1. Introduction

The hydroxyl radical (•OH) is an exceptionally potent oxidizing agent found in various environments, including natural waters, the atmosphere, and interstellar space. As one of the most important reactive oxygen species (ROS), •OH plays a pivotal role in numerous chemical processes, particularly in environmental chemistry and biochemistry. In environmental applications, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) are widely employed in wastewater treatment to degrade pollutants effectively [

1,

2]. In the medical field, •OH radicals are utilized in innovative therapeutic approaches such as photodynamic therapy and chemodynamic therapy, which target cancer cells through oxidative damage within the tumor microenvironment [

3,

4]. Advancing methods for enhanced •OH radical generation is critical for expanding its potential applications in both environmental remediation and healthcare.

Photocatalytic materials absorb light with energy exceeding their band gap, generating excited electrons and holes. These charge carriers migrate to the surface of the material, where they act as reducing and oxidizing agents, facilitating redox reactions. For example, the reduction of oxygen or the oxidation of water results in the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide radicals and •OH. These ROS play a key role in degrading organic compounds. However, a significant portion of the excited electrons and holes recombine before contributing to the reaction, releasing energy as heat instead [

5,

6].

In addition to photocatalysis, sonocatalysis involves the activation of materials, known as sonocatalysts, by ultrasound waves in liquids through high-energy acoustic cavitation. The collapse of cavitation bubbles generates extreme heat and pressure, causing the pyrolytic cleavage of water molecules. This process thermally dissociates water into •OH and hydrogen atoms, often accompanied by sonoluminescence. The effectiveness of sonocatalysts arises from the inherent sonocatalytic activity of semiconductors [

6,

7]. In the medical field, sonocatalysts are pivotal in sonodynamic therapy, where ultrasound activates the sonocatalysts to produce ROS, selectively destroying tumor cells. Thus, sonocatalysts play a vital role in tackling environmental challenges and advancing medical therapies [

8,

9].

Sonocatalysts, primarily composed of metals or metal oxides, are widely utilized in environmental remediation and therapeutic applications to facilitate chemical reactions and degrade persistent contaminants. Among these materials, titanium dioxide (TiO₂) is one of the most extensively studied in sonocatalysis [

6,

7,

10,

11]. Recent research has aimed to enhance the efficiency of TiO₂-based sonocatalytic processes and expand their applications in both medical and environmental fields [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Incorporating TiO₂ nanoparticles (NPs) with noble metals, such as gold (Au), has been shown to improve their sonocatalytic performance [

19,

20,

21]. Noble metals not only extend the absorption spectrum through surface plasmon resonance but also serve as electron sinks, facilitating electron transfer and reducing electron-hole recombination.

Gold nanoclusters (Au NCs), tiny aggregates of Au atoms with diameters smaller than 2 nm, exhibit unique properties distinct from bulk gold and larger plasmonic Au NPs [

22,

23,

24]. These clusters display unique electronic states due to quantum-size effects. Structurally, Au NCs consist of a gold atom core surrounded by a protective layer of organic ligands. Their electronic structures, characterized by specific energy levels such as the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), vary with cluster size and significantly influence their physicochemical properties. As innovative nanomaterials, Au NCs hold great potential in catalysis and luminescence, primarily due to their size-dependent properties and exceptional stability [

25,

26,

27].

In our previous research, we explored the sonocatalytic potential of Au NCs [

28,

29]. Specifically, we synthesized Au

144 NCs /TiO₂ composites by integrating Au

144 NCs with TiO₂ NPs. The composites exhibited significantly enhanced sonocatalytic activity compared to TiO₂ alone under ultrasonication at 1 MHz [

30]. The sonocatalytic activation of the Au

144/TiO₂ composite is primarily driven by the generation of high-energy cavitation bubbles during ultrasonication. The characteristics of these cavitation bubbles, which are influenced by the power and frequency of ultrasonication, play a crucial role in determining the sonocatalytic performance of the composite. Despite the promising results, the current literature provides limited insight into how ultrasonication frequency and power affect the sonocatalytic efficiency of Au NCs/TiO₂-based catalysts. To address this gap, our ongoing research aims to optimize the sonocatalytic performance of Au

144/TiO₂ composites by systematically refining ultrasonic irradiation parameters, including frequency, intensity, and catalyst concentration. By identifying the optimal conditions for ultrasonic catalysis, we aim to maximize the efficiency of the composites. Additionally, we investigated the size-dependent effects of Au NCs (including plasmonic Au NPs) on the performance of Au NCs/TiO₂-based catalysts. Specifically, we compared Au

144 NCs, Au

25 NCs, and plasmonic Au NPs. These findings have the potential to broaden the application of these advanced sonocatalytic materials in diverse industrial and environmental contexts.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Preparation of Au144/ TiO2 Nanocomposite

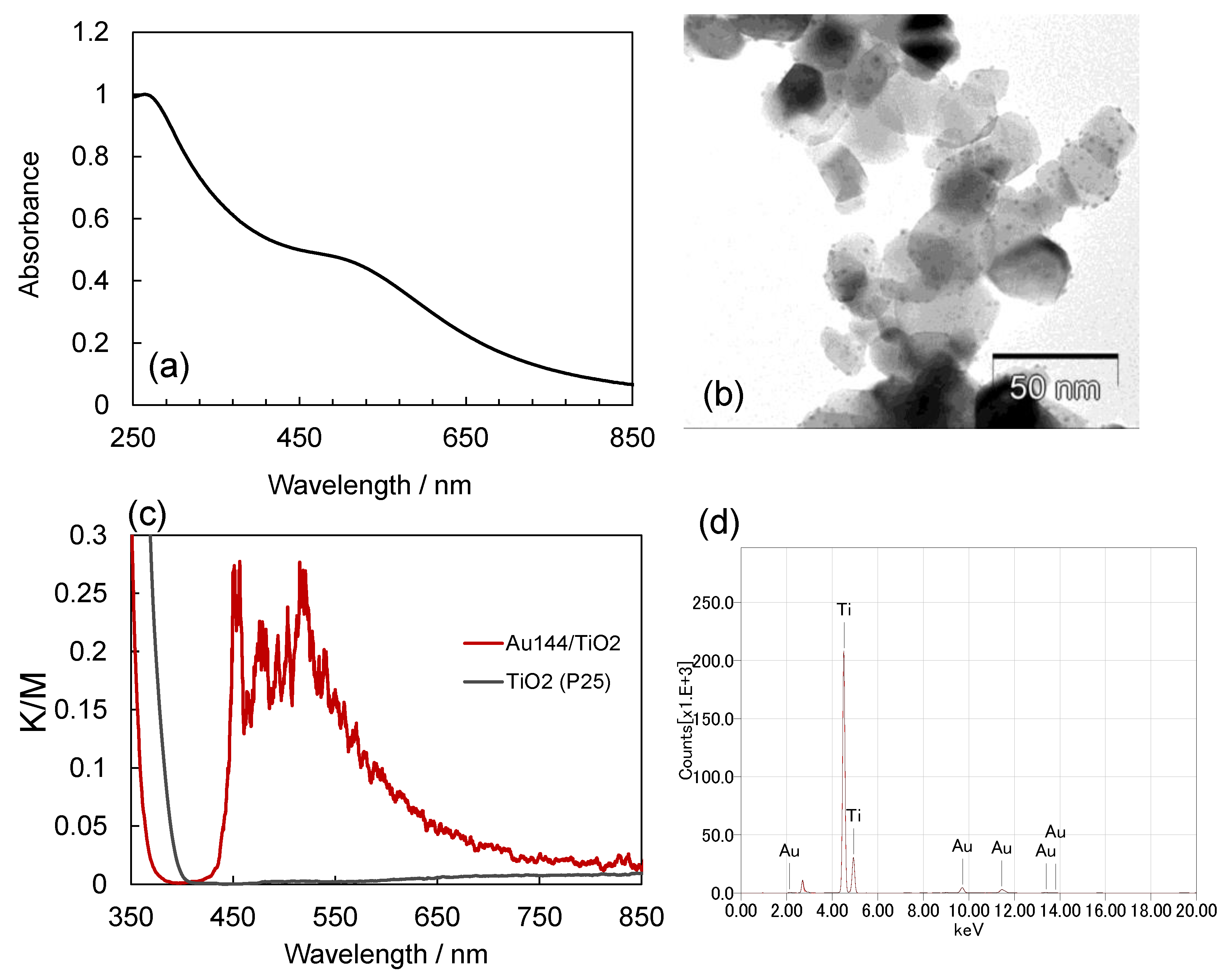

The Au

144/TiO

2 nanocomposite was prepared by adsorbing Au

144 NCs onto TiO

2 NPs. The UV-Vis absorption spectrum of the Au

144(pMBA)

