Submitted:

06 January 2025

Posted:

08 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

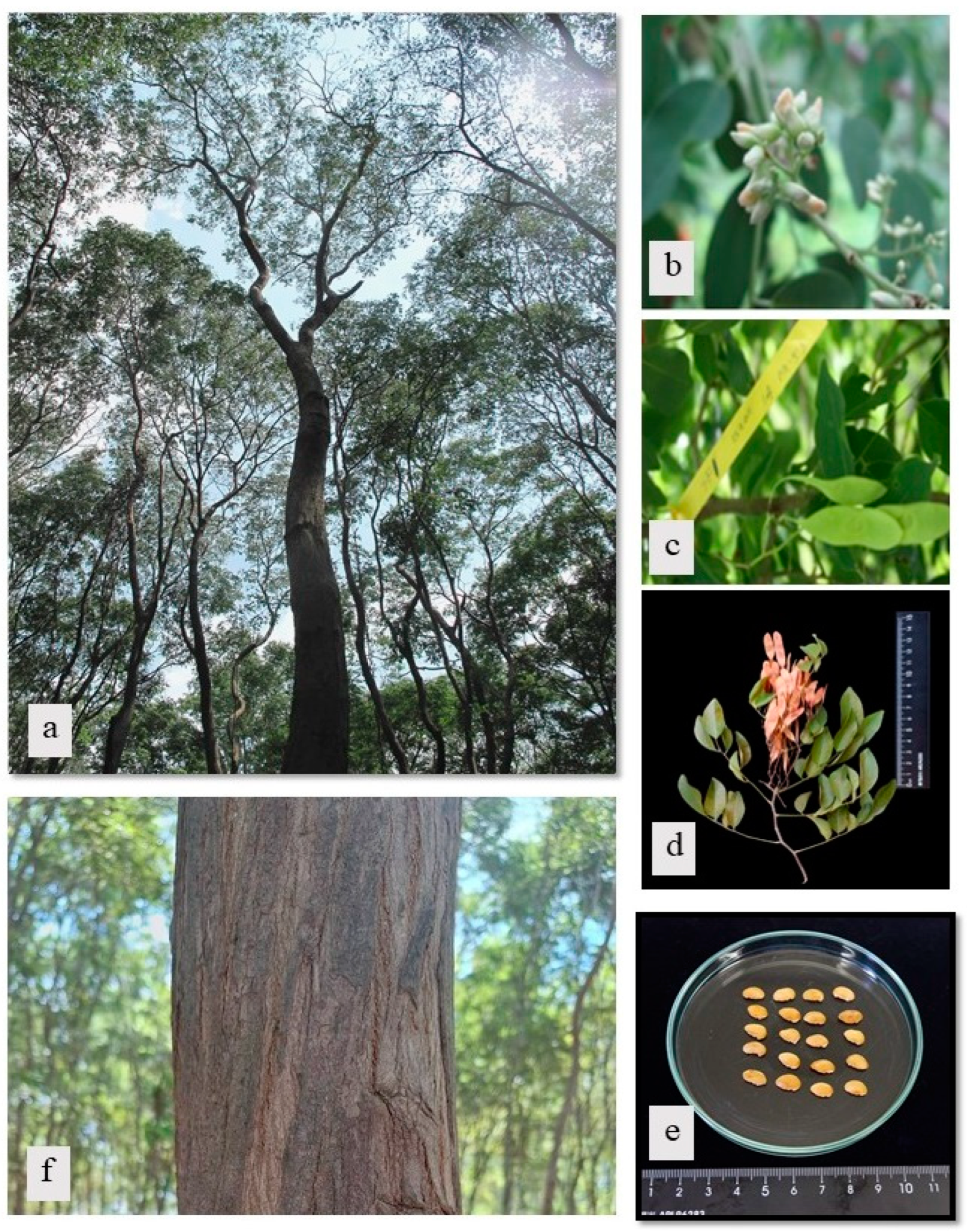

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

