Submitted:

28 May 2024

Posted:

28 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2.1. Sampling

2.2. DNA Extraction and SNPs Analysis

2.3. Genetic Diversity and Population Differentiation

2.4. Bayesian Clustering Analysis

2.5. Genetic Assignment

3. Results

3.1. Genetic Diversity

3.2. Population Differentiation

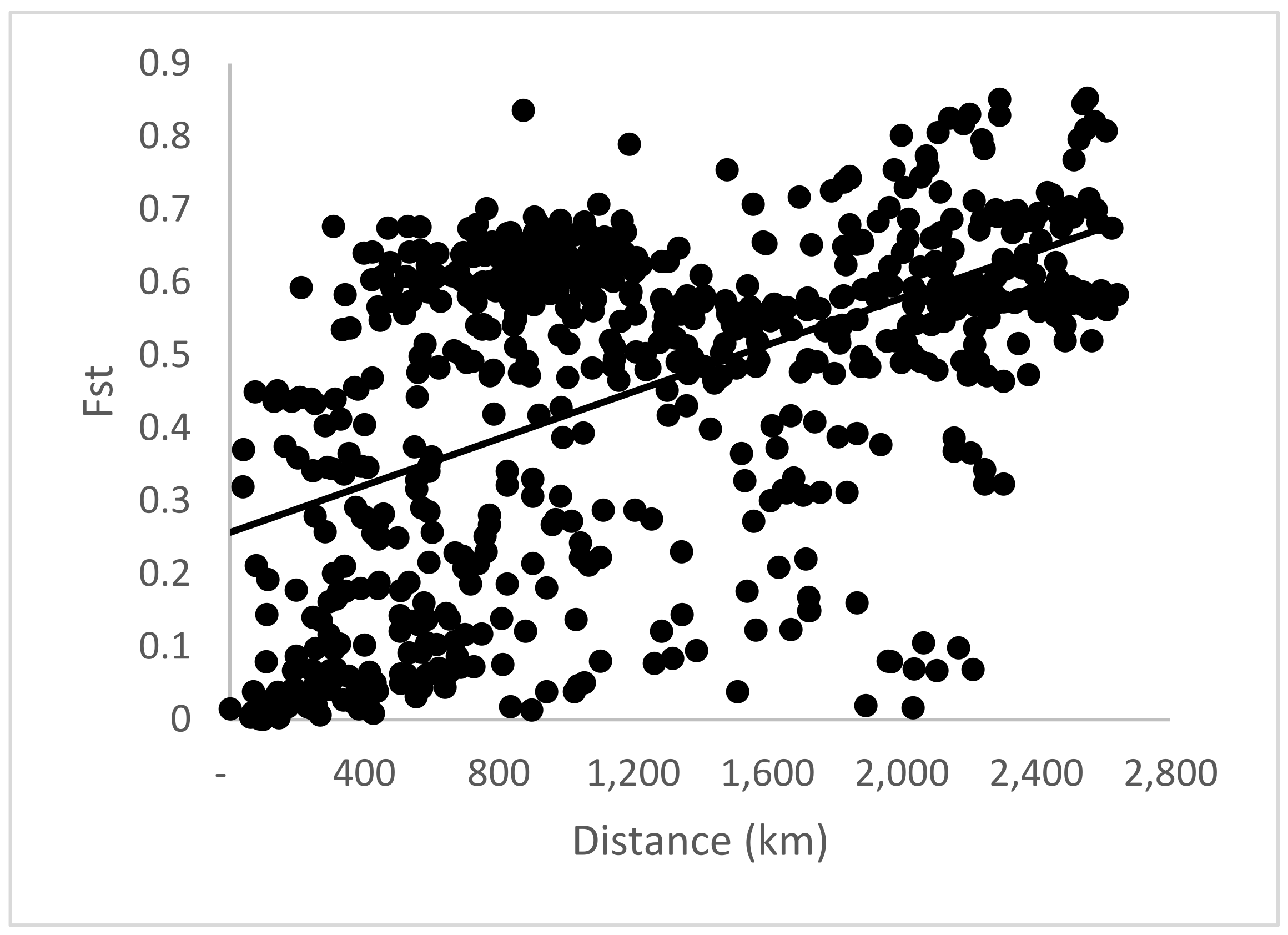

3.3. Isolation by Distance

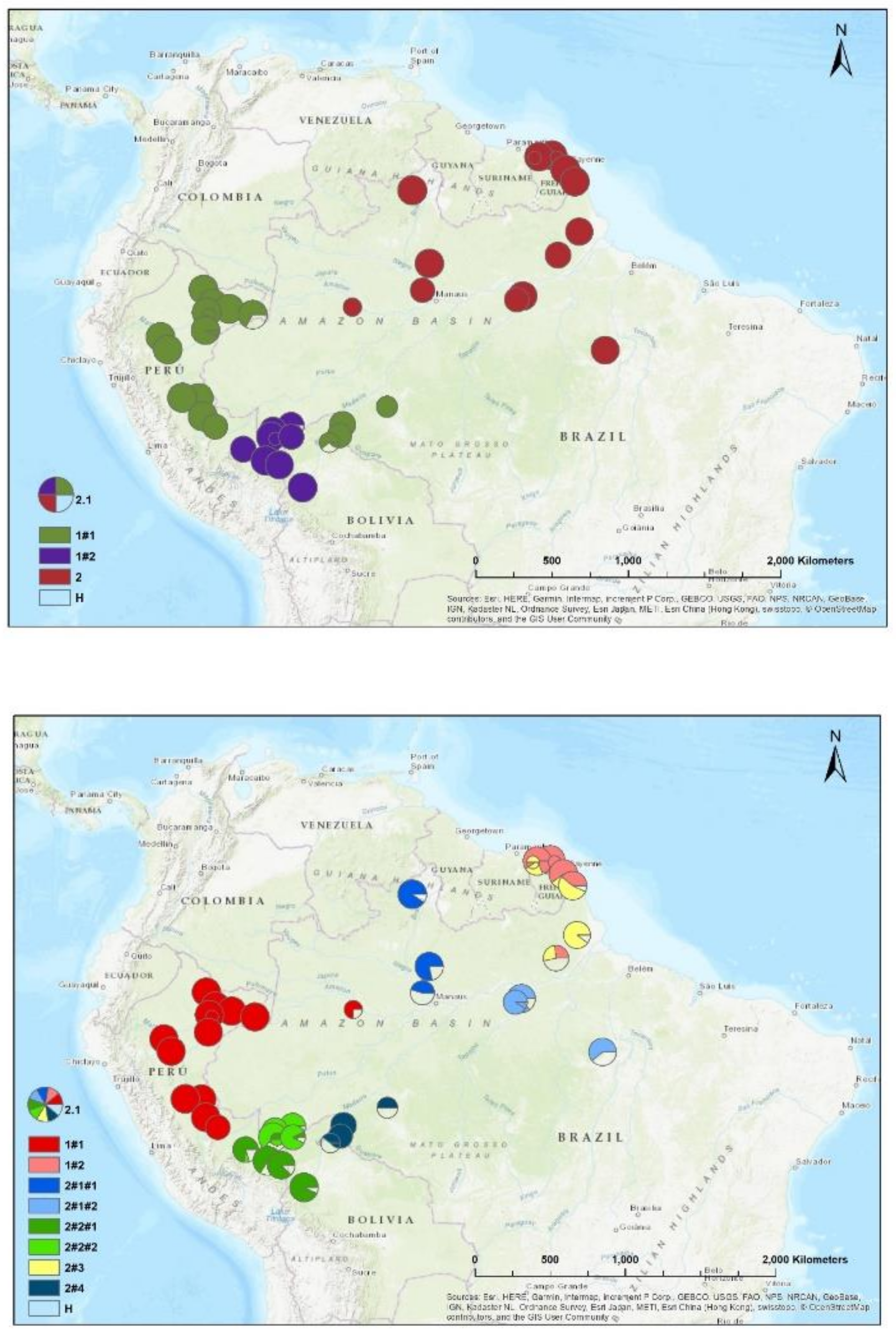

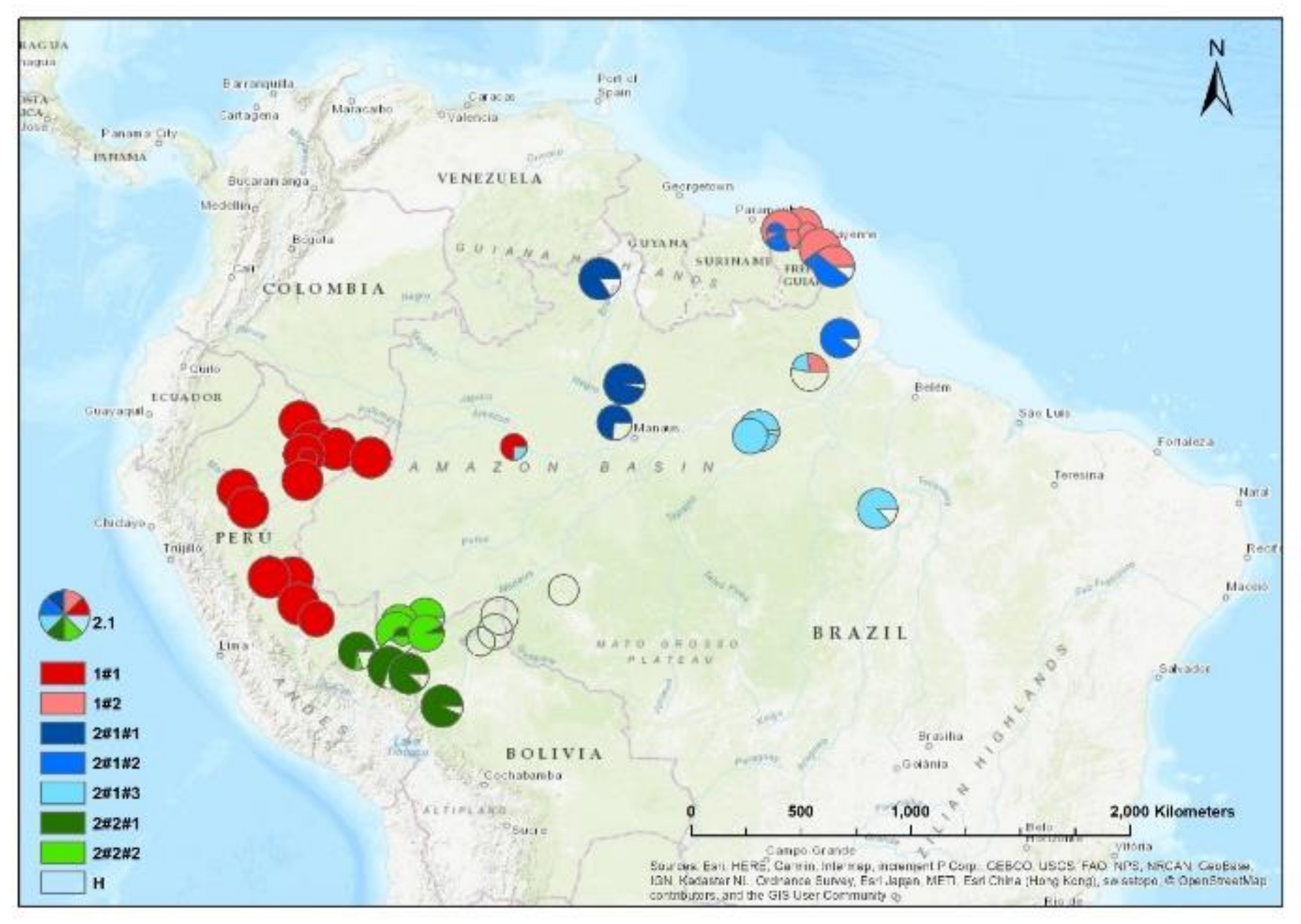

3.4. Bayesian Cluster Analysis

3.5. Genetic Assignment

4. Discussion

4.1. Genetic Diversity

4.2. Population Genetic Differentiation

4.3. Genetic Assignment and Practical Application

4.4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaves, C.L.; Degen, B.; Pakull, B.; Mader, M.; Honorio, E.; Ruas, P.; Tysklind, N.; Sebbenn, A.M. Assessing the ability of chloroplast and nuclear DNA gene markers to verify the geographic origin of Jatoba (Hymenaea courbaril L.) timber. J. Hered. 2018, 109, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, C.L.; Blanc-Jolivet, C.; Sebbenn, A.M.; Mader, M.; Meyer-Sand, B.R.V.; Paredes-Villanueva, K.; Coronado, E.N.H.; Garcia-Davila, C.; Tysklind, N.; Troispoux, V.; et al. Nuclear and chloroplastic SNP markers for genetic studies of timber origin for Hymenaea trees. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2019, 11, 329–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronado, E.N.H.; Blanc-Jolivet, C.; Mader, M.; García-Dávila, C.R.; Gomero, D.A.; del Castillo, D.T.; Llampazo, G.F.; Pizango, G.H.; Sebbenn, A.M.; Meyer-Sand, B.R.V.; et al. SNP markers as a successful molecular tool for assessing species identity and geographic origin of trees in the economically important South American legume Genus Dipteryx. J. Hered. 