60 NCs exhibited a peak at 280 nm, corresponding to 4–mercaptobenzoic acid (pMBA), along with a broad peak at 520 nm, as shown in

Figure 1a. These spectral features are consistent with previously reported characteristics of Au

144(pMBA)

60 [

30,

31]. TEM analysis confirmed that the Au

144 NCs, comprising 3 wt.%, were successfully loaded onto the TiO

2 NPs without signs of aggregation. The observed particle size was less than 2 nm (

Figure 1b). The reflectance spectra of Au

144 NCs (3.0 wt.%)/TiO

2 were evaluated using the Kubelka-Munk (K-M) function, as shown in

Figure 1c. This analysis demonstrated UV-vis absorption attributed to the loaded Au

144 NCs, which was notably absent in pristine TiO

2. Additionally, X-ray fluorescence (XRF) measurements conducted on the Au

144 NCs (3.0 wt.%)/TiO

2 powder samples determined the gold content to be 2.6 ± 0.2 wt.% (

Figure 1d).

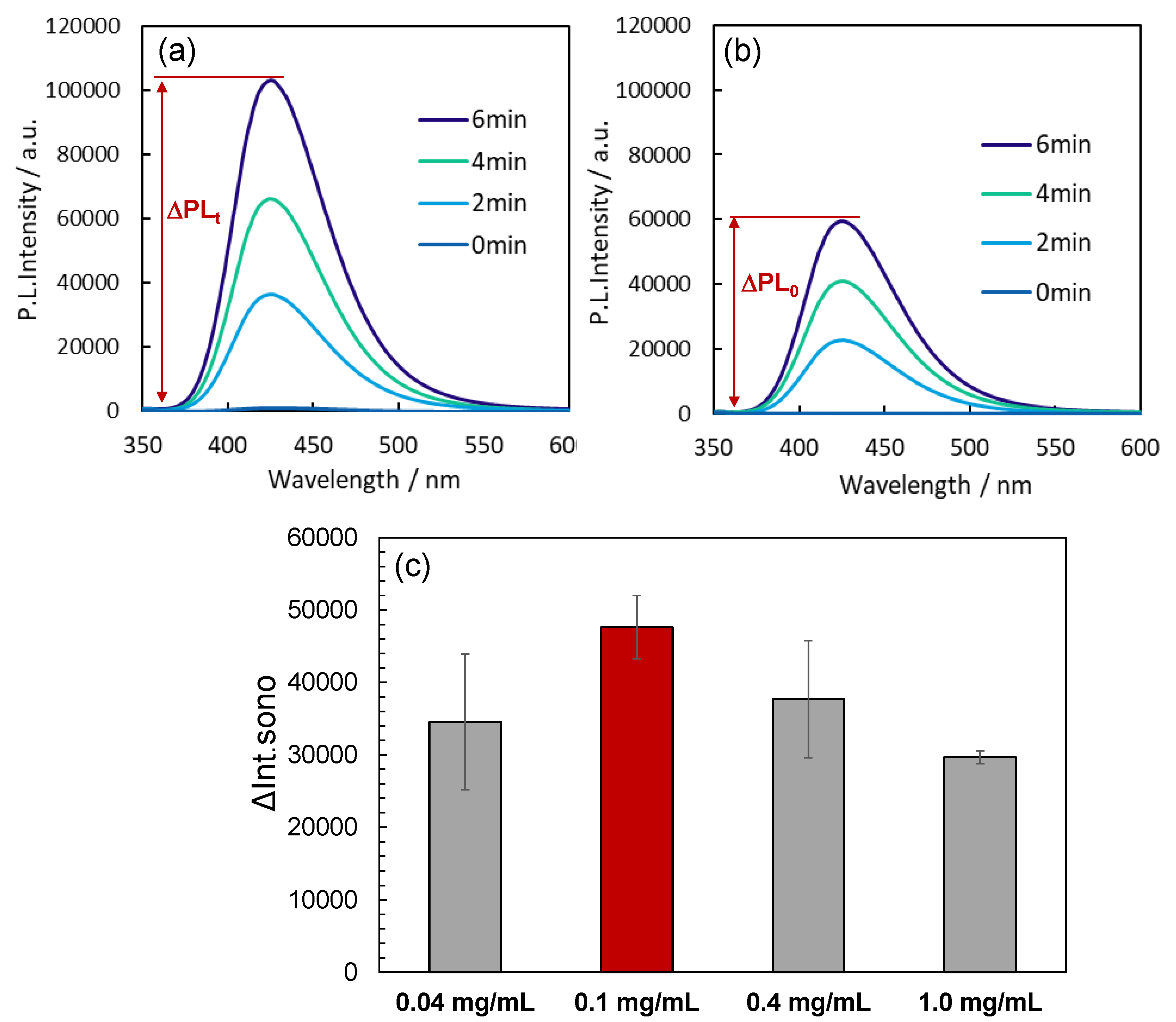

2.2. Sonocatalysis of TiO2 vs Au144/TiO2

When ultrasound was applied to a reaction solution containing the Au

144/TiO

2 sonocatalyst, two primary pathways for the generation of •OH radicals were identified: (i) thermal cleavage of water at localized hot spots, and (ii) water oxidation facilitated by the ultrasonically excited sonocatalysts [

6,

7,

8,

9]. To evaluate the sonocatalyst's ability to produce •OH radicals, we measured the fluorescence intensity increase at 425 nm in a disodium terephthalate(NaTA) solution under ultrasonic conditions at 430 kHz and 5 W, both with and without the sonocatalyst. The presence of •OH radicals was detected using NaTA, which reacts with •OH radicals to form fluorescent 2-hydroxy disodium terephthalate (HTA)[

30]. The observed increase in fluorescence intensity in the catalyst-containing reaction solution (ΔPL

t) was compared to that in the absence of the catalyst (ΔPL

0). The difference, ΔInt

sono = ΔPL

t - ΔPL

0, represents the net contribution of the sonocatalyst to •OH radical generation. This parameter, ΔInt

sono, is depicted in

Figure 2a,b and serves as a quantitative indicator of sonocatalytic activity. The fluorescence intensity increase in the presence of Au

144/TiO

2 was higher than that observed for TiO

2 alone. This finding demonstrates that the deposition of Au

144 NCs onto TiO

2 NPs enhances the sonocatalytic activity, particularly in the generation of •OH radicals.

Catalyst Concentration Dependence: Understanding the dependence of sonocatalytic activity on catalyst concentration is critical for optimizing reaction conditions. An appropriate catalyst concentration ensures maximum •OH radical generation while avoiding potential drawbacks such as light scattering or shielding effects that can occur at higher concentrations. To identify the optimal concentration for the Au144/TiO2 catalyst, we evaluated its performance at varying concentrations.

