1. Introduction

Accurately detecting pain in dairy cattle is an unresolved yet critical goal in animal-welfare science. Pain erodes the animal’s quality of life and silently drains farm productivity through reduced milk yield, impaired immunity, and higher veterinary costs, creating an ethical and economic imperative to intervene early (Zoltick et al., 2024; Carbone et al., 2020). Evolution, however, has prepared cattle to mask distress. As prey animals they minimise conspicuous behaviours that might attract predators, so their overt pain signals are rare, fleeting, and low-amplitude. Conventional tools such as locomotion scoring, heart-rate telemetry, and vocal-sound counting often miss these subtle cues and demand invasive devices or continuous expert oversight, making them impractical for large herds and commercial barns (McLennan, 2018).

Over the past decade researchers have turned to facial expression analysis as a non-intrusive lens on mammalian nociception. In sheep, pigs, and horses, discrete facial action units (FAUs) correlate reproducibly with experimentally induced pain, suggesting that rapid cranio-facial reflexes can outsmart voluntary suppression (Mota-Rojas et al., 2025). The biological rationale is well established: nociceptive input propagates through cranial nerves V and VII, driving reflex contractions in periocular, perinasal, and perioral muscles that remain difficult to inhibit at will (Henssen et al., 2016; Gothard, 2014). Even species that dampen lameness or visceral discomfort cannot entirely hide these muscle activations, which arise milliseconds after noxious stimulation (Matsumoto and Willingham, 2009; Gleerup et al., 2015).

Bovine behaviourists have catalogued a repertoire of such markers. Ear-position asymmetry, orbital tightening, tension above the eye, nostril flare, and mouth-strain geometry all increase after painful procedures like dehorning or mastitis induction (Farghal et al., 2024; Tschoner et al., 2024). The Calf Grimace Scale (CGS) formalises six FAUs with high inter-observer agreement, giving practitioners a shared lexicon for pain scoring (Lu et al., 2017; Evangelista et al., 2021; McLennan et al., 2019). Yet these protocols remain fundamentally static. Each frame is paused, examined, and annotated by trained observers, throttling throughput, embedding subjective bias, and discarding the temporal dynamism that may distinguish short-lived discomfort from benign facial idiosyncrasy.

Artificial-intelligence studies have begun to automate facial analysis, but most still use coarse labels such as “pain” or “no pain” assigned to entire images or videos, ignoring the sub-second time structure that characterises acute distress (Rashid, 2021). This omission is crucial because the most diagnostic events are the involuntary micro-expressions—muscle twitches lasting between 1/25 s and 1/3 s—that psychologists and security agencies have long exploited to unveil concealed emotion (Zhang, 2024; Chen et al., 2025; Dong et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2017).

Human-factors engineering has already harnessed micro-expression analytics for driver-state monitoring. In advanced driver-assistance systems, lightweight convolutional-recurrent networks ingest live video, amplify tiny pixel motions through optical flow or Eulerian magnification, and flag drowsiness or aggression with frame-level precision (Bai and Goecke, 2020). Architectures such as MobileNetV2 or RM-Xception funnel spatial features into Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) heads, achieving millisecond responsiveness while running on edge devices (Yu et al., 2018). Recent work enhances sensitivity through time-series fusion and attention-weighted pooling, preserving accuracy across faces, lighting modes, and camera angles (Pu et al., 2025; Pennington et al., 2019).

Our hypothesis is that these temporal-expression architectures can be transplanted to cattle after anatomical calibration. Bovine facial musculature is simpler than human yet still offers enough contractile diversity in the eye, ear, and muzzle regions to betray nociceptive load through brief asymmetries and aperture changes (Cain, 2024). Early feasibility studies in livestock vision hint at this possibility, but they either rely on static landmarks or use frame-level models without explicit temporal reasoning (Shibanoki et al., 2024; Parivendan et al., 2025; Mahato and Neethirajan, 2024).

To scrutinize the hypothesis we designed an end-to-end temporal vision system tailored to barn conditions. A YOLOv8-Pose backbone isolates the face and places thirty anatomically coherent landmarks with real-time throughput and robust performance in oblique or overhead camera views. Region-of-interest patches from the eyes, ears, and muzzle feed a pretrained MobileNetV2 encoder that condenses each frame into a 3 840-dimensional descriptor sensitive to fine-grained gradients. A 128-unit LSTM stitches together five-frame sequences, learning motion trajectories that separate nociceptive twitches from benign facial jitter (Guo et al., 2025). At the video level, probability averaging and burst-density heuristics temper false alarms, borrowing confidence-weighting logic from driver-monitoring systems.

This investigation therefore bridges two previously siloed fields: livestock pain phenotyping and human micro-expression AI. It contributes three advances. First, it provides the first systematic evaluation of micro-expression dynamics as a pain biomarker in dairy cattle, bringing fine-timescale analysis into a domain dominated by static scoring. Second, it releases an open-source landmark dataset with species-specific annotations, creating a foundation for transfer learning across breeds and lighting environments. Third, it demonstrates a deployable low-latency pipeline aligned with the compute constraints of on-farm edge devices, moving pain detection from sporadic manual checks to continuous surveillance. By capturing the vanishingly brief facial echoes of nociception, the system aims to trigger earlier interventions, elevate welfare metrics, and improve both ethical resilience and economic efficiency in the dairy sector.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

The foundation of this research is a carefully curated, high-quality video dataset collected from over six commercial dairy farms across Atlantic Canada, supplemented by recordings from the Ruminant Animal Centre at Dalhousie University, Canada. The primary breed represented is Holstein, with a minority of Jersey cattle included to capture breed-related variability in facial morphology and expression. The dataset encompasses several hundred videos, each capturing the head and facial region of individual cows under naturalistic farm conditions.

2.1. Pain Labeling and Categorization

Pain labels were assigned based on rigorous veterinary assessments and observations by experienced farm workers. Painful states were identified through clinical diagnoses or known painful procedures such as lameness and mastitis treatment. Control videos were recorded from healthy cows under similar environmental and lighting conditions to ensure comparability. This binary classification—pain versus no-pain—forms the basis for supervised learning.

2.2. Video Acquisition and Processing

All videos were recorded at 30 frames per second (FPS) with standardized lighting to minimize variability due to illumination changes. The videos were resized to a consistent resolution to facilitate uniform processing. From each video, individual frames were extracted and organized sequentially, preserving temporal continuity essential for micro-expression analysis.

2.3. Dataset Composition and Diversity

The dataset comprises over 8,700 high-resolution images representing approximately 600 individual cows, including both Holstein and Jersey breeds. The images were collected in diverse natural farm environments—barns, pastures, and open yards—reflecting the environmental complexity and physiological variability inherent to commercial dairy operations in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. This contextual richness is critical for training models that generalize well across real-world conditions.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

All data collection procedures were reviewed and approved by the Dalhousie University Ethics Committee (Protocol 2024-026). Data acquisition was entirely non-invasive, involving passive image and video capture without any physical contact or intervention with the animals. Participating farm owners provided informed written consent after being fully briefed on the study’s objectives and protocols. This adherence to ethical standards ensures animal welfare was uncompromised throughout the research. The dataset’s scale, diversity, and ethical rigor provide a robust foundation for training and evaluating deep learning models aimed at subtle pain detection through facial micro-expression analysis in dairy cattle.

2.5. Landmark Extraction and Model Architecture

Precise localization of facial landmarks is critical for capturing the subtle muscular movements associated with pain expressions. To this end, we developed a customized landmark detection pipeline tailored specifically to bovine facial anatomy. We employed a pose estimation model based on YOLOv8-Pose, a state-of-the-art convolutional neural network architecture optimized for real-time keypoint detection with high accuracy and efficiency. The model was fine-tuned on a dedicated dataset annotated with 30 key facial landmarks per image. These landmarks were strategically selected to cover semantically significant regions implicated in pain expression, including the eyes, ears, muzzle, nostrils, and lower jaw.

2.6. Processing Pipeline

Each input video was decomposed into individual frames, which were then processed sequentially by the YOLOv8-Pose model. For each frame, the model outputs included a bounding box delineating the cow’s face and normalized 2D coordinates of the 30 facial landmarks. To ensure detection reliability, frames with confidence scores below 0.5 were discarded. In cases where multiple cows appeared in a frame, only the detection with the highest confidence score was retained to avoid ambiguity.