2020, 111, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebbenn, A.M.; Degen, B.; Azevedo, V.C.R.; Silva, M.B.; Lacerda, A.E.B.; Ciampi, A.Y.; Kanashiro, M.; Carneiro, F.S.; Thompson, I.; Loveless, M.D. Modelling the long-term impacts for selective logging on genetic diversity and demographic structure of four tropical tree species in the Amazon Forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 254, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, A.E.B.; Nimmo, E.R.; Sebbenn, A.M. Modeling the long-term impacts of logging on genetic diversity and demography of Hymenaea courbaril. For. Sci. 2013, 59, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Bem, E.A.; Bittencourt, J.V.M.; Moraes, M.L.T.; Sebbenn, A.M. Cenários de corte seletivo de árvores na diversidade genética e área basal de populações de Araucaria angustifolia com base em modelagem Ecogene. Sci. For. 2015, 43, 453–466. [Google Scholar]

- Vinson, C.C.; Kanashiro, M.; Sebbenn, A.M.; Williams, T.C.R.; Harris, S.A.; Boshier, D.H. Long-term impacts of selective logging on two Amazonian tree species with contrasting ecological and reproductive characteristics: Inferences from Ecogene model simulations. Heredity 2015, 115, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gattia, TC et al. The number of tree species on Earth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119(6), e2115329119. [CrossRef]

- Barber, C.P.; Cochrane, M.A.; Souza Jr, C.; Laurance, W.F. Roads, deforestation, and the mitigating effect of protected areas in the Amazon. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 177, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.A. Forest concession policies and revenue systems: Country experience and policy changes for sustainable tropical forestry, World Bank Publications. 2002.

