1. Introduction

Accurate load forecasting is essential for efficient planning and management of modern power systems, helping utilities maintain a stable real-time balance between supply and demand [

1]. In an era where energy needs are shaped by factors such as weather, consumer behavior, and technological advancements, forecasting must account for seasonal variations, economic shifts, and new technologies to ensure reliable energy supply. With advancements in technology, particularly Artificial Intelligence, electricity demand continues to grow annually [

2]. Accurate forecasting is essential to avoid overproduction or underproduction. This need is heightened by the increasing integration of renewable energy sources, which now account for more 6% of Australia’s electricity supply, as their variability challenges traditional forecasting methods [

3].

Energy load forecasting models can be divided into statistical models, machine learning models, deep learning models, and mixed models [

4]. Statistical models are suitable for small-scale, short-term predictions, machine learning and deep learning models can capture long- and short-term dependencies of high-dimensional data, and hybrid models combine physical laws with data-driven approaches for complex system predictions[

5]. Ref [

6] proposes the MultiDeT Transformer model with a single encoder and multi-decoder architecture, improving prediction accuracy and generalisation but requiring optimisation for complexity and applicability. Moreover, the CEEMDAN-Transformer hybrid model for short-term load forecasting is introduced, demonstrating high performance but characterised by high computational complexity and limited domain validation [

7].

Building on previous experience, recent Transformer-based architectures further refine forecasting capabilities by integrating novel techniques to enhance accuracy and generalization while addressing specific limitations. The authors present a Bayesian Transformer framework that improves probabilistic forecasting but struggles to capture complex nonlinear relationships [

8]. In Ref [

9], the author develops a Temporal Fusion Transformer model for short-term load forecasting, improving accuracy and interpretability, but showing high errors for special events and limited regional validation. To further enhance the interpretability of forecasting models, Ref [

10] introduces an attention-based deep learning model using the SHAP technique. To further validate the differences among various feature analysis techniques and assess the accuracy of hybrid models based on Transformer algorithms, we conducted a comprehensive experimental study. The contribution of this paper is as follows.

The hybrid Transformer-based model combines the self-attention mechanism with recurrent neural networks, improving load prediction accuracy and capturing long-term dependencies effectively.

The key factors influencing load prediction, such as temperature and solar radiation, are evaluated through random forest, feature ranking, and SHAP analysis, improving both prediction accuracy and model interpretability.

The proposed high-precision prediction model facilitates renewable energy integration and demonstrates adaptability across various regions and energy conditions.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section II discusses the relevant methods and the framework of the proposed model, Section III summarizes the experimental results and analysis, and Section IV provides conclusions.

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Analysis

The dataset used in this project was collected from two primary sources, including the Australian Energy Market Operator [

11] for the energy demand data and Visual Crossing for the weather-related factors [

