1. Introduction

Rumination, a unique digestive trait of ruminants, is a complex biological process. In the daily physiological activities of dairy cows, rumination is critical. Cows usually swallow feed into the rumen without thoroughly chewing during ingestion. Subsequently, forage and feed are soaked and softened in the rumen. When cows rest, food returns to the mouth for rechewing, is mixed with large amounts of saliva, and is then swallowed back into the stomach. This series of processes is called rumination [

1]. This behavior is not only a sign of the normal functioning of a cow’s digestive system but also a direct reflection of its health status. Normal rumination is an important indicator for assessing the health of dairy cows. If a cow suffers from problems, such as hypotonia of the forestomach, food stagnation, bloat, and traumatic reticulitis, its rumination behavior will be considerably affected; furthermore, in severe cases, rumination may even completely cease [

2]. These abnormal phenomena can be signs of underlying diseases. Therefore, monitoring the cow rumination behavior can provide timely insights into a cows’ health status, thereby improving farm management and production efficiency.

However, monitoring the cow rumination behavior in intensive farming environments faces numerous challenges. Cows indulge in various activities and are randomly distributed; hence, camera equipment is often limited by multiple angles and complex outdoor environments. Thus, video-based behavior monitoring is technically challenging, and processes for accurately identifying and tracking the cow rumination behavior are complex. Currently, primary methods for monitoring the cow rumination behavior are divided into two categories: manual observation and contact sensor devices. Manual observation is a traditional monitoring method that involves observing changes in the cow behavior with human eyes and recording data. However, this method is inefficient and labor intensive; therefore, employing it in modern large-scale farms is difficult. Sensors (e.g., acceleration sensors [

3] and pressure sensors [

4]) are currently the most commonly used monitoring tools. These devices can effectively record the time and frequency of the rumination behavior by coming into contact with the cow body. However, a direct contact between these sensors and the cow body may cause stress responses, affecting the cow’s physiological and psychological health. In practical applications, installing and maintaining these devices require considerable amounts of time and effort, rendering them unsuitable for large-scale farms. To overcome these limitations, computer vision technology for cow behavior monitoring has gradually become a research focus. By analyzing video data, noncontact and automated behavior recognition can be achieved, providing important support for cow health management.

In recent years, research on the application of the computer vision technology to animal behavior monitoring has progressed. Song et al. [

5] proposed an automatic detection method based on the Horn–Schunck optical flow method for multitarget cow mouth regions. Ji et al. [

6] presented an analysis method for the cow rumination behavior based on an improved FlowNet2.0 optical flow algorithm. Although optical flow algorithms perform satisfactorily under specific conditions, they have obvious limitations. In image regions with weak textures or significant overlaps, these algorithms may not accurately estimate the pixel displacement, decreasing accuracy in behavior monitoring. Mao et al. [

7] utilized the Kalman filter and Hungarian algorithm for multitarget cow mouth tracking and rumination monitoring. Wang et al. [

8] employed computer vision for cow rumination behavior recognition and analysis, using the you only look once (YOLO) [

1,

2] object detection algorithm [

3,

4] and kernelized correlation filter tracking to monitor cow heads in a herd. However, occlusions among cows may occur, leading to errors in the tracking algorithm and thus affecting the accuracy of rumination behavior monitoring.

To address the above issues, this study proposes a novel Biformer–YOLOv7 model based on YOLOv7 that incorporates the bidirectional router attention (Biformer) and Ghost Sparse Convolution (GSConv) technologies. This model is optimized for small-target detection in cow mouth regions and multiview monitoring in complex environments, offering the following advantages: the Biformer module focuses on the feature information of small targets and thus effectively improves the detection accuracy of cow mouth regions, while GSConv technology considerably reduces model computational complexity, enabling the model to adapt to real-time detection requirements in multiangle shooting [

5] and complex outdoor environments. Furthermore, the model exhibits high-precision rumination behavior monitoring under partial occlusion, rainy, and nighttime conditions. This robustness makes it suitable for applications in actual farms. The experimental results show that Biformer-YOLOv7 outperforms traditional YOLO models in terms of the following metrics: mean average precision (mAP), recall rate, detection accuracy, and detection speed. Additionally, the model can accurately analyze the chewing counts and rumination duration of cows, providing a useful reference for cow health management and behavior research.

The intelligent monitoring of the cow rumination behavior is of great significance for improving farming efficiency and cow health management levels. The proposed Biformer–YOLOv7 model not only performs exceptionally in experimental environments but also demonstrates good practicality. In the future, with the further development of deep learning and computer vision technologies, this model is expected to integrate more behavioral data, such as cow movement trajectories and feeding patterns, to provide more comprehensive support for cow health management. Meanwhile, integrating a rumination behavior monitoring system into automated management platforms of large-scale farms can considerably enhance farming efficiency, achieving intelligent and precise dairy cow management.

2. Data Collection and Preprocessing

2.1. Data Collection

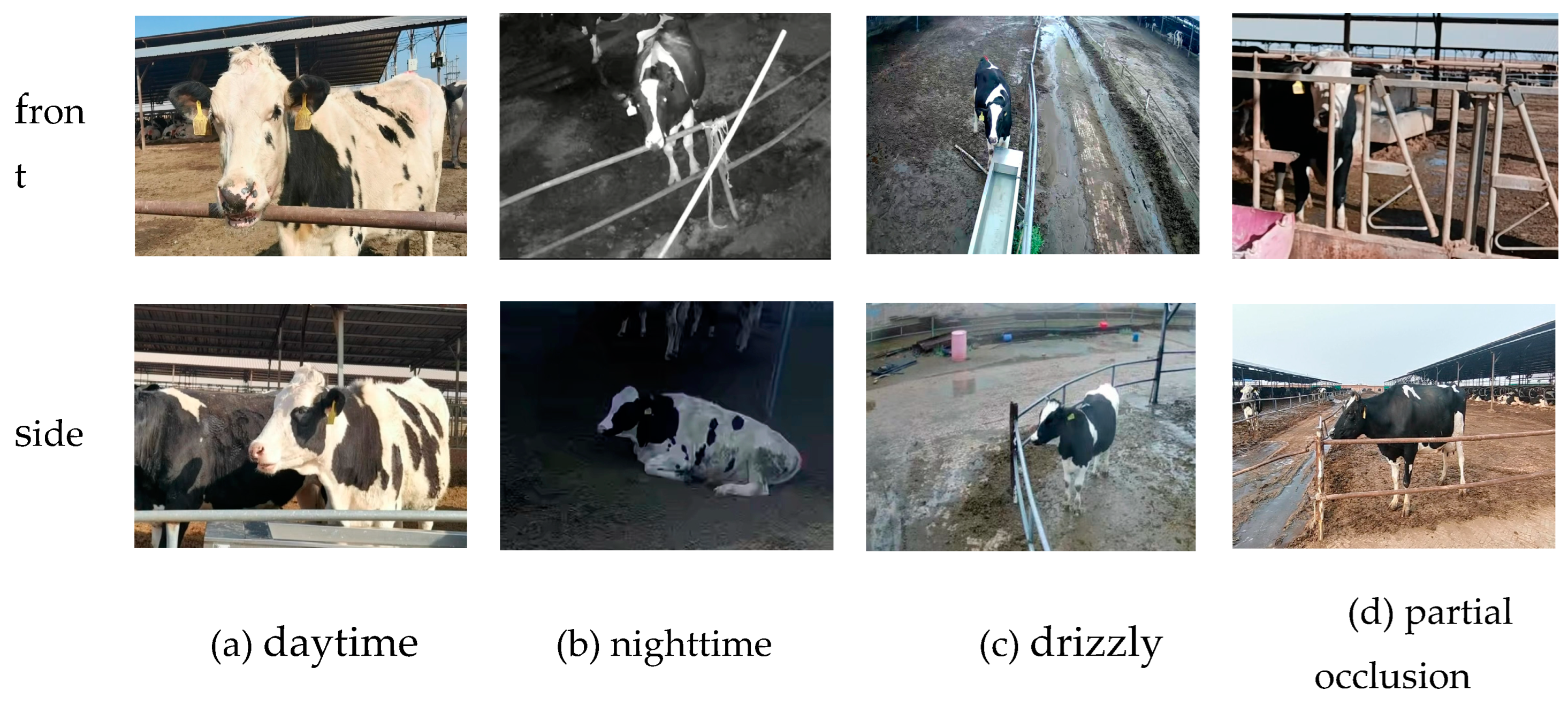

The experimental data were collected from the dairy farm of Pu yuan tai Dairy Cattle Breeding Co., Ltd. in Tai gu District, Jin zhong City, Shanxi Province, from June to July 2022. The collection objects were 20 randomly selected dairy cows, and the duration of a single video clip shot for each dairy cow ranged at 10–300 s. Video data were collected using a camera mounted on a tripod and a remote surveillance camera with a 4G module, which captured the cow rumination behavior at a resolution of 1280 × 720 pixels and a frame rate of 25 frames per second (FPS). The video was then processed into frames using a free video-to-JPG converter, and one frame was extracted every 20 frames. Thus, a total of 1805 images were collected from 20 cows. Figure 1 shows examples of cow rumination under different scenarios.

