1. Introduction

Extra Care Housing (ECH) represents a model of housing for older adults that bridges independent living and residential care, offering older adults’ autonomy alongside access to care services [

1]. In contrast to nursing homes which offer institutionalized, 24/7 medical care, ECH focuses on resident autonomy, community integration, and flexible care delivery [

2,

3]. The model has become increasingly common in the UK as a sustainable alternative to conventional care homes, reflecting the policy objective of ‘aging in place’. The design of ECH environment is under-researched, especially the architects’ point of view who design these spaces. This research fills the gap by investigating how UK architects view their role in designing ECH environment to enhance older residents’ quality of life (QoL).

ECH encompasses a range of housing options for older people including independent living and assisted living. These models all share common goals such as promoting independence, reducing social isolation, providing an alternative to institutional care, offering a lifelong home, and improving residents’ QoL [

1]. Unlike nursing homes, which provide intensive care, ECH fosters independent living within a supportive community. As outlined in

Table 1, private apartments, communal areas and access to care service on an individual basis are the main features of ECH. The main principle of ECH is to enable residents’ independence and sense of home.

Ageing in place is policy-oriented in the UK and other Global North nations as a way of putting first helping older people to remain where they are, in their homes and local communities. The policy is founded on the principle that older adults experience greater well-being when they remain in environments where they feel comfortable and are familiar with their surroundings [

4]. Nevertheless, there are criticisms that identify access gaps, particularly to and from lower-income households, and the risk of social isolation where available support services fall short [

5]. For example, Xia et al. [

6] found in a recent study that ageing in place promotes independence but often does nothing to meet the complex needs of older individuals with chronic health conditions. Such problems underscore the requirement for judicious architectural planning within ECH facilities.

The design of ECH in the UK is a critical area of research, particularly as it relates to the perspectives of architects and its impact on residents’ quality of life. This article synthesizes findings from various studies that explore the intersection of architectural design, resident experiences, and the overall effectiveness of ECH in promoting well-being among older adults.

Care needs and health requirements of adults increase and intensify as one ages. Abramson and Andersson [

7] reported that the biggest changes occur at the age bracket of 75 to 84, with the older people likely having more than one health problem. In the United Kingdom, men at 65 years should have 10 out of 19 years of their remaining life disability free, and women at 65 years should have 10 out of 21 years disability free [

8]. These statistics bring into perspective how one should design independent as well as care supportive environments. Recent research by Kingston et al. [

9] identifies growing numbers of multi-morbidity in older age and the demand for adaptable housing supply that will suit evolving health requirements.

Empirical data shows that environmental design elements like daylighting, accessibility, and social space, affect inhabitants’ health and sense of autonomy [

10]. According to Tang et al. [

11], competent architectural planning may improve relatedness, autonomy, and competence. For instance, accessible outdoor areas and sensory-engaging features like color contrast and gardens encourage both cognitive and physical stimulation [

12,

13]. More recent research by Jung et al. [

14] likewise focused on evidence-based design, emphasizing the need to balance autonomy and safety in order to maximize ECH settings.

According to National Academies of Sciences [

15], socialization is crucial for preventing loneliness among older adults. The possibility of social interaction and community participation is enhanced by designated common areas, such as gardens and lounges [

17]. Although metropolitan locations offer better access to nearby amenities at the cost of higher prices, the location of ECH facilities is also a crucial factor. According to 2023 research by Trust for America’s Health, rural residents in ECH facilities have trouble getting access to social services and healthcare, hence location-inclusive design techniques are necessary [

17].

The sense of place, and home and belonging, is critical to the emotional well-being of residents [

18]. This can be promoted by architects through design elements that enable personalization, like adjustable shelving or modular furniture. The statement, “Residents need to feel like they’re in their own home, not an institution” [

19], is a direct quotation from a study that emphasizes the importance of creating a homelike environment in residential care settings to enhance the well-being and quality of life of older adults. The significance of cultural and emotional attachment to place is highlighted by Ordoukhani [

20], who emphasizes the need for ECH design to incorporate features that are relevant to inhabitants’ interests and biographies.

While ECH emphasizes individuality, social integration, and autonomy, there are extreme challenges for architects in balancing ideals with realistic constraints. Budgets, regulatory demands, and shifting care needs have a tendency to strain the balance between innovative design and pragmatism [

21]. Resolution of these challenges requires cooperation among architects, policymakers, and care agencies. The Housing LIN report explains the potential of modular construction and intelligent home technology (IHT) to render ECH more flexible and cost-effective [

22]. Therefore, this research seeks to examine how UK architects approach the design of ECH environment with the aim to enhance residents’ QoL.