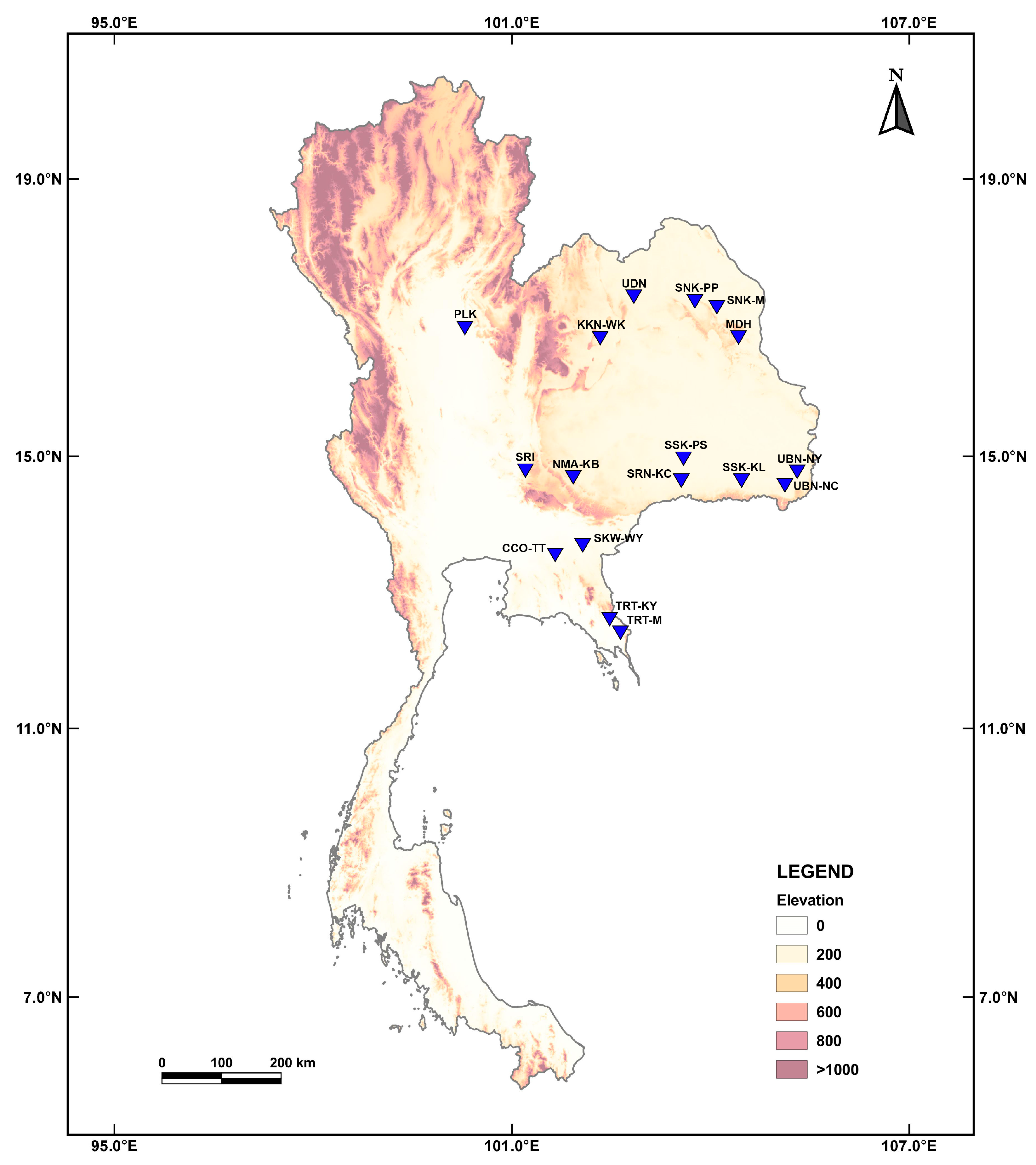

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Molecular Analysis

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Genetic Diversity of D. cochinchinensis

