1. Introduction

In the past few years, metal nanoparticles have garnered the attention of researchers due to their extraordinary potential applications. The production of metallic nanoparticles has been achieved through a variety of chemical methods, including physical–chemical reduction [

1,

2] chemical reduction with both organic [

3,

4] and inorganic reagents [

5,

6], condensation, and evaporation [

7,

8]. Recently, laser ablation has garnered substantial attention in addition to the chemical routes for nanoparticles fabrication [

9,

10,

11]. This technique enables the fabrication of a large variety of nanoparticles both in colloids [

12], and under vacuum conditions [

13,

14,

15]. For the past few years, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) have been investigated for their microbicidal properties, which are more effective than those of other metal nanoparticles [

16]. Numerous studies have demonstrated their efficacy against a variety of pathogens [

17,

18,

19]. A key feature of AgNP’s is the Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), a phenomenon caused by the coherent oscillation of the free electrons in response to an external electromagnetic field such as light. This resonance generates a strong electric field surrounding the nanoparticle which can result in a variety of effects, such the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), the ejection of “bullet-like” atoms or clusters, and an increase in light absorption, all of which contribute to their microbicidal activity [

20,

21,

22]. Despite their promising properties, AgNP commonly face challenges related to instability and reactivity in aqueous media, limiting their practical applications. To overcome these issues, AgNPs are often coated with stabilizing materials that reduce core reactivity without compromising their optical properties in this regard, silicon dioxide (SiO

2) has emerged as a noble coating material due to its chemical stability, transparency, and easy of synthesis [

23].

A two-step process that integrates laser ablation and redox reactions has been employed to synthesize silica-coated silver nanoparticles (Ag@SiO

2 NPs)[

24]. The initial step involves the laser ablation of a silicon target while submerging in water. This process produces silicon nanoparticles that oxidize rapidly, resulting in the formation of a colloid of H

2O-SiO

2 nanoparticles. In the subsequent step, silver ions are introduced into the colloid resulting in the formation of silver nanoparticles that are coated by a silica shell (and thus producing Ag@SiO

2 NPs [

25,

26]. The optical, structural, and photo-induced microbicidal properties of these Ag@ SiO

2 nanoparticles have been reported to be effective against both human bacteria [

27] and phytopathogens [

28].

During laser ablation in addition to nanoscale SiO2 particles, larger micro and submicron-sized silicon particles are also generated due to the laser shock wave-induced fragmentation of target surface. These large particles do not fully oxidize in water and precipitate within minutes, affecting colloid stability and coating uniformity. To address this challenge, the present study introduces a modification involving an additional laser irradiation step applied to the as-prepared H2O-SiO2 colloid. This secondary treatment further fragments the larger silicon particles, enhancing the homogeneity and stability of the colloid, to evaluate both structural and electrophoretic properties.

An additional critical component of enhancing microbicidal efficacy is the regulation of electrostatic interactions between microorganisms and nanoparticles. Subsequently, to facilitate electrostatic interaction, nanoparticles must include neutral or positive surface charges [

29]. Antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles coated with silicon dioxide is substantial against bacterial strains, including both Gram-Positive and Gram-negative species. Electrostatic interactions between the positively charged or neutrally stabilized Ag@SiO

2 nanoparticles and the negatively charged bacterial cell wall promote adhesion to the microbial surface. The silica coating ensures a high surface area, available for interaction by enhancing nanoparticles stability and preventing agglomeration [

30]. The microbial efficacy is primarily attributed to both the plasmonic effect and the release of Ag

+ ions from the silver core, which could bind to sulfur and phosphorous-containing biomolecules within the bacterial membrane and intracellular environment. This behavior disrupts membrane integrity and inhibits critical metabolic processes. So far, the nanoparticles high surface area enables them to establish a close relationship with bacterial membrane, thereby enhancing these effects. Silver exposure can be optimized to enhance antimicrobial performance through optimizations of the silica shell and taking advantage of the surface plasmon resonance. Ag@SiO

2 nanoparticles are promising candidates for applications in antimicrobial coatings and therapies due to their exceptional bactericidal mechanisms and physicochemical stability.

Moreover, certain microorganisms such as fungi, can attain sizes of tens of microns, necessitating the controlled agglomeration of nanoparticles to facilitate effective treatment coverage. The surface charge can be modulated the pH and adding salts varying concentrations (8x10

-5- 10

-1M) [

31,

32]. To achieve optimal interactions between microorganisms and nanoparticles, the electrophoretic properties of Ag@SiO

2 nanoparticles were examined in a solution of AlCl

3 salt. Since AlCl

3 serves as a critical auxiliar agent that significantly enhances colloidal stability, even though silica layer is the source of the primary stabilization effect [

33,

34].

The aim of this research is to fully understand the mechanistic role of AlCl3 in modulating surface chemistry in core-shell nano systems such as SiO2-coateed nanoparticles for microbicidal applications which represents a promising platform for applications requiring long-term nanoparticle stability, and the prudent use of aluminum salts is key controlling their physiochemical properties.

2. Materials and Methods

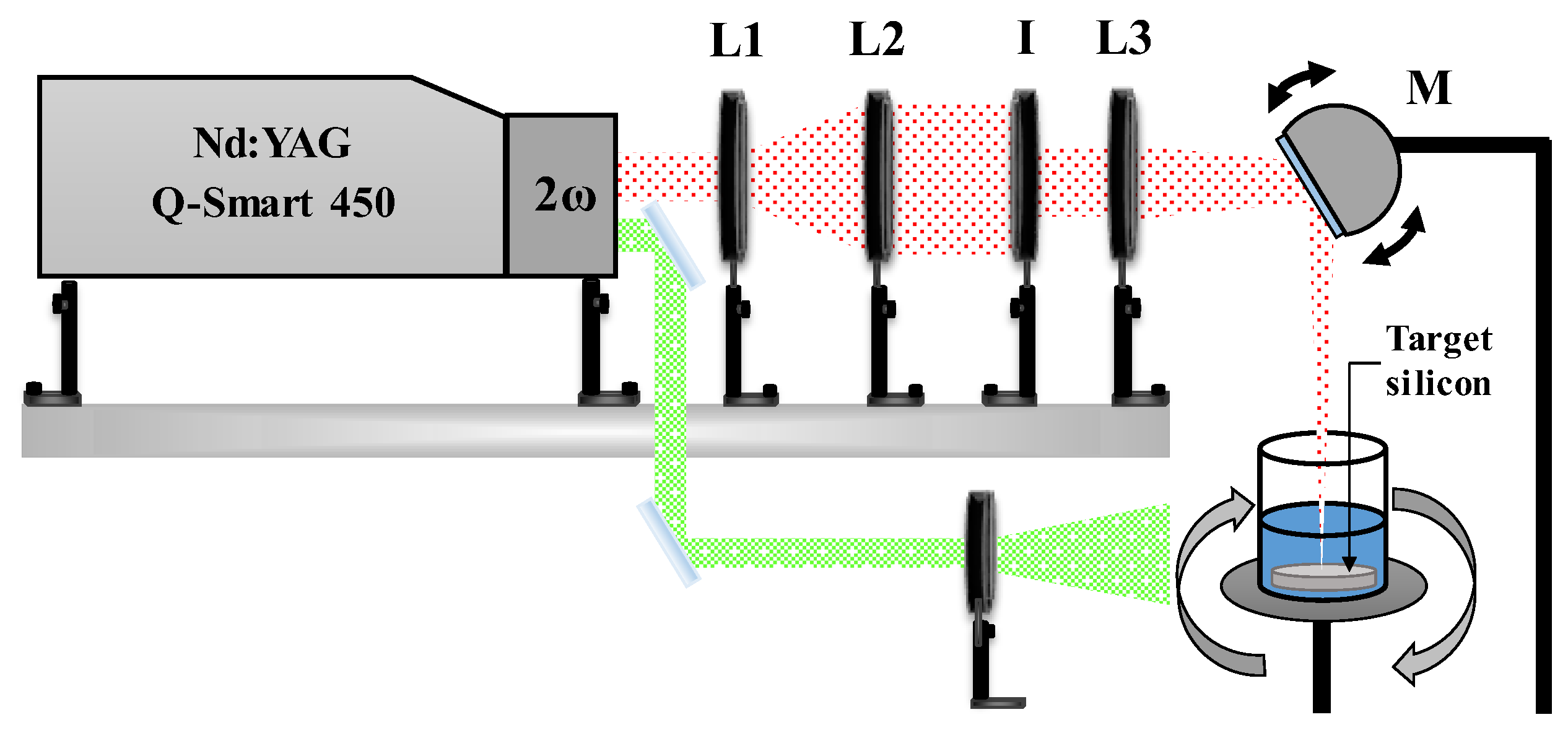

The Laser ablation and irradiation were carried out using a pulsed laser (Nd: YAG, Q-Smart 450) operating in Q-Switch mode. The laser is equipped with a harmonic generator with automatic phase correction and operates at a frequency of 20 Hz, delivering 5 ns pulses, with maximum pulse energies of 450 mJ, 200 mJ, and 100 mJ for the first (λ = 1064 nm), second (λ = 532 nm), and third (λ = 355 nm) harmonics, respectively. For the fabrication process, only the first and second harmonics were employed.

Optical properties of samples were studied through UV-VIS spectroscopy within a range of 200 to 800nm using a UV-VIS Cary 500 Agilent spectrophotometer. The structural properties of SiO2-H2O colloids and Ag@SiO2 NPs were studied by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Brucker Advance D8 diffractometer. Colloidal solution was dropped onto a glass plate until it formed a film thick enough to be detected by X-ray. Diffractograms were acquired using the grazing incidence mode within the 20°<2θ < 70° range, and the most intense signals were indexed. TEM and HRTEM micrographs were acquired with a JEOL JEM2100 microscope at 200 kV. Zeta Potential and Hydrodynamic Diameter were measured using a Litesizer 500 particle analyzer from Anton Paar. The pH measurements used to determine the isoelectric point were made with a high-accuracy pH hand tester (HI98130) from Hanna Instruments. Colloidal SiO2 was measured to evaluate the influence of the irradiation process and Ag@SiO2 NPs were measured before and after adding different AlCl3 concentrations to determine its influence on the nanoparticle’s surface charge and agglomeration.

Experimental System

Ag@SiO

2 NPs were synthesized with a novel physicochemical method that combines laser ablation and oxidation-reduction mechanisms. A schematic representation of the experimental setup used for laser ablation is illustrated in

Figure 1. Laser radiation is focused onto the target surface using a converging lens (L3, f3 = +30 cm) and a motorized reflective mirror (M). The mirror oscillates at a fixed frequency (~2 Hz), enabling the focused beam to scan along the central axis of the target. The silicon target is positioned at the bottom of a beaker containing 20 ml of solvent, in this case, HPLC water.

The beaker is rotated around its central axis at ≈ 60 rpm. This combination of both movements (beam sweeping and container rotation) enables nearly uniform ablation of the target’s surface thereby mitigating the crater formation resulting from multiple pulses impacting the same point on the target’s surface.

The spot size at the lens focal point was measured using an optical microscope, yielding a diameter of 1 mm. Consequently, the energy density (fluence) at the target surface was calculated based on the pulse energy utilized, resulting in a value of 3.8 J/cm2 for a pulse energy (EP) of 30 mJ.

The pulse energy was regulated using a metallic iris (I). The laser beam was previously expanded (3x) using a lens arrangement (L1, f1 = -10 cm; L2, f2 = +30 cm) to prevent damage to the iris surface from the laser radiation. Finally, the energy that reaches the target’s surface was calibrated by adjusting the iris aperture. Before every synthesis process, the energy incident on the material surface was measured with a power meter (Ophir Nova II) equipped with a pyroelectric sensor (PE25BF-DIF-C).

Physical Process: Laser Ablation

The SiO

2 nanoparticles were generated by irradiating a silicon target with first harmonic radiation (λ = 1024 nm) at room temperature (27 °C) for 5 minutes. Micro and nanoparticles of silicon are generated as a result of each pulse ablation of the target surface. These particles undergo wet oxidation, which commences from the outside when they come into contact with water [

35], as demonstrated by the following chemical equation:

The oxidation reaction is exothermic, also the high temperatures in the plasma produced during ablation facilitates the oxidation and fragmentation of the silicon particles. Nevertheless, certain micrometric or larger particles that have not undergone complete oxidation remain in the solution. In order to facilitate the complete oxidation of silicon and reduce polydispersity and particle size, the colloidal suspension undergoes an irradiation process. A divergent lens is employed to expand the diameter of the laser beam (second harmonic, λ = 532 nm) by approximately a factor of two (d = 1.4 cm). The pulse energy for the irradiation was Ep= 50 mJ, leading to a fluence of Φ

E= 200 mJ/cm

2. The colloidal was irradiated for 5 and 10 minutes under these conditions, as schematically depicted in

Figure 1. In order to guarantee uniform irradiation, the sample was continuously magnetic stirred.

The irradiation process results in the cavitation effect, which fragments larger silicon particles produced during ablation, thereby facilitating their oxidation. This research paper Results section offers evidence that this process significantly increases the concentration of nanometric silicon in the solution.

Chemical Process: Oxidation-Reduction Reactions

After preparing the colloidal suspension of nanometric silicon, 80 µL of a 50 mM aqueous AgNO

3 solution is added to a total volume of 20 mL to achieve a final silver ions concentration of 0.2 mM. Silver ions are reduced to metallic silver (Ag

0) through the production of free electrons in the solution as a result of silicon oxidation. The metallic silver atoms bond via metallic bonds to form silver nanoparticles as described in the following chemical equation [

36].

