Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

15 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Pharmacological Treatments

2.3. Cell Viability Assay

2.4. Morphological analysis

2.5. Total RNA Extraction and RT-PCR Analysis

2.6. Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

2.7. ROS Detection Assay

2.8. Lipid Droplets Detection Assay

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

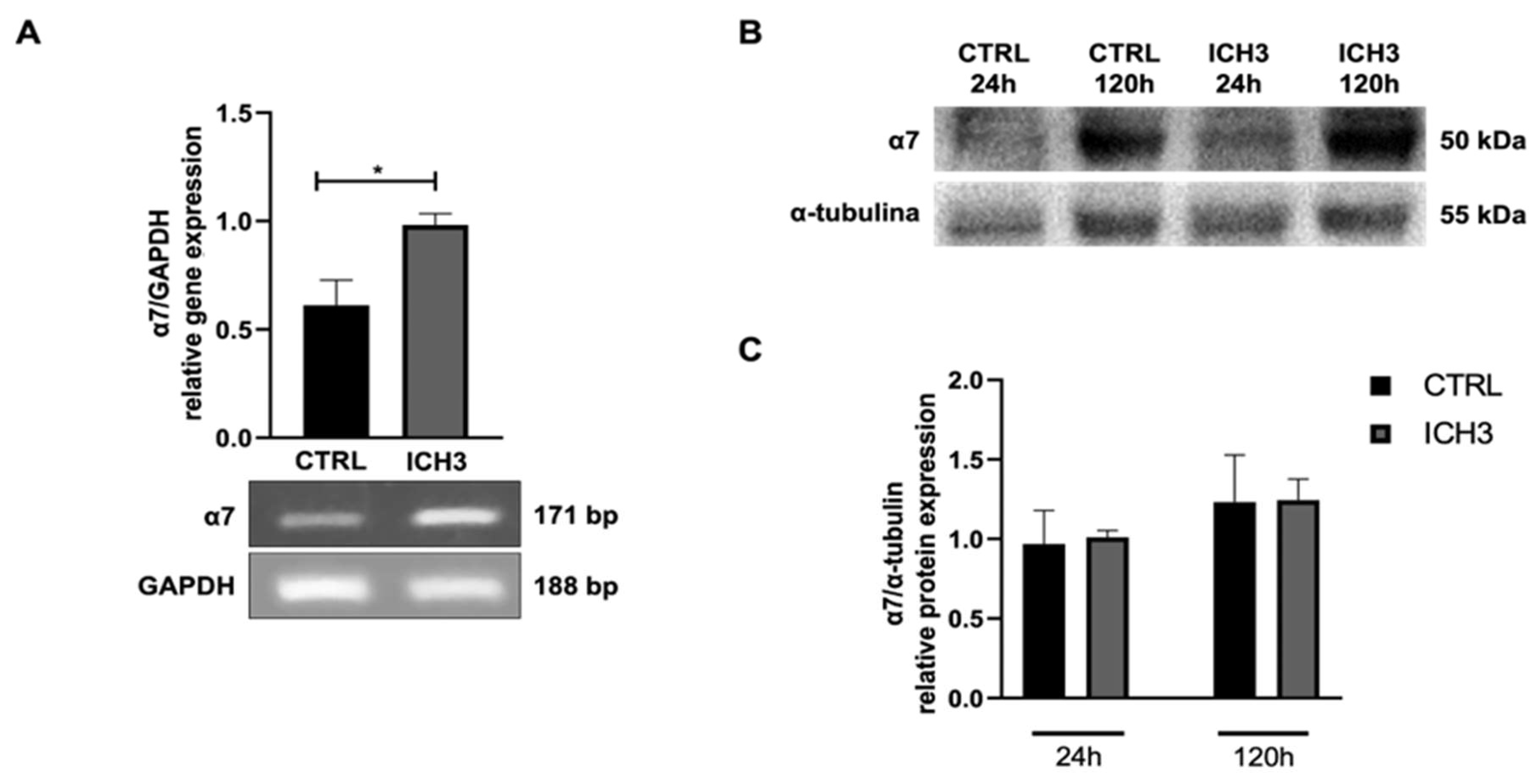

3.1. Analysis of α7 nAChR Expression

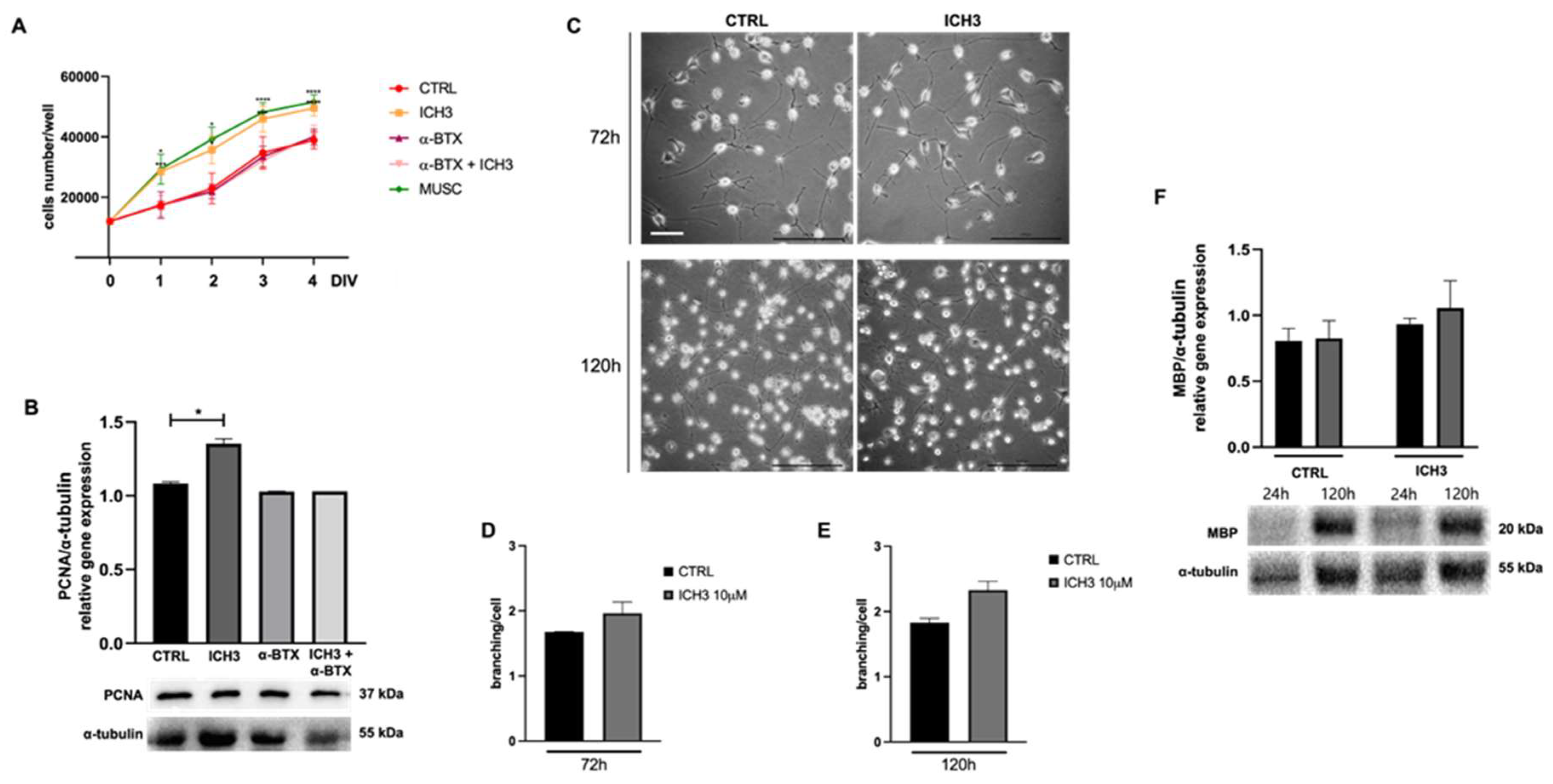

3.2. Analysis of Cell Proliferation and Morphology

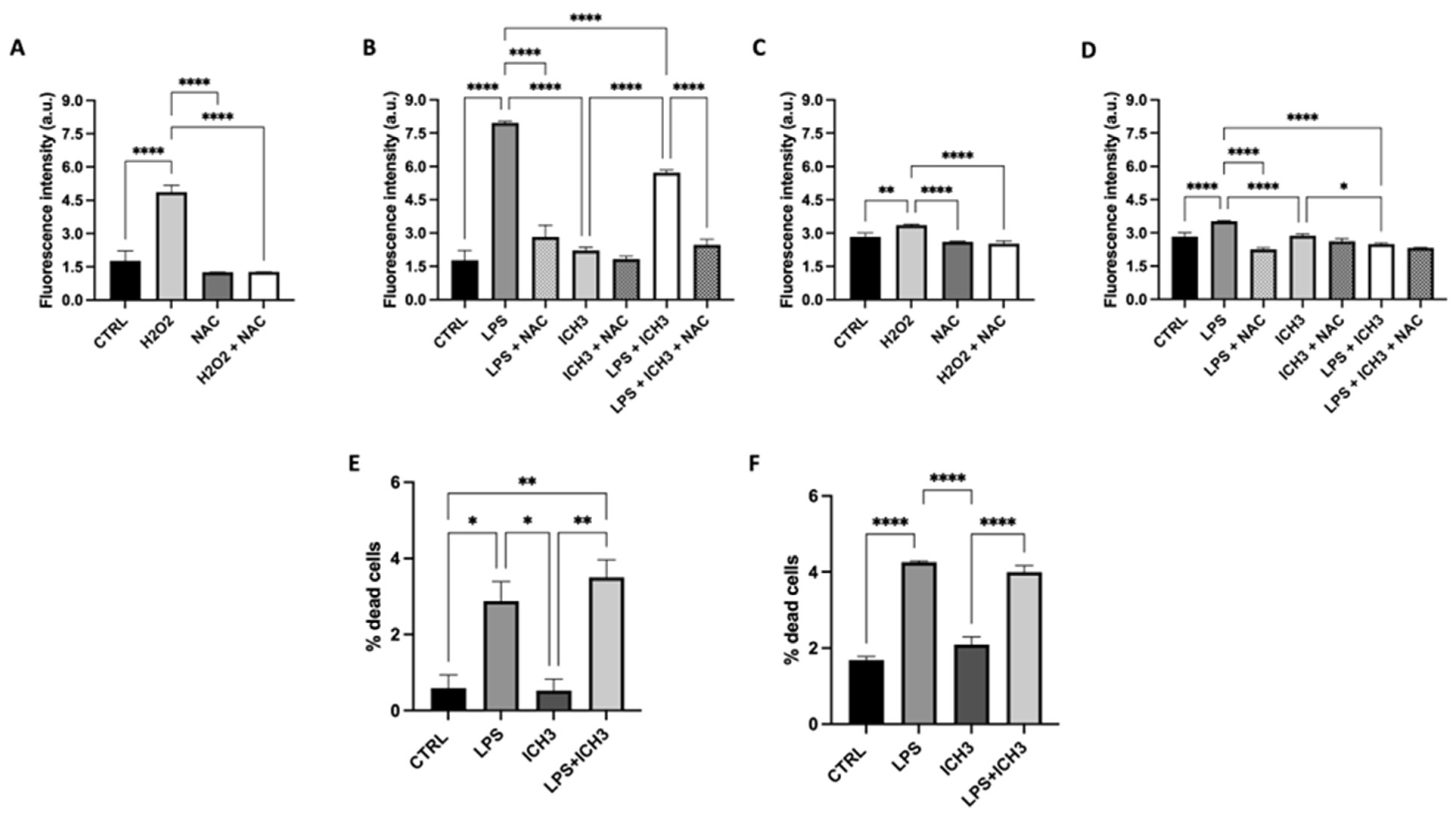

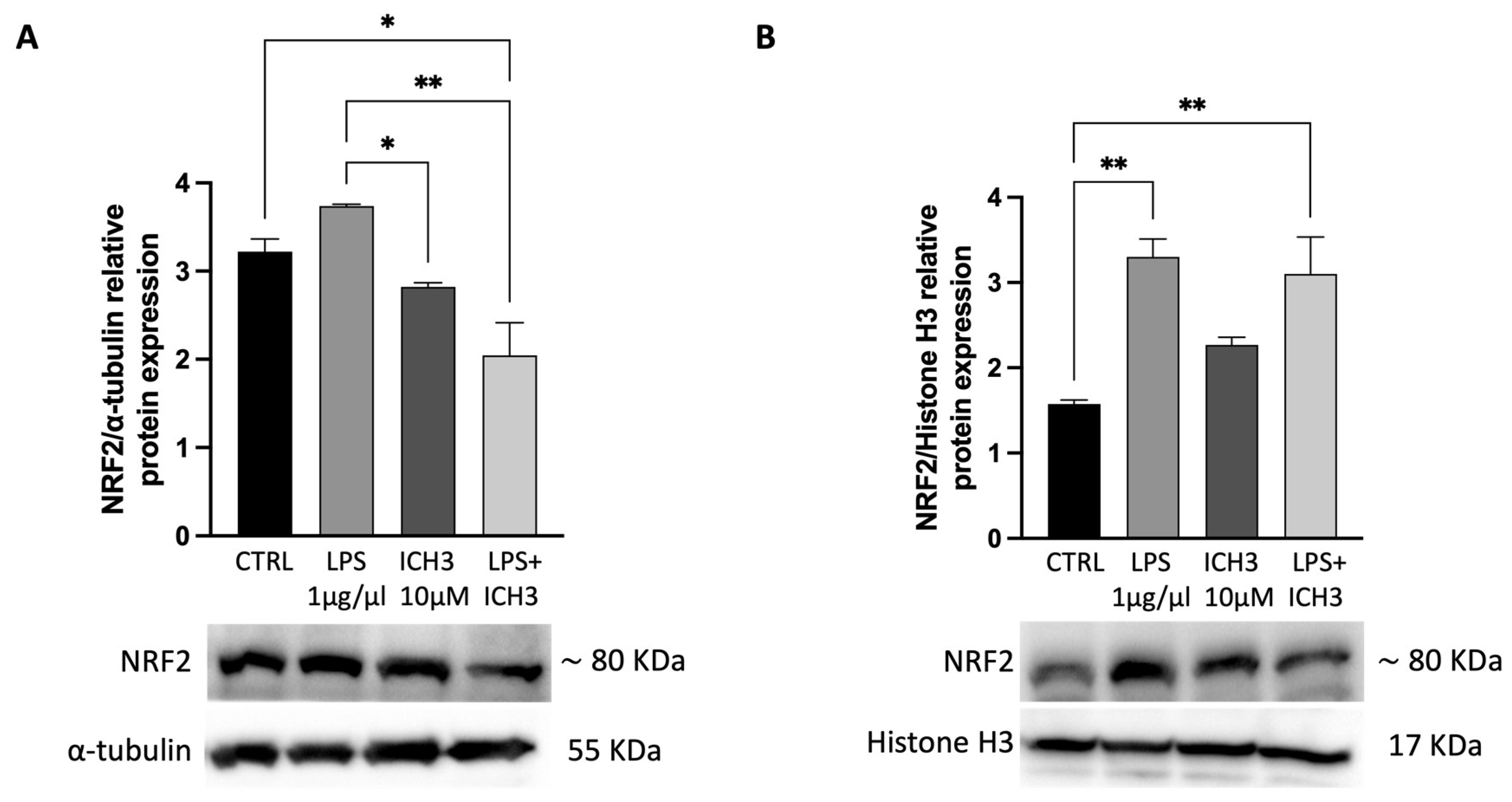

3.3. Analysis of the Antioxidant Properties Mediated by α7 nAChR Activation

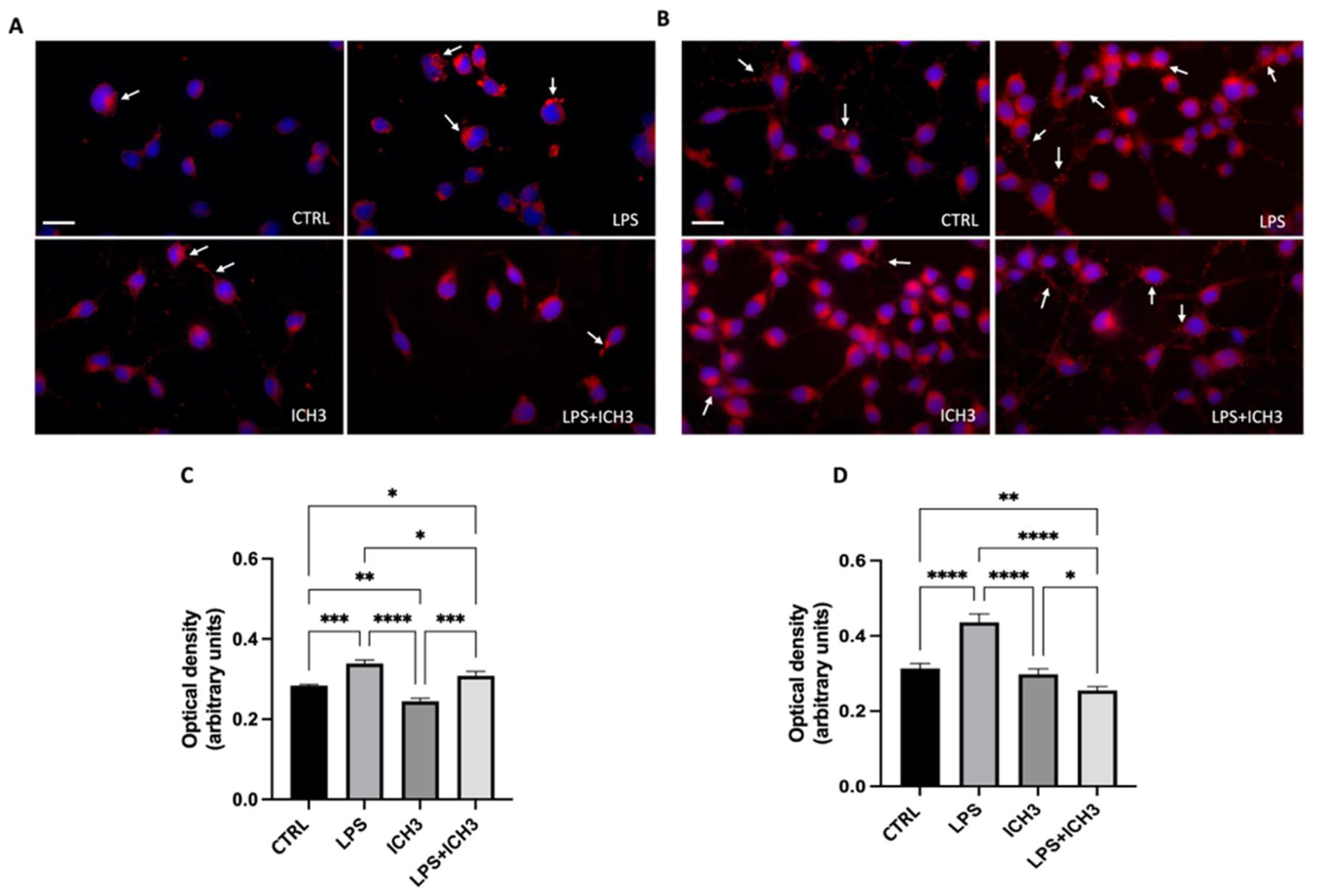

3.4. Analysis of ICH3 Effects on Lipid Content in Oli Neu Cells

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Piovesana, R.; Salazar Intriago, M.S.; Dini, L.; Tata, A.M. Cholinergic Modulation of Neuroinflammation: Focus on A7 Nicotinic Receptor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Joh, T.H. Microglia, Major Player in the Brain Inflammation: Their Roles in the Pathogenesis of Parkinson’s Disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 2006, 38, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, P.M.; Martins, L.A.M.; Souza, D.O.; Quincozes-Santos, A. Glioprotective Effect of Resveratrol: An Emerging Therapeutic Role for Oligodendroglial Cells. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 2967–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, Y.; Yonezawa, A.; Kume, T.; Katsuki, H.; Kaneko, S.; Sugimoto, H.; Akaike, A. Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor-Mediated Neuroprotection by Donepezil Against Glutamate Neurotoxicity in Rat Cortical Neurons. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 306, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egea, J.; Buendia, I.; Parada, E.; Navarro, E.; León, R.; Lopez, M.G. Anti-Inflammatory Role of Microglial Alpha7 nAChRs and Its Role in Neuroprotection. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2015, 97, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shytle, R.D.; Mori, T.; Townsend, K.; Vendrame, M.; Sun, N.; Zeng, J.; Ehrhart, J.; Silver, A.A.; Sanberg, P.R.; Tan, J. Cholinergic Modulation of Microglial Activation by A7 Nicotinic Receptors. J. Neurochem. 2004, 89, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuen, T.J.; Silbereis, J.C.; Griveau, A.; Chang, S.M.; Daneman, R.; Fancy, S.P.J.; Zahed, H.; Maltepe, E.; Rowitch, D.H. Oligodendrocyte-Encoded HIF Function Couples Postnatal Myelination and White Matter Angiogenesis. Cell 2014, 158, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, W.J.; Van Der Zanden, E.P.; The, F.O.; Bijlsma, M.F.; Van Westerloo, D.J.; Bennink, R.J.; Berthoud, H.-R.; Uematsu, S.; Akira, S.; Van Den Wijngaard, R.M.; et al. Stimulation of the Vagus Nerve Attenuates Macrophage Activation by Activating the Jak2-STAT3 Signaling Pathway. Nat. Immunol. 2005, 6, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Álvarez, M.; Moreno-Ortega, A.J.; Navarro, E.; Fernández-Morales, J.C.; Egea, J.; López, M.G.; Cano-Abad, M.F. Positive Allosteric Modulation of Alpha-7 Nicotinic Receptors Promotes Cell Death by Inducing Ca 2+ Release from the Endoplasmic Reticulum. J. Neurochem. 2015, 133, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracey, K.J. The Inflammatory Reflex. Nature 2002, 420, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, R.; Ajmone-Cat, M.; Carnevale, D.; Minghetti, L. Activation of A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor by Nicotine Selectively Up-Regulates Cyclooxygenase-2 and Prostaglandin E2 in Rat Microglial Cultures. J. Neuroinflammation 2005, 2, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallanoce, C.; Magrone, P.; Matera, C.; Frigerio, F.; Grazioso, G.; De Amici, M.; Fucile, S.; Piccari, V.; Frydenvang, K.; Pucci, L.