Submitted:

29 October 2025

Posted:

30 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement

1.2. Related Works

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data set

2.2. Segmentation and Frame Extraction

2.3. Applied Approach

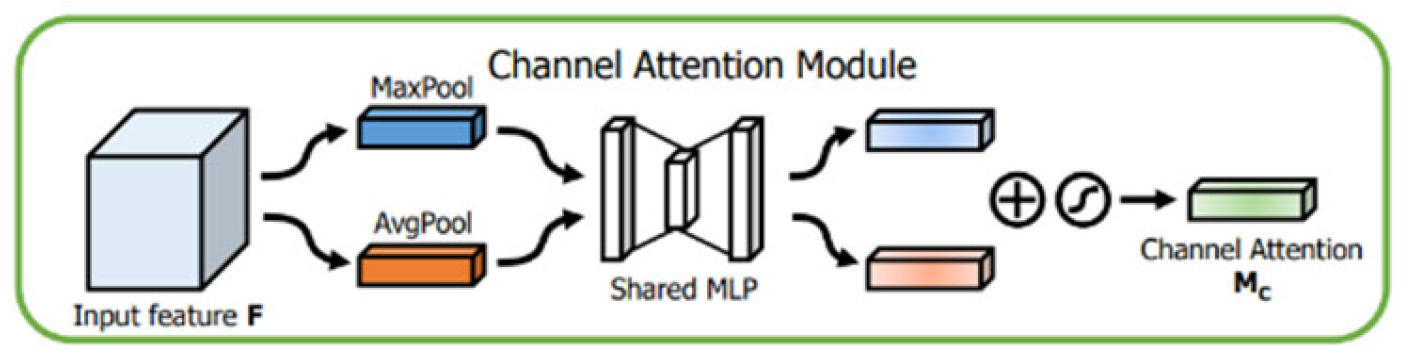

- Data Flow: This module is present in each of the subsequent modules. First, channel attention is computed and multiplied by the input, producing an enhanced representation of the most significant channels. Then, spatial attention is calculated and multiplied by the output of the channel attention step, generating a final representation that emphasizes both relevant channels and spatial regions. The final output is the input image with channel and spatial attention applied, allowing the network to focus on the most relevant features for the task.

- in_channels: Number of input channels (default: 3 for RGB and 2 for grayscale images).

- num_classes: Number of classes for the classification task (default: 3 for RGB images and 2 for grayscale images).

- fc: A sequence of fully connected layers that combines the extracted features and performs classification.

- in_channels: Number of input channels (default: 3 for RGB images and 2 for grayscale images).

- num_classes: Number of classes for the classification task (default: 3 for RGB images and 2 for grayscale images).

- fc: A sequence of fully connected layers that combines the extracted features and performs classification.

- in_channels: Number of input channels (default: 3 for RGB images and 2 for grayscale images).

- num_classes: Number of classes for the classification task (default: 3 for RGB images and 2 for grayscale images).

- hidden_dim: Dimensionality of the additional feature representation (default: 512 for RGB images).

- fc: A sequence of fully connected layers that combines the features from both branches and performs classification.

- in_channels: The number of input channels (default: 3 for RGB images and 2 for grayscale images).

- num_classes: The number of output classes for each convolution branch (default: 3 for RGB images and 2 for grayscale images).

