1. Introduction

Provisional restorations are frequently used in fixed partial dentures (FPDs) treatment. Before placing the permanent dental prosthesis, they ensure the stability of the occlusal relationships and assess the treatment’s efficacy in terms of aesthetic, functional, and therapeutic advantages [

1]. Recent advancements in CAD/CAM technology have enhanced the fabrication of provisional restorations via indirect methods. Compared to the traditional approach, they have reduced the number of workflow steps and the required working time. CAD/CAM blocks are industrially polymerized under high pressure and temperature, resulting in a higher degree of conversion and polymerization reaction than conventional polymerized resins [

2,

3,

4].

Over the past few years, the role of provisional restorations has undergone a significant transformation. These restorations are now considered provisional restorations with specific functions and purposes rather than temporary restorations. Provisional restorations are a crucial issue when comprehensive occlusal reconstruction is required, especially when subjected to prolonged functional stresses. Furthermore, they may provide new therapeutic options in maxillofacial rehabilitation, implant-assisted prostheses, and periodontal therapy [

1,

2].

When choosing long-term provisional restorative materials, clinicians should consider the type of materials, their mechanical and bonding properties, and the impact of oral environmental conditions when using provisional CAD/CAM materials for extended periods y [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Although these restorations demonstrate significant mechanical potential; resin veneering is essential for aesthetic enhancement. Veneering of CAD/CAM provisional restorations is a necessary step to improve the aesthetic outcomes of restorations, as indicated by the manufacturers. Furthermore, most polymeric CAD/CAM blocks are available in a single-color shade. For long-term applications of these polymeric materials, the use of veneering resins is crucial to enhance aesthetic results [

9,

10]. Additionally, these materials are frequently subjected to oral conditions, including rapid temperature fluctuations. Thermal stresses can cause deterioration of the interfacial bonding when hot or cold beverages are consumed in the mouth [

9,11,

12,

13].

Bonding CAD/CAM provisional restorations to resin veneering is a difficult challenge because the resin is resistant to surface modification due to its high degree of polymerization and diverse microstructures. The establishment of a suitable bond between the veneering resin and the CAD/CAM provisional materials is essential for the success of these restorations [

14,

15,

16]. Additionally, it is crucial to have a comprehensive understanding of the bonding characteristics of these materials, especially when exposed to thermal aging. This study investigated the impact of different surface treatments and thermal aging on the bond strength between veneering resin and CAD/CAM provisional restorative materials. The null hypotheses examined were: (1) there was no significant difference in bond strength among the three CAD/CAM materials, (2) surface treatments, and (3) thermocycling did not impact the bond strength of these materials.

2. Materials and Methods

Table 1 shows the materials utilized in this study. CAD/CAM polymers used for long-term provisional restorations are utilized in this study including polyacrylate polymer (CAD-Temp; CAT), fiber-glass-reinforced polymer (Everest C-Temp; CT), and polyether ether ketone PEEK (BioHPP; PK). The sample size calculation was performed using G*Power software. The power analysis indicated that ten specimens per group were necessary to achieve a 0.95 power at a 5% significance level (effect size = 0.385, α = 0.05 for a two-tailed test).

2.1. Specimens’ Preparation and Grouping

Fifty disk-shaped specimens of each CAD/CAM material measuring (10 mm diameter x 3 mm height) were fabricated by sectioning the block using an ISOMET (Techcut4, Allied, USA). Then the specimens were ultrasonically cleaned using 90% isopropyl alcohol. To prepare the cut surfaces for resin veneer, wet silicon carbide polishing papers (Microcut™, Buehler, Lake Bluff, USA) of different grades (600, 800, and 1200 grit) were utilized. A uniform finish was achieved using polishing paste and a 1 μm polishing cloth disc (Grinder polisher Metaserve 250; BUEHLER, U.S.A). The specimens were embedded in acrylic resin blocks (Paladur, Heraeus-Kulzer, Hanau, Germany), with one surface left exposed for surface treatments.

