1. Introduction

The introduction of non-native species has become so widespread that many systems have been invaded by multiple non-native species [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Once established, invasive species can facilitate the colonization of additional non-native species, an ecological process referred to invasional meltdown [

5,

6,

7]. Thus, work evaluating the combined effects of multiple species introductions on native species is an important topic of concern for conservation biologists [

8,

9].

Some studies have shown that multiple invasive species can have substantial impacts on endemic species. The potential for compounded impacts by multiple non-natives is important in many aquatic ecosystems [

10]. For example, ballast water exchange introduced Eurasian Zebra Mussel,

Dreissena polymorpha, and the Round Goby

Neogobius mela nostomus, resulting in both individual and synergistic impacts on aquatic communities [

11,

12]. Zebra Mussels altered the planktonic community structure that allowed the Round Goby to obtain competitive superiority over endemic species such as the Mottled Sculpin,

Cottus bairdii [

12].

Emergent effects of multiple predators can reduce risk due to interactions among predators or increase risk if prey responses to one predator increases risk to another predator [

1]. For example, Palacios et al. [

13] discussed the potential implications of introducing novel predators with a piscivorous prey species and found that predator identity determined if there were any positive or negative interactions on the multiple predator effect on prey species persistence. By contrast, Porter-Whitaker et al. [

3] reported that prey responses to multiple predators were intermediate to the sole effects of each predator.

A wide variety of invasive species have been directly associated with the decline and extirpation of numerous endemic aquatic species in the southwestern deserts of the United States [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. For example, both Western Mosquitofish,

Gambusia affinis, and Red Swamp Crayfish,

Procambarus clarkii, were introduced into the southwest early in the twentieth century [

19,

20]. The rapid spread of both species was likely facilitated by their rapid population growth rates and broad ecological tolerances [

21,

22,

23]. Crayfish prey on the adults and larvae of benthic fishes [

24,

25]., while mosquitofish are voracious predators of fish eggs and larvae [

23,

26].

The impacts of non-native species on desert aquatic ecosystems have been attributed to predator naiveté of endemic fishes, which evolved in depauperate communities. Specifically, endemic fishes are hypothesized to have lost anti-predator traits as they evolved in simple systems with limited predation and interspecific competition, thus making them vulnerable to invasive predators [

14,

15,

16,

27,

28].

The direct effects of both Red Swamp Crayfish and Western Mosquitofish have been independently evaluated amongst numerous experimental studies [

24,

25,

26,

29,

30,

31]. Rogowski and Stockwell [

30] showed that experimental populations of the White Sands Pupfish,

Cyprinodon tularosa, declined when sympatric with Virile Crayfish,

Orconectes virilis, at high densities or when sympatric with mosquitofish; however, the combined effects of crayfish and mosquitofish have not yet been studied empirically.

Understanding the possible interactions of both Western Mosquitofish and Red Swamp Crayfish is critical for resource management because both of these non-native species a are listed as the greatest threat to the various endemic fishes in the Southwestern US [

32]. The co-invasion of Red Swamp Crayfish and Western Mosquitofish have been associated with the decline of two refuge populations of the Endangered Pahrump Poolfish,

Empetrichthys Latos. The largest refuge population of Pahrump Poolfish, at Lake Harriet rapidly declined following the colonization of the lake by Red Swamp crayfish, in 2012, followed by the discovery of Western Mosquitofish in 2015 [

33,

34]. The poolfish population was estimated at 12,285 poolfish (10,791 – 13,988, 95% Confidence Interval) in 2015, but within one year declined to 362 poolfish (194-741, 9% Confidence Interval). Over the following year, 688 poolfish were captured and relocated to a fish hatchery (644 fish) and Corn Creek (44 fish)[

33,

34].

This decline of the poolfish population at Lake Harriet inspired us to take an experimental approach to evaluating the combined effects of crayfish and mosquitofish on experimental poolfish populations. Specifically, this paper focuses on ecological relationships among poolfish, crayfish and mosquitofish to replicate the co-invasion of Lake Harriet by these two species. This study tests the synergistic effects of dual species invasion on Pahrump Poolfish.