- Degen, D.; Ward, S.E.; Lemes, M.R.; Navarro, C.; Cavers, S.; Sebbenn, A.M. Verifying the geographic origin of mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla King) with DNA-fingerprints. Forensic Sci. Int-Gen. 2013, 7, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, A.J.; Dormontt, E.E.; Bowie, M.J.; Degen, B.; Gardner, S.; Thomas, D.; Clarke, C.; Rimbawanto, A.; Wiedenhoeft, A.; Yin, Y. Opportunities for improved transparency in the timber trade through scientific verification. BioScience 2016, 66, 990–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CITES, Comércio Internacional das Espécies da Flora e Fauna Selvagens em Perigo de Extinção, 2021. Disponível em. Available online: https://cites.org/esp/app/appendices.php (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Lescuyer, G.; Ndotit, S.; Ndong, L.B.B.; Tsanga, R.; Cerutti, P.O. Policy options for improved integration of domestic timber markets under the voluntary partnership agreement (VPA) regime in Gabon. Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), 2014.

- Federal Police Brazil, GOV, 2022. Disponível em. Available online: https://www.gov.br/pf/pt-br/search?SearchableText=madeira%20ilegal%20extra%C3%ADda%20da%20Amaz%C3%B4nia (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Farias, Elaíze. 2019. “Amazônia em Chamas: 90% da madeira exportada são ilegais, diz Polícia Federal.” Amazônia Real, September 13. Available online: https://amazoniareal.com.br/amazonia-em-chamas-90-da-madeira-exportada-sao-ilegais-diz-policia-federal/67 (accessed on 31 July 2023).

