1. Introduction

The skin is our largest organ, which separates our body from the environment and protects us from physical, chemical and biological/microbiological influences. It ensures the body's homeostasis and is also an important platform for the application of medication and cosmetic treatments. Its anatomical structure is provided by three main layers, the epidermis, the dermis and the subcutis. The uppermost layer of the epidermis is the stratum corneum, which consists of dead corneocytes located close to each other embedded in lipid matrix. The layer below is the viable epidermis, in which, in addition to the main cell type of keratinocytes, there are also melanocytes, Langerhans and Merkel cells, which have an immunological role. This layer plays the most important role in the barrier function of the skin. The second layer, the dermis, contains capillary vessels (endothelial cells), hair follicles, sweat glands and ducts, as well as sebaceous glands, neuronal elements, in addition to fibroblasts [

1]. The structure of this layer is looser and plays a significant role in the elasticity and mechanical properties of the skin, which is ensured by the extracellular matrix elements such as collagens, fibronectin, elastin and fibrillins. The third layer is the subcutis, or hypodermis, the thickness of which varies greatly in different parts of the body and in the case of different individuals. The main cell type in this layer is the adipocytes, which play an important role in thermoregulation. Researchers are currently working on the development of several skin models, depending on the purpose for which the given artificial skin substitute is to be used. A possible and very important area of indication of application of skin equivalents is skin replacement and regeneration, which would be a crucial option in the case of acute and chronic wounds and burns [

2,

3]. This requires the production of full-thickness, vascularized skin tissue [

4]. However, less complex in vitro skin substitutes can be used for other purposes as well. For example, to test the main effect or side effect (irritation, toxicity) of topical pharmaceutical preparations or cosmetics. For this purpose, many companies have developed models of different complexity, such as human reconstructed epidermis and full thickness skin (Epiderm and EpiDermFT from MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA, USA; EpiSkin from L’Oréal, Lyon, France; SkinEthic from SkinEthic, Lyon, France; EpiCs from CellSystems, Troisdorf, Germany; Straticell from Straticell, Les Isnes, Belgium; GraftSkin from Apligraf Organogenesis, La Jolla, Ca, USA; VitroLife-Skin, Kyoto, Japan).

In the present study, we developed and optimized a relatively low complexity skin substitute for permeability studies, in which the emphasis was placed on the establishment of cell-cell interactions and barrier formation and the appropriate initial parameters and components were determined. The current series of experiments can serve as a starting point for the selection of proper 3D skin bioprinting systems and cell-bioink compositions. In the experimental system presented here, we show a comparative evaluation of two hydrogels, alginate and GelMA C, which, combined with human keratinocytes (HaCaT), are able to form epidermal barrier of varying degrees of efficiency. By examining the permeability, histological structure, and intercellular connections of the created skin models, a recommendation for the development of future artificial skin equivalents was formulated at the end of this article.

Sodium alginate-based hydrogels are one of the most studied hydrogel systems in the field of 3D bioprinting due to its good biocompatibility, low cost and excellent printability and versatility [

5]. It has structural similarity to the native extracellular matrix (ECM) due to its similarity to the glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) in the human body [

6]. The skin's extracellular matrix is composed of a variety of biological macromolecules that have both structural and functional roles, including different types of collagens, glycosaminoglycans, proteoglycans, fibrillins, laminins, and integrins [

7]. The fast gelation and shear thinning properties of the alginate accounts for its good printing fidelity properties [

8,

9]. Despite all these benefits, alginate does not possess cell activating sites to improve cell viability and has poor degradation. One of the commonly used polymers in combination with alginate is gelatin which is a thermo-responsive biopolymer derivative from collagen. Gelatin is biocompatible, bioresorbable biopolymer rich in arginine, glycine, and aspartic acid (Arg-Gly-Asp / RGD) motifs that help in cell attachment. Although gelatin offers cell adhesion motifs, it does not provide any other bioactive cues. Also, it has higher enzymatic degradation rates and low mechanical stability due to its higher solubility in the physiological environment. This can be improved by incorporating natural and synthetic polymers, and inorganic materials to increase the stability of the system [

10,

11].

Gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) has attracted the widespread interest of researchers because of its excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and moldability [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Various structures have been constructed from GelMA hydrogel, including 3D scaffold, injectable gel, bio-printed scaffold, and electrospun fibrous membrane via precise fabrication methods such as light-induced crosslinking, extrusion 3D printing, electrospinning, or microfluidics. Due to its unique characteristics and simple preparation, GelMA hydrogel demonstrates superior performance and promising potential in a broad range of biomedical applications involving wound healing, drug delivery, biosensing, and tissue regeneration [

15,

16].

HaCaT cells are a spontaneously immortalized, human keratinocyte cell line that has been widely used for studies of skin biology and differentiation [

17]. This cell line was used in the current study to generate epidermal barrier formation in hydrogels.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bioinks (Hydrogels)

In the current study two hydrogels were compared. The first hydrogel contained 3% of alginate (Merck-Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) and 1% of gelatine (Merck-Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany). HaCaT cells were loaded into the hydrogel in the proper concentrations (10M/mL, 50M/mL and 100M/mL). Discs with 6 mm of diameter and 1.77 mm of thickness were created by pipetting and stabilized by crosslinking with 200 mM CaCl2 solution immediately to prevent dehydration. Following a two-minute incubation period, the structures were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4) and stored in PBS until the permeability experiment.

The second hydrogel GelMa C (CellInk, Gothenburg, Sweden) contained gelatin methacrylate and nanofibrillated cellulose, which was loaded by HaCaT cells in the proper concentrations (10M/mL, 50M/mL, 100M/mL). Discs with 6 mm of diameter and 1.77 mm of thickness were created by pipetting, stabilized by photo-crosslinking using UV light for 2 min, and stored in PBS until the permeability experiment.

2.2. Rheological Investigation of Hydrogels

Rheological measurements were performed on both hydrogels before crosslinking by Kinexus Pro Rheometer (Malvern Instruments Ltd, UK) registering the data with rSpace for Kinexus Pro 1.3 software. The samples were characterized using a PU20 SC0202 SS plate geometry where the gap for sample placement was 0.1 mm. Rotational measurements with controlled shear rate (0.1-100 1/s) were done at 25 °C controlled with an accuracy of ± 0.1 °C by Peltier system of the instrument. In all measurements a cylindrical cover made of stainless steel was placed over the samples, in order to create a closed, saturated volume round the sample and to prevent evaporation [

18].

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy

The crosslinked bioinks (both alginate and GelMA C) were frozen in liquid nitrogen and freeze-dried for analysis through scanning electron microscopy. Images were acquired using a Hitachi TM4000Plus II scanning electron microscope using a 15 keV acceleration voltage in secondary electron mode (SE) at an 11 mm working distance.

2.4. Cells and Culturing

HaCaT cell line was obtained from Cell Lines Service (CLS, Heidelberg, Germany). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) high glucose medium (Biosera, Cholet, France) supplemented with 10 v/v% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Biosera, Cholet, France), 4 mM L-glutamine (Biosera, Cholet, France), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Biosera, Cholet, France) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO

2. Medium exchange or subculturing occurred every 2nd or 3rd day. The cells were routinely maintained by regular [

19]. The HaCaT cells used for the experiments were between passage numbers 20 and 60.

Cell counts were determined using the trypan blue dye exclusion method with a Bürker chamber. Initially, cells were seeded at densities of 5 × 105 cells/12 ml/T75 flasks (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany). Upon reaching the desired cell number, cells were suspended in the bioinks as described above. 50 µL of cell-containing bioink were loaded into an aluminum frame to form a disc (see at 2.1). The alginate scaffolds were crosslinked with a 200 mM CaCl2 solution for 2 minutes, while the GelMA C discs were stabilized with UV exposure for 2 min. Samples were washed with phosphate buffered saline and cultured for 1, 2, 3 or 4 weeks in DMEM media (refreshed every 2nd or 3rd day).

