1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the fragility of long-term care systems worldwide, particularly in care facilities for older people. After the devastating mortality rates, the issue of care has been brought to the center of public and political debate, accelerating a shift away from institutional models towards community-based, person-centered care (PCC) typologies [

1]. Spain illustrates this trend: with more than 45,000 deaths in care facilities during the pandemic [

2], reforms are underway to promote small-scale, PCC-oriented environments [

3].

Yet, despite the profound impact that architecture has on older people, especially those with functional and cognitive decline [

4,

5], architecture has played a secondary role in the implementation of innovative care typologies. The transition towards a PCC model has been largely driven by healthcare fields, such as gerontology and sociology [

1,

6,

7]. By contrast, architectural research has tended to focus on alternative housing options [

8,

9] paying less attention to the renovation of existing care facilities [

10]. As a result, efforts to implement more humanized care are hampered by standardized architectural spaces, which undermine autonomy, privacy, social interaction, and the overall well-being of residents, staff, and families [

11].

This gap between care practice and architectural design stems from a canonical understanding of architecture as a technical, author-centered discipline, historically embodied in the figure of the male architect [

12]. However, more recent approaches in architecture—such as gender perspective [

13], inclusive design [

14], or holistic sustainability [

15]—are calling for a transformation of the role of architecture: no longer as an isolated practice, but as a caring activity, committed to collective well-being and the climate crisis. In this regard,

caring architecture represents an alternative vision that challenges the hegemonic perspective. This approach, grounded in feminist care ethics [

16,

17,

18,

19], has significantly developed in recent years thanks to feminist architects and urbanists such as Brittany Utting [

20], Juliet Davis [

21], and Angelika Fitz and Elke Krasny [

22]. In Spain, Blanca Valdivia [

21] and Izaskun Chinchilla [

23] stand out among the leading voices.

In this context, the aim of this paper is to conduct a critical analysis of the main theoretical approaches to caring architecture, identifying key references, concepts, and principles that define this emerging perspective. Additionally, it seeks to offer an ethical framework to guide the transition from institutional care facilities for older adults to PCC-oriented architectural spaces that care for its users and the environment.

To this end, a systematic review of Spanish and international literature exploring caring architecture has been conducted. Eight key works were selected for in-depth analysis through bibliometric, conceptual, and thematic methods. The bibliometric analysis classified references by discipline, while a genealogical exploration of feminist care ethics identified three core concepts of care: interdependence, economics of care, and eco-dependence. These concepts structured the conceptual and thematic analyses and were linked to the dimensions of sustainability: sociocultural (interdependence), economic (economics of care), and environmental (eco-dependence). Furthermore, the growing interest in caring architecture in Spain has been especially influenced by feminist perspectives, which frame care as a social, political, and spatial issue. For this reason, this study first revisits the concept of care in feminist theory and architecture, establishing the theoretical basis of the analysis.

1.1. Care and Feminist Theory

From the perspective of gender studies,

care encompasses all interdependent, eco-dependent, and collective activities and practices that ‘sustain life’ [

24,

25]. The concept of

economics of care, linked to feminist economics [

26,

27], involves theoretical and empirical approaches that criticize gender inequalities in caregiving roles due to the sexual division of labor.

Teresa del Valle [

28] argues that understanding care as a right is necessary for caring practices to become a sociopolitical responsibility. Accordingly, Amaia Pérez Orozco [

29] establishes four dimensions of the

right to care: the right to receive care, the right to choose whether or not to provide care, the right to fair and decent labor conditions in care work, and the right to refuse inappropriate care. Care practices can also be organized into

circles of care, including (1) self-care; (2) direct care of others—feeding, caring for a dependent or ill person; (3) provision of the preconditions for these activities, also called indirect care—domestic tasks such as cleaning, shopping, and cooking; and (4) care management—coordination of schedules, transport, supervision, etc. [

30] (pp. 70-74) [

31] (p. 36). Ecofeminist authors incorporate global environmental care as the last circle in the scale of care [

32].

Despite the consolidated framework of care developed within gender studies, feminist care ethics has gained increasing relevance after the COVID-19 pandemic [

33,

34]. Situated between feminist theory and moral philosophy, this perspective critiques the invisibilization of caregiving roles—assigned to vulnerable groups and lower classes—in contrast to productive and managerial tasks performed by those who control power structures. This theoretical approach seeks to revalue the principles associated with care—interdependence, relationality, responsibility, empathy, etc.—by transforming them into democratic moral foundations to guide social policies [

35].

Feminist care ethics is framed as a critique of the neoliberal model, dominant in philosophy, economics, and institutional policies of Western states. In this patriarchal system, based on values such as individualism, privatization, and deregulation, caring is considered a weakness, a domestic activity, a female disposition [

19]. The ethics of justice within neoliberalism prioritizes an able, autonomous individual who is neither a caregiver nor in need of care [

17,

19]. Conversely, feminist ethics of care recognizes “dependency as a central and inevitable aspect of human life” [

36] (p. 215). This entails moving away from the right to autonomy promoted by rationalist political theories in favor of the right to care [

19].

1.2. Care and Architecture

The development of social awareness around care, driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, has also sparked growing interest in architecture. The study of the relationship between feminist care ethics, architecture, and urbanism—referred to in this paper as

caring architecture—has increased significantly in recent years [

37,

38].

In Spain, reflections on care in architecture remained marginal until the COVID-19 pandemic. In feminist urban planning, the main focus of research has been the spatial division between the public and the private spheres [

39,

40]. Care, in contrast, has been treated as a secondary issue, tied to the domestic sphere [

41,

42] and to urban mobility [

43]. However, COVID-19 represented a turning point. The concepts of

caring architecture and

caring city are beginning to emerge as an independent research field within explorations of gender, domesticity, and urbanity [

23,

44].

However, this development remains marked by a lack of systematization. To date, there is no research that critically delves into the theoretical roots that sustain care architecture, particularly from feminist care ethics, whose contributions are key to understanding care as both a political and ethical practice. Therefore, a systematic analysis of caring architecture is needed to identify and articulate the diverse principles and concepts currently dispersed throughout the literature.

2. Materials and Methods

The aim of this research is to identify references, concepts, and principles in the literature on caring architecture from the perspective of feminist care ethics. Within the umbrella of caring architecture, urban planning (caring city) is also included, since the architecture education system in Spain encompasses both disciplines.

The methodology is structured into four phases: (1) a systematic literature review on caring architecture; (2) a bibliometric analysis of the selected texts; (3) a conceptual analysis of the authors’ theoretical framework; and (4) a thematic analysis of common principles across the selected works.

To carry out the systematic review, a search protocol was developed following PRISMA guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols). PRISMA is a widely recognized analytical methodology for systematic literature reviews in scientific research [

45].

The research was developed following the PCC framework (Population–Concept–Context) [

46], where included population were agents of care—care receivers, caregivers, architects, family members, etc.; the concept was

caring architecture from the perspective of feminist care ethics; and the context was the existing academic literature.

Regarding inclusion criteria, the type of publication was restricted to books, doctoral theses, and scientific articles in English and Spanish. The systematic review was temporally limited to recent texts, preferably those published after the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020). However, the scope was extended to 2018 in order to include literature produced during the fourth wave of feminism, which in Spain is marked between the #MeToo movement in October 2017 and the feminist march of March 8, 2018. Furthermore, only texts that propose a term related to caring architecture or caring city were selected. Consequently, articles outside the fields of architecture and urban planning were excluded, as well as those limited to applying feminist care ethics to case studies.

The publications were hand searched in three international databases (Scopus, Web of Science, and JSTOR) and two Spanish databases (Dialnet and SciELO). Google Scholar was also used to include grey literature (non-academic books, conference papers, etc.), which is highly relevant in the Ibero-American context.

The references identified in the literature search were imported into Zotero, with duplicates removed. The first author was the sole researcher responsible for the first screening process by title and abstract, which consisted of hand excluding documents following three criteria: (1) incorrect publication type—bachelor or master’s theses, book or literature reviews, reports, etc.; (2) discipline other than architecture and urban planning; and (3) practical or methodological approach, without developing a theoretical framework. Subsequently, in the second and final screening process, the eligibility was reviewed by assessing the full text. In this case, the exclusion criteria were twofold: (4) incorrect focus—does not incorporate feminist care ethics; and (5) absence of a developed concept. Both screening processes were supervised and approved by the second author. The risk of bias was not assessed in this research.

The data extraction process was carried out independently by the first author. The selected texts were analyzed using Atlas.ti. The coding and critical analysis of the documents were structured into three perspectives: bibliometric analysis, conceptual analysis, and thematic analysis.

The bibliometric analysis consisted of identifying the references cited in the texts, classifying them by field of knowledge. The aim of this process was to detect the authors or theories that predominantly influence caring architecture. In the case of feminist care ethics, a genealogical review of the conceptual evolution of care was undertaken based on the main voices identified in the bibliometric analysis.

The conceptual analysis involved a critical review of the primary (meanings) and secondary concepts developed in the selected texts. These concepts were grouped into the three dimensions of care identified in the bibliometric analysis: interdependence, eco-dependence, and economics of care.

The thematic analysis consisted of coding a series of pre-selected topics (caring principles), previously elaborated from an initial reading of the chosen texts. These principles were progressively refined and grouped after the in-depth conceptual analysis. They were then synthesized and categorized into three dimensions, interconnecting the three pillars of sustainability with the dimensions of feminist care ethics: sociocultural dimension (interdependence), environmental dimension (eco-dependence), and economic dimension (economics of care).

3. Results

The research findings are structured into four complementary approaches that connect caring architecture with feminist care ethics. First, the systematic literature review provides methodological rigor and strengthens the validity of the corpus. Second, the bibliometric analysis traces the genealogy of care in feminist care ethics, highlighting Joan Tronto and María Puig de la Bellacasa, and organizes its evolution into three dimensions: interdependence, economics of care, and eco-dependence. Third, the conceptual analysis exposes the polysemy of care and categorizes it within these dimensions, preventing generic or depoliticized uses of the term in architecture and urban planning. Finally, the thematic analysis grounds the discussion in disciplinary practice through fifteen care principles linked to sustainability in its sociocultural, environmental, and economic dimensions.

