1. Introduction

The umami taste is a relatively new primary taste. It was first described by Ikeda in 1909, and only recently specific umami taste receptors were discovered by Nelson et al. in 2002.

The evolutional relevance of the umami taste is demonstrated by the high levels of free glutamate contained in breastfeeding milk (Yamaguchi & Ninomiya, 2000, Zhang et al. 2013), by the fact that human infants are equipped with umami receptors already at birth (Zhang et al. 2013), and by the fact that l-glutamate is a palatable taste for human infants (Steiner, 1987).

Umami sensory quality studies have shown that the taste of MSG is significantly enhanced when combined with nucleotides such as inosine-5’-monophosphate (IMP) and guanosine-5’-monophosphate (GMP) (Yamaguchi, 1998), indicating the epigenetic significance of umami in signaling dietary proteins.

From a health perspective, studies have shown that MSG can help in reducing dietary sodium intake, gaining an advantage for its synergistic effect with saltiness (Halim et al. 2020; Maluly et al. 2017; Mojet et al. 2004; Yamaguchi & Takahashi, 1984), it can enhance satiety in the context of protein intake (Masic & Yeomans, 2013; 2014a;, 2014b), can sustain fullness for a more extended period than other treatments (Anderson et al. 2018), it can control infant feeding (Mennella et al. 2011; Ventura et al. 2012, 2015), and last but not least it can play a crucial role reducing the bitterness typical of green leaves (Kim et al. 2015; Okuno et al. 2020) to beneficial for our health but also have a lower impact on the environment. The evidence mentioned here is only a tiny part of the plethora of scientific publications proving glutamate's benefit in dietary intake.

Umami food palatability enhancement has led to the use of l-glutamate-rich foods for centuries in many cultures, including ancient Greece and Rome, using fermented foods or rich umami vegetables mixed with fish and meats.

Besides being available in natural sources, umami has been made available as monosodium glutamate (MSG), a salt of glutamic acid very similar to cooking salt (Ikeda, 1909). Since then, MSG has been used in food industries, restaurants, and at home to improve the taste and palatability of meals.

Asians, especially Japanese, are familiar with the taste of MSG and regularly add it to their food. On the contrary, despite the long history of experience in combining the umami taste in natural foods and spices, European cultures are less prone to adding pure MSG to their food. Nowadays, both the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)-World Health Organization (WHO) placed MSG in the safest category of food ingredients (Tracy, 2016). Nevertheless, the impression of MSG as a food additive remains (Yeung, 2020).

In a previous study, we investigated how glutamate is perceived in some European samples (Cecchini et al. 2019; Iannilli, 2020). Using a survey, we recruited a large number of adult healthy subjects in three countries representative of northern (Finland), north-central (Germany), and southern Europe (Italy). Surprisingly, 98.4% of Italians and 98.0% of Germans could not label the taste. In Finland, the number of wrong answers decreased to 85%, which remains high compared to the Asian population (Satoh-Kuriwada et al. 2013). Additionally, all groups primarily used the word "salt" to describe the taste of MSG. However, we also observed a notable taste perception and hedonic variation in the response of different countries to the taste of the umami solution.

Building upon the findings of Cecchini et al. (2019) and using a similar protocol, this study aims to gain insight into umami perception through a new methodological approach on a group of Austrians. We plan to analyze the sentiment expressed toward the MSG taste in the verbal descriptors using machine learning for natural language processing (NLP). With this approach we seek to uncover nuanced meanings that may not be captured by traditional rating scales used to measure taste intensity, pleasantness, or other characteristics, as also observed in other research fields, such as pain studies (Williams et al. 2000).

With this in mind, we asked all participants to blind-taste MSG dissolved in water, without any other reference point, and put the perceived taste experience into words. This procedure is known as absolute taste recognition. Later in the protocol, we asked participants to compare the taste of the umami solution to that of a regular salt solution and a plain water solution (relative taste recognition). The relative degree of recognition approach, added to the absolute recognition approach, was chosen to control any effects due to sensory context. Indeed, If the taste recognition pattern obtained in the relative degree of recognition matched the one obtained in the absolute degree of recognition, we could deduce that the measurement was not influenced by sensory context (Kim & O’Mahony, 1998; Cordonnier & Delwiche, 2008). Participants were then asked to express their pleasantness on a continuous scale from -10 to +10 and compare it to a salt solution. We gathered demographics such as age, education level, type of residential area (big/small city or village), salt/sweets/alcohol consumption, recollection of taste preference, and smoking habits. We then conducted a general descriptive analysis and performed a text-semantic-based analysis of the sentences expressed by the entire group as well as any difference based on gender.

Text-sentiment analysis (TSA) is a text mining technique that uses machine learning and natural language processing (NLP) to analyze the emotional tone of the expressed wordings. Although the algorithm has roots in the field of computational linguistics dating back to the '60s (Simmons et al. 1968; Schwarcz, 1969), it has gained significant attention and development with the rise of machine learning techniques in recent years (Mendelsohn et al. 2020). Text-semantic analysis has started to be used in various fields, including healthcare (Elbattah et al. 2021), sociology (Macanovic, 2022), and politics (Watanabe, 2021), to extract insights from textual data and understand emotions and moods in several disciplines, as well as on numerous applications ranging from speech recognition (Weng et al. 2023) to information and data retrieval to natural language processing and machine interpretation (Lan et al. 2021).

Here we utilize TSA to interpret the emotional valence of the sentences used to describe the taste of the MSG solution by the participants. We then establish a taste and perceptual profile of umami taste in the entire group of study and within gender subgroups.

We anticipate that the representation of the umami taste is unfamiliar and distinctive. Our goal is to establish taste and perceptual umami profiles that can aid research in the Western culture's comprehension and acceptance of this exclusive taste.

2. METHOD

2.1. Participants

A dataset of 309 cases was collected based on a previous study (Cecchini et al. 2019). From it, we excluded 76 subjects for the following reasons: 6 exhibited umami ageusia, one exhibited taste distortion in both umami and salt perception, two reported diverse genders, and 67 had lived in Austria ‘less than two years’. We kept all the subjects who answered ‘always’ and ‘most of my life’ at the same question.

After this pruning, we counted a dataset of 233 final cases on which we performed the rest of the analysis.

Participants voluntarily joined in a face-to-face interview at public locations of interest. They received no compensation but freely expressed curiosity in the citizen science survey. The survey was anonymously collected, and information was stored unrelated to identified or identifiable natural persons according to Article 4 (1) of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of the DSG (Austrian Data Protection Act). The study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee of the University of Graz (GZ. 39/100/63 ex 2023/24).

2.2. Procedure

After receiving the information about the study, each participant was given, in a blind mode, a transparent taste solution containing monosodium glutamate (MSG) in water, in an absolute degree of taste recognition modality (i.e. no comparison with other tastes). They were asked to describe their perception of the umami taste in an open-answer modality, using their own words and eventually identify it. Subsequently, a MSG/NaCl/H2O discrimination test was delivered to identify MSG non-tasters (n=6) or other taste problems (n=1) using the protocol described in (Cecchini et al. 2019). After the discrimination test, we also collected data on the recognition of umami solution compared to salt and plain water solutions (relative degree of taste recognition).

All tastants were delivered in liquid solutions with concentrations for MSG and NaCl respectively of 241 mM and 200 mM, as determined in a previous study (Iannilli et al. 2017) and found to be iso-intense and suprathreshold. The solutions were presented in 100 ml dark glass mist spray bottles. Before tasting each solution, the participants rinsed their mouths with water. The MSG/NaCl solutions were rated according to pleasantness (continuous scale of ‘-10’= extremely unpleasant to ‘+10’= extremely pleasant). Moreover, after the discrimination test, the participants were asked to label the tastes just presented (to assign a basic taste if possible).

