1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic developed an unprecedented crisis (Luchetti et al., 2020) and caused a deep impact on people’s health (Bogolyubova, et al., 2021; Cheng et al., 2020). The numerous measures issued by different countries as “stay-at-home” or “shelter-in-place” orders to contain and prevent the spread of COVID-19 infection have encouraged the emergence of various negative outcomes on people. Furthermore, these adverse effects have been causally linked to increasing psychological distress such as anxiety, stress, or depression (Daly & Robinson, 2021; Zhang et al., 2020) diminshing their levels of well-being (Blasco-Belled, et al., 2020; Bogolyubova, et al., 2021; Chi et al., 2021). All extreme events, including COVID-19, have a direct influence on social factors, the economy, and mental health. The world population was severely affected, among them the university students. The impact of COVID-19 and the fast spread forced universities to implement several actions to preserve students' health, such as changing all the courses, grades, and masters from face-to-face to online delivery mode. Notwithstanding all these strategies to safeguard students’ health, the ongoing adjustments and the current state of uncertainty generated a significant increase in the students’ perceptions of anxiety and a decline in their subjective well-being due to the fluctuation brought on by the COVID-19 outbreak (Sahu, 2020). A large body of literature exists on the psychological effects of COVID-19 on students (Dhar et al., 2020, Laranjeira, et al., 2021, Maia & Dias, 2020, Sahu, 2020, Sood & Sharma, 2020), however, there has been little empirical research on the impact of COVID-19 over subjective well-being which consider the resilience of students as a protective factor during the pandemic. To determine this, the current study examined the impact of COVID-19 (financial, psychological and educational) over psychological distress (anxiety and perceived stress) and subjective well-being among university students, taking the role of resilience into account as a protective factor.

1.1. COVID-19 and Its Impact on Subjective Well-Being

The COVID-19 outbreak is a threat to mental and physical health, the unknown virus was highly infectious, and its fast global spread had a profound impact on university students’ lives (Bell et al., 2020). All the preventive measures with varying extents that were established globally to prevent the spread of the virus (Luchetti, et al., 2020) and the adverse effects that people experienced due to the drastic changes caused in their lives (changes in their routines, keeping safe distances, wearing a mask, closing educational and public centres, confinement at home, unemployment, etc.), had a negative impact on the levels of well-being on the university students, on their mental health, increased financial insecurity and a continued uncertainty in academic pursuits (Author., 2020; Bell et al., 2020; Bogolyubova, et al., 2021; Chi et al., 2021). Recently, the quantity of publications about the impact of COVID-19 over mental health, psychological distress increased dramatically. However, the existence of scientific evidence related to the impact of the different psychological, academic and financial consequences of COVID-19 over students’ subjective well-being and the role of resilience is limited.

According to Daly and Robinson (2021), there are multiple factors that might lead to poor mental health during the COVID-19 outbreak, including future uncertainty, the abrupt implementation of online learning and a decline in social interaction. Researchers showed how anxiety and perceived stress have increased during the pandemic, particularly among university students causing substantial implications on subjective well-being (AlAteeq et al., 2020; Aslan et al., 2021; Garbóczy et al., 2021; Huang & Zhang, 2021; Pedrozo-Pupo et al., 2020; Sheroun et al., 2020; Wang & Zhao, 2020; Yan et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2021).

According to Sahu (2020), the closure of universities resulted in a number of issues that had to be addressed, including online classes, the influence of assessment and evaluations that had to evolve and adapt to the online mode, and mental health. The latter was associated with a sense of hopelessness and anxiety due to a lack of knowledge and unpredictability, which significantly elevated stress levels among university students. Kokkinos et al., (2022) and Frazier et al., (2019) suggest that the distress generated by COVID-19 reduced academic performance. But the pandemic not only affected academic performance, also financial stress and life stability deteriorated during that time. Some scholars (Kokkinos et al., 2022; Rogowska et al., 2020; Sood & Sharma, 2020) suggested that the factors that can affect students’ life satisfaction due to the pandemic were the difficulties over the finances and the insecurity during hardships (aggravated by the loss of jobs of a relative, and by the reduction of salary), and the reduced academic performance affected by the prolonged lockdowns and the restrictive measures.

The COVID-19 pandemic is perceived by people as a stressful situation. One understands stress as an individual’s adaptation response to internal or external threats (Liu et al., 2021). Perceived stress is a global subjective evaluation, and this is the result of a person's appraisal of a stressor as threatening or non-threatening, as well as one's own abilities to cope (Yan et al., 2021). According to Zhao et al. (2021) anxiety appears when one’s life is appraised as threatening or stressful. The literature shows after exposure to stressful events (such as pandemic occurrences), anxiety levels increase. Scholars have demonstrated that there is a link between perceived stress and anxiety. When anxiety levels increase this is associated with high levels of perceived stress. Conversely, stress and anxiety are inversely related with well-being (Arlsan & Allen, 2021). An individual's mental health can be successfully improved through subjective well-being (SWB) (Geng, 2018). SWB is considered as a person's appraisal of their life from a cognitive and affective standpoint (Diener et al., 2002). The cognitive component is determined by an overall evaluation of the person's life, and the affective component is determined by the person's pleasant emotional experiences (positive affect), which is also referred to as happiness (Blasco et al., 2019; Diener et al., 2003; Diener et al., 2012; Diener et al., 2017; Szczygiel & Mikolajczak; 2017). Based on this conceptualisation and according to Szczygiel and Mikolajczak (2017) satisfaction with life (cognitive component) and subjective happiness (affective component) are the components most used to evaluate SWB. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic had negative consequences on SWB (Kokkinos et al., 2022; Sood and Sharma, 2020; Tan et al., 2020).

Similarly, some scholars (Kokkinos et al., 2022; Sood and Sharma, 2020; Tan et al., 2020) explore the psychological, academic and financial consequences of COVID-19 over students’ life satisfaction (the cognitive component of SWB) and have found significant associations with them. Although this kind of situation is almost invariably connected to traumatic experiences and psychological distress, which impact subjective well-being, it can also present possibilities for constructive development or for putting coping mechanisms into practice such as resilience (Yu et al., 2021).