Ermakov et al. [

26] proposed that the extremely high energies associated with laser ablation could result in the formation of multiple isomers of SiO

2H

2 on the surface of these SiO

2 sub nanoparticles. The production and study of these isomers have been previously reported using electrical discharges [

37]. Silver ions may be reduced through the reaction with these SiO

2H

2 isomers (Ag

+1→Ag

0), promoting the growth of silver nanoparticles [

25].

When silver nanoparticles and SiO2 approach, their electron clouds interact, resulting a dipole moment due to the negative charge of the SiO2, (zeta potential ≈ -40 mV). This interaction promotes the formation of a SiO2 shell around the nanoparticles. The pH is neutralized, and the colloidal stability is improved by the addition of 0.1 mM of Na2CO3 at 0.1 mM to the colloid. Following the synthesis of Ag@SiO2 nanoparticles, aluminum chloride was incorporated into the colloidal solutions at final concentrations of 1×10−4 M, 1×10−3 M, and 2×10−3 M.

3. Results

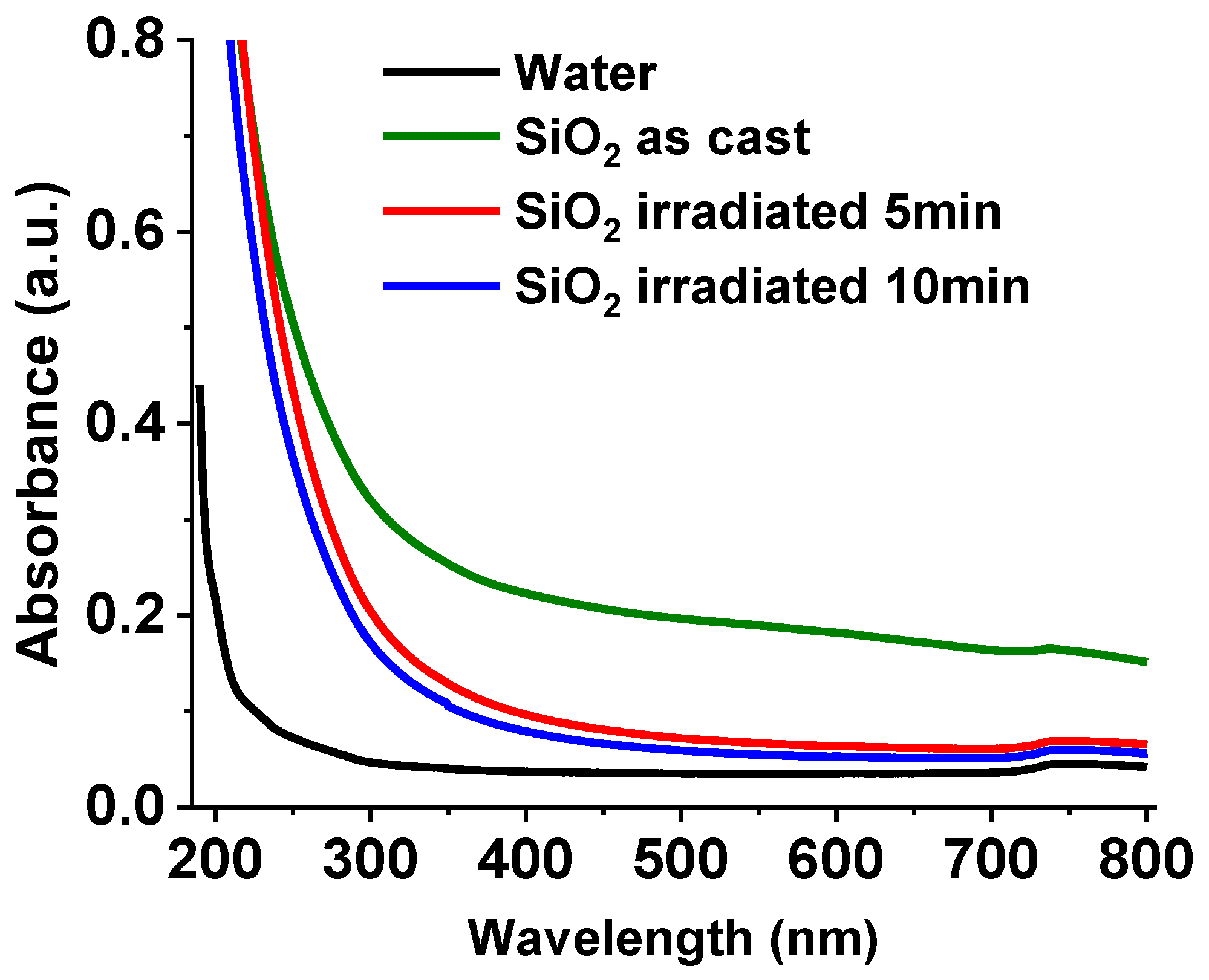

3.1. Optical Properties of Colloidal SiO2

Absorption spectra of the SiO

2 colloid obtained in the 200 to 800 nm range are depicted in

Figure 2. The spectra were measured as cast and irradiated for 5 and 10 min. Results show low absorption for all samples, as SiO

2 is transparent down to approximately 200 nm [

38]. The absorbance of the synthesized SiO

2 colloid (green line) is high in the visible to near infrared wavelength range. The behavior is believed to be the result of the scattering by particles in the solution that are comparable in size to the wavelength of the incident radiation.

During the irradiation process micrometric and submicron-sized particles are detached by the laser’s shock wave, and they begin to oxidize upon contact with water. Consequently, the absorption(scattering) is significantly reduced, particularly in the visible and near infrared regions, as can be observed for the SiO

2 colloid irradiated for 5 min (red line). This decrease is attributed to the fragmentation of larger silicon particles generated during the irradiation process [

39]. When the irradiation time increases to 10 min (blue line), the scattering further decreases, suggesting that larger particles continue to fragment.

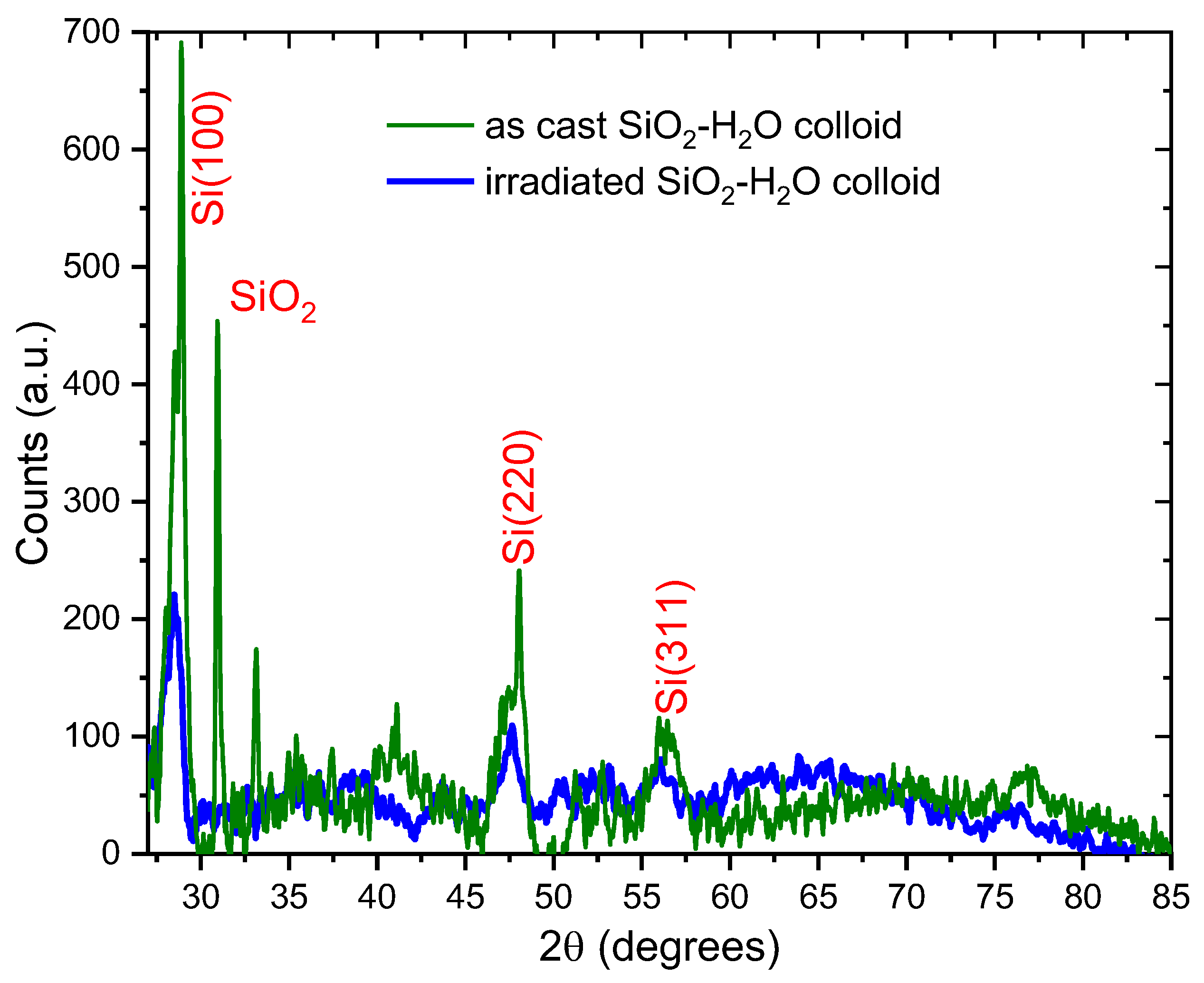

3.2. Structural Properties of SiO2-H2O Colloid by X-Ray Diffraction (XRD).

Figure 3 shows the XRD results of the SiO

2-H

2O colloid as cast (green line) and after irradiation (blue line). The diffractogram of the SiO

2-H

2O as cast reveals signals at 28°, 47°, and 56° corresponding to the (111), (220) and (311) diffraction planes of the silicon cubic structure, respectively. (PDF 027-1402), suggesting the presence of crystalline silicon particles in the colloidal SiO

2. These particles are extracted from the silicon target due to the pulse shock wave during the ablation process and do not completely oxidize to SiO

2 due to their larger size.

Using Scherrer’s formula and the signal around 28° a crystallite size of was calculated for the crystalline silicon.

Furthermore, the diffractogram for the as cast SiO2-H2O colloid exhibits a narrow signal around 31°, which corresponds to crystalline SiO2 (cristobalite, PDF 893434). The appearance of this crystalline signal could be attributed due to the high temperatures achieved at the surface of the silicon target during the laser ablation process. Using the Scherrer formula for this signal a crystallite size of 47 ±1 nm was calculated.

Diffractogram of the colloid after the irradiation process shows wider and lower signals than those observed in the as cast colloid. These signals are typical of amorphous SiO

2 [

40], suggesting the irradiation process fragments the bigger silicon particles into smaller ones, which undergo a further oxidation and produce amorphous SiO

2 at nanometer scale.

Using the Scherrer’s formula and the signal around 28° (crystalline silicon), a crystallite size of was estimated for the irradiated SiO2-H2O colloid.

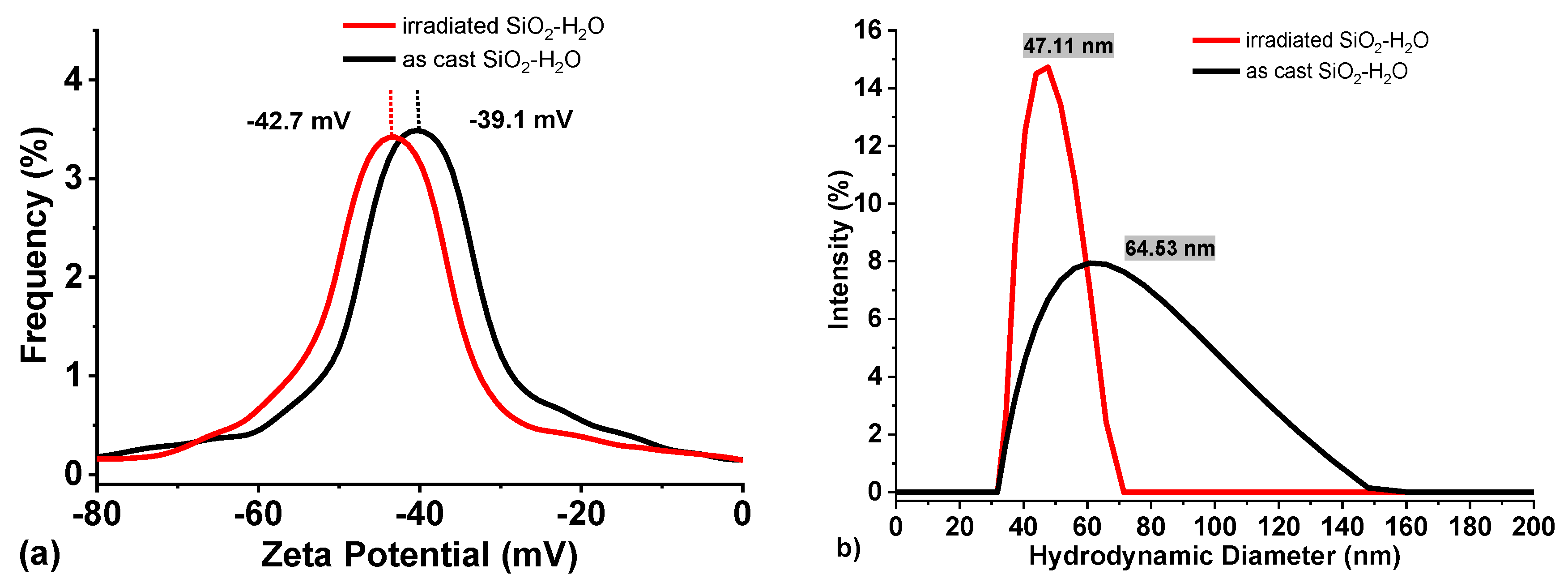

3.3. Electrophoretic Properties and pH Measurements of SiO2

Zeta Potential measurements of the as cast SiO

2-H

2O colloid and after irradiation are presented in

Figure 4(a). The average zeta potential of the as-cast colloid is approximately -39 mV, with a slight shift to more negative values (-42 mV) upon irradiation. This change suggests that laser irradiation produces smaller silicon particles, which oxidize at a faster rate, thereby increasing the concentration of nanometric SiO

2 in the colloid. Consequently, the negative zeta potential increases in magnitude as the surface charge density of SiO

2 increases [

41]. The results also indicate that irradiation increases the SiO

2 content of the colloid, which in turn increases the efficiency of reducing metal ions (Ag

+, Au

+, Cu

+, etc). It is important to note that zeta potential values exceeding ±30mV are regarded as a reliable indicator of colloidal stability [

42].