The following demographics were obtained: age, sex, height, weight, smoking (yes, no), type of residence (countryside, village, city, or big city), whether they had lived abroad for a time longer than two months, or never, habit to add salt to their food (Do you generally add salt to your food at the table, at the time of eating?; four-point Likert scale, 1-never, 2-sometime, 3- most of the time, 4- always), and habit to indulge to sweet treats (How often do you consume sweets on average?; five-point Likert scale, 1-never, 2-once-at-month, 3- once-a-week, 4- more than once a week, 5-everyday), (

Table 1). Finally, we gathered information about participants' liking of the other basic tastes (“How much do you like sweet/salty/sour/bitter/spicy food?”; five-point Likert scale, ranging from “not at all" to "very much"),

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS statistics (IBM Corp. Released 2023. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0.2.0 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). The statistical threshold for significant results was set to p<.05. In instances where multiple comparisons were conducted, we applied appropriate corrections to account for the increased risk of Type I errors. Moreover, when the data did not meet the assumption of normality, we employed non-parametric statistical tests or descriptors that are robust to violations of normality assumptions.

A Text Sentiment Analysis (TSA), which identifies the process of affective and subjective states expressed in a text, was performed on the categorical variable describing the umami taste. The verbal descriptors of the presented taste were classified in terms of emotional expressiveness using the VADER (for Valence Aware Dictionary for sEntiment Reasoning) routine trained on a gold-standard lexicon and a natural language processing (NLP) toolkit (Hutto & Gilbert, 2014). The algorithm is implemented in the Text Analytics Toolbox available in MATLAB R2022b.

3. Results

3.1. MSG Verbal Descriptors

The descriptors associated with the MSG solution were preprocessed, which included lemmatizing text and stopped words (‘and,’ ‘to,’ ‘a’, ‘the’). Finally, adverbs, appositions, and punctuation were removed. We found a total of 547 descriptors between adjectives and nouns, with 152 unique descriptors for the entire sample. Subdividing by gender resulted in a total of 282 verbal descriptors for females, 108 unique, and 265 descriptors for males, 80 unique. The supplementary materials report visual representation of the verbal descriptors in word clouds (SM-Figure 1 for all groups and SM-Figure 2 for the two gender sub-groups).

The most frequent word used by the entire group to describe the MSG solution was the word 'sour,' with word count = 71 (13.0%), followed by 'bitter,' word c.= 51 (9.3%), and then 'salty,' word c.= 47 (8.6%). Only a few recognized the taste of glutamate, word c. = 8 (1.5%), five females and three males. Other attributes with a word count bigger/equal to 10 were 'unpleasant', word c.=20 (3.7%), 'neutral', word count = 17 (3.1%), 'strange', word c. =14 (2.6%), 'sweet' / 'tasteless' / 'lemony' / 'unknown' each with word c.= 13 (2.4%), and 'disgusting' / 'mild', both with word c. =10 (1.8%). It is worth noticing that when all the words with the semantic meaning of sour were counted together, such as 'sour,' 'lemony,' 'tart,' and 'vinegar,' the total word c. accounted for 117, for 21.4% of the entire sample.

Notably, there was also a prevalence of words with meaning associated with the persistent taste sensation of MSG. This sensation was described using terms like 'aftertaste,' 'intense,' and 'long-lasting.'

