1. Introduction

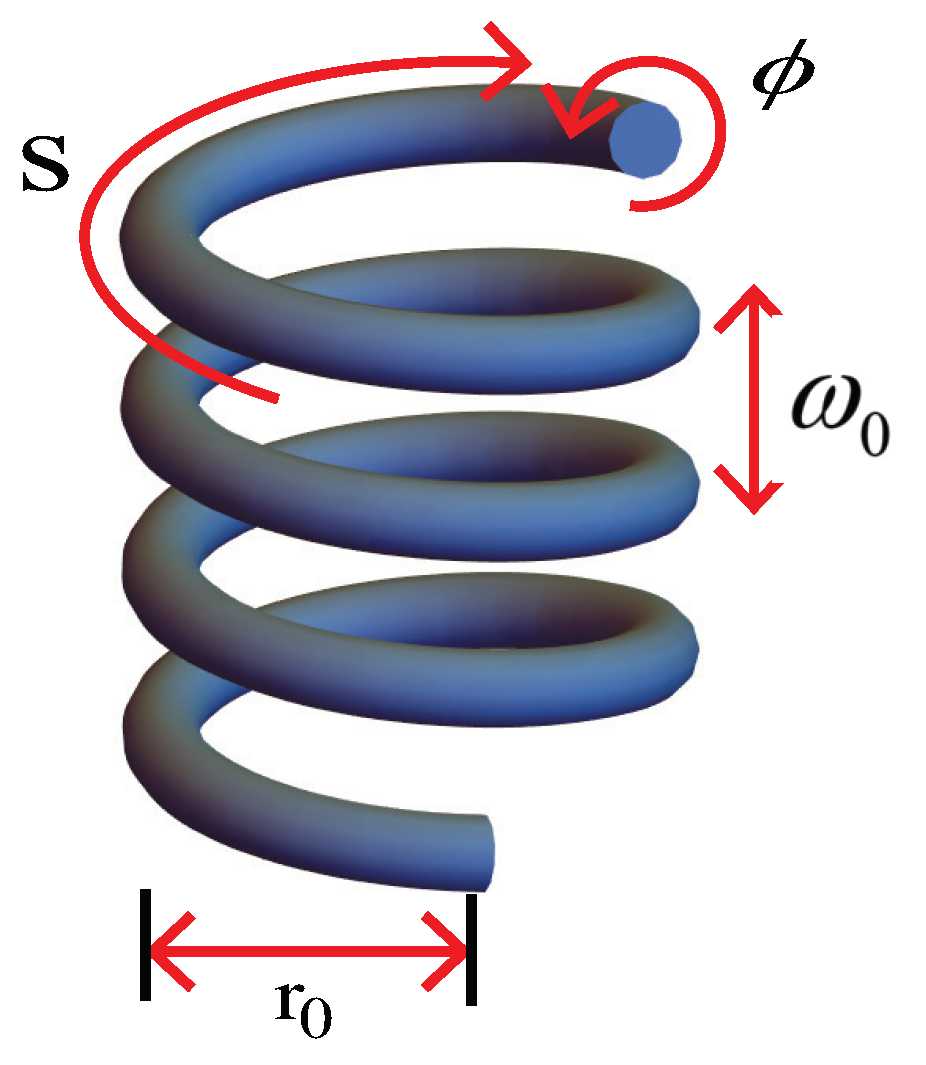

CNT springs, also known as helically coiled CNT, have garnered significant attention because of their exceptional mechanical and electrical properties. Initially predicted by Ihara.[

1,

2]. And Dunlap[

3], helically coiled CNT was later experimentally realized by Zhang [

4], who successfully synthesized coiled carbon nanotubes and fibers.Further insights into the growth mechanisms and microstructural properties of helically coiled CNTs were provided by Hernadi [

5], who explored the influence of catalyst preparation on coil formation and proposed mechanisms underlying their helical structures. These structures are defined by their coil diameter and pitch, determined by the periodic incorporation of pentagon and heptagon pairs into the hexagonal carbon lattice.This geometric modification results in positively and negatively curved surfaces, significantly enhancing their mechanical and electronic properties. As a result, CNT springs exhibit remarkable tensile strength and energy density [

6], making them ideal for applications requiring compact and lightweight energy storage solutions. Furthermore, CNT springs, which can be regarded as a type of CNT yarn, provide a versatile platform for analyzing applications, particularly in scenarios where their unique electromechanical coupling enables the generation of electrical current under strain.

