1. Introduction

More and more people around the word use nutritional supplements, particularly to prevent or treat common issues such as fatigue, lack of concentration, vitamin/mineral deficiencies, minor gastroenterological and dermatological disorders, and vaginal irritations. Oral nutritional supplements are also prescribed to address nutrient deficiencies caused by pathologies and to restore the proper development and body functions [

1,

2]. Manufacturers are continuously developing new formulations that vary in their flavouring, content and galenic form to meet emerging market demands, economic and/or regulatory constraints, and to cater to specific populations. Efforts are now focused on improving specificity and efficiency, particularly in formulation to ensure better release control when necessary. However, nutritional supplements are often characterized by taste defects: bitterness, astringency and metallic notes, which constitute a significant technological barrier to consumer acceptance. This can be explained by the presence of nutrients such as vitamins, minerals, and amino acids known to be the source of these negative perceptual sensations [

3]. Since these components are also the active compounds that are in direct contact with the taste detection system in the mouth upon ingestion of the nutritional supplement, a strategy based on substitution to mask these taste defects is not feasible. Therefore, effective masking strategies aimed at reducing taste defects, both at the peripheral and central levels, appear to be the most promising. However, limited data are available regarding the quantitative sensory characteristics of nutritional supplements. Temporal dominance of sensations (TDS) and temporal check-all that-apply (TCATA) methods were selected to characterize the temporal sensory perceptions during the consumption of orally disintegrating tablets with varying galenic forms and flavourings [

4]. Minerals, amino acids and vitamins with bitter properties have been shown to activate one or more of the 25 bitter taste receptors (TAS2Rs) involved in bitter taste detection [

5,

6,

7]. In particular, the human bitter taste detection threshold for four vitamins in aqueous solution - vitamin B1 (thiamine hydrochloride), vitamin B2 (riboflavin phosphate), vitamin B3 (niacinamide), and vitamin B6 (pyridoxine hydrochloride) - which exhibit a strong bitter taste was confronted to their half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) and their cellular bitter taste threshold [

8]. The results suggest that their bitter taste perception can be explained by interaction with TAS2R receptors.

However, qualitative data alone do not allow for the determination of the actual contribution of these perceptions in the genesis of undesirable tastes. Therefore, an accurate quantitative sensory description of the nutritional supplements, particularly regarding taste and aroma characteristics, is necessary before progressing with the development of masking strategies based on flavour perception. Indeed, improving the formulation of supplements through flavouring could enhance their acceptability by users, especially by masking off-flavours through cross-modal perceptual interactions [

9].

The objectives of this work were to accurately determine the nature of these negative perceptual sensations, quantify them, identify their origin, and assess the effect of flavouring on their organoleptic properties.

2. Results

2.1. Sensory Characterisation of the Nutritional Supplements

2.1.1. Orthonasal Olfactory Properties (Smell)

The results of the evaluation of the sensory characteristics by orthonasal perception of the four nutritional supplements are presented in

Table 1. It is noteworthy that the four nutritional supplements CN1, CN2, CN3 and CN4 exhibit distinct olfactory sensory attributes (smell).

Among all the descriptors evaluated, only the sensory attribute ‘chemical orange’ is applicable to CN1. CN2 is significantly characterized by olfactory notes of ‘passion fruit’, ‘exotic fruits’, ‘yellow fruits’ and ‘red fruits’. Citrus olfactory notes evoking a sensation of freshness such as “fresh orange” and “mandarin” are sensory characteristics specific to CN3. Finally, CN4 is characterized by olfactory notes of ‘mature orange’ and ‘passion fruit’.

2.1.2. Retronasal Olfaction

During this tasting phase, which involved the ingestion of the entire product, the panellists were asked to evaluate the intensity of the sensory attributes (

Table 2).

