Submitted:

06 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mineralocorticoid Receptors (MRs)

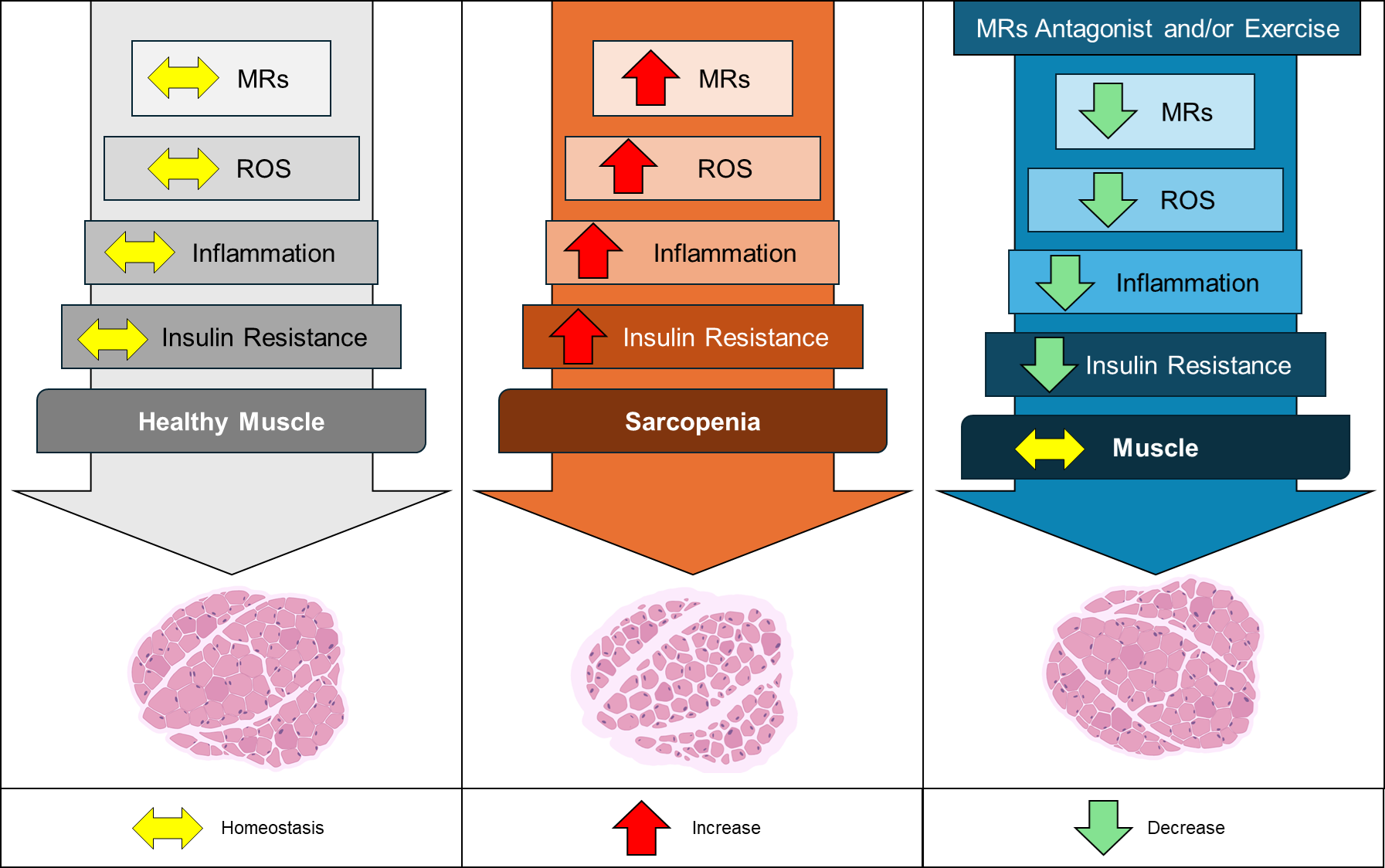

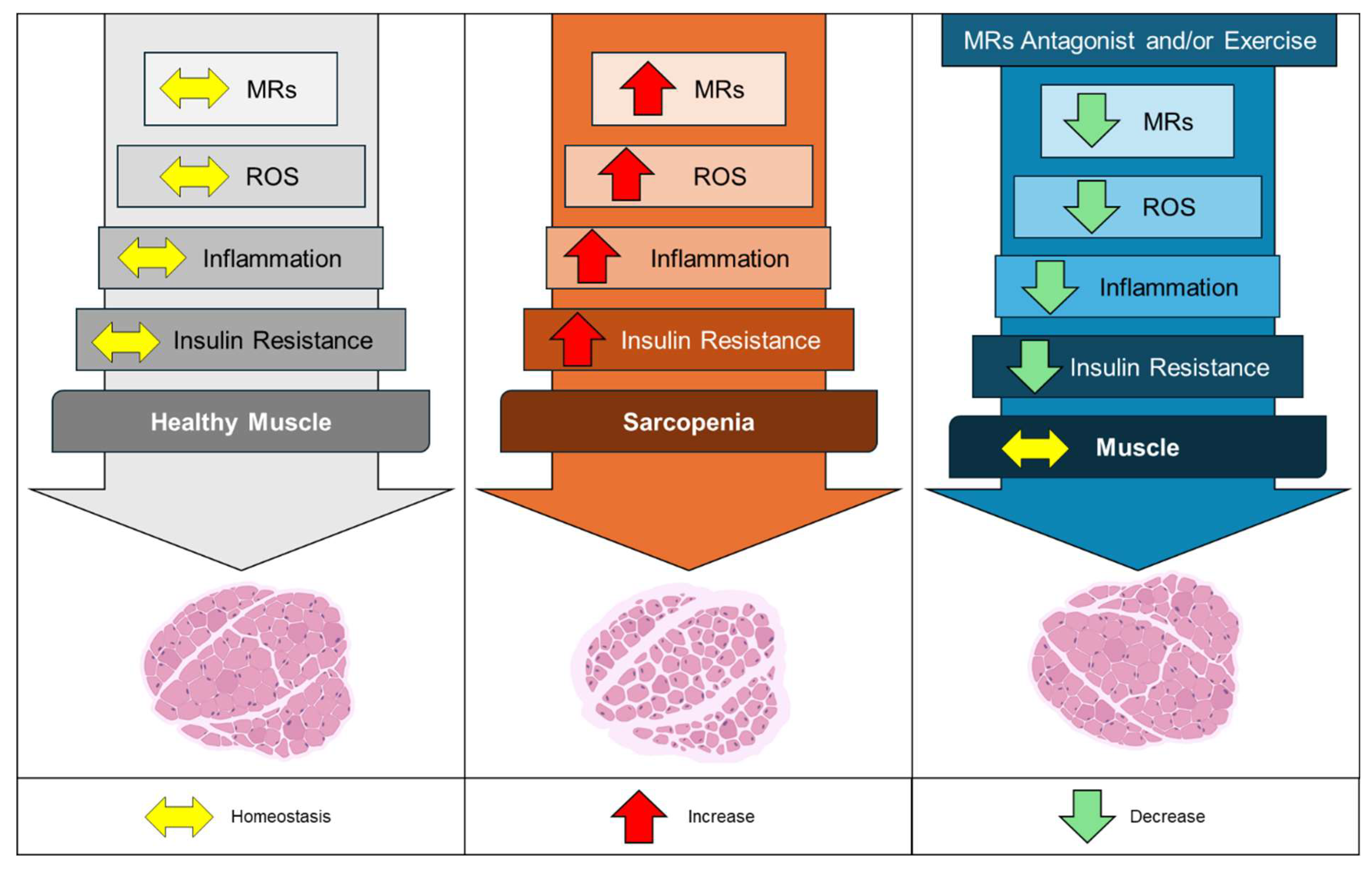

2.1. Skeletal Muscle Aging: Insights into the Drivers of Sarcopenia

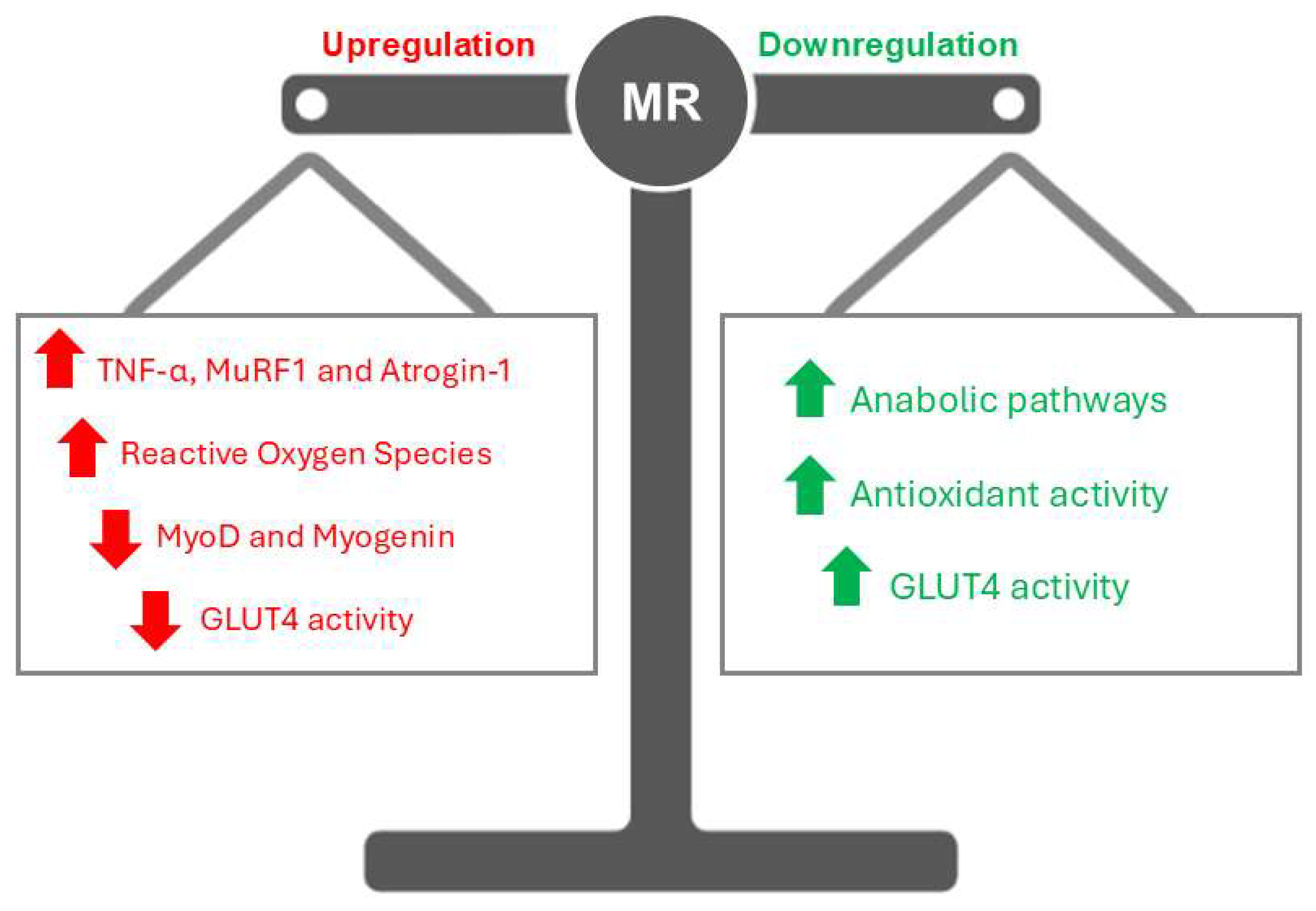

2.2. MR Activation: Bridging Ion Transport and Insulin Resistance

2.3. Linking MRs to Oxidative Stress and Inflammation

2.4. Harnessing MR Antagonists for Therapy

2.5. Exercise as a Modulator of MRs

2.6. Future Perspectives

3. Conclusion

References

- Trombetti, A.; Reid, K.F.; Hars, M.; Herrmann, F.R.; Pasha, E.; Phillips, E.M.; Fielding, R.A. Age-Associated Declines in Muscle Mass, Strength, Power, and Physical Performance: Impact on Fear of Falling and Quality of Life. Osteoporos Int 2016, 27, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, H.K. Sarcopenia and Aging. Nutrition Reviews 2003, 61, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landi, F.; Liperoti, R.; Russo, A.; Giovannini, S.; Tosato, M.; Capoluongo, E.; Bernabei, R.; Onder, G. Sarcopenia