CNT springs have been employed in diverse applications, including thermoelectric textiles that harvest heat energy from temperature gradients, achieving high power densities of 51.5 mW/m² for wearable electronics and healthcare monitoring[

7]. Ferritin biscrolled CNT yarns enhance energy harvesting capabilities in biofluid environments, making them excellent candidates for implantable medical devices [

8]. Strain sensors based on CNT/polymer composites exhibit stretchability exceeding

, enabling precise motion capture and real-time feedback for robotics and wearable devices[

9]. CNT-based artificial muscles achieve strains of up to

and generate stresses over 20 times greater than human skeletal muscle, suitable for intelligent robotics, actuators , and clamping devices [

10]. High-temperature annealed CNT yarns exhibit enhanced electrical conductivity, reaching values of 1680 S/cm due to improved graphitization, supporting energy storage and thermal management systems [

11]. Bio-inspired CNT yarns, designed with ester bond cross-linkages, demonstrate enhanced toughness and multifunctionality for smart textiles and advanced wearable technologies [

12]. Furthermore, CNT springs have enabled the development of highly sensitive sensors capable of detecting environmental changes such as pressure, temperature, and strain, providing precise measurements for structural health monitoring and wearable technology [

13,

14,

15,

16].

Beyond their mechanical applications, CNT springs possess unique electromechanical coupling properties. When subjected to strain, they can generate electrical current, aligning with experimental observations of their behavior under deformation [

17,

18]. This strain-induced current generation highlights their potential for energy harvesting[

19,

20,

21,

22,

23] and sensing technologies [

24,

25]. Recent advancements have demonstrated that CNT-based yarn harvesters can efficiently convert mechanical energy, such as tensile or torsional forces, into electrical energy without requiring an external bias. These systems exhibit dynamic responses, such as significant changes in capacitance and open-circuit voltage under strain [

26], underscoring their efficiency and potential in energy conversion applications. For example, CNT harvesters exhibit time-dependent open-circuit voltage (OCV) and short-circuit current (SCC) characteristics generated by a coiled cone-spun harvester during 1-Hz sinusoidal stretches to

, displaying asymmetric electrical reponses. When stretched to 30% strain, the harvester’s capacitance decreased by

, while its OCV increased by 140 mV, highlighting these systems’ dynamic response and efficiency in energy conversion applications [

27]. Despite these advancements, there is limited theoretical research exploring the mechanisms of current flow and the reasons behind the asymmetric form of these electrical responses.

Strain-induced modifications to the electronic properties of CNT springs stem from pseudo-vector potentials and fictitious gauge fields, as illustrated in related studies on 2D materials like graphene [

28,

29,

30]. Graphene’s electronic behavior under mechanical stress, characterized by phenomena such as Aharonov-Bohm interference [

31,

32] and strain-induced vector potentials, demonstrates the profound interplay between structural deformations and electronic properties. Similarly, CNT springs exhibit strain-dependent electrical behavior, with mechanical deformation influencing current flow and transport characteristics Despite these promising experimental advancements, the theoretical mechanisms underlying current generation and the observed asymmetric electrical responses in strained CNT springs remain underexplored. Recent studies indicate that strain on 2D materials [

33,

34] can induce current generation without an electric bias, suggesting parallels with the behavior of CNT springs. However, a comprehensive theoretical framework to explain these mechanisms is lacking.

The motivation for this study arises from the need to bridge the gap between experimental observations and theoretical understanding of the mechanisms underlying current flow in CNT springs under strain, mainly the reasons behind their asymmetric electrical responses. This paper is organized as follows: In the Dirac Equation in Curved Spacetime section, the properties of an electron gas confined on the curved surface of CNT springs are analyzed using the (2 + 1)-dimensional Dirac equation. The curvature of the CNT springs generates periodic scalar and pseudo-gauge potentials, which, along with the coupling between the circumference and axial motion, significantly influence the electron dynamics. In the Adiabatic Evolution section, the effect of strain on the CNT spring is described, incorporating time-dependent variations in the Lamé coefficient and curvature parameter to explore the system’s response. The time-dependent Hamiltonian is constructed, and the instantaneous eigenstates are determined to characterize the strain-induced electronic behavior. The continuity equation and equivalent circuit section focus on the conservation of charge, relating mechanical strain to electronic dynamics and providing an equivalent circuit model to explain the observed current and charge distributions. Finally, the results section presents the energy band structures and current generation mechanisms, highlighting the asymmetric electrical responses arising from the curvature and strain effects. This work provides theoretical insights that align with experimental observations and demonstrates the potential of CNT springs for energy harvesting and sensing applications.