- Perez Coelho, M.; Sanz, J.; Cabezudo, M. Analysis of volatile components of oak wood by solvent extraction and direct thermal desorption-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Chromat. 1997, 778, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidelis, C.H.V.; Augusto, F.; Sampaio, P.T.B.; Krainovic, P.M.; Barata, L.E.S. Chemical characterization of rosewood (Aniba rosaeodora Ducke) leaf essential oil by comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography coupled with quadrupole mass spectrometry. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2012, 24, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Villanueva, K.; Espinoza, E.; Ottenburghs, J.; Sterken, M.G.; Bongers, F.; Zuidema, P.A. Chemical differentiation of Bolivian Cedrela species as a tool to trace illegal timber trade. Forestry: An Internat. J. For. Resear. 2018, 91, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deklerck, V.; Finch, K.; Gasson, P.; Van den Bulcke, J.; Van Acker, J.; Beeckman, H.; Espinoza, E. Comparison of species classification models of mass spectrometry data: Kernel discriminant analysis vs random forest; A case study of Afrormosia (Pericopsis elata (Harms) Meeuwen). Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2017, 1582–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagawa, A.; Leavitt, S.W. Stable carbon isotopes of tree rings as a tool to pinpoint the geographic origin of timber. J. Wood Sci. 2010, 56, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergo, M.C.J.; Pastore, T.C.M.; Coradin, V.T.R.; Wiedenhoeft, A.C.; Braga, J.W.B. NIRS identification of Swietenia macrophylla is robust across specimens from 27 countries. IAWA J. 2016, 37, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasson, P.; Baas, P.; Wheeler, E. Wood anatomy of Cites-listed tree species. IAWA J. 2011, 32, 155–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, R.; Wiemann, M.C.; Olivares, C. Identification of endangered or threatened Costa Rican tree species by wood anatomy and fluorescence activity. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2013, 61, 1113–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Tnah, L.H.; Lee, S.L.; Ng, K.K.S.; Tani, N.; Bhassu, S.; Othman, R.Y. Geographical traceability of an important tropical timber (Neobalanocarpus heimii) inferred from chloroplast DNA. For. Ecol. Manage. 2009, 258, 1918–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, A.J.; Wong, K.N.; Tiong, Y.S.; Iyerh, S.; Chew, F.T. A DNA method to verify the integrity of timber supply chains; confirming the legal sourcing of merbau timber from logging concession to sawmill. Silvae Genet. 2010, 59, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tnah, L.H.; Lee, S.L.; Ng, K.K.S.; Faridah, Q.Z.; Faridah-Hanum, I. Forensic DNA profiling of tropical timber species in Peninsular Malaysia. For. Ecol. Manage. 2010, 259, 1436–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolivet, C.; Degen, D. Use of DNA fingerprints to control the origin of sapelli timber (Entandrophragma cylindricum) at the forest concession level in Cameroon. Forensic Sci. Int-Gen. 2012, 6, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dormontt, E.E.; Boner, M.; Braun, B.; Breulmann, B.; Degen, B.; Espinoza, E.; Gardner, S.; Guillery, P.; Hermanson, J.C.; Koch, G.; et al. Forensic timber identification: It's time to integrate disciplines to combat illegal logging. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 191, 790–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc-Jolivet, C.; Yanbaev, Y.; Kersten, B.; Degen, B. A set of SNP markers for timber tracking of Larix spp. in Europe and Russia. Forestry: An. Int. J. For. Resear. 2018, 91, 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlam, M.; de Groot, G.A.; Boom, A.; Copini, P.; Laros, I.; Veldhuijzen, K.; Zakamdi, D.; Zuidema, P.A. Developing forensic tools for an African timber: Regional origin is revealed by genetic characteristics, but not by isotopic signature. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 220, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeele, S.V.; Hardy, O.J.; Beeckman, H.; Ilondea, B.A.; Janssens, S.B. Genetic markers for species conservation and timber tracking: Development of microsatellite primers for the Tropical African tree species Prioria balsamifera and Prioria oxyphylla. Forests 2019, 10, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Villanueva, K.; Blanc-Jolivet, C.; Mader, M.; Coronado, E.N.H.; Garcia-Davila, C.; Sebbenn, A.M.; Meyer-Sand, B.R.V.; Caron, H.; Tysklind, N.; Cavers, S.; et al. Nuclear and plastid SNP markers for tracing Cedrela timber in the tropics. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2020, 12, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, A.A.; Silva, M.F.; Alencar, J.C. Essências madeireiras da Amazonia. INPA, 1979, v.1.

- Sampaio, P.T.B.; Barbosa, A.P.; Fernandes, N.P. Ensaio de espaçamento com caroba - Jacaranda copaia (AUBL.) D. DON. BIGNONTACEAE. Acta Amaz. 1989, 9, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, A.H. Bignoniaceae – Part II (Tribe Tecomeae). Flora Neotropica 1992, 25, 1–370. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/i400045.

- Maues, M.M.; Oliveira, P.E.A.M.; Kanashiro, M. Pollination biology in Jacaranda copaia (Aubl.) D. Don. (Bignoniaceae) at the “Floresta Nacional do Tapajós”, Central Amazon. Rev. Brasil. Bot. 2008, 31, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, T.; Veges, S.; Aldrich, P.; Hamrick, J.L. Mating systems of three tropical dry Forest tree species. Biotropica 1998, 30, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinson, C.C.; Kanashiro, M.; Harris, S.A.; Boshier, D.H. Impacts of selective logging on inbreeding and gene flow in two Amazonian timber species with contrasting ecological and reproductive characteristics. Mol. Ecol. 2015, 24, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumolin, S.; Demesure, B.; Petit, R.J. Inheritance of chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes in pediculate oak investigated with an efficient PCR method. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1995, 91, 1253–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebbenn, A.M.; Blanc-Jolivet, C.; Mader, M. Meyer-Sand, B.R.V.; Paredes-Villanueva, K.; Coronado, E.N.H.; Garcia-Davila, C.; Tysklind, N.; Troispoux, V.; Delcamp, A.; Degen, D. Nuclear and plastidial SNP and INDEL markers for genetic tracking studies of Jacaranda copaia. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2019, 11, 341–343. [CrossRef]

- Degen B, Blanc-Jolivet C, Stierand K, Gillet, E. 2017. A nearest neighbour approach by genetic distance to the assignment of individual trees to geographic origin. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 27:132–141.