Specimens were categorized into 5 groups (n=10/gp) based on the surface treatments and aging procedures outlined below.: C; no surface treatment. DB; The surfaces of the specimens were abraded with a diamond bur (medium grit) that was mounted in a high-speed handpiece operating at 45,000 rpm, with irrigation, for 8 seconds [

14]. DB+TC: DB group with 5000 cycles of thermocycling. SB; Aluminum oxide particles (50 μm, LEMAT NT4, Wassermann, Germany) were used to air-abrade the specimens’ surfaces for ten seconds, maintaining a distance of 10 mm and applying a 0.55 MPa pressure. This was followed by air drying the surfaces for 20 seconds [

17,

18]. SB+TC: SB group, along with 5000 cycles of thermocycling [

19].

2.2. Bonding Procedures and Aging Protocol

The bonding region was defined by attaching a 6 mm diameter double-sided tape with a circular hole to the specimens’ surfaces. The Primer (Visio. Link, Bredent GmbH & Co., Senden, Germany) was applied to the specimens’ surfaces according to the manufacturer’s instructions and cured for 20 seconds using an LED light (Elipar Freeligh 2, 3M ESPE, 1,226 mW/cm²). Incremental packing of resin veneering materials (Crealign paste, Bredent GmbH & Co., Senden, Germany) was applied onto the treated CAD/CAM surfaces utilizing a 6-mm diameter circular split Teflon mold, with each layer (2 mm) cured using LED light for 180 seconds according to manufacturer instructions to produce 10 mm height cylinder. In each group, half of the specimens (N=10) underwent 5000 cycles of thermocycling (SD Mechatronic GmbH, Feldkirchen Westerham, Germany) at temperatures ranging from 5 to 55 °C for 30 seconds.

2.3. Bond Strength (SBS) Testing

The SBS between the resin veneer and CAD/CAM provisional materials was conducted using a universal testing machine. The machine’s lower jaw firmly clamped the specimens, ensuring their alignment with the direction of the shear force. The specimen was subsequently subjected to a compressive load with a 0.5 mm/min crosshead speed until failure, while the load was recorded using a force gauge, with load being recorded by a force gauge [

4,

14]. For each specimen, the maximum load was divided by the surface area to obtain the SBS in MPa. The failure mode was classified as an adhesive failure occurring between the resin veneering and the provisional material surface, cohesive failure within either the resin veneering or the provisional material surface, or mixed failure, i.e., both adhesive and cohesive failure. A frequency analysis was performed for each failure mode utilizing an optical stereomicroscope at a magnification level of 40x.