2.5. In Vitro Viability Study on HaCaT Cells (Sulforhodamine B Assay-SRB)

Cell viability after exposure to the diluted hydrogels was determined by colorimetric SRB assay. HaCaT cells (3000 cells/well) were seeded into 96-well plates, incubated at 37°C overnight to let them attach, and treated with diluted alginate and GelMa C hydrogels. The hydrogels (alginate and GelMa C) were preheated to 37°C and diluted at ratios of 1:1 and 1:8 in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS before adding to the cells. Following 72 hours of incubation, the media was discarded, and the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline solution (Gibco, Grand Island, NJ, USA; pH 7.4), and the cellular proteins were fixed by adding 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA; Sigma–Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) and incubated for 1h at 4 °C. After removing the TCA, the wells were washed in tap water, air-dried, and stained with 0.4% SRB dye solution (Sigma–Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) in 1% glacial acetic acid for 15 min at room temperature. Unbound SRB was removed by washing with 1% acetic acid before air drying. The bound stain was solubilized with 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8), and the optical densities were read on an automated spectrophotometric plate reader at a single wavelength of 570 nm [

20,

21,

22].

2.6. Histology and Immunohistochemistry

For the detailed visual analysis of tissue formation in cell containing bioinks classical histological methods were chosen [

23]. Modern histological softwares enable more precise measurements, facilitating the quantification of observations. One of the most common staining methods, which utilizes hematoxylin and eosin, was applied. For the histological analysis 4 µm thick hematoxylin-eosin (HE) stained slides were produced from the cell containing hydrogel discs by standard histological procedure from formalin fixed paraffin embedded blocks. The slides were scanned by 3DHistech Panoramic 250 Flash III scanner (3DHISTECH Ltd, Budapest, Hungary).

From the same paraffin blocks sections were cut also for immunohistochemistry. Anitbodies for E-Cadherin (Dako, M361201-2) and Claudin 4 (invitrogen; 32-9400) were used with ultraView Universal DAB Detection Kit (5269806001) and stained by Roche – Ultra plus stainer, according to the manufacturer’s recommendation.

2.7. Caffeine Cream Formulation

Caffeine cream was used as a hydrophilic model formulation for testing the barrier function of the artificial skin models. The caffeine cream was prepared with the following composition (

Table 1.):

The cream was prepared ex tempore under magistral conditions. The lipophilic components were melted in an enamel bowl over a water bath, Polysorbate 60 was added, homogenized with a pestle, and then the water of the same temperature was emulsified in the lipophilic phase. The cream was stirred continuously, and the active ingredient (2%) was dispersed thoroughly in it. The preservative, propylene glycol was added to the preparation when it cooled below 30°C and stirring was continued until the cream was cooled further to room temperature [

25]. The preparation was stored in the refrigerator (2-8 °C) until use.

2.8. In Vitro Permeation Study in Skin-on-a-Chip Microfluidic Device

The skin-on-a-chip microfluidic diffusion chamber is a polydimethylsiloxane-based system in an aluminum frame that was developed by our research group [

24,

26,

27,

28]. It contains two compartments (donor and acceptor), and the barrier model was placed between them. The following barrier models were tested: 1) blank and cell containing alginate scaffolds, 2) blank and cell containing GelMA C scaffolds, 3) cellulose acetate membrane (pore size: 0.45 µm, Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany) soaked in isopropyl myristate for 30 min prior to the experiment, 4) rat skin after 10 tape strippings (male Wistar rats weighing 572–615 g, ToxiCoop Zrt., Budapest, Hungary). The diffusion surface was 0.283 cm2, which was separating the cream containing donor chamber and the receptor chamber, filled with peripheral perfusion fluid (PPF, consists of 147 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, and 2.3 mM CaCl

2, all substances acquired from Sigma-Hungary Kft., Budapest, Hungary). The PPF flow was continuous in the receptor compartment with a flow rate of 4 μL/min, ensured by a syringe pump (NE-1000, New Era, Farmingdale, NY, USA). The samples were collected every 30 min for 5 h. Caffeine concentrations of the perfused physiological fluid samples were determined with an UV-VIS spectrophotometer (NanoDrop™ 2000, Thermo Scientific, Budapest, Hungary) immediately after each sample collection. The absorption maximum of caffeine was detected at 272 nm.

2.9. Statistics

The skin-on-a-chip data were averaged, the means and standard error of the mean (SE) were calculated and presented. Area under the curve (AUC) values were calculated using the trapezoidal rule. For statistical comparison, 1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used in OriginPro 2022 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, US). A p value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Rheological Comparison of Hydrogels

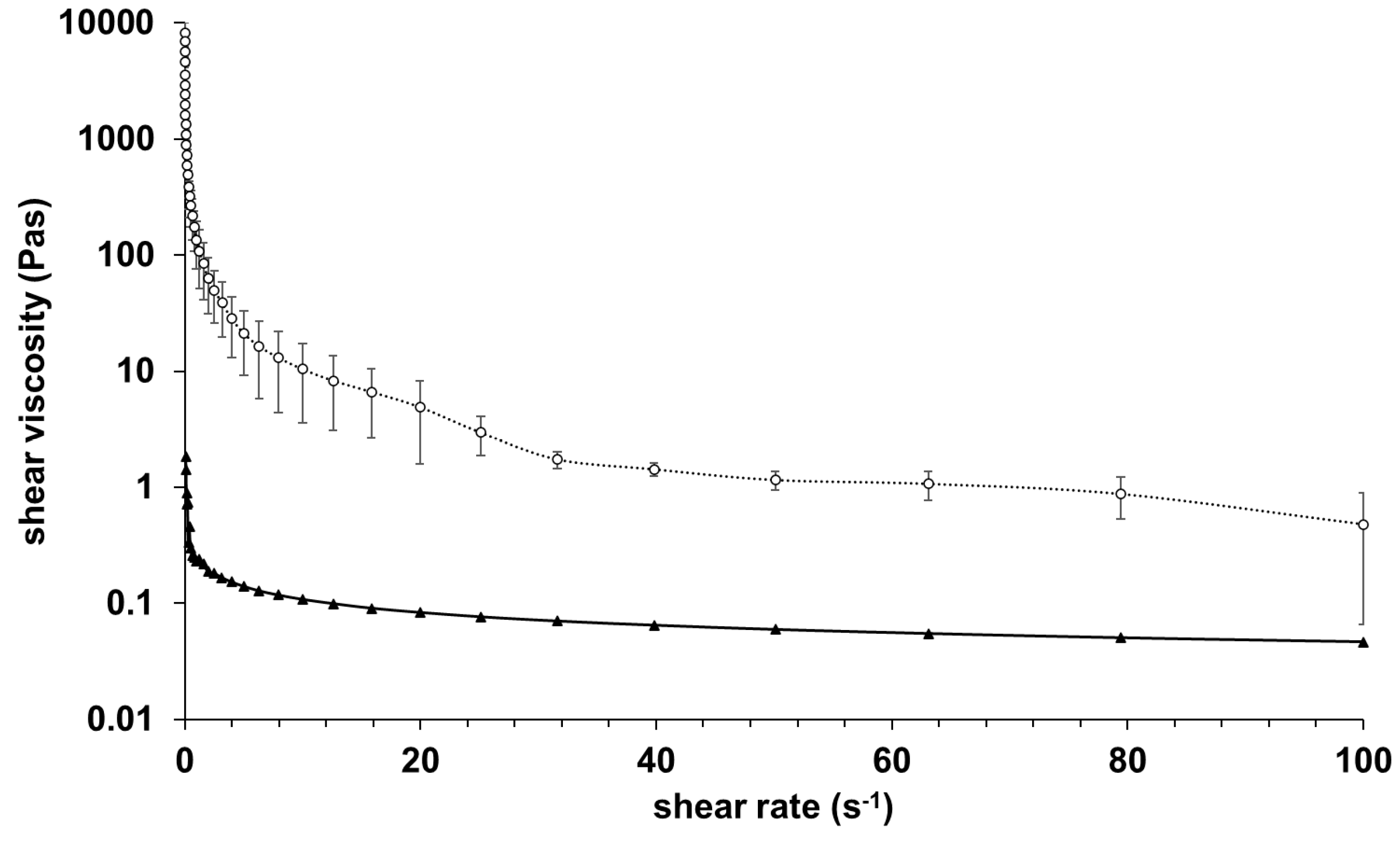

The results of rheological investigations of alginate and GelMA C hydrogels are presented in

Figure 1.

