1. Introduction

The global population is aging rapidly, prompting urgent attention as to how housing environments can support the autonomy, health, and overall well-being of older adults [

1]. In response to these demographic shifts, Extra Care Housing (ECH) has emerged in the UK as a promising hybrid model that integrates independent living with tailored care provision [

2]. ECH offers older individuals a “home for life” with access to flexible care services, communal spaces, and support for aging in place. It aims to bridge the gap between traditional residential care and independent housing, fostering both physical safety and social connectedness [

3].

Despite growing interest in ECH, there is limited empirical understanding of how design and care-related features of ECH environments translate into quality of life (QoL) outcomes. Existing studies have primarily focused on the perspectives of residents, often underrepresenting the insights of care managers, professionals who are central to managing care delivery and environmental adjustments in ECH schemes [

4]. This presents a critical research gap, especially when evaluating how built environments and service frameworks in ECH schemes contribute to residents’ QoL [

5]. Furthermore, limited attention has been paid to how these care environments interact with physical design features, safety considerations, and social infrastructures to promote independence and well-being [

6]. To address this gap, this paper presents findings from interviews with care managers involved in managing ECH schemes. The interviews explored the care managers’ perceptions of ECH, their understanding of QoL aspects, and the enablers and barriers in ECH schemes. The QoL domains associated with ECH were selected based on a systematic literature review that underpins this research and includes community, independence, choice and control, health and safety, general satisfaction, and sense of place [

7].

This study is guided by the following objectives:

- ▪

To explore care managers’ perspectives on how ECH environments support the QoL of older residents.

- ▪

To identify key environmental and operational features perceived to enable or hinder resident independence and satisfaction.

- ▪

To analyze how ECH schemes address care needs while maintaining autonomy and a sense of home.

- ▪

To develop a thematic framework based on care managers’ insights, linking design and care features to specific QoL domains based on care managers’ lived professional experience.

This study seeks to address several research questions:

- ▪

How do care managers perceive the role of physical and social environments in enhancing older residents’ quality of life within ECH settings?

- ▪

What are the perceived enablers and barriers to promoting autonomy, safety, and well-being in ECH environments?

- ▪

How do the elements of care delivery, personalization, and spatial configuration intersect to influence residents’ lived experiences from caregivers’ perspectives?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Extra Care Housing: Concept and International Perspectives

Extra Care Housing (ECH) is a distinctive form of housing with care that seeks to provide a middle ground between fully independent living and institutional long-term care. Unlike conventional residential homes, ECH schemes are designed to allow residents to maintain autonomy while receiving varying levels of care within purpose-built or adapted accommodation. The UK’s development of ECH emerged from policy ambitions to de-institutionalize older adult care and promote “aging in place”, particularly following the introduction of the Supporting People program and subsequent housing-with-care strategies by organizations such as Housing LIN and the Department of Health [

8,

9], which aimed to reduce a reliance on long-term institutional care while promoting independence, choice, and community integration. ECH in the UK typically involves a mix of housing management, personal care provision, and communal facilities, with considerable variation in configuration depending on whether schemes are operated by local authorities, housing associations, or private developers [

9,

10]. The policy environment has continued to evolve towards integrated health and social care models, positioning ECH as a flexible infrastructure through which to deliver such integration.

Comparative international models illustrate both conceptual alignment and contextual divergence. In the Netherlands, the “Apart en Toch Samen” (“Apart and Together”) model integrates individual dwellings with shared amenities and community-facing services, reinforcing both privacy and collective engagement. These schemes frequently prioritize social participation and urban integration, offering non-residents access to on-site cafés, activity centers, and open gardens [

11]. Sweden, by contrast, adopts a universalist approach grounded in social rights, emphasizing co-produced care environments that support autonomy and social inclusion through inclusive architectural standards and municipal oversight [

4].

Japan’s Serviced Senior Housing model reflects a technologically mediated solution to its super-aged society. This model utilizes ambient monitoring, sensor-based systems, and remote healthcare interfaces to deliver responsive care within compact, barrier-free units [

13]. Importantly, the model is designed to optimize resource efficiency while maintaining individualized support, often through collaborations between housing providers and municipal health departments.

In the United States, the dominant equivalent to ECH is the Assisted Living (AL) model, which similarly offers private residential units with varying levels of personal care, meal services, and activity programming. However, unlike the UK’s partially publicly funded ECH model, AL in the US operates largely within a market-based framework, often characterized by for-profit ownership, private pay financing, and minimal federal regulation [

14]. Although AL facilities promote independence and social interaction, variability in quality and accessibility remains a concern, particularly among lower-income populations. Nevertheless, AL continues to expand as a preferred alternative to nursing homes, particularly in states where Medicaid waivers support limited public subsidization of services.

Australia and New Zealand offer further instructive contrasts. Australian retirement villages typically operate on leasehold or strata-title ownership models, blending lifestyle features with optional care services, though integration of clinical care remains limited. New Zealand’s housing-with-care policy has taken a more equity-oriented approach, explicitly addressing affordability and indigenous cultural needs within supported housing development [

15].

While these international models are embedded within diverse welfare regimes and care market structures, they share key principles: person-centered care, environmental adaptability, and the integration of housing and support as co-dependent determinants of quality of life. Yet, despite the conceptual alignment, there remains a paucity of cross-national frameworks to evaluate how environmental and managerial practices mediate user experiences.

2.2. Dimensions of Quality of Life in ECH

Aging in place is a well-recognized concept used to describe how older people prefer to remain living in the community, with some level of independence [

9] because this enables them to maintain their autonomy [

16]. Although older people typically desire to stay where they have lived, it can be risky, especially for those who lack functional independence [

18]. For this reason, care managers have become an appropriate solution for older people to live their lives with independence while remaining at their original residence. In practice, the main principle that ECH claims is to enable residents’ independence and sense of home. The impact of aging in place on the sense of belonging and attachment remains consistent as people become older. In other words, aging in place works by binding people to their community, with a feeling of belonging that is related to a sense of well-being on any specific positive or negative influence [

17]. Place attachment also improves the quality of living, it benefits physical and psychological health, helps to reduce stress levels, and enhances users’ satisfaction with the physical environment [