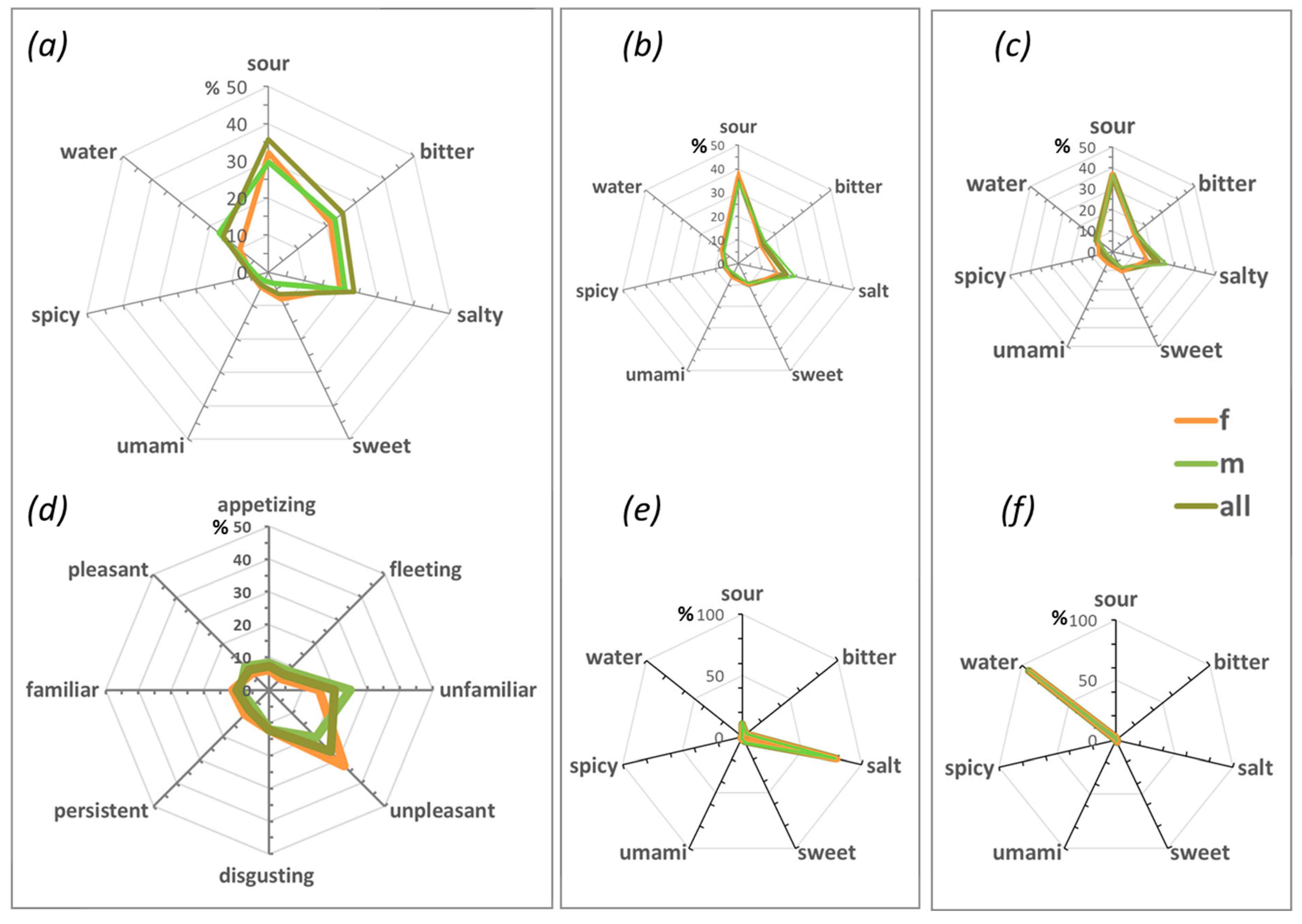

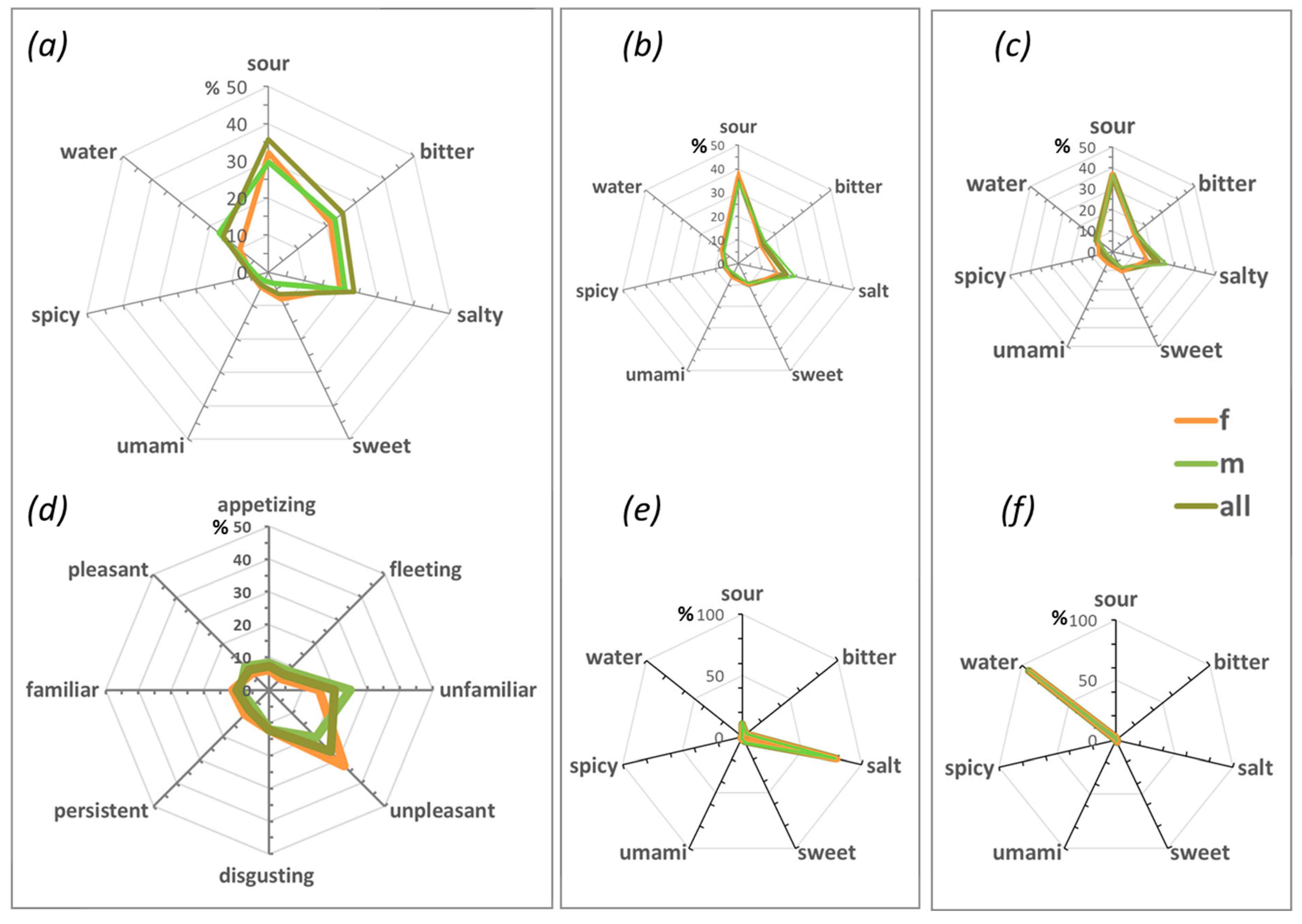

To establish a taste sensory profile of the MSG solution in our tested group, we counted the number of words associated with each of the five descriptors (absolute degree of taste recognition). We then presented the results on a 7-dimensional radar plot, including spicy and water alongside the five primary tastes. The findings are shown in

Figure 1a.

To determine if the taste sensory profile identified from the descriptors was consistent across different sensory contexts, we also created radar charts using MSG relative taste descriptors to salt and water collected after the discrimination tests. They are presented in

Figure 1b,e and in

Figure 1c,f, respectively.

We observed that the words "sour" and "salty" were consistently the most frequently mentioned tastes in both the absolute taste recognition approach and the relative taste recognition method. Surprisingly, umami was rarely mentioned, while salt and pure water were consistently identified. Additionally, we found that different gender subgroups had similar MSG taste sensory profiles compared to the whole group.

For a more general perceptual response we extracted the following four components with their positive and negative connotations from the open-answer descriptions: pleasant (unpleasant), appetizing (disgusting), familiar (unfamiliar), persistent (fleeting). Based on this categorization, we found that the overall perception of the MSG solution was mostly unpleasant (26.6%), unfamiliar (20.0%), and disgusting (12.2%), but also persistent (8.8%) (Figure 5d).

When we examined subgroups based on gender, we noticed a shift in perceptual patterns. Females tended to perceive the solution as more unpleasant (32.5%), while males found it to be more unfamiliar (24.8%). However, the general pattern closely resembled the one observed in the entire group

.

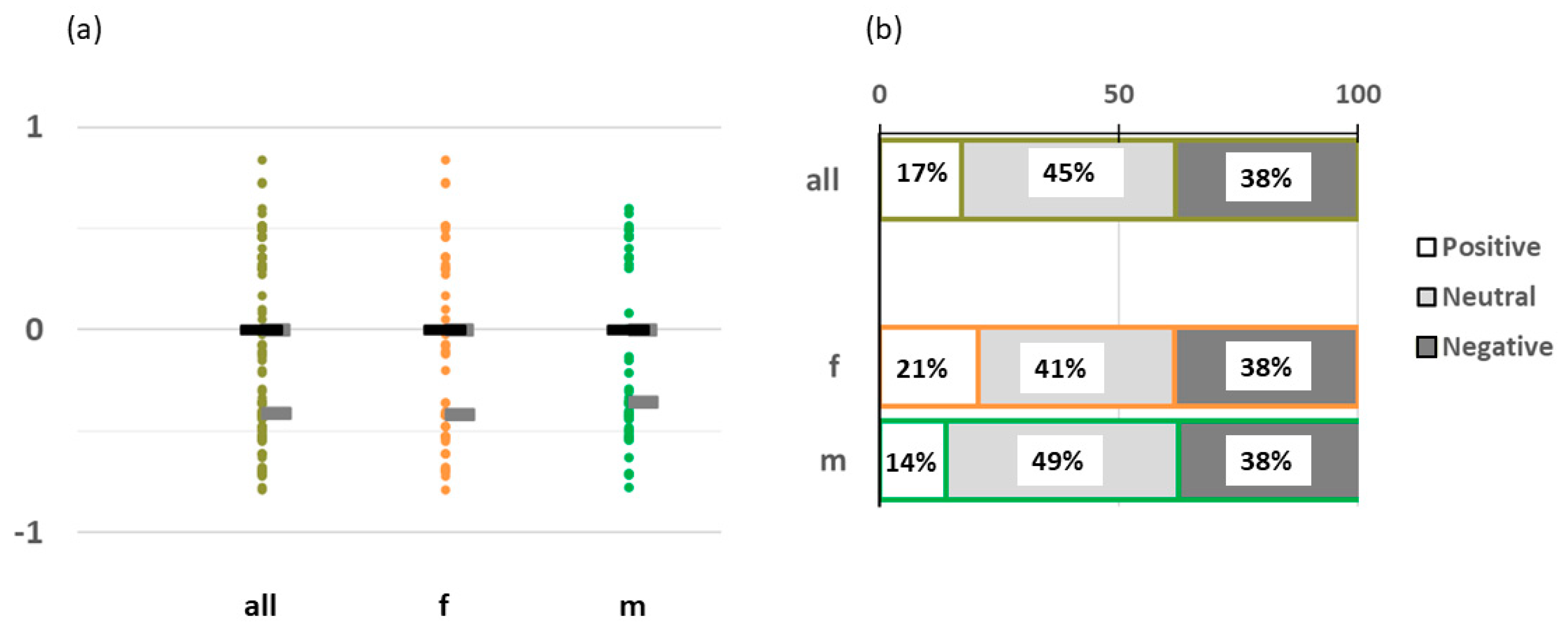

3.2. Text Sentiment-Attribute Analysis

The TSA analysis generated numerical values ranging from -1 (extremely negative meaning of the text) to +1 (extremely positive attribute). The analysis showed that the entire group in the study described the umami taste with an overall neutral meaning (Median=0.00, IQR=-.42), Figure 6a, with no statistical difference between the sex subgroups (p=.807), males (Median)= 0.00, IQR=-.36, females (Median) = 0.00, IQR = -0.42

Then the numerical values were categorized into positive (>0), neutral (=0), and negative (<0) sentiment attributes. According to our findings, the overall sample had 38% expressing a negative, 45% a neutral, and 17% a positive sentiment toward savoring the MSG solution (Figure 6b-top).

No statistically significant difference was noticed by subdividing the entire sample into males and females. (Figure 6b-bottom).

TSA analysis generated numerical values were uncorrelated with education, residence, or experience abroad.

