Submitted:

24 April 2025

Posted:

25 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chlamydomonas Strains and Growth Conditions

2.2. Growth Test

2.3. Quantification of Chlamydomonas Cell Growth

2.4. Preparation of the Selectable Marker for Insertional Mutagenesis

2.5. Chlamydomonas Transformation

2.6. Genomic DNA Isolation from Chlamydomonas

2.7. DNA Quantification

2.8. Purification of DNA Fragments from Agarose Gels

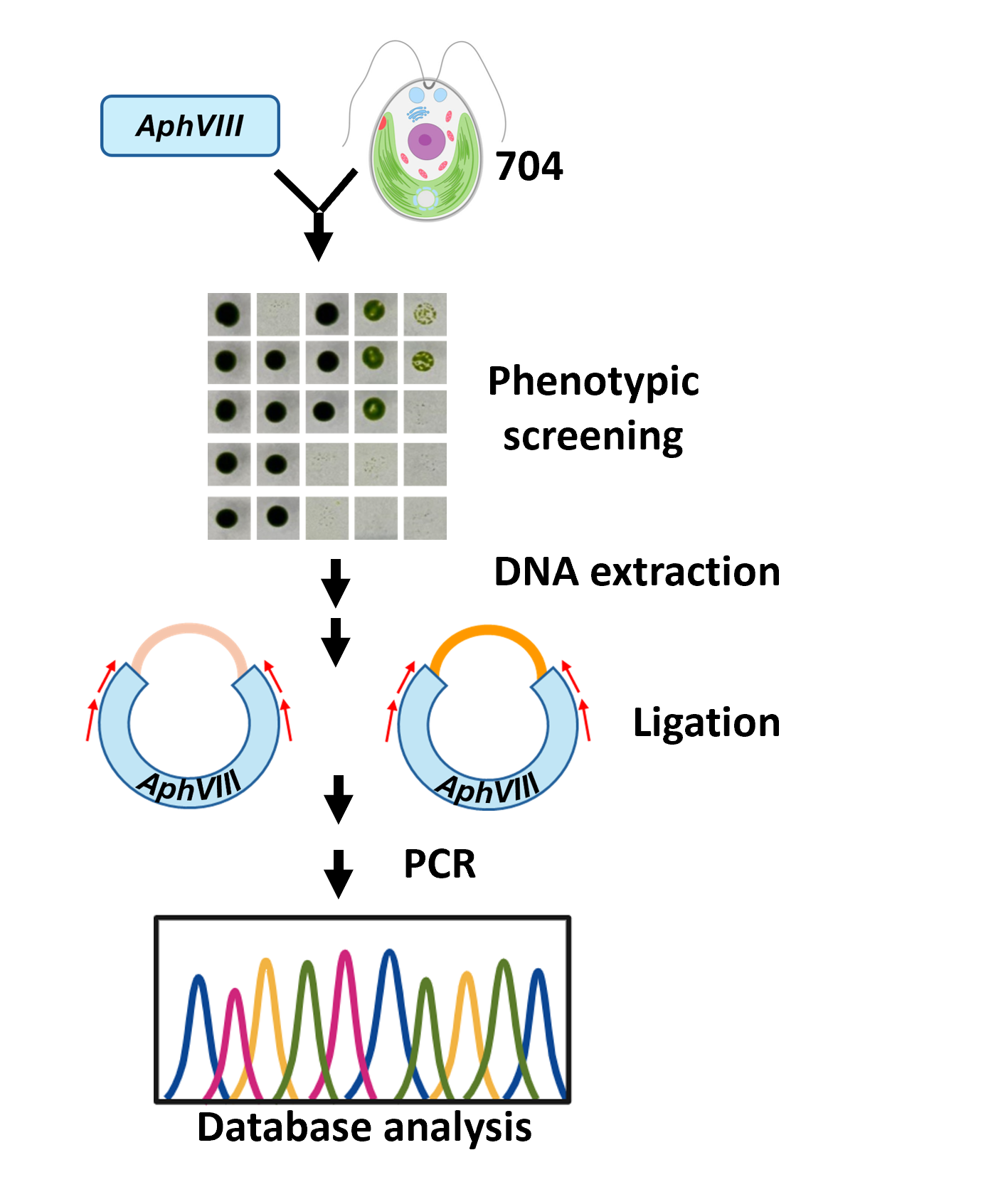

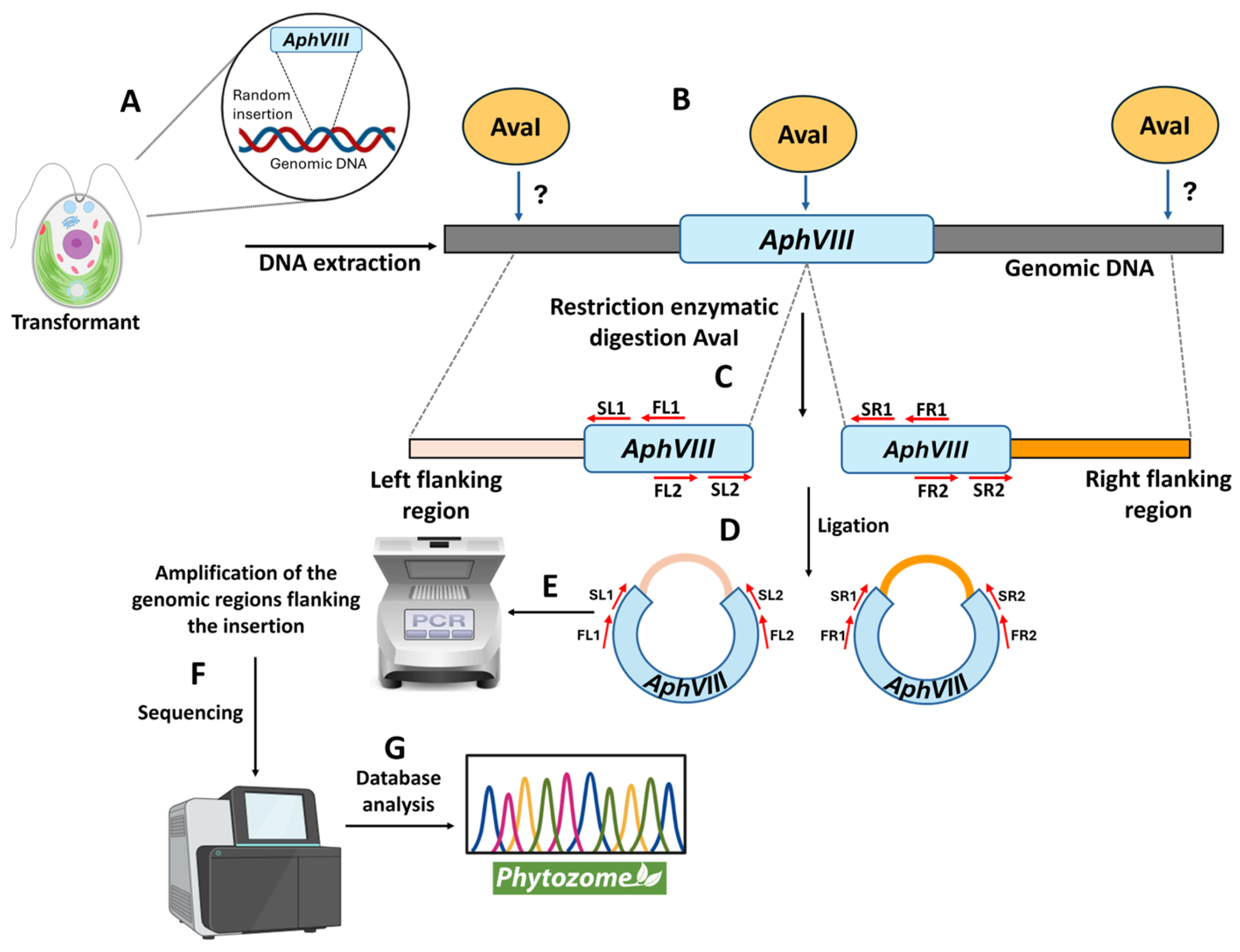

2.9. Identification of the Genomic Region Adjacent to the AphVIII Marker Insertion

2.10. Bioinformatics Tools

3. Results

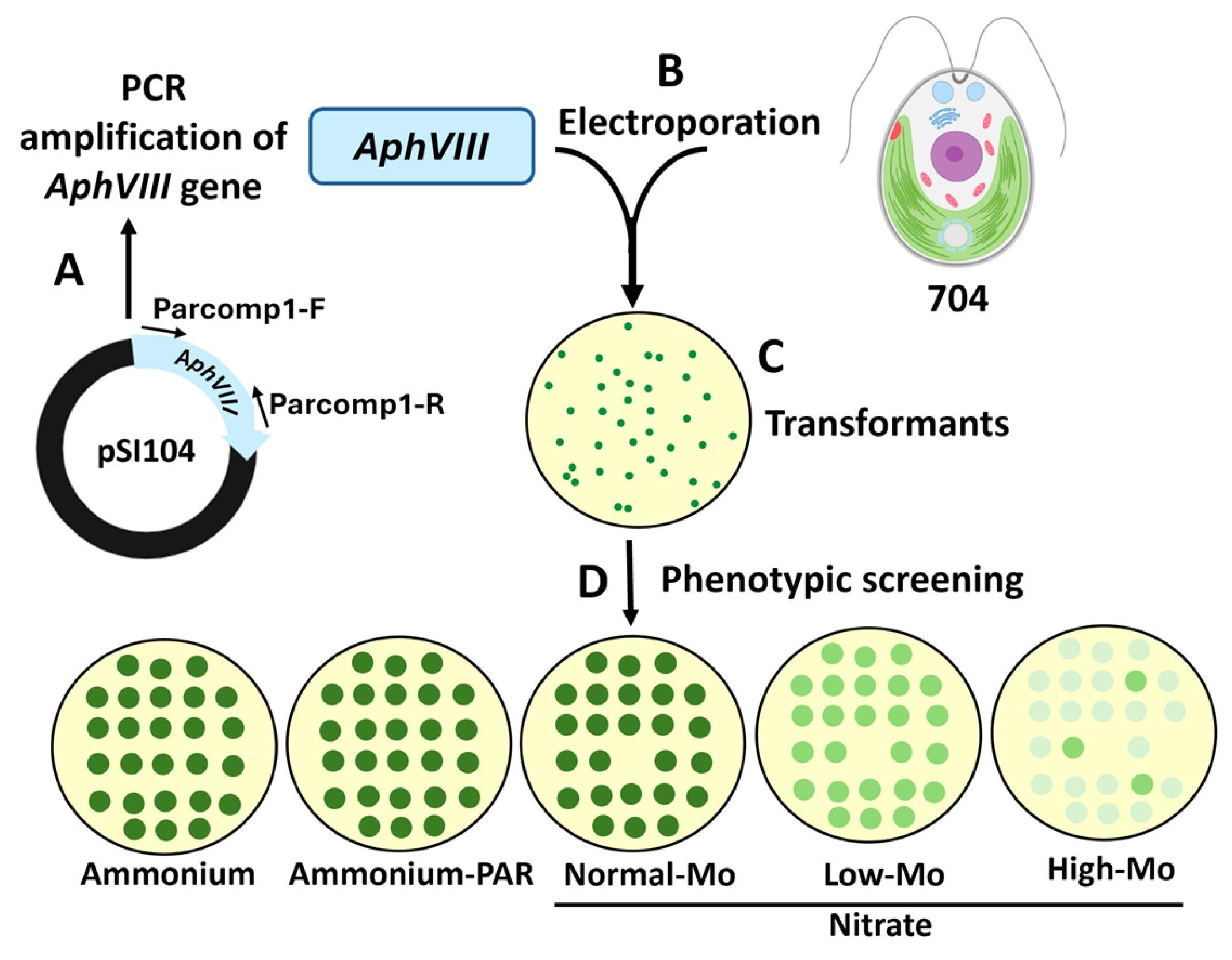

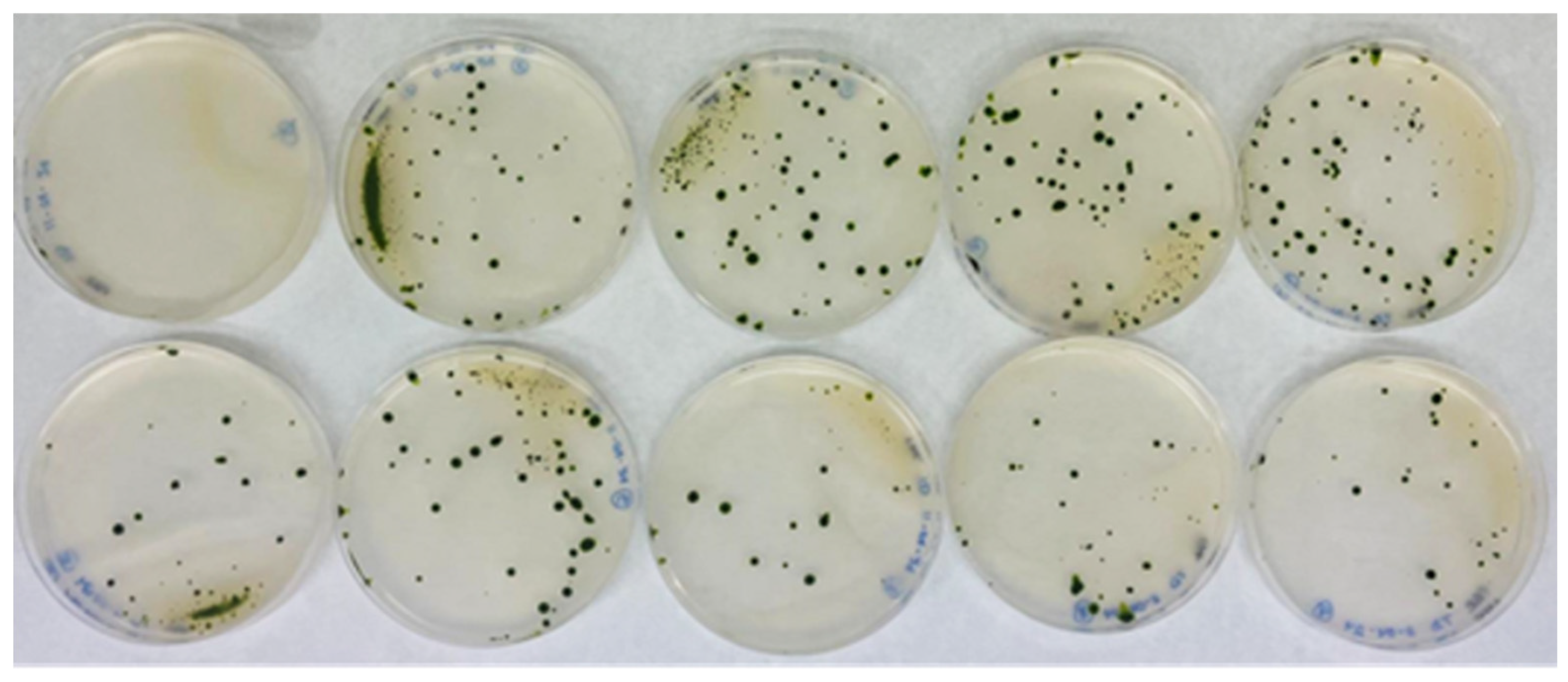

3.1. Generation of an Insertional Mutant Collection

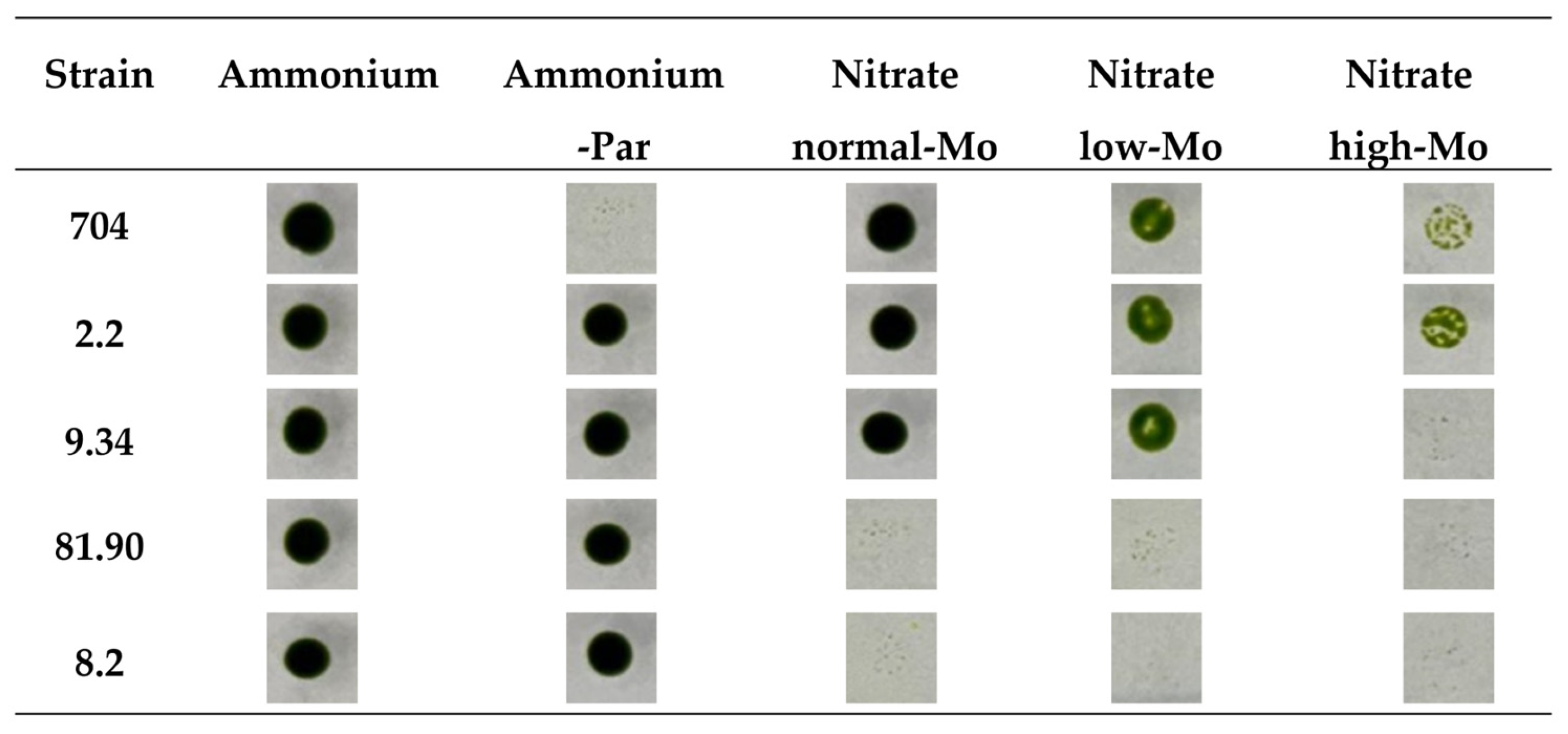

3.2. Phenotypic Analysis of Transformants in Relation to Mo and Nitrate Homeostasis

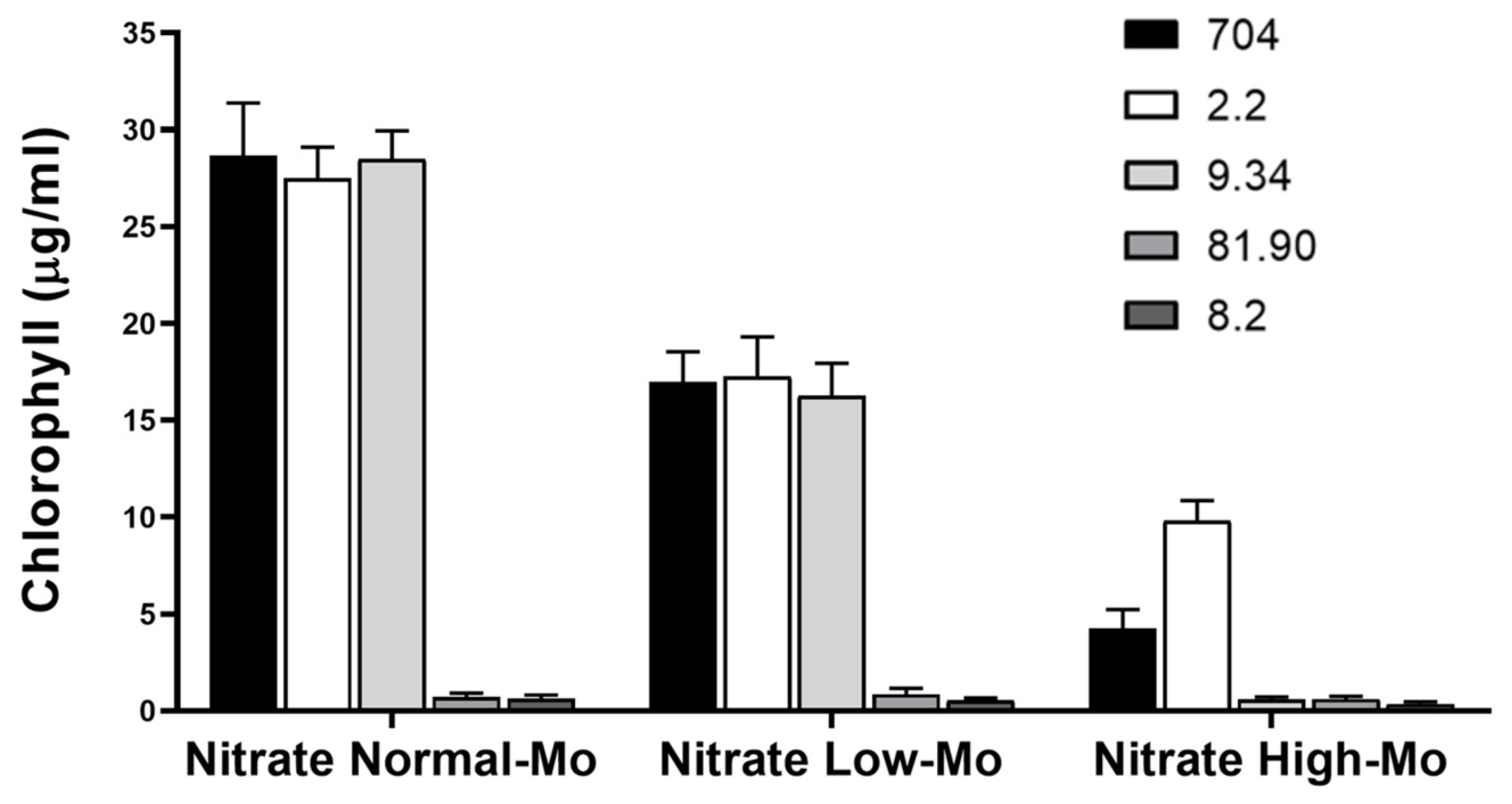

3.3. Localization of the AphVIII Marker Insertion in the Transformants

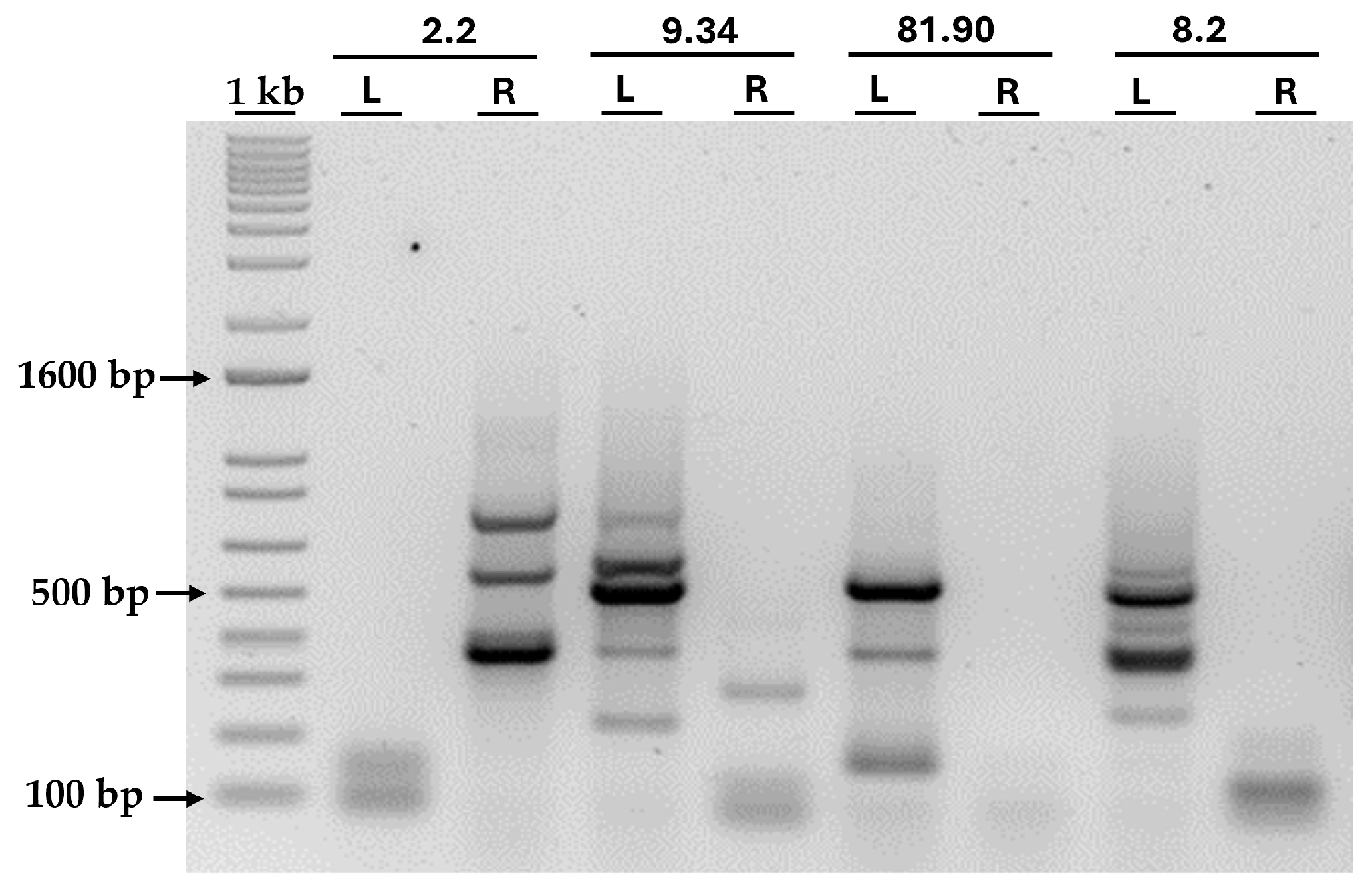

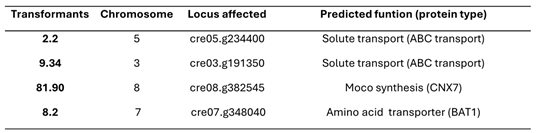

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iakovidou, G.; Itziou, A.; Tsiotsias, A.; Lakioti, E.; Samaras, P.; Tsanaktsidis, C.; Karayannis, V. Application of Microalgae to Wastewater Bioremediation, with CO2 Biomitigation, Health Product and Biofuel Development, and Environmental Biomonitoring. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellido-Pedraza, C.M.; Torres, M.J.; Llamas, A. The Microalgae Chlamydomonas for Bioremediation and Bioproduct Production. Cells 2024, 13, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salomé, P.A.; Merchant, S.S. A Series of Fortunate Events: Introducing Chlamydomonas as a Reference Organism. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 1682–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, E.H. Chlamydomonas as a Model Organism. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 2001, 52, 363–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauser, F.; Vilarrasa-Blasi, J.; Onishi, M.; Ramundo, S.; Patena, W.; Millican, M.; Osaki, J.; Philp, C.; Nemeth, M.; Salomamp, P.A.; et al. Systematic Characterization of Gene Function in the Photosynthetic Alga Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostenkova, K.; Scalese, G.; Gambino, D.; Crans, D.C. Highlighting the Roles of Transition Metals and Speciation in Chemical Biology. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2022, 69, 102155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Finley, E.J.; Chakraborty, S.; Fretham, S.J.B.; Aschner, M. Cellular Transport and Homeostasis of Essential and Nonessential Metals. Metallomics 2012, 4, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, J.T.; Borthakur, D. Methods for Metal Chelation in Plant Homeostasis: Review. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 163, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, A.W.; Naeem, M.; Hussain, H.; Ahmad, N.; Xu, M. Starvation from within: How Heavy Metals Compete with Essential Nutrients, Disrupt Metabolism, and Impair Plant Growth. Plant Sci. 2025, 353, 112412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaby-Haas, C.E.; Merchant, S.S. The Ins and Outs of Algal Metal Transport. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Res. 2012, 1823, 1531–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufholdt, D.; Baillie, C.K.; Meinen, R.; Mendel, R.R.; Hänsch, R. The Molybdenum Cofactor Biosynthesis Network: In Vivo Protein-Protein Interactions of an Actin Associated Multi-Protein Complex. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnon, D.I.; Stout, P.R. Molybdenum as an Essential Element for Higher Plants. Plant Physiol 1939, 14, 599–602. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mendel, R.R. The History of the Molybdenum Cofactor-A Personal View. Molecules 2022, 27, 4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lešková, A.; Javot, H.; Giehl, R.F.H. Metal Crossroads in Plants: Modulation of Nutrient Acquisition and Root Development by Essential Trace Metals. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 1751–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Su, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, R.; Bartlam, M. Structural Analysis of Molybdate Binding Protein ModA from Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 681, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada-Jiménez, M.; Llamas, A.; Sanz-Luque, E.; Galván, A.; Fernández, E. A High-Affinity Molybdate Transporter in Eukaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 20126–20130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejada-Jiménez, M.; Galván, A.; Fernández, E. Algae and Humans Share a Molybdate Transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 6420–6425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamus, J.P.; Ruszczyńska, A.; Wyczałkowska-Tomasik, A. Molybdenum’s Role as an Essential Element in Enzymes Catabolizing Redox Reactions: A Review. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, L.M.; Ludden, P.W. Biosynthesis of the Iron-Molybdenum Cofactor of Nitrogenase. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 62, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannes, L.; Fu, C.Y.; Schwarz, G. Molybdenum Cofactor Deficiency in Humans. Molecules 2022, 27, 6896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendel, R.R.; Kruse, T. Cell Biology of Molybdenum in Plants and Humans. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012, 1823, 1568–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Hu, B.; Chu, C. Nitrogen Assimilation in Plants: Current Status and Future Prospects. J. Genet. Genomics 2022, 49, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamizo-Ampudia, A.; Sanz-Luque, E.; Llamas, A.; Ocaña-Calahorro, F.; Mariscal, V.; Carreras, A.; Barroso, J.B.; Galván, A.; Fernández, E. A Dual System Formed by the ARC and NR Molybdoenzymes Mediates Nitrite-Dependent NO Production in Chlamydomonas. Plant. Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 2097–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, B.; Struwe, M.A. The History of MARC. Molecules 2023, 28, 4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerin, S.; Mathy, G.; Blomme, A.; Franck, F.; Sluse, F.E. Plasticity of the Mitoproteome to Nitrogen Sources (Nitrate and Ammonium) in Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii: The Logic of Aox1 Gene Localization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 2010, 1797, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, S.J.; Mendel, R.-R.; Schwarz, G. Molybdenum Cofactor Biology, Evolution and Deficiency. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Res. 2021, 1868, 118883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, N.R. Opposing Functions for Plant Xanthine Dehydrogenase in Response to Powdery Mildew Infection: Production and Scavenging of Reactive Oxygen Species. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beedham, C. Aldehyde Oxidase; New Approaches to Old Problems. Xenobiotica 2020, 50, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Trelles, F.; Tarrío, R.; Ayala, F.J. Convergent Neofunctionalization by Positive Darwinian Selection after Ancient Recurrent Duplications of the Xanthine Dehydrogenase Gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003, 100, 13413–13417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada-Jimenez, M.; Chamizo-Ampudia, A.; Galvan, A.; Fernandez, E.; Llamas, A. Molybdenum Metabolism in Plants. Metallomics 2013, 5, 1191–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Fernie, A.R.; Zhang, Y. Engineering Nitrogen and Carbon Fixation for Next-Generation Plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2025, 85, 102699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohresser, M.; Matagne, R.F.; Loppes, R. Expression of the Arylsulphatase Reporter Gene under the Control of the Nit1 Promoter in Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii. Curr. Genet. 1997, 31, 264–271. [Google Scholar]

