1. Introduction

As glial cells in the peripheral nervous system (PNS), Schwann cells (SCs) provide trophic support for neuronal growth and maintenance and ensheath their axons in either a myelinating or an unmyelinating form. Following axonal injury, SCs proliferate, migrate, collaborate with macrophages to clear axon debris, promote the elongation of new axons, and ultimately remyelinate them [

1]. Abnormalities in SCs and/or their crosstalk with neurons can lead to demyelinating neuropathy or myelinopathy and have also been implicated in neuronopathy and axonopathy [

2,

3].

Co-culture systems of neurons and SCs have been widely used to investigate their interactions and the molecular and signaling pathways involved in myelination and demyelination [

4,

5,

6,

7]. In most previous studies, both neurons and SCs were obtained via primary culture, a time-consuming process requiring extensive preparation to achieve high purity before each co-culture experiment. To improve research efficiency, it would be desirable to establish co-culture systems using cell lines for both neurons and SCs. However, their high proliferative activity and phenotypic differences from primary cultured cells pose significant challenges for achieving stable neuron-SC interactions. Some established SC lines have demonstrated the ability to myelinate neurites in co-culture with primary cultured dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons [

8,

9]. Additionally, a myelinating co-culture system using human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cell-derived neurons and neonatal rat SCs has been developed [

10]. However, little attention has been given to achieving myelination in co-cultures composed solely of pure neuronal and SC lines.

We previously established a spontaneously immortalized SC line, IFRS1, from long-term primary cultures of adult Fischer344 rat DRG and peripheral nerves [

11]. Because glial growth stimulants such as forskolin and neuregulin-1β (

aka heregulin-β) are required for IFRS1 cell passage, their proliferative activity can be suppressed by omitting these factors from the culture medium. IFRS1 cells retain the intrinsic ability to myelinate neurites in co-culture with primary cultured adult rat DRG neurons [

11], nerve growth factor (NGF)-primed PC12 cells [

12], mouse embryonic stem (ES) cell line-derived motor neurons [

13], and the mouse neuroblastoma/mouse motor neuron hybrid NSC-34 cells line [

14,

15]. In the case of PC12 cells, maintaining a low seeding density (2-3 × 10

2 cells/cm

2) and using a serum-free medium with minimum nutrients and a high concentration (50 ng/mL) of NGF effectively prevented overgrowth and promoted neuronal differentiation. However, this approach was not applicable to NSC-34 cells, which do not survive under low-density, serum-free conditions. To address this, NSC-34 cells were seeded at a higher density (2 × 10

3 cells/cm

2) and cultured in serum-containing medium supplemented with non-essential amino acids (NEAA) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [

16,

17]. While these conditions supported cell viability and promote neurite outgrowth, NSC-34 cells inevitably overgrew when directly co-cultured with IFRS1 cells. To overcome this issue, we pre-treated NSC-34 cells with the anti-mitotic agent mitomycin C (MMC; 1 μg/mL) for 12-16 h [

18] prior to co-culture. This treatment effectively prevented excessive proliferation without inducing cell death. In addition to these models, we established a myelinating co-culture system using IFRS1 cells and the mouse neuroblastoma/rat embryonic DRG neuron hybrid ND7/23 cell line [

19,

20]. The co-culture procedure for ND7/23−IFRS1 is similar to that used for NSC-34−IFRS1, involving the same seeding density, serum-containing medium with NEAA, and MMC pre-treatment of neurons prior to co-culture with IFRS1 cells. However, several distinct differences exist between the two systems, reflecting the biological characteristics of ND7/23 and NSC-34 cells as sensory and motor neuron-like cells, respectively.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Culture of ND7/23 and IFRS1 Cells

ND7/23 cells were kindly provided by Prof. Atsufumi Kawabata and Dr. Fumiko Sekiguchi of Kindai University, Osaka, Japan. The cells were seeded in 100-mm plastic dishes (Greiner Bio-One GmbH, Frickenhausen, Germany) at an approximate density of 1 × 104 cells/cm2 and maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher) and Antibiotic-Antimycotic solution (100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 250 ng/mL amphotericin B; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA).

IFRS1 cells were established from long-term primary culture of adult Fischer344 rat SCs in our laboratory [

11]. The cells were seeded in 100-mm plastic dishes at an approximate density of 2 × 10

4 cells/cm

2 and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS, 20 ng/mL recombinant human heregulin-β (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), 5 μM forskolin (Sigma) and Antibiotic-Antimycotic solution.