3.1. Systematic Literature Review

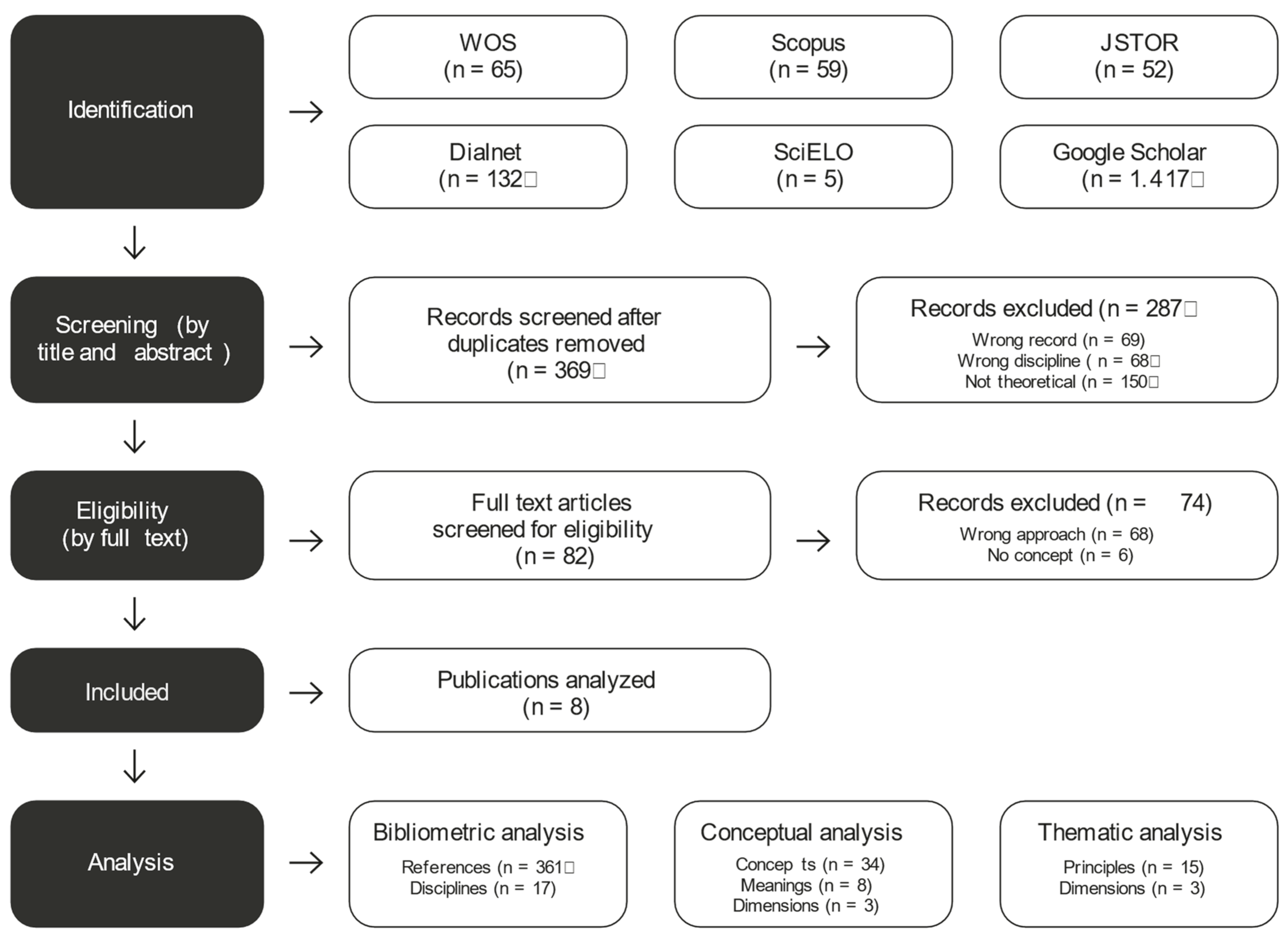

The results of the systematic literature review are summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 1). The literature search identified

n = 369 potentially relevant sources after duplicates were removed. In the first screening phase, publications were filtered by title and abstract, resulting in

n = 287 documents excluded: 24% due to publication type, 23% for belonging to a different discipline, and the remaining 53% for having a practical nature without developing a theoretical framework. In the second full-text screening phase,

n = 74 publications were excluded, 92% for not incorporating the feminist care ethics perspective and 8% for not developing a concept. After the screening process,

n = 8 publications were selected for in-depth analysis. In the texts that include case studies, only the theoretical chapters detailed in

Table 1 were examined.

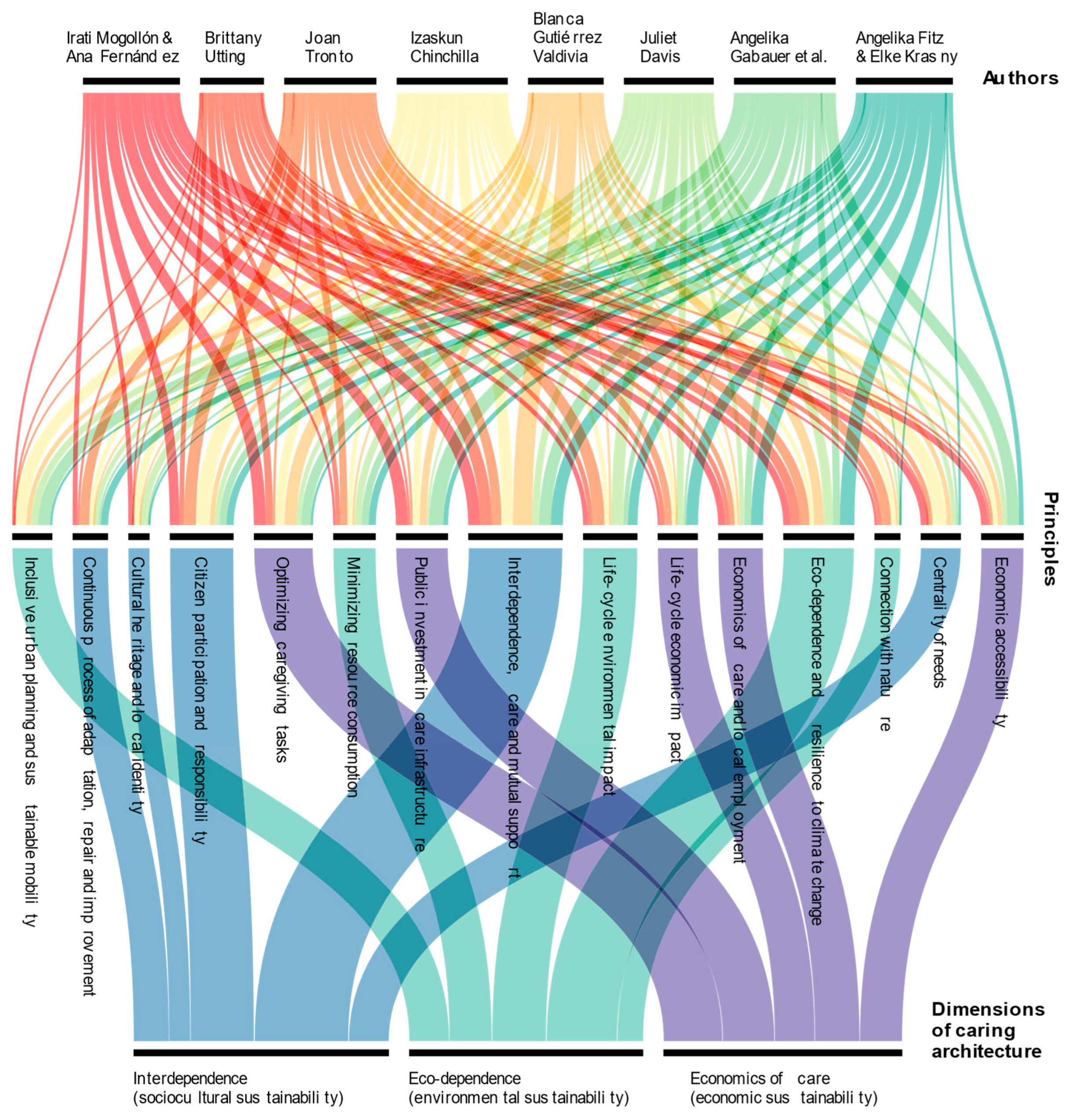

During the analysis stage, n = 361 references were identified across n = 18 disciplines (bibliometric analysis); n = 8 meanings and n = 34 secondary concepts across n = 3 dimensions (conceptual analysis); and n = 15 principles across n = 3 dimensions (thematic analysis).

