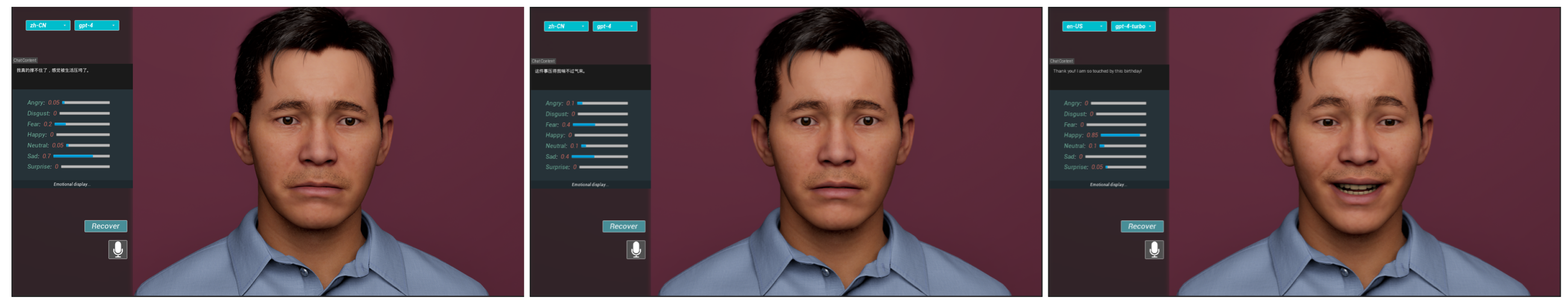

Figure 1.

The software converts the received voice into text and sends it to GPT for sentiment analysis. The analysis results are shown in the figure. Based on the sentiment, the software drives 3D digital humans to generate corresponding facial expressions and movements.

Figure 1.

The software converts the received voice into text and sends it to GPT for sentiment analysis. The analysis results are shown in the figure. Based on the sentiment, the software drives 3D digital humans to generate corresponding facial expressions and movements.

1. Introduction

As human-computer interaction (HCI) scenarios become increasingly complex, users are placing higher demands on the subtlety, realism, and emotional responsiveness of digital human facial expressions. However, current mainstream digital avatar expression systems still suffer from significant limitations. On the one hand, most systems based on Facial Action Coding System (FACS)-coded rule frameworks rely heavily on predefined AU combinations, BlendShape animations, or unimodal Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)-based control strategies. These approaches are typically restricted to single-emotion rendering and lack capabilities in semantic understanding, emotional blending, and real-time interactivity [

1]. On the other hand, although new-generation systems such as BEAT [

2] and EMAGE [

3] have incorporated linguistic and audio cues to enhance interactive coherence [

4], they still fall short in supporting multi-context, multi-affect concurrent HCI requirements.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes a digital human system framework that integrates multimodal emotion recognition with composite facial expression generation. Centered on the pipeline of “speech-semantic perception — multimodal emotion recognition — AU-level 3D facial expression control,” the framework enables real-time responses and compound emotional expressions. (1) By fusing textual semantics, vocal prosody, and facial AU features, a ResNet18-based model is constructed on the AffectNet dataset to classify seven basic emotions, achieving robust emotion perception under multimodal conditions; (2) An AU motion curve generation module is developed based on the Unreal Engine, which employs a state machine mechanism to support dynamic synthesis and fine-grained control of 3D expressions for the seven basic emotions, thereby enhancing expression naturalness and temporal fluidity; (3) A GPT-4-based semantic understanding module is introduced to analyze emotional content in speech text across multiple dimensions, outputting structured emotion types and weighted distributions that are mapped to the AU control layer, thus forming a closed-loop “language-driven to expression generation” response system.

The proposed system framework achieves full-chain integration of multimodal perception, compound emotion recognition, and AU-level 3D expression control. It overcomes the traditional bottleneck of expressing only single-emotion and single-modality states in digital humans, and supports expressive capabilities aligned with human-like features such as “multi-emotion co-occurrence — emotion transition — semantic responsiveness.”

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

Proposes the first compound emotion recognition framework that integrates voice, text, and facial features, supporting multi-emotion co-occurrence and weighted emotion perception.

Develops an AU-driven 3D facial expression mixer combined with a state machine mechanism, enabling dynamic synthesis and control of blended emotional expressions.

Designs an innovative generation agent module that bridges GPT-based semantic analysis with 3D expression control, enabling a real-time “speech-to-expression” response system.

Validates the proposed system on the AffectNet dataset and Unreal Engine platform, demonstrating superior performance in recognition accuracy, expression naturalness, and interaction responsiveness.

This framework establishes a solid technical foundation for digital humans with realistic, dynamic, and semantically interactive expressive capabilities, offering significant research value and practical application potential.

In addition, a subjective perception experiment is designed to evaluate the perceptual quality of the generated micro-expressions across three key dimensions: clarity, naturalness, and authenticity. This further verifies the effectiveness of the proposed system in enhancing emotional expressiveness in digital humans.

In summary, the goal of this research is to develop a unified technical framework that integrates micro-expression recognition, temporal extraction, and animation driving. The proposed system fills a critical gap in current virtual human modeling by enabling high-fidelity emotional rendering at a fine-grained level, offering a viable technological pathway for advancing the realism and emotional responsiveness of digital avatars.

2. Related Work

2.1. Facial Expression Mapping for Digital Humans

Since the early 1970s, facial expression generation has attracted extensive attention from researchers. Parke et al. [

5] suggested that, in terms of output, the face can be represented either as a two-dimensional image or a three-dimensional surface model. Ekman et al. [

6] proposed the first method linking facial muscle movements to facial expressions. Through careful analysis of video recordings of facial expressions, they defined the FACS, which specifies how each facial expression corresponds to specific muscle contractions. Based on FACS, Waters [

7] identified shared parameters across different human faces and applied them to 3D surface models, enabling more general and flexible control of facial expression generation. Building on Waters’ work, Terzopoulos et al. [

8] further improved the expression generation process, allowing early graphics workstations to achieve real-time facial simulation. Zhang et al. [

9] introduced a hierarchical structure composed of four layers: a mass-spring mesh for facial skin, a muscle actuator layer for facial motion control, a skull mesh, and additional meshes for representing eyes and teeth.

Pighin et al. [

10] proposed mapping 2D facial images onto 3D surface models. ERI, Zhang et al. [

11], introduced improvements to conventional facial expression mapping methods. Zhou et al. proposed a kernel-based decomposition model to parameterize both facial expression and facial identity. Raouzaiou et al. [

12] adopted this approach to model facial animation by displaying the corresponding control point positions on a standardized face.

Inspired by these works, we perform AU mapping directly onto the 3D model and define a set of motion curve mapping rules for each AU. The AU motion curve correspondence table is provided in the Supplementary Material (Table S1).

2.2. Selection of Backbone Network for Facial Emotion Recognition

In facial expression recognition tasks, the choice of backbone network critically affects both model performance and computational efficiency. Boughara et al. [

13] proposed a deductive training strategy based on multilayer perceptrons (MLPs), relying on manually defined combination parameters and iterative mechanisms, and utilizing perceptual image descriptors to extract bio-inspired visual features. However, such shallow models exhibit limited generalization capabilities when handling complex expression variations. To improve recognition accuracy, Mollahosseini et al. [

14] developed a deep convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture incorporating multiple Inception modules. Shin et al. [

15] further analyzed the performance of various deep CNN (DCNN) architectures for facial emotion classification, noting that although deep networks possess strong expressive power, they suffer from latency and resource consumption issues in real-time applications. In recent years, lightweight networks such as the MobileNet family have gained significant attention due to their compact architecture and low computational cost. However, in practical scenarios—especially on large-scale, high-variability emotion datasets like AffectNet [

16]—MobileNet’s recognition accuracy remains significantly lower than that of mainstream architectures such as ResNet and EfficientNet [

17,

18], falling short of the robustness requirements for high-performance emotion recognition tasks.

To address this, we systematically compared five representative model architectures on the AffectNet dataset: MLP [

13], MobileNetV2 [

17,

18], ResNet18 V3-Opt [

19,

20], and ResNet50 [

21,

22]. Performance was evaluated across four key metrics: F1-score, classification accuracy, inference time, and model size. As shown in

Table 1, ResNet18-v2 achieved the highest results in both accuracy (Accuracy = 0.552) and F1-score (F1 = 0.550), demonstrating strong generalization capability for emotion classification tasks. While ResNet50 showed competitive accuracy, its large parameter count makes it unsuitable for deployment. MobileNetV2 exhibited advantages in model size (8.52MB) and inference speed (5.85ms), yet its accuracy (0.504) and F1-score (0.505) were inferior to those of the ResNet series. Although the MLP offered some speed advantage, its classification performance was significantly lower than all other models, rendering it impractical.

Considering both recognition performance and deployment feasibility, this work ultimately selects ResNet18-v2 as the backbone network for the facial expression recognition module. This choice ensures high accuracy in emotion recognition while maintaining real-time responsiveness, providing an efficient and stable feature foundation for subsequent emotion-driven expression synthesis.

2.3. Facial Animation Generation and Real-Time Interaction Technologies

In the study of nonverbal communication, facial expressions have consistently played a central role. Their realistic and controllable rendering is critical for experimental control and human-computer interaction (HCI) design. Early research primarily relied on static images or actor-performed datasets, such as the emotion-induction materials developed by Bänziger et al. [

23], or standardized emotional expressions simulated by actors [

16,

24,

25]. Tcherkassof et al. [

26] further proposed recording spontaneous facial responses of subjects under specific contextual stimuli to enhance the naturalness of emotional expressions. However, constructing such datasets incurs high costs, offers limited reusability, and typically requires intensive manual annotation and post-processing.

