1. Introduction

Due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 [

1], general lockdowns were decreed by governments worldwide, advising people to isolate at home. These sudden measures affected all sectors of society, from businesses and public services to schools. To mitigate the impacts of the new coronavirus, all face-to-face activities in higher education institutions in different countries were suspended. In Europe, higher education institutions closed in Spain on 12

th March [

2] and in Portugal, the government ordered the closure of universities from 16

th March [

3]. Shortly after, in South America, Brazil also closed universities across the country [

4]. Against this backdrop, university students around the world were confronted with an unexpected transition to an emergency period of online classes [

5], among other unforeseen challenges in their everyday life with potential negative outcomes for their mental health and well-being [

6]. Recent studies on COVID-19’s impact on university students reveal significant lifestyle changes and increased mental health risks, though the full extent of the pandemic’s impacts is still under study [

7]. Moreover, different experiences have been described across countries, thus calling for comparative research [

7]. For instance, during the first wave of COVID-19, anxiety levels were higher among students in the Southern Hemisphere, particularly in Brazil and Oceania, possibly because the academic year had only recently begun [

6]. In Portugal, due to the transition to online learning, students were among those who perceived a higher workload, had lower levels of participation and interest in classes, and displayed increased concern regarding their final evaluation [

6,

8]. In Spain, perhaps as this was one of the most affected countries in Europe by the first wave of COVID-19, most students presented moderate to severe psychological impacts of lockdown [

9].

Also, despite the growing number of studies on the impacts of this first lockdown on university students, and the literature reporting that they were one of the most affected groups [

10], comprehensive literature in this field is still scarce. Most of the identified studies are overly descriptive, focusing on small samples normally restricted to a single academic field and/or institution [

8], covering a small set of variables, mainly students’ primary sources of stress and mental health [

5,

6], while the impacts on other spheres of students’ lives, such as their academic performance remain unclear. Following the transition to online learning, some studies reported a decrease in students’ academic performance [

11] while several found no differences [

12,

13] and others even reported an increase in academic performance [

14,

15].

According to the

Transactional Model of Stress [

16] and the

Job Demands and Resources Model (JD-R) [

17], the stress response emerges from a perceived imbalance between the demands and the resources available to meet them, subsequently impacting emotional (e.g., well-being) and behavioral (e.g., performance) experience. As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, the demands experienced by university students increased, which, in light of these models, may directly affect the experience of stress and, consequently, students’ personal and academic well-being and performance. However, inconsistent results are found in the literature, thus reinforcing the need for additional research of a comparative nature to better understand how the first COVID-19 lockdown impacted university students globally [

7]. Hence, the present study aims to understand differences in perceived academic stress factors, personal and academic well-being (engagement) and academic performance during the first COVID-19 lockdown of Portuguese, Spanish and Brazilian university; and to explore the role of perceived stress, personal well-being and academic engagement in the explanation of the academic performance of university students during that time.

1.1. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on University Students: Perceived Stress and Well-Being

The literature indicates that both previous lockdowns and COVID-19 have adverse and lasting effects on the general population’s well-being and mental health, including increased depressive symptoms, anxiety, insomnia, frustration, boredom, irritability, stress levels, emotional exhaustion, and post-traumatic stress [

18,

19].Worldwide research on the impacts of COVID-19 on specific groups of the population suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has more negatively impacted female, full-time workers and undergraduate students’ well-being and mental health [

6,

10,

20,

21,

22].

University students, acknowledged as a vulnerable group concerning mental health, face challenges due to developmental tasks of emerging adulthood (e.g., identity exploration, relationship formation, education and career pursuits, financial independence, autonomy, worldview exploration, health maintenance, civic responsibilities) [

23] and stressors linked with transitioning to higher education (e.g., moving from home, adjusting to new environments, life-stage changes, forming new relationships, managing time, financial constraints) [

24]. The initial COVID-19 lockdown significantly affected university students’ lives, causing abrupt disruptions to their daily routines and amplifying uncertainty about their near and distant futures [

6,

25], exacerbating the mental health challenges faced by this already vulnerable demographic [

22,

26].

A global study encompassing 62 countries revealed that COVID-19 impacted university students in various ways, introducing new stressors across academic (e.g., adapting to online learning, changes in communication and support, new assessment methods, managing time and workload), social (e.g., social isolation, canceled plans, uncertainty about lockdown duration), economic (e.g., job insecurity, future education and career concerns), and emotional (e.g., fear, anxiety, boredom) domains [

6,

7,

8]. Broadly speaking, these findings suggest that university students’ stress experiences were heavily influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic on a worldwide scale. Accordingly, the following research question was established:

Q1: What were the most frequent academic stress sources perceived by Portuguese, Spanish and Brazilian university students during the first COVID-19 lockdown? Were there cross-country differences?

According to the

Transactional Model of Stress, stress arises from a cognitive appraisal of an imbalance between life demands and the available resources to respond to those demands [

16]. When facing stressful situations, coping responses are determinants of successful adaptations and have been recognized as the more consistent predictors of well-being, namely in university students [

16,

24,

27]. Accordingly, without the adequate resources to cope with the unforeseen demands created by the first COVID-19 lockdown, university students faced a greater risk of developing prolonged stress reactions and, consequently, of poorer well-being. Prior studies have corroborated this idea, revealing that students perceived an enhancement of their stress symptoms (e.g., high levels of anxiety and depression, emotional exhaustion, concentration difficulties, sleep impairment) [

6,

7,

8,

10,

20,

26,

28]. However, studies remain scarce and non-consensual. Some research suggests decreased well-being among students following the first COVID-19 lockdown [

7,

22,

26,

28,

29], while others report unchanged well-being levels [

30]. These varied outcomes likely stem from differences in COVID-19’s manifestation and progression across the studied countries, along with their respective responses. Therefore, the following hypothesis was tested:

Hypothesis 1: Perceived academic stress intensity will be negatively associated with well-being.