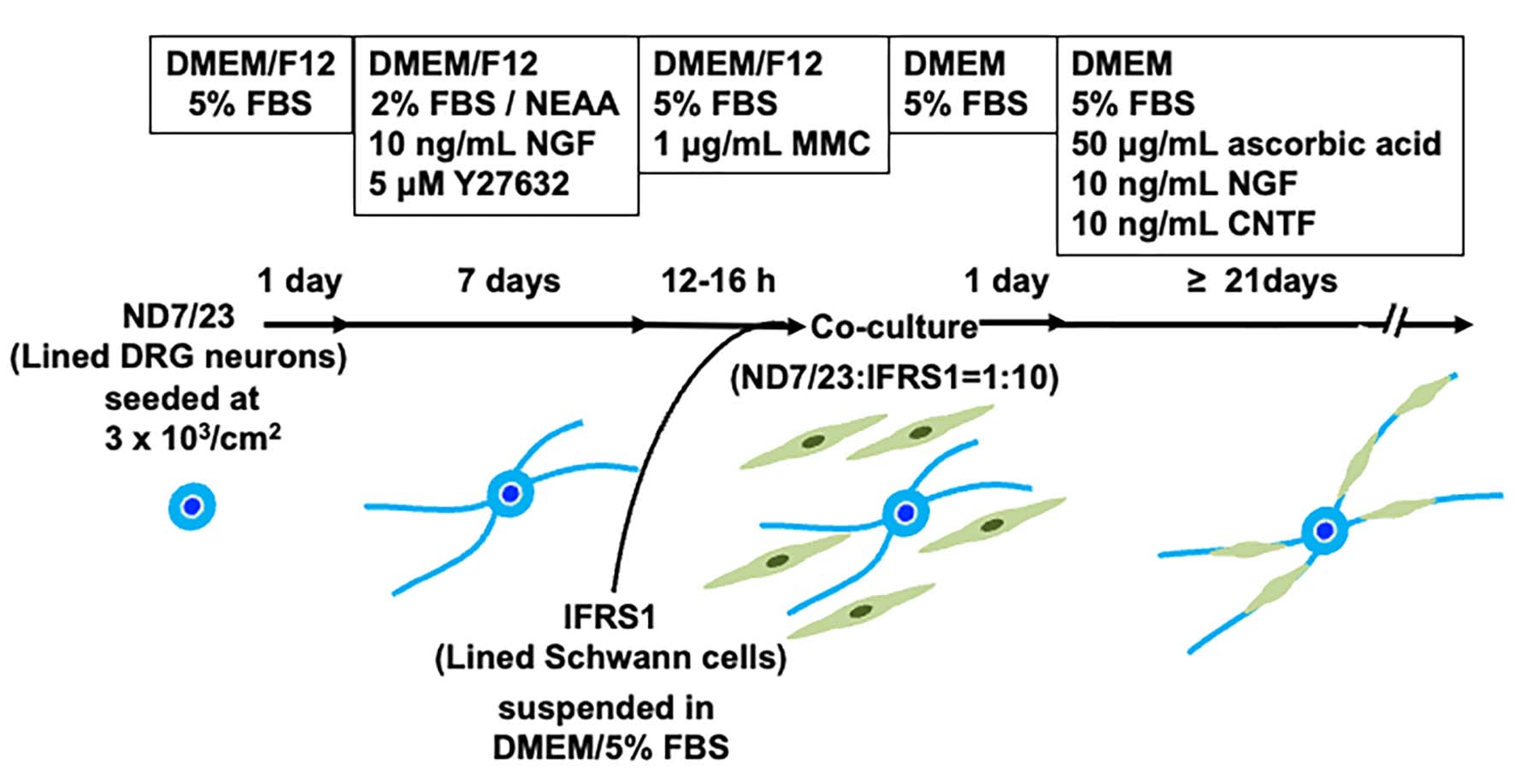

2.2. Co-Culture of ND7/23 and IFRS1 Cells

At semi-confluency, ND7/23 cells were detached using Cell Dissociation Buffer (Thermo Fisher), suspended in DMEM/Ham’s F12 (Thermo Fisher) containing 5% FBS in a 50-mL polypropylene conical tube (Greiner Bio-One GmbH), and reseeded onto poly-L-lysine (10 μg/mL; Sigma)-coated Aclar fluorocarbon coverslips (9 mm diameter; Nissin EM Co., Tokyo, Japan), type I collagen-coated 12-well culture plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA), and type I collagen-coated 2-well glass chamber slides (Matsunami Glass Ind., LTD, Osaka, Japan) at a density of approximately 3 × 10

3 cells/cm

2. Cells were maintained in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 2% FBS, 1% NEAA (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) [

21], 10 ng/mL recombinant rat NGF (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), and 5 μM Y-27632, a selective Rho-associated coiled coil-forming kinase (ROCK) inhibitor (FUJIFILM Wako) [

22], for 5-7 days. When neurite elongation was observed in most ND7/23 cells under phase-contrast microscopy, the cells were incubated for 12-16 h with DMEM/F12 containing 5% FBS and 1 μg/mL mitomycin C (MMC; Nacalai Tesque Inc., Kyoto, Japan) [

15]. After rinsing twice with DMEM/5% FBS, the cells were co-cultured with IFRS1 cells, which had been detached using 0.05% trypsin/0.53 mM EDTA solution (Nacalai Tesque) and suspended in DMEM containing 5% FBS at approximately 1 x 10

5 cells/mL. The ND7/23:IFRS1 cell ratio was adjusted to approximately 1:10. The co-cultures were fed twice weekly with DMEM containing 5% FBS, 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid (Wako), 10 ng/mL NGF, and 10 ng/mL recombinant rat ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF; Peprotech), and maintained for longer than 21 days (

Figure 1).

2.3. Immunofluorescence

Co-cultured cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at 4°C and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies diluted in 20 mM PBS containing 0.4% Block Ace (DS Pharma Biomedical Co., Osaka, Japan).

- 1)

Rabbit anti-myelin basic protein (MBP) polyclonal antibody (1:1,000; Merk (formerly Chemicon), Temecula, CA, USA) [

11], and mouse anti-βIII tubulin monoclonal antibody (1:1,000; Sigma) [

23]

- 2)

Rabbit anti-peripheral myelin protein 22 (PMP22) polyclonal antibody (1:1,000, Sigma) [

24], and mouse anti-βIII tubulin monoclonal antibody.

After washing with PBS, cells were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with Alexa Fluor 594 or 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and/or anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:200, Thermo Fisher), followed by nuclear staining with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 300 nM; Thermo Fisher) for 5 min at room temperature. Immunocytochemical controls lacking primary antibodies showed no positive staining (data not shown). Details of antibody validation (Western blotting, pre-absorption tests, etc.) are provided in the cited references.

2.4. Sudan Black B Staining

Co-cultured cells on 2-well chamber slides were fixed overnight at 4°C with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). After post-fixation with 0.1% osmium tetroxide (FUJIFILM Wako) for 1 h at room temperature and dehydration with 70% ethanol, the cells were stained with 0.5% Sudan Black B (FUJIFILM Wako) in 70% ethanol for 1 h at room temperature, rehydrated, and mounted in glycerol gelatin (Sigma) [

12].

2.5. Image Presentation

Phase-contrast images were acquired using a microscope digital camera system (DP22-CU; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with image analysis software (WinROOF2015; Mitani Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Cytochemically processed culture samples were observed and imaged using a TCS SP5 confocal microscope system (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

2.6. Electron Microscopy

Co-cultures in Aclar dishes and 2-well chamber slides were fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer for 20 min at room temperature. After washing, cells were postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide in buffer for 30 min at room temperature, rinsed, dehydrated through graded ethanol, and embedded in epoxy resin. Coverslip portions were removed and re-embedded to allow cross-sectioning of co-cultures [

12]. Semi-thin sections (1 μm) were examined using a light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and suitable areas were selected for ultrathin sectioning. Ultrathin sections were double stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined using an electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