To address these limitations, some researchers have shifted toward automated facial modeling tools, such as HapFACS [

27] and FACSGen [

28]. HapFACS provides control interfaces for 49 facial Action Units (AUs), supports EmFACS-based emotion generation, and enables real-time control through APIs. However, it depends on the commercial Haptek engine, making it difficult to port, and its complex user interface poses a barrier for researchers outside the graphics domain. Although FACSGen is open-source, it is functionally limited—supporting only 35 AUs—and lacks capabilities for real-time interaction.

In summary, although existing facial expression generation tools have made notable contributions in both research and application contexts, they generally suffer from high usability barriers, complex operation procedures, and a lack of real-time interaction support. These shortcomings limit their suitability for highly dynamic HCI scenarios. To enhance the realism, responsiveness, and interactivity of virtual agents, there is an urgent need for a 3D facial modeling and driving system that combines low operational complexity with robust interactive performance.

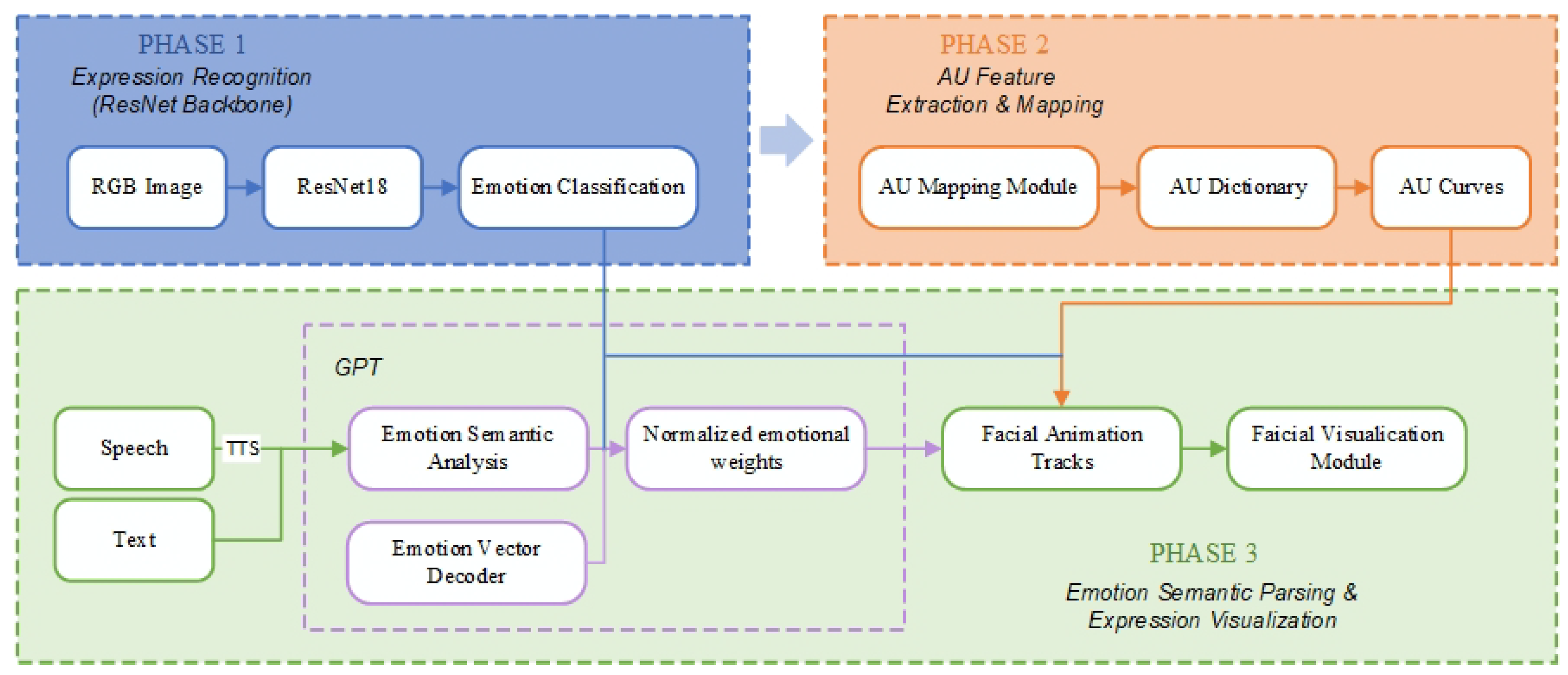

3. Framework

This study proposes a digital human generation framework for compound emotion expression, aiming to achieve natural, dynamic, and semantically responsive facial expression control for virtual agents. The overall architecture consists of three core modules, as illustrated in

Figure 2: (1) a multimodal emotion recognition module; (2) an AU motion mapping module; and (3) an emotion-semantic parsing and expression visualization module. These components form a closed-loop pipeline from speech-semantic input to 3D facial animation output, covering the full spectrum from high-level semantic perception to low-level muscle actuation.

The system follows a processing logic of “semantic-driven — emotion recognition — AU control — expression generation,” integrating key technologies from deep learning, natural language understanding, and graphical animation. This design significantly enhances the expressive power and interactivity of digital humans under complex emotional conditions. The system not only enables efficient integration of multimodal perception, compound emotion recognition, and AU-level animation generation, but also establishes— for the first time— an end-to-end workflow that supports multi-emotion co-occurrence, dynamic emotional transitions, and semantically linked feedback. It offers a general paradigm for building emotionally interactive virtual humans with high interactivity.

3.1. ResNet18-Based Facial Expression Recognition Backbone

Network Architecture Design: As shown in

Table 2, this study adopts ResNet18[

22] as the backbone for facial expression-based emotion classification. The network takes standard RGB color image sequences as input, with each frame resized to

. The output corresponds to one of seven basic emotions.

Specifically, the input image is first processed by an initial convolutional layer (Conv1) to extract low-level texture features. This layer contains 64 convolutional kernels of size , with a stride of 2, producing an output feature map of dimensions . A subsequent optional MaxPooling layer with a kernel size of and a stride of 2 is used to reduce the spatial dimensions, resulting in an output of .

The backbone network consists of four residual blocks (ResBlocks), each composed of two stacked convolutional layers. ResBlock1 outputs a feature map of ; ResBlock2 outputs ; ResBlock3 outputs ; and the final ResBlock4, fine-tuned for task-specific optimization, extracts semantically rich emotion-discriminative features with an output of .

The resulting feature map is then fed into a Global Average Pooling (GAP) layer, compressing it into a spatially invariant one-dimensional feature vector

. This vector is subsequently passed through a fully connected layer to perform linear mapping and generate the final class scores.

Finally, a Softmax activation function is applied to map the logits into a normalized probability distribution for emotion classification:

where

denotes the logit score for the

i-th emotion class. The final predicted emotion is determined by argmax(

), i.e., the class with the highest probability. Simultaneously, the 7-dimensional confidence vector is retained for further analysis or multimodal fusion.

3.2. AU Extraction and Mapping

To achieve high-fidelity expression-driven control, this study proposes a facial animation curve generation mechanism based on Action Units (AUs) [

6], converting facial motion encodings from static images into keyframe curves that can be directly utilized by digital human animation systems.

The process is as follows: The system first employs OpenCV to extract and align facial regions from the image with the highest classification probability output by ResNet18. Then, using a predefined AU mapping dictionary, the AU activation states corresponding to the identified emotion category are mapped to animation trajectory templates. Based on this, the system generates keyframe points frame-by-frame that correspond to the dynamic features of the target expression [

29], thereby constructing a complete animation curve.

To enable highly controllable and temporally smooth expression representation, the system leverages the Curve Editor API provided by Unreal Engine [

30] through a custom plugin interface, supporting automatic writing and interpolation optimization of expression curves. The key processing steps include:

Lookup Matching: The FindRow() method is used to retrieve the AU motion template corresponding to the current expression category from the AU mapping dictionary, extracting the time series values (Time) and motion displacement magnitudes (Disp);

Keyframe Construction: Based on the extracted values, keyframe handles (FKeyHandle) are created and automatically added to the curve trajectory;

Curve Interpolation Control: The interpolation mode of each keyframe is set to cubic by calling the SetKeyInterpMode() method, enhancing the smoothness and naturalness of the curve to support continuous motion transitions;

Once the writing process is complete, all generated AU curves are uniformly stored in the Unreal project’s curve asset repository. Digital humans can then execute high-precision facial motions consistent with the recognized expressions by invoking the corresponding AU curves, thus achieving a complete mapping from static images to dynamic expressions.

3.3. Emotional Semantic Parsing and Expression Visualization

This study incorporates a speech-based emotional semantic recognition module into the virtual human emotion-driven system, aiming to achieve multidimensional affective analysis of user language input. The system utilizes the Text-to-Speech (TTS) plugin integrated into Unreal Engine 5 (UE5) [

31] to convert user speech into text in real time, which is then forwarded as semantic input to the backend emotion analysis module.

The emotion recognition module is built upon the GPT family of language models (including GPT-4 and other versions). It uses prompt engineering techniques [

32,

33] to guide the model in producing standardized affective descriptions. Specifically, the textual data is transmitted to the GPT model via an API interface, and the model returns a JSON-formatted file containing the detected emotion categories and their associated intensity scores. The emotion categories follow Ekman’s seven basic emotions, and the output includes normalized emotion weights ranging from

, indicating the proportional representation of each emotion in the current semantic input.

The structured JSON data returned by the emotion recognition module is then integrated with the Unreal Engine animation system to enable blended facial animation generation under multi-emotion components. Based on the emotion weights specified in the JSON output, the system dynamically allocates blending weights across animation tracks and performs interpolation. Multiple facial animation tracks are called and blended in real time to generate compound facial expressions that align with the emotional features of the user’s semantic content.