1.2. Impacts of Perceived Stress on University Students’ Academic Performance: The Mediating Role of Personal and Academic Well-Being

While positive effects of the COVID-19 lockdown, such as improved self-care and autonomy through online learning, have been noted, literature suggests that the negative impacts outweigh the positive. The positive effects are linked to contextual factors like institutional support and individual coping mechanisms such as self-regulated learning skills and social-emotional competencies [

20]. Various studies have consistently highlighted the significant role of individual coping responses alongside perceived stress in the well-being and academic performance of university students [

31,

32,

33]. However, regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic performance, findings remain inconclusive [

13]. To grasp the factors contributing to these inconsistent findings, researchers are exploring socioeconomic (e.g., income levels; [

11]), contextual (e.g., teachers’ expectations, perceived support; [

20,

34]), and individual variables (e.g., attitude towards online learning, self-efficacy; [

12,

13]) as potential moderators of the pandemic’s impact on academic performance. However, further research is needed to deepen our understanding and help mitigate the pandemic’s adverse effects, particularly on university students’ academic performance [

7]. Therefore, the following research question was established:

Q2: Did the first COVID-19 lockdown impacted university students perceived academic stress intensity, well-being, engagement and academic performance? Were there cross-country differences?

Some authors have applied models examining contextual factors that influence workers’ occupational health to gain insights into higher education students’ well-being. For example, a study [

35] identified connections between obstacles/facilitators perception and students’ burnout and engagement. Another study [

36] found associations between peer social support, working conditions and role clarity and subjective well-being. Overall, these studies suggest that work context factors may influence students’ well-being in higher education. Previous studies employing the JD-R [

17] found that excessive academic demands coupled with inadequate resources increase the risk of prolonged stress reactions among students. Conversely, adequate perceived resources to meet these demands contribute to increased academic engagement [

24,

35]. In fact, academic engagement is considered an important indicator of university students’ well-being, since it is viewed as a fulfilling and positive work-related state of mind which is characterized by a sense of vigor (i.e., high levels of energy, resilience, investment and persistence towards work and work challenges), dedication (i.e., a sense of commitment to one’s work reflecting enthusiasm, a sense of purpose, inspiration, and pride), and absorption (i.e., an experience of full concentration and immersion in work that is pleasant and leads to the loss of the notion of time passing) [

33]. Additionally, academic engagement has been positively related to university students’ academic performance [

31,

33].

Therefore, in a context in which emergency online learning has defied students’ self-regulation, autonomy, self-efficacy and resilience [

20,

37], academic engagement may be a relevant variable to help understand and further explain the COVID-19 pandemic impacts on students’ academic performance. Accordingly, some studies have begun to describe the impacts of the COVID-19 outbreak and emergency online learning on university students’ engagement [

38,

39,

40], and corroborate the role that students’ personal well-being and academic engagement may play in academic performance. Research has found that during the COVID-19 outbreak, students’ personal well-being was positively associated with engagement [

38], and that engagement was negatively associated with students’ views of emergency online experiences as unpleasant [

37]. A study with Romanian students identified a decrease in students’ dedication and vigor during emergency online learning, in a context of increased stress and reduced well-being, despite reports of an increase in absorption [

40]. A significant decrease in engagement was also found in Canadian students, accompanied by reduced perceptions of academic success [

39]. Despite these preliminary results, to the best of our knowledge, the potentially protective role of students’ engagement in the relationship between academic stress and performance during the first COVID-19 lockdown is yet to be studied. In view of the above, the following hypotheses were established regarding our second research aim:

Hypothesis 2: Personal well-being will be positively associated with academic engagement.

Hypothesis 3: Academic engagement will be positively associated with academic performance.

Hypothesis 4: Personal well-being and academic engagement will mediate the relationship between perceived academic stress intensity and academic performance, and the indirect effect will be lower than the direct effect.