3. Results

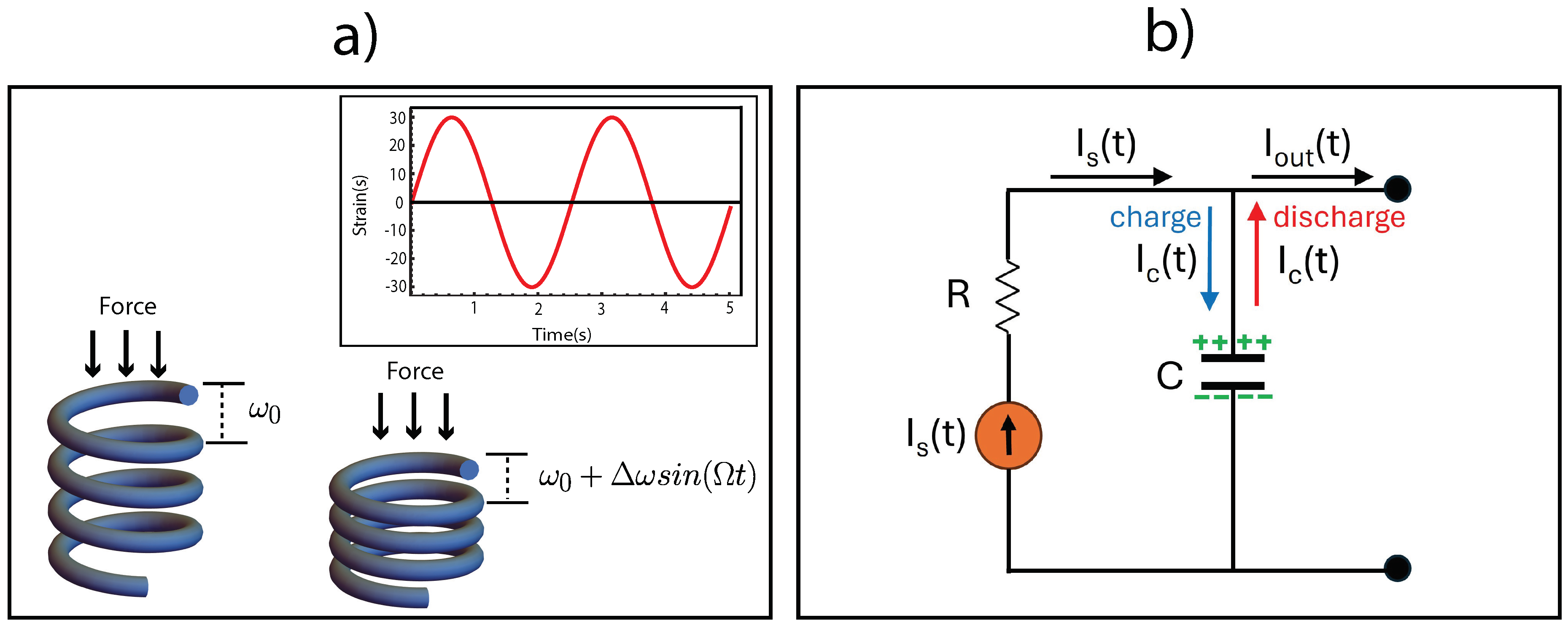

This study investigated the generated current in CNT springs under varying strain through a theoretical approach based on the Dirac equation in curved spacetime. The generated current in our model was calculated by the continuity equation (Equation (

31)). This equation implied the foundation to describe the dynamic of the CNT springs under specific strain, which is equivalent to the circuit model of the system as demonstrated in

Figure 3. This model can be divided into two prominent cases: the first case involves the charging of the capacitor. When the CNT spring is subjected to strain, the time-dependent current source generates an electrical current. This current is divided into two main components: one part corresponds to the term related to the capacitive current, reflecting the mechanism of charge redistribution within the CNT spring and indicating the increase of charge as it responds to the applied strain. This term signifies that part of the current is stored in the capacitance, as illustrated in the equivalent circuit. The other part of the current represents the output current. Thus, the current output is the current flowing out of CNT springs, while the rest is the capacitive current stored within the system as charge in the capacitance as demonstrated in

Figure 3b). In the second case, during discharging, the stored charge in the capacitor is released back into the system, resulting in a decrease in the total charge within the CNT spring. As the strain is applied, the charge redistribution process is reversed, and the current is released from the capacitor. This released current from the capacitor combines with the current from the time-dependent current source to form the total output current that flows out of the system. Furthermore, the time-dependent current source, the relative total charge, and the output current, as shown in

Figure 4,

Figure 5, and

Figure 7c),respectively, exhibit asymmetric behavior. This indicates that the upper and lower portions of the graphs are not symmetric. In particular, the asymmetry observed in the time-dependent current source and time-dependent power output aligns with the experimental findings reported in kim’s experiment [

27], which documented a similar phenomenon in strained CNT springs.

In our numerical calculations, we utilized the parameters

,

, and

derived from the experimental data analysis in Kim’s work [

27]. Based on these parameters; it was able to calculate the curvature parameter within the range of contour 2, as compared to the work of Thiti Thitapura. In this contour, there are three Dirac points, which result in super lattice numbers of