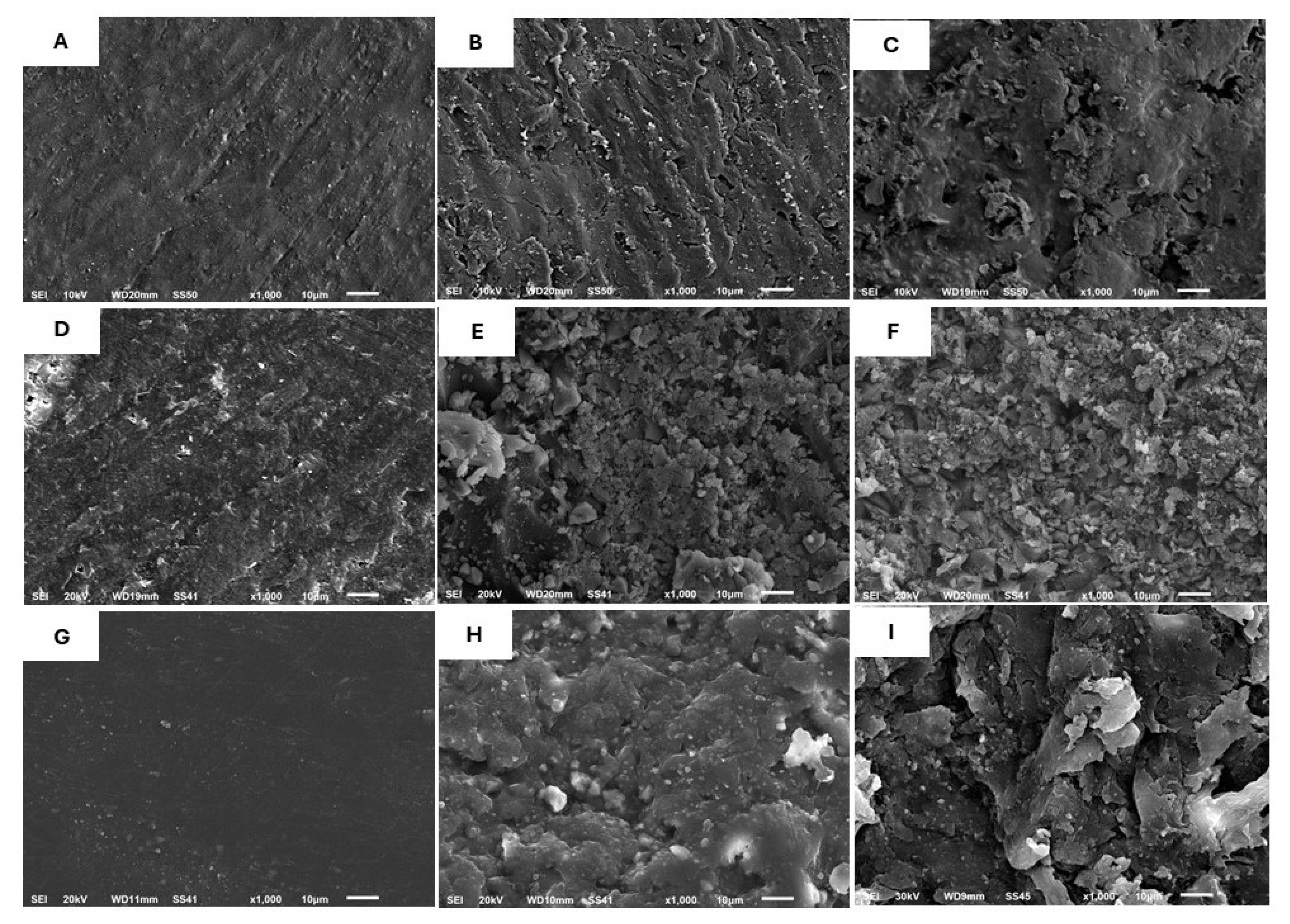

2.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

A scanning electron microscopy (SEM) instrument (Jeol-JSM-6510, Tokyo, Japan) was used to identify surface differences in the CAD/CAM provisional restorative materials following surface treatments. All specimens were coated using a gold sputter coater. SEM analysis was performed on the surface of one representative sample for each group at a magnification of 500 x [

20].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The Shapiro–Wilk test assessed the normality of the data distribution, while Levene’s test evaluated the homogeneity of variances. All SBS values conformed to normality and satisfied the assumption of homogeneity of variances.

A three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni’s post hoc test was performed at a 95% confidence level (α = 0.05) to evaluate the main effects of each material, surface treatment, and thermocycling, as well as their interaction effect on the shear bond strength (SBS).

3. Results

Table 2 presents the SBS values (MPa) for each group. The two-way analysis of variance showed significant differences in SBS values among different types of materials (F=813.74, p < .001), surface treatments (F=602.203, p < .001), and the aging conditions (F=244.167, p < .001) [

Table 3]. The highest SBS values were observed for the C-Temp in the SB group (20.38 ± 1.04 MPa), and the lowest values were noted for the CAD-Temp in the C group (4.60 ±0.54). DB and SB groups recorded the highest significance (p < .001) SBS values in C-Temp (16.92 ± 0.70, 20.38 ± 1.04 MPa, respectively) compared to other surface treatment groups in different materials.

No significant differences were observed in SBS values between CAD-Temp and PEEK in C, DB, and SB groups (p > .05). On the other hand, PEEK recorded significantly higher SBS values in DB+TC and SB+TC groups (9.26 ± 1.07, 12.92 ± 0.97 MPa, respectively) compared to CAD-Temp in DB+TC, and SB+TC groups (6.04 ± 0.76, 8.82 ± 0.86 MPa, respectively). Although the thermocycling significantly reduced SBS value for C-Temp in DB+TC and SB+TC groups (11.18 ± 0.92, 15.56 ± 0.87 MPa, respectively), it recorded the highest SBS value compared to other materials in the same groups (CAD-Temp and PEEK) (6.04 ± 0.76, 8.82 ± 0.86 MPa, respectively), and (9.26 ± 1.07, 12.92 ± 0.97 MPa) respectively.