3.2. Bibliometric Analysis

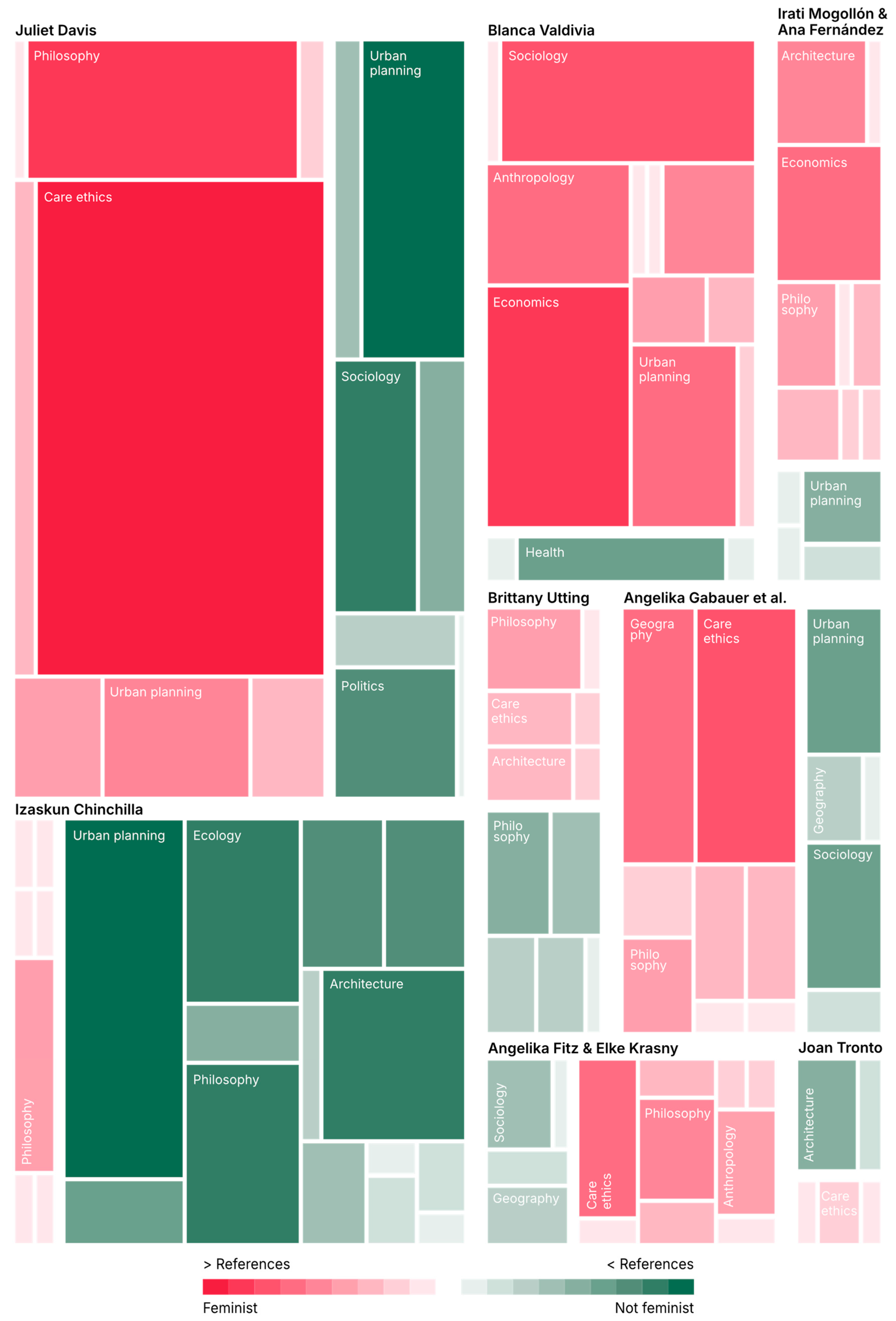

Of the 361 references identified, 52% are framed from a feminist perspective. 52% of the references are authored solely by women, 35% by men, and the remaining 13% correspond to mixed authorships or institutions. Among male authors, the main references include renowned figures in urban planning—Matthew Carmona, Kevin Lynch, and Jan Gehl—and in philosophy—Bruno Latour and Herbert Marcuse. Only 13 of the 128 individual male authors explicitly draw on feminist theory in their work.

By discipline, urban planning (

n = 57) is the field with the highest number of references, followed by philosophy (

n = 55), care ethics (

n = 43), sociology (

n = 42), and architecture (

n = 37). The distribution of references by authorship, discipline, and integration of gender perspective is represented in

Figure 2.

Although philosophy accounts for the highest number of cited references, feminist care ethics constitutes the theoretical backbone. All of the authors studied—with the exception of Izaskun Chinchilla—draw upon the main voices of feminist care ethics: Joan Tronto (n = 31), Virginia Held (n = 20), María Puig de la Bellacasa (n = 17), Selma Sevenhuijsen (n = 8), Carol Gilligan (n = 6), Eva Kittay (n = 6), The Care Collective (n = 5), Nel Noddings (n = 4), and Sara Ruddick (n = 3), among others.

Apart from feminist care ethics, the authors reference other disciplines shaped by a gender perspective. The most significant is feminist philosophy, through key scholars such as Silvia Federici, Nancy Fraser, Donna Haraway, and Hannah Arendt. Architecture and urban planning—with Peggy Deamer and Susan Fainstein—anthropology (Anna Tsing), and geography (Karen Till) have also contributed substantially to the concepts analyzed.

In the case of Spanish authors—Blanca Valdivia, Irati Mogollón, and Ana Fernández, with the exception of Izaskun Chinchilla—their works are supported by leading feminist voices in Spain, including Zaida Muxí and Inés Sánchez de Madariaga (feminist urbanism), Yayo Herrero and Dolors Comas d’Argemir (feminist anthropology), Cristina Carrasco and Amaia Pérez Orozco (feminist economics), and María Ángeles Durán (feminist sociology).

The significant presence of references linked to feminist care ethics highlights the centrality of this perspective in caring architecture. This finding underscores the need to analyze its conceptual roots. Accordingly, this section examines the evolution of care from a genealogical perspective. Understanding this genealogy not only clarifies the philosophical dimension of caring architecture but also reveals how care has been consolidated as a concept that is simultaneously relational (interdependence), political (economics of care), and ecological (eco-dependence), transcending its traditional association with domesticity or welfare.

3.2.1. Relational Care

Care ethics emerged with Carol Gilligan’s

In a Different Voice [

47] as a critique of the androcentric vision that dominated psychology, philosophy, and politics. Against Lawrence Kohlberg’s theory of cognitive development [

48], Gilligan argues that women do not possess a lesser moral capacity [

49] (p. xiv). Contrarily, women often emphasize an ethics of care in their moral decision-making, prioritizing values such as empathy, and affection. Men, by contrast, tend to follow an ethics of justice, based on principles such as impartiality. Gilligan therefore criticizes the universalization of the values associated with the ethics of justice, while the principles of care ethics have been excluded from moral philosophy [

49] (p. xiv).

Along similar lines, Nel Noddings [

50] prioritizes relationships over universal principles. For Noddings, care is a relationship between two agents—the

one-caring and the

cared-for—structured along two dimensions:

caring for and

caring about [

50] (p. 33). Within care dynamics,

caring for refers to the practical dimension of care, involving actions that directly address the needs of the

cared-for. By contrast,

caring about refers to the affective dimension, encompassing feelings, emotional bonds, and the sense of responsibility that motivate a care relationship [

50] (pp. 30–58). Her approach shifts slightly from Gilligan’s identification of a “different voice”. While Noddings also considers care as a natural disposition, her emphasis is on relationship and responsiveness.

Eva Kittay also expands on the relational dimension of care in Love’s Labor [

51]. Kittay argues that dependency is an intrinsic condition of human experience. She reclaims the value of care work that sustains dependent individuals, especially in maternal-filial or intensive care relationships [

51] (pp. 29–48). Her approach frames care as a moral practice that emerges from affective connection and mutual responsibility. In this way, Kittay extends the concept of care beyond the emotional bond, highlighting the ethical obligations generated by caring relationships.

3.2.2. Multidimensional Care

Against the initial essentialist perspectives, widely criticized from the fields of clinical ethics and contemporary feminism [

52], other positions within care ethics argue that care is a

thick ethical concept, both a social practice and a moral value [

53]. As Virginia Held points out in

The Ethics of Care [

16], the juxtaposition of Kantian ethics of justice with care ethics is fundamental to ensuring equity in caring practices [

54]. For Held, care and justice must coexist across both domains: the principles of the ethics of justice must be integrated into the private sphere to achieve fairer care, while the values of care ethics must be incorporated into the public sphere to achieve a caring justice [

16] (p. 43). Held rejects the strict dichotomy posed by Gilligan and Noddings, instead advocating for coexistence and complementarity between both ethical approaches.

Selma Sevenhuijsen represents one of the most influential voices in care ethics. In Citizenship and the Ethics of Care [

55], she proposes a redefinition of citizenship that integrates relationality into the organization of political and legal models. Whereas Held’s work builds from moral philosophy, Sevenhuijsen’s approach employs care as a critical tool for rethinking institutional architecture—laws, public policies, democratic structures—from a feminist, political perspective [

55] (p. 35).

The political vision of care defended by Held and Sevenhuijsen is also reflected in Sara Ruddick’s essay

Care as Labor and Relationship [

18] (p. 5). Ruddick considers (1) care as labor, linked to the feminist struggle to recognize domestic work; (2) care as a relationship between caregivers and care receivers; and (3) care as an ethical practice rooted in moral philosophy, which regards vulnerability and interdependence as essential characteristics [

56]. Ruddick offers an even broader perspective by analyzing care from multiple angles: as labor, as relationship, and as ethical practice. By framing care as historically invisibilized and unpaid labor, Ruddick connects care ethics with feminist theory and economics of care [

26,

27,

57,

58].

3.2.3. Posthumanist Care

Joan Tronto is the key author for understanding the intersection between care ethics and architecture. Joan Tronto and Berenice Fisher’s definition of

care in

Moral Boundaries [

59] is quoted in

Critical Care [

22] (p. 13), in

Caring Architecture [

60] (p. 29), in

Architectures of Care [

20] (p. 3), in

The Caring City [

21] (p. 6), and in

La ciudad cuidadora [

44] (p. 177). It is also indirectly cited in

Care and the City [

56] (p. 10) and in

Arquitecturas del cuidado [

61] (p. 15). The only work not influenced by Tronto’s theory is Izaskun Chinchilla’s

La ciudad de los cuidados [

23].

In contrast with the previously analyzed perspectives—which conceive care either as a dispositional dialogue (Gilligan and Noddings) or as an interrelation grounded in ethical, political, and economic values (Kittay, Held, Sevenhuijsen, and Ruddick)—Tronto and Fisher’s [

59] definition of

care introduces a posthumanistic or ecological variable. Tronto identifies four phases of care:

caring about—recognizing the need for care, setting aside one’s own needs;

caring for—taking responsibility for addressing the identified need;

care-giving—carrying out the act of care, once acknowledged and accepted as one’s responsibility; and

care-receiving—assessing the effectiveness of the care provided, ensuring that the needs of the cared-for have been met [

59] (pp. 105-108). To

care well, she defines four ethical principles linked to these phases:

attentiveness,

responsibility,

competence, and

responsiveness, respectively [

59] (pp. 127-137). In

Caring Democracy [

19], Tronto adds a fifth phase,

caring with, based on

solidarity [

19] (p. 23, 35). For Tronto,

caring with situates care at the center of public policies, dismantling the boundary between public and private spheres, and extending care practices to both institutions and personal relationships [

19] (pp. 169-170).

María Puig de la Bellacasa also stands out as one of the most frequently cited authors, appearing in four of the eight publications analyzed. Like Tronto, Puig de la Bellacasa adopts a posthumanist perspective. Both authors agree on the need to extend care beyond interpersonal relations, stressing the importance of caring for the planet and all forms of life. However, while Tronto focuses on the democratic value of care, Puig de la Bellacasa explores its techno-ecological dimension [

62]. In

Matters of Care [

62], the author radically expands the scope of care beyond human relations, embedding it in the complex web of interdependencies among humans, technologies, and natural environments [

62] (pp. 1-12). Puig de la Bellacasa introduces the term

matters of care [

62] (pp. 52-56) as a critique and complement to Bruno Latour’s concept of

matters of concern [

62] (pp. 31-39) in actor–network theory [

63]. Whereas Latour emphasizes paying attention to things and their networks, she underscores the need to engage with them affectively and ethically. Another key contribution is her conception of care as a

speculative practice [

62] (pp. 57-62) that experiments with alternative forms of relation. Speculation thus becomes a critical tool to question dominant extractivist logics and foster vulnerability [

62] (pp. 20-22).