2.7. Normalization and Data Organization

To maintain scale invariance across videos of varying resolutions, all landmark coordinates were normalized by dividing their pixel values by the frame’s width and height. This normalization facilitates consistent geometric feature extraction regardless of image size or aspect ratio. The cropped facial images and corresponding landmark coordinates were systematically saved in an organized directory structure indexed by source video and frame number. Additionally, a CSV file was generated to associate each video with its binary pain label, enabling efficient batch processing and model training. This automated landmark extraction pipeline enables the high-resolution, geometrically informative representation of bovine facial features necessary for downstream deep learning models to detect pain-related micro-expressions in unconstrained video footage.

2.8. Feature Extraction and Temporal Modeling with LSTM

Recognizing pain-related micro-expressions requires capturing both spatial detail and temporal dynamics. We designed a two-stage feature extraction and temporal classification pipeline to address this challenge. Stage 1: Based on the 30 detected facial landmarks, three anatomically relevant regions were cropped from each frame: the eyes, ears, and mouth. These regions are known from ethological studies to exhibit characteristic changes during pain states. Each ROI was resized to a standardized input dimension of 96×96 pixels to maintain uniformity for convolutional processing. Stage 2: Each ROI was passed through a pretrained MobileNetV2 convolutional neural network, chosen for its lightweight architecture and strong feature extraction capabilities. MobileNetV2 employs depthwise separable convolutions and inverted residual blocks, which reduce computational complexity while preserving representational power. From each ROI, a 1,280-dimensional feature vector was extracted, resulting in a concatenated 3,840-dimensional feature vector per frame that encapsulates detailed local facial information.

2.9. Temporal Sequence Construction

To model the temporal evolution of facial expressions, frame-level feature vectors were grouped into fixed-length sequences using a sliding window approach. Each sequence consisted of five consecutive frames, a window size informed by the typical duration of micro-expressions (between 40 and 200 milliseconds). Each sequence inherited the binary pain label of its parent video, yielding a dataset of spatiotemporal samples for supervised learning.

2.10. LSTM Model Architecture

The temporal classification model was implemented using the Keras deep learning framework. It consists of a single Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) layer with 128 hidden units, designed to capture temporal dependencies and patterns in the sequential data. To prevent overfitting, a dropout layer with a rate of 0.5 was applied after the LSTM layer. The output was then passed through a fully connected dense layer with 64 ReLU-activated units, culminating in a sigmoid-activated neuron that outputs a binary classification probability indicating pain presence.

2.11. Training Procedure

The model was trained on ten video recordings: six labeled as pain and four as no-pain. The pain videos averaged 3,882.5 frames each, while the no-pain videos averaged 4,804 frames, resulting in a mild temporal imbalance that was carefully accounted for in evaluation metrics. Training was conducted over 30 epochs with a batch size of 32, using the Adam optimizer and binary cross-entropy loss. Early stopping based on validation loss was employed to optimize generalization. An 80/20 split was used for training and validation sets. The LSTM’s ability to model temporal dependencies allows the system to detect subtle, transient facial movements indicative of pain that static frame-based classifiers might miss. The combination of MobileNetV2 feature extraction and LSTM temporal modeling balances computational efficiency with the capacity to capture complex spatiotemporal patterns.

2.12. Inference Pipeline and Video-Level Classification

The inference pipeline was designed to enable real-time, frame-level pain detection and robust video-level classification. For each incoming video frame, the YOLOv8-Pose model detects the cow’s face and extracts 30 facial landmarks. Using these landmarks, the three predefined ROIs—eyes, ears, and mouth—are cropped and resized to 96×96 pixels. Each ROI is processed through the pretrained MobileNetV2 to extract feature vectors, which are concatenated into a single descriptor representing the frame. A sliding window buffer stores the five most recent frame descriptors. Once filled, the concatenated sequence is passed to the trained LSTM model, which outputs a probability score indicating the likelihood of pain. A threshold of 0.5 is applied to classify the sequence as "PAIN" or "NO PAIN." The predicted label is overlaid on the video frame, along with a color-coded bounding box around the detected face, providing an intuitive visual indicator.

To produce a robust video-level pain classification, frame-level predictions are aggregated over the entire video duration. A video is classified as exhibiting pain if more than 30% of its frames are labeled "PAIN." This empirically derived threshold balances sensitivity and specificity, reducing false positives while maintaining detection accuracy. Final predictions, including the pain frame ratio and raw classification scores, are saved to structured CSV files for quantitative evaluation. The pipeline supports both offline batch processing and real-time webcam input, facilitating deployment in research settings and commercial farm environments.

3. Results

Here we present a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed automated pain detection pipeline, encompassing detailed quantitative and qualitative analyses. We systematically examine the performance of each pipeline component, from face and landmark detection to temporal sequence classification and video-level inference, and provide critical insights into the system’s strengths, limitations, and real-world applicability.

3.1. Face and Landmark Detection Performance

3.1.1. Model Training and Evaluation

To enable precise localization of facial regions and extraction of keypoints from dairy cow videos, a customized YOLOv8-Pose model was trained on a dataset comprising 1,997 manually annotated cow face images. Each annotation included a bounding box for the face and 30 anatomically relevant facial landmarks. The model’s performance was rigorously evaluated using standard object detection and pose estimation metrics.

3.1.2. Bounding Box Detection

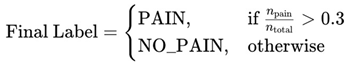

The YOLOv8-Pose model demonstrated exceptional localization capabilities. At a confidence threshold of 0.969, the model achieved a bounding box precision of 1.00, indicating no false positives at this threshold. Recall was 0.96 at a threshold of 0.0, reflecting the model’s ability to detect nearly all true cow faces across the dataset. The F1-score, which balances precision and recall, peaked at 0.95 around a confidence value of 0.505, suggesting robust performance across varying thresholds. These results are visualized in

Figure 1, which displays the precision, recall, and F1-score curves as functions of the model’s confidence output.