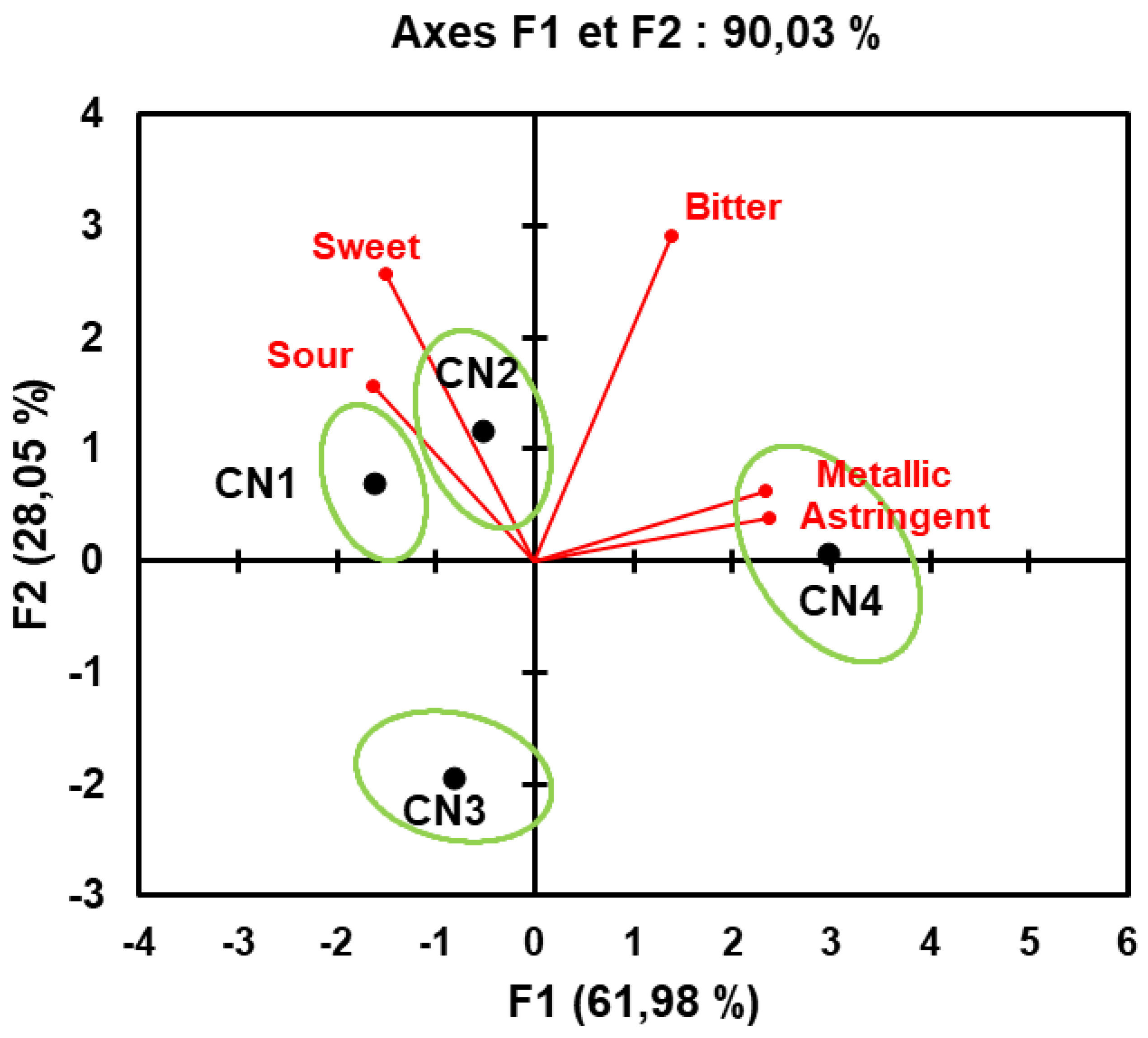

The taste, astringency and metallic perceptions are presented in

Figure 1. The F1 axis is strongly correlated with the sensory attributes ‘metallic’ and ‘astringent’ in its positive part and with ‘sourness’ in its negative part. The F2 axis represents the sensory attributes ‘sweet’ and ‘bitter’. The F1 axis thus separates the products based on their sourness (CN1 and CN2) and on the taste attributes ‘astringency’ and ‘metallic’ (CN4). The F2 axis differentiates nutritional supplements based on perceived bitterness and sweetness. CN2 therefore has a more pronounced bitter taste than CN1 but similar to CN4 in bitterness, with a higher sweetness. CN3 is characterized solely by the absence of bitterness, with no distinct taste attribute.