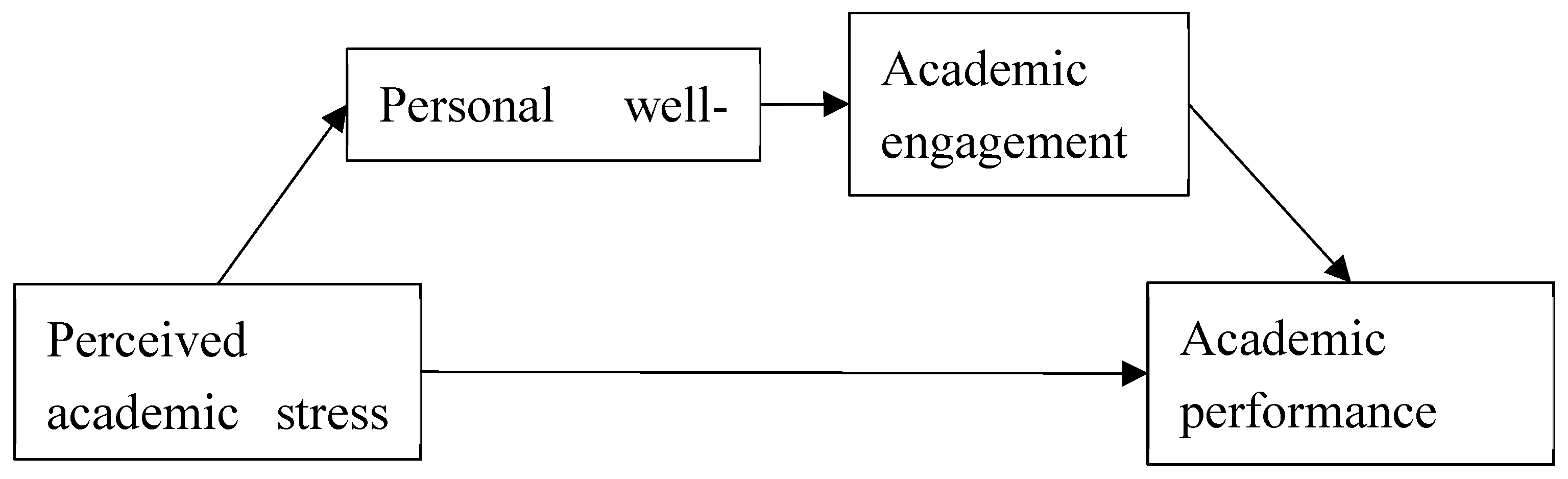

The proposed model of this study, shown in

Figure 1, conceptualizes university students’ personal well-being and engagement as mediators between their perceived academic stress and performance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

Our sample comprised university students from Portuguese, Spanish, and Brazilian public universities. These countries were selected due to their varying impacts from the pandemic despite certain similarities and geographical/cultural proximities [

6]. We chose two countries with similar university systems and academic calendars but differing impacts from the 1st wave of Covid-19 (e.g., Spain was severely affected compared to Portugal), along with a third country with a distinct academic calendar (e.g., Brazil’s academic year starts in March, unlike Portugal and Spain’s September start), to explore potential differences in students’ academic experiences during the initial Covid-19 lockdown.Within these countries, the sample was selected by convenience due to previous working relationships between the institutions.

The sample consisted of 1081 university students (78.17% female; M = 25.43 years, SD = 9.27), comprising 534 students from Portugal, 371 students from Spain and 176 students from Brazil. The sample included undergraduate students (65%), as well as master’s (28%) and PhD students (7%). The degree programs attended by the students spanned various areas, ranging from Humanities and Social Sciences, Legal and International Studies, Economics and Management, Engineering and Technology and Health Sciences. Our sample also included student workers (Portugal = 23.4%, Spain = 36.1% and Brazil = 37.4%).

The study was approved by the Scientific and Ethical Councils of the Faculty of Psychology of the University of Lisbon, and authorized by the dean of each university. The data was collected using an online survey between October 2020 and January 2021. Students were invited via email, sent by their respective university departments to the mailing list, and asked to voluntarily complete an online questionnaire. The research team had no prior relationship with the participants, and no compensation was provided. Participants were informed about the research’s purpose at the start of the questionnaire and asked for their consent to participate. Upon giving consent, participants completed the survey, which lasted an average of 20 minutes.

Participants completed surveys in their native language (Spanish or Portuguese) using validated versions of the measures. They were instructed to refer to the period of the first lockdown (March through July 2020). To enhance data validity, only complete responses were included [

41], text entry boxes were used for collecting sociodemographic data to identify random responses, spam, or autofill software usage [

42], and a statement promoting honesty was included in the survey introduction to mitigate Social Desirability Bias [

43].

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Perceived Academic Stress

Perceived academic stress was measured in two ways. First, the students were asked to describe in writing the three academic stressors they had most frequently experienced during the first COVID-19 lockdown. Additionally, overall academic stress intensity was measured with a single item by asking students “To what extent do you consider that your academic activity, in general, was stress-generating over those months?” This item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = not generating stress at all to 5 = extremely stress- generating.

2.2.2. Personal Well-Being

The Mental Health Continuum – Short Form (MHC-SF) [

44] measures personal (subjective) well-being through 14 items focusing on feelings of emotional, psychological, and social well-being. The participants were asked to state how often they had experienced those feelings (e.g., “How often did you feel happy?”, α = .93, see

Table 2) during the first COVID -19 outbreak on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 =

never to 6 =

every day. The MHC-SF used with university students [

45] has revealed good psychometric properties.

2.2.3. Academic Engagement

Academic engagement was measured with the 9-item short version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale for students (UWES-S) [

33,

46]. UWES-S is a self-report measure concerning feelings of vigor, dedication and absorption. Students were requested to report, on a 7-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 =

never to 7 =

every day, how often they had experienced those feelings (e.g., “When I am doing my work as a student, I feel bursting with energy”, α = .92, see

Table 2) during the first COVID-19 lockdown. UWES-S has obtained good psychometric properties in studies with university students [

33].

2.2.4. Academic Performance

Academic performance was measured by asking students to compare the average marks they obtained in the 2nd semester course units of 2019/2020 with the average of those obtained in the first semester. Answers were given on a 3-point scale (lower, the same or higher).

2.3. Data Analysis

Data analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 24. Regarding perceived academic stress sources, a mixed deductive/inductive thematic content analysis was performed following Bardin’s guidelines [

47]. Taking the JD-R [

7] as a framework, a deductive analysis was initially conducted, in which two overarching Demands and Resources categories were considered

a priori. To deepen the analysis, an inductive analysis of the specific demands and (lack of) resources emerging from the students’ responses was then conducted and they were added to the category system (e.g., Demands for distance learning). A frequency analysis of each subcategory was subsequently performed. Since each participant could list up to three stressors, each subcategory was assigned a respective frequency of response, ranging from 0 (never mentioned) to 3 (mentioned three times). Chi-square analyses were performed between each subcategory according to nationality, and contingency tables were analyzed. To ensure validity and reliability of the analysis, two coders initially categorized all responses following exclusivity, homogeneity, pertinence, objectivity, and productivity assumptions [

47]. Then, a third independent coder categorized 100% of the responses into the category system. Divergences were discussed until an agreement percentage of 100% was attained. Descriptive statistics and ANOVAs were employed to examine cross-country variations in overall academic stress intensity, personal well-being, academic engagement, and academic performance. Pearson correlations were also computed.

