1. Introduction

Human beings are inherently social and rely heavily on communication to interact with one another. Emotions constitute a fundamental form of non-verbal communication and play a critical role in daily interactions [

1]. The rapid development and widespread adoption of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) have paved the way for the automatic recognition of human emotions, giving rise to numerous applications in fields such as Human–Computer Interaction (HCI), healthcare, entertainment, social robotics and Ambient Assisted Living [

2].

Emotions can be expressed and perceived through various modalities, including speech, body gestures, and facial expressions. Automatic emotion recognition systems can be

unimodal, relying on a single modality, or

multimodal, combining multiple sources of information to improve accuracy. The selection of the appropriate modality is non-trivial, as each one conveys different aspects of emotional expression. According to Mehrabian’s well-known study (1968) [

1], facial expressions are the richest source of information for characterizing emotions. In fact, during a typical human interaction, approximately

of the message is conveyed through facial expressions, making them a particularly effective and informative modality for emotion recognition, while the remainder is split between vocal (

) and verbal (

) communication.

Among the foundational studies in the field, the work of Ekman and Friesen [

3] stands out. They introduced the concept of six basic emotions—happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, and disgust—each associated with a distinct facial expression. Furthermore, they developed the Facial Action Coding System (FACS) [

4], a systematic framework for describing facial muscle movements, which laid the groundwork for Automatic Facial Expression Recognition (AFER).

AFER systems can be broadly categorized into two types based on the input data: static systems, which analyze individual images, and dynamic systems, which process image sequences to capture temporal variations. While dynamic systems offer richer information and can improve recognition performance, they often require substantial computational resources and longer processing times. Therefore, enhancing the computational efficiency of dynamic AFER systems remains a key research challenge, especially in the context of real-time applications such as surveillance or interactive systems.

In this work, we propose an efficient dynamic AFER approach for automatically recognizing emotions from facial expressions in image sequences. The method is structured into three main stages. First, during feature extraction, facial landmarks are detected, and all possible Euclidean distances between points are computed to form the spatial representation. To capture temporal variations across the sequence, three statistical metrics are then calculated for each distance, resulting in a compact spatio-temporal feature vector. Given the potentially high dimensionality of this representation, a feature selection step based on the Extremely Randomized Trees (ExtRa-Trees) classifier is employed to retain only the most informative attributes. Finally, for classification, we evaluate two supervised learning algorithms: the linear multi-class Support Vector Machine (SVM), recognized for its robustness and generalization capabilities, and the k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) classifier, known for its simplicity and ease of implementation.

To evaluate the performance of the proposed method, we conducted experiments on three benchmark datasets: CK+ [

5], MUG [

6], and MMI [

7], using several metrics related to recognition accuracy and computational efficiency.

The main three contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

An efficient dynamic AFER approach for emotion recognition from image sequences is proposed.

A novel spatio-temporal representation based on the statistical modeling of geometric features is introduced.

A comprehensive evaluation of recognition accuracy and computational efficiency against state-of-the-art methods is conducted.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 and

Section 3 provide an overview of AFER fundamentals and related work.

Section 4 describes the proposed approach.

Section 5 outlines the experimental setup and datasets used for evaluation. The results and discussion are presented in

Section 6 and

Section 7. Finally, conclusions and future perspectives are drawn in

Section 8.

2. Fundamentals

A basic AFER system shares the same fundamental building blocks as a typical pattern recognition system [

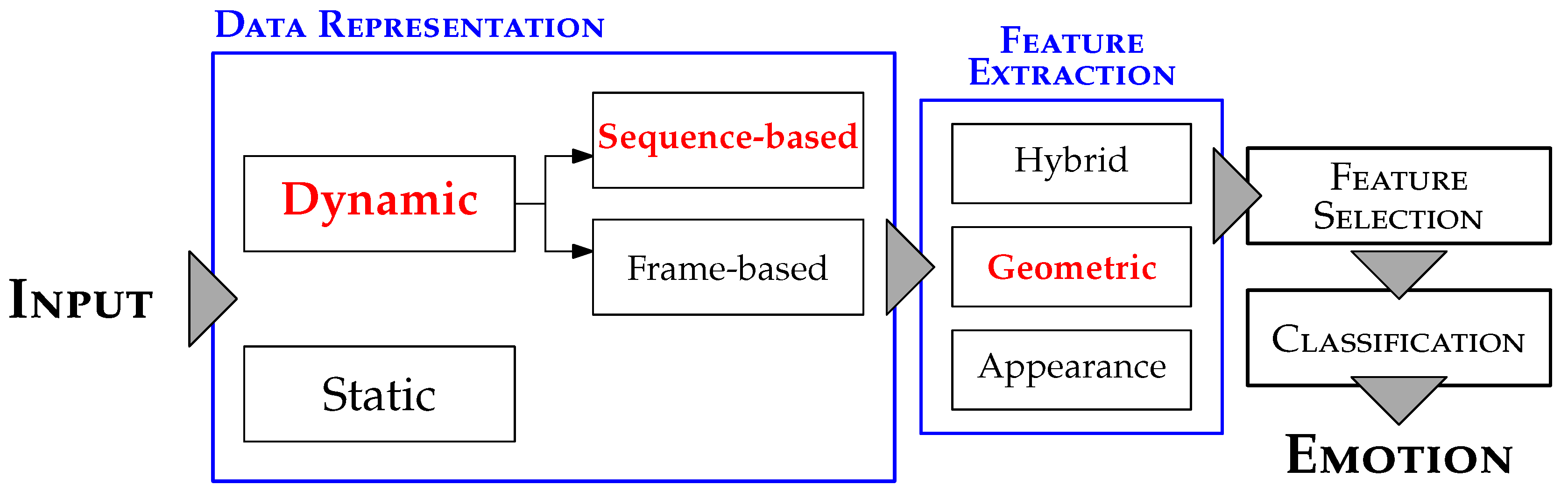

8]. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the first block concerns the

input, and depending on its nature, AFER systems can be classified into two main categories.

Static systems [

9,

10] recognize facial expressions from a single image. Generally, this type of system is less demanding in terms of computational time and resource consumption. However, static systems are limited in their ability to capture the temporal dynamics inherent to real-world facial expressions, which typically evolve through three distinct

transitional phases: (1)

Onset, marking the initial formation of the expression; (2)

Apex, representing the peak of emotional intensity; and (3)

Offset, characterizing the return to the

neutral state. These phases reflect the natural progression of facial deformations, and their full characterization requires analyzing image sequences rather than isolated images.

