Submitted:

06 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

As global populations age, supporting older adults to age in place—remaining in their homes and communities—emerges as a critical challenge. This study investigates how interior architectural design can integrate human-centered, biophilic, and technology-driven principles with sustainable strategies to enhance the autonomy, safety, and well-being of older adults. Employing a multi-phase methodology, the research synthesizes literature on aging, interior architecture, and technology to establish a comprehensive framework. This framework emphasizes user participation, nature-inspired design, assistive technologies, and adaptable spatial planning. Key findings reveal actionable strategies, such as integrating biophilic elements like daylighting and greenery, employing user-friendly smart technologies, and incorporating universal design features like adjustable countertops and slip-resistant flooring. The proposed framework aligns design interventions with the physical, cognitive, and emotional needs of older adults, promoting environments that foster independence and dignity. Ultimately, the study underscores the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in creating adaptable, sustainable, and empowering living spaces that enhance quality of life for aging populations.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Significance

1.2. Aim and Scope of the Paper

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

- Literature Review: This phase involved a broad scan of peer-reviewed articles, design case studies, and gerontological reports. The review aimed to inform an understanding of the challenges faced by older adults in living environments, as well as emerging solutions in architecture, biophilic design, and technology.

- Conceptual Framework Development: Insights from the literature review were synthesized to formulate an integrative framework. This framework emphasizes human-centered strategies (e.g., participatory design), biophilic principles (e.g., maximizing natural light and introducing greenery), and user-friendly technologies (e.g., ambient assisted living devices and voice-activated systems).

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Literature Review

3.1.1. Aging in Place: Concepts and Gerontological Foundations

3.1.2. Architectural and Interior Design Challenges

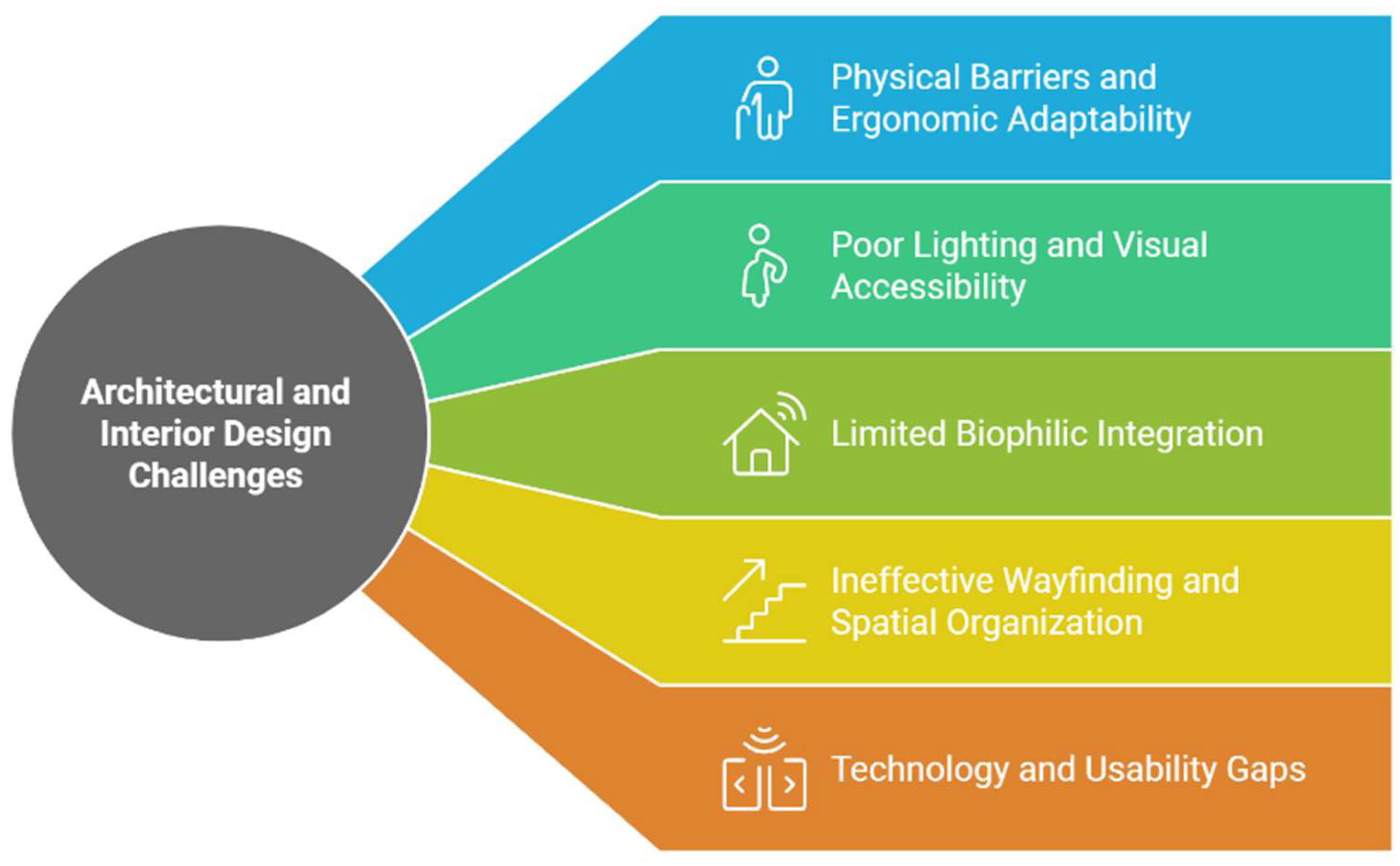

- Physical Barriers and Lack of Ergonomic Adaptability: Interiors frequently include narrow corridors, steep steps, or limited turning radius, rendering mobility aids (walkers, wheelchairs) difficult to maneuver (Engineer et al., 2018; Shu & Liu, 2022). High countertops, fixed cabinetry, and standard-height fixtures also limit older adults’ ability to carry out basic tasks (Wang, Lin, & Huang, 2022). Bathrooms without accessible features—such as grab bars or anti-slip flooring—remain a leading cause of falls (Romli et al., 2016; Moreland B. et al., 2020).

