Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Simulation Procedure of BDR Membrane Reactor Using Pd/Cu Membrane and Ni/Cr Catalyst

2.1. A Mathematical Formation

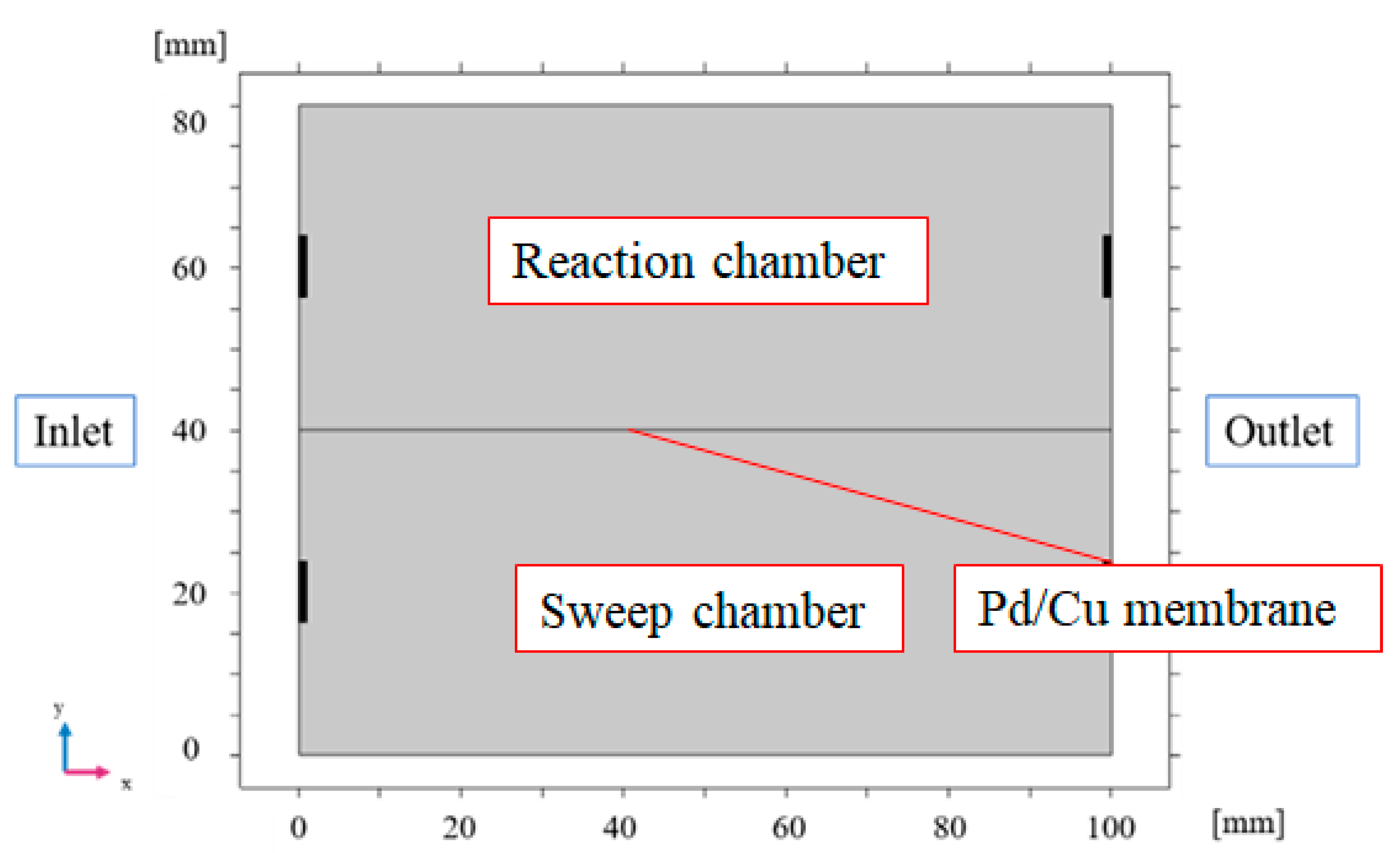

2.2. 2D Numerical Simulation Model of BDR Membrane Reactor

2.3. Kinetic Modeling of BDR

2.4. Numerical Simulation Parameters and Conditions in This Study

- (i)

- Catalyst is a porous material. The porosity, permeability, constant pressure specific heat and thermal conductivity and isotropic.

- (ii)

- Wall temperature is isothermal.

- (iii)

- Gas is a Newton fluid and an ideal gas.

- (iv)

- Wall of reactor excluding inlet and outlet is no-slip.

- (v)

- The pressure of outlet is atmosphere (gauge pressure = 0 Pa).

- (vi)

- The temperature of inflow gas is same as the initial reaction temperature.

- (vii)

- The produced carbon is treated as a gas.