Figure 1.

Example of cow rumination data.

Figure 1.

Example of cow rumination data.

2.2. Data Preprocessing

2.2.1. Data Augmentation

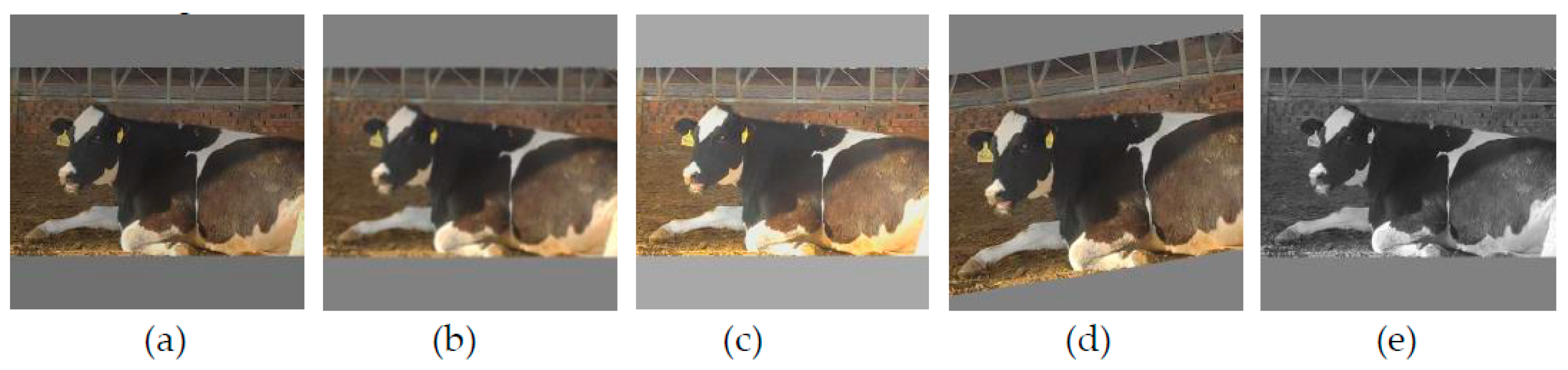

The framed data were enhanced by adding grayscale bars and adjusting the image size to 608 × 608 pixels. In cow rumination images captured in complex environments, collected samples from different environments exhibit data imbalance. Therefore, targeted data augmentation was necessary. Four methods—image blurring, color jittering, random rotation, and conversion to grayscale—were employed to augment the dataset for reducing imbalance in the sample data. The effect is shown in

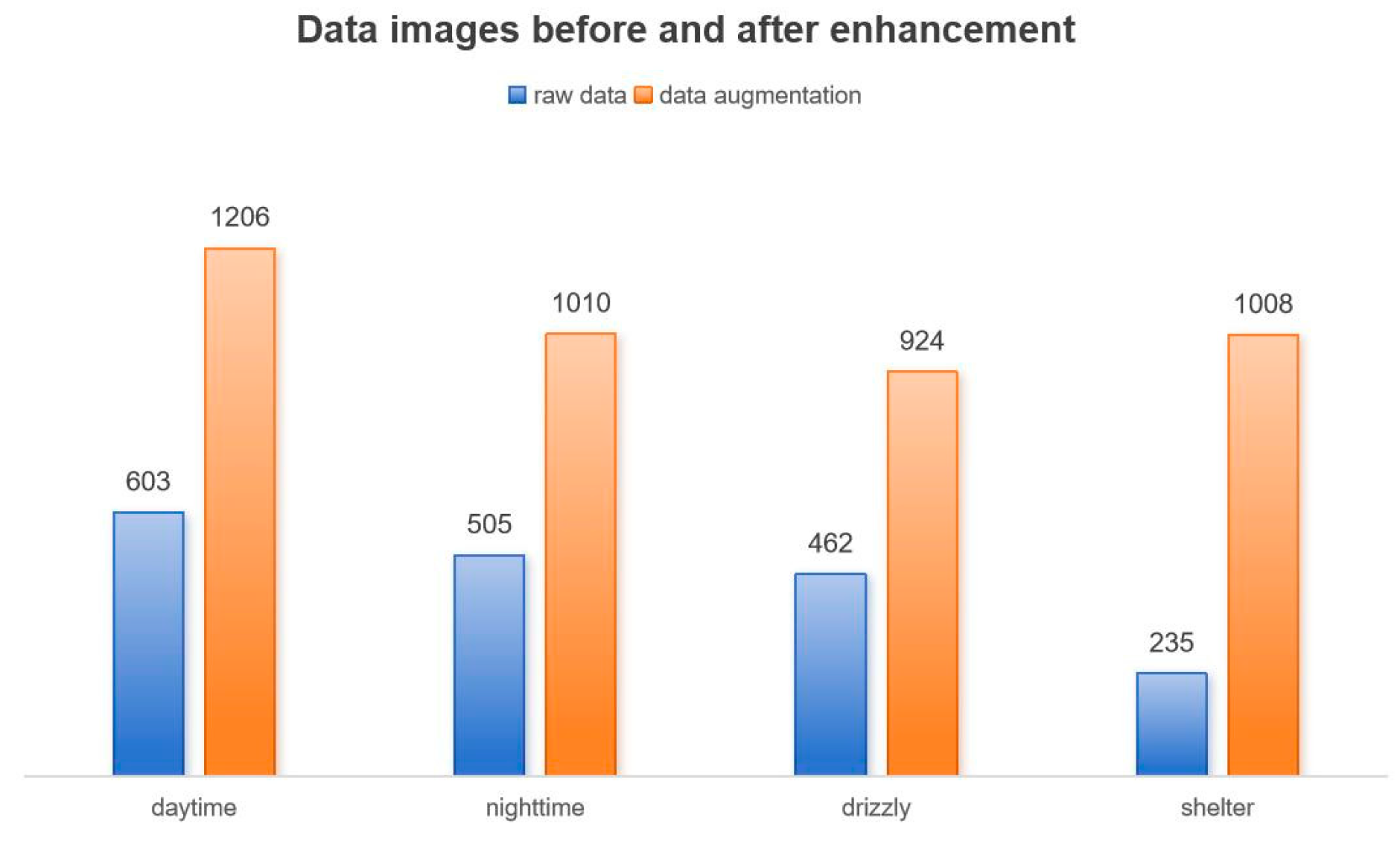

Figure 2. After data augmentation, the dataset increased from the original 1805 images to 4148 images. The data distribution before and after augmentation is shown in

Figure 3.

2.2.2. Data Annotation

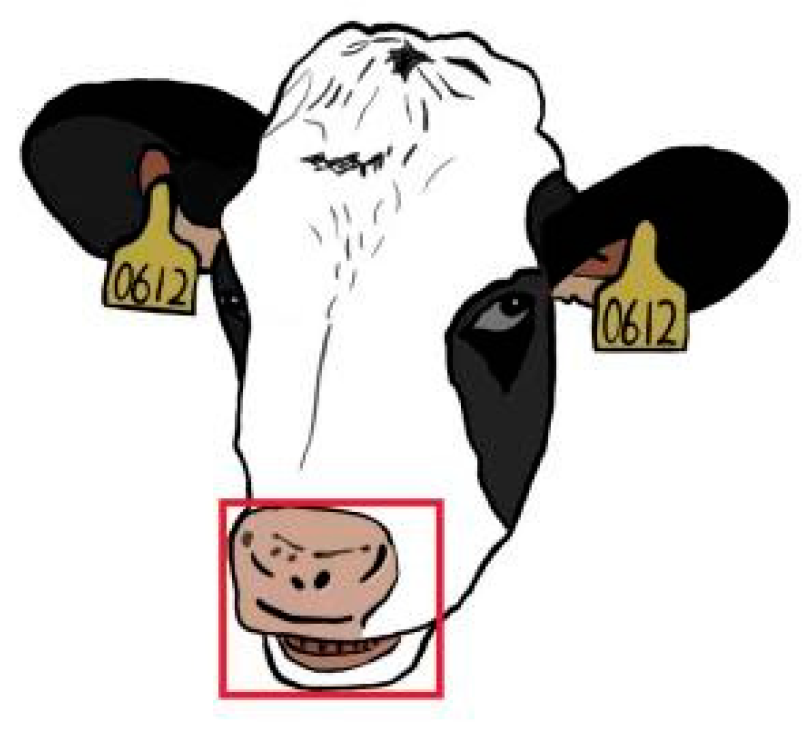

Data annotation LabelImg was used to manually label the filtered and classified cow rumination images with the label “mouth.” The generated label file was an XML file in the VOC format. To ensure the complete inclusion of the mouth area of a cow, the upper boundary of the frame was aligned with the upper edge of the cow’s nostril, the left boundary started at the left corner of the cow’s mouth, the lower boundary extended to the lower edge of the lower lip, and the right boundary was aligned with the right corner of the cow’s mouth. The following figure shows an example of a cow’s beak area labeling (

Figure 4) [

6,

7].