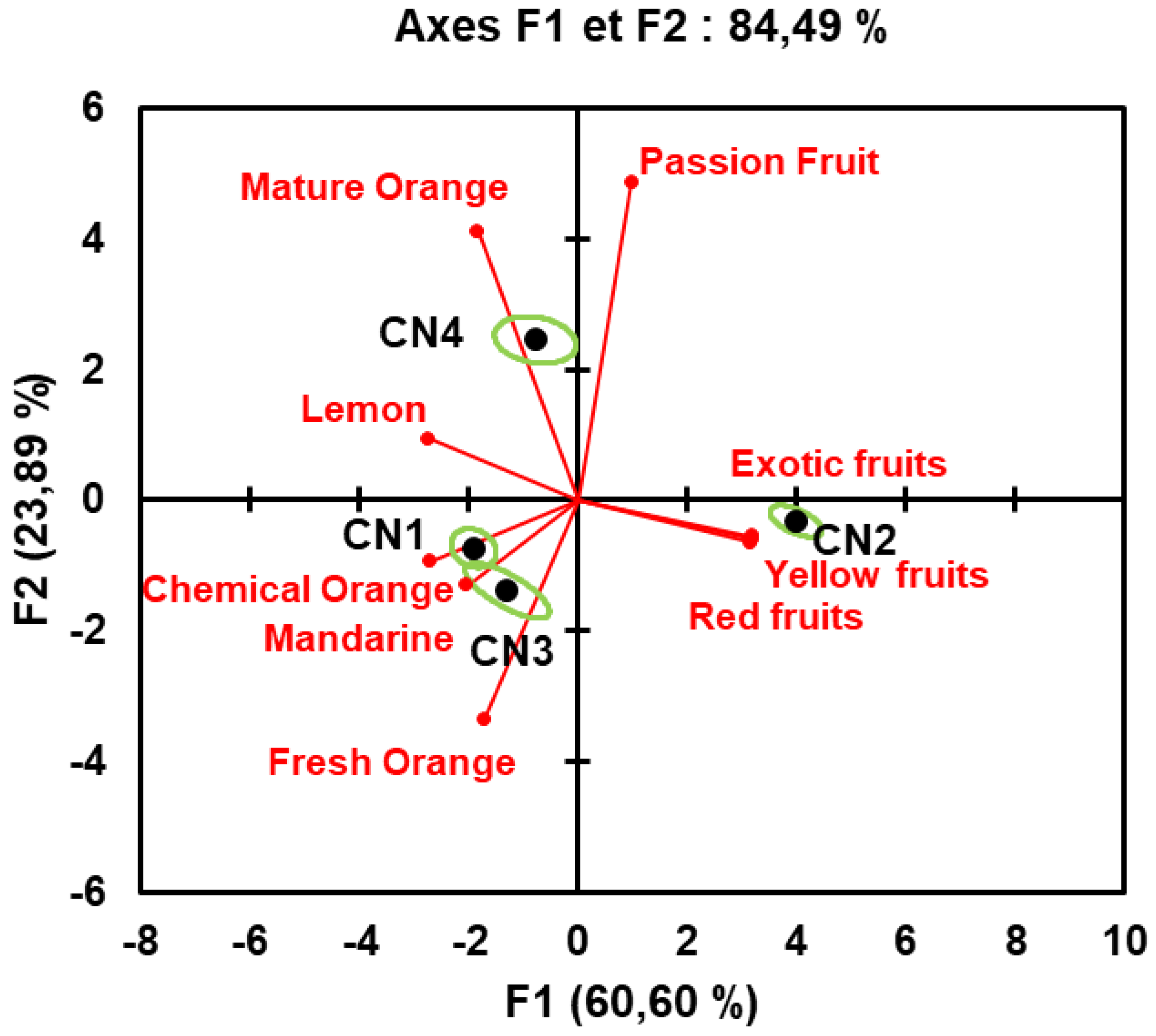

The retronasal aroma perceptions are presented in

Figure 2. The F1 axis differentiates the nutritional supplements based on the attributes ‘red fruits’, ‘exotic fruits’, ‘yellow fruits’ in its positive part, and the attributes ‘chemical orange’, ‘tangerine’ in its negative part. The F2 axis is strongly correlated with the notes of mature orange, passion fruit, and fresh orange. CN1 and CN3 share sensory characteristics, namely ‘chemical orange’ and ‘mandarin’ attributes, but are differentiated by the ‘fresh orange’ attribute, significantly more pronounced for CN3. CN2 and CN4 are characterized by the attributes ‘red fruits’, ‘exotic fruits’, ‘yellow fruits’ for CN2, and ‘mature orange’, ‘passion fruit’ for CN4.

The results of the two-way ANOVA (model: subject + product + subject*product) presented in

Table 2 show significant differences between products. For example, the average intensity of the sensory attribute ‘mature orange’ differs significantly across nutritional supplements.

2.1.3. Aftertaste and Retronasal Odour Persistence

This perception corresponds to the sensations perceived after swallowing the nutritional supplement solutions. These delayed sensory perceptions are commonly referred to as ‘aftertaste’ for taste attributes and ‘retronasal odour persistence’ for aroma attributes.

The average intensity values of each of the aftertastes evaluated for each nutritional supplement are reported in

Table 3. The nutritional supplements exhibit aftertastes of varying intensity, some common and others distinct, with either positive or negative valence. All products are characterized by sour and sweet aftertastes, although significant differences are observed. CN1 and CN4 are characterized by ‘salty’ and ‘metallic’, ‘astringent’ aftertastes, respectively. The ‘bitter’ aftertaste is a sensory attribute present in CN1, CN2 and CN4 with an intensity ranging from 1.2 to 1.7. The relatively low average intensity of this attribute in CN3 appears to be the sole sensory characteristic.

2.2. Effect of Retronasal Odour Perception on Taste Perceptions

The sensory evaluation of the four nutritional supplements was also conducted under blocked airway condition to eliminate the potential effect of retronasal odour perceptions on taste perceptions, both during and after tasting the product. Sensory pre-tests indicated that the odorants at the concentrations used in the nutritional supplements were tasteless (data not shown).

For the four nutritional supplements, significant differences were observed for at least three sensory taste attributes in both evaluation segments (during and after tasting).

The data are summarized in

Table 4. For CN1, CN2 and CN3, flavouring leads to a significant increase in the average intensity of the ‘sweet’ attribute in both evaluation phases, a descriptor with strong positive hedonic valence that is closely correlated with the notion of pleasure. Conversely, the average intensity of less desirable attributes such as ‘bitter’, ‘astringent’ or ‘metallic’ decreases significantly (depending on the nutritional supplement and the evaluation segment considered). The exception is CN4, which follows the opposite trend as its flavouring causes a significant increase in the ‘bitter’ attribute during tasting.