We measured ΔPLt over a 6-minute period of ultrasonic irradiation at a frequency of 430 kHz and an intensity of 5.0 W on reaction solutions containing different concentrations of Au

144/TiO

2 (0.04, 0.1, 0.4, and 1.0 mg/mL). Plots of ΔInt

sono over the 6-minute duration of irradiation are presented in

Figure 2c

. Across all reaction solutions, a notable increase in ΔInt

sono was observed, indicating the oxidation of NaTA to HTA, accompanied by the generation of •OH radicals via Au

144/TiO

2. The ΔInt

sono values followed the order: 0.1 mg/mL > 0.4 mg/mL > 0.04 mg/mL > 1.0 mg/mL, suggesting that the catalytic activity is maximized at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL. This behavior may be explained by the mechanism of sonocatalyst photoexcitation via sonoluminescence light absorption[

32]. At optimal concentrations, the catalyst efficiently absorbs sonoluminescence light, resulting in enhanced •OH radical generation. However, at excessive concentrations, the catalyst may block the sonoluminescence light, limiting the excitation to catalyst particles near the sonoluminescence source. Consequently, the ability to generate •OH radicals decreases as the concentration increases beyond 0.4 mg/mL. Based on these findings, the optimal concentration of the Au

144/TiO

2 catalyst was determined to be 0.1 mg/mL, and this concentration was maintained for all subsequent experiments to ensure maximum sonocatalytic activity.

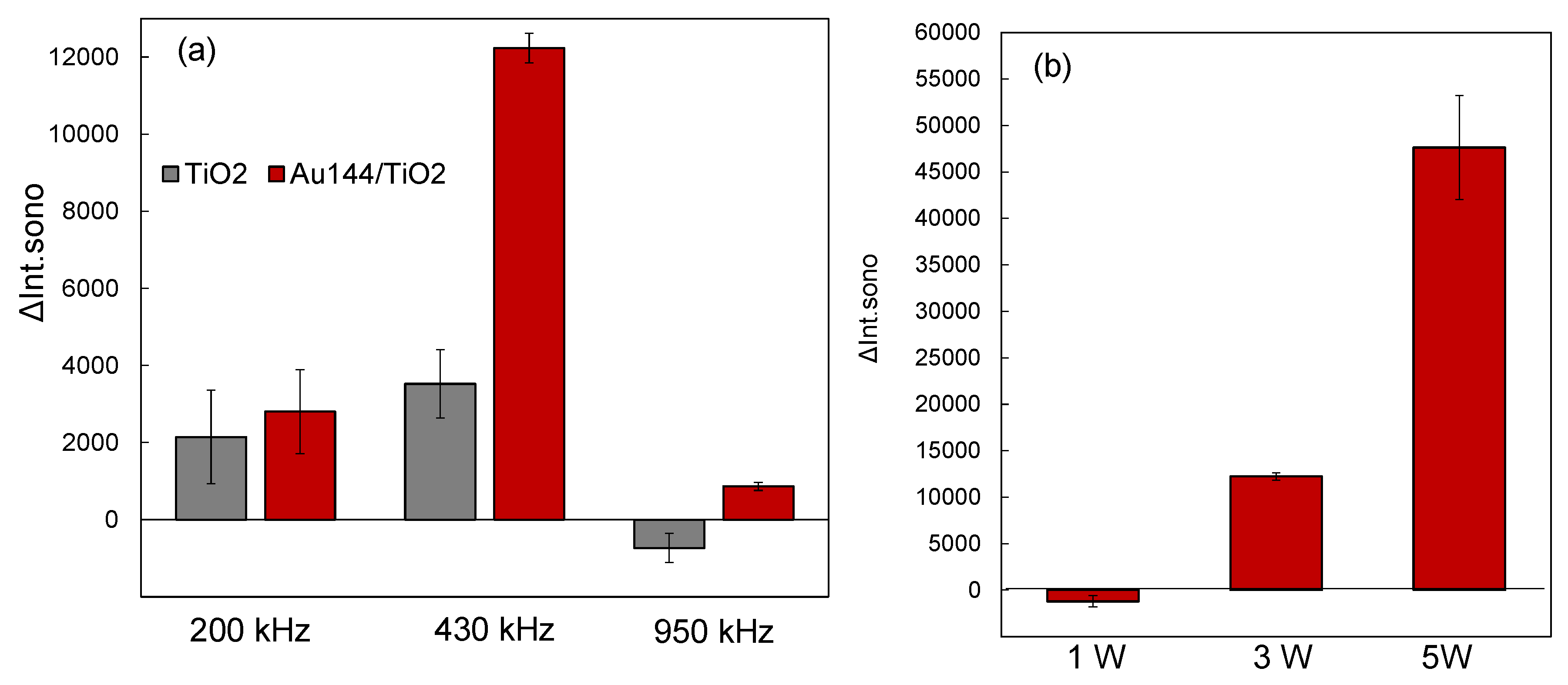

3.3. Ultrasound Frequency and Power Dependence

The efficiency of sonocatalytic reactions is highly dependent on ultrasonic frequency and power, as these parameters directly influence the generation and collapse of cavitation bubbles. The cavitation dynamics vary with frequency and power, affecting the energy distribution and localized conditions at cavitation hotspots [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Understanding the optimal frequency and power for the Au

144/TiO

2 sonocatalyst is crucial for maximizing •OH radical production and ensuring efficient sonocatalytic performance. Furthermore, investigating these parameters provides insight into the mechanisms of ultrasonic activation and the role of cavitation in sonocatalysis.