1.2. Resilience as Mediator

Resilience is defined as one’s ability to recover from difficult, negative or traumatic life events, and the capacity to adapt to unfavourable circumstances (Ryff & Singer, 2003; Smith et al., 2008, Yaldirim & Arlsan, 2020). It is considered a protector against all these difficult and traumatic situations or challenging times and preserves mental health and well-being, it also enables people to remain strong during these circumstances (Ogińska-Bulik and Zadworna-Cieślak, 2018; Satici et al., 2020; Yaldirim & Arlsan, 2020; Yu et al., 2022; Yuan et al., 2018). During COVID-19 pandemic, scholars revealed that people with more resilience experience less anxiety and stress, and it was considered a resource which allowed people cope with fear, unknown situations, anxiety and stress resulting from the pandemic lockdown and unpredictable scenarios (Ran et al., 2020; Satici et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020).

Furthermore, Kong et al., (2020), reinforce the idea of multiple studies in which resilience could be considered as a mediator. Scholars suggest that resilience is an important factor in increasing the levels of SWB (Kong et al., 2018; Kong et al., 2020; Wang and Kong 2020). However, to our knowledge, there are some studies that analyse the role of SWB during COVID-19 (Wang et al., 2021) as well as the role of SWB and resilience during COVID-19 (Kimhi et al., 2021; Metin et al., 2021) no research has directly examined the mediating role of resilience in the impact of COVID-19, psychological distress (perceived stress and anxiety) and SWB.

In the current study, we consider three different countries, Andorra, Mexico and Spain, in each of these contexts, similar multiple measures were put in place to manage and prevent the spread of the virus, which causes and amplifies the levels of anxiety and stress (Alzueta et al., 2020; Kowal et al., 2020; Moret-Tatay, 2021). This comparison can facilitate the comprehension of the relationship between the impact of COVID-19, resilience, psychological distress and SWB, and may improve our understanding of earlier studies.

1.3. The Current Study

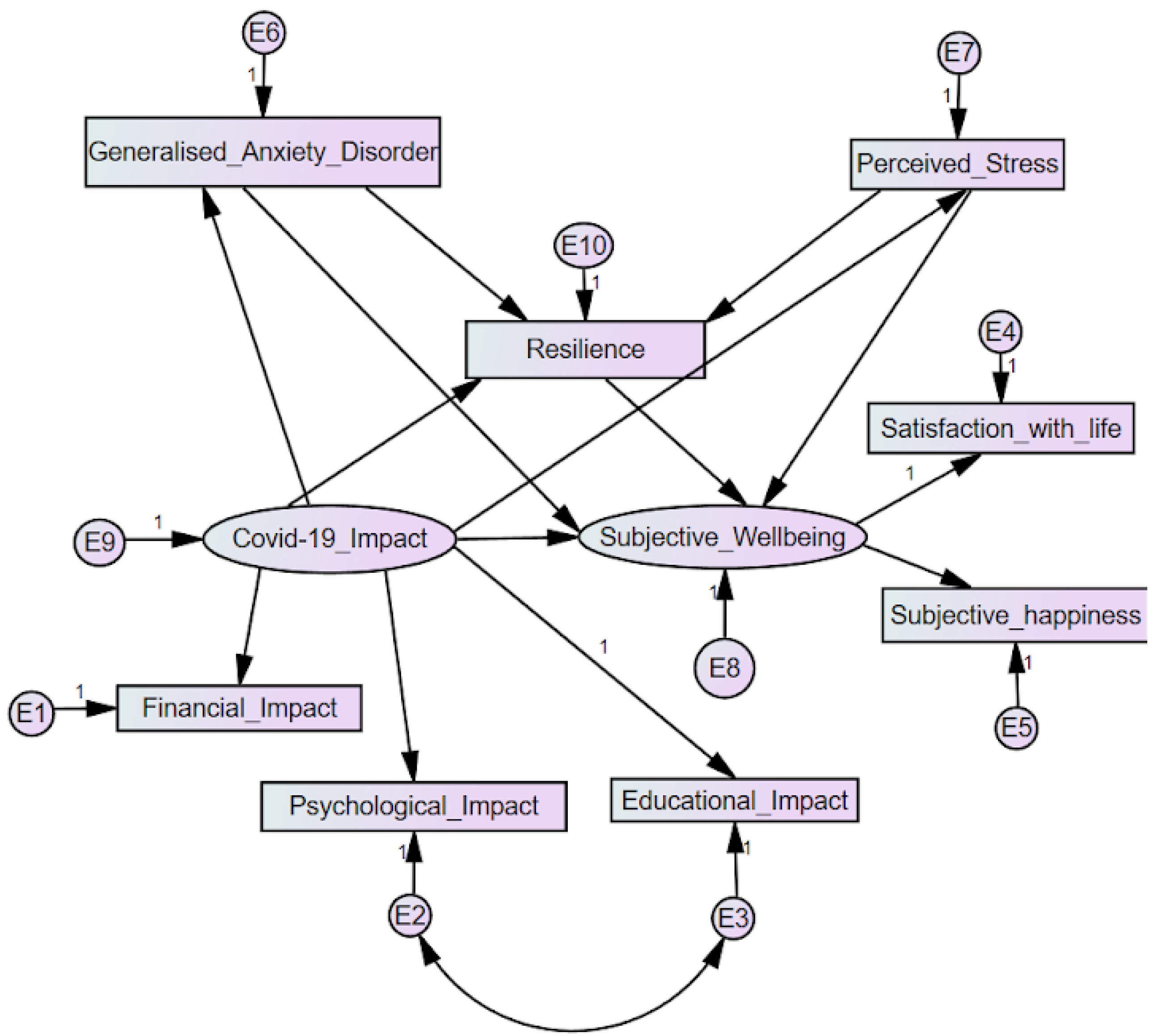

This study seeks to assess the role of student resilience in reducing perceived anxiety and stress brought on by the COVID-19 impact in order to maintain or improve students' subjective well-being. It also sought to explore the influence of COVID-19 impact on students' subjective well-being using students' perceived anxiety and stress as mediators. In order to achieve this, we developed a model to be tested based on the literature and previous empirical studies (see

Figure 1), which includes three hypotheses: (H1) Resilience has a mediating role between the students’ impact of COVID-19 and the anxiety and stress caused by it on students’ subjective well-being. (H2) Resilience has a significant positive effect on SWB. (H3) The measurement weights of the model remain invariant among the three contexts analysed (Andorran, Mexican and Spanish).