2.5. Evaluation Factor for Reaction Characteristics in This Study

3. Results and Discussion

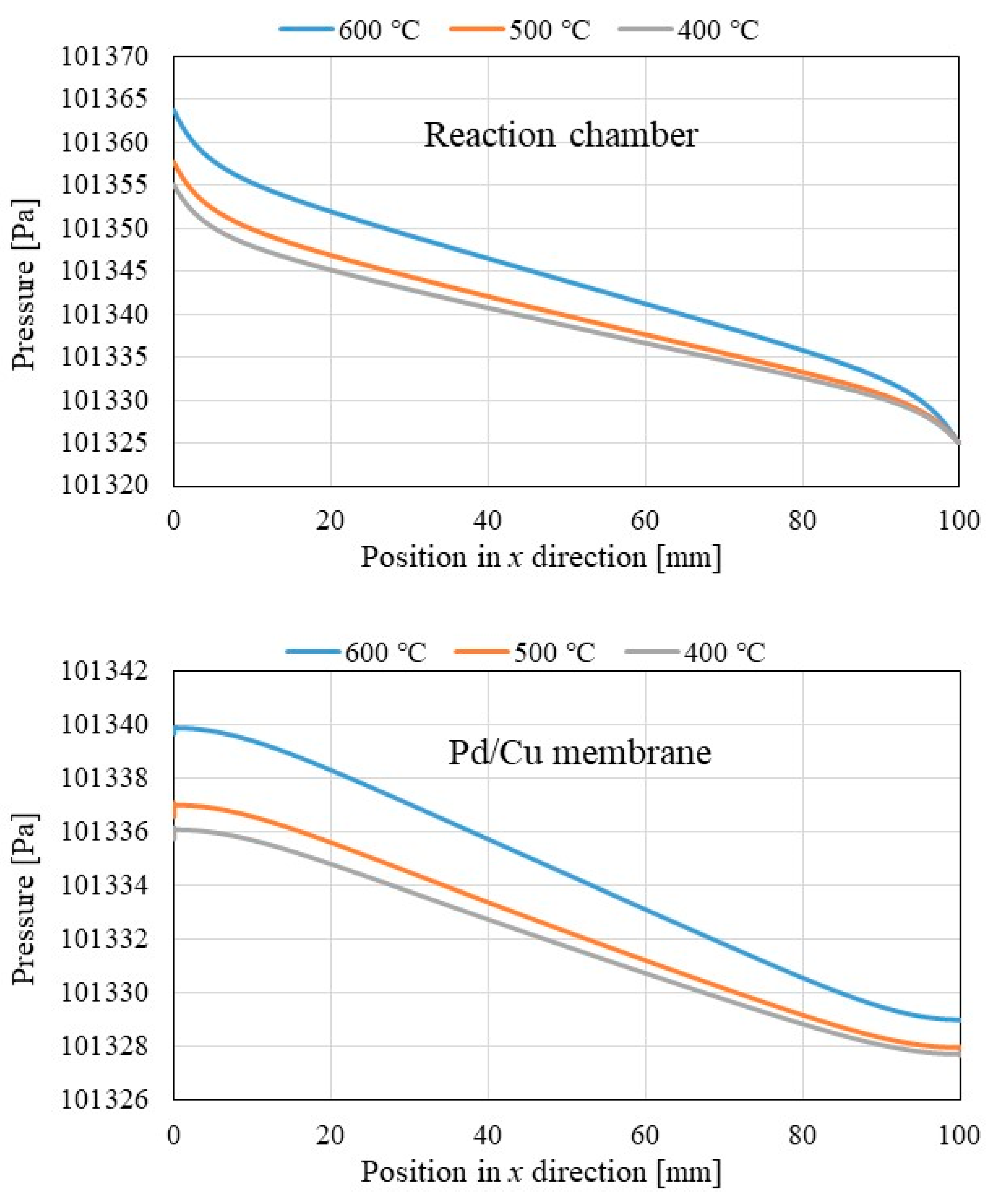

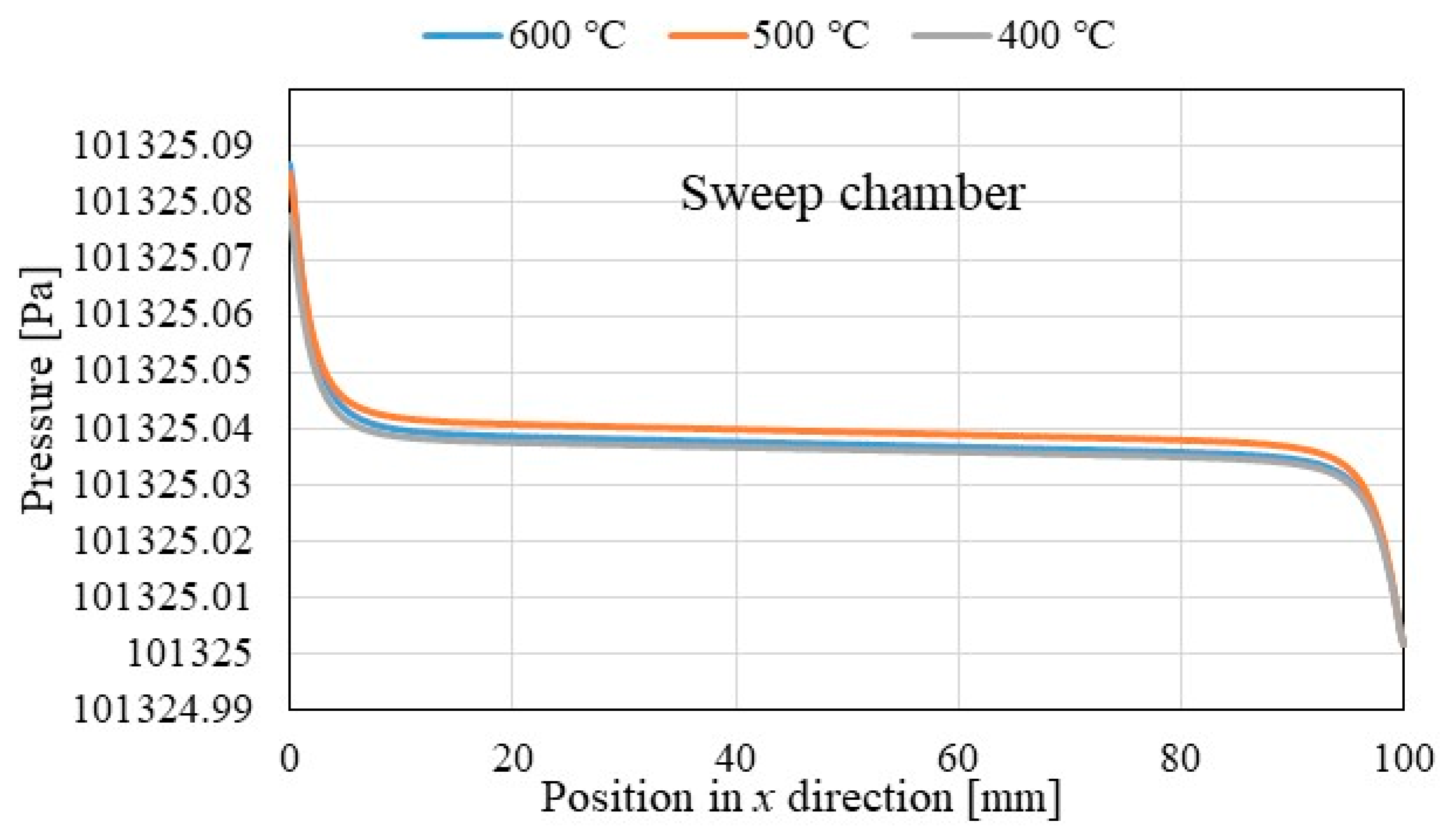

3.1. Comparison of the Distriburtion of Pressure along x Direction among Different Initial Reaction Temperature and Thickness of Pd/Cu Membrane