Lastly, for our hypotheses testing, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed with Mplus 8 to ensure that the established multi-item scales were distinct from each other [

48]. The hypothesized three-factor model (i.e., perceived academic stress intensity, personal well-being, and academic engagement) fit the data significantly better (χ

2 (207) = 2145.51,

p < .001) than both the baseline (Δχ

2 (231) = 18410.86,

p < .001) and the one-factor (Δχ

2 (211) = 17503.49,

p < .001) models. The standardized parameter estimates (factor loadings) of the best fitting three-factor model were all significant (

p < .01) and ranged from .48 to .88. The measurement model demonstrated an acceptable fit: a normed comparative fit index (CFI) of .90, a standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) of .04, and a root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) of .08. Overall, the indices demonstrated an acceptable fit [

49]. Coefficient alphas of the multiple-item measures were greater than the generally accepted threshold of .70 [

50].

Our hypotheses were tested using manifest (observed) variable path analysis with PROCESS v4.0 macro for SPSS [

51]. This methodology was adopted as it allows for the simultaneous modelling of individual and multiple mediation paths. In this model there is no requirement for a total effect between X and Y to be present when testing for a mediation, as the focus of a mediation test is on the indirect effect of X on Y through the mediators [

51,

52]. Also, PROCESS made it possible to compare the indirect effects through various paths including each mediator separately and a serial mediation through two sequential mediators. All the paths were included in our models to avoid biasing the estimate of the serial indirect effect predicted in Hypothesis 4 [

51]. Three demographic variables were included in the analysis as control variables: age (in years), sex (female = 1; male = 0), and nationality (by creating three dummy variables; Brazil = 0; Portugal = 1; Spain = 1). These variables were chosen since, following prior literature, they appear to impact the variables under study.

3. Results

3.1. Perceived Academic Stress Sources

Full description of the perceived academic stress sources identified by the students during the first COVID-19 lockdown is depicted in

Table S1, Supplementary material.

Concerning the situations perceived as more stressful during the COVID-19 lockdown, demands related to experiencing emotional distress were the most frequently mentioned with 54% of the participants considering them a major stressor. In addition, work overload (29%), (lack of) institutional support (29%), remote classes (27%), assessment (25%), and isolation (22%) were considered a major source of stress by the participants. Also, the lack of technological resources was deemed a major source of stress for 10% of the participants. The remaining situations were regarded as a major source of stress for a proportion of the participants ranging from 2% to 4%.

3.1.1. Cross-Country Differences

In a comparison of the countries, using Chi-square tests, significant differences between Portugal and Spain were identified in perception of demands related to experiencing emotional distress (χ

2 = 5.76,

p < .05), academic assessment (χ

2 = 3.76,

p< .05), remote classes (χ

2 = 4.61,

p < .05), isolation (χ

2 = 4.11,

p< .05), and management of family, professional and academic interests (χ

2 = 8.71,

p < .01). A significant difference between Portugal and Brazil was also found in perception of demands related to experiencing emotional distress (χ

2 = 5.52,

p < .05). The frequency and proportions of stress sources by country are depicted in

Table 1. In the comparisons where, at least on cell, had less than 5 observations we used the Fisher exact test (e.g., finance, space, and research). No significant differences were found.

3.2. Academic Stress Intensity, Well-Being, Engagement and Academic Performance

The descriptive statistics and correlations among the remaining variables for the total sample are presented in

Table 2. As expected, academic performance was positively related to personal well-being (

r = .14,

p < .01), positively related to academic engagement (

r = .21,

p < .01), and negatively related to perceived academic stress intensity (

r = −.13,

p < .01). In addition, academic engagement was positively related to personal well-being (

r = –.57,

p < .01) and negatively related to perceived academic stress intensity (

r = -.33,

p < .01). Finally, among the control variables, females were more likely to perceive higher academic stress than males (

r = .11,

p < .01). However, there were no significant differences between males and females in terms of personal well-being (

r = -.04,

n.s.) or academic engagement (

r = .04,

n.s.). In addition, the older participants were more engaged with academic work (

r = .16,

p < .01), had higher personal well-being (

r = .17,

p < .01), and perceived less academic stress (

r = −.11,

p < .01) than the younger participants.

Table 1.

Frequency and proportions of stress sources by country.

Table 1.

Frequency and proportions of stress sources by country.

| |

|

WO |

Distress |

Assmnt |

Remote |

Isolation |

Support |

Tech |

Finance |

Space |

Bibliographic |

WLB |

Research |

| Brazil |

Sum |

27 |

56 |

19 |

21 |

21 |

31 |

9 |

2 |

5 |

6 |

2 |

1 |

| |

% |

30 |

62 |

21 |

23 |

23 |

34 |

10 |

2 |

5 |

7 |

2 |

1 |

| Spain |

Sum |

78 |

153 |

56 |

62 |

47 |

68 |

25 |

12 |

6 |

6 |

19 |

5 |

| |

% |

30 |

58 |

21 |

23 |

18 |

26 |

9 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

7 |

2 |

| Portugal |

Sum |

89 |

151 |

89 |

98 |

77 |

98 |

31 |

13 |

16 |

16 |

7 |

10 |

| |

% |

28 |

48 |

28 |

31 |

25 |

31 |

10 |

4 |

5 |

5 |

2 |

3 |

| Total |

Sum |

194 |

360 |

164 |

181 |

145 |

197 |

65 |

27 |

27 |

28 |

28 |

16 |

| |

% |

29 |

54 |

25 |

27 |

22 |

29 |

10 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

| |

Mean |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

| 1. Academic performance |

2.16 |

.745 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2. Academic engagement |