2. Materials and Methods

The research question guiding this study is, what are the perceptions of architects regarding the QoL in Extra Care Housing? The data for this study was collected from semi-structured interviews with architects in the UK. As Bryman [

23] argues semi-structured interviews in sociological research provide room for flexible questioning and enable researchers to collect in-depth data. As the study is perceptions based, the tool helped collect rich data. Since the data collection was implemented during the lockdown associated with the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020—May 2021), the interviews were conducted online using Zoom. Each interview lasted between 30 to 60 minutes.

Participant recruitment used a convenience and snowball method. The researcher contacted architectural firms with experience in ECH projects from seven UK locations to seek permission from architects to interview. Once a participant agreed to be interviewed, they were then asked to recommend other participants with similar expertise. A total of 12 architects were selected and interviewed (

Table 2). They showed an average experience of 16.3 years, ranging from 5 to 30 years.

Kallio et al.’s model of constructing semi-structured interviews was followed. Based on the literature review and the researcher’s understanding of the context, 11 interview questions were formulated (

Table 3) [

24]. The interview schedule developed was then piloted with a known architect and shown to academics in the field. After suggestions and further consideration, a final interview schedule was developed.

The participants received 11 questions in advance for a better understanding. Following research ethics procedures of the peer review, all participants were notified of the purpose of the study through a project information sheet and were asked for their consent to participate in the interview. They were assured of anonymity and ability to withdraw at any time. Furthermore, the data was used for research purposes and was accessible only to the researcher. The interviews were analyzed through a content analysis approach using a deductive qualitative analysis in NVivo. The recorded interviews were first transcribed. Based on the researcher’s understanding of the ECH framework and the existing literature, a list of 25 codes was created. A deductive coding was applied since the researcher was familiar with the QoL in ECH literature [

25]. The data was input in NVivo and using the existing codebook the data was further analysed. As Jackson and Jackson et al. [

26] state, NVivo helped organize the data, however, the analysis and critical thinking was completed by the researcher. Content analysis approach was used to analyse the data as it is a highly flexible research method that has been widely used in library and information science studies with varying research goals and objectives [

27]. As part of the coding, the pre-created list of codes was further developed and as a result, the complete list consisted of 61 codes. Once the codes were sorted, they were classified into six initial themes:

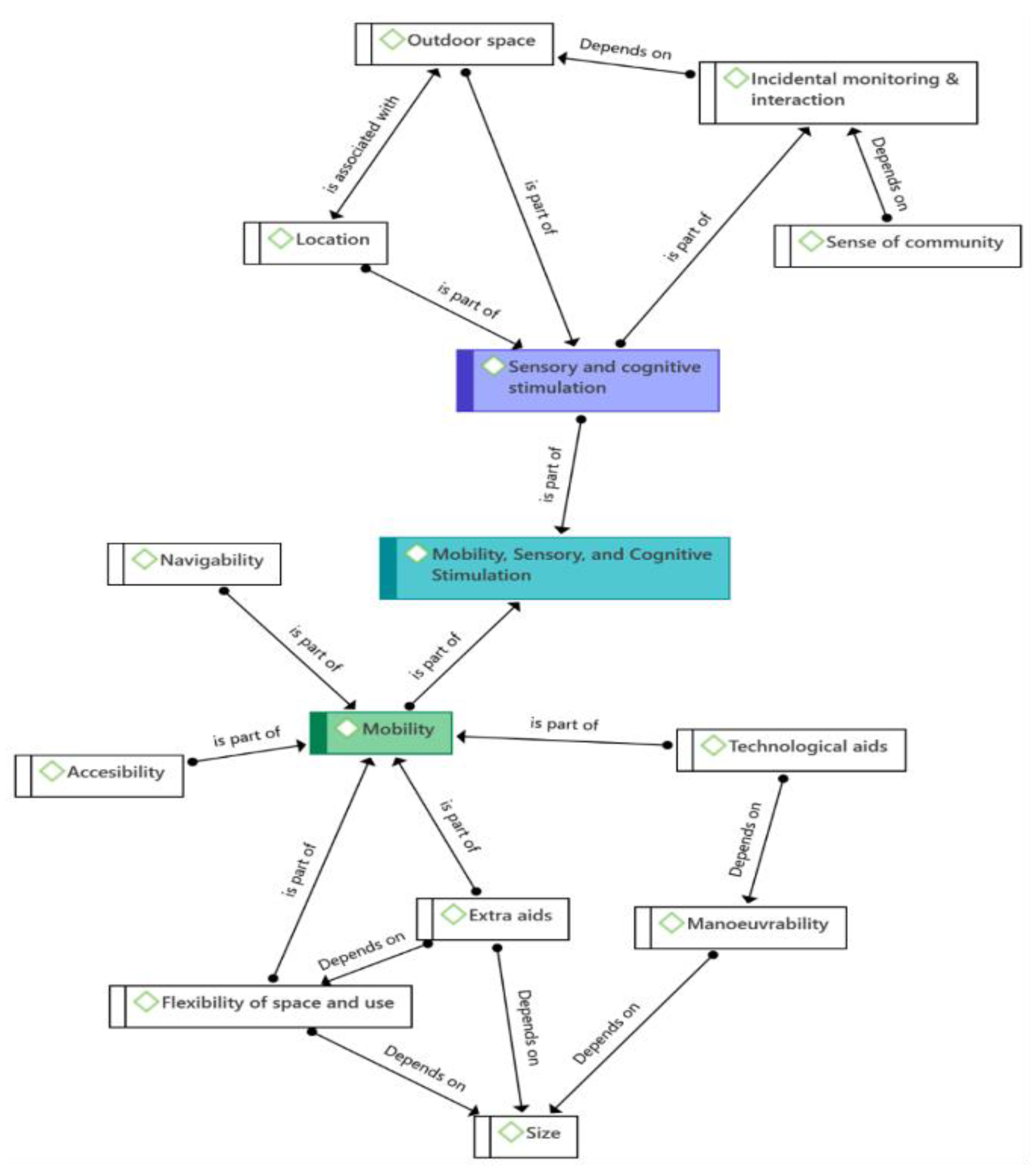

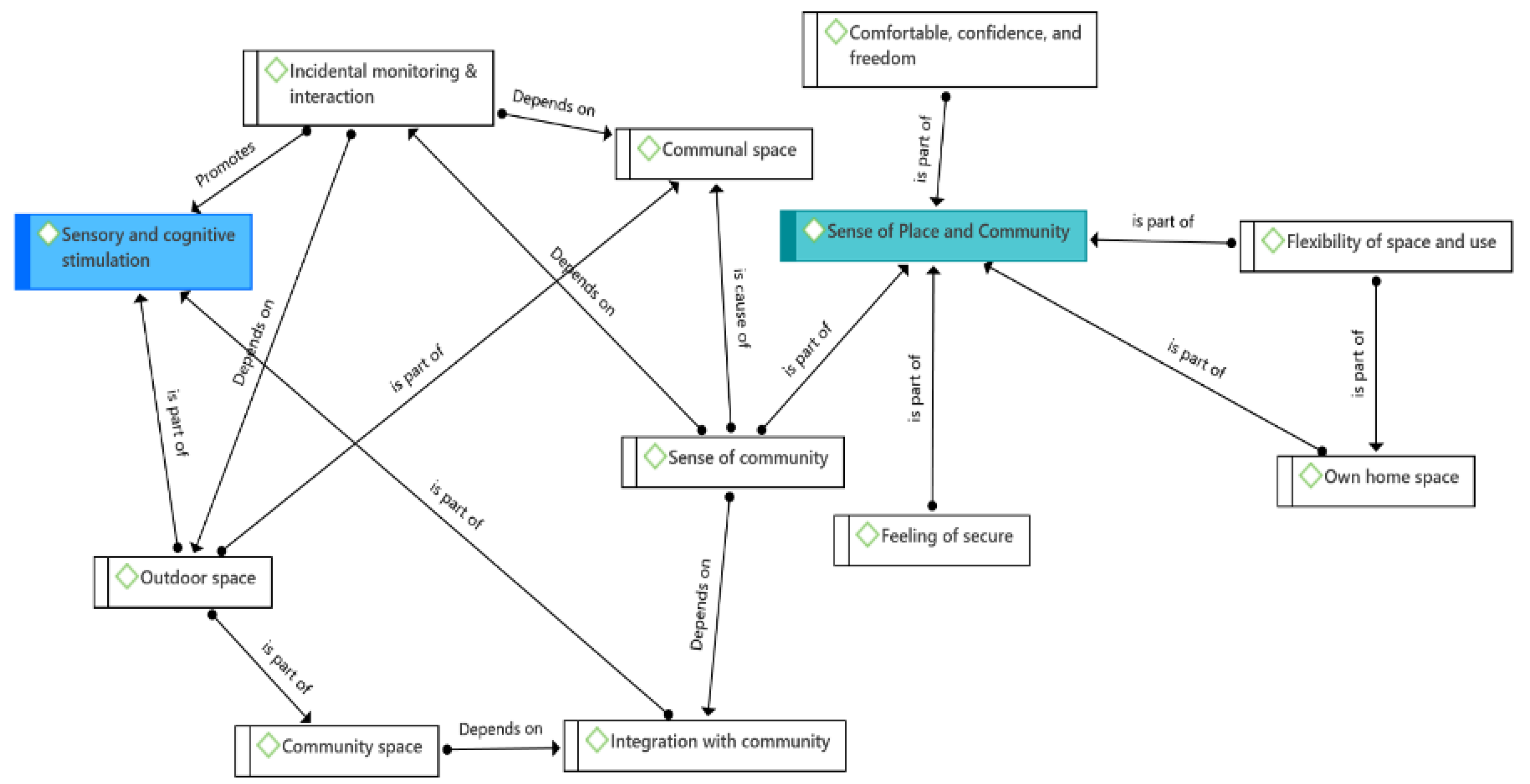

The analysis focused on studying the relevance of these codes to architects’ understanding during ECH design and construction, as well as their relationship to each other within each category. To investigate these relationships, code concurrence was evaluated by cross-tabulations, i.e. checking the number of times that different codes appeared together within a quote. Next, to evaluate whether the interviewees made some relationship between those codes, the quotes with code concurrence were assessed in further detail. The concurrence of codes was evaluated, and the relationships were depicted in diagrams.

3. Results

The architects considered six areas to be important for ECH including: (1) controllability; (2) accessibility; (3) safety; (4) technological aids; (5) navigability; and (6) own home space. From their discussion of these key areas, the following sub-themes were extracted:

Sense of Community

Health and Safety

Choice and Control

3.1. Sense of Community

A central sub-theme was the sense of community which can emerge from several elements, such as incidental interactions, depending on the design and use of communal spaces, including outdoor spaces. The sense of community can be elicited by integration with the local community whereby older residents do not feel isolated; this integration is promoted by the inclusion of community spaces open to the local public and is affected by the location of the building since it is important to keep residents local so that they do not lose their social connections and activities. This is reflected in the following quote by Architect A:

“Familiar places they used to go should still be local places so I think the most important thing for me is to get to provide appropriate housing for older people in not far from where they would have anything throughout the rest of their lives” (Architect A).

A good location also has positive effects on sensory and cognitive stimulation as highlighted by some participants.

“Sensory stimulation, a sense of community they began to do a bit more and their physical wellbeing improved, and they began walking to the local shop on their own to do some grocery shopping” (Architect G).

The architects talked about space such as communal dining areas and social spaces where older people can meet each other and greet their visitors as well. As one of the participants noted:

“Yeah, that’s great that’s really important as a part of it and I think again it's like it's incorporating dining in those places where there’s place for interaction or you know, again external spaces are so key because that's where people go for walk and bump into you know” (Architect K).