2.3. Dataset Division

All 4148 images were divided into training (3318 images), validation (415 images), and test sets (415 images) in the 8:1:1 ratio. The training and validation sets were used for model training and parameter tuning for model performance optimization. The test set was used to evaluate trained model performance, assessing its generalization ability and accuracy on unseen data and thus providing a more comprehensive evaluation of the model.

3. Model Construction

3.1. YOLOv7 Network Architecture

YOLOv7 [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] comprises a backbone network and a detection head network, achieving rapid and accurate object detection by extracting image features. Initially, an input image undergoes feature extraction through the backbone network, which can extract the high-level features of the image. Subsequently, the extracted features pass through the detection head network to generate bounding boxes and class predictions for the objects. Within the detection head network, a multiscale prediction strategy is adopted to perform object detection on feature maps of different scales, thereby enhancing sensitivity to objects of varying sizes [

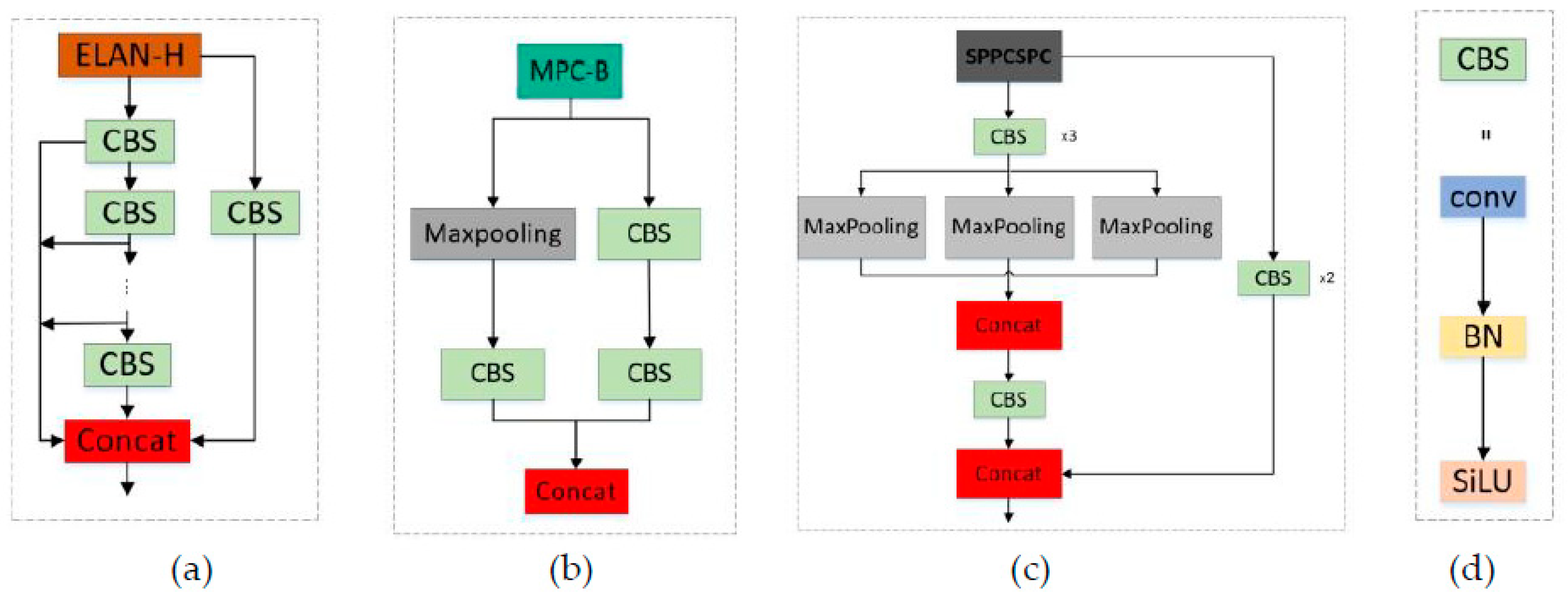

13]. The YOLOv7 model includes the following multiple, highly integrated convolutional operation modules: the Efficient Layer Aggregation Network-Hierarchical (ELAN-H), Message Passing Convolution-Block (MPC-B), Spatial-Pyramid-Pooling-Cross-Stage-Partial-Connections (SPPCSPC), and Convolutional Block with Skip-connection (CBS) modules. The network architecture is illustrated in

Figure 5(a)–(d). These integrated structures considerably contribute to optimizing the model structure and enhancing feature extraction capabilities.

3.1.1. Biformer Network Structure

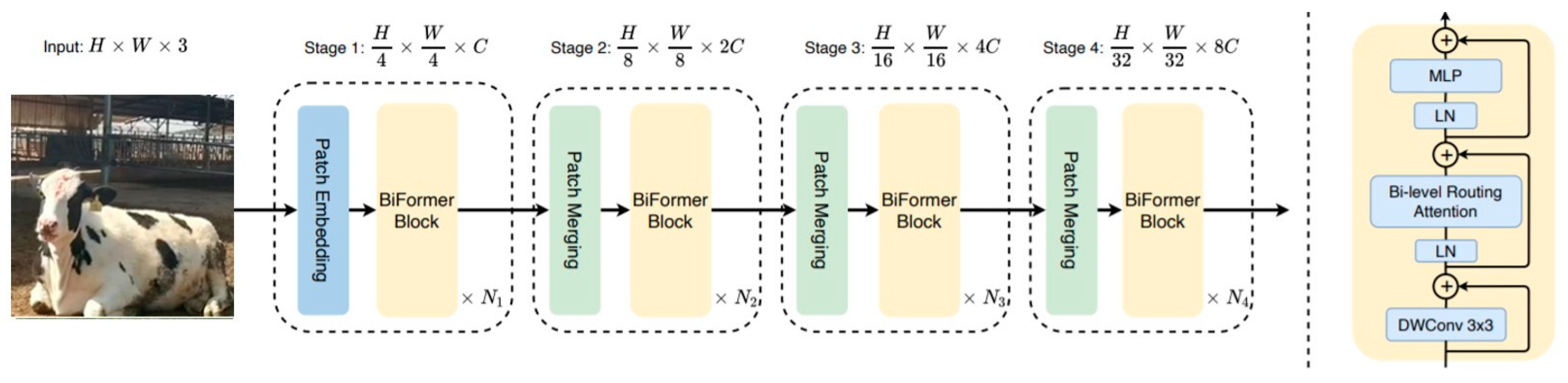

To address the potential issue of feature redundancy during the feature extraction process, the Biformer attention module [

14] is introduced into the SPPCSPC module of the original model for enhancing model accuracy through feature weighting. Biformer is a double-routing based on the Transformer architecture, which performs multiple calculations between different layers of the encoder and decoder to fully utilize information in the input sequence. This mechanism enables Biformer to globally model and represent the input at multiple levels. The model structure is illustrated in

Figure 6. By introducing the Biformer attention module, we can better handle correlations between features, reducing the impact of redundant information and thus improving model performance and generalization ability.