3.95 |

1.54 |

.21** |

(.93) |

|

|

|

| 3. Personal well-being |

3.36 |

1.09 |

.14** |

.57** |

(.92) |

|

|

| 4. Perceived academic stress intensity |

3.73 |

0.97 |

-.13** |

-.33** |

-.31** |

- |

|

| 5. Age |

25.43 |

9.27 |

-.05 |

.16** |

.17** |

-.11** |

- |

| 6. Gender |

0.78 |

0.41 |

.04 |

.04 |

-.04 |

.11* |

-.12** |

3.2.1. Cross-Country Differences

To ascertain the differences between the three sub-samples a one-way ANOVA was conducted on perceived academic stress intensity, well-being, engagement and academic performance. The means and standard deviation of all the variables for each country may be found in

Table 3. The ANOVA results showed that the Portuguese participants (

M = 4.13,

SD = 1.59) had significantly higher levels of engagement than the Spanish’s (

M = 3.67,

SD = 1.40) who, in turn, had significantly lower levels of engagement than the Brazilians (

M = 4.00,

SD = 1.58) (

F = 10.17,

p < .001). Similarly, the Portuguese participants (

M = 3.56,

SD = 1.13) had significantly higher levels of well-being than the Spanish (

M = 3.09,

SD = .95) and Brazilian participants (

M = 3.29,

SD = 1.09), and the Spanish had lower levels of well-being than the Brazilian participants (

F = 21.95,

p < .001). As for academic performance, the Brazilian participants (

M = 2.03,

SD = .70) indicated lower performance than the Portuguese (

M = 2.17,

SD = .76) and Spanish participants (

M = 2.22,

SD = .74), with no difference between those two samples (

F = 3.85,

p < .022). Finally, no significant differences were found in perceived academic stress intensity among the three countries (

F = 1.33,

p <.266).

3.3. Test of Proposed Conceptual Model: Mediation Analysis

The serial multiple mediation results are provided in

Table 4. As recommended by [

52], all possible direct effects were included in the analysis to estimate the serial indirect effect. In line with our first hypothesis (

Table 4, model 1), perceived academic stress intensity was negatively related to personal well-being (

b = -.32,

p < .01). Hypothesis 2 (

Table 4, model 2) was also corroborated as personal well-being was positively related to academic engagement (

b = .71,

p < .01). In model 2, perceived academic stress intensity was still significant (

b = -.28,

p < .01). Likewise, Hypothesis 3 (

Table 4, model 3) was supported with academic engagement being positively associated with academic performance (

b = .09,

p < .01). In model 3, personal well-being was no longer significant, and although the effect of perceived academic stress on academic performance remained significant it decreased in size. These findings provide initial support for a mediation effect.

To test Hypothesis 4 that the relationship between perceived academic stress intensity and academic performance would be mediated sequentially through personal well-being and academic engagement, the indirect effects (reported in

Table 4) were examined. From a comprehensive perspective, and as recommended by [

51], three indirect paths were estimated and tested simultaneously using bootstrap confidence intervals based on 5000 bootstrap samples and using the PROCESS 4.3 tool. The indirect effect of perceived academic stress intensity on academic performance through personal well-being was non-significant (point estimate = -.01; 95% CI [−0.03, 0.01]). Nevertheless, the indirect effect of perceived academic stress intensity on academic performance through academic engagement was negative and significant (point estimate = -.03; 95% CI [−0.04, −0.01]). Consequently, the serial indirect effect of perceived academic stress intensity on academic performance through personal well-being and academic engagement was negative and significant (point estimate = -.02; 95% CI [−0.03, −0.01]), thus supporting Hypothesis 4. Overall, the results suggest an indirect effect of perceived academic stress on academic performance through personal well-being and academic engagement.

4. Discussion

This study sought to investigate impacts of the initial COVID-19 lockdown on university students from different countries. It aimed to identify key academic stressors and explore the role of perceived academic stress intensity, personal well-being, and academic engagement in the explanation of their academic performance during that period. Additionally, it examined differences in these factors among Portuguese, Spanish, and Brazilian university students, aligning with literature emphasizing the importance of understanding pandemic impacts across different countries.

4.1. Q1: What Were the Most Frequent Academic Stress Sources Perceived by Portuguese, Spanish and Brazilian University Students During the First COVID-19 Lockdown? Were There Cross-Country Differences?

Despite being prompted to identify sources of academic stress, findings indicate that

demands related to experiencing emotional distress emerges as a primary stressor, acknowledged by over half of the participants. This underscores the challenge of managing emotional distress as a key impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. This strain, expressed through increased symptoms of anxiety and depression previously linked to COVID-19 [

18,

19] reproduces a direct impact on the well-being and health of the populations, particularly the younger individuals [

6,

10,

21].The university students also identified

work overload, lack of institutional support, remote classes, assessments, and

isolation as major sources of academic stress stemming from the first COVID-19 lockdown, aligning with prior literature highlighting similar challenges faced by university students in their academic pursuits amid the pandemic [

7].

As for the cross-country comparisons on perceived sources of academic stress stemming from COVID-19, our findings suggest that the Portuguese students perceived less demands related to experiencing emotional distress, compared to the Spanish and Brazilian students. The Spanish students also referred to managing family, professional and academic interests as being more stressful compared to the Portuguese students. In turn, the Portuguese university students reported more stressors associated with the transition to online learning (i.e., remote classes, academic assessment) than the Spanish students.

4.2. Q2: Did the First COVID-19 Lockdown Impacted University Students Perceived Academic Stress Intensity, Well-Being, Engagement, and Academic Performance? Were There Cross-Country Differences?