3.1.3. Pose Estimation and Landmark Localization

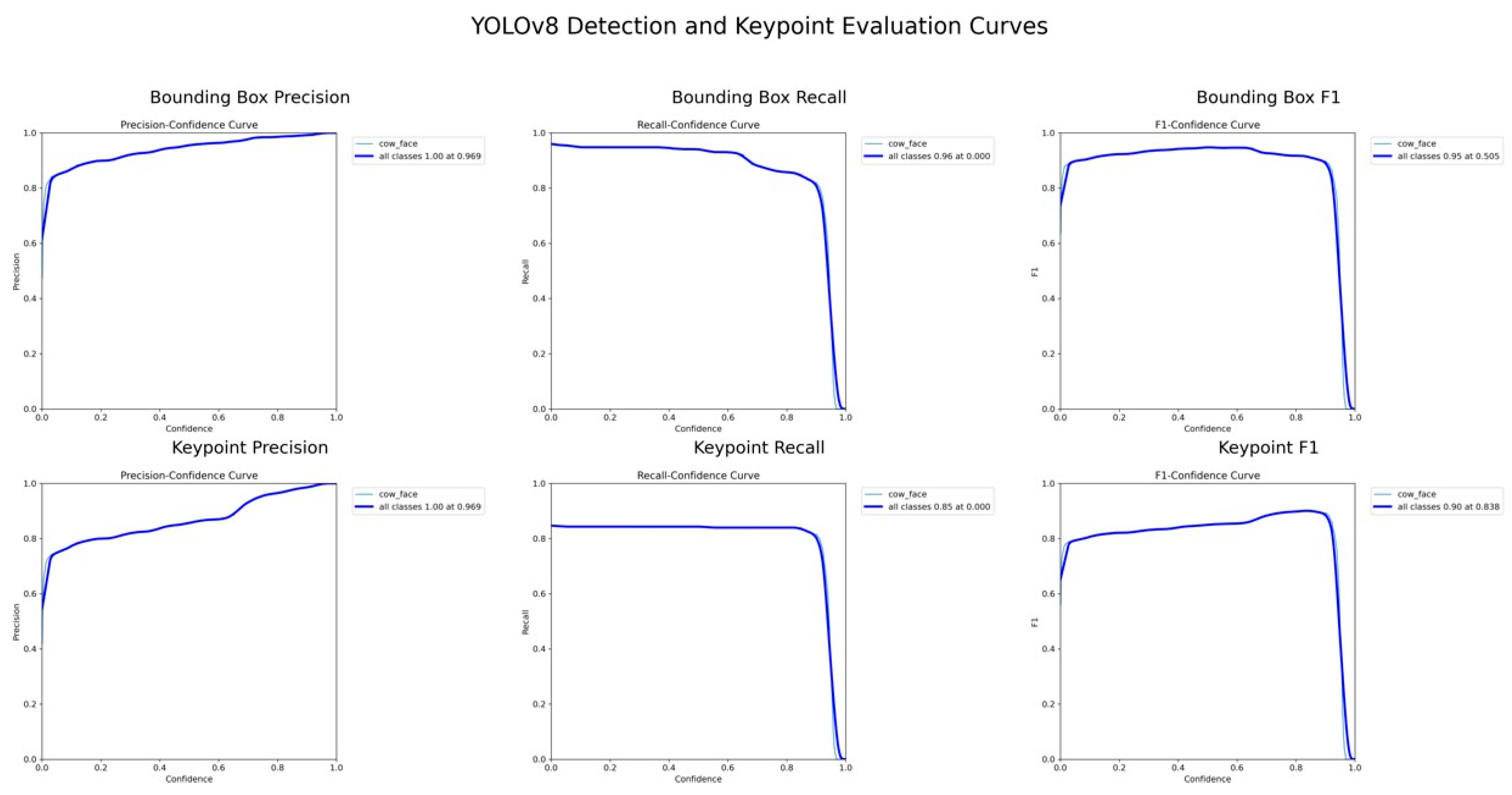

For pose estimation, the model’s precision and recall both exceeded 0.85 across a wide range of confidence values, with a maximum F1-score of 0.90 at a confidence threshold of 0.838. This indicates reliable and consistent detection of facial landmarks, even under challenging real-world conditions such as variable lighting, occlusions, and diverse cow postures. The mean Average Precision (mAP) at Intersection over Union (IoU) 0.50 (AP50) reached 0.969 for bounding boxes and 0.838 for keypoints. The more stringent mAP@0.50–0.95 scored 0.899 for detection and 0.590 for keypoints (see

Figure 2). These metrics confirm the model’s capability to not only detect cow faces with high accuracy but also to precisely localize facial landmarks critical for downstream pain recognition tasks.

3.1.4. Implications for Downstream Processing

This robust detection and localization performance provided high-quality input for subsequent stages of the pipeline. The YOLOv8-Pose model was deployed as the backbone of the frame-level preprocessing stage, reliably detecting cow faces and extracting 30 facial keypoints per frame. These keypoints were then used to define regions of interest (eyes, ears, and mouth) for feature extraction and temporal sequence modeling, forming the foundation for micro-expression-based pain analysis.

3.2. LSTM Model Training and Classification Performance

3.2.1. Convergence and Learning Dynamics

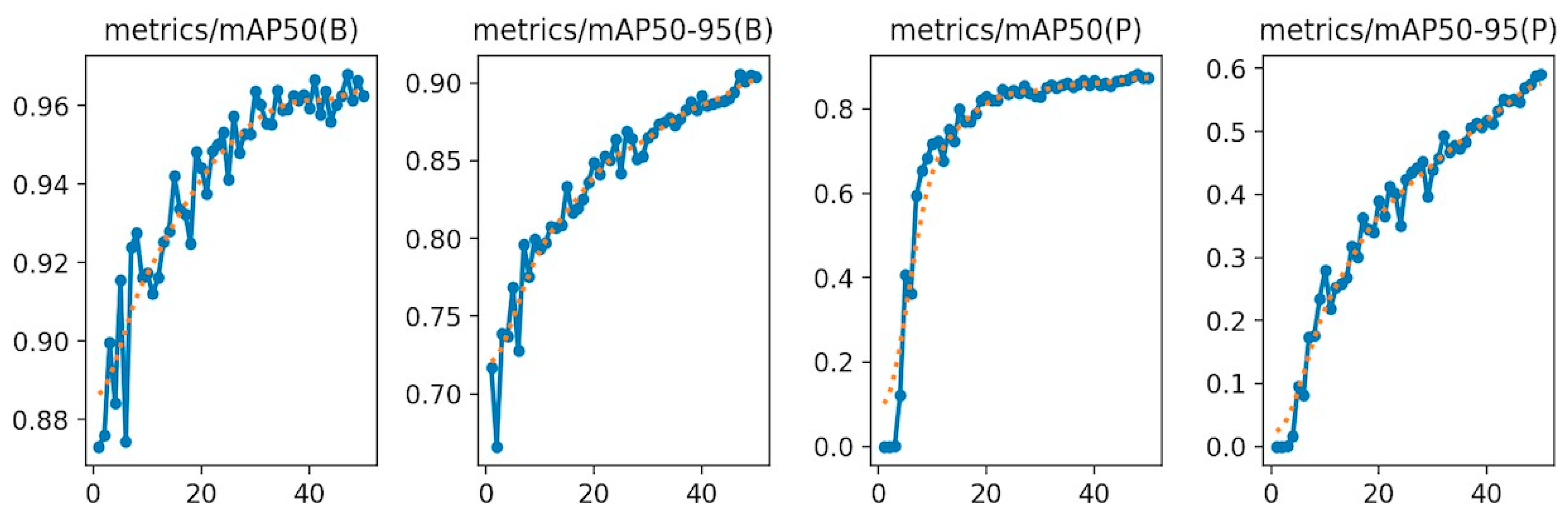

The Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model was trained to classify pain versus no-pain sequences based on extracted facial features. Training and validation accuracy curves (

Figure 3) reveal rapid convergence: validation accuracy surpassed 98% by epoch 5 and steadily approached 99.5% by epoch 30. The close alignment between training and validation curves indicates minimal overfitting, even with a relatively limited dataset. This suggests that the LSTM model effectively learned to recognize temporal patterns in pain-related facial behavior while maintaining strong generalization.

