Submitted:

03 November 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

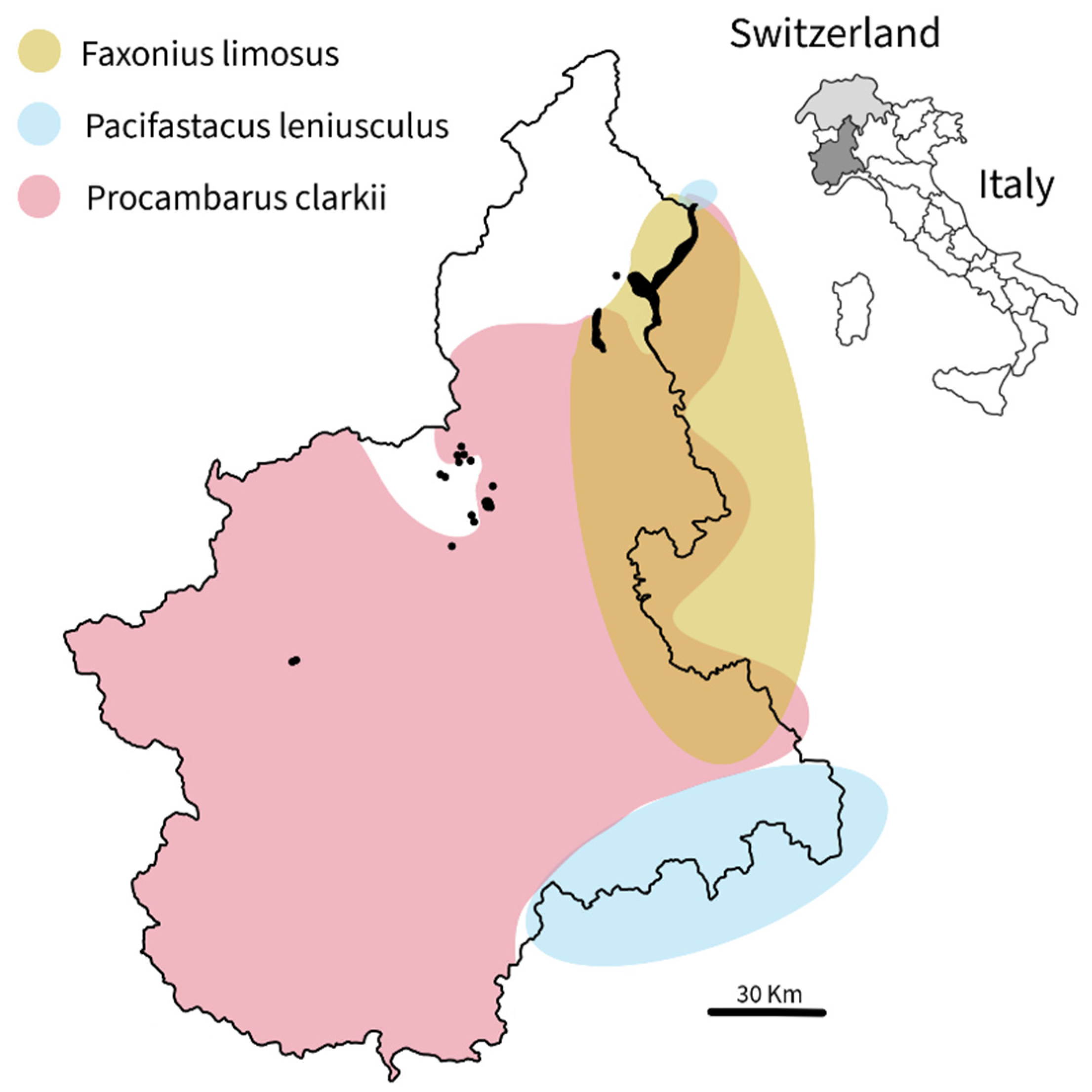

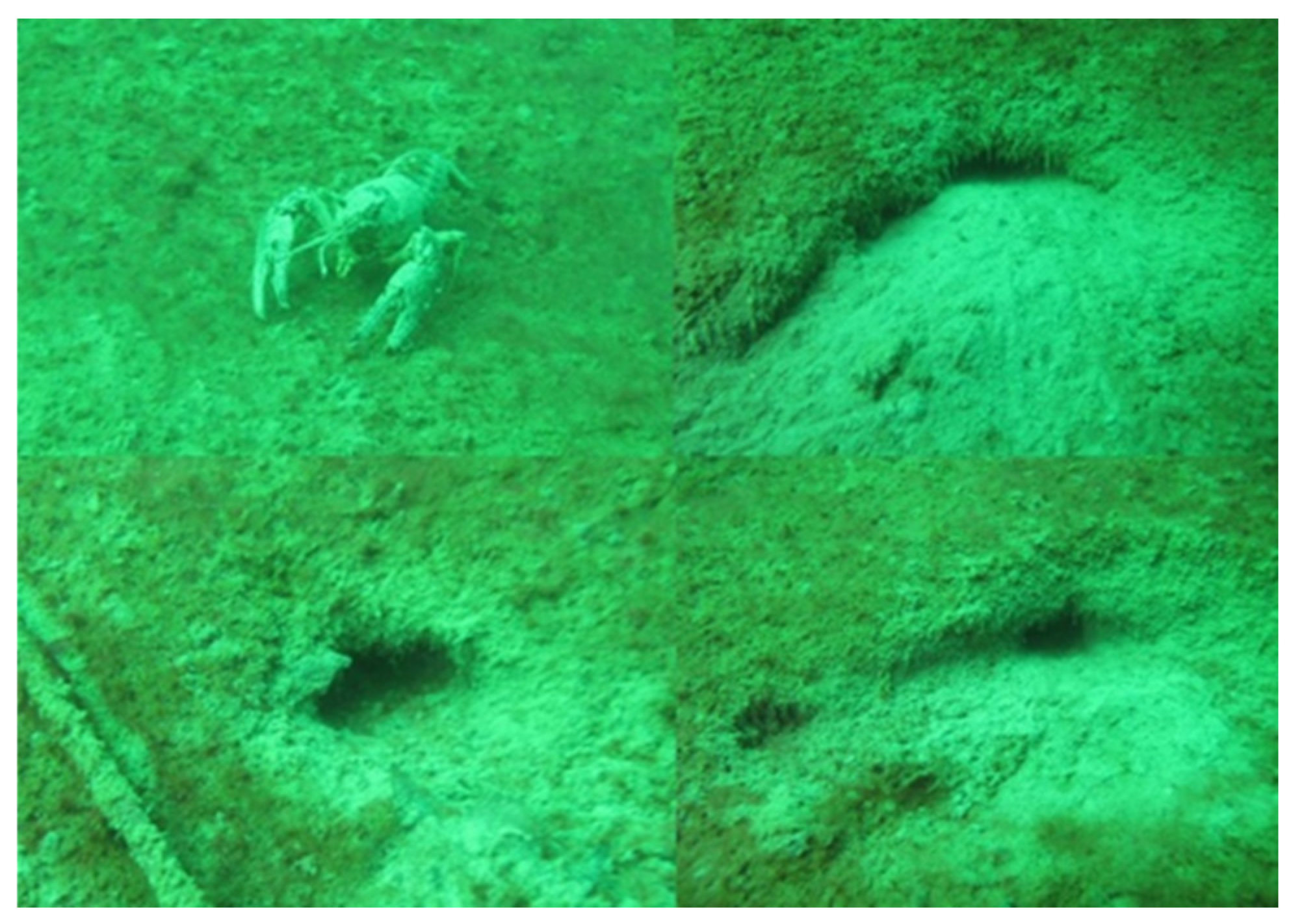

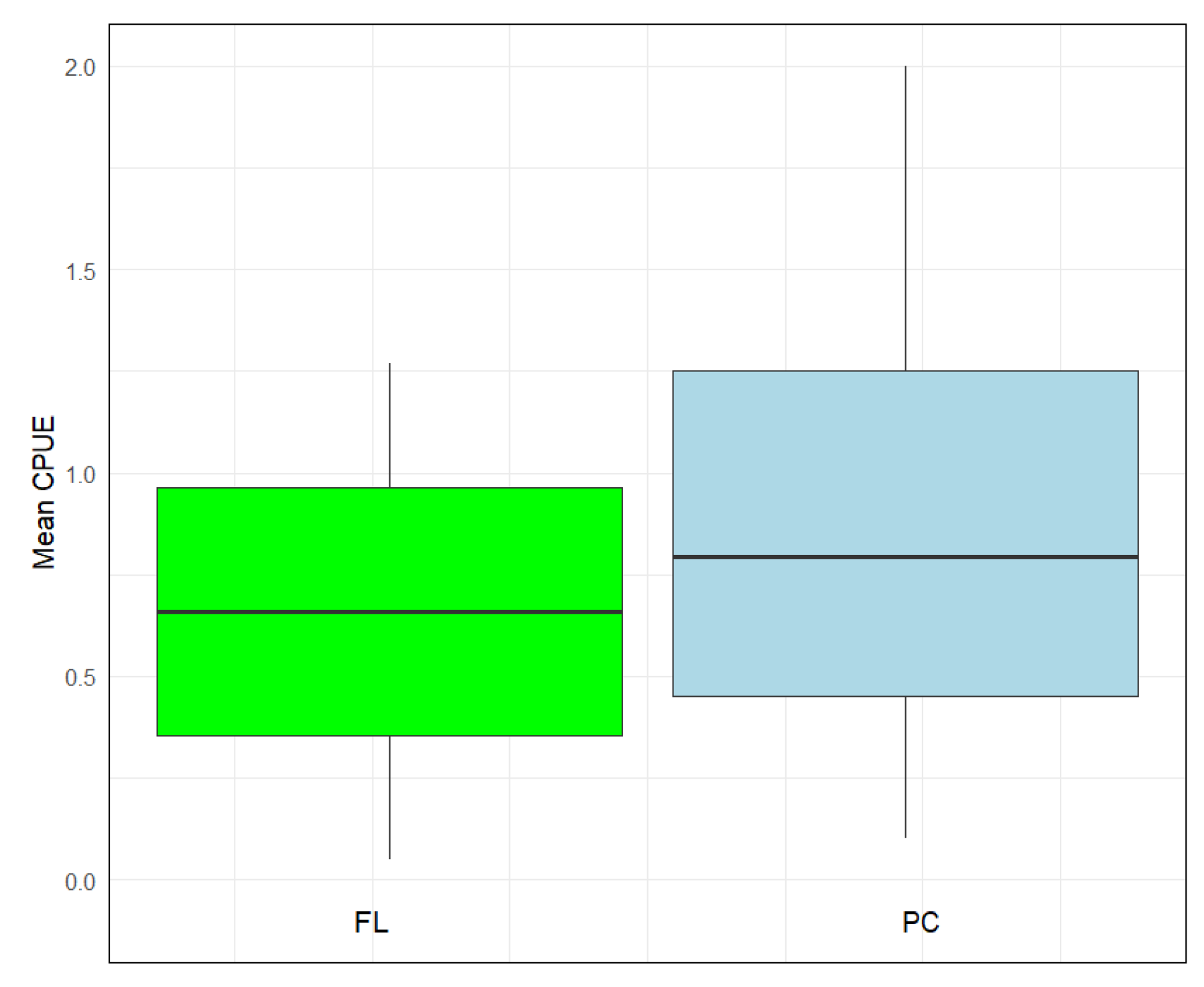

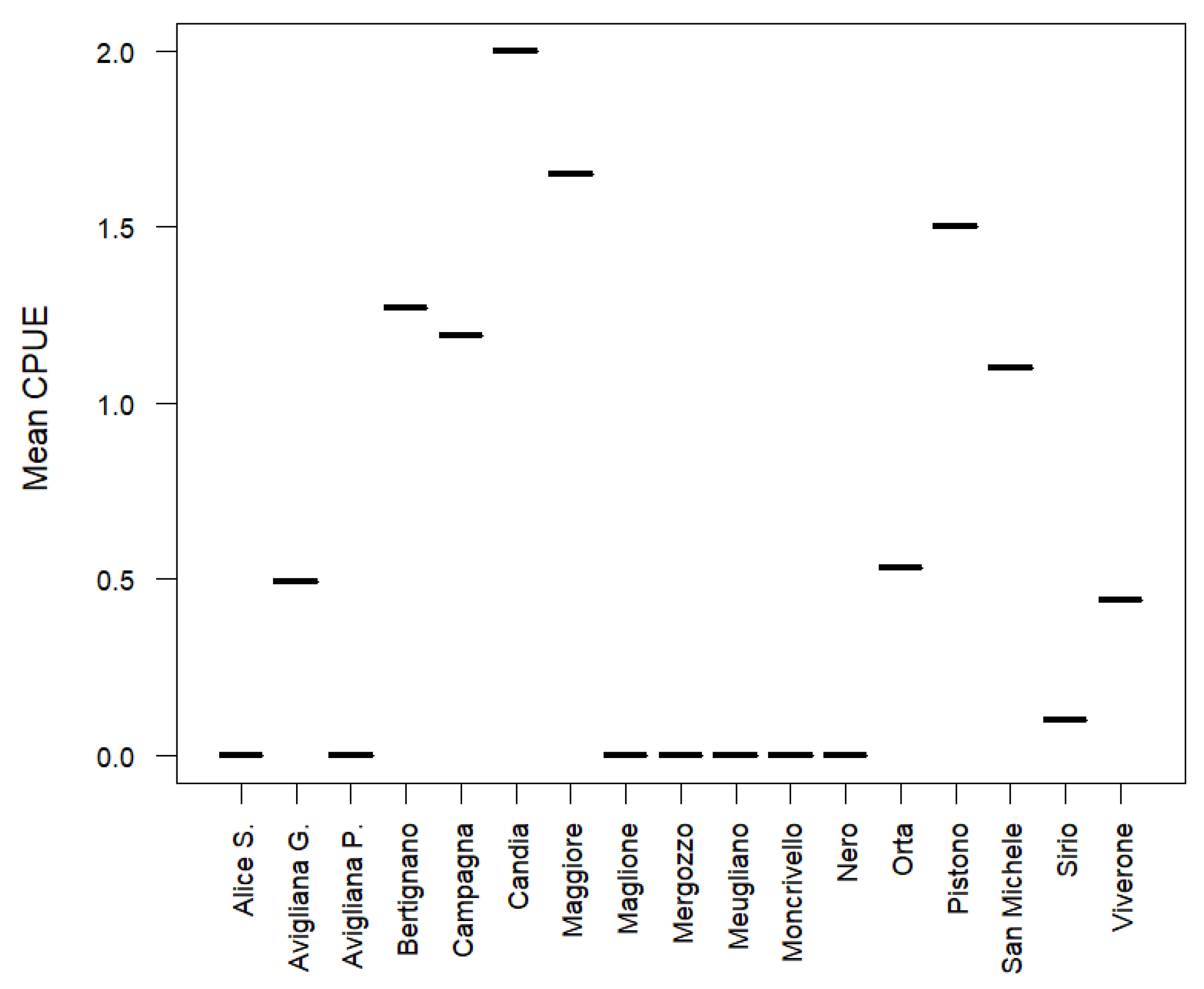

Crayfish often become invasive when introduced to new waters. The mid-20th-century commercial import of North American species (e.g., Faxonius limosus, Pacifastacus leniusculus, Procambarus clarkii) into Europe for food, pets, and restocking after crayfish plague, succeeded due to their adaptability, high reproductive rates, and resilience. Extensive baited-trap monitoring of Piedmont lakes allowed us to confirm the occurrence of the Old Non-Indigenous Crayfish Species (F. limosus, P. leniusculus, and P. clarkii), and to record P. clarkii first-ever in three additional lakes (Pistono, San Michele, and Sirio), thereby expanding our knowledge of their distribution in Piedmont freshwaters. Since all detected species are listed as Invasive Alien Species of Union Concern, protecting the ecological integrity of Piedmont’s freshwaters requires coordinated action by member states, regional authorities, policymakers, and water managers to prevent and control their