Descriptive statistics also showed that, overall, university students experienced high academic stress levels, particularly the females and younger participants, which is consistent with prior scientific evidence regarding Covid-19 [

10]. Moreover, older participants exhibited higher academic engagement and personal well-being compared to younger participants. This aligns with developmental psychology literature [

23,

24], suggesting that younger students may still be in the process of developing emotional coping mechanisms and adapting to university compared to their older counterparts. However, previous research on age-related differences in engagement and well-being is inconsistent. While some studies suggest a general increase in engagement with age [

53], others report minimal or no age differences in engagement [

46,

54]. Similarly, results on personal well-being differences across the lifespan are not curvilinear or consistent between components: emotional well-being seems to decrease during adolescence and to increase during adulthood but the same does not happen with other well-being components (e.g., psychological) [

55].

Regarding personal well-being and academic engagement, the pandemic appears to have had a significant impact. Our data indicated that both were rated slightly below the midpoint of the scale. Relatively recent pre-pandemic research with university students has depicted Portuguese university students presented moderately high levels of personal well-being [

36] and academic engagement [

31], with mean values above the mid-point of the scale for both variables. The same pattern was found regarding Spanish university students, who also presented moderately high levels of academic engagement [

31] in a pre-pandemic study. Conversely, our findings showed that academic performance tended to remain similar to pre-pandemic results, according to the students. Taken together, these results suggest that, even though students were apparently able to maintain their academic performance, the first COVID-19 lockdown impaired their well-being and academic engagement.

Furthermore, while no cross-country differences emerged in perceived academic stress intensity, Portuguese students presented the highest levels of personal well-being (compared to the Spanish and Brazilian students), and Spanish students reported the lowest levels of both personal well-being and academic engagement (compared to the Portuguese and Brazilian students). Nevertheless, the Brazilian students indicated lower academic performance than the Portuguese and Spanish students.

These findings align with previous literature [

6,

8] and may arise from variations in the experiences of the first COVID-19 lockdown among these countries. As Spain was one of the most affected countries in Europe by the first wave of COVID-19 [

9], Spanish students likely faced heightened disruption, emotional distress, and challenges in balancing life roles. In contrast, Portugal experienced the first lockdown with less social alarm, early government intervention, and fewer cases and deaths, potentially making adaptation to new teaching methods the primary challenge for students [

20], thereby explaining the greater impact on academic life management in Portugal. Another explanatory hypothesis could be that the Portuguese university system was less prepared for this abrupt transition than its Spanish counterpart. Lastly, in keeping with previous studies [

6], Brazilian students exhibited greater emotional distress than Portuguese students, alongside lower academic performance rates compared to Portuguese and Spanish students. These findings might relate to Brazil’s academic year being in its early stages and they may also depict the slightly higher prevalence of student workers in the Brazilian sample. Certain jobs, particularly those more precarious that support working students’ studies, were significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially influencing the emotional well-being and academic performance of Brazilian students.

4.3. Test of Hypotheses: Personal Well-Being and Academic Engagement Will Mediate the Relationship Between Perceived Academic Stress Intensity and Academic Performance, and the Indirect Effect Will Be Lower than the Direct Effect.

Additionally, our findings offer preliminary support for the mediating role of personal well-being and academic engagement in the relationship between perceived stress and university students’ academic performance, indicating that higher levels of personal well-being and academic engagement are associated with reduced stress effects on academic performance. However, the indirect effect was only significant in the presence of academic engagement, suggesting that the relationship between academic stress and academic performance relies more on academic engagement than on personal well-being [

37,

38,

39]. This result aligns with previous studies, including pre-pandemic ones [

31,

45], and other following the pandemic outbreak [

39] indicating a positive association between academic engagement and university students’ academic performance. One possible explanation for this result is that engagement, conceptualized in relation to students’ academic tasks and activities [

33], is directly associated with students’ perception of resources to meet academic demands [

24,

32], whereas personal well-being, encompassing a broader evaluation of emotional experience, life satisfaction and psychosocial functioning [

44], may be less directly linked to academic performance.

5. Limitations

Our study is not without its limitations. One limitation of this study is that it relied on a non-probabilistic sample, thus the results should be interpreted with caution and cannot be generalized. Additionally, a more detailed analysis of the model across different disciplines (e.g., Science, Engineering, Humanities and Social Sciences) and educational levels (i.e., undergraduate, master and PhD students) would be interesting in future studies. Furthermore, females were overrepresented in the sample. As the data was collected during the pandemic period, this was conducted exclusively online. Even though an online data validation protocol was used, future research should further explore these variables and their associations resorting to different data collection methods and a probabilistic and gender balanced sample, especially since gender differences are highlighted in the literature. Another limitation of the study is related to the fact that this was a cross-sectional survey resorting to self-report questionnaires, and students were asked to recall their experience of a few months earlier. Thus, it is not possible to report on changes over time and the possibility of biased evaluations cannot be ruled out.

6. Study Impact

Despite its limitations, our study furthers the understanding of perceived academic stress, personal well-being, and academic engagement’s role in explaining university students’ academic performance during the first COVID-19 lockdown. It sheds light on how the pandemic’s initial wave affected university students across the three studied countries, contributing to the understanding that pandemic impacts should be considered within sociocultural contexts. This underscores the need for culturally sensitive interventions, given the varied global needs and experiences, even among culturally similar and geographically proximate countries like Portugal and Spain. Lastly, the present study sustains the importance of educational interventions targeting students’ academic success to explicitly address students’ academic engagement and not only their emotional distress regulation [