2. Materials and Methods

This study was based on a quantitative methodology using a non-experimental and transversal design, in which we applied an online questionnaire to university students of three different contexts in order to gather the greatest amount of information from across different institutions.

2.1. Participants and Procedure

A total of 685 university students (79% female) aged 17–66 years (M = 21.97; SD = 4.72) from different countries (8% Andorra, 48% Mexico, 44% Spain) completed anonymous self-reported questionnaires. We used a non-probabilistic convenience sampling technique. The participants enrolled voluntarily, and they could withdraw from the study at any time without further explanation; no partial responses were collected. The mean time spent completing the survey was 7 minutes. No missing observations were registered because responses were collected online, and each question was mandatory. To maintain the pandemic event's backdrop as consistently as possible, the administration period spanned from early November 2020 to March 2021.

2.2. Measures

The scale adaptation process was conducted according to previously established guidelines of the International Test Commission. The English version was translated into Catalan and Spanish language independently by two Spanish and Catalan native translators. The obtained translations were discussed among a group of experts to achieve the first version of the scale. The first version scale was translated back to English by another native English two translator without prior knowledge of the original version. The translations and back translations were discussed in a second consensus panel to achieve the final version.

The Coronavirus Impact Questionnaire (Conway et al., 2020) is configured by three subscales (Financial Scale, Resource Scale and Psychological Scale) with three-item each scale (one reversed by each scale), and Educational Impact which is configured by 10 items distributed in three subscales (Learning Behaviours, Academic Performance, and School Satisfaction and Motivation). In this research we used the psychological, financial and educational impact scale. Participants rate the psychological impact of COVID-19 on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not true of me at all to 7 = very true of me). The internal consistency for each subscale was acceptable. A sample item is I have become depressed because of the Coronavirus (COVID-19). The internal consistency in the Financial Scale was α = .87; in the Educational Impact was α = .84; and in the Psychological Scale was α =.84.

The Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7; Spitzer et al. 2006; Spanish version García-Campayo et al., 2010) is a seven-item, self-report anxiety questionnaire (0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day). The items enquire about the degree to which the patient has been bothered by feeling nervous or anxious, not being able to stop or control worrying, having trouble relaxing, worrying too much about different things, being so restless that it is hard to sit still, becoming easily annoyed and feeling afraid as if something might happen, in the last 2 weeks. The internal consistency was α = .91. A sample item is, Feeling afraid as if something awful might happen.

The Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., 1983; Spanish version Remor, 2006) is a ten-item self-report that evaluates the global perceptions of stress during the last month. These items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 = never, to 4 = very often. The scale is scored by reverse coding the positive items and summing all the responses. The scale showed internal consistency α = .90. A sample item is, (“In the past month, how often have you felt upset because something unexpected occurred?”).

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Sem, & Griffin, 1985; Spanish version by Vázquez, Duque, & Hervás, 2013) is a five-item questionnaire that evaluates the degree of satisfaction with life as a whole. Participants are asked to rate their satisfaction with life on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). The reliability estimate was good α = .85. A sample item is, So far I have gotten the important things I want in life.

The Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS; Lyubomirsky & Lepper, 1999; Spanish version by Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2014) is a four-item (one reversed) survey in which participants rate the extent to which they are in accordance with happiness statements on a 7-point Likert scale, considering the definition of happiness from the respondent’s perspective. The internal consistency was acceptable for adults (α = .81). A sample item is, Compared with most of my peers, I consider myself….

Psychological Resilience (CD-RISC-10; Connor y Davidson, 2003, Spanish version by Notorio-Pacheco et al. 2011). A self-administered questionnaire of 10 items designed as a Likert type additive scale with five response options (0 = never; 4 = almost always), which had a single dimension in the original version. The internal consistency was acceptable for adults (α = .85). A sample item is I can deal with whatever comes.

2.3. Data Analysis

Data screening showed no missing data. Univariate analyses indicated the non-normality of the data and tests were applied according to this situation. First of all, we analysed the reliability of the scales to ensure that internal consistency of the different scales applied were maintained with the new data; we used Cronbach’s alpha as a coefficient. Second of all, we conducted the Structural Equation Model (SEM) based on the aims of the study and the hypothesised model; the SEM intended to confirm the structure of the theoretical model as well as the causal relations among the factors. This analysis allowed us to test the H1. To analyse the goodness-of-fit of the model, we used the indexes and cut-offs recommended by Byrne (2016) such as: CMIN/DF (<3), RMR (=<.05), CFI (>.95), NFI (.95), RMSEA (<.50). Because the data was asymmetric, the estimated method used was the Asymptotically Distribution-Free (ADF) technique (Huang & Bentler, 2015). Once we selected the best model, we tested the invariance of the model based on the origin of the data (Andorran, Catalan and Mexican) using a multigroup analysis approach of the dataset, testing H2. We adjusted the measurement weights of the models and analysed the nested model comparison as well as compared the goodness-of-fit indexes for both models. To ensure the invariance of the model, the fit between the unconstrained model and the constrained one, should not differ significantly.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

Descriptive statistics of the scales applied are shown in

Table 1. Once we confirmed that the data were asymmetrically distributed, we started by testing the hypothesised model presented in

Figure 1 using adequate analyses of the data.