Additionally, the hydrodynamic diameter results (

Figure 4b) demonstrate the fragmentation of larger Si particles. The results demonstrate a decrease in the mean particle size (64 to 47 nm), and an increase in the signal intensity, indicating an increase in the number of smaller nanoparticles within the colloid.

Furthermore, the results reveal a significant reduction of the full width at half maximum (FWHM) for the size distribution of the irradiated colloid (black line). This suggests that the fragmentation of larger particles resulted in the formation of particles with a narrower size distribution. It is important to mention that the hydrodynamic diameter does not represent the real size of the particles, but the particle in solution (i.e., including its solvation shell).

Table 1 presents pH measurements of SiO

2 colloids over an 8-day period. A noticeable increase in pH (from 6.18 to 7.10 and 7.54) is observed during the initial days for both samples. The release of electrons (

e-) into the medium is the consequence of the oxidation of Si particles, which ultimately leads to an increase in pH. Once the oxidation of silicon is complete, the pH stabilizes and remains relatively constant for both samples. Minor fluctuations observed in the later stages are attributed to the exposure of atmospheric CO

2.

The results indicate that the irradiation process does not exert a significant effect on the pH of the SiO2 colloid, suggesting that irradiation does not substantially alter the chemical dynamics of the system under the experimental conditions employed. It is also worth noting that the neutral pH of the colloidal solution and the electron liberation to the medium, makes it ideal for metal reduction synthesis.

3.4. Optical Properties of Ag@SiO2 Nanoparticles

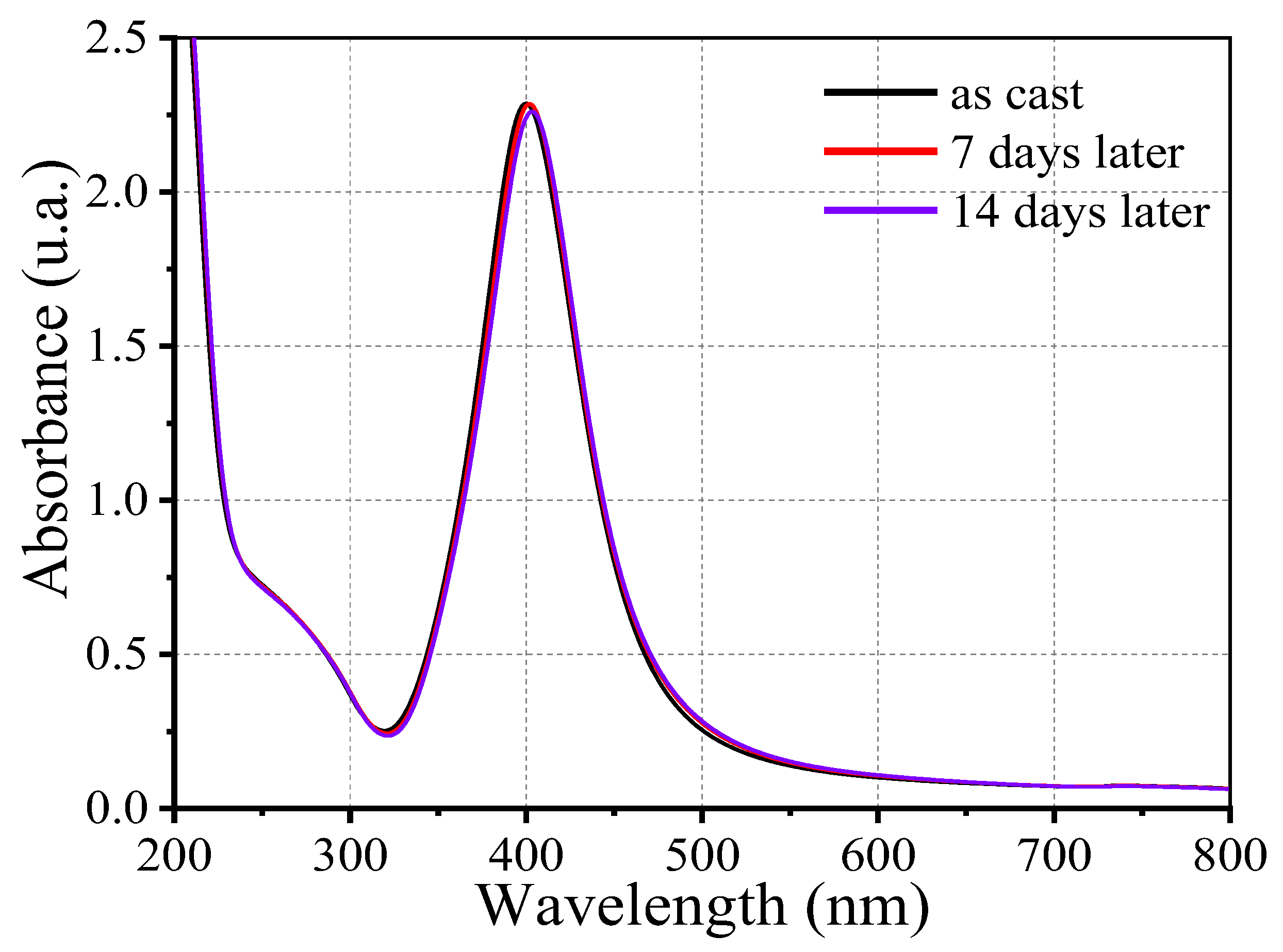

In

Figure 5, the absorption spectra of the synthesized Ag@SiO

2 nanoparticles are presented. The sample was characterized at three distinct time points: immediately following synthesis, seven days later, and fourteen days later. The absorption band observed at approximately 400 nm is indicative of silver nanoparticles and is caused by an optical phenomenon known as Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) (nanoparticle concentration 12.7 nM) [

43]. Moreover, a secondary absorption feature at approximately 272 nm is observed, with lower intensity. This feature can be attributed to electronic transitions to higher energy levels within the potential box. The nanoparticle’s strong structural and optical stability under the experimental conditions is implied by the fact that the absorption band remains stable over time. This stability is attributed to the SiO

2 shell that envelopes the nanoparticles, which provide colloidal stability.

AgNPs that have been coated with a silica shell demonstrate improved chemical and physical stability in comparison to uncoated relatives. The silica shell serves a formidable protective barrier that impedes oxidation, dissolution, and aggregation, thereby substantially reducing Ostwald ripening and maintaining the integrity of the nanoparticles over time. In addition, this core-shell architecture enables the functionalization of targeted applications and enhances dispersion stability in media. In our analysis, a slight redshift in the LSPR peak observed in UV-Vis spectra from 400 nm to 404 nm, represents a minor increase in effective particle size or subtle particle interactions, which are typical signatures of early -stage Ostwald ripening or mild aggregation. The effectiveness of the silica shell in maintaining colloidal stability is demonstrated by the fact that overall concentration of silver nanoparticle remains essentially constant, despite this redshift. It is necessary to tune the SiO2 -coated silver nanoparticles colloidal systems by modifying the ionic environment and surface chemistry of the silica shell.

3.5. Electrophoretic Properties and pH Measurements of Ag@SiO2 NPs

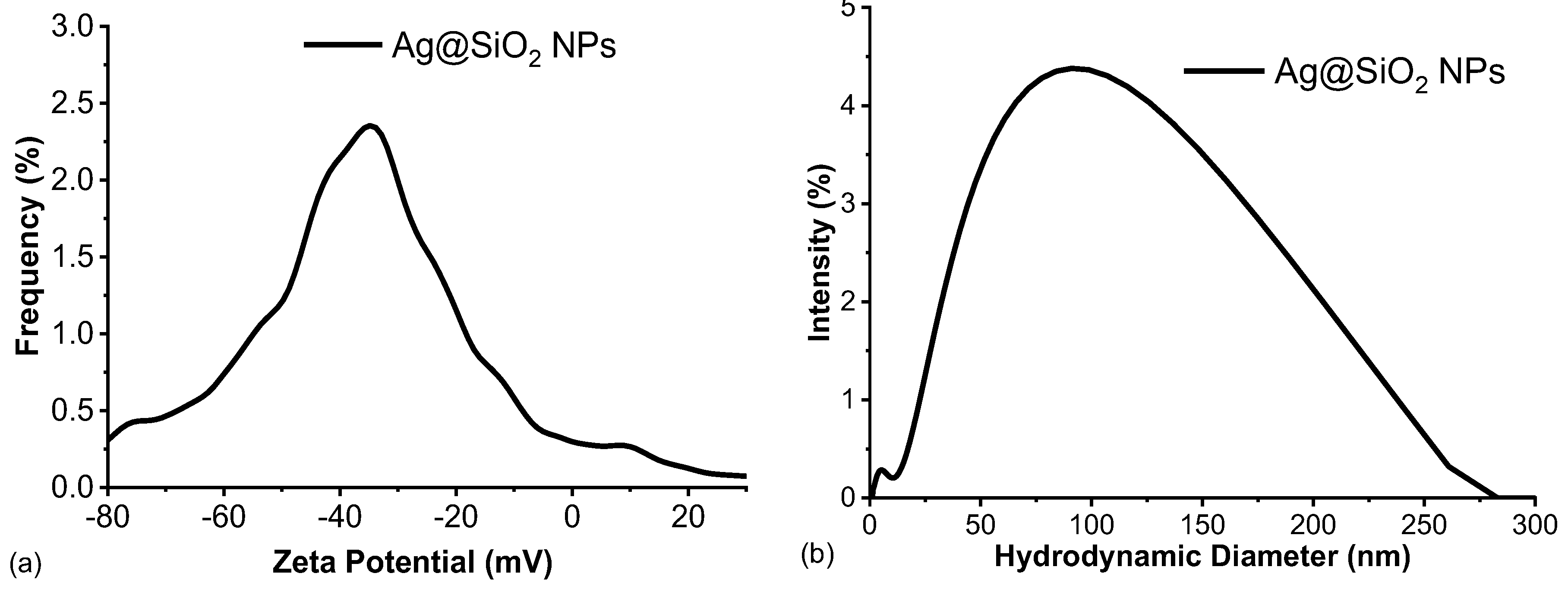

Figure 6 depicts the hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential of the synthesized Ag@SiO

2 NPs. The synthesized Ag@SiO

2 nanoparticles have a zeta potential value of -35.16 mV. As previously mentioned, this value is within the characteristic range of stable colloidal dispersions. Compared to SiO

2 extracted during the initial stage of the synthesis process (z~ -43 mV), the synthesized nanoparticles exhibit a slightly lower zeta potential modular value. This observation would suggest that the SiO

2 employed to reduce the metal salt is the primary factor controlling the high surface charge of the Ag@SiO

2 NPs. In accordance with the findings of the high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) studies [

12], the PLD method has been successfully implemented to produce Ag NPs with a stoichiometric SiO

2 shell on their surface, which has a thickness of approximately 2-3 nm. The zeta potential measurements, which suggest that the SiO

2 shell assembles around the NPs, supports the hypothesis that the core of the nanoparticles is coated with SiO

2 (Ag@SiO

2 NPs) due to the irradiation.

Moreover, the near-neutral pH value of 7.6 is a critical parameter contributing to the colloidal stability of the Ag@SiO

2 nanoparticles. Deviations from this pH, as well as changes in the ionic strength or composition of the medium, can have a substantial influence on the zeta potential resulting in the destabilization of the colloidal system. The mean values of pH, zeta potential, and hydrodynamic diameter obtained for the Ag@SiO

2 nanoparticles under the experimental conditions are summarized in

Table 2, which emphasizes the correlation between these parameters and the stability of the system.