Drawing on Tronto and Puig de la Bellacasa,

The Care Collective deepens the radical dimension of care from a “feminist, queer, antiracist, and eco-socialist” perspective [

64] (p. 22). Against neoliberal logics of competition and individualism,

The Care Manifesto [

64] calls for reorganizing socioeconomic and ecological relations around interdependence. Their proposal includes building

caring communities of mutual support, developing

caring states that guarantee public care services, and fostering

caring economies [

64]. The Care Collective also introduces the term

promiscuous care, understood as a caring practice not limited to affective ties but extended to strangers, non-human beings, and the natural environment [

64] (pp. 40-44). In this way, the collective broadens the scope of care, integrating expansive forms of relation with people and territories.

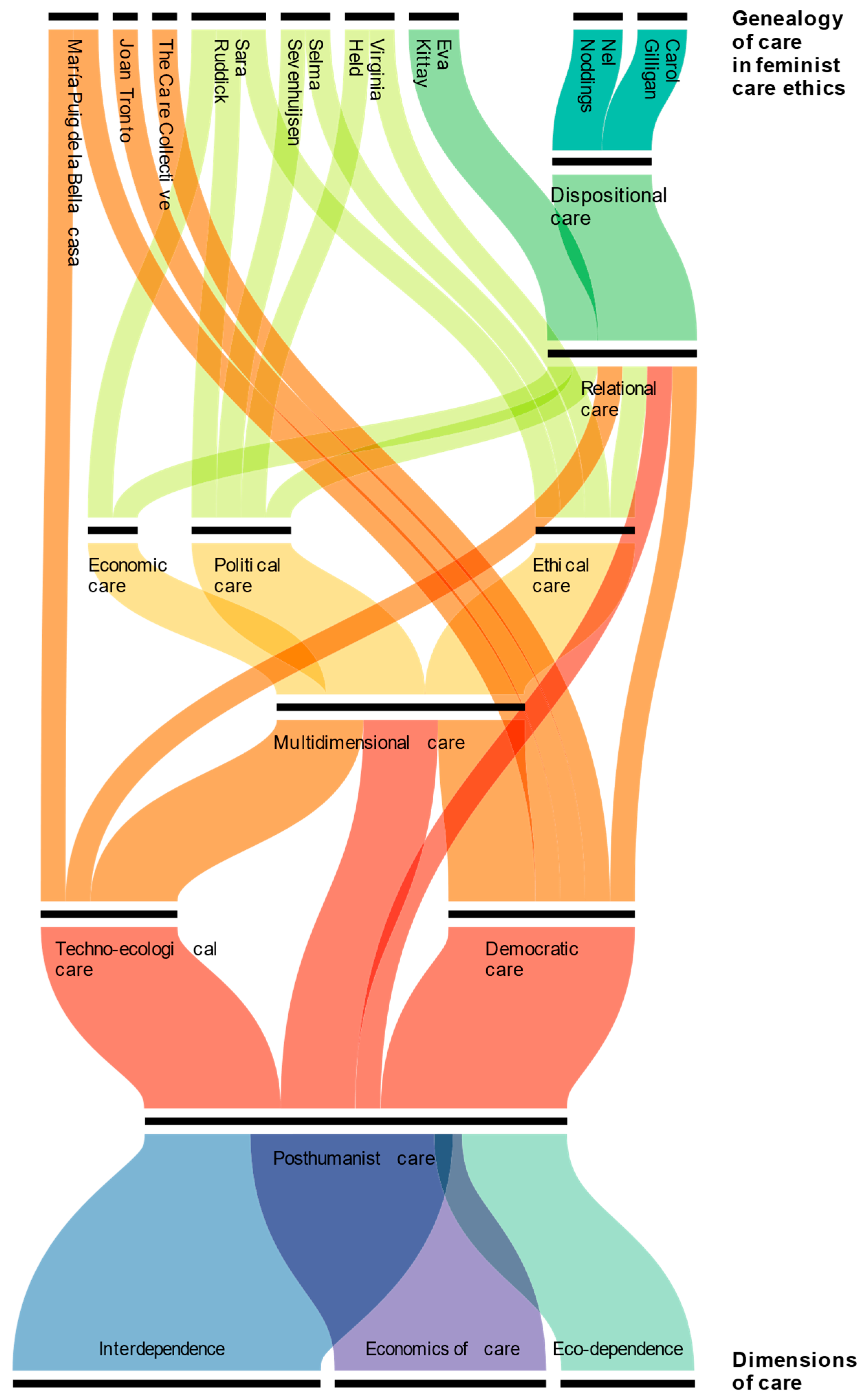

The genealogical evolution of

care is summarized in

Figure 3. Overall, the development of feminist care ethics across the authors analyzed shows a progression from recognizing a valuable moral perspective (Gilligan), to exploring the relational dynamics of care (Noddings), its integration with the ethics of justice and recognition as a multidimensional concept with moral (Held), political (Sevenhuijsen), and economic (Ruddick) values, and finally to its posthumanist expansion as a democratic ideal (Tronto), capable of transforming the established order (The Care Collective) and transcending into the techno-ecological sphere (Puig de la Bellacasa).

Along this path, three central dimensions of care emerge: interdependence, which acknowledges vulnerability and mutual dependence as universal conditions of human experience, placing care at the center of socio-economic, political, and techno-ecological relationships; economics of care, which makes visible and claims the value of reproductive and domestic labor, historically rendered invisible as a ‘women’s issue’, advocating its recognition within economic and democratic structures; and eco-dependence, which extends care beyond human ties, integrating the sustainability of the natural environment, technology, and other forms of life as an essential part of the worlds we inhabit. These three dimensions are not isolated compartments, but complementary perspectives that allow care to be understood as a relational, multidimensional, and posthumanist practice.

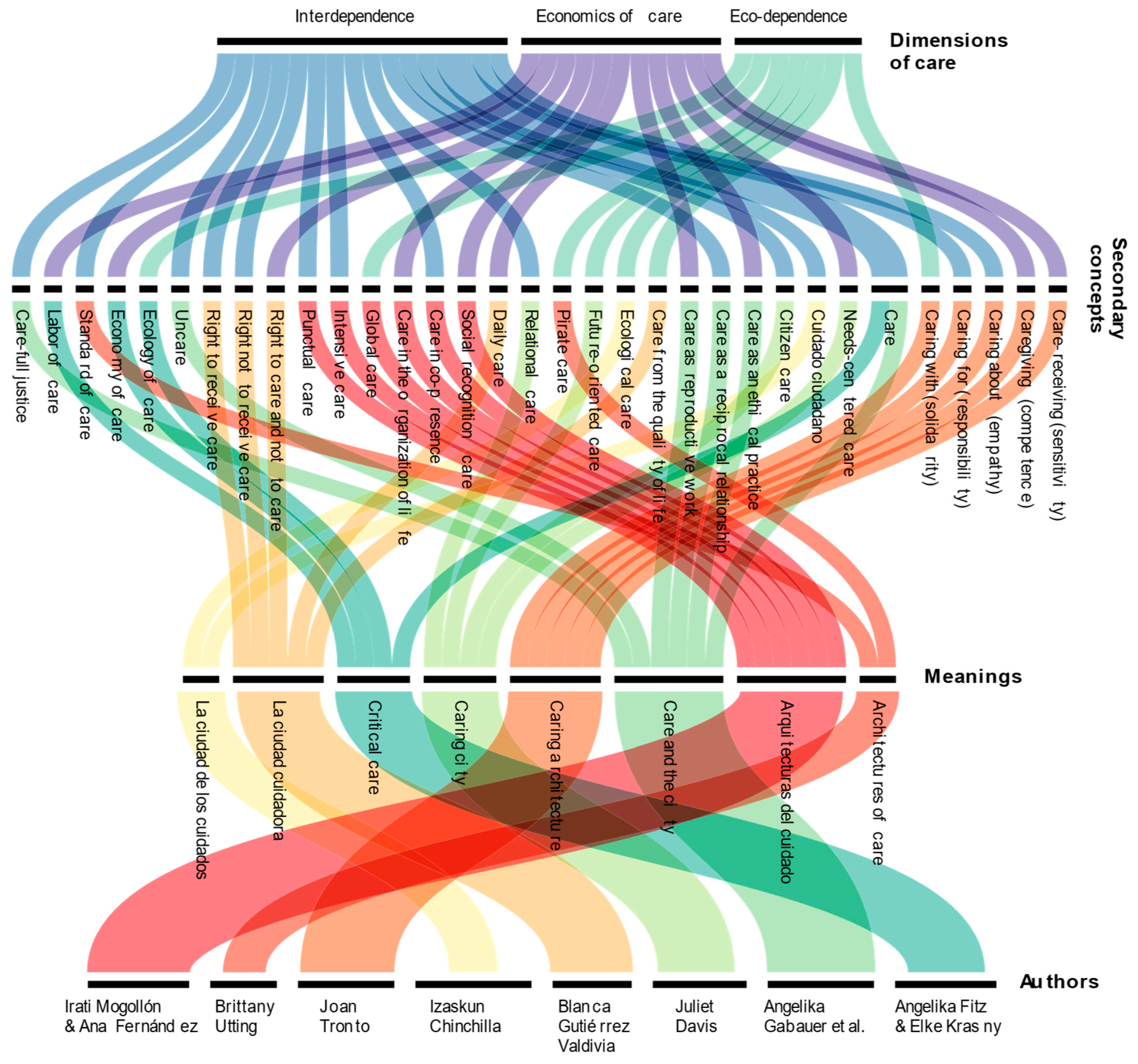

3.3. Conceptual Analysis

The conceptual analysis identified

n = 8 meanings and

n = 34 secondary concepts. The secondary concepts were organized within the three care dimensions (

Figure 4)—interdependence, economics of care, and eco-dependence—detected in the bibliometric analysis. The analysis highlights the polyhedral nature of

care in contemporary architecture and urban planning. Far from being a univocal idea, the concept of

care unfolds across multiple dimensions that, although sharing a common root based on interdependence, economics of care, and eco-dependence, acquire different nuances depending on the disciplinary approach, each author’s trajectory and context. This diversity of interpretations can be organized into two main categories:

Anglo-American and Central European authors—Angelika Fitz, Elke Krasny, Joan Tronto, Brittany Utting, Juliet Davis, and Angelika Gabauer et al.—approach care from a theoretical perspective that is critical of neoliberal capitalism and the climate crisis. Care is therefore understood as a structural, political, and macro-scale concept that can transform power relations and planetary sustainability.