3. Results

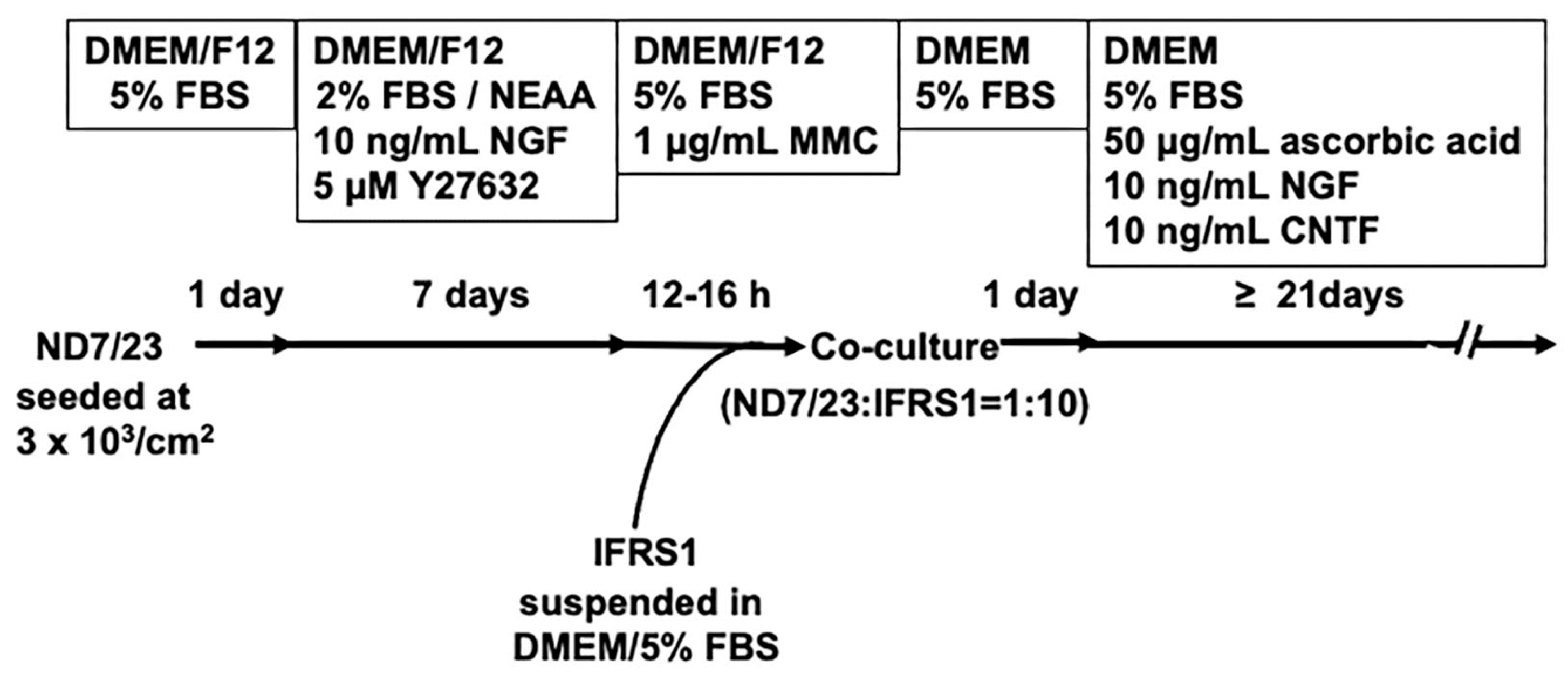

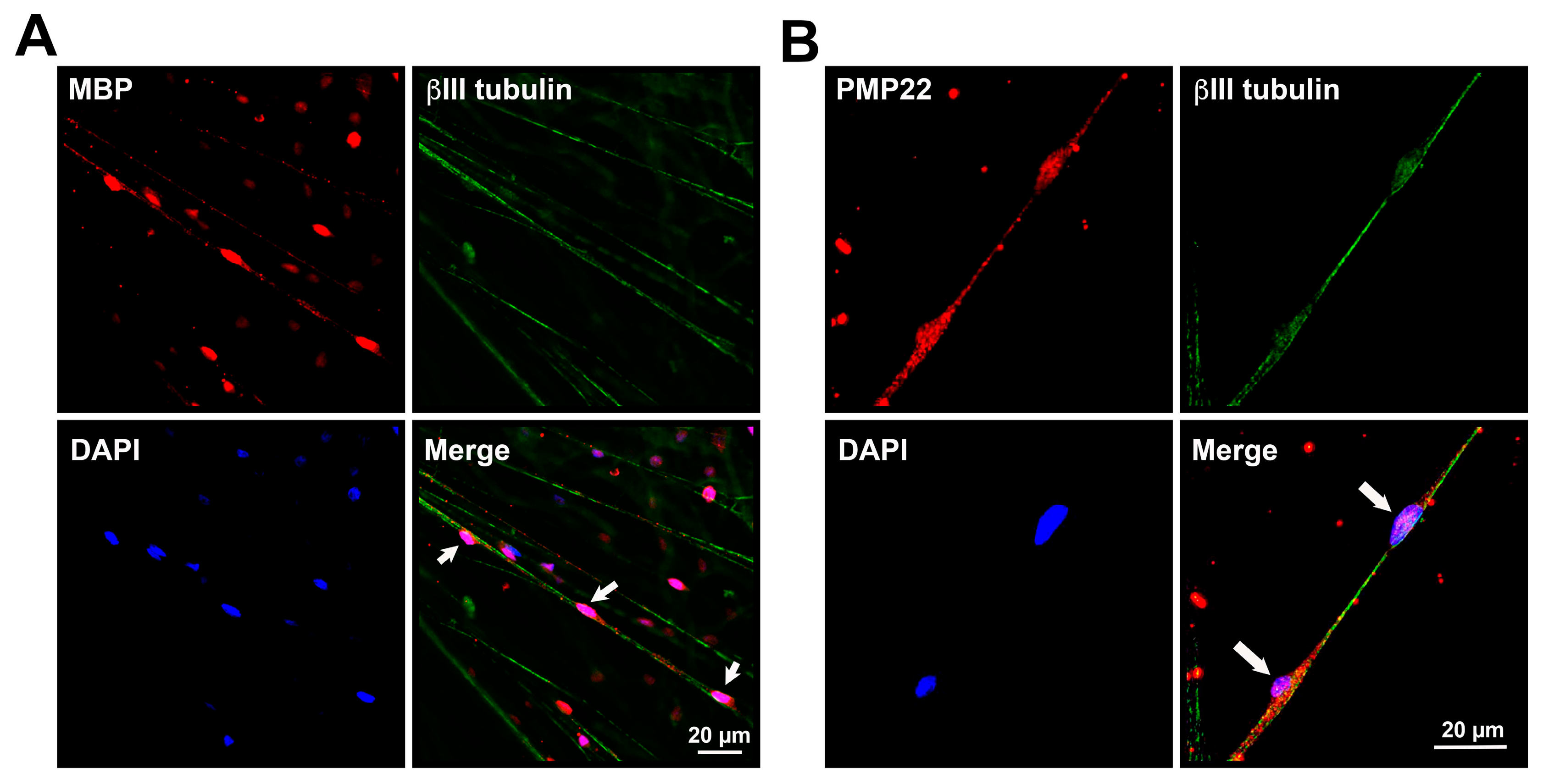

3.1. Differentiation of ND7/23 Cells Prior to Co-Culture

The initial density of ND7/23 cells was adjusted to 3 × 10

3 cells/cm

2, and the cells were maintained in medium supplemented with 1-2% FBS and NEAA, following protocol previously shown to suppress proliferation and maintain the viability of NSC-34 cells and other neurons [

15,

16,

17]. During preliminary trials, we observed that 2% FBS was more effective than 1% in supporting ND7/23 cell survival. Additionally, 10 ng/mL NGF and 5 μM Y-27632 were added to the culture medium, based on prior studies. ND7/23 cells express TrkA, the high-affinity receptor for NGF, and NGF at this concentration is known to promote neurite outgrowth [

25]. Y-27632, a selective ROCK inhibitor, has been reported to enhance neurite outgrowth from primary cultured DRG neurons [

22] and appears to exert similarly effects in ND7/23 cells [

26]. After 5-7 days in culture, most cells exhibited morphological differentiated from a rounded shape (

Figure 2A) to a flat or polygonal form, with elongated neurites (

Figure 2B).

3.2. Maintenance of Co-Culture with Stable Neuron−SC Interactions

Consistent with our previous study using NSC-34 cells [