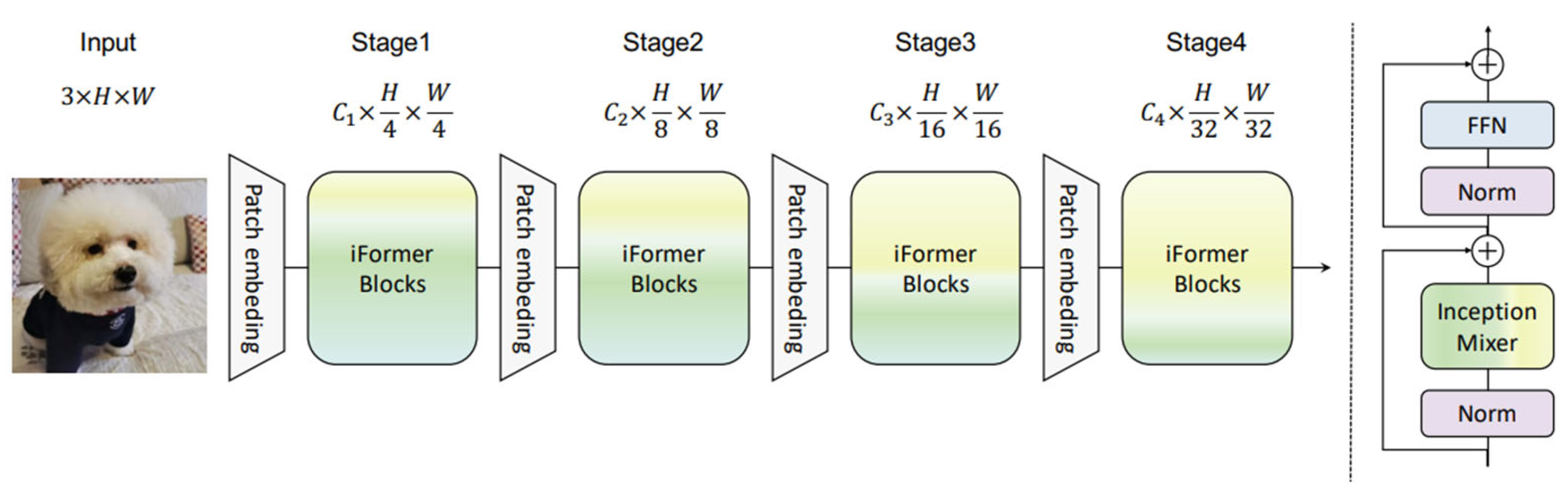

- Inception: Enables efficient extraction of high-frequency features such as textures and local details, which are crucial in many vision tasks. While CNNs excel at this, pure Transformer models tend to focus more on low-frequency, global dependencies. Combining Inception with ViT allows the system to leverage the strengths of both approaches.

- Spatial and Channel Attention with CBAM: By introducing spatial and channel attention methods, the CBAM module improves performance in tasks like object detection and semantic segmentation by enabling the model to selectively focus on the most informative regions and channels.

- Global Dependency Capture with ViT: The primary benefit of ViT is its capacity to use self-attention mechanisms to record long-range dependencies throughout an image. This is especially helpful for duties that call for a comprehensive comprehension of the scene.

- By integrating these three components, the model can:

- Efficiently extract both high- and low-frequency features (Inception)

- Selectively emphasize relevant spatial regions and channels (CBAM)

- Capture global dependencies across the image (ViT)

2.4. Transformer

- The model receives an input image to be classified. The ViT partitions this image into small blocks called patches, which are then transformed into numerical vectors through a process known as linear embedding, analogous to describing the colors of a visual scene using descriptive terms.

- After embedding the patches, the model incorporates positional embeddings, which allow it to retain information about the original spatial arrangement of each patch. This step is critical, as the meaning of visual components may depend on their spatial relationships.

- Once the patches have been embedded and assigned positional information, they are arranged into a sequence and processed through a Transformer encoder. This encoder functions as a mechanism that learns the relationships between patches, forming a holistic representation of the image.

- Finally, to enable image classification, a special classification token is appended at the beginning of the sequence. This token is trained jointly with the rest of the model and ultimately contains the information necessary to determine the image category.

- Patch Embedding: The image is divided into patches and converted into linear embeddings. This is the initial step in preparing the image so that the Transformer can interpret it.

- Classification Token: A special token added to the sequence of embeddings which, after passing through the Transformer, contains the necessary information for image classification.

- Positional Embeddings: Incorporated into the patch embeddings to preserve spatial details about the original position of each patch in the image

- Transformer Blocks: A series of blocks that sequentially process the embeddings using attention mechanisms to understand relationships among the different patches.

- Layer Normalization: Applied to stabilize the embedding values before and after passing through the Transformer blocks.

- Representation Layer or Pre-Logits: An optional layer that may transform the extracted features before final classification, depending on whether a representation size has been defined (patch size).

- Classification Head: The final component of the model that maps the processed features to the predicted classes.

- Mask Generation: An additional layer suggesting that the model may also be designed for segmentation tasks by producing a mask for the image.

- Weight Initialization: Functions that initialize the weights and biases of linear and normalization layers with specific values, providing a suitable starting point for training.

- Additional Functions: Supplementary functions required to exclude certain parameters from weight decay, manipulate the classification head, and define the data flow throughout the model.

- Image Size: Defines the size of the input image and determines how it will be divided into patches (14).