3.3. Pleasantness Ratings

Participants rated the umami solution, M (median) = -1.00, as less pleasant than the salt solution, M=0.00, (Z

(WilcoxonSumRank) = -2.938, p=.003). A non-parametric test of differences among measures of pleasantness was conducted for the subgroup individuated by gender. We observed that only the male groups rated the MSG (M=0.00) less pleasant than the NaCl (M=0.05), (Z(WSR) =-2.545, p<.011) while the female did not (Z(WSR) =-1.578, p<.115). In comparison, males and females rated the NaCl and MSG having similar pleasantness. Data is visualized in the supplementary materials (SM), SM-

Figure 3.

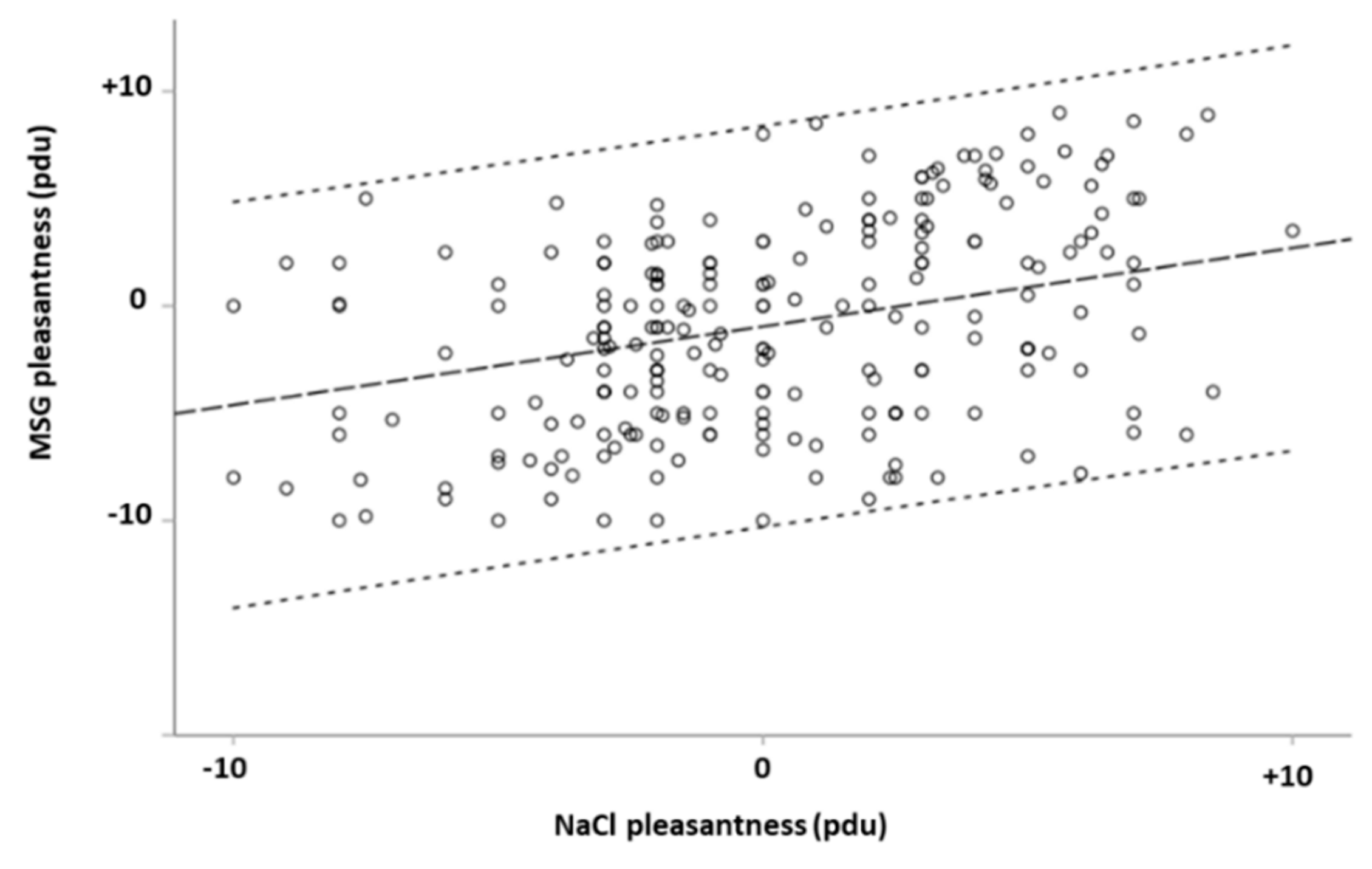

Pleasantness ratings for salt and MSG were positively correlated (rSpearman = 0.316, 95% confidence interval (CI)=0.192÷0.431, p < .001). After dividing the groups by gender, we observed that the correlation between variables remained significant in males (rs=0.419, CI=0.251÷0.536, p<0.001) as well as in females (rs=0.197, CI=0.011÷0.370, p=0.033) subgroup.

We further investigate if the monotonic association identified by the Spearman rho correlation between the NaCl pleasantness ratings and the MSG pleasantness ratings is specifically linear. Linearity was established by visual inspection of both variables on a scatterplot. There was homoscedasticity and normality of the residuals. Then with a regression model we estimate how the pleasantness of one taste predict the other. We found that the NaCl pleasantness rating statistically significantly predicted MSG pleasantness ratings, F(1, 231) = 24.34, p < .001, accounting for 9.5% of the variation in MSG pleasantness with adjusted R

2= 9.1%, a medium size effect according to Cohen (1988) (

Figure 3).

Pleasantness ratings were uncorrelated with education, residence, or experience abroad.