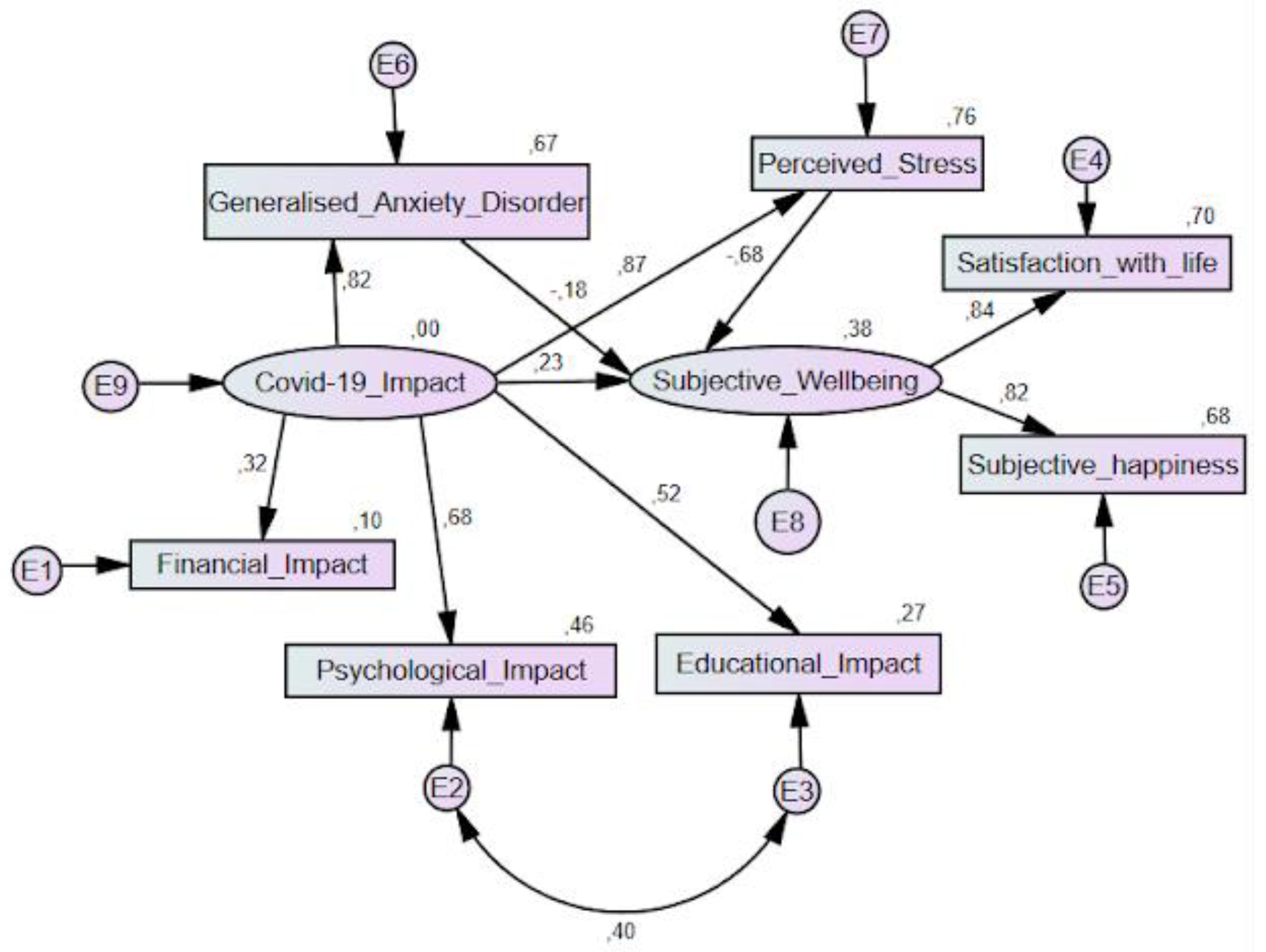

In order to respond to our aim, we did not include the factor resilience in our first model (model A). Model A included 7 observed variables and 11 unobserved variables; the latter ones included two latent factors that grouped the scales associated with the COVID-19 impact (financial, psychological, and educational impact) and the Subjective Well-being (satisfaction with life and subjective happiness), as well as the errors associated with all of the variables. The model fit showed good values: CMIN of 2.718, RMR of .056, CFI and NFI (.974 and .960 respectively) and RMSEA (.050; IC 95% [.025 - .073]). These results pointed out that the model fits the data in representing the relations among COVID-19 impact on students’ subjective well-being using students’ perceived anxiety and stress as mediators. Modification indices suggested correlating the errors of the different observed variables, however, based on the par change values, the goodness-of-fit values, and the lack of theoretical support, we decided to maintain the model as it emerged.

Table 2 presents regression weights and

Table 3 shows direct and indirect effects among the variables.

Figure 2 presents Model A with the standardised values.