56]. The findings highlight that for students to maintain a successful relationship with their academic activity, it is not sufficient for them to feel good in their personal life, they must be engaged in their academic life. Furthermore, COVID-19 lockdown stressors identified by students represent risk factors for their engagement. Thus, the response should not solely focus on developing emotion-related coping mechanisms but should also aim to maintain and increase student engagement (with a focus on improving performance), potentially by improving assessment and lecture processes and institutional support.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Category system based on the Job Demands and Resources Model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M-P., L.C., S.N.J., I.M. and A.R.; methodology, A.M-P., L.C., S.N.J., I.M. and A.R.; formal analysis, A.M-P., L.C., M.R., and F.Q.; investigation, A.M-P., L.C., M.R., F.Q., S.N.J., I.M. and A.R.; data curation, A.M-P., L.C., and S.O.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M-P., L.C., and S.O.; writing—review of original draft, S.N.J., I.M. and A.R.; writing—review and editing, A.M-P. and S.O.; visualization, A.M-P. and S.O.; supervision, A.M-P.; project administration, A.M-P., L.C., S.N.J., I.M. and A.R.; funding acquisition, A.M-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), through the Research Center for Psychological Science of the Faculty of Psychology, University of Lisbon (CICPSI; UIDB/04527/2020 & UIDP/04527/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Scientific and Ethical Council of the Faculty of Psychology of the University of Lisbon (protocol code Ata nº 10, approved on 16/06/2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, AMP, upon reasonable request due to the informed consent agreement, which do not account for public sharing of the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- WHO - World Health Organization. WHO timeline: COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/27-04- 2020-who-timeline---covid-19 (accessed on 27 April 2020).

- Ferreras, B.; Mondelo, V.; Puga, N.; García, R.; Moreno, S.; Lidón, I. Se extiende el cierre de colegios a toda España por el coronavírus. El Mundo 2020. Available online: https://www.elmundo.es/espana/2020/03/12/5e6a2011fdddff2c1e8b4574.html (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- MCTES - Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior. Nota de Esclarecimento do Gabinete do Ministro da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior de 13 março. Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior. Available online: https://www.sec-geral.mec.pt/noticia/nota-de-esclarecimento-do-gabinete-do-ministro-da-ciencia-tecnologia-e-ensino-superior (accessed on 13 March 2020).

- UNESCO - United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Education: From school closure to recovery. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse#schoolclosures (accessed on 2021).

- Seabra, F.; Aires, L.; Teixeira, A. Transição para o ensino remoto de emergência no ensino superior em Portugal–um estudo exploratório. Dialogia 2020, (36), 316-334. [CrossRef]

- Aristovnik, A.; Keržič, D.; Ravšelj, D.; Tomaževič, N.; Umek, L. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life of higher education students: A global perspective. Sustain. 2020, 12(20), Article 8438. [CrossRef]

- Lalin, S. A. A.; Ahmed, M. N. Q.; Haq, S. M. A. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ academic performance and mental health: An overview. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2024, Article 100046.

- Marques-Pinto, A.; Curral, L.; Jesus, S.; Quadros, F. Experiências de adaptação e impactos da Covid-19 em estudantes universitários portugueses. In Processos adaptativos à COVID-19; Chambel, M. J., Ed.; Escrytos | Ed. Autor: Lisboa, Portugal, 2021; pp. 104-136.

- Odriozola-González, P.; Planchuelo-Gómez, Á.; Irurtia, M. J.; de Luis-García, R. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown among students and workers of a Spanish university. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, Article 113108. [CrossRef]

- Branquinho, C.; Guedes, F. B.; Cerqueira, A.; Marques-Pinto, A.; Branco, A.; Galvão, C.; Sousa, J.; Goulão, L. F.; Bronze, M. R.; Viegas, W.; Matos, M. G. D. COVID-19 and lockdown, as lived and felt by university students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19(20), 13454. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Planas, N. COVID-19 and college academic performance: A longitudinal analysis. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3789380 (accessed on 2021).

- Aguilera-Hermida, P. A. College students’ use and acceptance of emergency online learning due to COVID-19. International Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2020, 1, Article 100011. [CrossRef]

- Talsma, K.; Robertson, K.; Thomas, C.; Norris, K. COVID-19 beliefs, self-efficacy and academic performance in first-year university students: Cohort comparison and mediation analysis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 12, Article 2289. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, T.; de la Rubia, M. A.; Hincz, K. P.; Comas-Lopez, M.; Subirats, L.; Fort, S. Influence of Covid-19 confinement on students’ performance in higher education. PLoS One 2020, 15(10), Article e0239490. [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Pradas, S.; Hernández-García, Á.; Chaparro-Peláez, J.; Prieto, J. L. Emergency remote teaching and students’ academic performance in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 119, Article 106713. [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R. S.; Dunkel-Schetter, C.; DeLongis, A.; Gruen, R. J. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 50(5), 992-1003. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22(3), 309-328. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S. K.; Webster, R. K.; Smith, L. E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G. J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395(10227), 912-920. [CrossRef]

- Serafini, G.; Parmigiani, B.; Amerio, A.; Aguglia, A.; Sher, L.; Amore, M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa201 (accessed on 2020).

- Flores, M. A.; Barros, A.; Veiga-Simão, A. M.; Pereira, D.; Flores, P.; Fernandes, E.; Costa, L.; Ferreira, P. C. Portuguese higher education students’ adaptation to online teaching and learning in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: Personal and contextual factors. High. Educ. 2021, 83, 1389–1408. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, A.; Wu, Y.; Han, N.; Huang, H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, Article 669119. [CrossRef]

- Padrón, I.; Fraga, I.; Vieitez, L.; Montes, C.; Romero, E. A study on the psychological wound of COVID-19 in university students. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, Article 589927. [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.; Templeton, J.; Barber, B.; Stone, M. Adolescence and emerging adulthood: The critical passage ways to adulthood. In Well-being: Positive development across the life course; Bornstein, M., Davidson, L., Keyes, C., Moore, K., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, New Jersey, United States of America, 2003; pp. 383-406.