On the other hand, Spanish-speaking authors—Blanca Gutiérrez Valdivia, Izaskun Chinchilla, Irati Mogollón García, and Ana Fernández Cubero—understand care from a situated perspective, anchored in everyday experiences and feminist knowledge contextualized in Southern Europe and Latin America. Their approach integrates theory and practice through community participation and self-management.

3.3.1. Global Perspectives

Angelika Fitz and Elke Krasny [

22] introduce the concept

critical care to refer to “our planet’s life-threatening condition” [

22] (p. 10). In the face of an extractive economic system “at war with many forms of life on earth, including human life” [

22] (p. 11), the authors propose rethinking the future as a time for planetary recovery and repair. For Fitz and Krasny, care ethics is the necessary perspective to move from a capital-centered architecture to a discipline grounded in human and non-human care [

22] (p. 12). While

Critical Care does not deny the close relationship between architecture, production, and resource consumption, the authors advocate for a model that interconnects care, economy, ecology, and labor—seeking both socio-economic and environmental sustainability [

22] (p. 14).

In Fitz and Krasny’s

Critical Care, Joan Tronto writes the opening essay, titled

Caring Architecture [

60]. For Tronto, architecture prioritizes power and capital, when it should be concerned with more relevant aspects such as “what happens within the buildings, how the building fits within its location and context, how it was built, who it will house or displace” [

60] (p. 27). Tronto stresses that the concept of

caring architecture entails a shift in perspective toward a feminist, relational, and care-based approach, one that allows “thinking of [buildings] in relationships—with ongoing environments, people, flora, and fauna” [

60] (p. 28), rather than as aesthetic objects.

Tronto applies her theory of the five phases of care [

19,

59] to architecture and urban planning.

Caring about requires

attentiveness to detect the inequalities present in the built environment, such as gentrification, real estate speculation, rural depopulation, and energy poverty.

Caring for consists of taking

responsibility of the impact that design decisions will have on living beings and the environment.

Care giving requires

competence to implement methodologies that ensure the integral well-being of all agents involved.

Care receiving centers on

responsiveness to continuously assess and monitor the completed building.

Caring with accounts for values such as

solidarity,

plurality, and

communication to place care for people and the planet at the heart of architectural practice.

The book

Care and the City:, edited by Angelika Gabauer et al. [

56], explores the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on urban space. The authors employ the terms

care and

uncare to describe two opposing dimensions that emerged during the pandemic.

Uncaring practices are those characterized by national “one-size-fits-all” policies that fail to account for spatial inequality [

56] (p. 3). During the pandemic, such neoliberal

uncaring policies were visibly manifested in the exploitation of care professions and the lack of public infrastructure in residential areas. However, the COVID-19 crisis also fostered

caring practices of neighborhood solidarity and mutual support within urban space [

56] (p. 3).

Moreover, Angelika Gabauer et al. draw on Sara Ruddick’s theory to define care as labor, relationship, and ethical practice. In their words, “care encapsulates what people

do (spatial praxis) when they care, how they mutually

interact (social relations) when caring, and how and why they tend to

reflect on these doings and interactions in a morally informed way (care ethics)” [

56] (p. 5). Against the critique of the modern city grounded in Henri Lefebvre’s

right to the city [

65], the editors propose a new theoretical framework that “brings together feminist ethics of care approaches with predominant discourses on rights and justice in cities” [

56] (p. 7), following Miriam J. Williams’s [

66] idea of

care-full justice.

The publication

The Caring City by Juliet Davis [

21] focuses on the capacity of urban design to enhance caring practices. The author structures care around four essential characteristics: (1) care is focused on needs; (2) care is relational, (3) care is a process, and (4) care is future-oriented [

21] (pp. 11-21). Contextualized within urban design, care must not only guarantee the needs of users, but also anticipate future environmental challenges [

21] (p. 14). Secondly, understanding care as relational entails recognizing how design decisions shape caring relationships. This also means considering the interdependencies of cities on the territories that supply resources or manage waste [

21] (p. 16). Thirdly, defining care as a process relates to applying Joan Tronto’s five phases of care [

21] (pp. 17-19). Finally, Davis argues that urban design is an intrinsically future-oriented discipline. A

caring urban planning preserve planetary resources for future generations [

21] (p. 21).

For Juliet Davis, the

caring city must foster interdependencies between people and environments, while also acknowledging the historical inequalities that have stigmatized dependency and vulnerability [

21] (p. 192). Urban design must “develop alternative models of development” [

21] (p. 196), such as social housing, self-build strategies, non-profit projects, and public facilities. Finally, the

caring city must meet the needs of both “present lives” and “planetary futures” [

21] (p. 197).

Lastly, Brittany Utting’s Architecture of Care [

20] develops the concepts of

standard of care and

pirate care. In Anglo-American architectural practice, the

standard of care refers to the benchmark that determines whether architects have fulfilled their professional obligations. For the author, this standard circumscribes “the built environment as separate from rather than entangled with larger planetary processes, systems, and reciprocities” [

20] (p. 3). In contrast, Utting proposes reimagining architectural conventions to foster a more radical, political practice. To reinvent the

standard of care in architecture, the author is influenced by the platform

Pirate Care [

67]. This collective defends the development of a

pirate practice—that is, engaging in acts of political activism [

68] (p. 65). Utting establishes the concept of a

pirate architecture of care as a form of disobedience to the canonical practice of architecture.

3.3.2. Spanish Perspectives

Blanca Valdivia’s

La ciudad cuidadora (

The Caring City) is one of the first publications in Spain to explore the intersection between care and the city [

44]. Valdivia emphasizes that care practices have historically been assigned to women due to gender stereotypes and the sexual division of labor within the patriarchal system. Drawing on feminist urban planning, Valdivia argues that both the public–private split of the city and gender inequalities in the allocation of care responsibilities pose challenges for women’s quality of life [

44] (pp. 177-194). The most innovative contribution of Valdivia’s thesis is the introduction of the

right to care [

44] (p. 181), a concept originally explored by Amaia Pérez Orozco [

57]. These notion connect the values of care ethics—vulnerability and interdependence—with Marxist philosophy—socialization of power structures—and Henry Lefebvre’s

right to the city [

65].

La ciudad de los cuidados (

The City of Care) by Izaskun Chinchilla [

23] constitutes another pioneering contribution. While Valdivia approaches the

caring city from the perspective of feminist urban planning, Chinchilla’s positioning on the

city of care emerges from Herbert Marcuse’s critical theory, ecology, and architectural practice. Most of the references in

La ciudad de los cuidados correspond to predominantly male and established figures in philosophy, politics, and sociology, such as Bruno Latour [

69], Jan Gehl [

70], and Kevin Lynch [

71]. However, this theoretical references do not occupy a central place in her vision of care. Chinchilla arrives at the concept of the

city of care through empirical observation in participatory architecture workshops with children [

23] (pp. 14-30). Her definition does not stem from care ethics but rather from a subjective perception, rooted in her experiences as an architect leading her own practice, as a mother struggling with work–life balance, and as a citizen confronting the challenges of climate change.

Finally, the book

Arquitecturas del cuidado (

Architectures of Care) by Irati Mogollón and Ana Fernández [

61] explores the relationship between architecture, feminist care ethics, and ageing. The authors argue that ageing is gendered: women are both the main providers and receivers of care [

61] (pp. 12-13). The apparent autonomy of the economic system is sustained by a “subsystem of care practices, markets, and submerged, informal economies and services that make it possible to meet the whole range of social needs” [

61] (p. 15). From the study of case studies of cohousing in Europe emerges the term

architectures of care [

61] (pp. 180-184), whose defining features include: (1) needs as the starting point; (2) the externalization of the domestic sphere; (3) caring spaces; (4) universality and particularity; and (5) evolutionary and scalable.

Architectures of care calls for design approaches that respond to the desires, resources, and dependencies. Moreover, care must also occupy public spaces to be recognized as a shared responsibility. Furthermore,

architectures of care must integrate universal elements—ecological impact, intimacy, empowerment—with the contextual factors, adapting to different life cycles and developing intermediate spaces for the community.

3.4. Thematic Analysis

Following the conceptual analysis, we propose a theoretical corpus for

caring architecture. This framework is articulated around 15 caring principles (

Figure 5), which are grouped into the three key concepts of feminist care ethics: interdependence, economics of care, and eco-dependence. Each of these perspectives is also linked to a dimension of sustainability: sociocultural dimension (interdependence), economic dimension (economics of care), and environmental dimension (eco-dependence).

The dimensions of sustainability [

72] intertwine with the idea of

sustainability of life, as defended by gender studies [

25,

32] and feminist care ethics [

19,

62,

64]. Interdependence, which acknowledges that all individuals are vulnerable and dependent on others, has been associated with the sociocultural dimension of sustainability, as it emphasizes the importance of environments that foster mutual support, and social inclusion, particularly in contexts of vulnerability such as old age. Economics of care, which advocates for a fair redistribution of care responsibilities, has been linked to the economic dimension of sustainability, as it requires rethinking architecture in terms of sustaining life rather than maximizing economic profit. Finally, eco-dependence, which highlights the structural dependence of human beings on ecosystems and natural resources, has been connected to the environmental dimension, as it demands architectural practices that respect the ecological limits of the planet.

Among the 15 caring principles (

Figure 5), the most frequently recurring are interdependence (

n = 40), eco-dependence (

n = 30), citizen participation (

n = 27), optimization of care tasks (

n = 25), and public investment in care infrastructures (

n = 22). Conversely, the principles with the lowest recurrence are culture and local identity (

n = 9), connection with nature (

n = 11), and processes of adaptation and repair (

n = 15). This distribution reflects the authors’ emphasis on the sociocultural dimension, with

n = 95 recurrences. The economic (

n = 78) and the environmental (

n = 66) dimensions rank second and third, respectively.

3.4.1. Interdependence and the Sociocultural Dimension

Theoretical approaches to

caring architecture begin from the particular,

placing needs at the center [

19,

44] and acknowledging diversity. The aim is to design accessible spaces for all agents involved, while addressing the specific needs of each group to avoid homogeneous, standardized models. Architectural design must adapt to the evolving needs across the life course [

61] (pp. 180-184).

At the same time, this design approach recognizes that people are not isolated beings but relational [

56] (p. 5). This entails designing

spaces of interdependence, care, and mutual support that facilitate work–life balance, shared responsibility, and family support [

60] (p. 28), while also reducing the burden on caregivers and the isolation of those in need of care [

56] (p. 3). Architecture should promote environments that encourage social interaction and caring communities [

21,

60] (pp. 11-12, p. 28). This may include designing shared spaces—gardens, squares, meeting rooms—that enable intergenerational encounters, creating spaces for children, older people, and other vulnerable groups [

21] (p. 192), and integrating healthcare services [

61] (pp. 180-184).