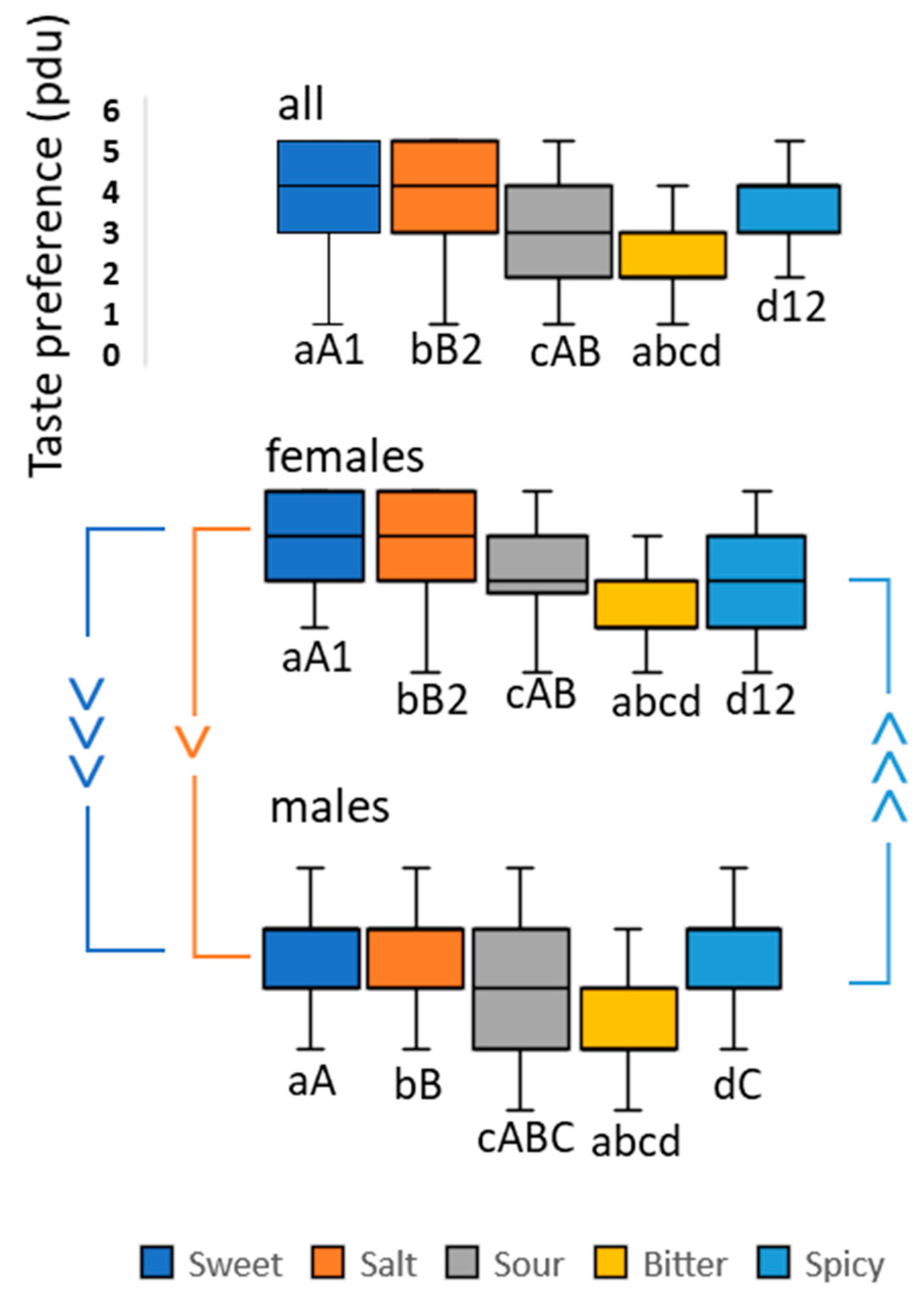

3.4. Recalled Taste Preference

The participants answered the questions ‘How much do you like to eat sweet/salty/sour/bitter/spicy food?’ as follows (Median, IQR): sweet (4.00, 2.00), salty (4.00, 1.50), sour (3.00, 2.00), bitter (2.00, 1.00) and spicy (4.00, 2.00). A Friedman test was conducted to determine whether there were any differences in taste preference scores for sweet, salt, bitter, sour, and spicy. The results revealed a significant difference, with test results of χ2(4)=253.916, p<.001. Post hoc comparison, using Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, indicated that the entire group significantly preferred sweet (p<.001), salt (p<.001), sour (p<.001), and spicy (p<.001) over bitter, sweet (p=.001) and salt (p<.001) over sour, and sweet (p=.004) and salt (p=.001) over spicy (Figure 7).

After splitting the data by gender, we obtained the following group taste preference values, [Median (IQR)], for females: sweet=4.00(1.50), salt = 4.00(2.00), sour= 3.00(2.00), bitter= 2.00(0.50), and spicy= 3.00(2.00), and for males: sweet= 4.00(1.00), salty= 4.00(1.00), sour= 3.00(2.00), bitter=2.00(1.00) and spicy= 4.00(1.00). A Friedman test was conducted to analyze the taste preferences of males and females separately. The male sample showed a statistically significant difference in taste preference (χ2(4) =117.760, p<.001). A post hoc comparison, with Bonferroni correction, indicated that the male group significantly preferred sweet (p<.001), salt (p<.001), sour (p=.005), and spicy (p<.001) to bitter, sweet (p=.007), and salt (p<.001) and spicy (p=.001) to sour. For females, the Friedman test was also significant (χ2(4) =159.124, p<.001). Post hoc comparison, with Bonferroni correction, revealed that the female group preferred sweet (p<.001), salt (p<.001), sour (p<.001), and spicy (p<.001) to bitter, sweet (p<.001) and salt (p<.001) to sour, and finally sweet (p<.001) and salt (p<.001) to spicy. A series of Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted to compare the gender differences in taste preference. The results showed that females preferred sweet (p<.001) and relatively salt (p=.025) compared to males. On the other hand, males preferred spicy (p<.001) over females.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

Our study reveals important insights regarding the sensory perception of umami taste in Austria. The key takeaway is that the group studied is unfamiliar with the umami taste and rarely can recall it by name. Additionally, there are other crucial aspects that should be highlighted:

- (a)

The TSA analysis revealed a neutral sentiment, suggesting a potential for acceptance of MSG if the unfamiliarity barrier can be overcome.

- (b)

Despite the unfamiliarity of the group tested, a stable pattern of umami taste profile emerged, this pattern remained consistent across different sensory contexts, showing that individuals could relate the taste of MSG to known experience.

- (c)

Given the linear relationship between the pleasantness of MSG and salt, we can speculate that MSG, or glutamate, once recognized as an additional independent taste, can be applied in a similar sensory experience to salt.

- (d)

It was observed that the umami, and salty taste, were perceived as unpleasant when evaluated on their own. However, when taste preferences were expressed by recalling real-life experiences, salt taste was not found to be unpleasant. In fact, salt was rated as one of the most preferred tastes, similar to sugar. This tells us that taste recall is heavily influenced by the full eating experience. Since salt and umami are rarely consumed alone, their isolated unpleasantness does not reflect their real-world preference.

- (e)

Finally, we didn't observe significant gender differences in the acceptance and evaluation of umami across gender lines.

4.2. Perception of Umami Solution Through Verbal Descriptors

As part of our study, we asked participants to express their taste perception of the umami solution using verbal descriptors. While numerical scales provide a limited understanding of the nuanced nature of hedonic valence, verbal descriptors can convey more subtle meanings and dimensions of a sensation. Regarding the specific MSG taste, we recorded a wide range of responses, with a certain degree of complexity that we tried to reduce in essential components.

We delineated an MSG perceptual and taste profile that visually represents the overall MSG perception and highlights its characteristics in a multidimensional format (Figure 5).

4.2.1 MSG Taste Profile

Our group emerged with a defined MSG taste profile (Figure 5a), indicating that individuals, despite their general unfamiliarity, could relate the taste of MSG to known tastes. The profile also remained consistent across different sensory contexts, confirming its reliability in the related perception.

At the top of the sensory descriptors, people used 'sour,' 'bitter,' and 'salty.' However, we also found descriptors such as 'sweet,' 'watery,' or 'spicy.' At the same time, the umami word is not mentioned in 98.5% of the cases. Indeed, only eight people out of 233 used the word "umami/glutamate."

The infrequent use of "umami/glutamate" indicates that the study's participants show a semantic and conceptual issue with the umami taste. As a matter of fact, umami is not a new experience in Austrian culinary culture. Foods such as dry-cured pork loin, cured ham, vegetable extracts (broth), stock (in cubes or powder), bouillon, garlic or pumpkin seed oil, as well as meat extracts, are all rich in umami and are considered essential in classical Austrian cuisine. Therefore, Austrians may have an unrecognized semantic issue due to the lack of knowledge about the umami concept as a primary taste. This finding is consistent with our previous research in other European countries (Cecchini et al. 2019; Sing et al. 2010).

The most common taste descriptor of MSG was 'sour.' This contrasts with the most used taste descriptor by people interviewed in Finland, Germany, and Italy, 'salty'(Cecchini et al. 2019). However, when considering the second and third descriptors, the Austrian group was more aligned with the German group, using 'bitter,' 'salty,' and 'sour,' but quite different from the Finnish group, which used terms such as salty, umami and meat/meaty.

The association of sour to describe the MSG solution may be linked to the increased salivation elicited by MSG, which is similar to sour substances. It has been found that salivation induced by MSG ranked second only to that induced by sour taste (Linden, 2006); this similarity may contribute to our subjects' re-evocation of the sour taste experience. Interestingly, this effect can be crucial in the application of treatment for dry mouth, and some studies with positive results are already available (Satoh-Kuriwada & Sasano, 2015)

The recalling of sweet and salty tastes can be attributed, at least in part, to the sodium component of MSG because a low concentration of NaCl can be confused as sweet when subjects are adapted to water or a neutral taste like saliva (Bartshuk, 1974).

