Submitted:

16 April 2025

Posted:

17 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

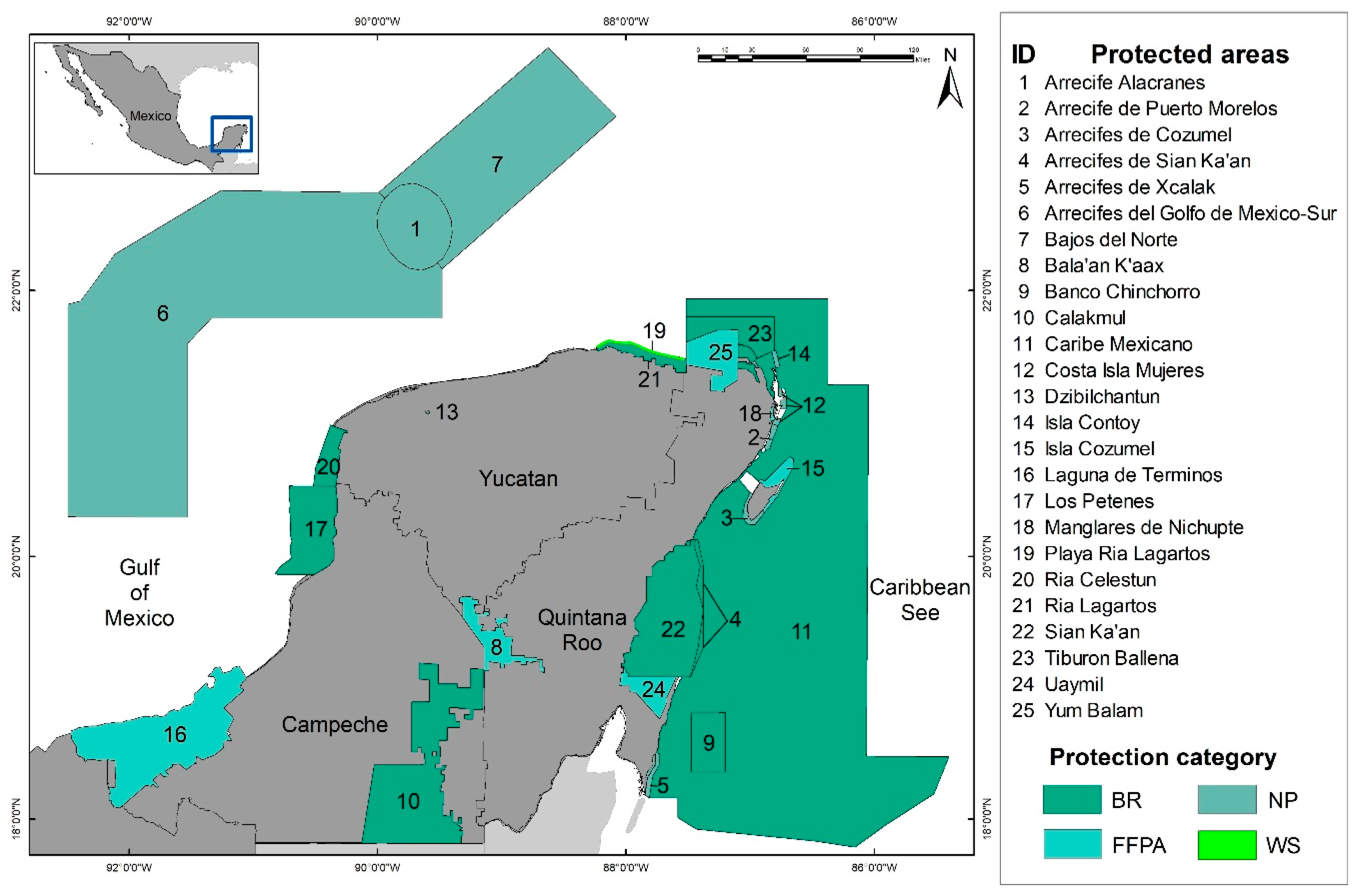

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Information Analysis

3. Results

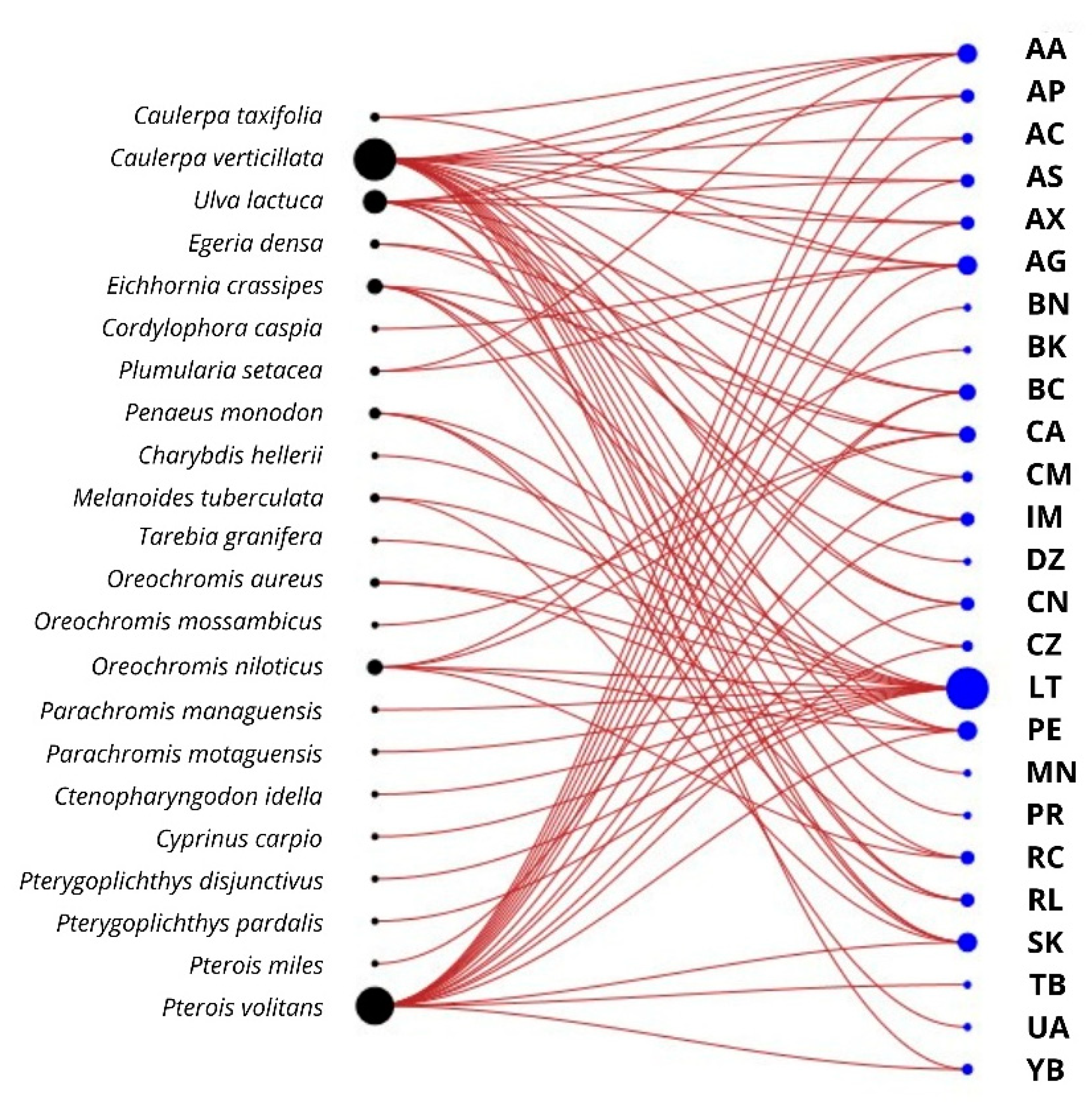

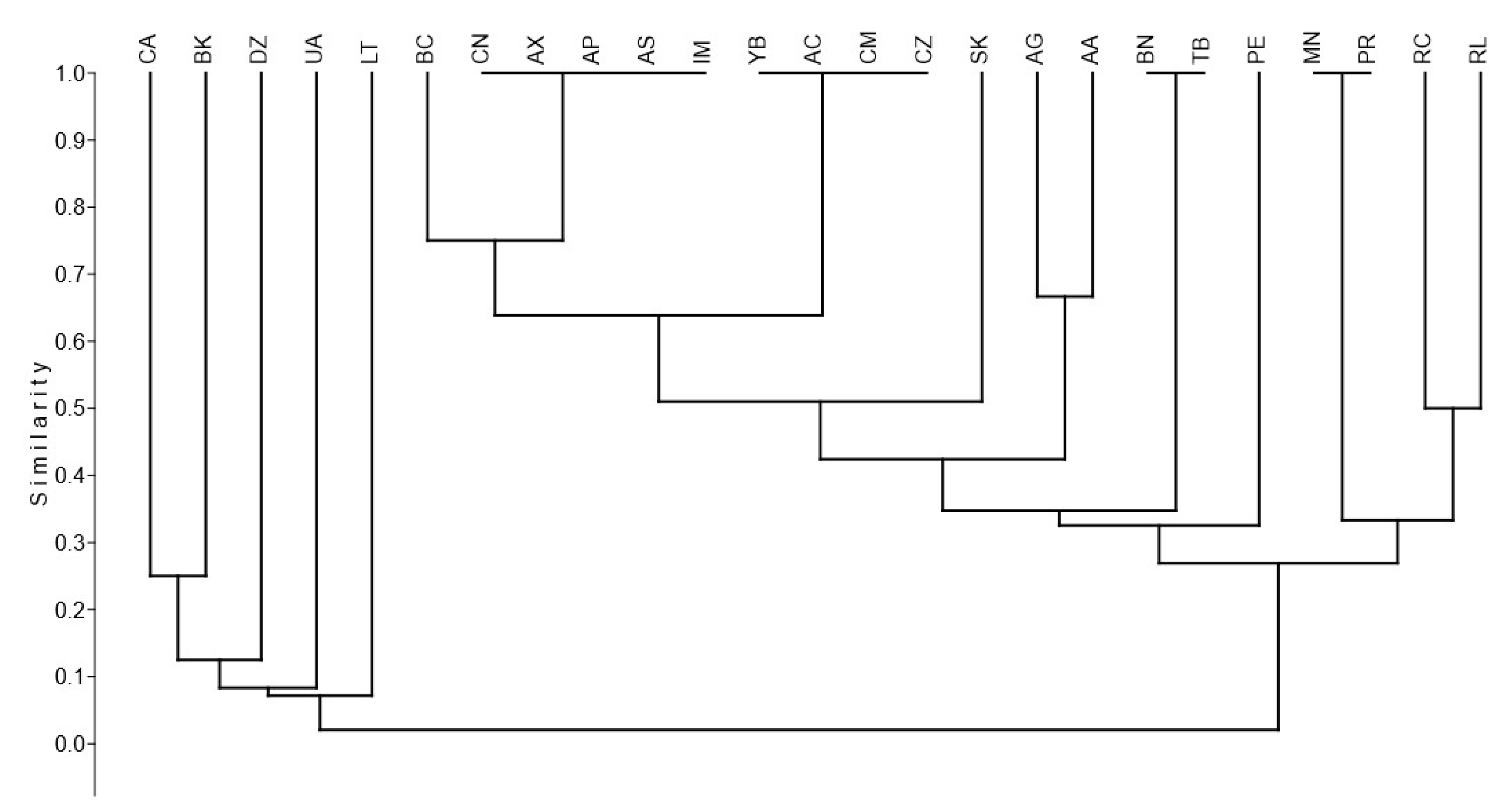

| Taxonomic Group | Family | Taxon | Protected Areas | Reference number |

| Macroalgae | Caulerpaceae |

Caulerpa taxifolia ▲ (M.Vahl) C.Agardh 1817 |

AA, AG | 25, 29, 48 |

|

Caulerpa verticillata ■ J. Agardh, 1847 |

AA, AP, AC, AS, AX, AG, BC, CM, IM, CN, CZ, PE, MN, PR, RC, RL, SK, YB | 25, 28, 29, 34, 35, 37, 38, 40, 41, 44, 45, 48, 54-56 |

||

| Ulvaceae |

Ulva Lactuca ● (Linnaeus, 1753) |

AA, AP, AS, AX, BC, IM, CN, RL, SK | 25, 26, 28, 29, 32, 34, 35, 44, 45, 56 |

|

| Plants | Hydrocharitaceae |

Egeria densa ▲ Planch. |

CA, DZ | 25, 39, 46 |

| Pontederiaceae |

Eichhornia crassipes ▲ (Mart.) Solms |

CA, LT, PE, SK, UA | 25, 34, 46, 57 | |

| Hydrozoans | Cordylophoridae |

Cordylophora caspia ▲ (Pallas, 1771) |

AG | 25, 26, 48 |

| Plumulariidae |

Plumularia setacea ■ (Linnaeus, 1758) |