The relatively large hydrodynamic diameter observed (~ 91 nm,

Table 2) can be attributed to the solvation layer surrounding the negative charged Ag@SiO

2 nanoparticles. This layer, which is composed of the solvent molecules and ions that are tightly bound, extends beyond the nanoparticle core, thereby increasing the apparent particle size as demonstrated by dynamic light scattering. The hydrodynamic diameter and colloidal behavior of the system are significantly influenced by the formation of this electrical double layer, which is influenced by electrostatic interactions with ions in the surrounding medium. The colloidal stability of the system is strongly supported by the measurements of both the zeta potential and hydrodynamic diameter. As evidenced by the high absolute of the negative zeta potential, the Ag@SiO

2 nanoparticles are prevented from aggregation due to the electrostatic repulsion among them. Moreover, the hydrodynamic diameter, which remains constant over time, indicates that nanoparticles are not agglomerating. The UV-Vis spectroscopy analysis further supports these findings, as demonstrate that nanoparticles typical absorption band persist throughout the study.

3.6. Structure and Size of Ag@SiO2 NPs by XRD.

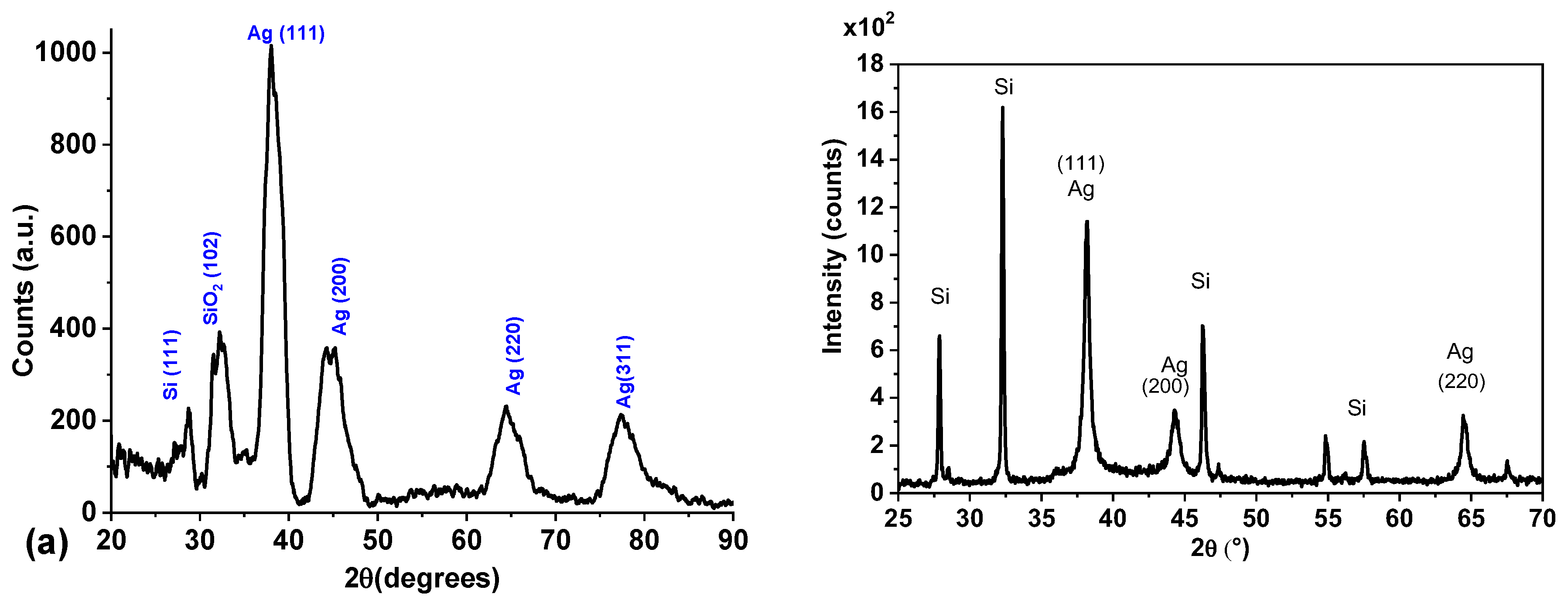

Figure 7a depicts the results for X-ray diffraction (XRD) of the Ag@SiO

2 NPs synthesized using the SiO

2 irradiated colloid. Diffractograms were obtained using the grazing incidence technique within the range 20°≤2θ ≤100°.

Diffractogram exhibits signals around 38°, 45°, 65°, and 77° corresponding to the (1 1 1), (2 0 0), (2 2 0), and (311) diffraction planes of the Ag FCC crystalline structure (PDF 04-0783). Both FWHM and intensity of signals are consistent with nanoscale material. The signal around 32° is attributed to the SiO

2 (PDF 893434) shell that coats the nanoparticles [

44].

The low-intensity signal observed at 28° corresponds to the (111) reflection of crystalline silicon (hexagonal structure). This suggests that a few crystalline silicon remains within the colloid after the irradiation process. It is worth mentioning that the signal intensity is very low compared to previously developed and reported processes where irradiation for fragmentation was not included in the synthesis process, and multiple high-intensity signals for crystalline silicon were observed (

Figure 7b).

The crystallite size of Ag was calculated using the Scherrer’s equation, and the signal at 38° corresponding to the (111) diffraction plane of silver.

Considering that silver nanoparticles are crystalline, we can affirm that the calculated value for the crystallite (9 nm) is a good measure for the nanoparticle’s diameter.

3.7. TEM and HRTEM of Ag@SiO2 NPs

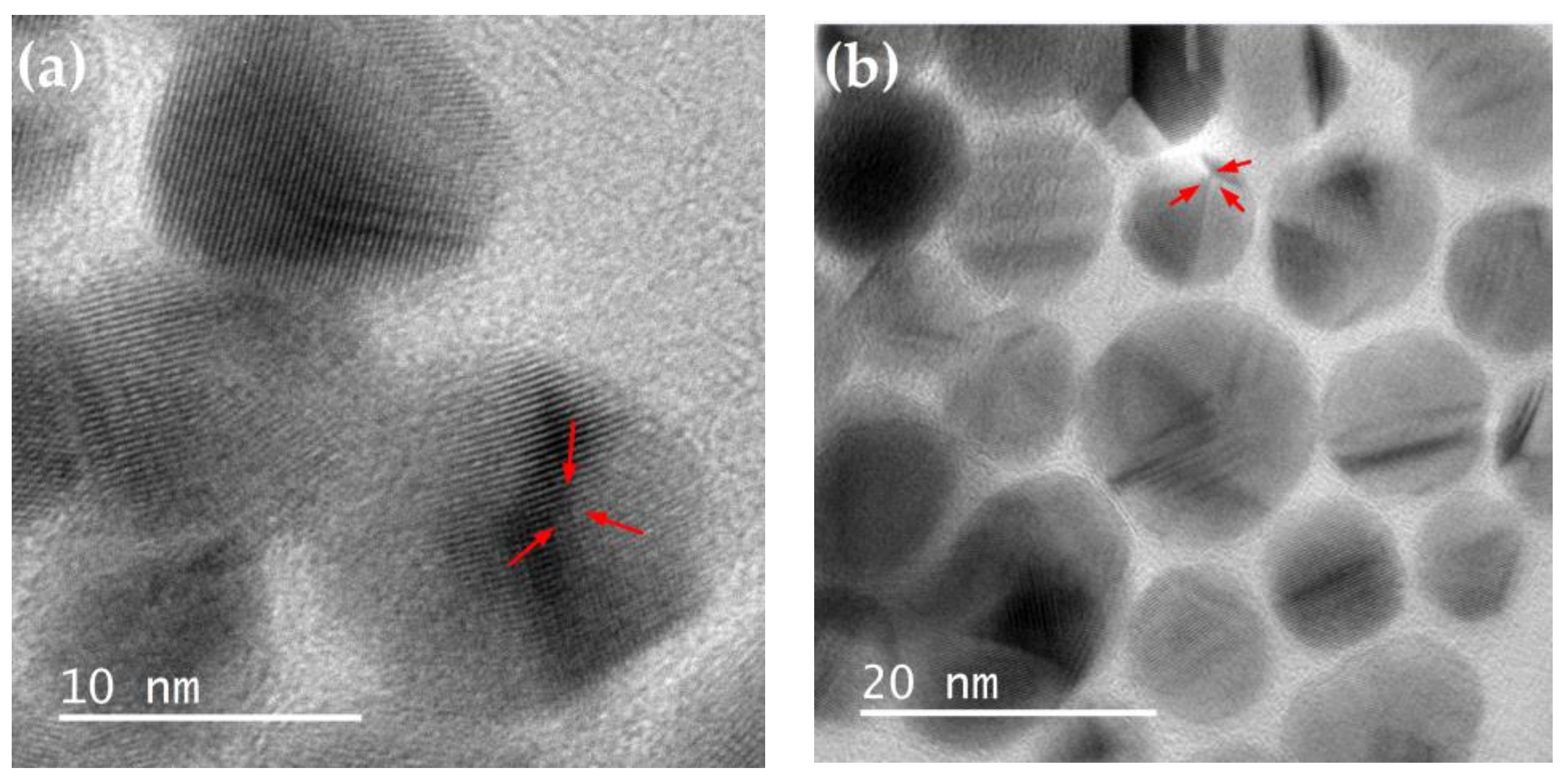

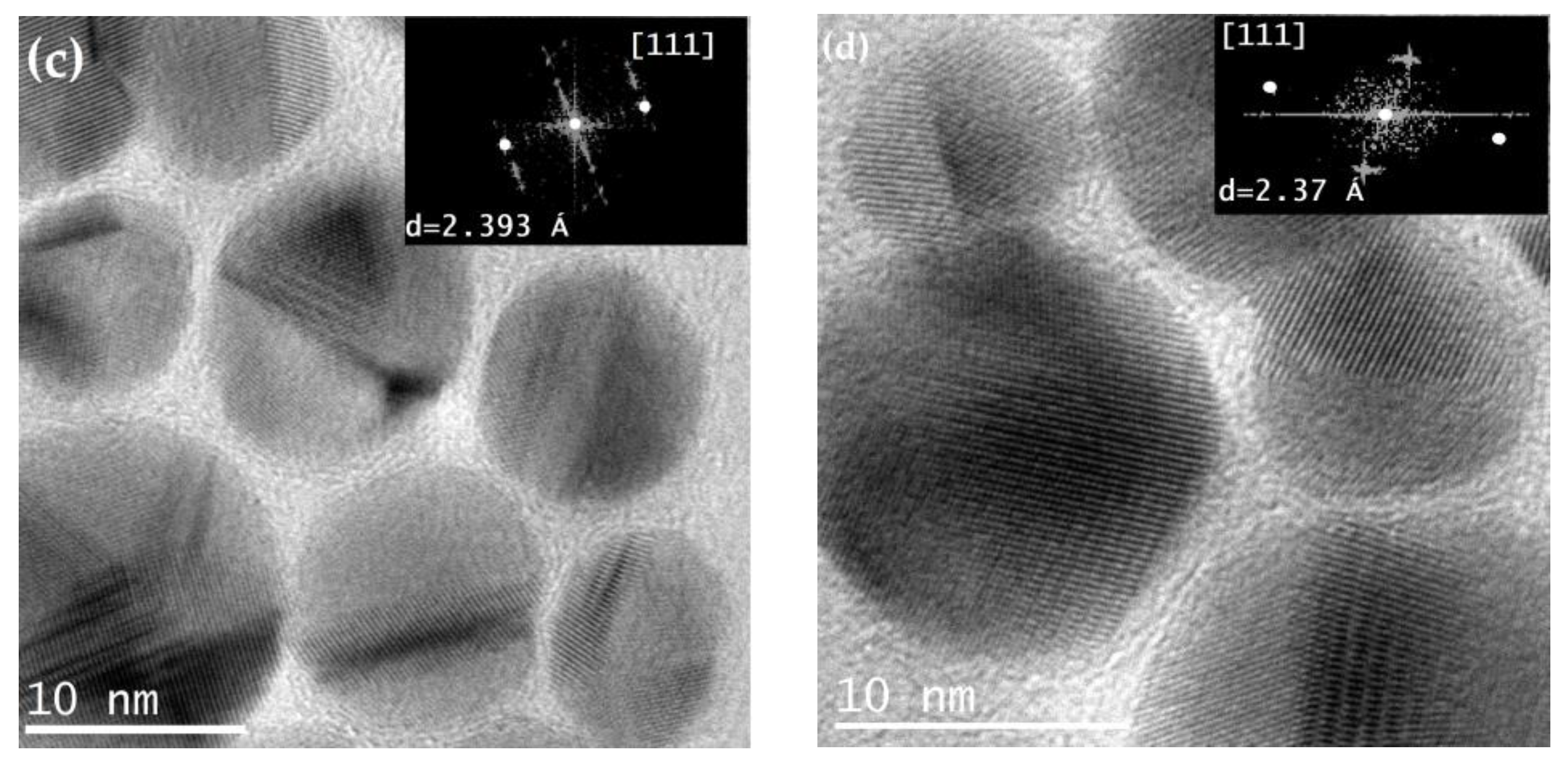

The morphological and structural properties of the synthesized Ag@SiO2 NPs were evaluated using Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) and the micrographs were processed with Digital Micrograph software.

The images obtained using high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) allow for the observation of homogeneously spherical silver nanoparticles with a crystalline nature, surrounded by an amorphous shell (SiO

2) that prevents them from agglomerating. A characteristic of AgNPs is the appearance of twin planes (yellow arrows in

Figure 8), which occur when there are two or more families of symmetrical crystal planes.