- Poor Lighting and Reduced Visual Accessibility: Natural and artificial lighting is often insufficient or poorly calibrated for age-related visual changes (Fox, Stathi, McKenna, & Davis, 2007; Bennetts, Martins, & van Hoof, 2020). Older adults may struggle with glare or inadequate contrast in floor edges, leading to disorientation or falls (Engineer et al., 2018; Moreland B. et al., 2020). Research suggests that circadian-friendly lighting—dynamic systems that align with natural rhythms—can improve mood, sleep patterns, and mental clarity (Sander, Markvart, Kessel, Argyraki, & Johnsen, 2015).

- Limited Biophilic Integration: While biophilic design can reduce stress and support cognitive functioning through greater exposure to nature and daylight, many homes lack strong indoor-outdoor connections (Manca, Cerina, & Fornara, 2019; Van Hoof, Bennetts, Hansen, Kazak, & Soebarto, 2019). Narrow windows, minimal greenery, and the absence of transitional spaces like balconies or patios can deprive seniors of opportunities for restorative natural experiences (Peng & Maing, 2021).

- Ineffective Wayfinding and Spatial Organization: Unclear room hierarchies, repetitive corridors, and complex layouts hamper older adults—particularly those with cognitive impairments (Ahmed et al., 2023). A lack of visual or tactile cues may compound confusion and prompt reliance on caregivers for navigation (Das et al., 2022). Failing to design with cognitive accessibility in mind can undermine autonomy, raise stress, and increase the risk of accidents (Demirkan & Olguntuerk, 2013).

- Technology and Usability Gaps: Ambient assisted living devices, such as fall-detection sensors or smart home controllers, are frequently installed without accounting for older adults’ preferences or limitations (Lee, Gu, & Kwon, 2020). Complicated user interfaces, poorly placed sensors, or opaque privacy policies can deter adoption (Borelli et al., 2019; Fournier, H. et al., 2021). Integrating user-friendly interfaces (touchscreens with larger fonts, voice-activated assistants) remains an underexplored dimension of interior architecture (Engineer et al., 2018).

3.1.3. Existing Approaches

- Universal (or Inclusive) Design: Universal design, sometimes termed “design for all,” seeks to accommodate a wide range of users by incorporating flexibility, simplicity, and intuitive use from the outset (Connell, B. et al., 1997; Demirkan & Olguntuerk, 2013; Sandholdt, C. et al., 2020). Evidence indicates that universal design features—e.g., lever-type handles, low-threshold doors, and adjustable work surfaces—enhance safety, comfort, and independence for older adults (Ling et al., 2023). Yet researchers highlight the need for ongoing refinement: a strictly code-based or prescriptive approach may still ignore nuanced cultural and personal preferences (Tsuchiya-Ito & Iwarsson, 2019; Zhuan, S., 2023).

- Biophilic and Sustainable Interior Strategies: Biophilic integration brings elements of nature—daylight, greenery, natural materials—into indoor living spaces (Manca et al., 2019; Fox et al., 2007). Studies show that exposure to nature can lower stress, support mental health, and encourage physical activity—especially valuable for older adults (Van Hoof et al., 2019). Sustainable design approaches, such as maximizing daylighting or reducing VOC-emitting materials, further improve indoor air quality and occupant health (Park & Kim, 2018; Ahmed et al., 2023). However, ensuring these interventions are user-friendly and customizable is critical for long-term acceptance (Mnea & Zairul, 2023).