- Loiselle, B.A.; Sork, V.L.; Nason, J.; Graham, C. Spatial genetic structure of a tropical understory shrub, Psychotria officinalis (Rubiaceae). Am. J. Bot. 1995, 82, 1420–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, O.J.; Vekemans, X. SPAGeDI: A versatile computer program to analyses spatial genetic structure at the individual or population levels. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2002, 2, 618–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakobsson, M.; Rosenberg, N.A. CLUMPP: A cluster matching and permutation program for dealing with label switching and multimodality in analysis of population structure. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 1801–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopelman, N.M.; Mayzel, J.; Jakobsson, M.; Rosenberg, N.A.; Mayrose, I. Clumpak: A program for identifying clustering modes and packaging population structure inferences across K. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2015, 15, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rannala, B.; Mountain, J.L. Detecting immigration by using multilocus genotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997, 94, 9197–9201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piry, S.; Alapetite, A.; Cornuet, J.M.; Paetkau, D.; Baudouin, L.; Estoup, A. GENECLASS2: A software for genetic assignment and first-generation migrant detection. J. Hered. 2004, 95, 536–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efron, B. Estimating the error rate of a prediction rule – improvement on cross validation. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1983, 78, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornuet, J.M.; Piry, S.; Luikart, G.; Estoup, A.; Solignac, M. New methods employing multilocus genotypes to select or exclude populations as origins of individuals. Genetics 1999, 153, 1989–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlund, S. Composition of populations and correlation appearances viewed in relation to the studies of inheritance. Hereditas 1928, 11, 65–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, R.; Linacre, A. Wildlife forensic science: A review of genetic geographic origin assignment. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2015, 18, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scotti-Saintagne, C.; Dick, C.W.; Caron, H.; Vendramin, G.G.; Guichoux, E.; Buonamici, A.; Duret, C.; Sire, P.; Valencia, R.; Lemes, M.R.; et al. Phylogeography of a species complex of lowland Neotropical rain forest trees (Carapa, Meliaceae). J. Biogeogr. 2013, 40, 676–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti-Saintagne, C.; Dick, C.W.; Caron, H.; Vendramin, G.G.; Troispoux, V.; Sire, P.; Casalis, M.; Buonamici, A.; Valencia, R.; Lemes, M.R.; et al. Amazon diversification and cross-Andean dispersal of the widespread Neotropical tree species Jacaranda copaia (Bignoniaceae). J. Biogeogr. 2013, 40, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Sand, B.R.V.; Blanc-Jolivet, C.; Mader, M.; Paredes-Villanueva, K.; Tysklind, N.; Sebbenn, A.M.; Guichoux, E.; Degen, D. Development of a set of SNP markers for population genetics studies of Ipe (Handroanthus sp.), a valuable tree genus from Latin America. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2018, 10, 779–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.K.; Lee, S.L.; Tnah, L.H.; Nurul-Farhanah, Z.; Ng, C.H.; Lee, C.T.; Tani, N.; Diway, B.; Lai, P.S.; Khoo, E. Forensic timber identification: A case study of a cites listed species, Gonystylus bancanus (thymelaeaceae). Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2016, 23, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, B.; Blanc-Jolivet, C.; Stierand, K.; Gillet, E. A nearest neighbour approach by genetic distance to the assignment of individual trees to geographic origin. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2017, 27, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jardine, D.I.; Blanc-Jolivet, C.; Dixon, R.R.M.; Dormontt, E.E.; Dunker, B.; Gerlach, J.; Kersten, B.; Van Dijk, K.J.; Degen, B.; Lowe, A.J. Development of SNP markers for Ayous (Triplochiton scleroxylon K. Schum) an economically important tree species from tropical West and Central Africa. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2016, 8, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakull, B.; Mader, M.; Kersten, B.; Ekue, M.R.M.; Dipelet, U.G.B.; Paulini, M.; Bouda, Z.H.N.; Degen, B. Development of nuclear, chloroplast and mitochondrial SNP markers for Khaya sp. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2016, 8, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, H.; Cronn, R.; Yanbaev, Y.; Jennings, T.; Mader, M.; Degen, B.; Kersten, B. Development of molecular markers for determining continental origin of wood from white oaks (Quercus L. sect. Quercus). PloS ONE 2016, 11, e0158221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Villanueva, K.; de Groot, G.A.; Laros, I.; Bovenschen, J.; Bongers, F.; Zuidema, P.A. Genetic differences among Cedrela odorata sites in Bolivia provide limited potential for fine-scale timber tracing. Tree Genet. Genome 2019, 15, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tysklind, N.; Blanc-Jolivet, C.; Mader, M.; Meyer-Sand, B.R.V.; Paredes-Villanueva, K.; Coronado, E.N.H.; Garcia-Davila, C.; Sebbenn, A.M.; Caron, K.; Troispoux, V.; et al. Development of nuclear and plastid SNP and INDEL markers for population genetic studies and timber traceability of Carapa species. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2019, 11, 337–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakull, B.; Schindler, L.; Mader, M.; Kerten, B.; Blanc-Jolivet, C.; Paulini, M.; Lemes, M.R.; Ward, S.E.; Navarro, C.M.; Cavers, S.; et al. Development of nuclear SNP markers for Mahogany (Swietenia spp.). Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2020, 12, 585–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Population | Lat | Long | Abbrev | ||