Furthermore, architecture must be sensitive to the context, respecting

cultural heritage and local identity. The integration of traditional elements and techniques into design, using local materials, or adapting to social practices [

61] (pp. 180-184) are strategies that can strengthen the sense of belonging among community members [

23,

44].

Caring architecture also empowers people by fostering spatial appropriation [

44] (pp. 300-302). This involves creating spaces that encourage

citizen participation and shared responsibility among users [

60] (p. 28) through participatory practices such as workshops, public consultations, and other mechanisms of collaboration between architects, urban planners, technicians, policymakers, and the community [

22,

23]. In doing so, spaces become sites of encounter and care that redistribute power dynamics [

20,

60] (p. 27, p. 2).

Finally, this design approach does not consist of delivering a finished product, but rather unfolds as a

continuous process of adaptation, repair, and improvement. Architecture must constantly adapt to and learn from its users [

61] (pp. 180-184). To this end, it is essential to periodically evaluate the impact of architectural interventions, making adjustments and repairs to ensure that the needs of occupants, the community, and the environment are being met over time [

21] (p. 197).

3.4.2. Economics of Care and Economic Dimension

Caring architecture advocates for feminist economics of care by

optimizing caregiving tasks through solutions that facilitate access, mobility, safety, and communication. Flexible and adaptable spaces can decrease the need for care, an unpaid burden that has traditionally fallen on women [

56,

61] (p. 4, pp. 12-13). Additional measures, such as assistive technologies, removing architectural barriers, and creating safe and stimulating environments, can also facilitate caregiving practices [

44] (pp. 177-194).

Caring architecture must ensure

economic accessibility for all. Against real estate speculation, promoting social housing, cohousing models [

20,

61], and self-construction strategies can guarantee the right to adequate housing and to basic resources such as water, energy, and public transportation [

21] (p. 196).

At the urban level, the

caring city requires

public investment in care facilities and infrastructure that support daily life [

44] (pp. 300-302). This includes promoting public hospitals, schools, daycare centers, care facilities, assisted living, cultural and meeting spaces, sports infrastructures, and accessible public transportation [

21] (p. 196). Investment in these care infrastructures generates social and economic returns, as it improves quality of life, promotes health, and frees time for community participation [

56] (p. 3).

Moreover, the economic responsibility of architecture encompasses the building’s entire life cycle, from raw material extraction to demolition and waste management. To reduce

life-cycle economic impact and lower operational and long-term costs [

21] (p. 196), priority should be given to sustainable and durable materials, efficient construction processes, and strategies for reuse, recycling, and disassembly [

21] (p. 197).

Caring architecture also aims to promote

economics of care and local employment by using local materials and labor, while fostering cooperative management systems, volunteerism, and education [

22] (p. 14). Furthermore, architecture must ensure the safety and well-being of all workers and agents involved in the construction process [

60] (p. 31).

3.4.3. Eco-Dependence and Environmental Dimension

Caring architecture also recognizes the interdependence between people and the environment (

eco-dependence). Design must start from the understanding that human well-being depends on healthy ecosystems [

22] (p. 12). Architecture should be

resilient to climate change, considering both the risks and opportunities this phenomenon presents. Building design must adapt to changing climatic conditions, such as rising temperatures, droughts, and floods [

22] (pp. 10-11).

The climate crisis demands

minimizing the consumption of planetary resources. Materials extraction and production, and the energy consumption of buildings have a significant environmental impact [

22] (p. 14). Consequently, priority should be given to bioclimatic and sustainable design strategies, including the use of renewable and recyclable materials, reducing water consumption, and optimizing energy efficiency [

21] (pp. 14, 16-17).

In this regard,

caring architecture must consider the

life-cycle environmental impact of buildings, including material manufacturing and transport, construction, building operation, demolition, and the potential reuse and recycling of materials at the end-of-life phase [

21,

60] (p. 17, p. 31). This entails the use of sustainable construction systems and circular materials, reducing CO₂ emissions [

22] (p. 14), responsibly managing waste, and promoting strategies for disassembly [

21] (p. 197).

Another key principle is

connection with nature. Integrating natural elements into spatial design benefits both physical and mental health. This may include the incorporation of vegetation, the creation of courtyards and gardens, the use of natural light and cross ventilation, and the promotion of spaces with exterior views [

23]. Additionally, architecture should integrate respectfully into the natural environment to conserve biodiversity and protect ecosystems, taking into account factors such as topography, solar orientation, and local microclimate [

60] (p. 28).

At the urban scale, the

caring city must promote

inclusive urban planning that ensures safety and universal accessibility in public spaces, with particular attention to the most vulnerable individuals [

21,

44,

56]. Likewise, a

caring city should integrate

sustainable mobility solutions to reduce car dependence, promoting public transport, cycling, and walking. Measures can include placing bus stops and bicycle parking near buildings, creating bike lanes and safe pedestrian areas, and implementing shared mobility strategies [

21,

23,

44,

56].

4. Discussion

Although the authors employ different terms—such as

caring architecture,

architectures of care,

caring city, and

city of care—they all converge on the same idea: architecture and urban planning must assume an active role in creating a more just, sustainable society that prioritizes the well-being of people, communities, and the built and natural environment. Understanding the building as an element interwoven within a network—interdependent and eco-dependent on the social, natural, and built environments in which it is embedded—stems from a feminist perspective that Joan Tronto highlights [

60] (p. 28). Just as gender studies conceptualize care practices through circles [

31,

32],

caring architecture can likewise be understood as a set of interconnected circles.

These circles of care (

Figure 6) can be organized from an

architectural perspective—structured across scales that integrate the natural and built environment—from a

sustainability perspective—divided into socio-cultural (interdependence), environmental (eco-dependence), and economic dimensions (economics of care)—and from a

democratic perspective, encompassing all agents engaged in care practices—including the government, environment, industry, academia, and society.

We thus refer to a form of caring architecture that is necessarily democratic and sustainable—what this paper terms caring, democratic, and sustainable architecture. Moreover, this research focuses specifically on older people as one of the main collectives or agents receiving care. These three defining features of caring architecture—democratic, sustainable, and oriented towards older adults—are developed in the following discussion section.

4.1. Sustainable Caring Architecture

The framework of

caring, democratic, and sustainable architecture, present across all the authors analyzed, is closely linked to the perspective of holistic sustainability. Caring architecture is inherently sustainable, as both perspectives seek to ensure just and livable conditions in the present and future—for people, for other species, and for the planet.

Caring architecture focuses on the sustainability of life [

25,

32,

59], transcending a functional understanding of architectural design and moving toward an ethical, political, and ecological approach.

A

sustainable caring architecture acknowledges eco-dependence among people and the natural environment. Following the concept of the three dimensions of sustainability [

72], architecture must assume responsibility for the social, environmental, and economic impacts that design has on users’ well-being. Some studies [

73,

74] include culture as a fourth pillar of holistic sustainability, either as an independent component or as a dimension that integrates the social and cultural.

The three pillars of sustainability are reflected in current public policies. In Spain, Law 9/2022 on the Quality of Architecture (

Ley de Calidad de la Arquitectura) recognizes architecture as a public service for collective well-being. This instrument promotes an integrated approach linking environmental sustainability, social inclusion, and balanced economic development. At the same time, the

sustainable caring architecture approach aligns with European and national objectives of climate neutrality and decarbonization of the building stock, such as those set out in the EU’s EPBD and in Spain’s recent ARCE 2050 Project: Zero-Emission Architecture (

Arquitectura Cero Emisiones).

Sustainable caring architecture responds to these goals not only by integrating energy efficiency, circular materials, and renewable energy, but also by assessing life-cycle environmental and economic impacts [

21,

22,

60] (pp. 17, 197, p. 14, p. 31). In this sense, care is translated into a conscious, responsible, and committed architectural practice toward the planet.

4.2. Democratic Caring Architecture

Caring architecture is a democratic perspective that promotes the redistribution of power and collective responsibility in design. In contrast to the hierarchical conception of canonical architecture [

12],

caring architecture claims that architectural design must begin from diversity rather than imposing a universal model [

61] (pp. 180-184).

By acknowledging shared vulnerability and the need for care,

democratic caring architecture calls for an equitable redistribution of responsibilities, which implies that all people, not only experts or authorities, should participate in decisions affecting their ways of life [

20,

23,

60]. Consequently, care is elevated from a domestic practice to a democratic political concept [

19]. Aligned with Joan Tronto’s [

19]

caring with phase,

democratic caring architecture fosters policies of care in which architectural and urban design become part of a shared responsibility. To this end,

democratic caring architecture emphasizes participatory processes [

44] (pp. 300-302), establishing horizontal dialogues where care agents—users, architects, caregivers, policymakers, and the community—engage as equals [

22] (pp. 14, 16).

In the field of social innovation, the quintuple helix model [

75,

76] resonates deeply with

democratic caring architecture, as it advances a systemic transformation grounded in collaboration and life-centered sustainability.

Caring architecture explicitly recognizes all quintuple helix stakeholders as care agents. Not only the government decides but also civil society, which contributes situated and affective knowledge; the environment, considered as an actor rather than a resource to be exploited; academia, as generators of critical and scientific knowledge; and industry, which must assume co-responsibility in creating healthy and inclusive environments. Both approaches foster a co-created architecture, where the power is shared among all collectives involved.