3.1.4. Gaps and the Need for an Integrated Framework

3.2. Findings and Recommendations

3.2.1. Spatial Design Challenges

3.2.2. Proposed Solutions

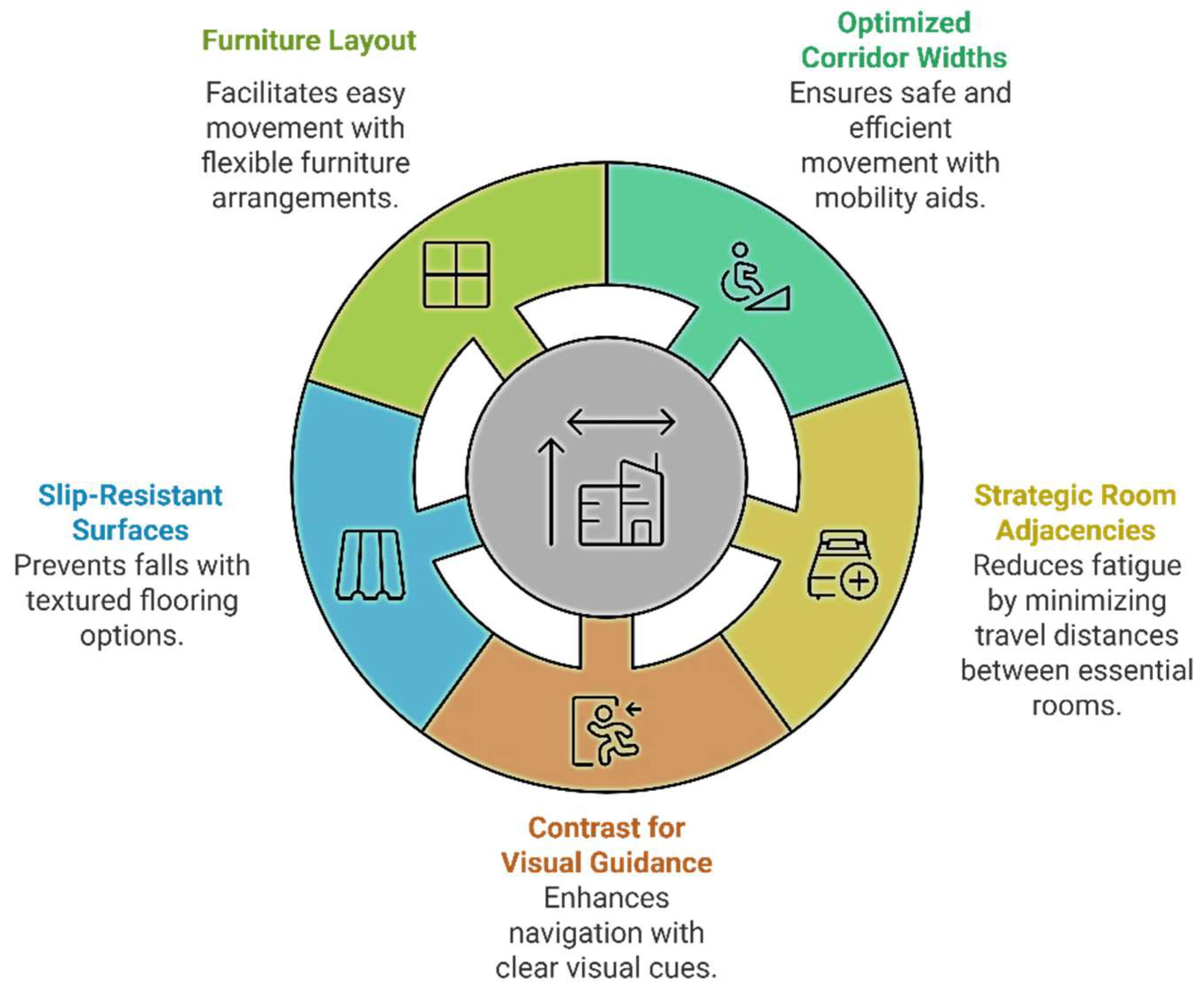

- Wayfinding: Effective wayfinding strategies are crucial for older adults, particularly in complex environments. Clear signage and visual cues can significantly enhance navigation. Large-font signs with pictograms and contrasting colors, placed at strategic decision points, can improve clarity and reduce confusion (Ahmed et al., 2023). Additionally, color-coded pathways, where different hues are assigned to corridors leading to specific areas, can further aid in orientation (Das et al., 2022). Tactile flooring, such as textured strips or raised patterns, can help older adults identify room thresholds through touch, improving spatial awareness (Demirkan & Olguntuerk, 2013). Finally, intuitive layouts with direct sightlines to communal areas, reduced blind corners, and the clustering of related functions can further simplify navigation (Engineer et al., 2018).

- Lighting & Ergonomics: Lighting and ergonomics play an essential role in the well-being of older adults. Dynamic circadian lighting systems that shift color temperature throughout the day can promote healthier sleep-wake cycles and improve overall health (Sander et al., 2015). To enhance safety, slip-resistant flooring with raised textures or coatings should be prioritized in high-risk zones such as bathrooms, kitchens, and entryways (Romli et al., 2016). Adjustable countertops and cabinets, which allow older adults to customize heights according to their changing mobility and posture, are another vital ergonomic solution (Wang et al., 2022). Additionally, replacing doorknobs with lever handles, expanding hallway widths to at least 1.5 meters, and ensuring low-threshold or zero-step entries can further improve accessibility (Ahmed et al., 2023).

- Biophilic Integration & Indoor-Outdoor Transitions: Integrating biophilic design and facilitating smooth transitions between indoor and outdoor spaces can significantly enhance the environment for older adults. Large windows and skylights can increase natural light penetration and reduce dark spots, mitigating symptoms of depression (Manca et al., 2019). Easy-access gardens, providing direct, level access to courtyards or balconies with raised planters, encourage moderate physical activity and connection to nature (Peng & Maing, 2021). The incorporation of green walls and natural materials, such as indoor vegetation, wooden surfaces, and water features, can further boost cognitive engagement and provide stress relief (Fox et al., 2007).

