1. Introduction

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are used in a wide variety of applications and are one of the most studied nanoparticles (NPs) because of their antimicrobial capabilities and their applications in different industries as textile or wastewater treatment [

1]. Biomedical applications of AgNPs have been reviewed widely considering pros and cons of their application and listing their antibacterial and antifungal properties [

2,

3] and their antiviral, anti-inflammatory or antiangiogenic (inhibition of the formation of new blood vessels) effects (Zhang et al. 2016). Because of the great spectrum of applications and potential uses, different methodologies have been proposed for the synthesis of AgNPs, as the chemical reduction, the biological reduction or physical methods such as laser irradiation [

5]. According to the synthesis method selected, the resulting AgNPs possess a variety of shapes and size distributions, which in turn influence their optical properties and the ability to interact with specific molecules [

6].

One strategy to produce AgNPs is the chemical reduction synthesis, which precisely controls nanoparticle size and shape meanwhile biological or green synthesis generate amorphous nanoparticles with nanoparticle surface functionalities that are useful for certain applications [

7]. This strategy has resulted in a variate set of morphologies (cubical, triangular, oval, pebble-like, and circular in shape) in a single pattern or aggregated [

8,

9] with a diameter size >30 nm [

10]. The use of ultrasonic energy in green AgNPs synthesis has favored the formation of AgNPs with a smaller size and improved monodispersity [

11,

12]. The use of ultrasonic energy and plant extracts for AgNPs synthesis has proved to produce smaller AgNPs (diameter < 10 nm) with spherical morphologies [

13] than magnetic stirring (± 40 nm; Deshmukh, Gupta, and Kim 2019), where ultrasound has been used to assist synthesis in different plan extracts [

15,

16,

17]

Size and morphology are essential for applications in plasmonic sensors, where sensitivity and specificity of detection are critical [

18]. Different challenges arise in the research and development of specific NPs and their applicability as biosensors, as follows: The stability of the nanoparticles in the medium, the aggregation over time, the control of the growth of the nanoparticle crystals, the morphology, the size and the size distribution [

19]. Lorca-Ponce et al. [

20] showed that AgNPs modified by high-power Light-Emitting Diode (LED) energy, produce diverse morphologies that present different catalytic activities towards methylene blue (MB) degradation. Spherical AgNPs possessed a more negative ξ potential (mV) meanwhile nanoparticles with cubic morphology presented a less negative potential. Also, current response was found to be inversely proportional to the size of nanostructure, consistent with the lower surface area of AgNPs.

Monodispersity and stability of AgNPs are variables to consider over time, because these characteristics are or great relevance in practical applications where consistency and reliability are required. Marciniak et al. [

21] found a great stability of AgNPs reduced with citric acid and malic acid at pH > 7,0, where the stability of rods and quasi-spherical morphologies after 7 weeks of synthesis was found, according to the SPR signal and SEM characterization. For AgNPs exposed to acidic and alkaline pH, the stability of silver ions aggregation into AgNPs was found to be pH dependent, showing NPs of high diameter (around 400 nm) at pH<5,0 and a higher concentration of Ag+ ions in solution, in contrast to AgNPs synthetized at pH>7,0 where NPs diameter is lower and a lower Ag+ ions concentration was found [

22,

23]. In addition to the pH, the concentration of salts in the reaction and the exposure to light also affect aggregation of AgNPs [

24,

25,

26]. Another factor to contemplate is the use of high pressure on synthetized AgNPs. In the case of small AgNPs (5 – 10 nm) exposed to ultra-high pressure at gigapascal (GPa) level, undergo a structural distortion consistent with a rhombohedral distortion with increasing pressure (Koski et al. 2008).

Synthetized AgNPs can be used as colorimetric detectors when surface plasmonic resonance (SPR) changes in the moment the nanoparticle specifically interacts with a specific compound [

28], or as electrochemical sensors. AgNP-based electrochemical sensors are based on the conversion of chemical reactions into measurable electrical signals, where kinetics of the redox reaction at the electrode surface influences the transduction efficiency [

29]. Also, AgNPs have been used as an antibacterial agent, because their main action on bacteria is related to the interaction and modification of the external bacterial membrane. According to Menichetti et al. [

30], the accumulation of AgNPs on bacterial membrane allows the penetration of particles and perturbation of membranes permeability. These effects caused by the production of Ag+ ions from the oxidative dissolution of AgNPs, which is favored by smaller particles, because of the faster the small particles dissolve, releasing more Ag+. In Addition to nanoparticle size, cubic shaped nanoparticles present best antibacterial activities than nanospheres and nanowires, due to the closer contact of nanocubes to bacterial surface. It has been explained by the higher reactivity of nanocube’s facet (100) than reactivity of facet (111) in nanospheres [

31].

On the other hand, to increase specificity, the AgNPs can be further functionalized and bioconjugated to allow the specific detection of substances. This functionalization generates changes in the SPR and provide a quantitative signal that can be used to determine the presence and concentration of the detected substance [

32,

33]. In the same way, the higher homogeneity of the NPs is achieved, the higher sensitivity of AgNPs is reached due to a sharper and more defined SPR peak [

34]. In the case of a capture probe like immunosensors, the AgNPs are bioconjugated to antibodies to enhance its selectivity toward targeted analytes, and to immobilize directly to the electrode surface to enhance selectivity and further quantify the amount of analyte detected [

35]. Also, as the proportion of available atoms at the surface of nanoparticle increases, the number of capping molecules do [

36].

Computational simulations carried out by Farcas et al. [

37] correlated the surface functionalization area with the van der Waals energy and counterion interactions. Results demonstrate that thiol molecule

’s surface density saturation on gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) is reached at less than 75% of coverage, if each sulfur atom of a thiol chain with chemical composition S-[CH2]2-CH3 is covalently bonded to the surface gold atoms of AuNPs. In the same way, at low thiol surface densities, these are arranged in a quasi-parallel orientation respecting AuNP surface, but at 50% of coverage, thiol chains are tightly packaged and are mostly loose from the surface. Finally, for larger AuNPs, the surface curvature is smaller and the access of counterions near the thiol-modified AuNP proves to be more difficult, than smaller AuNPs. Besides the number of surface atoms functionalized, the total number of functional groups in a factionalized nanoparticle determines the zeta potential and in consequence their colloidal stability, dispersibility and hydrophobicity or hydrophilicity, in addition to size, size distribution and the shape and morphology [

38]. As mention previously, the surface functionalization of NPs can be covered below 75%, because of the bulkiness of the functionalization compound and the steric effect caused by its chemical structure [

39]. Also, the type of chemical bond produced between the surface and the functionalization compound should be considered. For example, in the case of tightly covalent attached carbon chains to the NP surface, only steric effects affect the accessibility of the carbon chain [

40].

Because size is an important issue to consider if NPs are synthetized to be functionalized and bioconjugated for specific detection of molecules, the main objective of this work was to evaluate the effect of pH and pressure on the size and plasmonic characteristics of AgNPs by using ultrasound energy as a rapid and cost-effective synthesis method, and to develop different methods that allows the production of AgNPs with a specific size.

2. Results

2.1.