spread, and to improve information sharing. Non-native crayfish occurrence is influenced not only by hydrological and habitat connectivity, and predator–prey interactions, but also by illegal activities that supply the food market.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field and Laboratory Procedures

3. Results

4. Discussion

Historical Context

5. Conclusions

- An inventory of non-native crayfish for Piedmont lakes had never been conducted prior to 2025, making this the first comprehensive effort to document the occurrence and to assess the distribution of non-native crayfish species within the region. Extensive baited-trap monitoring allowed us to confirm the occurrence of the Old Non-Indigenous Crayfish Species (F. limosus, P. leniusculus, and P. clarkii), and to record P. clarkii first-ever in three never monitored lakes (Pistono, San Michele, and Sirio).

- Isolated lakes or those with complex predator–prey networks host few or lack non-native crayfish because limited connectivity restricts dispersal while high predator pressure and biotic interactions hinder establishment and recruitment.

- Presence of non-native crayfish alters community structure and stability by reducing prey availability and modifying predator dynamics; understanding these interactions is essential for invasive-species management and freshwater biodiversity conservation.

- Standardized monitoring of crayfish populations is not only crucial for assessing the ecological health of freshwater ecosystems, but also to enable comparison of data and trend analyses.

- This baseline is crucial for informing managers to develop effective strategies to prevent further spread, and to protect Piedmont’s freshwaters. Therefore, coordinated measures are required to prevent and control the ecological threats posed by invasive species.

- Moreover, improving information exchange across stakeholders and water managers, to halt illegal harvesting for food and pet trade since all these activities highly contribute to crayfish spread.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mathers, K.L.; White, J.C.; Fornaroli, R.; Chadd, R. Flow regimes control the establishment of invasive crayfish and alter their effects on lotic macroinvertebrate communities. J. Appl. Ecol., 2020, 57, 886–902, . [CrossRef]

- Soto, I.; Ahmed, D.A.; Beidas, A.; Oficialdegui, F.J.; Tricarico, E.; Angeler, D.G.; Haubrock, P.J. Long-term trends in crayfish invasions across European rivers. Sci. Total Environ., 2023, 867: 161537, . [CrossRef]

- Giordano, J.; Battisti, C. The non native red swamp crayfish Procambarus clarkii as prey for waterbirds: a note from Torre Flavia wetland (Central Italy). Alula, 2023, 30(1–2),194–199, . [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.; Miranda, N.A.F.; and Cumming, G.S. The role of waterbirds in the dispersal of aquatic alien and invasive species. Diversity Distrib, 2015 21, 744-754. [CrossRef]

- Lodge, D.M.; Taylor, C.M.; Holdich, D.M.; Skurdal, J. Non-indigenous crayfishes threaten North American freshwater biodiversity: lessons from Europe. Fisheries, 2000, 25, 7–20, . [CrossRef]

- Emery-Butcher, H.E.; Beatty, S.J.; Robson, B.J. The impacts of invasive ecosystem engineers in freshwaters: A review. Freshwater Biol., 2020, 65: 999–1015, . [CrossRef]

- Crandall, K.A.; de Grave, S. An updated classification of the freshwater crayfishes (Decapoda: Astacidea) of the world, with a complete species list. J. Crust. Biol. 2017, 37, 615–653, . [CrossRef]

- Faulkes, Z. Prohibiting pet crayfish does not consistently reduce their availability online. Nauplius, 2018, 26: 1-11, . [CrossRef]