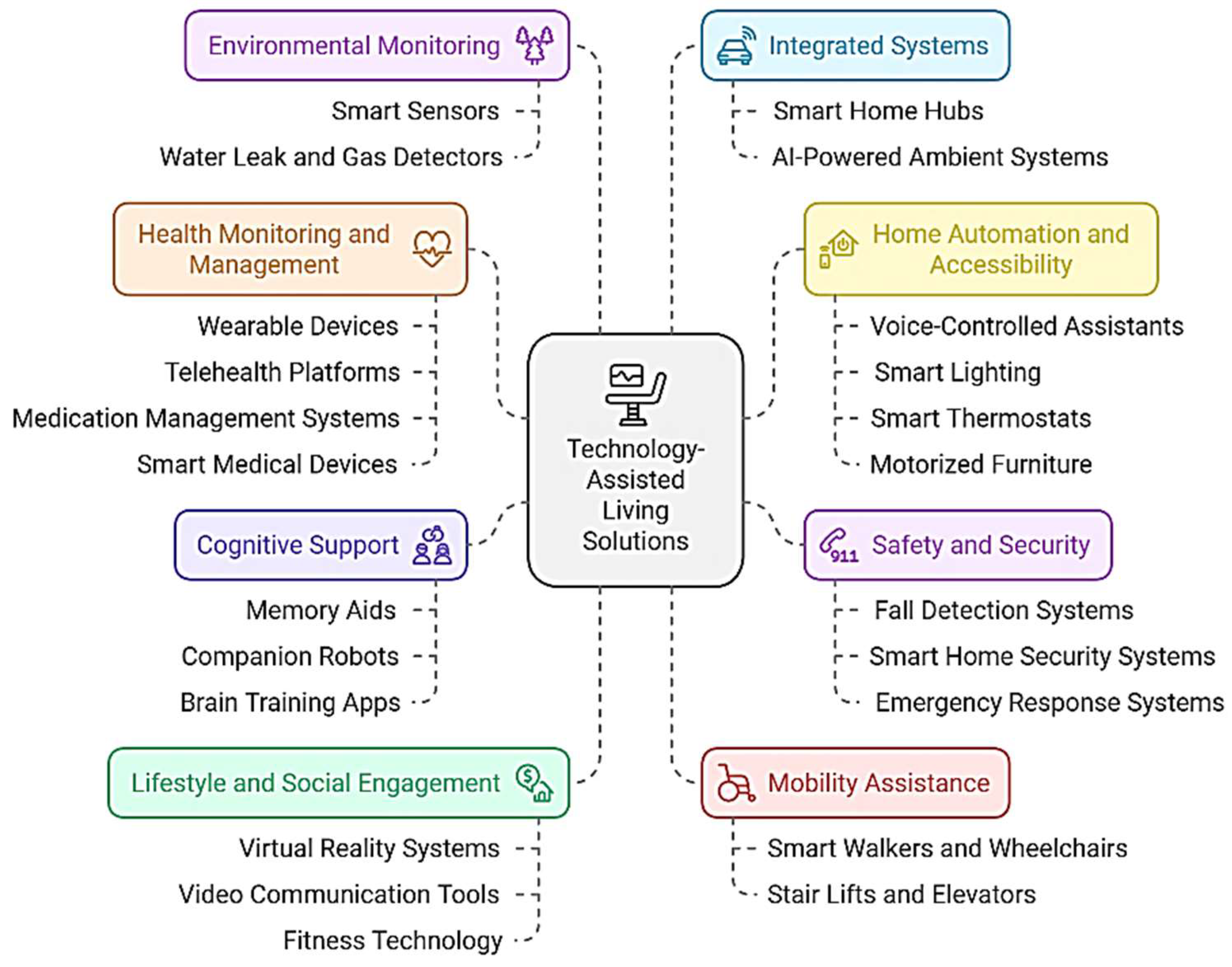

- User-Friendly Technology: User-friendly technology can significantly enhance the independence and safety of older adults. Voice-activated controls, which reduce the need for manual dexterity, can be integrated into systems for lighting, HVAC, or emergency calls, making these systems more accessible (Jo, Ma, & Cha, 2021). Fall-detection sensors, strategically placed in high-risk areas like bathrooms and bed areas, can help prevent accidents, provided they have low rates of false alarms (Borelli et al., 2019). Accessible interfaces with large buttons, tactile feedback, and contrast-rich screens are essential for accommodating visual or motor impairments (Shu & Liu, 2022). Interfaces designed to display short, simple, and low-complexity information or sentences can enhance accessibility for older adults with cognitive impairments. Interfaces should prioritize clear, easily readable text, intuitive navigation, and minimal distractions to support ease of use and comprehension for older adults with cognitive impairment. (Chen, L., & Liu, Y., 2017; Chen, L., & Liu, Y., 2022; Castilla, D. et al., 2020). Finally, the strategic placement of devices, such as sensors near entry points or seating areas, ensures maximum reliability and ease of use (Lee et al., 2020).

3.2.3. Evidence-Based Benefits

4. Discussion

4.1. Conceptual Framework

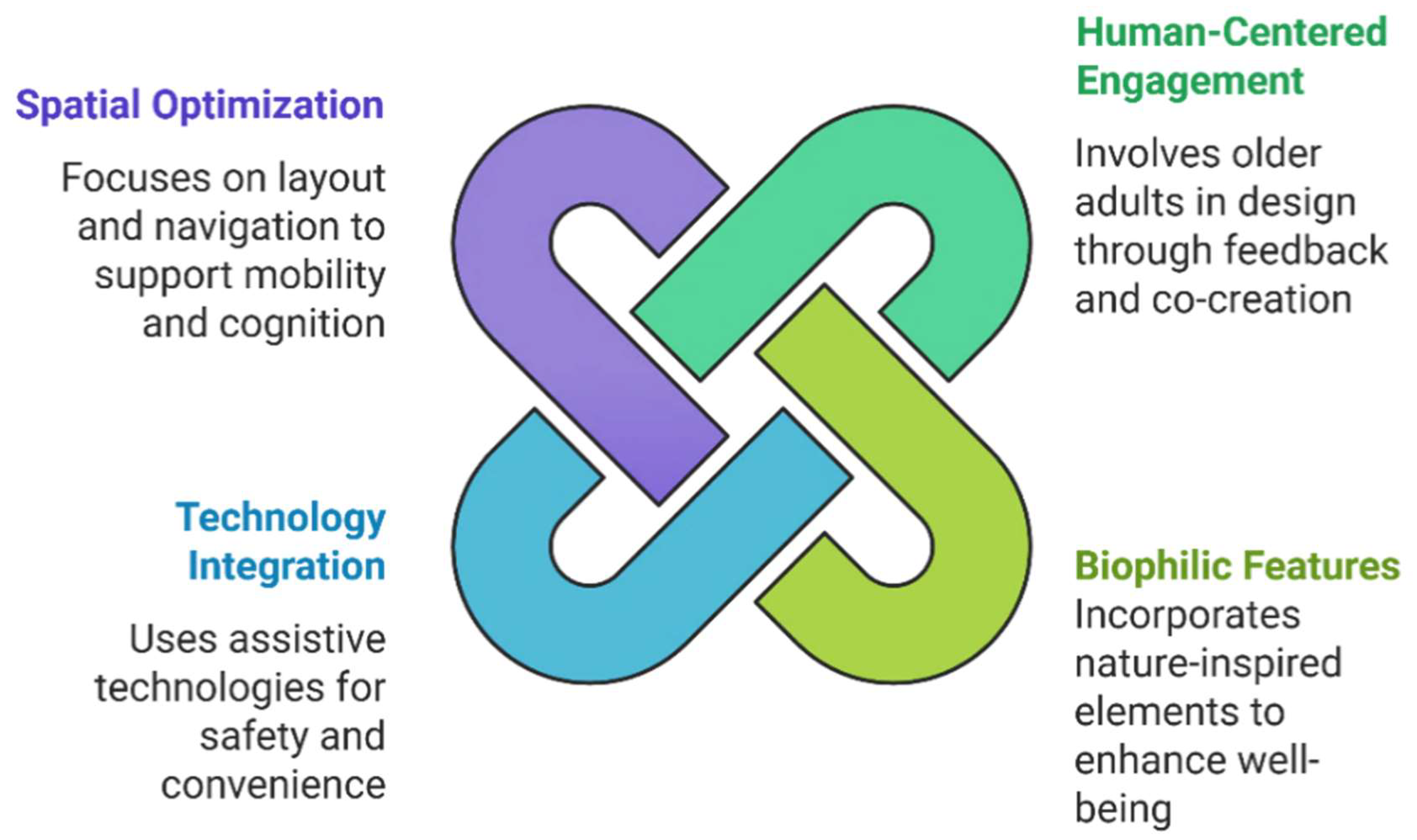

- Framework Components:

- Human-Centered Engagement:

- Biophilic and Sustainable Features:

- Technology Integration

- Spatial Factors

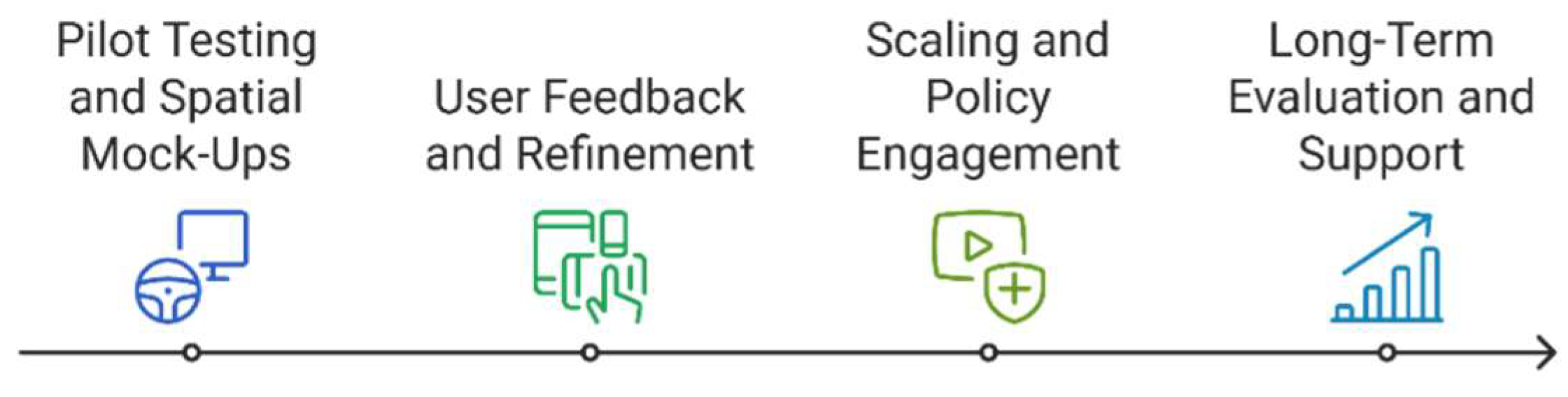

4.2. Implementation Pathway

4.3. Barriers and Limitations

4.4. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

CASP Checklist Table

| Ref | Clear Research Aim? | Appropriate Methodology? | Valid Results? | Credible Authors/Source? | Relevant to Topic? | Overall CASP Rating | Notes/Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High | Presents a framework bridging architecture & gerontology. Well-aligned with aging-in-place. |

| 2 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (IEEE journal) | Yes | High | Robust method for detecting MCI in older adults at home. Strong technical approach. |

| 3 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Journal) | Yes | High | Clustering home activities for MCI detection. Novel approach, well-grounded results. |

| 4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (IJERPH) | Yes | High | Explores thermal comfort of older adults in housing. Good sample and peer-reviewed. |

| 6 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Sensors journal) | Yes | High | IoT solution (HABITAT) for independent older adults. Peer-reviewed. |

| 7 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (IJERPH) | Yes | High | Usability study for ICTs in mild cognitive impairment. Rigorous approach. |

| 8 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (IJERPH) | Yes | High | Interface design for cognitively impaired older adults. Relevant. |

| 9 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Procedia CIRP) | Yes | High | Addresses affordances, dementia-friendly design. Peer-reviewed conference proceedings. |

| 10 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Center for Universal Design) | Yes | High | Foundational universal design principles from a credible source. |

| 12 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Architectural Science Review) | Yes | High | Presents a design-for-all approach to guide independent living. Well-documented. |

| 13 | Yes | Yes | Partially | Yes | Yes | Moderate | Discusses user-centered design for self-management. Some specifics lacking, but relevant. |

| 14 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Gerontology journal) | Yes | High | Review on interior design strategies to mitigate age-related deficits. |

| 15 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Housing Policy Debate) | Yes | High | Climate change and aging. Peer-reviewed. Expands context of older adults’ well-being. |

| 16 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Springer LNCS) | Yes | High | Smart tech and IoT for aging in place. Well-grounded. |

| 17 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Eur J Appl Physiol) | Yes | High | Explores physical activity/well-being for older adults. Somewhat indirect but relevant to supportive environments. |

| 18 | Yes | Partially | Yes | Yes (AJOT) | Yes | Moderate | Observational study about housing accessibility upon relocation. Data is valid. |

| 19 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Sensors journal) | Yes | High | IoT-based integrated smart-home system for older adults. Useful and credible. |

| 20 | Yes | Theoretical Model | Yes (conceptually) | Yes (Gerontology classic) | Yes | High | Classic theoretical model (person-environment fit). Historical but fundamental. |

| 21 | Yes | Theoretical Model | Yes (conceptually) | Yes (APA) | Yes | High | Foundational ecology/aging model. Very relevant. |

| 22 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Front. Psychol.) | Yes | High | Critical review of smart residential environments. In-depth. |

| 23 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (IJERPH) | Yes | High | Human-centric approach to design criteria in Taiwan for aging in place. |