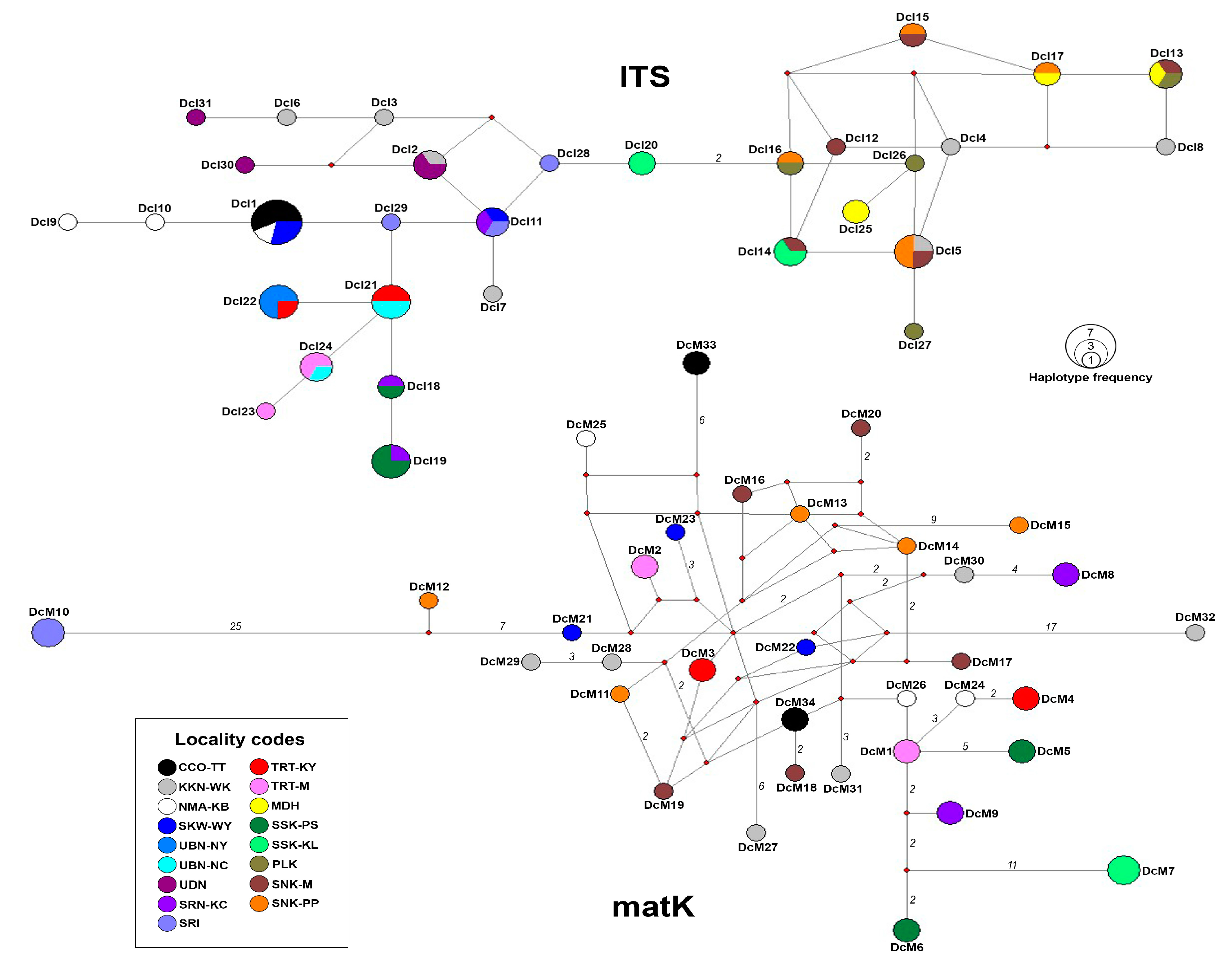

3.2. Haplotype Network

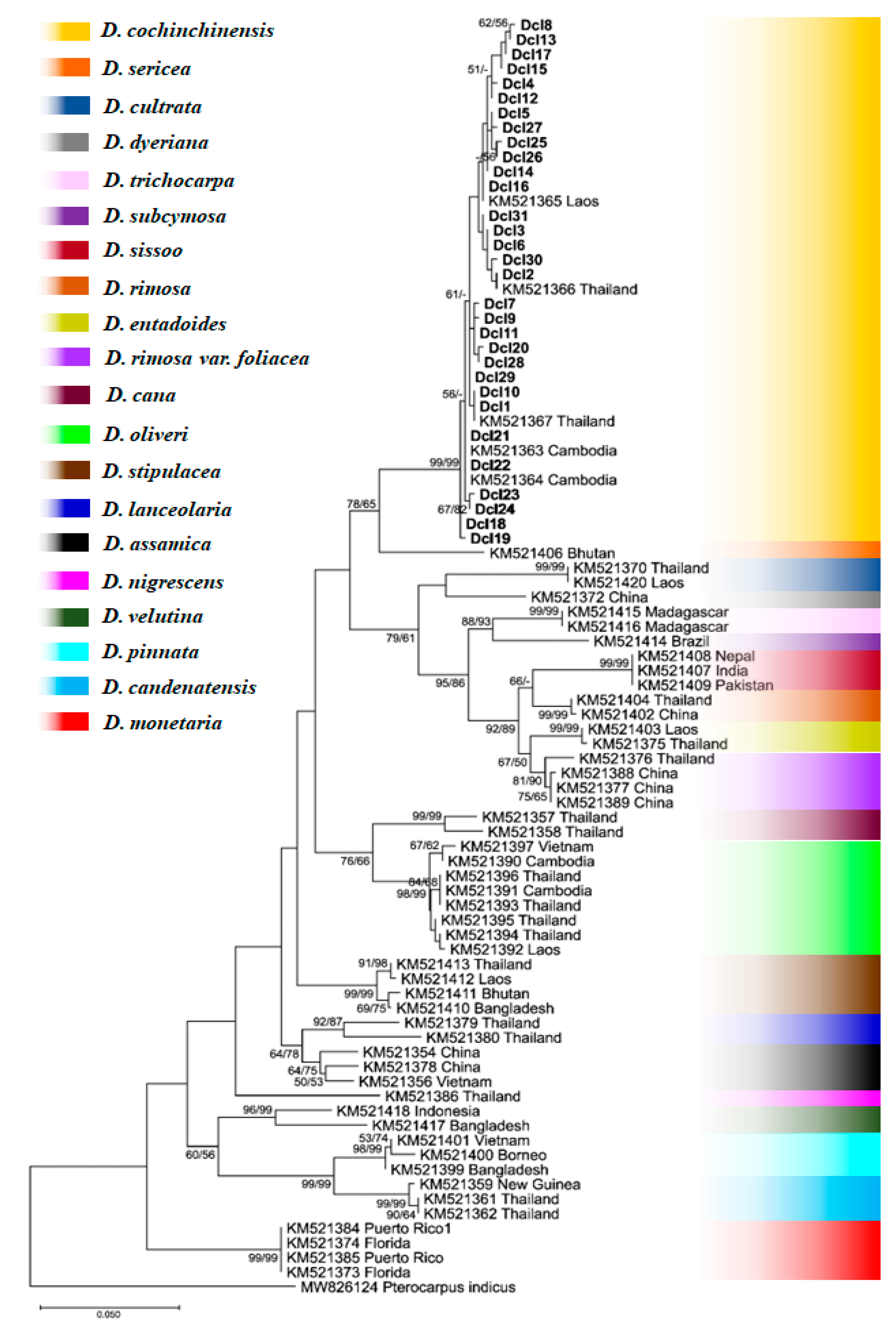

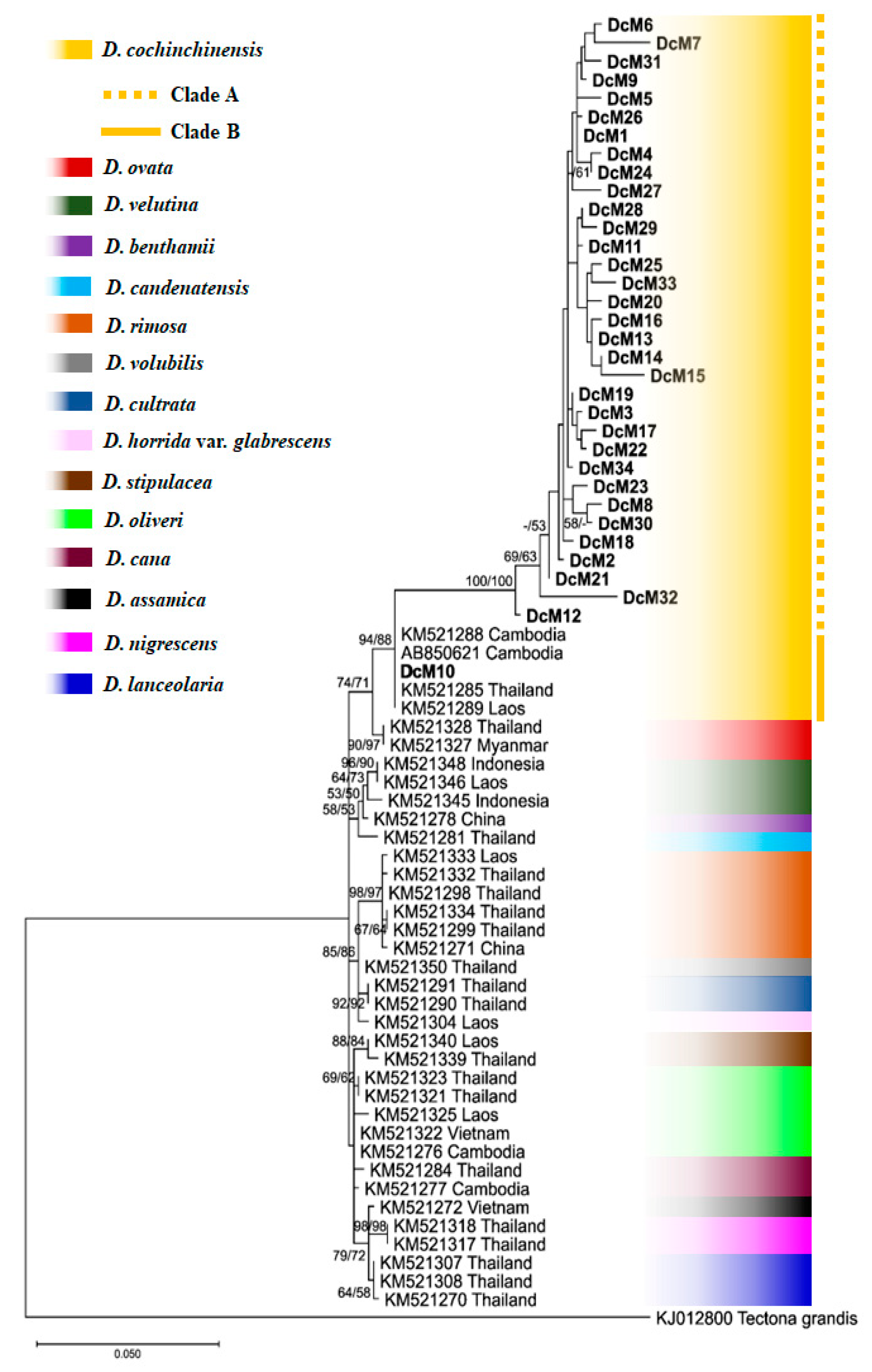

3.3. Phylogenetic Tree

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vatanparast, M.; Klitgård, B.B.; Adema, F.A.; Pennington, R.T.; Yahara, T.; Kajita, T. First molecular phylogeny of the pantropical genus Dalbergia: implications for infrageneric circumscription and biogeography. South Afr. J. Bot. 2013, 89, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyomdham, C. An accont of Dalbergia (Leguminosae-Papilionoideae) in Thailand. Thai For. Bull (Bot.). 2002, 30, 124–166. [Google Scholar]

- Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation. Report summarizing statistics of illegal cases related to forestry. 2018. Available online: https://portal.dnp.go.th/Content?contentId=2134 (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- CITES. Appendices I, II and III: valid from 4 October 2017. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. 2018.

