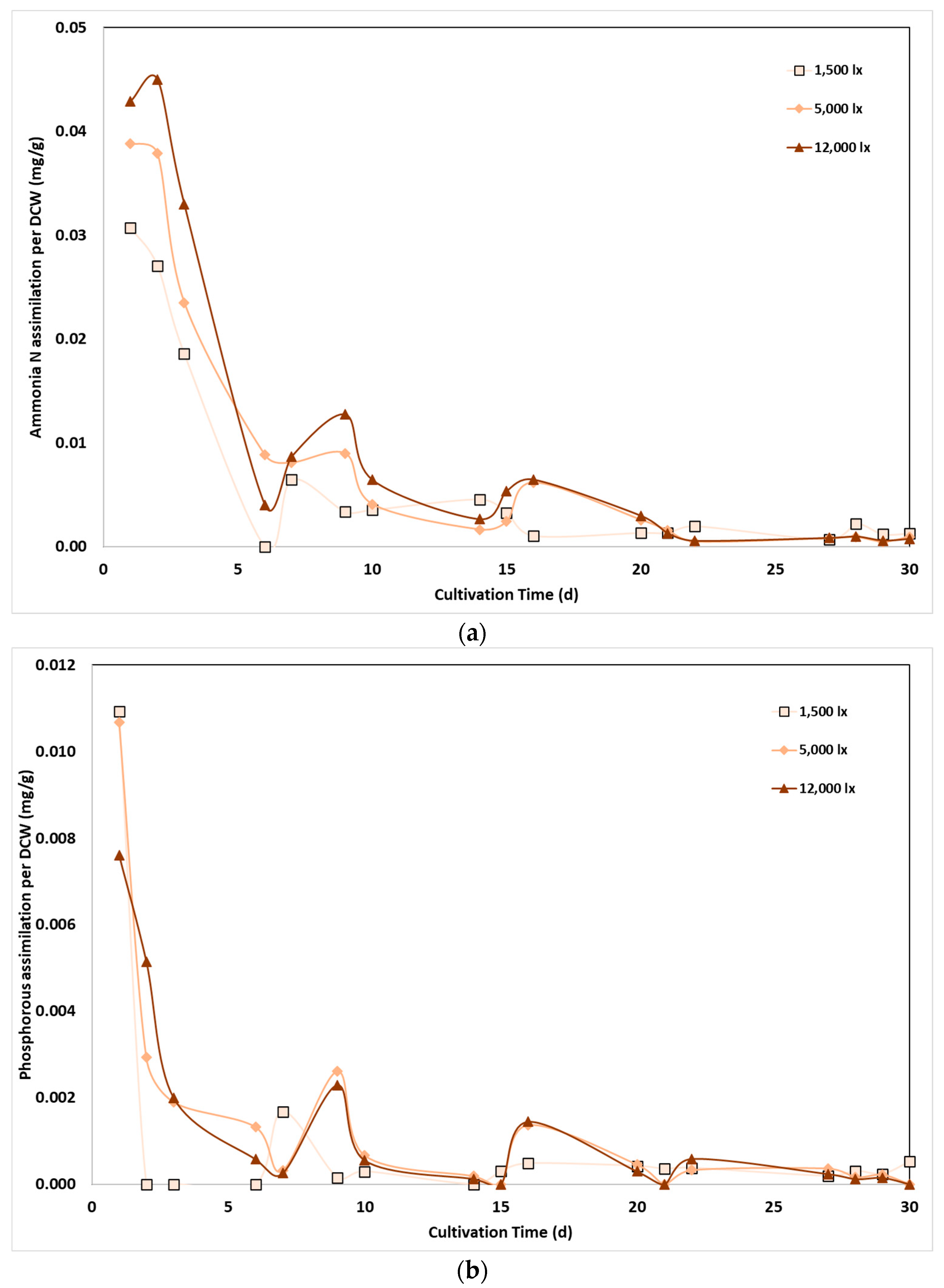

3.3. Effect of Light Intensity the Nutrients Removal

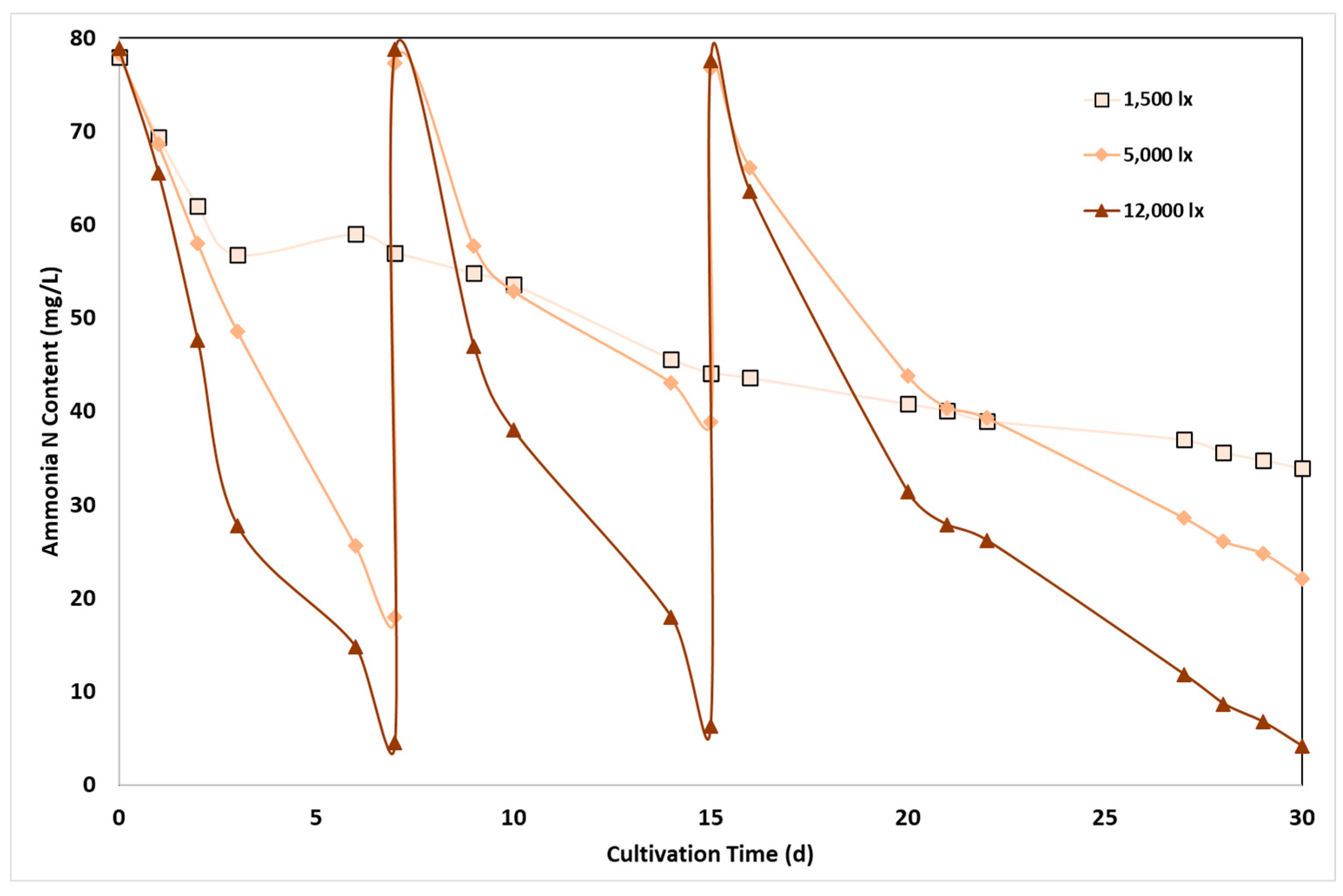

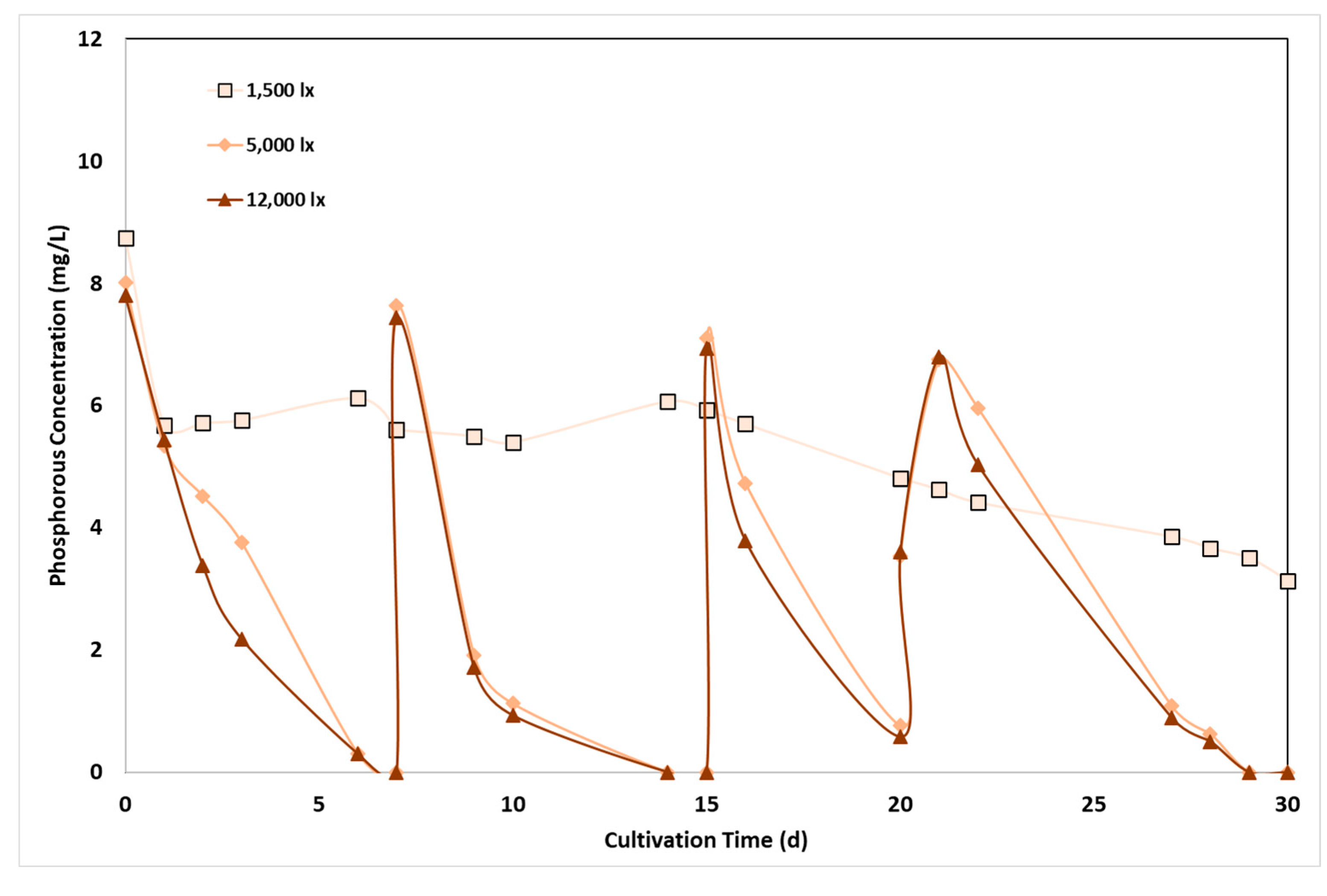

4. Conclusions

References

- Martinez-Porchas, M.; Martinez-Cordova, L.R.; Lopez-Elias, J.A.; Porchas-Cornejo, M.A. Bioremediation of aquaculture effluents. In Microbial biodegradation and bioremediation: Techniques and Case Studies for Environmental Pollution, 2nd ed.; Das, S., Dash, H.R. Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2021; pp. 539-553.

- Vale, A.M.; Ferreira, A.; Pires, C.M.J.; Goncalves, LA. (2020). CO2 Capture Using Microalge. In: Advances in Carbon Capture: Methods, Technology and Applications, Rahimpour, M.R., Farsi, Μ., Makarem, Μ.A. Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2020; pp. 308-405.

- Yun, H.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Yoon, H.S. Characterization of Chlorella sorokiniana and Chlorella vulgaris fatty acid components under a wide range of light intensity and growth temperature for their use as biological resources. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04447. [CrossRef]

- Khavari, F.; Saidijam, M.; Taheri, M.; Nouri, F. (2021). Microalgae: Therapeutic potentials and applications. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 4757-4765. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.M.; Ren, L.J.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Ji, X.J.; Huang, H. Microalgae for the production of lipid and carotenoids: a review with focus on stress regulation and adaptation. Biotechnol Biofuels 2018, 11, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Chowdury, K.H.; Nahar, N.; Deb, U.K. (2020). The growth factors involved in microalgae cultivation for biofuel production: a review. CWEEE 2020, 9, 185-215. [CrossRef]

- Goh, P.S.; Ahmad, N.A.; Lim, J.W.; Liang, Y.Y.; Kang, H.S.; Ismail, A.F.; Arthanareeswaran, G. Microalgae-Enabled Wastewater Remediation and Nutrient Recovery through Membrane Photobioreactors: Recent Achievements and Future Perspective. Membranes 2022, 12, 1094. [CrossRef]