| 24 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Social Psychological Bulletin) | Yes | High | Compares high- vs. low-humanized facilities, relevant to design interventions. |

| 25 | Yes | Partially (Self-report) | Yes | Yes (Can Geriatr J) | Yes | Moderate | Focus on older adults with self-reported cognitive decline. Data is self-reported, but valid. |

| 26 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Social Policy & Admin) | Yes | High | Ageing in place policy and social perspective. Widely cited. |

| 27 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Energy Policy) | Yes | High | Examines energy efficiency in older citizens’ housing. Relevant to design & environment. |

| 28 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Buildings) | Yes | High | Thematic review on interior design for elderly independence. Excellent fit for your study. |

| 29 | Yes | Partially (Surveillance Data) | Yes | Yes (CDC MMWR) | Yes | Moderate | Large-scale epidemiological data on nonfatal falls. Indirect, but relevant to design for fall prevention. |

| 30 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Journal Eng. Sciences) | Yes | High | Focus on elderly-friendly home environments in Egypt. Matches your design scope. |

| 31 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Energies) | Yes | High | Green remodeling for the elderly. Peer-reviewed. |

| 32 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Cities) | Yes | High | Age-friendly neighborhood design in HK. Good empirical work. |

| 33 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (JMIR) | Yes | High | Systematic review of digital biomarker tech for MCI. Highly relevant to home-based monitoring. |

| 34 | Yes | Partially | Yes | Yes (Delaware J. Public Health) | Yes | Moderate | Brief overview of Aging in Place in a specific region. Good policy insight. |

| 35 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (BMJ Open) | Yes | High | HOME FAST tool feasibility for older Malaysians. Robust pilot study. |

| 36 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Chronobiol Int.) | Yes | High | Explores circadian lighting effects on older adults. Strong methodological detail. |

| 37 | Yes | Yes | Partially | Yes (IJERPH) | Yes | Moderate | Addresses human-centered design in health innovation. Good conceptual coverage. |

| 38 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Comp. Intell. Neurosci.) | Yes | High | AI computing for universal design in healthy housing. Technically solid. |

| 39 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (Internet of Things) | Yes | High | Explores IoT-based solutions for the elderly. Peer-reviewed, rigorous. |

| 40 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (IFIP AI & Innovations) | Yes | High | Smart-home IoT for older adults. Good synergy with your framework. |

| 41 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (J Cross-Cultural Gerontol.) | Yes | High | Comparison of environmental challenges in Japan & Sweden. Peer-reviewed. |

| 42 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (IJERPH) | Yes | High | Explores living environment/thermal behavior among older adults in Australia. |

| 43 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (AVI Conf. Proc.) | Yes | High | Focus on empowerment goals in elderly-centered interaction design. |

| 44 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (IJERPH) | Yes | High | Kitchen layout for aging-friendly environments using space syntax. |

| 46 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High | Provides humanization-based strategies for aging-friendly home spaces. |

Appendix B

Appendix B1. Coding of Challenges

| Code | Description/Key Points | Relevant References | Broader Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Narrow Corridors and Doorways | Corridors/doorways too tight for wheelchairs or walkers, creating fall risks and restricting free movement. | [1,14,18,28] | Physical Barriers & Lack of Ergonomic Adaptability |

| High Fixtures & Limited Reach | Kitchen/bathroom fixtures are too high, forcing older adults to stretch or climb. | [18,29,34,35,44] | Physical Barriers & Lack of Ergonomic Adaptability |

| Poor Lighting & Glare | Inadequate or poorly calibrated lighting for age-related vision changes; can cause falls, depression, disorientation. | [4,14,17,24,29,36] | Poor Lighting & Reduced Visual Accessibility |

| Lack of Natural Light/Biophilia | Insufficient daylight, minimal greenery, limited windows/balconies, depriving older adults of beneficial nature experiences that reduce stress and boost cognition. | [15,17,24,31,32,42] | Limited Biophilic Integration |

| Spatial Complexity & Wayfinding | Repetitive layouts, few visual cues or landmarks, and unclear circulation hamper navigation—especially for mild cognitive impairments. | [1,12,28,30] | Ineffective Wayfinding & Spatial Organization |

| Limited Cognitive Accessibility | Spaces or layouts not designed for mild cognitive impairment (lack of color contrasts, memory cues, or clarity). | [2,3,12,13,25] | Ineffective Wayfinding & Spatial Organization |

| Complicated Smart-Home Interfaces | Interfaces (sensors, apps, panels) may be unintuitive, with small text or confusing workflows, making it hard for older adults to engage with IoT solutions. | [6,7,8,9,14,16,22,23] | Technology & Usability Gaps |

| Privacy & Adoption Barriers | Continuous monitoring devices may feel intrusive; fear of data misuse or cultural resistance to unfamiliar tech. | [1,19,22,32,33,38,40] | Technology & Usability Gaps |

| Cost & Funding Gaps | Financial limitations prevent homeowners from retrofitting or adopting new technologies; also a lack of affordable solutions for older adults. | [14,26,27,39,40] | Socioeconomic & Policy-Related Barriers |

| Inadequate Training & Workforce Skills | Insufficient professional training in “design for aging,” plus older adults who lack guidance on new devices or universal design features. | [1,10,12,37,40] | Socioeconomic & Policy-Related Barriers |

| Environmental Press vs. Competence | Mismatch between older adults’ functional abilities and the demands (press) of the environment can reduce autonomy and well-being. | [13,14,20,21] | Mismatch in Person–Environment Fit |