AA, AG | 25, 26, 48 |

|

| Mollusks | Thiaridae |

Melanoides tuberculata ▲ (O. F. Müller, 1774) |

LT, SK |

25, 34, 58 |

|

Tarebia granifera ▲ (Lamarck, 1816) |

LT | 25, 58, 59 | ||

| Crustaceans | Penaeidae |

Penaeus monodon ▲ (Fabricius, 1798) |

LT, RC, RL | 25, 26, 56, 58, 60-63 |

| Portunidae | Charybdis (Charybdis) helleri ■ (A. Milne-Edwards, 1867) |

LT |

25, 64 |

|

| Fish | Cichlidae |

Oreochromis aureus ▲ (Steindachner, 1864) |

LT, PE | 25, 26, 65 |

|

Oreochromis mossambicus ▲ (Peters, 1852) |

CA |

25, 66 |

||

|

Oreochromis niloticus ▲ (Linnaeus, 1758) |

BK, CA, LT, PE, RC | 25, 31, 56, 65-68 |

||

|

Parachromis managuensis ■ (Günther, 1867) |

LT |

25, 58, 67, 69 | ||

|

Parachromis motaguensis ■ (Günther, 1867) |

25, 58 |

|||

| Cyprinidae |

Ctenopharyngodon idella ▲ (Valenciennes, 1844) |

25, 58, 67, 69 | ||

|

Cyprinus carpio ▲ (Linnaeus, 1758) |

25, 58 | |||

| Loricariidae |

Pterygoplichthys disjunctivus ▲ (Weber, 1991) |

25, 58, 67, 69-73 | ||

|

Pterygoplichthys pardalis ■ (Castelnau, 1855) |

25, 58, 67, 69-74 | |||

| Scorpaenidae |

Pterois miles ▲ (Bennett, 1828) |

BC | 75 | |

|

Pterois volitans ▲ (Linnaeus, 1758) |

AA, AP, AC, AS, AX, AG, BN, BC, CM, IM, CN, CZ, PE, SK, TB, YB |

25, 35-38, 40, 41, 47, 48, 72, 76-81 |

| Taxon | Pathways and vectors |

|

Caulerpa taxifolia ► |

Fishing nets, boat anchors, fishing equipment, pets trade, intentional release, improperly disposed waste from aquaria, internet sales |

| Caulerpa verticillata | Fisheries, boat anchors, trade for use in aquaria, intentional release |

| Ulva Lactuca | Ship ballast water and sediment, intentional release |

|

Egeria densa |

Trade for use in aquaria, improperly disposed waste from aquaria, it spreads by moving waters that carry whole plants or stem fragments to new locations |

|

Eichhornia crassipes ► |

Internet sales, popular ornamental plant for ponds, canoes and boats, unwanted plant material is discarded into creeks, rivers and dams |

| Cordylophora caspia | Aquaculture stock, ship hulls, ballast water, floating plant material, commercial oysters, dumping aquaria |

| Plumularia setacea | Fisheries, aquaculture, ballast water, dry ballast, biofouling, packing material |