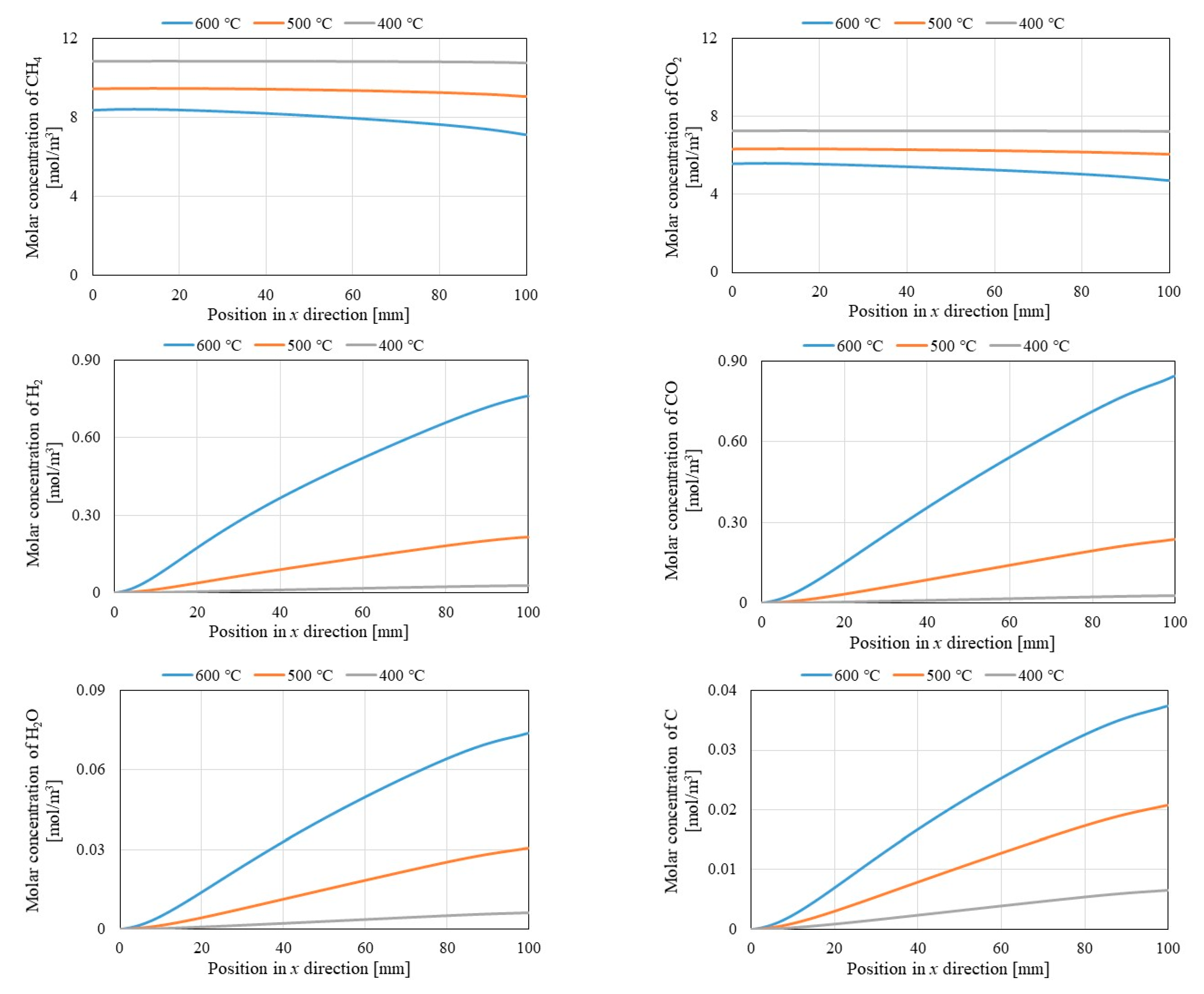

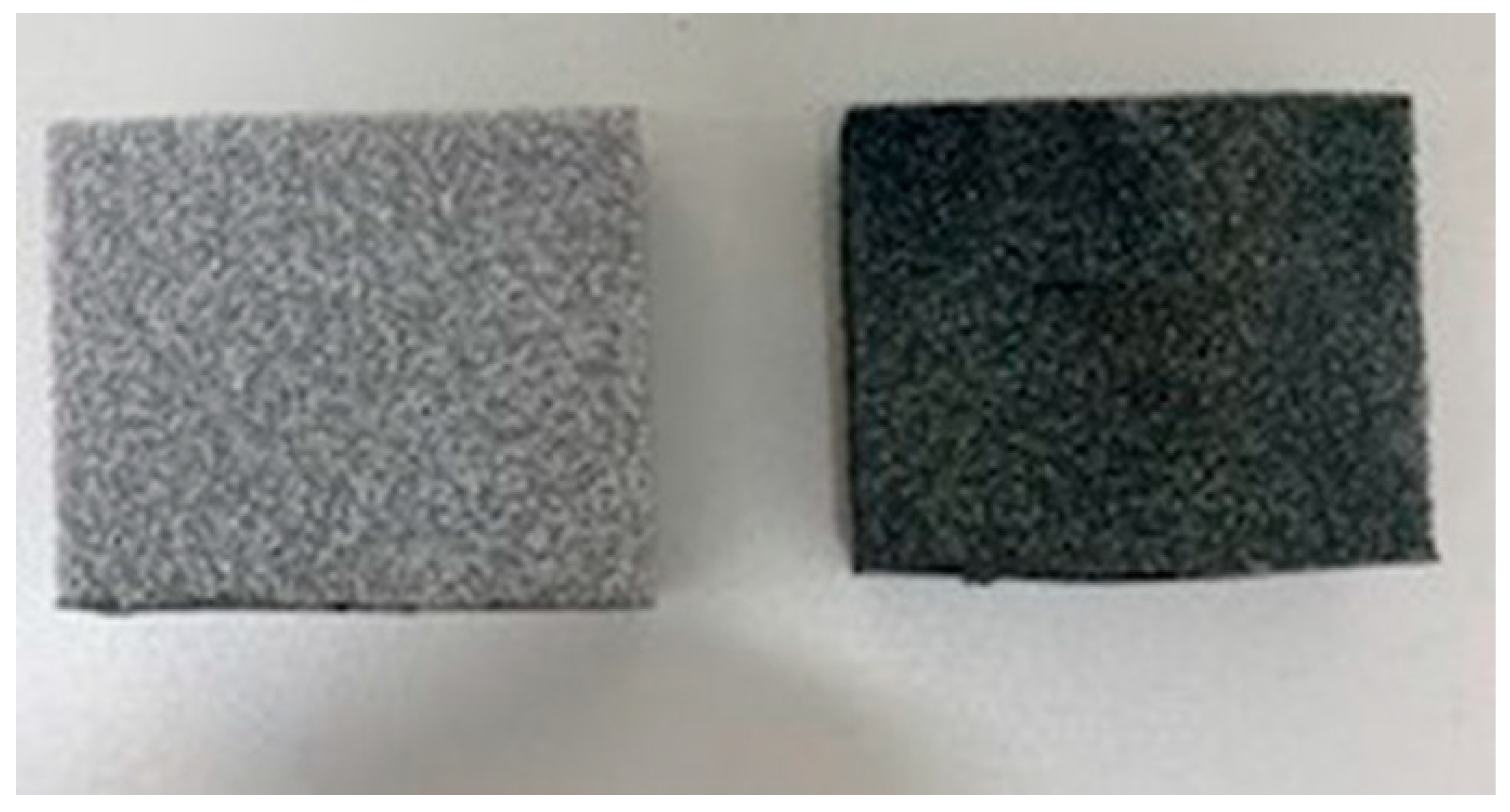

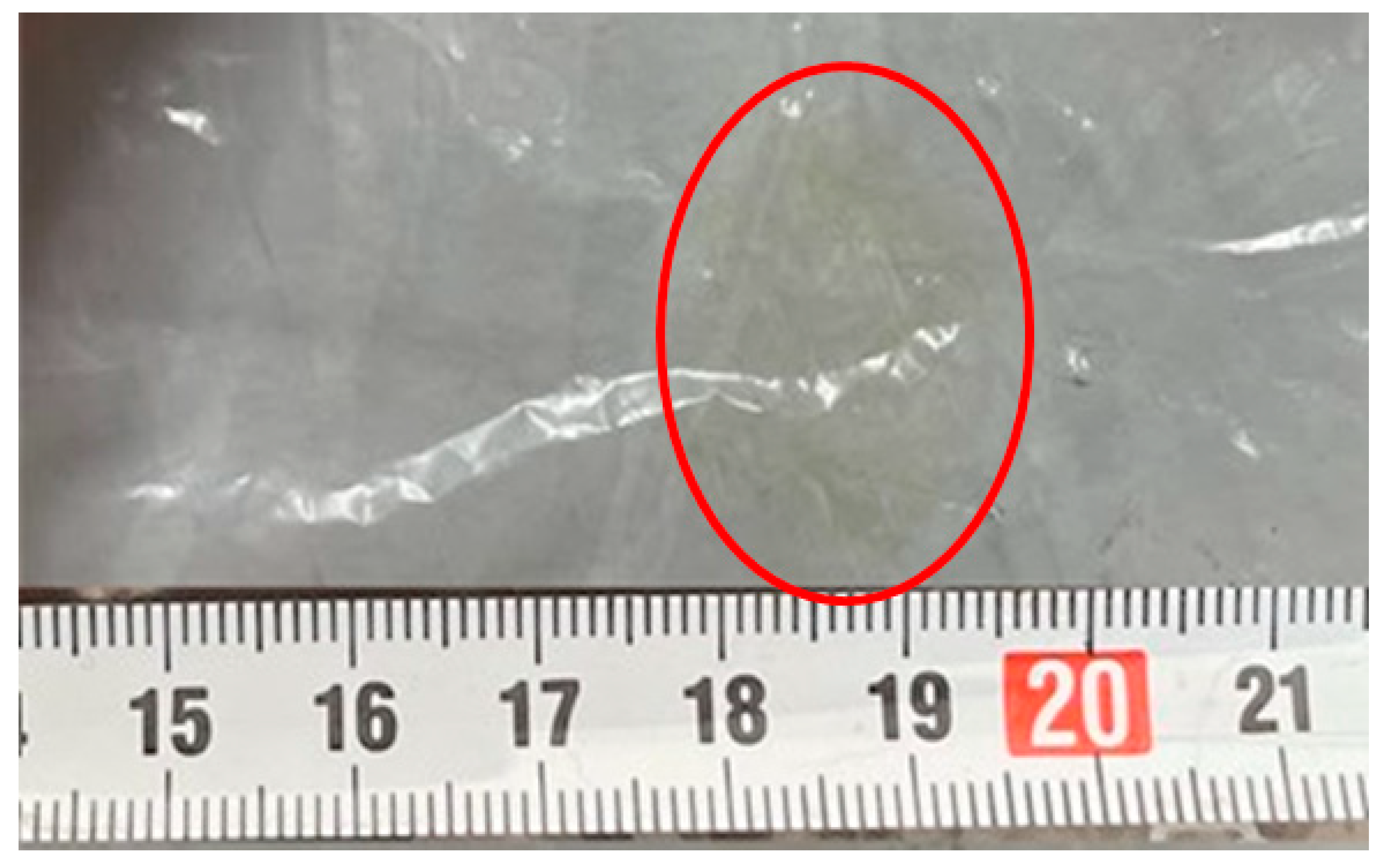