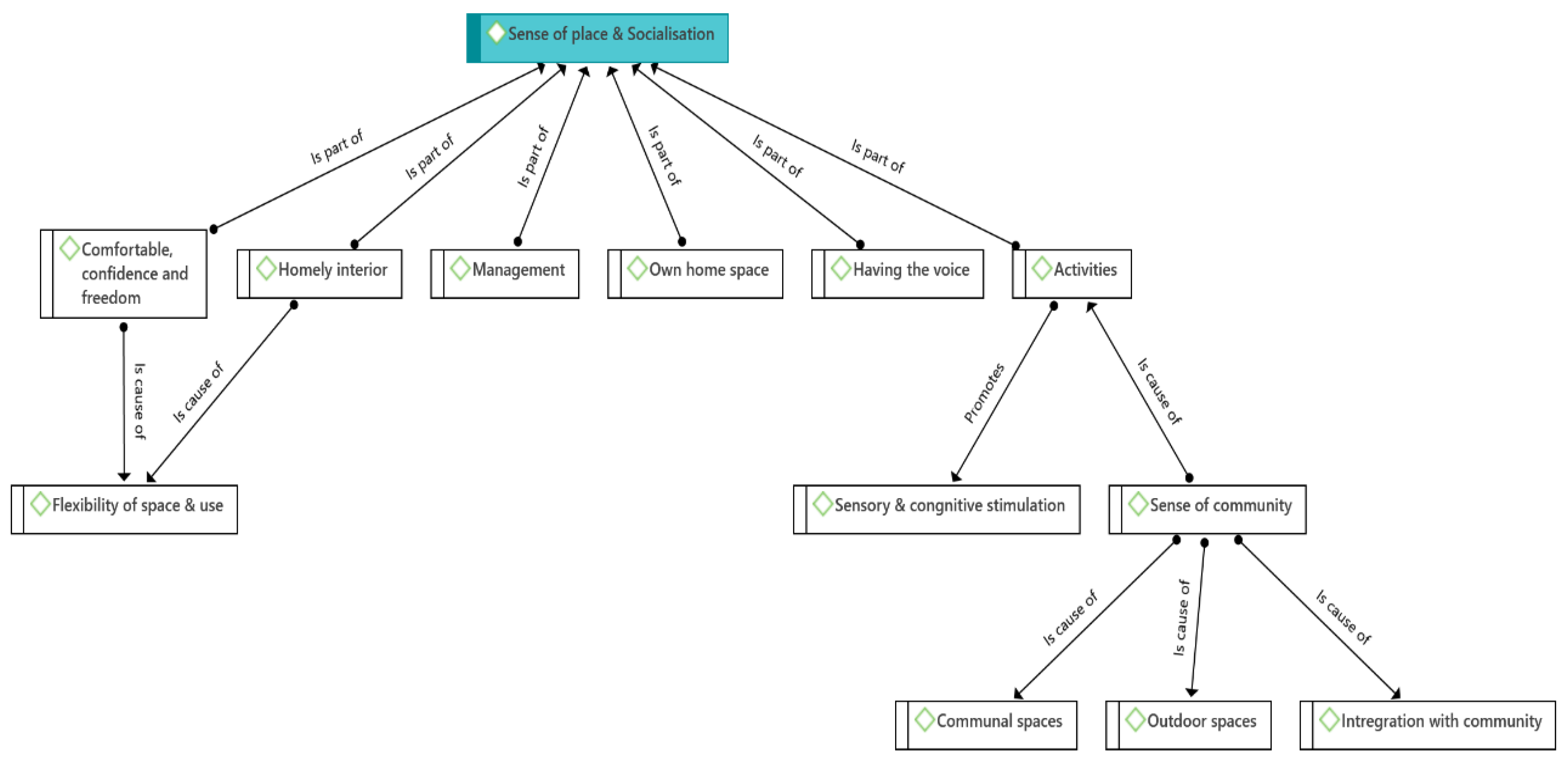

18]. Home management (having their own home space and the flexibility of space and use) represents an important source of well-being for older people [

19]. Two key sub-themes related to the sense of place theme mentioned by the interviewed care managers were (1) the personalization of private spaces through the use of residents’ own furniture and belongings, which fostered a sense of familiarity and identity, and (2) the perception of comfort and control over their environment, which enhanced their emotional attachment to their home. The flats were given to them unfurnished, so they could bring their own furniture and personal objects to decorate their own spaces, which created a homely interior providing personalization and a sense of comfort, confidence, and freedom.

Building in this context, QoL serves as a key evaluative framework in this study, particularly within the context of ECH, where resident well-being is shaped by both physical and social environments. QoL is understood here as a multidimensional construct encompassing physical health, psychological well-being, autonomy, social connectedness, and environmental comfort. The selected domains for analysis—independence, care and safety, social engagement, autonomy, and overall satisfaction—were guided by established frameworks, including Lawton’s ecological theory of aging and the World Health Organization’s QoL instruments (WHOQOL), and were further refined through insights gained from the author’s previous publication on QoL in ECH environments [

7]. This prior research provided an evidence-based foundation for constructing a thematically grounded codebook in the current study.

2.3. Caregivers’ Role in ECH

As people age, their care needs increase and become more diverse. Abramson and Andersson found that the most pronounced changes for people between 75 and 84 years and those older than 85 years are concerned with housing size and tenure. They indicated a gradual change as time passed with older people preferring large housing compared to small housing and a change from owner occupation to rental of the housing. Furthermore, responses from people living in large cities, rural areas, or tourist places showed that they are less willing to move [

20].

As the share of older populations increases, the pressure on care managers also increases. In the UK, it is expected that people over 65 years old will live with a disability sometime during the rest of their lives. , Moreover, 65-year-old men are expected to live 10 of 19 years during the rest of their lives without a disability, while women of the same age can expect to live 10 of 21 years without a disability [

17]. Furthermore, Kingston et al. showed that most people aged 65 and older experience a minimum of two chronic health problems that affect their daily lives [

12]. In addition, as people age, they may need help with everyday activities such as eating, showering, and getting dressed. In the UK, the percentage of 65-year-old men and over needing help increased by 15% to 36% and for women, it is 49% [

21]. Thus, the data suggest that longevity is accompanied by numerous health problems and conditions beginning in the middle of life. Getting old leads to a myriad of changes, including physical, cognitive, and social. Such changes will inevitably influence how older people interact with the environment and their community. In cases of a decline in visual and hearing capacity, the association with injuries increases [

22].

Care managers play a crucial role in addressing the needs of older populations in ECH facilities to improve their QoL. Tang et al. highlighted the importance of older people feeling autonomous, competent, and connected to others in ECH facilities [

24]; this can be aided by care managers providing choices and opportunities to satisfy basic psychological needs, motivation, and well-being. Socialization is also important for reducing loneliness among older residents [

23], and care managers can create opportunities for social interactions with the outside world [

24].

In addition, care managers need to prioritize health and safety in ECH facilities, as older people are often more vulnerable and at a higher risk of accidents [

25]. Choice and control are important in social care services, and care managers can work towards personalizing these services to improve the sense of self and overall QoL of residents [

26,

27]. The residents’ satisfaction with their QoL in ECH facilities depends on various factors such as the environment’s greenery, the attractiveness of the building, and comfort [

28,

29]. The sense of place, including feeling at home and belonging to the environment, is also crucial for residents’ life in ECH facilities and can be influenced by the location and spatial flexibility, something that care managers should consider [

30,

31].

ECH for older people emphasize autonomy, community integration, and individuality; thus, care managers should focus on incorporating evidence-based knowledge into the design of ECH facilities [

10]. The ECH approach aims to provide an age-friendly physical environment integrated with care services to promote independence and QoL improvement for residents. Care managers can play a crucial role in assessing the design features of ECH facilities before and after implementation through evidence-based design (EBD) processes, which can lead to the development and implementation of safer and more productive ECH settings [

32]. In addition to methodological flaws, ECH settings lack standardized guidelines; however, care managers can use EBD to ensure that the physical environment of ECH facilities addresses the needs and desires of older residents and promotes their health, satisfaction, and well-being.

By aligning the qualitative coding process with these conceptual dimensions, this study ensures a structured interpretation of how spatial design and care practices interact to support older adults’ everyday lives.

3. Methodology

This study used semi-structured interviews with the aim of asking questions within a predetermined thematic framework [33]. The interviews explored themes related to independence, care, health and safety, community, sense of place, choice and control, and general satisfaction while also allowing further exploration of participants’ responses. The interviews consisted of 10 questions that emerged from the literature review and were associated with the following six domains of QoL: independence, community, health and safety, choice and control, general satisfaction, and sense of place. In addition, to evaluate the care services provided in ECH schemes, the domain of care was included and was evaluated by two questions: (i) the minimum and maximum levels of care service provided, and (ii) the most needed care service offered to the residents. These questions were asked to gain a comprehensive understanding of older people’s eligibility for entry and the range of care options offered by each ECH scheme. The questions were distributed in advance among the participants who were assigned codes to ensure confidentiality (

Table 2).

Recruitment emails sourced through publicly available directories, professional networks, and direct outreach were sent to 78 care managers from which some were selected by the snowball method. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 14 care managers working in different ECH schemes in 10 locations in the UK (

Table 1). The managers were considered experts since they had experience ranging from 3 to 11 years.

Table 1.

Attributes of interviewed care managers.

Table 1.

Attributes of interviewed care managers.

| Manager ID |

Years of Practice |

Location of the Practice |

| Manager A |

9 |

Bristol |

| Manager B |

11 |

Bristol |

| Manager C |

5 |

Bristol |

| Manager D |

7 |

Newcastle upon Tyne |

| Manager E |

4 |

Bristol |

| Manager F |

6 |

Cumbria |

| Manager G |

9 |

Warwickshire |

| Manager H |

3 |

London |

| Manager I |

7 |

Sutton on Sea |

| Manager J |

5 |

Birmingham |

| Manager K |

8 |

Tyne and Wear |

| Manager L |

10 |

Cardiff |

| Manager M |

4 |

London |

| Manager N |

6 |

Denbighshire |

The participant’s name was not attached to the data collection. Ethical approval from the University was obtained on 28 January 2020 for the recruitment of participants and consent. The interviews were conducted from March to May 2021 online or via phone calls. Each interview lasted from 30 to 60 min. Several selected quotes from the care managers are included in the Results section.

Table 2.

Questions developed for interviews.

Table 2.