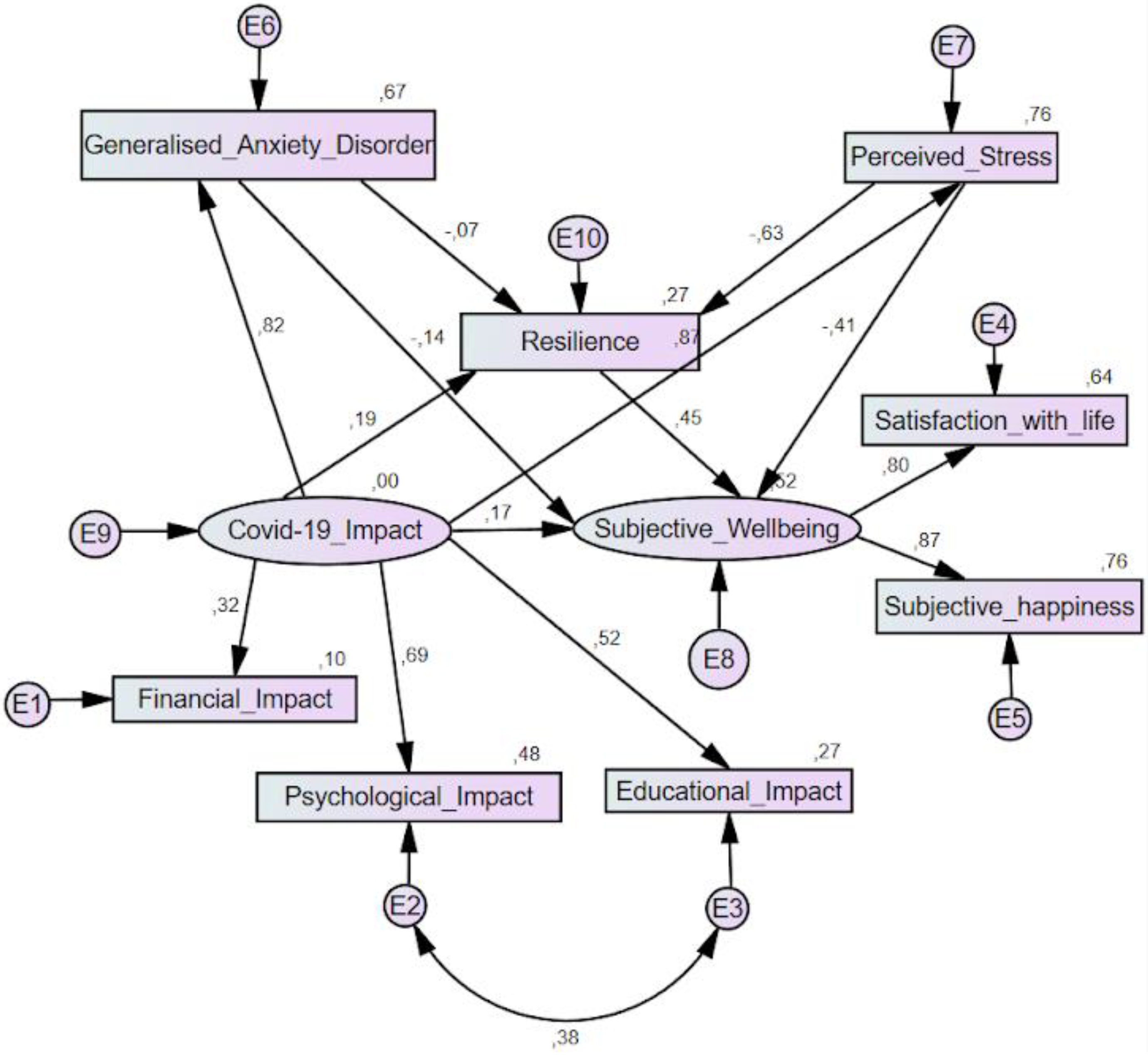

Nonetheless, and because our aim was also to test the role of Resilience in this model, we explored a second model (Model B) to include Resilience as a mediator between COVID-19 impact, the perceived anxiety, stress and their impact on students’ subjective well-being. Model B also helped us to test our first hypothesis: (H1) Resilience has a mediating role between the students’ impact of COVID-19 and the anxiety and stress caused by it on students’ subjective well-being. Model B included 8 observed variables and 12 unobserved variables. The results pointed out that the model fit with good values the data in representing the relations among COVID-19 impact on students’ subjective well-being: CMIN of 2.963, RMR of .057, CFI and NFI (.965 and .949 respectively) and RMSEA (.054; IC 95% [.034 - .074]). Despite modification indices suggested, again, correlating the errors of the different observed variables but we decided, based on the par change values, the goodness-of-fit values and the lack of theoretical support, to maintain the model as it emerged.

Table 4 presents regression weights and

Table 5 shows direct and indirect effects among the variables.

With the direct and indirect effects, we observe that resilience reduces the negative impact of COVID-19 on Subjective Well-being, as well as mediates the relation between students’ perceived anxiety and stress and students’ subjective well-being. This indicates that the more resilient a college student is, the more capable to deal with the negative impact caused by COVID-19 on their subjective well-being as well as reducing their perceived anxiety and stress caused by the situation. Results confirm our first hypothesis (H1) in which resilience has a mediator role between the students’ impact of COVID-19, anxiety and stress caused by it on students’ subjective well-being.

Figure 3 presents Model B with the standardised values.

To conclude, we tested our second hypothesis: (H2) the measurement weights of the model remain invariant among the three contexts analysed (Andorran, Mexican and Spanish). This hypothesis intended to cross-validate model B among the three contexts in which we collected data. To do so, we tested the invariance of Model B.

Table 6 provides the model fit summary of the unconstrained model (free distribution of the weights) and the model in which we constrain the measurement weights (the one we want to test). Results suggest that the model fit remains adequate, and it even improves in most of the indices.

We also reviewed the nested model comparison assuming that the model unconstrained is correct (see

Table 7), and we obtained that the CMIN change is non-significant (p = .321). With this information we can conclude that Model B remains stable across the three contexts when we constrain it by measurement weights, which allow us to accept our second hypothesis (H2); thus, Model B can be generalised to other contexts.

4. Discussion

The findings of the present study provide empirical research about the impact of COVID-19 on subjective well-being and consider the resilience of students as a protective factor during the pandemic. Moreover, our results are consistent with recent studies about the negative impact COVID-19 has had on different spheres of college students' lives around the world (Alzueta et al. 2020; Kokkinos et al., 2022; Rogowska et al., 2020; Sood & Sharma, 2020). Alzueta et al. (2020) examined the effects of COVD-19 on mental health on the general population and demonstrated how anxiety and stress increased during this period. More specifically, Rogowska et al. (2020) examined university students’ levels of anxiety, stress, and life satisfaction, and demonstrated how this has severely influenced their psychological distress. Additionally, Li et al. (2020) showed that levels of anxiety, stress, and poor mental health increased during the pandemic occurrences; Son et al. (2020), demonstrated that anxiety and stress were emotional threats to college students, and also showed the negative impact of COVID-19 on academic performance (one of them was the transition to online classes). The different studies conducted during COVID-19 show that college students were considered particularly vulnerable to mental health concerns.

Therefore, the insights suggest that depression and anxiety symptoms were typical psychological responses in all global regions during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (Lima et al., 2020; Rajkumar, 2020). Mainly how this has affected SWB (Kokkinos et al., 2022; Sood and Sharma, 2020; Tan et al., 2020). Increased levels of uncertainty, anxiety, and stress in response to the drastic change in adult students' lives (Blasco-Belled et al., 2020; Bell et al., 2020; Bogolyubova, et al., 2021; Chi et al., 2021; Kokkinos et al., 2022; Sahu, 2020; Sood & Sharma, 2020; Tan et al., 2020) has generated students' perceived lower SWB (Arlsan & Allen, 2021; Blasco-Belled, et al., 2020; Bogolyubova, et al., 2021; Chi et al., 2021). In addition, our research adds more evidence to the line of research on well-being by showing that in a crisis context it is essential to consider such characteristics as resilience to recover from difficult, negative, or traumatic life events, and the ability to adapt to unfavourable circumstances (Ryff & Singer, 2003; Smith et al, 2008, Yaldirim & Arlsan, 2020; Ogińska-Bulik & Zadworna-Cieślak, 2018; Satici et al., 2020; Yaldirim & Arlsan, 2020; Yu et al., 2022; Yuan et al., 2018).