To address this need,

dynamic systems [

11,

12,

13] have been introduced, capable of processing temporal information to better model the evolution of expressions. Furthermore, depending on how the input data are handled (see

Figure 1), dynamic systems can be subdivided into two approaches:

Sequence-based systems, which exploit the entire image sequence to build a comprehensive and temporal representation of the expression.

Frame-based systems, which process each frame independently, without explicitly modeling the temporal continuity across frames.

Depending on the chosen data representation, the

feature extraction block is adapted accordingly to process the input. As illustrated in

Figure 1, three main types of descriptors can be distinguished in the context of AFER.

Geometric-based features rely on the extraction of facial fiducial points to generate high-level representations [

10], such as the Active Appearance Model (AAM) and the Active Shape Model (ASM) [

14].

Appearance-based descriptors operate on the entire facial image to capture texture information, often through techniques such as the two-dimensional Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) [

15] or the Local Binary Pattern (LBP) [

9].

Hybrid-based descriptors combine both geometric and appearance features [

15]. While hybrid approaches can enhance recognition accuracy, they also tend to increase system complexity, processing time, and computational load.

The feature selection block, although optional, plays a crucial role in improving system efficiency. It aims to reduce the dimensionality of feature vectors by retaining only the most relevant attributes, thereby eliminating redundant and noisy information.

Finally, the classification block typically relies on a supervised machine learning approach. It requires training on labeled samples to build a predictive model capable of classifying new, unlabeled inputs.

3. Related Works

Facial Expression Recognition (FER) has been widely studied, with various approaches proposed for both static and dynamic systems. Dynamic AFER systems, which analyze image sequences, can capture the temporal evolution of facial expressions. However, these systems often face challenges in terms of computational cost, limiting their real-time applicability.

Perveen et al. [

11] proposed a dynamic kernel-based approach that captures local

spatio-temporal representations of facial movements using a universal Gaussian Mixture Model with Mean Interval Kernel (

uGMM-MIK). This method preserves local similarities between frames while managing changes in the global context, demonstrating that probability-based kernels provide superior discriminative performance and matching kernels offer improved computational efficiency. Similarly, Zhang et al. [

12] introduced a hybrid deep learning model combining spatial and temporal Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). Their approach integrates these features into a deep fusion network based on a Deep Belief Network (DBN), leading to improved recognition performance on video-based datasets by effectively capturing both spatial and temporal dynamics.

To capture facial dynamics,

spatio-temporal features are essential. Aghamaleki and Ashkani Chenarlogh [

16] proposed a multi-stream CNN architecture that combines handcrafted features like LBP and Sobel edge maps with CNNs. This method addresses the challenge of limited training data by integrating both handcrafted and learned features, enhancing the model’s ability to recognize dynamic facial expressions. Shahid et al. [

17] further refined this approach by analyzing eleven sub-local facial regions. Their method uses contour and region shape harmonics to model facial variations, improving robustness against challenges such as alignment issues, illumination changes, and occlusions. This localized approach allows for more accurate capture of facial expression dynamics in real-world conditions.

Efficient feature selection plays a crucial role in improving recognition performance while reducing computational costs. Pham et al. [

18] proposed a novel loss function to enhance CNN-based Facial Expression Recognition (FER) performance by minimizing intra-class variation and maximizing inter-class variation, resulting in more discriminative features. This approach significantly improves feature discriminability, making it highly effective for facial expression recognition. Vaijayanthi and Arunnehru [

19] used dense Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) descriptors to capture temporal facial dynamics. These descriptors, combined with machine learning algorithms, enhance the recognition of facial expressions under varying conditions, particularly in dynamic AFER systems that require robust feature extraction from video sequences.

Various classification methods, such as SVMs, have been employed for facial expression classification. Sen et al. [

14] explored the use of Directed Acyclic Graph SVMs (DAGSVM) for

multi-class emotion recognition. Their method efficiently handles multiple emotions, providing faster processing while preserving the discriminative power of SVMs. Kartheek et al. [

20] introduced Windmill Graph-based Feature Descriptors (WGFD) for FER. This graph-based method captures both local and distant relationships between pixels and, combined with a

multi-class SVM, outperforms traditional methods on benchmark FER datasets, demonstrating the effectiveness of graph-based feature descriptors in facial emotion recognition.

Real-time FER systems require methods that can process facial expressions efficiently, as high computational costs often hinder their performance. Lopez-Gil and Garay-Vitoria [

21] addressed this challenge by classifying individual photograms (frame-by-frame images) in video sequences. Their approach combines multiple classifiers to improve efficiency and accuracy, making it suitable for real-time applications. Similarly, Perveen et al. [

11] focused on real-time FER by using dynamic kernels, which manage computational complexity while preserving the discriminative power of

spatio-temporal features.

These related works highlight the importance of both temporal and spatial feature extraction, classification techniques, and computational efficiency in dynamic AFER systems. Our proposed approach builds on these foundations by using statistical spatio-temporal geometric features and feature selection techniques to strike a balance between classification accuracy and computational efficiency, making it well-suited for real-time applications.

3.1. Limitations & Challenges

The review of existing methods highlights several challenges and limitations associated with dynamic AFER systems. One of the most recurrent issues is the necessity of sequence normalization. In practice, the number of frames per image sequence may vary from one sample to another, while most classification techniques require feature vectors of identical size. To address this, many methods define a fixed number of frames and perform sequence normalization accordingly. Typically, this involves duplicating frames for shorter sequences and removing frames from longer ones. Although this operation mitigates the mismatch issue, it alters the original input data by adding or removing information. Alternatively, some authors chose to consider only the initial frame (neutral state) and the frame corresponding to the peak expression (apex), addressing the size constraint at the expense of sequence integrity.

Unlike static systems, dynamic systems are expected to process image sequences rather than single images. To achieve a spatio-temporal representation, several methods extract feature vectors from each frame and then concatenate them into a single descriptor vector. Although this strategy preserves all frames, it often results in very large feature vectors, which can be problematic. Since AFER systems are typically expected to be computationally efficient and suitable for real-time applications, excessive feature vector size can significantly impact processing speed and memory requirements.

In summary, the five key requirements for designing an effective dynamic AFER system include:

Preservation of sequence integrity, without adding or discarding information,

Construction of a spatio-temporal representation with spatial and temporal information.

Efficient processing and recognition suitable for real-time applications,

High accuracy or recognition rate compared to state-of-the-art methods,

Strong robustness when evaluated across different benchmark datasets.

Although this list is not exhaustive, it served as the foundation for the design of our proposed dynamic AFER approach.