as a Risk Factor for Falls in Elderly Individuals: Results from the ilSIRENTE Study. Clinical Nutrition 2012, 31, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirks, A.J.; Hofer, T.; Marzetti, E.; Pahor, M.; Leeuwenburgh, C. Mitochondrial DNA Mutations, Energy Metabolism and Apoptosis in Aging Muscle. Ageing Research Reviews 2006, 5, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shou, J.; Chen, P.-J.; Xiao, W.-H. Mechanism of Increased Risk of Insulin Resistance in Aging Skeletal Muscle. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2020, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, Y.; Deng, S.; Lian, Z.; Yu, K. Skeletal Muscle Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Aging: Focus on Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Therapy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 964130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Bustos, A.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, B.; Carnicero-Carreño, J.A.; Sepúlveda-Loyola, W.; Garcia-Garcia, F.J.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Healthcare Cost Expenditures Associated to Frailty and Sarcopenia. BMC Geriatr 2022, 22, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Meng, J. Exercise for Prevention and Relief of Cardiovascular Disease: Prognoses, Mechanisms, and Approaches. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2019, 2019, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, J.A.; Hauck, J.S.; Lowe, J.; Shaw, J.J.; Guttridge, D.C.; Gomez-Sanchez, C.E.; Gomez-Sanchez, E.P.; Rafael-Fortney, J.A. Mineralocorticoid Receptors Are Present in Skeletal Muscle and Represent a Potential Therapeutic Target. FASEB j. 2015, 29, 4544–4554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Z.M.; Gomatam, C.K.; Rabolli, C.P.; Lowe, J.; Piepho, A.B.; Bansal, S.S.; Accornero, F.; Rafael-Fortney, J.A. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists and Glucocorticoids Differentially Affect Skeletal Muscle Inflammation and Pathology in Muscular Dystrophy. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e159875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Z.M.; Gomatam, C.K.; Piepho, A.B.; Rafael-Fortney, J.A. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Signaling in the Inflammatory Skeletal Muscle Microenvironments of Muscular Dystrophy and Acute Injury. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 942660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, E.T.; Berman, S.; Streicher, J.; Estrada, C.M.; Caldwell, J.L.; Ghisays, V.; Ulrich-Lai, Y.; Solomon, M.B. Effects of Combined Glucocorticoid/Mineralocorticoid Receptor Modulation (CORT118335) on Energy Balance, Adiposity, and Lipid Metabolism in Male Rats. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2019, 317, E337–E349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Sanchez, E.; Gomez-Sanchez, C.E. The Multifaceted Mineralocorticoid Receptor. In Comprehensive Physiology; Terjung, R., Ed.; Wiley, 2014; pp. 965–994 ISBN 978-0-470-65071-4.