2. Materials and Methods

Western Mosquitofish were obtained from Sutter-Yuba Mosquito and Vector Control district in Yuba City, CA. Poolfish used in this experiment included a mixture of wild poolfish and lab-reared poolfish. The wild poolfish were collected from on 13 June 2017 from Shoshone Stock Pond (White Pine County, NV) while the lab-reared poolfish were descendants from poolfish originally collected in 2014 from Spring Mountain Ranch State Park, Clark County [

31]. Red Swamp Crayfish were sourced from Carolina Biological suppliers Burlington, NC.

Three fish communities were used in this experiment forming a single block within a randomized block design. Each of seven blocks contained a total of three mesocosms including the following treatments: I.) allopatric poolfish, II.) poolfish sympatric with crayfish, and III.) poolfish sympatric with both mosquitofish and crayfish. We did not include a poolfish + mosquitofish treatment because of the limited number of poolfish available for this experiment. Further, three previous experiments consistently showed that mosquitofish effectively eliminated the production of juvenile poolfish [

31,

35].

Each block of three tanks was replicated seven times for a total of 21 experimental tanks, arranged in a linear sequence. All 21 tanks received seven adult poolfish of indeterminate sex and of indeterminate population of origin (Shoshone Stock Pond 2017 or Spring Mountain Ranch 2014). Four individual crayfish were introduced into two randomly selected mesocosms per block. One of the two crayfish mesocosms within each block was randomly selected to receive mosquitofish, including five gravid females and two males. Crayfish density was maintained by replacing any crayfish that died.

All mesocosms were provided with reclaimed PVC vinyl Fishiding® structures to simulate aquatic plants and to provide spatial structure along with ~57 L of river rock. Supplemental food was provided every day to each tank at rates of ~2-3% of total fish biomass, while crayfish were fed twice weekly. Food consisted of Tetra tropical flake, and Aquatic Arts (Fish, Inverts, and Aquatic Plant) sinking pellets. Water quality was assessed weekly for ammonia and nitrates. All tanks were checked daily for mortalities, and to ensure air flow was constant from air stones. After ten-weeks, the tanks were drained, and juveniles and adults were counted.

Data were analyzed using JMP Pro 17® software. We tested for treatment effects on adult survival, juvenile production and the number of juveniles produced per surviving adult poolfish. We used ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD while maintaining experimental-wise alpha at 0.05. For each test, block was not significant and was eliminated from the final model. Non-parametric analyses produced the same significance levels among treatments for all tests, but here we report the parametric ANOVA results.

Data Availability: Data are available via Dryad. Paulson, Brandon; Stockwell, Craig (Forthcoming 2024). Crayfish & Mosquitofish impacts on Experimental Poolfish Populations [Dataset]. Dryad.

https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.gqnk98sz3

Ethics Approval: This work has been conducted under Fish and Wildlife Service permit TE126141-4, Nevada scientific collecting permit S-34628, and North Dakota State University (NDSU) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol #A18054.