The samples were very different in their viscosity, GelMA C was significantly more viscous at 25°C, however, both showed shear-thinning behavior. This behavior can be characteristic of the entanglement of the polymer molecules on increasing shear rate.

3.2. Morphological Comparison of Hydrogels

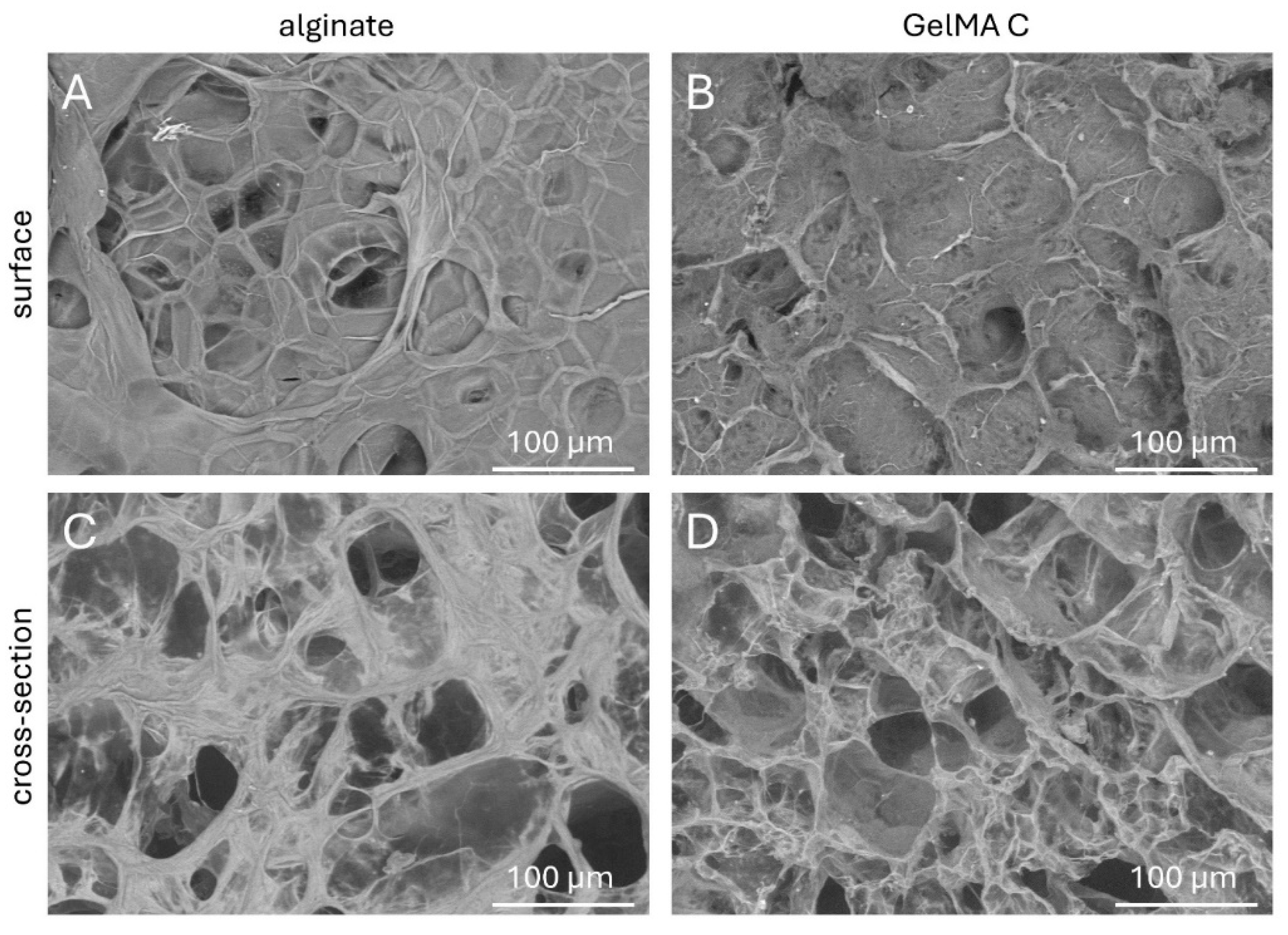

To better understand the topography and internal structures of hydrogels the corresponding cross-sectional and superficial microstructures of acellular discs were examined by scanning electron microscopy.

As it is shown in

Figure 2 C and D, the cross-sectional microstructures of the GelMA C hydrogel visually exhibited a loose, honeycomb-like morphology with different pore sizes most probably due to the variable degree of substitution of gelatine methacrylate of the hydrogel during photo-crosslinking. On the other hand, alginate showed a more compact structure but also wide variety in pore sizes.

The superficial images presented a relatively smooth surface for alginate, but more irregular characteristics for GelMA C (

Figure 2 A and B).