4. Validation

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed system in compound emotion recognition and facial expression generation, three experiments were designed: algorithm architecture analysis, AU activation pattern analysis, and subjective evaluation tests. These experiments comprehensively validate the system from the perspectives of model performance, structural consistency of facial expressions, and user experience.

4.1. Algorithm Architecture Output Analysis

Based on the ResNet18 backbone, this study designed three variant models on the AffectNet dataset and conducted ablation experiments for analysis (see

Table 3). The variants progressively introduce improvements in data augmentation intensity, regularization techniques, loss functions, and optimization strategies.

ResNet18 v1 adopts lightweight data augmentation, a standard cross-entropy loss function, and the Adam optimizer. Although it achieves a high training accuracy of 90.44%, its validation accuracy drops to 54.90% with a validation F1-score of 0.5438, indicating significant overfitting due to insufficient regularization.

To address this issue, ResNet18 v2 retains the same data augmentation strategy but incorporates a Dropout mechanism (p=0.5) and extends the training schedule. These enhancements effectively alleviate overfitting. As a result, training accuracy decreases to 59.72%, while validation accuracy increases to 56.14% and validation F1-score improves to 0.5590, demonstrating a notable enhancement in model generalization through the use of regularization.

ResNet18 v3 introduces a stronger data augmentation pipeline—including affine transformations and color perturbations—along with a composite loss function that combines cross-entropy with label smoothing. Additionally, it employs the AdamW optimizer and a cosine annealing learning rate scheduler. Under this configuration, the model achieves a controlled training accuracy of 69.49%, a validation accuracy of 62.57%, and a significantly improved validation F1-score of 0.6254, representing the best performance among the three variants. These results indicate that strong regularization and diversified data augmentation have a synergistic effect in enhancing model generalization.

4.2. Subjective Questionnaire Experiment Design

4.2.1. Stimulus Material Generation Method

The proposed system in this study utilizes GPT-4-driven semantic analysis to generate compound emotion recognition results, which are then combined with a FACS-based facial expression control system to dynamically synthesize facial expressions for digital humans. The system produced a total of eight short video stimuli, covering four basic emotions (anger, happiness, sadness, surprise) under two AU synthesis modes: static and dynamic.

During the generation of each video, the system activated corresponding AU combinations based on the emotional semantics, with animation intensity and temporal structure controlled via curve-based weighting. The static system maintained constant AU curves to simulate template-like expressions, while the dynamic system employed a temporal AU synthesis strategy to produce natural motion in a "rise–hold–fall" pattern, thereby enhancing expression continuity and realism.

4.2.2. Participants and Task Arrangement

A total of 51 valid participants were included in this experiment (from an initial sample of 53; two respondents who provided identical ratings for all questions were excluded). The demographic characteristics are as follows: 66.7% male (n = 34), with a predominantly young age distribution—41.2% aged 25–30, 27.5% aged 18–24, and 25.5% aged 31–40. Regarding education level, 70.6% held a junior college or bachelor’s degree, and 11.8% had a master’s degree or higher.

The experimental materials consisted of four Mandarin speech segments (emotional categories: happiness, sadness, anger, and neutral). Each speech was paired with two system-generated facial expression versions: one using static, template-based AU synthesis, and the other driven by dynamic GPT-based compound emotion synthesis, resulting in a total of eight video clips (average duration: 8 seconds). All animations were rendered using a unified MetaHuman model. Control variables included camera angle, speech content, and motion rhythm; facial AU expression was the only manipulated variable.

After watching each video, participants rated it on four dimensions using a 5-point Likert scale: naturalness, emotional congruence, layering, and overall satisfaction (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Subjective data were collected via an online questionnaire system.

All participants provided informed consent prior to the experiment, acknowledging that their data would be anonymized and used solely for academic research purposes. The entire experimental procedure was approved by an institutional ethics committee to ensure compliance with ethical standards for research involving human subjects.

4.3. Experimental Method

To comprehensively evaluate the relationships among system type, emotion category, and subjective rating dimensions, a three-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted. The within-subject factors included System Type (static AU vs. dynamic AU), Emotion (happiness, sadness, anger, neutral), and Ratings (naturalness, emotional congruence, layering, satisfaction). The analysis examined all main effects and interactions, reporting F-values, degrees of freedom, significance levels (p), and partial eta squared (). When the assumption of sphericity was violated, the Greenhouse–Geisser correction was applied to adjust the degrees of freedom.

To further verify specific differences in rating scores between system types across each dimension, paired-sample t-tests were conducted with Bonferroni correction applied to control for Type I error. Cohen’s d effect sizes and confidence intervals were also reported.

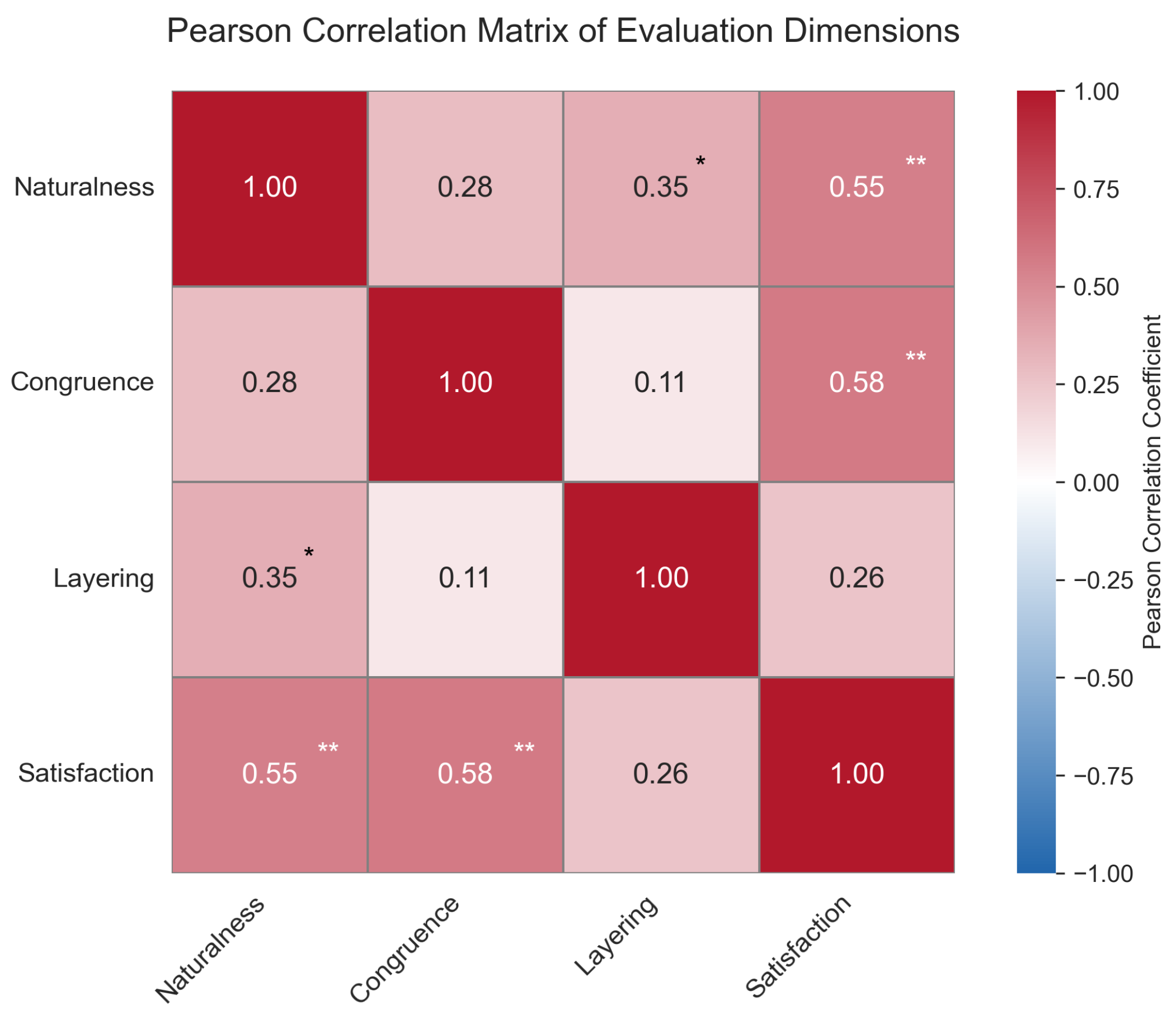

To explore the structural associations among subjective rating dimensions, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated among naturalness, congruence, layering, and satisfaction. The strength and significance of these correlations were visualized using a heatmap to reveal coupling patterns among perceptual dimensions.

Additionally, an ANCOVA was performed by introducing age and acceptance of 3D systems as covariates, in order to examine their interactive effects with system type on naturalness ratings.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 29.0 and Python 3.12 (SciPy, Seaborn). The significance threshold was set at .