15], pre-treatment of ND7/23 cells with 1 μg/mL MMC for 12–16 h effectively suppressed their excessive proliferation following co-culture with IFRS1 cells. To reduce MMC-induced cytotoxicity, the co-cultures were maintained in medium supplemented with 5% FBS, ascorbic acid, NGF and the neuroprotective molecule CNTF (

Figure 2C). Ascorbic acid functions as both an antioxidant neuroprotective agent [

27] and a promotor of myelination by enhancing the synthesis and assembly of extracellular matrix proteins [

28]. NGF is essential for the survival of neonatal DRG neurons [

29], while CNTF has been shown to support the survival of both DRG neurons [

30] and neuroblastoma cells [

31]. These culture conditions enabled the long-term (> 21days) maintenance of co-cultures of MMC-treated ND7/23 cells with IFRS1 cells. After 21-28 days of co-culture, ND7/23 cells formed cell body aggregates from which neurite bundles extended in multiple directions. Many IFRS1 cells migrated and adhered to the neurites (

Figure 2D). These morphological features were similar to those observed in our previous co-culture models [

11,

12,

15], indicating stable and effective axon−SC interactions.

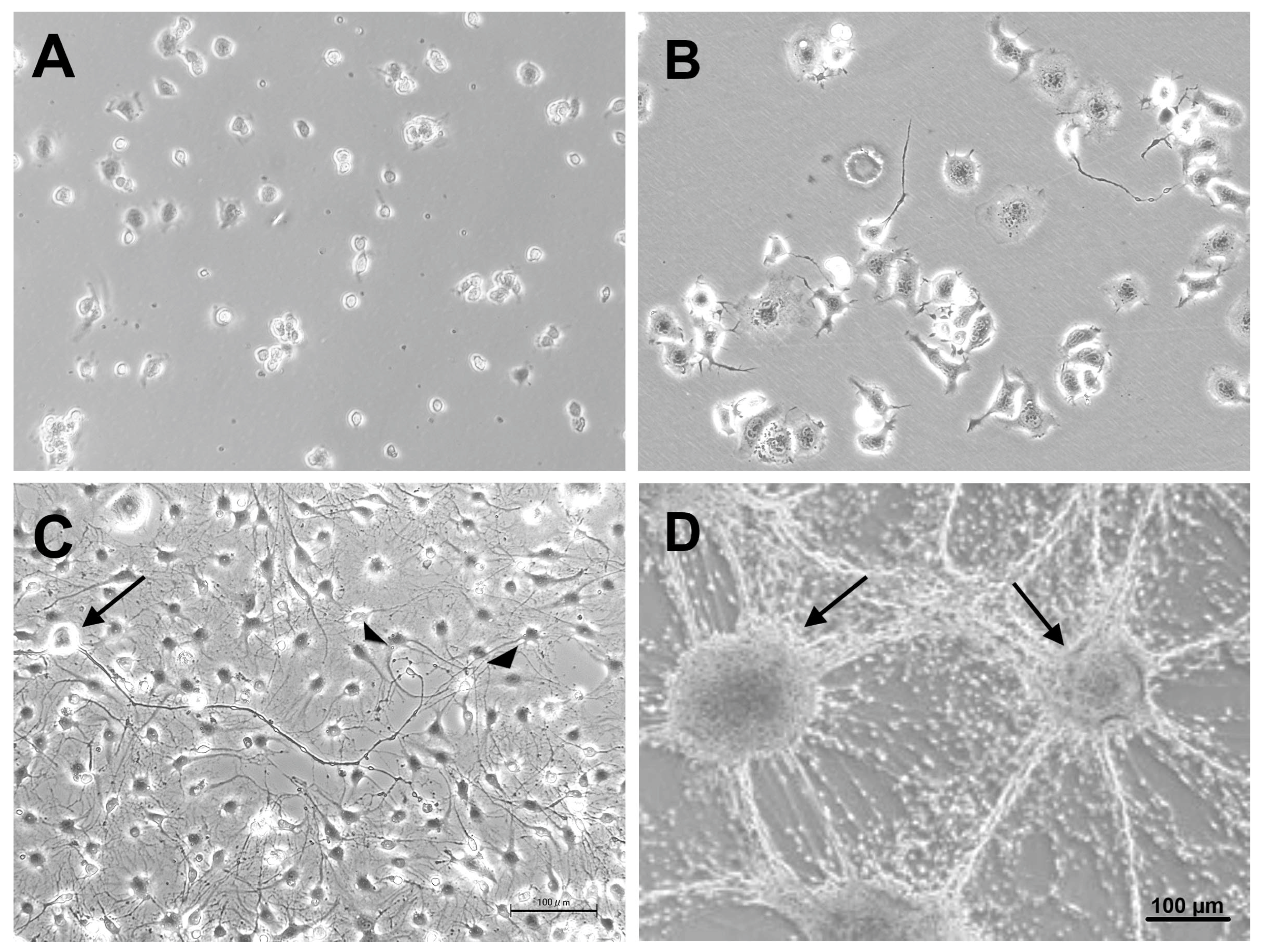

3.3. Myelination in NSC-34−IFRS1 Co-Cultures

Double immunofluorescence staining performed on day 28 of co-culture revealed that IFRS1 cells expressing myelin protein (MBP or PMP22) surrounded βIII tubulin-positive neurites (