3. Results

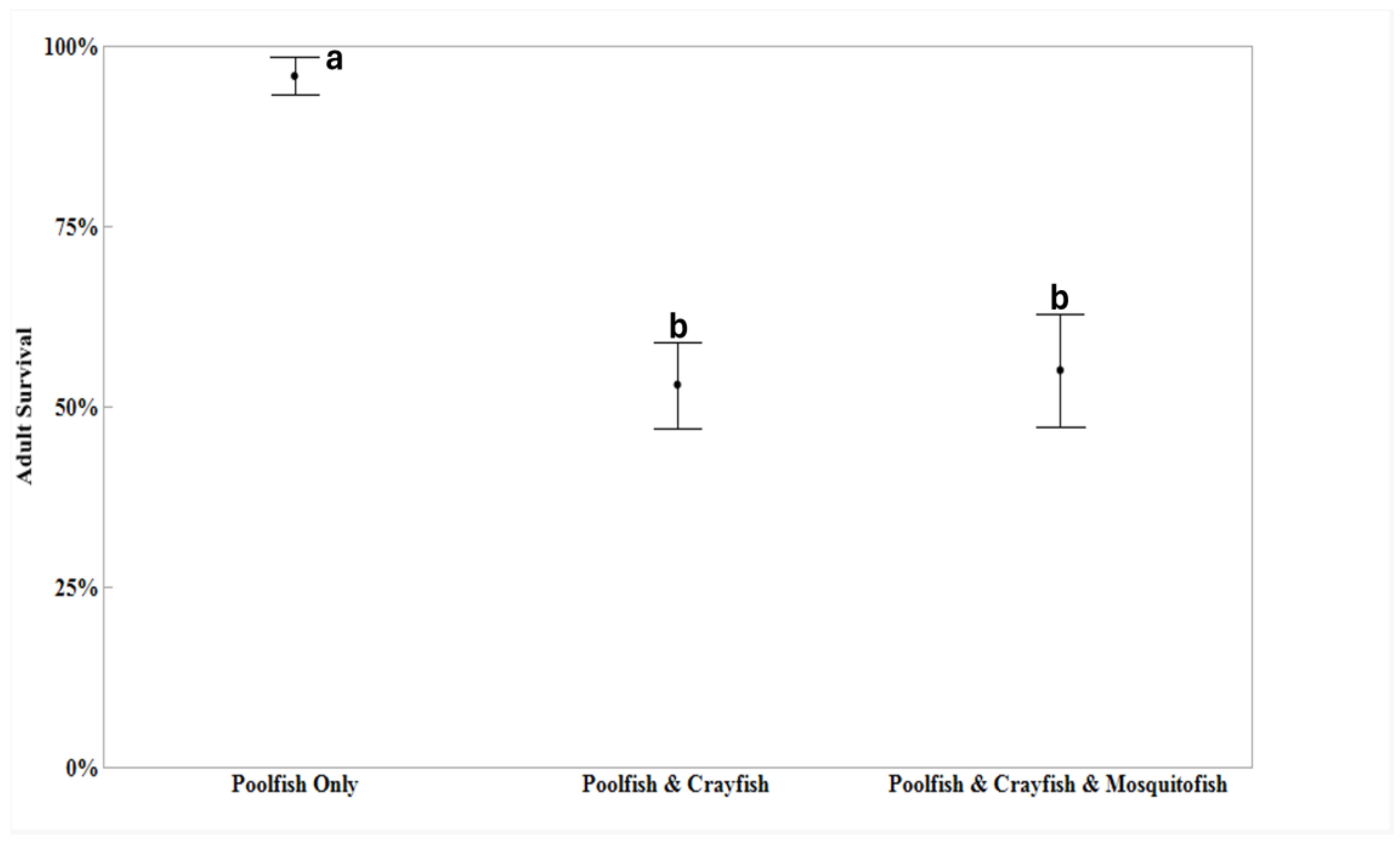

Adult survival (percentage) significantly differed among the three treatments (F = 16.65, P < 0.001;

Figure 1). In allopatry, adult poolfish survival rates were near 100% (95.9± 2.6%; mean ± one standard error of the mean) and significantly higher compared to adult poolfish survival when sympatric with crayfish (53.1 ± 6.0%; P < 0.001) and when poolfish were sympatric with both crayfish and mosquitofish (55.1± 7.9%; P < 0.001;

Figure 1). The latter two treatments did not significantly differ from each other (P = 0.969).