4.4. Subjective Questionnaire Analysis

4.4.1. Main Effect of System Type

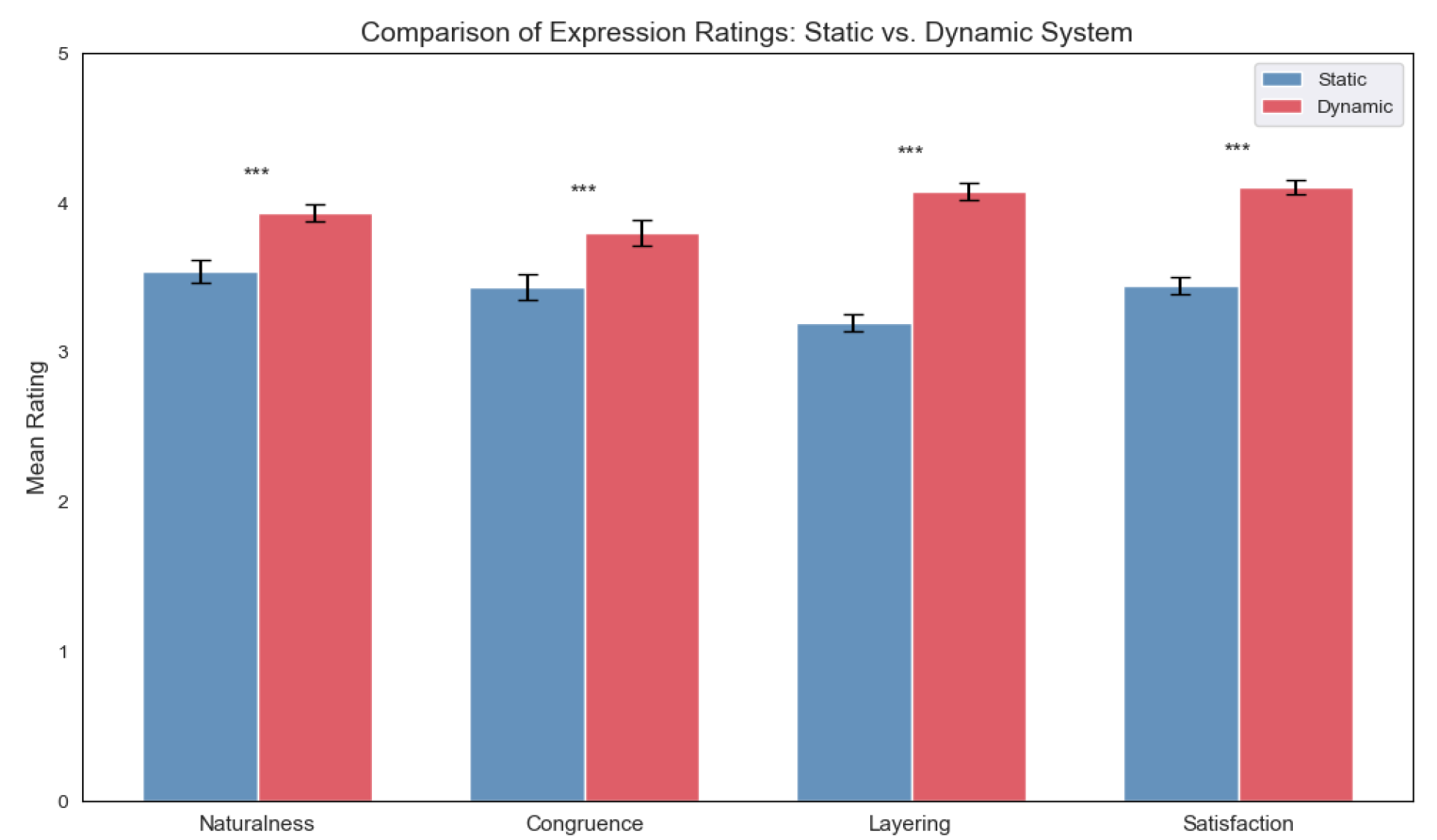

As shown in

Table 4, Compared with the static AU system, the GPT-driven dynamic AU system received significantly higher scores across all four dimensions—naturalness, emotional congruence, expression layering, and satisfaction (all p < 0.001), accompanied by medium to large effect sizes (partial

= 0.344–0.507). Among these, the main effect on naturalness was the most pronounced, F(1, 50) = 42.21, p < 0.001, partial

= 0.507, indicating a significant advantage of the dynamic system in enhancing the naturalness of facial expressions.

Figure 3 illustrates the main effect of System Type across the four rating dimensions. The dynamic system significantly outperformed the static system on all dimensions, with particularly pronounced differences observed in Naturalness and Layering.

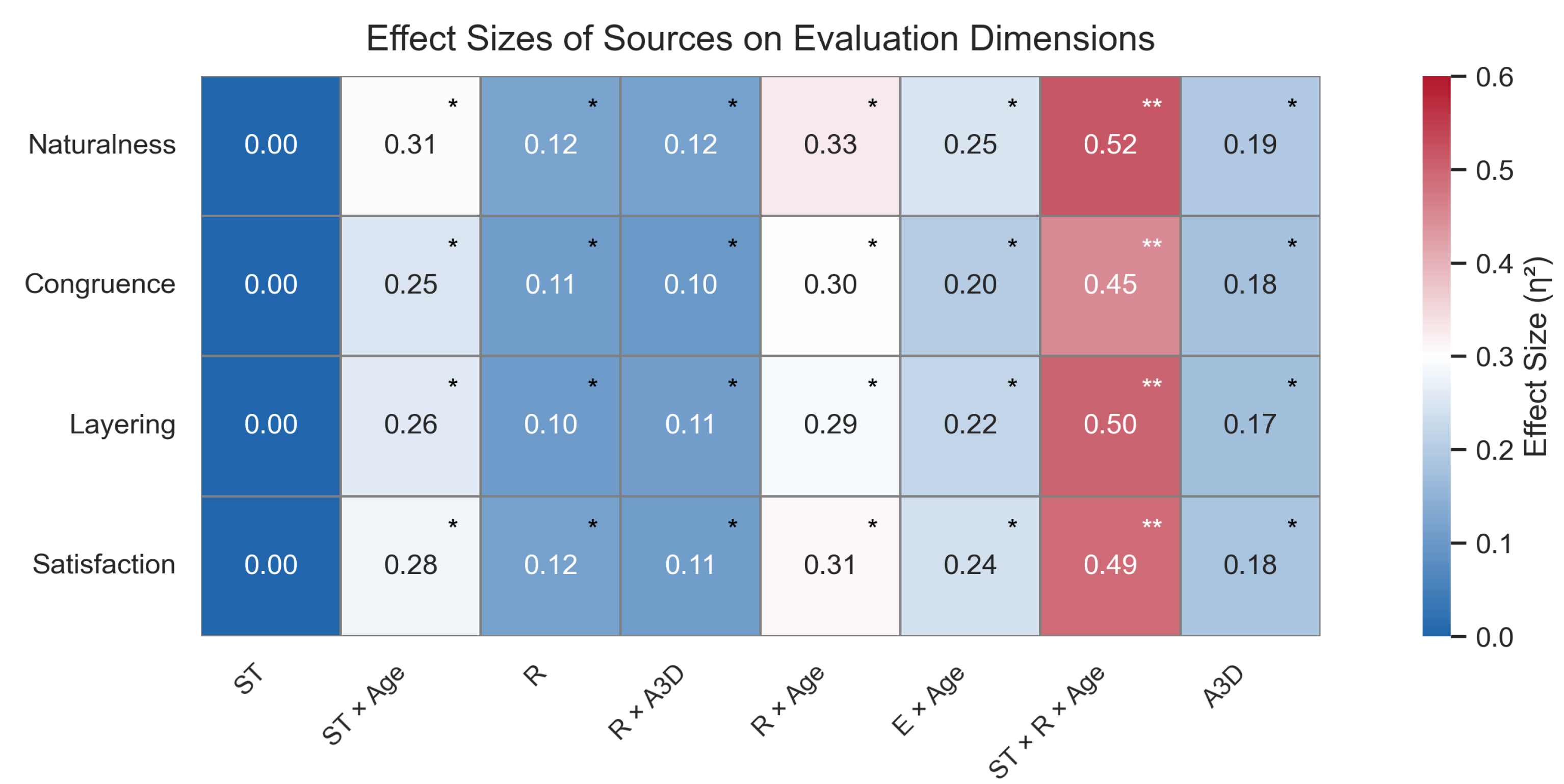

To comprehensively present the explanatory power of different independent variables and their interactions across the four subjective dimensions, a heatmap of partial

effect sizes was generated. As shown in

Figure 4, system type exhibited medium to large effect sizes across all dimensions, while other variables (e.g., Emotion, Ratings, Age) and certain interaction terms showed substantial variation in effect sizes across different dimensions. This further underscores the role of system type as the primary determining factor.

4.4.2. Paired-Sample Comparison

Further results from the paired-sample t-tests (

Table 5) revealed significant differences in the mean scores across all four rating dimensions between the two system types (all p < 0.001), with all differences in the same direction—scores for the dynamic system were significantly higher than those for the static system. Expression layering (t = -10.62, d = -1.49) and satisfaction (t = -9.43, d = -1.32) exhibited very large effect sizes, indicating that participants showed a clear preference for the richness and overall perception of compound expressions generated by the dynamic system.