We observed that odourants evoking notes of citrus or exotic fruits enhance the perception of the ‘sour’ aftertaste. The ‘metallic’ attribute, whose average intensity is significantly higher both ‘during tasting’ and ‘after tasting’ for CN4, completely disappears during the sensory evaluation under blocked airway conditions. Although appropriate flavouring can significantly reduce the perceptions of certain attributes, it cannot alone account for the total disappearance of the product’s sensory characteristics. This phenomenon is linked to the volatile properties of the molecules responsible for this sensory quality, which, like aromatic molecules, are perceived by the olfactory organ via the retro-nasal route [

10,

11]. The flavouring of different nutritional supplements does not seem to significantly affect perceptions of the ‘salty’ attribute, except for CN1.

3. Discussion

3.1. Relationship Between the Composition of Nutritional Supplements and Their Sensory Characteristics

Taste sensory perceptions are linked to the composition of these nutritional supplements. Generally speaking, the nutritional supplements studied are ‘sour’ and ‘sweet’, during tasting and for a few seconds after complete ingestion. The observed sourness may be related to the presence of acidic compounds, such as malic acid and citric acid, which are found in the excipient composition of each nutritional supplement. When dissolved in water for consumption, the concentrations of these acids exceed their threshold perception value, estimated around 5 x 10

-6 M. The relative concentration of one acid compared to the other does not appear to affect the perception of sourness or astringency [

12].

We also note the presence of ascorbic acid (vitamin C) as active compound in all four formulations at high concentrations, ranging from 60 to 1000 mg per tablet (

Table 1). The impact of ascorbic acid on the sour perception component of food supplements has already been reported [

3]. The threshold perception value of ascorbic acid is estimated to be in the range of 0.28 – 0.75 mM [

13], and its concentration in the four CN solutions suggests that it is likely also contributing to sourness perception. To our knowledge, no perceptual intramodal interaction between these acids has been reported; however, they likely act in combination to influence the overall sour perception of these nutritional supplements. Furthermore, although citric and malic acids are parts of the excipient fraction of the nutritional supplements, they have been shown to have a positive effect on intragastric urease activity whereas the effect of ascorbic acid on this activity is minimal [

14].

Regarding the sweet perception of these nutritional supplements, its pronounced intensity is associated with the presence of intense sweeteners and bulking agents which serve multiple proposes. These agents have a sweetening power between 0.5 and 0.9 and are incorporated in large quantities, up to 80% of the final mass of the tablet. Although their sweetening power is relatively low, the large quantities used result in a significant sweetening capacity.

The sensory attribute ‘bitter’ was evaluated with an average intensity greater than 1 for the majority of products (CN1, CN2, CN4). This pronounced and persistent bitterness can be attributed to the incorporation of active molecules, either in native or analogous form, such as vitamins, minerals, or plant extracts. The majority of these active compounds are absent in CN3, which differs from the other three nutritional supplements due to its low bitterness. Several water-soluble vitamin analogues from the B vitamin family such as thiamine hydrochloride, riboflavin phosphate, nicotinamide, and pyridoxine hydrochloride are known to be bitter [

3]. The incorporation of magnesium sulphate into CN1 and CN4 could contribute to the enhanced bitterness of these products [

5,

15], as could the manganese sulphate present in CN4.

Some mineral salts used in these nutritional preparations also contribute to other negative sensory qualities. They are responsible, among other factors, for the more marked ‘metallic’ and ‘astringent’ perceptions when CN4 is consumed [

16,

17].

CO2 (and its dissociation metabolites such as carbonic acid) has been identified as responsible for increasing the bitter flavour of carbonated products such as beer [

18,

19], a bitterness also observed in the four nutritional supplements. Additionally, by contributing to a lowering of pH in the oral cavity and altering interactions between salivary proteins, effervescence is associated with the increase in the sensation of astringency [

20], which is present in all of the products studied. Studies have demonstrated the effects of effervescence on sweet and sour perceptions, which depend on the initial intensity values of these tastes within the evaluated product. For low concentrations, effervescence enhances the sour perception of citric or phosphoric acid solutions while helping to mask the sweet perceptions of sucrose or aspartame solutions [

20,

21,

22].

We also observe changes in the relative intensity for certain sensory notes depending on the nutritional supplements during the three oropharyngeal phases, once completely dissolved in water. This is the case of the ‘chemical orange’ attribute, which, compared to CN1, becomes more intense after being placed in the mouth than through simple olfaction. This observation could be explained by differences in the physical processes in the mouth, such as greater retention of the aroma compounds responsible for this note on the oral mucosa or within the matrix. However, it is also noteworthy that during consumption, CN3 and CN4 are less sour and less sweet than CN1, taste attributes that could mask the ‘chemical orange’ note through cross-modal perceptual interactions.