3.2. Health and Safety

Health and safety were very important to the participating architects. They discussed what safety measures should be taken in order to make the ECH a safe and healthy place for older citizens to live in. As one of them mentioned that fire safety measure must be considered in all ECHs:

“The biggest one is fire risk at the moment. That's the number one thing everybody's talking about thinking about in the industry and that tends to- we’re now looking at kind of sprinkler type systems more to ensure that the residents are kept safe in the event that there is a fire” (Architect D).

Most important among such elements aimed at ensuring older residents’ safety were navigability (also related to good illumination), manoeuvrability (related to corridors’ size), fall prevention, and overheating prevention. Considering the age of the residents, it was important to Architect B that there should be measures to ensure that they do not fall.

“I mean these quick simple things like having a flush threshold and always making sure there are no trip hazards. Making sure that floor is slip resistant so that even if you were in the kitchen if you spill water or oil on the kitchen floor, it's not slippery similarly in the bathroom” (Architect B).

Architect D talked about ventilation as that will avoid overheating, whereas Architect E considered illumination with proper daylight as important for health and safety as that will help visibility and avoid accidents. Proper assistance and management of the facilities was also considered important.

“What assistance is put in place to call staff if they need to, what’s technology around on that, that’s really important” (Architect F).

3.3. Choice and Control

The architects talked about control over communal areas, flexibility and interchangeability, communal spaces, outdoor spaces, own home space, flexibility of space and use, controllability, and space configuration. These issues reflect the need for choice and control. Most of the architects reported that having their own home spaces was a key factor affecting older residents’ feelings of exerting control over their surroundings. This is reflected in the following words by Architect F:

“I think being able to take and make it their homes. To some extent we provide a shell and them being able to actually how they use it, how they are able to personalize it. So, personalizing your front door is really important and then personalizing the inside of your flat and actually balconies” (Architect F).