- Gallagher, K. M.; Jones, T. R.; Landrosh, N. V.; Abraham, S. P.; Gillum, D. R. College students’ perceptions of stress and coping mechanisms. J. Educ. Dev. 2019, 3(2), 25-34. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C. S.; Ho, R. C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. nt. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17(5), Article 1729. [CrossRef]

- Graham, M. A.; Eloff, I. Comparing mental health, wellbeing and flourishing in undergraduate students pre-and during the COVID-19 pandemic. nt. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19(12), 7438. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. E.; Stanton, A. L. Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 3, 377–401. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Lucock, M. The mental health of university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: An online survey in the UK. PLoS One 2022, 17(1), Article e0262562. [CrossRef]

- Prasath, P. R.; Mather, P. C.; Bhat, C. S.; James, J. K. University student well-being during COVID-19: The role of psychological capital and coping strategies. Prof. Couns. 2021, 11(1), 46-60. [CrossRef]

- Araque-Castellanos, F.; González-Gutiérrez, O.; López-Jaimes, R. J.; Nuván-Hurtado, I. L.; Medina-Ortiz, O. Bienestar psicológico y características sociodemográficas en estudiantes universitarios durante la cuarentena por SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19). Arch. Venez. Farmacol. Ter. 2020, 39(8), 998-1004. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, I.; Youssef-Morgan, C.; Chambel, M. J.; Marques-Pinto, A. Antecedents of academic performance of university students: Academic engagement and psychological capital. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 39(8), 1047-1067. [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Llorens, S.; Cifre, E.; Martınez, I. M.; Schaufeli, W. Perceived collective efficacy, subjetive well-being and task performance among electronic groups. Small Group Res. 2003, 34, 43–73. [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B.; Martínez, I. M.; Marques-Pinto, A.; Salanova, M.; Bakker, A. Burnout and engagement in university students. A cross-national study. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2002, 33, 464–481. [CrossRef]

- Peña, K. L.; Bustos-Navarrete, C.; Cobo-Rendón, R.; Fernández Branada, C.; Bruna Jofré, C.; Maldonado Trapp, A. Professors’ expectations about online education and its relationship with characteristics of university entrance and students’ academic performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, Article 642391. [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Schaufeli, W.; Martínez, I.; Bresó, E. How obstacles and facilitators predict academic performance: The mediating role of study burnout and engagement. Anxiety Stress Coping 2010, 23(1), 53–70. [CrossRef]

- Figueira, C.; Marques Pinto, A.; Pereira, C.; Roberto, M. S. How can academic context variables contribute to the personal well-being of higher education students? Span. J. Psychol. 2017, 20, E43. [CrossRef]

- Marzoli, I.; Colantonio, A.; Fazio, C.; Giliberti, M.; di Uccio, U. S.; Testa, I. Effects of emergency remote instruction during the COVID-19 pandemic on university physics students in Italy. Phys. Rev. Phys. Educ. Res. 2021, 17(2), Article 020130. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A. F. T. O impacto do bem-estar dos estudantes do ensino superior no envolvimento académico. Master Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, 2021.

- Daniels, L. M.; Goegan, L. D.; Parker, P. C. The impact of COVID-19 triggered changes to instruction and assessment on university students’ self-reported motivation, engagement and perceptions. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 24(1), 299-318. [CrossRef]

- Ștefenel, D.; Neagoș, I. Measuring academic engagement among university students in Romania during COVID-19 pandemic. Thesis 2020, 9(2), 3-29. https://hrcak.srce.hr/250869.

- Aust, F.; Diedenhofen, B.; Ullrich, S.; Musch, J. Seriousness checks are useful to improve data validity in online research. Behav. Res. Methods 2013 45(2), 527-535. [CrossRef]

- Dewitt, J.; Capistrant, B.; Kohli, N.; Rosser, B. S.; Mitteldorf, D.; Merengwa, E.; West, W. Addressing participant validity in a small internet health survey (The Restore Study): Protocol and recommendations for survey response validation. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2018, 7(4), Article e96. [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.B. Controlling social desirability bias. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 61(5), 534-547. [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. M.; Wissing, M.; Potgieter, J. P.; Temane, M.; Kruger, A.; van Rooy, S. Evaluation of the Mental Health Continuum Short Form (MHC-SF) in Setswana speaking 15/24 South Africans. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2008, 15(3), 181–192. [CrossRef]

- Cadime, I.; Pinto, A. M.; Lima, S.; Rego, S.; Pereira, J.; Ribeiro, I. Well-being and academic achievement in secondary school pupils: The unique effects of burnout and engagement. J. Adolesc. 2016, 53, 169-179. [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B.; Bakker, A. B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66(4), 701-716. [CrossRef]

- Bardin, L. The content analysis. PUF: Paris, França, 1977.

- Brown, T. W. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. The Guilford Press: New York, United States of America, 2006.

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C. Psychometric methods. McGraw-Hill: New York, United States of America, 1978.

- Hayes, A. F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd edition). The Guilford Press: New York, United States of America, 2017.

- Hayes, A. F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, A. C. S.; Magnan, E. D. S.; Pacico, J. C.; Hutz, C. S.; Schaufeli, W. B. Adaptação e validação da versão brasileira da Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Psico-USF 2015, 20, 207-217. [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C.; Fraccaroli, F.; Schaufeli, W. B. Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9). Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 26(2), 143-149. [CrossRef]

- Westerhof, G. J.; Keyes, C. L. Mental illness and mental health: The two continua model across the lifespan. J. Adult Dev. 2010, 17, 110-119. [CrossRef]

- Chiodelli, R.; Jesus, S. N.; Mello, L. T. N.; Andretta, I.; Oliveira, D.; Costa, M; Rusell, T. Effects of the Interculturality and Mindfulness Program (PIM) in university students: A quasi-experimental study. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2022, 12(10), 1500-1515. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).