3.2.2. Quantitative Evaluation on Validation Data

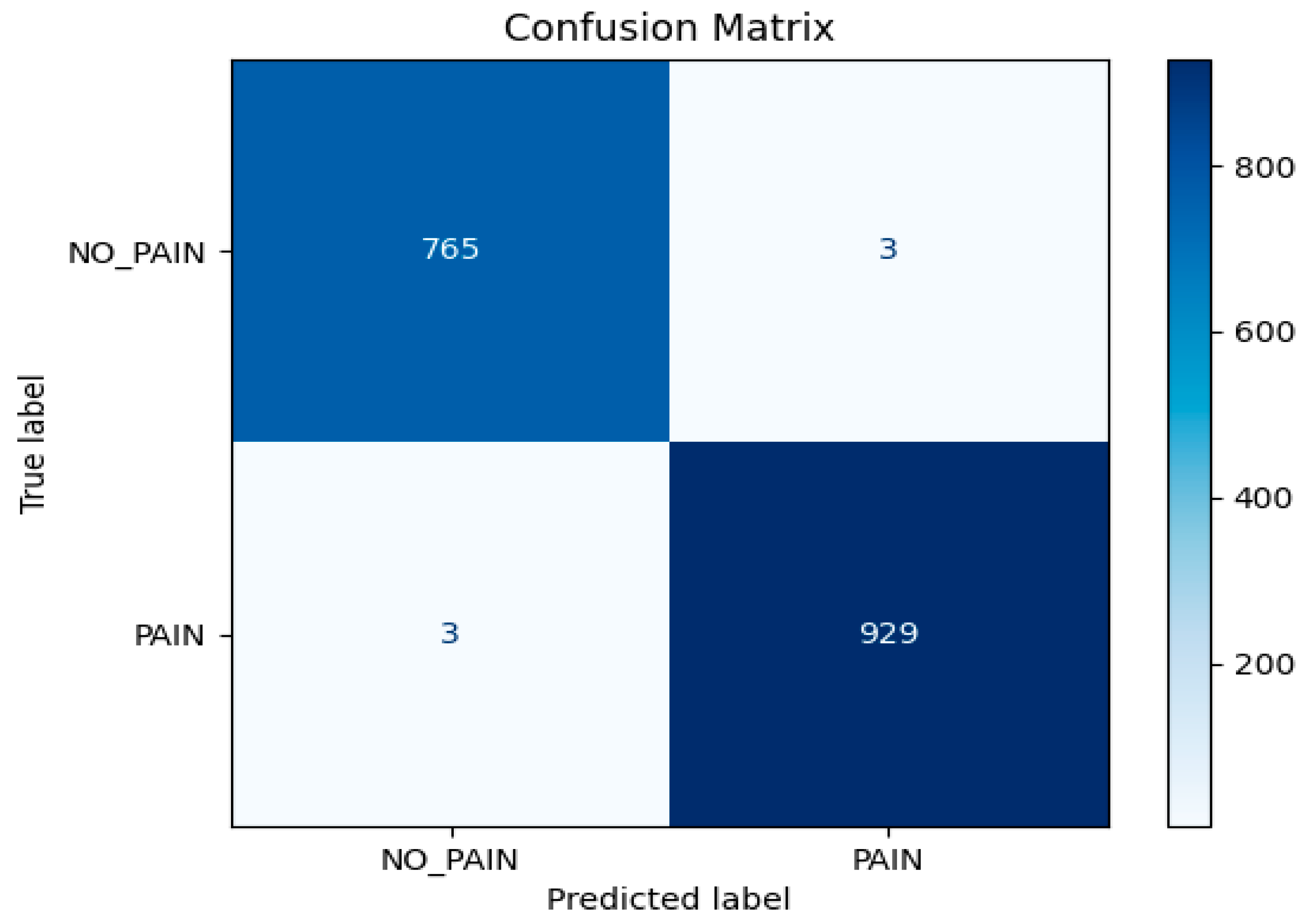

The model’s performance was further quantified using a confusion matrix (

Figure 4), which showed:

True Negatives (TN): 765

True Positives (TP): 929

False Positives (FP): 3

False Negatives (FN): 3

From these, standard classification metrics were calculated:

Accuracy: 0.9965

Precision: 0.9968

Recall: 0.9968

F1-score: 0.9968

These metrics demonstrate that the LSTM model achieved near-perfect performance on the validation set. The high precision and recall indicate that the model was both highly sensitive to pain sequences and highly specific in avoiding false alarms. The F1-score, harmonizing precision and recall, further confirms balanced and robust classification.

3.2.3. Interpretation and Limitations

It is crucial to note that these metrics were computed on a validation set derived from the same distribution as the training data, using an 80/20 stratified split. While these results confirm the model’s learning capacity and temporal pattern recognition, they do not fully guarantee generalizability to novel, real-world scenarios. Therefore, further evaluation on completely unseen videos was conducted to assess the model’s robustness in practice.

3.3. Qualitative Visualization of Frame-Level Inference

3.3.1. Pain and No-Pain Frame Analysis

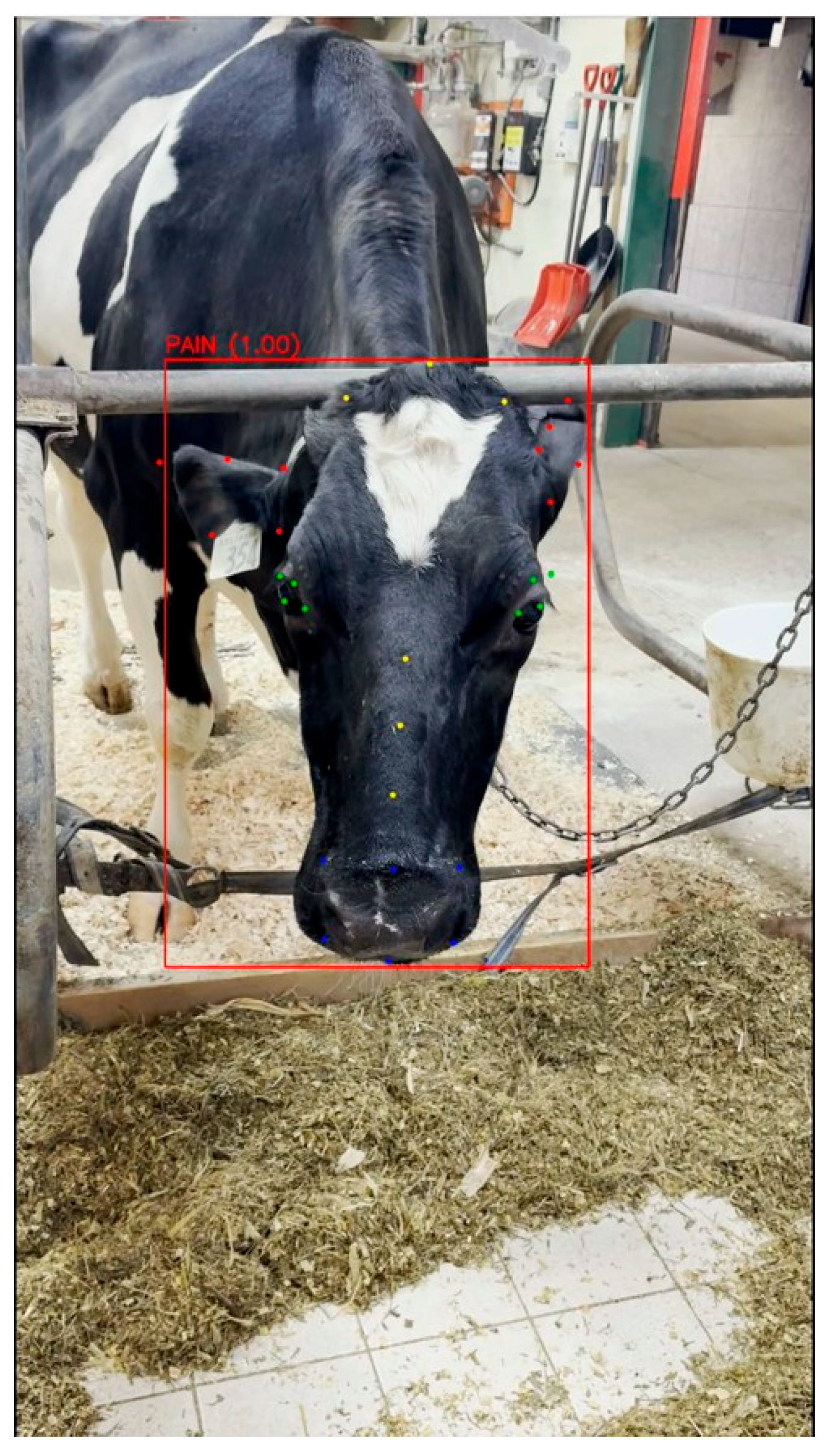

To elucidate the model’s decision-making process, individual frames from both pain and no-pain videos were visualized, annotated with predicted labels and confidence scores. In a correctly classified pain frame (