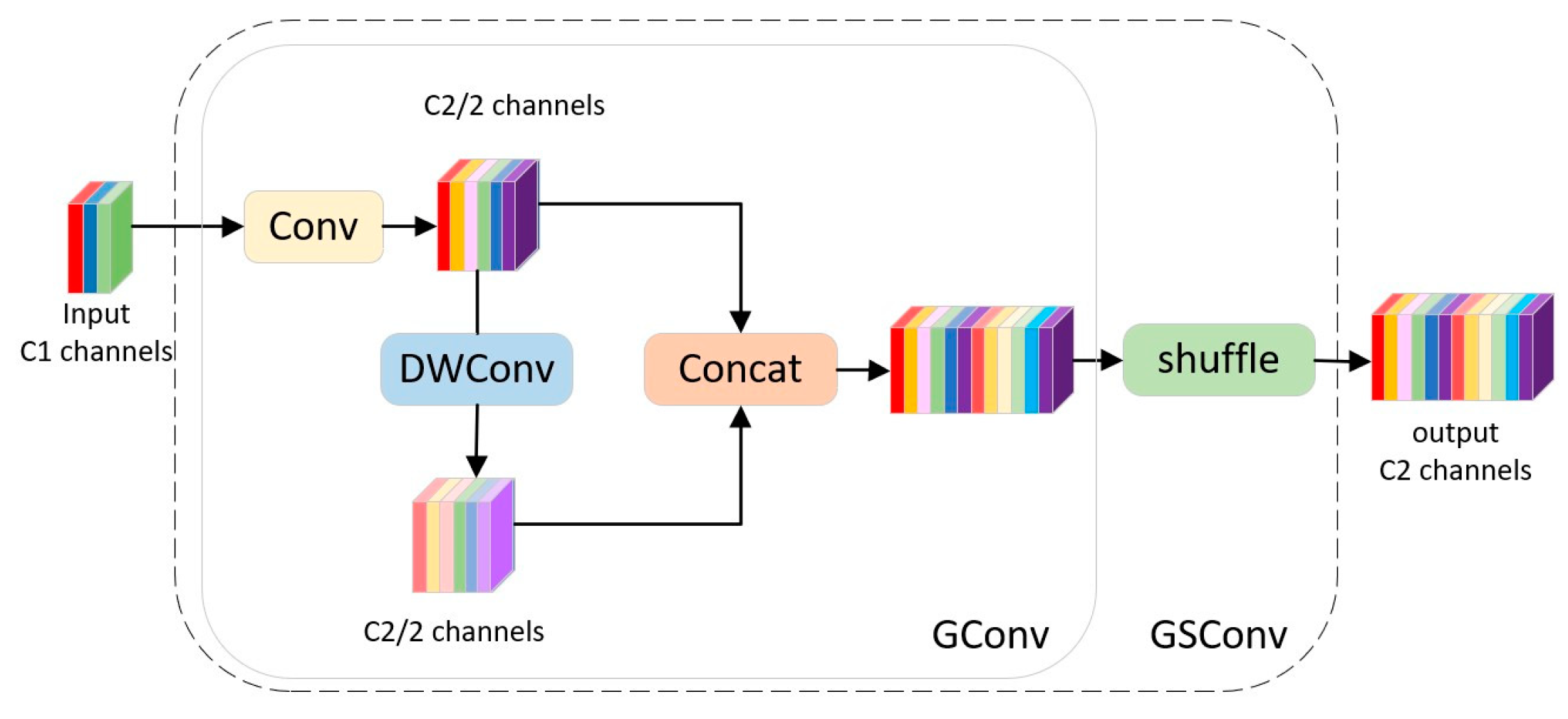

3.1.2. GSConv Network Architecture

To address the issue that lightweight models constructed with a large number of depth-wise-separable convolutional layers fail to achieve sufficient accuracy, this study replaces all Conv modules in the head section with GSConv [

15,

16] (ghost sparse convolution). As shown in

Figure 7, this approach reduces model burden while maintaining its accuracy. By empolying the GSConv network architecture, good balance is achieved between model accuracy and speed, thereby realizing a more superior lightweight model. This innovative approach enables the model to maintain outstanding performance even under limited resource conditions.

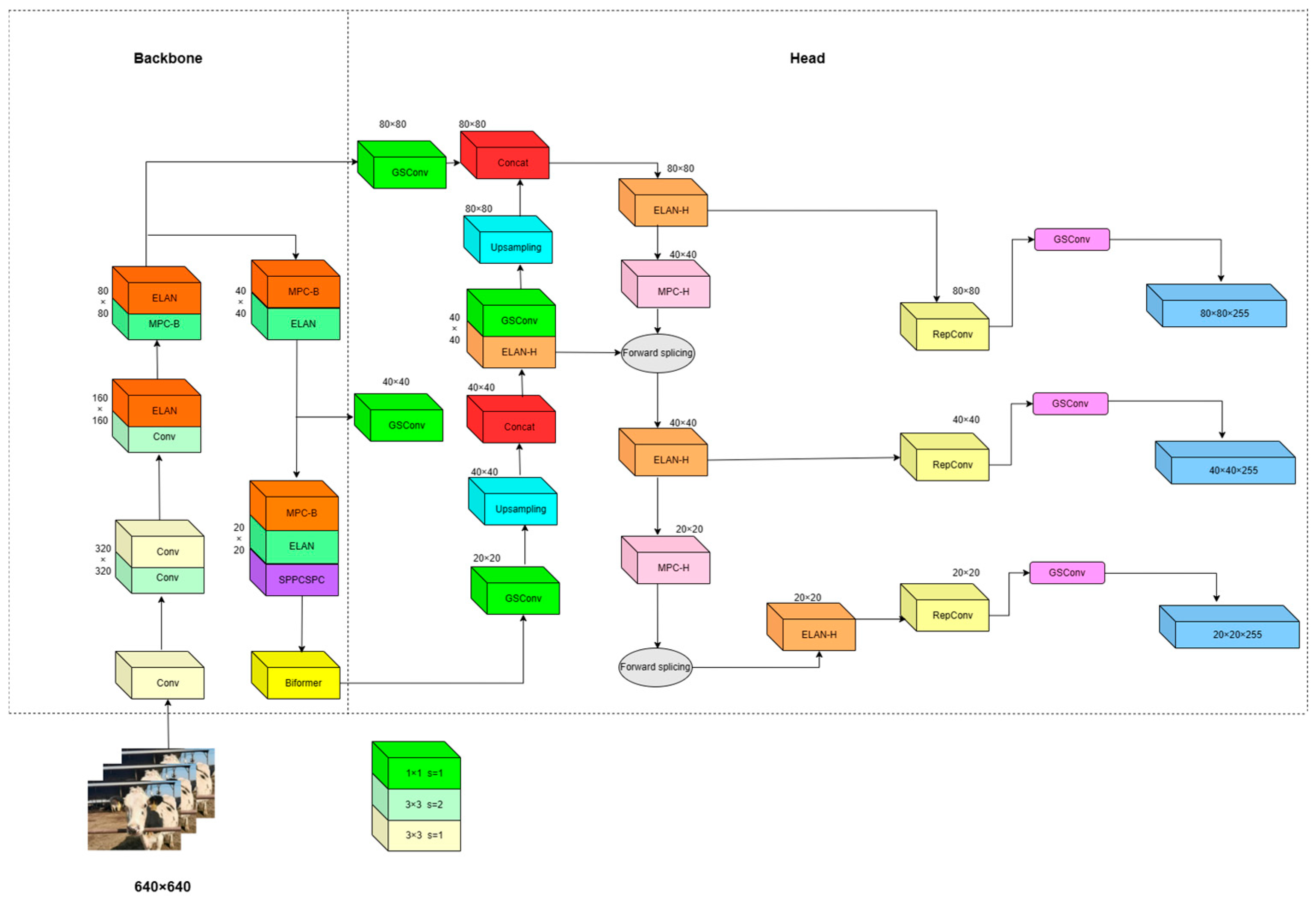

3.1.3. Network Architecture of Biformer–YOLOv7

An effective combination of the aforementioned modules with the SPPCSPC and GSConv module constitutes the basic structure of the Biformer–YOLOv7 model, as illustrated in

Figure 8. The integration of these modules enables the Biformer–YOLOv7 model to excel in object detection tasks while achieving ideal balance between computational efficiency and model accuracy.

4. Experiment Identification Methods for Cow Rumination Behavior

4.1. Definition of Cow Rumination Behavior

Cow rumination typically occurs 0.5–1 h after eating. Cows generally spend 6–8 h or even longer ruminating each day, and the specific duration depends on the type of diet. Feed with a high crude fiber content requires a longer time for rumination. The rumination cycle is usually 14–17 times, and each rumination lasts 40–50 min. During each rumination, cows spend ~1 min to chew each bolus before swallowing it again [

17,

18,

19]. After a break, cows begin their second rumination session. Through rumination, large amounts of forage become softer and can pass through the cow’s stomach into the subsequent digestive tract more quickly, enabling cows to consume more forage and absorb more nutrients. To ensure normal rumination, cows should have sufficient rest time and a quiet and comfortable environment after eating.

4.2. Identification Methods for Cow Rumination Behavior

Rumination is a complex, physiological, reflex process comprising four stages: regurgitation, rechewing, saliva mixing, and swallowing [

20]. Among these, the first and fourth stages are relatively short, while the second and third stages are the primary subjects of this study. By deeply investigating the cows’ chewing behavior during the second and third stages, we can better understand their rumination process and digestive efficiency, which is crucial for optimizing cow feeding management and improving feed utilization efficiency.