- Patoka, J.; Kalous, L.; Kopecký, O. Risk assessment of the crayfish pet trade based on data from the Czech Republic. Biol. Invasions, 2014, 16, 2489-2494, . [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, O.V.; Huner, J.V. Life history characteristics of crayfish: what makes some of them good colonizers? In Crayfish in Europe as alien species. How to make the best of a bad situation? Gherardi, F.; Holdich, D.M. Eds; Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherland, 1999: pp 23–30, . [CrossRef]

- Moorhouse, T.P.; Macdonald, D.W. Are invasives worse in freshwater than terrestrial ecosystems? WIREs Water, 2015, 2, 1–8, . [CrossRef]

- Simberloff, D. Maintenance management and eradication of established aquatic invaders. Hydrobiologia, 2021, 848: 2399–2420, . [CrossRef]

- Lodge, D.M.; Deines, A.; Gherardi, F.; Yeo, D.C.J.; Arcella, T.; Baldridge, A.K.; Barnes, M.A.; Chadderton, W.L.; Feder, J.L.; Gantz, C.A.; et al. Global Introductions of Crayfishes: Evaluating the Impact of Species Invasions on Ecosystem Services. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst., 2012, 43, 449–472, . [CrossRef]

- O’Hea-Miller, S.B.; Davis, A.R.; Wong, M.Y.L. The Impacts of Invasive Crayfish and Other Non-Native Species on Native Freshwater Crayfish: A Review. Biology, 2024, 13, 610, . [CrossRef]

- Olden, J.D.; Whattam, E.; Wood, S.A. Online auction marketplaces as a global pathway for aquatic invasive species. Hydrobiologia, 2021, 848, 1967–1979. [CrossRef]

- Haubrock, P.J.; Cuthbert, R.N.; Haase, P. Long-term trends and drivers of biological invasion in Central European streams. Sci. Total Environ., 2023, 876, 162817, . [CrossRef]

- Garzoli, L.; Mammola, S.; Ciampittiello, M.; Boggero, A. Alien Crayfish Species in the Deep Subalpine Lake Maggiore (NW-Italy), with a Focus on the Biometry and Habitat Preferences of the Spiny-Cheek Crayfish. Water, 2020,12(5): 1391, . [CrossRef]

- Demers, A.; Reynolds, J.D. Water quality requirements of the white-clawed crayfish, Austropotamobius pallipes, a field study. Freshw. Crayfish, 2006, 15, 283–291, . [CrossRef]

- Gray, A.; Mayer, K.; Gore, B.; Gaesser, M.; Ferguson, N. Microplastic burden in native (Cambarus appalachiensis) and non-native (Faxonius cristavarius) crayfish along semi-rural and urban streams in southwest Virginia, USA. Environ. Res., 2024, 258, 119494, . [CrossRef]

- Souty-Grosset, C., Holdich, D.M.; Noël, P.Y.; Reynolds, J.D.; Haffner, P. Atlas of Crayfish in Europe. Publications Scientifiques MNHN, Paris, France. Patrimoines naturels, 2006, 64, 187 pp.

- Welch, B.L. The significance of the difference between two means when the population variances are unequal. Biometrika, 1938, 29(3/4), 350-362.

- Regulation (EU) No. 1143/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the prevention and management of the introduction and spread of invasive alien species, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2014/1143/2019-12-14.

- Caffrey, J.M.; Baars, J.-R.; Barbour, J.H.; Boets, P.; Boon, P.; Davenport, K.; Dick, J.T.A.; Early, J.; Edsman, L.; Gallagher, C.; Gross, J.; Heinimaa, P.; Horrill, C.; Hudin, S.; Hulme, P.E.; Hynes, S.; MacIsaac, H.J.; McLoone, P.; Millane, M.; Moen, T.L.; Moore, N.; Newman, J.; O’Conchuir, R.; O’Farrell, M.; O’Flynn, C.; Oidtmann, B.; Renals, T.; Ricciardi, A.; Roy, H.; Shaw, R.; van Valkenburg, J.L.C.H.; Weyl, O.; Williams, F.; Lucy, F.E. Tackling Invasive Alien Species in Europe: The Top 20 Issues. Manag. Biol. Invasion, 2014, 5(1): 1–20, . [CrossRef]

- Holdich, D.M.; Reynolds, J.D.; Souty-Grosset, C.; Sibley, P.J. A review of the ever increasing threat to European crayfish from non-indigenous crayfish species. Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst., 2009, 394–395, 11, . [CrossRef]

- Aquiloni, L.; Tricarico, E.; Gherardi, F. Crayfish in Italy: Distribution, threats and management. Int. Aquat. Res. 2010, 2, 1–14.