- Obaideen, K.; Shehata, N.; Sayed, E.T.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Mahmoud, M.S.; Olabi, A.G. The role of wastewater treatment in achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs) and sustainability guideline. Energy Nexus 2022, 7, 100112. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Karim, O.H.; Gheda, S.F.; Ismail, G.A.; Abo-Shady, A.M. Phytochemical Screening and antioxidant activity of Chlorella vulgaris. DJS 2020, 41, 79-91. [CrossRef]

- Krzemińska, I.; Piasecka, A.; Nosalewicz, A.; Simionato, D.; Wawrzykowski, J. Alterations of the lipid content and fatty acid profile of Chlorella protothecoides under different light intensities. Bioresour. Τechnol. 2015, 196, 72-77. [CrossRef]

- Matabanchoy-Mesias, Y.; Rodríguez-Caicedo, Y.A.; Imués-Figueroa, M.A. Population growth of Chlorella sp. in three types of tubular photobioreactors, under laboratory conditions. AACL 2020, 13, 2094-2106.

- Kuo, C.M.; Sun, Y.L.; Lin, C.H.; Lin, C.H.; Wu, H.T.; Lin, C.S. Cultivation and biorefinery of microalgae (Chlorella sp.) for producing biofuels and other byproducts: A review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13480. [CrossRef]

- Narala, R.R.; Garg, S.; Sharma, K.K.; Thomas-Hall, S.R.; Deme, M.; Li, Y.; Schenk, P.M. Comparison of microalgae cultivation in photobioreactor, open raceway pond, and a two-stage hybrid system. Front. Energy Res. 2016, 4, 29. [CrossRef]

- Daliry, S.; Hallajisani, A.; Mohammadi Roshandeh, J.; Nouri, H.; Golzary, A. Investigation of optimal condition for Chlorella vulgaris microalgae growth. Global J. Environ. Sci. Mnage. 2017, 3, 217-230. [CrossRef]

- Lakaniemi, A.M.; Tuovinen, O.H.; Puhakka, J.A. Anaerobic conversion of microalgal biomass to sustainable energy carriers–a review. Bioresour. Τechnol. 2013, 135, 222-231. [CrossRef]

- Binnal, P.; Babu, P.N. Statistical optimization of parameters affecting lipid productivity of microalga Chlorella protothecoides cultivated in photobioreactor under nitrogen starvation. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2017, 23, 26-37. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, G.; Daile, S.B.; Chakraborty, S.; Atta, A. Influence of super-optimal light intensity on the acetic acid uptake and microalgal growth in mixotrophic culture of Chlorella sorokiniana in bubble-column photobioreactors. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 393, 130152. [CrossRef]

- Metsoviti, M.N.; Papapolymerou, G.; Karapanagiotidis, I.T.; Katsoulas, N. Effect of light intensity and quality on growth rate and composition of Chlorella vulgaris. Plants, 2020, 9, 31. [CrossRef]

- Nzayisenga, J.C.; Farge, X.; Groll, S.L; Sellstedt, A. Effects of light intensity on growth and lipid production in microalgae grown in wastewater. Biotechnol Biofuels 2020, 13, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Xue, C.; Yang, M.; Li, L.; Qian, P.; Gao, Z.; Gao, Z.; Deng, X. Optimization of light intensity and photoperiod for growing Chlorella sorokiniana on cooking cocoon wastewater in a bubble-column bioreactor. Algal Research 2022, 62, 102612. [CrossRef]

- Minhas, A.K.; Hodgson, P.; Barrow, C.J.; Adholeya, A. A review on the assessment of stress conditions for simultaneous production of microalgal lipids and carotenoids. Front. Μicrobiol. 2016, 7, 183978. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; He, Q. Assessment of environmental stresses for enhanced microalgal biofuel production–an overview. Front. Energy Res. 2014, 2, 26. [CrossRef]

- Ummalyma, S.B.; Sirohi, R.; Udayan, A.; Yadav, P.; Raj, A.; Sim, S.J.; Pandey, A. Sustainable microalgal biomass production in food industry wastewater for low-cost biorefinery products: a review. Phytochem. Rev. 2023, 22, 969-991. [CrossRef]

- Gururani, P.; Bhatnagar, P.; Kumar, V.; Vlaskin, M.S.; Grigorenko, A.V. Algal Consortiums: A Novel and Integrated Approach for Wastewater Treatment. Water 2022, 14, 3784. [CrossRef]

- Dębowski, M.; Zieliński, M.; Kazimierowicz, J.; Kujawska, N.; Talbierz, S. Microalgae cultivation technologies as an opportunity for bioenergetic system development advantages and limitations. Sustainability, 2020, 12, 9980. [CrossRef]