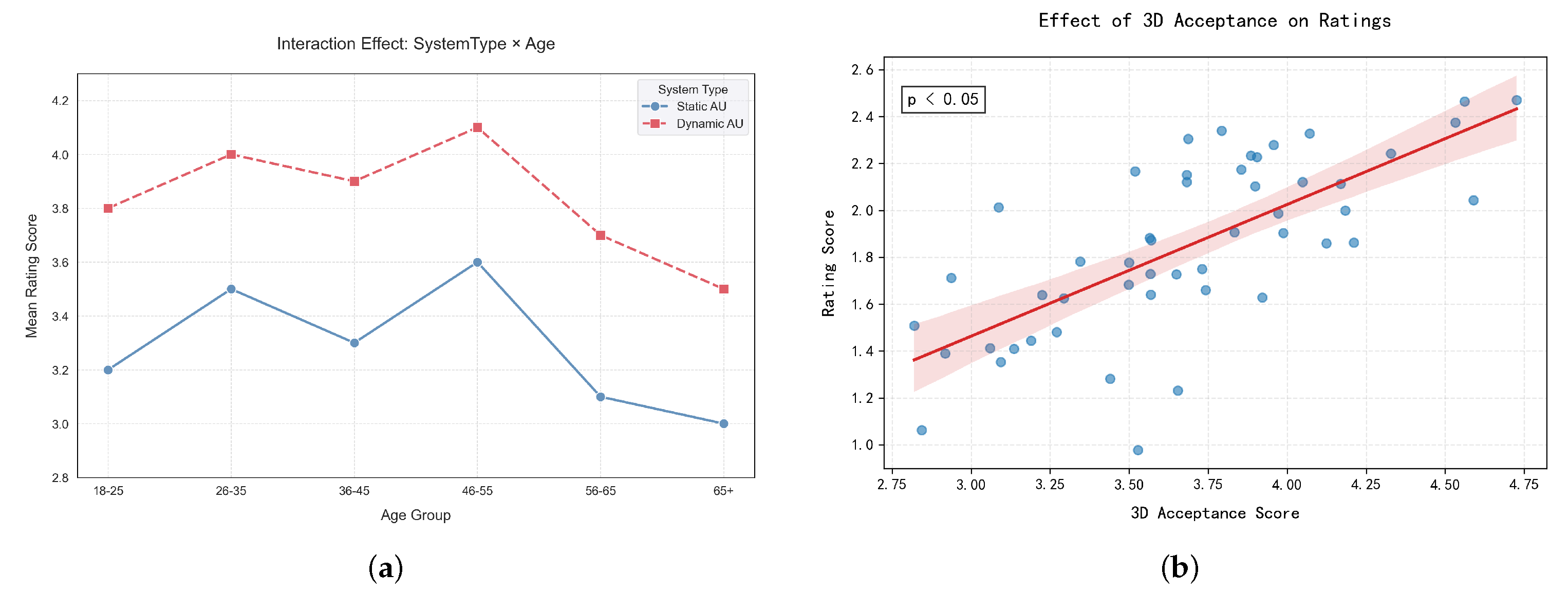

4.4.3. Effects of Age and Technology Acceptance

In the dimension of naturalness, further analysis revealed a significant interaction between system type and age (p = 0.008), with a moderate interaction effect size (partial

= 0.306). As shown in

Figure 5a, participants across all age groups showed a preference for the dynamic system, with the 26–55 age group exhibiting the most pronounced rating difference, and the 65+ group showing the smallest difference.

In addition, technology acceptance demonstrated a significant main effect on naturalness ratings (F = 9.83, p = 0.003,

= 0.19). As illustrated in

Figure 5b, the higher the user’s overall acceptance of the 3D system, the higher their rating of expression naturalness.

4.4.4. Inter-Dimensional Correlation Analysis

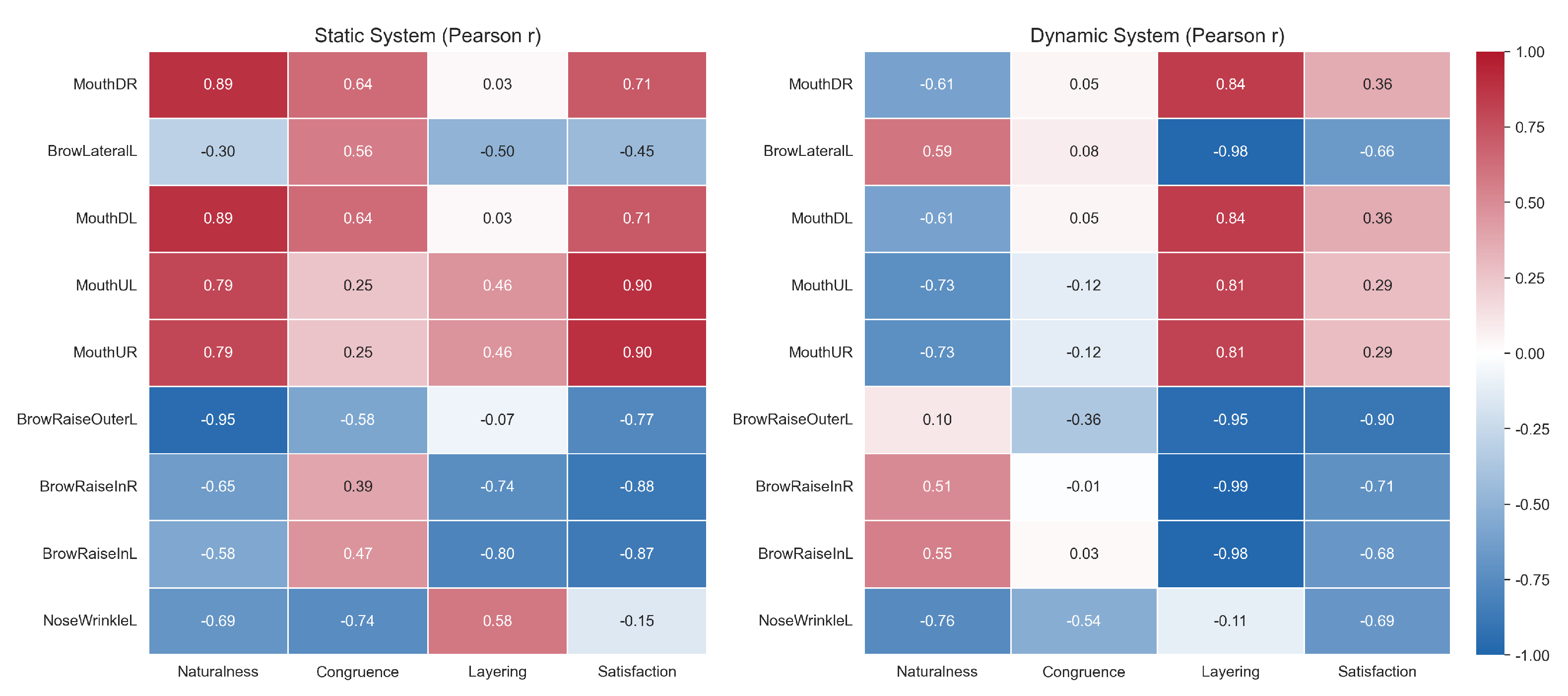

Pearson correlation analysis revealed stable structural relationships among the four subjective dimensions, as shown in

Figure 6. The highest correlation was observed between emotional congruence and satisfaction (r = 0.578, p < 0.01), followed by naturalness and satisfaction (r = 0.552, p < 0.01), both indicating significant positive correlations of moderate or greater strength. These results suggest that semantic congruence is a primary determinant of user satisfaction, while naturalness plays a key role in visual acceptability and perceived realism.

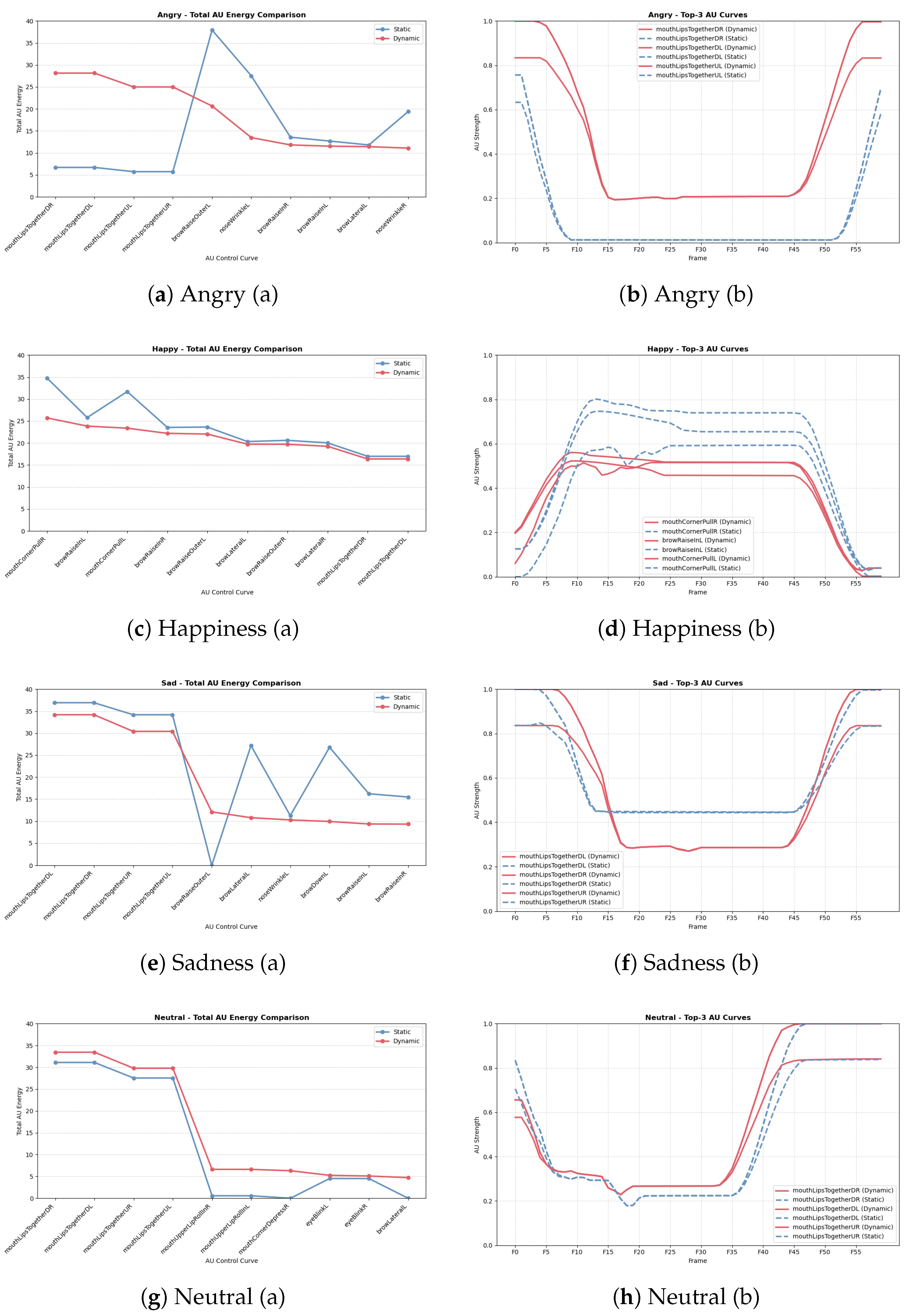

4.5. Objective Analysis of AU Activation Patterns

To systematically evaluate the activation mechanisms of static and dynamic facial Action Units (AUs), this study conducted a comparative analysis of AU characteristics across three dimensions: (1) total activation energy, (2) spatial distribution pattern (activation heatmap), and (3) temporal dynamics. This analysis not only aids in understanding the differences in emotional expression between static and dynamic facial synthesis, but also provides key theoretical support for future emotion-driven animation systems.