- Manenti, R.; Ghia, D.; Fea, G.; Ficetola, G.F.; Padoa-Schioppa, E.; Canedoli, C. Causes and consequences of crayfish extinction: Stream connectivity, habitat changes, alien species and ecosystem services. Freshwater Biol., 2019, 64, 284–293, . [CrossRef]

- Siesa, M.E.; Manenti, R.; Padoa-Schioppa, E.; De Bernardi, F.; Ficetola, G.F. Spatial autocorrelation and the analysis of invasion processes from distribution data: A study with the crayfish Procambarus clarkii. Biol. Invasions, 2011, 13, 2147–2160. [CrossRef]

- Correia, C.; Borges, L. Spanish crayfish, Procambarus clarkii, with fyke nets & traps in Andalusia and Extremadura. Fith Report of the implementation of the FIP, 2024: 19 pp.

- Holdich, D.M. Biology of freshwater crayfish. Blackwell Science Ltd, Oxford, 2002.

- Englund, G.; Krupa, J.J. Habitat use by crayfish in stream pools: Influence of predators, depth and body size. Freshw. Biol., 2000, 43: 75–83, . [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Santigosa, N.; Hidalgo-Vila, J.; Florencio, M.; Díaz-Paniagua, C. Does the exotic invader turtle, Trachemys scripta elegans, compete for food with coexisting native turtles? Amphibia-Reptilia, 2011, 32(2), 167–75, . [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.; Gago, J.; Ribeiro, F.. Diet of European Catfish in a Newly Invaded Region. Fishes, 2019, 4(4), 58, . [CrossRef]

- David, P.; Thebault, E.; Anneville, O.; Duyck, P.F.; Chapuis, E.; Loeuille, N. Impacts of invasive species on food webs: a review of empirical data. Adv. Ecol. Res., 2017, 56, 1-60, . [CrossRef]

- Móréh, Á.; Scheuring, I. Invaders’ trophic position and their direct and indirect relationship influence on resident food webs. Ecol. Modell., 2025, 508, 111238, . [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, F. Aquiloni L.; Diéguez-Uribeondo, J.; Tricarico, E. Managing invasive crayfish: is there a hope? Aquat. Sci., 2011, 73: 185–200, . [CrossRef]

- Donato, R.; Rollandin, M.; Favaro, L.; Ferrarese, A.; Pessani, D.; Ghia, D. Habitat use and population structure of the invasive red swamp crayfish Procambarus clarkii (Girard, 1852) in a protected area in northern Italy. Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst., 2018, 419: 12, . [CrossRef]

- Larson, C.E.; Bo, T.; Candiotto, A.; Fenoglio, S.; Doretto, A. Predicting invasive signal crayfish (Pacifastacus leniusculus) spread using a traditional survey and river network simulation. River Res. Appl., 2022, 38, 1424–1435, . [CrossRef]

- Boggero, A.; Croci, C.; Zanaboni, A.; Zaupa, S., Paganelli, D.; Garzoli, L.; Bras, T.; Busiello, A.; Orrù, A.; Beatrizzutti, S.; Kamburska, L. New records of the spinycheek crayfish Faxonius limosus (Rafinesque, 1817): expansion in subalpine lakes in north-western Italy. Bioinvasions Rec., 2023, 12(2), 445-456, . [CrossRef]

- Delmastro, G.B. Annotazioni sulla storia naturale del Gambero della Louisiana Procambarus clarkii (Girard, 1852) in Piemonte centrale e prima segnalazione regionale del Gambero americano Orconectes limosus (Rafinesque, 1817) (Crustacea: Decapoda: Astacidea: Cambaridae). Rivista Piemont. Storia Nat., 1999, 20: 65-92.

- Bazzoni, P. Censimento e studio delle popolazioni di gambero d’acqua dolce nell’area del Verbano-Cusio-Ossola. Azienda Agricola Ossolana Acque 2006, 25 pp.

- Morpurgo, M.; Aquiloni, L.; Bertocchi, S.; Brusconi, S.; Tricarico, E.; Gherardi, F. Distribuzione dei gamberi d’acqua dolce in Italia. STSN, 2010, 87, 125–132.

- Boggero, A; Croci, C; Orlandi, M; Paganelli, D; Zaupa, S; Kamburska, L. (2025a). Invasive crayfish occurrence in the subalpine Lake Orta (NW Italy) in 2021-2022. Version 1.10. Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche - Istituto di Ricerca sulle Acque. Occurrence dataset . accessed via GBIF.org on 2025-10-30. [CrossRef]

- Boggero, A; Garzoli, L; Orlandi, M; Zaupa, S; Kamburska, L. (2025b). Invasive crayfish occurrence in the subalpine Lake Maggiore (NW Italy) in 2017-2018. Version 1.10. Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche - Istituto di Ricerca sulle Acque. Occurrence dataset . accessed via GBIF.org on 2025-10-30. [CrossRef]

- Kamburska, L.; Croci, C.; Orlandi, M.; Paganelli, D.; Zaupa, S.; Boggero, A. 2025. Occurrence of invasive Faxonius limosus in the subalpine Lake Mergozzo (NW-Italy) in 2021-2022. Version 1.8. Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche - Istituto di Ricerca sulle Acque. Occurrence datase. accessed via GBIF.org on 2025-10-30. [CrossRef]

- Delmastro, G.B. Sull’acclimatazione del gambero della Louisiana Procambarus clarkii (Girard, 1852) nelle acque dolci italiane (Crustacea: Decapoda: Cambaridae). Pianura - Suppl. di Provincia Nuova, Cremona, 1992, 4, 5-10.