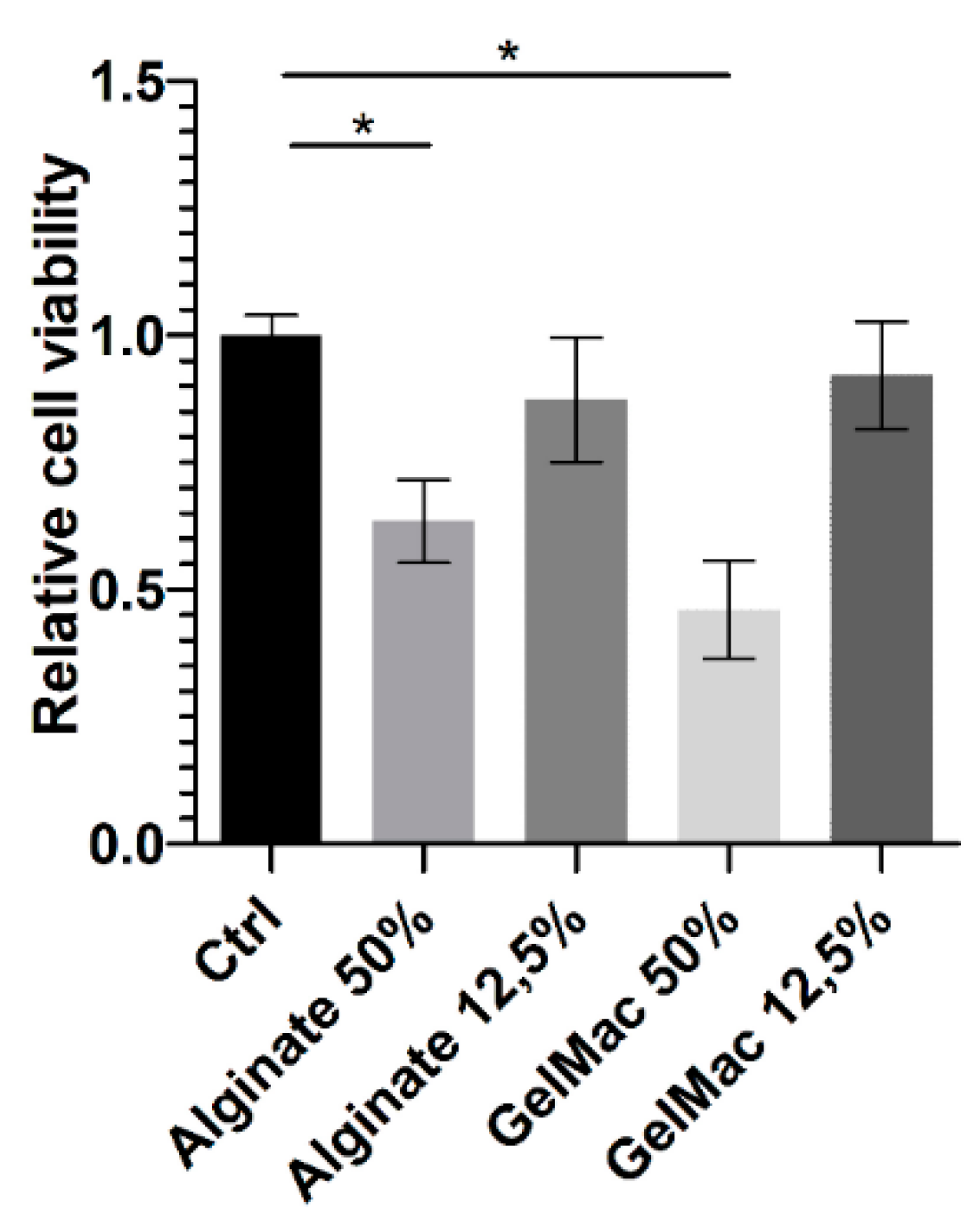

3.3. Viability Study on Keratinocytes

Based on the results of SRB assay (

Figure 3) before chemical or physical stabilization both alginate and GelMa C hydrogels expressed a concentration-dependent and significant inhibitory effect on the viability of keratinocytes. However, by this assay, it cannot be judged, that this is a cytotoxic or cytostatic effect. Several authors investigated the different variations and formulations of alginate and GelMa scaffolds for biocompatibility [

29,

30,

31]. But, in the different studies diverse incubation times and cell numbers were applied. Also, the majority of the authors tested the scaffolds after crosslinking and reported remarkable effect of the hydrogels on cell viability. However, with tailoring the parameters of the polymers (e.g. encapsulation, chemical conjugation, nano-formulation), this effect can be weakened for better chance to application in tissue engineering. On the other hand, the toxic effect of hydrogels on bacterial strains might be beneficial when the fabricated artificial tissue is intended to use for instance as a wound dressing [

32]. In the report of Cano-Vincent and co-workers, the generated alginate biofilm products possessed antibacterial, antiviral and anticancer activities as well [

32].

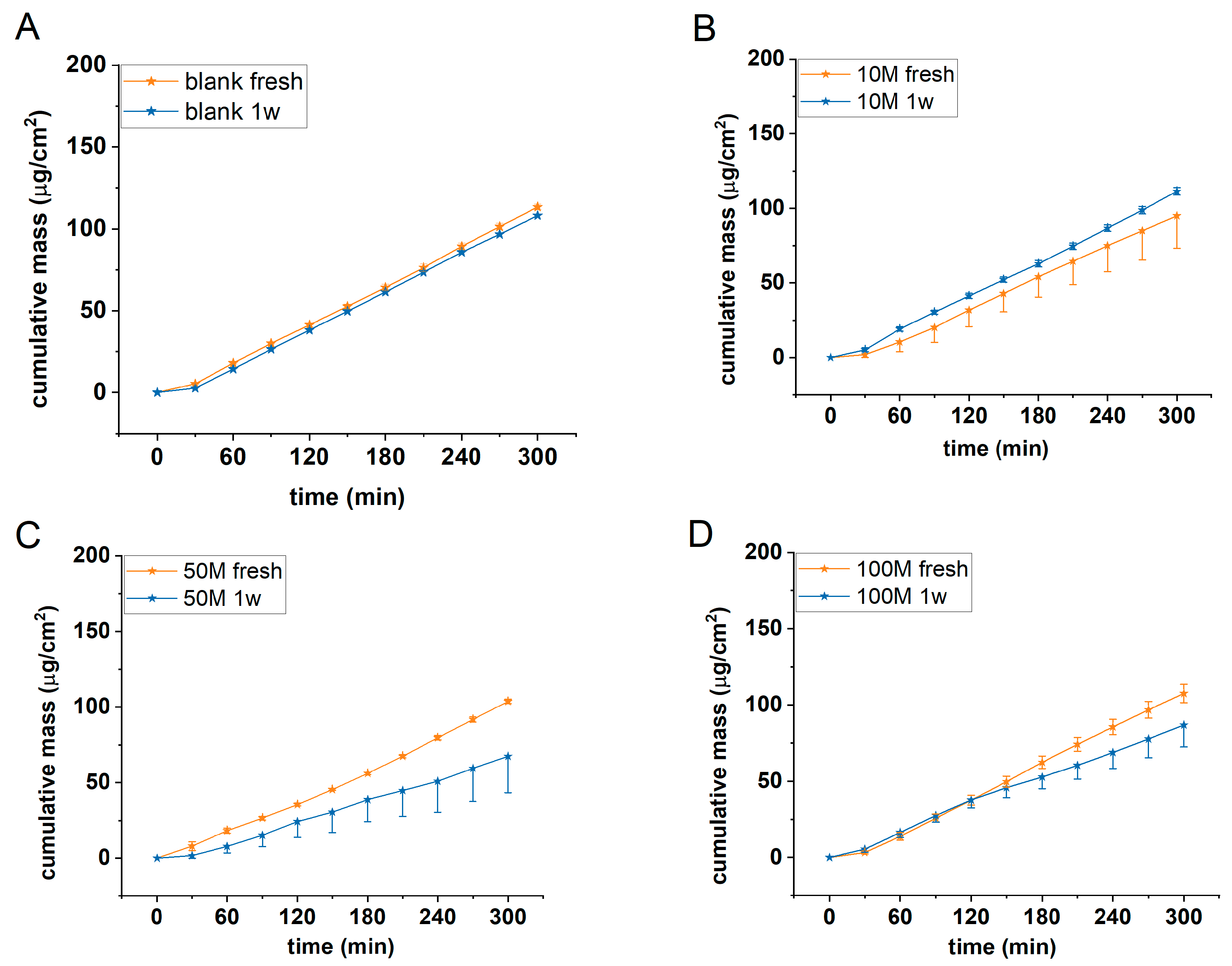

3.4. Cell Number Optimization

In a first series of experiments the optimum cell concentration was searched in alginate scaffolds using HaCaT cells. Acellular (blank) and 10-50 and 100x10

6/mL cell containing alginate discs were tested for permeability using 2% caffeine cream as a model formulation. The experiments were performed in microfluidic diffusion chamber in freshly prepared discs and in discs after one week of cell maturation. Results are presented in

Figure 4.

Based on our results it was concluded that the barrier function of the cell containing scaffolds was the strongest in case of 50M/mL cell concentration and in case of 1 week of maturation. The permeability of the scaffolds with smaller (10 M/mL) or higher (100 M/mL) cell number was higher and comparable with the blank alginate scaffolds.