Other relevant themes were the controllability of simple things such as thermal control or easy use of spaces, the flexibility of the space and use (personalization), flexibility in the use of communal spaces (flexibility and interchangeability), and the balance between privacy and socialization (space configuration). As one of the architects said,

“The ability to sort of control your thermal comfort or elements of your home” (Architect G).

Another important sub-theme mentioned was the feeling of control over some communal areas, including some outdoor spaces such as parking. Although most older people do not have a car, the possibility of owning one would give them a greater sense of independence; older people should feel that such areas are available to them whenever they wish. This is reflected in the following suggestion by Architect K:

“There's usually gardens or communal facilities which are then free for them to use. So, it gives them that sense of like, okay, you know, I'm living within an extra care thoughts but it also gives that level of Independence” (Architect K).

4. Discussion

Findings from these interviews reveal a balance between autonomy and necessary care support. While architects recognize the need for accessibility, they also highlight potential constraints, including budget limitations and regulatory frameworks. The study underscores the significance of integrating community-oriented design principles within ECH to combat social isolation. Furthermore, the discussion section now directly engages with contemporary debates in the literature, contrasting findings with key studies in ECH design and management.

4.1. Sense of Community

If activities and social interaction enhance QoL due to their positive effect on people’s health and well-being, then reducing social isolation is a focal concern in ECH [

28,

29]. Accordingly, the community is intrinsically related to features that support both in-building activities and socialization, as well as older people’s connections with the external community. Both components were explicitly mentioned by the interviewed architects. The data revealed that having a sense of community was important and it could be fostered by them being in a location where they had spent most of their adult lives. In the literature, the connection to the external community was reported to be largely affected by the location of the building and the presence of the spaces open to the local community [

30,

31]. Location was also deemed to be important for older residents in terms of maintaining family and social networks [

32]. In agreement with these statements, the interviewed architects mentioned that these two features helped them to achieve their designs’ better integration with the local community.

According to the interview data, the architects sought in-building socializations through incidental interactions that depended on the design of communal spaces. A similar argument was made by Nordin et al. [

31] who claimed that features of the physical environment—with the arrangement of communal spaces being the most important one—play an important role in supporting activities and interactions among older people living in residential care facilities [

31,

33]. Similarly, Shin [

19] noted that adequate space allocation and the design of communal areas have an important effect on residents’ desire to socialize. It is therefore highly important to build ECH where residents can feel a sense of community and adjust easily into the surroundings.

4.2. Health and Safety

Buildings are commonly characterized by high levels of compliance with safety issues, which constitute a strong focus on building regulations and ECH design guidelines [

10,

31]. The architects’ perspectives on Health and Safety were focused on security, perceived safety, and fall hazard. In agreement with previous literature demonstrating that security is associated with neighborhood [

19,

28]—for instance, areas with limited noise were reported to provide a sense of safety and security [

19]—the architects mentioned taking care of the location of the building, with preference given to low crime areas. Additionally, assistive technology may have the following three positive impacts: reducing residual disability, slowing down functional decline, and decreasing the burden of caregivers, which is associated with better QoL of residents in ECH schemes [

34,

35]. Along with technologies related to mobility (e.g., grab rails), assistive technology, in a broader sense, can also include “smart homes” with innovative devices such as remote sensors and telecare systems [

36]. Despite the broad range of issues within the technology sub-theme, the architects only mentioned issues related to fire safety, overheating prevention, and telehealth systems.

Fall hazards can be considerably increased by poor accessibility, flooring surface, poor lighting, insufficient space to maneuver and pass, inappropriate design of furniture, and lack of grab bars [

37,

38]. The architects’ feedback suggested that they were aware of all the above-mentioned features, thus seeing color contrasts, illumination, wide corridors, and simple building layout as important design features to ensure older people’s safety, which they also associated with additional cognitive stimulation.

Physical health was largely overlooked in the architects’ interview data. Only one of them stated, “The idea behind that is to create a very interesting space that would encourage people to use the stairs and not a lift. To try and encourage people to be physically active” (Architect X). Since walk-friendly infrastructure is positively associated with physical activity and walking, features that provide walking opportunities, such as avoiding dead ends, path levels, and provision of adequate seats for resting are recommended to support older adults’ physical activity [

36,

39].

One issue commonly associated with Independence mentioned by architects was the flexibility of home modification. The interviewees noted that the possibility of setting extra aids as people get older and need them is a key issue. Consistently with this, home modifications were previously reported to increase building usability and thus health-related QoL [

40]. Therefore, the findings related to health and safety align greatly with existing literature on ECH architecture.