, as illustrated in

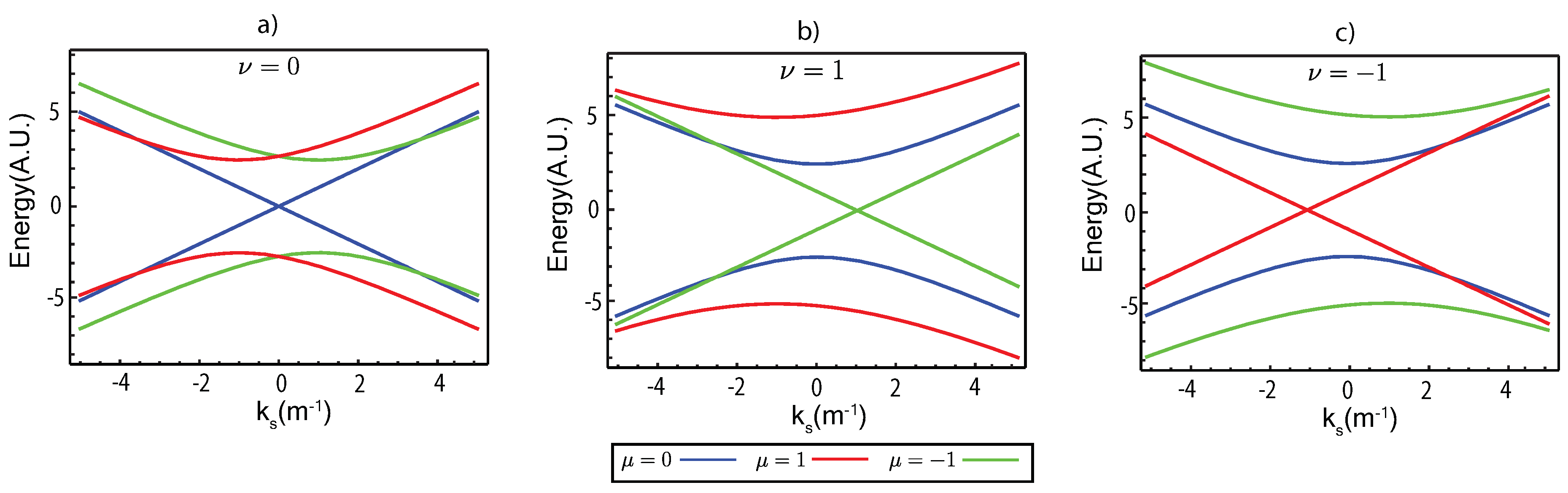

Figure 2. Therefore, the calculation of the instantaneous eigenstate in Equation (

21) is based on the energy-momentum dispersion relation in contour 2, as described in Thiti Thitapura’s research [

35].

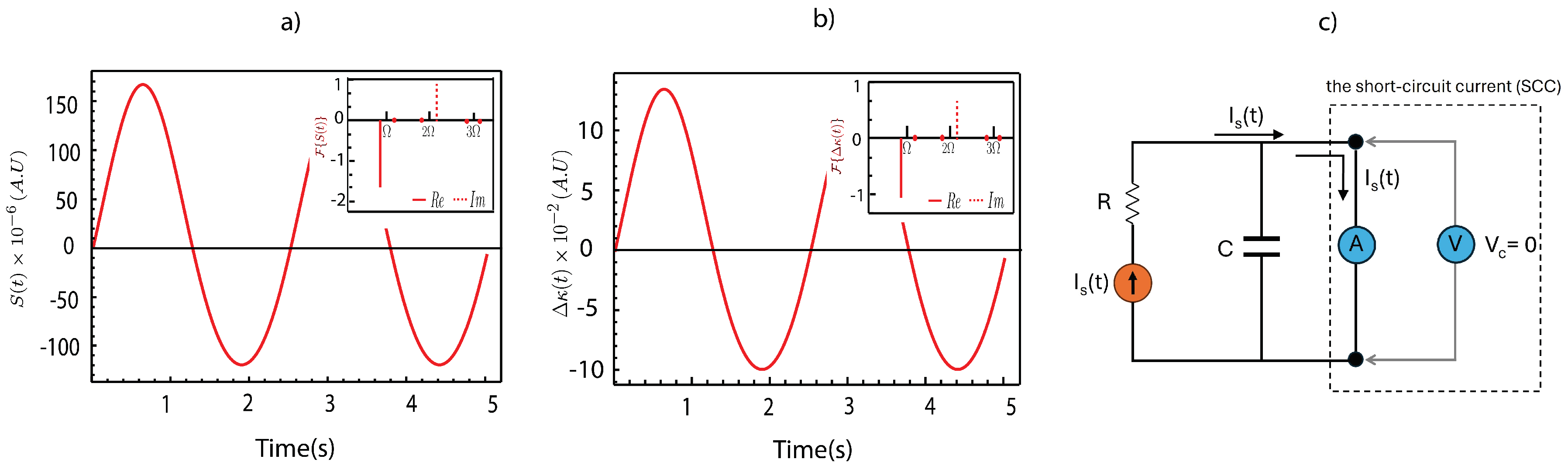

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 illustrate the characteristics of the time-dependent current source and the relative total charge under varying strain conditions. In contrast,