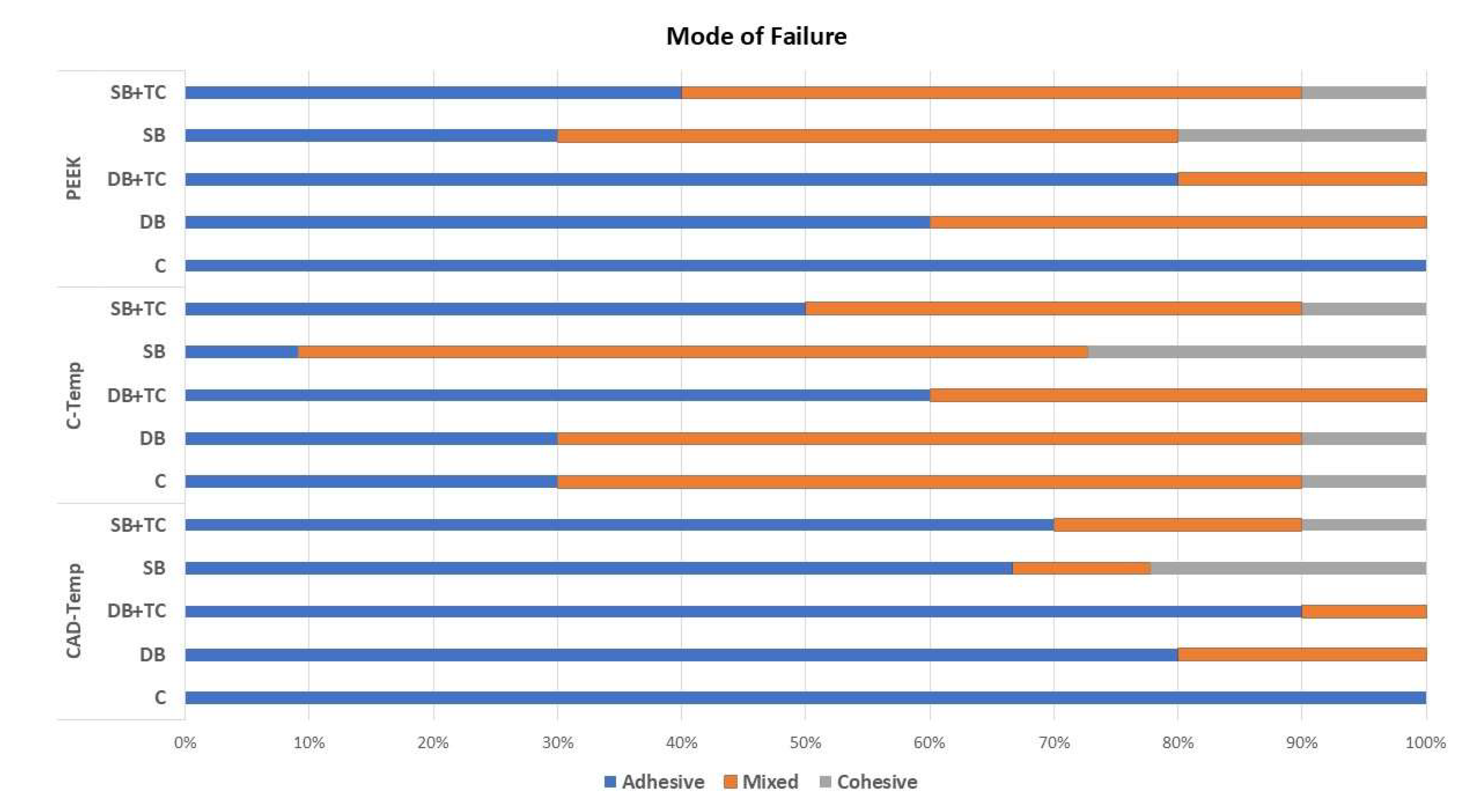

Adhesive failure was highly prevalent in CAD-TEMP in all groups. On the other hand, mixed failures were the prevalent type for C-Temp in all groups. Regarding PEEK material, adhesive failure was the prevalent type observed in group C. However, mixed failure was the most common type in the SB group. Following thermocycling, the most common failure types observed were mixed and cohesive in C-temp and PEEK, whereas adhesive failure was the most prevalent in CAD-Temp (

Figure 1).