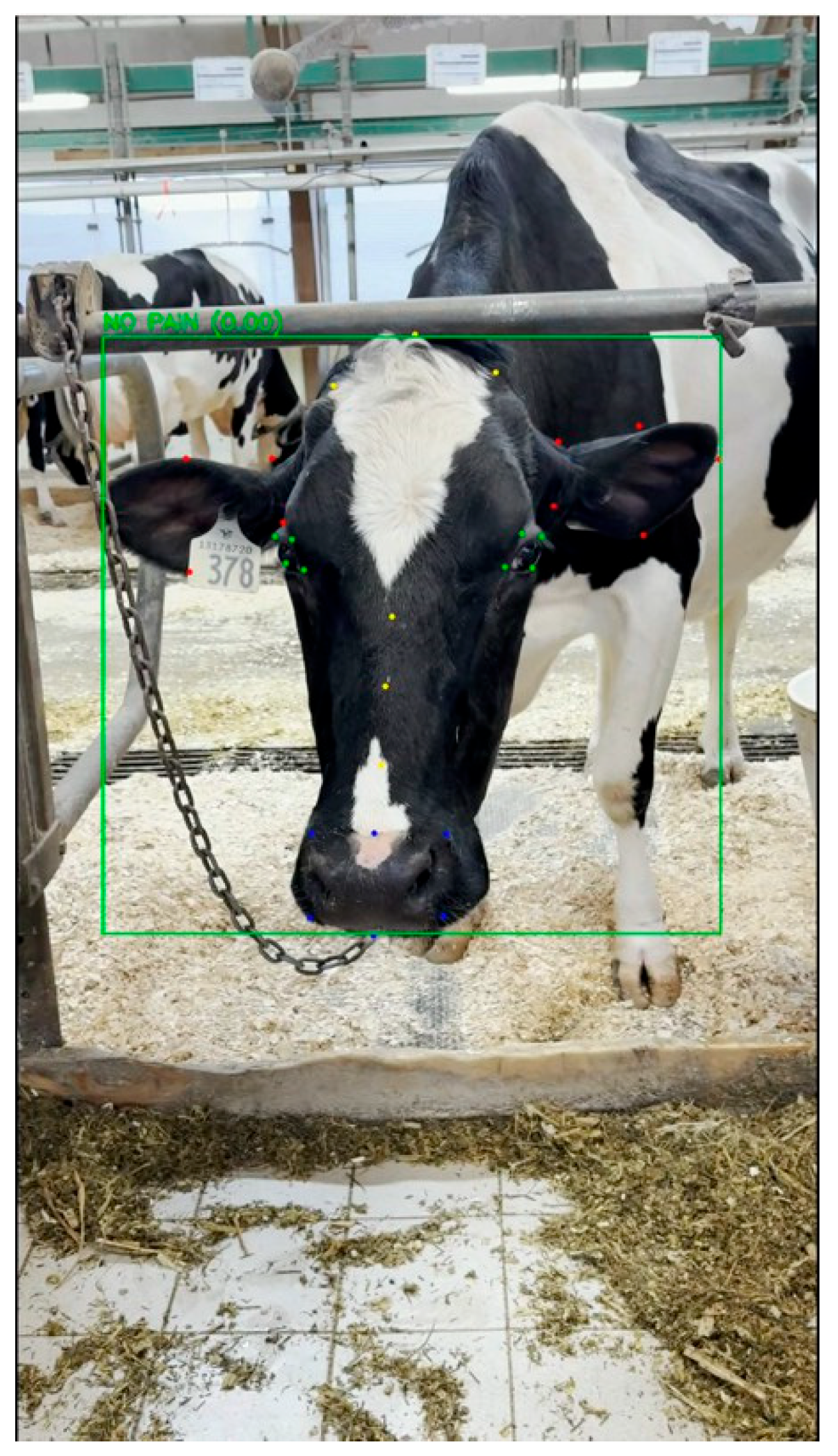

Figure 5), the model assigned a pain probability of 1.00, with a red bounding box highlighting the detected face. Overlaid landmarks, color-coded by anatomical region, revealed pronounced facial tension and changes around the eyes and muzzle—features consistent with pain expression. Conversely, a correctly classified no-pain frame (

Figure 6) displayed a pain probability of 0.00, with a green bounding box and evenly distributed landmarks indicative of a relaxed facial state. These visualizations underscore the model’s ability to distinguish subtle behavioral cues associated with pain, even in the presence of background clutter, occlusions, or variable lighting.

3.3.2. Robustness to Environmental Variability

The model’s consistent keypoint localization across diverse frames contributed to the robustness of downstream LSTM-based sequence modeling. Importantly, the system maintained high accuracy despite common farm environment challenges, such as feeding bars, equipment, and fluctuating illumination. This resilience is critical for real-world deployment, where controlled laboratory conditions cannot be assumed.

3.3. Inference Performance on Unseen Videos

To evaluate the generalizability of the trained model beyond the validation set, we conducted inference on a collection of 14 previously unseen videos. These videos were recorded under similar farm conditions but were not used during model training or hyperparameter tuning. The inference pipeline was applied in full, including frame- wise landmark detection, region-based feature extraction, sequential buffering, and classification via the pretrained LSTM model. For each video, the model predicted a binary pain/no-pain label for each sequence of five consecutive frames, and the overall video-level decision was determined by aggregating these predictions.

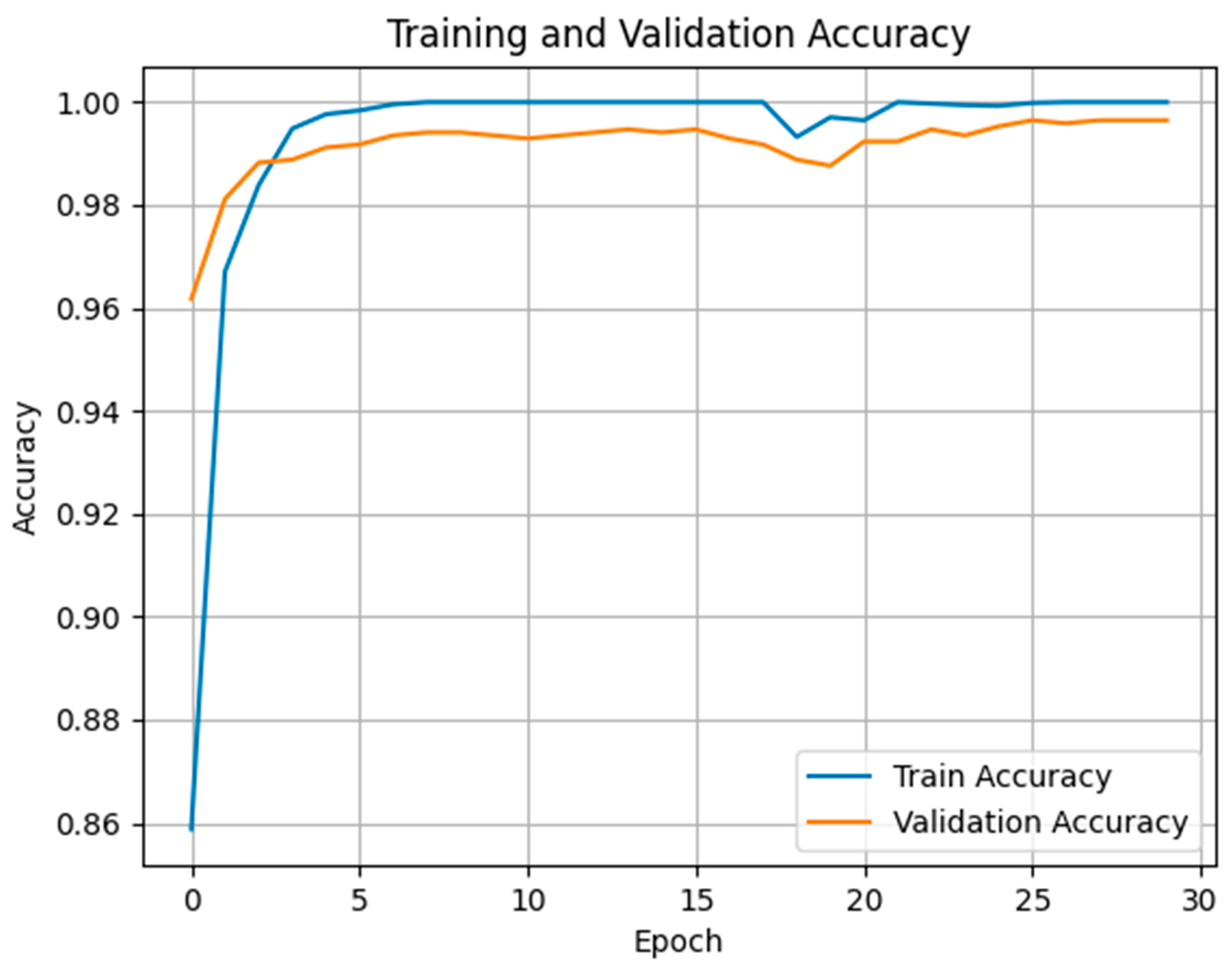

Specifically, a video was classified as pain if the proportion of its frame sequences labeled as pain exceeded a fixed threshold of 30%. This rule can be expressed as:

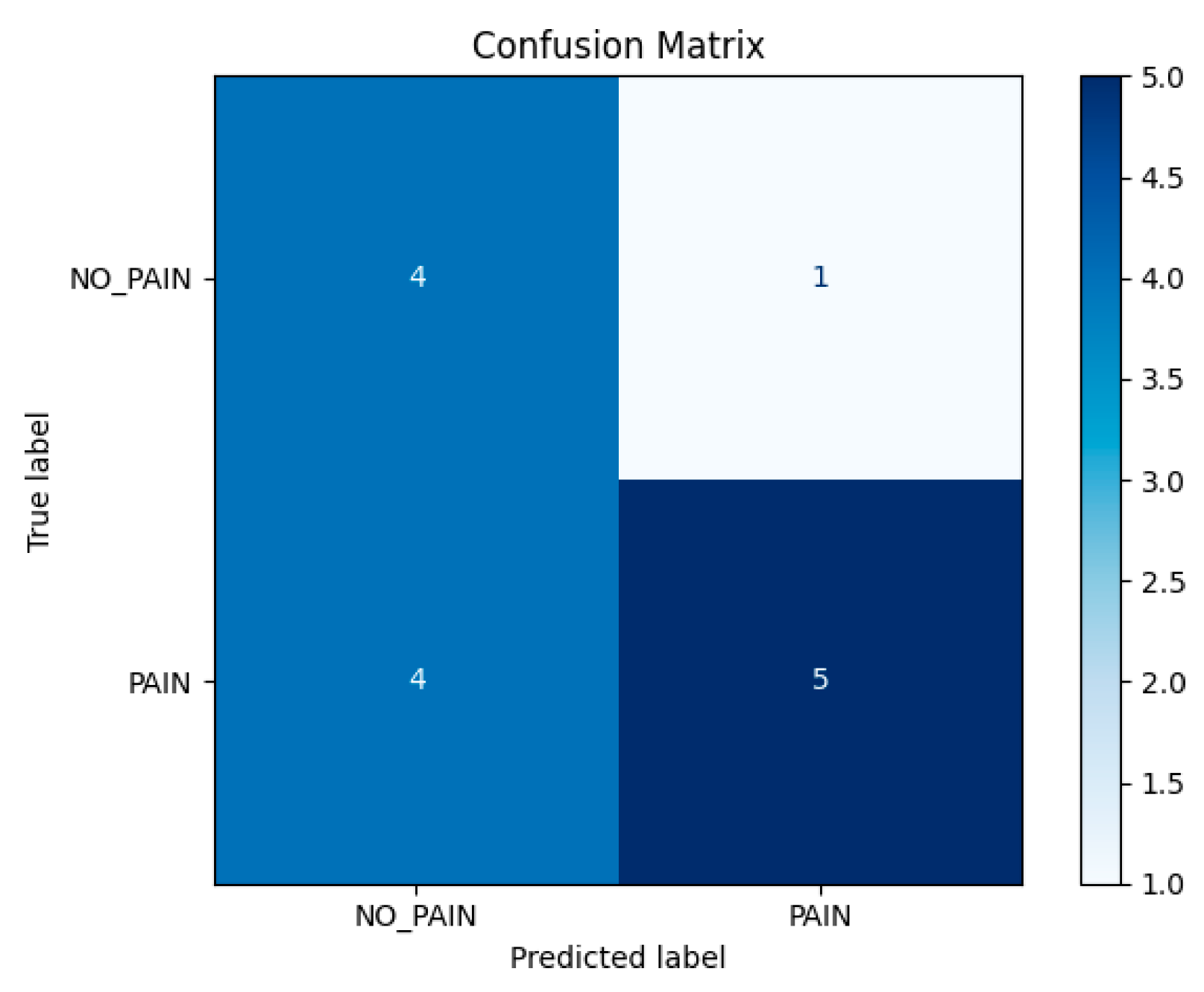

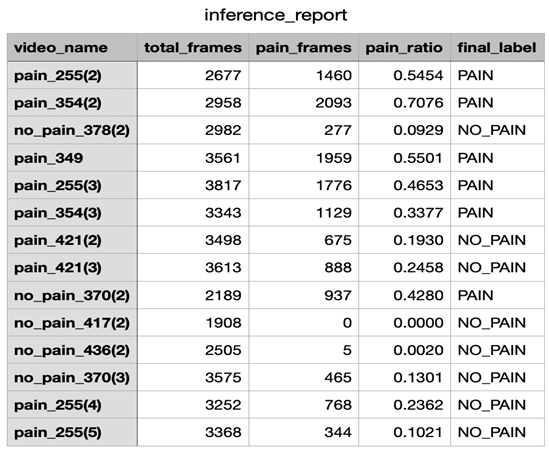

The detailed inference results are shown in

Table 1, which includes per-video statistics such as the total number of analyzed frames, the number of frames predicted as pain, the computed pain ratio, and the final label. Of the 14 test videos, 9 were annotated as pain and 5 as no-pain based on expert assessment. The resulting confusion matrix is shown in Figure 8, while standard classification metrics are summarized in

Figure 7. The model correctly predicted 5 out of 9 pain videos and 4 out of 5 no-pain videos, yielding an overall accuracy of 64.3% at the video level.

Quantitatively, the model achieved a precision of 0.83 for the pain class, indicating that when the model predicts pain, it is often correct. However, the recall was lower at 0.56, suggesting that the model failed to detect a significant fraction of actual pain cases. The F1-score for the pain class was 0.67, while the no-pain class had an F1-score of 0.62. The macro-averaged precision and recall were 0.67 and 0.68 respectively, and the overall weighted F1-score across both classes was 0.65. These values reflect moderate performance in a more challenging, real-world setting.

A closer look at the misclassified pain videos reveals important insights. For instance, pain_421(3) and pain_255(4) were incorrectly classified as no-pain, despite being ground-truth pain samples. However, their predicted pain ratios were 24.6% and 23.6% respectively—hovering just above and below the decision threshold. Pain_255(5), with a pain ratio of only 10.2%, was also misclassified. These examples suggest that certain pain expressions were either too brief or too subtle to influence the overall sequence- level predictions sufficiently. The use of a rigid 30% threshold may therefore be too coarse, potentially ignoring pain patterns that are temporally sparse but clinically significant.

To address the challenge of balancing sensitivity and specificity in video-level pain classification, future iterations of the system could move beyond fixed-threshold rules toward more context-aware decision mechanisms. For example, rather than applying a static average pain score cutoff, adaptive thresholds could be introduced based on intra- video distributional features, such as variance, local burst density, or score skewness. In addition, integrating high-confidence frame clusters as evidence—when they are sufficiently dense, temporally coherent, or strongly predicted—could provide a more nuanced signal than relying on global averages alone. Conversely, to reduce false positives in long no-pain videos with sporadic high scores, mechanisms such as burst- to-frame ratio gating or temporal consistency checks could help filter spurious activations. Finally, incorporating learned meta-classifiers or video-level neural decision heads that consume frame-wise predictions as input may allow the system to learn more subtle and context-dependent pain patterns than rule-based heuristics can capture.

It is also important to consider the impact of domain shift between the training and test videos. While the environment and camera setup were kept similar, individual differences in cow appearance (e.g., fur color, ear position, facial asymmetry) as well as lighting variation and partial occlusion (e.g., feeding bars) may have affected keypoint detection and, subsequently, downstream feature extraction. Such variability can cause slight misalignments in landmark localization, especially for sensitive regions like the eyes and mouth, ultimately affecting classification accuracy.

Despite these limitations, the model’s ability to correctly classify the majority of test videos—including several with high confidence—demonstrates the effectiveness of our pipeline under non-ideal conditions. These results also underscore the need for more diverse training data, robust data augmentation, and possibly ensemble decision strategies when deploying the system in production environments.

Table 2.

Video-level classification report (precision, recall, F1-score for both classes; accuracy, macro avg, weighted avg for all classes).

Table 2.

Video-level classification report (precision, recall, F1-score for both classes; accuracy, macro avg, weighted avg for all classes).

| Classification Metrics: |

| |

precision |

recall |

f1-score |

support |

| NO_PAIN |

0.50 |

0.80 |

0.62 |

5 |

| PAIN |

0.83 |

0.56 |

0.67 |

9 |

| accuracy |

|

|

0.64 |

14 |

| macro avg |

0.67 |

0.68 |

0.64 |

14 |

| weighted avg |

0.71 |

0.64 |

0.65 |

14 |

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates that automated detection of pain in dairy cattle using facial micro-expression analysis is not only feasible but also highly promising, as evidenced by the strong sequence-level validation accuracy of our LSTM-based system. However, the translation of this high accuracy to robust, real-world video-level performance remains a significant challenge. The observed drop from nearly perfect sequence-level results to a more moderate 64.3% video-level accuracy on unseen data underscores several fundamental issues that must be addressed for practical deployment and clinical utility.