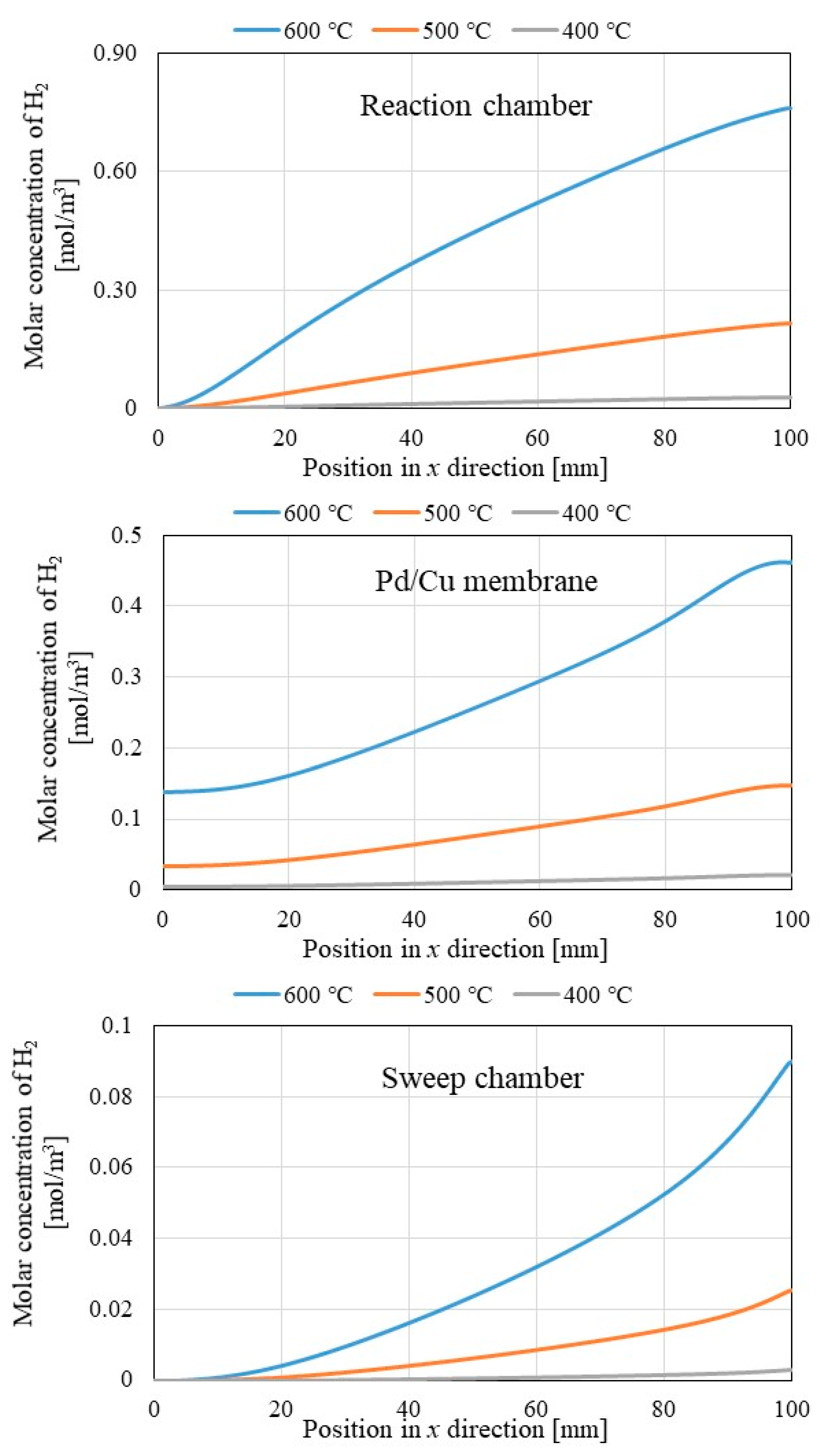

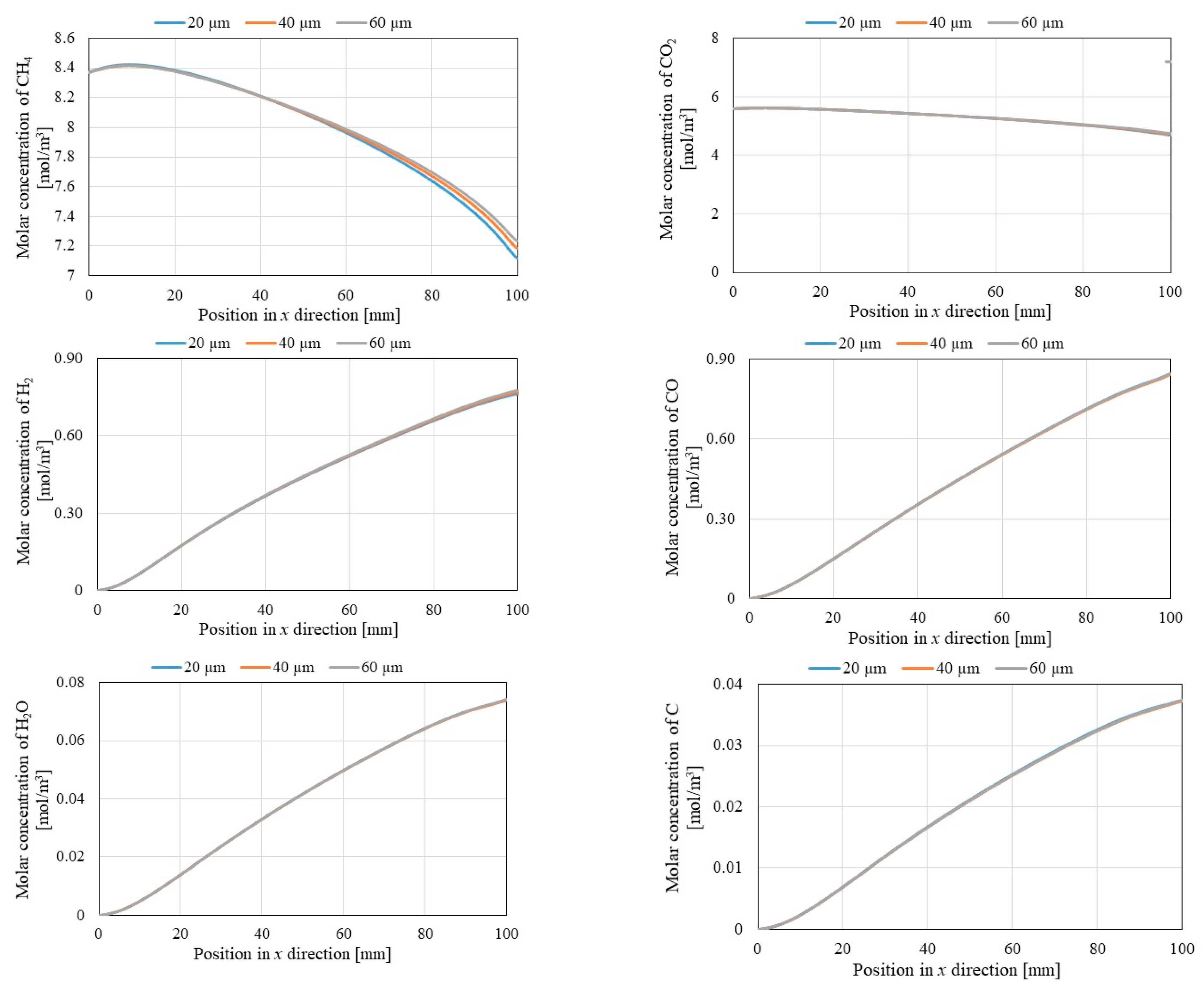