| 1-F. Guiana | Counami | 30 | 5,41543 | -53,175 | 1FG-Co | 32 |

| 2-F. Guiana | Sinamary | 2 | 5,2884 | -52,916 | ||

| 3-F. Guiana | Piste de Paul Isnard | 27 | 5,33216 | -53,957 | 2FG-Is | 29 |

| 4-F. Guiana | Acapou | 2 | 5,27343 | -54,218 | ||

| 5-F. Guiana | Route de Cocoa | 30 | 4,56779 | -52,406 | 3FG-Ro | 32 |

| 6-F. Guiana | Regina | 2 | 4,13118 | -52,088 | ||

| 7-F. Guiana | Saut Maripa | 28 | 3,87833 | -51,857 | 4FG-Ma | 28 |

| 8-Brazil | ESEC de Maraca-RR | 31 | 3,37032 | -61,444 | 5BW-Ma | 31 |

| 9-Brazil | Flona de Anauá e arredores-Rorainópolis-RR | 28 | -0,9339 | -60,451 | 6BW-An | 28 |

| 10-Brazil | AMATA Flona do Jamari-RO | 8 | -9,4014 | -62,911 | 7BW-Ja | 8 |

| 11-Brazil | ESEC do Jarí | 15 | -0,4955 | -52,829 | 8BW-Jr | 15 |

| 12-Brazil | Resex Chico Mendes-Xapuri-AC (AMATA-Flona do Jamari) | 16 | -10,504 | -68,595 | 9BW-Xa | 16 |

| 13-Brazil | Resex Chico Mendes-Comunidade Cumaru-Assis-AC | 15 | -10,772 | -69,647 | 10BW-Co | 15 |

| 14-Brazil | FLONA Amapá-AP | 20 | 0,52785 | -51,128 | 11BE-Am | 20 |

| 15-Brazil | PARNA da Ana Avilhanas-AM | 11 | -2,5345 | -60,837 | 12BE-Av | 11 |

| 16-Brazil | Flona de Tapajós-PA | 27 | -2,8687 | -54,92 | 13BE-Ta | 27 |

| 17-Brazil | Resex Tapajós-Arapins-PA | 11 | -3,0792 | -55,278 | 14BE-Ar | 11 |

| 18-Brazil | FLONA Tefé-AM | 4 | -3,5248 | -64,972 | 15BE-Te | 4 |

| 19-Brazil | FLONA do Carajás | 23 | -6,0628 | -50,059 | 16BE-Ca | 23 |

| 20-Peru | Dpto Loreto, Maynas, El Napo, Huiririma Native Community | 26 | -2,4761 | -73,744 | 17PN-Hu | 26 |

| 21-Peru | Huaman Urco | 27 | -3,3128 | -73,198 | 18PN-Ur | 27 |

| 22-Peru | Dpto Loreto, Maynas, Las Amazonas, Est. Biológica Madreselva | 28 | -3,6312 | -72,233 | 19PN-Ma | 28 |

| 23-Peru | Dpto Loreto, Mayna, Iquitos, Comunidad Campesina Yarina | 28 | -3,827 | -73,567 | 20PN-Ya | 28 |

| 24-Peru | Allpahuayo | 2 | -3,9544 | -73,422 | ||

| 25-Peru | Dpto Loreto, Mar. Ramón Castilla, C. Poblado Unión Progresista | 27 | -3,9727 | -70,841 | 21PN-Pr | 29 |

| 26-Peru | Dpto Loreto, Requena, Jenaro Herrera Research Centre | 11 | -4,8966 | -73,646 | 22PN-Ce | 11 |

| 27-Peru | Jenaro Herrera | 25 | -4,9158 | -73,649 | 23PN-He | 25 |

| 28-Peru | Dpto Loreto, Alto Amazonas, Jeberos, Centro Poblado Jeberos | 26 | -5,2598 | -76,317 | 24PN-Je | 26 |

| 29-Peru | Shucushuyacu | 27 | -6,0199 | -75,854 | 25PN-Sh | 27 |

| 30-Peru | Dpto Ucayali, Cor. Portillo, Con. Forestal-Oxigeno para el Mundo | 29 | -8,8869 | -74,034 | 26PS-Po | 29 |

| 31-Peru | Dpto Ucayali, Padre Abad, Macuya Forestry Research Station | 30 | -8,8766 | -75,014 | 27PS-Pa | 30 |

| 32-Peru | Dpto Ucayali, Atalaya, Tahuania, Concesión Forestal-Javier Díaz | 29 | -9,9803 | -73,817 | 28PS-Di | 29 |

| 33-Peru | Dpto Ucayali, Atalaya, Raymondi, Comunidad San Juan de Inuya | 12 | -10,582 | -73,071 | 29PS-In | 12 |

| 34-Peru | Dpto Madre de Dios, Tahuamanu, Concesión Forestal Maderacre | 31 | -11,145 | -69,758 | 30PS-Md | 33 |

| 35-Peru | Ibéria | 2 | -11,299 | -69,524 | ||

| 36-Peru | Dpto Madre de Dios, P.N. Manu, Est. Biológica Cocha Cashu | 15 | -11,903 | -71,403 | 31PS-Ca | 15 |

| 37-Peru | Dpto Madre de Dios, Manu, Estación Biológica Los Amigos | 30 | -12,565 | -70,088 | 32PS-Am | 30 |

| 38-Peru | Dpto Madre de Dios, R. Nac. Tambopata, La Torre-Sandoval | 24 | -12,832 | -69,284 | 33PS-Ta | 24 |

| 39-Bolivia | Riberalta, MABET | 15 | -10,442 | -65,55 | 34Bo-Ri | 15 |

| 40-Bolivia | Riberalta, El Desvelo | 11 | -11,093 | -65,746 | 35Bo-De | 11 |

| 41-Bolivia | Cobija, Road - Bella Vista | 13 | -11,198 | -68,287 | 36Bo-Vi | 13 |

| 42-Bolivia | Riberalta, El Chorro | 5 | -11,514 | -66,327 | 37Bo-Ch | 5 |

| 43-Bolivia | Rurrenabaque, Área Protegida Madidi | 29 | -14,162 | -67,905 | 38Bo-Ma | 29 |