As expected, the results of the present study support the hypothesis that resilience has a mediating effect on the impact of COVID-19 and the anxiety and stress it causes on students' subjective well-being. Thus, college students who are more resilient, are better equipped to cope with the negative impact caused by COVID-19 on their subjective well-being as well as to reduce their perceived anxiety and stress caused by the situation (Ogińska-Bulik & Zadworna-Cieślak, 2018; Satici et al., 2020; Yaldirim & Arlsan, 2020; Yu et al., 2022; Yuan et al., 2018).These findings are consistent with recent research by Quintiliani et al. (2022), who discovered that resilience enables university students safeguard their mental health. Along the same lines, Valladolid (2021) found that resilience maintains the well-being of college students, and Labrague (2021) reinforced the importance of building resilience in students in order to sustain their mental health and increase their level of life satisfaction. Moreover, these findings allow us to understand the role of resilience, and its potential to operate as a protective factor. On a similar note, a resilient individual is able to handle a variety of challenging situations. Resilience helps people respond to various psychological difficulties. Additional research studies suggest that resilience combined with other psychological resources including humor, gratitude, optimism, and mindfulness may reduce psychological distress (Bono et al., 2020; Hamadeh et al., 2021; Vos et al., 2021). Given these results, it is important to strengthen the various positive psychological resources since they can lessen the impact of psychological discomfort. As a result, it is crucial to develop interventions or training programs to aid students in developing these positive psychological resources, such as resilience, because doing so enables them to regulate their emotions and management strategies in challenging situations in the future.

Finally, previous research on the impact of multiple measures to control and prevent the spread of COVID-19 show that although these measures were applied in different cultural contexts, both the increased anxiety and stress and the decrease in well-being were at similar levels (Alzueta et al., 2020; Kowal et al., 2020; Moret-Tatay, 2021). We found that the model that includes the mediating effect of resilience in the impact of COVID-19, anxiety, and stress on SWB remains invariant among the three contexts analysed (Andorran, Mexican and Spanish). In the literature with cross-cultural approaches, resilience is usually understood as the opposite of vulnerability (Panter-Brick, 2015). Therefore, resilience might be viewed as an interconnected, globally protective factor for mental health, independent of a country's cultural, social, and geographic context.

4.1. Limitations and Future Avenues

Despite the strengths (eg. cross-cultural study and multivariate methodology), some limitations are that for this study we used a non-probabilistic sample, and the data were collected with self-report instruments. Thus, some bias might occur, particularly in generalising results to local adult populations. Nevertheless, a larger sample size and the inclusion of data from multiple sources in subsequent studies would be advantageous and allow for the generalisation of the findings regarding the effect of COVID and the role of resilience in well-being.

Comparing psychological symptoms across different cultures and countries presents complex challenges (Moret-Tatay, & Murphy, 2022; Van Bavel et al., 2020), and therefore these findings should be interpreted with caution. The outbreak has evolved rapidly and asynchronously across countries. Furthermore, past research has found that the severity of mental disorders is related to long periods of isolation and situations of uncertainty (Allegrante et al., 2020; Carvalho et al., 2020; Haider et al., 2020). To further our research and examine the effect of COVID-19 on well-being at various stages, we advise future studies to employ a longitudinal approach. Future research may also take into account additional elements that serve as well-being shields, such as social support, coping mechanisms, anxiety management, and other cognitive resources.

Finally, given the positive effects of resilience that the findings of this study, it might be interesting for future research lines to examine whether or not students' perceptions of the impact of COVID on their well-being are improved by participating in an intervention program to increase resilience and coping mechanisms. Even expand it to additional groups like professionals from other sectors or students from various age groups.

5. Conclusions

The main conclusions can be presented as follows: a) Significative relations among COVID-19 impact in students’ subjective well-being using students’ perceived anxiety and stress as mediators. B) Resilience has a mediating role between the students’ impact of COVID-19 and the anxiety and stress caused by it on students’ subjective well-being (H1) and c) this model is stable across three contexts (H2), therefore the model has the capacity to be generalised to other contexts.

These findings potentially add to thorough and fundamental explanations of well-being in pandemic contexts. And this provides a chance to learn new things about how we respond emotionally to stressful situations, how we perceive our well-being in them, and how we adjust to difficult situations. Regarding the practical contribution, it may be helpful to design more efficient and practical measures to improve students' well-being by taking into account resilience's mediating function. These findings can also assist educators and mental health professionals in better supporting and guiding students' learning throughout COVID-19.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, C.T.N., A.S and B.S.B.; methodology, C.T.N and C.Q.P.; formal analysis, C.T.N and C.Q.P.; investigation, C.T.N and C.Q.P.; project administration, C.T.N.; resources, C.T.N, A.S., B.S.B, and C.Q.P.; data curation, C.Q.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.T.N, C.Q.P; P.E.R.G; and S.A..; writing—review and editing, C.T.N, C.Q.P; P.E.R.G; and S.A., supervision, C.T.N and C.Q.P.;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the GRIE research group of University of Andorra for their help and assistance in the creation of the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- AlAteeq, D. A., Aljhani, S., & AlEesa, D. (2020). Perceived stress among students in virtual classrooms during the COVID-19 outbreak in KSA. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 15(5), 398-403. [CrossRef]

- Allegrante, J. P., Auld, M. E., & Natarajan, S. (2020). Preventing COVID-19 and its sequela: “There is no magic bullet... It's just behaviors”. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 59(2), 288−292. [CrossRef]