Insets in

Figure 8 (c) and (d) correspond to the analysis by Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) of the HRTEM images of Ag@SiO

2 NPs. Through this analysis, the interplanar distances were calculated (2.39 and 2.37 Å), which corresponds with the interplanar distance of the (111) plane (d=2.36 Å) according to the PDF card 04-0783 of silver FCC.

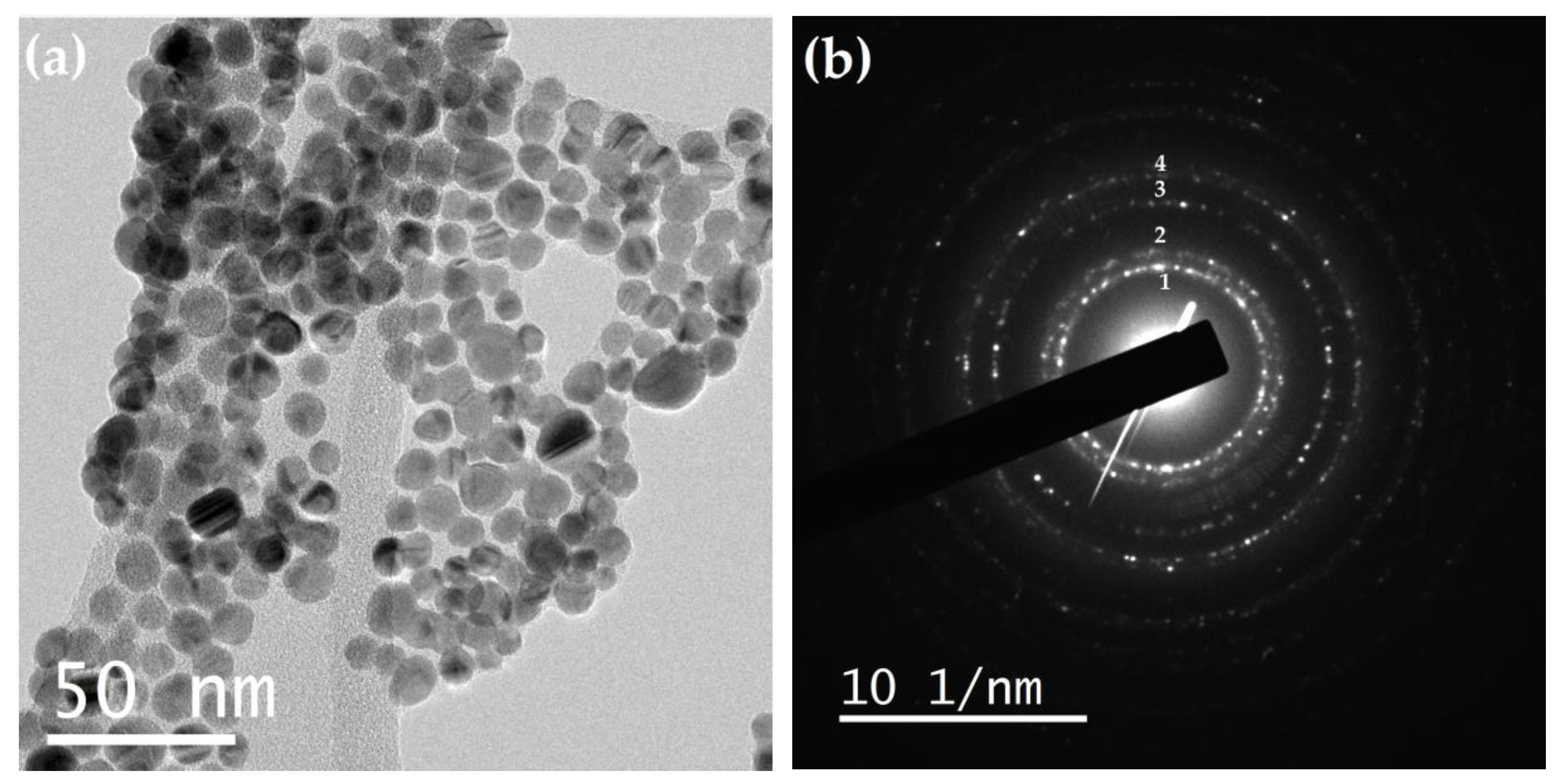

It is noteworthy that, despite the high density of nanoparticles, there is no coalescence between them (

Figure 9a), which is attributed to the SiO

2 coating. The ring diffraction pattern obtained from this image is shown in

Figure 9b, and the calculated interplanar distances were compared with the Ag PDF (

Table 3).

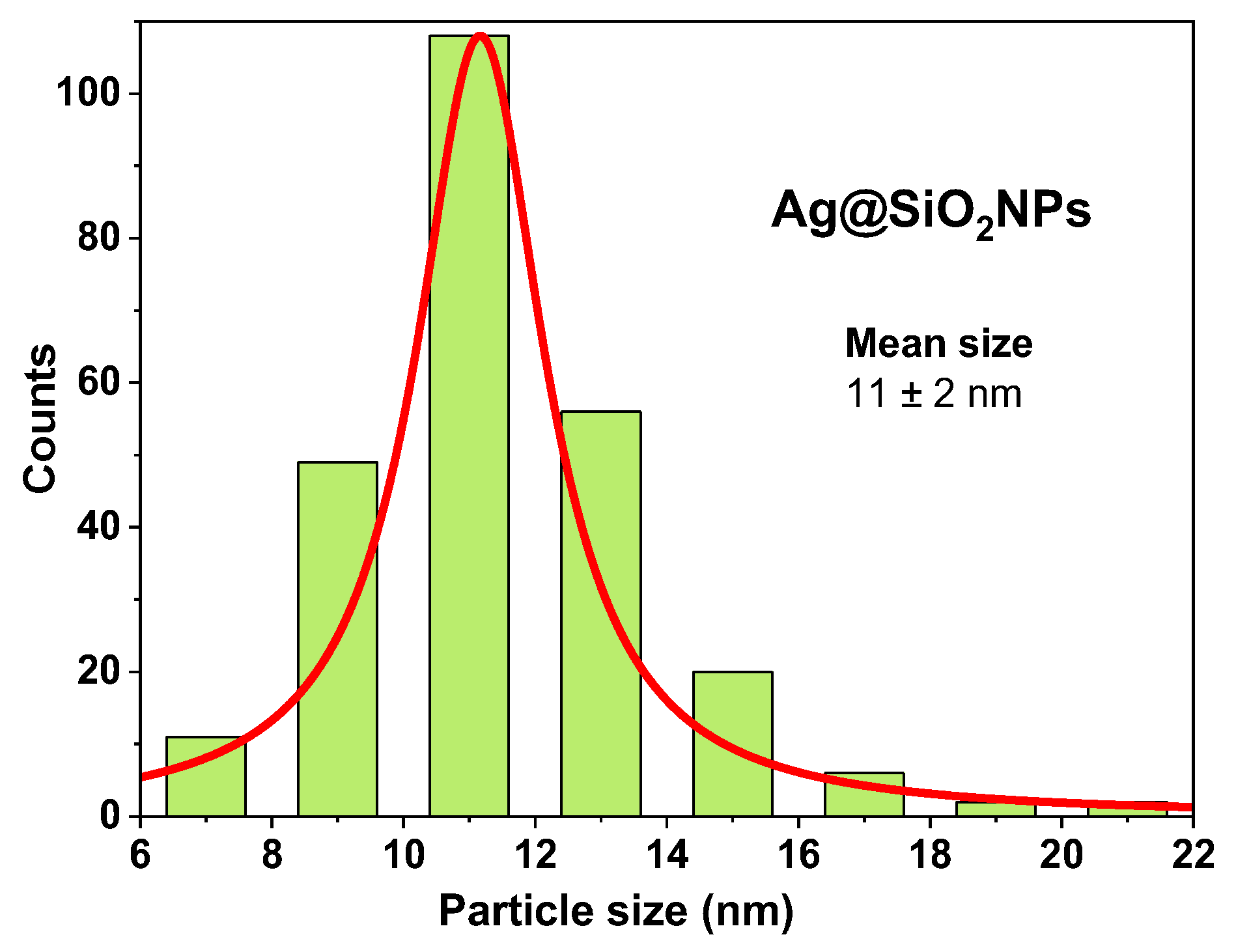

Ag@SiO

2 NPs histogram (

Figure 10) obtained from the TEM images, reveal a narrow size distribution (from 6 to 22nm) with a mean size of 11±2nm, which coincides with XRD results (reported above), and other values reported in the literature for Ag@SiO

2 NPs synthesized by this method [

27,

36].

3.8. Study of Ag@SiO2 NPs with AlCl3

In order to enhance the microbicidal applications of Ag@SiO

2 nanoparticles and modulate the surface charge, aluminum chloride (AlCl

3) was added to the colloidal suspension at varying concentrations. The Al

3+ ions introduced by AlCl

3 act as multivalent cations that effectively screen and neutralize the negatively charged Si-OH groups on the nanoparticle surface. The electrostatic repulsion between nanoparticles is reduced by this neutralization, which compresses the electrical double layer surrounding each nanoparticle, this destabilizes the colloidal system and promotes agglomeration [

45]. Furthermore, Al

3+ ions can function as bridging agents, allowing for the formation of ionic cross-links between nanoparticle surface thereby enhancing agglomeration. The balance between repulsive electrostatic forces and attractive van der Waals and ion-bridging interactions governs the extent and kinetic of agglomeration. Over a five-day period, the optical and electrophoretic properties of the suspensions were monitored to assess the influence of AlCl

3 concentration on the aggregation behavior and stability of the nanoparticles. Details of the sample preparation and experimental conditions are summarized in

Table 4.

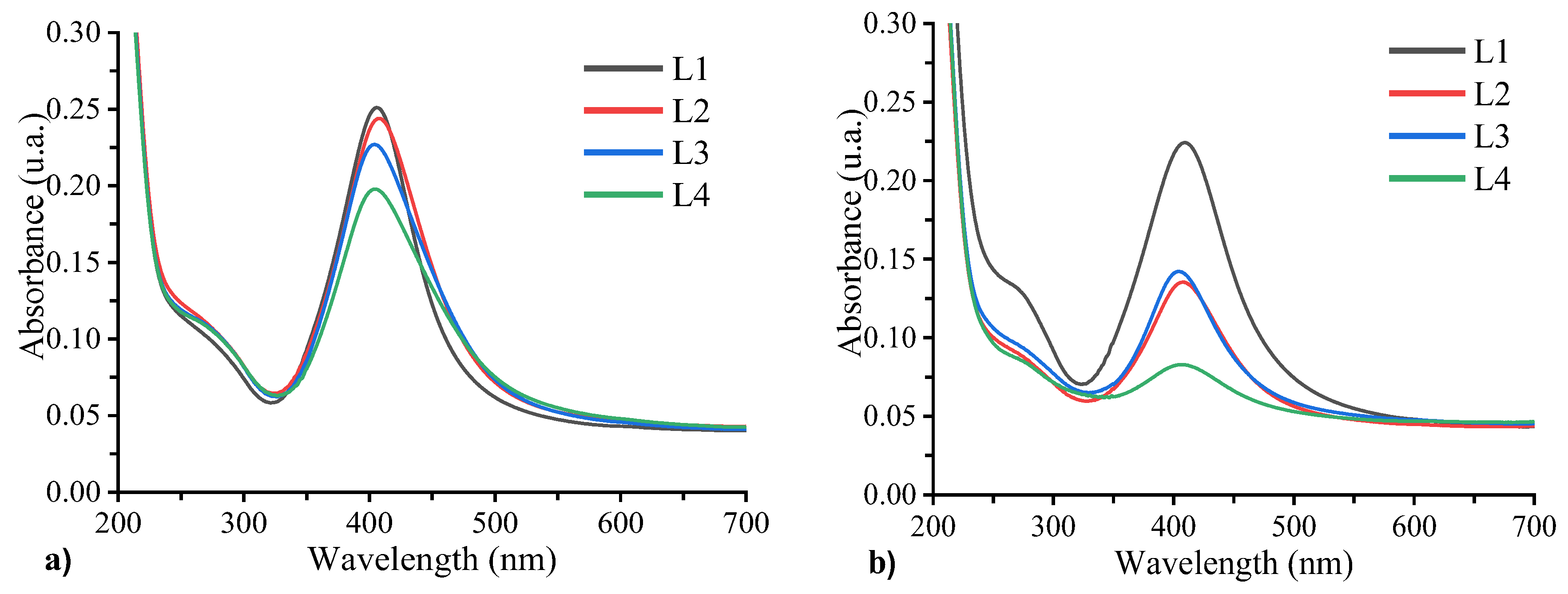

3.9. Optical Properties (UV-VIS Spectroscopy)

Figure 11 depicts the absorption spectra of samples L1, L2, L3, and L4, as they were recorded on the first and fifth days following their preparation. On the initial day, the surface plasmon resonance band is observed to be near 400 nm. Results reveal that by increasing the Al concentration, the plasmon intensity decreases and the FWHM increases. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in sample L4, which contains the highest Al concentration. The primary cause of this behavior is the role of the Al

3+ ions in mediating nanoparticle aggregation. Aluminum ions, which are trivalent cations with a high charge density, effectively screen and neutralize the negative surface charge provided by the silanol groups on the SiO

2 shell of the nanoparticles. Al

3+ ions promote aggregation and facilitates closer nanoparticles approach by compressing the electrical double layer and reducing electrostatic repulsion. Furthermore, Al

3+ ions can function as bridging species, stablishing ionic cross-links between neighboring nanoparticles and stabilizing larger aggregates that absorb light at longer wavelengths as can be seen in the absorption spectra. Simultaneously, the decrease in absorption intensity is indicative of a reduction in the population of small, dispersed nanoparticles, which typically absorb near 400 nm because of the agglomeration into larger clusters, which influences optical properties. The significant decrease in intensity observed in sample L4 when contrasted with L2 and L3 is the result of its elevated AlCl

3 concentration (2x10

-3 M)The absence of a second absorption band at longer wavelengths likely indicates that the concentration of aggregated nanoparticles remaining dispersed is below the UV-Vis detection threshold, consistent with the relatively low initial nanoparticle concentration of 10%.