4. Proposed Approach

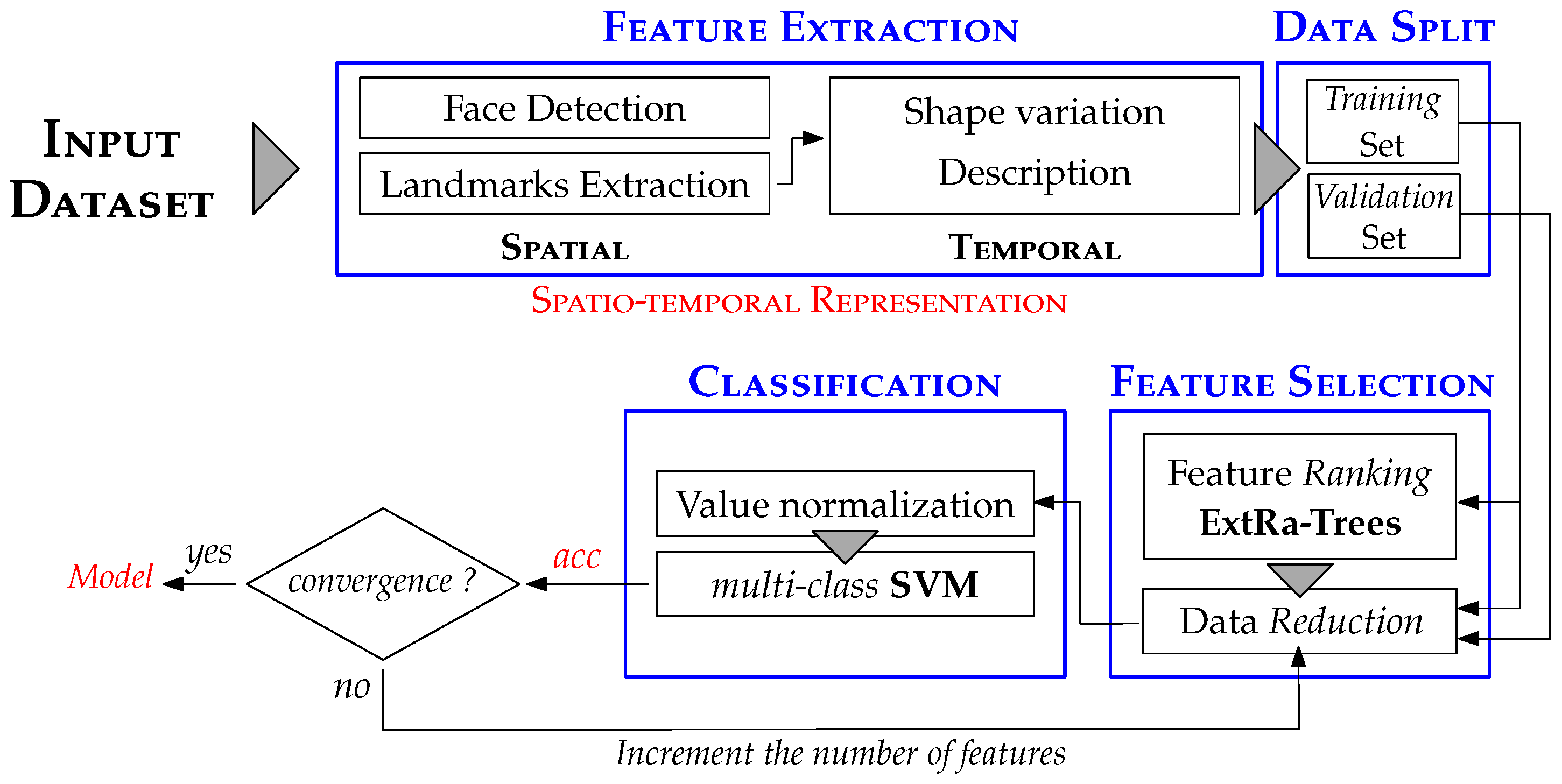

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the proposed

dynamic AFER approach follows the same fundamental building blocks as a typical pattern recognition system (refer to

Section 2). In our case, the

input consists of a facial expression dataset where the number of frames per image sequence may vary.

In the following sections, we detail each component of the proposed dynamic AFER approach, namely feature extraction, feature selection, and classification.

4.1. Feature Extraction

As discussed in

Section 2, three types of features are commonly distinguished in the field of AFER. In our approach, we focus specifically on

geometric-based features, which offer the advantage of being invariant to face translation, rotation, and illumination.

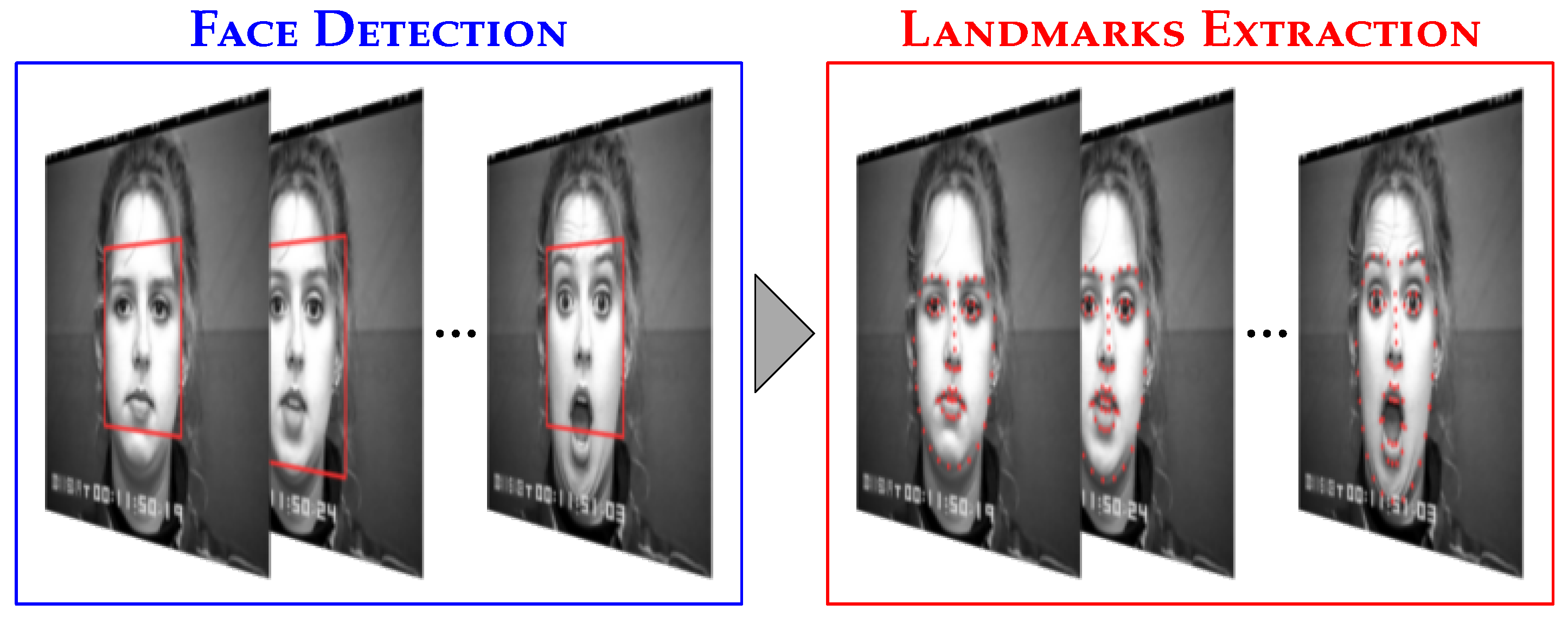

Before computing the feature vectors, we apply the Viola & Jones algorithm [

22] to detect the face region (see

Figure 3). As illustrated in

Figure 2, our method requires a combination of two distinct representations:

spatial and

temporal.