| nSNP | CpMtSNPs | |||||||||

| Sample | ||||||||||

| 1FG-Co | 32 | 122 | 50.4 | 0.023 | 0.028 | 0.005 | 16 | 6.7 | 0.012 | 45.3 |

| 2FG-Is | 29 | 190 | 69 | 0.109 | 0.197 | 0.25* | 17 | 13.3 | 0.017 | 62.5 |

| 3FG-Ro | 32 | 196 | 71.7 | 0.094 | 0.202 | 0.295* | 16 | 6.7 | 0.013 | 64.1 |

| 4FG-Ma | 28 | 195 | 72.6 | 0.148 | 0.254 | 0.286* | 16 | 13.3 | 0.009 | 65.7 |

| 5BW-Ma | 31 | 193 | 82.3 | 0.299 | 0.309 | 0.005 | 16 | 6.7 | 0.029 | 73.4 |

| 6BW-An | 28 | 195 | 70.8 | 0.291 | 0.292 | -0.022 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 72.7 |

| 7BW-Já | 8 | 207 | 80.5 | 0.194 | 0.298 | 0.198* | 17 | 13.3 | 0.036 | 72.6 |

| 8BW-Jr | 15 | 207 | 83.2 | 0.205 | 0.287 | 0.057 | 16 | 13.3 | 0.04 | 75 |

| 9BW-Xa | 16 | 204 | 72.6 | 0.278 | 0.29 | -0.021 | 16 | 6.7 | 0.016 | 75 |

| 10BW-Cu | 15 | 147 | 83.2 | 0.261 | 0.275 | 0.016 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 73.5 |

| 11BE-Am | 20 | 204 | 75.2 | 0.215 | 0.231 | 0.052 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 66.4 |

| 12BE-Av | 11 | 207 | 61.9 | 0.278 | 0.29 | -0.021 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 64.8 |

| 13BE-Ta | 27 | 197 | 83.2 | 0.261 | 0.275 | 0.016 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 74.2 |

| 14BE-Ar | 11 | 183 | 69 | 0.238 | 0.276 | 0.078 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 68 |

| 15BE-Te | 4 | 207 | 83.2 | 0.141 | 0.257 | 0.057 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 73.5 |

| 16BE-Ca | 23 | 190 | 81.4 | 0.275 | 0.282 | -0.019 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 75 |

| 17PN-Hu | 26 | 149 | 30.1 | 0.053 | 0.059 | 0.017 | 17 | 13.3 | 0.077 | 28.1 |

| 18PN-Ur | 27 | 147 | 31.9 | 0.06 | 0.066 | 0.018 | 17 | 13.3 | 0.098 | 29.7 |

| 19PN-Ma | 28 | 147 | 30.1 | 0.054 | 0.066 | 0.031 | 19 | 20 | 0.075 | 28.9 |

| 20PN-Ya | 28 | 147 | 30.1 | 0.059 | 0.064 | 0.024 | 16 | 6.7 | 0.034 | 27.4 |

| 21PN-Pr | 29 | 142 | 30.1 | 0.065 | 0.069 | 0.016 | 19 | 26.7 | 0.103 | 29.7 |

| 22PN-Ce | 11 | 146 | 25.7 | 0.043 | 0.065 | 0.072 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 22.7 |

| 23PN-He | 25 | 145 | 29.2 | 0.05 | 0.056 | 0.018 | 16 | 20 | 0.017 | 28.1 |

| 24PN-Je | 26 | 142 | 28.3 | 0.041 | 0.061 | 0.087* | 19 | 26.7 | 0.049 | 28.1 |

| 25PN-Sh | 27 | 147 | 26.5 | 0.047 | 0.053 | 0.028 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 23.4 |

| 26PS-Po | 29 | 146 | 30.1 | 0.046 | 0.075 | 0.087* | 16 | 6.7 | 0.009 | 27.4 |

| 27PS-Pa | 30 | 140 | 30.1 | 0.063 | 0.064 | 0.02 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 26.6 |

| 28PS-Di | 29 | 139 | 23.9 | 0.054 | 0.061 | 0.024 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 21.1 |

| 29PS-In | 12 | 213 | 23 | 0.056 | 0.061 | 0.017 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 20.3 |

| 30PS-Ma | 33 | 206 | 88.5 | 0.297 | 0.315 | 0.045 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 78.1 |

| 31PS-Ca | 15 | 213 | 82.3 | 0.271 | 0.31 | 0.073 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 72.7 |

| 32PS-Am | 30 | 209 | 88.5 | 0.312 | 0.317 | -0.01 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 78.1 |

| 33PS-Ta | 24 | 209 | 85 | 0.284 | 0.314 | 0.08 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 75 |

| 34Bo-Mb | 15 | 207 | 84.1 | 0.321 | 0.324 | -0.026 | 16 | 6.7 | 0.034 | 75 |

| 35Bo-De | 11 | 206 | 84.1 | 0.297 | 0.312 | -0.012 | 16 | 6.7 | 0.036 | 75 |

| 36Bo-Vi | 13 | 205 | 82.3 | 0.313 | 0.313 | -0.023 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 72.7 |

| 37Bo-Ch | 5 | 212 | 82.3 | 0.34 | 0.348 | -0.086 | 19 | 26.7 | 0.16 | 75.8 |

| 38Bo-Ma | 29 | 226 | 87.6 | 0.322 | 0.313 | -0.032 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 77.3 |

| Overall | 832 | 183 | 100 | 0.178 | 0.204 | 0.086* | 15.9 | 6.7 | 0.024 | 55.9 |

| F. Guiana | 121 | 200 | 76.1 | 0.095 | 0.192 | 0.506* | 18 | 20 | 0.013 | 69.5 |