Finally, in the MSG taste profile, we also included the taste 'water,' in which we grouped all terms such as 'tasteless,' 'bland,' 'watery,' and 'water. ' It is important here to stress that we ruled out the possibility that the subjects who described the taste as tasteless had umami-ageusia because they could differentiate between the MSG solution and water, as well as the NaCl solution. However, behavioral and psychophysical studies have shown variability in human perception of the umami taste. Aside from umami-ageusia, which indicates a disorder that makes individuals unable to taste umami, Lugaz, Pillias, and Faurion (2002) also classified a category of people indicated as 'hypo-tasters' who could perceive MSG at relatively high concentrations. They estimated that around 10% of the general population are hypo-tasters. In our study, approximately 9.0% (21 subjects) described the MSG solution as a neutral/bland taste, confirming Lugaz and colleagues' findings (Lugaz et al. 2002). The variability in human umami taste perception still needs to be fully understood. Genetic mechanisms may play a role in these variations (Raliou et al. 2009; Shigemura et al. et al. 2009), but factors such as age, body weight (Puputti et al. 2019), or previous exposure and familiarity with umami taste (Singh et al. 2015; Han et al. 2018) may also be influential.

4.2.2. MSG Perceptual Profile

The MSG perceptual profile is mainly characterized by "unpleasant" and "unfamiliar" components (Figure 5d).

The perception of unpleasantness is understandable because tastes are rarely experienced in isolation. An authentic eating experience involves tasting, smelling, seeing, and feeling the texture and temperature of the food (Seo et al. 2013; Bult et al. 2007). Additionally, unlike other taste qualities, relatively pure MSG solutions are not commonly found in nature (Halpern, 2000).

In the MSG perceptual profile, terms such as 'unfamiliar,' 'unknown,' 'difficult to tell,' 'strange,' or 'not sure' are grouped under the 'unfamiliar' category. Here, the lack of experience with the definition of this taste among the entire group has resulted in a reduced association with the foods that contain umami. Despite frequent exposure to foods with umami components in Austrian cuisine, people could not relate them to the MSG taste. In addition to the unfamiliarity with the umami taste, the complexity of this taste may also play a role. When combined with foods, umami can blend in a way that creates a masking effect (Yamaguchi, 1998).

4.2.3 Group Sentiment toward the MSG Solution

Using Text Sentiment Analysis (TSA), we transformed participants' subjective verbal feedback on the MSG solution into numerical values. TSA involves analyzing verbal responses to quantify emotional undertones, assigning to the verbal responses a continuous index from +1, extremely positive, to -1, extremely negative. The analysis revealed that the general sentiment towards the MSG solution was mainly neutral, with a wide variance of sentiments from negative to positive (Figure 6a). The overall neutral sentiments towards the MSG solution are further clarified when we observe the sentiment classification in the overall sample and the males' and females' subgroups (Figure 6b), which was majorly neutral, with percentages of 45%, 49%, and 41%, respectively. This result is a crucial finding because the neutral sentiment suggests a potential for acceptance, provided the corrected information to overcome the unfamiliarity barrier. On the other side, the negative sentiments, a 38% constantly present also in the sex subgroup, implies that there is also a solid negative acceptance toward MSG among the participants, which should be addressed with the correct information. However, considering that the positive sentiments are also relevantly significant, and the neutral is the majority, we believe that with appropriate exposure and education, individuals may grow to appreciate the taste of MSG.

4.3. MSG and NaCl direct comparison

Our study found a significant positive linear relation between the pleasantness of MSG and the salt solution. This implies that the perceived pleasantness of MSG can be predicted based on the more familiar taste of salt.

As a matter of fact, when evaluated independently, salty and umami tastes exhibit several similar properties. They both contain a sodium component; their temporal time-intensity profiles and temporal dominance of sensation are also similar, and the duration of the taste solution increases in a concentration-dependent manner (Rocha et al. 2020). The interaction between salty and umami has been a subject of examination over the years, and industries in food procession have largely used the enhanced palatability form MSG depending on NaCl and vice versa (Jinap et al. 2016; Yamaguchi & Takahashi, 1984). The shared properties of the two tastes may be the driver of the linear and positive relationship found in our data.

This finding bears significant practical implications for manipulating sodium content in food. The saltiness of MSG is approximately 30% that of NaCl by molar sodium concentration and 10% of NaCl by weight (De Souza et al. 2013; Yamaguchi, 1998). By leveraging the synergic actions of the combination of the two, it is possible to obtain a significant salt reduction without compromising palatability (Yamaguchi, 1998).

There were no significant gender differences in the linear relationship between MSG and NaCl pleasantness; both retained the linear relation significantly, indicating that the conclusions drawn are applicable across gender lines.

4.4. Taste Preference Expressed as Recalled Experience

When preferences were expressed based on real-life experiences, salt was not found to be unpleasant, but was rated as one of the most preferred, similar to sugar. This shows how taste perception and the recalling of it are heavily influenced by sensory context. Since salt is rarely consumed alone but combined with other flavors, its isolated unpleasantness does not reflect its real-world preference, suggesting that this can also be the case for umami.

Interestingly, we observed clear sex-depending taste preference in this recalled taste preference. Females tend to favor sweeter and saltier food, while males lean towards spicy food. This is consistent with existing research, which has found that women often consume more sweet or high-calorie meals than men (van Langeveld et al. 2018) and that sweet products are often marketed toward them (Ding et al. 2024). The influence of sex hormones on taste inclination due to a different body composition from males is a plausible explanation (Muscogiuri et al. 2024), but also (Yeomans et al. 2007). Our results also support studies that have observed males prefer spicy food more than females (Alley & Burroughs, 1991), and in some cultural contexts, the consumption of chili peppers has been related to strength, daring, and masculine personality traits (Rozin & Schiller, 1980), but also physiologically as shown in a study linking salivary testosterone and the quantity of hot sauce individuals consumed in a lab meal (Bègue et al. 2015).

4.5. Umami ageusia in the Austrian group

In our original sample of 309 subjects, we observed that 1.9% (6 subjects) were unable to taste umami. This percentage aligns with the findings of Cecchini (2019) when considering the entire group in the study. However, there was a variation in the prevalence of umami non-tasters in the three countries in the study. Specifically, Finland, Germany, and Italy had percentages of non-tasters at 1.3%, 3.3%, and 0.4% respectively. In the Norwegian population, the percentage of non-tasters was 4.6% (Singh et al. 2010), while the first study identifying this taste disorder found a 3.5% prevalence of non-tasters in the French population (Lugaz et al. 2002).

These results indicate that variations in umami perception are more likely due to individual differences rather than differences in the population as a whole. However, the association between umami taste phenotypes and variations in umami taste receptor genes remains unclear at this point, and further studies are needed (Wu et al. 2022).

4.6. Conclusions, Research Challenge and Future Directions

Our study provides valuable insights into the sensory perception of umami, highlighting the potential for broader acceptance and integration of umami as a recognized taste. The work also highlights the importance of context in taste perception.

The participants in this study were from an urban area in central Austria. Therefore, other groups, such as those living in more rural areas, may have different psychological and physiological drivers of dietary patterns. This underscores the need for further research into umami taste perception within various environmental segments. It is also important to acknowledge that our findings should be considered in light of the exploratory nature of the survey.

In conclusion, our study group has identified a clear need for increased awareness of umami, an essential component of taste that can contribute to healthier eating habits. Additionally, our research has revealed a neutral sentiment towards MSG. By increasing exposure and understanding of MSG, we may be able to shift perception towards a more positive reception, mirroring the widespread acceptance of salt.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.I., T.H.; Methodology, E.I.; Software, E.I.; Formal Analysis, E.I.; Investigation, E.I..; Data Curation, E.I., T.H..; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, E.I.; Writing – Review & Editing, T.H.; Funding Acquisition, E.I.