Questions developed for interviews.

| Domain |

Questions |

| Independence |

- ▪

Which design settings do you think support residents’ independent living? |

- ▪

What kind of enablers would be in the setting, or what kind of barriers, if any, can improve the design? |

| Care |

- ▪

What is the minimum and maximum level of care service that you provide? At which level of care should residents move to alternative accommodation, if ever? |

- ▪

What is the most needed care service offered to residents, and what emphasis do you put on managing the scheme? |

| Health and Safety |

- ▪

What settings would help residents keep healthy and safe, in your opinion? |

- ▪

How do residents adapt their settings to support their own physical and cognitive health? |

| Community |

- ▪

How do residents use their communal places to socialize? |

| Sense of Place |

- ▪

How do you recognize if residents develop attachment to their house? Design-wise, which element(s) can make residents like their setting, in your opinion? |

| Choice and Control |

- ▪

How does your scheme support residents’ choice and control over their environment? |

| General Satisfaction |

- ▪

Which use of space positively affects residents’ satisfaction with their settings, in your opinion? |

A thematic analysis was conducted to explore the perceptions and experiences of care managers regarding the design and operation of ECH environments. An initial inductive coding process was conducted manually through a line-by-line reading of all interview transcripts to identify recurring concepts and meaningful patterns. Based on this, a structured codebook was iteratively developed to reflect themes grounded in the data. The coding process was then supported using NVivo version 12, which facilitated systematic data organization, refinement of thematic hierarchies, and traceability of codes.

Following this inductive stage, a deductive lens was applied to align the analysis with established QoL domains frequently cited in ECH research—namely independence, autonomy, safety, social engagement, and environmental support—thereby ensuring theoretical coherence and relevance. The final coding framework comprised seven overarching categories: one specifically addressing physical design features and six corresponding to the QoL domains. These categories represent core dimensions of care and environmental quality in ECH settings and are summarized in

Table 3.

To enhance analytical rigor and enable visual interpretation, Atlas.ti version 23 was employed for advanced diagramming and conceptual network mapping. This included generating co-occurrence maps to examine how key codes, such as “autonomy”, “personalization”, and “staff responsiveness”, were interlinked across participant narratives. The software’s query tool was also used to compare thematic patterns across different scheme types and to visualize quote densities associated with specific QoL domains, offering a multidimensional perspective on the relationships between environmental design, care delivery, and resident experience.

Additionally, code concurrence analysis was used to identify thematic overlaps. This involved cross-tabulating co-occurring codes within the same textual segments and closely reviewing the corresponding quotations to assess whether participants themselves described meaningful relationships between those categories.

The combined use of NVivo and Atlas.ti strengthened the analytic process by supporting both structural consistency and conceptual depth. NVivo’s node-based framework enabled rigorous data management, while Atlas.ti’s visual mapping tools offered additional layers of interpretation. Together, these tools enriched the analysis and facilitated a more nuanced understanding of how ECH environments influence QoL.

4. Results

The results of the thematic analysis of the care managers’ interview data were structured around the eight major themes as follows:

Independence, Care, Health and Safety, Community, Sense of Place, Control and Choice, and General Satisfaction and

Mobility, Sensory and Cognitive Stimulation. The initial coding framework comprised seven overarching categories, including one category focused specifically on physical design features and six aligned with established QoL domains (

Table 3). Six of the resulting themes—Independence, Care, Health and Safety, Community, Sense of Place, and Choice and Control—were directly shaped by this initial framework. Two additional themes—General Satisfaction and Mobility, Sensory and Cognitive Stimulation—emerged inductively during iterative coding due to their conceptual coherence and frequency across interviews. Each theme captures key patterns and priorities identified by participants regarding the QoL domains related to the design and operation of ECH environments. These themes are discussed in detail in the following sections.

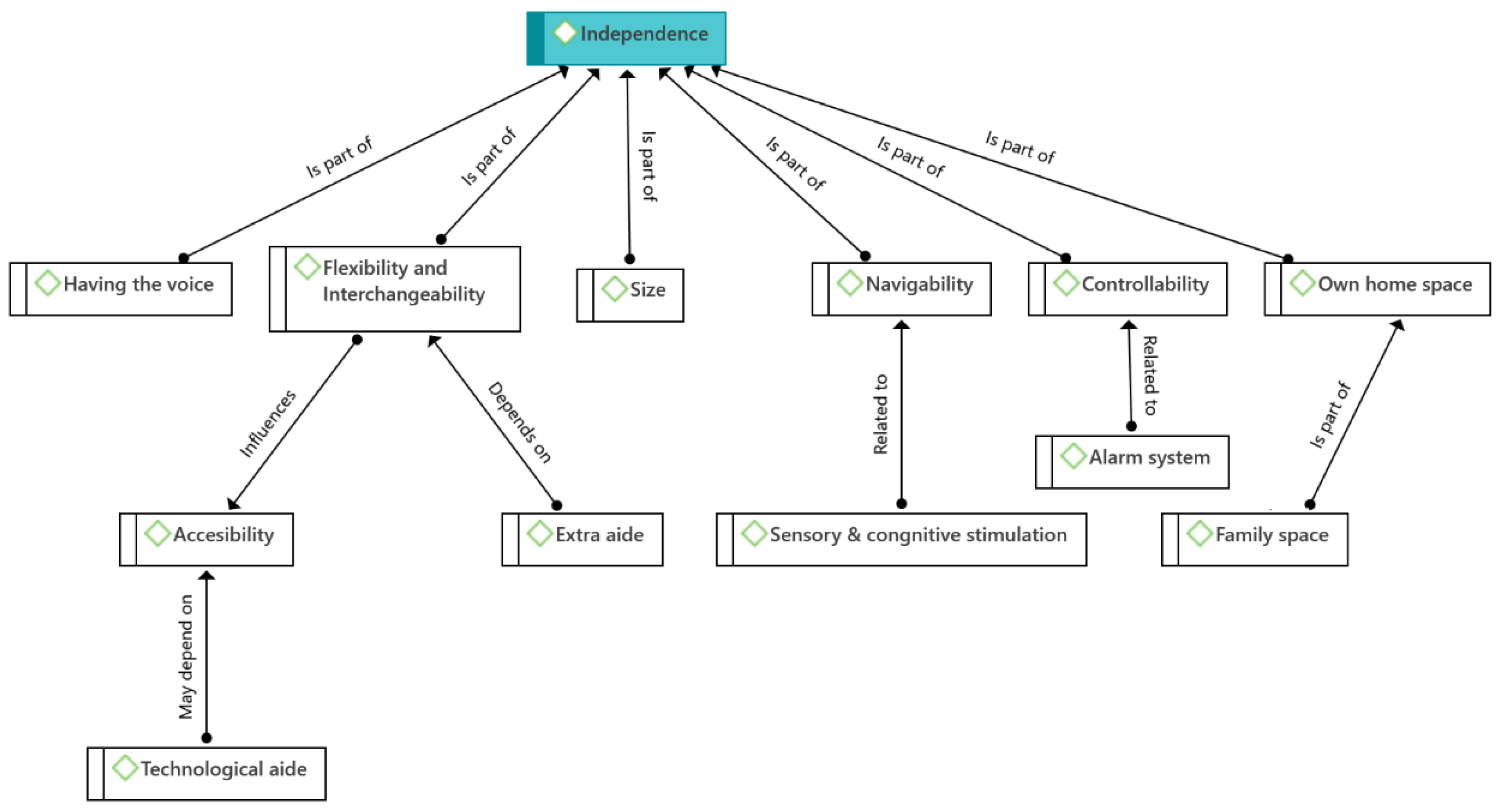

4.1. Independence

According to care managers, design settings played an important role in supporting and promoting the independent living of residents. Several relevant and interrelated sub-themes emerged in the interviews (

Figure 1). The most important were navigability, sensory and cognitive stimulation, accessibility, technological aids, flexibility, and interchangeability, all showing that the space should be flexible enough to allow for all kinds of adaptations.

Aspects of a navigable building (i.e., to help residents find their way around the building) were associated with aspects promoting sensory and cognitive stimulation; furthermore, technological aids such as mobility scooters and accessibility aspects of the building were equally important. Likewise, accessibility and not being hindered by obstacles were deemed necessary to let residents independently perform their daily activities. Extra aids were important to support older people’s independent mobility, and the space should be flexible enough to allow for this kind of adaptation (flexibility and interchangeability).

The above comments were addressed by Managers J and B as follows:

The RNIB (Royal National Institute of Blind People) is a big one because not only for sight loss but for people with dementia, so different floors will be painted in different colors and have different keys so people can identify where they are in the building if they’re on the right floor, for example (Manager J).

People can drive their mobility scooters right up to their flats and park their mobility scooters right outside their front doors, so they don’t have to walk long periods to get to their mobility scooters (Manager B).