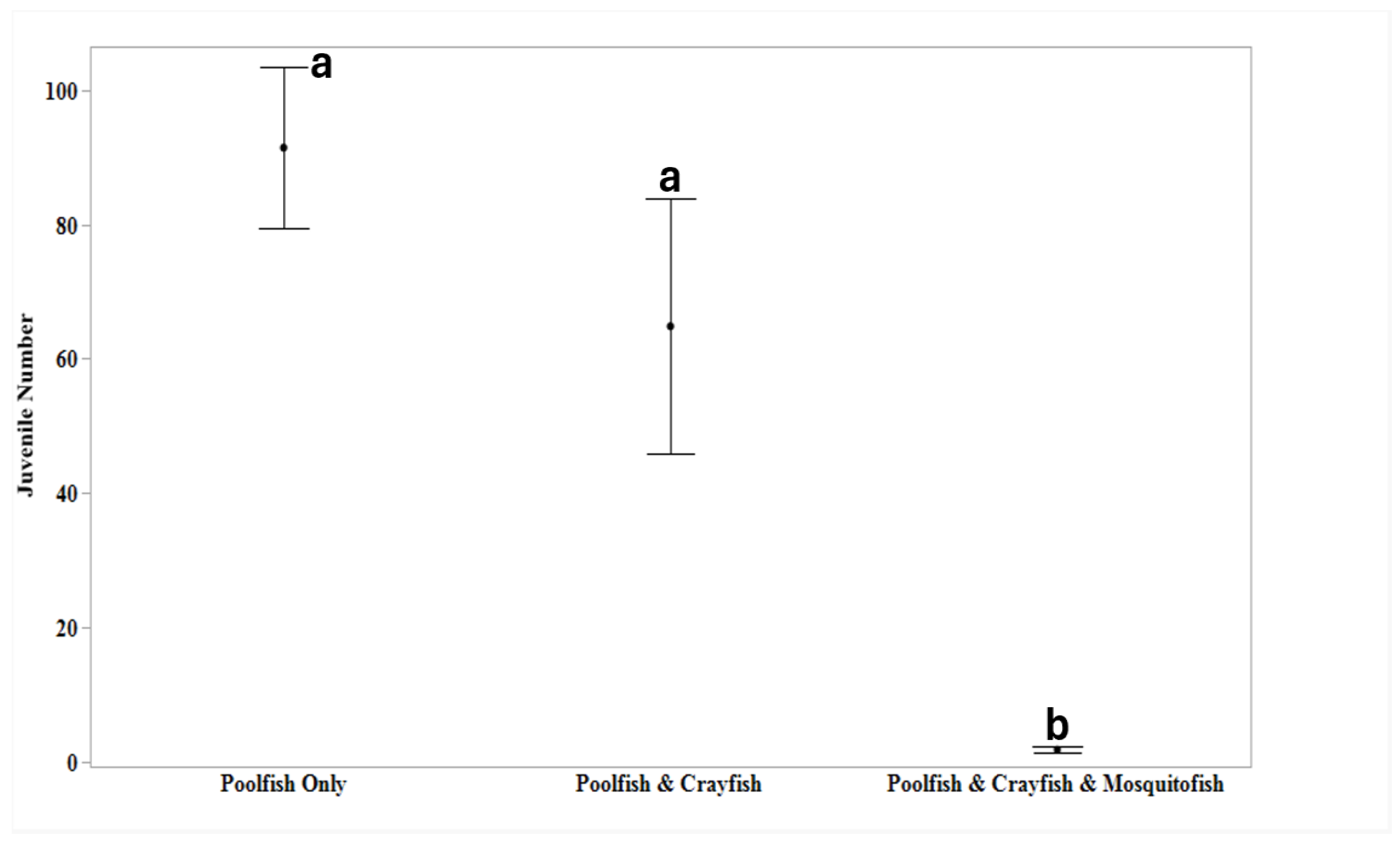

Juvenile production differed significantly among the three treatments (F = 12.56, P < 0.001;

Figure 2). Juvenile productivity in mesocosms with allopatric poolfish (91.4 ± 12.0; juveniles per tank), was 41% higher than juvenile production for mesocosms hosting poolfish and crayfish (64.9 ± 19.0), but this difference was not significant (P = 0.339). However, juvenile production, which plummeted to near zero (1.9 ± 0.5) when poolfish were sympatric with both crayfish and mosquitofish, was significantly different from both allopatric poolfish (P < 0.001) and when compared to the poolfish sympatric with only crayfish (P = 0.008;

Figure 2).