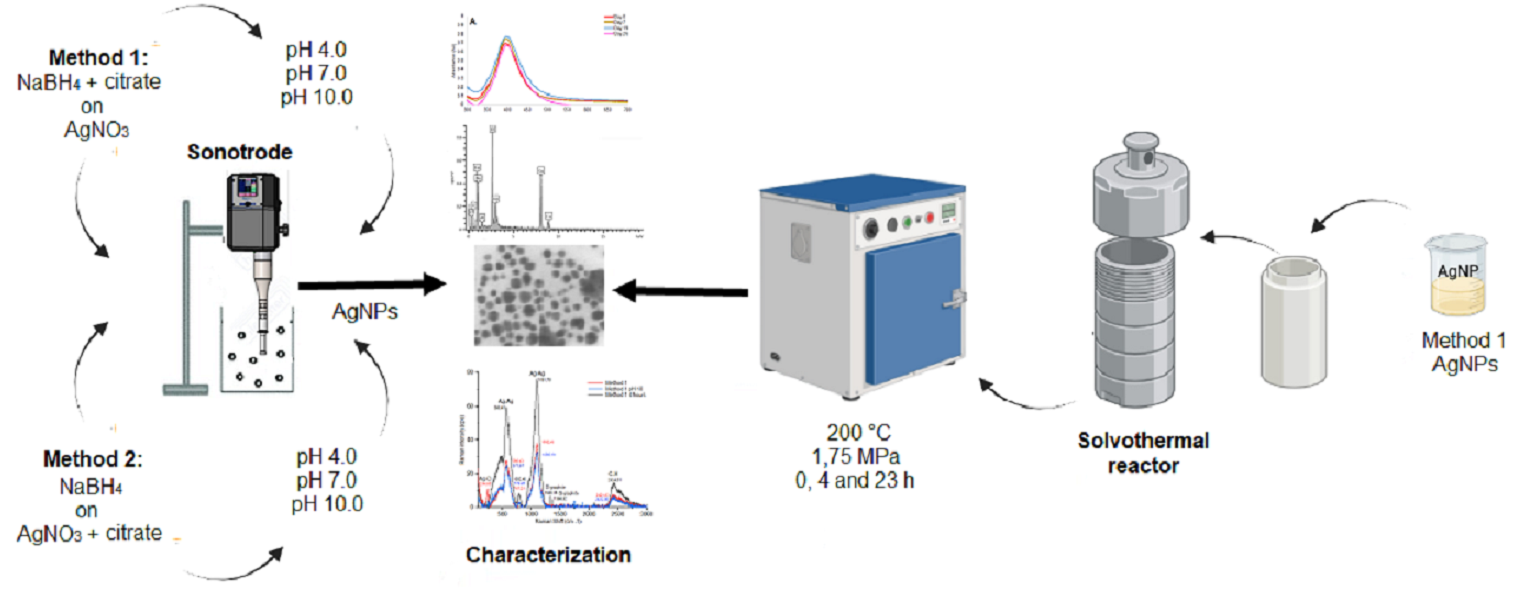

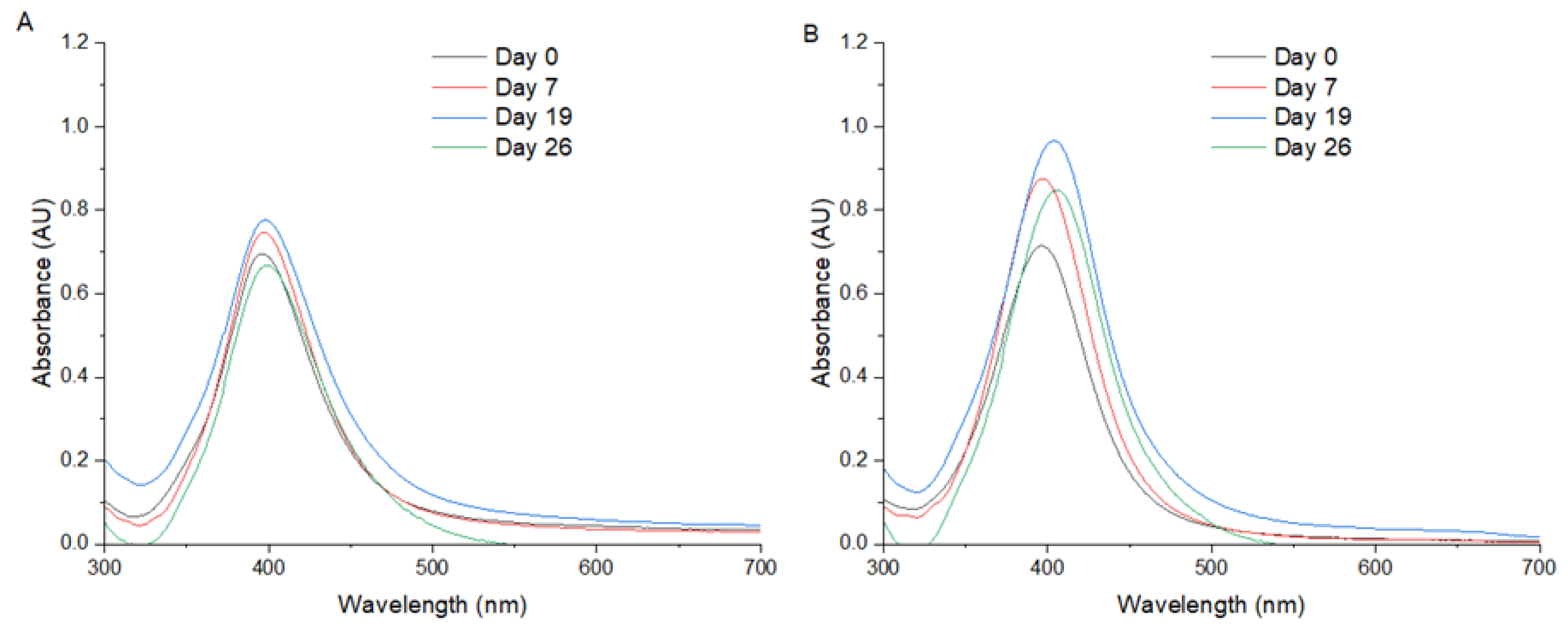

Figure 1 presents the UV/Vis spectra obtained from the AgNPs synthetized by method 1 (

Figure 1A) and method 2 (

Figure 1B), where a symmetry peak can be observed in both methods, with a maximum SPR on 396 nm.