Funding

This work was supported by the International Glutamate Technical Committee (IGTC), located in Washington DC 20045, USA. The funding source was not involved in conducting the research nor in the preparation of the article.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Prof. A. Schienle, Dr. A. Wabnegger and Dr. J. Potoff for their contributions in refining this manuscript and Emilise Pötz, Fariwar Shahidy, Mia Valerie Molitschnig, and Karoline Pölzl for their assistance in collecting the data.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alley, T. R.; Burroughs, W. J. Do men have stronger preferences for hot, unusual, and unfamiliar foods? The Journal of general psychology 1991, 118, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, G. H.; Fabek, H.; Akilen, R.; Chatterjee, D.; Kubant, R. Acute effects of monosodium glutamate addition to whey protein on appetite, food intake, blood glucose, insulin and gut hormones in healthy young men. Appetite 2018, 120, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoshuk, L. M.; Duffy, V. B.; Miller, I. J. PTC/PROP tasting: anatomy, psychophysics, and sex effects. Physiology & behavior 1994, 56, 1165–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Bègue, L.; Bricout, V.; Boudesseul, J.; Shankland, R.; Duke, A. A. Some like it hot: Testosterone predicts laboratory eating behavior of spicy food. Physiology & behavior 2015, 139, 375–377. [Google Scholar]

- Bult, J. H.; Wijk, R. A. De; Hummel, T. Investigations on multimodal sensory integration: Texture, taste, and ortho-and retronasal olfactory stimuli in concert. Neuroscience letters 2007, 411, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchini, M.P.; Knaapila, A.; Hoffmann, E.; Federico, B.; Hummel, T.; Iannilli, E. A cross-cultural survey of umami familiarity in European countries. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 74, 172–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. 1988 Statistical Power Analysis for the Be-havioral Sciences, 2nd edn (Hillsdale, NJ, LawrenceErlbaum).

- Cordonnier, S. M.; Delwiche, J. F. An alternative method for assessing liking: positional relative rating versus the 9-point hedonic scale. Journal of Sensory Studies 2008, 23, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, V. R.; Freire, T. V. M.; Saraiva, C. G.; Carneiro, J. D. D. S.; Pinheiro, A. C. M.; Nunes, C. A. Salt equivalence and temporal dominance of sensations of different sodium chloride substitutes in butter. Journal of Dairy Research 2013, 80, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, S. How brand gender affects consumer preference for sweet food: The role of the association between gender and taste. Psychology & Marketing 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Halim, J.; Bouzari, A.; Felder, D.; Guinard, J. The salt Flip: Sensory mitigation of salt (and sodium) reduction with monosodium glutamate (MSG) in “better-for-you” foods. Journal of Food Science 2020, 85, 2902–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, B. P. Glutamate and the flavor of foods. The Journal of Nutrition 2000, 130, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutto, C.; ilbert. Vader: A parsimonious rule-based model for sentiment analysis of social media text. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 2014, 8, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannilli, E.; Broy, F.; Kunz, S.; Hummel, T. Age-related changes of gustatory function depend on alteration of neuronal circuits. Journal of neuroscience research 2017, 95, 1927–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannilli, E.; Knaapila, A.; Cecchini, M. P.; Hummel, T. Dataset of verbal evaluation of umami taste in Europe. Data in brief 2020, 28, 105102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, K. On a new seasoning. J. Tokyo Chem. Soc 1909, 30, 820–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinap, S.; Hajeb, P.; Karim, R.; Norliana, S.; Yibadatihan, S.; Abdul-Kadir, R. Reduction of sodium content in spicy soups using monosodium glutamate. Food & Nutrition Research 2016, 60, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.-O.; O’Mahony, M. A new approach to category scales of intensity I: Traditional versus rank-rating. Journal of Sensory Studies 1998, 13, 241–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. J.; Son, H. J.; Kim, Y.; Misaka, T.; Rhyu, M. R. Umami–bitter interactions: The suppression of bitterness by umami peptides via human bitter taste receptor. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2015, 456, 586–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugaz, O.; Pillias, A. M.; Faurion, A. A new specific ageusia: Some humans cannot taste L-glutamate. Chemical Senses 2002, 27, 105–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluly, H. D.; Arisseto-Bragotto, A. P.; Reyes, F. G. Monosodium glutamate as a tool to reduce sodium in foodstuffs: Technological and safety aspects. Food science & nutrition 2017, 5, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Mojet, J.; Heidema, J.; Christ-Hazelhof, E. Effect of concentration on taste–taste interactions in foods for elderly and young subjects. Chemical senses 2004, 29, 671–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masic, U.; Yeomans, M. R. Does monosodium glutamate interact with macronutrient composition to influence subsequent appetite? Physiology and Behavior 2013, 116–117, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masic, U.; Yeomans, M. R. Monosodium glutamate delivered in a protein-rich soup improves subsequent energy compensation. Journal of Nutritional Sciences, 2014a, 3, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masic, U.; Yeomans, M. R. Umami flavor enhances appetite but also increases satiety. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2014b, 100, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mennella, J. A.; Ventura, A. K.; Beauchamp, G. K. Differential growth patterns among healthy infants fed protein hydrolysate or cow-milk formulas. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscogiuri, G.; Verde, L.; Vetrani, C.; Barrea, L.; Savastano, S.; Colao, A. Obesity: a gender-view. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 2024, 47, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, G.; Chandrashekar, J.; Hoon, M. A.; Feng, L.; Zhao, G.; Ryba, N. J.; Zuker, C. S. An amino-acid taste receptor. Nature 2002, 416, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuno, T.; Morimoto, S.; Nishikawa, H.; Haraguchi, T.; Kojima, H.; Tsujino, H.; Arisawa, M.; Yamashita, T.; Nishikawa, J.; Yoshida, M.; Habara, M.; Ikezaki, H.; Uchida, T. Bitterness-suppressing effect of umami dipeptides and their constituent amino acids on diphenhydramine: Evaluation by gustatory sensation and taste sensor testing. Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2020, 68, 234–243. [Google Scholar]

- Puputti, S.; Aisala, H.; Hoppu, U.; Sandell, M. Factors explaining individual differences in taste sensitivity and taste modality recognition among Finnish adults. Journal of Sensory Studies 2019, e12506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raliou, M.; Wiencis, A.; Pillias, A.-M.; Planchais, A.; Eloit, C.; Boucher, Y.; Trotier, D.; Montmayeur, J.-P.; Faurion, A. Nonsynonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms in human tas1r1, tas1r3, and mGluR1 and individual taste sensitivity to glutamate. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2009, 90, 789S–99S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, R. A. R.; Ribeiro, M. N.; Silva, G. A.; Rocha, L. C. R.; Pinheiro, A. C. M.; Nunes, C. A.; Carneiro, J.; S, d. D. Temporal profile of flavor enhancers MAG, MSG, GMP, and IMP, and their ability to enhance salty taste, in different reductions of sodium chloride. Journal of Food Science (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.) 2020, 85, 1565–1575. [Google Scholar]

- Rozin, P.; Schiller, D. The nature and acquisition of a preference for chili pepper by humans. Motivation and emotion 1980, 4, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh-Kuriwada, S.; Kawai, M.; Noriakishoji, N.; Sekine, Y.; Uneyama, H.; Sasano, T. Assessment of umami taste sensitivity. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Satoh-Kuriwada, S.; Sasano, T. A remedy for dry mouth using taste stimulation. Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi 2015, 145, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H. S., E. Iannilli, C. Hummel, Y. Okazaki, D. Buschhüter, J. Gerber,... & T. Hummel. 2013. A salty-congruent odor enhances saltiness: Functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Human brain mapping 34: 62-76.

- Singh, P. B.; Schuster, B.; Seo, H. S. Variation in umami taste perception in the German and Norwegian population. European journal of clinical nutrition 2010, 64, 1248–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P. B.; Hummel, T.; Gerber, J. C.; Landis, B. N.; Iannilli, E. Cerebral processing of umami: A pilot study on the effects of familiarity. Brain research 2015, 1614, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner J.E. 1987 What the Infant Can Tell Us about Umami, in Umami: A Basic Taste (Eds.: Y. Kawamura, M. R.Kare), Marcel Dekker, New York 1987: pp. 97 – 123.

- Tracy, S. E. 2016. Delicious: a history of monosodium glutamate and umami, the fifth taste sensation. A thesis for the degree of doctor of philosophy. Department of History, University of Toronto.