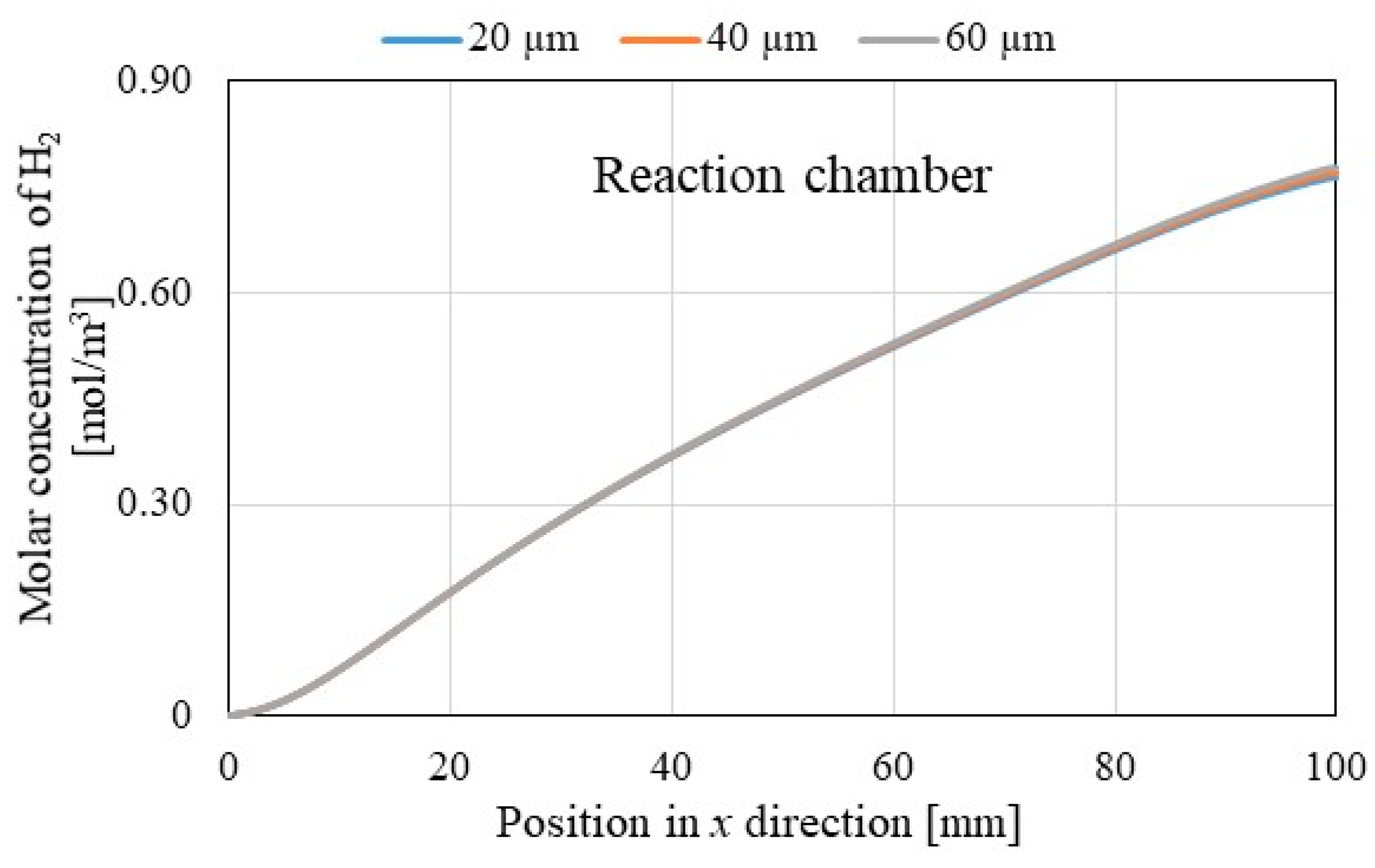

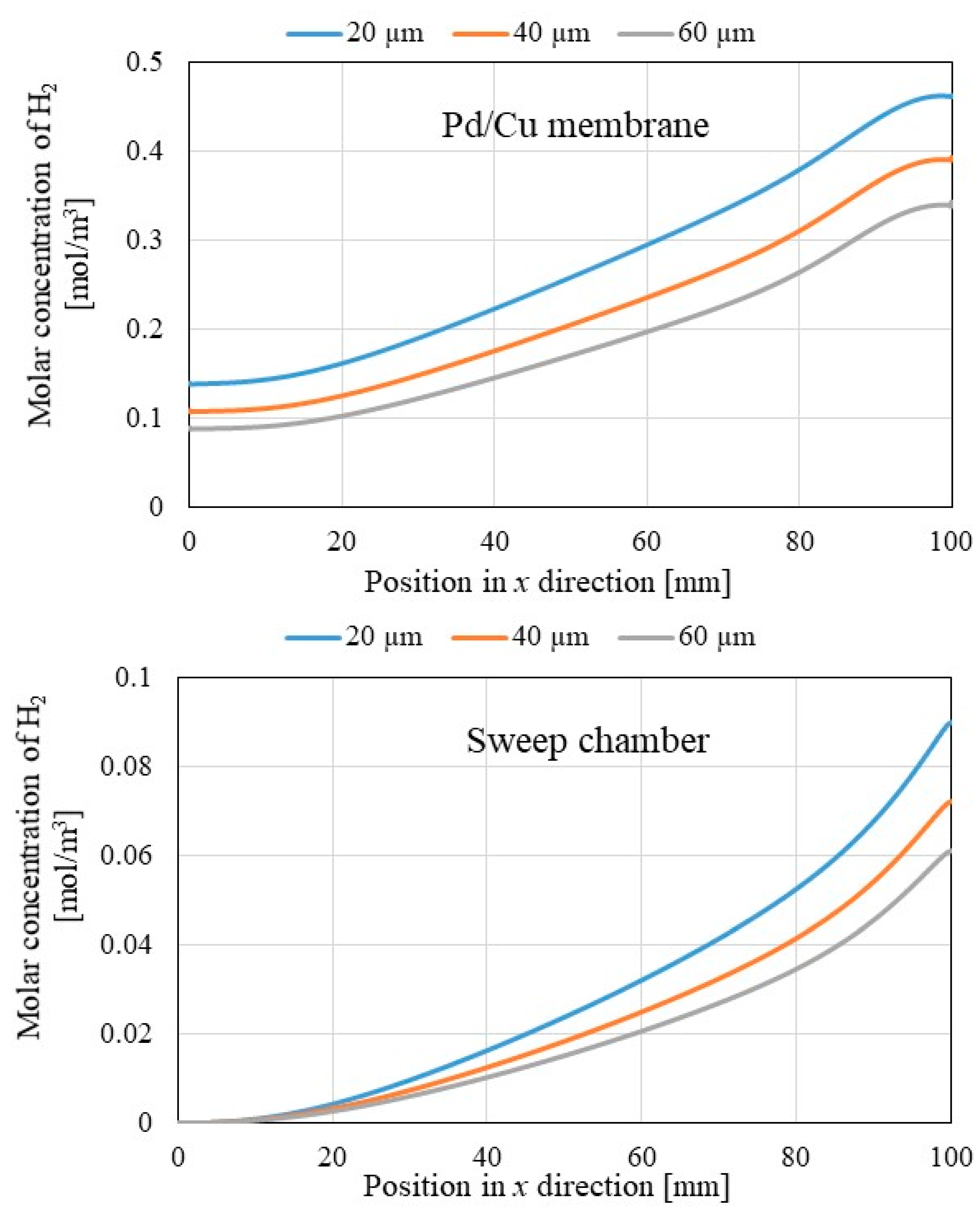

3.2. Comparison of Each Gas Concentration along x Direction among Different Initial Reaction Temperature and Thickness of Pd/Cu Membrane