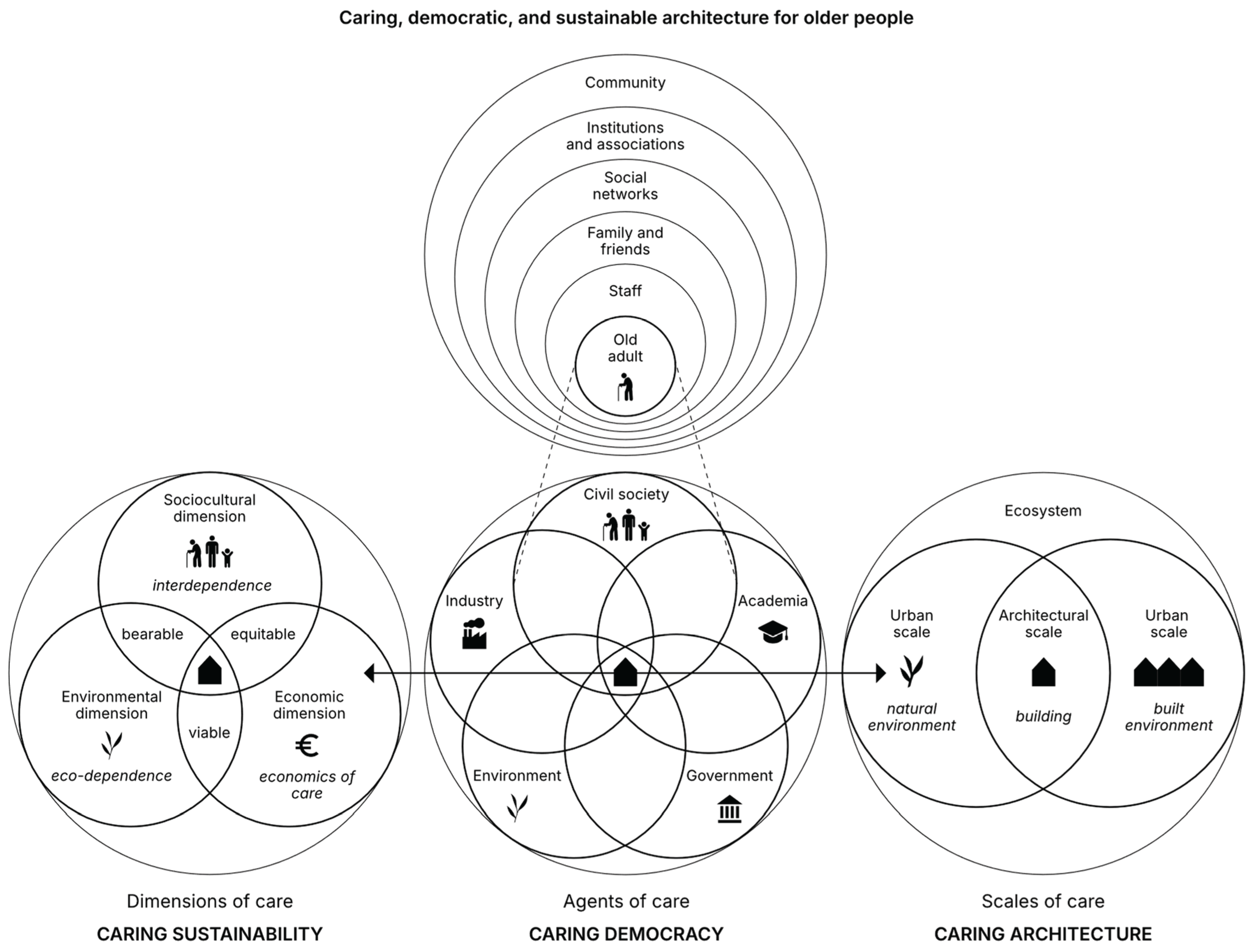

4.3. For Older People

Within the scope of this research, focused on the transformation of the institutional architecture of care facilities for older adults and the implementation of person-centered and community-based residential typologies, it is possible to establish a close relationship between the PCC model and the values advocated by caring, democratic and sustainable architecture.

Both approaches share the goal of improving well-being and quality of life. Just as the PCC model emphasizes tailoring care to the individual needs and preferences of residents [

77],

caring, democratic and sustainable architecture for older people addresses the architectural spaces in which these care practices take place. Thus, the older person is placed at the center of the scales of care, as the main care receiver (

Figure 7).

At the same time, centering care on older people does not exclude the participation of other actors involved. As illustrated in

Figure 7, addressing the needs and aspirations of older adults living in care facilities involves and affects caregivers—both directly (staff, relatives, and social networks) and at a broader sociopolitical level (institutions, associations, and the wider community). Likewise, the actions of other care agents—academia, government, the environment, and industry—also have a direct impact on the quality of life of older people. The principles of

caring, democratic and sustainable architecture, articulated in the thematic analysis, can therefore be applied to care facilities for older adults.

Regarding the sociocultural dimension, the principle of centrality of needs translates into personalized design that considers not only the individual needs of residents, but also their physical, cognitive, and social capacities. Spaces must also be flexible—adapted to the changing needs and abilities of users as they age—and diverse—allowing residents to choose where and how to spend their time. The principle of spaces of interdependence, care, and mutual support entails the design of welcoming, homelike common areas that foster social interaction. In addition, incorporating the principle of cultural heritage and local identity can help strengthen the sense of belonging of older adults. With regard to citizen participation, empowering residents by involving them in decision-making processes (organizing activities, personalizing spaces) is crucial to ensuring that they feel heard and valued, which positively impacts their emotional well-being. Finally, the principle of adaptation and continuous improvement can be implemented through periodic evaluations, making adjustments to care practices and architectural design as needed.

Concerning the economic dimension, the principle of optimization of care tasks involves designing spaces that enable more efficient and personalized care. The use of assistive technologies can help improve users’ autonomy and reduce staff workload. The principles of economic accessibility and public investment in care infrastructure and equipment align with the promotion of public, community-based models, such as senior and intergenerational cohousing, assisted living, living units, and daycare centers. At the same time, the principle of life-cycle economic impact requires consideration of the long-term costs of construction, operation, and maintenance of care facilities. Furthermore, the principle of economics of care and local employment prioritizes the involvement of local businesses in the supply chain and the collaboration with the community. Ultimately, the goal is for the care facility to become a community hub, hosting events and activities open to the wider public.

With respect to the environmental dimension, the principle of eco-dependence and climate resilience requires consideration of the effects of climate change on older adults (particularly heatwaves), ensuring their comfort and safety. In line with the principles of reducing life-cycle environmental impact and resource consumption, buildings must improve energy efficiency and minimize CO₂ emissions. Circular, durable, and low-impact construction materials can be employed, alongside efficient management of water, energy, and waste. Moreover, connection with nature is key to enhancing the overall well-being of older adults. This can be achieved by incorporating natural elements into gardens, courtyards, and terraces. Lastly, it is essential to ensure access to inclusive urban environments and sustainable mobility, including proximity to public transport stops and the design of safe, comfortable pedestrian areas that enable older people to remain active and connected to the community.

5. Conclusions

This paper underscores the urgent need to rethink the role of architecture and urban planning in shaping caring spaces, asserting their responsibility in contributing to the construction of a caring, sustainable, and democratic society. Drawing on a systematic literature review and analysis of theoretical approaches to caring architecture, the research advances the framework of caring, democratic, and sustainable architecture as an integrative paradigm that brings together the principles of feminist care ethics, holistic sustainability, and participatory democracy within architecture and urban design—particularly in the domain of care facilities for older adults.

The proposed framework is articulated through three interrelated dimensions. First, sustainable caring architecture, which recognizes both human interdependence and eco-dependence on the natural environment, while accounting for the sociocultural, environmental, and economic impacts of the built environment across its life cycle. Second, democratic caring architecture, which repositions architecture as a political practice that must redistribute power, foster the active engagement of care agents, and ensure co-responsibility in the design of inclusive spaces. Finally, the research proposes caring, democratic, and sustainable architecture as a particularly pertinent approach for transforming the architecture of care homes for older people. This perspective provides a pathway for operationalizing the principles of the PCC model by advancing personalized, inclusive, and longevity-oriented built environments that promote interdependence, holistic well-being, and community connectedness.

In the face of intersecting crises of care, climate change, and demographic aging, this paper calls for architecture to assume an active role in shaping more equitable and sustainable futures. Caring, democratic, and sustainable architecture is not merely a theoretical construct, but an invitation to reconsider how we design and inhabit spaces—grounded in community listening, shared responsibility, and a commitment to quality of life. In contrast to dehumanizing institutional models, this framework offers a roadmap for reimagining care facilities for older adults as living spaces, deeply embedded in and sustained by bodies, territories, and communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.G.F. and L.C.P.M.; methodology, I.G.F. and L.C.P.M.; formal analysis, I.G.F.; investigation, I.G.F.; data curation, I.G.F.; writing—original draft preparation, I.G.F.; writing—review and editing, I.G.F. and L.C.P.M.; visualization, I.G.F.; supervision, L.C.P.M.; project administration, L.C.P.M.; funding acquisition, I.G.F. and L.C.P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by GOBIERNO DE ARAGÓN, grant T37_23R: Built4Life Lab and GOBIERNO DE ARAGÓN, grant DGA Fellowship 2021-2025. The APC was funded by UNIVERSIDAD DE ZARAGOZA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used ChatGPT and Grammarly to translate the original draft. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. We would like to thank Professor Lien de Proost for teaching the course Ethics of Care at KU Leuven, where we explored feminist care ethics authors and developed the foundations of this research paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| PCC |

Person-centered care |

| PRISMA |

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols |

| PCC |

Population–Concept–Context |

| EPBD |

Energy Performance of Buildings Directive |

References

- Barbosa, M.M.; Dias, I.; Nwaru, B.I.; Paúl, C.; Yanguas, J.; Afonso, R.M. Person-Centered Care for Older Adults at Nursing Homes in the Iberian Peninsula: A Systematic Review. RASP 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMSERSO Actualización No 101. Enfermedad Por Coronavirus (COVID-19) En Centros Residenciales; 2023.

- González-Fernández, I.; Pérez-Moreno, L.C. Environmental, Socio-Cultural, and Economic Sustainability in Care Facilities: Evaluating the Impact of Person-Centered Building Renovation in Aragon, Spain. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 2025, 112, 107822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crews, D.E. Aging, Frailty, and Design of Built Environments. J Physiol Anthropol 2022, 41, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoof, J.; Schellen, L.; Soebarto, V.; Wong, J.K.W.; Kazak, J.K. Ten Questions Concerning Thermal Comfort and Ageing. Building and Environment 2017, 120, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, T.; Martínez-Loredo, V.; Cuesta, M.; Muñiz, J. Assessment of Person-Centered Care in Gerontology Services: A New Tool for Healthcare Professionals. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology 2020, 20, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojano i Luque, X.; Serra Marsal, E.; Soler Cors, O.; Salvà Casanovas, A. Impacto en residencias de la atención centrada en las personas (ACP) sobre la calidad de vida, el bienestar y la capacidad de salir adelante. Estudio transversal. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología 2021, 56, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torío López, S.; Viñuela Hernández, P.; García-Pérez, O. Experiences of Active Aging. Senior Cohousing: Autonomy and Participation. RIFIE 2018, 47, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxezarreta, A.; Cano, G.; Merino, S. Las Cooperativas de Viviendas de Cesión de Uso: Experiencias Emergentes En España. Ciriec-España. [CrossRef]

- Delcampo Carda, A. La Arquitectura Residencial Para Personas Mayores y Los Espacios Cromáticos Para El Bienestar, Universitat Politècnica de València: Valencia (Spain), 2020.