3.2. Perceptual Interactions

These nutritional supplements, when dissolved in water, form a complex mixture of compounds of different perceptual qualities which can interact either at the peripheral level or central level. Citric and malic acids, the major organic acids in fruits and responsible for their sourness [

12,

23,

24], are present in high concentrations in each of the four CN formulations.

The comparison of taste, metallic and astringent intensities, with and without blocking the perception of aromas, reveals numerous effects of retronasal odour perception on these attributes. These effects sometimes differ from one product to another, but they either mask or reinforce taste, astringency and metallic perceptions. However, since retronasal odour perception affects several descriptors simultaneously, the analysis is complex, as we cannot exclude indirect effects due to variations in the intensity of other attributes. For example, for sourness, only CN4 shows a masking effect of this taste through the retronasal odour perception. Interestingly, we also observe an increase of bitterness intensity with the retronasal odour perception. This masking of sourness could also be explained by the more intense perception of bitterness [

25].

Concerning sweetness, the reinforcement of this perception by the retronasal odour perception is explained by cross-modal perceptual interactions with the fruity notes associated with sweetness, as has already been described [

9]. This effect is not observed for CN4, although fruity notes are perceived. This absence can be explained by the presence of a more intense metallic note in CN4, which could either mask or alter the overall fruity note, making it no longer recognizable as such by the panellists. For CN4, the increase in bitterness through the aroma perception could be a consequence of the heightened intensity of metallic perception, which is now recognised as aroma perception [

11,

26,

27]. Overall, we observe a masking effect of retronasal odour perception on unfavourable perceptions such as bitterness and astringency in all four products. This finding is relevant for developing strategies to mask these unfavourable perceptions in such product. However, simultaneously, we note an increase in the intensity of the metallic note, which is also undesirable. One possible explanation is that the masking effect of bitterness and astringency reduces the intensity of these perceptions, thereby allowing the metallic note to become more prominent.

Concerning the ‘after tasting’ segment, we observe, to a lesser extent, both reinforcing and masking effects of sensory attributes by persistent retronasal odour perception. However, in most cases, these effects differ from those observed for the ‘during tasting’ segment. This can be explained by the effects of rinsing with saliva and progressive exhaustion of the ingested material, which lead to changes in the balance and ratio of different stimuli released from the product, depending on their persistence in the oropharyngeal cavity. Moreover, we consistently observe an enhancement of the sweet flavour through the retronasal odour perception for all products when tasted without blocking the nasal airway. However, for CN2 and CN3, the strengthening of the sour perception despite the increase in sweet intensity - which typically exerts a masking effect on sourness - could be partially explained by a reduction in bitterness [

25].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Conditions

The room in which the sensory experiments was conducted met the basic requirements outlined by the AFNOR V 09-105 standard: a uniformly lit, well-ventilated space with stable temperature and humidity, and free from noise. Data acquisition was performed using TimeSens sensory analysis software (TimeSens, Dijon, France).

4.2. Products

Four effervescent nutritional supplements named CN1, CN2, CN3 and CN4, provided by BAYER SAS (Global innovation Centre, Gaillard, France), were evaluated.

Table 5 summarizes their composition and flavouring. As excipients, each formulation contains malic and citric acids, sodium carbonate, sucrose, polyols (mannitol, sorbitol, isomalt, maltitol), sweeteners (aspartame, acesulfame potassium, sucralose), antifoaming agents (polysorbate 80, polysorbate 60, sucrose esters) and disintegrants (crospovidone, croscarmellose sodium). The tablets were stored in a designed room with controlled temperature and humidity.

4.3. Sensory Profile Procedure

4.3.1. Recruitment and Selection of the Panel

An ethical committee approved this study (Personal Protection Committee of Rennes—Ouest V, protocol code 2018A01342-53), and all panellists signed an informed consent form. A total of 23 participants (21 women and 2 men) were recruited for the training and sensory analysis sessions (internal panel). During two one-hour sessions, the panellists were assessed on their sensory acuity to identify any potential disorders in taste and/or olfactory perception [

28]. A separate meeting was held to inform panellists about the requirements for participation including interest, motivation, punctuality, and objectivity. After the interpretation of the tests, the 23 candidates met the necessary criteria and thus constituted the panel of expert tasters.