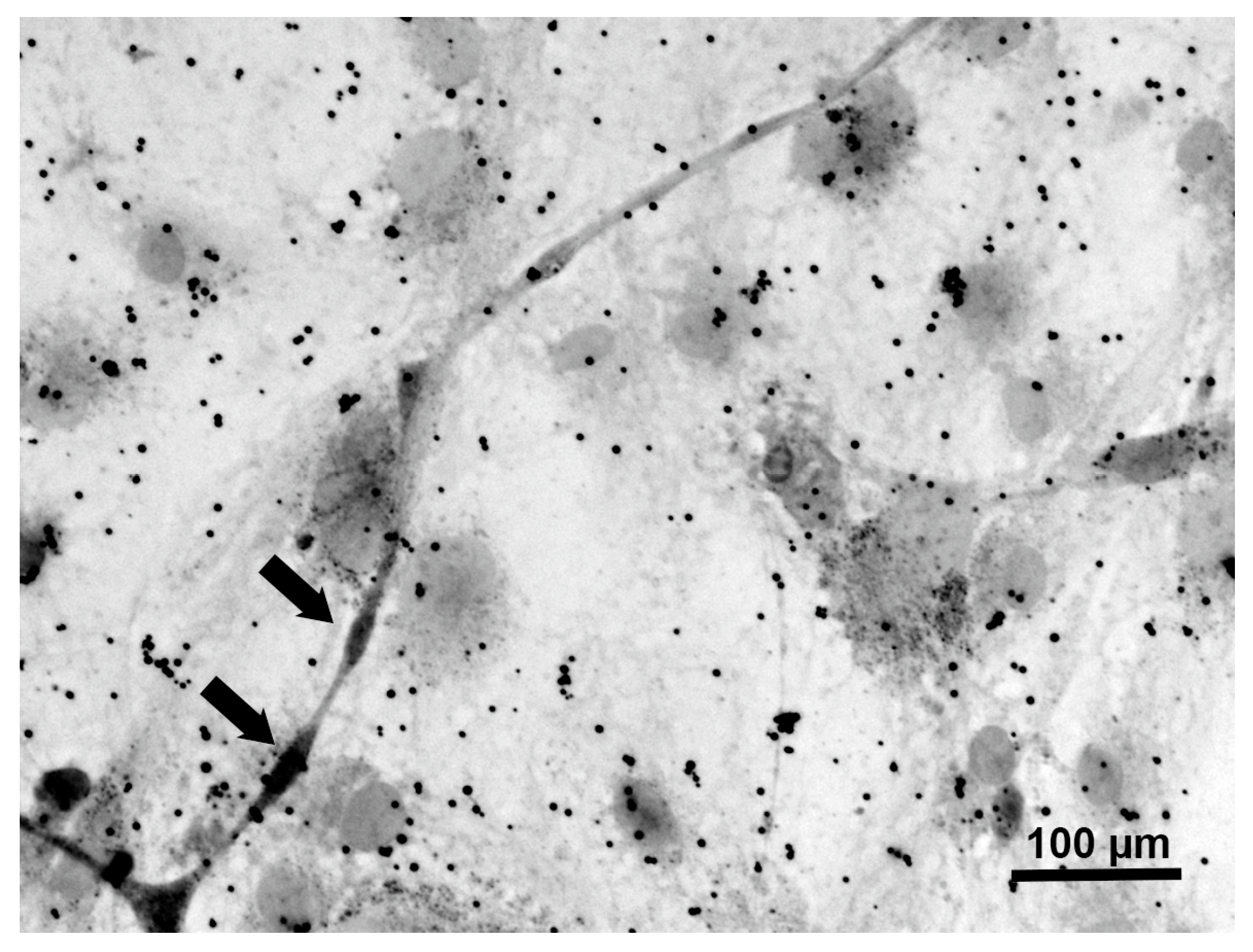

Figure 3). Additionally, myelin segments were visualized by Sudan Black B staining after 28 days of co-culture (