| Melanoides tuberculata | Trade in aquarium plants and fish, aquaculture, ornamental purposes, flooding, internet sales |

| Tarebia granifera | Trade for use in aquaria, improperly disposed waste from aquaria |

| Penaeus monodon | Aquaculture, breeding and propagation, ship ballast water and sediment, research |

| Charybdis (Charybdis) helleri | Interconnected waterways, ship ballast water and sediment, hull fouling |

| Oreochromis aureus | Aquaculture, escape from confinement or garden escape, intentional release, live food trade, pet trade |

|

Oreochromis mossambicus ► |

Sport fishing, aquaculture, escape from confinement or garden escape, weed and midge control, research, intentional release, food for game fishes |

| Oreochromis niloticus | Fisheries, aquaculture, live food trade, escape from confinement or garden escape, intentional release |

| Parachromis managuensis | Trade for use in aquaria, aquaculture, escape from confinement or garden escape |

| Parachromis motaguensis | |

| Ctenopharyngodon idella | Weed control, aquaculture, sport fishing |

|

Cyprinus carpio ► |

Fisheries, aquaculture, intentional release, sport fishing, interconnected waterways, ornamental purposes, pet trade, escape from confinement or garden escape |

| Pterygoplichthys disjunctivus | Escapes from aquaculture farms, aquarium trade, intentional release, live food trade |

| Pterygoplichthys pardalis | |

| Pterois miles | Pet trade, intentional release, ship ballast water and sediment (eggs and larvae), hurricanes |

| Pterois volitans |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blackburn TM, Bellard C, Ricciardi A (2019) Alien versus native species as drivers of recent extinctions. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 17(4): 203–207. [CrossRef]

- Pyšek P, Hulme PE, Simberloff D, Bacher S, Blackburn TM, Carlton JT, Dawson W, Essl F, Foxcroft LC, Genovesi P, Jeschke JM, Kühn I, Liebhold AM, Mandrake NE, Meyerson LA, Pauchard A, Pergl J, Roy HE, Seebens H, van Kleunen M, Vilà M, Wingfield MJ, Richardson DM (2020) Scientists’ warning on invasive alien species. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 95(6): 1511–1534. [CrossRef]

- IPBES (2023) Thematic assessment report on invasive alien species and their control of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. [CrossRef]

- Gallardo B, Clavero M, Sánchez MI, Vilà M (2016) Global ecological impacts of invasive species in aquatic ecosystems. Global Change Biology 22: 151–163. [CrossRef]

- Meira A, Carvalho F, Castro P, Souza R (2024) Applications of biosensors in non-native freshwater species: a systematic review. NeoBiota 96: 211–236. [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert RN, Pattison Z, Taylor NG, Verbrugge L, Diagne C, Ahmed DA, Leroy B, Angulo E, Briski E, Capinha C, Catford JA, Dalu T, Essl F, Gozlan RE, Haubrock PJ, Kourantidou M, Kramer AM, Renault D, Wasserman RJ, Courchamp F (2021) Global economic costs of aquatic invasive alien species, Science of The Total Environment 775, 145238. [CrossRef]

- Rico-Sanchez AE, Haubrock PJ, Cuthbert RN, Angulo E, Ballesteros-Mejia L, Lopez-Lopez E, Duboscq-Carra VG, Nunez MA, Diagne C, Courchamp F (2021) Economic costs of invasive alien species in Mexico. In: Zenni RD, McDermott S, Garcia-Berthou E, Essl F. (Eds) The economic costs of biological invasions around the world. NeoBiota 67: 459–483. [CrossRef]

- Perrin SW, Lundmark C, Wenaas CP, Finstad AG (2024) Contrasts in perception of the interaction between non-native species and climate change. NeoBiota 96: 343–361. [CrossRef]

- Seebens H, Bacher S, Blackburn TM, Capinha C, Dawson W, Dullinger S, Genovesi P, Hulme PE, van Kleunen M, Kühn I, Jeschke JM, Lenzner B, Liebhold AM, Pattison Z, Pergl J, Pyšek P, Winter M, Essl F (2021) Projecting the continental accumulation of alien species through to 2050. Global Change Biology 27: 970-982. [CrossRef]

- Vitousek PM, D’Antonio CM, Loope LL, Rejmánek M, Westbrooks R (1997) Introduced species: A significant component of human-caused global change. New Zealand Journal of Ecology 21(1): 1-16. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24054520.

- Havel JE, Kovalenko KE, Thomaz SM, Amalfitano S, Kats LB (2015) Aquatic invasive species: Challenges for the future. Hydrobiologia 750: 147–170. [CrossRef]

- Saunders DL, Meeuwig JJ, Vincent AC (2002). Freshwater protected areas: Strategies for conservation. Conservation Biology 16(1): 30–41. [CrossRef]

- Kiruba-Sankar R, Praveen J, Saravanan K, Lohith K, Raymond J, Velmurugan A, Dam S (2018) Invasive species in freshwater ecosystems – threats to ecosystem services. In: Sivaperuman C, Velmurugan A, Kumar A, Jaisankar I (Eds). Biodiversity and climate change adaptation in tropical islands, 257–296. [CrossRef]

- Baxter CV, Fausch KD, Murakami M, Chapman PL (2004) Fish invasion restructures stream and forest food webs by interrupting reciprocal prey subsidies. Ecology 85(10): 2656–2663. [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis C, Fournari-Konstantinidou I, Sourbès L, Koutsoubas D, Katsanevakis S (2021) Long term interactions of native and invasive species in a marine protected area suggest complex cascading effects challenging conservation outcomes. Diversity 13(71). [CrossRef]