4.3. Model for Determining Cow Chewing Frequency and Counts

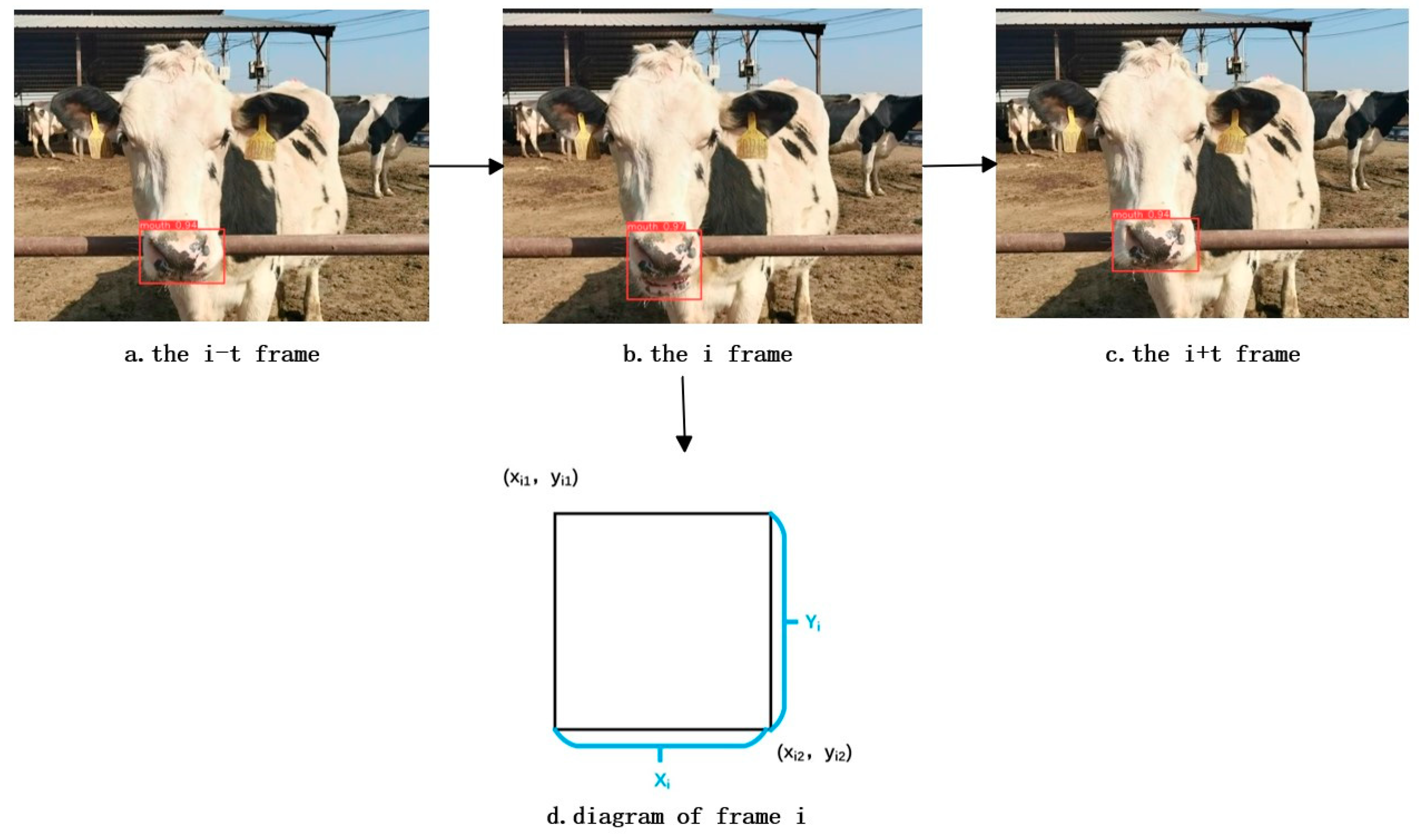

The chewing process of cows can be described as follows. When cows chew, the mouth area undergoes continuous “close–open–close” changes, as shown in

Figure 9 (a–c). During this process, the tracking box around the mouth area adjusts with the chewing motion. We can reflect these changes by calculating the sum of the height and width of the tracking box in each frame, as shown in

Figure 9 (d). In the video sequence, the mouth area of each cow is tracked, and tracking box information includes the coordinates of the top-left and bottom-right. By analyzing changes in these coordinates, we can plot a curve of cow chewing. This curve helps us better understand the cows’ eating behavior and chewing habits. The calculation principles are expressed in Formulas (1) – (3).

In the formula, yi2 and yi1 are the vertical coordinates of the top-left and bottom-right corners and xi2 and xi1 are the horizontal coordinates of the top-left and bottom-right corners, respectively, Xi is the width, Yi is the height, and Hi is the sum of the width and height of the tracking box.

The rumination behavior can be identified by drawing a chewing curve based on changes in the cows’ mouth areas. When the mouth area changes from closed to open, the tracking box of the mouth area gradually increases, i.e., the H value (height-to-width value of the tracking box) gradually increases, showing an upward trend on the rumination chewing curve. When the mouth is fully open, the tracking box is at its largest value, i.e., the H value is at its maximum, appearing as a maximum point on the rumination chewing curve. When the mouth area changes from open to closed, the tracking box gradually decreases, i.e., the H value gradually declines, showing a downward trend on the rumination chewing curve. When the mouth is closed, the tracking box is at its smallest value, meaning that the H value is a minimum, appearing as a minimum point on the rumination chewing curve [

21,

22,

23]. Therefore, the occlusion state of a cow’s mouth area can be effectively determined based on the rumination chewing curve.