Appendix B2. Coding of Solutions

| Code | Description/Key Points | Relevant References | Broader Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Universal/Inclusive Design | Designing environments that accommodate all abilities from the start—lever handles, zero-threshold doors, adjustable counters, etc. | [10,12,23,37,41,46] | Universal & Human-Centered Design |

| Co-Creation & Participatory Design | Involving older adults in design decisions via focus groups, prototypes, user feedback loops, ensuring interventions match actual needs and preferences. | [1,13,28,43] | Universal & Human-Centered Design |

| Adjustable Fixtures & Ergonomics | Ergonomic improvements (height-adjustable sinks, slip-resistant floors, handheld showerheads, etc.) that reduce fall risk and accommodate varied mobility. | [1,28,29,35,44] | Physical Adaptation |

| Enhanced Lighting (Dynamic/Circadian) | Systems that automatically adjust brightness/color temperature throughout the day to support circadian rhythms and improve older adults’ safety and comfort. | [4,14,17,24,34,36,38] | Physical Adaptation |

| Biophilic Design Strategies | Incorporating natural elements (greenery, daylight, natural materials) and indoor-outdoor connections to reduce stress, enhance cognition, and improve well-being. | [15,17,24,28,31,32,42] | Biophilic Integration & Sustainability |

| Sustainable Material Selection | Using low-VOC paints, recycled materials, LED lighting, and energy-efficient systems to promote environmental health and occupant well-being, while reducing operational costs. | [1,26,27,30,31] | Biophilic Integration & Sustainability |

| Ambient Assisted Living (AAL) & IoT | Sensor-based solutions (fall detection, motion sensors, wearable devices) and smart-home systems for remote health monitoring, safety alerts, and daily convenience. | [6,7,8,9,19,22,33,38,39,40] | Technology Integration |

| User-Friendly Interfaces | Large fonts, intuitive icons, voice controls, minimal complexity, plus training to help older adults and caregivers comfortably adopt new technologies. | [2,3,8,9,14,19,23,32] | Technology Integration |

| Wayfinding Enhancements | Clear signage (large fonts, contrasting colors), tactile cues, color zoning, intuitive layouts to aid navigation (especially for mild cognitive impairment). | [1,12,25,28,30] | Spatial Organization & Wayfinding |

| Policy & Funding Incentives | Grants, tax credits, or updated building codes that encourage universal design features, retrofitting older homes, or subsidizing smart-tech installation. | [1,10,26,27,30,32] | Implementation & Policy |

| Multidisciplinary Collaboration | Collaboration among architects, gerontologists, occupational therapists, engineers, etc. to ensure age-friendly designs meet physical, cognitive, and emotional needs. | [1,13,14,15,20,21,38,43] | Implementation & Policy |

References

- Ahmed, M.N.; El Shair, I.H.; Taher, E.; Zyada, F. A Conceptional Framework for Integration of Architecture and Gerontology to Create Elderly-Friendly Home Environments. J. Eng. Sci. 2023, 51, 468–500. [CrossRef]

- Akl, A.; Snoek, J.; Mihailidis, A. Unobtrusive Detection of Mild Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults Through Home Monitoring. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2017, 21, 339–348. [CrossRef]

- Akl, A.; Chikhaoui, B.; Mattek, N.; Kaye, J.; Austin, D.; Mihailidis, A. Clustering Home Activity Distributions for Automatic Detection of Mild Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults. J. Ambient Intell. Smart Environ. 2016, 8, 437–451. [CrossRef]

- Bennetts, H.; Arakawa Martins, L.; van Hoof, J.; Soebarto, V. Thermal Personalities of Older People in South Australia: A Personas-Based Approach to Develop Thermal Comfort Guidelines. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8402. [CrossRef]

- Binette, J. Home and Community Preferences Survey. AARP Research 2021. [CrossRef]

- Borelli, E.; Paolini, G.; Antoniazzi, F.; Barbiroli, M.; Benassi, F.; Chesani, F.; Chiari, L.; Fantini, M.; Fuschini, F.; Galassi, A.; Giacobone, G.A.; Imbesi, S.; Licciardello, M.; Loreti, D.; Marchi, M.; Masotti, D.; Mello, P.; Mellone, S.; Mincolelli, G.; Costanzo, A. HABITAT: An IoT Solution for Independent Elderly. Sensors 2019, 19, 1258. [CrossRef]

- Castilla, D.; Suso-Ribera, C.; Zaragoza, I.; Garcia-Palacios, A.; Botella, C. Designing ICTs for Users with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Usability Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5153. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, Y. Interface Design for Products for Users with Advanced Age and Cognitive Impairment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, Y. Affordance and Intuitive Interface Design for Elder Users with Dementia. Procedia CIRP 2017, 60, 470–475. [CrossRef]

- Connell, B.R.; Jones, M.; Mace, R.; Mueller, J.; Mullick, A.; Ostroff, E.; Sanford, J.; Steinfeld, E.; Story, M.; Vanderheiden, G. The Principles of Universal Design (Version 2.0). The Center for Universal Design, N.C. State University 1997.

- Das, M.B.; Arai, Y.; Chapman, T.B.; Jain, V. Silver Hues: Building Age-Ready Cities. World Bank, Washington, DC 2022. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/37259.

- Demirkan, H.; Olguntürk, N. A Priority-Based ‘Design for All’ Approach to Guide Home Designers for Independent Living. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2013, 57, 90–104. [CrossRef]

- D'haeseleer, I.; Gielis, K.; Abeele, V. Human-Centered Design of Self-Management Health Systems with and for Older Adults: Challenges and Practical Guidelines. 2021, 90–102. [CrossRef]

- Engineer, A.; Sternberg, E.M.; Najafi, B. Designing Interiors to Mitigate Physical and Cognitive Deficits Related to Aging and to Promote Longevity in Older Adults: A Review. Gerontology 2018, 64, 612–622. [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, A.; Molinsky, J. Climate Change, Aging, and Well-Being: How Residential Setting Matters. Housing Policy Debate 2023, 33, 1029–1054. [CrossRef]

- Fournier, H.; Kondratova, I.; Katsuragawa, K. Smart technologies and the Internet of Things designed for aging in place. In Moallem, A., Ed.; HCI for Cybersecurity, Privacy and Trust. HCII 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 12788. Springer, Cham, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Fox, K.; Stathi, A.; McKenna, J.; Davis, M. G. Physical activity and mental well-being in older people participating in the Better Ageing Project. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007, 100, 591-602. [CrossRef]

- Granbom, M.; Slaug, B.; Löfqvist, C.; Oswald, F.; Iwarsson, S. Community relocation in very old age: Changes in housing accessibility. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2016, 70, 7002270020p1–7002270020p9. [CrossRef]

- Jo, T. H.; Ma, J. H.; Cha, S. H. Elderly perception on the Internet of Things-based integrated smart-home system. Sensors 2021, 21, 1284. [CrossRef]

- Kahana, E. A congruence model of person-environment interaction. In Aging and the Environment: Theoretical Approaches; 1982; pp 97-121.