- Bax N, Williamson A, Agüero M, Gonzalez E, Geeves W (2003) Marine invasive alien species: A threat to global biodiversity, Marine Policy 27(4): 313-323. [CrossRef]

- Foxcroft LC, Richardson DM, Pyšek P, Genovesi P (2013) Invasive alien plants in protected areas: Threats, opportunities, and the way forward. In: Foxcroft LC, Richardson DM, Pyšek P, Genovesi P (Eds) Plant invasions in protected areas, invading nature - Springer Series in Invasion Ecology 7: 621–639. [CrossRef]

- Braun M, Schindler S, Essl F (2016) Distribution and management of invasive alien plant species in protected areas in Central Europe. Journal for Nature Conservation 33, 48–57. [CrossRef]

- Holenstein K, Simonson WD, Smith KG, Blackburn TM, Charpentier A (2021) Non-native species surrounding protected areas influence the community of non-native species within them. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 8:625137. [CrossRef]

- CONABIO [Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad] (1997) Provincias biogeográficas de México, escala 1: 4,000,000. Available online: http://geoportal.conabio.gob.mx/descargas/mapas/imagen/96/rbiog4mgw (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Arriaga L, Aguilar V, Alcocer J (2002) Aguas continentales y diversidad biológica de México. CONABIO, México. https://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/pais/regiones-hidrologicas-prioritarias-de-Mexico.

- Arriaga L, Vázquez E, González J, Jiménez R, Muñoz E, Aguilar V (1998) Regiones marinas prioritarias de México. CONABIO, México. https://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/pais/regiones-marinas-prioritarias-de-mexico.

- Arriaga L, Espinoza-Rodríguez JM, Aguilar-Zúñiga C, Martínez-Romero E, Gómez-Mendoza L, Loa E (2000) Regiones terrestres prioritarias de México. CONABIO, México. https://bioteca.biodiversidad.gob.mx/janium-bin/detalle.pl?Id=20250103185318.

- CONANP [Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas] (2025) Listado de las áreas naturales protegidas de México. Available online: https://sig.conanp.gob.mx/General (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- CONABIO [Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad] (2025) Sistema Nacional de Información sobre Biodiversidad. Available online: https://www.snib.mx/ (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- GBIF [Global Biodiversity Information Facility] (2025) GBIF México.

- Available online: https://www.gbif.org/ (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- CONANP [Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas] (2000) Programa de Manejo Reserva de la Biosfera Ría Celestún. CONANP, México. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/que_hacemos/pdf/programas_manejo/celestun.pdf.

- CONANP [Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas] (2004) Programa de Manejo Parque Nacional Arrecifes de Xcalak. CONANP, México, 161 pp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/que_hacemos/pdf/programas_manejo/Xcalak_ok.pdf.

- CONANP [Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas] (2006a) Programa de Conservación y Manejo Parque Nacional Arrecife Alacranes. CONANP, México, 165 pp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/que_hacemos/pdf/programas_manejo/alacranes_ok.pdf.

- CONANP [Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas] (2006b) Programa de Conservación y Manejo Reserva de la Biosfera Los Petenes. CONANP, México, 203 pp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/que_hacemos/pdf/programas_manejo/petenes_final.pdf.

- CONANP [Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas] (2007a) Programa de Conservación y Manejo Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Bala’an K’aax. CONANP, México, 169 pp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/que_hacemos/pdf/programas_manejo/Final_BallanKaxx.pdf.

- CONANP [Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas] (2007b) Programa de Conservación y Manejo Reserva de la Biosfera Ría Lagartos. CONANP, México, 266 pp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/anp/consulta/PCM_RiaLagartos.pdf.

- CONANP [Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas] (2014a) Programa de Manejo Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Manglares de Nichupté. CONANP, México, 137 pp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/que_hacemos/pdf/programas_manejo/2015/Manglares_de_Nichupt%C3%A9.pdf.

- CONANP [Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas] (2014b) Programa de Manejo Complejo Sian Ka’an: Reserva de la Biosfera Sian Ka’an, Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Uaymil y Reserva de la Biosfera Arrecifes de Sian Ka’an. CONANP, México, 481 pp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/que_hacemos/pdf/programas_manejo/2015/Complejo_Sian_Ka_an.pdf.

- CONANP [Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas] (2015a) Programa de Manejo Parque Nacional Isla Contoy. CONANP, México, 215 pp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/que_hacemos/pdf/programas_manejo/2015/Isla_Contoy_completo.pdf.

- CONANP [Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas] (2015b) Programa de Manejo Reserva de la Biosfera Tiburón Ballena. CONANP, México, 162 pp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/que_hacemos/pdf/programas_manejo/2015/Tiburon_Ballena_Libro.pdf.

- CONANP [Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas] (2016a) Programa de Manejo Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna La Porción Norte y la Franja Costera Oriental, Terrestres y Marinas de la Isla de Cozumel. CONANP, México, 243 pp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/que_hacemos/pdf/programas_manejo/2017/Isla%20Cozumel%20(completo).pdf.

- CONANP [Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas] (2016b) Programa de Manejo Parque Nacional Costa Occidental de Isla Mujeres, Punta Cancún y Punta Nizuc. CONANP, México, 228 pp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/que_hacemos/pdf/programas_manejo/2017/Isla%20Mujeres%20Punta%20Canc%C3%BAn.pdf.

