Submitted:

16 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- S = Species richness

- L = Species number, present only in one sample

- M = Species number present in two samples

- S = Species richness

- L = Species number, present only in one sample

- M = Sample number

- S = Species richness

- pj = Proportion of sampled units where the jth species is present

3. Results

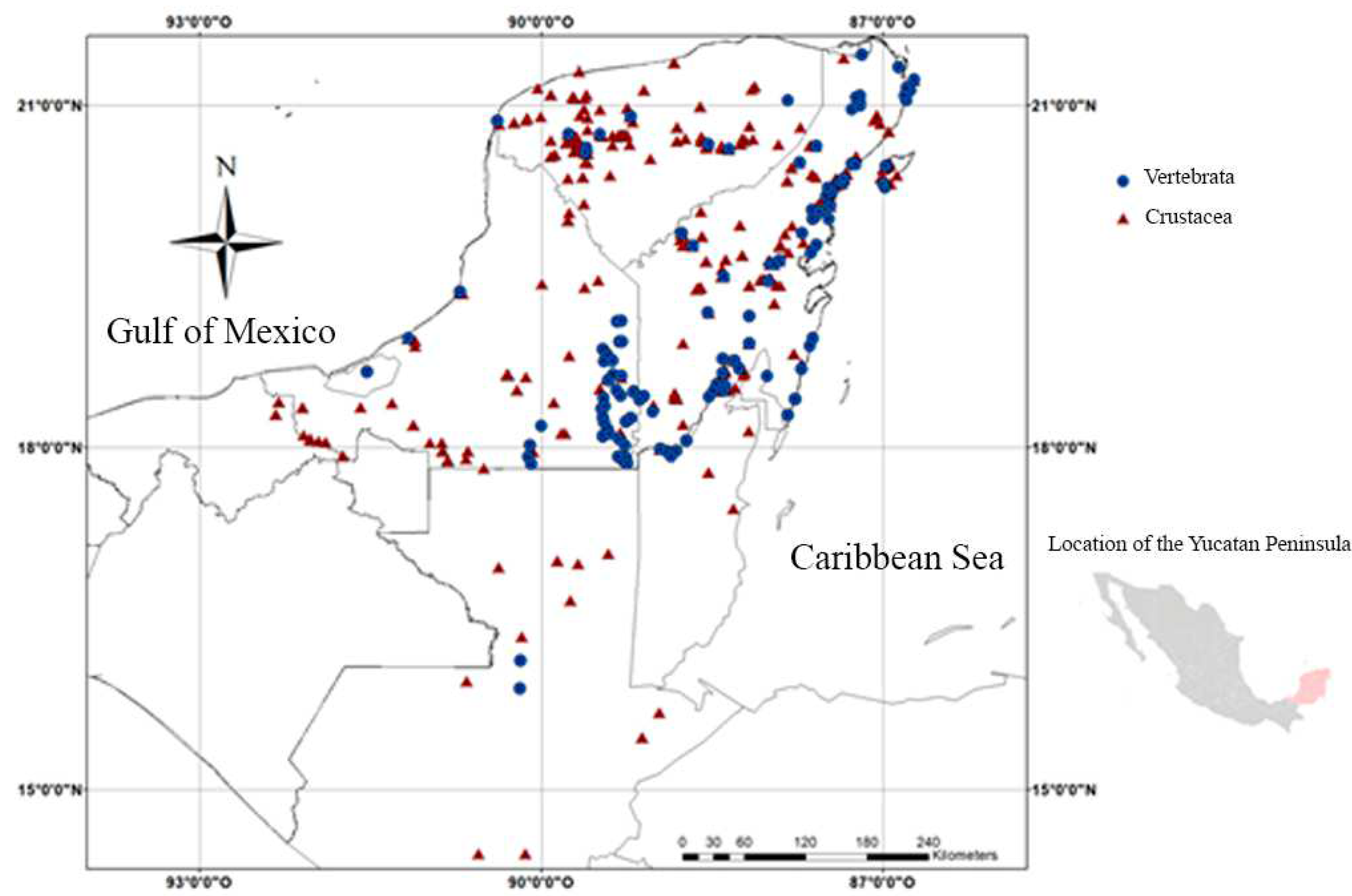

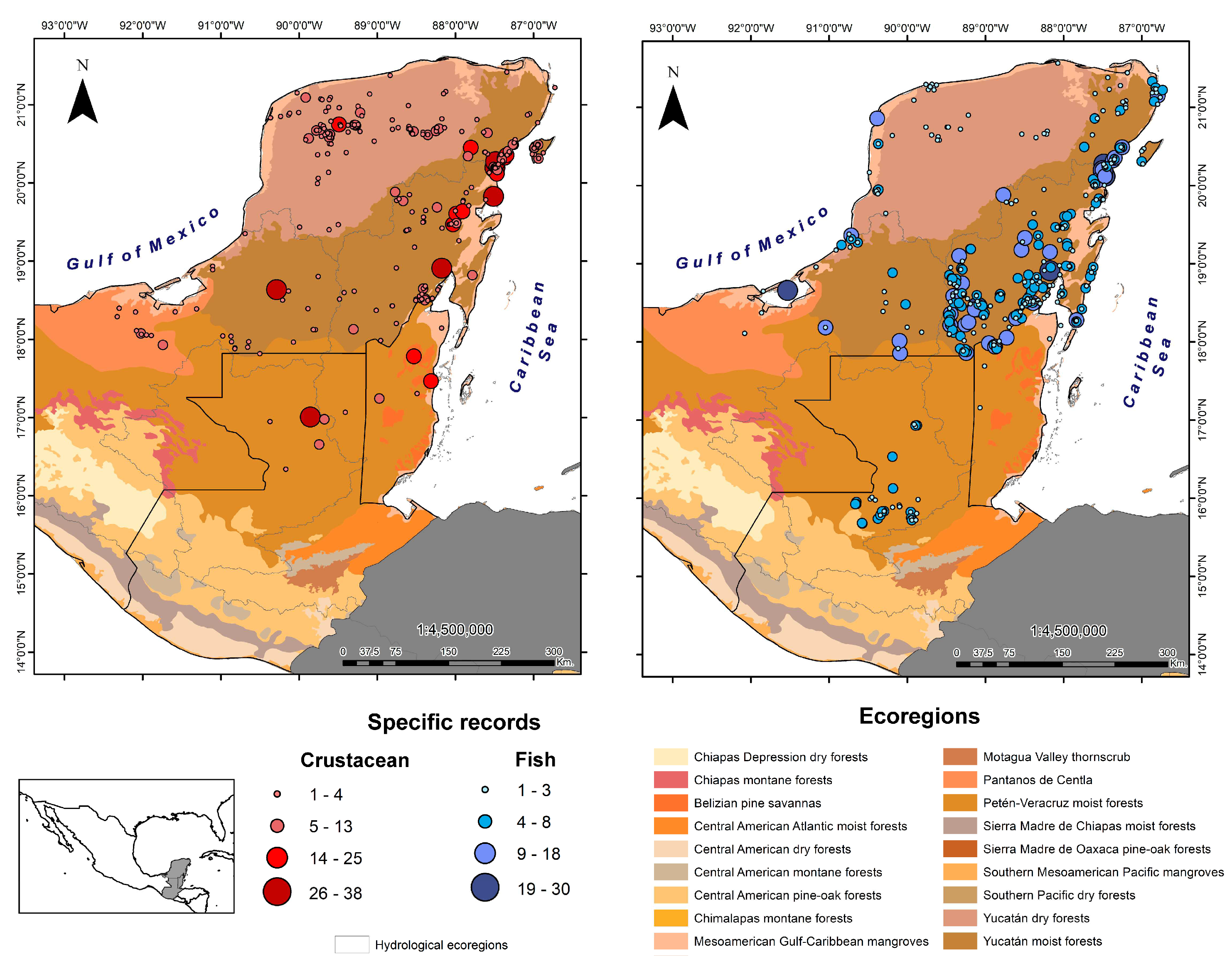

3.1. Records

3.2. Species and Taxonomic Categories

3.3. Frequency of Richness

3.4. Endemic Species

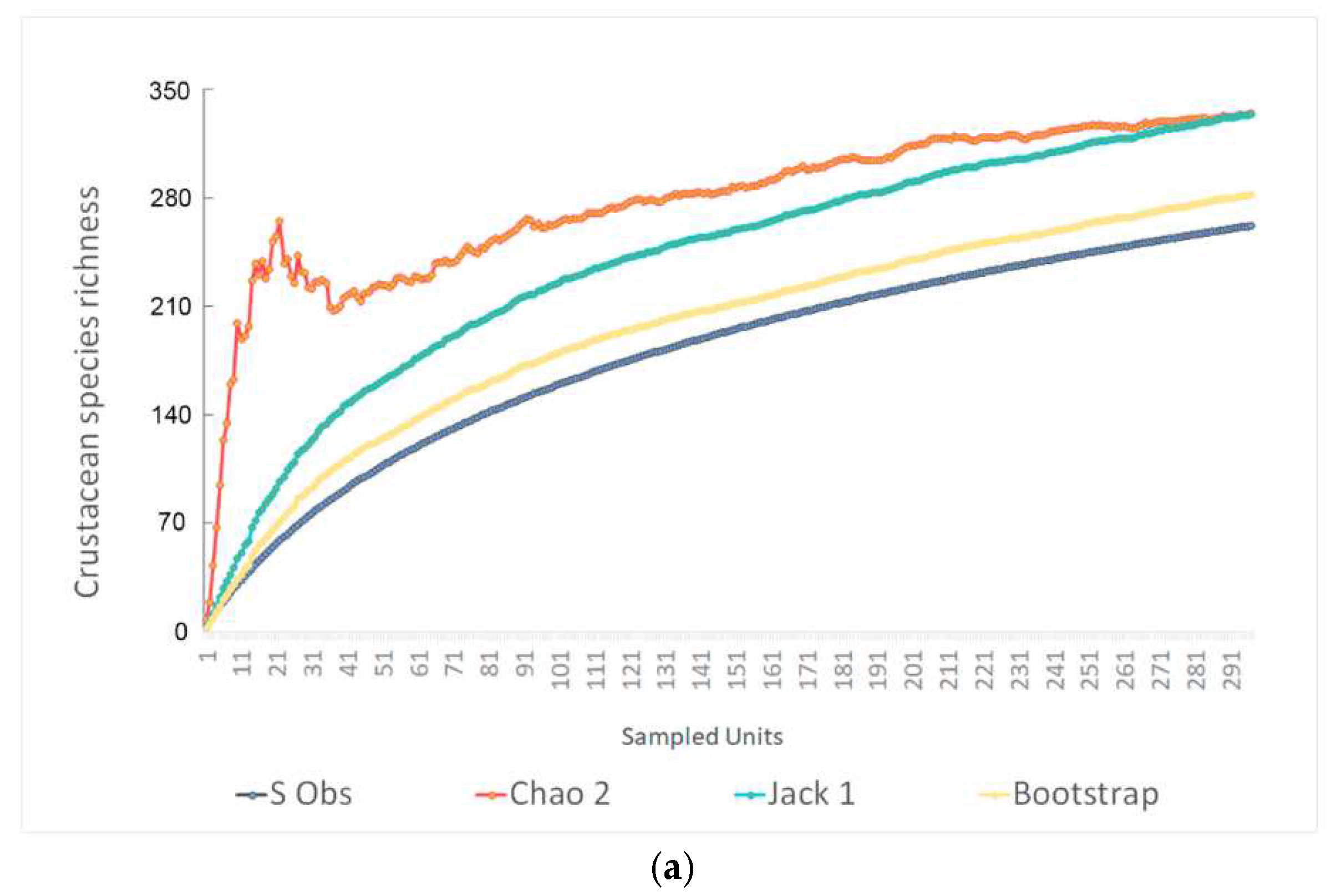

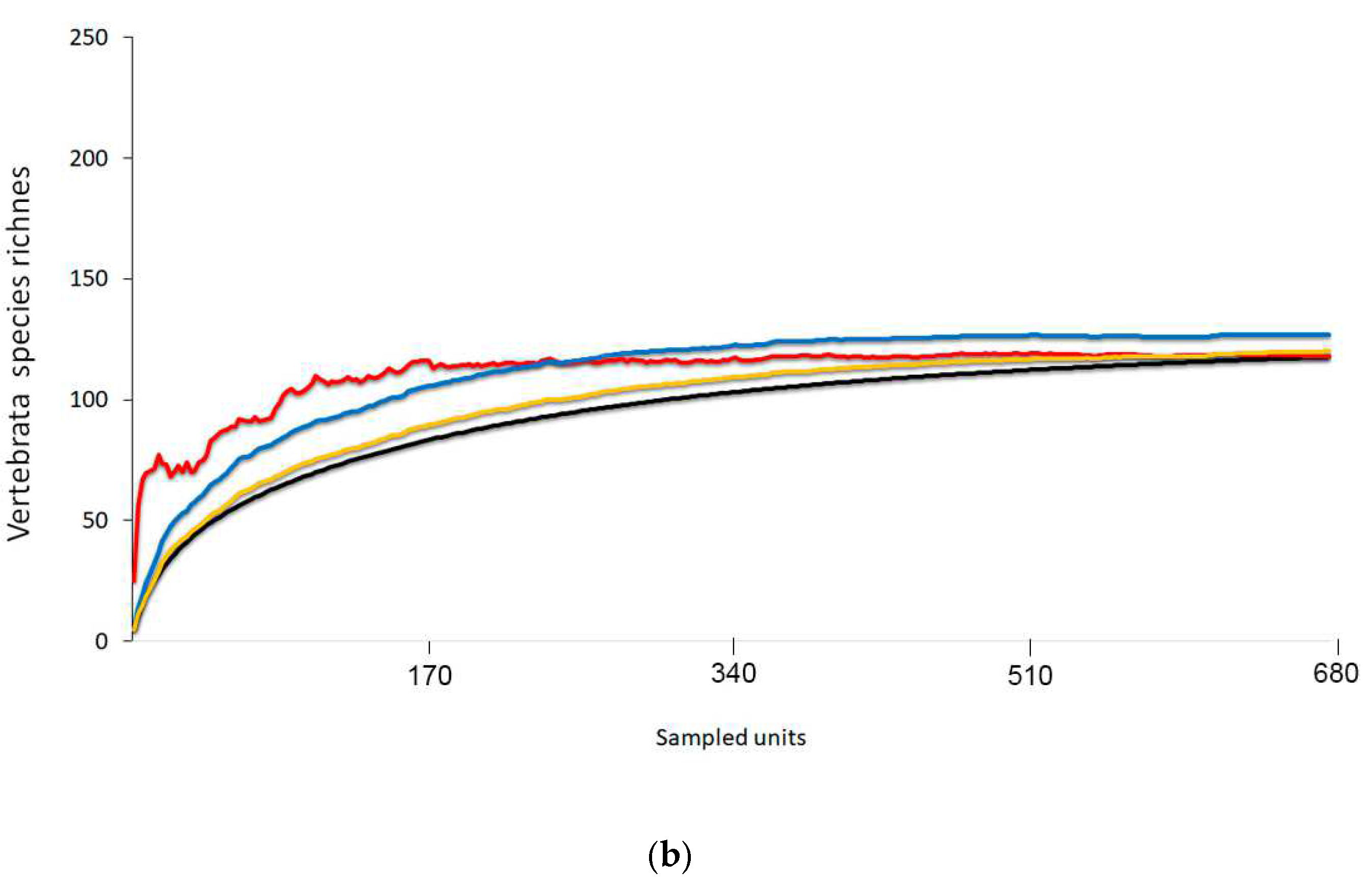

3.5. Richness Estimators

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vane-Wright, R.I.; Humpries, C.J.; Williams, P.H. (1991). What to protect? – Systematics and the agony of choice. Biological Conservation 1991, 55, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meffe, G.K.; Carrol, C.R. Principles of conservation Biology, Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, 1994.

- Perry, E.; Velázquez-Oliman, G.; Marín, L. The hydrogeochemistry of the karst aquifer system of the northerns Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. International Geology Review 2002, 44, 191–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yañez-Mendoza, G.; Zarza-González, E.; Mejía-Ortíz, L.M. Sistemas Anquihalinos. In Biodiversidad Acuática de la Isla de Cozumel Mejía-Ortíz, L.M. Ed; Plaza y Valdés, México, 2008, pp. 418.