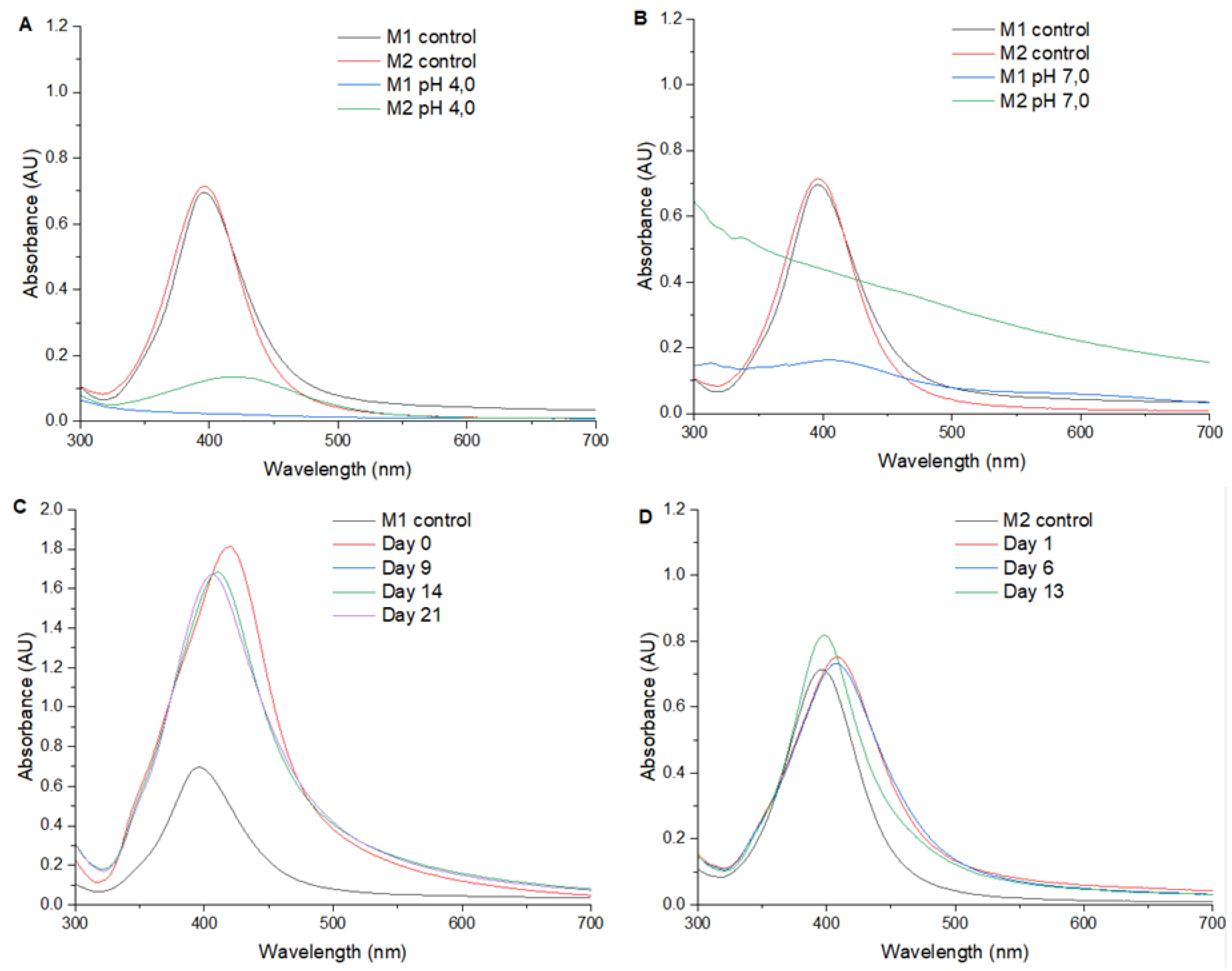

Figure 2 presents the UV/Vis spectra from 300 to 700 nm of AgNPs synthetized at pH 4,0, 7,0, 10,0 and in water. At pH 4,0 and 7,0 no SPR peak as found. At pH 10,0 it was found a shift of +10 nm in SPR peak, with reference to water.

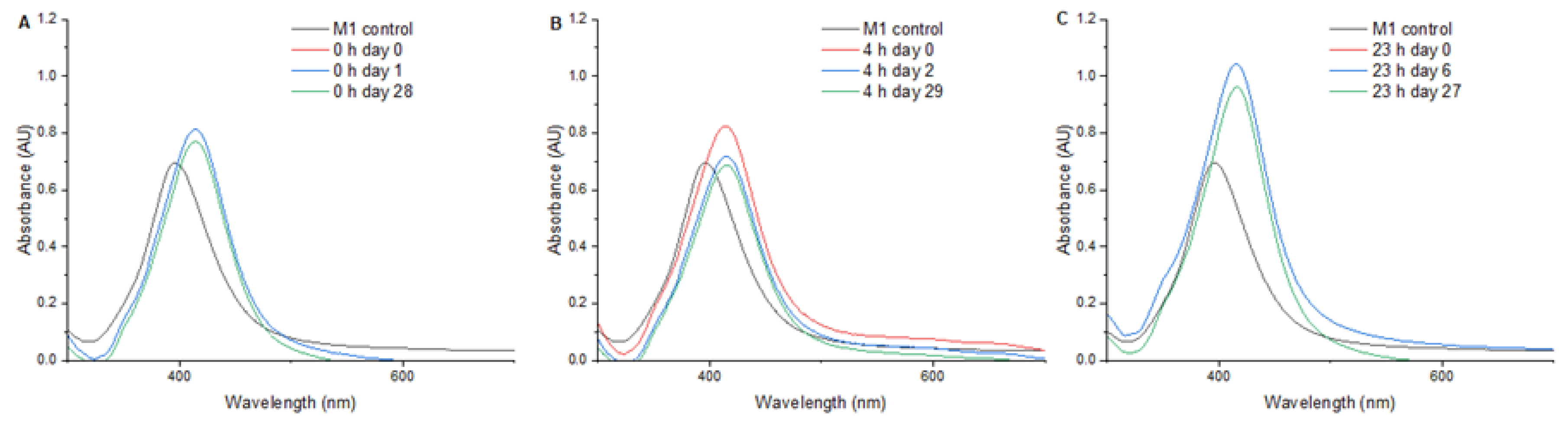

Figure 3 presents the UV/Vis spectra from 300 to 700 nm of AgNPs subjected to a pressure of 1,75 MPa for 0, 4 and 23 hours. Upon treatment for 0 hours (

Figure 3A) the AgNPs exhibited a maximum absorbance of 0.813 at 414 nm, showing a SPR shift of +18 nm. The measurement of SPR one day and 28 days after treatment showed no significant changes in the SPR. In the 4 hours treatment (

Figure 3B) a maximum absorbance of 0.825 at 414 nm was observed and a decrease in the SPR intensity was found two days after pressure treatment. In the 23 hours treatment (

Figure 3C) a SPR shift of +19 nm and an increase in the plasmon peak intensity was found.

Table 1 summarizes the SPR maximum and SPR shift obtained for each AgNPs treatment. Also, the “full width at half maximum” (FWHM) measured from the UV/Vis spectra is presented. Synthesis of AgNPs at pH 10 with method 1 and the pressure treatment of AgNPs at 1,75 mPa for 23 h produced the more intense SPR (higer values). In contrast, methods 1 and 2 produced the sharper SPR peaks, which in turn suggest a more homogeneous size diameter distribution.

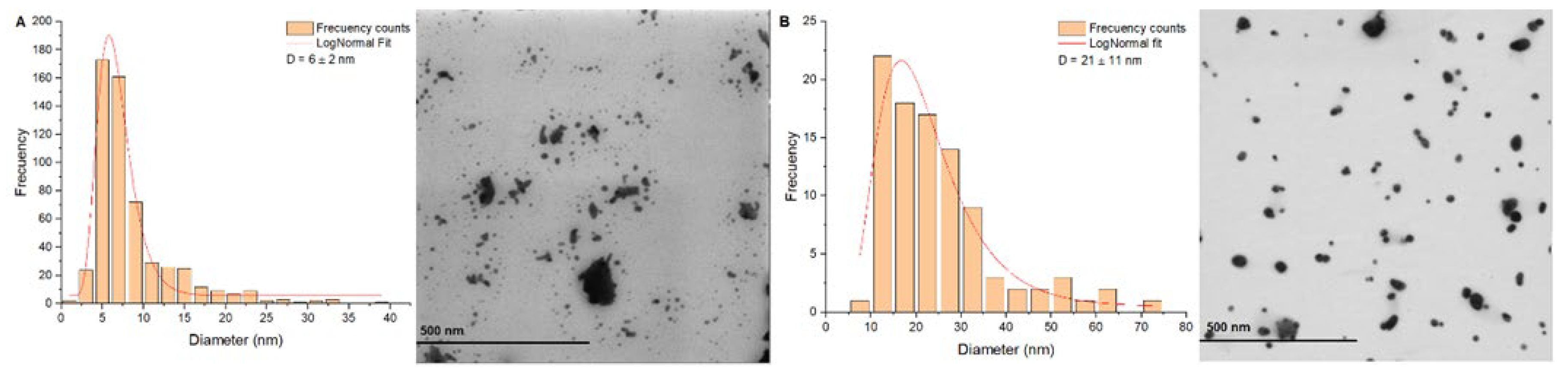

STEM images of AgNPs synthetized with the two synthesis methods are presented in

Figure 4.

Figure 4A presents the AgNPs synthetized with method 1, showing spherical morphologies with a diameter distribution of 6 ± 2 nm.

Figure 4B presents the AgNPs synthetized with method 2, which presented a diameter distribution of 21 ± 11 nm. AgNPs synthesized with method 1 at pH 10,0 resulted in particles with spherical morphologies at a submicrometric scale with a diameter distribution of 300 nm ± 84 nm.