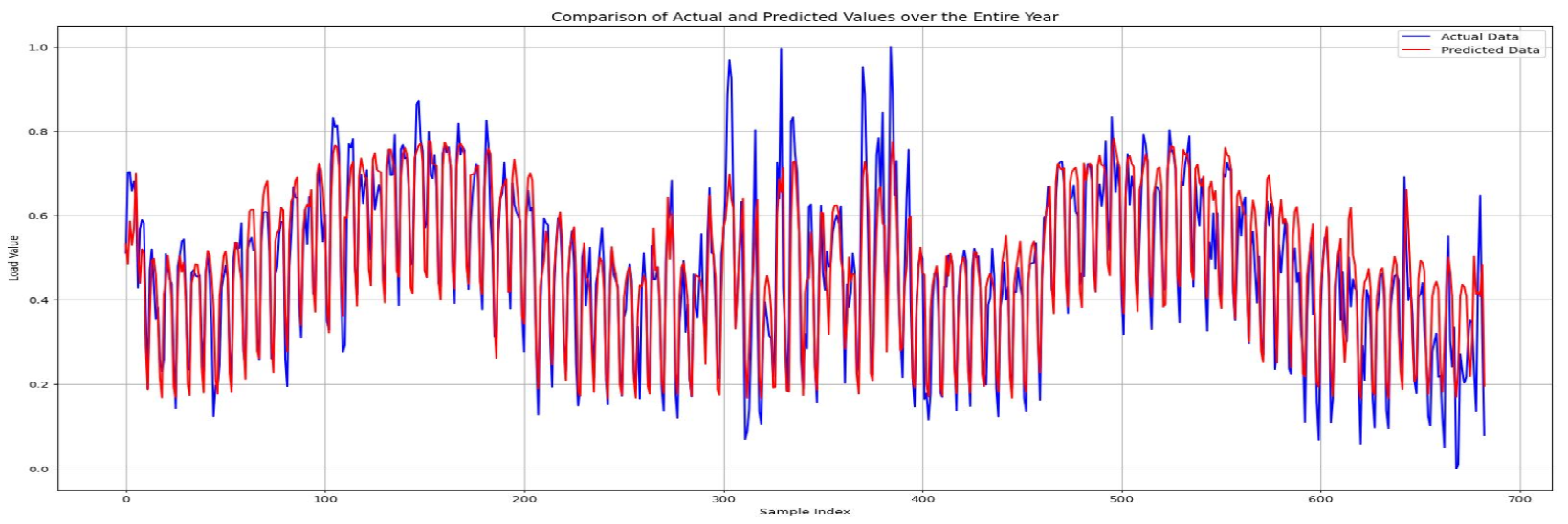

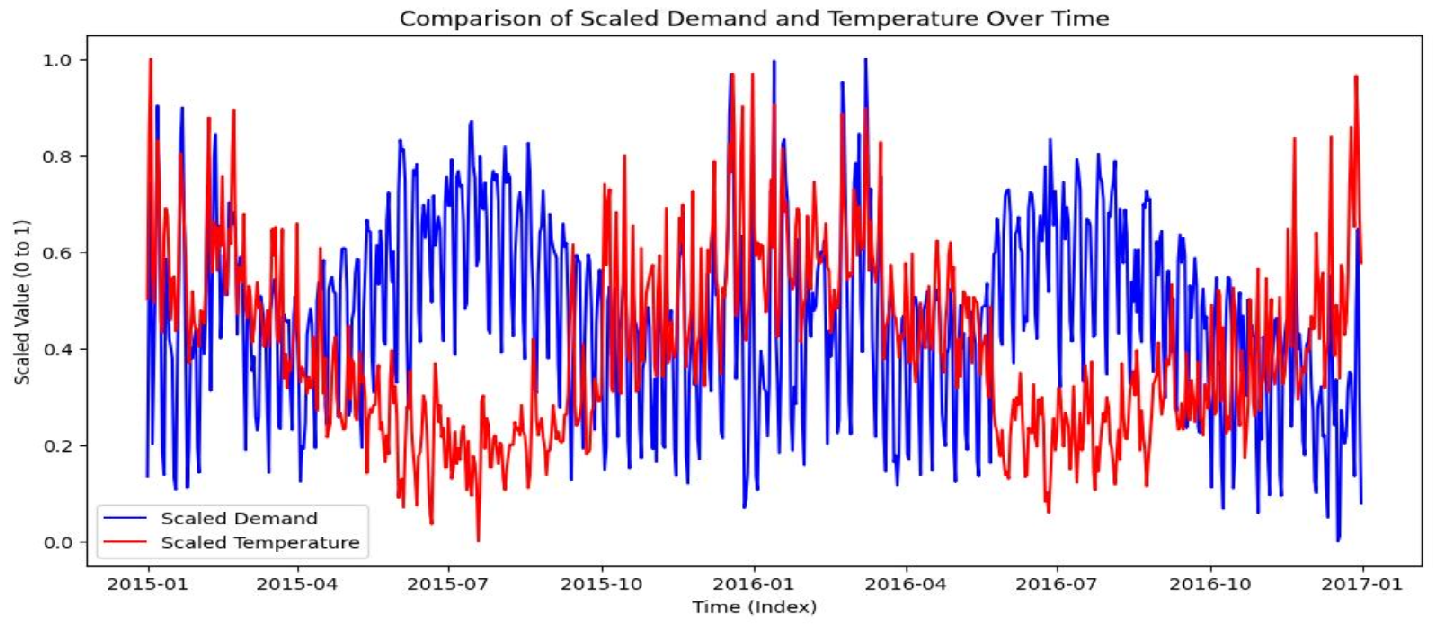

12]. The dataset comprises daily records from 2015 and 2016 for Melbourne, capturing the total energy demand, measured in kilowatt-hours (kWh), and several meteorological features recorded on the same day. The integration of weather data allows for the correlation analysis between environmental factors and energy consumption, a critical aspect of understanding demand forecasting. The demand curve, as shown in

Figure 1, demonstrates a seasonal pattern with prominent peaks during winter and summer.

2.2. Data Preprocessing

2.2.1. Feature Selection

In this paper, feature selection of the entire dataset, including all features, was used in the final run of the model. However, an analysis of feature importance was performed using random forest, permutation importance, and SHAP values.

2.2.2. Normalisation

Data normalization was performed using MinMaxScaler to ensure equal contribution of all features to the model. This process scaled the selected features to a range between 0 and 1, retains the original data distribution while eliminating the risk that certain features disproportionately influence the learning process of models due to larger values.

2.3. Hybrid Model Development

2.3.1. Transformer

The Transformer model used in this paper is a deep learning architecture based entirely on the attention mechanism [

13]. Its core is composed of the multi-head self-attention mechanism and a feedforward neural network, which performs parallel computation by capturing the dependency of any position in the sequence, greatly improving the training speed and effect [

14,

15]. Its main expression is as follows:

Multi-head self-attention:

2.3.2. Recurrent Neural Network

Recurrent neural network (RNN) is a kind of neural network architecture for processing sequence data, which can capture the dependencies in time series through cyclic connections[

16]. The core of RNN is to determine the state of the current time step by the state of the previous time step and the current input [

17]. Its main expression is:

2.3.3. Long Short Term Memory

Long-Short-Term Memory (LSTM) is an improved recurrent neural network architecture designed to solve the problem of gradient disappearance and gradient explosion in traditional RNNS. LSTM introduces memory units and gating mechanisms that allow it to efficiently capture long-term dependencies while selectively remembering or forgetting information [

17]. The function of Forget Gate, Input Gate, Candidate State Update, Cell State Update, Output Gate, Hidden State Update is as follows:

2.3.4. Gated Recurrent Unit

Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) is an improved version of the recurrent neural network [

18]. Due to the introduction of update gate and reset gate mechanisms, the gated recurrent unit (GRU) can efficiently capture time dependencies in sequence data and improve computational efficiency by simplifying the number of parameters. Its main formula is as follows:

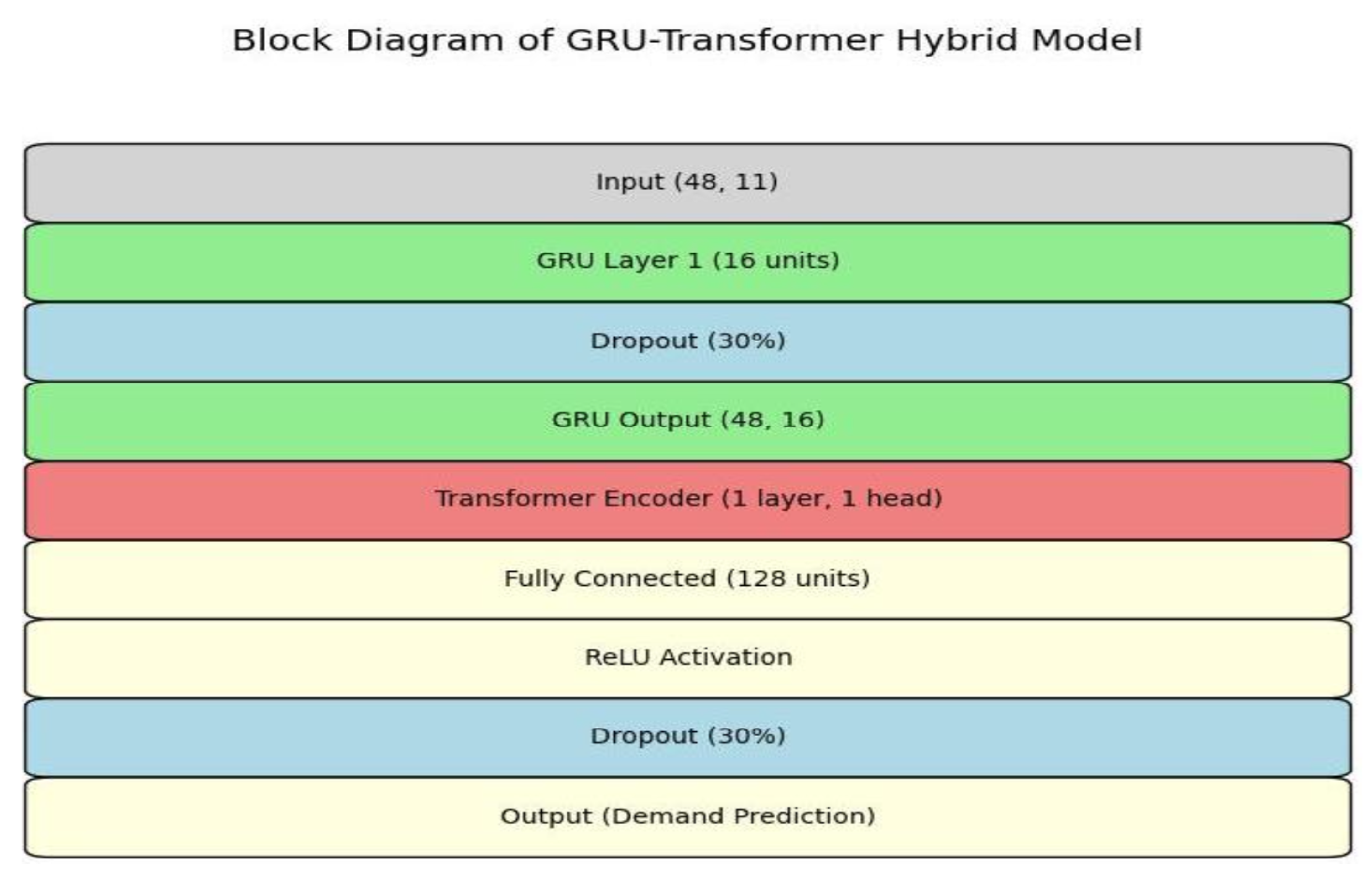

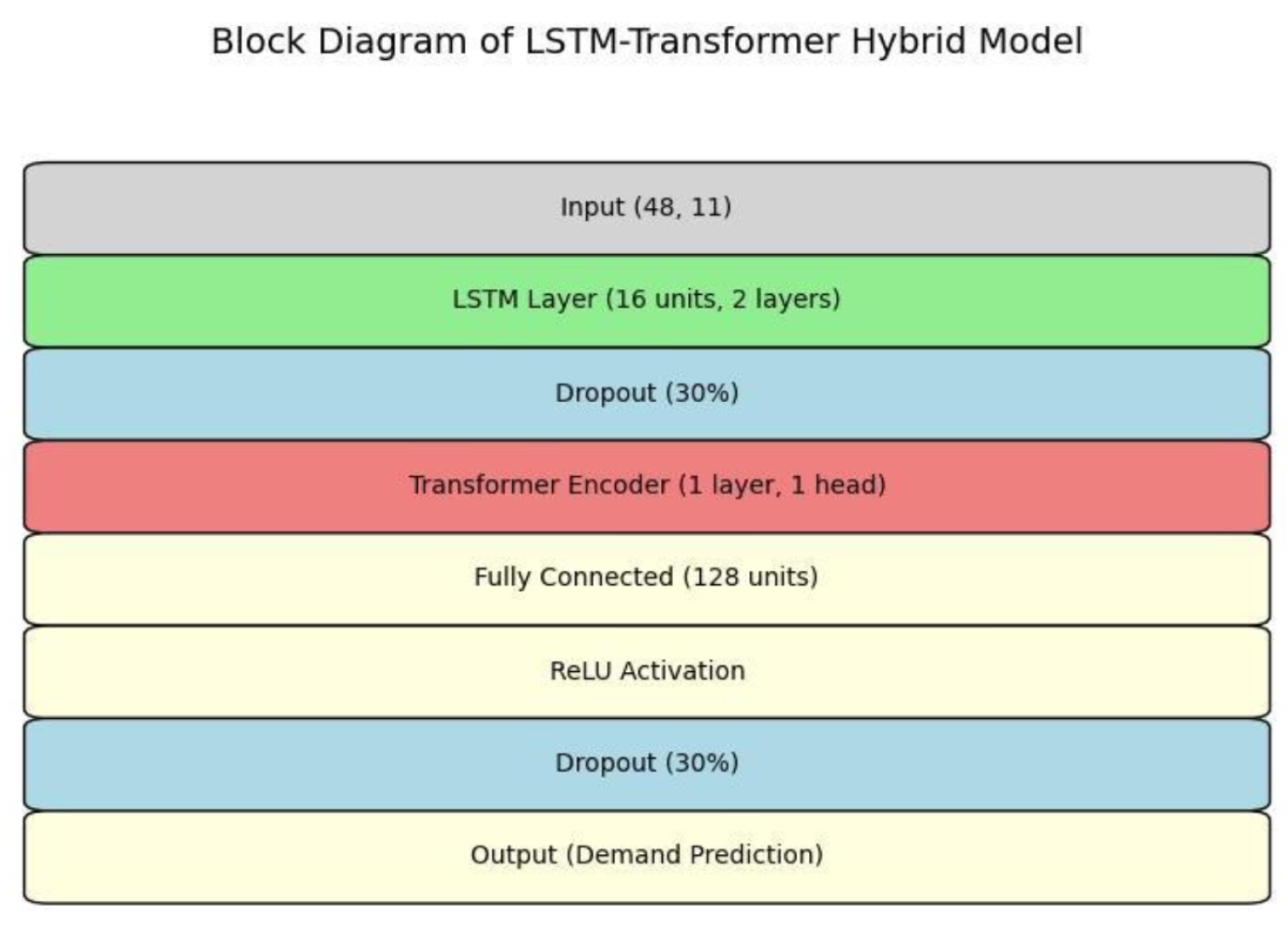

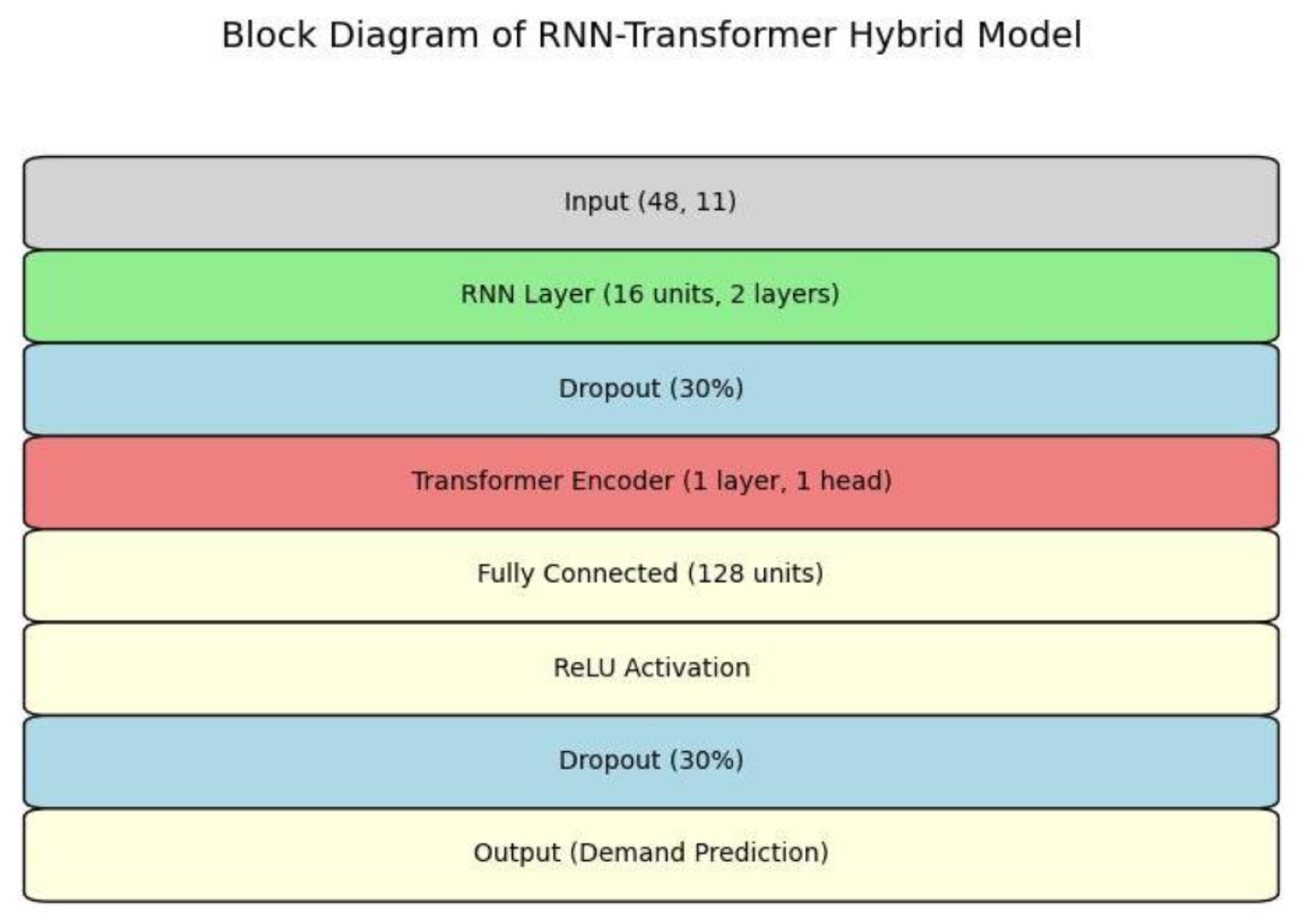

In this paper, a standard transformer model was first developed and presented as an alternative approach to load forecasting compared to traditional machine learning models. By merging the sequential capabilities of RNNs with the attention mechanisms of Transformers, hybrid models were created to balance efficiency with improved accuracy in forecasting complex time series data, which were named LSTM-GRU, GRU-RNN, LSTM-RNN, LSTM-Transformer(LSTM-TF), GRU-Transformer (GRU-TF), and RNN-Transformer (RNN-TF). Then, the focus shifted to creating three hybrid models consisting of GRU-TF, LSTM-TF, and RNN-TF, designed to improve the initial model’s performance, with

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 highlighting the model architectures and developing these hybrid models aimed at testing their effectiveness against more traditional hybrid models. By comparing all these variations, to identify the most influential architecture for accurate and efficient load forecasting.

2.4. Model Validation

This paper uses three criteria to evaluate the results, which are explained below.

2.4.1. Mean Squared Error (MSE) & Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)

MSE evaluates the average squared difference between the actual and predicted values, highlighting the most significant errors due to the squaring [

19].