- Lawton, M. P.; Nahemow, L. Ecology and the aging process. In Eisdorfer, C.; Lawton, M. P., Eds.; The Psychology of Adult Development and Aging; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, 1973; pp 619–674. [CrossRef]

- Lee, L. N.; Kim, M. J. A critical review of smart residential environments for older adults with a focus on pleasurable experience. Front. Psychol. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ling, T.-Y.; Lu, H.-T.; Kao, Y.-P.; Chien, S.-C.; Chen, H.-C.; Lin, L.-F. Understanding the meaningful places for aging-in-place: A human-centric approach toward inter-domain design criteria consideration in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1373. [CrossRef]

- Manca, S.; Cerina, V.; Fornara, F. Residential satisfaction, psychological well-being, and perceived environmental qualities in high- vs. low-humanized residential facilities for the elderly. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2019, 14, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Mayo, C.; Kenny, R.; Scarapicchia, V.; Ohlhauser, L.; Syme, R.; Gawryluk, J. Aging in place: Challenges of older adults with self-reported cognitive decline. Can. Geriatr. J. 2021, 24, 138-143. [CrossRef]

- Means, R. Safe as houses? Ageing in place and vulnerable older people in the UK. Soc. Policy Adm. 2007, 41, 65–85. [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.; Vine, D.; Amin, Z. M. Energy efficiency of housing for older citizens: Does it matter? Energy Policy 2017, 101, 216-224. [CrossRef]

- Mnea, A.; Zairul, M. Evaluating the impact of housing interior design on elderly independence and activity: A thematic review. Buildings 2023, 13, 1099. [CrossRef]

- Moreland, B.; Kakara, R.; Henry, A. Trends in nonfatal falls and fall-related injuries among adults aged ≥65 years—United States, 2012–2018. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 875–881. [CrossRef]

- Nabil, M. A.; Hassan, N. M.; Ezzat, M. Exploring elderly challenges, needs, and adaptive strategies to promote aging in place. J. Eng. Sci. Appl. 2023, 51, 260-286. [CrossRef]

- Park, S. J., & Kim, M. J. A Framework for Green Remodeling Enabling Energy Efficiency and Healthy Living for the Elderly. Energies 2018, 11, 2031. [CrossRef]

- Peng, S., & Maing, M. Influential factors of age-friendly neighborhood open space under high-density high-rise housing context in hot weather: A case study of public housing in Hong Kong. Cities 2021, 115, 103231. [CrossRef]

- Piau, A., Wild, K., Mattek, N., & Kaye, J. Current State of Digital Biomarker Technologies for Real-Life, Home-Based Monitoring of Cognitive Function for Mild Cognitive Impairment to Mild Alzheimer Disease and Implications for Clinical Care: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2019, 21. [CrossRef]

- Ratnayake, M., Lukas, S., Brathwaite, S., Neave, J., & Henry, H. Aging in Place. Delaware Journal of Public Health 2022, 8, 28–31. [CrossRef]

- Romli, M. H., Mackenzie, L., Lovarini, M., & Tan, M. P. Pilot study to investigate the feasibility of the Home Falls and Accidents Screening Tool (HOME FAST) to identify older Malaysian people at risk of falls. BMJ open 2016, 6, e012048. [CrossRef]

- Sander, B., Markvart, J., Kessel, L., Argyraki, A., & Johnsen, K. Can sleep quality and wellbeing be improved by changing the indoor lighting in the homes of healthy, elderly citizens?. Chronobiology international 2015, 32, 1049–1060. [CrossRef]

- Sandholdt, C., Cunningham, J., Westendorp, R., & Kristiansen, M. Towards inclusive healthcare delivery: Potentials and challenges of human-centred design in health innovation processes to increase healthy aging. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17. [CrossRef]

- Shu, Q., & Liu, H. Application of Artificial Intelligence Computing in the Universal Design of Aging and Healthy Housing. Computational intelligence and neuroscience 2022, 2022, 4576397. [CrossRef]

- Sokullu, R., Akkaş, M., & Demir, E. IoT supported smart home for the elderly. Internet Things 2020. [CrossRef]

- Stavrotheodoros, S., Kaklanis, N., Votis, K., Tzovaras, D. A Smart-Home IoT Infrastructure for the Support of Independent Living of Older Adults. In: Iliadis, L., Maglogiannis, I., Plagianakos, V. (eds) Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations. AIAI 2018. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, vol 520. Springer, Cham 2018. [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya-Ito, R., Iwarsson, S., & Slaug, B. Environmental Challenges in the Home for Ageing Societies: a Comparison of Sweden and Japan. Journal of cross-cultural gerontology 2019, 34, 265–289. [CrossRef]

- van Hoof, J., Bennetts, H., Hansen, A., Kazak, J. K., & Soebarto, V. The Living Environment and Thermal Behaviours of Older South Australians: A Multi-Focus Group Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2019, 16, 935. [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, G., & Sebillo, M. The importance of empowerment goals in elderly-centered interaction design. Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces 2018. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Lin, D., & Huang, Z. Research on the Aging-Friendly Kitchen Based on Space Syntax Theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 5393. [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization). World report on ageing and health. World Health Organization 2015. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/186463.

- Zhuan, S. Research on Aging-friendly Home Space Design Based on Humanization. Academic Journal of Architecture and Geotechnical Engineering 2023. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).