4.3. Choice and Control

Choice and control encompass the concepts of privacy and feeling of freedom [

19,

33,

41]. The architects argued that residents should have choice and control in their spaces whenever and wherever possible. Some of the physical features mentioned in the literature as important in terms of supporting older people’s autonomy include flexible space for personalization and modification, wayfinding support (e.g., simple building layout and features promoting cognitive stimulation), sufficient space for mobility and maneuverability, easy control of everyday objects (light doors and windows, adequate height of objects), communal spaces and enablers such as handrails, lifts, and assistive technology/mobility aids [

28,

38,

42].

As residents—even those who use mobility aids—need sufficient space to move around [

30], the interviewed architects saw wide corridors as an important design feature to support older people’s independence. Similarly, wide corridors are also an important feature specified in most building regulations. However, although some ECH design guidelines specify minimum space requirements for circulation [

10,

31], the interviewed architects were unaware of these requirements. This aspect was not mentioned by the interviewees in the data, evidence, and validity section.

Another feature highlighted by most architects was the ease of access to everyday objects such as doors, windows, kitchens, drawers, heating, lights, and so forth. As older residents have limited strength and some movement limitations, heavy doors and windows, as well as inadequate placement of objects (too low or too high) may hinder residents’ activities and their independent use of spaces [

31,

33,

42]. The fact that some design principles for ECH have a specific section dedicated to the design for physical frailty highlights the importance of these features to support older people’s autonomy [

32].

Several guidelines for ECH design include architectural features conceived to aid older residents to find their way around the building [

10,

31,

36]. Relevant examples of such features include signage, color and texture contrasts, and visibility [

10,

31]. For the same purpose, several guidelines specifically indicate that buildings should be simple in plan [

32]. In line with these regulations, the architects mentioned that to facilitate older people’s mobility and orientation, they designed understandable building layouts. However, the features related to cognitive stimulation were rarely mentioned by the interviewees, although this is an important second dimension of the wayfinding (Marquardt et al., 2011). Having their own living space, which residents could personalize the way they saw fit, was frequently highlighted by architects as a feature promoting residents’ independence. This insight from the interview data is fully consistent with Shin's observation that most residents in the ECH schemes modify their living rooms by adding elements such as shelves for raising plants, covering carpets, and floor lamps [

19]. Similarly, van Hoof et al., [

44] pointed out that pieces of furniture are among the objects with the most sentimental value for residents that move into ECH schemes, so the possibility to bring their possessions is valuable. However, despite its importance, it does not seem to be considered in some ECH design assessment tools that are developed in the academic domain, such as the Sheffield Care Environment Assessment Matrix (SCEAM) [

45] or the Evaluation of Older People’s Living Environments (EVOLVE) [

10]. They are tools for evaluating the design of housing for older people and are used to assess how well a building contributes to the physical support and personal well-being of older people.

This study’s findings should be interpreted in relation to prior research and the theoretical framework guiding the investigation. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible, including cultural, operational, and policy perspectives surrounding ECH development. Future research may benefit from incorporating the voices of residents and frontline care staff to triangulate perspectives and explore overlooked or implicit design values.

5. Conclusions

Architects play a crucial role in shaping ECH environments that promote independence, community, and safety. Design strategies must align with evidence-based principles to ensure sustainable, resident-centered housing solutions for older adults. This study contributes novel insights into architectural decision-making within the ECH sector and highlights key considerations for future design practices and policy developments. The research goal of this study was to investigate whether the architectural design features of ECH can be used to fit the quality of life of residents with the design of the physical environment.

This study used interviews to understand the meaning and context of the participants’ responses, including a systematic analysis guided by qualitative content analysis to identify and interpret themes. The main objective was achieved by understanding the subjective experiences and perceptions of the participant architects.

The validation of the Housing Our Ageing Population Panel for Innovation was considered, reporting case studies with design features and providing information about how the schemes are integrated with the wider community.

The analysis revealed that, in their ECH designs, the architects sought to create for residents a sense of home, a sense of place, a sense of community, and the feeling of being an important part of it. Enablers considered in ECH schemes included physical features that support wayfinding (e.g., a simple building layout, signage), sufficient space for mobility, and easy-to-operate design of everyday things (e.g., windows, doors, drawers, etc.). Enablers such as handrails and others were not mentioned by the architects, since these are part of older people’s diverse health needs, and their lack may represent a barrier to older residents’ independent living. However, acknowledging older residents’ need for such enablers, some architects mentioned the possibility of adding them to their ECH designs.

The sub-themes that emerged in the analysis and the concurrence of the same codes in different themes also showed interconnections among different QoL domains. For instance, general satisfaction may depend on independence and sense of place issues, while independence may depend on mobility and sensory and cognitive stimulation.