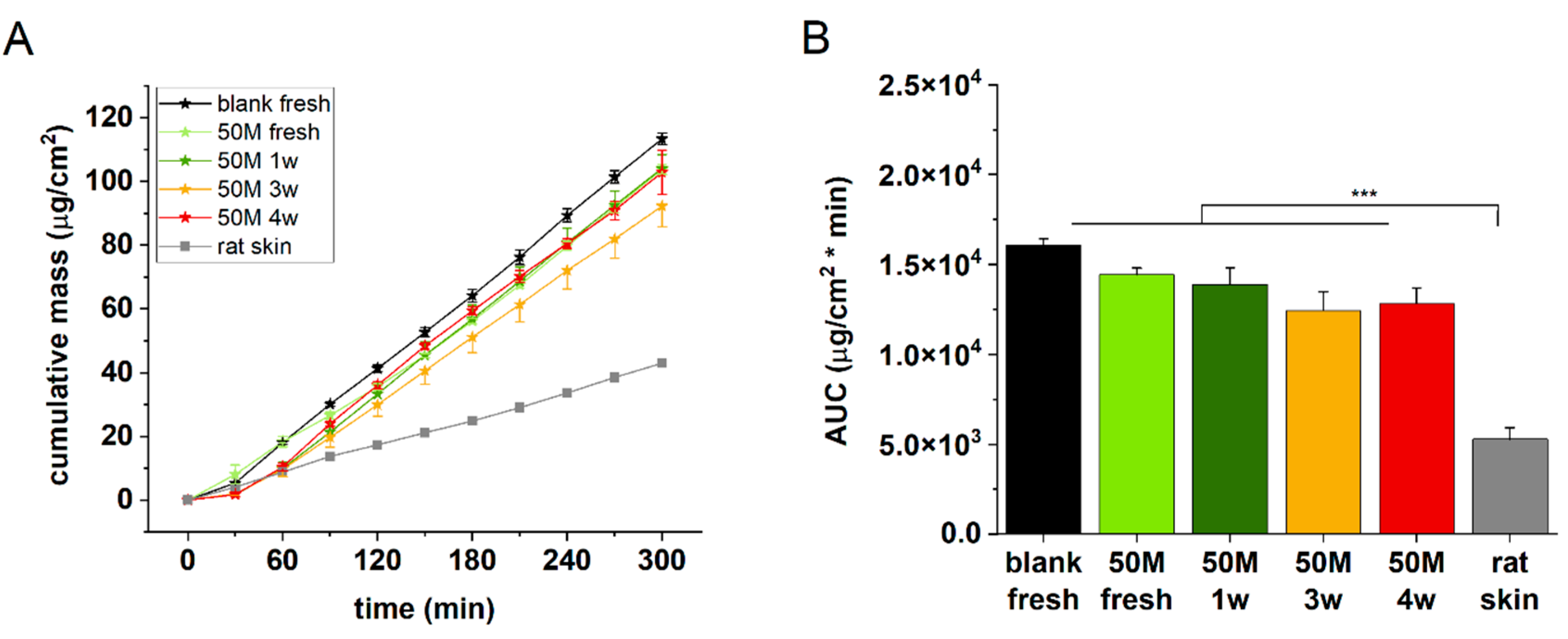

3.5. Incubation Time Selection

To create better cell-cell interactions and therefore more relevant barrier function in the artificial epidermal tissue in the next experiments extended incubation times were tested. Freshly prepared, and 1-3 and 4 weeks maturated discs containing 50M/mL HaCaT cells were examined for permeability in comparison with acellular alginate and ex vivo rat skin. The best barrier function, as it was expected could be detected for the natural excised skin (

Figure 5 A and B), and it was followed by the 3 and 4 weeks incubated cell containing alginates. Based on these findings the next studies were performed after 3 weeks of maturation with 50 M/mL cell containing alginate discs.

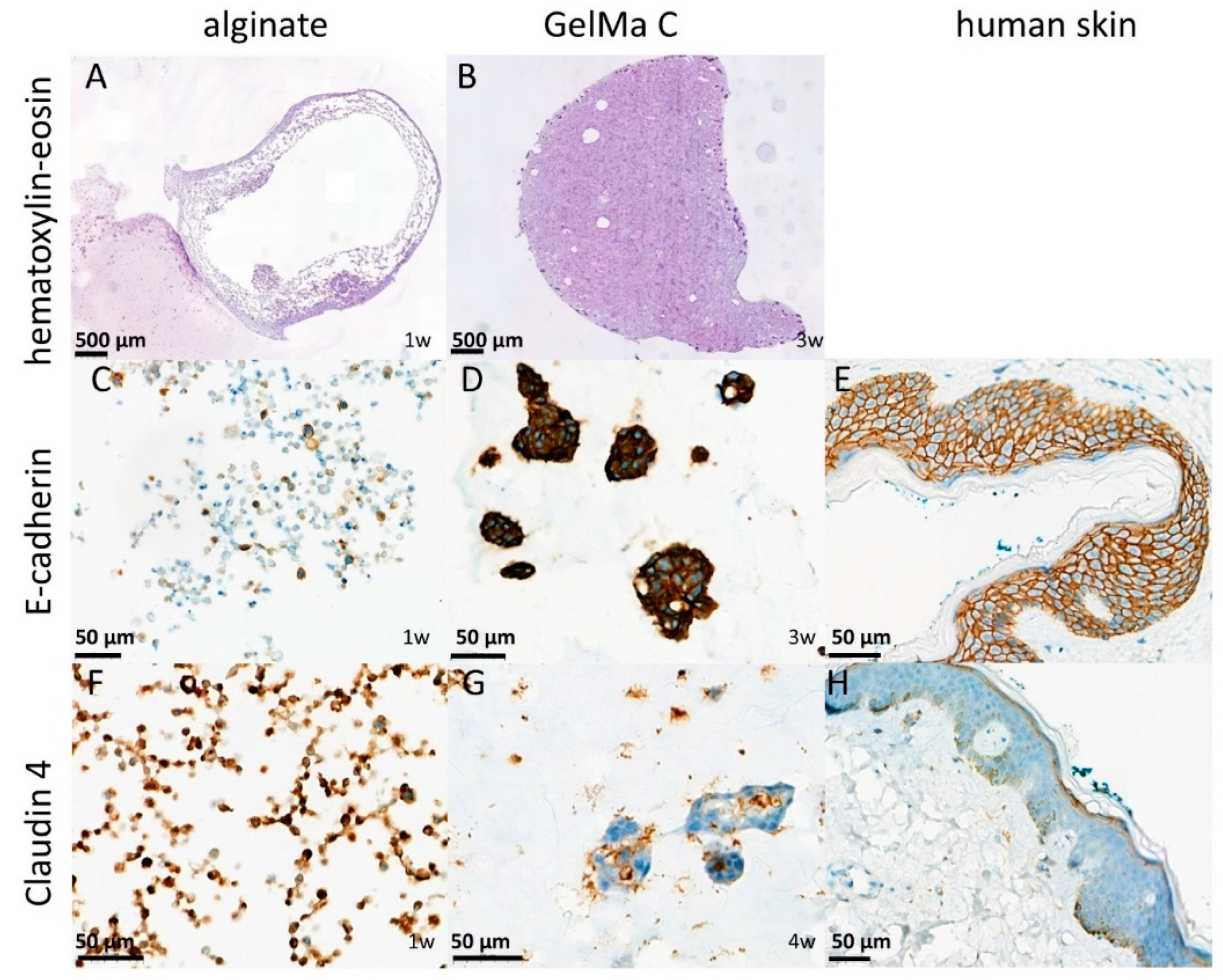

3.6. Histological and Immunohistochemical Analysis of Cell Containing Scaffolds

To confirm the results of functional investigation the alginate and GelMA C scaffolds were also studied for morphology using classical histology (HE staining) [

33] and for evaluation of the cell-cell interactions and level of tissue-like formation E-cadherin and Claudin 4 immunohistochemistry were applied on the sections from the paraffin embedded discs. E-cadherin is a transmembrane glycoprotein which connects epithelial cells together at adherens junctions, while Claudin 4, a transmembrane protein, is located in the tight junctions between the neighboring cells. Both proteins are the markers of cell-cell connections. As it is shown on

Figure 6 panel A and B the cells were able to survive the 1 week of incubation only at the marginal zone of the alginate discs indicating that not enough oxygen and nutrient were available in the core, while in GelMA C scaffolds a better cell distribution can be observed. These findings can be explained by the different matrix structure of the two hydrogels, the higher viscosity of the GelMA C and the better adherence and biocompatibility of this bioink.

Figure 6 panel C and D show that E-cadherin, a marker of cellular connections, was more prominent in GelMA C scaffold, where the keratinocytes were able to form aggregates and functional units within the bioink, contrary to alginate, where the cells remained separately without any visible connections.

In case of Claudin 4 the junctional connections were visualized in

Figure 6 panel F and G where again the GelMA C bioink showed better matrix environment for the tissue formation and cellular connectivity for HaCaT cells.