2.4.2. Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

MAE measures the average absolute difference between predictions and actual values [

19]. Focusing on the average error through the predictions is ideal without heavily penalising the more significant discrepancies.

2.4.3. Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error (sMAPE)

sMAPE calculates the percentage error between the actual and predicted values, making it desirable when comparing the predictions of the model for load forecasting. sMAPE provides a balanced view of over- and under-predictions [

19].

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance and Comparison

Table 1 summarises the performance metrics of the various hybrid models tested for load forecasting. The first three hybrid models were adapted from the architectures introduced by [

20,

21] and [

22] to fit the input data source for this report. Each model uses different neural network architectures to capture dependencies within the time series data. Then these were evaluated and compared against the hybrid transformer models.

The RNN-TF model consistently outperformed the other models, achieving the lowest MSE of 0.0066 and the RMSE of 0.0811. This indicates that this model was effective in minimising both the overall and the more significant errors within the predictions; additionally, it had the lowest sample of 15.09% and MAE of 0.0581. The RNN-TF model demonstrates strong generalisation, effectively capturing both short-term fluctuations and long-term dependencies for accurate predictions. These results show that Transformer-based models significantly outperform traditional RNN and LSTM architectures. Combining RNN or GRU with Transformer layers utilizes recurrent networks for sequences and Transformers for long-term trends.