The

spatial representation involves extracting the facial shape. Several techniques, such as AAM and ASM, can be used for this purpose. However, we chose a more recent method introduced by Kazemi & Sullivan [

23], which enables the extraction of

sixty-eight facial fiducial points, as shown in

Figure 3. This technique is based on the following Equation (

1):

Here, the input consists of the current estimation of the face shape

and the input face image

I. The facial shape is defined as

, where each element

represents a specific facial fiducial point. We denote

facial fiducial points, and each point

is represented by Cartesian coordinates

. The goal of Equation

1 is to iteratively adjust the face shape until convergence, using the regression function

, which takes as inputs

and

I. This function is implemented as a cascade of decision trees trained using the gradient boosting method.

Following inspiration from previous works [

13,

24], the spatial representation of the input is achieved by computing all possible Euclidean distances between pairs of facial fiducial points (see Equation

2). For each frame of an image sequence, we have

facial fiducial points, resulting in

possible distances, as shown in Equation

3.

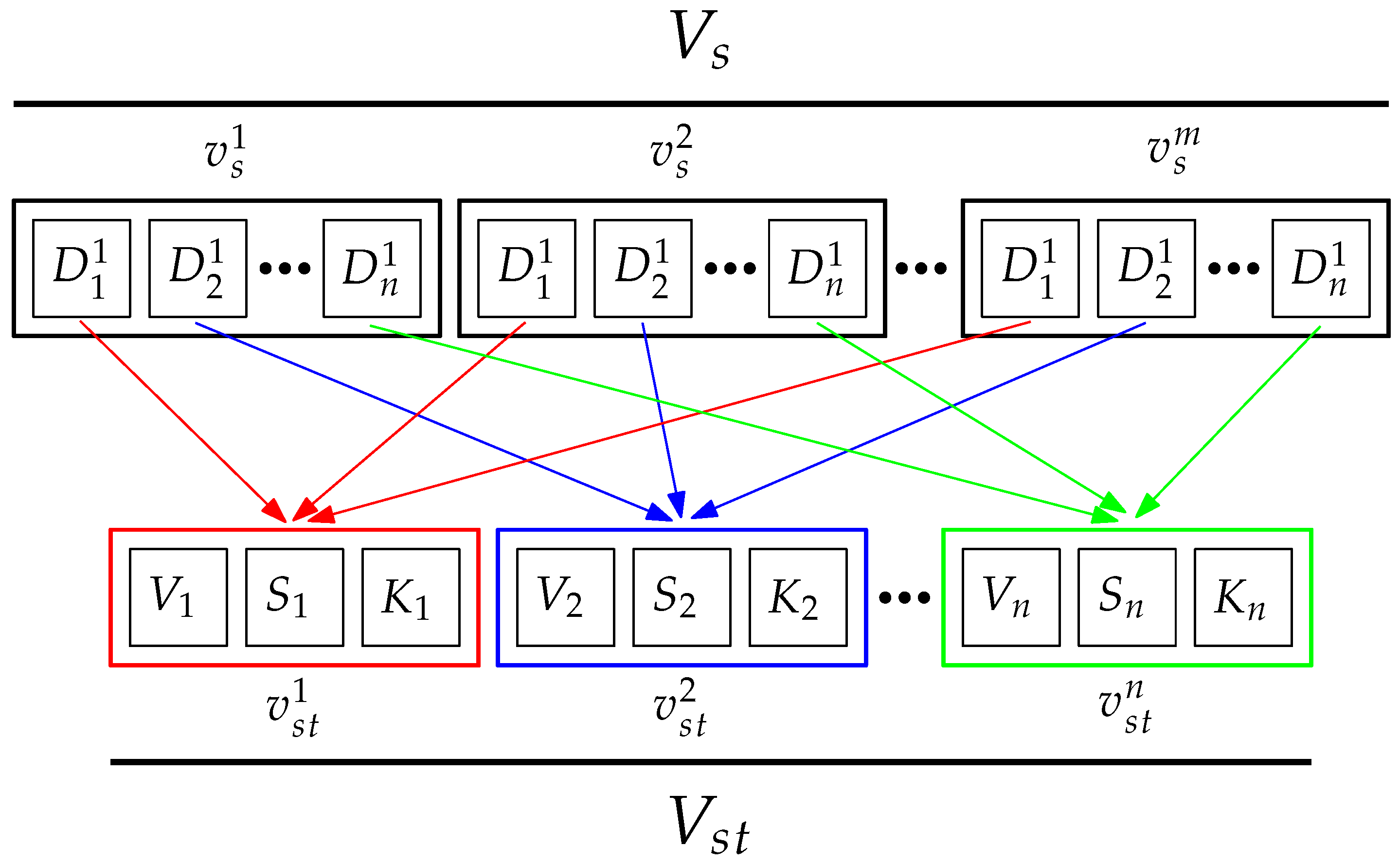

As noted earlier, an image sequence consists of a variable number of frames, denoted as

m. Thus, we must extract

feature vectors, with each vector corresponding to a specific frame in the image sequence (see

Figure 4). The spatial representation can be defined as

, where

is the descriptor vector for the

frame, with

. Each vector

contains all the possible Euclidean distances represented by

, corresponding to the

distance, where

. This representation is inspired by FACS [

4], but instead of using specific distances corresponding to Action Units (AUs), we compute all possible distances.