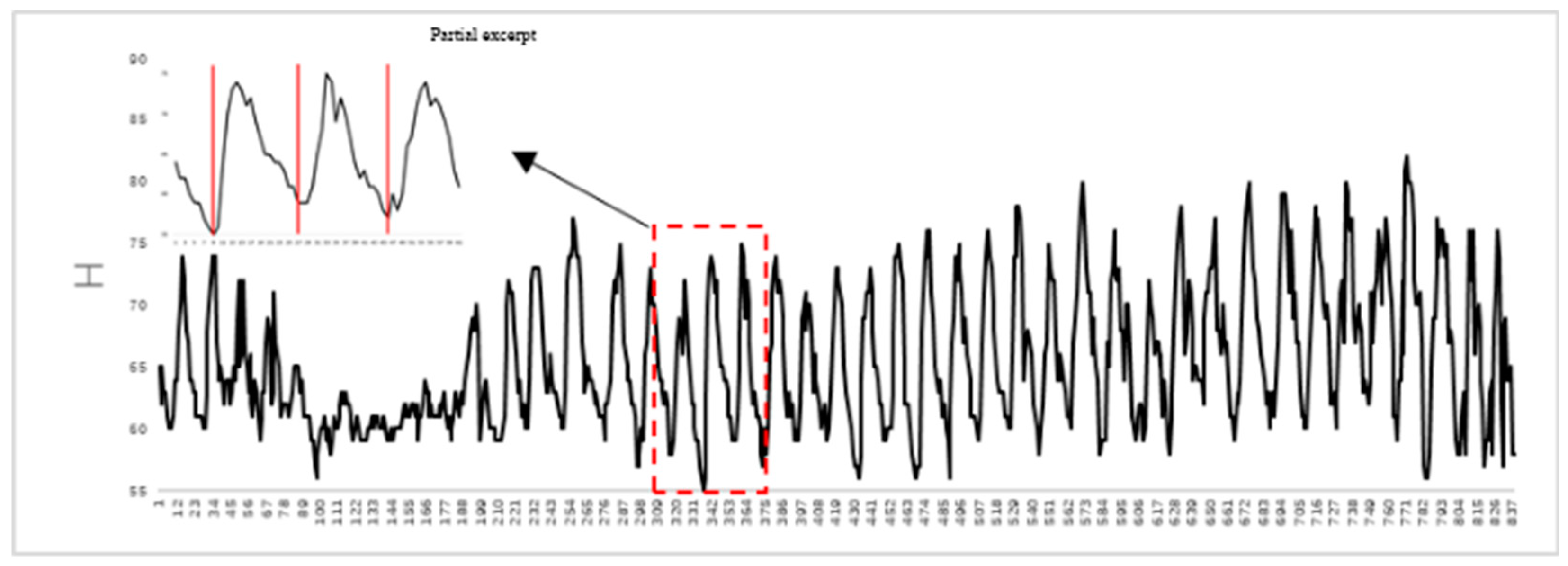

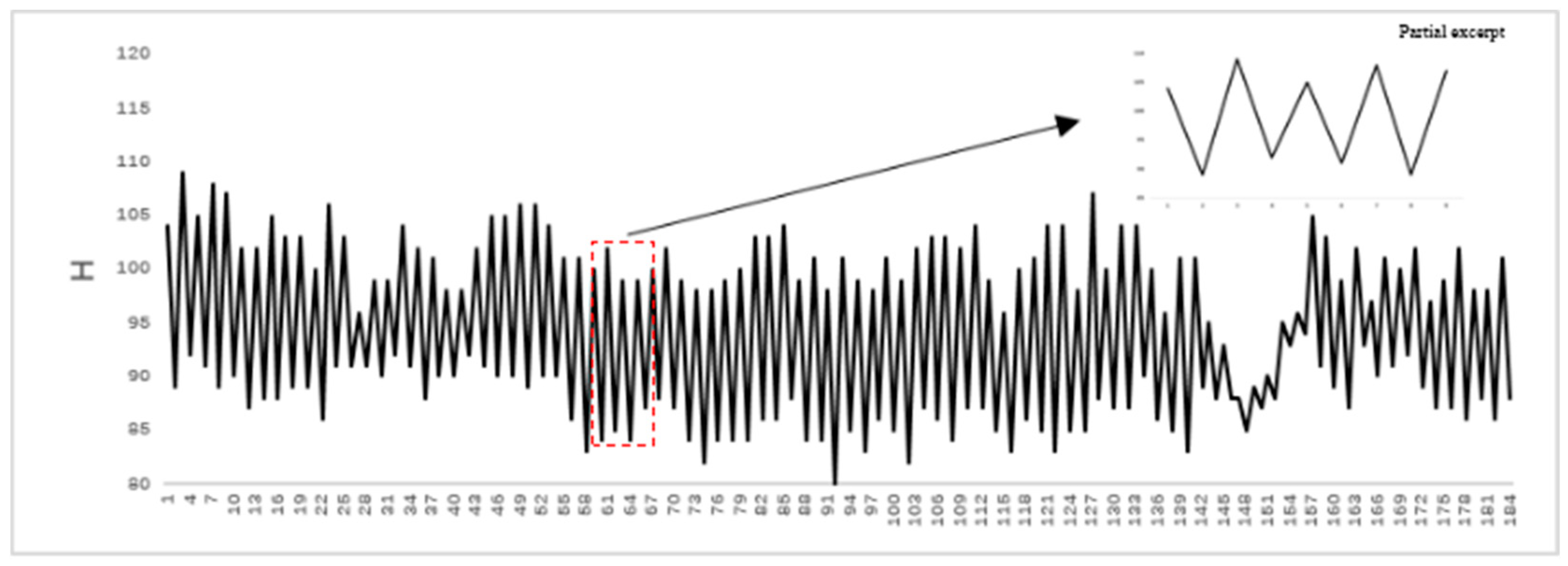

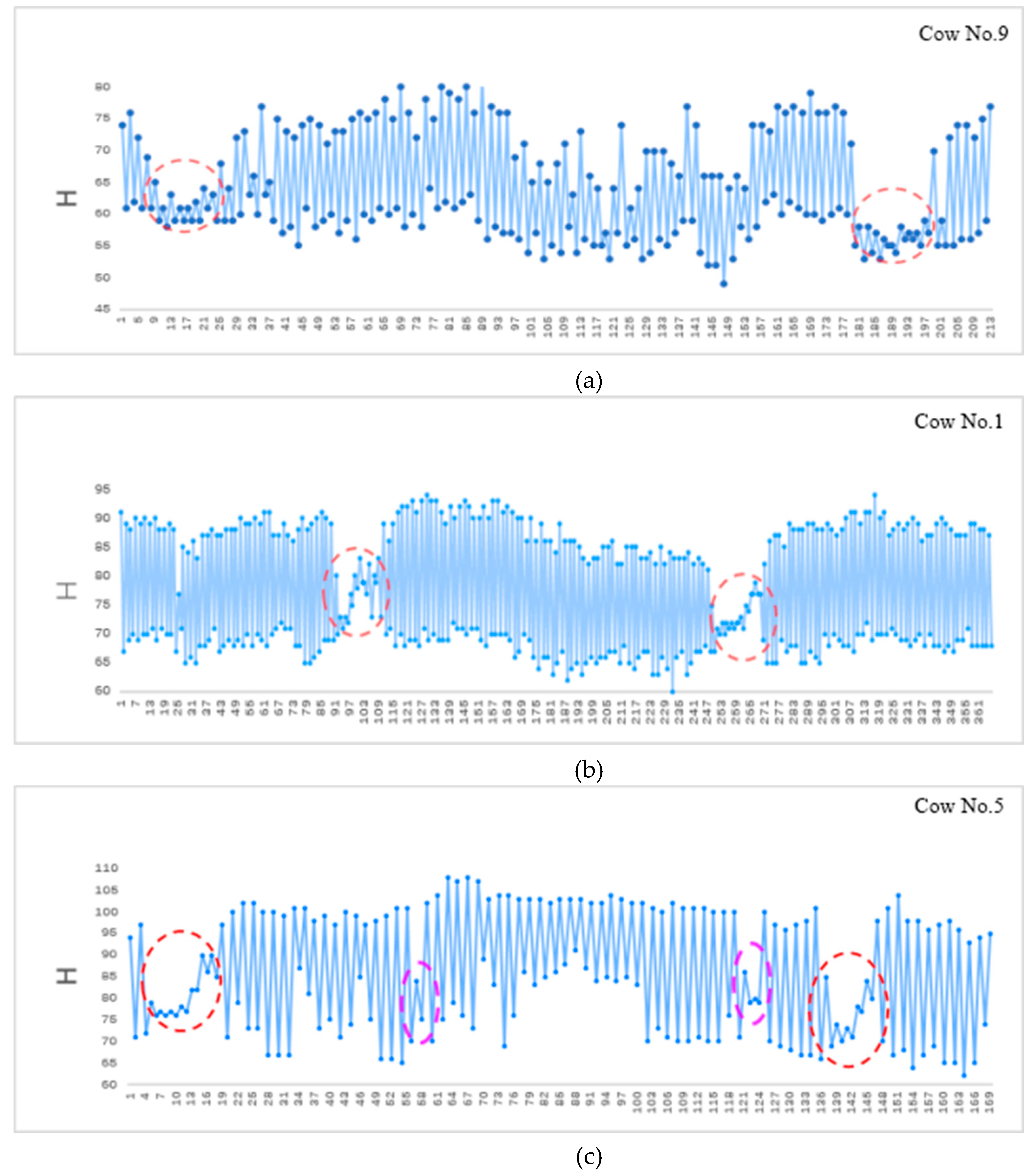

Figure 10 shows the correspondence between the occlusion state of a cow’s mouth and rumination chewing curve, and top-left corner displays an enlarged view of some extracted frames.

The chewing curve is established based on changes in the tracking box of the cows’ mouth areas (

Figure 11). Each chewing event by a cow lasts for 18–25 frames. Given that coordinate information for each frame is recorded during chewing, interference points appear. To remove these points, the following steps are taken.

(1) Identify a maximum value within the first 25 frames as the starting point Mi:Mi = max(1,2,…,25).

(2) Find a minimum value mi within 12 frames starting from Mi:mi = min(Mi, Mi+1,…, Mi+11).

(3) Locate a maximum value Mi+1 within 12 frames starting from mi:Mi+1 = max(mi, mi+1,…, mi+11).

(4) Repeat steps 2 and 3 iteratively for obtaining cow’s chew times.

5. Results and Analysis

This study utilized the Ubuntu 18.04 operating system for hardware and paired this system with Tesla K80 (24G) for use as the computing device. For the software CUDA 10.4 and cudnn 8.2 were selected as the acceleration libraries for deep learning, and PyTorch was adopted as the deep learning framework. In experiments, batch training was performed, with the initial learning rate of the model set to 0.001. To thoroughly train the model, the number of iterations (epochs) was set to 300 and batch size was 16.

5.1. Analysis of Mouth Region Detection Model Results

5.1.1. Comparative Analysis of Training Processes

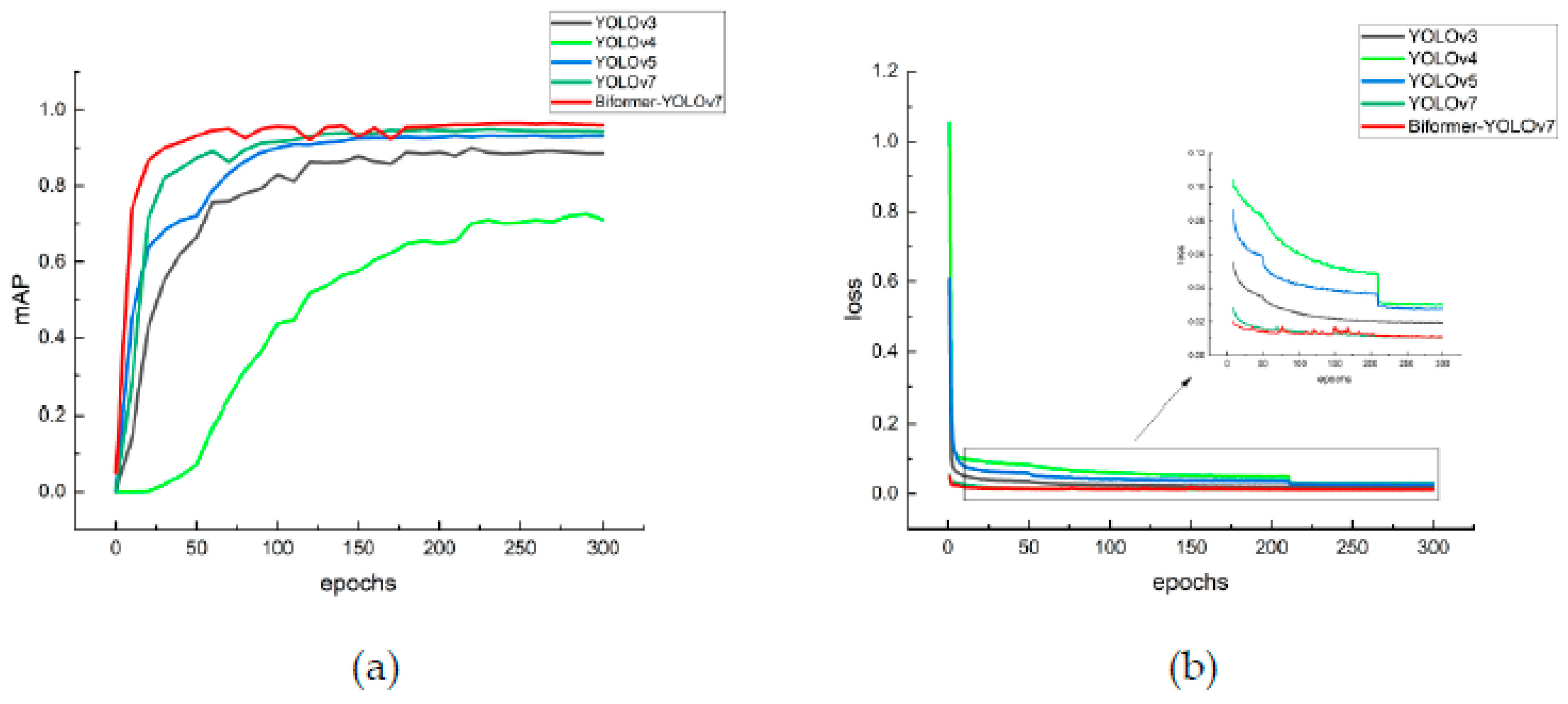

To verify the performance of the Biformer–YOLOv7 model for cow mouth region recognition proposed in this study, the YOLOv3, YOLOv4, YOLOv5, YOLOv7, and Biformer–YOLOv7 models were trained on the same dataset and under the same experimental conditions. During the training process of each model, the change curves of the mAP@0.5/IoU = 0.5 metric and loss value on the validation set are shown in

Figure 12.