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Pharmacological Characterization of Novel Spirocyclic Quinuclidinyl-Δ 2 -Isoxazoline Derivatives as Potent and Selective Agonists of A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. ChemMedChem 2011, 6, 889–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cesare Mannelli, L.; Pacini, A.; Matera, C.; Zanardelli, M.; Mello, T.; De Amici, M.; Dallanoce, C.; Ghelardini, C. Involvement of A7 nAChR Subtype in Rat Oxaliplatin-Induced Neuropathy: Effects of Selective Activation. Neuropharmacology 2014, 79, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scabia, G.; Cancello, R.; Dallanoce, C.; Berger, S.; Matera, C.; Dattilo, A.; Zulian, A.; Barone, I.; Ceccarini, G.; Santini, F.; et al. ICH3, a Selective Alpha7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Agonist, Modulates Adipocyte Inflammation Associated with Obesity. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2020, 43, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernarella, M.; Piovesana, R.; Matera, C.; Faroni, A.; Fiore, M.; Dini, L.; Reid, A.J.; Dallanoce, C.; Tata, A.M. Effects Mediated by the A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor on Cell Proliferation and Migration in Rat Adipose-Derived Stem Cells. Eur. J. Histochem. 2020, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar Intriago, M.S.; Piovesana, R.; Matera, A.; Taggi, M.; Canipari, R.; Fabrizi, C.; Papotto, C.; Matera, C.; De Amici, M.; Dallanoce, C.; et al. The Mechanisms Mediated by A7 Acetylcholine Nicotinic Receptors May Contribute to Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Molecules 2021, 26, 7668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botticelli, E.; Guerriero, C.; Fucile, S.; De Stefano, M.E.; Matera, C.; Dallanoce, C.; De Amici, M.; Tata, A.M. A7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors May Improve Schwann Cell Regenerating Potential via Metabotropic Signaling Pathways. Cells 2023, 12, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.; Krämer, E.; Grzenkowski, M.; Tang, K.; Blakemore, W.; Aguzzi, A.; Khazaie, K.; Chlichlia, K.; Von Blankenfeld, G.; Kettenmann, H.; et al. Lines of Murine Oligodendroglial Precursor Cells Immortalized by an Activated Neu Tyrosine Kinase Show Distinct Degrees of Interaction with Axons In Vitro and In Vivo. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1995, 7, 1245–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trotter, J.; Schachner, M. Cells Positive for the O4 Surface Antigen Isolated by Cell Sorting Are Able to Differentiate into Astrocytes or Oligodendrocytes. Dev. Brain Res. 1989, 46, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.T.; Hawrot, E.; Lentz, T.L. Distribution of Alpha-Bungarotoxin Binding Sites over Residues 173-204 of the Alpha Subunit of the Acetylcholine Receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1988, 34, 643–650. [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Cellular Growth and Survival: Application to Proliferation and Cytotoxicity Assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sylvester, P.W. Optimization of the Tetrazolium Dye (MTT) Colorimetric Assay for Cellular Growth and Viability. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ 2011, 716, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, F.; Bernardo, A.; Magnaghi, V.; Minghetti, L.; Tata, A.M. Muscarinic Receptor Subtypes as Potential Targets to Modulate Oligodendrocyte Progenitor Survival, Proliferation, and Differentiation. Dev. Neurobiol. 2012, 72, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deneris, E.S.; Connolly, J.; Rogers, S.W.; Duvoisin, R. Pharmacological and Functional Diversity of Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1991, 12, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehm, E.M.; Gildenberg, M.S.; Washington, M.T. The Many Roles of PCNA in Eukaryotic DNA Replication. In The Enzymes; Elsevier, 2016; Vol. 39, pp. 231–254 ISBN 978-0-12-804735-4.