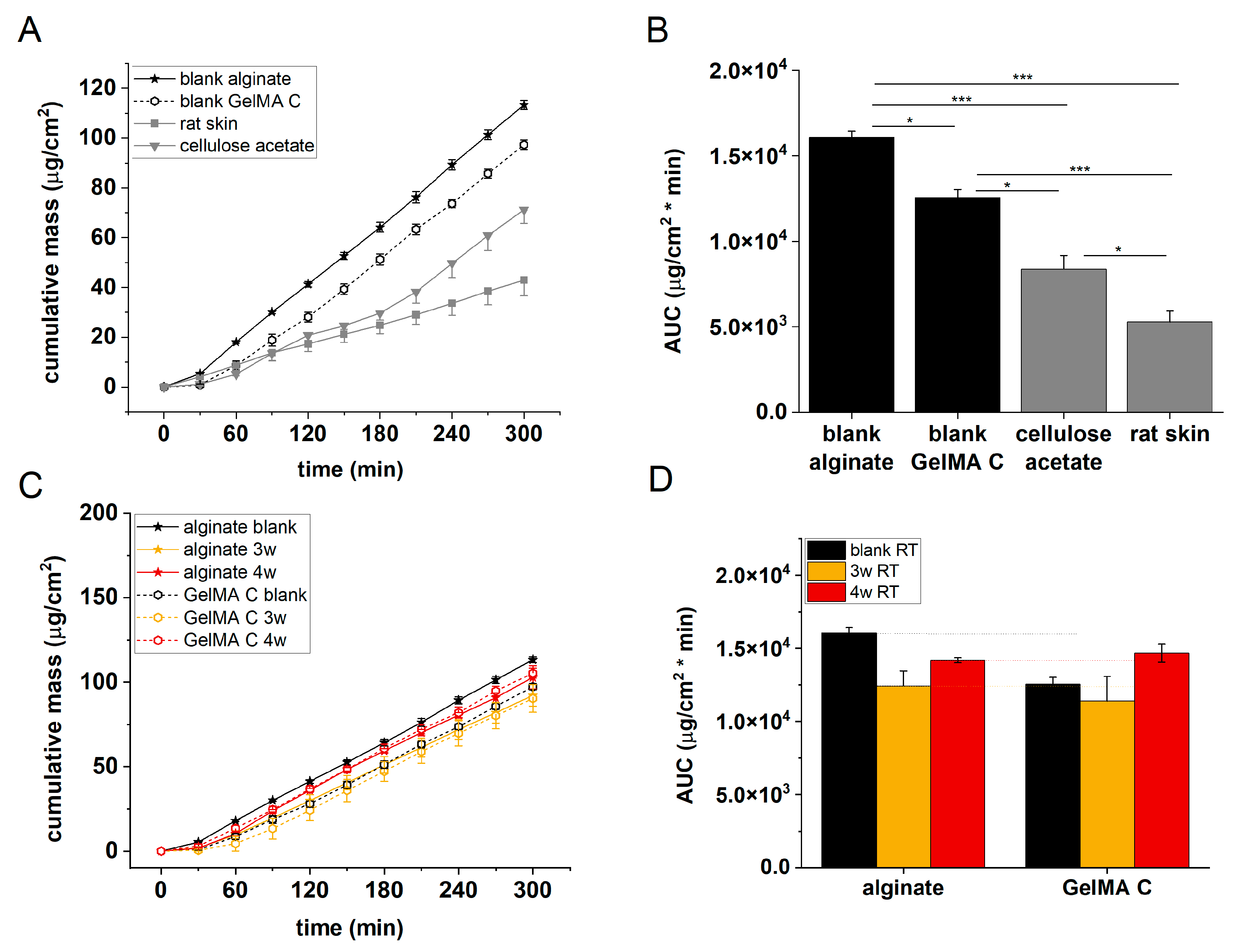

3.7. Permeability Test in Alginate and GelMa C Scaffolds

The permeability of acellular alginate and GelMA C scaffolds, cellulose-acetate membrane and excised rat skins was tested in microfluidic diffusion chambers. As it is seen in

Figure 7, the penetration order of caffeine was the following: alginate > GelMA C > cellulose-acetate membrane > rat skin. This observation is in accordance with the histological and immunohistochemical results which showed different distribution and functional organization of the cells within the scaffolds. In alginate there was only a marginal exhibition of the cells in the discs, while in GelMA C scaffolds the cells were able to penetrate to the central core of the discs and showed a homogenous distribution within the matrix.

Figure 7 panels C and D show that the barrier function of the cell-containing hydrogels was better after 3 weeks of incubation than after 4 weeks. This suggests that the viability of the cells in the scaffolds is limited, and the longer maturation does not mean better tissue formation.

4. Discussion

In this series of experiments, we focused on the development and optimization of an artificial epidermis and bioink matrix composition that may be suitable for future 3D bioprinting applications. The bioink, which consisted of alginate hydrogel and gelatin (also used in wound dressings), was combined with keratinocyte cells at varying concentrations. After different incubation periods, the resulting tissue-like constructs were analyzed both functionally (via permeability tests) and morphologically (using scanning electron microscopy, classical histology, and immunohistochemistry). Similar studies were also conducted with GelMA C hydrogel, which contained cellulose acetate. The results indicate that, among the three incubation times tested, the 3-week period was the most favorable, with the barrier function being strongest at a concentration of 50 M/mL cells. When comparing the two hydrogels, the GelMA C bioink clearly provided a more beneficial environment for cell maturation and development under the tested conditions than the alginate-based bioink. This suggests that GelMA C's matrix properties offered better support for cell adhesion, intercellular communication, differentiation, and tissue formation in human keratinocytes. However, mechanical properties and the thermo-sensitivity of the artificial tissues were not assessed in this study. The gelation, rheological, mechanical, and biological aspects of a bioprinting solution are all equally important, playing a critical role in ensuring the successful printability, mechanical strength, and biofunctionality of scaffolds [

34]. Gelation at room temperature is essential for potential tissue engineering applications, but it must be controllable to prevent issues during printing [

35]. Rheological properties such as viscosity and shear thinning behavior are also crucial for the printability of a gel or solution. The bioink should have the appropriate viscosity to allow smooth flow with minimal obstruction and sufficient cohesion to prevent breaking during the printing process [

36]. Shear thinning, a characteristic of non-Newtonian fluids, occurs when viscosity decreases under applied shear stress, and shear thinning curves can be extremely helpful in comparing the shear rates of bioinks at similar viscosity levels, helping to select a bioink that extrudes well at lower pressures, ensuring better cell survival [

37]. Temperature and external mechanical stimuli are the main controllable conditions in 3D bioprinting. The mechanical strength of scaffolds also impacts cell survival. Stiffer materials offer less space for cells to move and infiltrate, which could hinder their biofunctionality [

38,

39]. For example, a dense core in alginate discs might limit signal exchange and nutrient diffusion, reducing its regenerative potential [

40,

41]. Biocompatibility, biofunctionality, and biodegradability are crucial factors for bioinks used in 3D bioprinting [