3.2. Feature Importance

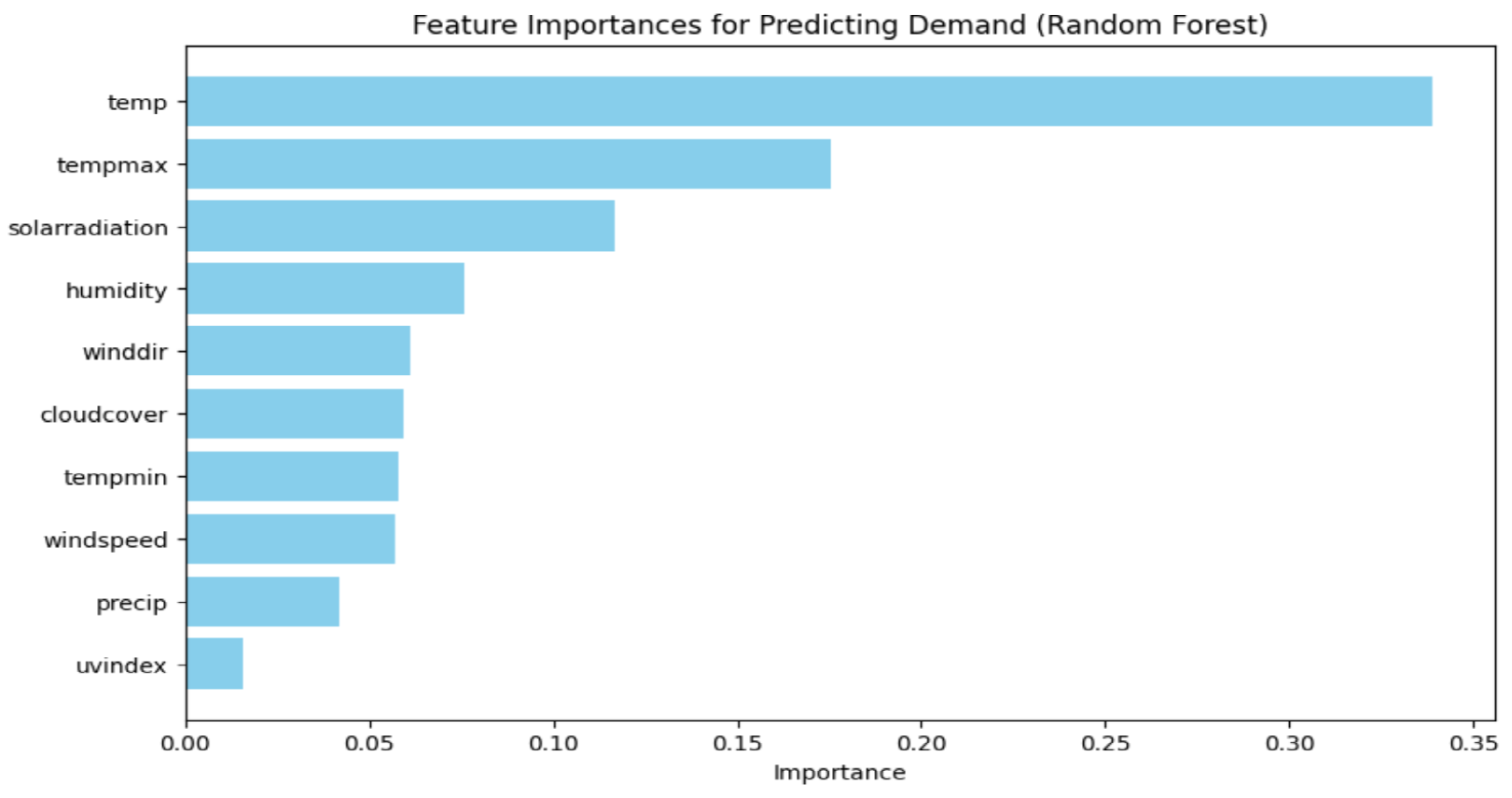

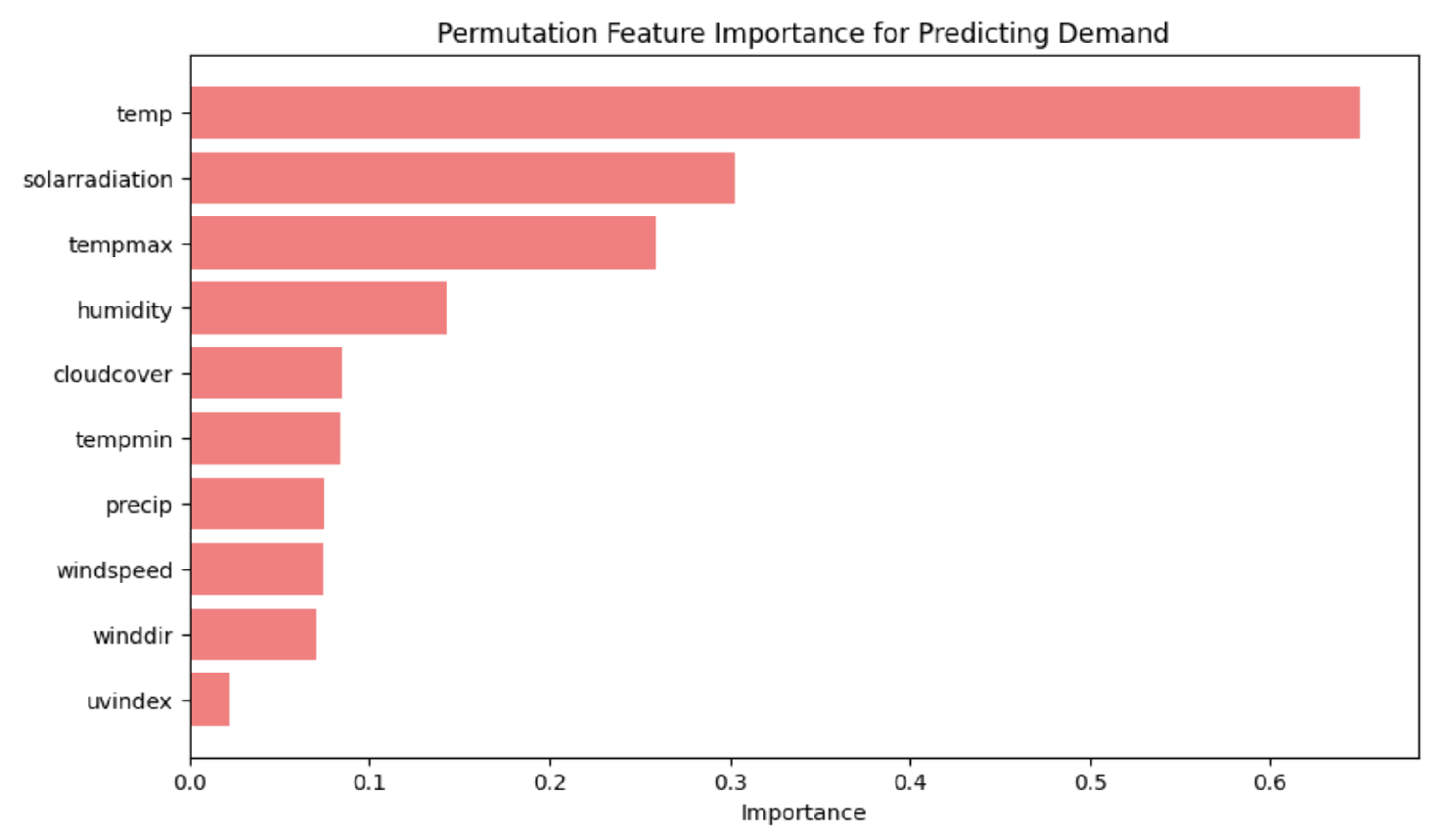

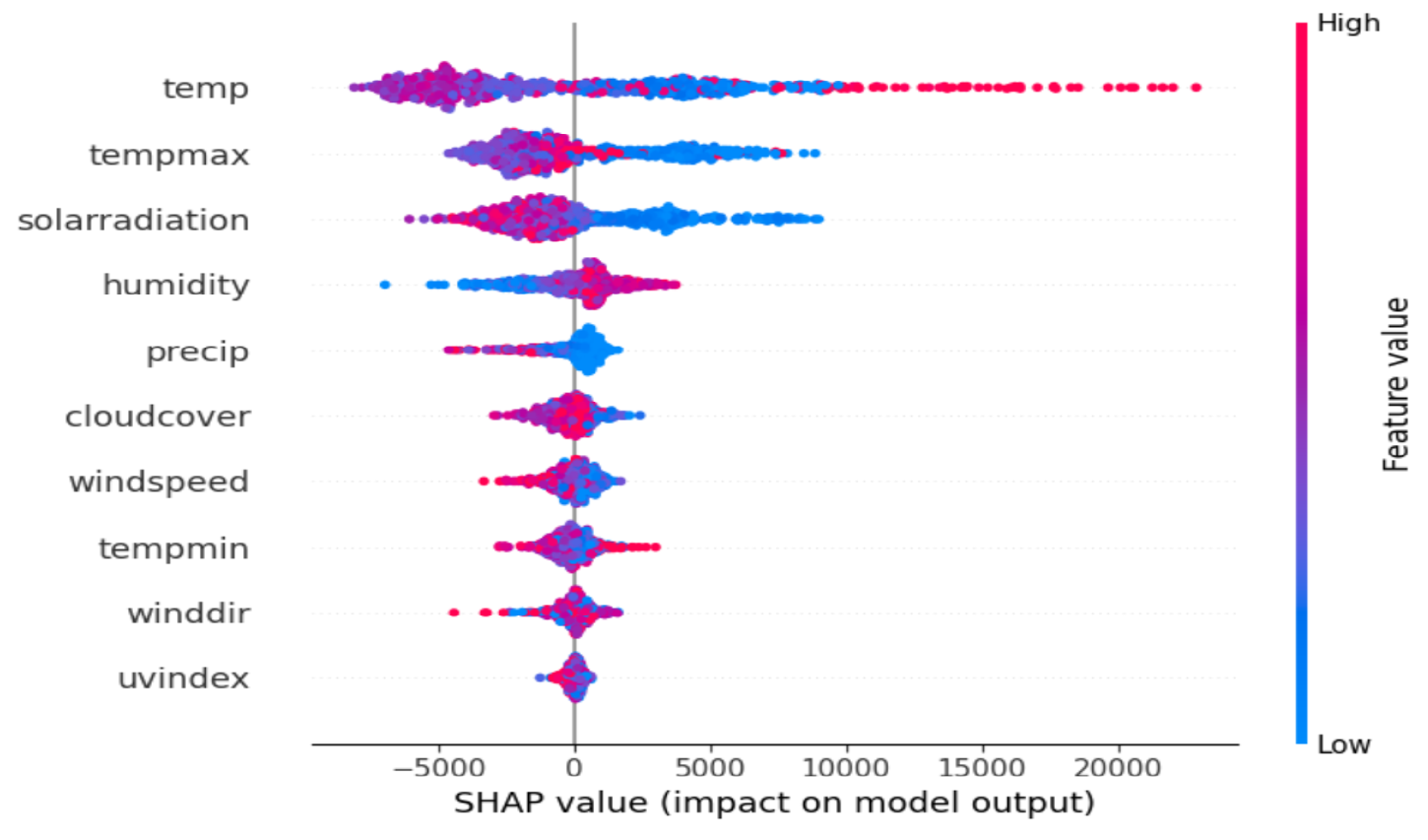

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 analyze feature importance in predicting energy demand using Random Forest, Permutation Importance, and SHAP methods. All three consistently identify temperature as the most influential factor, with TempMax and solar radiation also playing key roles. Temperature contributes about 35% to predictions, but the methods differ in ranking the second and third most important features. The random forest has TempMax, contributing to the second most predictions at 17.5%. Permutation is 30% more important than solar radiation. This is then inverted for the third most crucial weather feature, with RF placing solar radiation at 12% and permutation importance displaying TempMax at around 25%.

Table 2 gives the rank result.

Temperature is the primary driver of energy demand [

23], with a 1°C rise potentially increasing demand by 0.5-8.5% [