One of the most prominent challenges lies in the temporal sparsity and variability of pain expression in cattle. As prey animals, cows have evolved to minimize overt displays of pain, making such expressions brief, subtle, and often context-dependent (Gleerup et al., 2015). Our findings, such as the misclassification of pain-labeled videos like pain_255(4) that contained only a minority of pain frames, highlight the inadequacy of fixed-threshold aggregation rules. Rigid thresholds—such as labeling a video as “pain” if more than 30% of its frames are classified as pain—fail to accommodate the diversity of pain expression patterns across individuals and contexts. Some cows may exhibit pain as short, intense bursts, while others display more diffuse or intermittent cues. This diversity is further complicated by environmental influences, such as feeding or resting periods, and by individual differences in pain tolerance and behavioral strategies.

The limitations of rule-based aggregation are compounded by the impact of domain shift and environmental variation. Our system’s performance was affected by factors such as individual cow appearance (including coat color, ear position, and facial asymmetry), lighting conditions, and partial occlusions from farm infrastructure like feeding bars. Even minor misalignments in landmark localization, particularly for sensitive regions such as the eyes and mouth, can propagate through the feature extraction and temporal modeling pipeline, ultimately degrading classification accuracy. These findings emphasize the necessity of more diverse and representative training data, as well as robust data augmentation strategies that simulate real-world variability. The use of advanced augmentation techniques, such as synthetic occlusion, random cropping, and brightness variation, could help the model generalize more effectively to the heterogeneous conditions encountered in commercial dairy environments.

Comparative analysis with existing literature further contextualizes the strengths and limitations of our approach. Previous studies in automated cattle pain and lameness detection have often relied on gross locomotor changes, utilizing 3D CNNs or ConvLSTM2D architectures to achieve video-level accuracies in the range of 85–90% (Zhang et al., 2021). However, these approaches are typically limited to overt, late-stage pathologies and require the animal to be walking or moving in a controlled manner. In contrast, our focus on facial micro-expressions enables continuous monitoring and has the potential to detect pain at earlier and less severe stages. Nevertheless, the moderate video-level accuracy observed in our study reflects the inherent difficulty of the task and the impact of environmental and subject variability, which are less pronounced in controlled locomotion-based studies.

The relevance of our approach to the ongoing development of grimace scales in animal welfare research is also noteworthy. Manual grimace scales, such as the Calf Grimace Scale (CGS), have become widely used for pain assessment across species, including rodents, equines, and bovines (Hänninen et al., 2008). These scales rely on the manual annotation of static facial features, such as orbital tightening, ear position, and nostril dilation. While effective in controlled settings, manual scoring is labor-intensive, subject to observer bias, and limited in temporal resolution. Automated systems like ours offer the potential for scalable, objective, and continuous pain assessment, but must overcome the challenges of subtlety, temporal sparsity, and environmental complexity. Our system’s ability to capture and classify brief, transient pain-related facial movements represents a significant advance, yet the moderate recall on unseen videos suggests that certain pain expressions—especially those that are brief, subtle, or confounded by environmental noise—remain difficult to detect reliably. This observation aligns with recent studies indicating that even trained human observers can struggle to consistently assess facial expressions and ear positions, particularly when micro-expressions are fleeting or ambiguous (Porter & ten Brinke, 2008).

Addressing these limitations requires a shift from rigid, rule-based decision mechanisms to more adaptive, context-aware strategies. Future iterations of our system should move beyond fixed-threshold rules toward decision mechanisms that are informed by intra-video distributional features, such as variance, local burst density, and score skewness. Adaptive thresholds could provide a more nuanced signal than global averages, while the incorporation of high-confidence frame clusters—when sufficiently dense, temporally coherent, or strongly predicted—could enhance detection sensitivity. Conversely, burst-to-frame ratio gating or temporal consistency checks could filter out sporadic false positives that may arise in long no-pain videos. Ultimately, integrating learned meta-classifiers or video-level neural decision heads that consume frame-wise predictions may allow the system to recognize subtle, context-dependent pain patterns that rule-based heuristics cannot capture.

From a methodological perspective, the adoption of advanced temporal modeling architectures, such as attention-based transformers, holds promise for improving the system’s ability to capture sparse and discontinuous pain events. Unlike traditional LSTM models, transformers can assign variable attention weights to different frames, highlighting those that are most informative for pain detection. This capability is particularly relevant for micro-expression analysis, where the most critical signals may be temporally isolated and easily overlooked by models that rely on fixed-length sequences or uniform weighting. In addition, multi-scale feature extraction and ensemble approaches could help capture a broader range of facial expression dynamics, further enhancing system robustness.

Expanding and diversifying the training dataset is another critical priority. Including a wider variety of cow breeds, ages, and pain contexts—such as metabolic pain, parturition, and breed-specific facial patterns—would help mitigate the risk of overfitting and improve generalizability. The use of self-supervised pretraining on large volumes of unlabeled video data, as well as generative augmentation techniques to synthesize rare pain expressions, could further enhance the model’s capacity to recognize diverse and subtle pain indicators (Caron et al., 2021).

Interpretability remains a key concern for the adoption of automated pain detection systems in practice. While our use of keypoint-based micro-expression detection provides some transparency at the frame level, the temporal decision boundaries produced by the LSTM are less interpretable. The development of visual explanation tools, such as Grad-CAM, could help elucidate which facial regions and time intervals are most influential in the model’s decisions. Such tools would not only improve system trustworthiness for veterinarians and animal welfare inspectors but also facilitate the identification of potential failure modes and biases.

The integration of facial micro-expression analysis with other non-invasive sensing modalities represents a promising direction for future research. Combining facial analysis with posture, gait, and physiological signals could provide a more holistic assessment of pain and welfare in dairy cattle. Multimodal fusion approaches may help disambiguate ambiguous cases, improve sensitivity and specificity, and enable the detection of pain states that are not readily apparent from facial cues alone.

The clinical and economic implications of automated pain detection are substantial. Early detection of pain can prevent production losses, reduce treatment costs, and improve overall herd health. For example, timely intervention in mastitis cases can reduce antibiotic usage and associated costs, while early detection of lameness can prevent declines in milk yield and reproductive performance (Rollin, 2018). Ethically, the deployment of such systems aligns with the growing emphasis on animal welfare and precision livestock farming, supporting the goal of individualized, real-time monitoring and proactive care.

Our study establishes micro-expression analysis as a viable paradigm for automated pain detection in dairy cattle, while also highlighting the complexities and challenges inherent in translating this technology to real-world farm environments. Achieving reliable, real-time pain monitoring at scale will require ongoing innovation in data collection, model architecture, interpretability, and multimodal integration. Future systems must embrace biologically informed temporal modeling, continual domain adaptation, and sensor fusion to fully realize the potential of precision welfare ecosystems. By addressing these challenges, automated pain detection systems can transform animal welfare from reactive intervention to proactive, individualized care, fulfilling both scientific and ethical imperatives in modern agriculture.

5. Conclusions

This research marks a significant step forward in the field of animal welfare technology by demonstrating that facial micro-expressions in dairy cattle can serve as reliable, quantifiable indicators of pain. By adapting advanced computer vision and temporal modeling techniques, originally developed for human micro-expression analysis, to the unique morphology and behavioral context of cows, we have shown that pain—a deeply subjective and often concealed experience—can be objectively inferred from subtle, fleeting facial movements. The system we developed, integrating a custom-trained YOLOv8-Pose model for precise facial landmark detection with a MobileNetV2 and LSTM-based temporal classifier, achieved remarkable sequence-level accuracy. This not only validates the technical feasibility of such an approach but also challenges the traditional boundaries of animal pain assessment, which have long relied on coarse behavioral scoring or invasive physiological monitoring.

Our findings suggest that pain in cattle is not merely observable to the trained human eye but is also computationally accessible, even when the animal’s evolutionary instincts drive it to suppress outward signs of discomfort. The ability to detect pain through short sequences of facial micro-expressions—movements lasting only fractions of a second—opens new possibilities for real-time, non-intrusive welfare monitoring. This capability is particularly transformative in large-scale farming environments, where individual animal observation is often impractical and early intervention can make a profound difference in health outcomes and quality of life.