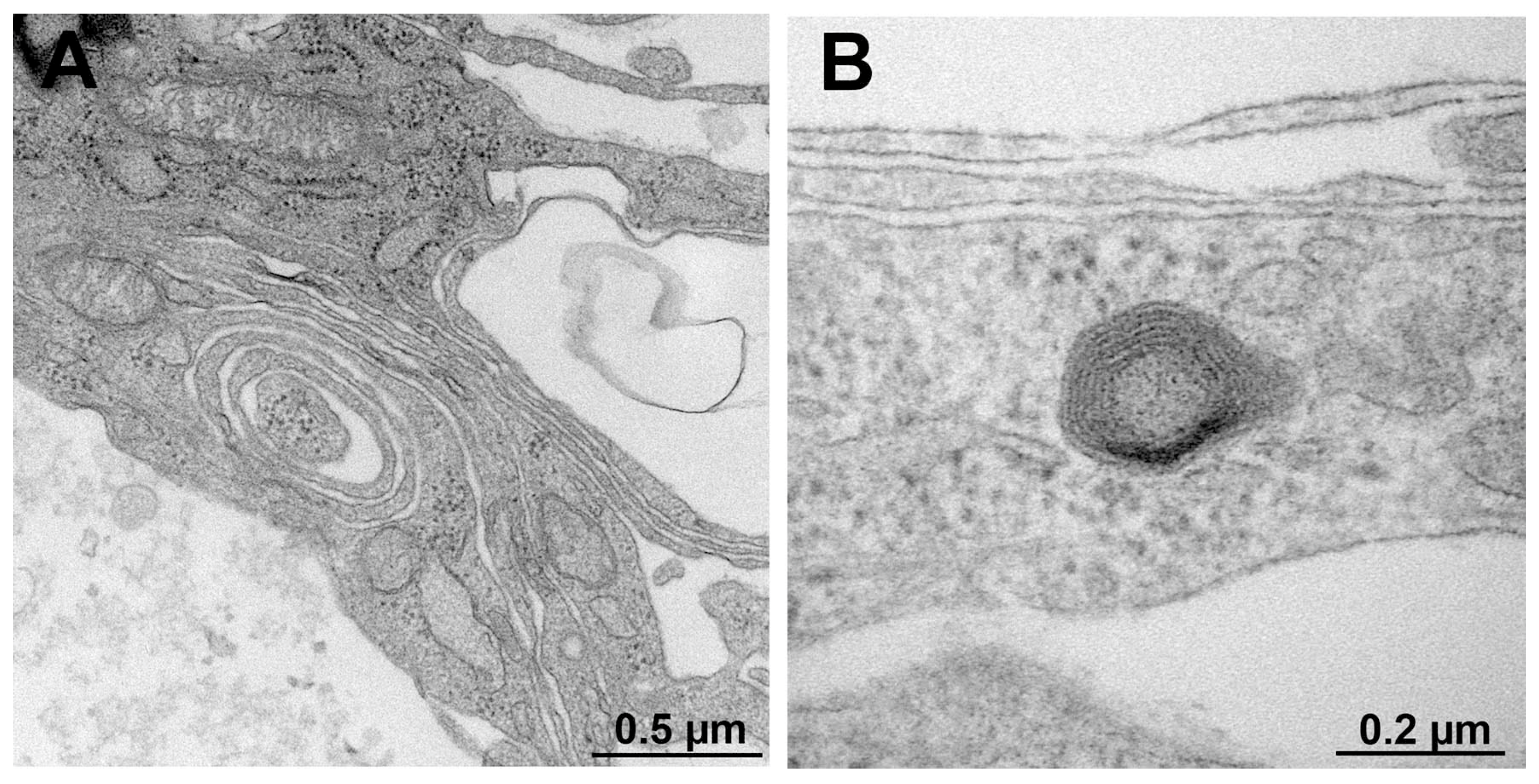

Figure 4). These light microscopic findings were consistent with the formation of promyelinating and myelinating structures as confirmed by electron microscopy (

Figure 5). These results demonstrate that the current protocol enables IFRS1 cells to successfully myelinate neurites extending from ND7/23 cells.

4. Discussion

IFRS1 cells have been shown to myelinate neurites in co-culture not only with primary cultured DRG neurons [

11], but also with neuronal cell lines such as NGF-primed PC12 cells [

12] and NSC-34 motor neuron-like cells [

15]. Building on these findings, the present study successfully established a myelinating co-culture system using IFRS1 cells and ND7/23 sensory neuron-like cells. The strategies employed to suppress cell proliferation, promote neurite outgrowth, and maintain the long-term survival of ND7/23 cells were fundamentally similar to those used in the NSC-34–IFRS1 co-culture system [

15], but were modified to accommodate the phenotypic differences between ND7/23 and NSC-34 cells (

Figure 1). Notably, TrkA, the high-affinity receptor for NGF, is expressed in ND7/23 cells [

25] but not in NSC-34 cells [

32]. NGF, known to be essential for the survival of immature DRG neurons [

29,

33], also exerts neurotrophic effects on ND7/23 cells [

25]. Therefore, ND7/23 cells were maintained in the presence of NGF prior to co-culture, while BDNF was used for NSC-34 cells due to its neurotrophic effects on these TrkB-expressing cells [

17]. During co-culture with IFRS1 cells, NGF was continuously supplied to support neurite elongation and maintenance in ND7/23 cells. Additionally, since RhoA and its downstream target ROCK are well-known inhibitors of axonal regeneration [

34], and RhoA inhibition promotes neurite outgrowth in ND7/23 cells [

26], we used Y-27632–a widely used ROCK inhibitor–instead of RhoA inhibitors. Y27632 has been reported to promote neurite outgrowth in both primary cultured DRG neurons and neuronally differentiated PC12 cells [

22,

35].

The primary obstacle in maintaining the co-culture was the high proliferative activity of ND7/23 cells. Although most ND7/23 cells exhibited morphological differentiation with neurite elongation in response to NGF and Y-27632 (

Figure 2B,C), excessive proliferation remained unavoidable when directly co-cultured with IFRS1 cells (Takaku et al., personal data). This may be attributed to the neuroblastoma components of ND7/23 cells [

19,

20], as well as the secretion of various growth-stimulating factors by IFRS1 cells [

11]. In our previous study [

15], pre-treatment with MMC (1 μg/mL for 12–16 h) effectively suppressed the overgrowth of NSC-34 cells in co-culture with IFRS1 cells. In the present study, the same strategy was successfully applied to ND7/23 cells. To mitigate MMC-induced cytotoxicity, the co-cultures were maintained in serum-containing medium supplemented with neuroprotective agents such as ascorbic acid [

27], NGF [

29], and CNTF [

30,

31]. The neuroprotective effects of CNTF are likely mediated through activation of the JAK2/ STAT3 and PI3K/AKT pathways [

30], as well as enhancement of mitochondrial bioenergetics via NF-κB activation [

36]. Although some ND7/23 cells underwent degeneration and death largely due to MMC cytotoxicity, this did not interfere with sustained axon−SC interactions. After 21-28 days of co-culture, IFRS1 cells were observed to migrate and adhere to the neurite networks extending from ND7/23 cell body aggregates (

Figure 2D). These morphological changes suggested successful myelination, which was confirmed by immunofluorescence (

Figure 3), Sudan Black B staining (

Figure 4), and electron microscopy (

Figure 5). Light microscopy clearly demonstrated segmental myelin structures (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), while electron micrographs revealed transverse views of promyelinating (

Figure 5A) and small myelinating structures (

Figure 5B), although typical compact myelin sheaths, as observed in the co-cultures with IFRS1 cells and primary cultured DRG neurons [

37], were not present. This discrepancy may be due to the greater difficulty in forming compact myelin sheaths when using neuronal cell lines compared to primary cultured neurons. A longer duration (> 4 weeks) of ND7/23⎼IFRS1 co-culture may be required for the development and maturation of myelin sheath; however, most co-cultures became fragile after 5 weeks and detached from the dishes by 6 weeks. Optimizing the methodology to support long-term co-culture remain an important subject for future research.