Figure 7a) illustrates the time-dependent power output,

Figure 7b) represents the peak power, and

Figure 7c) depicts the absolute maximum charge. These analyses were performed under a

variation in the parameter

in Equation (

17). The investigation examines the band structure of the CNT spring for different superlattice numbers (

) and quantum azimuthal numbers (

). The results across these cases are compared and analyzed. All the graphs in

Figure 4 to

Figure 7 share a consistent period of 2.5 seconds, matching the period of strain application on the CNT spring, as shown in the inset of

Figure 3a). The phase of the strain graph within the interval 0 to

represents the extension phase of the CNT spring, while the phase between

and

corresponds to the compression phase. This periodic strain cycle aligns with the computational results illustrated in

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. The analysis highlights the electrical responses of the CNT spring under the described strain conditions, emphasizing the role of superlattice and azimuthal configurations in shaping the current, charge characteristics, and the electrical properties, including power output, peak power, and OCV, as demonstrated in

Figure 7. These findings provide valuable insights into the CNT spring’s dynamic behavior and its electronic performance.

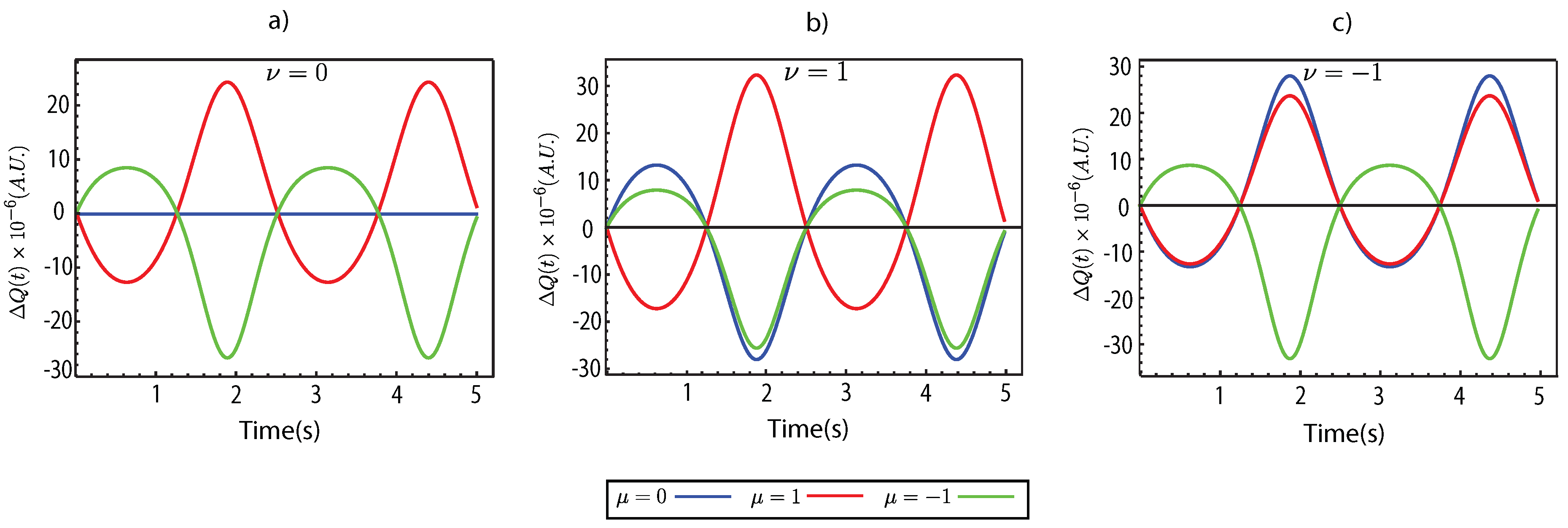

Figure 5.

The results for the relative total charge, with red, blue, and green lines representing the superlattice numbers respectively. a) the relative total charge for . b) the relative total charge for . c) the relative total charge for .

Figure 5.

The results for the relative total charge, with red, blue, and green lines representing the superlattice numbers respectively. a) the relative total charge for . b) the relative total charge for . c) the relative total charge for .