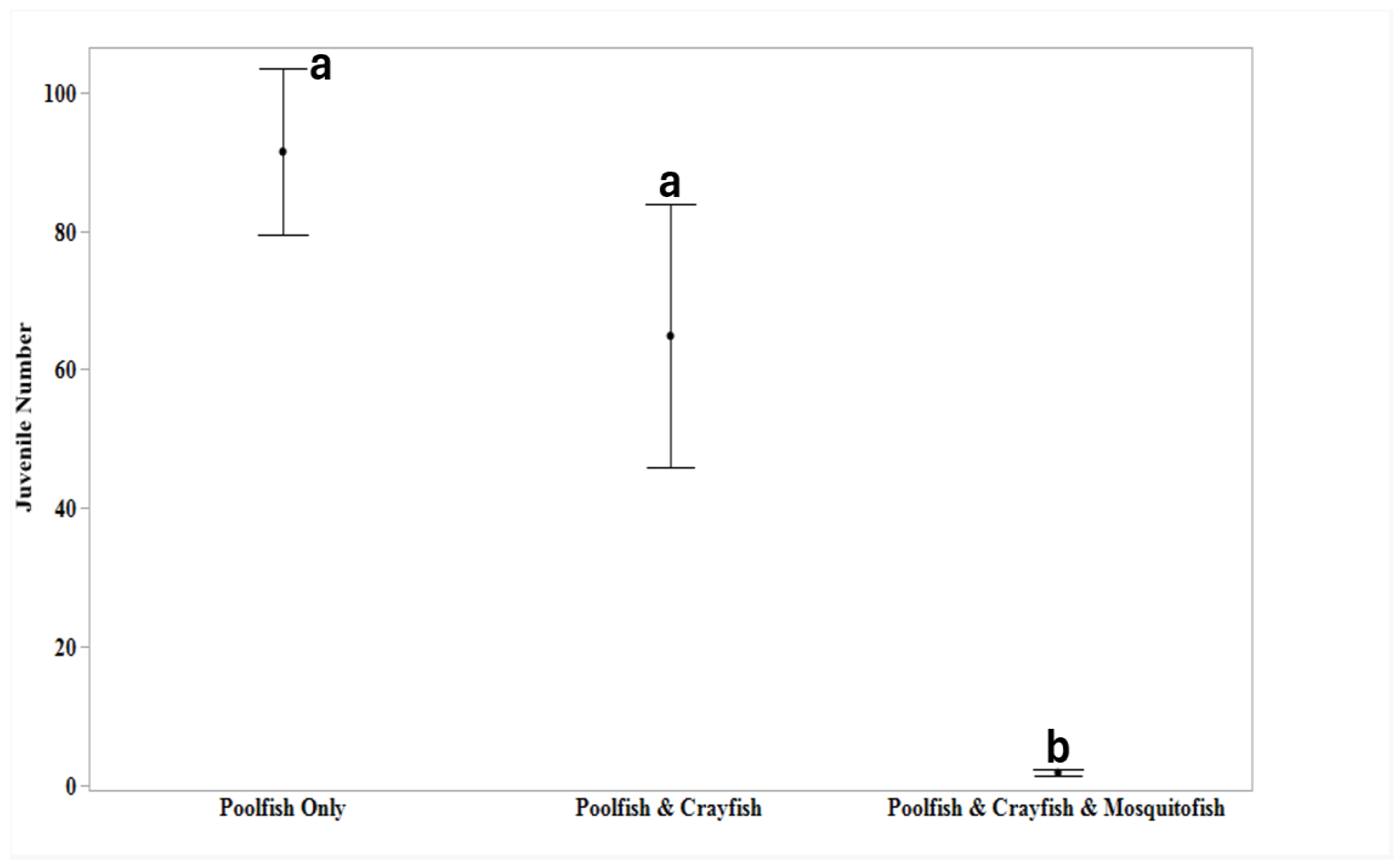

Due to the high variation in adult survival among treatments, we also examined the number of juveniles per surviving adult. After adjusting for the number of surviving adults, relative juvenile production was significantly different among the three treatments (F = 11.94 ; P < 0.001;

Figure 3). Relative juvenile production for mesocosms with allopatric poolfish (13.6 ± 1.7 juveniles/surviving adult) did not differ from mesocosms with poolfish sympatric with crayfish (17.5 ± 4.1 juveniles/surviving adult; P = 0.545). However, relative juvenile production was significantly higher for both of these treatments compared to Poolfish sympatric with both crayfish and mosquitofish (0.5 ± 0.1 juvenile/surviving adult; P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively).