- Arnon, D.I. Copper Enzumes in Isolated Chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta Vulgaris. Plant Physiol 1949, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Patena, W.; Fauser, F.; Jinkerson, R.E.; Saroussi, S.; Meyer, M.T.; Ivanova, N.; Robertson, J.M.; Yue, R.; Zhang, R.; et al. A Genome-Wide Algal Mutant Library and Functional Screen Identifies Genes Required for Eukaryotic Photosynthesis. Nat Genet 2019, 51, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sizova, I.; Fuhrmann, M.; Hegemann, P. A Streptomyces Rimosus AphVIII Gene Coding for a New Type Phosphotransferase Provides Stable Antibiotic Resistance to Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii. Gene 2001, 277, 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Shimogawara, K.; Fujiwara, S.; Grossman, A.; Usuda, H. High-Efficiency Transformation of Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii by Electroporation. Genetics 1998, 148, 1821–1828. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.W.; Villar-Briones, A.; Luscombe, N.M.; Plessy, C. Automated Phenol-Chloroform Extraction of High Molecular Weight Genomic DNA for Use in Long-Read Single-Molecule Sequencing. F1000Research 2022, 11, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochman, H.; Gerber, A.S.; Hartl, D.L. Genetic Applications of an Inverse Polymerase Chain Reaction. Genetics 1988, 120, 621–623. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Doron, L.; Segal, N.; Shapira, M. Transgene Expression in Microalgae—From Tools to Applications. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ballester, D.; de Montaigu, A.; Galván, A.; Fernández, E. Restriction Enzyme Site-Directed Amplification PCR: A Tool to Identify Regions Flanking a Marker DNA. Anal Biochem 2005, 340, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunders, E.A.; Ngu, D.H.Y.; Ganio, K.; Hossain, S.I.; Lim, B.Y.J.; Leeming, M.G.; Luo, Z.; Tan, A.; Deplazes, E.; Kobe, B.; et al. The Impact of Chromate on Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Molybdenum Homeostasis. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 903146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dündar, E.; Bush, D.R. BAT1, a Bidirectional Amino Acid Transporter in Arabidopsis. Planta 2009, 229, 1047–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.Y.; Hu, D.W.; Zhao, F.J. Molybdenum: More than an Essential Element. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 1766–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada-Jimenez, M.; Leon-Miranda, E.; Llamas, A. Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii—A Reference Microorganism for Eukaryotic Molybdenum Metabolism. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomatsu, H.; Takano, J.; Takahashi, H.; Watanabe-Takahashi, A.; Shibagaki, N.; Fujiwara, T. An Arabidopsis Thaliana High-Affinity Molybdate Transporter Required for Efficient Uptake of Molybdate from Soil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007, 104, 18807–18812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, Y.; Kusano, M.; Oikawa, A.; Fukushima, A.; Tomatsu, H.; Saito, K.; Hirai, M.Y.; Fujiwara, T. Effects of Molybdenum Deficiency and Defects in Molybdate Transporter MOT1 on Transcript Accumulation and Nitrogen/Sulphur Metabolism in Arabidopsis Thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 1483–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Díez, P.; Tejada-Jiménez, M.; León-Mediavilla, J.; Wen, J.; Mysore, K.S.; Imperial, J.; González-Guerrero, M. MtMOT1.2 Is Responsible for Molybdate Supply to Medicago Truncatula Nodules. Plant. Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejada-Jiménez, M.; Gil-Díez, P.; León-Mediavilla, J.; Wen, J.; Mysore, K.S.; Imperial, J.; González-Guerrero, M. Medicago Truncatula Molybdate Transporter Type 1 (MtMOT1.3) Is a Plasma Membrane Molybdenum Transporter Required for Nitrogenase Activity in Root Nodules under Molybdenum Deficiency. New Phytol. 2017, 216, 1223–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Li, M.; Zhao, F.J.; Huang, X.Y. The Vacuolar Molybdate Transporter OsMOT1;2 Controls Molybdenum Remobilization in Rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 863816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuveny, Z. Derepression of ATP Sulfurylase by the Sulfate Analogs Molybdate and Selenate in Tobacco Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 619–622. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, K.C.; Woodards, N.A.; Xu, H.; Barton, L.L. Reduction of Molybdate by Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria. BioMetals 2009, 22, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas, A.; Kalakoutskii, K.L.; Fernández, E. Molybdenum Cofactor Amounts in Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii Depend on the Nit5 Gene Function Related to Molybdate Transport. Plant, Cell Environ. 2000, 23, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Makova, M.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Rhodes, C.J.; Valko, M. Essential Metals in Health and Disease. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2022, 367, 110173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndyke, M.P.; Guimaraes, O.; Kistner, M.J.; Wagner, J.J.; Engle, T.E. Influence of Molybdenum in Drinking Water or Feed on Copper Metabolism in Cattle—A Review. Animals 2021, 11, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, N.; Møller, L.B.; Nurchi, V.M.; Aaseth, J. Chelating Principles in Menkes and Wilson Diseases: Choosing the Right Compounds in the Right Combinations at the Right Time. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2019, 190, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhead, J.L.; Gogolin Reynolds, K.A.; Abdel-Ghany, S.E.; Cohu, C.M.; Pilon, M. Copper Homeostasis. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 799–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuper, J.; Llamas, A.; Hecht, H.