- Delmastro, G.B. Il gambero della Louisiana, un nuovo abitatore delle nostre acque. Il Notiziario, Pro Natura Carmagnola, 1994, 19.

- Donato, R. Life history e struttura di popolazione di Procambarus clarkii (Girard, 1852) (Crustacea, Cambaridae) nel Parco Naturale del Lago di Candia (TO). Tesi di laurea magistrale, Università degli Studi di Torino, 122 pp., 2016.

- Regione Piemonte. 2017a. Piano di gestione: zona speciale di conservazione it1130004 - Lago di Bertignano e Stagni di Roppolo: 191 pp chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.regione.piemonte.it/giscartografia/Parchi/Piani/IT1130004_PdG_Relazione.pdf.

- Regione Piemonte. 2017b. Piano di gestione: zona speciale di conservazione e zona di protezione speciale it1110020 - Lago di Viverone: 184 pp chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.regione.piemonte.it/giscartografia/Parchi/Piani/IT1110020_PdG_Relazione.pdf.

- Delmastro, G.B. Il gambero della Louisiana Procambarus clarkii (Girard, 1852) in Piemonte: nuove osservazioni su distribuzione, biologia, impatto e utilizzo (Crustacea: Decapoda: Cambaridae). Rivista Piemont. Storia Nat., 2017, 38: 61-129.

- Città Metropolitana di Torino - Parco naturale Lago di Candia. 2019. Piano di gestione: zona speciale di conservazione (zsc) zona di protezione speciale (zps) it1110036 - Lago di Candia: 204 pp. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/http://www.cittametropolitana.torino.it/cms/risorse/natura/dwd/pdf/aree_protette/aree/candia/PdG/PdG__Relazione.pdf.

- Lo Parrino, E.; Ficetola, G.F.; Manenti, R.; Falaschi, M. Thirty years of invasion: the distribution of the invasive crayfish Procambarus clarkii in Italy. Biogeogr., 2020, 35, 43-50, . [CrossRef]

- Kamburska, L.; Sabatino, R.; Schiavetta, D.; De Santis, V.; Ferrari, E.; Mor, J.-R.; Zaupa, S.; Garzoli, L.; Boggero, A. A new misleading colour morph: is Marmorkrebs the only “marbled” crayfish? BioInvasions Rec., 2024, 13(4), 949-961, . [CrossRef]

- Candiotto, A.; Delmastro, G.B.; Dotti, L.; Sindaco, R. Pacifastacus leniusculus (Dana, 1852), un nuovo gambero esotico naturalizzato in Piemonte (Crustacea: Decapoda: Astacidae). Rivista Piemont. Storia Nat., 2010, 31, 73–82.

- Boggero, A.; Dugaro, M.; Migliori, L.; Garzoli, L. Prima segnalazione del gambero invasivo Pacifastacus leniusculus (Dana 1852) nel Lago Maggiore (Cantone Ticino, Svizzera). Bollettino della STSN, 2018, 106, 103-106.

- Kim, J.-H.; Nam, S.-H.; Kim, M.-K.; Serrano-Notivoli, R.; Tejedor, E. The 2022 record-high heat waves over southwestern Europe and their underlying mechanism. Weather Clim. Extremes, 2024, 46, 100729, . [CrossRef]

- Lake, P. S.; Palmer, M.A.; Biro, P.; Cole, J.; Covich, A.P.; Dahm, C.; Verhoeven, J.O.S. Global change and the biodiversity of freshwater ecosystems: impacts on linkages between above-sediment and sediment biota: all forms of anthropogenic disturbance—changes in land use, biogeochemical processes, or biotic addition or loss—not only damage the biota of freshwater sediments but also disrupt the linkages between above-sediment and sediment-dwelling biota. BioScience, 2000, 50(12), 1099-1107, . [CrossRef]

- Waters, M.N.; Piehler, M.F.; Rodriguez, A.B.; Smoak, J.M.; Bianchi, T.S. Shallow lake trophic status linked to late Holocene climate and human impacts. J. Paleolimnol., 2009, 42(1), 51-64, . [CrossRef]

| Lake name | State-Province | Protected status | Altitude | Lat N | Long E | Lake area | max Depth | Crayfish |

| Viverone | BI/TO/VC | SAC/SPA | 230 | 45°24′59.76″ | 08°02′08″ | 5.7 | 50 | PC |

| Alice S. | TO | SAC | 575 | 45°27′44.71″ | 07°47′43.58″ | 0.1 | 11 | -- |

| Avigliana G. | TO | SAC/SPA | 352 | 45°03′57.09″ | 07°23′13.73″ | 0.9 | 28 | PC |