While the

spatial representation may suffice for recognition, as demonstrated in [

13], it still faces challenges, particularly the variable number of frames in each image sequence. This requires sequence normalization to apply a supervised machine learning technique effectively. Even after normalization, this approach remains computationally expensive in terms of time and resources. To address this issue, we propose a new representation to capture the temporal variations of each Euclidean distance

using statistical metrics. As shown in

Figure 4, the

spatio-temporal representation is defined as

, where each vector

contains a triplet of statistical metrics that represent the temporal variation of the

Euclidean distance. The statistical metrics are as follows: variance (Equation

4), skewness (Equation

5), and kurtosis (Equation

6):

Finally, the resulting spatio-temporal representation of the input is defined by the feature vector . This descriptor vector has distinct attributes.

4.2. Feature Selection

As previously defined, the size of the obtained

spatio-temporal representation is estimated at

. However, it is well-known that a high number of attributes can lead to several issues, such as

overfitting, which arises from redundant or noisy attributes; an increase in training time due to the larger feature space; and a potential accuracy reduction since some attributes may be misleading or irrelevant when constructing the model. To address these challenges, we introduce a feature selection stage (see

Figure 2) aimed at reducing the size of the

spatio-temporal representation.

Several feature selection techniques have been proposed in the literature. Among them, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [

25] remains one of the most common approaches. PCA is a statistical procedure that applies an orthogonal transformation to convert a set of potentially correlated attributes into a set of linearly uncorrelated variables known as principal components. This transformation improves the discriminatory power of the features by maximizing the variance captured in the selected components. Another approach involves ranking attributes by their importance. In this method, each attribute is assigned a score, and the higher the score, the more important the attribute is deemed. Based on these scores, a threshold is applied to select the most relevant attributes, determining the percentage of features to retain.

For our approach, we utilize the ExtRa-Trees technique, which is a variant of Random Forests [

26]. As described in [

27], the ExtRa-Trees algorithm constructs an ensemble of unpruned decision or regression trees using a classical top-down procedure. The key differences between ExtRa-Trees and other tree-based ensemble methods are that node splits are chosen completely at random, and the entire learning sample is used to grow the trees, rather than relying on a bootstrap replica.

In our case, we propose using the ExtRa-Trees technique along with the

Gini index as the

impurity measure. In a supervised manner, the feature vectors, along with their corresponding labels, are employed to build the ExtRa-Trees model. Subsequently, the feature importance is determined by generating score values for each attribute. The attributes are then ranked in descending order of importance. As illustrated in

Figure 2, a threshold is set to select a specific percentage of the most important features. This threshold is incrementally adjusted until the model’s accuracy reaches convergence.

4.3. Classification

Classification represents the final component of the

dynamic AFER approach, enabling the identification of various facial expressions. It relies on a

supervised machine learning technique, requiring a

training or

learning phase with labeled samples. Furthermore, machine learning techniques are often

sensitive to the value range of feature vectors. To improve accuracy, we propose applying a value normalization technique. We employ

min-max normalization, which transforms the data into a predefined range, as shown in Equation

7:

Each element of the original feature vector is represented by v, with its current value range defined by . The new range for the normalized feature vector is , where we set and . While various machine learning techniques can be explored, we focus on two specific ones: k-NN and SVM, also testing other methods for an objective comparison of recognition rates.

4.3.1. SVM Classifier

The Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier is a

supervised machine learning technique introduced by Cortes & Vapnik [

28]. The algorithm constructs a

hyperplane designed to optimally separate two distinct classes. Thus, SVM is a

binary classifier, as it distinguishes between two classes. For

linearly separable datasets, multiple hyperplanes can be used to separate the classes. However, the best choice is the hyperplane that maximizes the margin to the nearest data points, known as the

maximum-margin hyperplane. As defined in [

29], a basic

linear SVM classifier is represented by (see Equation

8):

where

represent the maximum-margin hyperplane,

are the feature vectors, and

are the labels. The SVM algorithm can also handle

nonlinearly separable datasets using the

kernel trick, which maps the data into a transformed feature space to find the maximum-margin hyperplane.

In our case, we employed a linear SVM classifier due to its robustness and generalization capabilities. However, we face a multi-class classification problem, as we need to distinguish between M facial expressions. Fortunately, this limitation can be overcome by combining multiple SVM classifiers. Two strategies are commonly used: 1) One-Against-One, where an SVM classifier is trained for each possible pair of classes, and 2) One-Against-All, where an SVM classifier is built for each class. For the proposed dynamic AFER approach, we chose the One-Against-All strategy, as it requires training fewer classifiers. Additionally, the best performance in terms of accuracy was achieved with the cost variable set to .

The

k-NN classifier is one of the simplest machine learning techniques and belongs to the category of

instance-based methods [

30]. The

learning phase involves storing the training samples, and the

prediction of an unlabeled instance is made by finding the closest neighbors in the training set. Its main advantage over other methods lies in its simplicity and interpretability, as it does not generate a

black-box model. To construct a

k-NN classifier, two parameters must be defined: 1)

k, the number of neighbors to consider for classification, and 2)

, the

distance metric used to compute the distance between training instances and the one to classify. The

k-NN classification is determined by the

majority label among

, where

y are the labels,

is the reordering of training set instances based on the distance

, and

k is the number of nearest neighbors considered.

In our case, we employed the

k-NN classifier as presented in [

13,

24]. The number of neighbors was set to

, and the chosen distance metric

is the

Cosine distance (see Equation

9). In [

24], several other distances such as

Euclidean and

Manhattan were compared, but the best performance was achieved using

Cosine distance:

is computed between two feature vectors and .

4.3.2. Other Classifiers

To provide an objective comparison in terms of accuracy, we also tested two other widely-used classification techniques. The first is the Decision Tree (DT) classifier using the C4.5 algorithm with the Gini index as the impurity measure. The second technique is the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), which utilizes the well-known backpropagation algorithm during the learning phase.

5. Experimentation & Evaluation

This section presents the validation protocol and experimental results obtained for the proposed dynamic AFER approach. We first describe the benchmark datasets used in our evaluation. Next, we detail the adopted validation strategy, followed by a thorough analysis of classification performance based on various evaluation metrics.

5.1. Benchmark Datasets

To evaluate the effectiveness and generalizability of our method, we used three publicly available and widely recognized benchmark datasets. Each dataset consists of facial expression image sequences that capture the temporal evolution of expressions.

Table 1 summarizes their characteristics.

The Extended Cohn-Kanade (CK+) dataset [

5] is one of the most popular in the field. It comprises 327 labeled sequences from 123 different subjects, each annotated with one of seven basic emotions: happiness (HA), anger (AN), disgust (DI), sadness (SA), fear (FE), surprise (SU), and contempt (CO).

The MMI dataset [

7] includes 199 labeled sequences recorded from 31 subjects. It captures the six universally recognized facial expressions, offering a wide range of expression intensities and head movements, making it a robust testbed for dynamic facial analysis.