- Álvarez, F.; Iliffe, T. Fauna anquihalina de la península de Yucatán. In Crustáceos de México, Estado actual de su conocimiento; Álvarez, F., Rodríguez Almaraz, G., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, programa de Mejoramiento del Profesorado (PROMEP), Secretaría de Educación Pública: Nuevo León, México, 2008; pp. 379–418. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, F.; Iliffe, T.; Benítez, S.; Brankovits, D.; Villalobos, J.L. New records of anchialine fauna from the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Check List 2015, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumba-Segura, L.; Hernández-Betancourt, S.; Sélem-Salas, C.; Barrientos-Medina, R. Colección Ictiológica. Bioagrociencias 2015, 8, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Llorente-Bousquets, J.; García Aldrete, A.; González Soriano, E. (Eds.) Biodiversidad, taxonomía y biogeografía de artrópodos de México: hacia una síntesis de su conocimiento Vol. II: Facultad de Ciencias, Museo de Zoología: México D.F., México, 1996; pp. 674.

- Llorente-Bousquets, J.; Morrone, J.J. (Eds.) Biodiversidad, taxonomía y biogeografía de artrópodos de México: hacia una síntesis de su conocimiento Vol. III: Facultad de Ciencias, Museo de Zoología: México D.F., México, 2002; pp. 690.

- Suárez-Morales, E.; Elías-Gutiérrez, M. Cladoceros (Crustacea: Branchiopoda) de la reserva de la biosfera de Sian Ka’an, Quintana Roo y zonas adyacentes. In Diversidad biológica en la reserva de la biosfera de Sian Ka’an Quintana Roo, Mexico; Navarro, D., Suárez-Morales, E., Eds.; Centro de Investigaciones de Quintana Roo (CIQRO): Chetumal Quintana Roo, Mexico, 1992: Volume II, pp. 145–162.

- Schmitter-Soto, J.J. A systematic revision of the genus Archocentrus (Perciformes: Cichlidae), with the description of two new genera and six new species. Zootaxa 2007, 1603, 1–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes-Martínez, A.; Durán Ramírez, C.A.; Elías-Gutiérrez, M.; García-Morales, A.E.; Gutiérrez-Aguirre, M.A.; Jaime, S.; Macek, M.; Maeda-Martínez, A.; Martínez-Jerónimo, F.; Mayén-Estrada, R.; Medina-Durán, J.H.; Montes-Ortíz, L.; Olvera-Bautista, J.F.Y. Romero-Niembro, V.M.; Suárez-Morales, E. Freswater diversity of zooplankton from Mexico: historical review of some of the main groups. Water 2023, 15, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margules, C.R.; Sarkar, S. Systematic conservation planning; Cambridge University Press, Union Kingdom, 2009; p. 278.

- Abud Hoyos, M.M.; Germán Naranjo, L.; Guerrero, J.; Guevara, O.; Suárez, C.F.; Prüssmann, J. Conservación de la biodiversidad en un contexto de clima cambiante: experiencias de WWF en los últimos 10 años. Biodiversidad en la práctica 2019, 4, 111–140. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Gómez, M.; Liedl, R.; Stefan, C.A. New GIS-Based model for karst dolines mapping using LiDAR: application of multidepth threshold approach in the Yucatan karst, Mexico. Remote Sens. 2019, II, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.B. Copepods from the cenotes and caves of the Yucatan Peninsula, with notes on Cladocerans. In The Cenotes of Yucatan A zoological and Hydrographic survey; Pearse, A.S., Creaser, E.P., Hall, F.G., Eds.; Carnegie Institution of Washington: Washington, DC, USA, 1936; pp. 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Studies on the caves and cave fauna of the Yucatan Peninsula. Association for Mexican Cave Studies. 1977, 6: 296pp. Reddel, J.R. (Ed.).