- Zennaro, M.-C.; Caprio, M.; Fève, B. Mineralocorticoid Receptors in the Metabolic Syndrome. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 2009, 20, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.J. Mechanisms of Mineralocorticoid Receptor-Mediated Cardiac Fibrosis and Vascular Inflammation. Current Opinion in Nephrology & Hypertension 2008, 17, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Le Tallec, L.; Lombès, M. The Mineralocorticoid Receptor: A Journey Exploring Its Diversity and Specificity of Action. Molecular Endocrinology 2005, 19, 2211–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudenzi, C.; Mifsud, K.R.; Reul, J.M.H.M. Insights into Isoform-Specific Mineralocorticoid Receptor Action in the Hippocampus. Journal of Endocrinology 2023, 258, e220293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Menuet, D.; Viengchareun, S.; Muffat-Joly, M.; Zennaro, M.-C.; Lombès, M. Expression and Function of the Human Mineralocorticoid Receptor: Lessons from Transgenic Mouse Models. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 2004, 217, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarrola, J.; Lu, Q.; Zennaro, M.-C.; Jaffe, I.Z. Mechanism by Which Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Induce Mineralocorticoid Receptor Gene Expression in Aging Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Hypertension 2023, 80, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, E.; Lombès, M. The Mineralocorticoid Receptor: A New Player Controlling Energy Homeostasis. Hormone Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigation 2013, 15, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulse, J.L.; Habibi, J.; Igbekele, A.E.; Zhang, B.; Li, J.; Whaley-Connell, A.; Sowers, J.R.; Jia, G. Mineralocorticoid Receptors Mediate Diet-Induced Lipid Infiltration of Skeletal Muscle and Insulin Resistance. Endocrinology 2022, 163, bqac145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzetti, E.; Privitera, G.; Simili, V.; Wohlgemuth, S.E.; Aulisa, L.; Pahor, M.; Leeuwenburgh, C. Multiple Pathways to the Same End: Mechanisms of Myonuclear Apoptosis in Sarcopenia of Aging. The Scientific World JOURNAL 2010, 10, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, L.A.; McMurdo, M.E.T.; Struthers, A.D. Mineralocorticoid Antagonism: A Novel Way to Treat Sarcopenia and Physical Impairment in Older People?: Mineralocorticoid Antagonism. Clinical Endocrinology 2011, 75, 725–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, G.; Trevisan, C.; Carraro, S.; Solmi, M.; Luchini, C.; Stubbs, B.; Manzato, E.; Sergi, G.; Veronese, N. Inflammation and Sarcopenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Maturitas 2017, 96, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalle, S.; Rossmeislova, L.; Koppo, K. The Role of Inflammation in Age-Related Sarcopenia. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellanti, F.; Buglio, A.L.; Vendemiale, G. Oxidative Stress and Sarcopenia. In Aging; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 95–103 ISBN 978-0-12-818698-5.