42]. To make meaningful recommendations for 3D bioprinting and tissue engineering of artificial human epidermis based on GelMA C hydrogel and human keratinocytes, further research is required.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing, supervision: F.E., M.V., I.A., A.S.; Investigation, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, text editing: D.K., D.Sz., M.L., T.G., L.J., A.N.; Software, methodology, visualization: D.K.; Resources F.E., I.A., A.S.; project administration: F.E.; funding acquisition.: F.E.; fabrication of skin-on-a-chip devices: M.B.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the TKP2021-EGA-42 grant, funded by the Ministry of Innovation and Technology, Hungary with support from the National Research Development and Innovation Fund under the TKP2021 program. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data connecting to this study are available from the authors for request.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Moxon, T.E.; Li, H.; Lee, M.-Y.; Piechota, P.; Nicol, B.; Pickles, J.; Pendlington, R.; Sorrell, I.; Baltazar, M.T. Application of Physiologically Based Kinetic (PBK) Modelling in the next Generation Risk Assessment of Dermally Applied Consumer Products. Toxicol In Vitro 2020, 63, 104746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riabinin, A.; Pankratova, M.; Rogovaya, O.; Vorotelyak, E.; Terskikh, V.; Vasiliev, A. Ideal Living Skin Equivalents, From Old Technologies and Models to Advanced Ones: The Prospects for an Integrated Approach. BioMed Research International 2024, 2024, 9947692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albanna, M.; Binder, K.W.; Murphy, S.V.; Kim, J.; Qasem, S.A.; Zhao, W.; Tan, J.; El-Amin, I.B.; Dice, D.D.; Marco, J.; et al. In Situ Bioprinting of Autologous Skin Cells Accelerates Wound Healing of Extensive Excisional Full-Thickness Wounds. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mania, S.; Banach-Kopeć, A.; Maciejewska, N.; Czerwiec, K.; Słonimska, P.; Deptuła, M.; Baczyński-Keller, J.; Pikuła, M.; Sachadyn, P.; Tylingo, R. From Bioink to Tissue: Exploring Chitosan-Agarose Composite in the Context of Printability and Cellular Behaviour. Molecules 2024, 29, 4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, R.; Kasoju, N.; Raju, R.; Geevarghese, R.; Gauthaman, A.; Bhatt, A. Exploring the Potential of Alginate-Gelatin-Diethylaminoethyl Cellulose-Fibrinogen Based Bioink for 3D Bioprinting of Skin Tissue Constructs. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications 2022, 3, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukelis, K.; Koutsomarkos, N.; Mikos, A.G.; Chatzinikolaidou, M. Advances in 3D Bioprinting for Regenerative Medicine Applications. Regenerative Biomaterials 2024, 11, rbae033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyström, A.; Bruckner-Tuderman, L. Matrix Molecules and Skin Biology. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2019, 89, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonani, W.; Cagol, N.; Maniglio, D. Chun, H.J., Reis, R.L., Motta, A., Khang, G., Eds.; Alginate Hydrogels: A Tool for 3D Cell Encapsulation, Tissue Engineering, and Biofabrication. In Biomimicked Biomaterials: Advances in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine; Springer: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 9789811532627. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.; Zuo, Y.; Wu, E.; Huang, L.; Qian, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z. Highly Biocompatible, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Gelatin Methacrylate/Alginate - Tannin Hydrogels for Wound Healing. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 279, 135417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raucci, M.G.; D’Amora, U.; Ronca, A.; Demitri, C.; Ambrosio, L. Bioactivation Routes of Gelatin-Based Scaffolds to Enhance at Nanoscale Level Bone Tissue Regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasekharan, L.T.; Raju, R.; Kumar, S.; Geevarghese, R.; Nair, R.P.; Kasoju, N.; Bhatt, A. Biofabrication of Skin Tissue Constructs Using Alginate, Gelatin and Diethylaminoethyl Cellulose Bioink. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 189, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seok, J.M.; Ahn, M.; Kim, D.; Lee, J.-S.; Lee, D.; Choi, M.-J.; Yeo, S.J.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, K.; Kim, B.S.; et al. Decellularized Matrix Bioink with Gelatin Methacrylate for Simultaneous Improvements in Printability and Biofunctionality. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 262, 130194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Jorgensen, A.M.; Yang, Y.; Jin, Q.; Zhang, G.; Cao, G.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Ju, J.; et al. Bioprinting a Skin Patch with Dual-Crosslinked Gelatin (GelMA) and Silk Fibroin (SilMA): An Approach to Accelerating Cutaneous Wound Healing. Materials Today Bio 2023, 18, 100550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, R.; Cui, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Z.; Weng, T.; Xia, S.; Yu, M.; Zhang, W.; Shao, J.; Yang, M.; et al. Three-Dimensional Bioprinting of a Full-Thickness Functional Skin Model Using Acellular Dermal Matrix and Gelatin Methacrylamide Bioink. Acta Biomater 2021, 131, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piao, Y.; You, H.; Xu, T.; Bei, H.-P.; Piwko, I.Z.; Kwan, Y.Y.; Zhao, X. Biomedical Applications of Gelatin Methacryloyl Hydrogels. Engineered Regeneration 2021, 2, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglio, C.G.; Baruffaldi, D.; Pirri, C.F.; Napione, L.; Frascella, F. GelMA Synthesis and Sources Comparison for 3D Multimaterial Bioprinting. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, V.G. Growth and Differentiation of HaCaT Keratinocytes. In Epidermal Cells: Methods and Protocols; Turksen, K., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4939-1224-7. [Google Scholar]

- Du Plessis, L.H.; Gouws, C.; Nieto, D. The Influence of Viscosity of Hydrogels on the Spreading and Migration of Cells in 3D Bioprinted Skin Cancer Models. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyz, C.M.; Kunth, P.W.; Gruber, F.; Kremslehner, C.; Hammers, C.M.; Hundt, J.E. Requisite Instruments for the Establishment of Three-Dimensional Epidermal Human Skin Equivalents—A Methods Review. Experimental Dermatology 2023, 32, 1870–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castilho, A.R.F.; Rosalen, P.L.; Oliveira, M.Y.; Burga-Sánchez, J.; Duarte, S.; Murata, R.M.; Rontani, R.M.P. Bioactive Compounds Enhance the Biocompatibility and the Physical Properties of a Glass Ionomer Cement. Journal of Functional Biomaterials 2024, 15, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castilho, A.R.F.; Rosalen, P.; Oliveira, M.; Sánchez, J.; Duarte, S.; Murata, R. Cytotoxicity and Physical Properties of Glass Ionomer Cement Containing Flavonoids IADR Abstract Archives. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 IADR/AADR/CADR General Session; , Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2019; p. 2121.