-J.; Mendel, R.R.; Schwarz, G. Structure of the Molybdopterin-Bound Cnx1G Domain Links Molybdenum and Copper Metabolism. Nature 2004, 430, 803–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, K.L.; Tyerman, S.D.; Kaiser, B.N. Molybdate Transport through the Plant Sulfate Transporter SHST1. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 1508–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Z.; Nie, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, S.; Liu, S.; Wang, D.; Wang, D.; Zhao, P.; Zhao, P.; et al. Adsorption Kinetic Characteristics of Molybdenum in Yellow-Brown Soil in Response to PH and Phosphate. Open Chem. 2020, 18, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschner, H.; Kirkby, E.A. Phosphorus Deficiency Enhances Molybdenum Uptake by Tomato Plants. J. Plant Nutr. 1992, 15, 549–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.; Tampé, R. Structural and Mechanistic Principles of ABC Transporters. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2020, 89, 605–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, A.; Locher, K.P. Structure and Mechanism of Human ABC Transporters. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2023, 52, 230–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, A.J.; Harrison, A.; Alvarez, F.J.D.; Davidson, A.L.; Pinkett, H.W. Small Substrate Transport and Mechanism of a Molybdate ATP Binding Cassette Transporter in a Lipid Environment. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 15005–15013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppe, J.; Warkentin, E.; Demmer, U.; Kowalewski, B.; Dierks, T.; Schneider, K.; Ermler, U. Structural Diversity of Polyoxomolybdate Clusters along the Three-Fold Axis of the Molybdenum Storage Protein. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2014, 138, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, U.G.; Stupperich, E.; Kratky, C. Structure of the Molybdate/Tungstate Binding Protein Mop from Sporomusa Ovata. Structure 2000, 8, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Llamas, A.; Tejada-Jiménez, M.; Fernández, E.; Galván, A. Molybdenum Metabolism in the Alga Chlamydomonas Stands at the Crossroad of Those in Arabidopsis and Humans. Metallomics 2011, 3, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänzelmann, P.; Hernández, H.L.; Menzel, C.; García-Serres, R.; Huynh, B.H.; Johnson, M.K.; Mendel, R.R.; Schindelin, H. Characterization of MOCS1A, an Oxygen-Sensitive Iron-Sulfur Protein Involved in Human Molybdenum Cofactor Biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 34721–34732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, Y.; Harada, A.; Hashiguchi, Y.; Nakai, M.; Hayashi, H. Arabidopsis Molybdopterin Biosynthesis Protein Cnx5 Collaborates with the Ubiquitin-like Protein Urm11 in the Thio-Modification of TRNA. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 30874–30884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas, A.; Mendel, R.R.; Schwarz, G. Synthesis of Adenylated Molybdopterin: An Essential Step for Molybdenum Insertion. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 55241–55246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas, A.; Tejada-Jimenez, M.; González-Ballester, D.; Higuera, J.J.; Schwarz, G.; Galván, A.; Fernández, E. Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii CNX1E Reconstitutes Molybdenum Cofactor Biosynthesis in Escherichia Coli Mutants. Eukaryot. Cell 2007, 6, 1063–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas, A.; Otte, T.; Multhaup, G.; Mendel, R.R.; Schwarz, G. The Mechanism of Nucleotide-Assisted Molybdenum Insertion into Molybdopterin. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 18343–18350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataya, F.S.; Witte, C.P.; Galván, A.; Igeño, M.I.; Fernández, E. Mcp1 Encodes the Molybdenum Cofactor Carrier Protein in Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii and Participates in Protection, Binding, and Storage Functions of the Cofactor. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 10885–10890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, K.; Llamas, A.; Tejada-Jiménez, M.; Schrader, N.; Kuper, J.; Ataya, F.S.; Galván, A.; Mendel, R.R.; Fernández, E.; Schwarz, G. Function and Structure of the Molybdenum Cofactor Carrier Protein from Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 30186–30194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Ballester, D.; de Montaigu, A.; Higuera, J.J.; Galván, A.; Fernández, E. Functional Genomics of the Regulation of the Nitrate Assimilation Pathway in Chlamydomonas. Plant Physiol. 2005, 137, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeyama, S.; Kanda, S.; Sakamoto, S.; Sakoda, A.; Miura, K.; Yoneda, R.; Nogi, A.; Ariji, S.; Shimoda, M.; Ono, M.; et al. A Case of Early Onset Cystinuria in a 4-Month-Old Girl. CEN case reports 2022, 11, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, E.; Galvan, A. Inorganic Nitrogen Assimilation in Chlamydomonas. J Exp Bot 2007, 58, 2279–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, O.; Hewedy, O.A.; Abdelmoteleb, A.; Ali, M.; Youssef, M.S.; Roumia, A.F.; Seymour, D.; Yuan, Z.C. Nitrogen Journey in Plants: From Uptake to Metabolism, Stress Response, and Microbe Interaction. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.J.; Fan, X.; Shen, Q.; Smith, S.J. Amino Acids and Nitrate as Signals for the Regulation of Nitrogen Acquisition. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.; López, G.; Argueta, S.; Escalera-Fanjul, X.; El Hafidi, M.; Campero-Basaldua, C.; Strauss, J.; Riego-Ruiz, L.; González, A. Diversification of Transcriptional Regulation Determines Subfunctionalization of Paralogous Branched Chain Aminotransferases in the Yeast Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Genetics 2017, 207, 975–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svietlova, N.; Zhyr, L.; Reichelt, M.; Grabe, V.; Mithöfer, A. Glutamine as Sole Nitrogen Source Prevents Induction of Nitrate Transporter Gene NRT2.4 and Affects Amino Acid Metabolism in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1369543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).