- Castro-Aguirre, J.L. Catálogo sistemático de los peces marinos que penetran a las aguas continentales de México, con aspectos zoogeográficos y ecológicos. Depto. Pesca México, Ser. Cient. 1978, 19, xi–298. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, H. III. Additional notes on cave shrimps (Crustacea: Atyidae and Palaemonidae) from the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Proc. Biol. Soc. Was. 1979, 92, 618–633. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, J.W. Continental and coastal free-living copepoda (Crustacea) of Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean region. In Diversidad biológica en la reserva de la biosfera de Sian Ka’an Quintana Roo, Mexico; Navarro, D., Robinson, J.G., Eds.; Centro de Investigaciones de Quintana Roo (CIQRO): Chetumal Quintana Roo, Mexico, 1990: Volume I, pp. 145–162.

- Suárez-Morales, E.; Elías-Gutiérrez, M. ladoceros (Crustacea: Branchiopoda) de la reserva de la biosfera de Sian Ka’an, Quintana Roo y zonas adyacentes. In Diversidad biológica en la reserva de la biosfera de Sian Ka’an Quintana Roo, Mexico; Navarro, D., Suárez-Morales, E., Eds.; Centro de Investigaciones de Quintana Roo (CIQRO): Chetumal Quintana Roo, Mexico, 1992: Volume II, pp. 145–162.

- Iliffe, T.M. An annotated list of the troglobitic anchialine and freshwater fauna of Quintana Roo. In Diversidad biológica en la reserva de la biosfera de Sian Ka’an Quintana Roo, Mexico; Navarro, D., Suárez-Morales, E., Eds.; Centro de Investigaciones de Quintana Roo (CIQRO): Chetumal Quintana Roo, Mexico, 1992: Volume II, pp. 145–162.

- Suárez-Morales, E.; Reid, J.W.; Iliffe, T.; Fiers, F. Catálogo de los copépodos (Crustacea) Continentales de la Península de Yucatán, Mexico. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO), El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR): Chetumal Quintana Roo, Mexico, 1996; 296 pp.

- Castro-Aguirre, J.L.; Espinosa, H.; y Schmitter-Soto, J.J. Ictiofauna estuarina, lagunar y vicaria de México: Limusa, México, 1999.

- Rocha, A.; Peralta, L.; Alcocer, J. Anfípodos e isópodos de aguas continentales de México. In Crustáceos de México, Estado actual de su conocimiento; Álvarez, F., Rodríguez Almaraz, G., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, programa de Mejoramiento del Profesorado (PROMEP), Secretaría de Educación Pública: Nuevo León, México, 2008; pp. 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- Elías-Gutiérrez, M.; Suárez-Morales, E.; Gutiérrez-Aguirre, M.; Silva-Briano, M.; Granados-Ramírez, J.G.; Garfias-Espejo, T. Cladocera y Copepoda de las aguas continentales de México. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y uso de la biodiversidad, El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales: Ciudad de México, México, 2008; p. 322. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, R.R. Peces dulceacuícolas de México. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, Sociedad Ictiológica Mexicana, A.C., El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Desert fishes Council: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2009; pp. 559.