The SEM analysis indicated differences in the surface microstructures of the treated CAD-Temp, C-Temp, and PEEK (Figure 2). CAD-Temp and PEEK materials in the C group showed smooth surfaces devoid of surface texture, whereas C-Temp homogenous, smooth surfaces with irregular surface texture (figs. 2 A, D, and G). Roughening using a bur consistently showed an erosive appearance with undercuts(figs. 2 B, E, and H). The air-born abraded group exhibited clearly defined micro-sized irregularities (figs. 2 C, F, and I). The impact of mechanical roughening methods, such as diamond bur and sandblasting, exhibited greater homogeneity, uniformity, and orientation with C-Temp.

4. Discussion

Provisional restorations serve as a temporary treatment to maintain occlusion, pulp health, and aesthetic appearance while permanent restorations are being fabricated. Provisional restorations can be fabricated manually or by CAD/CAM technology. Manual fabrication is associated with several issues, such as undesirable odor, significant polymerization shrinkage, reduced durability, porosity, and increased surface roughness [

21,

22].

CAD/CAM PMMA blocks are industrially polymerized under optimal manufacturing conditions. These conditions provide provisional restorations that exhibit superior mechanical characteristics compared to those fabricated manually. Their excellent mechanical properties serve as an effective solution for durable provisional restorations. Furthermore, the enhanced fit of milled CAD/CAM restorations is expected to reduce the chances of bacterial contaminations and protect the pulp from harmful temperature fluctuations [

5,

23,

24]. These restorations are placed in the oral cavity for extended periods in some clinical scenarios, such as adjusting the vertical dimension, modifying occlusal plane abnormalities, and crown lengthening procedures [

13,

19].

Additionally, the polymeric CAD/CAM materials utilized in this study have been recommended by manufacturers as suitable framework materials for implant-supported fixed prostheses [

24,

25,

26,

27]. For long-term application, these materials may be veneered post-milling through a layering technique to improve aesthetic outcomes. The bond strength of veneering resin to CA/CAM provisional materials must be sufficiently strong to enhance their durability in oral environments during treatment procedures. This investigation evaluates the influence of surface treatments and aging on the bond strength between veneering resin composites and long-term CAD/CAM provisional restorative materials.

Multiple surface treatment techniques can be utilized to improve the bond strength of interim restorative materials, such as air abrasion, laser treatment, and acid etching [

28,

29]. This study demonstrates that adhesion can be achieved through the application of diamond bur or airborne particle abrasion techniques. Reports indicate that these methods represent the most effective means to enhance microroughness and augment surface area for optimal bonding [

30,

31]. This study conducted shear bond strength tests, which serve as a reliable method for evaluating bond strengths of a large surface area, typically between 3 to 6 mm in diameter [

4,

19,

32].

The three-way ANOVA indicated a significant impact of the three independent variables (material type, surface treatment methods, and aging) on the SBS. Therefore, the three null hypotheses are rejected. The study’s results indicated that the untreated surfaces of CAD-Temp and PEEK displayed the lowest SBS values. This is likely due to these materials being industrially polymerized, resulting in a higher polymerization and an insufficient presence of free radicals for effective adhesion to the resin veneering materials [

14,

33]. On the other hand, the untreated surfaces of C-Temp showed the highest SBS in the control group. The irregular surface topography of C-Temp (

Figure 3D) may facilitate adhesive resin penetration, thereby enhancing the interlock with resin veneering materials [

14,

21].

This study demonstrates that mechanical surface treatments utilizing diamond bur and air particle abrasion lead to a significant enhancement in shear bond strength (SBS), especially in C-Temp and PEEK materials. The shear bond strength (SBS) can be enhanced through mechanical surface treatments, which increase the substrate’s surface energy and produce surface irregularities that aid in micromechanical retention. Additionally, C-Temp exhibits a higher glass fiber content and is classified as a high-performance continuous molecular plastic polymer chain, which is appropriate for adhesive resin penetration [

4,

14]. The findings align with Weigand et al. [

14], who proposed that the increased SBS with C-Temp may result from the adhesive’s capacity to infiltrate surface irregularities associated with glass fiber, thereby enhancing adhesion. The SEM analysis in this study demonstrated that mechanical roughening modified the surface morphology of PEEK, enhancing adhesive resin penetration, which improved micromechanical interlock and subsequently, increased bond strength.