- CONANP [Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas] (2016c) Programa de Manejo Parque Nacional Dzibilchantún. CONANP, México, 171 pp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/acciones/pdf/PMDZIBILCHANTUNCompleto.pdf.

- CONANP [Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas] (2019a) Programa de Manejo Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Yum Balam. CONANP, México, 284 pp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/programademanejo/PMYumBalam.pdf.

- CONANP [Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas] (2019b) Programa de Manejo Reserva de la Biosfera Caribe Mexicano. CONANP, México, 366 pp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/programademanejo/PMCaribeMexicano.pdf.

- INE [Instituto Nacional de Ecología] (1997) Programa de Manejo del Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Laguna de Términos. INE, México, 167 pp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/que_hacemos/pdf/programas_manejo/APFFTerminos.pdf.

- INE [Instituto Nacional de Ecología] (1998) Programa de Manejo Parque Marino Nacional Arrecifes de Cozumel. INE, México, 164 pp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/que_hacemos/pdf/programas_manejo/cozumel.pdf.

- INE [Instituto Nacional de Ecología] (2000a) Programa de Manejo Parque Nacional Arrecife de Puerto Morelos. INE, México, 223 pp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/que_hacemos/pdf/programas_manejo/puerto_morelos.pdf.

- INE [Instituto Nacional de Ecología] (2000b) Programa de Manejo Reserva de la Biosfera Banco Chinchorro. INE, México, 189 pp.https://www.conanp.gob.mx/que_hacemos/pdf/programas_manejo/chinchorro.pdf.

- INE [Instituto Nacional de Ecología] (2000c) Programa de Manejo Reserva de la Biosfera Calakmul, México. INE, 268 pp.https://www.conanp.gob.mx/que_hacemos/pdf/programas_manejo/calakmul.pdf.

- CONANP [Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas] (2023) Estudio Previo Justificativo para el establecimiento del Área Natural Protegida Parque Nacional Bajos del Norte, Golfo de México. CONANP, México, 171 pp.https://www.conanp.gob.mx/pdf/separata/EPJ-PN-BajosDelNorte.pdf.

- CONANP [Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas] (2024) Estudio Previo Justificativo para el establecimiento del Área Natural Protegida Arrecifes del Golfo de México-Sur, México. CONANP, México, 383 pp. https://www.conanp.gob.mx/pdf/separata/EPJ-PN-ArrecifesDelGolfoDeMexico-Sur.pdf.

- GISD [Global Invasive Species Database] (2025) Global Invasive Species Database. Available online: https://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- CABI [Centre for Agricultural Bioscience International] (2025) Compendium Invasive Species. Available online: https://www.cabi.org/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- CONABIO [Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad] (2015) Método de Evaluación Rápida de Invasividad (MERI) para especies exóticas en México. https://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/media/1/especies/Invasoras/files/Instrutivo_MERI_2020.pdf.

- PAST Core Team (2025) PAST: A software for scientific data analysis. https://www.nhm.uio.no/english/research/resources/past/.

- CBD [Convention on Biological Diversity] (2014) UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/18/9/Add.1. Pathways of introduction of invasive alien species, their prioritization and management. https://www.cbd.int/doc/meetings/sbstta/sbstta-18/official/sbstta-18-09-add1-en.pdf.

- Collado-Vides L, González-González J, Ezcurra E (1995) Patrones de distribución ficofloristica en el sistema lagunar de Nichupté, Quintana Roo, México. Acta Botánica Mexicana 31: 19-32. [CrossRef]

- Espinoza-Avalos J, Aguilar-Rosas LE, Aguilar-Rosas R, Gómez-Poot JM, Raigoza-Figueras R (2015) Presencia de caulerpaceae (Chlorophyta) en la Península de Yucatán, México. Botanical Sciences 93(4): 845-854. [CrossRef]

- Rendón-Hernández E, Ayala-Pérez LA, Golubov J, Torres-Lara R (2024) Especies exóticas invasoras y sus implicaciones sobre los bosques de manglar en las Reservas de la Biosfera Ría Celestún y Ría Lagartos. Madera y Bosques 30(4). [CrossRef]

- Endañú-Huerta E, López-Contreras JE, Amador-Del Ángel LE, Guevara-Carrió E, Alderete-Chávez A, Brito-Pérez R (2015) Flora exótica naturalizada e invasora del Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Laguna de Términos, Campeche: Estado actual, impactos, necesidades y perspectivas. In: Amador-Del Ángel LE, Frutos-Cortés M (Eds) Problemas contemporáneos regionales del Sureste Mexicano El caso del estado de Campeche. Universidad Autónoma del Carmen, México, 280-307.

- Amador-Del Ángel LE, Endañú-Huerta E, López-Contreras JE, Wakida-Kusunoki AT, Guevara-Carrió E, Brito-Pérez R (2015) Fauna exótica establecida e invasora en el Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Laguna de Términos, Campeche: Estado actual, impactos, necesidades y perspectivas. In: Amador-Del Ángel LE, Frutos-Cortés M (Eds) Problemas contemporáneos regionales del Sureste Mexicano El caso del estado de Campeche. Universidad Autónoma del Carmen, México, 128-154.