| Avigliana P. | TO | SAC/SPA | 356 | 45°03’13’’ | 07°23’30’’ | 0.6 | 12 | -- |

| Bertignano | TO | SAC/SPA | 377 | 45°25′56″ | 08°03′44″ | 0.1 | 11 | PC |

| Campagna | TO | SAC/SPA | 238 | 45°29′02.4″ | 07°53′42″ | 0.1 | 5 | PC |

| Candia | TO | SAC/SPA | 226 | 45°19′25” | 07°54′43” | 1.5 | 8 | PC |

| Meugliano | TO | SAC | 715 | 45°28′36.33″ | 07°47′23.36″ | 0.03 | 11 | -- |

| Nero | TO | SAC/SPA | 342 | 45°30′17.43″ | 07°52′24″ | 0.1 | 27 | -- |

| Pistono | TO | SAC/SPA | 280 | 45°29′34.8″ | 07°52′28.2″ | 0.1 | 16 | PC |

| S. Michele | TO | SAC/SPA | 238 | 45°28′37.92″ | 07°53′16.8″ | 0.1 | 19 | PC |

| Sirio | TO | SAC/SPA | 266 | 45°29′13.2″ | 07°53′02.4″ | 0.3 | 44 | PC |

| Mergozzo | VCO | 204 | 45°57′20″ | 08°28′00″ | 1.8 | 73 | -- | |

| Moncrivello | VC | SAC/SPA | 263 | 45°20’24” | 07°59’32” | 0.03 | 2 | -- |

| Maglione | VC | SAC/SPA | 251 | 45°20’43” | 07°59’44” | 0.1 | 2 | -- |

| Orta | VCO/NO | 290 | 45°49′02″ | 08°24′24″ | 18.2 | 143 | FL, PC | |

| Maggiore | CH-VCO/NO/VA | 193 | 46°05′53″ | 08°42′53″ | 212.5 | 372 | FL, PC, PL |

| Taxon name cited | Update taxon name | Data format | Sampling method | Sites | Reference |

| O. limosus | F. limosus | O | traps | Baldissero pond | Delmastro, 1999 [39] |

| O. limosus | F. limosus | D | fishingnet, traps | lakes Maggiore, Orta | Bazzoni [40] |

| O. limosus | F. limosus | O | literature search, observations | Piedmont freshwaters | Morpurgo et al., 2010 [41] |

| O. limosus | F. limosus | D | traps | Lake Maggiore | Garzoli et al., 2020 [17] |

| F. limosus | -- | O | active search, traps | lakes Maggiore, Mergozzo, Orta | Boggero et al., 2023 [38] |

| F. limosus | -- | D | traps | Lake Orta | Boggero et al., 2025a [42] |

| F. limosus | -- | D | observation, traps | Lake Maggiore | Boggero et al., 2025b [43] |

| F. limosus | -- | D | traps | Lake Mergozzo | Kamburska et al., 2025 [44] |

| P. clarkii | -- | A, O | dip net, elettrofishing, observations | Venesima stream | Delmastro, 1992 [45] |

| P. clarkii | -- | O | observations | Piedmont freshwaters | Delmastro, 1994 [46] |

| P. clarkii | -- | O | observations | Piedmont freshwaters | Delmastro, 1999 [39] |

| P. clarkii | -- | O | literature search, observations | Piedmont freshwaters | Morpurgo et al., 2010 [41] |

| P. clarkii | -- | D | traps | Lake Candia | Donato, 2016 [47] |

| P. clarkii | -- | O | observations | lakes Bertignano, Viverone | Regione Piemonte, 2017a [48] |

| P. clarkii | -- | O | observations | Lake Viverone | Regione Piemonte, 2017b [49] |

| P. clarkii | -- | O | dip net, elettrofishing, fishing net, observations, torches, traces, traps | lakes Avigliana G., Campagna, Candia, Gay-Stroppiana, Maggiore, del Malpasso, Orta, Viverone | Delmastro, 2017 [50] |

| P. clarkii | -- | D | traps | Lake Candia | Donato et al., 2018 [36] |

| P. clarkii | -- | O | observations | Lake Candia | Città Metropolitana di Torino, 2019 [51] |

| P. clarkii | -- | O | literature search | Piedmont freshwaters | Lo Parrino et al., 2020 [52] |

| P. clarkii | -- | D | traps | Lake Orta | Kamburska et al., 2024 [53] |

| P. clarkii | -- | D | traps | Lake Orta | Boggero et al., 2025a [42] |

| P. clarkii | -- | D | observations, traps | Lake Orta | Boggero et al., 2025b [43] |

| P. leniusculus | -- | O | active search, observations | Valla stream | Candiotto et al., 2010 [54] |

| P. leniusculus | -- | O | observations | Lake Maggiore | Boggero et al., 2018 [55] |

| P. leniusculus | -- | D | active search, traps | rivers Valla and Erro | Larson et al., 2022 [37] |

| P. leniusculus | -- | D | observations, taps | Lake Maggiore | Boggero et al., 2025b [43] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).