This study involved subjecting the specimens to 5000 thermal cycles to imitate clinical conditions and evaluate long-term bonding durability, representing six months of clinical use [

34]. The current investigation revealed that thermocycling significantly reduced the SBS of CAD-Temp. The high polymeric content (83–86 wt% PMMA) may account for this phenomenon, as it is prone to water infiltration between the gaps of the polymer chains, resulting in their separation. This process leads to water absorption, which ultimately softens the resin matrix and adversely affects SBS [

4,

13,

19]. Thermocycling led to a reduction in the shear bond strength (SBS) of C-Temp. The presence of moisture promotes the corrosion of the glass fiber surface, as water infiltrates the polymer matrix, thereby compromising mechanical properties and bond strength [

35]. In contrast, thermocycling did not significantly affect the SBS of PEEK material, likely due to its low water sorption. PEEK demonstrates a water sorption value of (≤ 6.5 μg/mm³), CAD-Temp presents a value of (≤ 40 μg/mm³), and Everest C-Temp has a value of (9.6 μg/mm³) [

19,

22]. A previous investigation indicated that 5000 thermocycling cycles have a minimal impact on the adhesion characteristics of PEEK restorative materials [

36]. Libermann et al. [

15] investigated the impact of different ageing conditions on the water sorption characteristics of multiple CAD/CAM polymers. The findings indicated that the storage media type did not have a significant effect on PEEK’s water absorption capacity.

This study revealed a significant occurrence of adhesive failures at CAD-Temp, due to inadequate SBS. Furthermore, C-Temp and PEEK demonstrated a higher frequency of mixed failures, which can be ascribed to the inconsistent distribution of shear forces at the resin-restoration interface [

37,

38]. The results demonstrate a shift from adhesive failure to mixed failure as the bond strength increased. Conforming to the requirements of ISO 10,477 [

39], the minimal acceptable SBS value at the interface of resin-based materials with the substrate is 5 MPa. A clinically acceptable SBS value of 10 MPa was proposed by Beher et al. [

40]. All groups met the clinical criteria, except for the C and SB-T groups in CAD-Temp, the SB-T group in C-Temp, and the C group in PEEK.

This study has limitations, as it utilized only three types of provisional restorative materials and one type of veneering resin. Furthermore, other oral environmental factors, such as different pH levels and prolonged aging periods, need further investigation. SBS values obtained in this study serve as relative comparisons between the tested materials and do not fully represent the entire intraoral forces in the oral environment. Furthermore, shear bond strength values exhibit significant variability based on study design; therefore, caution is warranted when translating laboratory bond strength findings to clinical applications. From a material science perspective, the reason for the differences in bonding performance among these restorative materials could be related to differences in elastic modulus. Consequently, future research should consider the impact of the elastic modulus on the bonding capabilities of these materials.

5. Conclusions

Within the limitations of this study, C-Temp exhibited higher SBS values without surface treatment, whereas PEEK showed higher SBS values after diamond bur roughening and air particle abrasion. CAD-Temp recorded the lowest SBS values, which are below the clinically accepted value (10 MPa) in all groups except for the SB group. Thermocycling significantly reduced bond strength in all materials except for PK material in the air particle abrasion group.

Results of the current study suggest that the C-Temp and PEEK can be recommended as promising provisional materials due to their excellent bonding properties after thermal aging. Suitable surface treatments and the selection of a suitable provisional material could improve the adhesive properties for these materials to be used for long-term applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: T.A.S, A.R; Experimental work: K.F.A, A.F.A, E.M.R, M.A.S.A; Interpretation of data: T.A.S, A.R, N.R.A; writing original draft: A.A.A.E; prepared figures 1-3: A.A, Q.H, K.F.A; review and editing: T.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors thank Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for supporting this research via funding under project number (PSAU/2024/R/1445).

Institutional Review Board Statement

N/A.