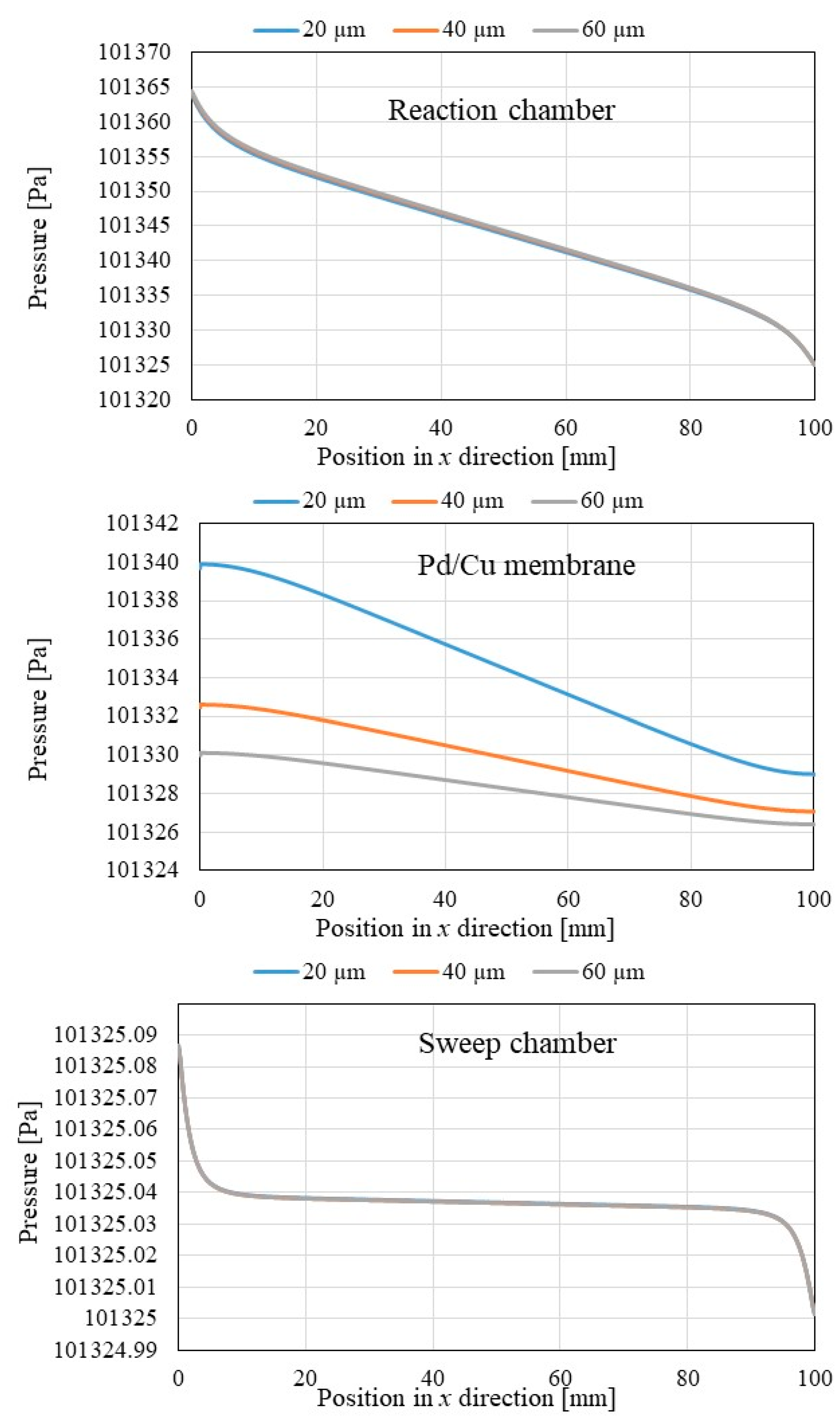

3.3. Investigation on Reaction Characteristics by Evaluation Factors

4. Conclusions

- (i)

- The pressure in reaction chamber as well as Pd/Cu membrane decreases along x direction and they increase with the increase in the initial reaction.

- (ii)

- The pressure in Pd/Cu membrane is higher with the decrease in the thickness of Pd/Cu membrane though the impact of the thickness of Pd/Cu membrane on pressure in reaction chamber and sweep chamber is very small.

- (iii)

- It is revealed that the molar concentrations of CH4 and CO2 decrease with the increase in the initial reaction temperature, while the molar concentrations of H2, CO, H2O and C increase with the increase in the initial reaction temperature. Since Equation (1) is an endothermic reaction, the molar concentrations of CH4 and CO2 decrease and those of H2 and CO increase with the increase in the initial reaction temperature. In addition, H2O and C are formed since it is thought that Equations (3), (4), (5) and (6) occur.

- (iv)

- It is revealed that the molar concentration of H2 increases along through x direction in reaction chamber, Pd/Cu membrane and sweep chamber. Since the H2 production reactions, i.e., Equations (1), (2) and (5) occur along through x direction, the molar concentration of H2 increases along through x direction.

- (v)

- It is revealed that the molar concentrations of H2 in reaction chamber, Pd/Cu membrane and sweep chamber increase with the increase in the initial reaction temperature. Since the H2 production reactions, i.e., Equations (1), (2) and (5) are endothermic reactions, the molar concentration of H2 increases with the increase in the initial reaction temperature.

- (vi)

- The molar concentrations of H2 in Pd/Cu membrane and sweep chamber are higher when the molar concentration of H2 in reaction chamber is higher. Since the molar concentration of H2 in reaction chamber is higher, the driving force to permeate the Pd/Cu membrane is stronger due to the large H2 partial pressure difference between the reaction chamber and the sweep chamber.

- (vii)

- It is revealed that the molar concentrations of H2 in Pd/Cu membrane and sweep chamber increase with the decrease in the thickness of Pd/Cu membrane. Since the penetration resistance of Pd/Cu membrane decreases with the decrease in the thickness of Pd/Cu membrane, the molar concentrations of H2 in Pd/Cu membrane and sweep are higher with the decrease in the thickness of Pd/Cu membrane.

- (viii)