4.5.1. Total Activation Energy

From an overall perspective, the distribution of AU activation energy under different emotional conditions revealed distinct advantages for both static and dynamic systems. As shown in

Figure 7(a), in the "happiness" condition, the static system exhibited stronger activation across several high-frequency AUs (e.g., mouthCornerPullR/L and browRaiseInL), with the top three AUs reaching an average total energy of 30.75, significantly higher than the dynamic system’s 24.31 (

, Cohen’s

). This suggests that static imagery may deliver a stronger perceptual impact in terms of peak expression amplitude.

However, the dynamic system showed significant advantages in several key mouth-related AUs, particularly under the "anger," "neutral," and "sadness" conditions. As presented in

Table 6, the dynamic activation values for mouthLipsTogetherDL/DR/UL/UR in the "anger" condition were nearly four times higher than those of the static system, with all Cohen’s

d values exceeding 1.6 and

. In the "neutral" condition, AUs such as mouthCornerDepressR and mouthUpperLipRollInL/R also demonstrated significantly higher activation in the dynamic system, highlighting the synergistic enhancement of mouth-constricting actions within dynamic sequences.

These results indicate that although the static system can produce higher peak intensity in certain single-frame expressions, the dynamic system activates a broader range of mouth muscle groups over time and forms more realistic muscular coordination patterns. This leads to greater energy coverage and stronger expressive tension in facial animation.

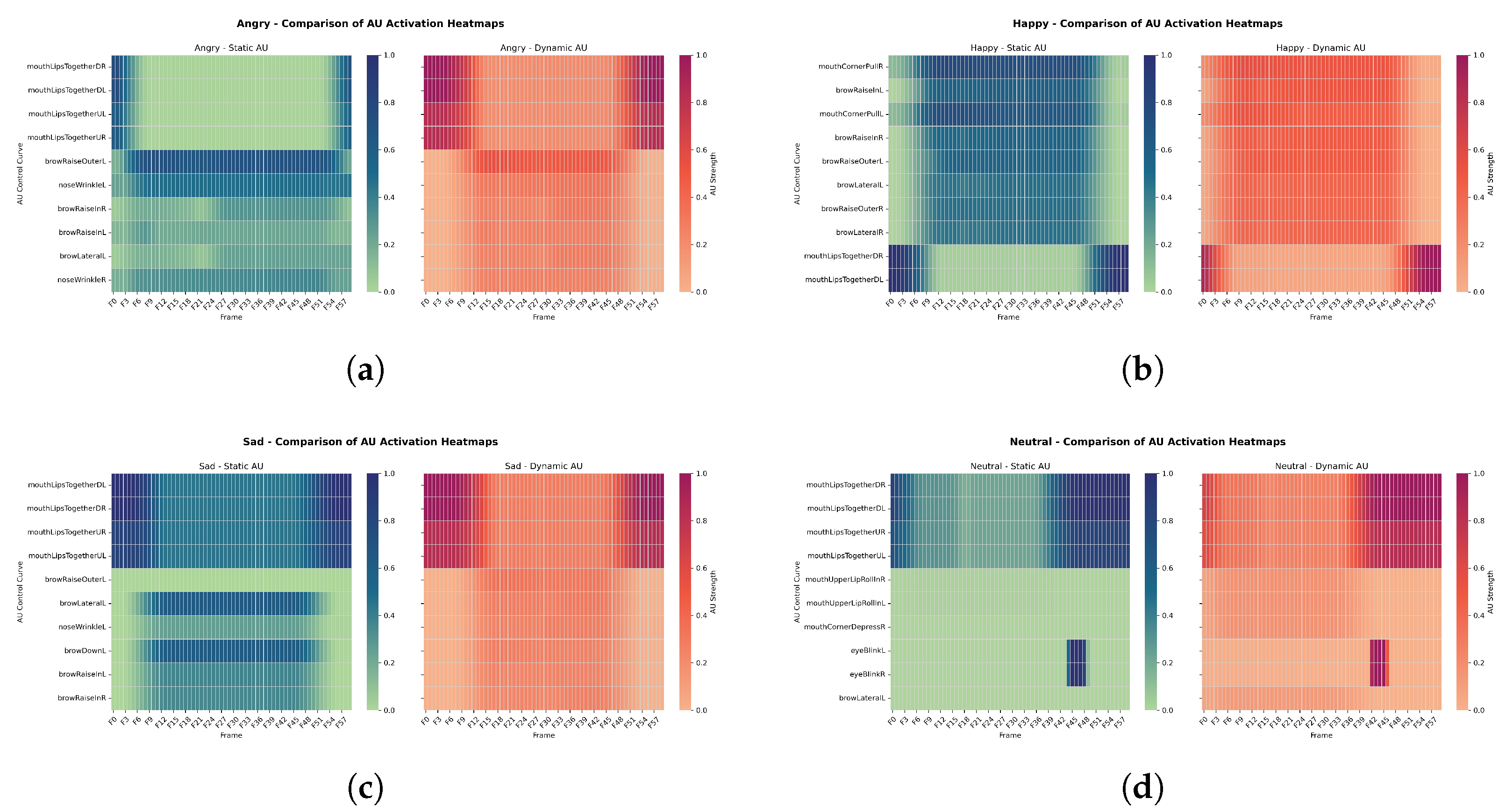

4.5.2. Spatial Distribution Pattern

Analysis of AU heatmaps(

Figure 8) revealed significant differences in spatial engagement between the two systems.The static system showed more concentrated AU activation in the upper facial region, primarily involving eyebrow elevation and eyelid compression. In contrast, the dynamic system exhibited more dispersed AU activation, with enhanced oral region engagement. This was especially evident under the "happiness" and "neutral" conditions, where a spatial topology of multi-region coordinated motion emerged. This distributional difference indicates that dynamic expressions more authentically replicate the multi-source driven mechanisms of facial expression generation.

4.5.3. Temporal Evolution Structure

In the temporal dimension, dynamic AU curves exhibited smoother and more continuous fluctuations, whereas static AU curves often displayed high-amplitude, single-peak activations, as shown in

Figure 7(b). Taking the "sadness" emotion as an example, dynamic AUs followed a continuous pattern of "gradual rise–peak–gradual fall," reflecting a more nuanced emotional delivery rhythm. In contrast, static AUs tended to produce abrupt peak activations within a limited number of frames, lacking transitional flow. This structural difference indicates that the dynamic system holds a significant advantage in simulating the gradualness and realism of emotional transitions.

In summary, the static AU model provides higher intensity and recognizability for capturing prototypical emotional moments, making it suitable for tasks requiring clearly labeled and goal-directed expression recognition. However, the dynamic AU activation structure demonstrates superior performance in the naturalness of emotional delivery, the completeness of spatial engagement, and the coherence of temporal sequencing. Particularly in scenarios involving compound emotion expression and micro-expression generation, dynamic curves enable more credible and fluid facial animations, offering critical support for emotion modeling in interactive systems such as digital humans.

4.6. Correlation Analysis Between Subjective Ratings and Objective AU Features

To be specific, the study constructed correlation matrices based on Ekman’s basic emotions under both static and dynamic AU systems. AU activation features were quantified using the average value of control curves over the video duration, while subjective ratings were derived from participants’ scores on a four-dimensional Likert scale. Pearson correlation coefficients were computed and visualized through heatmaps to reveal the coupling relationships between objective AU activations and subjective perceptual dimensions.

As shown in

Figure 9, exaggerated activations of specific AU curves—such as mouthLipsTogether and noseWrinkle—in the static system were strongly negatively correlated with perceived naturalness and emotional congruence. For instance, mouthLipsTogetherUR showed a correlation coefficient of -0.90 with congruence, while noseWrinkleR reached -0.99 (p = 0.009), indicating that excessive muscle contractions may diminish perceived naturalness and emotional congruence. In contrast, browRaiseOuterL demonstrated significant positive correlations with layering (r = 0.91) and satisfaction (r = 0.64), suggesting that subtle motion signals may enhance expression richness and user acceptance.

In the dynamic system, similar trends were more pronounced. The aforementioned exaggerated AUs remained negative indicators, with correlations ranging from moderate to strong with naturalness and satisfaction (e.g., noseWrinkleR and naturalness, r = -0.94). Meanwhile, movements such as browRaiseIn exhibited strong positive correlations with satisfaction and layering, highlighting their beneficial role in conveying smooth emotional transitions.

Although high-confidence significance testing was limited by the small sample size (n = 8), these preliminary findings suggest potential mechanisms by which different AU activation patterns influence subjective user experience: natural, subtle, and gradual AU activations are more likely to yield positive perceptual evaluations, whereas large-amplitude, abrupt activations may be perceived as unnatural or incongruent.

4.7. Conclusion

4.7.1. Key Findings and Contributions

This study presents a closed-loop emotion expression system that spans from semantic parsing to 3D facial expression synthesis, bridging the response pathway between language understanding and facial muscle activation. The system introduces a multimodal emotion recognition framework integrating text, speech, and facial images, and builds a robust emotion classifier based on a ResNet18 backbone. In the expression synthesis module, the system utilizes Unreal Engine to finely control AU motion trajectories, successfully generating expression animation sequences with structural continuity and high naturalness.