The Multimedia Understanding Group (MUG) dataset [

6] contains the largest number of sequences—931 in total—recorded from 86 individuals (51 males and 35 females). Its high-resolution image sequences and gradual expression transitions make it particularly well-suited for evaluating dynamic AFER systems.

5.2. Validation Strategy

We adopted a ten-fold stratified cross-validation strategy to ensure reliable and unbiased evaluation. In this setup, each dataset is partitioned into ten folds, maintaining the class distribution across all subsets. The training and evaluation process is repeated over ten iterations, where in each iteration, nine folds are used to train the model and the remaining one for testing. All experiments were conducted on an HP ProBook equipped with an Intel Core i7 processor and 8GB of RAM, providing a balanced environment for performance assessment without relying on high-performance computing resources.

The implementation was carried out using Python and relied on several widely-used open-source libraries, including scikit-learn for machine learning, scikit-image for image processing, and dlib for facial landmark detection. This software stack ensured reproducibility, flexibility, and compatibility with the proposed dynamic AFER approach.

The final recognition performance is computed by averaging the accuracy obtained across all folds. This validation strategy minimizes the effects of random partitioning and ensures that every data point is used for both training and evaluation.

Our experimental evaluation was conducted in the following stages:

Classifier Evaluation: We compared several classification techniques under the same feature extraction pipeline. These included SVM, k-NN, DT, and MLP, allowing us to identify the most effective learning model for our dynamic AFER approach.

Comparison with State-of-the-Art: We benchmarked the performance of our approach against existing methods in the literature using the same datasets and validation setup. This comparison aimed to demonstrate the competitiveness of our method in terms of recognition accuracy.

Detailed Metric Analysis: In addition to accuracy, we also report precision, recall, and F1-score to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of classification performance, especially in the presence of class imbalance.

6. Obtained Results

This section presents and analyzes the results obtained from our experiments. Each evaluation aspect is discussed independently, with a focus on classification performance across different datasets, classifiers, and comparison with state-of-the-art methods.

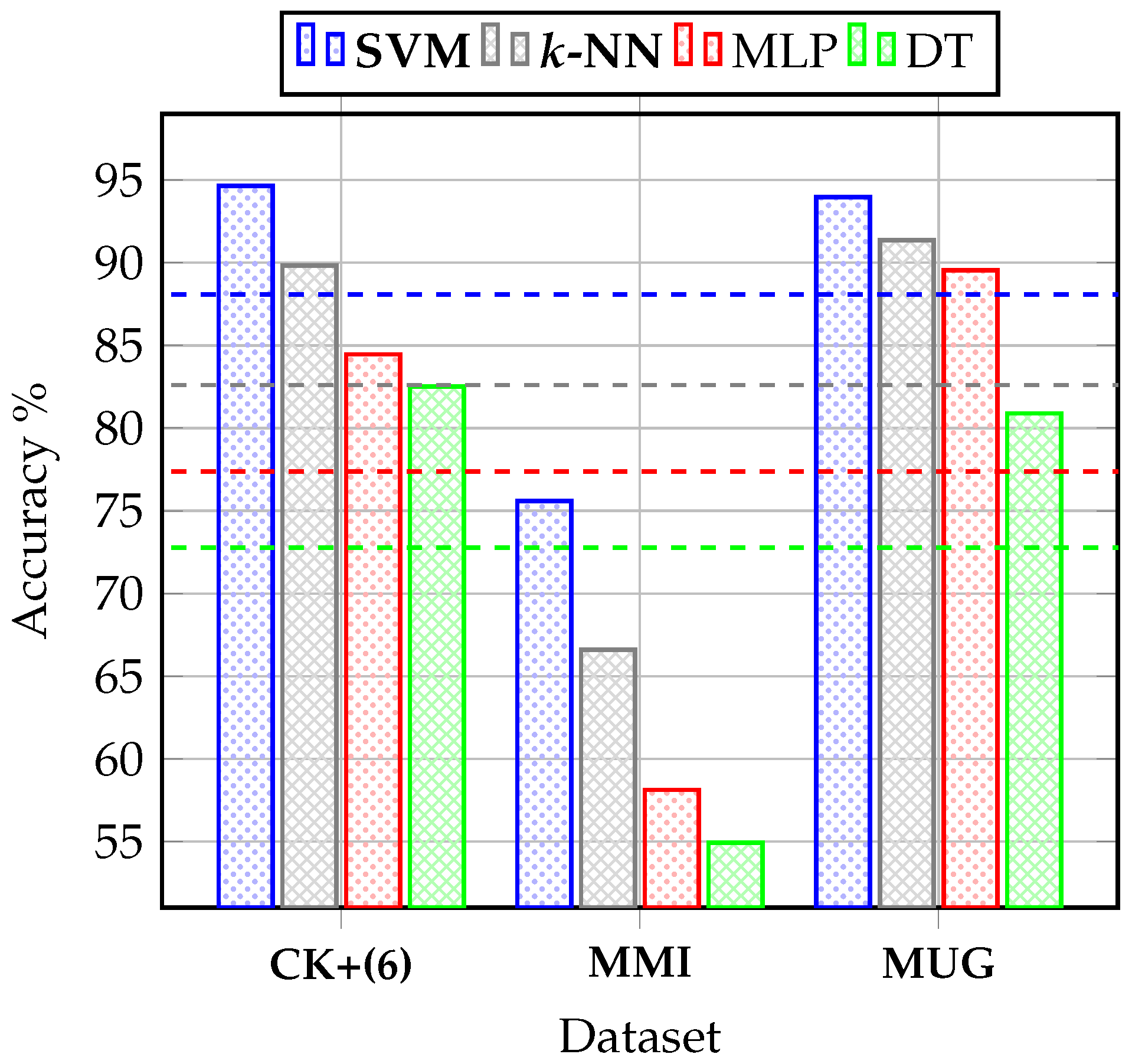

6.1. Performance of Classifiers

Figure 5 illustrates the classification accuracy of the proposed dynamic AFER approach using four machine learning classifiers: SVM,

k-NN, MLP, and DT. The evaluation was carried out on three benchmark datasets: CK+, MMI, and MUG. As observed, SVM and

k-NN consistently outperform MLP and DT across all datasets, making them the most suitable classifiers for our approach.

6.2. CK+ Dataset (Six Basic Emotions)

Table 2 presents the confusion matrix obtained when evaluating the proposed method on the CK+ dataset using six basic emotion classes (happiness, anger, disgust, sadness, fear, and surprise). The model demonstrates high accuracy, especially for happiness and surprise, which are typically easier to distinguish due to their distinct facial muscle activations.

Table 3 compares our method with several

state-of-the-art approaches using the same six-class configuration on CK+. The results indicate that our dynamic AFER system, particularly with the

multi-class SVM classifier, achieves competitive or superior accuracy.