| Brazil | 209 | 226 | 100 | 0.261 | 0.354 | 0.264* | 30 | 100 | 0.251 | 100 |

| Peru | 429 | 217 | 92.9 | 0.111 | 0.222 | 0.498* | 23 | 53.3 | 0.105 | 88.3 |

| Bolivia | 73 | 218 | 92.9 | 0.319 | 0.359 | 0.113* | 20 | 33.3 | 0.154 | 85.9 |

| Sample | nCpMtSNPs (128) | nSNPs (113) | CpMtSNPs (15) | |

| All populations | 38 | 0.484 ± 0.043* | 0.415 ± 0.032* | 0.942 ± 0.042* |

| Countries | 4 | 0.295 ± 0.036* | 0.233 ± 0.022* | 0.695 ± 0.144* |

| French Guiana | 4 | 0.12 ± 0.017* | 0.117 ± 0.017* | 0.011 ± 0.002 |

| Brazil | 12 | 0.299 ± 0.049* | 0.224 ± 0.03* | 0.925 ± 0.103* |

| Peru | 17 | 0.466 ± 0.056* | 0.456 ± 0.056* | 0.741 ± 0.267* |

| Bolivia | 5 | 0.142 ± 0.034* | 0.107 ± 0.024* | 0.735 ± 0.383* |

| Group (%) | Correct individual rate (%) | Score (%) | ||||||

| Rate | Score | Rate total |

Score | Rate >80% |

Rate >95% |

Wrong | D (km) | |

| 1FG-Co | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 2FG-Is | 100 | 100 | 34.5 | 94.1 | 27.6 | 27.6 | 92.8 | 87 |

| 3FG-Ro | 100 | 100 | 30.5 | 90.2 | 30.5 | 16.7 | 69.1 | 134 |

| 4FG-Ma | 100 | 100 | 60.7 | 98.8 | 57.1 | 57.1 | 100 | 29 |

| 5BW-Ma | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.8 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 6BW-An | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 7BW-Já | 100 | 100 | 73.3 | 95.6 | 73.3 | 66.7 | 88.8 | 203 |

| 8BW-Jr | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.6 | 100 | 96.4 | 0 | 0 |

| 9BW-Xa | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.8 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 10BW-Cu | 100 | 100 | 100 | 98.7 | 96.3 | 92.6 | 0 | 0 |

| 11BE-Am | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 12BE-Av | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.8 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 13BE-Ta | 100 | 100 | 95.7 | 98.7 | 95.7 | 95.7 | 70.5 | 591 |

| 14BE-Ar | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.7 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 15BE-Te | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 16BE-Ca | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.8 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 17PN-Hu | 100 | 100 | 69.2 | 68 | 30.8 | 11.5 | 49.9 | 299 |

| 18PN-Ur | 100 | 100 | 70.4 | 63.0 | 25.9 | 11.1 | 47.6 | 211 |

| 19PN-Ma | 100 | 100 | 75 | 69.7 | 39.3 | 21.4 | 60 | 287 |

| 20PN-Ya | 100 | 100 | 89.3 | 64.6 | 35.7 | 14.3 | 45.7 | 174 |

| 21PN-Pr | 100 | 100 | 86.2 | 80.3 | 55.2 | 34.5 | 57.5 | 131 |

| 22PN-Ce | 100 | 100 | 81.8 | 59.3 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 50 | 155 |

| 23PN-He | 100 | 100 | 68 | 60.5 | 24 | 12 | 65.1 | 178 |

| 24PN-Je | 100 | 100 | 65.4 | 59.6 | 15.4 | 7.7 | 55 | 146 |

| 25PN-Sh | 100 | 100 | 88.9 | 66.4 | 29.6 | 7.4 | 47 | 237 |

| 26PS-Po | 100 | 100 | 72.4 | 79.8 | 41.4 | 13.8 | 49.7 | 236 |

| 27PS-Pa | 100 | 100 | 80 | 71.5 | 43.3 | 13.3 | 56.7 | 247 |

| 28PS-Di | 100 | 100 | 93.1 | 74.9 | 55.2 | 13.8 | 58.4 | 283 |

| 29PS-In | 100 | 100 | 45.5 | 70.8 | 36.4 | 18 | 53.5 | 208 |

| 30PS-Ma | 100 | 100 | 97 | 97.2 | 93.9 | 81.8 | 94.1 | 129 |

| 31PS-Ca | 100 | 100 | 93.3 | 97.1 | 93.3 | 80 | 76.7 | 147 |

| 32PS-Am | 100 | 100 | 96.7 | 97.7 | 93.3 | 93.3 | 45.5 | 270 |

| 33PS-Ta | 100 | 100 | 95.8 | 98.9 | 95.8 | 91.7 | 92.7 | 85 |

| 34Bo-Mb | 100 | 100 | 93.3 | 99.8 | 93.3 | 93.3 | 97.8 | 29 |

| 35Bo-De | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 36Bo-Vi | 100 | 100 | 100 | 97.1 | 100 | 83.3 | 0 | 0 |

| 37Bo-Ch | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 38Bo-Ma | 100 | 100 | 100 | 98.7 | 96.6 | 93.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Overall | 100 | 100 | 85.7 | 91.0 | 71.0 | 62.3 | 70.3 | 174 |

| F. Guiana | 100 | 100 | 48.8 | 98 | 46.3 | 46.3 | 96.9 | - |

| Brazil | 100 | 100 | 97.6 | 99.2 | 97.6 | 97.6 | 87.5 | - |

| Peru | 100 | 100 | 82.3 | 74.9 | 49.2 | 31.9 | 53.1 | - |

| Bolivia | 100 | 100 | 98.6 | 98 | 94.5 | 91.8 | 68.6 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).