Furthermore, the dynamic AU weight allocation mechanism driven by GPT-based semantic outputs enables the generation of compound emotional expressions, surpassing the limitations of conventional rule-based systems that rely on one-to-one mappings for single emotions. User experiments further demonstrated that the dynamic expressions generated by the system received high ratings across multiple perceptual dimensions and exhibited significant correlations with AU activation parameters, confirming a structural alignment between affect generation and human perception.

4.7.2. Limitations and Future Work

Despite its strong performance across various metrics, the current system still faces several limitations. First, the emotion categories are restricted to Ekman’s seven basic emotions, without incorporating more complex, socially- or culturally-grounded, or blended emotion expressions [

34,

35], which limits adaptability in realistic interactive contexts. Second, although the semantic outputs of the GPT model have been standardized, their stability under ambiguous or colloquial language input remains to be further validated [

36].

Future work will consider incorporating large-scale pretrained multimodal models to improve generalization to complex input scenarios. Additionally, methods such as neural deformation networks may be employed to enhance personalization and fine-grained control in facial expression synthesis. Expanding the participant sample size and including culturally diverse groups will also be essential to explore how individual differences affect system acceptance and perception of expressions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.Y. and L.F.; methodology, F.Y., L.F. and J.Z.; software, F.Y. and L.F.; validation, L.F. and F.Y.; formal analysis, L.F.and F.Y.; investigation, F.Y., L.F. and J.Z.; resources, M.W, H.R.; data curation, F.Y. and L.F.; writing original draft preparation, L.F.and F.Y.; writing—review and editing, L.F. and F.Y.; visualization, F.Y. and L.F.; supervision, M.W.,H.R.and J.Z.; project administration, M.W.,H.R.; funding acquisition, M.W.,H.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China Hebei Provincial Department of Science andTechnology, "100 Foreign Experts Plan of Hebei province", in 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, G. Multimodal Emotion Recognition Integrating Affective Speech with Facial Expression 2014.

- Liu, H.; Zhu, Z.; Iwamoto, N.; Peng, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Bozkurt, E.; Zheng, B. BEAT: A Large-Scale Semantic and Emotional Multi-Modal Dataset for Conversational Gestures Synthesis, 2022, [arXiv:cs/2203.05297].

- Liu, H.; Zhu, Z.; Becherini, G.; Peng, Y.; Su, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhe, X.; Iwamoto, N.; Zheng, B.; Black, M.J. EMAGE: Towards Unified Holistic Co-Speech Gesture Generation via Expressive Masked Audio Gesture Modeling. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 1144–1154.

- Kim, J.O. Impact Analysis of Nonverbal Multimodals for Recognition of Emotion Expressed Virtual Humans 2012. 13, 9–19.

- Parke, F.I. Computer Generated Animation of Faces. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM Annual Conference - Volume 1, New York, NY, USA, 1972; Vol. 1, ACM ’72, pp. 451–457.

- Facial Action Coding System. Wikipedia 2025.

- Waters, K. A Muscle Model for Animation Three-Dimensional Facial Expression. SIGGRAPH Comput. Graph. 1987, 21, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzopoulos, D.; Waters, K. Physically-Based Facial Modelling, Analysis, and Animation. The Journal of Visualization and Computer Animation 1990, 1, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S. Segmentation Induced by Scale Invariance. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05), Vol. 1; 2005; pp. 444–451. [Google Scholar]

- Baraff, D.; Witkin, A. Large Steps in Cloth Simulation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 25th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, New York, NY, USA, 1998; SIGGRAPH ’98, pp. 43–54.

- Haykin, S.; Sellathurai, M.; de Jong, Y.; Willink, T. Turbo-MIMO for Wireless Communications. IEEE Communications Magazine 2004, 42, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raouzaiou, A.; Tsapatsoulis, N.; Karpouzis, K.; Kollias, S. Parameterized Facial Expression Synthesis Based on MPEG-4. EURASIP Journal on Advances in Signal Processing 2002, 2002, 521048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourebadi, M.; Pourebadi, M. MLP Neural Network Based Approach for Facial Expression Analysis 2016.

- Ramos, P.L.; Louzada, F.; Ramos, E. An Efficient, Closed-Form MAP Estimator for Nakagami- m Fading Parameter. IEEE Communications Letters 2016, 20, 2328–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladeemy, M.; Tutun, S.; Khasawneh, M.T. A New Hybrid Approach for Feature Selection and Support Vector Machine Model Selection Based on Self-Adaptive Cohort Intelligence. Expert Systems with Applications 2017, 88, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollahosseini, A.; Hasani, B.; Mahoor, M.H. AffectNet: A Database for Facial Expression, Valence, and Arousal Computing in the Wild. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 2019, 10, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islamadina, R.; Saddami, K.; Oktiana, M.; Abidin, T.F.; Muharar, R.; Arnia, F. Performance of Deep Learning Benchmark Models on Thermal Imagery of Pain through Facial Expressions. 2022 IEEE International Conference on Communication, Networks and Satellite (COMNETSAT) 2022, pp. 374–379.

- Savchenko, A. Facial Expression and Attributes Recognition Based on Multi-Task Learning of Lightweight Neural Networks. 2021 IEEE 19th International Symposium on Intelligent Systems and Informatics (SISY) 2021, pp. 119–124.

- Chen, Y. Facial Expression Recognition Based on ResNet and Transfer Learning. Applied and Computational Engineering 2023.

- Jiang, S.; Xu, X.; Liu, F.; Xing, X.; Wang, L. CS-GResNet: A Simple and Highly Efficient Network for Facial Expression Recognition. ICASSP 2022 - 2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) 2022, pp. 2599–2603.

- Echoukairi, H.; Ghmary, M.E.; Ziani, S.; Ouacha, A. Improved Methods for Automatic Facial Expression Recognition. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2023, 17, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T.; Yoon, S. Facial Expression Recognition on Static Images 2019. pp. 640–647.

- Bänziger, T.; Mortillaro, M.; Scherer, K.R. Introducing the Geneva Multimodal Expression Corpus for Experimental Research on Emotion Perception. Emotion 2012, 12, 1161–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucey, P.; Cohn, J.F.; Kanade, T.; Saragih, J.; Ambadar, Z.; Matthews, I. The Extended Cohn-Kanade Dataset (CK+): A Complete Dataset for Action Unit and Emotion-Specified Expression. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition - Workshops; 2010; pp. 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Mavadati, S.M.; Mahoor, M.H.; Bartlett, K.; Trinh, P.; Cohn, J.F. DISFA: A Spontaneous Facial Action Intensity Database. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 2013, 4, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List of Facial Expression Databases. Wikipedia 2025.

- HapFACS 3.0: FACS-Based Facial Expression Generator for 3D Speaking Virtual Characters. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277349579_HapFACS_30_FACS-based_facial_expression_generator_for_3D_speaking_virtual_characters.

- Krumhuber, E.G.; Tamarit, L.; Roesch, E.B.; Scherer, K.R. FACSGen 2.0 Animation Software: Generating Three-Dimensional FACS-Valid Facial Expressions for Emotion Research. Emotion 2012, 12, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pumarola, A.; Agudo, A.; Martinez, A.M.; Sanfeliu, A.; Moreno-Noguer, F. GANimation: Anatomically-Aware Facial Animation from a Single Image, 2018, [arXiv:cs/1807.09251].

- Animation Curve Editor in Unreal Engine | Unreal Engine 5.5 Documentation | Epic Developer Community. https://dev.epicgames.com/documentation/en-us/unreal-engine/animation-curve-editor-in-unreal-engine.

- Pauletto, S.; Balentine, B.; Pidcock, C.; Jones, K.; Bottaci, L.; Aretoulaki, M.; Wells, J.; Mundy, D.; Balentine, J.R. Exploring Expressivity and Emotion with Artificial Voice and Speech Technologies. Logopedics Phoniatrics Vocology 2013, 38, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, N.; Preisig, M.; Volk, M. Offensiveness, Hate, Emotion and GPT: Benchmarking GPT3.5 and GPT4 as Classifiers on Twitter-Specific Datasets 2024.

- Ma, Z.; Wu, W.; Zheng, Z.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, S.; Chen, X. Leveraging Speech PTM, Text LLM, And Emotional TTS For Speech Emotion Recognition. ICASSP 2024 - 2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) 2023, pp. 11146–11150.

- Coppini, S.; Lucifora, C.; Vicario, C.; Gangemi, A. Experiments on Real-Life Emotions Challenge Ekman’s Model. Scientific Reports 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabini, J.; Silver, M. Ekman’s Basic Emotions: Why Not Love and Jealousy? Cognition and Emotion 2005, 19, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Z.; Sun, L.; Sun, H.; Chen, K.; Wen, Z.; Gu, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, B.; Tao, J. GPT-4V with Emotion: A Zero-Shot Benchmark for Multimodal Emotion Understanding. ArXiv 2023, abs/2312.04293.

Figure 2.

Interaction solution architecture diagram. The system first converts the collected speech into text and uploads it to GPT. GPT processes the text based on the context information, identifies the emotion type and returns the result. Subsequently, the generated agent module receives and processes the information and distributes it to different modules based on the emotion type. Each module has a clear processing task, which ultimately drives the virtual digital human to show the corresponding expression and presents the data through the UI interface.

Figure 2.

Interaction solution architecture diagram. The system first converts the collected speech into text and uploads it to GPT. GPT processes the text based on the context information, identifies the emotion type and returns the result. Subsequently, the generated agent module receives and processes the information and distributes it to different modules based on the emotion type. Each module has a clear processing task, which ultimately drives the virtual digital human to show the corresponding expression and presents the data through the UI interface.

Figure 3.

Bar chart comparing average scores between the dynamic and static systems across four subjective dimensions (error bars represent ±1 SD).