24]. Other factors have a lesser impact, as shown by random forest and permutation importance. SHAP values provide a detailed view, highlighting the distinct roles of temperature, humidity, and solar radiation in influencing energy demand.

3.2.1. Temperature

Figure 7 shows that warmer days (red dots) lead to higher energy demand, while cooler days (blue dots) also increase demand due to heating needs.

3.2.2. Solar Radiation

As shown in

Figure 5, solar radiation significantly impacts energy demand. Lower solar radiation reduces temperatures, increasing heating requirements.

3.2.3. Humidity

Humidity moderately affects energy demand, as highlighted in

Figure 7. Higher humidity (red dots) tends to increase demand, but its influence is less significant compared to temperature or solar radiation.

3.2.4. Seasonal Trends

Temperature’s impact on energy demand varies seasonally.

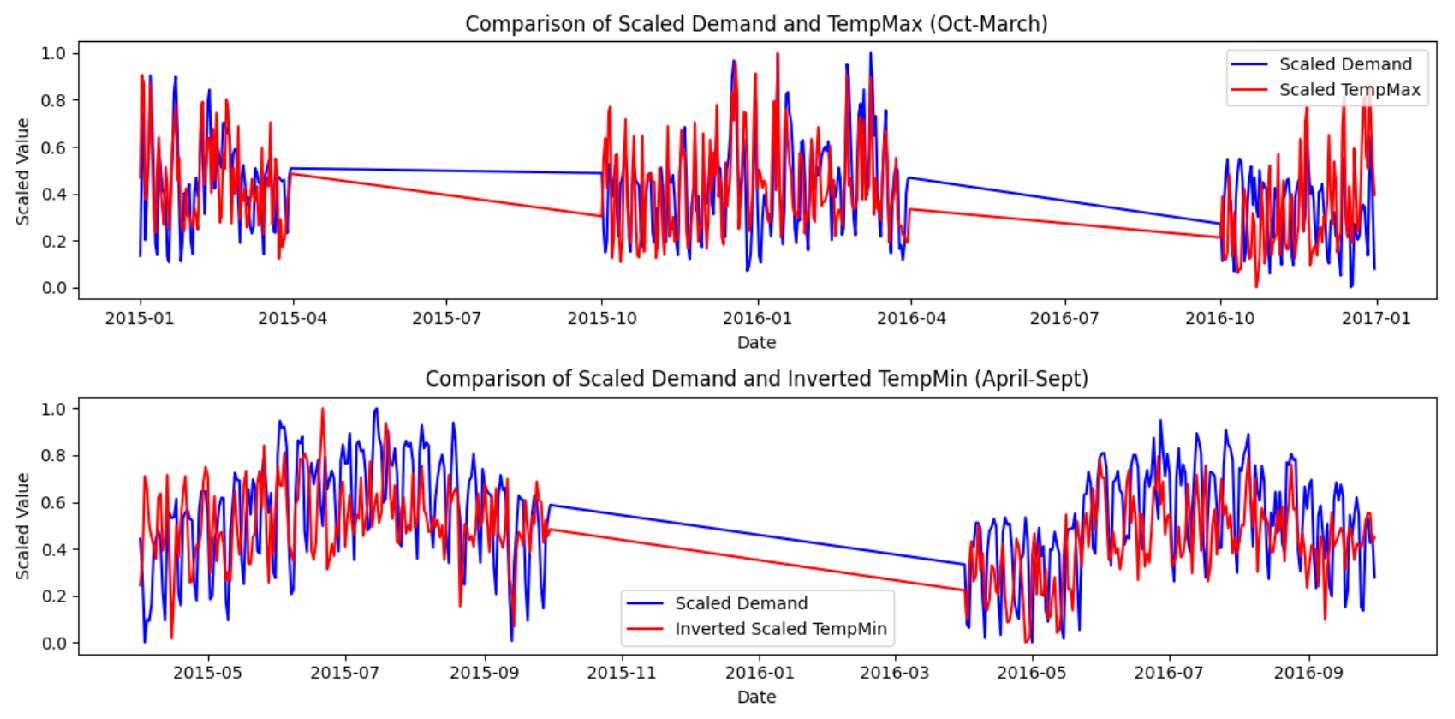

Figure 8 shows a positive correlation in the warmer months and an inverse relationship in colder months, making the yearly trends less consistent.