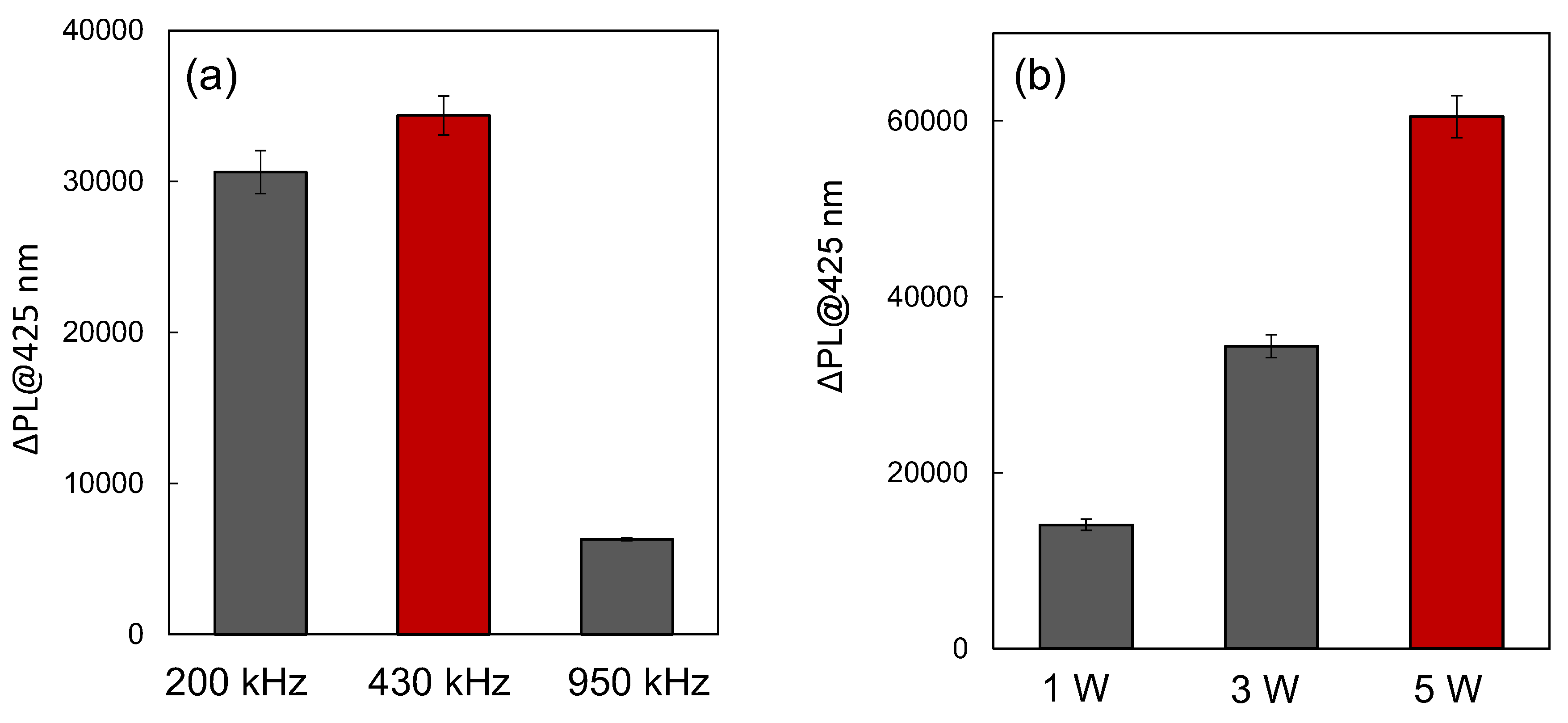

Ultrasound Frequency Dependence: We investigated the influence of ultrasonic frequencies on ΔIntsono at 200 kHz, 430 kHz, and 950 kHz, as shown in

Figure 3a. For all reaction solutions containing Au

144/TiO

2, the ΔInt

sono values were consistently higher than those of pristine TiO

2. The observed effect of ultrasonic frequency on enhanced sonocatalytic activity followed the order: 430 kHz > 200 kHz > 950 kHz. This trend indicates that the generation rate of •OH radicals was maximized at 430 kHz, driven by the superior sonocatalytic performance of the Au

144/TiO

2 catalyst.The frequency dependence can be attributed to variations in cavitation and sonoluminescence efficiency at different frequencies. Cavitation bubbles, formed under ultrasonic irradiation, collapse to produce extreme localized temperatures and pressures, facilitating water pyrolysis and the production of •OH radicals. Measurements of •OH radical production using NaTA aqueous solutions without a catalyst revealed higher bubble temperatures at 430 kHz compared to 200 kHz and 950 kHz (

Figure 4a). At 430 kHz, the amount of •OH radicals increased in correlation with the ultrasonic intensity(

Figure 4b).This finding suggests that water pyrolysis, and consequently •OH radical generation, was most effective at 430 kHz.Previous studies have reported that sonoluminescence intensity peaks at intermediate frequencies, such as 358 kHz, but declines at higher frequencies, such as 1071 kHz [

33,

34]. This behavior supports the conclusion that the efficient ultrasonic excitation of the Au

144/TiO

2 catalyst at 430 kHz arises from the combined thermal effects and sonoluminescence induced by cavitation hotspots. These results emphasize the pivotal role of cavitation dynamics in activating the Au

144/TiO

2 catalyst and enhancing its sonocatalytic efficiency.

Power Dependence of Sonocatalytic Activity: To further evaluate the impact of ultrasonic power on sonocatalytic performance, we analyzed ΔInt

sono at 430 kHz with power levels of 1.0 W, 3.0 W, and 5.0 W, as shown in

Figure 3b. The results revealed a power-dependent increase in ΔInt

sono, following the order: 5.0 W > 3.0 W > 1.0 W. However, power levels exceeding 5 W did not significantly enhance ΔInt

sono and posed risks of equipment damage, such as deterioration of the ultrasonic transmission gel. These observations suggest that 5.0 W represents an optimal power level, balancing effective •OH radical generation with equipment safety. At lower power levels, insufficient cavitation activity limits radical production, while excessively high power levels may lead to inefficiencies caused by energy dissipation or hardware constraints.