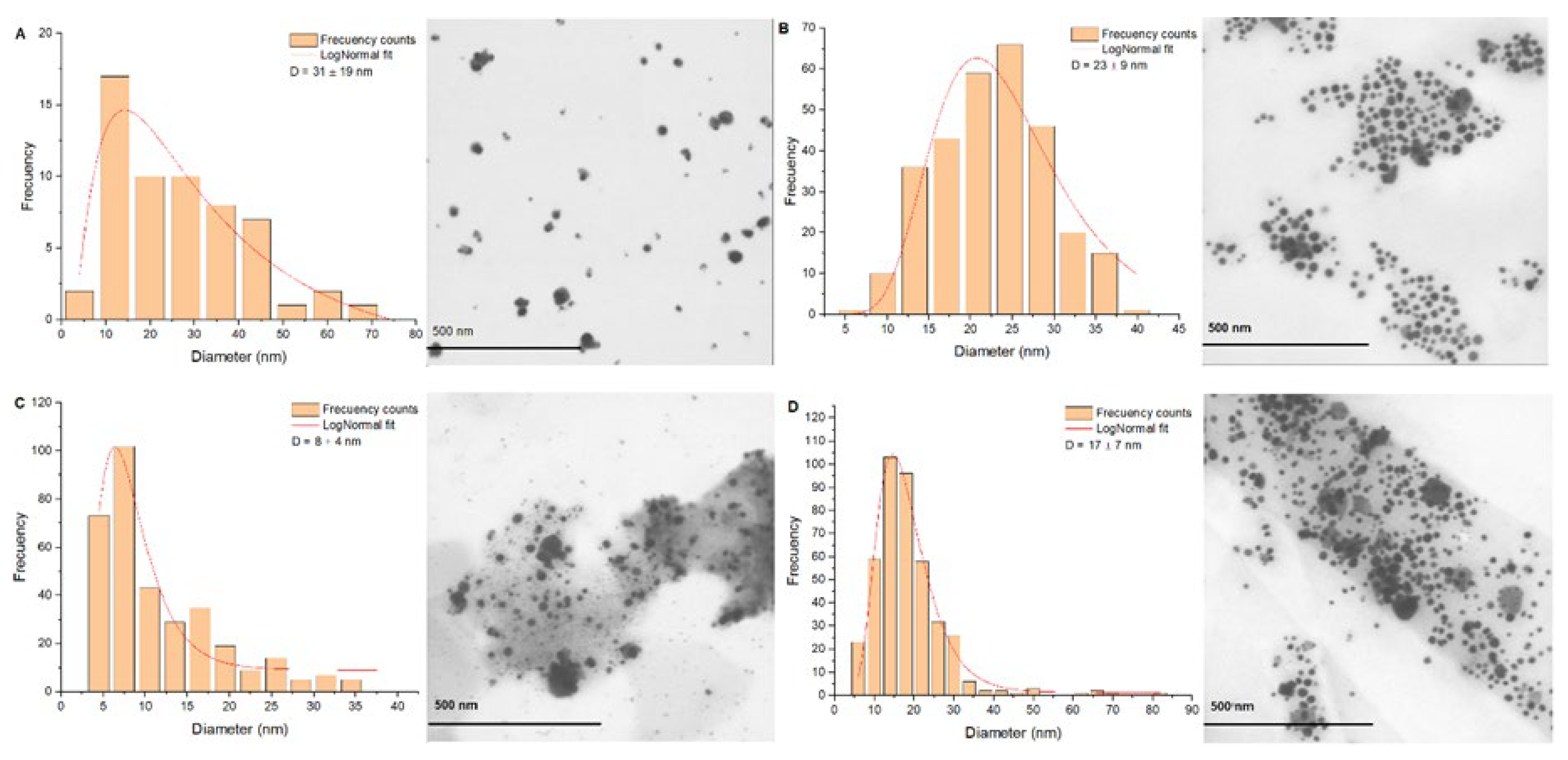

Figure 5 presents the synthesis with method 2 at pH 10,0 with a size distribution of 31 ± 19 nm (

Figure 5A). The AgNPs obtained at the end of the synthesis and subsequently subjected to a heat treatment at 200 °C until stabilization of solvothermal reactor to 1,75 MPa (0 hours) are presented in

Figure 5B. Very uniform spherical morphologies can be observed with a very symmetrical size distribution in a range of sizes of 23 ± 9 nm. At 4 hours of pressure exposure (

Figure 5C), spherical AgNPs are observed with a size distribution of 8 ± 4 nm. At 23 hours of pressure exposure (

Figure 5D), it is possible to observe spherical AgNPs with a much more uniform size distribution than the 0 hours and the 4 hours treatment, with a predominance of AgNPs with a diameter in the range 17 ± 7 nm.

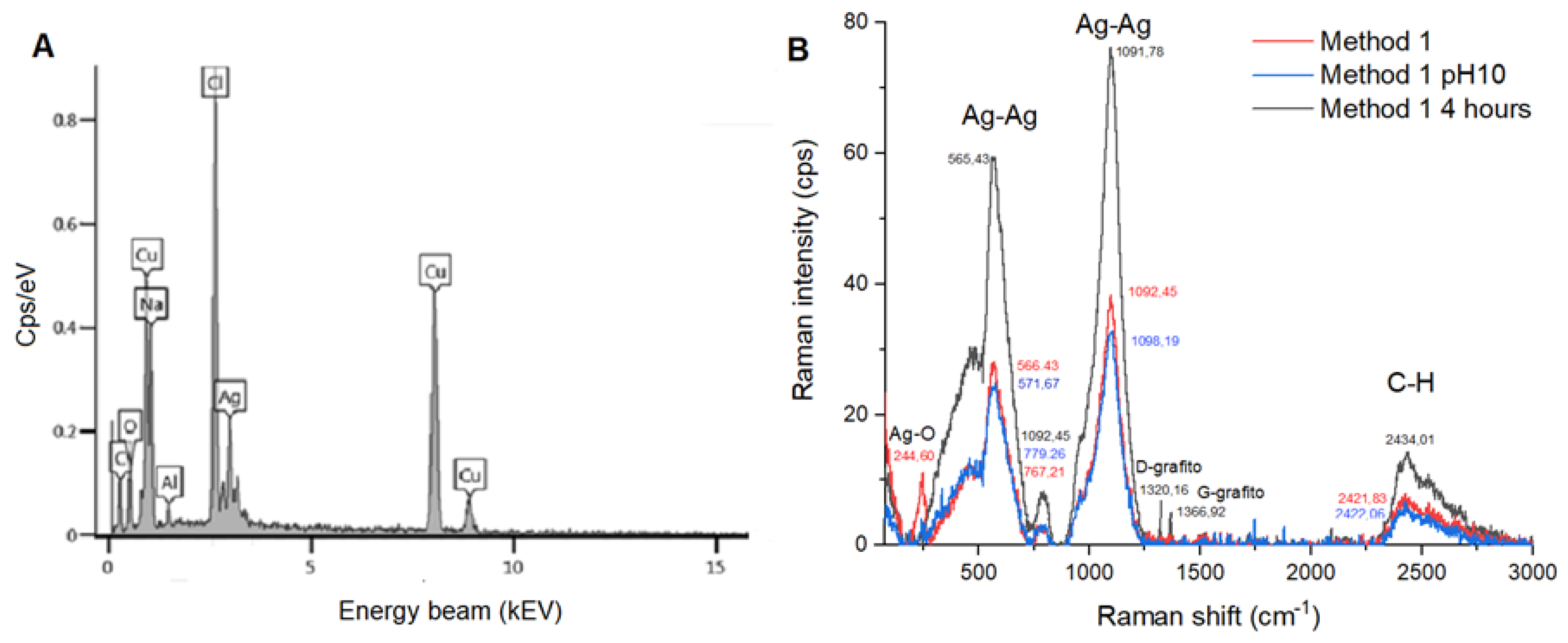

Because method 1 produce more homogeneous and smaller AgNPs, a sample produced with this method was chosen to be characterized by EDX. The EDX analysis (

Figure 6A) provides a detailed elemental composition of AgNPs. The sample contained 32% oxygen, sodium at 31%, 3% aluminum, 17% copper, 11% chlorine, and 3% of silver. The elemental composition is complemented with the Raman Spectroscopy results (

Figure 6B) where the spectra of samples synthesized with method 1, method 1 at pH 10, and method 1 under 4 hours at 1.75 MPa of pressure were analyzed. The Raman spectra confirm the presence of Ag-Ag metallic bonds, C-H bonds and Ag-O bonds. Notably, for the AgNPs exposed to 4 hours of high pressure, C-C bonds were observed.