Figure 9 divides the data into two periods to better capture seasonal effects. From October to March, the positive correlation between TempMax and demand is 0.513, as higher temperatures drive cooling needs. From April to September, TempMin shows a negative correlation of -0.382. By inverting the TempMin values during this period, the correlation becomes 0.382, indicating that lower temperatures increase energy consumption, although less significantly than in summer.

4. Conclusions

This paper demonstrates the effectiveness of hybrid Transformer models in improving load forecasting accuracy. With the hybrid RNN-TF emerging as the best performer in all metrics, the RNN-TF model achieved the lowest MSE of 0.0066, RMSE of 0.0811, MAE of 0.0581, and sMAPE of 15.09%, significantly outperforming traditional hybrid models based on RNN, GRU and LSTM. These results highlight the advantage of combining recurrent neural networks with Transformer-based architectures, which can better capture short-term fluctuations and long-term dependencies in energy demand than traditional models. Furthermore, the GRU-TF model also performed well, with an MSE of 0.0074 and sMAPE of 15.73%, demonstrating that hybrid models balance efficiency and forecast precision.

The feature importance analysis further reinforced how critical weather variables, particularly temperature, influence demand. This paper provides valuable information on the factors driving energy consumption by incorporating feature importance methods such as Random Forest, Permutation Importance, and SHAP. In addition, accurate load prediction is vital to maintaining the stability and efficiency of power systems. Predicting energy demand with greater precision allows utility companies to balance electrical supply and demand, reducing the risk of outages or overproduction. Inaccurate forecasting can lead to significant economic losses, with minor errors resulting in large operational inefficiencies, higher costs, and potentially increased customer energy prices.

References

- Chandrasekaran, R.; Paramasivan, S.K. Advances in deep learning techniques for short-term energy load forecasting applications: A review. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2024, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobeiry, S.M. AI-Enabled Modern Power Systems: Challenges, Solutions, and Recommendations. In Artificial Intelligence in the Operation and Control of Digitalized Power Systems; Springer, 2024; pp. 19–67. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X. Emerging power quality challenges due to integration of renewable energy sources. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2016, 53, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Mo, H.; Wu, J.; Pan, L.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; Huang, F. A hybrid stacking model for enhanced short-term load forecasting. Electronics 2024, 13, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casolaro, A.; Capone, V.; Iannuzzo, G.; Camastra, F. Deep learning for time series forecasting: Advances and open problems. Information 2023, 14, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Z.; Zheng, T.; Hu, J.; Zhang, K. A transformer-based method of multienergy load forecasting in integrated energy system. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2022, 13, 2703–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, P.; Dong, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, J. Short-term load forecasting based on CEEMDAN and Transformer. Electric Power Systems Research 2023, 214, 108885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, K. Probabilistic multi-energy load forecasting for integrated energy system based on Bayesian transformer network. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, P.C.; Minh, N.Q.; Tien, N.D.; Anh, T.T.Q. Short-term electricity load forecasting based on temporal fusion transformer model. Ieee Access 2022, 10, 106296–106304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, M.A.A.; Shanmugam, B.; Azam, S.; Thennadil, S. Enhancing smart grid load forecasting: An attention-based deep learning model integrated with federated learning and XAI for security and interpretability. Intelligent Systems with Applications 2024, 23, 200422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AEMO. Aggregated Price and Demand Data. Retrieved October 21, 2024, from https://aemo.com.au/en/energy-systems/electricity/national-electricity-market-nem/data-nem/aggregated-data, n.d.

- Crossing, V. Historical Weather Data & Weather Forecast Data. Retrieved October 21, 2024, fromurlhttps://www.visualcrossing.com/weather-data, n.d.

- Vaswani, A. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Xiao, A.; Wu, E.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y. Transformer in transformer. Advances in neural information processing systems 2021, 34, 15908–15919. [Google Scholar]

- Dan, H.C.; Huang, Z.; Lu, B.; Li, M. Image-driven prediction system: Automatic extraction of aggregate gradation of pavement core samples integrating deep learning and interactive image processing framework. Construction and Building Materials 2024, 453, 139056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Lai, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Yu, Y.; Wan, Z.; Lengerich, B.; Wu, Y.N. Efficient Large Foundation Model Inference: A Perspective From Model and System Co-Design. 2024, arXiv:2409.01990. [Google Scholar]

- Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 2020, 404, 132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, R.; Salem, F.M. Gate-variants of gated recurrent unit (GRU) neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 60th international midwest symposium on circuits and systems (MWSCAS); IEEE, 2017; pp. 1597–1600. [Google Scholar]

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M.J.; Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. Peerj computer science 2021, 7, e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zor, K.; Buluş, K. A benchmark of GRU and LSTM networks for short-term electric load forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Innovation and Intelligence for Informatics, Computing, and Technologies (3ICT); IEEE, 2021; pp. 598–602. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, M.; Shao, H.; Ma, X.; De Silva, C.W. A stacked GRU-RNN-based approach for predicting renewable energy and electricity load for smart grid operation. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2021, 17, 7050–7059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Dong, Z.Y.; Jia, Y.; Hill, D.J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Short-term residential load forecasting based on LSTM recurrent neural network. IEEE transactions on smart grid 2017, 10, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Vazquez, M.A.; Kirschen, D.S. Economic impact assessment of load forecast errors considering the cost of interruptions. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE power engineering society general meeting. IEEE; 2006; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Santamouris, M.; Cartalis, C.; Synnefa, A.; Kolokotsa, D. On the impact of urban heat island and global warming on the power demand and electricity consumption of buildings—A review. Energy and buildings 2015, 98, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).