- National Council for Peace and Order. Announcement of the National Council for Peace and Order No. 106/2014 regarding amendments to the forest law. 2014.

- Soonhuae, P.; Piewluang, C.; Boyle, T. Population genetics of Dalbergia cochinchinensis Pierre and implications for genetic conservation. Technical Publication No. 18, ASEAN Forest Tree Seed Centre Project, Muak-Lek, Saraburi, Thailand. (1994).

- Yooyuen, R.; Duangjai, S.; Changtragoon, S. Chloroplast DNA variation of Dalbergia cochinchinensis Pierre in Thailand and Laos. In IUFRO World Series Volume 30: Asia and the Pacific Workshop Multinational and Transboundary Conservation of Valuable and Endangered Forest Tree Species, Guangzhou, China, 5–7 December 2011.

- Hien, V.T.T.; Phong, D.T. Genetic diversity among endangered rare Dalbergia cochinchinensis (Fabaceae) genotypes in Vietnam revealed by random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and inter simple sequence repeats (ISSR) markers. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 11, 8632–8644. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, P.; Panda, P.C. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic relationships of Dalbergia species of eastern India based on RAPD and ISSR analysis. Int. J. Innov. Science Res. Technol. 2018, 3, 417–422. [Google Scholar]

- Hartvig, I.; So, T.; Changtragoon, S.; Tran, H.T.; Bouamanivong, S.; Theilade, I.; Kjaer, E.D.; Nielsen, L.R. Population genetic structure of the endemic rosewoods Dalbergia cochinchinensis and D. oliveri at a regional scale reflects the Indochinese landscape and life-history traits. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartvig, I.; Czako, M.; Kjaer, E.D.; Nielsen, L.R.; Theilade, I. The use of DNA barcoding in identification and conservation of rosewood (Dalbergia spp.). PLoS ONE. 2015, 10, e0138231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Luna, A.; Hernández-Díaz, J.C.; Wehenkel, C.; Simental-Rodríguez, S.L.; Hernández-Velasco, J.; Prieto-Ruíz, J.A. Graft survival of Pinus engelmannii Carr. in relation to two grafting techniques with dormant and sprouting buds. PeerJ. 2021, 9, e12182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, L.T.; Savolainen, V. Broad-scale amplification of matK for DNA barcoding plants a technical note. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2010, 164, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotuyo, S.; Pedraza-Ortega, E.; Martinez-Salas, E.; Linares, J.; Cabrera, L. Insights into phylogenetic divergence of Dalbergia (Leguminosae: Dalbergiae) from Mexico and Central America. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 910250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, M.A.; Blackshields, G.; Brown, N.P.; Chenna, R.; McGettigan, P.A.; McWilliam, H.; et al. Clustal W and clustal X version 2.0. Bioinform. 2007, 23, 2947–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl. Acid S. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Librado, P.; Rozas, J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinform. 2009, 25, 1451–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980, 16, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA 11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 18, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandelt, H.J.; Forster, P.; Röhl, A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999, 16, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nei, M.; Kumar, S. Molecular evolution and phylogenetics. Oxford University Press, New York, 2000.

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Niyomdham, C.; Hô, P.H.; Dy Phon, P.; Vidal, .E. Leguminoseae-Papilionoideae Dalbergieae. In: Morat, P. (ed), Flore du Cambodge du Laos et du Viêtnam. Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris. 1997.

- CTSP. Cambodian tree species. Monographs. Cambodia tree seed project, FA, Cambodia and DANIDA, Denmark. 2004.

- Huang, J.F.; Li, S.Q.; Xu, R.; Peng, Y.Q. East‒West genetic differentiation across the Indo-Burma hotspot: evidence from two closely related dioecious figs. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample no. | Sample code | Molecular marker | Sample collection site | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| matK* | ITS** | |||