The implications of this work extend far beyond technical achievement. By providing a scalable, automated means to monitor pain, our system lays the groundwork for individualized welfare baselines, where each cow’s unique pain signature can inform tailored care strategies. In the future, such technology could enable precision interventions, such as the automated administration of analgesics when specific pain patterns are detected, or the creation of auditable welfare records that support ethical supply chains and consumer transparency. These advances hold the promise of not only improving animal health and productivity but also addressing the growing societal demand for humane and responsible livestock management.

However, the deployment of such systems also raises important ethical and practical questions. The potential for false negatives—instances where pain is present but not detected—reminds us that even the most sophisticated algorithms must be continually refined and validated to minimize suffering. Equally, the challenge of interpretability remains: stakeholders, from farmers to veterinarians, require clear explanations of system decisions, including which facial features or micro-expressions triggered a pain alert. As we move toward greater automation in animal care, it is essential to balance technological innovation with transparency and trust.

Looking ahead, the framework established in this research opens several intriguing avenues. The methods developed here could be adapted to other species and emotional states, potentially enabling the detection of stress, anxiety, or positive welfare indicators in a variety of animals. Integrating facial micro-expression analysis with other sensing modalities—such as vocalization analysis, thermal imaging, or posture tracking—could provide a more holistic and nuanced understanding of animal well-being. The creation of digital twins or virtual herds, where welfare interventions can be simulated and optimized before real-world application, represents another exciting frontier.

Ultimately, this work highlights the profound potential of artificial intelligence to enhance our understanding and stewardship of animals. By giving voice to the silent signals of pain, we not only advance the science of animal welfare but also reaffirm our ethical commitment to those in our care. The fleeting tension of a muscle, the brief narrowing of an eye, or the subtle twitch of an ear—these micro-movements, once invisible and unmeasurable, now become the foundation for a new era of compassionate, data-driven animal husbandry. As we refine and expand these technologies, we must do so with humility and imagination, always guided by the principle that to care for animals is to listen deeply, measure wisely, and act with empathy. In this convergence of technology and compassion lies the promise of a future where animal suffering is not only seen but prevented, and where our relationship with the creatures who share our world is marked by understanding, respect, and care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Dairy Farmers of New Brunswick, Canada, for access to over 6 farms for data collection and for consultation and advice on the on-farm daily operations of dairy farming.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bai, M. and Goecke, R., 2020, October. Investigating LSTM for micro-expression recognition. In Companion Publication of the 2020 International Conference on Multimodal Interaction (pp. 7-11).

- Cain, B., 2024. Facial expressions in cattle in different affective states. https://stud.epsilon.slu.se/20429/1/cain_b_240218.pdf.

- Carbone, L., 2020. Do “Prey Species” hide their pain? Implications for ethical care and use of laboratory animals. Journal of Applied Animal Ethics Research, 2(2), pp.216-236. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Zhao, X., Xiong, Z. and Liu, G., 2025. EEG-Based Micro-Expression Recognition: Flexible Brain Network Reconfiguration Supporting Micro-Expressions Under Positive Emotion. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, pp.781-796. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z., Wang, G., Lu, S., Li, J., Yan, W. and Wang, S.J., 2022. Spontaneous facial expressions and micro-expressions coding: from brain to face. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, p.784834. [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, M.C., Monteiro, B.P. and Steagall, P.V., 2022. Measurement properties of grimace scales for pain assessment in nonhuman mammals: a systematic review. Pain, 163(6), pp.e697-e714. [CrossRef]

- Farghal, M., Pajor, E., Luna, S.P., Pang, D., Windeyer, M.C. and Ceballos, M.C., 2024. Development of the calf grimace scale for pain and stress assessment in castrated Angus beef calves. Scientific Reports, 14(1), p.25620. [CrossRef]

- Gleerup, K.B., Andersen, P.H., Munksgaard, L. and Forkman, B., 2015. Pain evaluation in dairy cattle. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 171, pp.25-32.

- Gothard, K.M., 2014. The amygdalo-motor pathways and the control of facial expressions. Frontiers in neuroscience, 8, p.43. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q., Pei, D., Sun, Y., Langenhuizen, P.P., Orsini, C.A., Martinsen, K.H., Nordbø, Ø., Bolhuis, J.E. and Bijma, P., 2025. Multi-Object Keypoint Detection and Pose Estimation for Pigs. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (Vol. 3, pp. 466-474).

- Henssen, D.J., Kurt, E., Kozicz, T., Van Dongen, R., Bartels, R.H. and van Cappellen van Walsum, A.M., 2016. New insights in trigeminal anatomy: a double orofacial tract for nociceptive input. Frontiers in neuroanatomy, 10, p.53. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y., Mahmoud, M. and Robinson, P., 2017, May. Estimating sheep pain level using facial action unit detection. In 2017 12th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2017) (pp. 394-399). IEEE.

- Mahato, S. and Neethirajan, S., 2024. Integrating artificial intelligence in dairy farm management− biometric facial recognition for cows. Information Processing in Agriculture. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, D. and Willingham, B., 2009. Spontaneous facial expressions of emotion of congenitally and noncongenitally blind individuals. Journal of personality and social psychology, 96(1), p.1. [CrossRef]

- McLennan, K.M., 2018. Why pain is still a welfare issue for farm animals, and how facial expression could be the answer. Agriculture, 8(8), p.127. [CrossRef]

- McLennan, K.M., Miller, A.L., Dalla Costa, E., Stucke, D., Corke, M.J., Broom, D.M. and Leach, M.C., 2019. Conceptual and methodological issues relating to pain assessment in mammals: The development and utilisation of pain facial expression scales. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 217, pp.1-15. [CrossRef]

- Mota-Rojas, D., Whittaker, A.L., Coria-Avila, G.A., Martínez-Burnes, J., Mora-Medina, P., Domínguez-Oliva, A., Hernández-Avalos, I., Olmos-Hernández, A., Verduzco-Mendoza, A., Casas-Alvarado, A. and Grandin, T., 2025. How facial expressions reveal acute pain in domestic animals with facial pain scales as a diagnostic tool. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 12, p.1546719. [CrossRef]

- Parivendan, S.C., Sailunaz, K. and Neethirajan, S., 2025. Socializing AI: Integrating Social Network Analysis and Deep Learning for Precision Dairy Cow Monitoring—A Critical Review. Animals, 15(13), p.1835. [CrossRef]

- Pennington, Z.T., Dong, Z., Feng, Y., Vetere, L.M., Page-Harley, L., Shuman, T. and Cai, D.J., 2019. ezTrack: An open-source video analysis pipeline for the investigation of animal behavior. Scientific reports, 9(1), p.19979. [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y., Zhao, Y., Ma, H. and Wang, J., 2025. A Lightweight Pig Aggressive Behavior Recognition Model by Effective Integration of Spatio-Temporal Features. Animals, 15(8), p.1159. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M., 2021. PhD Thesis. Towards Automatic Visual Recognition of Horse Pain. University of California, Davis. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2568603713?

- Shibanoki, T., Yamazaki, Y. and Tonooka, H., 2024. A System for Monitoring Animals Based on Behavioral Information and Internal State Information. Animals, 14(2). [CrossRef]

- Tschoner, T., Mueller, K.R., Zablotski, Y. and Feist, M., 2024. Pain Assessment in Cattle by Use of Numerical Rating and Visual Analogue Scales—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Animals, 14(2), p.351. [CrossRef]

- Xu, F., Zhang, J. and Wang, J.Z., 2017. Microexpression identification and categorization using a facial dynamics map. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, 8(2), pp.254-267. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z., Liu, G., Liu, Q. and Deng, J., 2018. Spatio-temporal convolutional features with nested LSTM for facial expression recognition. Neurocomputing, 317, pp.50-57. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., 2024. MicroEmo: Time-Sensitive Multimodal Emotion Recognition with Micro-Expression Dynamics in Video Dialogues. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.16552.

- Zoltick, A.H., Mann, S. and Coetzee, J.F., 2024. Pain pathophysiology and pharmacology of cattle: how improved understanding can enhance pain prevention, mitigation, and welfare. Frontiers in Pain Research, 5, p.1396992. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).