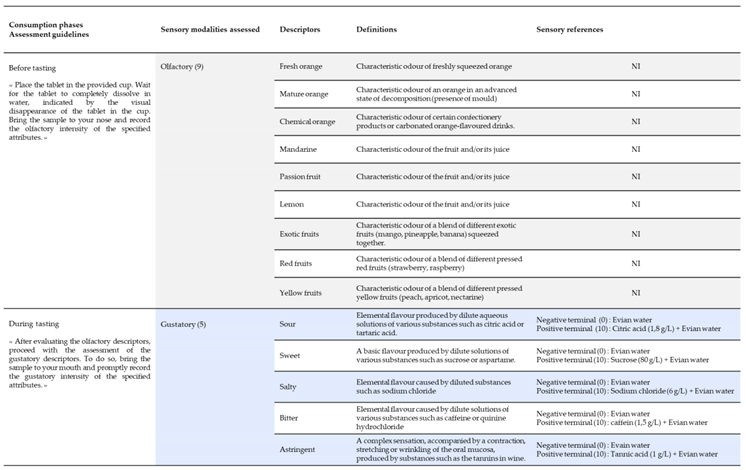

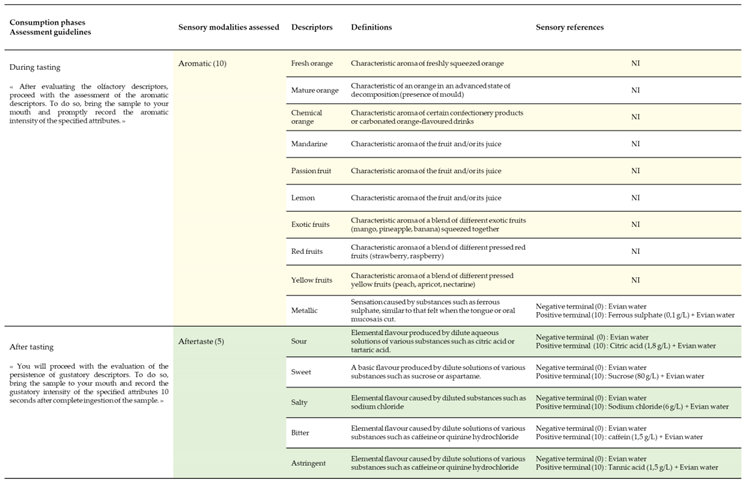

4.3.2. Development of the Descriptor List

The four primary tastes (sour, sweet, salty, bitter) as well as astringency and metallic sensations were added to the list of taste descriptors and trigeminal sensations. The list of olfactory descriptors characteristic of each of the products was compiled following the method described by Moskowitz [

29]. A final list of 15 descriptors (9 olfactory/aromatic attributes and 6 taste/trigeminal attributes), was retained for the sensory profiles of the products. The sensory attributes, along with their definitions and their reference samples, are presented in

Table 6 and

Table 7.

Three distinct phases were considered for sensory evaluation: (i) orthonasal olfactory properties (smell – before tasting), (ii) sensory properties experienced in the mouth (retronasal olfactory properties, taste, and trigeminal sensations – during tasting), and (iii) aftertastes after spitting out the sample (residual retronasal olfactory properties, tastes, and trigeminal sensations – after tasting). The procedure and the attributes evaluated during these three phases are presented in

Table 6 and

Table 7. During a one-hour roundtable, the panellists were introduced to the concepts of taste and aroma, collectively referred to as “flavour”, as well as aftertaste. The sensory systems involved in these perceptions were also explained. To assess the potential gustatory impact of flavouring agents, the evaluations of the “during tasting” and “after tasting” phases were conducted under two conditions: with and without a nose clip, to block or allow airflow through the retronasal route.

4.3.3. Training of the Sensory Panel and Monitoring of Individual Performances

The sensory performance of the panellists was optimized through continuous training over a period of 6 months, with sessions held once a week. Before reaching a consensus on the rating of the various descriptors, it was essential to ensure that these descriptors are memorized by the panellists. Odour and taste recognition tests, based on the list of descriptors were therefore conducted. The tests involved associating randomly presented representative samples of a sensation with the corresponding term in the list of descriptors. Once the sensory descriptors had been memorized and recognized, the focus of learning shifted to evaluate their intensity. Initially, ranking tests were carried out to familiarize the panellists with the intensity evaluation task. The goal was to classify four to five randomly coded samples in either increasing or decreasing order of intensity. Subsequently, the panellists were asked to assign an intensity score to these samples using a 10-cm structured scale, where 1 cm represented 1 point. The scale was anchored at both ends by reference samples: 0 (zero intensity) and 10 (strong intensity).

All of these tests were conducted with and without the nose clip to familiarize the panellists with the use of this device which block the retronasal perception of volatile compounds. At the end of these different training stages, the panellists’ performance was evaluated by conducting the sensory profile of products similar to the nutritional supplements studied. This step aims to assess the discriminatory power of the sensory panel, its repeatability, and the agreement among the different panellists. The sensory profiles of three products were carried out in triplicate and under real sensory evaluation conditions. Data were collected using software dedicated to sensory analysis (TimeSens, Dijon, France) and analysed with the sensory analysis module in the XLSTAT-Sensory statistical software (version 2020.2.3, Addinsoft, Paris, France). The training data were analysed using ANOVA, with the following model: Subject + Product + Session + Subject*Product + Error (random effects of Subject and Session). The results of this analysis indicated that the performance of 16 out of the 23 panellists was satisfactory in terms of discriminative power and repeatability, and that the agreement among these 16 panellists was also good. These 16 panellists were selected to participate in the measurement sessions, while the seven panellists with lower performance were excluded from these sessions [

30].