- Psachoulia, P.; Schortsianiti, S.N.; Lortou, U.; Gkelis, S.; Chatzidoukas, C. Samaras, P. Assessment of nutrients recovery capacity and biomass growth of four microalgae species in anaerobic digestion effluent. Water, 2022, 14, 221. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.N.; Aditya, L.; Vu, H.P.; Johir, A.H.; Bennar, L.; Ralph, P.; Nghiem, L. D. Nutrient removal by algae-based wastewater treatment. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2022, 8, 369-383. [CrossRef]

- Acién Fernández, F.G.; Gómez-Serrano, C.; Fernández-Sevilla, J.M. Recovery of nutrients from wastewaters using microalgae. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 59. [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Yang, Y.; Chou, S.; Ge, S.; Li, P.; Wang, X.; Zhung, L.; Zhang, J. Effect of N/P ratio on attached microalgae growth and the differentiated metabolism along the depth of biofilm. Environ. Res. 2024, 240, 117428. [CrossRef]

- Ummalyma Choi, H.J.; Lee, S.M. Effect of the N/P ratio on biomass productivity and nutrient removal from municipal wastewater. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 38, 761-766. [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.; Shilton, A. Luxury uptake of phosphorus by microalgae in waste stabilisation ponds: current understanding and future direction. Rev. Environ. Sci. And Biotechnol. 2014, 13, 321-328.

- Kamyab, H.; Chelliapan, S.; Lee, C.T.; Khademi, T.; Kumar, A.; Yadav, K.K.; Ebrahimi, S. S. Improved production of lipid contents by cultivating Chlorella pyrenoidosa in heterogeneous organic substrates. CLEAN TECHNOL. ENVIR. 2019, 21, 1969-1978. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ameri, M.; Al-Zuhair, S. Using switchable solvents for enhanced, simultaneous microalgae oil extraction-reaction for biodiesel production. Biochem. Eng. J. 2019, 141, 217-224. [CrossRef]

- Bligh, E. G.; Dyer, W. J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911-917. [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Vallejo, C.; Guzmán Duque, F.L.; Quintero Díaz, J.C. Biomass and lipid production by the native green microalgae Chlorella sorokiniana in response to nutrients, light intensity, and carbon dioxide: experimental and modeling approach. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1149762. [CrossRef]

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosebrough, N.J.; Farr, A.L.; Randall, R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 193, 265-275. [CrossRef]

- DuBois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.T.; Smith, F. Colorimetricmethod for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350-356. [CrossRef]

- Maltsev, Y.; Maltseva, K.; Kulikovskiy, M.; Maltseva, S. Influence of light conditions on microalgae growth and content of lipids, carotenoids, and fatty acid composition. Biology, 2021, 10, 1060. [CrossRef]

- Safaee, M.; Abdolalian, S.; Moghaddam, S. Y. Optimization of chlorella sorokiniana growth via response surface methodology. In Proceedings of the third international conference on new research and achievements in science, engineering and technologies, Berlin, Germany, 6 January 2024.

- Ali H.E.A.; El-fayoumy, E.A.; Rasmy, W.E.; Soliman R.M.; Abdullah M.A. Two-stage cultivation of Chlorella vulgaris using light and salt stress conditions for simultaneous production of lipid, carotenoids, and antioxidants. J. Appl. Phyc. 2021, 33, 227-239. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhao, S.; Yan, S.; Qiu, Y.; Song, C.; Li, Y.; Kitamura, Y. Food processing wastewater purification by microalgae cultivation associated with high value-added compounds production-A review. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 27, 2845-2856. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Guo, L.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. Effect of phosphorus concentration and light/dark condition on phosphorus uptake and distribution with microalgae. Bioresour. Technol., 2021, 340, 125745. [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo-Mirquez, L.; Lopes, F.; Taidi, B.; Pareau, D. Nitrogen and phosphate removal from wastewater with a mixed microalgae and bacteria culture. Biotechnol. Rep. 2016, 11, 18-26. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.A.H.; Yaakob, Z.; Abdullah, S.R.S.; Takriff, M.S. Analysis of the elemental composition and uptake mechanism of Chlorella sorokiniana for nutrient removal in agricultural wastewater under optimized response surface methodology (RSM) conditions. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 673-686. [CrossRef]

- Powell, N.; Shilton, A.; Chisti, Y.; Pratt, S. Towards luxury uptake process via microalgae: defining the polyphosphate dynamics. Water Res. 2009, 43, 4207–4213. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).