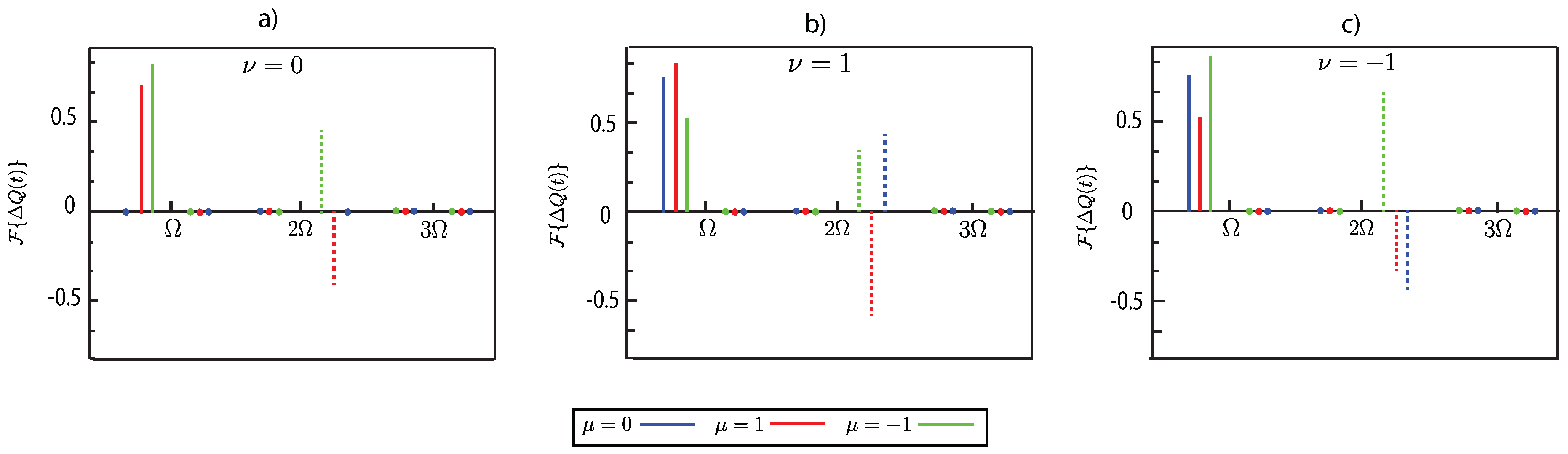

Figure 6.

Fourier coefficients of the relative total charge for different superlattice numbers , represented by red, blue, and green lines, respectively. The solid lines denote the real parts, while the dashed lines represent the imaginary parts of the Fourier coefficients. a) Relative total charge for . b) Relative total charge for . c) Relative total charge for .

Figure 6.

Fourier coefficients of the relative total charge for different superlattice numbers , represented by red, blue, and green lines, respectively. The solid lines denote the real parts, while the dashed lines represent the imaginary parts of the Fourier coefficients. a) Relative total charge for . b) Relative total charge for . c) Relative total charge for .

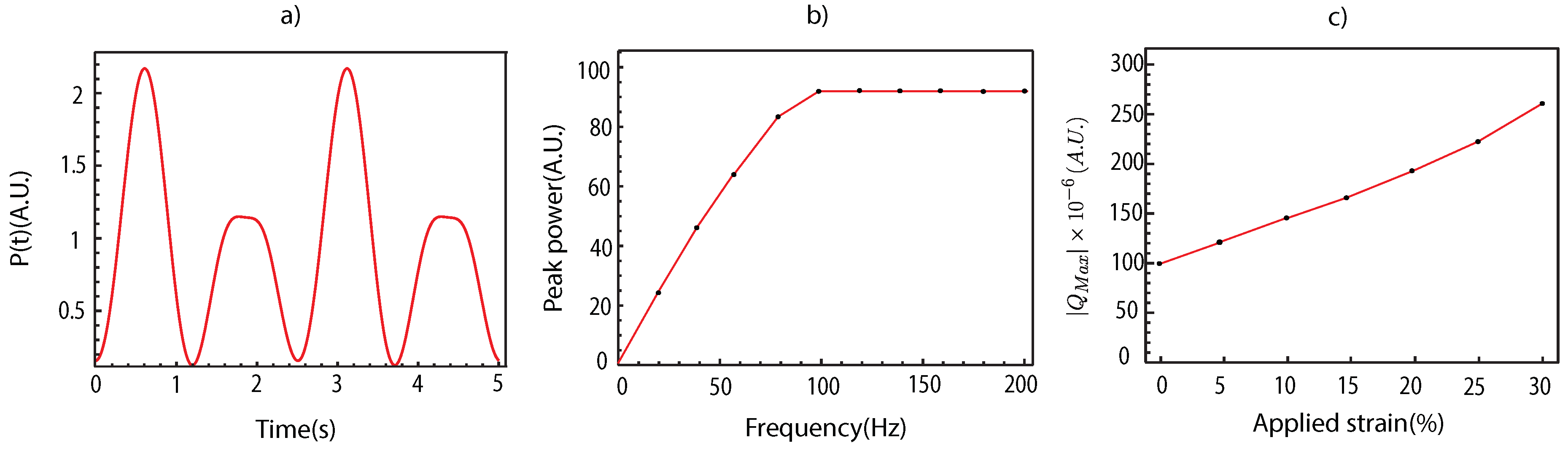

Figure 7.

(a) Time-dependent power output at 0.40 Hz, calculated using Equation (

32). b) Peak power across various frequencies. c) Absolute maximum charge under different applied strains.

Figure 7.

(a) Time-dependent power output at 0.40 Hz, calculated using Equation (

32). b) Peak power across various frequencies. c) Absolute maximum charge under different applied strains.