4.3.4. Measurement Sessions

The sensory evaluation of the four nutritional supplements (CN1, CN2, CN3, and CN4) was conducted with the 16 judges selected after training (15 women and 1 man). Each product was evaluated four times under both conditions (with and without a nose clip). To clarify, the evaluation with a nose clip, which blocks retronasal perception of volatile compounds, aimed to assess the potential gustatory impact of the flavouring agents.

The samples consisted of a quarter of an effervescent tablet diluted in 5 mL of Evian mineral water (Evian, France), in accordance with the supplier's instructions. All samples were presented in white cups, randomly coded with a three-digit number.

For each measurement session, sample evaluation was conducted monadically, with the order of sample presentation following a Williams Latin Square design to balance order and carryover effects (a different Latin square was used for each session). For the evaluation without a nose clip, sensory attributes were assessed in the following order: first, orthonasal olfactory properties (smell), followed by the sensory properties experienced in the mouth (retronasal olfactory properties, taste, and trigeminal sensations), and finally, aftertastes after spitting out the sample (residual retronasal olfactory properties, tastes, and trigeminal sensations).

For the evaluation with a nose clip, the order was as follows: sensory properties in the mouth (flavour and trigeminal sensations), followed by aftertastes (residual flavour and trigeminal sensations).

4.4. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using XLSTAT-Sensory software (version 2020.2.3, Addinsoft, Paris, France). The experimental data were subjected to a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the following model: Subject + Product + Session + Subject*Product + Error (random effects of Subject and Session) to determine the discriminatory power of the different sensory attributes. For each descriptor, post-hoc multiple pairwise comparisons (Tukey HSD, with a significance level set at 5%) were conducted to compare the products pairwise. A normalized principal component analysis (PCA, biplot representation) was performed on matrix correlation of all sensory descriptors to visualise the correlation between the sensory attributes and the nutritional supplements on a single two-dimensional plane. A second two-way ANOVA with the model: Condition + Subject + Product + Session + Condition*Product + Error (random effects of Subject and Session). was conducted to assess the impact of flavouring on taste perceptions, followed by a Tukey test (p < 0.05%).

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to establish the sensory profile of effervescent nutritional supplements dissolved in water by differentiating the three oropharyngeal phases: before ingestion (orthonasal olfactory properties), during ingestion - sensory properties experienced with the product in the mouth (retronasal olfactory properties, taste, and trigeminal sensations), and aftertastes - after spitting out the sample (residual aromas, flavours, and trigeminal sensations). We observed that the nutritional supplements were characterized by very distinct olfactory sensory attributes, regardless of the perception modalities. During ingestion, each nutritional supplement was differentiated from the others by one or more attributes: sweet, bitter, sour, astringent, and metallic. Similarly, differences between products were found in the retronasal perception of odorous attributes. Sour and sweet aftertastes were observed for each product, while the intensity of other attributes—salty, metallic, astringent, and bitter—allowed for further differentiation. Moreover, the retronasal odour perception, due to the flavouring of the products, was found to positively or negatively influence other perceptions, such as taste, metallic, and astringent sensations, during both ingestion and the aftertaste phase. Hypotheses regarding the mechanisms underlying these sensory modifications have been proposed.

Based on these findings, the main perspectives are: (i) understanding these interactions between taste and retronasal odour perceptions could help optimize strategies for masking undesirable tastes, potentially avoiding the use of sweeteners or costly encapsulation techniques, and (ii) reducing the incorporation of substances such as salts and sugars in line with nutritional recommendations.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, T.D. and C.M.; methodology, T.D. and C.M.; formal analysis, T.D.; data curation, T.D.; writing—original draft preparation, T.D and C.S.; writing—review and editing, T.D., C.M., L.B. and C.S.; supervision, C.S. and L.B.; funding acquisition, C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

The PhD of Thomas Delompré was funded by Bayer Healthcare SAS and ANRT (National Agency for Research and Technology, France).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and an ethical committee approved this study (Personal Protection Committee of Rennes—Ouest V, France, protocol code 2018A01342-53).

Informed Consent Statement

An informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

data are unavailable due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Elisabeth Guichard (CSGA, INRAE, Dijon, France) and Catherine Kabaradjian (Bayer Healthcare SAS, Gaillard, France) for their skillful advice in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bolton, J.; Shannon, L.; Smith, V.; Abbott, R.; Bell, S.J.; Stubbs, L.; Slevin, M.L. Comparison of short-term and long-term palatability of six commercially available oral supplements. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 1990, 3, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdale, M.J. Cancer cachexia: metabolic alterations and clinical manifestations. Nutrition 1997, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delompré, T.; Guichard, E.; Briand, L.; Salles, C. Taste perception of nutrients found in nutritional supplements: a review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delompré, T.; Lenoir, L.; Martin, C.; Briand, L.; Salles, C. Characterizing the Dynamic Taste and Retro-Nasal Aroma Properties of Oral Nutritional Supplements Using Temporal Dominance of Sensation and Temporal Check-All-That-Apply Methods. Foods 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrens, M.; Redel, U.; Blank, K.; Meyerhof, W. The human bitter taste receptor TAS2R7 facilitates the detection of bitter salts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Com. 2019, 512, 877–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffitte, A.; Neiers, F.; Briand, L. Characterization of taste compounds: chemical structures and sensory properties. In Flavour; from food to perception, Guichard, E., Le Bon, A.M., Morzel, M., Salles, C., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 154–191.