Having their own space was seen by the managers as essential for feeling at home and remaining independent. Along with their own home space, the managers also emphasized the importance of space for family visits (family space). This was highlighted especially by Manager C:

Do you mean things like because they do come and go as they please, they have their front door? They have their friends, and family that visit. We have a couple of people that work and live here, a couple of people who drive and come and go as they please (Manager C).

As stated by Managers H and D, other sub-themes mentioned by the interviewees included the opportunities to express their opinions regarding the services provided (having a voice) and controllability, e.g., having an alarm system to inform staff in case they are in trouble.

Well, it’s all very much about choice, they tell us what they expect of the service (Manager H).

Barriers would include underfloor heating as residents find it difficult to regulate (Manager D).

Finally, having enough space (size) was mentioned by the managers as essential for older people’s moving around and performing their daily activities, which also gives residents accessibility and the feeling of freedom. In this regard, Managers H and M criticized:

The rooms aren’t as big as they could be to maybe allow them to be more independent (Manager H).

And then just making sure there’s lots of space (Manager M).

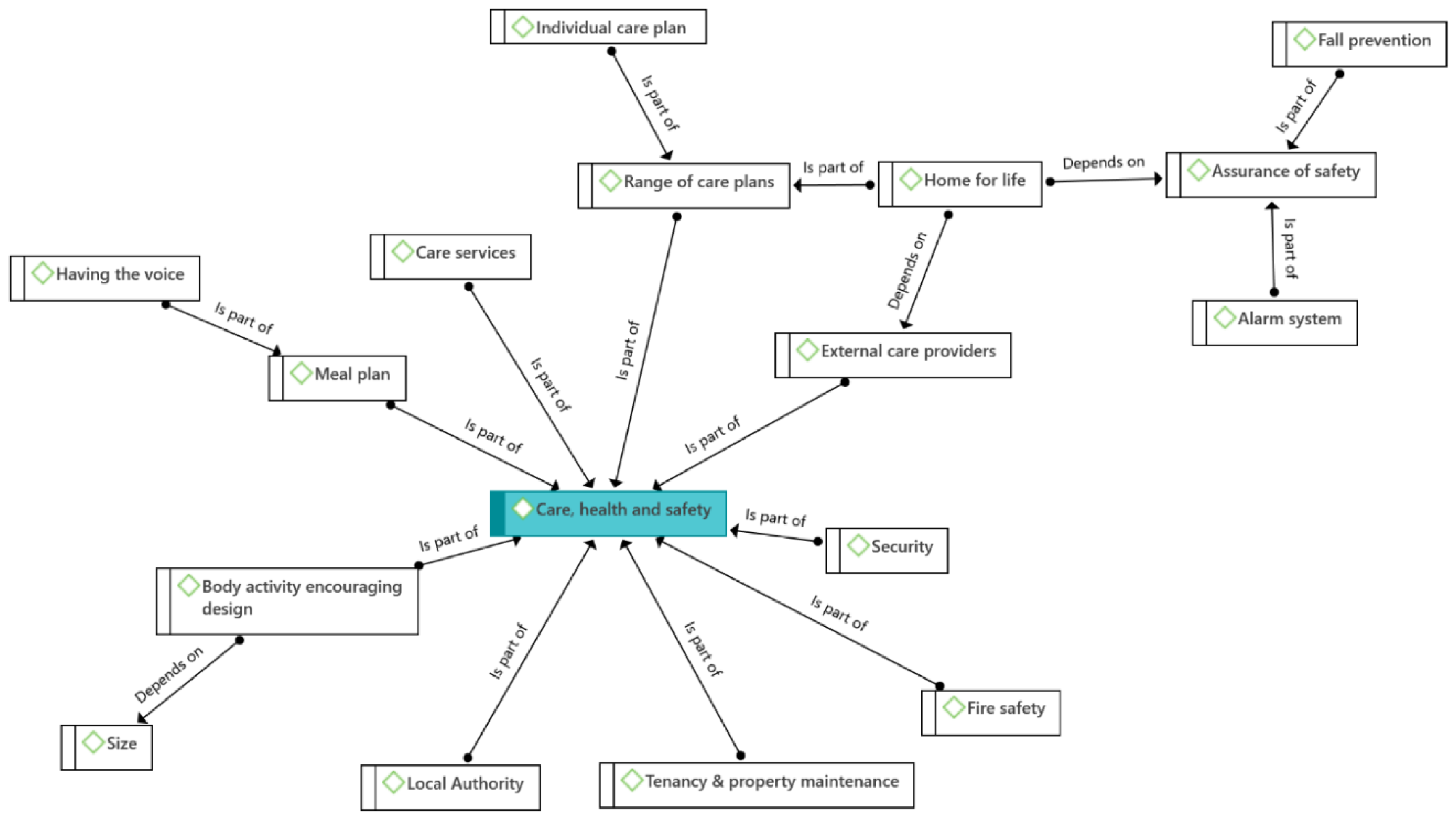

4.2. Care

The sub-themes that emerged in the analysis of the Care domain were classified into the following categories: local authority, care services, range of care plans, individual care plans, external care providers, home for life, and assurance of safety. Their interrelationships are shown in

Figure 2. The care managers also mentioned that local provision schemes in the UK are shaped by the strategies and plans of each local authority to meet housing needs. Accordingly, ECH schemes, especially public ones, typically follow their local authorities’ regulations, as was indicated by Managers A and F.

So, the minimum is five hours per week and we work closely in line and our contract is with Bristol City Council. So, the way the council works there is a minimum of five hours of care you need to be eligible (Manager A).

The maximum here depends on the local authority so Lime Tree House is under the Southwark Council local authority so their maximum is above 15 h (Manager F).

However, if older people need a care plan lasting under 24 h a day, they can pay privately, since care in the UK is described as a quasi-market. This information was classified within the code of external care providers. Furthermore, since ECH providers are not qualified for all care needs, i.e., medical assistance, relevant schemes receive support from external professionals such as health professionals and district nurses. The following statements by Manager A showed the above situation.

We do have private care contracts. We do have people privately pay and if that’s the case then they can change their care plan within 24 h so as long as we can facilitate it with staffing needs (Manager A).

No so we just have carers here so when it comes to the health care professionals, they’re usually external (Manager A).

To be eligible to move into the ECH environment, publicly funded residents should have care needs of at least a certain number of hours a week. The interviewees pointed out a great variety of care plans (range of care plans) that not only consider the number of care hours but also consider how different plans can be adapted to specific care needs. As part of this range of plans, the sub-theme of individual care plans emerged as well, as highlighted by Managers A and B.

So, we’ve got a very, very big range of people. Some appear to be very able and others when you look at them, they’ve got physical disabilities, but we help in all sorts of ways. So, there isn’t anything specific because we have such a big range of people (Manager A).

Ok, so the minimum requirement now for people moving in now is five hours of care. That’s personal care or support with household duties, flat cleaning, laundry, shopping, supporting someone with shopping things like that. And then I’ve got one of my tenants here she’s 72 nearly 73 h of care a week so a very, very high package of care (Manager B)

The care managers noted that the ECH environment is intended to be the final place of residence for older people, so the key objectives are that residents do not have to make another transition, remain independent for a longer period, and do not go into institutionalized care. Considering these goals, two central sub-themes that emerged in the interview data were the existence of external care providers, as external support is vital in ECH schemes, and older people’s condition (i.e., advanced dementia, health decline). Regarding the management of care services, the managers underscored the importance of implementing older people’s care plans based on their specific needs. This was addressed by Managers C and E as follows:

… hopefully, this will be their forever home but depending on the people every individual and their deterioration of whatever condition they’ve got if we don’t think that’s a safe environment then we will look at that (Manager C).

So, my priority is personal care in our scheme. Everything we do is important but the personal care and looking after them with an individual support plan for their individual needs is the most important thing (Manager E).

The results of the thematic analysis revealed that, within the theme of Care, Health, and Safety, care managers noted care services, local authority policies, meal plans (which is further related to the sub-theme of residents’ having a voice), external care providers (which includes an individual care plan) and range of care plans, including being a home for life, which depends on the existence of the assurance of safety and of external care providers. The sub-themes of fall prevention and alarm systems emerged as parts of assurance of safety. Tenancy and property maintenance, fire safety, and security of the building were noted as factors providing residents’ safety, whereas body activity-encouraging design, which was considered to depend on size (i.e., enough space), was noted as an important sub-theme related to residents’ health.