- Alzueta, E., Perrin, P., Baker, F. C., Caffarra, S., Ramos-Usuga, D., Yuksel, D., & Arango-Lasprilla, J. C. (2020). How the COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives: A study of psychological correlates across 59 countries. Journal of clinical psychology, 77(3), 556-570. [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G., & Allen, K. A. (2021). Exploring the association between coronavirus stress, meaning in life, psychological flexibility, and subjective well-being. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 27(4), 803-814. [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, R. P., Collaborators, W. W.-I., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., Demyttenaere, K., Ebert, D. D., Green, J. G., Hasking, P., Murray, E., Nock, M. K., Pinder-Amaker, S., Sampson, N. A., Stein, D. J., Vilagut, G., Zaslavsky, A. M., Kessler, R. C., & WHO WMH-ICS Collaborators. (2018). WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(7), 623–638. [CrossRef]

- Blasco-Belled, A., Tejada-Gallardo, C., Torrelles-Nadal, C., & Alsinet, C. (2020). The costs of the COVID-19 on subjective well-being: An analysis of the outbreak in Spain. Sustainability, 12(15), 6243. [CrossRef]

- Bell, D. J., Self, M. M., Davis, C. III, Conway, F., Washburn, J. J., & Crepeau-Hobson, F. (2020). Health service psychology education and training in the time of COVID-19: Challenges and opportunities. American Psychologist, 75(7), 919–932. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. (2016). Structural equation modeling with Amos: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

- Bogolyubova, O., Fernandez, A. S. M., Lopez, B. T., & Portelli, P. (2021). Traumatic Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in an International Sample: Contribution of Fatalism to Psychological Distress and Behavior Change. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 5(2), 100219. [CrossRef]

- Bono, G., Reil, K., & Hescox, J. (2020). Stress and wellbeing in urban college students in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic: Can grit and gratitude help?. International Journal of Wellbeing, 10(3), 39-57. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, P., Moreira, M. M., de Oliveira, M., Landim, J., & Neto, M. (2020). The psychiatric impact of the novel coronavirus outbreak. Psychiatry Research, 286, 112902. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T. C., Kim, S., & Koh, K., (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on Subjective Well-Being: Evidence from Singapore. IZA Discussion Paper No. 13702. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3695403.

- Chi, X., Liang, K., Chen, S. T., Huang, Q., Huang, L., Yu, Q., ... & Zou, L. (2020). Mental health problems among Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19: The importance of nutrition and physical activity. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 100218. [CrossRef]

- Conway, L. G., III, Woodard, S. R., & Zubrod, A. (2020, April 7). Social Psychological Measurements of COVID-19: Coronavirus Perceived Threat, Government Response, Impacts, and Experiences Questionnaires. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2002). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and life satisfaction. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of Positive Psychology (pp. 463–473). Oxford University Press.

- Dhar, B. K., Ayittey, F. K., & Sarkar, S. M. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on psychology among the university students. Global Challenges, 4(11). [CrossRef]

- Garbóczy, S., Szemán-Nagy, A., Ahmad, M.S. et al. (2021) Health anxiety, perceived stress, and coping styles in the shadow of the COVID-19. BMC Psychol 9, 53. [CrossRef]

- Haider, I., Tiwana, F., & Tahir, S. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adult mental health. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 36 (COVID19-S4: COVID-19 Supplement 2020), 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. & Bentler, P.M. (2015) Behavior of Asymptotically Distribution Free Test Statistics in Covariance Versus Correlation Structure Analysis, Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 22(4), 489-503. [CrossRef]

- International Test Commission. (2017). The ITC Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests (Second edition). www.InTestCom.org.

- Kachanoff, F., Bigman, Y., Kapsaskis, K., & Gray, K. (2020, April 2). Measuring realistic and symbolic threats of COVID-19 and their unique impacts on wellbeing and adherence to public health behaviors. [CrossRef]

- Kimhi, S., Eshel, Y., Marciano, H., & Adini, B. (2020). A renewed outbreak of the COVID− 19 pandemic: A longitudinal study of distress, resilience, and subjective well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 7743. [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, C. M., Tsouloupas, C. N., & Voulgaridou, I. (2022). The effects of perceived psychological, educational, and financial impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Greek university students’ satisfaction with life through Mental Health. Journal of affective disorders, 300, 289-295. [CrossRef]

- Kong, F., Ma, X., You, X., & Xiang, Y. (2018). The resilient brain: psychological resilience mediates the effect of amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations in orbitofrontal cortex on subjective well-being in young healthy adults. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 13(7), 755–763. [CrossRef]

- Kong, F., Yang, K., Yan, W., & Li, X. (2021). How does trait gratitude relate to subjective well-being in Chinese adolescents? The mediating role of resilience and social support. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(4), 1611-1622. [CrossRef]

- Kowal, M., Coll-Martín, T., Ikizer, G., Rasmussen, J., Eichel, K., Studzińska, A., ... & Ahmed, O. (2020). Who is the most stressed during the COVID-19 pandemic? Data from 26 countries and areas. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 12(4), 946-966. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Lv, S., Liu, L., Chen, R., Chen, J., Liang, S., Tang, S., & Zhao, J. (2020). COVID-19 in Guangdong: immediate perceptions and psychological impact on 304,167 college students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L. J. (2021). Resilience as a mediator in the relationship between stress-associated with the Covid-19 pandemic, life satisfaction, and psychological well-being in student nurses: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Education in Practice, 56, 103182. [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira C, Querido A, Marques G, et al. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic and its psychological impact among healthy Portuguese and Spanish nursing students. Health Psychology Research, 9(1), 24508. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Lithopoulos, A., Zhang, C. Q., Garcia-Barrera, M. A., & Rhodes, R. E. (2021). Personality and perceived stress during COVID-19 pandemic: Testing the mediating role of perceived threat and efficacy. Personality and Individual differences, 168, 110351. [CrossRef]

- Luchetti, M., Lee, J. H., Aschwanden, D., Sesker, A., Strickhouser, J. E., Terracciano, A., & Sutin, A. R. (2020). The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19. American Psychologist, 75(7), 897–908. [CrossRef]

- Maia, B. R., & Dias, P. C. (2020). Anxiety, depression and stress in university students: the impact of COVID-19. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 37. [CrossRef]

- Metin, A., Çetinkaya, A., & Erbiçer, E. S. (2021). Subjective well-being and resilience during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. European Journal of Health Psychology, 28(4), 152–160. [CrossRef]

- Moret-Tatay, C., & Murphy, M. (2022). Anxiety, resilience and local conditions: A cross-cultural investigation in the time of Covid-19. International Journal of Psychology, 57(1), 161-170. [CrossRef]

- Panter-Brick, C. (2015). Culture and resilience: Next steps for theory and practice. In L. C. Theron, L. Liebenberg, and M. Ungar (Eds.), Youth resilience and culture (pp. 233– 244). Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-017-9415-2_17.