- Patch Size: Specifies the dimensions of each patch (1).

- Input Channels: Indicates the number of channels in the input image (3).

- Number of Classes: Determines the number of output categories for the classification head (1000).

- Embedding Dimension: The embedding dimension for each patch, representing the feature space in which the Transformer operates (512).

- Depth: The depth of the Transformer, referring to the number of sequential Transformer blocks in the model (3).

- Number of Attention Heads: The count of attention heads in every Transformer block allows the model to concentrate on various parts of the image at the same time (4)

- MLP Ratio: The ratio between the hidden layer size of the multilayer perceptron (MLP) and the embedding dimension (2).

- Query-Key-Value Attention Bias: Enables bias terms in the query, key, and value projections when set to true (True).

- Attention Dropout Rate: The dropout rate applied specifically to the attention mechanism for regularization (0.3).

- Attention Head Dropout Type: Specifies the dropout strategy applied to the attention heads (e.g., HeadDropOut).

- Attention Head Dropout Rate: The dropout rate applied to the attention heads (0.3).

2.5. Mathematical Foundation

- For each image patch is compressed into a vector of length , where .

- A series of embedded image patches is produced by mapping the flattened patches into D dimensions using a trained linear projection .

- A learnable class embedding is prepended to the sequence of embedded image patches. The value of represents the classification output .

- Channel (channel: 48): The number of input channels.

- Reduction (reduction: 16): Used to reduce the channel dimension in the fully-connected layers, enabling greater computational efficiency.

- Kernel Size (k_size: 3): The kernel size for the 2D convolution used in spatial attention.

-

Grouping ChannelWhere:X is the input tensor of dimensions c×h×w.i and j are the spatial coordinates.c is the number of channels.h,w are the height and width of the image, correspondingly.

-

Convolution LayerWhere:Y is the convolution output.X is the input.W is the convolution kernel.k is the kernel size.

-

Batch NormalizationWhere:μ and σ2 are the mean and variance of Y calculated over the batch.γ and β are the learned scale and bias parameters, respectively.ϵ is a constant for numerical stability.

-

Sigmoid ActivationWhere:Z is the input of the sigmoid function, which is the output of the Batch Normalization layer.

-

Spatial Attention MaskWhere:X is the input tensor.Z is the output of the convolution layer continued by Batch Normalization and Sigmoid Activation.

-

Squeeze Operation: The "squeeze" operation consists of reducing the spatial dimensions of a feature tensor X (with dimensions ) to a single-channel feature tensor (dimensions ). This is achieved through Global Average Pooling:Where:Si represents the "squeeze" value for channel , indicating the importance of the channel relative to the other channels.

-

Excitation Operation: The "excitation" operation uses fully linked layers to model the relationships between channels and to learn attention weights.Where:δ represents an activation function (in this case, ReLU).W1 and W2 are learned weight matrices.

-

Scale Operation: The "scale" operation scales the original feature channels using the attention weights calculated in the "excitation" stage.Where:Yijk is the final value of the output tensor Y after applying channel attention, where each value of channel i at spatial position (j,k) is scaled by the excitation weight Ei.

- in_channels: 3 input channels.

- out_channels: 6 output channels for each convolutional branch.

- input_size: Number of input features per time step.

- hidden_size: Dimensionality of the hidden vector () and the cell state (.

- batch_first: If True, the LSTM input and output will have the shape .

- ft is the activation vector of the forget gate.

- serve as the sigmoid function, which converts input values into the range [0, 1].

- Wf is the weight matrix for the forget gate.

- contains the chain of the previous hidden state and the current input.

- bf is the bias of forget gate.

- is the activation vector of the input gate.

- serves as the sigmoid function, which regulates the amount of new information added.

- is the new candidate memory that can be added to the cell state.

- is the hyperbolic tangent function, which converts input values into the range [-1, 1].

- Wi, bi are the weights and bias of the input gate, correspondingly.

- Wc, bc are the weights and bias for the candidate memory, correspondingly.

- is the updated cell state.

- ⊙ denotes the element-wise product operation.

- ft⊙Ct−1 represents the data maintained from the previous cell state.

- represents the new information added to the cell state.

- ot is the activation vector of the output gate.

- ht is the hidden state and output of the LSTM at the current time step.

- Wo is the weight matrix for the output gate.

- contains the concatenation of the prior hidden state and the current input.