Some limitations in this study were recognized such as the limited number of architects and the sample size not being fully representative of the architects involved in ECH in the UK; the architects’ statements being different from their actual practice in ECH.

Future research needs studies to verify the validity of the design themes and how they can be established across different contexts. This examination may use qualitative measures such as interviews with residents and stakeholders before and after moving into ECH schemes. To further improve the physical environment of the ECH designs for improved QoL of the residents, it is necessary to involve the target population in the design process. This can be facilitated by developing validated tools for capturing QoL as a consequence of the built environment features developed for older people. An established framework should include several domains and levels of validity of evidence by integrating subjective assessment of residents and objective measurements through caregivers and/or support workers. This can further optimize the physical environment and maximize the QoL of the aging population in ECH facilities.

Designers and architects can incorporate findings from this study into future building designs by ensuring that the core themes are considered and inform the new ECH plans. Design elements such as accessibility, maneuverability, views, and design could be considered by architects in order to ensure that ECH schemes meet the needs of residents. Finally, for future research, a study on comparison (relation) on quantitative computational methods using a software and cross-sectional study of older users could be planned and performed.

This study provided a base for the development of the conceptual framework on how the physical housing elements impacted older people’s QoL. Despite the above limitations and considerations, this study contributed valuable and original data to use in practical applications for ECH design in the UK.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ECH |

Extra Care Housing |

| EBD |

Evidence-Based Design |

| QoL |

Quality of Life |

References

- Croucher, K.; Hicks, L.; Bevan, M. Comparative Evaluation of Models of Housing with Care for Later Life; Joseph Rowntree Foundation: York, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, S.; Vallelly, S. Social Well-being in Extra Care Housing; Joseph Rowntree Foundation: York, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, P.; Cameron, J.; Evans, B. Reimagining Extra Care Housing: A Focus on Autonomy and Community Integration. J. Aging Study 2023, 37, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wiles, J. L., Leibing, A., Guberman, N., Reeve, J., & Allen, R. E. S. , The Meaning of “Aging in Place” to Older People. The Gerontologist, 2012. 52, 357–366. [CrossRef]

- Willis, P.; Vickery, A.; Symonds, J. “You have got to get off your backside; otherwise, you’ll never get out”: Older Male Carers’ Experiences of Loneliness and Social Isolation. Int. J. Care Caring 2020, 4, pp.311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B., Chen, Q., Buys, L., Susilawati, C., & Drogemuller, R., Impact of the Built Environment on Ageing in Place: A Systematic Overview of Reviews. Buildings, 2024. 14, 2355.

- Abramsson, M. , & Andersson, E., Changing preferences with ageing–housing choices and housing plans of older people. Housing, theory and society, 217–241.

- Office for National Statistics. Household Total Wealth in Great Britain: April 2020 to March 2022; Statistical Bulletin; ONS: Newport, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kingston, A.; Robinson, L.; Booth, H.; Knapp, M.; Jagger, C. Projections of multi-morbidity in the older population in England to 2035: estimates from the Population Ageing and Care Simulation (PACSim) model. Age Ageing 2018, 47, pp.374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, A., Torrington, J., Barnes, S., Darton, R., Holder, J., McKee, K., Netten, A., & Orrell, A. EVOLVE: A tool for evaluating the design of older people’s housing. Housing, Care and Support 2010. 13, 36–41. [CrossRef]

- Tang, M. , Wang, D., & Guerrien, A., 2020. A systematic review and meta-analysis on basic psychological need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in later life: Contributions of self-determination theory. PsyCh Journal, 9, pp.5–33.

- Rodiek, S. D. , & Fried, J. T., Access to the outdoors: Using photographic comparison to assess preferences of assisted living residents. Landscape and Urban Planning 2005, 73, pp.184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund-Snodgrass, L., & Nord, C. , The Continuation of Dwelling: Safety as a Situated Effect of Multi-Actor Interactions Within Extra-Care Housing in Sweden. Journal of Housing for the Elderly 2019. 33, 173–188. [CrossRef]

- Jung, S., Uttley, L., & Huang, J., Housing with care for older people: A scoping review using the CASP assessment tool to inform optimal design. HERD, 2022. 15, 299–322.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bruggencate, T. Ten, Luijkx, K. G., & Sturm, J., Social needs of older people: A systematic literature review. Ageing and Society, 2018. 38.