Based on the calculations of the time-dependent current source in Equation(

30) for each energy band structure, as shown in

Figure 2, we found that the time-dependent current source is identical across all energy band structures except for the band structure with band index

. This band index’s time-dependent current source is absent, meaning the current does not appear. This behavior is illustrated in

Figure 4a). It is attributed to the symmetric nature of the band structure around both positive

and negative

, which results in a cancellation of the time-dependent current source for this particular band. Similar characteristics are observed when comparing the results to

, shown in

Figure 4b). In the phase interval between 0 and

, a peak is evident, corresponding to the stretching phase of the CNT spring, during which the amplitude is larger compared to the phase interval between

and

when the CNT spring is compressed. However, as shown in the inset graph of

Figure 3a), the strain applied to the CNT spring is equivalent during both the stretching (

) and compression (

) phases. This discrepancy arises from the nonlinear dependence of the Lamé coefficient, as described in Equation(

18), on the pitch length of the CNT spring. Consequently, the time-dependent current source and

exhibit different magnitudes during stretching and compression despite the strain being identical. This implies that the vector potential induced by strain is also asymmetric, with a greater magnitude during stretching than compression, even under the same applied strain. Additionally, the Fourier coefficients of the time-dependent current source and

, shown in the inset graphs, reveal the presence of two frequency components:

, which represents the primary frequency, and

, which corresponds to the harmonic or secondary frequency. These components are out of phase by

in imgaginary part. The presence of both primary and harmonic frequencies indicates a complex oscillatory behavior in the system. This dual-frequency composition significantly affects the time-dependent current source and

, leading to non-linear interactions between the stretching and compression phases. As a result, these interactions contribute to the observed asymmetry in the electrical responses. In

Figure 4c), the current flowing out of the equivalent circuit under short-circuit conditions is depicted. Ensure that the total voltage drop across the equivalent circuit is zero, and there is no current flow into or out of the capacitor (

). As a result, the output current from the circuit corresponds directly to the time-dependent current source. Thus, the SCC under these conditions equals the time-dependent current source, as illustrated in

Figure 4c). A similar trend is observed when comparing the calculated SCC to the experimental results reported by Kim [

27]. The SCC lacks symmetry between the

and

phases. Specifically, the SCC amplitude during the

phase is more significant than that during the

phase.

Figure 5 a), b), and c) depict the relative total charge, defined as

When examining the relative total charge at the band index

, as shown in

Figure 5a), no change in total charge is observed. This is consistent with the absence of a current source generated at this band index. For the band index

, a decrease in the relative total charge is observed during the phase interval between 0 and

(corresponding to the stretching phase of the CNT spring). This indicates that during this phase, the capacitor undergoes discharge. Conversely, the relative total charge increases during the phase interval between

and

(the compression phase of the CNT spring), suggesting that the equivalent capacitor recharges during this phase. In contrast, for the band index

, also shown in

Figure 5a), the relative total charge increases during

phase, indicating the charge of the capacitor, while during the

phase, the relative total charge decreases, corresponding to the discharge of the capacitor. The differences in behavior between these two band indices can be analyzed further using the Fourier coefficients depicted in

Figure 6a). At frequency

, the Fourier coefficients of the two band indexs exhibit a phase difference of

. Specifically, for the band index

, the Fourier coefficient at

has a positive value for imaginary parts, consistent with the phase of the relative total charge in this band index. In contrast, for

, the Fourier coefficient at

has a negative value for the imaginary part, which aligns with the phase of the relative total charge in this band index. This phase relationship and Fourier analysis provide a clear understanding of the observed charge dynamics and their correlation with the stretching and compressing of the CNT spring.

The analysis can be applied similarly to other band indices to explain the behavior of the relative total charge and the charging and discharging processes during the stretching or compression phases. In

Figure 5b) and

Figure 5c), this relationship holds consistently across all band indices, where the phases of the relative total charge align with the Fourier coefficients shown in

Figure 6b) and

Figure 6c), respectively. This agreement reinforces the validity of using Fourier-coefficient analysis to interpret the attributes of the relative total charge in the system under various band indexes.

Changes in the relative total charge and associated charging or discharging processes can also be analyzed by considering the changes at the bottom of the energy band structures shown in

Figure 2. For instance, in

Figure 2a), at the band index

, the bottom of the energy band structure is perfectly centered and unshifted. As a result, there is no change in the relative total charge for this band index. In contrast, for the band index

, the bottom of the energy band structure is shifted toward positive

. This causes the overall charge within the CNT spring to increase during the stretching phase (

), while during the compression phase (

), the overall charge within the CNT spring tends to decrease. This behavior is opposite to that observed for the band index

, where the bottom of the energy band structure is shifted toward negative

. In this case, the total charge within the CNT spring decreases during the stretching phase (

) and increases during the compression phase (

); these dynamics are illustrated in

Figure 5a). This analysis of shifts at the bottom of the energy band structure can be extended to explain the changes in the relative total charge observed in

Figure 5b) and

Figure 5c). These changes are consistent with the shifts in the bottom of the energy band structures shown in

Figure 2b) and

Figure 2c).