- Trinidad-Ocaña C, Juárez-Flores J, Sánchez AJ, Barba-Macías E (2018) Diversidad de moluscos y crustáceos acuáticos en tres zonas en la cuenca del Río Usumacinta, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 89: S65-S78. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ponce MA, Bolaños-Martínez N, Díaz-Jaimes P, Bortolini-Rosales JL, Castellanos P (2020) A new record of a tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon Fabricius, 1798 breeding female in the coast of Campeche, Mexico. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research 48(1): 150-155. [CrossRef]

- Wakida-Kusunoki AT, Rojas-González RI, González-Cruz A, Del Ángel A, Sánchez-Cruz JL, López NA (2013) Presence of giant tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon Fabricius, 1798 on the Mexican coast of the Gulf of Mexico. BioInvasions Records, 2(4): 325–328. [CrossRef]

- Wakida-Kusunoki AT, De Anda-Fuentes D, López-Téllez NA (2016) Presence of giant tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon (Fabricius, 1798) in eastern Peninsula of Yucatan coast, Mexico. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research 44(1): 155-158. [CrossRef]

- Wakida-Kusunoki AT, Cruz-Sánchez JL, López-Téllez NA (2021) A review of recent sightings and reports of the giant tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon (Decapoda: Penaeidae) on the Mexican coast of the Gulf of Mexico (2012-2019). Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía 56 (1): 83-88. [CrossRef]

- Simoes N, Wakida-Kusunoki AT, Cruz-Sánchez JL, Alvarez F, Villalobos-Hiriart JL (2019) On the presence of Charybdis (Charybdis) hellerii (A. Milne-Edwards, 1867) on the Mexican coast of the Gulf of Mexico. BioInvasions Records 8(3): 670–674. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Castro IL, Vega-Cendejas MA, Schmitter-Soto JJ, Palacio-Aponte G, Rodiles-Hernández R (2009) Ictiofauna de sistemas cárstico-palustres con impacto antrópico: Los petenes de Campeche, México. Revista de Biología Tropical 57(1-2): 141-157.https://www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?pid=S0034-77442009000100014&script=sci_arttext.

- Vega-Cendejas MA (2010) Estudio de caso: los peces de la Reserva de Calakmul. In: Villalobos-Zapata GJ, Mendoza J (Coord) La Biodiversidad en Campeche: Estudio de Estado. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, Gobierno del Estado de Campeche, Universidad Autónoma de Campeche, El Colegio de la Frontera Sur. México, 729 pp.https://bioteca.biodiversidad.gob.mx/janium/Documentos/7371.pdf.

- Amador-Del Ángel LE, Wakida-Kusunoki AT, Guevara-Carrió EC, Brito-Pérez R, Cabrera-Rodríguez P (2009) Peces invasores de agua dulce en la región de la Laguna de Términos, Campeche. UNACAR Tecnociencia 3(2): 11-28.https://biblat.unam.mx/hevila/UNACARtecnociencia/2009/no2/2.pdf.

- Ayala-Pérez LA, Ramos-Miranda J, Flores-Hernández, D (2003) La comunidad de peces de la Laguna de Términos: estructura actual comparada. Biología Tropical 50(3-4): 783-793. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44911882020.

- Amador-Del Ángel LE, Guevara E, Brito R, Wakida-Kusunoki AT, Cabrera-Rodríguez P (2012) Aportaciones recientes al estudio de la ictiofauna del Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Laguna de Términos, Campeche. In: Ruíz A, Canedo Y, Zavala JC, Campos SC, Sabido MY, Ayala LA, Amador-Del Ángel LE (Eds) Aspectos hidrológicos y ambientales en la Laguna de Términos. Universidad Autónoma del Carmen, México, 128-154.

- Álvarez-Pliego N, Sánchez AJ, Florido R, Salcedo MA (2015) First record of South American suckermouth armored catfishes (Loricariidae, Pterygoplichthys spp.) in the Chumpan River system, southeast Mexico. BioInvasions Records 4(4): 309–314. [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Pérez LA, Pineda-Peralta AD, Álvarez-Guillen H, Amador-Del Ángel LE (2014) El pez diablo (Pterygoplichthys spp.) en las cabeceras estuarinas de la Laguna de Términos, Campeche. In: Low A, Quijón P, Peters E (Eds) Especies Invasoras Acuáticas: Casos de Estudio en Ecosistemas de México. Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, Instituto Nacional de Ecología y Cambio Climático, University of Prince Edward Island, México, 313-336. https://agua.org.mx/biblioteca/especies-invasoras-acuaticas-casos-de-estudio-en-ecosistemas-de-mexico-2/.

- Rendón E, Bernal JF, Hernández B, Müller E (2017) Estrategias de atención a especies exóticas invasoras en áreas naturales protegidas de competencia federal en México. In: Born-Schmidt G, de Alba F, Parpal J, Koleff P (Coord) Principales retos que enfrenta México ante las especies exóticas invasoras. Centro de Estudios Sociales y de Opinión Pública, Cámara de Diputados, México, 209-224.http://www5.diputados.gob.mx/index.php/esl/Centros-de-Estudio/CESOP/Novedades/Libro.-Principales-retos-que-enfrenta-Mexico-ante-las-especies-exoticas-invasoras.

- Wakida-Kusunoki AT, Amador-Del Ángel LE (2008) Nuevos registros de los plecos Pterygoplichthys pardalis (Castelnau 1855) y P. disjunctivus (Weber 1991) (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) en el Sureste de México. Hidrobiológica 18(3): 251-256. https://hidrobiologica.izt.uam.mx/index.php/revHidro/article/view/916.