3. Discussion

4.1. Influence of the Synthesis Method on the Plasmonic Properties of AgNPs

The monitoring over time of AgNPs synthesized with method 1 shows a greater stability of nanoparticles than AgNPs synthetized with method 2, where an increase in the signal intensity occurs, suggesting that the AgNPs slightly agglomerate over time. In method 2 is observed that as time passes, a shift of the SPR occurs, attributed not only to the agglomeration of the nanoparticles, but also to the formation of reactive forms of silver, such as the Ag+ ion. Apparently, the dynamics of the AgNO3 reduction reaction is different between the two methods. In method 1, the addition of the mixture of NaBH4 and Na-cit to the AgNO3 solution favors the reduction of the AgNPs in a controlled manner, producing smaller, more uniform and stable AgNPs. In method 2, the mixture of AgNO3 with sodium citrate could cause an uncontrolled reduction when adding NaBH4, due to the reducing effect of sodium citrate [

43] producing a greater heterogeneity in the size and shape of the NPs (

Figure 4B). This variability in morphology would contribute to a mild aggregation and an increase in the maximum of the SRP over time [

44].

4.2. Influence of pH on the Plasmonic Properties of Silver Nanoparticles

Regarding the pH effect on AgNPs synthesis, at pH 4,0 (

Figure 2A) no SPR peak was detected. This finding suggests that the pH of the reaction medium interferes with the formation and/or stability of the AgNPs nucleation and it is no dependent on the method. The absence of a SPR peak at pH 4,0 suggests that the acidic environment interferes with the formation and stability of AgNPs, indicating that low pH conditions may slow down the reduction rate of silver nitrate, thereby altering the kinetics of AgNPs synthesis. This observation is consistent with previous studies that have shown how acidic conditions can affect the reduction process and the resulting nanoparticle characteristics [

45].

At pH 7,0 (

Figure 2B) no SPR peak was found in the UV-Vis spectrum with both methods either. Considering that the synthesis of AgNPs in water (neutral pH) resulted in a defined SPR, it could be assumed that the ionic strength generated by the 20 mM phosphate buffer solution at pH 7,0 could be interfering with the reduction of AgNO3 or nucleation of AgNPs, highlighting the critical role of buffer composition and concentration in the synthesis process.

Regarding the synthesis at pH 10,0, it is observed that method 1 (

Figure 2C) produces a more intense peak of the SPR compared to method 2 (

Figure 2D) and to method 1 in water (

Figure 1A), suggesting a higher efficiency in the synthesis of AgNPs in alkaline medium. In addition, the SPR presented a shift of +22 nm in contrast to method 1 in water. Time-course monitoring of AgNPs shows a great stability for both methods, with method 1 maintaining a higher SPR intensity than method 2.

At pH 10,0, the presence of a more intense SPR peak with method 1 compared to method 2 and method 1 in water, indicates that an alkaline environment enhances the synthesis efficiency of AgNPs. The observed shift in SPR (>22 nm) suggests changes in the size and morphology of the nanoparticles, attributable to the higher reduction rate of silver nitrate in basic conditions. These results demonstrate that the efficiency of AgNPs synthesis is method-dependent, with method 1 showing higher SPR intensity and stability compared to method 2. Xiao et al. [

44] have suggested that pH conditions exert a significant impact on the size and stability of AgNPs, with higher pH values favoring the stability and growth of nanoparticles.

4.3. Influence of Pressure on the Plasmonic Properties of Silver Nanoparticles

In the 0 h treatment, a shift in SPR peak of +18 nm was found and AgNPs presented a great stability one day and 28 days after treatment, suggesting that the pressure applied after synthesis promoted the formation of stable and well-defined structures. The 4 h treatment presented also a +18 nm shift in SPR but led to a higher absorbance and a decrease in SPR intensity over time, indicating potential instability or morphological changes.

For the 23 h treatment the SPR presented a shift of +19 nm and an increase in the plasmon peak showed in

Figure 3C, which indicates that an increased consolidation or growth of the nanoparticles occurred. The shift in SPR may be caused by changes in the crystal structure or by the agglomeration of nanoparticles. Previous findings have shown that the application of high pressures on nanoparticles induces significant changes in their morphology and plasmon resonance, attributed to recrystallization or changes in the crystal structure due to rearrangement of atoms under high pressure [

47]. The observed shift in the SPR maximum following pressure treatment indicates significant alterations in the optical properties of the AgNPs. These observations are consistent with prior research, which shows that high pressure can induce significant changes in nanoparticle morphology and optical properties through recrystallization or atomic rearrangement [

48].

The SRP and their corresponding FWHM values summarized in

Table 1 for pH, method and pressure treatments shows how methods 1 and 2 present the lower FWHM, indicating a sharper SPR than pressure treatment or at alkaline pH. Despite this, the SPR has a higher peak when AgNPs are subjected to pressure and pH of 10,0. The FWHM is a measure of sharpness of the SPR, which in turn is related to NPs diameter and the precision of shift determination in the SPR peak, leading to a higher sensitivity in detecting molecular binding events on the NPs surface [

49]. According to this, pressure and pH treatment suppose an interesting way to modify or synthetize AgNPs, because of their higher SRP peak, and an acceptable sharpness.

4.4. Characterization of the Size and Functional Groups of Silver Nanoparticles

STEM images allowed us to confirm that uncontrolled reduction of AgNO3 caused by the mixture with Na-cit produce larger particles with method 2. In the same way, the shift caused by method 1 at pH 10 is caused by the larger size of NPs. In this respect, the development of three different synthesis methods allowed us to control the size and distribution of AgNPs, producing very small AgNPs with method 1, followed by method 2 and the largest NPs with method 1 at pH 10.0. The advantage of produce large AgNPs with the higher SPR peak and an acceptable FWHM is related to the advantage of produce AgNPs with larger diameters, favoring the number of capping molecules, with the disadvantage of restrict the access of counterions near the thiol-modified AuNP, in contrast to smaller AuNPs [

37,

38].

Although AgNPs size increases according the method applied, the use of ultrasound energy promotes the production of small particles in the case of method 1, and allowed the control of size in method 2, because of the Na-cit reducing effect. These insights highlight the importance of utilizing ultrasound as a rapid and cost-effective method for synthesizing silver nanoparticles, as it is employed for biological synthesis of AgNPs. Ultrasound offers an efficient means to control particle size and distribution while minimizing synthesis time and cost. This technique provides a valuable alternative for producing AgNPs with precise characteristics, ensuring high quality and performance for a range of applications. The integration of ultrasound in the synthesis process not only enhances the feasibility of nanoparticle production but also supports the development of scalable and economically viable nanotechnology solutions.

In the same way, the heat treatment for 0 h produced a range of sizes of 23 ± 9 nm, suggesting that the size of the nanoparticles is affected due to the exerted pressure of 1,75 MPa and the exposure time, in comparison to water synthesis, suggesting that the size of the nanoparticles is affected due to the exerted pressure of 1,75 MPa and the exposure time. Note that before subjecting the AgNPs to the hydrothermal process, the average size is small (6 nm), but after pressure exposure, the size of AgNPs increases (17 nm). According to these results, prolonged pressure at 1,75 MPa allows the production of very uniform AgNPs of larger size compared to method 1 and method 2 synthesis at atmospheric pressure. Cristal formation was also observed for 4 and 23 hours of pressure exposure. Thereby, the increase in time exposure to pressure allows the formation of more homogeneous and larger AgNPs.