4. Discussion

In our study, crayfish caused an approximately 40% increase in adult poolfish mortality, but the addition of mosquitofish did not have any additional effects on poolfish adult mortality. Such impacts on adult survival would be expected to decrease juvenile productivity. In fact, there was a notable, but non-significant, reduction in poolfish juvenile production for the poolfish & crayfish mesocosms. It is notable, however, that relative juvenile production (juveniles / surviving adult poolfish) was not significantly impacted by the sole presence of crayfish.

The combined effects of both crayfish and mosquitofish effectively eliminated the production of poolfish juveniles. It is noteworthy, that similar work has shown mosquitofish to virtually eliminate poolfish juvenile production [

25,

35]. Our findings suggest a lack of emergent effects of multiple predators [sensu 1] on poolfish.

Our findings suggest that the sole introduction of crayfish may have notable impacts on the survival of poolfish adults, and these in turn reduce the number of juveniles produced. However, poolfish populations grew by nearly 10-fold when in the presence of crayfish. Thus, crayfish are unlikely to have immediate acute impacts. Indeed, the Corn Creek refuge population of poolfish co-persisted with Red Swamp Crayfish for 5 years. However, this population collapsed shortly after non-native fish were detected (Kevin Guadalupe Nevada Department of Wildlife, personal communication). Furthermore, following the discovery of Red Swamp Crayfish, the Lake Harriet Poolfish population displayed an initial decline in abundance, but fluctuated around 10,000 individuals for the next three years [

33,

34]. Nevertheless, this poolfish population declined to less than 1,000 poolfish one year after the detection of Western Mosquitofish [

34]. These findings are consistent with earlier work showing severe impacts of mosquitofish on recruitment of poolfish juveniles [

31,

36].

Numerous mesocosm and observational studies have focused on the effects of individual non-native species. For instance, many studies have shown that mosquitofish have significant impacts on production of juveniles of native fishes [

25,

26,

29,

30,

31,

35,

36]. However, there have been limited efforts to evaluate the combined effects of multiple invasive species such as the combination of Western Mosquitofish and Red Swamp Crayfish. Other studies have considered the synergistic interactions among invasive species on facilitating the invasion of additional invasive species, referred to as invasional meltdown [

5,

6,

7]. However, the impacts of multiple invasive species have not received as much attention.

Our work has relevance for understanding historic impacts of non-native species on several endemic species within Ash Meadows. For example, Miller et al. [

17] attributed extinction of the Ash Meadows Killifish to crayfish, while Minckley and Deacon [

16] inferred that the extinction of the Ash Meadows Killifish occurred following the

co-invasion of both crayfish and mosquitofish. However, it is notable that the Ash Meadows Amargosa Pupfish,

C. nevadensis mionectes, persisted with both non-natives at various springs in Ash Meadows. Scoppettone et al. [

37] hypothesized that spatial variability in temperature may have facilitated co-persistence as native pupfish utilized warmer waters limiting interspecific interactions of pupfish with crayfish and mosquitofish [

37]. Collectively, these observations combined with our experimental data suggest that the extinction of

E. merriami within Ash Meadows may have been due to more than the solitary impacts of Red Swamp Crayfish.

Overall, this study, combined with previous mesocosm experiments [

25,

35], demonstrates that Pahrump Poolfish are severely impacted by the presence of non-native species. The vulnerability of Pahrump Poolfish to non-native predators is consistent with the predator naiveté hypothesis [

28]. In contrast to other desert fishes, poolfish do not respond to conspecific alarm cues, suggesting limited anti-predator competence [

28,

38,

39]. Thus, the current approach of managing Pahrump Poolfish in single species refugia is clearly warranted. Poolfish may be able to co-persist with invasive crayfish, but immediate intervention should be taken if Western Mosquitofish invade any of the poolfish refuge habitats. Our study shows the value of evaluating the effects of multiple invasive species on native species, but additional work should be undertaken to evaluate other combinations of invasive species.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, B.P and C.S.; methodology, B.P. and C.S.; formal analysis, B.P. and C.S.; investigation, B.P.; resources, C.S.; data curation, C.S.; writing—B.P.; writing—review and editing, B.P. and C.S.; supervision, C.S.; project administration, C.S.; funding acquisition, B.P. and C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding” or “This research was funded by Desert Fishes Council Conservation Grant to B.P. and by the Environmental & Conservation Sciences Graduate Program at North Dakota State University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the North Dakota State University’s Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee, protocol #A18054.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available via Dryad. Paulson, Brandon; Stockwell, Craig (Forthcoming 2024). Crayfish & Mosquitofish impacts on Experimental Poolfish Populations [Dataset]. Dryad.