- Orellana, E.A.; Kasinski, A.L. Sulforhodamine B (SRB) Assay in Cell Culture to Investigate Cell Proliferation. Bio Protoc 2016, 6, e1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweinitzer, S.; Kadousaraei, M.J.; Aydin, M.S.; Mustafa, K.; Rashad, A. Measuring Cell Proliferation in Bioprinting Research. Biomed. Mater. 2024, 19, 031001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, D.; Dhinakaran, S.; Pandey, D.; Laki, A.J.; Laki, M.; Sztankovics, D.; Lengyel, M.; Vrábel, J.; Naszlady, M.B.; Sebestyén, A.; et al. Fluid Dynamics Optimization of Microfluidic Diffusion Systems for Assessment of Transdermal Drug Delivery: An Experimental and Simulation Study. Scientia Pharmaceutica 2024, 92, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Send a Question to the European Medicines Agency | European Medicines Agency. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/about-us/contacts-european-medicines-agency/send-question-european-medicines-agency (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Lukács, B.; Bajza, Á.; Kocsis, D.; Csorba, A.; Antal, I.; Iván, K.; Laki, A.J.; Erdő, F. Skin-on-a-Chip Device for Ex Vivo Monitoring of Transdermal Delivery of Drugs-Design, Fabrication, and Testing. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, E445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajza, Á.; Kocsis, D.; Berezvai, O.; Laki, A.J.; Lukács, B.; Imre, T.; Iván, K.; Szabó, P.; Erdő, F. Verification of P-Glycoprotein Function at the Dermal Barrier in Diffusion Cells and Dynamic “Skin-On-A-Chip” Microfluidic Device. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, E804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga-Medveczky, Z.; Kocsis, D.; Naszlady, M.B.; Fónagy, K.; Erdő, F. Skin-on-a-Chip Technology for Testing Transdermal Drug Delivery-Starting Points and Recent Developments. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, M.; Faraj, M.; Jaffa, M.A.; Jelwan, J.; Aldeen, K.S.; Hassan, N.; Mhanna, R.; Jaffa, A.A. Development of Alginate and Alginate Sulfate/Polycaprolactone Nanoparticles for Growth Factor Delivery in Wound Healing Therapy. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2024, 175, 116750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapani, A.; Corbo, F.; Stefàno, E.; Capobianco, L.; Muscella, A.; Marsigliante, S.; Cricenti, A.; Luce, M.; Becerril, D.; Bellucci, S. Oxidized Alginate Dopamine Conjugate: A Study to Gain Insight into Cell/Particle Interactions. Journal of Functional Biomaterials 2022, 13, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, D.C.; Carbunaru, V.; Moldovan, C.A.; Lascar, I.; Dontu, O.; Ristoiu, V.; Gheorghe, R.; Oproiu, A.M.; Firtat, B.; Franti, E.; et al. Biocompatibility Analysis of GelMa Hydrogel and Silastic RTV 9161 Elastomer for Encapsulation of Electronic Devices for Subdermal Implantable Devices. Coatings 2023, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Vicent, A.; Tuñón-Molina, A.; Bakshi, H.; Sabater i Serra, R.; Alfagih, I.M.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Serrano-Aroca, Á. Biocompatible Alginate Film Crosslinked with Ca2+ and Zn2+ Possesses Antibacterial, Antiviral, and Anticancer Activities. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 24396–24405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzyk, A.; Szumera-Ciećkiewicz, A.; Miłoszewska, J.; Chechlińska, M. 3D Modeling of Normal Skin and Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. A Comparative Study in 2D Cultures, Spheroids, and 3D Bioprinted Systems. Biofabrication 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gungor-Ozkerim, P.S.; Inci, I.; Zhang, Y.S.; Khademhosseini, A.; Dokmeci, M.R. Bioinks for 3D Bioprinting: An Overview. Biomater Sci 2018, 6, 915–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutz, A.L.; Lewis, P.L.; Shah, R.N. Toward Next-Generation Bioinks: Tuning Material Properties Pre- and Post-Printing to Optimize Cell Viability. MRS Bulletin 2017, 42, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölzl, K.; Lin, S.; Tytgat, L.; Van Vlierberghe, S.; Gu, L.; Ovsianikov, A. Bioink Properties before, during and after 3D Bioprinting. Biofabrication 2016, 8, 032002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulik, J.; Salehi, S.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Schrüfer, S.; Schubert, D.W.; Arkudas, A.; Kengelbach-Weigand, A.; Horch, R.E.; Schmid, R. Comparison of the Behavior of 3D-Printed Endothelial Cells in Different Bioinks. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopin-Doroteo, M.; Mandujano-Tinoco, E.A.; Krötzsch, E. Tailoring of the Rheological Properties of Bioinks to Improve Bioprinting and Bioassembly for Tissue Replacement. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj 2021, 1865, 129782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, A.; Levato, R.; D’Este, M.; Piluso, S.; Eglin, D.; Malda, J. Printability and Shape Fidelity of Bioinks in 3D Bioprinting. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 11028–11055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimene, D.; Kaunas, R.; Gaharwar, A.K. Hydrogel Bioink Reinforcement for Additive Manufacturing: A Focused Review of Emerging Strategies. Advanced Materials 2020, 32, 1902026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.; Thayer, P.; Martinez, H.; Gatenholm, E.; Khademhosseini, A. A Perspective on the Physical, Mechanical and Biological Specifications of Bioinks and the Development of Functional Tissues in 3D Bioprinting. Bioprinting 2018, 9, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, S.; Davoodi, P.; Vijayavenkataraman, S.; Teoh, J.H.; Thamizhchelvan, A.M.; Robinson, K.S.; Wu, B.; Fuh, J.Y.H.; DiColandrea, T.; Zhao, H.; et al. Optimized Construction of a Full Thickness Human Skin Equivalent Using 3D Bioprinting and a PCL/Collagen Dermal Scaffold. Bioprinting 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Viscosity curves of alginate (▲) and GelMA C (O) gel samples before crosslinking with controlled shear rate (0.1-100 1/s) at 25 °C.

Figure 1.

Viscosity curves of alginate (▲) and GelMA C (O) gel samples before crosslinking with controlled shear rate (0.1-100 1/s) at 25 °C.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscopic images of the surface and cross-sectional view of A, C) alginate and B, D) GelMa C scaffolds after crosslinking.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscopic images of the surface and cross-sectional view of A, C) alginate and B, D) GelMa C scaffolds after crosslinking.

Figure 3.

Effect of diluted hydrogels on cell viability using SRB assay and HaCaT cells (means +/- SD), *:p<0.05, n=2x5.

Figure 3.

Effect of diluted hydrogels on cell viability using SRB assay and HaCaT cells (means +/- SD), *:p<0.05, n=2x5.

Figure 4.

Cumulative mass-time profiles of caffeine permeation through A) acellular, and B) 107/ml, C) 5x107/ml, and D) 108/ml HaCaT cell containing alginate discs at room temperature (RT). n=3. 1w= one-week maturation.

Figure 4.

Cumulative mass-time profiles of caffeine permeation through A) acellular, and B) 107/ml, C) 5x107/ml, and D) 108/ml HaCaT cell containing alginate discs at room temperature (RT). n=3. 1w= one-week maturation.

Figure 5.

A) Cumulative mass-time profiles of caffeine permeation through alginate scaffolds and abdominal rat skins. B) Area under the cumulative mass-time curves. n=3, ***: p<0.001.

Figure 5.

A) Cumulative mass-time profiles of caffeine permeation through alginate scaffolds and abdominal rat skins. B) Area under the cumulative mass-time curves. n=3, ***: p<0.001.

Figure 6.

Histological and immunohistochemical characterization of HaCaT cell containing alginate (A,C,F) and GelMA C (B, D, G) hydrogel scaffolds. Classical histology (HE staining) (A,B) and E-cadherin (C,D,E) and Claudin 4 (E,F,H) immunohistochemistry were applied. For reference and validation of the immunohistochemistry antibodies human skin samples were used in parallel (E,H).

Figure 6.

Histological and immunohistochemical characterization of HaCaT cell containing alginate (A,C,F) and GelMA C (B, D, G) hydrogel scaffolds. Classical histology (HE staining) (A,B) and E-cadherin (C,D,E) and Claudin 4 (E,F,H) immunohistochemistry were applied. For reference and validation of the immunohistochemistry antibodies human skin samples were used in parallel (E,H).

Figure 7.

A, C) Cumulative mass-time profiles of caffeine permeation through cellulose acetate membrane, rat skin, alginate and GelMA C scaffolds. B, D) Area under the cumulative mass-time curves. n=3, ***: p<0.001. 3w: three weeks of maturation, 4w: four weeks of maturation.

Figure 7.

A, C) Cumulative mass-time profiles of caffeine permeation through cellulose acetate membrane, rat skin, alginate and GelMA C scaffolds. B, D) Area under the cumulative mass-time curves. n=3, ***: p<0.001. 3w: three weeks of maturation, 4w: four weeks of maturation.

Table 1.

The final excipient composition of 2% caffeine creams (as it was described earlier by our group [

24]).

Table 1.

The final excipient composition of 2% caffeine creams (as it was described earlier by our group [

24]).

| Excipient |

Concentration (%) |

Function |

Supplier |

| Paraffin oil |

7.7 |

lipophilic base |

Hungaropharma Zrt. Budapest, Hungary |

| Polyoxyethylene sorbitan monostearate (Polysorbate 60) |

1.8 |

hydrophilic emulsifying agent |

Hungaropharma Zrt. Budapest, Hungary |

| White petrolatum |

12.0 |

lipophilic base |

Hungaropharma Zrt. Budapest, Hungary |

| Cetostearyl alcohol |

5.5 |

lipophilic emulsifying agent |

Molar Chemicals Kft, Halásztelek, Hungary |

| Propylene glycol |

14.6 |

antimicrobial agent preservative, stabiliser |

Hungaropharma Zrt. Budapest, Hungary |

| Purified water |

56.4 |

hydrophilic phase |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).