The influence of pressure on larger size of AgNPs and uniform morphology can be influenced by different factors. Apparently, the nucleation and growth of AgNPs is favored and influenced by constant pressure. In consequence, morphology of AgNPs is be more uniform and size distribution is narrower. A sustained pressure for a prolonged period has a synergistic effect on growth of the nanoparticles as observed in the increase in size from 0 to 23 hours. Yang et al. [

48] found that hydrothermal synthesis of AgNPs at 100°C for 6 hours produce spherical particles of 15 nm on average, but synthesis for 12 hours produced irregular particles of 10-40 nm. Increasing the temperature to 180°C for 6 hours produce truncated triangular nanosheets meanwhile for 12 hours disk-like nanoparticles were obtained. Viet Quang et al. [

49] report the presence of rods and plates, but the use of chitosan as dispersant apparently aggregate AgNPs when subjected to hydrothermal treatment at 100°C and 150°C.

Integrating these findings with the observed variations in size, pressure treatment significantly impacts both the size and uniformity of AgNPs as well as their chemical composition and structural characteristics. The presence of graphite, coupled with changes in elemental composition, illustrates the complex effects of pressure on the synthesis of nanoparticles. This complex interplay between physical conditions and chemical composition affects critical aspects such as the SPR shift, which reflects alterations in the nanoparticle’s electronic environment. For instance, the observed SPR shift of +20 nm with pressure treatment indicates notable changes in the electronic structure and morphology of the AgNPs, which are directly related to the formation of more uniform and larger particles. The impact of pressure on AgNPs not only underline the requirement of optimal synthesis parameters to achieve specific nanoparticle properties, but also emphasizes the critical role of such optimization for diverse applications. In fields such as catalysis, the size, the shape, and the chemical environment of nanoparticles are pivotal for their efficiency and effectiveness. Understanding and controlling these parameters enable researchers to tailor AgNPs for enhanced performance in various applications, from environmental sensing to advanced materials.

Finally, the elemental composition of AgNPs showed the presence of oxygen and sodium, which corroborate the presence of sodium citrate and sodium borohydride used in AgNPs synthesis and probably in some degree the oxidation of the nanoparticles. Copper and aluminum found are related to the matrix on which the sample was analyzed, meanwhile chlorine is derived from ammonium chloride in the buffer solution. Silver constitutes only 3% of the total composition, reflecting the relative abundance of the silver nanoparticles within the sample. The Raman Spectroscopy confirmed the presence of silver nanoparticles, because of the Ag-Ag bonds found, and confirmed the presence of sodium citrate (organic stabilizers) because the C-H bonds from methyl groups. Additionally, the detection of Ag-O bonds suggests that the nanoparticles have undergone a mild oxidation. C-C bonds detected indicates the formation of graphite in its two forms—D-graphite (amorphous) and G-graphite (ordered). This formation of graphite is a result of the high-pressure environment affecting the carbon components of citrate, leading to a more complex and ordered carbon structure.

4. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of Nanoparticles

Synthesis of AgNPs was carried out with two different methods: in method 1, 50 mL of a mixture of NaBH4 1,85 mM and sodium citrate (Na-cit) 1,85 mM was added to 50 mL of a solution of AgNO3 0,93 mM at a flow rate of 16 ml/min and a temperature of 12 °C in constant sonication of the mixture for 3 min at a frequency of 20 kHz (Elmasonic S S30H, Singen, Germany). Reaction was performed with a UP400St sonotrode (Hielscher Ultrasonics, Teltow, Germany) at 60% amplitude (A) and a pulse cycle (C) of 90%. In method 2, the same concentrations are used but the NaBH4 solution is dropped to the mixture of AgNO3 and Na-cit.

2.2. Evaluation of the pH Effect

To evaluate the effect of pH, the synthesis was carried out according to methods 1 and 2 in three pH conditions: at pH 4,0 in a citrate buffer solution 20 mM, at pH 7,0 in a phosphate buffer solution 20 mM and at pH 10,0 in an ammonium buffer solution 20 mM. The synthesis is carried out under the same conditions of temperature, dropping rate and temperature previously described. Both the solution in the reactor and the solution that is dropped are prepared in the same buffer solution.

2.3. Evaluation of the Effect of Pressure

To determine the effect of pressure, 35 mL of AgNPs synthesized with method 1 are subjected to a pressure of 1,75 MPa for 0, 4 or 23 h in a solvothermal reactor (what is known as synthesis by hydrothermal process) at a temperature of 200 °C. At the end of the experiment, the solvothermal reactor was let to cool for 12 hours and the SPR samples was checked by UV/Vis.

2.4. Characterization of Materials

To check the SPR of synthetized AgNPs, a 1:6 dilution of the sample was done and a spectral scan from 300 to 700 nm with a step size of 1 nm was carried out on a UV/Vis spectrophotometry (Spectroquant® Prove 600 spectrophotometer). To characterize the morphological characteristics of the synthetized AgNPs, a Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (STEM) was conducted by using a TESCAN FE-SEM LYRA3 operated on a range of 500 nm, with a voltage of 30 kV and a magnification of 200 kx. The chemical composition of the samples was acquired through an integrated X-ray Energy Dispersion Spectroscopy (EDX) microanalysis system, enabling the identification of chemical elements in the samples and their relative percentages. For sample preparation, the nanoparticles were dispersed in water for 10 min using an ultrasonic bath, then a single drop of this suspension was poured onto a Lacey carbon-supported copper TEM grid and finally dried under vacuum. Raman analysis was carried out on a Horiba Jobin Yvon LabRam HR800 Raman spectrometer. This spectrometer is equipped with a 532 nm laser and a 900 lines/mm diffraction grating. The experimental conditions were as follows: a 60-second exposure time, two acquisitions, and 512 background acquisitions. The laser operated at a power of 8.0 mW, and the spectrometer aperture was set to 50 µm.

5. Conclusions

The synthesis of AgNPs is significantly influenced by different parameters, including the synthesis method, the pH, and the pressure. The choice of a synthesis method, particularly the use of dispersants with reducing properties, plays a crucial role in determining the size distribution of AgNPs. In this study, it was found that the combination of AgNO3 with sodium citrate (a dispersant with reducing capabilities) facilitates the production of AgNPs with a broad range of sizes. This is due to the dual role of sodium citrate in both reducing the precursor and stabilizing the nanoparticles, followed by the addition of sodium borohydride (NaBH4) as a secondary reducing agent. The pH of the reaction medium also impacts AgNPs synthesis. At acidic pH (<7.0), the formation of AgNPs is hindered by the presence of salts and the low reduction rate of the precursor. Conversely, alkaline conditions (pH > 7.0) promote the formation of larger AgNPs, with diameters exceeding the nanometric scale, as observed in the synthesis at pH 10.0. This is reflected in the shift of the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) peak, indicating changes in the optical properties of the nanoparticles.

Pressure treatment further affects the synthesis of AgNPs, with high pressures and prolonged exposure times leading to an increase in nanoparticle size and a significant shift in SPR. This suggests that pressure can be used to optimize the size and uniformity of AgNPs, enhancing their morphological and optical characteristics. Additionally, this study emphasizes the utility of ultrasonic methods as a rapid and cost-effective alternative for synthesizing AgNPs. Ultrasonic synthesis offers precise control over particle size and distribution, reducing both synthesis time and cost, and thereby providing an efficient pathway for the scalable production of high-quality nanoparticles.

These findings highlight the importance of carefully controlling synthesis parameters to tailor the properties of AgNPs for specific applications. Manipulating pH and pressure provides a means to optimize the morphological and optical properties of AgNPs, which is essential for maximizing their catalytic activity and effectiveness across various applications.