- Brandorff, G.-O. Distribution of some Calanoida (Crustacea: Copepoda) from the Yucatan Peninsula, Belize and Guatemala. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2012, 60, 187–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohuo, S.; Macario-González, L.; Pérez, L.; Schwalb, A. Overview of Neotropical–Caribbean freshwater ostracode fauna (Crustacea, Ostracoda): identifying areas of endemism and assessing biogeographical affinities. Hydrobiologia 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, G.; Díaz-Pardo, E.; Martínez-Estévez, L.; Espinosa-Pérez, H. Peces dulceacuícolas de México en peligro de extinción; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Macario-González, L.; Cohuo, S.; Angyal, D.; Pérez, L.; Mascaró, M. Subterranean waters of Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico reveal epigean species dominance and intraspecific variability in freshwater ostracodes (Crustacea: Ostracoda). Diversity 2021, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botosaneanu, L.; Iliffe, T.M. Stygobitic isopod crustaceans, already described por new, from Bermuda, Bahamas, and Mexico. Bull. Inst. Roy. Sci. Nat. Bel. 2002, 72, 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, H.; Silva-Briano, M.; Subhash Babu, K.K. A re-evaluation of the Macrothrix rosea-triserialis group, with the description of two new species (Crustacea Anomopoda: Macrothricidae). Hydrobiologia 2002, 467, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinev, A.; Kotov, A.; Van Damme, K. Morphology of a Neotropical cladoceran Alona dentifera (Sars, 1901), and its position within the Chydoridae Stebbing, 1902 (Branchiopoda: Anomopoda). Arth. Sel. 2004, 13, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, N.L. New species and a new genus of Cirolanidae (Isopoda: Cymothoida: Crustacea) from groundwater in calcretes in the Pilbarra, northern Western Australia. Zootaxa 2008, 1823, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitter-Soto, J.J. A revision of Astyanax (Characiformes: Characidae) in Central and North America, with the description nine new species. J. Nat. Hist. 2017, 51, 1331–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos-Villalobos, J.; Schmitter-Soto, J.J.; Espinoza de los Montes, A.J. Several subspecies or phenotypic plasticity? A Geometric Morphometric and Molecular analysis of variability of the mayan cichlid Mayaheros urophthalmus in the Yucatan. Copeia 2018, 106, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.W.; Davis, G.E. An updated classification of the recent Crustacea; Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Science Series: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2001; p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, J.S.; Crossman, E.J.; Espinosa-Pérez, H.; Findley, L.T.; Gilbert, C.R.; Lea, N.R.; Williams, J.D. Common and Scientific names of fishes from the United States, Canada and Mexico. American Fisheries Society: Bethesda, United States of America 2004, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, B.A.; Morand, S. Comparative performance of species richness estimation methods. Parasitology. 1998, 116, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gondwe, B.R.N.; Lerer, S.; Stinen, S.; Marín, L.; Rebolledo-Vieyra, M.; Merediz-Alonso, G.; Bauer-Gottwein, P. Hydrogeology of the south-eastern Yucatan Peninsula: New insights from water level measurements, geochemistry, geophysics and remote sensing. J. Hydrol. 2010, 389, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gómez, M.; Liedl, R.; Stefan, C.A. New GIS-Based model for karst dolines Mapping Using LiDAR; Application of Multidepth Threshold approach in the Yucatan Karst, Mexico. Remote Sens 2019, 11, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrone, J.J. Regionalización biogeográfica y evolución biótica de México: encrucijada de la biodiversidad del Nuevo mundo. Rev. Mex. Bio. 2019, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitter-Soto, J.J.; Comín, F.A.; Escobar-Briones, E.; Herrera-Silveira, J.; Alcocer, J.; Suárez-Morales, E.; Elías-Gutiérrez, M.; Díaz-Arce, V.; Marín, L.E.; Steinich, B. Hydrogeochemical and biological characteristics of cenotes in the Yucatán Peninsula (SE Mexico). Hydrobiol. 2002, 467, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotov, A.; Gololova, M. Traditional taxonomy Quo vadis? Int. Zool. 2016, 11, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, F.; Durán, B.; Meacham, S. Anchialine fauna of the Yucatan Peninsula: diversity and conservation challenges. In Mexican Fauna in the Antropocene; Jones, R.W., Ed.; Springer Nature: Switzerland, 2014; pp. 287–301. [Google Scholar]

- Raven, P.H. Tropical floristics tomorrow. Taxon 1988, 37, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinev, A.Y. Re-evaluation of the genus Biapertura Smirnov, 1971 (Cladocera: Anomopoda: Chydoridae). Zootaxa 2020, 4885, 301–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, N.L.; Olesen, J. Cirolanid isopods from the Andaman Sea off Phuket, Thailand, with description of two new species. P. Mar. Biol. Center 2002, 23, 109–131. [Google Scholar]