4.3. Health and Safety

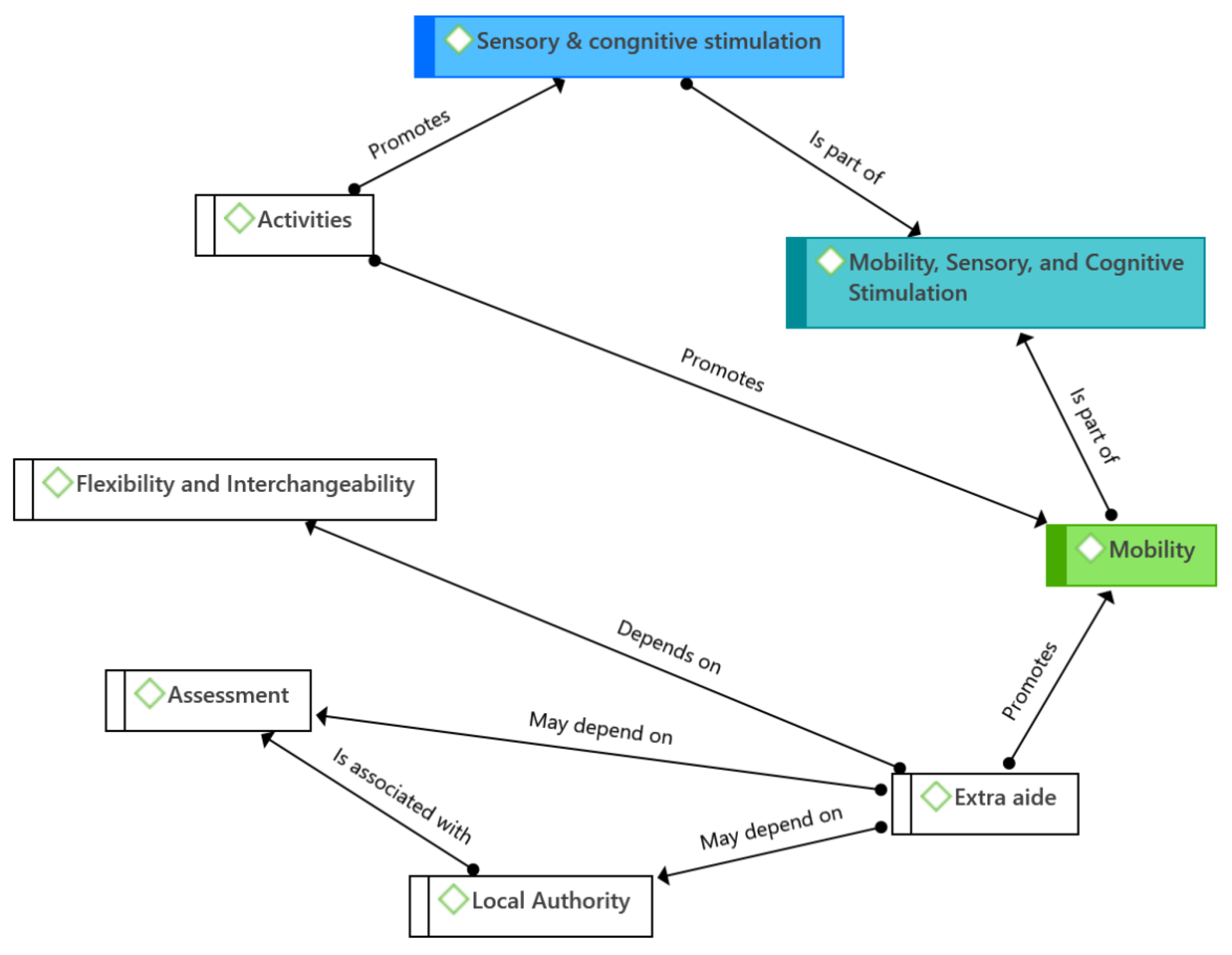

The results revealed that Health and Safety split into two key sub-themes: mobility, and sensory and cognitive stimulation (

Figure 3). Regarding mobility, the managers mentioned common safety aspects for management such as alarm systems, fire safety elements, and fall prevention. Another aspect considered important was tenancy and property maintenance for residents’ security. In this regard, Managers D and C highlighted:

The schemes are secure both internally and externally, including fire alarms, smoke detectors in each flat, and sprinkler systems. The main doors are locked at night with the use of an intercom system and a waking night member of staff on site. The schemes have CCTV (Manager D).

But also, the other string to that bow is that because you are running a building with independent flats you are a landlord as well so you have to deal with tenancy issues, property issues, maintenance, kind of any financial arrears that may come up (Manager C).

Along with safety considerations, several sub-themes related to residents’ health also emerged in the data analysis. Healthy meals are important and were coded as planned meals, which were noted by several care managers. For example, Managers F and H mentioned below their efforts to provide residents with healthy meals; however, they also pointed out that residents’ opinions are important because they finally decide what they want to eat, i.e., they have a voice. Other health-related sub-themes included body-activity-encouraging design and size of the building. The care managers also highlighted the importance of activities to stimulate residents and make them feel part of the community.

We can only advise them we can’t tell them what to eat, it’s their choice it’s whatever they want to buy, they buy for them (Manager F).

The meals are regulated the catering manager has some sort of a scoring mechanism that ensures all the meals have all the proper nutrients (Manager H).

4.4. Mobility, Sensory and Cognitive Stimulation

One sub-theme that emerged in the analysis was the existence of extra aids, suggesting that, when people become older, they frequently lose mobility and can develop disabilities. As mentioned by Managers F and A (see below), such aids might not be necessarily present when residents move to ECH settings and may be installed afterward. In this sense, the possibility of adaptation is essential (the sub-theme of flexibility and interchangeability): if the installation of extra aids becomes necessary, this space should be flexible enough to allow these changes. These changes also may depend on assessments from local authorities, which may be responsible for these adaptations in the case when people are not able to fund them on their own. On the other hand, the sub-theme of activities was noted as important in terms of promoting sensory and cognitive stimulation. All aforementioned relationships are depicted in

Figure 3.

The adaptation is not a total change so you can either have maybe handrails installed in the bathroom, or in the kitchen for residents to hold onto. Or the one that we adapted is lowering the kitchen units so that someone who is in a wheelchair that can still use her hand very well can have access (Manager F).

No, the flats are just standard, but they’re adapted so the doors are wheelchair accessible. Everything is wheelchair-accessible here (Manager A).