6.3. MMI Dataset

Table 4 reports the confusion matrix for the MMI dataset. Despite its more challenging nature—due to greater variability in head pose and lighting—the model maintains robust performance, particularly for emotions such as happiness and surprise.

As shown in

Table 5, our approach achieves favorable results when compared to existing methods, further confirming its generalization capabilities across datasets with diverse acquisition conditions and subject variability.

6.4. MUG Dataset

Table 6 shows the confusion matrix obtained on the MUG dataset. Thanks to its high-resolution image sequences and smooth expression transitions, the model achieves strong classification results, especially for happiness and disgust.

Table 7 highlights the comparative performance of our system against

state-of-the-art techniques on MUG. Once again, our approach performs competitively, reinforcing its robustness in handling subtle expression variations over time.

6.5. CK+ Dataset (Seven Classes Including Contempt)

To further evaluate the scalability of our method, we extended the CK+ dataset to include the seventh emotion category: contempt.

Table 8 presents the resulting confusion matrix, which shows that while contempt is more challenging to classify, the model still maintains reasonable performance across all classes.

6.6. Detailed Metric Analysis

Table 9 presents a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed approach using five key performance metrics:

F1-Score,

Recall,

Precision,

Accuracy, and

∑ Attributes, which denotes the total number of attributes used for classification. These metrics provide a detailed insight into both the predictive performance and the efficiency of the proposed method.

Table 10 provides an evaluation of the computational efficiency of the proposed method, focusing on the training and prediction phases. Training time was measured using six image sequences for the CK+ (six emotions), MMI, and MUG datasets, and seven sequences for the CK+ dataset including all seven emotions. Prediction time was recorded based on the classification of a single image sequence. These measurements offer valuable insight into the runtime performance of the system in practical settings.

7. Discussion

The initial evaluation highlights the effectiveness of the classification techniques employed. As shown in

Figure 5, the two proposed classifiers, namely SVM and

k-NN, deliver the best results. Specifically, the SVM classifier achieved the highest accuracies:

,

, and

on the CK+, MMI, and MUG datasets, respectively. This outcome validates the selection of these classifiers, particularly the SVM, known for its robustness and generalization capabilities.

The primary focus of this work is the recognition of the

six basic emotions [

24] through facial expressions. Analysis of the confusion matrices presented in

Table 2,

Table 4,

Table 6, and

Table 8 reveals that the proposed approach excels in recognizing emotions such as SU, HA, and DI, with peak accuracies of

,

, and

, respectively. However, challenges persist in identifying the emotions SA, FE, and CO, which recorded lower accuracies of

,

, and

, respectively. These results could stem from the use of a single type of feature descriptor, which seems more effective for recognizing certain emotions like SU, HA, and DI. Additionally, the highest overall accuracy was obtained on the MUG dataset (

), while the lowest accuracy was observed with the MMI dataset (

).

We also compared the proposed approach with existing

state-of-the-art methods in terms of accuracy. The results in

Table 3,

Table 5, and

Table 7 demonstrate that the

dynamic AFER approach outperforms other methods, achieving accuracies of

,

,

, and

on the CK+ (

six emotions), MMI, MUG, and CK+ (

seven emotions) datasets, respectively. These results further underscore the effectiveness of the

spatio-temporal representation combined with the SVM classifier.

The final evaluation examines the performance of the proposed

dynamic AFER approach using various relevant metrics. As shown in

Table 9, our method yields promising results, achieving an average accuracy of

across the three benchmark datasets. In addition, it typically relies on fewer attributes, which helps reduce both processing time and computational load.

One of the most critical considerations when designing a

dynamic AFER system is processing efficiency. As presented in

Table 10, our approach demonstrates faster performance during both the training and prediction phases. Specifically, the training time with the SVM classifier is approximately

s, while the

k-NN classifier—requiring no explicit model training—is even faster at this stage. However, in the prediction phase, the SVM classifier outperforms

k-NN, with a prediction time of around

s, compared to

s for

k-NN.

In summary, the combination of our spatio-temporal representation with the SVM classifier provides the optimal balance between accuracy and computational efficiency.

8. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, we introduced a novel dynamic approach for AFER. Unlike traditional static methods that process individual images independently, dynamic approaches leverage the temporal progression of expressions, capturing richer information across the three transitional phases of a facial expression: onset, apex, and offset. To this end, we proposed an approach, which constructs a compact spatio-temporal representation of expression dynamics over image sequences.

We validated our approach on three widely used benchmark datasets: CK+, MMI, and MUG. A thorough experimental evaluation was carried out in several phases. First, we compared the performance of various classifiers and found that SVM and k-NN consistently achieved the best results. Next, we benchmarked our method against several state-of-the-art approaches. The results demonstrate that our sequence-based dynamic AFER approach, particularly when combined with SVM, outperforms competing methods in terms of classification accuracy.

Furthermore, the proposed method was found to be both effective and efficient. In addition to its superior accuracy, the approach benefits from a reduced number of features and exhibits competitive processing times during both the training and inference phases.

Despite its promising performance, the proposed approach has a few limitations. Currently, it is restricted to frontal-view image sequences, which limits its applicability in real-world, unconstrained environments. Extending the method to handle multi-view or pose-invariant recognition is an important direction for future research. Additionally, the recognition performance for certain emotions—particularly sadness and fear—remains lower compared to other categories. This may be due to the subtle nature of their facial cues and the exclusive use of geometric-based features in our current implementation. Incorporating complementary features, such as appearance-based or deep-learned descriptors, may help improve the recognition rates for these challenging expressions.

Lastly, the effectiveness of our system heavily relies on the accuracy of facial landmark detection. Failures in fiducial point localization can interrupt the entire recognition process. Enhancing the robustness of this preprocessing step is therefore crucial for improving the reliability of the overall system.