The average precision of the five models continuously increases with the number of training epochs (

Figure 12(a)). Except for YOLOv4, the other models converge quickly within the first 50 epochs and then tend to plateau. However, YOLOv4 gradually (only after 225 epochs), and its mAP value is lower than those of the other models. For improved Biformer–YOLOv7, slight fluctuations are observed between the 75th and 175th epochs. This may be due to the randomness of some components in Biformer–YOLOv7, such as random data augmentation and random weight initialization, causing slight differences in model performance during each training; this results in small fluctuations in the mAP value. Notably, these fluctuations disappear after the 175th epoch, and Biformer–YOLOv7 outperforms YOLOv7.

In

Figure 12(b), the five models exhibit the fastest convergence (within the first 50 epochs). After training for ~212 epochs, the loss value curves tend to plateau. For Biformer–YOLOv7, slight fluctuations are noticed between the 75th and 175th epochs; however, after the 175th epoch, fluctuations disappear and the curves flatten out. Overall, Biformer–YOLOv7 performs better than the other four models because it is more stable and has higher accuracy after convergence. However, YOLOv4 converges notably slower; therefore, additional measures may be required during training to accelerate convergence and improve performance.

5.1.2. Comparison of Different Detection Models

To verify the detection performance of the Biformer–YOLOv7 model for the mouth area detection of dairy cows, this study compared target detection models YOLOv3, YOLOv4, YOLOv5, YOLOv7, and Biformer–YOLOv7. During training, pretrained weights provided by the official sources were used, and all networks were trained using the same dataset. A total of 415 images were used as the test set to evaluate model performance using precision (P), recall (R), F1 score (F1), mAP, FPS, and model size (MB). The recognition results of different models are shown in In

Table 1, compared with YOLOv3, YOLOv4, YOLOv5, and YOLOv7, Biformer–YOLOv7 exhibits higher values for precision (P), Recall (R), F1 score, mAP, and FPS. Among them, Biformer–YOLOv7 has the smallest model size, except for YOLOv5. When comparing Biformer–YOLOv7 with YOLOv7, Biformer–YOLOv7 demonstrates a mAP of 95.90% and an FPS of 35.6 FPS for detecting a cow's mouth area. Compared to YOLOv7, Biformer–YOLOv7 displays improvements in mAP by 1.65% and FPS by 9.89 FPS, with a reduction in the model size by 37MB to 102MB. In summary, the Biformer–YOLOv7 model exhibits improvements in model accuracy, recall, F1 score, mAP, and FPS while reducing the model size, demonstrating the effectiveness of the improved model.

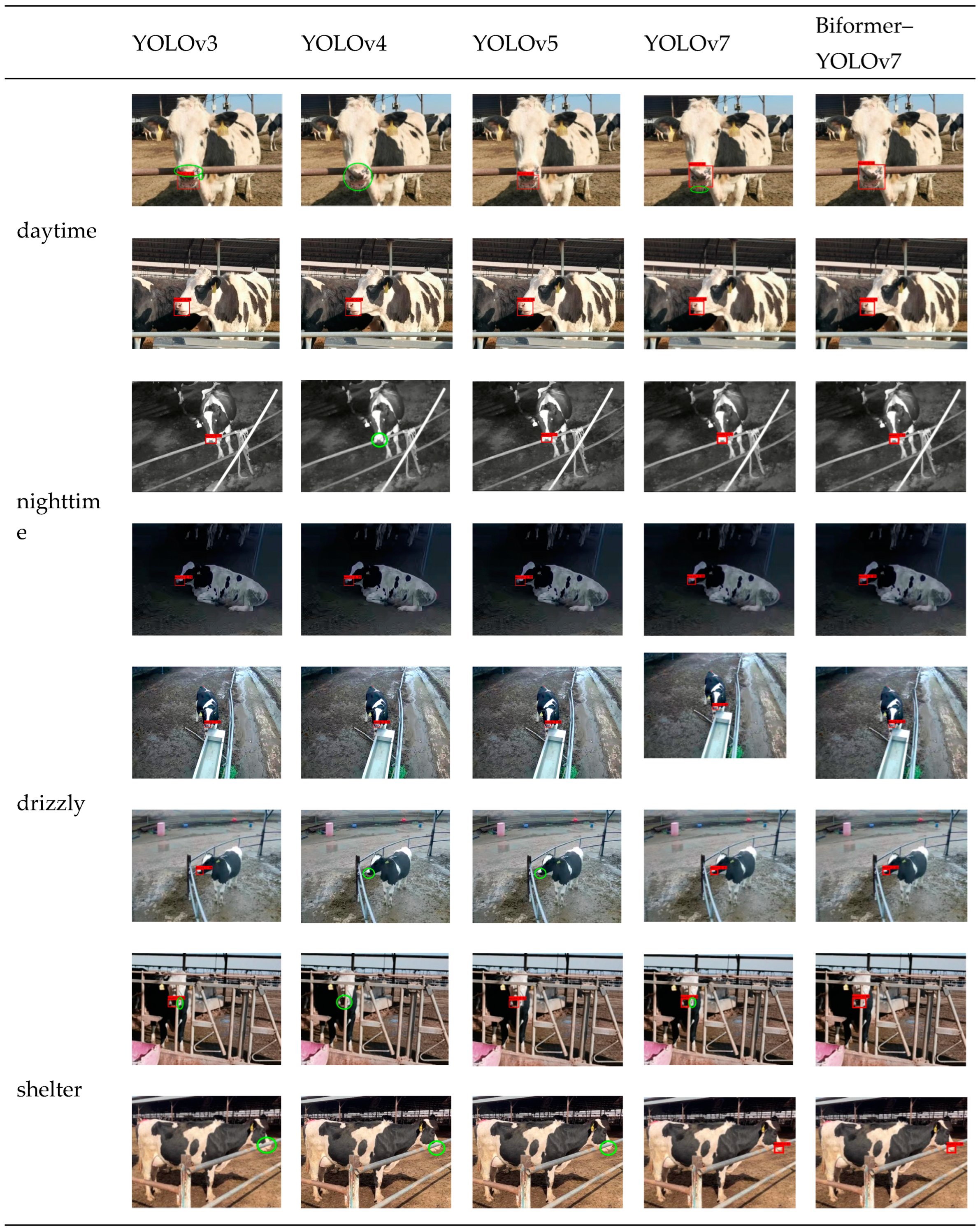

5.1.3. Analysis of the Detection Results in Different Scenarios

Owing to the complexity of the actual dairy farming environment and inclusion of various conditions, such as daytime, nighttime, rainy days, and partial occlusion, detecting a cow’s mouth area in the collected images are challenging.

Table 2 presents the detection results of YOLOv3, YOLOv4, YOLOv5, YOLOv7, and Biformer–YOLOv7 under the following scenarios: daytime, nighttime, rainy days, and partial occlusion. The figure indicates that except for Biformer–YOLOv7, all models experience missed detections. Green-circled areas in the table below highlight the missed detection regions. For YOLOv3, detection performance is better at nighttime and on rainy days but displays missed detections during daytime and in occlusion scenarios. YOLOv4 exhibits missed detections in all environments, demonstrating the worst performance. YOLOv5 performs satisfactorily during daytime and nighttime but fails to detect cows at side angles on rainy days and in occlusion scenarios. Compared with YOLOv3, YOLOv4, and YOLOv5, YOLOv7 exhibits better detection performance. However, the mouth area of the cow is obscured in the image, and the tracking box cannot accurately capture the mouth area of the cow, and sometimes cannot completely cover the mouth area of the cow. Compared with these four models, Biformer–YOLOv7 does not miss any detection in the four scenarios and displays the highest mAP value.

5.2. Results and Analysis of Rumination Behavior Recognition

5.2.1. Evaluation Metrics

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed cow rumination behavior recognition method proposed in this chapter, the following two metrics were used.

Chewing Count Misdetection Rate: The absolute value of the difference between the chewing count calculated by the model and via manual calculation, divided by the manually calculated chewing count.

where n

r represents the chewing count misdetection rate (%), m

r denotes the chewing count calculated by the model, and p

r is the manually calculated chewing count of a cow.