Data Availability Statement

This article has all the data that was collected or analyzed during this study

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for supporting this research via funding under project number (PSAU/2024/R/1445).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Burns, D.R.; A Beck, D.; Nelson, S.K. Committee on Research in Fixed Prosthodontics of the Academy of Fixed Prosthodontics.. A review of selected dental literature on contemporary provisional fixed prosthodontic treatment: Report of the Committee on Research in Fixed Prosthodontics of the Academy of Fixed Prosthodontics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2003, 90, 474–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stawarczyk, B.; Ender, A.; Trottmann, A.; Özcan, M.; Fischer, J.; Hämmerle, C.H.F. Load-bearing capacity of CAD/CAM milled polymeric three-unit fixed dental prostheses: effect of aging regimens. Clin Oral Invest. 2012, 16, 1669–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalifa, O.M.; Badawi, M.F.; Soliman, T.A. Bonding durability and remineralizing efficiency of orthodontic adhesive containing titanium tetrafluoride: an invitro study. BMC Oral Heal. 2023, 23, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, T.A.; Ghorab, S.; Baeshen, H. Effect of surface treatments and flash-free adhesive on the shear bond strength of ceramic orthodontic brackets to CAD/CAM provisional materials. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 26, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayyan, M.M.; Aboushelib, M.; Sayed, N.M.; Ibrahim, A.; Jimbo, R. Comparison of interim restorations fabricated by CAD/CAM with those fabricated manually. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 114, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsyad, M.; Soliman, T.; Khalifa, A. Retention and Stability of Rigid Telescopic and Milled Bar Attachments for Implant-Supported Maxillary Overdentures: An In Vitro Study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2018, 33, e127–e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alp, G.; Murat, S.; Yilmaz, B. Comparison of Flexural Strength of Different CAD/CAM PMMA-Based Polymers. J. Prosthodont. 2018, 28, E491–E495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şişmanoğlu, S.; Gürcan, A.T.; Yıldırım-Bilmez, Z.; Turunç-Oğuzman, R.; Gümüştaş, B. Effect of surface treatments and universal adhesive application on the microshear bond strength of CAD/CAM materials. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2020, 12, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stawarczyk, B.; Trottmann, A.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Özcan, M. Adhesion of veneering resins to polymethylmethacrylate-based CAD/CAM polymers after various surface conditioning methods. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2012, 71, 1142–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keul C, Müller-Hahl M, Eichberger M, Liebermann A, Roos M, Edelhoff D, Stawarczyk B. Impact of different adhesives on work of adhesion between CAD/CAM polymers and resin composite cements J Dent. 2014 Sep;42(9):1105-14.

- Sismanoglu, S.; Yildirim-Bilmez, Z.; Erten-Taysi, A.; Ercal, P. Influence of different surface treatments and universal adhesives on the repair of CAD-CAM composite resins: An in vitro study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2020, 124, 238.e1–238.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, T.A.; Raffat, E.M.; Farahat, D.S. Evaluation of Mechanical Behavior of CAD/CAM Polymers for Long-term Interim Restoration Following Artificial Aging. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent. 2022, 31, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, A.; Stucki, L.; Hoffmann, R.; Attin, T.; Stawarczyk, B. Repairability of CAD/CAM high-density PMMA- and composite-based polymers. Clin. Oral Investig. 2015, 19, 2007–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebermann, A.; Wimmer, T.; Schmidlin, P.R.; Scherer, H.; Löffler, P.; Roos, M.; Stawarczyk, B. Physicomechanical characterization of polyetheretherketone and current esthetic dental CAD/CAM polymers after aging in different storage media. J Prosthet Dent. 2016, 115, 321–328e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barto, A.; Vandewalle, K.S.; Lien, W.; Whang, K. Repair of resin-veneered polyetheretherketone after veneer fracture. J Prosthet Dent. 2021, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglar, I.; Ates, S.M.; Dds, Z.Y.D. An In Vitro Evaluation of the Effect of Various Adhesives and Surface Treatments on Bond Strength of Resin Cement to Polyetheretherketone. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, e342–e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ates, S.M.; Caglar, I.; Duymus, Z.Y. The effect of different surface pretreatments on the bond strength of veneering resin to polyetheretherketone. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2018, 32, 2220–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, T.A.; Robaian, A.; Al-Gerny, Y.; Hussein, E.M.R. Influence of surface treatment on repair bond strength of CAD/CAM long-term provisional restorative materials: an in vitro study. BMC Oral Heal. 2023, 23, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Gerny, Y.; Ghorab, S.; Soliman, T. Bond strength and elemental analysis of oxidized dentin bonded to resin modified glass ionomer based restorative material. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2019, 11, e250–e256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strasding, M.; Marchand, L.; Merino, E.; Zarauz, C.; Pitta, J. Material and abutment selection for CAD/CAM implant-supported fixed dental prostheses in partially edentulous patients – A narrative review. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2024, 35, 984–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, G.-W.; Park, E.-J. Fracture Strength of Six-Unit Anterior Fixed Provisional Restorations Fabricated Using Various Dental CAD/CAM Systems. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2024, 37, S49–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Yao, J.; Du, Z.; Guo, J.; Lei, W. Comparative Evaluation of Mechanical Properties and Color Stability of Dental Resin Composites for Chairside Provisional Restorations. Polymers 2024, 16, 2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadek, H.M.A.; El-Banna, A. Biaxial flexural strength of different provisional restorative materials under chemo-mechanical aging: An in vitro study. J. Prosthodont. 2023, 33, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everest, C. Temp provisional restoration (2016) KaVo Elements for KaVo ARCTICA and KaVo Everest. The foundation for reliable long-term temporary applications: C-Temp. IOP Publishing Physics Web. http://dinamed.by/media/Instrukcii2014/ARCTICA_en_Material.pdf. Accessed. 29 August.