- is the bias of the output gate.

- σ serves as the sigmoid function, which regulates the amount of information emitted.

- is the hyperbolic tangent function applied to the cell state.

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- S. Xunbing y S. Huajie, «The time — frequency characteristics of EEG activities while recognizing microexpressions,» IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference (BioCAS), pp. 180-183, 2016.

- M. Hoon Yap, A. Davison y W. Merghani, A Review on Facial Micro-Expressions Analysis: Datasets, Features and Metrics, 2018.

- D. Matsumoto, H. Sung Hwang, R. M. López y M. Á. Pérez Nieto, «Lectura de la expresión facial de las emociones: Investigación básica en la mejora del reconocimiento de emociones,» Ansiedad estrés, pp. 121-129, 2013.

- Michael Revina y, W. Sam Emmanuel, «A Survey on Human Face Expression Recognition Techniques,» Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences, vol. 33, nº 6, pp. 619-628, 2021.

- C. Felipe Zago, T. Rossi Müller, J. C. Matias, G. Gino Scotton, A. Reis de Sa Junior, E. Pozzebon y A. C. Sobieranski, «A survey on facial emotion recognition techniques: A state-of-the-art literature review,» Information Sciences, vol. 582, pp. 593-617, 2022.

- P. Ekman y W. Friessen, Unmasking the Face, Consulting Psychologists Press, Consulting Psychologists Pr, 1984.

- D. Strauss, G. Steidl, C. Heiß y P. Flotho, Lagrangian Motion Magnification with Landmark-Prior and Sparse PCA for Facial Microexpressions and Micromovements, Scotland, Glasgow, 2022, pp. 2215-2218.

- Z. Yuan, Z. Wenming, C. Zhen, Z. Guoying y H. Bin, «Toward Bridging Microexpressions From Different Domains,» IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics, vol. 50, nº 12, pp. 5047-5060, 2020.

- F. Ike, M. Ronny y P. Mauridhi Hery, «Detection of Kinship through Microexpression Using Colour Features and Extreme Learning Machine,» 2021 International Seminar on Intelligent Technology and Its Applications (ISITIA), pp. 331-336, 2021.

- F. M. Cristina, P. M. J. Carlos, S. R. Joaquim y F. A. Enrique, «Validación española de una batería de películas para inducir emociones,» Psicothema, vol. 23, nº 4, pp. 778-785, 2011.

- E. Navarro-Corrales, «El lenguaje no verbal,» de Revista Comunicación, vol. 20, 2011, pp. 46-51.

- R. R. Herrera, S. De La O Torres and R. A. O. Martínez, "Recognition of emotions through HOG," 2018 XX Congreso Mexicano de Robótica (COMRob), Ensenada, Mexico, 2018, pp. -6. [CrossRef]

- P. Ekman, An argument for basic emotions. Cognition and Emotion, vol. 6, 1992, pp. 169-200.

- P. Ekman y O. Harrieh, «Expresiones faciales de la emoción,» Annual Review of Psycology, nº 30, pp. 527-554, 1979.

- P. Ekamn, Emotions revealed: Recognizing faces and feelings to improve communication and emotional life, Times Books/Henry Holt and Co., 2003.

- T. Kay, Y. Ringel, K. Cohen, M.-A. Azulay y D. Mendlovic, Person Recognition using Facial Micro-Expressions with Deep Learning, 2023.

- M. H. Yap, J. See, X. Hong y S.-J. Wang, Facial Micro-Expressions Grand Challenge 2018 Summary, Xi'an, China: IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2018), 2018, pp. 675-678.

- W. Chongyang, P. Min, B. Tao y C. Tong, «Micro-Attention for Micro-Expression Recognition,» In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 6339-16347, 2018.

- S.-J. Wang, B.-J. Li, Y.-J. Liu, W.-J. Yan, X. Ou, X. Huang, F. Xu y X. Fu, «Micro-expression recognition with small sample size by transferring long-term convolutional neural network,» IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, pp. 251-262, 2018.

- S. Wang, S. Lv and X. Wang, "Infrared Facial Expression Recognition Using Wavelet Transform," 2008 International Symposium on Computer Science and Computational Technology, Shanghai, China, 2008, pp. 327-330. [CrossRef]

- «Modelo basado en componentes,» Metodologías de Software, 01 12 2017. [Online]. Available: https://metodologiassoftware.wordpress.com/2017/12/01/modelo-basado-en-componentes/. [Last accessed: 09 abril 2023].