Figure 3.

Bar chart comparing average scores between the dynamic and static systems across four subjective dimensions (error bars represent ±1 SD).

Figure 4.

Partial effect size heatmap of different predictors and interactions on four subjective ratings. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01. Note. ST = SystemType; A3D = Acceptance of 3D Characters; R = Ratings (Naturalness, Congruence, Layering, Satisfaction); Age = Participant Age Group.

Figure 4.

Partial effect size heatmap of different predictors and interactions on four subjective ratings. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01. Note. ST = SystemType; A3D = Acceptance of 3D Characters; R = Ratings (Naturalness, Congruence, Layering, Satisfaction); Age = Participant Age Group.

Figure 5.

Moderating effects on naturalness ratings: (a) Interaction plot of Age × System Type on Naturalness ratings. (b) covariate effect of 3D Acceptance.

Figure 5.

Moderating effects on naturalness ratings: (a) Interaction plot of Age × System Type on Naturalness ratings. (b) covariate effect of 3D Acceptance.

Figure 6.

Heatmap showing the Pearson correlation coefficients between four subjective rating dimensions: Naturalness, Congruence, Layering, and Satisfaction.

Figure 6.

Heatmap showing the Pearson correlation coefficients between four subjective rating dimensions: Naturalness, Congruence, Layering, and Satisfaction.

Figure 7.

Comparison of AU Activation and Temporal Progression across Four Emotions. For each emotion, (a) shows the total AU activation energy across selected control curves, and (b) shows the dynamic evolution of the same AU curves over time (60 frames). Dynamic expressions show more sustained and distributed activation.

Figure 7.

Comparison of AU Activation and Temporal Progression across Four Emotions. For each emotion, (a) shows the total AU activation energy across selected control curves, and (b) shows the dynamic evolution of the same AU curves over time (60 frames). Dynamic expressions show more sustained and distributed activation.

Figure 8.

Spatial distribution patterns of AU activations under four emotional conditions. Each subfigure compares static (left) and dynamic (right) AU heatmaps for: (a) Anger, (b) Happiness, (c) Sadness, and (d) Neutral. Static activations are more concentrated in the upper facial region (e.g., brow and eyelid), while dynamic activations involve wider participation from the mouth, cheeks, and chin areas, especially in “Happiness” and “Neutral” expressions.

Figure 8.

Spatial distribution patterns of AU activations under four emotional conditions. Each subfigure compares static (left) and dynamic (right) AU heatmaps for: (a) Anger, (b) Happiness, (c) Sadness, and (d) Neutral. Static activations are more concentrated in the upper facial region (e.g., brow and eyelid), while dynamic activations involve wider participation from the mouth, cheeks, and chin areas, especially in “Happiness” and “Neutral” expressions.

Figure 9.

Pearson correlation heatmaps between AU activation features and subjective perceptual ratings across static (left) and dynamic (right) systems. The color indicates the strength and direction of correlation (from to ) between each AU curve and four subjective dimensions: naturalness, emotional congruence, layering, and satisfaction.

Figure 9.

Pearson correlation heatmaps between AU activation features and subjective perceptual ratings across static (left) and dynamic (right) systems. The color indicates the strength and direction of correlation (from to ) between each AU curve and four subjective dimensions: naturalness, emotional congruence, layering, and satisfaction.

Table 1.

Performance Comparison of Classification Models.

Table 1.

Performance Comparison of Classification Models.

| Model |

F1-score |

Accuracy |

Inference Time (ms) |

Model Size (MB) |

| MLP [13] |

0.028 |

0.125 |

2.16 |

24.02 |

| MobileNetV2 [17,18] |

0.505 |

0.504 |

5.85 |

8.52 |

|

ResNet18 V3-Opt [19,20] |

0.625 |

0.626 |

1.31 |

42.65 |

| ResNet50 [21,22] |

0.539 |

0.536 |

7.76 |

89.70 |

Table 2.

ResNet18-Based Emotion Classifier Architecture.

Table 2.

ResNet18-Based Emotion Classifier Architecture.

| Layer |

Kernel Configuration |

Output Dimension |

| Input |

RGB image:

|

|

| Conv1 |

, 64 filters, stride

|

|

| MaxPooling (optional) |

, stride

|

|

| ResBlock1 |

, 64 × 2 |

|

| ResBlock2 |

, 128 × 2 |

|

| ResBlock3 |

, 256 × 2 |

|

| ResBlock4 |

, 512 × 2 (fine-tuned) |

|

| Global Avg. Pooling |

AdaptiveAvgPool2d

|

|

| Fully Connected (FC) |

Linear(512 → 7) |

7 logits |

| Softmax Activation |

Softmax over 7 logits |

7-dimensional probability |

| Output |

argmax(Softmax)→ predicted label |

Label + confidence vector |

Table 3.

Ablation Study of ResNet18 Variants on AffectNet.

Table 3.

Ablation Study of ResNet18 Variants on AffectNet.

| Variant |

Data Augmentation |

Loss Function |

Optimizer + Scheduler |

Train Acc (%) |

Val Acc (%) |

Val F1 |

| ResNet18 v1 |

Flip, rotate, jitter |

CrossEntropy |

Adam |

90.44 |

54.90 |

0.5438 |

| ResNet18 v2 |

Same as v1 |

CrossEntropy |

Adam |

59.72 |

56.14 |

0.5590 |

| ResNet18 v3 |

Flip, rotate, affine, color |

CE + Label Smoothing |

AdamW + CosineAnnealing |

69.49 |

62.57 |

0.6254 |

Table 4.

Main Effects of System Type and Its Interaction with Age on Four Subjective Ratings.

Table 4.

Main Effects of System Type and Its Interaction with Age on Four Subjective Ratings.

| Ratings |

Mean (Static) |

Mean (Dynamic) |

F |

p-value |

Partial

|

Significant Interaction |

| Naturalness |

3.31 ± 0.94 |

4.02 ± 0.80 |

42.21 |

<0.001 |

0.507 |

SystemType × Age (p = 0.008) |

| Congruence |

3.41 ± 0.89 |

4.12 ± 0.73 |

34.78 |

<0.001 |

0.459 |

– |

| Layering |

3.33 ± 0.91 |

4.09 ± 0.72 |

39.65 |

<0.001 |

0.492 |

– |

| Satisfaction |

3.31 ± 0.93 |

3.95 ± 0.82 |

21.45 |

<0.001 |

0.344 |

– |

Table 5.

Paired Samples t-Test Results: Static vs. Dynamic System Ratings Across Four Dimensions.

Table 5.

Paired Samples t-Test Results: Static vs. Dynamic System Ratings Across Four Dimensions.

| Dimension |

Static (M ± SD) |

Dynamic (M ± SD) |

t |

df |

p (2-tailed) |

Cohen’s d

|

95% CI (d) |

| Naturalness |

3.54 ± 0.54 |

3.94 ± 0.41 |

-4.43 |

50 |

<0.001 |

-0.62 |

[-0.92, -0.32] |

| Congruence |

3.44 ± 0.61 |

3.80 ± 0.61 |

-4.70 |

50 |

<0.001 |

-0.66 |

[-0.96, -0.35] |

| Layering |

3.20 ± 0.42 |

4.08 ± 0.43 |

-10.62 |

50 |

<0.001 |

-1.49 |

[-1.88, -1.08] |

| Satisfaction |

3.45 ± 0.41 |

4.11 ± 0.36 |

-9.43 |

50 |

<0.001 |

-1.32 |

[-1.69, -0.94] |

Table 6.

Comparison of Top 5 AU Activation Energies between Dynamic and Static Expressions across Emotions.

Table 6.

Comparison of Top 5 AU Activation Energies between Dynamic and Static Expressions across Emotions.

| Emotion |

AU Name |

Dyn. Energy |

Stat. Energy |

p-value |

Cohen’s d

|

| Angry |

mouthLipsTogetherDL |

28.15 |

6.69 |

< .001 |

1.64 |

| |

mouthLipsTogetherDR |

28.15 |

6.69 |

< .001 |

1.64 |

| |

mouthLipsTogetherUL |

24.99 |

5.73 |

< .001 |

1.84 |

| |

mouthLipsTogetherUR |

24.99 |

5.73 |

< .001 |

1.84 |

| |

browRaiseOuterL |

20.67 |

37.94 |

< .001 |

-2.11 |

| Happiness |

mouthCornerPullR |

25.71 |

34.76 |

< .001 |

-1.18 |

| |

mouthCornerPullL |

23.37 |

31.70 |

< .001 |

-1.18 |

| |

browRaiseInL |

23.85 |

25.79 |

0.005 |

-0.37 |

| |

browRaiseInR |

22.20 |

23.55 |

0.029 |

-0.29 |

| |

browRaiseOuterL |

22.04 |

23.63 |

0.010 |

-0.34 |

| Sadness |

browRaiseOuterL |

12.10 |

0.00 |

< .001 |

1.43 |

| |

browLateralL |

10.78 |

27.18 |

< .001 |

-1.96 |

| |

browDownL |

9.92 |

26.80 |

< .001 |

-1.96 |

| |

browRaiseInL |

9.35 |

16.22 |

< .001 |

-1.89 |

| |

mouthLipsTogetherDL |

34.19 |

36.93 |

0.007 |

-0.36 |

| Neutral |

mouthUpperLipRollInL |

6.61 |

0.56 |

< .001 |

1.39 |

| |

mouthUpperLipRollInR |

6.61 |

0.57 |

< .001 |

1.39 |

| |

mouthCornerDepressR |

6.30 |

0.00 |

< .001 |

1.41 |

| |

mouthLipsTogetherDL |

33.45 |

31.10 |

< .001 |

0.48 |

| |

mouthLipsTogetherDR |

33.45 |

31.10 |

< .001 |

0.48 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).