- PEEK, BIOHPP, (2013) Bredent UK. The new class of materials in prosthetics. https://www.bredent.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/BioHPP- 2013.pdf. Accessed 10 july 2021.

- CAD-Temp provisional restoration. https://www.vita-zahnfabrik.com/en/VITA-CAD-Temp-multiColor25330,27568.html.

- Zhou, L.; Qian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, H.; Gan, K.; Guo, J. The effect of different surface treatments on the bond strength of PEEK composite materials. 30. [CrossRef]

- Schmidlin, P.R.; Stawarczyk, B.; Wieland, M.; Attin, T.; Hämmerle, C.H.; Fischer, J. Effect of different surface pre-treatments and luting materials on shear bond strength to PEEK. Dent. Mater. 2010, 26, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chay, S.H.; Wong, S.L.; Mohamed, N.; Chia, A.; Yap, A.U.J. Effects of surface treatment and aging on the bond strength of orthodontic brackets to provisional materials. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2007, 132, 577.e7–577.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peumans, M.; Hikita, K.; De Munck, J.; Van Landuyt, K.; Poitevin, A.; Lambrechts, P.; Van Meerbeek, B. Effects of ceramic surface treatments on the bond strength of an adhesive luting agent to CAD–CAM ceramic. J. Dent. 2007, 35, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendeke, J.; Ozcan, M. Effect of physicochemical aging conditions on the composite-composite repair bond strength. . 2007, 9, 399–406. [Google Scholar]

- Stawarczyk, B.; Basler, T.; Ender, A.; Roos, M.; Özcan, M.; Hämmerle, C. Effect of surface conditioning with airborne-particle abrasion on the tensile strength of polymeric CAD/CAM crowns luted with self-adhesive and conventional resin cements. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2012, 107, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeponmaha, T.; Angwaravong, O.; Angwarawong, T. Comparison of fracture strength after thermo-mechanical aging between provisional crowns made with CAD/CAM and conventional method. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2020, 12, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.S.; Azam, M.T.; Khan, M.; Mian, S.A.; Rehman, I.U. An update on glass fiber dental restorative composites: A systematic review. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 47, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niem, T.; Youssef, N.; Wöstmann, B. Influence of accelerated ageing on the physical properties of CAD/CAM restorative materials. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 24, 2415–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezvergil, A.; Lassila, L.; Vallittu, P. Composite–composite repair bond strength: effect of different adhesion primers. J. Dent. 2003, 31, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astudillo-Rubio D, Delgado-Gaete A, Bellot-Arcís C, Montiel- Company JM, Pascual-Moscardó A, Almerich-Silla JM. Mechanical properties of provisional dental materials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0193162.

- ISO. (2020) ISO 10477 Dentistry-polymer-based crown and veneering materials. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization. Available at:https://www.iso.org/standard/80007.html.

- Behr, M.; Rosentritt, M.; Gröger, G.; Handel, G. Adhesive bond of veneering composites on various metal surfaces using silicoating, titanium-coating or functional monomers. J. Dent. 2003, 31, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).