- Meyerhof, W.; Batram, C.; Kuhn, C.; Brockhoff, A.; Chudoba, E.; Bufe, B.; Appendino, G.; Behrens, M. The molecular receptive ranges of human TAS2R bitter taste receptors. Chem. senses 2010, 35, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delompré, T.; Belloir, C.; Martin, C.; Salles, C.; Briand, L. Detection of Bitterness in Vitamins Is Mediated by the Activation of Bitter Taste Receptors. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinding, C.; Saint-Eve, A.; Thomas-Danguin, T. Chapter 7 - Multimodal sensory interactions. In Flavor: From Food to Behaviors, Wellbeing and Health, Second edition, 2. ed. ed.; Guichard, E., Salles, C., Eds.; Elsevier Ltd.: Cambridge, MA (USA), 2023; pp. 205–231. [Google Scholar]

- Andrea, R. Aroma release during in-mouth process. In Flavour: From food to perception, Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Chichester, West Sussex, UK, 2017; pp. 235–265. [Google Scholar]

- Lawless, H.T.; Schlake, S.; Smythe, J.; Lim, J.Y.; Yang, H.D.; Chapman, K.; Bolton, B. Metallic taste and retronasal smell. Chem. Senses 2004, 29, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowalsky, R.A.; Noble, A.C. Comparison of the effects of concentration, pH and anion species on astringency and sourness of organic acids. Chem. Senses 1998, 23, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulkkinen, E.; Fischer, I.; Laska, M. Sour, but acceptable: Taste responsiveness to five food-associated acids in zoo-housed white-faced sakis,<i> Pithecia</i><i> pithecia</i>. Physiol. Behav. 2024, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, A.; Opekun, A.R.; Abudayyeh, S.; Graham, D.Y. Effect of different organic acids (citric, malic and ascorbic) on intragastric urease activity. Aliment. Pharm. Ther. 2005, 21, 1145–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breslin, P.; Beauchamp, G. Suppression of bitterness by sodium: variation among bitter taste stimuli. Chem. Senses 1995, 20, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Lawless, H.T. Detection thresholds and taste qualities of iron salts. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.H.L.; Lawless, H.T. Descriptive analysis of divalent salts. J. Sens. Stud. 2005, 20, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, R.A.; Hewson, L.; Bealin-Kelly, F.; Hort, J. The interactions of CO 2, ethanol, hop acids and sweetener on flavour perception in a model beer. Chemosens. Percept. 2011, 4, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewson, L.; Hollowood, T.; Chandra, S.; Hort, J. Taste–aroma interactions in a citrus flavoured model beverage system: Similarities and differences between acid and sugar type. Food Qual. Prefer. 2008, 19, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symoneaux, R.; Le Quéré, J.-M.; Baron, A.; Bauduin, R.; Chollet, S. Impact of CO2 and its interaction with the matrix components on sensory perception in model cider. LWT-Food Science Technol. 2015, 63, 886–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Calvé, B.; Goichon, H.; Cayeux, I. CO2 perception and its influence on flavour. In Expression of multidisciplinary flavour science. ed.; Blank, I.; ZHAW, 2010, pp. 55–58.

- Saint-Eve, A.; Déléris, I.; Feron, G.; Ibarra, D.; Guichard, E.; Souchon, I. How trigeminal, taste and aroma perceptions are affected in mint-flavored carbonated beverages. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmasso, J.P.; Wiese, K.L. Sensory and chemical effects of tomato juice acidified with malic and citric acids. J. Food Qual. 1991, 14, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.G.; Pu, D.N.; Zhou, X.W.; Zhang, Y.Y. Recent Progress in the Study of Taste Characteristics and the Nutrition and Health Properties of Organic Acids in Foods. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keast, R.S.J.; Breslin, P.A.S. An overview of binary taste–taste interactions. Food Qual. Prefer. 2003, 14, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubran, M.B.; Lawless, H.T.; Lavin, E.; Acree, T.E. Identification of metallic-smelling 1-octen-3-one and 1-nonen-3-one from solutions of ferrous sulfate. J. Agric.Food Chem. 2005, 53, 8325–8327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ömür-Özbek, P.; Dietrich, A.M.; Duncan, S.E.; Lee, Y. Role of Lipid Oxidation, Chelating Agents, and Antioxidants in Metallic Flavor Development in the Oral Cavity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 2274–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meilgaard, M.C.; Carr, B.T.; Civille, G.V. Sensory evaluation techniques; CRC press: 1999.

- Moskowitz, H.R. Product testing and sensory evaluation of foods: marketing and R&D approaches; Food & Nutrition Press, Inc.: 1983.

- Stone, H.; Sidel, J.L. Introduction to sensory evaluation. Sensory Evaluation Practices (Third Edition). Academic Press, San Diego, 2004; 1–19. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).