In summary, the proposed dynamic AFER approach provides a strong foundation for real-time and temporally aware facial expression recognition. Several promising avenues remain open for future improvement, and we are actively working toward expanding the capabilities and robustness of our system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y.; methodology, Y.Y.; software, Y.Y.; validation, Y.Y.; formal analysis, Y.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y.; writing—review and editing, Y.Y.; visualization, Y.Y.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the reported results are based on publicly available reference datasets widely used in the field, which can be accessed upon request by signing a data usage agreement. These datasets are not owned by the author but were made available through formal access requests according to the specified instructions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4, accessed April 2025) for assistance in correcting grammar, spelling, and improving the overall clarity and formulation of the text during the preparation of this manuscript. The authors have reviewed and edited the generated content and take full responsibility for the final version of the publication. We would also like to express our gratitude to all individuals and organizations that provided the benchmark facial expression datasets — CK+ [

5], MMI [

7], and MUG [

6] — which were instrumental in validating our approach.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AFER |

Automatic Facial Expression Recognition |

| FER |

Facial Expression Recognition |

|

k-NN |

k-Nearest Neighbors |

| AAL |

Ambient Assisted Living |

| AU |

Action Unit |

| CK+ |

Extended Cohn-Kanade |

| MUG |

Multimedia Understanding Group |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

| SIFT |

Scale-Invariant Feature Transform |

| ICT |

Information and Communication Technologies |

| HCI |

Human–Computer Interaction |

| FACS |

Facial Action Coding System |

| Extra-Trees |

Extremely Randomized Trees |

| ASM |

Active Shape Model |

| AAM |

Active Appearance Model |

| DWT |

Discrete Wavelet Transform |

| LBP |

Local Binary Pattern |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| DBN |

Deep Belief Network |

|

uGMM-MIK |

universal Gaussian Mixture Model Mean Interval Kernel |

| DAGSVM |

Directed Acyclic Graph SVM |

| WGFD |

Windmill Graph-based Feature Descriptors |

| PCA |

Principal Component Analysis |

| DT |

Decision Tree |

| MLP |

Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| TL |

Transfer Learning |

| acc |

accuracy |

| HA |

Happiness |

| AN |

Anger |

| DI |

Disgust |

| SA |

Sadness |

| FE |

Fear |

| SU |

Surprise |

| CO |

Contempt |

References

- Mehrabian, A., Communication without words. In Psychology Today, 2 ed.; 1968; pp. 51–52.

- Yaddaden, Y.; Adda, M.; Bouzouane, A.; Gaboury, S.; Bouchard, B. User action and facial expression recognition for error detection system in an ambient assisted environment. Expert Systems with Applications 2018, 112, 173–189. [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. Constants across cultures in the face and emotion. Journal of personality and social psychology 1971, 17, 124. [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P.; Rosenberg, E.L. What the Face Reveals Basic and Applied Studies of Spontaneous Expression Using the Facial Action Coding System (FACS); Oxford University Press, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Kanade, T.; Cohn, J.F.; Tian, Y. Comprehensive database for facial expression analysis. In Proceedings of the 4th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition. IEEE, 2000, pp. 46–53. [CrossRef]

- Aifanti, N.; Papachristou, C.; Delopoulos, A. The MUG facial expression database. In Proceedings of the 11th international Workshop on Image analysis for Multimedia Interactive Services. IEEE, 2010; pp. 1–4.

- Pantic, M.; Valstar, M.; Rademaker, R.; Maat, L. Web-based database for facial expression analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo. IEEE, 2005; pp. 5–pp. [CrossRef]

- Konar, A.; Halder, A.; Chakraborty, A., Introduction to Emotion Recognition. In Emotion Recognition; John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2015; pp. 1–45. [CrossRef]

- Yaddaden, Y.; Adda, M.; Bouzouane, A.; Gaboury, S.; Bouchard, B. Facial sub-regions for automatic emotion recognition using local binary patterns. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Signal, Image, Vision and their Applications (SIVA). IEEE, 2018; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Yaddaden, Y.; Adda, M.; Bouzouane, A.; Gaboury, S.; Bouchard, B. One-class and bi-class SVM classifier comparison for automatic facial expression recognition. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Applied Smart Systems (ICASS). IEEE, 2018; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Perveen, N.; Roy, D.; Chalavadi, K.M. Facial expression recognition in videos using dynamic kernels. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2020, 29, 8316–8325. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Pan, X.; Cui, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, L. Learning affective video features for facial expression recognition via hybrid deep learning. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 32297–32304. [CrossRef]

- Yaddaden, Y.; Adda, M.; Bouzouane, A.; Gaboury, S.; Bouchard, B. Facial Expression Recognition from Video using Geometric Features. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Pattern Recognition Systems. IET, 2017; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Sen, D.; Datta, S.; Balasubramanian, R. Facial emotion classification using concatenated geometric and textural features. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2019, 78, 10287–10323. [CrossRef]

- Yaddaden, Y.; Adda, M.; Bouzouane, A.; Gaboury, S.; Bouchard, B. Hybrid-based facial expression recognition approach for human-computer interaction. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 20th International Workshop on Multimedia Signal Processing (MMSP). IEEE, 2018; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Aghamaleki, J.A.; Ashkani Chenarlogh, V. Multi-stream CNN for facial expression recognition in limited training data. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2019, 78, 22861–22882. [CrossRef]

- Shahid, A.R.; Khan, S.; Yan, H. Contour and region harmonic features for sub-local facial expression recognition. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation 2020, 73, 102949. [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.D.; Duong, M.T.; Ho, Q.T.; Lee, S.; Hong, M.C. CNN-based facial expression recognition with simultaneous consideration of inter-class and intra-class variations. Sensors 2023, 23, 9658. [CrossRef]

- Vaijayanthi, S.; Arunnehru, J. Dense SIFT-based facial expression recognition using machine learning techniques. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Advance Computing and Intelligent Engineering: ICACIE 2021. Springer, 2022; pp. 301–310. [CrossRef]

- Kartheek, M.N.; Prasad, M.V.; Bhukya, R. Windmill graph based feature descriptors for facial expression recognition. Optik 2022, 260, 169053. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Gil, J.M.; Garay-Vitoria, N. Photogram classification-based emotion recognition. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 136974–136984. [CrossRef]

- Viola, P.; Jones, M. Rapid object detection using a boosted cascade of simple features. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. IEEE, 2001, Vol. 1; pp. I–I. [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, V.; Sullivan, J. One millisecond face alignment with an ensemble of regression trees. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2014; pp. 1867–1874. [CrossRef]

- Yaddaden, Y.; Bouzouane, A.; Adda, M.; Bouchard, B. A New Approach of Facial Expression Recognition for Ambient Assisted Living. In Proceedings of the 9th ACM International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments. ACM, 2016, p. 14. [CrossRef]

- Yaddaden, Y. An efficient facial expression recognition system with appearance-based fused descriptors. Intelligent Systems with Applications 2023, 17, 200166. [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [CrossRef]

- Geurts, P.; Ernst, D.; Wehenkel, L. Extremely randomized trees. Machine learning 2006, 63, 3–42. [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Machine Learning 1995, 20, 273–297. [CrossRef]

- Shalev-Shwartz, S.; Ben-David, S. Understanding Machine Learning: From Theory to Algorithms; Cambridge University Press, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Aha, D.W.; Kibler, D.; Albert, M.K. Instance-based learning algorithms. Machine learning 1991, 6, 37–66. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).