- van Langeveld, A. W.; Teo, P. S.; Vries, J. H. de; Feskens, E. J.; Graaf, C. de; Mars, M. Dietary taste patterns by sex and weight status in the Netherlands. British Journal of Nutrition 2018, 119, 1195–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, A. K.; Beauchamp, G. K.; Mennella, J. A. Infant regulation of intake: The effect of free glutamate content in infant formulas. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2012, 95, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, A. K.; Inamdar, L. B.; Mennella, J. A. Consistency in infants’ behavioural signalling of satiation during bottle-feeding. Pediatric Obesity 2015, 10, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, A. C. D. C.; Davies, H. T. O.; Chadury, Y. Simple pain rating scales hide complex idiosyncratic meanings. Pain 2000, 85, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Eldeghaidy, S.; Ayed, C.; Fisk, I. D.; Hewson, L.; Liu, Y. Mechanisms of umami taste perception: From molecular level to brain imaging. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2022, 62, 7015–7024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S. Basic properties of umami and effects on humans. Physiology & Behavior 1998, 49, 833–841. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Ninomiya, K. Umami and food palatability. The Journal of Nutrition 2000, 130 (4S Suppl), 921S–926S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Takahashi, C. Interactions of monosodium glutamate and sodium chloride on saltiness and palatability of a clear soup. Journal of Food Science 1984, 49, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeomans, M. R.; Tepper, B. J.; Rietzschel, J.; Prescott, J. Human hedonic responses to sweetness: role of taste genetics and anatomy. Physiology & behavior, 2007, 91, 264–273. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, J. 2020. MSG in Chinese food isn’t unhealthy—You’re just racist, activists say. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/01/18/asia/chinese-restaurant- syndrome- msg- intl- hnk- scli/index.html.

- Zhang, Z.; Adelman, A. S.; Rai, D.; Boettcher, J.; Lonnerdal, B. Amino acid profiles in term and preterm human milk through lactation: A systematic review. Nutrients 2013, 5, 4800–4821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Radar Charts of MSG Taste (a) and Perceptual Profiles (d). The MSG taste description, whether extracted by the absolute taste recognition (a) or obtained in the relative taste recognition in comparison to salt (b ) or water solution(c), shows a consistent pattern across the entire group (all) and subgroups (m, f). The MSG-taste profile (a), (b), and (c) indicates that Austrians tried to describe the umami taste using a combination of the four basic tastes without using the word umami. On the contrary, the entire group clearly identified salt (e) and water (f). (d) The umami perceptual profile is reported in four dimensions, appetizing (disgusting), pleasant (unpleasant), familiar (unfamiliar) and persistent (fleeting), with opposite valence on the extremities of the axis. The categories were based on the open-answer descriptors. Overall, the entire group described the MSG taste as unpleasant and unfamiliar. In the charts, the entire group is depicted in olive green(all), while the female and male subgroups are shown in orange (f) and green (m), respectively.

Figure 1.

Radar Charts of MSG Taste (a) and Perceptual Profiles (d). The MSG taste description, whether extracted by the absolute taste recognition (a) or obtained in the relative taste recognition in comparison to salt (b ) or water solution(c), shows a consistent pattern across the entire group (all) and subgroups (m, f). The MSG-taste profile (a), (b), and (c) indicates that Austrians tried to describe the umami taste using a combination of the four basic tastes without using the word umami. On the contrary, the entire group clearly identified salt (e) and water (f). (d) The umami perceptual profile is reported in four dimensions, appetizing (disgusting), pleasant (unpleasant), familiar (unfamiliar) and persistent (fleeting), with opposite valence on the extremities of the axis. The categories were based on the open-answer descriptors. Overall, the entire group described the MSG taste as unpleasant and unfamiliar. In the charts, the entire group is depicted in olive green(all), while the female and male subgroups are shown in orange (f) and green (m), respectively.

Figure 2.

Text sentiment analysis (TSA) results. (a) TSA of the phrases pronounced in the open-answer description of the MSG solution. Median (black bar) and IRQ (grey bars) are reported on the points distribution. (b) TSA percentage of the hedonic components: positive (white), neutral (grey), and negative (black). all: entire group, f: females, m: male.

Figure 2.

Text sentiment analysis (TSA) results. (a) TSA of the phrases pronounced in the open-answer description of the MSG solution. Median (black bar) and IRQ (grey bars) are reported on the points distribution. (b) TSA percentage of the hedonic components: positive (white), neutral (grey), and negative (black). all: entire group, f: females, m: male.

Figure 3.

Linear regression analysis of MSG pleasantness as a function of NaCl pleasantness. The dashed line represents the best-fit linear regression model. The area around the regression line delineated by the dotted lines indicates the 95% confidence interval of the predicted MSG pleasantness values based on NaCl pleasantness ratings. The model explains 9.5% of the variance in MSG pleasantness (R² = 0.095), indicating a statistically significant linear relationship (p < 0.001) with coefficient β=.37. pdu: procedure defined unit.

Figure 3.

Linear regression analysis of MSG pleasantness as a function of NaCl pleasantness. The dashed line represents the best-fit linear regression model. The area around the regression line delineated by the dotted lines indicates the 95% confidence interval of the predicted MSG pleasantness values based on NaCl pleasantness ratings. The model explains 9.5% of the variance in MSG pleasantness (R² = 0.095), indicating a statistically significant linear relationship (p < 0.001) with coefficient β=.37. pdu: procedure defined unit.

Figure 4.

Box Plots (median, IQR) of taste preference expressed as recalled experinece on the Likert Scale (0-6) for sweet, salt, sour, bitter, and spicy organized in rows by group (all: entire group), and gender, and in the column by tastes (sweet, salt, sour, bitter and spicy). The statistical significance levels between groups are highlighted with ">" where the angle bracket's opening is in the greater value's direction. Also: “>>>”, “>>”, and “>” indicate respectively p<.001, p<.01, and p<.05. Statistical differences within groups are highlighted by letters/numbers; the same letter/number indicates statistically significant differences.

Figure 4.

Box Plots (median, IQR) of taste preference expressed as recalled experinece on the Likert Scale (0-6) for sweet, salt, sour, bitter, and spicy organized in rows by group (all: entire group), and gender, and in the column by tastes (sweet, salt, sour, bitter and spicy). The statistical significance levels between groups are highlighted with ">" where the angle bracket's opening is in the greater value's direction. Also: “>>>”, “>>”, and “>” indicate respectively p<.001, p<.01, and p<.05. Statistical differences within groups are highlighted by letters/numbers; the same letter/number indicates statistically significant differences.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics.

| Demographics |

|---|

| |

all |

f |

m |

p-value |

Chi-square test (df) |

| Sex ratio |

233 |

117 |

116 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

| Age (mean years) |

27.4 (SD=10.5) |

26.5 (SD=10.7) |

28.3 (SD=10.3) |

0.203 |

-1.275 (231)$

|

| BMI |

n.a. |

23.4 (SD=4.4) |

23.0 (SD=3.2) |

n.a. |

n.a. |

| Smoking |

non-smoker: 186 (80%)

smoker: 47 (20%) |

100 (85%)

17 (15 %) |

86 (74%)

30 (26%) |

0.02 * |

7.561(2) |

| Education |

at least high-school diploma 145 (62%) |

71 (61%) |

74 (64%) |

0.88 |

1.222(4) |

| Residence |

in a big city (pop. > 100000):

160 (60%)

in a city (pop. = 5000 ÷100000):

44 (19%)

in a village/rural area (pop.< 5000)

29 (12.4%) |

72 (62%)

28 (24%)

17 (15%) |

88 (76%)

16 (14%)

12 (10%)

|

0.06 |

5.731(2) |

| Having lived abroad |

Experience of living in a foreign country

56 (24%)

never lived abroad

117 (76%) |

35 (30%)

82 (70%) |

21 (18%)

95 (82%) |

0.04 * |

4.451(1) |

| salt consumption |

never: 58 (25%)

sometime: 108 (46%)

most of the time: 56 (24%)

always: 11 (5%) |

29 (25%)

54 (46%)

28 (24%)

6 (5%) |

29 (25%)

54 (47%)

28 (24%)

5 (4%) |

0.993 |

0.087(3) |

| sweets consumption |

Never: 11 (4.7%)

once-at-month: 8 (3.4%)

once-a-week: 69 (30%)

more than once a week: 105 (45%)

every day: 40 (17%) |

3 (3%)

3 (3%)

35 (30 %),

54 (46%),

22 (19%) |

8 (7%)

5 (4%)

34 (29%)

51 (44%)

18 (16%) |

0.514 |

3.269(4) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).