| 1 | TRT-M1 | DcM1 | DcI23 | Mueang District, Trat Province |

| 2 | TRT-M2 | DcM2 | DcI24 | |

| 3 | TRT-M3 | DcM2 | DcI24 | |

| 4 | TRT-M4 | DcM1 | n/a | |

| 5 | TRT-KY1 | DcM4 | DcI21 | Khlong Yai District, Trat Province |

| 6 | TRT-KY2 | DcM3 | DcI21 | |

| 7 | TRT-KY3 | DcM4 | DcI22 | |

| 8 | TRT-KY4 | DcM3 | n/a | |

| 9 | SSK-PS1 | DcM6 | n/a | Phu Sing District, Sisaket Province |

| 10 | SSK-PS2 | DcM6 | DcI19 | |

| 11 | SSK-PS3 | DcM5 | DcI19 | |

| 12 | SSK-PS4 | n/a | DcI19 | |

| 13 | SSK-PS5 | DcM5 | DcI18 | |

| 14 | SSK-KL1 | DcM7 | DcI20 | Kantaralak District, Sisaket Province |

| 15 | SSK-KL2 | DcM7 | DcI14 | |

| 16 | SSK-KL3 | DcM7 | DcI20 | |

| 17 | SSK-KL4 | n/a | DcI14 | |

| 18 | SRN-KC1 | DcM9 | DcI18 | Kap Choeng District, Surin Province |

| 19 | SRN-KC2 | DcM8 | DcI19 | |

| 20 | SRN-KC3 | DcM9 | DcI11 | |

| 21 | SRN-KC4 | DcM8 | n/a | |

| 22 | SRI76 | DcM10 | n/a | Muak Lek District, Saraburi Province |

| 23 | SRI80 | DcM10 | n/a | |

| 24 | SRI | DcM10 | n/a | |

| 25 | SRI6 | n/a | DcI28 | |

| 26 | SRI27 | n/a | DcI29 | |

| 27 | SRI34 | n/a | DcI11 | |

| 28 | SNK-PP1 | DcM15 | DcI15 | Phu Phan District, Sakon Nakhon Province |

| 29 | SNK-PP2 | DcM14 | DcI16 | |

| 30 | SNK-PP3 | DcM13 | DcI5 | |

| 31 | SNK-PP4 | DcM12 | DcI17 | |

| 32 | SNK-PP5 | DcM11 | DcI5 | |

| 33 | SNK-M1 | DcM20 | DcI12 | Mueang District, Sakon Nakhon Province |

| 34 | SNK-M2 | DcM19 | DcI13 | |

| 35 | SNK-M3 | DcM18 | DcI5 | |

| 36 | SNK-M4 | DcM17 | DcI14 | |

| 37 | SNK-M5 | DcM16 | DcI15 | |

| 38 | SKW-WY1 | DcM23 | DcI1 | Wang Nam Yen District, Sa Kaeo Province |

| 29 | SKW-WY2 | DcM22 | DcI1 | |

| 40 | SKW-WY3 | DcM21 | DcI11 | |

| 41 | NMA-KB1 | DcM26 | DcI1 | Khonburi District, Nakhon Ratchasima Province |

| 42 | NMA-KB2 | DcM25 | DcI9 | |

| 43 | NMA-KB3 | DcM24 | DcI10 | |

| 44 | KKN-WK1 | DcM32 | DcI2 | Wiang Kao District, Khon Kaen Province |

| 45 | KKN-WK2 | DcM31 | DcI3 | |

| 46 | KKN-WK3 | DcM30 | DcI4 | |

| 47 | KKN-WK4 | DcM29 | DcI5 | |

| 48 | KKN-WK5 | DcM28 | DcI6 | |

| 49 | KKN-WK6 | DcM27 | DcI7 | |

| 50 | KKN-WK7 | n/a | DcI8 | |

| 51 | CCO-TT1 | DcM34 | DcI1 | Tha Takiap District, Chachoengsao Province |

| 52 | CCO-TT2 | DcM33 | DcI1 | |

| 53 | CCO-TT3 | DcM34 | DcI1 | |

| 54 | CCO-TT4 | DcM33 | DcI1 | |

| 55 | UBN-NC1 | n/a | DcI24 | Na Chaluai District, Ubon Ratchathani Province |

| 56 | UBN-NC2 | n/a | DcI21 | |

| 57 | UBN-NC4 | n/a | DcI21 | |

| 58 | UBN-NY1 | n/a | DcI22 | Nam Yuen District, Ubon Ratchathani Province |

| 59 | UBN-NY2 | n/a | DcI22 | |

| 60 | UBN-NY3 | n/a | DcI22 | |

| 61 | MDH8 | n/a | DcI25 | Kham Chai District, Mukdahan Province |

| 62 | MDH12 | n/a | DcI13 | |

| 63 | MDH41 | n/a | DcI25 | |

| 64 | MDH67 | n/a | DcI17 | |

| 65 | UDN36 | n/a | DcI30 | Nong Wua So District, Udon Thani Province |

| 66 | UDN37 | n/a | DcI2 | |

| 67 | UDN43 | n/a | DcI2 | |

| 68 | UDN45 | n/a | DcI31 | |

| 69 | PLK5 | n/a | DcI16 | Nakhon Thai District, Phisanulok Province |

| 70 | PLK9 | n/a | DcI26 | |

| 71 | PLK21 | n/a | DcI27 | |

| 72 | PLK32 | n/a | DcI13 | |

| Populations | ITS | matK | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | S | H | Uh | Hd±SD | Nd±SD | n | S | H | Uh | Hd±SD | Nd±SD | |

| TRT-M | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.667±0.314 | 0.0010±0.0005 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0.667±0.204 | 0.0041±0.0012 |

| TRT-KY | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0.667±0.314 | 0.0010±0.0005 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0.667±0.204 | 0.0033±0.0001 |

| SSK-KL | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0.667±0.204 | 0.0030±0.0009 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.000±0.000 | 0.0000±0.0000 |

| SSK-PS | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0.500±0.265 | 0.0008±0.0004 | 4 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 0.667±0.204 | 0.0089±0.0027 |