https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.gqnk98sz3

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank M. Snider, B. Gillis and S. Kettelhut and K. Guadalupe for assistance with field work. Darrell Jew with Yuba-Sutter Mosquito Control District graciously collected and sent us Western Mosquitofish for this work. We also thank L. Simons and J. Harter (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) and the Poolfish Recovery Implementation Team for providing logistical support. We thank C. Anderson, K. Guadalupe and B. Wisenden for reviewing an earlier version of this manuscript. This work has been conducted under Fish and Wildlife Service permit TE126141-4, Nevada scientific collecting permit S-34628, and North Dakota State University (NDSU) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol #A18054. This work was supported by a Desert Fishes Council Conservation Grant and stipend support for BLP from the NDSU Environmental and Conservation Sciences Graduate Program. There is no conflict of interest declared in this article. This paper is dedicated to the memories of Lee Simons and Phil Pister for their commitment to the conservation of desert fishes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Sih, A.; Englund, G.; Wooster, D. Emergent impacts of multiple predators on prey. Trends Ecol & Evol 1998, 13, 350–355. [Google Scholar]

- García-Berthou, E.; Alcaraz, C.; Pou-Rovira, Q.; Zamora, L.; Coenders, G.; Feo, C. Introduction pathways and establishment rates of invasive aquatic species in Europe. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 2005, 62, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter-Whitaker, A.E.; Rehage, J.S.; Liston, S.E.; Loftus, W.F. Multiple predator effects and native prey responses to two non-native Everglades cichlids. Ecol Freshwater Fish 2012, 21, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, B.; Clavero, M.; Sánchez, M.I.; Vilà, M. Global ecological impacts of invasive species in aquatic ecosystems. Glob Chang Biol 2016, 22, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simberloff, D.; Von Holle, B. Positive interactions of nonindigenous species: invasional meltdown? Biol Invasions 1999, 1, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simberloff, D. Invasional meltdown 6 years later: important phenomenon, unfortunate metaphor, or both? Ecol Lett 2006, 9, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, R.R.; Gómez-Aparicio, L.; Heger, T.; Vitule, J.R.; Jeschke, J.M. Structuring evidence for invasional meltdown: broad support but with biases and gaps. Biol Invasions 2018, 20, 923–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyšek, P.; Richardson, D.M. Invasive species, environmental change and management, and health. Ann Rev of Environ and Res 2010, 35, 25–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, A.; Hoopes, M.F.; Marchetti, M.P.; Lockwood, J.L. Progress toward understanding the ecological impacts of nonnative species. Ecol Monographs 2013, 83, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariton, J.T.; Geller, J.B. Ecological roulette: The global transport of nonindigenous marine organisms. Science 1993, 261, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jude, D.J.; Reider, H.; Smith, G.R. Establishment of Gobiidae in the Great Lakes basin. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 1992, 49, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.; Jude, D.J. Recruitment failure of mottled sculpin Cottus bairdi in Calumet Harbor, Southern Lake Michigan induced by the newly introduced round goby Neogobius melanostomus. J Great Lakes Res 2001, 27, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, M.M.; Malerba, M.E.; McCormick, M.I. Multiple predator effects on juvenile prey survival. Oecologia 2018, 188, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.R. Man, and the changing fish fauna of the American southwest. Mich Acad Sci Arts Letters 1961, 46, 365–404. [Google Scholar]