Relative Error of Rumination Duration: The absolute value of the difference between the chewing frame count calculated by the model and via manual calculation, divided by the manually calculated chewing frame count.

where n

t denotes the rumination frame count misdetection rate (%), m

t represents the chewing frame count calculated by the model, and p

t is the manually calculated chewing frame count.

5.2.2. Experimental Results

After detecting the mouth areas of cows, their chewing count and rumination duration were statistically estimated. The corresponding da are listed in

Table 3. Ten rumination videos of cows at different angles (the angle of the cow's head relative to the video capture device) were selected and numbered 0–9. The chewing and frame counts during the rumination process of cows were obtained through both model and manual calculations.

Table 3 presents details regarding cows ruminating at different angles. The following conclusions can be drawn from the table: when cows ruminate continuously at a lateral angle, errors in the chewing count and frame number calculated using the model are minimal. The false detection rate was the highest when cows turned their heads repeatedly during rumination, and the video number 6 had the worst monitoring effect. Overall, errors in the chewing count and frame number for cow rumination monitoring using the model are 3.09 and 4.2, respectively, which can be used in assessing the accuracy of cow rumination at different angles.

Figure 13(a)–(c) depict the rumination behavior of cows at different angles, encompassing the process of a cow chewing a bolus. The horizontal axis represents the video frame number, and the vertical axis denotes the change in the H value. The frames marked with red boxes on the curve show minimal changes in the H value, indicating that the height and width of the tracking box change slightly; this is ascribed to the swallowing stage during rumination. Purple boxes denote brief moments when the H value decreases, signifying a change in a cow’s rumination angle. In

Figure 13(a)–(c), a cow swallows a bolus for 78, 86, or 70s, respectively.

6. Conclusions

This study aims to address challenges in identifying the dairy cow rumination behavior, which includes interference from the external environment and a small and highly mobile mouth area. Through deep learning and video analysis techniques, the real-time detection and analysis of dairy cow rumination were performed, deriving the following conclusions: first, data collection was conducted in various complex environments (daytime, nighttime, rainy days, and partial occlusion scenarios) to ensure that the model could more accurately identify the cow’s rumination behavior in these scenarios. Second, to overcome the highly mobile nature of dairy cows, different angles of dairy cow rumination, including front and side views, were collected to ensure the accurate identification of the rumination behavior from various angles. Additionally, to address the problem that the mouth area of the cow is small in the monitoring screen, the improved YOLOv7 model is adopted, the Biformer attention module which is effective for small targets is added, and the standard convolution of the head part is replaced by GSConv, which improves the accuracy and reduces the model size. However, this study currently focuses on the identification and analysis of single-target dairy cows. Future research will prioritize the detection and identification of multitarget dairy cows to further improve and expand the application scope of the proposed model. Thus, this study provides an effective solution for the identification of the dairy cow rumination behavior and offers valuable insights for future in-depth research and practical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z.; methodology Y.Z. and Z.J.; software, Y.Z.; validation X.M. and Z.W.; formal analysis, Z.W.; investigation, Y.Z. and R.Y.; resources, Y.Z. and Z.J.; data curation, D.L. and J.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z. and Z.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded Supported by Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (Grant No. 202103021224149), Shanxi Province Postgraduate Excellent Teaching Case (No: 2024AL07), Shanxi Province Educational Science “14th Five Year Plan” Education Evaluation Special Project (No: PJ-21001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanxi Agricultural University.

Data Availability Statement

Data included in the text.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for providing helpful suggestions for improving the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang Y, Li X, Yang Z, et al. Recognition and statistical method of cows rumination and eating behaviors based on Tensorflow.js[J]. Information Processing in Agriculture,2024,11(4):581-589. [CrossRef]

- Shao D, F. Research on the change of rumination behavior of dairy cows and the correlation of influencing factors [D]. Jilin University,2015.

- Ren X H, Liu G, Zhang M, et al. Dairy Cattle's Behavior Recognition Method Based on Support Vector Machine Classification Model. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery, 2019, 50(S1): 290-296. [CrossRef]

- Zhang A, J. Rumination Recognition Method of Dairy Cows Based on the Noseband Pressure. Master Thesis, . Northeast agricultural university, Heilongjiang, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song H B, Li T, Jiang B, et al. Automatic detection of multi-target ruminate cow mouths based on Horn-Schunck optical flow algorithm. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering, 2018, 34(10): 163-171. [CrossRef]

- Ji J T, Liu Q H, Gao R H, et al. Ruminant Behavior Analysis Method of Dairy Cows with Improved Flow Net 2.0 Optical Flow Algorithm. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery, 2023, 54(01): 235-242.

- Mao Yanru, Niu Tong, Wang Peng, Song Huaibo, He Dongjian. Multi-target cow mouth tracking and rumination monitoring using Kalman filter and Hungarian algorithm[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering (Transactions of the CSAE), 2021, 37(19): 192-201. [CrossRef]

- Hu Z, Yang H, Lou T. Dual attention-guided feature pyramid network for instance segmentation of group pigs[J]. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 2021, 186: 106140. [CrossRef]

- Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, et al. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection, IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). USA, 2016: 779-788. [CrossRef]

- Redmon J, Farhadi A. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. arXiv:1804.02767, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Bochkovskiy A, Wang C Y, Liao H Y M. Yolov4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv:2004.10934, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wang T Y, Cong Y H, Wu H J, et al. UAV Target Tracking Algorithm Based on Kernel Correlation Filtering. Digital Technology &Application, 2022, 40(10): 77-81+108. [CrossRef]

- Yu L Y, Fan C X, Ming Y. Improved target tracking algorithm based on kernelized correlation filte. Journal of Computer Applications, 2015, 35(12): 3550-3554. [CrossRef]

- Gao Y, Chen B, Liao H M, et al. Recognition method for aggressive behavior of group pigs based on deep learning. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering, 2019, 35(23): 192-200. [CrossRef]

- Yan H W, Liu Z Y, Cui Q L, et al. Detection of facial gestures of group pigs based on improved Tiny-YOLO. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering, 2019, 35(18): 169-179. [CrossRef]

- HE D J, LIU J M, Xiong H T, et al. Individual Identification of Dairy Cows Based on Improved YOLO v3. Transactions of the Chinese Society for Agricultural Machinery, 2020, 51(04): 250-260. [CrossRef]

- Wang C Y, Bochkovskiy A, Liao H Y M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. arXiv e-prints, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y J, He D J, Fu Y X, et al. Intelligent monitoring method of cow ruminant behavior based on video analysis technology. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering, 2017, 10(5): 194-202. [CrossRef]

- Hou, S. Study on ruminant behavior identification of dairy cows based on activity data and neural network. Master Thesis, . Inner Mongolia University, Inner Mongolia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- JIANG Kailin, XIE Tianyu, YAN Rui, et al. An attention mechanism-improved YOLO v7 object detection algorithm for hemp duck count estimation. Agriculture, 2022, 12(10): 1659. [CrossRef]

- Psota E T, Mittek M, Pérez L C. Multi-pig part detection and association with a fully-convolutional network[J]. Sensors, 2019, 19(4): 852. [CrossRef]

- Nicolas C, Francisco M, Gabriel S, et al. End-toend object detection with transformers. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 2020, 12346: 213–229. [CrossRef]

- Hulin L, Jun L. Slim-neck by GSConv: A better design paradigm of detector architectures for autonomous vehicles. Nature Protocols,2019, 14(7): 2152-2176. [CrossRef]

- Liu H H, Fan Y M, He H Q, et al. Improved YOLOv7-tiny’s Object Detection Lightweight Model. Computer Engineering and Applications, 2023, 59(14): 166-175. [CrossRef]

- Yangxuen Ning, Wang Ao, Xujing Yi, et al. Population rule of rumination time and its influencing factors in lactating female cattle in Tibet [J]. Chinese Journal of Animal Science, 2019,60(04):105-110. [CrossRef]

- Wang N, Li X, Shang S, et al. Monitoring Dairy Cow Rumination Behavior Based on Upper and Lower Jaw Tracking[J]. Agriculture, 2024,14(11):2006-2006. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann G, Strutzke S, Fiske D, et al. A New Approach to Recording Rumination Behavior in Dairy Cows[J]. Sensors, 2024,24(17):5521-5521. [CrossRef]

- Song Huaibo, Niu Mantang, Ji Cunhui, Li Zhenyu, Zhu Qingmei. Monitoring of multi-target cow ruminant behavior based on video analysis technology[J]. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering (Transactions of the CSAE), 2018, 34(18): 211-218. [CrossRef]

- Bolya, Daniel, et al. Yolact: Real-time instance segmentation. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Liu Y, Zheng W, et al. Monitoring Cattle Ruminating Behavior Based on an Improved Keypoint Detection Model. [J].Animals : an open access journal from MDPI,2024,14(12):1791-1791. [CrossRef]

- Jia Z, Wang Z, Zhao C, et al. Pixel Self-Attention Guided Real-Time Instance Segmentation for Group Raised Pigs[J]. Animals, 2023,13(23), 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).