| SRN-KC | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1.000±0.272 | 0.0035±0.0012 | 4 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 0.667±0.204 | 0.0081±0.0025 |

| SRI | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1.000±0.272 | 0.0020±0.0007 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.000±0.000 | 0.0000±0.0000 |

| SNK-M | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 1.000±0.126 | 0.0042±0.0009 | 5 | 12 | 5 | 5 | 1.000±0.126 | 0.0073±0.0011 |

| SNK-PP | 5 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0.900±0.161 | 0.0036±0.0007 | 5 | 22 | 5 | 5 | 1.000±0.126 | 0.0122±0.0032 |

| SKW-WY | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0.667±0.314 | 0.0020±0.0009 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 1.000±0.272 | 0.0081±0.0023 |

| NMA-KB | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1.000±0.272 | 0.0020±0.0007 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 1.000±0.272 | 0.0081±0.0025 |

| KKN-WK | 7 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 1.000±0.076 | 0.0078±0.0012 | 6 | 28 | 6 | 6 | 1.000±0.096 | 0.0138±0.0034 |

| CCO-TT | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.000±0.000 | 0.0000±0.0000 | 4 | 12 | 2 | 2 | 0.667±0.204 | 0.0097±0.0030 |

| UBN-NY | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.000±0.000 | 0.0000±0.0000 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| UBN-NC | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0.667±0.314 | 0.0010±0.0005 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| UDN | 4 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0.833±0.222 | 0.0040±0.0013 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| MDH | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0.833±0.222 | 0.0038±0.0011 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| PLK | 4 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1.000±0.177 | 0.0045±0.0013 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Total | 65 | 17 | 31 | 17 | 0.968±0.008 | 0.0069±0.0003 | 48 | 66 | 34 | 25 | 0.986±0.007 | 0.0161±0.0022 |

| Populations | TRT-M | TRT-KY | SSK-KL | SSK-PS | SRN-KC | SNK-M | SNK-PP | SKW-WY | NMA-KB | KKN-WK | CCO-TT | SRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRT-M | − | 0.0061 | 0.0204 | 0.0086 | 0.0086 | 0.0072 | 0.0114 | 0.0071 | 0.0063 | 0.0111 | 0.0092 | 0.0448 |

| TRT-KY | 0.0061 | − | 0.0223 | 0.0117 | 0.0098 | 0.0074 | 0.0113 | 0.0065 | 0.0065 | 0.0123 | 0.0098 | 0.0429 |

| SSK-KL | 0.0201 | 0.0219 | − | 0.0179 | 0.0210 | 0.0225 | 0.0260 | 0.0227 | 0.0223 | 0.0235 | 0.0235 | 0.0597 |

| SSK-PS | 0.0085 | 0.0116 | 0.0177 | − | 0.0117 | 0.0132 | 0.0169 | 0.0137 | 0.0104 | 0.0146 | 0.0135 | 0.0513 |

| SRN-KC | 0.0085 | 0.0097 | 0.0207 | 0.0116 | − | 0.0108 | 0.0140 | 0.0094 | 0.0094 | 0.0127 | 0.0117 | 0.0467 |

| SNK-M | 0.0072 | 0.0073 | 0.0222 | 0.0130 | 0.0107 | − | 0.0095 | 0.0080 | 0.0091 | 0.0119 | 0.0093 | 0.0444 |

| SNK-PP | 0.0113 | 0.0112 | 0.0256 | 0.0167 | 0.0139 | 0.0095 | − | 0.0116 | 0.0122 | 0.0151 | 0.0126 | 0.0429 |

| SKW-WY | 0.0071 | 0.0065 | 0.0223 | 0.0136 | 0.0093 | 0.0080 | 0.0115 | − | 0.0094 | 0.0124 | 0.0111 | 0.0411 |

| NMA-KB | 0.0063 | 0.0065 | 0.0219 | 0.0104 | 0.0093 | 0.0090 | 0.0121 | 0.0093 | − | 0.0118 | 0.0102 | 0.0476 |

| KKN-WK | 0.0110 | 0.0122 | 0.0231 | 0.0144 | 0.0126 | 0.0118 | 0.0149 | 0.0123 | 0.0116 | − | 0.0129 | 0.0493 |

| CCO-TT | 0.0091 | 0.0097 | 0.0231 | 0.0134 | 0.0116 | 0.0093 | 0.0124 | 0.0110 | 0.0102 | 0.0128 | − | 0.0467 |

| SRI | 0.0432 | 0.0414 | 0.0572 | 0.0493 | 0.0451 | 0.0429 | 0.0414 | 0.0398 | 0.0459 | 0.0475 | 0.0451 | − |

| Populations | TRT-M | TRT-KY | SSK-KL | SSK-PS | SRN-KC | SNK-M | SNK-PP | SKW-WY | NMA-KB | KKN-WK | CCO-TT | UBN-NY | UBN-NC | MDH | UDN | PLK | SRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRT-M | − | 0.0025 | 0.0088 | 0.0046 | 0.0045 | 0.0114 | 0.0108 | 0.0050 | 0.0065 | 0.0104 | 0.0050 | 0.0035 | 0.0015 | 0.0122 | 0.0080 | 0.0103 | 0.0050 |