- Deacon, J.E.; Hubbs, C.; Zahuranec, B.J. Some effects of introduced fishes on the native fish fauna of southern Nevada. Copeia 1964, 1964, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minckley, W.L.; Deacon, J.E. Southwestern fishes and the enigma of "endangered species". Science 1968, 159, 1424–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.R.; Williams, J.D.; Williams, J.E. Extinctions of North American fishes during the past century. Fisheries 1989, 14, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucherousset, J.; Olden, J.D. Ecological impacts of nonnative freshwater fishes. Fisheries 2011, 36, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, H.H.; Zinn, D.J. Crayfish in southern Nevada. Science 1948, 107, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockwell, C.A.; Mulvey, M.; Vinyard, G.L. Translocations and the preservation of allelic diversity. Conserv Biol 1996, 10, 1133–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumholz, L.A. Reproduction in the western mosquitofish, Gambusia affinis affinis (Baird & Girard), and its use in mosquito control. Ecol Mono 1948, 18, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Huner, J.V.; Lindqvist, O.V. Physiological adaptations of freshwater crayfishes that permit successful aquacultural enterprises. Amer Zool 1995, 35, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyke, G.H. Plague minnow or mosquito fish? A review of the biology and impacts of introduced gambusia species. Ann Rev Ecol Evol Syst 2008, 39, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.L.; Taylor, C.A. Scavenger or predator? examining a potential predator–prey relationship between crayfish and benthic fish in stream food webs. Freshwater Sci 2013, 32, 1309–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulson, B.L.; Stockwell, C.A. Density-dependent effects of invasive Red Swamp Crayfish Procambarus clarkii on experimental populations of the Amargosa Pupfish. Trans Am Fish Soc 2020, 149, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkanaththegedara, S.M.; Stockwell, C.A. Intraguild predation may facilitate coexistence of native and non-native fish. J Appl Ecol 2014, 51, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.G.; Lima, S.L. Naiveté and an aquatic–terrestrial dichotomy in the effects of introduced predators. Trends Ecol Evol 2006, 21, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockwell, C.A.; Schmelzer, M.R.; Gillis, B.E.; Anderson, C.M.; Wisenden, B.D. Ignorance is not bliss: evolutionary naiveté in an endangered desert fish and implications for conservation. Proc Roy Soc B. 2022, 289, 20220752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, M.D.; Rader, R.B.; Belk, M.C. Complex interactions between native and invasive fish: The simultaneous effects of multiple negative interactions. Oecologia 2004, 141, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowski, D.L.; Stockwell, C.A. Assessment of potential impacts of exotic species on populations of a threatened species, White Sands pupfish, Cyprinodon tularosa. Biol Invasions 2006, 8, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, S.C.; Stockwell, C.A. An experimental test of novel ecological communities of imperiled and invasive species. Trans Am Fish Soc 2016, 145, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sada DW (1990) Recovery plan for the endangered and threatened species of Ash Meadows, NV USFWS.

- Burg C, Guadalupe K, NDOW Report (2015) Field Trip Report: Lake Harriet, Spring Mountain Ranch State Park, Clark County, NV, to assess the population of Pahrump Poolfish, Nevada Department of Wildlife, Las Vegas.

- Guadalupe K, NDOW Report (2016) Nevada Department of Wildlife Pahrump Poolfish Recovery Implementation Team update report.

- Paulson, B.L. Ex situ analyses of non-native species impacts on imperiled desert fishes. Thesis, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND, U.S.A., 2019.

- Goodchild, S.C. Life history and interspecific co-persistence of native imperiled fishes in single species and multi-species ex situ refuges. Dissertation, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND, U.S.A., 2015.

- Scoppettone, G.G.; Rissler, P.H.; Gourley, C.; Martinez, C. Habitat restoration as a means of controlling non-native fish in a Mojave Desert oasis. Restoration Ecol 2005, 13, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.M.; Wisenden, B.D.; Craig, C.A.; Stockwell, C.A. Consistent antipredator behavioral responses among populations of Red River pupfish with disparate predator communities. Fishes. 2023, 8, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisenden, B.D.; Anderson, C.M. : Hanson, K.A.; Johnson, M.I.; Stockwell, C.A. Acquired predator recognition via epidermal alarm cues but not dietary alarm cues by isolated pupfish. Royal Society Open Science. 2023, 10, 230444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulson, B.; Stockwell, C. Crayfish & Mosquitofish impacts on Experimental Poolfish Populations [Dataset]. Dryad. https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.gqnk98sz3 , Forthcoming 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).