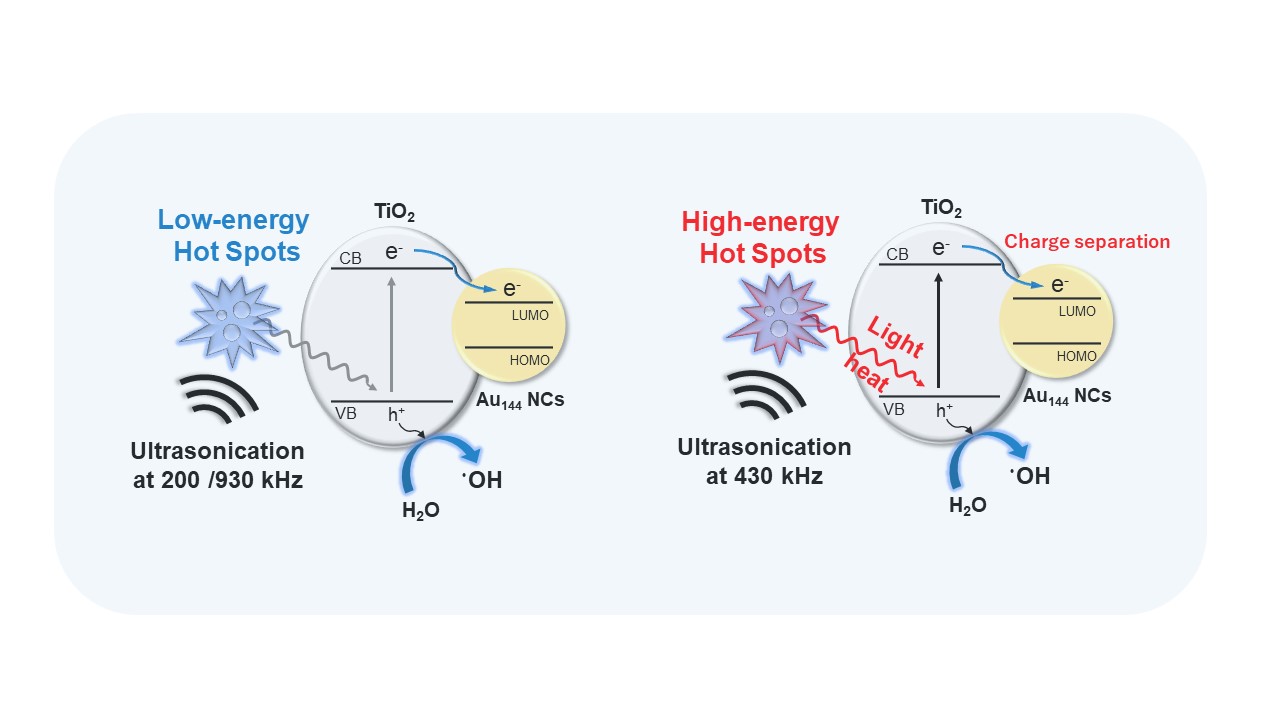

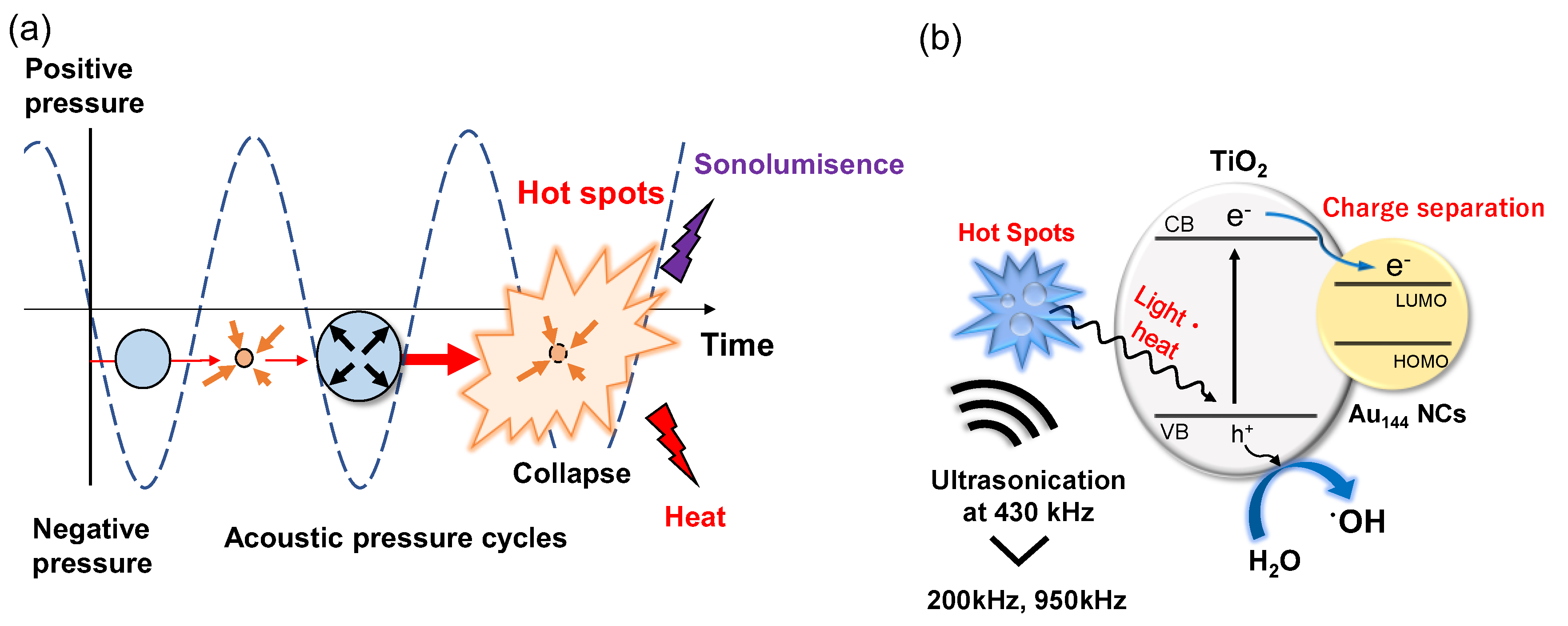

3.4. Mechanistic Insights into Enhanced Sonocatalytic Activity in Au144/TiO2

The enhanced sonocatalytic activity of Au

144/TiO

2 at 430 kHz compared to TiO

2 alone demonstrates the enhanced effects of Au

144 NCs deposited on TiO

2.

Figure 5 illustrates the mechanisms driving enhanced •OH radical generation in the Au

144/TiO

2 sonocatalyst system under ultrasonic irradiation. This model highlights two key processes: ultrasonic cavitation-induced excitation and charge separation, which together contribute to the system's superior sonocatalytic performance. During ultrasonic irradiation, acoustic pressure cycles lead to the formation, growth, and collapse of cavitation bubbles, as depicted in

Figure 5a. The collapse of these bubbles creates extreme localized conditions, such as transiently high temperatures and pressures at cavitation hot spots. These conditions induce thermal effects and the UV sonoluminescence in the wavelength range of 200–400nm [

32], which promote the excitation of electrons in TiO₂ from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB). The excited electrons are subsequently transferred to the Au

144 NCs. This efficient electron migration suppresses electron-hole recombination, thereby prolonging the lifetime of charge carriers. The enhanced charge separation facilitates more effective water oxidation, increasing the production of •OH radicals, as depicted in

Figure 5b.

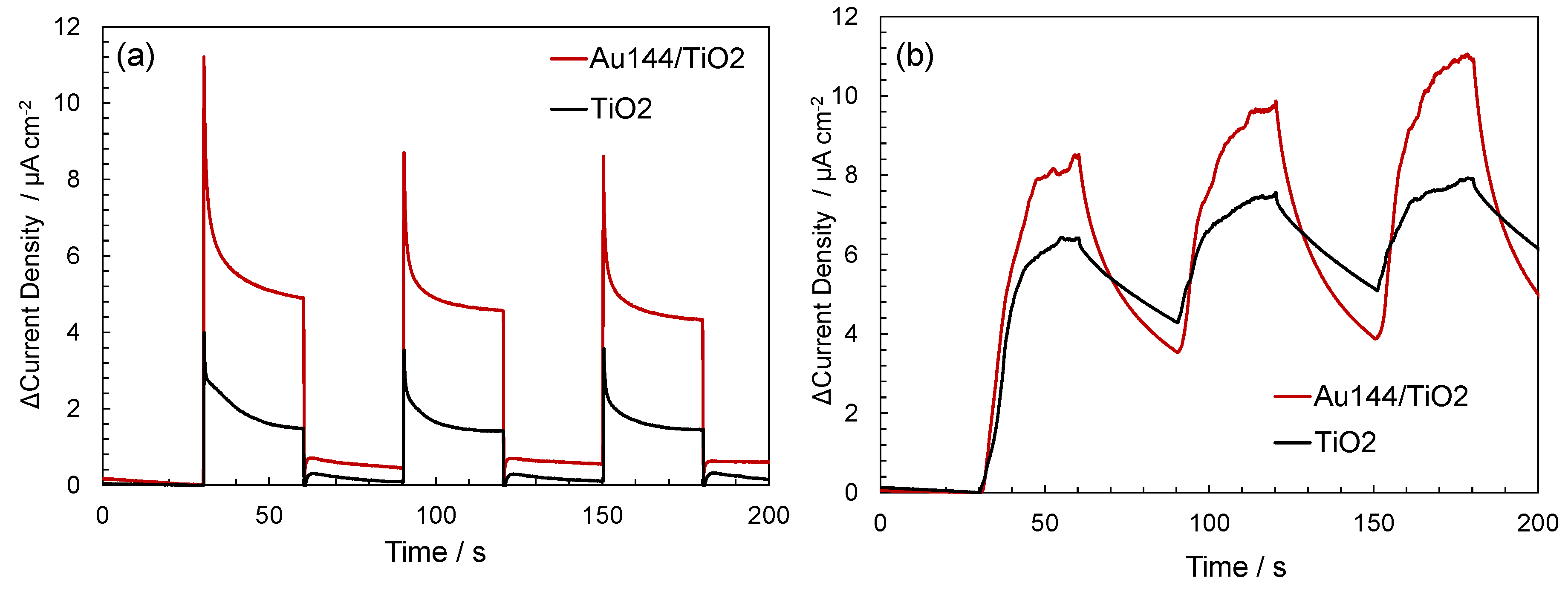

To validate this hypothesis, transient photocurrent and sonocurrent measurements were conducted for Au

144/TiO

2 composites and bare TiO

2. Transient photocurrent and sonocurrent measurements serve as direct experimental evidence for enhanced charge separation in photocatalytic and sonocatalytic systems. A higher photocurrent or sonocurrent indicates more efficient charge carrier generation and reduced recombination of electron-hole pairs. These measurements are thus widely used to evaluate the ability of a material to facilitate charge separation under irradiation or ultrasonic excitation [

35]. As shown in

Figure 6a, Au

144/TiO

2 exhibited a significantly higher photocurrent density under light exposure compared to bare TiO

2, indicating improved charge separation and transfer. Similarly, transient sonocurrent measurements at 430 kHz (

Figure 5b) demonstrated enhanced electron generation in Au

144/TiO

2 compared to TiO

2 alone. These findings provide strong evidence that Au

144 NCs play a crucial role in facilitating charge separation and improving the overall sonocatalytic performance of the system.