- Trust for America’s Health. Ensuring Age-Friendly Public Health in Rural Communities; Trust for America’s Health: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Anton, C. E. , & Lawrence, C., Home is where the heart is: The effect of place of residence on place attachment and community participation. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2014, 2014. 40, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.-H., Listen to the Elders: Design Guidelines for Affordable Multifamily Housing for the Elderly Based on Their Experiences. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 2018. 32, 211–240. [CrossRef]

- Ordoukhani, D.; Khoshnevis, A.M.K. Designing Nursing Homes Using Sense of Attachment to Place Approach. Int. J. Health Syst. 2022, 8, 11549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vischer, J. C. , Applying knowledge on building performance: From evidence to intelligence. Intelligent Buildings International 2009, 2009. 1, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housing LIN. Going Digital – Living Better for Less with Technology-enabled Housing; Housing Learning and Improvement Network: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.-M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bingham, A.J. From Data Management to Actionable Findings: A Five-Phase Process of Qualitative Data Analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, K.; Bazeley, P. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.D.; Marsh, E.E. Content Analysis: A Flexible Methodology. Library Trends 2006, 55, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrell, A., McKee, K., Torrington, J., Barnes, S., Darton, R., Netten, A., & Lewis, A. The relationship between building design and residents’ quality of life in extra care housing schemes. Health and Place, 2009. 21, 52–64. [CrossRef]

- Rowe, JW. & Kahn RL., Successful aging 2.0: conceptual expansions for the 21st century. Journals of Gerontology: Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 2015. 70.

- Burton, E, & Sheehan, B., 2010. Care-home environments and well-being: Identifying the design features that most affect older residents. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 27, 237–256.

- Nordin, S. , Elf, M., McKee, K., & Wijk, H., Assessing the physical environment of older people’s residential care facilities: Development of the Swedish version of the Sheffield Care Environment Assessment Matrix (S-SCEAM). BMC Geriatrics 2015, 2015. 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y. Social Networks for Older People’s Resilient Aging-in-Place. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 82, 103882. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, S. , Torrington, J., Darton, R., Holder, J., Lewis, A., McKee, K., Netten, A., & Orrell, A., Does the design of extra-care housing meet the needs of the residents? A focus group study. Ageing and Society 2012. Ageing and Society 2012, 2012. 32, 1193–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlabi, H.; Parker, S.G.; McKee, K. The Contribution of Home-Based Technology to Older People’s Quality of Life in Extra Care Housing. BMC Geriatr. 2011, 11, p.68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agree, E. M., Freedman, V. A., & Sengupta, M., Factors influencing the use of mobility technology in community-based long-term care. Journal of Aging and Health, 2004.16, 267-307.

- Housing LIN. Building for a Healthy Life; Housing Learning and Improvement Network: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Currin, M. L., Comans, T. A., Heathcote, K., & Haines, T. P., Staying Safe at Home. Home environmental audit recommendations and uptake in an older population at high risk of falling. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 2012. 31, 90–95. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D., & Portillo, M. , Fall Hazards Within Senior Independent Living: A Case-Control Study. HERD, 2018. 11, 65–81. [CrossRef]

- Barnett, D.W.; Barnett, A.; Nathan, A.; Van Cauwenberg, J.; Cerin, E. Built Environmental Correlates of Older Adults’ Total Physical Activity and Walking: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, p.103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnemolla, P.; Bridge, C. Accessible Housing and Health-Related Quality of Life: Measurements of Wellbeing Outcomes Following Home Modifications. Int. J. Archit. Res. 2016, 10, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Steenwinkel, I.; Dierckx de Casterlé, B.; Heylighen, A. Design for Dementia: The Role of Architecture in Promoting Autonomy and Well-being. Gerontologist 2017, 57, e15–e26. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzi, M., Chalmers, J., Bunout, D., Osorio, P., Fernández, V., Cusato, M., Avendaño, V., & Rivera, K., Physical barriers and risks in basic activities of daily living performance evaluation in state housing for older people in Chile. Housing, Care and Support 2013. 16, 23–31. [CrossRef]

- Marquardt, G. , Johnston, D., Black, B. S., Morrison, A., Rosenblat, A., Lyketsos, C. G., & Samus, Q. M., A Descriptive Study of Home Modifications for People with Dementia and Barriers to Implementation. Journal of Housing for the Elderly 2011. 25, 258–273. [CrossRef]

- van Hoof, J.; Janssen, M.L.; Heesakkers, C.M.C.; van Kersbergen, W.; Severijns, L.E.J.; Willems, L.A.G.; Wouters, E.J.M. The Importance of Personal Possessions for the Development of a Sense of Home of Nursing Home Residents. J. Hous. Elderly 2016, 30, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C. , Barnes, S., Mckee, K., Morgan, K., Torrington, J., & Tregenza, P., Quality of life and building design in residential and nursing homes for older people. Ageing and Society 2004, 2004. 24, 941–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).