As we discussed previously, the morphological changes in size and shape of the NPs have important implications on their properties, as the biological cytotoxicity. In the same way, pressure can also affect the solubility and stability of chemical intermediates (such as silver - citrate complexes), promoting a more controlled nucleation and less aggregation [

50]. The crystal formation observed at 4 and 23 hours suggests that prolonged pressure not only stabilizes the spherical nanoparticles but also facilitates the formation of more ordered crystalline structures. The observed increase in size and uniformity under pressure suggests that constant pressure promotes nucleation and growth, leading to a tighter size distribution and more uniform morphology. Prolonged pressure has a synergistic effect on nanoparticle growth, as noted in previous studies. Additionally, changes in size and morphology have significant implications for properties such as biological cytotoxicity, solubility, and stability of chemical intermediates. The observed crystal formation at 4 and 23 hours further implies that sustained pressure not only stabilizes spherical nanoparticles but also facilitates the formation of more ordered crystalline structures.

For future experiments, higher and discrete pressure conditions would complement the result obtained on this work, highlighting the importance of these variables on AgNPs size and morphology. Also, the synthesis of AgNPs at the same pH but without salts presence in the reaction mixture would confirm the effect of salts on AgNPs synthesis. Finally, the use of combined variables and the use of different dispersants would develop a more complex strategy for the synthesis of AgNPs, not only with different sizes, bur with different morphological shapes in addition to the spherical morphology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Daniel Llamosa.; methodology, Daniel Llamosa, Jahaziel Amaya.; validation, Daniel Llamosa.; formal analysis, Daniel Llamosa, Jahaziel Amaya, Hansen Murcia; investigation, Daniel Llamosa, Hansen Murcia, Paula Riascos.; resources, Daniel Llamosa, Jahaziel Amaya, Hansen Murcia.; data curation, Daniel Llamosa, Jahaziel Amaya; writing—original draft preparation, Paula Riascos, Hansen Murcia; writing—review and editing, Hansen Murcia, Paula Riascos, Jahaziel Amaya.; visualization, Daniel Llamosa, Paula Riascos; supervision, Hansen Murcia, Daniel Llamosa, Jahaziel Amaya; project administration, Hansen Murcia.; funding acquisition, Hansen Murcia, Daniel Llamosa, Jahaziel Amaya All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by Vicerrectoría de Ciencia, Tecnología e Investigación (VCTI), Universidad Antonio Nariño, Bogotá, D.C., Colombia, Convocatoria Interna 2023 “Proyectos de Ciencia, Tecnología, Innovación y Creación”, Proyecto 2023203.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank to the “Semillero de Nanomateriales and to the Semillero Estudios de Materiales y sus Aplicaciones” (EMA) and to the “Semillero Micobiotox” for all resources provided for the development of this proyect.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AgNPs |

Silver nanoparticles |

| NPs |

Nanoparticles |

| SPR |

Surface plasmon resonance |

| FWHM |

Full width at half maximum |

| AuNPs |

Gold nanoparticles |

References

- Husain, S.; Nandi, A.; Simnani, F.Z.; Saha, U.; Ghosh, A.; Sinha, A.; Sahay, A.; Samal, S.K.; Panda, P.K.; Verma, S.K. Emerging Trends in Advanced Translational Applications of Silver Nanoparticles: A Progressing Dawn of Nanotechnology. J Funct Biomater 2023, 14.

- Akhter, M.S.; Rahman, M.A.; Ripon, R.K.; Mubarak, M.; Akter, M.; Mahbub, S.; Al Mamun, F.; Sikder, M.T. A Systematic Review on Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Plants Extract and Their Bio-Medical Applications. Heliyon 2024, 10.

- Pasparakis, G. Recent Developments in the Use of Gold and Silver Nanoparticles in Biomedicine. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 2022, 14.

- Zhang, X.F.; Liu, Z.G.; Shen, W.; Gurunathan, S. Silver Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, Properties, Applications, and Therapeutic Approaches. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17.

- Nguyen, N.P.U.; Dang, N.T.; Doan, L.; Nguyen, T.T.H. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles: From Conventional to ‘Modern’ Methods—A Review. Processes 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Amendola, V.; Pilot, R.; Frasconi, M.; Maragò, O.M.; Iatì, M.A. Surface Plasmon Resonance in Gold Nanoparticles: A Review. Journal of Physics Condensed Matter 2017, 29.

- Nyabadza, A.; McCarthy, É.; Makhesana, M.; Heidarinassab, S.; Plouze, A.; Vazquez, M.; Brabazon, D. A Review of Physical, Chemical and Biological Synthesis Methods of Bimetallic Nanoparticles and Applications in Sensing, Water Treatment, Biomedicine, Catalysis and Hydrogen Storage. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2023, 321.

- Giri, A.K.; Jena, B.; Biswal, B.; Pradhan, A.K.; Arakha, M.; Acharya, S.; Acharya, L. Green Synthesis and Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles Using Eugenia Roxburghii DC. Extract and Activity against Biofilm-Producing Bacteria. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Jaast, S.; Grewal, A. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles, Characterization and Evaluation of Their Photocatalytic Dye Degradation Activity. Current Research in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2021, 4. [CrossRef]

- Liaqat, N.; Jahan, N.; Khalil-ur-Rahman; Anwar, T.; Qureshi, H. Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles: Optimization, Characterization, Antimicrobial Activity, and Cytotoxicity Study by Hemolysis Assay. Front Chem 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Nouri, A.; Tavakkoli Yaraki, M.; Lajevardi, A.; Rezaei, Z.; Ghorbanpour, M.; Tanzifi, M. Ultrasonic-Assisted Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Mentha Aquatica Leaf Extract for Enhanced Antibacterial Properties and Catalytic Activity. Colloids and Interface Science Communications 2020, 35. [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Jiménez, B.; Montoro Bustos, A.R.; Pereira Reyes, R.; Paniagua, S.A.; Vega-Baudrit, J.R. Novel Pathway for the Sonochemical Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles with Near-Spherical Shape and High Stability in Aqueous Media. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Nouri, A.; Tavakkoli Yaraki, M.; Lajevardi, A.; Rezaei, Z.; Ghorbanpour, M.; Tanzifi, M. Ultrasonic-Assisted Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Mentha Aquatica Leaf Extract for Enhanced Antibacterial Properties and Catalytic Activity. Colloids and Interface Science Communications 2020, 35. [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, A.R.; Gupta, A.; Kim, B.S. Ultrasound Assisted Green Synthesis of Silver and Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Using Fenugreek Seed Extract and Their Enhanced Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities. Biomed Res Int 2019, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Akhter, M.S.; Rahman, M.A.; Ripon, R.K.; Mubarak, M.; Akter, M.; Mahbub, S.; Al Mamun, F.; Sikder, M.T. A Systematic Review on Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Plants Extract and Their Bio-Medical Applications. Heliyon 2024, 10.

- Calderón-Jiménez, B.; Montoro Bustos, A.R.; Pereira Reyes, R.; Paniagua, S.A.; Vega-Baudrit, J.R. Novel Pathway for the Sonochemical Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles with Near-Spherical Shape and High Stability in Aqueous Media. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Anh, N.P.; Linh, D.N.; Minh, N. V.; Tri, N. Positive Effects of the Ultrasound on Biosynthesis, Characteristics and Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Using Fortunella Japonica. Mater Trans 2019, 60, 2053–2058. [CrossRef]

- Potara, M.; Gabudean, A.M.; Astilean, S. Solution-Phase, Dual LSPR-SERS Plasmonic Sensors of High Sensitivity and Stability Based on Chitosan-Coated Anisotropic Silver Nanoparticles. J Mater Chem 2011, 21, 3625–3633. [CrossRef]

- Haes, A.J.; Van Duyne, R.P. A Unified View of Propagating and Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensors. Anal Bioanal Chem 2004, 379, 920–930.