- Rodríguez Rodríguez, P. Las Residencias Que Queremos. Cuidados y Vida Con Sentido; Los Libros de la Catarata: España, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Heynen, H.; Pérez-Moreno, L. Narrating Women Architects’ Histories. Paradigms, Dilemmas, and Challenges. arq.urb 2022, 110–122. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Moreno, L.C. Prácticas Feministas En La Arquitectura Española Reciente. Igualitarismos y Diferencia Sexual. Arte, individuo y sociedad (Internet) 2021, 33, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P. Situating Universal Design Architecture: Designing with Whom? Disability and Rehabilitation 2014, 36, 1369–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklova, K. Sustainability of Buildings: Environmental, Economic and Social Pillars. BIT 2020, X, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, V. The Ethics of Care: Personal, Political, and Global; Oxford University Press: New York, 2005; ISBN 978-0-19-518099-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kittay, E.F. The Ethics of Care, Dependence, and Disability*. Ratio Juris 2011, 24, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddick, S. Care as Labor and Relationship. In Norms and Values: Essays on the Work of Virginia Held; Haber, J.G., Halfon, M.S., Eds.; Rowman and Littlefield: Lanham, 1998; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Tronto, J.C. Caring Democracy: Markets, Equality, and Justice; New York University Press: New York, 2013; ISBN 978-0-8147-8277-4. [Google Scholar]

-

Architectures of Care: From the Intimate to the Common; Utting, B., Ed.; Routledge: London, 2023; ISBN 978-1-032-28377-7.

- Davis, J. The Caring City: Ethics of Urban Design; Bristol University Press: Bristol, 2022; ISBN 978-1-5292-0122-2. [Google Scholar]

- Critical Care. Architecture and Urbanism for a Broken Planet; Fitz, A., Krasny, E., Eds.; The MIT Press, 2019; ISBN 978-0-262-35287-1.

- Chinchilla, I. La Ciudad de Los Cuidados; Los Libros de la Catarata: Madrid, 2020; ISBN 978-84-1352-087-2. [Google Scholar]

- Duboy-Luengo, M.; Muñoz-Arce, G. La Sostenibilidad de La Vida y La Ética Del Cuidado: Análisis y Propuestas Para Imaginar La Intervención de Los Programas Sociales En Chile. Asparkia 2022, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, C. La Sostenibilidad de La Vida Humana: ¿un Asunto de Mujeres? Mientras Tanto 2001, 43–70. [Google Scholar]

-

Feminist Political Ecology and the Economics of Care: In Search of Economic Alternatives; Bauhardt, C., Harcourt, W., Eds.; Routledge: Oxon, 2019; ISBN 978-1-315-64874-3.

- Mahon, R.; Robinson, F. Feminist Ethics and Social Policy: Towards a New Global Political Economy of Care; UBC Press, 2011; ISBN 978-0-7748-2108-7.

- del Valle, T. Contenidos y significados de nuevas formas de cuidado. In Congreso Internacional Sare 2003: Cuidar cuesta: costes y beneficios del cuidado; Emakunde: Vitoria-Gasteiz, 2004; pp. 39–62. ISBN 978-84-87595-96-7. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Orozco, A. Cadenas Globales de Cuidado: ¿Qué Derechos Para Un Regimen Global de Cuidados Justo?; Instituto Internacional de Investigaciones y Capacitación de las Naciones Unidas para la Promoción de la Mujer (UN-INSTRAW), 2010. =. [Google Scholar]

-

El trabajo de cuidados: historia, teoría y políticas; Carrasco, C., Borderías, C., Torns, T., Eds.; Los Libros de la Catarata: Madrid, 2011. ISBN 978-84-9097-737-8.

- Rodríguez Enríquez, C. Economía Feminista y Economía Del Cuidado. Aportes Conceptuales Para El Estudio de La Desigualdad. Nueva Sociedad 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, Y. Miradas Ecofeministas Para Transitar a Un Mundo Justo y Sostenible. Revista De Economía Crítica 2021, 2, 278–307. [Google Scholar]

- Branicki, L.J. COVID-19, Ethics of Care and Feminist Crisis Management. Gender Work & Organization 2020, 27, 872–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, F. Global Health and the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Care Ethics Approach. Journal of Global Ethics 2021, 17, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevenhuijsen, S. The Place of Care: The Relevance of the Feminist Ethic of Care for Social Policy. Feminist Theory 2003, 4, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruddick, S. An Appreciation of Love’s Labor. Hypatia 2002, 17, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Fenster, T. Architecture of Care: Social Architecture and Feminist Ethics. The Journal of Architecture 2021, 26, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koźmińska, U.; Schalk, M.; Nawratek, K.; Frisk, J. Caring Architecture for Human and More-than-Human Coexistence. In Proceedings of the Gender and Diversity Dialogues; The Danish Architectural Press; 2024; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Col·lectiu Punt 6 Urbanismo Feminista. Por Una Transformación Radical de Los Espacios de Vida; Virus Editorial: Barcelona, 2019; ISBN 978-84-92559-99-2. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez Isidro, E.M.; Gómez Alfonso, C.J. Recomendaciones Para La Incorporación de La Perspectiva de Género En El Planeamiento Urbano. CITECMA 2017, 1, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann Alcocer, A. El Espacio Doméstico: La Mujer y La Casa, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, 2005.

- Muxí Martínez, Z. Mujeres, casas y ciudades: más allá del umbral; dpr-barcelona: Barcelona, 2019; ISBN 978-84-949388-4-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez de Madariaga, I. Mobility of Care: Introducing New Concepts in Urban Transport. In Fair Shared Cities: the Impact of Gender Planning in Europe; Routledge: London, 2016 ISBN 978-1-317-13683-5.

- Gutiérrez Valdivia, B. La Ciudad Cuidadora: Calidad de Vida Urbana Desde Una Perspectiva Feminista, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, 2021.

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated Guidance and Exemplars for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Evans, C.; De Moraes, É.B.; Godfrey, C.M.; Pieper, D.; et al. Recommendations for the Extraction, Analysis, and Presentation of Results in Scoping Reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis 2023, 21, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilligan, C. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Mass, 1982; ISBN 978-0-674-97096-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg, L. Moral Stages and Moralization: The Cognitive-Developmental Approach. In Moral Development and Behavior: Theory, Research, and Social Issues; Lickona, T., Ed.; Holt, Rinehart, & Winston: New York, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan, C. Letter to Readers, 1993. In In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development; Harvard University Press, 1993; pp. ix–xxviii ISBN 978-0-674-03761-8.

- Noddings, N. Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education; Univ. of California Press: Berkeley, 1986; ISBN 978-0-520-23864-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kittay, E.F. Love’s Labor: Essays on Women, Equality and Dependency; Routledge: New York, NY, 1999; ISBN 978-1-138-08991-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhse, H. Clinical Ethics and Nursing: “Yes” to Caring, but “No” to a Female Ethics of Care. Bioethics 1995, 9, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha-Sridhar, I. Care as a Thick Ethical Concept. Res Publica 2023, 29, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, V. Care as Practice and Value. In The Ethics of Care; Oxford University Press: New York, 2005; pp. 29–43. ISBN 978-0-19-518099-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sevenhuijsen, S. Citizenship and the Ethics of Care: Feminist Considerations on Justice, Morality and Politics; Routledge, 1998; ISBN 978-1-134-69724-3.

- Gabauer, A.; Knierbein, S.; Cohen, N.; Lebuhn, H.; Trogal, K.; Viderman, T.; Haas, T. Care and the City: Encounters with Urban Studies; Routledge: New York, 2021; ISBN 978-1-003-03153-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Orozco, A. Subversión feminista de la economía: aportes para un debate sobre el conflicto capital-vida; Traficantes de Sueños: Madrid, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Picchio, A. La economía política y la investigación sobre las condiciones de vida. In Por una economía sobre la vida: aportaciones desde un enfoque feminista; Icaria Editorial: Barcelona, 2005 ISBN 978-84-7426-791-4.

- Tronto, J.C. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care; Routledge: New York, 1993; ISBN 978-1-003-07067-2. [Google Scholar]

- Tronto, J.C. Caring Architecture. In Critical Care: Architecture and Urbanism for a Broken Planet; Fitz, A., Krasny, E., Eds.; The MIT Press, 2019; pp. 26–32 ISBN 978-0-262-35287-1.

- Mogollón García, I.; Fernández Cubero, A. Arquitecturas del cuidado: hacia un envejecimiento activista; Icaria: Barcelona, 2019; ISBN 978-84-9888-928-4. [Google Scholar]

- Puig de la Bellacasa, M. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4529-5346-5. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. On Actor-Network Theory: A Few Clarifications. Soziale Welt 1996, 47, 369–381. [Google Scholar]

-

The Care Manifesto: The Politics of Interdependence; The Care Collective, Ed.; Verso books: London New York (N.Y.), 2020; ISBN 978-1-83976-096-9.

- Lefebvre, H. Le droit à la ville; Anthropologie; Anthropos: Paris, 1968; ISBN 978-2-7178-5708-5. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M.J. Care-full Justice in the City. Antipode 2017, 49, 821–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- pirate.care The Pirate Care Project. Available online: https://pirate.care/pages/concept/ (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- Graziano, V.; Medak, T.; Mars, M. When Care Needs Piracy: The Case for Disobedience in Struggles against Imperial Property Regimes. Soundings 2021, 77, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. We Have Never Been Modern; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 1993; ISBN 978-0-674-94838-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Life between Buildings: Using Public Space; Island Press: Washington, DC, 2011; ISBN 978-1-59726-827-1. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; The MIT Press: Cambridge, 1960; ISBN 978-0-262-12004-3. [Google Scholar]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three Pillars of Sustainability: In Search of Conceptual Origins. Sustain Sci 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memmott, P.; Keys, C. Redefining Architecture to Accommodate Cultural Difference: Designing for Cultural Sustainability. Architectural Science Review 2015, 58, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosaleny Gamón, M. Parameters Of Sociocultural Sustainability In Vernacular Architecture. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2020, XLIV-M-1–2020, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Barth, T.D.; Campbell, D.F. The Quintuple Helix Innovation Model: Global Warming as a Challenge and Driver for Innovation. J Innov Entrep 2012, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Campbell, D.F.J. Triple Helix, Quadruple Helix and Quintuple Helix and How Do Knowledge, Innovation and the Environment Relate To Each Other? : A Proposed Framework for a Trans-Disciplinary Analysis of Sustainable Development and Social Ecology. International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development (IJSESD) 2010, 1, 41–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundación Pilares Principios y Criterios Del Modelo de Atención Integral y Centrada En La Persona (AICP); 2022.

|