- Toro-Ramírez A, Wakida-Kusunoki AT, Amador-Del Ángel LE, Cruz-Sánchez JL (2014) Common snook [Centropomus undecimalis (Bloch, 1792)] preys on the invasive Amazon sailfin catfish [Pterygoplichthys pardalis (Castelnau, 1855)] in the Palizada River, Campeche, southeastern Mexico. Journal of Applied Ichthyology 30: 532–534. [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Méndez IA, Rivera-Madrid R, Díaz-Jaimes P, García-Rivas MC, Aguilar-Espinosa M, Arias-González JE (2017) First genetically confirmed record of the invasive devil firefish Pterois miles (Bennett, 1828) in the Mexican Caribbean. BioInvasions Records 6(2): 99–103. [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Perera A, Tuz-Sulub A (2010) Non-native, invasive red lionfish (Pterois volitans [Linnaeus, 1758]: Scorpaenidae), is first recorded in the southern Gulf of Mexico, off the northern Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Aquatic Invasions 5(1): S9-S12. [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Perera A, Quijano-Puerto L, Hernández-Landa RC (2017) Lionfish invaded the mesophotic coral ecosystem of the Parque Nacional Arrecife Alacranes, Southern Gulf of Mexico. Marine Biodiversity 47: 15–16. [CrossRef]

- Arias-González JE, González-Gándara C, Cabrera JL, Christensen V (2011) Predicted impact of the invasive lionfish Pterois volitans on the food web of a Caribbean coral reef. Environmental Research 111(7): 917–925. [CrossRef]

- Arredondo-Chávez AT, Sánchez-Jiménez JA, Ávila-Morales OG, Torres-Chávez P, Herrerias-Diego Y, Medina-Nava M, Madrigal-Gurdi X, Campos-Mendoza A, Domínguez-Domínguez O, Caballero-Vázquez JA (2016) Spatio-temporal variation in the diet composition of red lionfish, Pterois volitans (Actinopterygii: Scorpaeniformes: Scorpaenidae), in the Mexican Caribbean: Insights into the ecological effect of the alien invasion. Acta Ichthyologica Et Piscatoria 46(3): 185–200. [CrossRef]

- Cobián-Rojas D, Schmitter-Soto JJ, Aguilar CM, Aguilar-Perera A, Ruiz-Zárate MA, González-Sansón G, Chevalier PP, Herrera R, García A, Corrada RI, Cabrera D, Salvat H, Perera S (2018) The community diversity of two Caribbean MPAs invaded by lionfish does not support the biotic resistance hypothesis. Journal of Sea Research 134: 26–33. [CrossRef]

- Loreto-Viruel RM, Rendón-Hernández E, Espindola S (2023) Plan de acción nacional para el manejo y control del pez león en México. Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas. Amigos de Sian Ka’an, A.C. Mesoamerican Reef Fund, México, 77 pp.https://marfund.org/es/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Mexico-Plan-Accion_Pez-leon_feb23_opt.pdf.

- Lowe S, Browne M, Boudjelas S, De Poorter M (2004) 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species A selection from the Global Invasive Species Database. World Conservation Union, New Zealand, 12pp.https://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/pdf/100English.pdf.

- JTMD [Japanese Tsunami Marine Debris] (2025) JTMD Species Summary (Plumularia setacea). Available online: https://invasions.si.edu/nemesis/jtmd/species_summary/plumularia%20setacea (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Hulme PE, Bacher S, Kenis M, Klotz S, Kühn I, Minchin D, Nentwig W, Olenin S, Panov V, Pergl J, Pyšek P, Roques A, Sol D, Solarz W, Vilà M (2008) Grasping at the routes of biological invasions: a framework for integrating pathways into policy. Journal of Applied Ecology 45: 403–414. [CrossRef]

- CBD [Convention on Biological Diversity] (2025) Understanding pathways of introduction and their identification. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/invasive/toolkit/doc/pathways-training-en.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Lipinskaya T, Semenchenko V, Minchin D (2020) A pathways risk assessment of aquatic non-indigenous macroinvertebrates passing to, and through, the Central European invasion corridor. Management of Biological Invasions 11(3): 525–540. [CrossRef]

- Pergl J, Brundu G, Harrower CA, Cardoso AC, Genovesi P, Katsanevakis S, Lozano V, Perglová I, Rabitsch W, Richards G, Roques A, Rorke SL, Scalera R, Schönrogge K, Stewart A, Tricarico E, Tsiamis K, Vannini A, Vilà M, Zenetos A, Roy HE (2020) Applying the Convention on Biological Diversity Pathway Classification to alien species in Europe. In: Wilson JR, Bacher S, Daehler CC, Groom QJ, Kumschick S, Lockwood JL, Robinson TB, Zengeya TA, Richardson DM (Eds) Frameworks used in Invasion Science. NeoBiota 62: 333–363. [CrossRef]

- Turbelin AJ, Diagne C, Hudgins EJ, Moodley D, Kourantidou M, Novoa A, Haubrock PJ, Bernery C, Gozlan RE, Francis RA, Courchamp F (2022) Introduction pathways of economically costly invasive alien species. Biol Invasions, 24: 2061–2079. [CrossRef]

- Côté IM, Green SJ, Hixon MA (2013) Predatory fish invaders: Insights from Indo-Pacific lionfish in the western Atlantic and Caribbean. Biological Conservation, 164: 50–61. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).