- B. Jubair, S. Humera y S. Abdul Rawoof, «An Approach to generate Reusable design from legacy components and Reuse Levels of different environments,» International Journal of Current Engineering and Technology, vol. 4, nº 6, pp. 4234-4237, 2014.

- J. Happe y H. Koziolek, A QoS Driven Development Process Model for Component-Based Software Systems, vol. 4063, Springer, Ed., Berlin, Heidelberg, 2006.

- E. Jolly, J. H. Cheong, T. Xie y L. J. Chang, «py-feat,» 2022. [Online]. Available: https://py-feat.org/basic_tutorials/02_detector_imgs.html. [Last accessed: 26 04 2024].

- J. Fu, J. Liu, H. Tian, Y. Li, Y. Bao, Z. Fang y H. Lu, «Dual Attention Network for Scene Segmentation,» IEEE Xplore, pp. 3146-3154, 2019.

- G. Bertasius, H. Wang y L. Torresani, Is Space-Time Attention All You Need for Video Understanding?, 2021.

- Vaswani, N. Shazeer, N. Parmar, J. Uskoreit, L. Jones, A. Gomez, L. Kaiser y I. Poluskhin, «Attention is all you need,» Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pp. 5998-6008, 2017.

- Dosovitskiy, L. Beyer, A. Kolesnikov, D. Weissenborn, X. Zhai, T. Unterthiner, M. Dehghani, M. Minderer, G. Heigold, S. Gelly, J. Uszkoreit y N. Houlsby, «An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale,» 2020.

- D. Kong, J. Zhang, S. Zhang, X. Yu and F. A. Prodhan, "MHIAIFormer: Multihead Interacted and Adaptive Integrated Transformer With Spatial-Spectral Attention for Hyperspectral Image Classification," in IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, vol. 17, pp. 14486-14501, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Si, W. Yu, P. Zhou, Y. Zhou1, X. Wang y S. Yan, «Inception Transformer,» Preprint. Under review, 2022.

- Calzone, «medium,» An Intuitive Explanation of LSTM, 21 02 2022. [Online]. Available: https://medium.com/@ottaviocalzone/an-intuitive-explanation-of-lstm-a035eb6ab42c. [Last accessed: 29 05 2024].

- F. T. Sánchez García, B. Y. L. López Lin y R. Romero Herrera, «DETECTION OF FACIAL MICRO-EXPRESSIONS USING CNN,» JATIT, vol. 101, nº 23, pp. 7592-7601, 15 Diciembre 2023.

- T.-K. Tran, Q.-N. Vo, X. Hong, X. Li y G. Zhao, «Micro-expression spotting: A new benchmark,» ELSEVIER, vol. 443, pp. 356-368, 2021.

- L. Torres, «The Machine Learners,» Curva ROC y AUC en Python, [Online]. Available: https://www.themachinelearners.com/curva-roc-vs-prec-recall/. [Last accessed: 31 05 2024].

| Feature | CASME II | SAMM | SMIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Sample | 255 | 159 | 164 |

| Participants | 35 | 32 | 16 |

| Ethnicities | Chinese | Chinese and 12 more | Chinese |

| Facial Resolution | 280x340 | 400x400 | 640x480 |

| Happiness (25) | Happinese (24) | ||

| Surprise (15) | Surprise (13) | Positive (51) | |

| Categories | Anger (99) | Anger (20) | Negative (70) |

| Sadness (20) | Sadness (3) | Surprise (43) | |

| Fear (1) Others (69) | Fear (7) Others (84) |

| Model version | Number of epochs | Training time | Loss of training | Accuracy | F1 score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without Optical Flow | 60 | 1 hour 45 minutes and 58 seconds | 0.2108 | 90.28% | 0.8453 |

| With Optical Flow | 100 | 23 minutes and 55 seconds | 0.0986 | 90% | 0.8556 |

| Training loss | Accuracy | Epochs | Training time | CPU usage | Memory usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1917 | 0.9474 | 60 | 8 minutes 38 seconds | 13.3% | 72.1% |

| F1-Score | Precision | Accuracy | Recall | Mean square error (MSE) | Mean absolute error (MAE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.8574 | 0.8127 | 0.8519 | 0.8127 | 0.2278 | 0.2175 | 0.8243 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).