After 5 days of sample preparation (

Figure 8b), the absorption band intensity decreases, evidencing ongoing Al

3+ induced aggregation and sedimentation of nanoparticles This leads to precipitation and a consequent reduction in the concentrations of suspended nanoparticles, Conversely, sample L1, lacking AlCl

3 maintains stable absorption features with no significant spectral changes, confirming the stability of the unmodified nanoparticles.

3.10. Zeta Potential and Hydrodynamic Diameter

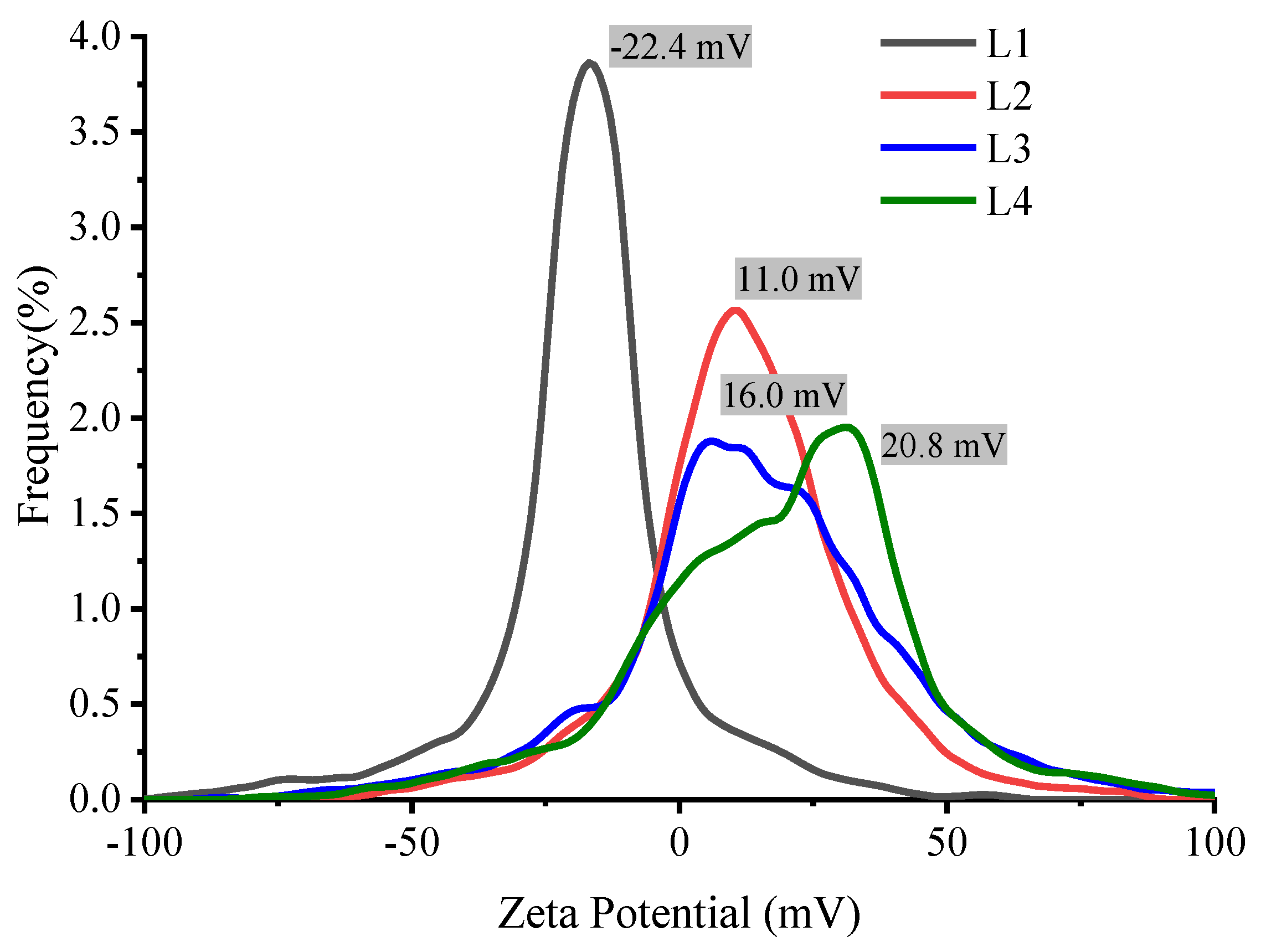

According to the theory of colloids, zeta potential is a function of the electrolyte concentration and the ion valence. This is reflected in the results shown in

Figure 12, where a decrease in the zeta potential is observed as a function of AlCl

3 concentration since Al

+3 ions counteract the negative charge of the SiO

2 shell. This reduces the colloidal repulsive potential, thereby facilitating the aggregation of Ag@SiO

2 NPs.

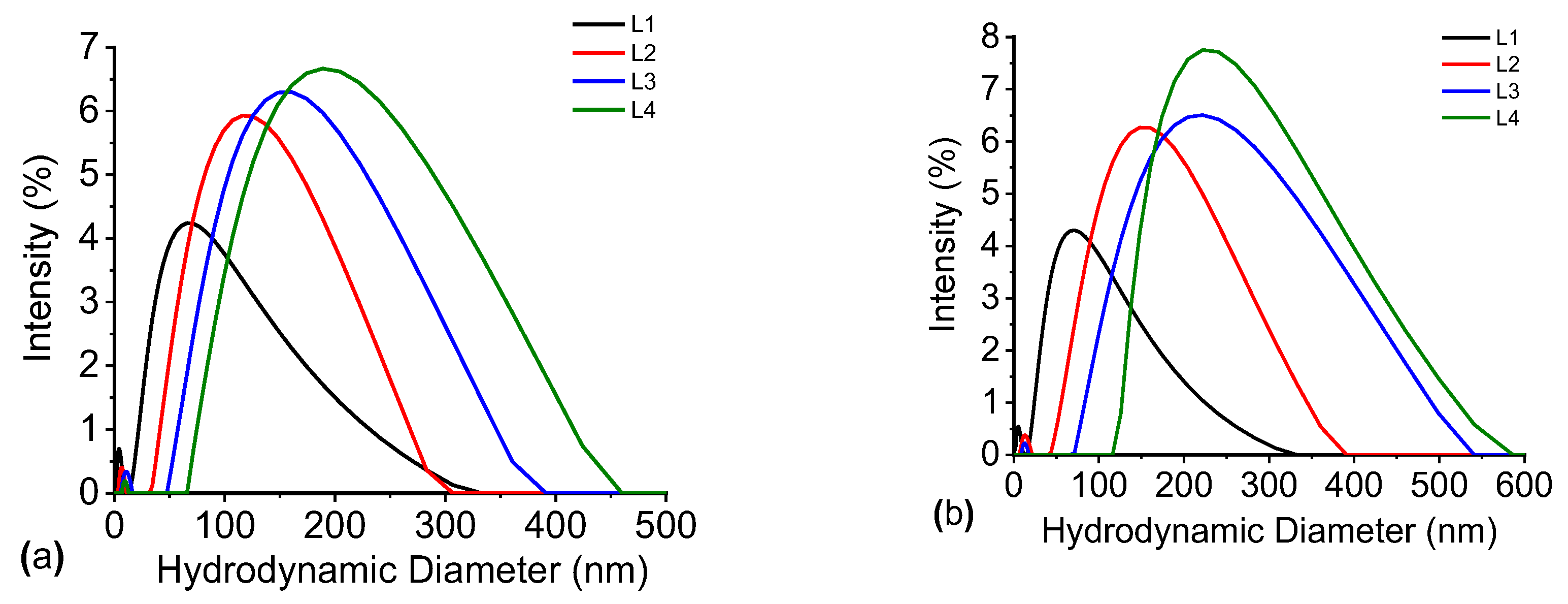

Figure 13 depicts the results of the hydrodynamic diameter evolution over time. These results of this study demonstrate a significant difference between the samples from the first day (

Figure 10a). A distinct increasing trend in the particle size is observed in all samples that contain AlCl

3, with the most pronounced change in the sample with the highest concentration (green line). The graphs in

Figure 10b also illustrate that the Ag@SiO

2 nanoparticles have the potential to form larger aggregates as time advances. Al

+3 ions are responsible for “screening” the negative charge of the silica solvation shell, which prevents that nanoparticles from aggregating and maintains them separated. Therefore, it can be concluded that a concentration of 2 x 10

-3 M of AlCl

3 is sufficient to cause the agglomeration and surface charge modification of nanoparticles.

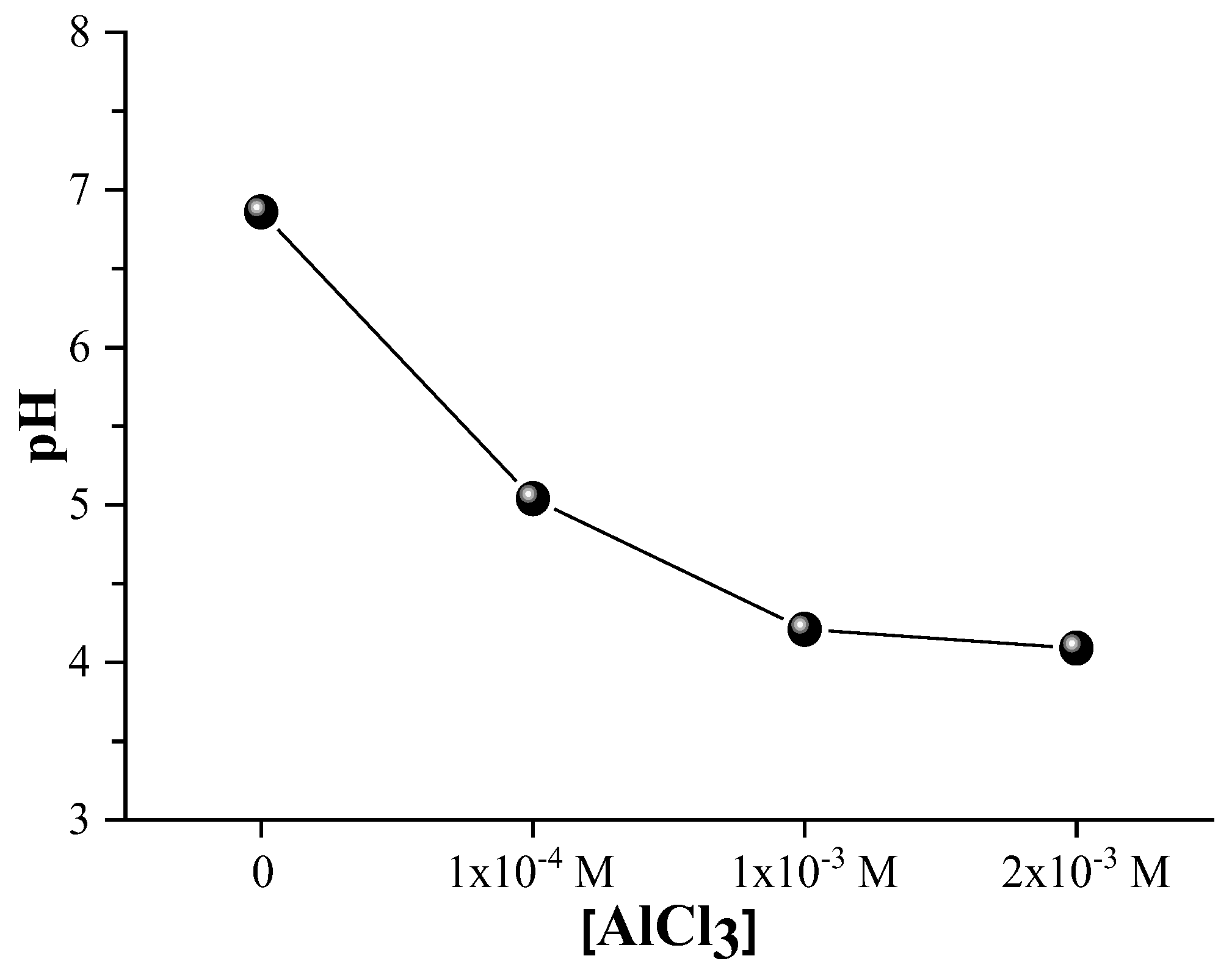

3.11. Isoelectric Point and pH Measurements

The colloidal stability of the Ag@SiO2 nanoparticles is substantiated by the fact that the sample maintains a neutral pH (approximately 7) as depicted in

Figure 14. The pH gradually decreases as the concentration of AlCl

3 increases, resulting in a more acidic environment. This acidification results from the hydrolysis of dissolved AlCl

3 which releases Al

+3 ions. Water and hydroxide ions react with these ions to form Al (OH)

3, which release protons (H

+) and increases the hydrogen ion concentration ([H

+]), thereby lowering the pH of the solution, according to:

Al3+ + 3H2O → Al (OH)3 + 3H+

Nanoparticles microbicidal activity is significantly influenced by the acidic medium generated by AlCl3. The release of silver ions from the silver core is primarily responsible for antimicrobial properties, which is enhanced by a lower pH. The bactericidal mechanisms of silver ions are multifaceted: they disrupt the integrity of cell membranes, generate reactive oxygen species that provokes oxidative damage, bind to thiol groups in proteins and DNA, thereby inhibiting vital functions, and interfere with replication processes, resulting in an eventual cell death. The controlled release of silver ions may be facilitated by a partial dissolution or restructuring of the silica shell, which is also promoted by Al+3 ions. Meanwhile, Al+3 ions. Also facilitate nanoparticles aggregation by neutralizing surface charges, which can elevate localized silver ion concentrations and improve microbicidal effect. Thus, the nanoparticles microbicidal efficacy is synergistically enhanced by the combined effects of AlCl3 -induced acidification and surface charge modification. To optimize antimicrobial performance and maintain colloidal stability, it is essential to achieve an optimal balance of pH and nanoparticle aggregation.