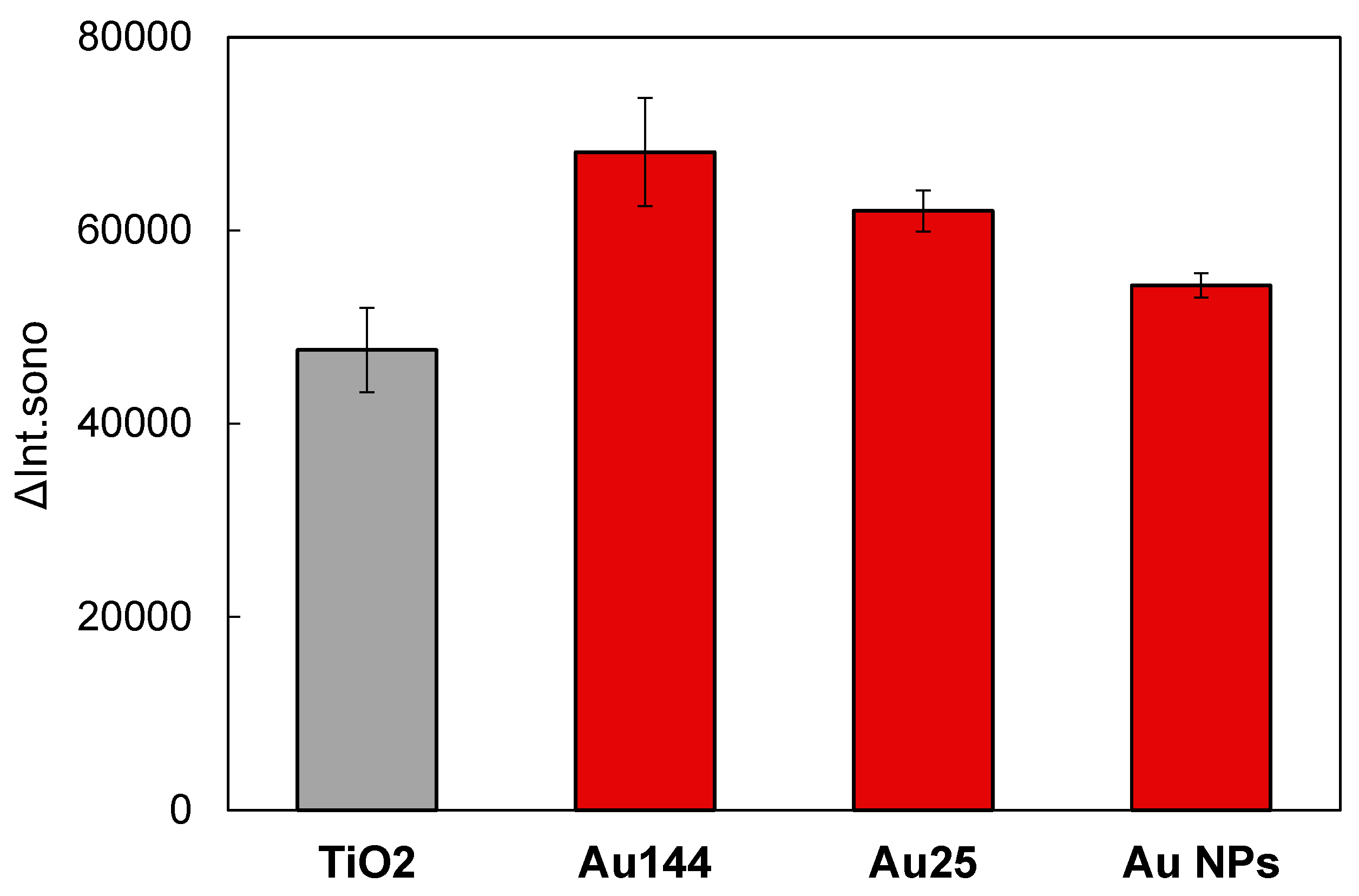

3.5. Size Dependence in Sonocatalytic Activity in Au/TiO2

Understanding the size-dependent effects of Au NCs is crucial for optimizing TiO₂-based catalytic systems, particularly in addressing charge separation challenges. This study examines how the size of Au NCs influences the sonocatalytic performance of Au/TiO₂ catalysts. The catalytic efficiency of variously sized Au NCs, including plasmonic Au nanoparticles (NPs), was evaluated (

Figure 7). The ΔInt

sono values, which represent sonocatalytic efficiency, followed the order: Au₁₄₄ > Au₂₅ > plasmonic Au NPs > bare TiO₂. These findings highlight the superior performance of Au NCs compared to plasmonic Au NPs within the Au/TiO₂ catalyst system.

Among the studied catalysts, Au₁₄₄ NCs exhibited the highest performance, outperforming Au₂₅ NCs by achieving an optimal balance between electron migration and charge separation. Smaller clusters, such as Au₂₅ NCs, are known to inject photoexcited electrons into the TiO₂ conduction band upon light absorption [

36]. However, this bidirectional electron transfer between Au₂₅ NCs and TiO₂ increases the frequency of charge recombination events, potentially reducing the efficiency of sonocatalytic reactions. In contrast, ultra-small Au NCs (< 2 nm) possess exceptionally high surface energy at the atomic level, significantly enhancing their catalytic activity. Larger Au NPs (~2.4 nm), with a relatively reduced reactive surface area, demonstrate diminished catalytic performance.

The transition from Au NCs to plasmonic Au NPs, as well as the size-dependent effects and electronic structure variations, remains only partially understood. Future research should focus on elucidating the interplay between size and electronic structure using advanced spectroscopy and computational modeling. These insights will deepen our understanding of Au-based catalytic systems, emphasizing the critical role of Au NC size and electronic structure in enhancing sonocatalytic performance..

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents

Hydrogen tetrachloroaurate (III) tetrahydrate (HAuCl4·4H2O), and methanol were sourced from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation. Disodium terephthalate (NaTA) and 4–mercaptobenzoic acid (pMBA) were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co. Ltd. Sodium borohydride (99%) (NaBH4) was procured from Sigma–Aldrich. The TiO2 utilized was Aeroxide®P25. Deionized water was prepared using a water distillation apparatus (Aquarius RFD250; ADVANTEC).

3.2. Instruments

UV-visible (UV-vis) absorption spectroscopy and steady-state fluorescence spectroscopy were performed using a JASCO V-670 spectrophotometer (JASCO Corp., Japan) and RF-6000 spectrofluorometer (Shimadzu Corp., Japan), respectively. Diffuse reflectance UV-vis spectra were acquired using an Ocean Optics DH-2000-BAL deuterium-tungsten-halogen light source and an Ocean Optics USB4000 compact fiber optic spectrometer (Ocean Optics, Dunedin, FL, USA). The Au loading on TiO2 NPs was quantified using an energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer (JSX-1000S Element Eye; JEOL Ltd., Japan). The crystal structure of the TiO2 NPs powder was analyzed by X-ray diffractometry (XRD, D2 Phaser, Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany), employing a Cu-Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5406 Å) over a 2θ range of 10–80°, at an accelerating voltage of 30 kV and a current of 10 mA. The size and morphology of Au144/TiO2 were characterized using transmission electron microscopy (TEM; JEOL JEM2100 microscope operating at 200 kV).

3.3. Synthesis of Au144(pMBA)60

According to our previous study [

30,

31], Au

144(pMBA)

60 NCs (Au

144 NCs) were synthesized at an ambient temperature by mixing HAuCl4 aqueous solution (25 mM, 3 mL), pMBA solution (75 mM, 3 mL), deionized water (6.5 mL), and methanol (12.5 mL), with methanol comprising 50% of the total volume of 25 mL. After stirring the solution overnight until it turned colorless, NaBH4 was added in cold deionized water (500 mM, 227 µL), and the mixture was stirred for an additional 2 h. After the addition of methanol, the NCs were isolated by centrifugation, and the purification step was repeated. Finally, the NCs were dried under reduced pressure to obtain the purified product.

3.4. Synthesis of Au25(pMBA)18

The synthesis of Au

25(pMBA)

18 nanoclusters (Au

25 NCs) was conducted at room temperature in air, following a previously reported method [

30]. The successful synthesis of Au

25(pMBA)

18 was confirmed through UV–vis spectroscopy, which revealed two prominent absorption bands at 450 nm and 670 nm, along with a broad shoulder around 800 nm. These spectral features align well with previously reported characteristics of Au

25 NCs [

30].