Recent studies have demonstrated myelination in co-culture systems using iPS cell-derived neurons and SCs [

38], and some of these cell types are now commercially available. However, the purchase of iPS-derived cells is costly, and practical, standardized protocols for achieving myelination in such co-cultures have yet to be fully established. In contrast, our co-culture models using IFRS1 cells with NGF-primed PC12 cells [

12], NSC-34 cells [

15], and ND7/23 cells (this study) consist of well-characterized neuronal and SC lines that can be prepared and maintained using straightforward culture techniques, without the need for genetic manipulation. The NSC-34–IFRS1 co-culture model is particularly suited for studies of motor neuron diseases, while the ND7/23⎼IFRS1 co-culture model provides a useful platform for investigating diabetic and other sensory neuropathies. Our ongoing research aims to determine whether high-glucose conditions [

39] or advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) and their precursors (e.g., glycolaldehyde [

40]) induce axonal degeneration and demyelination-like changes in the co-culture system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.T. and K.S.; validation, S.T. and K.S.; formal analysis, S.T.; investigation, S.T. and K.S.; data curation, S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.T..; writing—review and editing, k.S.; visualization, S.T.; supervision, K.S.; project administration, K.S.; funding acquisition, K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, Culture and Technology of Japan (JSPS KAKENHI 20K07773 and 24K10032).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in this paper are available in the manuscript or from the corresponding author (K.S.).

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Atsufumi Kawabata and Dr. Fumiko Sekiguchi (Laboratory of Pharmacology and Pathophysiology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Kindai University, Higashi-Osaka, Japan) for providing ND7/23 cells, and Dr. Hideji Yako, Dr. Naoko Niimi, Dr. Mari Suzuki, Ms. Sumiko Kunida, Mr. Yuki Takezawa (Diabetic Neuropathy Project, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science, Tokyo, Japan) and Mr. Kentoro Endo (Center for Basic Technology Research, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science, Tokyo, Japan) for their technical support and valuable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AGEs |