- It is revealed that CH4 conversion, CO2 conversion and H2 yield increase with the increase in the initial reaction temperature as well as the decrease in the thickness of Pd/Cu membrane.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kalai, D.Y.; Stangeland, K.; Jin, R.; Tucho, W.M.; Yu, Z. Biogas dry reforming for syngas production on La promoted hydrotalcitederived Ni Catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 19438–19450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bioenergy Association. Available online: https://worldbioenergy.org/global-bioenergy-statistics (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- The Japan Gas Association. Available online: https://www.gas.or.jp/gas-life/biogas/ (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Nishimura, A.; Takada, T.; Ohata, S.; Kolhe, M.L. Biogas dry reforming for hydrogen through membrane reactor utilizing negative pressure. Fuels 2021, 2, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, A.; Hayashi, Y.; Ito, S.; Kolhe, M.L. Performance analysis of hydrogen production for a solid oxide fuel cell system using a biogas dry reforming membrane reactor with Ni and Ni/Cr catalysts. Fuels 2023, 4, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, A.; Sato, R.; Hu, E. An energy production system powered by solar heat with biogas dry reforming reactor and solar heat with biogas dry reforming reactor and solid oxide fuel cell. Smart Grid and Renew. Energy 2023, 14, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, M.Y.; Arbag, H.; Tasdemir, M.; Yasyerli, N.; Yasyerli, S. Effect of ceria content in Ni-Ce-Al catalyst on catalytic performance and carbon/coke formation in dry reforming of CH4. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 23013–23030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, P.; Meshksar, M.; Rahimpour, M.R. Biogas reforming over La-promoted Ni/SBA-16 catalyst for syngas production: catalytic structure and process activity investigation. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 6262–6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Ruiz, S.; Zhang, Q.; Gandara-Loe, J.; Pastor-Perez, L.; Odriozola, J.A.; Reina, T.R.; Bobadilla, L.F. H2-rich syngas production from biogas reforming: overcoming coking and sintering using bimetallic Ni-based catalysts. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 27907–27917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponugoti, P.V.; Pathmanathan, P.; Rapolu, J.; Gomathi, A.; Janardhanan, V.M. On the stability of Ni/γ-Al2O3 catalyst and the effect of H2O and O2 during biogas reforming. Applied Catalysis A, General 2023, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Espejo, J.L.; Merkouri, L.P.; Gandara-Loe, J.; Odriozola, J.A.; Reina, T.R.; Pastor-Perez, L. Nickel-based cerium zirconate inorganic complex structures for CO2 valorisation via dry reforming of methane. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2024, 140, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, A.N.T.; Nguyen, H.H.; Pham, T.P.T.; Pham, L.K.H.; Phuong, D.H.L.; Nguyen, N.A.; Vo, D.V.N.; Pham, P.T.H. Insight into the role of material basicity in the coke formation and performance of Ni/Al2O3 catalyst for the simulated-biogas dry reforming. Journal of the Energy Institute 2023, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, S.; Romero, M.; Faccio, R.; Segobia, D.; Apesteguia, C.; Perez, A.L.; Brondino, C.D.; Bussi, J. Biogas dry reforming over Ni-La-Ti catalysts for synthesis gas production: Effects of preparation method and biogas composition. Fuel 2023, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherbanski, R.; Kotkowski, T.; Molga, E. Thermogravimetric analysis of coking during dry reforming of methane. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 7346–7360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, A.; Yamada, S.; Ichii, R.; Ichikawa, M.; Hayakawa, T.; Kolhe, M.L. Hydrogen yield enhancement in biogas dry reforming with a Ni/Cr catalyst: A numerical study. energies 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokar, S.M.; Farokhnia, A.; Tavakolian, M.; Pejman, M.; Parvasi, P.; Javanmardi, J.; Zare, F.; Clara Gonqalves, M.; Basile, A. The recent areas of applicability of palladium based membrane technologies for hydrogen production from methane and natural gas: a review. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 6451–6476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, G.; Moon, D.K.; Kang, J.H.; Han, Y.J.; Kim, K.M.; Lee, C.H. High-purity hydrogen production via a water-gas-shift reaction in a palladium-copper catalytic membrane reactor integrated with pressure swing adsorption. Chemical Engineering Journal 2021, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lim, H. The power of molten salt in methane dry reforming: Conceptual design with a CFD study. Chemical Engineering Process.-Process Intersif. 2021, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lim, H. The effect of changing the number of membranes in methane carbon dioxide reforming: A CFD study. International Journal of Engineering Chemistry. 2020, 87, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemazadeh, K.; Ghahremani, M.; Amiri, T.Y.; Basile, A. Performance evaluation of Pd-Ag membrane reactor in glyceol steam reforming process: Development of the CFD model. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 1000–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Lee, S.; Lim, K. ; Numerical modeling studies for a methane dry reforming in a membrane reactor. J. Nat. Gas. Sci. Eng. 2016, 34, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, A.; Mishima, D.; Ito, S.; Konbu, T.; Hu, E. Impact of separator thickness on relationship between temperature distribution and mass & current density distribution in single HT-PEMFC. Thermal Science Engineering 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, A.; Ito, S.; Ichikawa, M.; Kolhe, M.L. Impact of thickness of Pd/Cu membrane on performance of biogas dry reforming membrane reactor utilizing Ni/Cr catalyst. fuels 2024, 5, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, A.; Ichikawa, M.; Yamada, S.; Ichii, R. The characteristics of a Ni/Cr/Ru catalyst for a biogas dry reforming membrane reactor using a Pd/Cu membrane and a comparison of it with a Ni/Cr catalyst. hydrogen 2024, 5, 414–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lim, H. The power of molten salt in methane dry reforming: conceptual design with a CFD study. Chemical Engineering and Processing 2020, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, A.; Sedaghat, M.H.; Jamshidi, S.; Shariati, A.; Rahimpour, M.R. A Comprehensive CFD simulation of an industrial-scale side-fired steam methane reformer to enhance hydrogen production. Chemical Engineering and processing 2023, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengerbaa, Y.; Virginieb, M.; Dumas, C. Computational fluid dynamics study of the dry reforming of methane over Ni/Al2O3 catalyst in membrane reactor – coke deposition. Kinetic and Catalysis 2017, 58, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaviani, M.; Rezaei, M.; Alavi, S.M.; Akbari, E. Biogas dry reforming over nickel-silica sandwiched core-shell catalyst with various shell thickness. Fuel 2024, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadis, A.G.; Siakavelas, G.I.; Tsiotsias, A.I.; Charisous, N.D.; Ehrhardt, B.; Wang, W.; Sebastian, V.; Hinder, S.J.; Baker, M.A.; Mascotto, S.; Goula, M.A. Biogas dry reforming over Ni/LnOx-type catalysts (Ln = La, Ce, Sm or Pr). International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 19953–19971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Espejo, J.L.; Merkouri, L.P.; Gandara-Loe, J.; Odriozola, J.A.; Reina, T.R.; Pastor-Perez, L. Nickel-based cerium zirconate inorganic complex structures for CO2 valorisation via dry reforming of methane. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2024, 140, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, P.; Meshksar, M.; Rahimpour, M.R. Biogas reforming over La-promoted Ni/SBA-16 catalyst for syngas production: Catalytic structure and process activity investigation. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 6262–6274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Initial reaction temperature [℃] | 400, 500, 600 |

| Pressure in reactor [Pa] | 1.013×105 |

| Inlet flow rate of CH4 [NL/min] (CH4:CO2 = 1.5:1) |

1.088 |

| Inlet flow rate of CO2 [NL/min] (CH4:CO2 = 1.5:1) |

0.725 |

| Outlet pressure [Pa] | 1.013×105 |

| Density of catalyst [kg/m3] | 1045, 1042, 1040 (@400 ℃, 500 ℃, 600 ℃) |

| Porosity of catalyst (εp) [-] | 0.95 |

| Permeability of catalyst [m2] | 1.7×0-8, 1.6×10-8, 1.5×10-9 |

| Constant pressure of specific heat of catalyst [J/(kg·K)] |

327, 333, 340 |

| Thermal conductivity of catalyst [W/(m·K)] |

197, 194, 192 |

| Thickness of Pd/Cu membrane of 20 m | |||||

| Initial reaction temperature [℃] | CH4 conversion [%] | CO2 conversion [%] | H2 yield [%] | H2 selectivity [%] | CO selectivity [%] |

| 600 | 15.0 | 15.9 | 5.09 | 49.1 | 50.9 |

| 500 | 4.03 | 3.73 | 1.14 | 46.4 | 53.6 |

| 400 | 1.10 | 0.49 | 0.15 | 52.2 | 47.8 |

| Initial temperature of 600 ℃ | |||||

| Thickness of Pd/Cu membrane [μm] | CH4 conversion [%] | CO2 conversion [%] | H2 yield [%] | H2 selectivity [%] | CO selectivity [%] |

| 20 | 15.0 | 15.9 | 5.09 | 49.1 | 50.9 |

| 40 | 14.2 | 15.4 | 5.02 | 49.2 | 50.8 |

| 60 | 13.5 | 15.0 | 5.00 | 49.2 | 50.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).