3.5. Synthesis of Au Nanoparticles

Gold nanoparticles (Au NPs) with a size of 2.4 nm were synthesized under ambient conditions and at room temperature following the reported procedure [

37]. Initially, 2.7 mL of the 28 mM HAuCl₄ solution and 2.4 mL of the 95 mM pMBA solution were mixed. This was followed by the gradual addition of 20 mL of the 106 mM NaOH solution. The resulting reaction mixture was stirred continuously for 20 hours to ensure complete interaction of the components. The final concentrations of the key reactants in the reaction mixture were as follows: HAuCl₄, 3 mM; pMBA, 9 mM; and NaOH, 100 mM. To reduce the gold ions, 28.3 mg of NaBH₄ was dissolved in 5 mL of cold deionized water, yielding a 150 mM NaBH₄ solution. Subsequently, a 0.25 mL aliquot of this NaBH₄ solution was added to the reaction mixture, maintaining a molar ratio of NaBH₄:Au = 1:2. The reaction was stirred overnight to facilitate reduction. To complete the synthesis, 29.2 mg of NaCl was added to the reaction mixture to achieve a final NaCl concentration of 10 mM. Methanol (80% v/v) was then introduced, and the mixture was centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 minutes. The resulting precipitate was collected, dried, and stored, yielding the final Au NPs. The successful synthesis of Au NPs was confirmed through UV–vis spectroscopy, which revealed a plasmonic absorption band at around 520 nm [

37].

3.6. Preparation of Au /TiO₂ Composites

Following the method described in our previous report [

30], a Au

144 NCs-supported TiO₂ composite was fabricated at ambient temperature. In a reaction tube, 8 mL of an aqueous TiO₂ dispersion (1 mg/mL) was combined with 80 μL of an aqueous Au144 NC solution (3.0 mg/mL). The mixture was stirred at 800 rpm for 17 hours to promote the adsorption of Au

144 NCs onto the TiO₂ particles, yielding a composite with a 3 wt.% loading of Au

144 NCs on TiO₂. After stirring, the mixture was centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 15 minutes to separate the supernatant, leaving the Au

144 NCs (3 wt.%)/TiO₂ composite as a precipitate. Similarly, composites of Au

25 NCs (3 wt.%) and Au NPs(3 wt.%) supported on TiO₂ were prepared using the same procedure.

3.7. Evaluation of Sonocatalytic Activity

The sonocatalytic activity of Au /TiO₂ nanocomposites was assessed by measuring the generation of •OH radicals from water under ultrasonic stimulation. The presence of •OH radicals was detected using sodium terephthalate (NaTA), which reacts with •OH radicals to form fluorescent 2-hydroxy disodium terephthalate (HTA)[

30]. The production of •OH radicals was monitored by measuring the fluorescence intensity of HTA at 425 nm (excitation at 315 nm). To ensure consistent ultrasonic transmission and eliminate air gaps, an ultrasonic transmission gel was applied between the transducer and a plastic dish during the experiment. The experimental setup was maintained at a constant temperature of 18 ± 2 °C using a temperature-controlled water bath equipped with a precision thermostat. The reaction solution was subjected to ultrasonic irradiation at intervals of 0, 2, 4, and 6 minutes using a QUAVA Mini QR-003 ultrasonic device at frequencies of 200 kHz, 430 kHz, and 930 kHz. After each irradiation, the mixture was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 minutes to separate the catalyst. The fluorescence intensity of the supernatant was measured at 425 nm to quantify the production of •OH radicals.

3.8. Transient Photocurrent/Sonocurrent Measuremetns in TiO2 and Au144(3 wt%) /TiO2.

To determine whether supporting Au144 NCs on TiO₂ improves charge separation, transient photocurrent and ultrasonic current responses were measured using a three-electrode cell connected to a potentiostat (BAS, ALS611 DE). The measurement parameters were as follows: mode—Amperometry i-t Curve; initial potential—-0.1 V; sample interval—0.1 s. A Pt mesh served as the counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl electrode (BAS, RE-1B) was used as the reference electrode. The working electrode was prepared by dispersing 5 mg of the catalyst in a mixture of 375 µL of water containing 20 wt.% Nafion (50 µL) and 125 µL of 2-propanol. A 40 µL aliquot of this dispersion was applied onto a 1 cm² fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) glass conductive surface and dried under reduced pressure overnight.

All measurements were performed in a 0.2 M Na₂SO₄ aqueous solution. The transient photocurrent response was recorded under UV light (394 nm, 22.46 mW/cm²) using a UV Spotlight Source (L5662, Hamamatsu Photonics). For the transient ultrasonic current response, a 200 kHz, 50 W ultrasound device (QUAVA mini QR-003, Kaijo Corporation) was employed. To minimize temperature elevation in the electrolyte due to ultrasonic irradiation, the reaction vessel was placed on a cooling plate submerged in a water-filled container

4. Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the sonocatalytic capabilities of Au144/TiO2 composites, focusing on the generation of •OH radicals under varying ultrasonic frequencies, power levels, and NC sizes. Our findings demonstrate that the Au144/TiO2 composite exhibits superior sonocatalytic performance, particularly at an ultrasonic frequency of 430 kHz and a power setting of 5.0 W. This heightened activity is attributed to the optimal cavitation dynamics achieved at 430 kHz, which maximizes localized thermal effects and sonoluminescence, facilitating efficient •OH radical generation.

The size dependence of the Au NCs was also found to play a critical role in determining the sonocatalytic performance in Au/TiO2 composites. The comparative analysis revealed a clear efficiency trend: Au144 > Au25 > plasmonic Au NPs > bare TiO2. Larger clusters like Au144 demonstrated superior activity due to their discrete electronic structures, which enable better energy alignment with the TiO2 conduction band, facilitating enhanced charge separation and prolonged carrier lifetimes. In contrast, plasmonic Au NPs were less efficient under ultrasonic activation.

This research highlights the practical potential of the Au144/TiO2 system for applications in environmental remediation and medical treatments. The insights gained into the interplay between ultrasonic frequency, cavitation dynamics, and nanocluster size offer a pathway for developing advanced sonocatalytic materials. Ultimately, this study contributes to the broader field of chemical physics by emphasizing the significance of NP-enhanced sonocatalysis in addressing global challenges, including pollution control and sustainable healthcare solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Hideya Kawasaki formulated the overarching research goals and aims, while Takaaki Tsurunishi framed the specific hypotheses to be tested;Methodology: Takaaki Tsurunishi and Yuzuki Furui designed the experimental and analytical processes; Investigation: Takaaki Tsurunishi conducted the primary experiments and data collection; Writing – Original Draft Preparation: Takaaki Tsurunishi drafted the manuscript; Writing – Review & Editing: Hideya Kawasaki provided critical review, commentary, and revisions to the manuscript;Visualization: Takaaki Tsurunishi created all diagrams and visual aids that helped to interpret data; Supervision: Hideya Kawasaki oversaw the project, including coordination and strategic guidance; Project Administration: Hideya Kawasaki managed the project administration, including compliance with funding and ethical requireme