| TRT-KY | 0.0025 | − | 0.0073 | 0.0031 | 0.0030 | 0.0099 | 0.0093 | 0.0035 | 0.0043 | 0.0088 | 0.0035 | 0.0010 | 0.0010 | 0.0107 | 0.0063 | 0.0088 | 0.0035 |

| SSK-KL | 0.0087 | 0.0072 | − | 0.0089 | 0.0075 | 0.0047 | 0.0044 | 0.0063 | 0.0078 | 0.0060 | 0.0068 | 0.0083 | 0.0073 | 0.0064 | 0.0072 | 0.0049 | 0.0048 |

| SSK-PS | 0.0046 | 0.0031 | 0.0088 | − | 0.0020 | 0.0120 | 0.0114 | 0.0053 | 0.0068 | 0.0104 | 0.0056 | 0.0041 | 0.0031 | 0.0129 | 0.0078 | 0.0110 | 0.0049 |

| SRN-KC | 0.0045 | 0.0030 | 0.0075 | 0.0020 | − | 0.0109 | 0.0103 | 0.0040 | 0.0055 | 0.0091 | 0.0045 | 0.0040 | 0.0030 | 0.0117 | 0.0064 | 0.0098 | 0.0035 |

| SNK-M | 0.0113 | 0.0098 | 0.0046 | 0.0119 | 0.0108 | − | 0.0034 | 0.0094 | 0.0109 | 0.0069 | 0.0094 | 0.0109 | 0.0099 | 0.0046 | 0.0098 | 0.0041 | 0.0083 |

| SNK-PP | 0.0107 | 0.0092 | 0.0043 | 0.0113 | 0.0102 | 0.0034 | − | 0.0088 | 0.0103 | 0.0065 | 0.0088 | 0.0103 | 0.0093 | 0.0038 | 0.0091 | 0.0035 | 0.0077 |

| SKW-WY | 0.0050 | 0.0035 | 0.0062 | 0.0052 | 0.0040 | 0.0093 | 0.0087 | − | 0.0022 | 0.0078 | 0.0010 | 0.0045 | 0.0035 | 0.0102 | 0.0053 | 0.0083 | 0.0023 |

| NMA-KB | 0.0065 | 0.0043 | 0.0077 | 0.0067 | 0.0055 | 0.0108 | 0.0102 | 0.0022 | − | 0.0091 | 0.0015 | 0.0040 | 0.0050 | 0.0117 | 0.0063 | 0.0098 | 0.0038 |

| KKN-WK | 0.0104 | 0.0087 | 0.0060 | 0.0103 | 0.0090 | 0.0068 | 0.0065 | 0.0078 | 0.0090 | − | 0.0084 | 0.0095 | 0.0089 | 0.0077 | 0.0067 | 0.0065 | 0.0065 |

| CCO-TT | 0.0050 | 0.0035 | 0.0067 | 0.0056 | 0.0045 | 0.0093 | 0.0087 | 0.0010 | 0.0015 | 0.0084 | − | 0.0045 | 0.0035 | 0.0102 | 0.0060 | 0.0083 | 0.0030 |

| UBN-NY | 0.0035 | 0.0010 | 0.0082 | 0.0041 | 0.0040 | 0.0108 | 0.0102 | 0.0045 | 0.0040 | 0.0094 | 0.0045 | − | 0.0020 | 0.0117 | 0.0068 | 0.0098 | 0.0045 |

| UBN-NC | 0.0015 | 0.0010 | 0.0072 | 0.0031 | 0.0030 | 0.0098 | 0.0092 | 0.0035 | 0.0050 | 0.0089 | 0.0035 | 0.0020 | − | 0.0107 | 0.0065 | 0.0088 | 0.0035 |

| MDH | 0.0121 | 0.0106 | 0.0064 | 0.0127 | 0.0116 | 0.0046 | 0.0038 | 0.0101 | 0.0116 | 0.0077 | 0.0101 | 0.0116 | 0.0106 | − | 0.0102 | 0.0039 | 0.0092 |

| UDN | 0.0080 | 0.0062 | 0.0071 | 0.0078 | 0.0064 | 0.0097 | 0.0090 | 0.0052 | 0.0062 | 0.0066 | 0.0060 | 0.0067 | 0.0065 | 0.0101 | − | 0.0085 | 0.0043 |

| PLK | 0.0102 | 0.0087 | 0.0049 | 0.0109 | 0.0097 | 0.0040 | 0.0034 | 0.0082 | 0.0097 | 0.0064 | 0.0082 | 0.0097 | 0.0087 | 0.0039 | 0.0084 | − | 0.0073 |

| SRI | 0.0050 | 0.0035 | 0.0047 | 0.0049 | 0.0035 | 0.0083 | 0.0077 | 0.0023 | 0.0038 | 0.0065 | 0.0030 | 0.0045 | 0.0035 | 0.0091 | 0.0042 | 0.0072 | − |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).