- Lorca-Ponce, J.; Urzúa, E.; Ávila-Salas, F.; Ramírez, A.M.; Ahumada, M. Silver Nanoparticle’s Size and Morphology Relationship with Their Electrocatalysis and Detection Properties. Appl Surf Sci 2023, 617. [CrossRef]

- Marciniak, L.; Nowak, M.; Trojanowska, A.; Tylkowski, B.; Jastrzab, R. The Effect of Ph on the Size of Silver Nanoparticles Obtained in the Reduction Reaction with Citric and Malic Acids. Materials 2020, 13, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Fernando, I.; Zhou, Y. Impact of PH on the Stability, Dissolution and Aggregation Kinetics of Silver Nanoparticles. Chemosphere 2019, 216, 297–305. [CrossRef]

- Ajitha, B.; Ashok Kumar Reddy, Y.; Sreedhara Reddy, P. Enhanced Antimicrobial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles with Controlled Particle Size by PH Variation. Powder Technol 2015, 269, 110–117. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lenhart, J.J.; Walker, H.W. Aggregation Kinetics and Dissolution of Coated Silver Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2012, 28, 1095–1104. [CrossRef]

- Kazim, S.; Jäger, A.; Steinhart, M.; Pfleger, J.; Vohlídal, J.; Bondarev, D.; Štěpánek, P. Morphology and Kinetics of Aggregation of Silver Nanoparticles Induced with Regioregular Cationic Polythiophene. Langmuir 2016, 32, 2–11. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Liu, Y.L.; Stallworth, A.M.; Ye, C.; Lenhart, J.J. Effects of PH, Electrolyte, Humic Acid, and Light Exposure on the Long-Term Fate of Silver Nanoparticles. Environ Sci Technol 2016, 50, 12214–12224. [CrossRef]

- Koski, K.J.; Kamp, N.M.; Smith, R.K.; Kunz, M.; Knight, J.K.; Alivisatos, A.P. Structural Distortions in 5-10 Nm Silver Nanoparticles under High Pressure. Phys Rev B Condens Matter Mater Phys 2008, 78. [CrossRef]

- Iravani, S.; Korbekandi, H.; Mirmohammadi, S. V; Zolfaghari, B. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles: Chemical, Physical and Biological Methods. Res Pharm Sci 2014, 9, 385–406.

- Arris, F.A.; Benoudjit, A.M.; Sanober, F.; Wan Salim, W.W.A. Characterization of Electrochemical Transducers for Biosensor Applications. In Multifaceted Protocol in Biotechnology; Springer Singapore, 2018; pp. 119–137 ISBN 9789811322570.

- Menichetti, A.; Mavridi-Printezi, A.; Mordini, D.; Montalti, M. Effect of Size, Shape and Surface Functionalization on the Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles. J Funct Biomater 2023, 14.

- Lee, C.L.; Tsai, Y.L.; Huang, C.H.; Huang, K.L. Performance of Silver Nanocubes Based on Electrochemical Surface Area for Catalyzing Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Electrochem commun 2013, 29, 37–40. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.L.; Coronado, E.; Zhao, L.L.; Schatz, G.C. The Optical Properties of Metal Nanoparticles: The Influence of Size, Shape, and Dielectric Environment. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2003, 107, 668–677. [CrossRef]

- Mahmudin, L.; Wulandani, R.; Riswan, M.; Kurnia Sari, E.; Dwi Jayanti, P.; Syahrul Ulum, M.; Arifin, M.; Suharyadi, E. Silver Nanoparticles-Based Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor for Escherichia Coli Detection. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc 2024, 311. [CrossRef]

- Evanoff, D.D.; Chumanov, G. Synthesis and Optical Properties of Silver Nanoparticles and Arrays. ChemPhysChem 2005, 6, 1221–1231.

- Zahran, M.; Khalifa, Z.; Zahran, M.A.H.; Abdel Azzem, M. Recent Advances in Silver Nanoparticle-Based Electrochemical Sensors for Determining Organic Pollutants in Water: A Review. Mater Adv 2021, 2, 7350–7365.

- Javed, R.; Zia, M.; Naz, S.; Aisida, S.O.; Ain, N. ul; Ao, Q. Role of Capping Agents in the Application of Nanoparticles in Biomedicine and Environmental Remediation: Recent Trends and Future Prospects. J Nanobiotechnology 2020, 18.

- Farcas, A.; Janosi, L.; Astilean, S. Size and Surface Coverage Density Are Major Factors in Determining Thiol Modified Gold Nanoparticles Characteristics. Comput Theor Chem 2022, 1209. [CrossRef]

- Geißler, D.; Nirmalananthan-Budau, N.; Scholtz, L.; Tavernaro, I.; Resch-Genger, U. Analyzing the Surface of Functional Nanomaterials-How to Quantify the Total and Derivatizable Number of Functional Groups and Ligands. Microchimica Acta 2021, 321. [CrossRef]

- Hennig, A.; Borcherding, H.; Jaeger, C.; Hatami, S.; Würth, C.; Hoffmann, A.; Hoffmann, K.; Thiele, T.; Schedler, U.; Resch-Genger, U. Scope and Limitations of Surface Functional Group Quantification Methods: Exploratory Study with Poly(Acrylic Acid)-Grafted Micro- and Nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc 2012, 134, 8268–8276. [CrossRef]

- Leubner, S.; Hatami, S.; Esendemir, N.; Lorenz, T.; Joswig, J.O.; Lesnyak, V.; Recknagel, S.; Gaponik, N.; Resch-Genger, U.; Eychmüller, A. Experimental and Theoretical Investigations of the Ligand Structure of Water-Soluble CdTe Nanocrystals. Dalton Transactions 2013, 42, 12733–12740. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Pan, J. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles by Sodium Alginate and Their Applications in Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering and Catalysis. Acta Mater 2012, 60, 4753–4758. [CrossRef]

- Viet Quang, D.; Hoai Chau, N. The Effect of Hydrothermal Treatment on Silver Nanoparticles Stabilized by Chitosan and Its Possible Application to Produce Mesoporous Silver Powder. Journal of Powder Technology 2013, 2013, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Merga, G.; Wilson, R.; Lynn, G.; Milosavljevic, B.H.; Meisel, D. Redox Catalysis on “Naked” Silver Nanoparticles. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2007, 111, 12220–12226. [CrossRef]

- Wojtysiak, S.; Kudelski, A. Influence of Oxygen on the Process of Formation of Silver Nanoparticles during Citrate/Borohydride Synthesis of Silver Sols. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2012, 410, 45–51. [CrossRef]

- Alqadi, M.K.; Abo Noqtah, O.A.; Alzoubi, F.Y.; Alzouby, J.; Aljarrah, K. PH Effect on the Aggregation of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized by Chemical Reduction. Materials Science- Poland 2014, 32, 107–111. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Lei, W.; Gong, M.; Xin, H.L.; Wang, D. Recent Advances of Structurally Ordered Intermetallic Nanoparticles for Electrocatalysis; 2018;

- Christofilos, D.; Assimopoulos, S.; Del Fatti, N.; Voisin, C.; Vallèe, F.; Kourouklis, G.A.; Ves, S. High Pressure Study of the Surface Plasmon Resonance in AG Nanoparticles. In Proceedings of the High Pressure Research; Taylor and Francis Inc., 2003; Vol. 23, pp. 23–27.

- Wu, H.; Wang, Z.; Fan, H. Stress-Induced Nanoparticle Crystallization. J Am Chem Soc 2014, 136, 7634–7636. [CrossRef]

- Nocerino, V.; Miranda, B.; Dardano, P.; Sanità, G.; Esposito, E.; De Stefano, L. Protocol for Synthesis of Spherical Silver Nanoparticles with Stable Optical Properties and Characterization by Transmission Electron Microscopy. STAR Protoc 2024, 5. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xia, Y. Shape-Controlled Synthesis of Gold and Silver Nanoparticles. Sience 2002, 298, 2176–2179.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).