Figure 7a) illustrates the time-dependent power output at a frequency of 0.4 Hz. The time-dependent power output is measured by connecting the load in an equivalent circuit with an external resistance, as calculated using Equation (

33). This time-dependent power output represents the combined contribution of all band indices. According to Equation(

33), the time-dependent power output is directly proportional to

. At

, when the load is connected, a

current flows out of the circuit, resulting in an initial time-dependent power output of approximately 0.05. This initial value arises from the induced pseudo-vector potential in the CNT spring structure, as described in the work of Thiti [

35]. The calculations reveal that during the extension phase of the CNT spring (

), the amplitude of the time-dependent power output is higher compared to the compression phase (

), illustrating the asymmetric electrical response under these strain conditions.This asymmetry in the time-dependent power output is attributed to the unequal response of

to the applied strain during the extension and compression phases. Specifically,

exhibits a higher amplitude during the extension phase than during compression. This difference causes the time-dependent power output to have a higher amplitude during extension compared to compression. These calculated results align with the experimental findings reported by Kim [

27], highlighting similar asymmetric electrical responses of power output in strained CNT springs.

Figure 7b) shows the peak power values at different frequencies. Peak power is defined as the maximum value of the time-dependent power output within one cycle, where one cycle corresponds to one complete extension and compression of the CNT spring. The calculated peak power values represent the contributions from all band indices. The results indicate that peak power increases with frequency, reaching a maximum value of approximately 92 at a frequency of around 100 Hz. Beyond this frequency, the peak power remains constant and does not increase further. This behavior is consistent with the experimental observations reported in Kim’s study.

Figure 7c) presents the absolute maximum charge at different levels of applied strain. The absolute maximum charge is calculated as the maximum charge contribution across all band indices. Moreover, the absolute maximum charge is directly proportional to

, and from the equivalent circuit, it can be observed that the total voltage drop across the circuit is equal to

. Therefore, the results of the absolute maximum charge can effectively describe the behavior of the OCV. Specifically, the results indicate that as the applied strain increases, the absolute maximum charge also increases proportionally. Thus, our calculations imply that the OCV will increase with the applied strain, which is consistent with the experimental measurements of OCV reported in Kim’s work [

27], where a similar trend was observed.

4. Conclusions

This study establishes a comprehensive theoretical framework to elucidate the curvature-induced electrical properties of two-dimensional electron gas confined on carbon nanotube CNT springs. By employing the Dirac equation in curved spacetime, we demonstrated how geometric deformation profoundly influences electronic behavior, revealing the interplay between mechanical strain and electronic responses. These results validate and extend experimental observations, offering key insights into the mechanisms of strain-induced current generation in CNT-based systems.

Key findings highlight asymmetric time-dependent current behavior during the stretching and compression cycles of CNT springs, driven by curvature-dependent variations in the Lamé coefficient and induced vector potentials. Non-linear changes in these parameters lead to distinct magnitudes of time-dependent current and charge redistribution, with more pronounced effects during stretching than compression. These findings align closely with experimental data, where electrical responses display clear asymmetry over a full mechanical cycle, reinforcing the validity of our theoretical model.

Fourier analysis identifies two key frequencies: the primary and harmonic , phase-shifted by in imaginary part. These frequencies, derived from the Fourier coefficients of the time-dependent current source and , highlight the system’s complex oscillatory behavior. Their interplay drives non-linear interactions between stretching and compression phases, contributing to asymmetries in electrical responses such as power output and charge redistribution. These findings deepen our understanding of how strain modulates curvature and electronic dynamics, providing a strong theoretical basis consistent with experimental observations.

Charge redistribution patterns were found to depend on energy band indices, with specific band structures exhibiting contrasting charging and discharging behaviors during stretching and compression. Shifts in the energy band structure’s bottom significantly influenced charge redistribution, linking quantum-level properties to macroscopic strain effects. These results deepen our understanding of how curvature and strain govern electronic dynamics in CNT springs. Additionally, the curvature-induced vector potential generates higher power output during stretching compared to compression, attributed to greater variations in the curvature parameter. Peak power output was observed at , with performance stabilizing beyond this frequency, highlighting an optimal range for energy harvesting. Strain analysis confirmed a proportional relationship between applied strain and maximum charge storage, consistent with OCV trends observed in experiments.

Together, these findings bridge experimental observations and theoretical modeling, showcasing The results of this study demonstrate that CNT springs can be effectively applied as energy harvesters and sensors in wearable electronics, smart textiles, and biofluid sensing. By laying a solid foundation for understanding their dynamic behavior under strain, this study opens pathways for further optimization of CNT-based devices, focusing on enhanced performance and broader applicability. Future research may extend this framework to explore external field effects, multi-band interactions, and advanced material designs for next-generation electromechanical systems.