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant No. JP 22H01915) and Kansai University Fund for Supporting formation of strategic Research Centers(University initiative type).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gligorovski, S.; Strekowski, R.; Barbati, S.; Vione, D. Environmental Implications of Hydroxyl Radicals (•OH). Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 13051–13092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahbub, P.; Duke, Mi. Scalability of Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) in Industrial Applications: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Luo, R.; Liang, X.; Wu, Q.; Gong, C. Recent Advances in Enhancing Reactive Oxygen Species Based Chemodynamic Therapy. Chinese Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 2213–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Xu, Q.; Wang, W.; Shao, J.; Huang, W.; Dong, X. Type I Photosensitizers Revitalizing Photodynamic Oncotherapy. Small 2021, 17, 2006742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Shah, M.U.H. Modification Strategies of TiO₂-Based Photocatalysts for Enhanced Visible Light Activity and Energy Storage Ability: A Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurahman, M.H.; Abdullah, A.Z.; Shoparwe, N.F. A Comprehensive Review on Sonocatalytic, Photocatalytic, and Sonophotocatalytic Processes for the Degradation of Antibiotics in Water: Synergistic Mechanism and Degradation Pathway. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 413, 127412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, P.; Park, B.; Choi, J.; Thokchom, B.; Pandit, A.B.; Khim, J. A Review on Heterogeneous Sonocatalyst for Treatment of Organic Pollutants in Aqueous Phase Based on Catalytic Mechanism. Ultrasonics Sonochem. 2018, 45, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhong, X.; Gong, F.; Chao, Y.; Cheng, L. Newly Developed Strategies for Improving Sonodynamic Therapy. Mater. Horiz. 2020, 7, 2028–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Du, J.; Miao, Y.; Li, Y. Recent Developments of Inorganic Nanosensitizers for Sonodynamic Therapy. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2023, 12, 2300234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Qian, H.; Cheng, L. Titanium-Based Sonosensitizers for Sonodynamic Cancer Therapy. Appl. Mater. Today 2021, 25, 101215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, A.; Seyedhamzeh, M.; Yuan, M.; Agarwal, T.; Sharifi, I.; Mohammadi, A.; Kelicen-Uğur, P.; Hamidi, M.; Malaki, M.; Al Kheraif, A.A.; Cheng, Z.; Lin, J. Titanium-Based Nanoarchitectures for Sonodynamic Therapy-Involved Multimodal Treatments. Small 2023, 19, 22062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priya, M.H.; Madras, G. Kinetics of TiO₂-Catalyzed Ultrasonic Degradation of Rhodamine Dyes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khataee, A.; Sheydaei, M.; Hassani, A.; Taseidifar, M.; Karaca, S. Sonocatalytic Removal of an Organic Dye Using TiO₂/Montmorillonite Nanocomposite. Ultrasonics Sonochem. 2015, 22, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khataee, A.; Kayan, B.; Gholami, P.; Kalderis, D.; Akay, S. Sonocatalytic Degradation of an Anthraquinone Dye Using TiO₂-Biochar Nanocomposite. Ultrasonics Sonochem. 2017, 39, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Lee, D.; Hong, S.; Khan, S.; Darya, B.; Lee, J.Y.; Chung, J.; Cho, S.H. Investigation of the Synergistic Effect of Sonolysis and Photocatalysis of Titanium Dioxide for Organic Dye Degradation. Catalysts 2020, 10, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Ma, H. Degradation of Rhodamine B in Water by Ultrasound-Assisted TiO₂ Photocatalysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhmohammadi, A.; Asgari, E.; Nourmoradi, H.; Fazli, M.M.; Yeganeh, M. Ultrasound-Assisted Decomposition of Metronidazole by Synthesized TiO₂/Fe₃O₄ Nanocatalyst: Influencing Factors and Mechanisms. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonnalagadda, U.S.; Su, X.; Kwan, J.J. Nanostructured TiO₂ Cavitation Agents for Dual-Modal Sonophotocatalysis with Pulsed Ultrasound. Ultrasonics Sonochem. 2021, 73, 105530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepagan, V.G.; You, D.G.; Um, W.; Ko, H.; Kwon, S.; Choi, K.Y.; Yi, G.R.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, D.S.; Kim, K.; Kwon, I.C.; Park, J.H. Long-Circulating Au-TiO₂ Nanocomposite as a Sonosensitizer for ROS-Mediated Eradication of Cancer. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 6257–6264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wu, T.; Dai, W.; Dong, H.; Zhang, X. TiO₂ Nanosheets with the Au Nanocrystal-Decorated Edge for Mitochondria-Targeting Enhanced Sonodynamic Therapy. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 9105–9114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Pan, Q.; Ling, Y.; Guo, J.; Huo, Y.; Xu, C.; Xiong, M.; Yuan, M.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, M.; Lin, J. Gold–Titanium Dioxide Heterojunction for Enhanced Sonodynamic Mediated Biofilm Eradication and Peri-Implant Infection Treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 413, 127412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, J.; Cao, Y.; Chai, O.J.H.; Xie, J. Ligand Design in Ligand-Protected Gold Nanoclusters. Small 2021, 17, 2004381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Yang, X.; Guo, Y.; Kawasaki, H. Review on Gold Nanoclusters for Cancer Phototherapy. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2023, 6, 4504–4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albright, E.L.; Levchenko, T.I.; Kulkarni, V.K.; Sullivan, A.I.; DeJesus, J.F.; Malola, S.; Takano, S.; Nambo, M.; Stamplecoskie, K.; Häkkinen, H.; Tsukuda, T.; Crudden, C.M. Atomically Precise Gold Nanoclusters: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 5759–5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawawaki, T.; Negishi, Y.; Kawasaki, H. Photo/Electrocatalysis and Photosensitization Using Metal Nanoclusters for Green Energy and Medical Applications. Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Hirayama, D.; Ikeda, A.; Ishimi, M.; Funaki, S.; Samanta, A.; Kawawaki, T.; Negishi, Y. Atomically Precise Thiolate-Protected Gold Nanoclusters: Current Status of Designability of the Structure and Physicochemical Properties. Aggregate 2023, 4, e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Du, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Shao, Y.; Jin, R. Size Effects of Atomically Precise Gold Nanoclusters in Catalysis. Precis. Chem. 2023, 1, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, K.; Hikosou, D.; Inui, A.; Yamamoto, K.; Yagi, J.; Saita, S.; Kawasaki, H. Ultrasonic Activation of Water-Soluble Au₂₅(SR)₁₈ Nanoclusters for Singlet Oxygen Production. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 26644–26652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagi, J.; Ikeda, A.; Wang, L.-C.; Yeh, C.-S.; Kawasaki, H. Singlet Oxygen Generation Using Thiolated Gold Nanoclusters under Photo- and Ultrasonic Excitation: Size and Ligand Effect. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 19693–19703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, K.; Ikeda, A.; Inui, A.; Yamamoto, K.; Kawasaki, H. TiO₂-Supported Au₁₄₄ Nanoclusters for Enhanced Sonocatalytic Performance. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 155, 124702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Xia, N.; Liao, L.; Zhu, M.; Jin, F.; Jin, R.; Wu, Z. Unraveling the Long-Pursued Au₁₄₄ Structure by X-Ray Crystallography. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaat7259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Didenko, Y.T.; Pugach, S.P. Spectra of Water Sonoluminescence. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 9742–9749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasui, K. Production of O Radicals from Cavitation Bubbles under Ultrasound. Molecules 2022, 27, 4788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckett, M.A.; Hua, I. Impact of Ultrasonic Frequency on Aqueous Sonoluminescence and Sonochemistry. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 3796–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; He, Q.; Wu, M.; Xu, Y.; Sun, P.; Dong, X. Piezoelectric Polarization Promoted Spatial Separation of Photoexcited Electrons and Holes in Two-Dimensional g-C₃N₄ Nanosheets for Efficient Elimination of Chlorophenols. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 421, 126696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Naveen, M.H.; Abbas, M.A.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Bang, J.H. Photoelectrochemistry of Au Nanocluster-Sensitized TiO₂: Intricacy Arising from the Light-Induced Transformation of Nanoclusters into Nanoparticles. ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaltiel, L.; Shemesh, A.; Raviv, U.; Barenholz, Y.; Levi-Kalisman, Y. Synthesis and Characterization of Thiolate-Protected Gold Nanoparticles of Controlled Diameter. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 28486–28493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).