- Guerriero, C.; Puliatti, G.; Di Marino, T.; Tata, A.M. Effects Mediated by Dimethyl Fumarate on In Vitro Oligodendrocytes: Implications in Multiple Sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlgren, S.C.; Wallace, H.; Bishop, J.; Neophytou, C.; Raff, M.C. Effects of Thyroid Hormone on Embryonic Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cell Developmentin Vivoandin Vitro. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 1997, 9, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.A.; Khan, M.; Jo, M.; Jo, M.G.; Amin, F.U.; Kim, M.O. Melatonin Stimulates the SIRT 1/Nrf2 Signaling Pathway Counteracting Lipopolysaccharide ( LPS )-Induced Oxidative Stress to Rescue Postnatal Rat Brain. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2017, 23, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahremany, S.; Babaev, I.; Gvirtz, R.; Ogen-Stern, N.; Azoulay-Ginsburg, S.; Senderowitz, H.; Cohen, G.; Gruzman, A. Nrf2 Activation by SK-119 Attenuates Oxidative Stress, UVB, and LPS-Induced Damage. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2019, 32, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Du, X.; He, B. Lipopolysaccharide Upregulates the Expression of CINC-3 and LIX in Primary NG2 Cells. Neurochem. Res. 2016, 41, 1448–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, J.F.; Evans, J.W.; Limoli, C.L.; Calabro-Jones, P.M. Radiation and Hydrogen Peroxide Induced Free Radical Damage to DNA. Br. J. Cancer. Suppl. 1987, 8, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, W.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Liu, Q.; Sha, H. The Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Oxidant Mechanisms of the Keap1/Nrf2/ARE Signaling Pathway in Chronic Diseases. Aging Dis. 2019, 10, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, A.; Kang, M.-I.; Okawa, H.; Ohtsuji, M.; Zenke, Y.; Chiba, T.; Igarashi, K.; Yamamoto, M. Oxidative Stress Sensor Keap1 Functions as an Adaptor for Cul3-Based E3 Ligase To Regulate Proteasomal Degradation of Nrf2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 7130–7139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, T.; Suzuki, T.; Kobayashi, A.; Wakabayashi, J.; Maher, J.; Motohashi, H.; Yamamoto, M. Physiological Significance of Reactive Cysteine Residues of Keap1 in Determining Nrf2 Activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 28, 2758–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarc, E.; Petan, T. A Twist of FATe: Lipid Droplets and Inflammatory Lipid Mediators. Biochimie 2020, 169, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, R.D.; Dutta, D.J.; Belgrad, J.; Robnett, M. Cholinergic Signaling in Myelination. Glia 2017, 65, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatta, V.; Mengod, G.; Reale, M.; Tata, A.M. Possible Correlation between Cholinergic System Alterations and Neuro/Inflammation in Multiple Sclerosis. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ralhan, I.; Chang, C.-L.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Ioannou, M.S. Lipid Droplets in the Nervous System. J. Cell Biol. 2021, 220, e202102136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).