- Ogińska-Bulik, N, Zadworna-Cieślak, M (2018) The role of resiliency and coping strategies in occurrence of positive changes in medical rescue workers. International Emergency Nursing, 39, 40–45. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J., Shen, B., Zhao, M., Wang, Z., Xie, B., & Xu, Y. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. General Psychiatry, 33, e100213. [CrossRef]

- Quintiliani, L., Sisto, A., Vicinanza, F., Curcio, G., & Tambone, V. (2022). Resilience and psychological impact on Italian university students during COVID-19 pandemic. Distance learning and health. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 27(1), 69-80. [CrossRef]

- Ran, L, Wang, W, Ai, M, et al. (2020) Psychological resilience, depression, anxiety, and somatization symptoms in response to COVID-19: A study of the general population in China at the peak of its epidemic. Social Science & Medicine, 262, 113261. [CrossRef]

- Rogowska, A.M., C. Kuśnierz, C., Bokszczanin, A. (2020). Examining Anxiety, Life Satisfaction, General Health, Stress and Coping Styles During COVID-19 Pandemic in Polish Sample of University Students. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13, 797-811. [CrossRef]

- Rosen, Z., Weinberger-Litman, S. L., Rosenzweig, C., Rosmarin, D. H., Muennig, P., Carmody, E. R., Rao ST, Litman, L. (2020, April 14). Anxiety and distress among the first community quarantined in the U.S due to COVID-19: Psychological implications for the unfolding crisis. [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. (2003). Flourishing under fire: Resilience as a prototype of challenged thriving. In C. L. M. Keyes & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived (pp. 15–36). American Psychological Association. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P. (2020). Closure of Universities Due to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impact on Education and Mental Health of Students and Academic Staff. Cureus, 12(4), e7541. [CrossRef]

- Satici, S.A., Kayis, A.R., Satici, B. et al. (2020). Resilience, Hope, and Subjective Happiness Among the Turkish Population: Fear of COVID-19 as a Mediator. International Journal of Mental Health Addiction. [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K. et al. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavavioral Medicine, 15, 194–200. [CrossRef]

- Son, C., Hegde, S., Smith, A., Wang, X., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. Journal of medical internet research, 22(9), e21279. [CrossRef]

- Sood, S., & Sharma, A. (2020). Resilience and psychological well-being of higher education students during COVID-19: The mediating role of perceived distress. Journal of Health Management, 22(4), 606-617. [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.J., Meyer, D., Neill, E., Phillipou, A., Toh, W.L., Van Rheenen, T.E.,Rossell, S.L. (2020). Considerations for assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in Australia. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 54 (11), 1067-1071. [CrossRef]

- Valladolid, V. C. (2021). The role of coping strategies in the resilience and well-being of college students during COVID-19 pandemic. Philippine Social Science Journal, 4(2), 30-42. [CrossRef]

- Van Bavel, J. J., Baicker, K., Boggio, P. S., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., Crockett, M. J., Crum, A. J., Douglas, K. M., Druckman, J. N., Drury, J., Dube, O., Ellemers, N., Finkel, E. J., Fowler, J. H., Gelfand, M., Han, S., Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., Kitayama, S., Mobbs, D., Napper, L. E., Packer, D. J., Pennycook, G., Peters, E., Petty, R. E., Rand, D. G., Reicher, S. D., Schnall, S., Shariff, A., Skitka, L. J., Smith, S. S., Sunstein, C. R., Tabri, N., Tucker, J. A., van der Linden, S., van Lange, P., Weeden, K. A., Wohl, M. J. A., Zaki, J., Zion , S. R., & Willer, R. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behaviour, 4, 460-47. [CrossRef]

- Vos, L. M., Habibović, M., Nyklíček, I., Smeets, T., & Mertens, G. (2021). Optimism, mindfulness, and resilience as potential protective factors for the mental health consequences of fear of the coronavirus. Psychiatry Research, 300, 113927. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., & Zhao, H. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on anxiety in Chinese university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1168. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Luo, S., Xu, J. et al. (2021). Well-Being Reduces COVID-19 Anxiety: A Three-Wave Longitudinal Study in China. Journal Happiness Studies 22, 3593–3610. [CrossRef]

- Yafei Huang & Peter M. Bentler (2015) Behavior of Asymptotically Distribution Free Test Statistics in Covariance Versus Correlation Structure Analysis. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 22(4), 489-503. [CrossRef]

- Yan, L., Gan, Y., Ding, X., Wu, J., & Duan, H. (2021). The relationship between perceived stress and emotional distress during the COVID-19 outbreak: Effects of boredom proneness and coping style. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 77, 102328. [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M., Arslan, G. (2020). Exploring the associations between resilience, dispositional hope, preventive behaviours, subjective well-being, and psychological health among adults during early stage of COVID-19. Current Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., Yu, Y., & Hu, J. (2021). COVID-19 among Chinese high school graduates: Psychological distress, growth, meaning in life and resilience. Journal of Health Psychology, 27(5), 1057-1069. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., Yu, Y., & Hu, J. (2022). COVID-19 among Chinese high school graduates: Psychological distress, growth, meaning in life and resilience. Journal of Health Psychology, 27(5), 1057–1069. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G, Xu, W, Liu, Z, et al. (2018) Resilience, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and posttraumatic growth in Chinese adolescents after a tornado: The role of mediation through perceived social support. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 206(2), 130–135. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J, Yang, Z, Wang, X, et al. (2020) The relationship between resilience, anxiety and depression among patients with mild symptoms of COVID-19 in China: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Clinical Nursing 29(21–22), 4020–4029. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Lan, M., Li, H., & Yang, J. (2021). Perceived stress and sleep quality among the non-diseased general public in China during the 2019 coronavirus disease: a moderated mediation model. Sleep medicine, 77, 339-345. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).