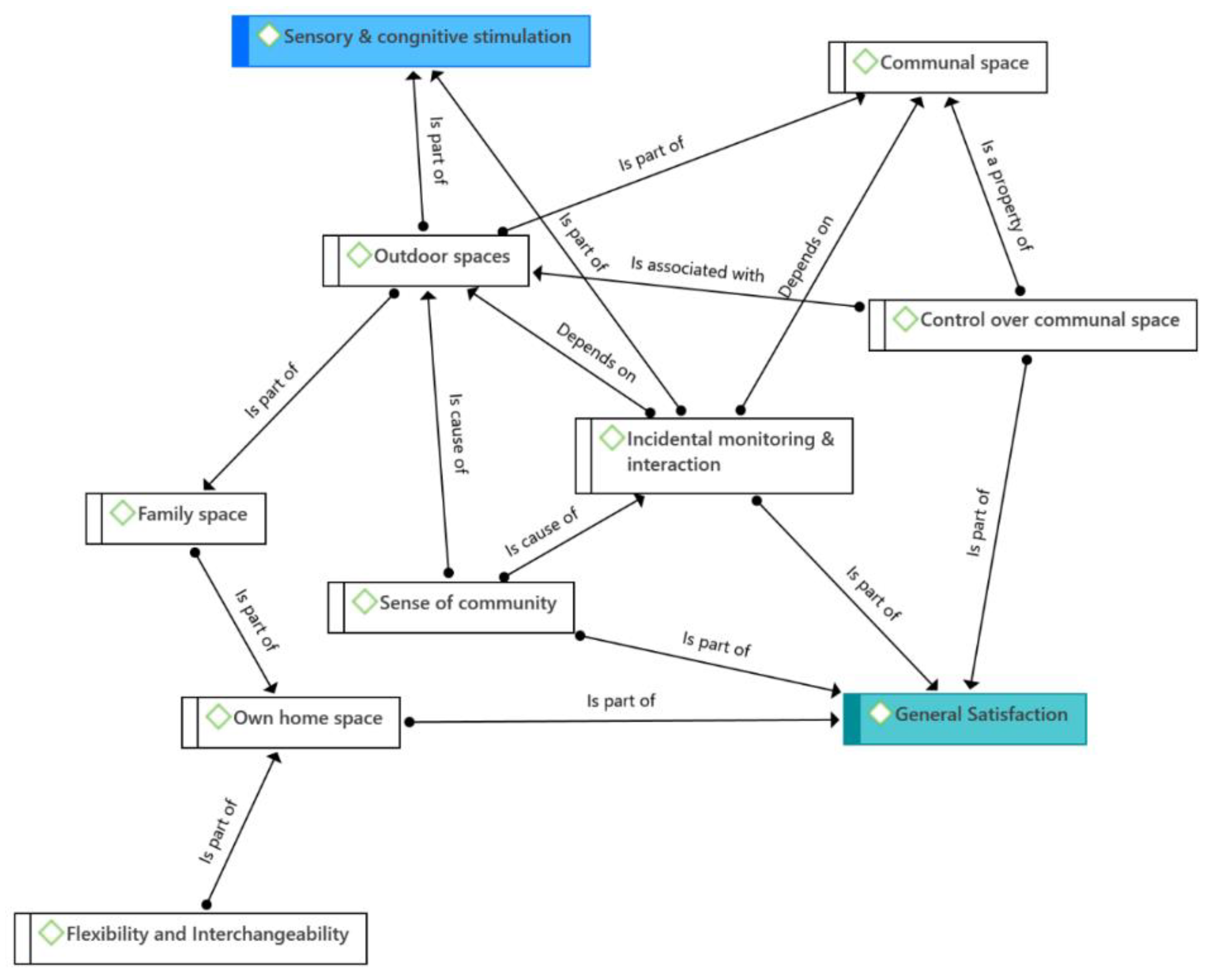

4.5. Community

The results revealed that the managers observed that the domain Community is interrelated with Sense of Place (

Figure 4). Care managers’ perspectives on Community can be summarized as the use of communal areas for activities and socialization which included lounges and restaurants. Similarly, the activities showed great importance not only because they can provide a sense of community, but also because they promote sensory and cognitive stimulation. Outdoor spaces were also mentioned as important components of socialization and activities. In this case, Managers L and C mentioned:

And it’s crazy- some people as you know have big families, family visits they don’t need anything else but some people who haven’t got that they like the stimulation of sitting chatting to other people (Manager L).

We’ve got lots of communal areas, a lounge, a library, a quiet room, a big restaurant, an atrium, and a foyer that’s normally filled with staff. We’ve got hairdressers so yeah quite a big space and there’re lots of friendship groups within this, it’s very much communal living it’s quite nice (Manager C).

The managers also noted the importance of residents’ integration with the local community where the key sub-themes were communal areas, outdoor spaces, activities, and integration with the community. For example, Manager B stated:

… then we have the community come in as well to join in some of our activities (Manager B).

4.6. Sense of Place

Two key sub-themes related to the sense of place mentioned by the care managers were having their own home space and the possibility of personalizing their flat (flexibility of space and use). The flats were given to them unfurnished, so they could bring their furniture and things to decorate their own spaces, which created a homely interior providing comfort, confidence, and freedom. This was explained by Managers C and L.

That’s very lucky for us because it’s very evident as soon as they get here that it’s their front door and their property. It’s their flat so they can do with it what they want, decorate it as they want, and put their stamp on it (Manager C).

Where they can feel relaxed and can make friends (Manager L).

4.7. Choice and Control

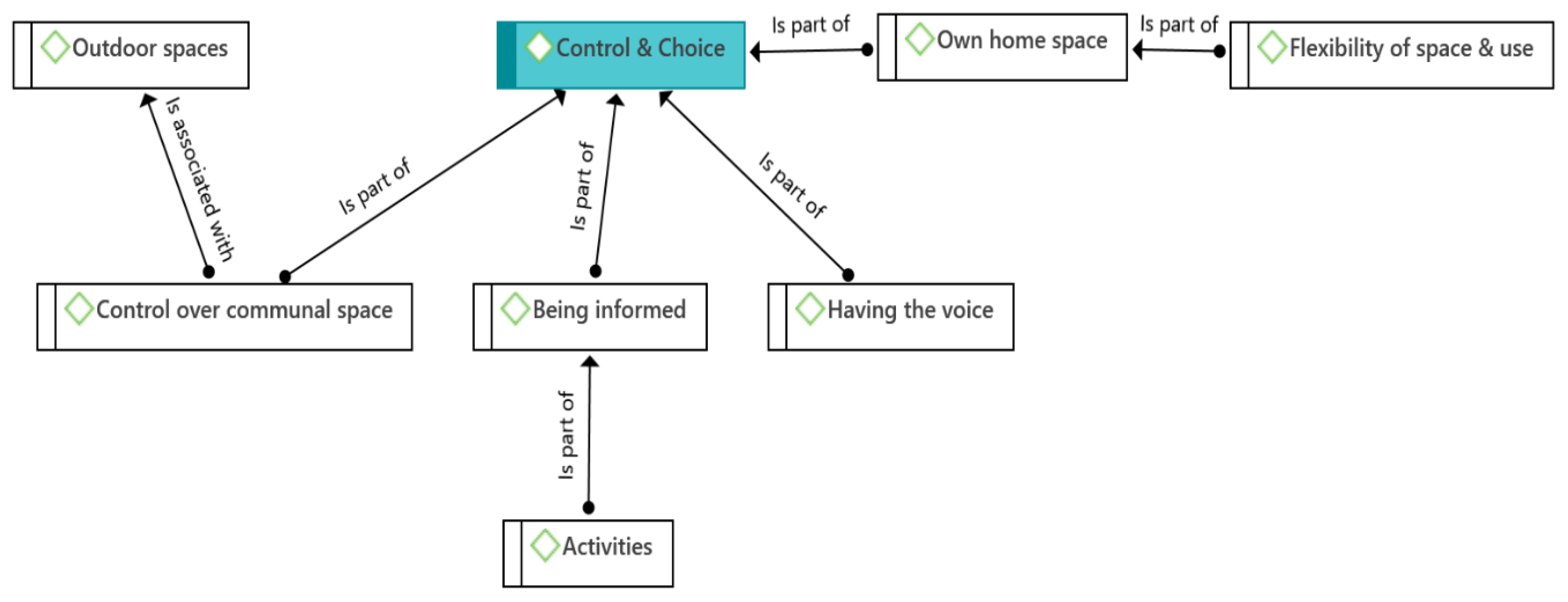

Seven sub-themes for Choice and Control emerged from the analysis: Own home space; Control over communal spaces; Flexibility of space and use; Outdoor spaces; Being informed; Having the choice; Activities.

The most important were (i) Own home space, related to the availability and flexibility to use and adapt it to their needs, and (ii) control over communal spaces, which was important to maintain older people

’s independence. Overall, an important part of maintaining older people

’s independent living is their ability to control their own personal space. However, this control is not limited to personal spaces. Rather, older residents also need to have some control over communal areas and be involved in making consensual decisions about their use (

Figure 6). This was briefly explained by Managers C and F as follows.

I suppose because it is again since it’s their front door, their flats, they’re very much a part of their initial setup, their care plan when it’s put in place (Manager C).

The lounge belongs to them, the garden belongs to them, and the laundry service we have a launderette belongs to them so they can tell us exactly how they want to use it (Manager F).

Furthermore, older people’s control over both their own and communal spaces also require the ability to communicate their concerns to the manager through surveys and meetings (having a voice). During the interviews, the managers indicated that residents needed to have an opportunity to discuss issues around their living environment. All ECH schemes in the UK are currently conducting regular surveys of their residents’ opinions, and residents are also invited to become involved in the decision-making processes about their living environment. On the other hand, residents like to be informed about the news in their ECH. Accordingly, some of the managers mentioned keeping their residents informed about everything they were doing, including daily activities, and they allowed their residents to choose. The interviewees were aware of the positive impact of activities on the psychological well-being and life satisfaction of residents and tried to promote older people’s activities by allowing them to have appropriate information and by encouraging them to become involved, as highlighted by Managers B and N below.

But most of the time—I mean our tenants, we’ve got satisfaction surveys and we ask them about their surroundings, lighting, and food. They have—the tenants have the voice. So we have tenants’ meetings, when we were allowed, so we have tenants’ meetings where they could voice their feelings and bring up anything in the agendas. But our door is always open so our tenants are quite able to come down to the office and have a chat with us if they’re not happy with anything. Or if they’re happy with things, they’re very much into raising money for the scheme (Manager B).