Since the hydrogen ion concentration affects the solvation layer surrounding the nanoparticles, the pH is directly related to zeta potential and plays a crucial role in colloidal stability.

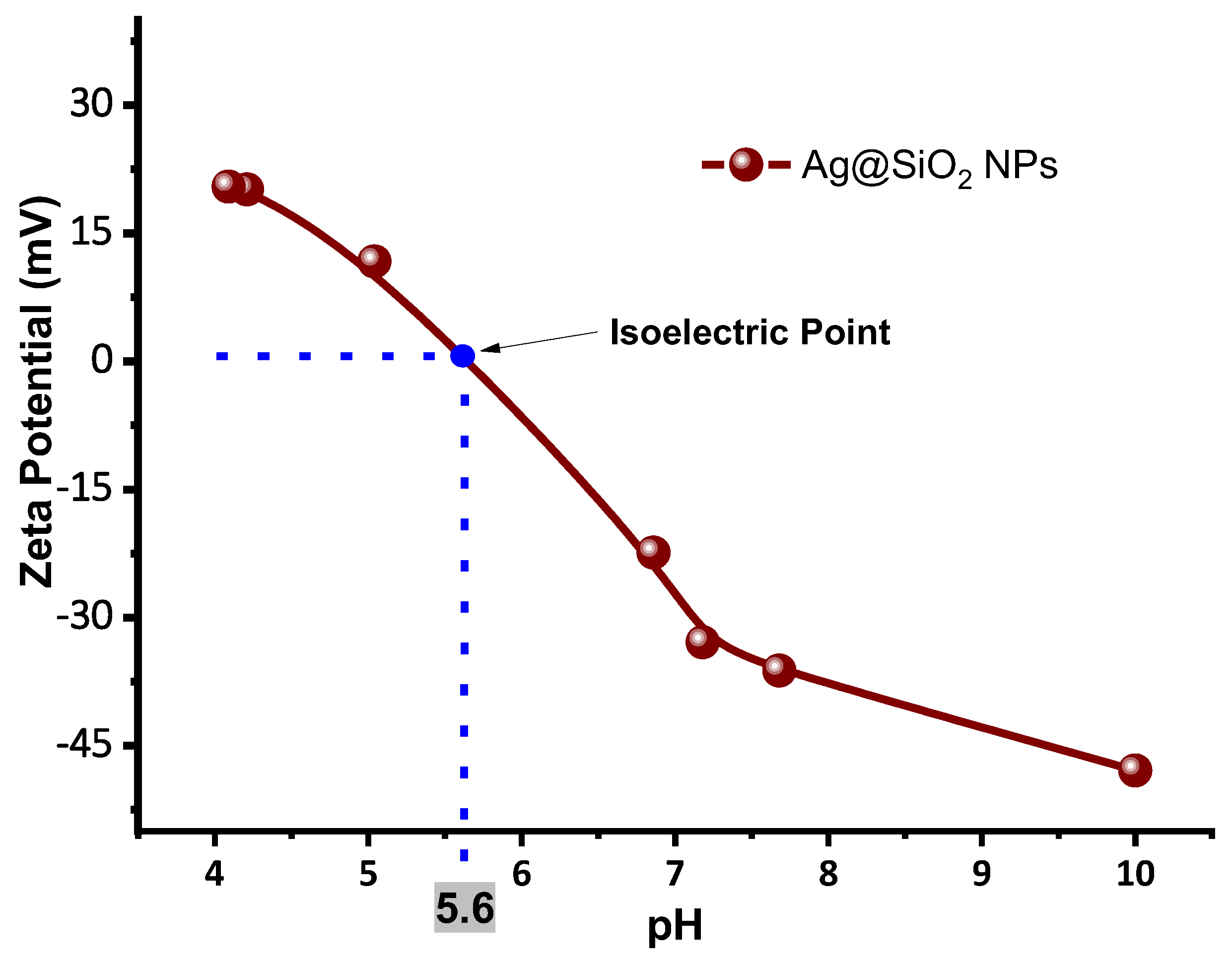

Figure 15 shows a graph of the zeta potential as a function of the pH at which the Ag@SiO

2 nanoparticles are presented, highlighting the isoelectric point (IEP), which is the pH at which a particle has a net charge of zero, and electrostatic repulsion is minimal. In this system, the IEP is approximately 5.6, which indicates the threshold at which aggregation initiates as a result of the loss of surface charge stabilization. This behavior is significantly influenced by the concentration of trivalent aluminum ions, which compress the electrical double layer and screen the negative charges on the silica surface, thereby reducing the magnitude of the zeta potential. The efficacy of this charge neutralization is significantly influenced by the concentration of the ions in relation to the Debye length, which is the characteristic distance by which the electrostatic interactions are screened in the medium [

46].

The Debye lengths for AlCl3 concentrations (1×10−4 M, 1×10−3 M, and 2×10−3 M) that were examined are approximately 12.4 nm, 3.9 nm, and 2.8 nm, respectively. The most optimal condition is achieved by the concentration of 1×10−3 M as the hydrodynamic diameters of Ag@SiO2 nanoparticles is on the order of 10-20 nm from UV-Vis analysis. Achieving optimal particle aggregation without rapid precipitation is facilitated by this concentration, which induces effective but controlled double-layer compression, since the particle size is comparable to the Debye length.

A larger Debye length is the result of a lower concentration (1×10−4 M) which is sufficient for strong charge screening and particle interaction. This lower concentration maintains high colloidal stability but potentially could limit microbicidal efficacy due to reduced silver ions release. On the other hand, the double layer undergoes excessive compression at the highest concentration (2×10−3 M), resulting in rapid and widespread aggregation that may result in sedimentation and the loss of nanoparticle functionality.

Thus, it is imperative to achieve a balance between effective aggregation and colloidal stability by optimizing the modulation of surface charge and zeta potential with Al+3 ions that are located near the Debye length that corresponds to nanoparticle size. This balance enhances microbicidal performance by fostering increased silver ions release and facilitating nanoparticle-microbe interactions while preventing premature nanoparticle loss.

Thus, we can conclude that a colloid of Ag@SiO2 NPs with a pH ≈ 5.6 will have zero charge, marking the point at which aggregation begins.

4. Discussion

The results obtained by X-Ray Diffraction, dynamic and electrophoretic scattering, and UV-VIS spectroscopy of SiO2 colloid give physical and chemical evidence that the irradiation process of the solution with a wavelength of 532 nm and an energy density of 200 mJ/cm2 for silicon fragmentation is efficient, and the amount of unreacted silicon remaining after SiO2 formation is relatively low. Furthermore, the high z potential value(-42 mV) of the SiO2 colloid give electrophoretic evidence that the Ag NPs are coated with a silica shell thus forming Ag@SiO2 NPs. The properties of the SiO2 colloid synthesized by laser ablation make it a suitable option for coating metal nanoparticles, as they provide stability, electric charge, and it ensure that the core remains isolated, thus reducing its reactivity. Zeta potential results demonstrated that the addition of AlCl3 at low concentrations promotes the aggregation of Ag@SiO2 NPs (both immediately and over the following 5 days) by altering the pH and their electric charge, reaching a value of +20.8 mV at a concentration of 2x10−3 M. This potentially could favor the microbicidal application, as larger positively charged aggregates can more easily adhere to microorganisms that have a negatively charged membrane. Varying AlCl3 concentrations, indicates that the Debye length decreases as the ionic strength increases, resulting in a thinner electrical double layer surrounding the nanoparticles. This reduction results in a larger hydrodynamic diameter as a result of aggregation, which in turn enhances particle-particle interactions. It is important to note that higher zeta potential is associated with enhanced colloidal stability, which is essential for the proper dispersion of nanoparticles and the optimization of their microbicidal efficacy. In the design and application of AgNPs as effective antimicrobial agents, the significance of controlling ionic strength and surface charge is emphasized by these findings. The isoelectric point (the pH value at which particles have a net charge of zero) for the Ag@SiO2 NPs is observed at a pH of 5.6 value at which the aggregation process may begin to occur.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, E.R.G. and V.E, G-A.; methodology, V.E, G-A., E. R-B.; software, V.E, G-A., E. R.G., A. B. L-O; validation, V.E, G-A., E. R.G., A. B. L-O., and D. D.A-L.; formal analysis, V. E., G-A.; investigation, V.E, G-A., E. R.G., A. B. L-O., D. J-O.; resources, E. R. G., E. R-B.; data curation, D. j-O, D. D.A-L, J. R. G-C; writing—original draft preparation, V.E. G-A.; writing—review and editing, E. R.G., A. B. L-O.; visualization, J. R. G-C.; supervision, E. R.G. D. J-O, E. R-B; project administration, E. R.G.; funding acquisition, E. R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research was funded by IPN SIP projects [grant number 2024-2786, 2024-0595, 2025-0189] and the APC was funded by Instituto Politécnico Nacional.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to SECIHTI and IPN for the financial support received through projects CB 183728, SNII, and postgraduate fellowship.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Ag@SiO2 NPs |

Coated-silver nanoparticles |

References

- A. F. Burlec et al., “Current Overview of Metal Nanoparticles’ Synthesis, Characterization, and Biomedical Applications, with a Focus on Silver and Gold Nanoparticles,” Pharmaceuticals, vol. 16, no. 10, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Shahalaei et al., “A review of metallic nanoparticles: present issues and prospects focused on the preparation methods, characterization techniques, and their theranostic applications,” Front. Chem., vol. 12, no. August, pp. 1–20, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Ammar and F. Fiévet, “Polyol synthesis: A versatile wet-chemistry route for the design and production of functional inorganic nanoparticles,” Nanomaterials, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 1–8, 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Fromme, S. Reichenberger, K. M. Tibbetts, and S. Barcikowski, “Laser synthesis of nanoparticles in organic solvents – products, reactions, and perspectives,” Beilstein J. Nanotechnol., vol. 15, pp. 638–663, 2024. [CrossRef]

- О. Kuntyi, L. Bazylyak, A. Kytsya, G. Zozulya, and M. Shepida, “Electrochemical Synthesis of Metal Nanoparticles: A Review,” Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem., vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 1–24, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Jiang, Y. Zeng, R. Guo, L. Lin, R. Luque, and K. Yan, “Recent advances on CO2-assisted synthesis of metal nanoparticles for the upgrading of biomass-derived compounds,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 203, no. March, p. 114756, 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Patelli, A. Migliori, V. Morandi, and L. Pasquini, “One-step synthesis of metal/oxide nanocomposites by gas phase condensation,” Nanomaterials, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 1–15, 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Sakono, K. Omori, K. Yamamoto, N. Ishikuro, and M. Sakono, “Vapor-phase synthesis of bimetallic plasmonic nanoparticles,” Anal. Sci., vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 61–65, 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Zhang and H. Wada, “Laser Ablation in Liquids for Nanomaterial Synthesis and Applications,” Handb. Laser Micro-and Nano-Engineering, vol. 3, pp. 1481–1516, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Nyabadza, M. Vazquez, and D. Brabazon, “A Review of Bimetallic and Monometallic Nanoparticle Synthesis via Laser Ablation in Liquid,” Crystals, vol. 13, no. 2, 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. G. Semaltianos and G. Karczewski, “Laser Synthesis of Magnetic Nanoparticles in Liquids and Application in the Fabrication of Polymer-Nanoparticle Composites,” ACS Appl. Nano Mater., vol. 4, no. 7, pp. 6407–6440, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. R. González-Castillo, Eugenio Rodríguez-González, Ernesto Jiménez-Villar, Carlos Lenz Cesar, Jacob Antonio Andrade-Arvizu. Assisted laser ablation: Silver/gold nanostructures coated with silica, Applied Nanoscience Vol. 7 (8) 597-605, (2017), ISSN: 2190-5509. [CrossRef]

- E. Rodriguez, E. Jimenez, A. A. R. Neves, G. J. Jacob, C. L. Cesar and L. C. Barbosa, “SiO2/PbTe Quantum Dots Multilayer Production and Characterization”, Appl. Phys. Lett., 86 (2005) 113117-113120. ISSN 0003-6951 eISSN 1077-3118. [CrossRef]

- E. Rodriguez, E. Jimenez, L. Moya, C. L. Cesar, L.P. Cardoso and L. C. Barbosa, “Plasma Dynamics Studies During the Preparation of PbTe Thin Film on Glass Substrate”, Vacuum 80, (2006) 841-849. ISSN: 1879-2715 eISSN: 0042-207X. [CrossRef]

- T. Donnelly, G. O’connell, and J. G. Lunney, “Metal nanoparticle film deposition by femtosecond laser ablation at atmospheric pressure,” Nanomaterials, vol. 10, no. 11, pp. 1–13, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sahar M.Ouda, “Antifungal activity of silver and copper nanoparticles on two plant pathogens, Alternaria alternata and Botrytis cinerea,” Res. J. Microbiol., vol. 9, pp. 34–42, 2014.