Advanced Glycation Endproducts |

| BDNF |

Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| CNTF |

Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor |

| DMEM |

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium |

| FBS |

Fetal Bovine Serum |

| IFRS1 |

Immortalized Fischer344 Rat Schwann Cells 1 |

| iPS |

Induced Pluripotent Stem (Cells) |

| JAK2 |

Janus Kinase 2 |

| MBP |

Myelin Basic Protein |

| MMC |

Mitomycin C |

| NEAA |

Non-Essential Amino Acids |

| NF-κB |

Nuclear Factor-Kappa B |

| NGF |

Nerve Growth Factor |

| PI3K |

Phosphatidyl Inositol-3'-Phosphate-Kinase |

| PMP22 |

Peripheral Myelin Protein 22 |

| PNS |

Peripheral Nervous System |

| ROCK |

Rho-associated Coiled Coil-Forming Kinase |

| SCs |

Schwann Cells |

| STAT3 |

Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 |

References

- Negro, S.; Pirazzini, M.; Rigoni, M. Models and methods to study Schwann cells. J Anat 2022, 241, 1235–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.T.; Kim, J.K.; Tricaud, N. The conceptual introduction of the "demyelinating Schwann cell" in peripheral demyelinating neuropathies. Glia 2019, 67, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jortner, B.S. Common structural lesions of the peripheral nervous system. Toxicol Pathol 2020, 48, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, T.; Iijima, S.; Hoshikawa, S.; Miura, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Oda, H.; Nakamura, K.; Tanaka, S. Opposing extracellular signal-regulated kinase and Akt pathways control Schwann cell myelination. J Neurosci 2004, 24, 6724–6732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Marca, R.; Cerri, F.; Horiuchi, K.; Bachi, A.; Feltri, M.L.; Wrabetz, L.; Blobel, C.P.; Quattrini, A.; Salzer, J.L.; Taveggia, C. TACE (ADAM17) inhibits Schwann cell myelination. Nat Neurosci 2011, 14, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimoto, S.; Tanaka, H.; Okamoto, M.; Okada, K.; Murase, T.; Yoshikawa, H. Methylcobalamin promotes the differentiation of Schwann cells and remyelination in lysophosphatidylcholine-induced demyelination of the rat sciatic nerve. Front Cell Neurosci 2015, 9, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Torii, T.; Takada, S.; Ohno, N.; Saitoh, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Ito, A.; Ogata, T.; Terada, N.; Tanoue, A.; Yamauchi, J. Involvement of the Tyro3 receptor and its intracellular partner Fyn signaling in Schwann cell myelination. Mol Biol Cell 2015, 26, 3489–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobsiger, C.S.; Smith, P.M.; Buchstaller, J.; Schweitzer, B.; Franklin, R.J.; Suter, U.; Taylor, V. SpL201: a conditionally immortalized Schwann cell precursor line that generates myelin. Glia 2001, 36, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, J.T.; Wolterman, R.A.; Baas, F.; ten Asbroek, A.L. Myelination competent conditionally immortalized mouse Schwann cells. J Neurosci Methods 2008, 174, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.J.; Kaller, M.S.; Galino, J.; Willison, H.J.; Rinaldi, S.; Bennett, D.L.H. Co-cultures with stem cell-derived human sensory neurons reveal regulators of peripheral myelination. Brain 2017, 140, 898–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sango, K.; Yanagisawa, H.; Kawakami, E.; Takaku, S.; Ajiki, K.; Watabe, K. Spontaneously immortalized Schwann cells from adult Fischer rat as a valuable tool for exploring neuron-Schwann cell interactions. J Neurosci Res 2011, 89, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sango, K.; Kawakami, E.; Yanagisawa, H.; Takaku, S.; Tsukamoto, M.; Utsunomiya, K.; Watabe, K. Myelination in coculture of established neuronal and Schwann cell lines. Histochem Cell Biol 2012, 137, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, T.; Kawakami, E.; Endo, K.; Misawa, H.; Watabe, K. Myelinating cocultures of rodent stem cell line-derived neurons and immortalized Schwann cells. Neuropathology 2017, 37, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, N.R.; Durham, H.D.; Blusztajn, J.K.; Oda, K.; Tabira, T.; Shaw, I.T.; Dahrouge, S.; Antel, J.P. Neuroblastoma x spinal cord (NSC) hybrid cell lines resemble developing motor neurons. Dev Dyn 1992, 194, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaku, S.; Yako, H.; Niimi, N.; Akamine, T.; Kawanami, D.; Utsunomiya, K.; Sango, K. Establishment of a myelinating co-culture system with a motor neuron-like cell line NSC-34 and an adult rat Schwann cell line IFRS1. Histochem Cell Biol 2018, 149, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, B.; Toku, K.; Maeda, N.; Sakanaka, M.; Tanaka, J. Improvement of the viability of cultured rat neurons by the non-essential amino acids L-serine and glycine that upregulates expression of the anti-apoptotic gene product Bcl-w. Neurosci Lett 2000, 295, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matusica, D.; Fenech, M.P.; Rogers, M.L.; Rush, R.A. Characterization and use of the NSC-34 cell line for study of neurotrophin receptor trafficking. J Neurosci Res 2008, 86, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquarone, M.; de Melo, T.M.; Meireles, F.; Brito-Moreira, J.; Oliveira, G.; Ferreira, S.T.; Castro, N.G.; Tovar-Moll, F.; Houzel, J.C.; Rehen, S.K. Mitomycin-treated undifferentiated embryonic stem cells as a safe and effective therapeutic strategy in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Front Cell Neurosci 2015, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.N.; Bevan, S.J.; Coote, P.R.; Dunn, P.M.; Harmar, A.; Hogan, P.; Latchman, D.S.; Morrison, C.; Rougon, G.; Theveniau, M.; Wheatley, S. Novel cell lines display properties of nociceptive sensory neurons. Proc Biol Sci 1990, 241, 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Haberberger, R.V.; Barry, C.; Matusica, D. Immortalized dorsal root ganglion neuron cell lines. Front Cell Neurosci 2020, 14, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggett, C.J.; Crosier, S.; Manning, P.; Cookson, M.R.; Menzies, F.M.; McNeil, C.J.; Shaw, PJ. Development and characterisation of a glutamate-sensitive motor neurone cell line. J Neurochem 2000, 74, 1895–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, A.E.; Takizawa, B.T.; Strittmatter, S.M. Rho kinase inhibition enhances axonal regeneration in the injured CNS. J Neurosci 2003, 23, 1416–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vent, J.; Wyatt, T.A.; Smith, D.D.; Banerjee, A.; Ludueña, R.F.; Sisson, J.H.; Hallworth, R. Direct involvement of the isotype-specific C-terminus of beta tubulin in ciliary beating. J Cell Sci 2005, 118, 4333–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa, B.B.; Dyck, P.J.; Marks, H.G.; Chance, P.F.; Lupski, J.R. Dejerine–Sottas syndrome associated with point mutation in the peripheral myelin protein 22 (PMP22) gene. Nat Genet 1993, 5, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulmann, L.; Rodeau, J.L.; Danoux, L.; Contet-Audonneau, J.L.; Pauly, G.; Schlichter, R. Dehydroepiandrosterone and neurotrophins favor axonal growth in a sensory neuron-keratinocyte coculture model. Neuroscience 2009, 159, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaux, S.; Cizkova, D.; Mallah, K.; Karnoub, M.A.; Laouby, Z.; Kobeissy, F.; Blasko, J.; Nataf, S.; Pays, L.; Mériaux, C.; Fournier, I.; Salzet, M. RhoA inhibitor treatment at acute phase of spinal cord injury may induce neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis. Mol Cell Proteomics 2017, 16, 1394–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, J.; May, J.M. Ascorbic acid spares alpha-tocopherol and decreases lipid peroxidation in neuronal cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 305, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podratz, J.L.; Rodriguez, E.; Windebank, A.J. Role of the extracellular matrix in myelination of peripheral nerve. Glia 2001, 35, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thippeswamy, T.; McKay, J.S.; Quinn, J.; Morris, R. Either nitric oxide or nerve growth factor is required for dorsal root ganglion neurons to survive during embryonic and neonatal development. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 2005, 154, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sango, K.; Yanagisawa, H.; Komuta, Y.; Si, Y.; Kawano, H. Neuroprotective properties of ciliary neurotrophic factor for cultured adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2008, 130, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhou, F.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, K.; Huang, B.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, L. Neuroprotective properties of ciliary neurotrophic factor on retinoic acid (RA)-predifferentiated SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Folia Neuropathol. 2014, 52, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.J.; Murray, S.S.; Piccenna, L.G.; Lopes, E.C.; Kilpatrick, T.J.; Cheema, S.S. Effect of p75 neurotrophin receptor antagonist on disease progression in transgenic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004, 78, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernsberger, U. Role of neurotrophin signalling in the differentiation of neurons from dorsal root ganglia and sympathetic ganglia. Cell Tissue Res. 2009, 336, 349–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Yamashita, T. Axon growth inhibition by RhoA/ROCK in the central nervous system. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Zhang, H.; Deng, J.; Liu, J.; Wen, J.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Pan, M.; Hu, X.; Guo, J. RhoA-GTPase modulates neurite outgrowth by regulating the expression of spastin and p60-katanin. Cells 2020, 9, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.; Roy Chowdhury, S.K.; Smith, D.R.; Balakrishnan, S.; Tessler, L.; Martens, C.; Morrow, D.; Schartner, E.; Frizzi, K.E.; Calcutt, N.A.; Fernyhough, P. Ciliary neurotrophic factor activates NF-κB to enhance mitochondrial bioenergetics and prevent neuropathy in sensory neurons of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rodents. Neuropharmacology 2013, 65, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sango, K.; Yanagisawa, H.; Takaku, S.; Kawakami, E.; Watabe, K. Immortalized adult rodent Schwann cells as in vitro models to study diabetic neuropathy. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2011, 2011, 374943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Williams, M.; Hawkins, K.; Gallo, L.; Grillo, M.; Akanda, N.; Guo, X.; Lambert, S. ; Hickman. J.J. Establishment of a serum-free human iPSC-derived model of peripheral myelination. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10, 7132–7143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Rouen, S. ; Dobrowsky. R.T. Hyperglycemia and downregulation of caveolin-1 enhance neuregulin-induced demyelination. Glia 2008, 56, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamine, T.; Takaku, S.; Suzuki, M.; Niimi, N.; Yako, H.; Matoba, K.; Kawanami, D.; Utsunomiya, K.; Nishimura, R.; Sango, K. Glycolaldehyde induces sensory neuron death through activation of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p-38 MAP kinase pathways. Histochem Cell Biol. 2020, 153, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).