It’s keeping our customers updated on what we’re doing and then giving them a choice (Manager N).

Figure 5.

Codes related to control and choice.

Figure 5.

Codes related to control and choice.

Figure 6.

Codes related to general satisfaction.

Figure 6.

Codes related to general satisfaction.

4.8. General Satisfaction

Overall, thematic analysis of the data revealed the following two key aspects: First, the feeling of home produced by older residents’ having their own home spaces. According to the managers, older people enjoy having their own space, such as a balcony, bedroom, or kitchen, among others, which they can use and customize according to their needs (flexibility of space and use). In addition, residents need familiar spaces such as the guest room provided by ECH as part of their own space (

Figure 6), as stressed by Managers D and H.

I think a lot of them do like their flats and at the moment they’re spending most of their time inside the flats (Manager D).

Well to tell you the truth quite a few of them are more than happy to stay in their rooms but they do use mealtimes as a socializing experience, we don’t rush them with their meals to go down at half 12 and most of them aren’t leaving the dining room until around 2 o’clock (Manager H).

Secondly, the sense of community which, according to, among others, Managers D and K, was one of the most important aspects of overall resident satisfaction, as older people love being able to interact with others. Similarly, the managers noted that the key aspects to developing this sense of community include natural interactions among residents in communal spaces, especially outdoor spaces such as gardens, lounges, and restaurants.

Having their own flat, privacy, and own space, however, have the choice to use communal areas if they wish (Manager D).

Of course, we wouldn’t force them to come down. But we try to encourage people to use the restaurant space, it means they get to socialize with people. So, I would say the restaurant (Manager K).

5. Discussion

The main objective of this study was to investigate how housing schemes, combining independent living with high levels of care, address the needs of the ageing population in the UK. The results of the thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews conducted with 14 care managers working in ECH services are reported. As stated earlier in this paper, the main domains were drawn from a recent scoping review on optimal design for ECH environments [

7] and are discussed below, regarding whether the findings agree or contrast with previous research.

5.1. Independence

Design settings played an important role in supporting and promoting the independent living of residents with the sub-themes of navigability, controllability, own home, communal space, and incidental interactions emerging in the group of respondents. These observations are consistent with the literature emphasizing the value of spatial autonomy and flexible environments for older adults [

11,

16]. Having their own space was essential for feeling at home and remaining independent, performing their daily activities, and feeling of freedom. Along with their own home space, the importance of space for family visits was emphasized.

5.2. Care

The results revealed that local administrations determine costs, delivery models, care, and support contracts for ECH. This evaluation is based on an analysis of the needs of the local population and the experiences of residents and staff. This reflects findings that local variation in policies and funding structures can significantly shape the care experience in ECH schemes [

9]. While the literature highlights the need for consistency in care delivery [

26], our findings show that flexibility in care planning exists through private arrangements and tailored support services. This reinforces the need for both structural and individual adaptability to meet diverse care needs in ECH.

5.3. Health and Safety

Care managers emphasized health issues such as security and fire safety. This domain was split into mobility and sensory and cognitive stimulation. These findings align with concerns noted regarding increased injury risks due to sensory decline in older adults [

22]. Regarding mobility, common safety aspects such as alarm systems, fire safety, and fall prevention were highlighted. The existence of extra aids, when residents lose mobility and develop disabilities, should be installed afterwards. It is essential to the possibility of adaptation by flexibility and interchangeability. The need for environmental adaptability, including the provision of extra aids and design flexibility, aligns with the argument that evidence-based design should address evolving residents’ needs [

32].

5.4. Community

The domain was largely predetermined by the socialization in communal areas such as lounges and restaurants although the connection with the outside world was also noted. The results revealed connections with Sense of Place. The activities showed great importance because they provide a sense of community and promote sensory and cognitive stimulation. These observations support earlier work on the importance of socialization in reducing loneliness and promoting well-being [

23,

24]. Outdoor spaces were also mentioned as important components of socialization and activities; this recognition aligns with findings that access to nature and communal areas contributes to residents’ satisfaction and engagement [

29].

5.5. Sense of Place

Two key sub-themes related to the sense of place mentioned by the care managers were having their own home space and the possibility to personalize their flat (flexibility of space and use). The flats were given to them unfurnished, so they could bring their furniture and things to decorate their own spaces, which created a homely interior providing comfort, confidence, and freedom. These findings confirm the importance of place attachment described in the literature, which contributes to psychological well-being and reduces stress [

8]. The ability to personalize space supports a sense of ownership and identity, consistent with findings from previous studies [

30,

31].

5.6. Choice and Control

Several important sub-themes were recognized. Own home space should be available and flexible to use and adapt to the residents’ needs to feel a sense of home and control over communal spaces to maintain older people’s independence. An important part of maintaining older people’s independence is their ability to control their own personal space. Having their own home space and control over communal spaces allowed residents to maintain independence, consistent with previous findings on perceived control in care settings [

26,

27]. Older people’s control over their own communal spaces requires the ability to communicate their concerns to the managers. Surveys of residents’ opinions are essential to participate in the decision-making process about their living environment. On the other hand, residents like to be informed about the news in their ECH. There is a positive impact of activities on the psychological well-being and life satisfaction of residents.

5.7. Mobility, Sensory and Cognitive Stimulation

This study identified

Mobility, Sensory and Cognitive Stimulation as a distinct thematic category, underscoring that optimal housing environments should not only prioritize safety but also actively support physical movement, sensory enrichment, and cognitive vitality. Care managers emphasized that design features such as accessible pathways, clear sightlines, outdoor exposure, diverse textures, and engaging visual elements significantly enhanced residents’ daily experiences. Such sensory-rich spaces and opportunities for cognitive stimulation were noted to positively influence mood, autonomy, and overall alertness, echoing previous research linking environmental stimulation with improved emotional well-being and slower functional decline [

22,

31]. Additionally, findings revealed that cognitive engagement was facilitated both actively, through structured activities, and passively, via spatial design elements, such as intuitive navigation, visual interest, daylight variability, and proximity to communal areas. These insights suggest that proactive environmental interventions can substantially enhance residents’ quality of life, extending the role of physical design beyond conventional safety concerns.

Given these considerations, it is recommended that ECH policies and design guidelines explicitly integrate strategies supporting mobility, sensory engagement, and cognitive stimulation. This approach includes incorporating therapeutic landscapes, dynamic lighting schemes, tactile diversity, and clearly navigable spaces. Emphasizing this distinct domain promotes a more comprehensive, evidence-based strategy for aging-in-place, aligning environmental design directly with broader health and quality-of-life outcomes.

5.8. General Satisfaction

The thematic analysis revealed the feeling of home experienced by older residents’ having their own home spaces. Older people enjoy having their own balcony, bedroom, or kitchen, which they can use and customize according to their needs. Additionally, residents need a guest room for family visits. The sense of community was one of the most important aspects of overall resident satisfaction, as older people love being able to interact with others. The key aspects to developing this sense of community include natural interactions among residents in gardens, lounges, and restaurants. These findings echo the importance of environmental comfort and design in enhancing satisfaction [

28]. In addition, natural interactions and social opportunities in shared areas such as gardens and restaurants contributed significantly to residents’ life satisfaction [

26].

Finally, in the domains of independence, choice and control, and sense of place, the interviewed perspectives largely overlapped with the sub-themes of navigability, controllability, own home, communal space, and incidental interactions. Thematic analysis revealed that general satisfaction was closely related to sense of place, independence, and control and choice.

Care managers also noted signs of deterioration in some ECH schemes, highlighting challenges in maintaining quality standards over time. This study, along with future research in this area, may help inform strategies to address these concerns and support the continued development and improvement of ECH environments in the UK.

5.9. Limitations and Future Research

While this study offers valuable insights into how ECH environments are perceived by care managers, it is not without limitations. The focus on managerial perspectives provides a strategic and operational lens but excludes the lived experiences of residents themselves. Including residents’ voices could yield a richer and more nuanced understanding of how physical and social environments shape quality of life. Additionally, while the sample was diverse in terms of provider type and scheme size, it was geographically confined to the UK, and findings may not be directly transferable to other cultural or policy contexts. Future research could adopt a multi-perspective approach that incorporates residents, frontline care workers, and family members to capture the full ecosystem of supported housing experiences.