- S. W. Kim, J. H. Jung, K. Lamsal, Y. S. Kim, J. S. Min, and Y. S. Lee, “Antifungal effects of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) against various plant pathogenic fungi,” Mycobiology, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 53–58, 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Rai, A. Yadav, and A. Gade, “Silver nanoparticles as a new generation of antimicrobials,” Biotechnol. Adv., vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 76–83, 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. Rajawat and M. S. Qureshi, “Comparative Study on Bactericidal Effect of Silver Nanoparticles, Synthesized Using Green Technology, in Combination with Antibiotics on Salmonella Typhi,” J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol., vol. 03, no. 04, pp. 480–485, 2012. [CrossRef]

- E. Hutter and J. H. Fendler, “Exploitation of localized surface plasmon resonance,” Adv. Mater., vol. 16, no. 19, pp. 1685–1706, 2004. [CrossRef]

- R. B. M. Schasfoort, Chapter 1. Introduction to Surface Plasmon Resonance, Handb. Surf. Plasmon Reson., pp. 1–26, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Tame, K. R. McEnery, Ş. K. Özdemir, J. Lee, S. A. Maier, and M. S. Kim, “Quantum plasmonics,” Nat. Phys., vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 329–340, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Rothe et al., Silver nanowires with optimized silica coating as versatile plasmonic resonators, Sci. Rep., vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–13, 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Jiménez, K. Abderrafi, J. Martínez-Pastor, R. Abargues, J. Luís Valdés, and R. Ibáñez, A novel method of nanocrystal fabrication based on laser ablation in liquid environment, Superlattices Microstruct., vol. 43, no. 5–6, pp. 487–493, 2008. [CrossRef]

- E. Jiménez, K. Abderrafi, R. Abargues, J. L. Valdés, and J. P. Martínez-Pastor, “Laser-ablation-induced synthesis of SiO2-capped noble metal nanoparticles in a single step,” Langmuir, vol. 26, no. 10, pp. 7458–7463, 2010. [CrossRef]

- V. A. Ermakov, E. Jimenez-Villar, J. M. Clemente da Silva Filho, E. Yassitepe, N.V. V. Mogili, F. Iikawa, G. Fernandes de Sá, C. L. Cesar, F. C. Marques. Size Control of Silver-Core/Silica-Shell Nanoparticles Fabricated by Laser-Ablation-Assisted Chemical Reduction, Langmuir 2017, 33, 9, 2257–2262. [CrossRef]

- G. Fuertes, O. L. Sánchez-Muñoz, E. Pedrueza, K. Abderrafi, J. Salgado, and E. Jiménez, “Switchable bactericidal effects from novel silica-coated silver nanoparticles mediated by light irradiation,” Langmuir, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 2826–2833, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Juana-Cristina Ibarra-Arán, Douglas Rodríguez-Martínez, Eugenio Rodríguez-González, Jesús-Roberto González-Castillo, In vitro evaluation of bactericidal effect of silver and gold-silver nanoparticles coated with silicon dioxide on Xanthomonas fragariae, MRS Advances Vol. 2, 49 (2017) 2683-2688, ISSN 2059-8521. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Leventis and S. Grinstein, “The distribution and function of phosphatidylserine in cellular membranes,” Annu. Rev. Biophys., vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 407–427, 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Prejanò, M. E. Alberto, N. Russo, M. Toscano, and T. Marino, “The effects of the metal ion substitution into the active site of metalloenzymes: A theoretical insight on some selected cases,” Catalysts, vol. 10, no. 9, pp. 1–28, 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. E. Saka and C. Güler, “The effects of electrolyte concentration, ion species and pH on the zeta potential and electrokinetic charge density of montmorillonite,” Clay Miner., vol. 41, no. 4, pp. 853–861, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, M. Tourbin, S. Lachaize, and P. Guiraud, “Silica nanoparticle separation from water by aggregation with AlCl 3,” Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 1853–1863, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, M. Tourbin, S. Lachaize, and P. Guiraud, “Silica nanoparticle separation from water by aggregation with AlCl 3,” Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 1853–1863, 2012. [CrossRef]

- C. Li and P. Somasundaran, “Reversal of bubble charge in multivalent inorganic salt solutions-Effect of aluminum,” J. Colloid Interface Sci., vol. 148, no. 2, pp. 587–591, 1992. [CrossRef]

- C. Lin, “Encyclopedia of Microfluidics and Nanofluidics,” Encycl. Microfluid. Nanofluidics, pp. 1–11, 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. R. González-Castillo et al., “Synthesis of Ag@Silica Nanoparticles by Assisted Laser Ablation,” Nanoscale Res. Lett., vol. 10, no. 1, 2015. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M. C.; Gauss, J. Exotic SiO2H2 Isomers: Theory and Experiment Working in Harmony. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7 (10), 1895–1900.

- R. Kitamura et al., “Optical constants of silica glass from extreme ultraviolet to far infrared at near room temperature,” Water Res., vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 1–8, 2007, [Online]. Available: http://library1.nida.ac.th/termpaper6/sd/2554/19755.pdf%0Ahttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2018.02.018%0Ahttps://www.n95decon.org/files/uvc-technical-report%0Ahttps://www.researchgate.net/publication/340133321%0Ahttps://telechargement-afnor.com/masques-barr.

- I. A. Rahman, P. Vejayakumaran, C. S. Sipaut, J. Ismail, and C. K. Chee, “Size-dependent physicochemical and optical properties of silica nanoparticles,” Mater. Chem. Phys., vol. 114, no. 1, pp. 328–332, 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Green et al., “Doped, conductive SiO2 nanoparticles for large microwave absorption,” Light Sci. Appl., vol. 7, no. 1, 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. O. Shaparenko, M. G. Demidova, L. A. Erlygina, and A. I. Bulavchenko, “Charged colloidal SiO2 dispersions in water and chloroform: Synthesis, properties and perspectives in dyes adsorption,” Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp., vol. 669, no. February, p. 131505, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Malvern Instruments, “User manual Zetasizer nano,” p. 250, 2013.

- N. D. Thien et al., “Optical properties of SiO2 opal crystals decorated with silver nanoparticles,” Opt. Mater. X, vol. 24, no. September, p. 100362, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Alimunnisa, K. Ravichandran, and K. S. Meena, “Synthesis and characterization of Ag@SiO2 core-shell nanoparticles for antibacterial and environmental applications,” J. Mol. Liq., vol. 231, pp. 281–287, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Hsu and B. T. Liu, “Stability of colloidal dispersions: charge regulation/adsorption model,” Langmuir, vol. 15, no. 16, pp. 5219–5226, 1999. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud Khademi and Dominik P. J. Barz, Structure of the Electrical Double Layer Revisited: Electrode Capacitance in Aqueous Solutions, Langmuir 2020 36 (16), 4250-4260. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the laser system used for ablation (red) and irradiation (green).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the laser system used for ablation (red) and irradiation (green).

Figure 2.

Absorption spectra of the as-cast SiO2 colloid, irradiated for 5 minutes, and irradiated for 10 minutes. The absorption spectrum of HPLC water was also added for reference.

Figure 2.

Absorption spectra of the as-cast SiO2 colloid, irradiated for 5 minutes, and irradiated for 10 minutes. The absorption spectrum of HPLC water was also added for reference.

Figure 3.

Diffractograms pattern of colloidal SiO2- H2O obtained by laser ablation. (green line)- as cast, (blue line)- after irradiation.

Figure 3.

Diffractograms pattern of colloidal SiO2- H2O obtained by laser ablation. (green line)- as cast, (blue line)- after irradiation.

Figure 4.

(a) Zeta Potential (mV) and (b) Hydrodynamic diameter of SiO2 colloid as cast (black) and irradiated by 5 minutes (red).

Figure 4.

(a) Zeta Potential (mV) and (b) Hydrodynamic diameter of SiO2 colloid as cast (black) and irradiated by 5 minutes (red).

Figure 5.

Absorption spectra of Ag@SiO2 NPs as a function of time, evaluated through 15 days.

Figure 5.

Absorption spectra of Ag@SiO2 NPs as a function of time, evaluated through 15 days.

Figure 6.

a) Zeta Potential and b) Hydrodynamic Diameter graphs of Ag@SiO2 NPs.

Figure 6.

a) Zeta Potential and b) Hydrodynamic Diameter graphs of Ag@SiO2 NPs.

Figure 7.

Diffraction pattern of Ag@SiO

2 NPs. (a)-this work and (b)-previously reported [

28].

Figure 7.

Diffraction pattern of Ag@SiO

2 NPs. (a)-this work and (b)-previously reported [

28].

Figure 8.

High resolution images with a 10 y 20nm scale and diffractograms obtained by FFT, red arrows show some twin planes, characteristics of AgNPs.

Figure 8.

High resolution images with a 10 y 20nm scale and diffractograms obtained by FFT, red arrows show some twin planes, characteristics of AgNPs.

Figure 9.

(a) TEM image and (b) ring diffraction pattern of Ag@SiO2 NPs.

Figure 9.

(a) TEM image and (b) ring diffraction pattern of Ag@SiO2 NPs.

Figure 10.

Size distribution histogram and mean size of Ag@SiO2 NPs.

Figure 10.

Size distribution histogram and mean size of Ag@SiO2 NPs.

Figure 11.

Absorption spectra of L1, L2, L3, and L4 samples evaluated the 1st (a) and the 5th day (b).

Figure 11.

Absorption spectra of L1, L2, L3, and L4 samples evaluated the 1st (a) and the 5th day (b).

Figure 12.

Zeta Potential of Ag@SiO2 NPs with different concentrations of AlCl3.

Figure 12.

Zeta Potential of Ag@SiO2 NPs with different concentrations of AlCl3.

Figure 13.

Hydrodynamic Diameter of samples L1, L2, L3, and L4 evaluated (a)- the 1st day and (b)- the 5th day.

Figure 13.

Hydrodynamic Diameter of samples L1, L2, L3, and L4 evaluated (a)- the 1st day and (b)- the 5th day.

Figure 14.

pH measurements of Ag@SiO2 NPs with different concentrations of AlCl3.

Figure 14.

pH measurements of Ag@SiO2 NPs with different concentrations of AlCl3.

Figure 15.

Zeta Potential of Ag@SiO2 NPs as a function of pH, showing its Isoelectric Point.

Figure 15.

Zeta Potential of Ag@SiO2 NPs as a function of pH, showing its Isoelectric Point.

Table 1.

Values of pH measurements over time (days).

Table 1.

Values of pH measurements over time (days).

| Sample |

Day 1 |

Day 4 |

Day 5 |

Day 6 |

Day 7 |

Day 8 |

| as cast SiO2

|

6.18 |

7.54 |

7.12 |

7.00 |

6.82 |

6.80 |

SiO2-irradiated

(5 min) |

6.18 |

7.10 |

7.10 |

7.04 |

6.88 |

6.88 |

Table 2.

pH, Zeta Potential and Hydrodynamic Diameter mean values of Ag@SiO2.

Table 2.

pH, Zeta Potential and Hydrodynamic Diameter mean values of Ag@SiO2.

| pH |

Zeta potential

(mV) |

Mean hydrodynamic

diameter (nm) |

| 7.6 |

-35.16 |

91 |

Table 3.

Ring diffraction pattern analysis.

Table 3.

Ring diffraction pattern analysis.

| Number of ring |

Diffraction plane |

Calculated

distance [Å] |

PDF distance [Å] |

Error (%) |

| 1 |

1 1 1 |

2.40 |

2.36 |

4 |

| 2 |

2 0 0 |

2.08 |

2.04 |

4 |

| 3 |

2 2 0 |

1.50 |

1.45 |

5 |

| 4 |

3 1 1 |

1.24 |

1.23 |

1 |

Table 4.

Summary of the Ag@SiO2 NPs + AlCl3 samples evaluated.

Table 4.

Summary of the Ag@SiO2 NPs + AlCl3 samples evaluated.

| ID sample |

Sample content |

| L1 |

H2O HPLC +Ag@SiO2 NPs 10 % (20 mL) |

| L2 |

H2O HPLC +Ag@SiO2 NPs 10 % + 1 x 10-4 M AlCl3 (20 mL) |

| L3 |

H2O HPLC +Ag@SiO2 NPs 10 % + 1 x 10-3 M AlCl3 (20 mL) |

| L4 |

H2O HPLC +Ag@SiO2 NPs 10 % + 2 x 10-3 M AlCl3 (20 mL) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).