| Families | Species | |

|---|---|---|

| Phylum: Arthropoda | ||

| Subphylum: Crustacea | ||

| Class: Branchiopoda | ||

| Order: Diplostraca | 7 | 58 |

| Class: Remipedia | ||

| Order: Nectiopoda | 1 | 3 |

| Class: Maxillopoda | ||

| Subclass: Copepoda | ||

| Infraclass: Neocopepoda | ||

| Superorder: Gymnoplea | ||

| Order: Calanoida | 7 | 19 |

| Superorder: Podoplea | ||

| Order: Misophrioida | 1 | 2 |

| Order: Cyclopoida | 2 | 42 |

| Order: Harpacticoida | 4 | 9 |

| Class Ostracoda | ||

| Order Podocopida | 5 | 34 |

| Subclass: Myodocopa | ||

| Order: Halocyprida | 2 | 2 |

| Class Malacostraca | ||

| Subclass: Eumalacostraca | ||

| Superorder: Peracarida | ||

| Order: Thermosbaenacea | 1 | 1 |

| Order: Mysida | 2 | 5 |

| Order: Amphipoda | 6 | 9 |

| Order: Isopoda | 1 | 9 |

| Superorder: Eucarida | ||

| Order: Decapoda | 9 | 20 |

| Phylum: Chordata | ||

| Subphylum: Vertebrata | ||

| Class: Actinopterygii | ||

| Order: Anguiliformes | 1 | 1 |

| Order: Atheriniformes | 3 | 11 |

| Order: Batrachoidiformes | 1 | 2 |

| Order: Beloniformes | 2 | 4 |

| Order: Characiformes | 2 | 7 |

| Order Cichliformes | 1 | 7 |

| Order: Clupeiformes | 3 | 6 |

| Order: Cyprinodontiformes | 4 | 24 |

| Order: Elopiformes | 1 | 1 |

| Order: Gadiformes | 1 | 1 |

| Order: Perciformes | 7 | 39 |

| Order: Synbrachiformes | 1 | 3 |

| Order: Siluriformes | 3 | 6 |

| Class: Chondrichthyes | ||

| Order: Myliobatiformes | 1 | 1 |

| Family | Species |

|---|---|

| Epacteriscidae | ++ Balinella yucatanensis |

| Ridgewayiidae | Exumella tsonot |

| Barbouriidae | Barbouria yanesi |

| Xibalbanidae | Xibalbanus tulumensis |

| Hyppolytidae | Calliasmata nohochi |

| Diaptomidae | Mastigodiaptomus siankanaensis, M. reidae, M. ha, M. maya |

| Stephidae | Stephos fernandoi |

| Speleophriidae | + Mexicophria cenoticola, Speleophria germanyanezi |

| Cyclopidae | Acanthocyclops rebecae, A. smithae, ++ Halicyclops cenoticola, H. caneki, H. tetracanthus, H. venezualensis, + Prehendocyclops monchenkoi, P. boxshalli, P. abbreviatus, Mesocyclops yutsil, M. chaci, Diacyclops chakan, D. puuc |

| Candonidae | Cypria petenensis, Cypridopsis niagranensis, Keysercypria xanabanica |

| Darwinulidae | Alicenula yucatanensis |

| Thaumatocyprididae | Humphreysella mexicana |

| Cyprididae | Cypretta campechensis, C. maya, Cypria petenensis, Neocypridopsis yucatanensis, Strandesia intrépida |

| Ampithodea | Cymadusa herrerae |

| Hadziidae | Bahadzia bozanici, Bahadzia setodactylus |

| Cirolanidae | + Creaseriella anops, Metacirolana mayana, Cirolana (Anopsilana) adriani, C. (A.) yucatana, C. yunca, C. bowmani, C. belizana, + Yucatalana robustispina |

| Palemonidae | + Creaseria morleyi |

| Hadziidae | +Mayaweckelia cenoticola, M. troglomorpha, M. yucatanensis, + Tuluweckelia cernua |

| Tulumellidae* | + Tulumella unidens |

| Anchialocarididae* | + Anchialocaris paulini |

| Procarididae | Procaris mexicana |

| Alpheide | + Yagerocaris cozumel, Triacanthoneus akumalensis |

| Spelephriidae | + Mexicophria cenoticola |

| Mysidae | Antromysis cenotensis |

| Amphipoda | Hyalella maya, H. cenotensis |

| Agostocarididae | Agostocaris bozanici, A. zabaletai |

| Stygiomysidae | Stygiomysis cokei |

| Atyidae | Typhlatya mitchelli, T. pearsei |

| Cyprinodontidae | Floridichthys polyommus, Cyprinodon artifrons, C. esconditus, C. labiosus, C. maya, C. simus, C. savium, Garmanella pulchra |

| Synbranchidae | Ophisternon infernale |

| Cichlidae | Thorichthys meeki |

| Poeciliidae | Poecilia velífera |

| Bythitidae | Typhlasina pearsei |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).