6. Conclusions

This study explored the perspectives of care managers on ECH environments in the UK, focusing on their role in addressing the needs of older residents. Through thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews, key themes emerged related to independence, care, health and safety, community, sense of place, choice and control, general satisfaction and mobility, sensory and cognitive stimulation. The findings highlight the importance of a well-designed and adaptable physical environment in promoting older residents’ autonomy and quality of life.

The results suggest that ECH schemes provide a viable alternative to institutional care by enabling older individuals to maintain independence while receiving necessary support. However, this study also revealed challenges, such as the deteriorating conditions of some ECH facilities, inconsistencies in local authority policies, and the need for greater flexibility in care provisions. Care managers emphasized the significance of resident participation in decision-making, personalized care planning, and the integration of social and recreational opportunities to foster a sense of community and well-being. By foregrounding the perspectives of care managers—who operate at the intersection of space, service, and resident experience—this study offers practical insights for housing operators, architects, and policymakers. A more integrated approach that explicitly includes design for cognitive and sensory stimulation could significantly enhance the daily life and long-term well-being of aging populations.

This study contributes to the growing body of the literature on housing and care by amplifying the perspectives of care managers, who play a crucial role in the successful operation and QoL in ECH facilities. Their insights emphasize the importance of EBD principles in informing future ECH development. Specifically, design strategies that incorporate adaptable spatial layouts, enable physical and cognitive engagement, and strengthen connections to the broader community are better positioned to meet residents’ evolving needs over time.

At the same time, addressing persistent structural challenges—such as fragmented funding mechanisms, staffing limitations, and inconsistent regulatory frameworks—is essential to sustaining the operational and strategic success of these environments. While this study offers an important contribution by centering the voices of care managers, future research should integrate the perspectives of residents themselves to further enhance understanding and inform more holistic policy and design strategies. Future research should explore the perspectives of residents and policymakers to create a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges and opportunities in ECH settings. Longitudinal studies are also needed to assess the long-term impact of design interventions and policy changes on the quality of life of older residents.

By implementing the insights from care managers and integrating evidence-based design strategies, ECH schemes can evolve into more responsive, inclusive, person-centered living environments that truly support aging in place.

Author Contributions

Writing – original draft, S.J.; Supervision, K.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Sheffield (approval code 032209, date on 28 January 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

You can refer following:

Data available in a publicly accessible repository

The original data presented in the study are openly available in [repository name, e.g., FigShare] at [DOI/URL] or [reference/accession number].

Data available on request due to restrictions (e.g., privacy, legal or ethical reasons)

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to (specify the reason for the restriction)

3rd Party Data

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data were obtained from [third party] and are available [from the authors/at URL] with the permission of [third party].

Restrictions apply to the datasets

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because [include reason, e.g., the data are part of an ongoing study or due to technical/ time limitations]. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to [text input].

Data derived from public domain resources

The data presented in this study are available in [repository name] at [URL/DOI], reference number [reference number]. These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: [list resources and URLs]

Data sharing is not applicable (only appropriate if no new data is generated or the article describes entirely theoretical research

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s

Dataset available on request from the authors

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ECH |

Extra Care Housing |

| QoL |

Quality of Life |

| AL |

Assisted Living |

| EBD |

Evidence-Based Design |

| WHOQOL |

World Health Organization’s QoL instruments |

| RNIB |

Royal National Institute of Blind people |

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Ageing 2020 Highlights: Living Arrangements of Older Persons; United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020.

- Housing Learning and Improvement Network (Housing LIN). Extra Care Housing: What is it? 2017. Available online: https://www.housinglin.org.uk (accessed on).

- Darton, R.; Callaghan, L. The role of extra care housing in supporting people with dementia: Early findings from the PSSRU evaluation of extra care housing. J. Care Serv. Manag. 2009, 3, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.B.; Christensen, V.T.; Heinesen, E. The effect of home care on the ability to perform the activities of daily living and the well-being of older people. Eur. J. Ageing 2009, 6, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sixsmith, A.; Sixsmith, J. Ageing in place in the United Kingdom. Ageing Int. 2008, 32, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peace, S.; Holland, C.; Kellaher, L. Environment and Identity in Later Life; Open University Press: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Burack, O.R.; Weiner, A.S.; Reinhardt, J.P.; Annunziato, R.A. What matters most to nursing home elders: Quality of life in the nursing home. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2012, 13, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croucher, K.; Hicks, L.; Bevan, M.; Serson, D. Comparative Evaluation of Models of Housing with Care for Later Life; Joseph Rowntree Foundation: York, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Steenwinkel, I.; Aarts, M.P.J.; Schifferstein, H.N.J. Visibility and signs of activity support perception of the social environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 49, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, J.A.; de Joux, V.; Nana, G.; Arcus, M. Accommodation Options for Older People in Aotearoa/New Zealand; Centre for Housing Research Aotearoa/New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2004; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kingston, A.; Comas-Herrera, A.; Jagger, C. Forecasting the care needs of the older population in England over the next 20 years: Estimates from the Population Ageing and Care Simulation (PACSim) modelling study. Lancet Public Health 2018, 3, e447–e455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. Overview of Japan’s Serviced Housing for Elderly People; MLIT: Tokyo, Japan, 2015.

- Zimmerman, S.; Sloane, P.D.; Williams, C.S.; Reed, P.S.; Preisser, J.S.; Eckert, J.K.; Boustani, M.; Dobbs, D. Dementia care and quality of life in assisted living and nursing homes. Gerontologist 2005, 45 (Suppl. 1), 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judd, B.; Olsberg, D.; Quinn, J.; Groenhart, L.; Demirbilek, O. Dwelling, Land and Neighbourhood Use by Older Home Owners; AHURI Final Report No. 144; Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute: Melbourne, Australian, 2010.

- Wiles, J.L.; Leibing, A.; Guberman, N.; Reeve, J.; Allen, R.E. The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krothe, J.S. Promoting functional independence in the elderly: Strategies for community health nursing. Public Health Nurs. 1997, 14, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Anton, C.E.; Lawrence, C. Home is where the heart is: The effect of place of residence on place attachment and community participation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, R.L.; Parmelee, P.A. Attachment to place and the representation of the life course by the elderly. In Place Attachment; Altman, I., Low, S.M., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; pp. 139–163. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson, M.; Andersson, E. Changing preferences with aging-housing choices and housing plans of older people. Hous. Theory Soc. 2015, 33, 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statistics. Health State Life Expectancies, UK: 2016 to 2018. Office for National Statistics. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Gopinath, B.; Schneider, J.; Hartley, D.; Teber, E.; McMahon, C.M.; Mitchell, P. Combined hearing and vision impairment is associated with poorer quality of life and increased risk of depression in older adults. Age Ageing 2016, 45, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharicha, K.; Iliffe, S.; Manthorpe, J.; Chew-Graham, C.A.; Cattan, M.; Goodman, C.; Kirby-Barr, M.; Whitehouse, J.H.; Walters, K. What do older people experiencing loneliness think about primary care or community-based interventions to reduce loneliness? A qualitative study in England. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruggencate, T.T.; Luijkx, K.G.; Sturm, J. Social needs of older people: A systematic literature review. Ageing Soc. 2018, 38, 1745–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimki, M.; Batty, G.D.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Ferrie, J.E.; Tabk, A.G.; Jokela, M.; Virtanen, M. Association of socioeconomic status with premature mortality in high-income countries: A meta-analysis. JAMA 2020, 323, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, L.; Towers, A.M. Feeling in control: Comparing older people’s experiences in different care settings. Ageing Soc. 2014, 34, 1427–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, L.; Quine, S. Common factors that enhance the quality of life for women living in their own homes or aged care facilities. J. Women Aging 2012, 24, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, E.; Sheehan, B. Care-home environments and well-being: Identifying the design features that most affect older residents. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2010, 27, 237–256. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43030908 (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Rodiek, S.D.; Fried, J.T. Access to the outdoors: Using photographic comparison to assess preferences of assisted living residents. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 73, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund-Snodgrass, L.; Nord, C. The continuation of dwelling: Safety as a situated effect of multi-actor interactions within extra-care housing in Sweden. J. Hous. Elder. 2019, 33, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrell, A.; McKee, K.; Torrington, J.; Barnes, S. The relationship between building design and residents’ quality of life in extra care housing schemes. Health Place 2013, 21, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vischer, J.C. Applying knowledge on building performance: From evidence to intelligence. Intell. Build. Int. 2009, 1, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, T. Semi-Structured Interview|Definition, Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Available online: https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/semi-structured-interview/ (accessed on 5 May 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).