- Cleasby, M.E.; Jamieson, P.M.; Atherton, P.J. Insulin Resistance and Sarcopenia: Mechanistic Links between Common Co-Morbidities. Journal of Endocrinology 2016, 229, R67–R81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alway, S.E.; Myers, M.J.; Mohamed, J.S. Regulation of Satellite Cell Function in Sarcopenia. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhee, J.S.; Cameron, J.; Maden-Wilkinson, T.; Piasecki, M.; Yap, M.H.; Jones, D.A.; Degens, H. The Contributions of Fiber Atrophy, Fiber Loss, In Situ Specific Force, and Voluntary Activation to Weakness in Sarcopenia. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 2018, 73, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, H.; Fukunishi, S.; Asai, A.; Yokohama, K.; Nishiguchi, S.; Higuchi, K. Pathophysiology and Mechanisms of Primary Sarcopenia (Review). Int J Mol Med 2021, 48, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Lockette, W.; Sowers, J.R. Mineralocorticoid Receptors in the Pathogenesis of Insulin Resistance and Related Disorders: From Basic Studies to Clinical Disease. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2021, 320, R276–R286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuster, G.M.; Kotlyar, E.; Rude, M.K.; Siwik, D.A.; Liao, R.; Colucci, W.S.; Sam, F. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Inhibition Ameliorates the Transition to Myocardial Failure and Decreases Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Mice With Chronic Pressure Overload. Circulation 2005, 111, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, G.G.; Kapoor, S.C. Potassium Supplementation Ameliorates Mineralocorticoid-Induced Sodium Retention. Kidney International 1993, 43, 1097–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurkat-Rott, K.; Weber, M.-A.; Fauler, M.; Guo, X.-H.; Holzherr, B.D.; Paczulla, A.; Nordsborg, N.; Joechle, W.; Lehmann-Horn, F. K + -Dependent Paradoxical Membrane Depolarization and Na + Overload, Major and Reversible Contributors to Weakness by Ion Channel Leaks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009, 106, 4036–4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenhut, M.; Wallace, H. Ion Channels in Inflammation. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol 2011, 461, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faught, E.; Vijayan, M.M. The Mineralocorticoid Receptor Functions as a Key Glucose Regulator in the Skeletal Muscle of Zebrafish. Endocrinology 2022, 163, bqac149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feraco, A.; Marzolla, V.; Scuteri, A.; Armani, A.; Caprio, M. Mineralocorticoid Receptors in Metabolic Syndrome: From Physiology to Disease. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 2020, 31, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, S.B.; McGraw, A.P.; Jaffe, I.Z.; Sowers, J.R. Mineralocorticoid Receptor–Mediated Vascular Insulin Resistance. Diabetes 2013, 62, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korol, S.; Mottet, F.; Perreault, S.; Baker, W.L.; White, M.; De Denus, S. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists on Glucose Homeostasis. Medicine 2017, 96, e8719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Chimal, J.; Lima-Posada, I.; Bakris, G.L.; Jaisser, F. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists in Diabetic Kidney Disease — Mechanistic and Therapeutic Effects. Nat Rev Nephrol 2022, 18, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelucci, A.; Liang, C.; Protasi, F.; Dirksen, R.T. Altered Ca2+ Handling and Oxidative Stress Underlie Mitochondrial Damage and Skeletal Muscle Dysfunction in Aging and Disease. Metabolites 2021, 11, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, E.; Coleman, R.; Reznick, A.Z. The Biochemistry of Aging Muscle. Experimental Gerontology 2002, 37, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorini, S.; Kim, S.K.; Infante, M.; Mammi, C.; La Vignera, S.; Fabbri, A.; Jaffe, I.Z.; Caprio, M. Role of Aldosterone and Mineralocorticoid Receptor in Cardiovascular Aging. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, P.J.; Young, M.J. Mechanisms of Mineralocorticoid Action. Hypertension 2005, 46, 1227–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, S.-J.; Yu, L.-J. Oxidative Stress, Molecular Inflammation and Sarcopenia. IJMS 2010, 11, 1509–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, M.B.; Li, Y.-P. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α and Muscle Wasting: A Cellular Perspective. Respir Res 2001, 2, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clavel, S.; Coldefy, A.-S.; Kurkdjian, E.; Salles, J.; Margaritis, I.; Derijard, B. Atrophy-Related Ubiquitin Ligases, Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 Are up-Regulated in Aged Rat Tibialis Anterior Muscle. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development 2006, 127, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langen, R.C.J.; Velden, J.L.J.; Schols, A.M.W.J.; Kelders, M.C.J.M.; Wouters, E.F.M.; Janssen-Heininger, Y.M.W. Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha Inhibits Myogenic Differentiation through MyoD Protein Destabilization. FASEB j. 2004, 18, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantong, B.; Kratschmar, D.V.; Nashev, L.G.; Balazs, Z.; Odermatt, A. Mineralocorticoid and Glucocorticoid Receptors Differentially Regulate NF-kappaB Activity and pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Production in Murine BV-2 Microglial Cells. J Neuroinflammation 2012, 9, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangaraj, S.S.; Oxlund, C.S.; Fonseca, M.P.D.; Svenningsen, P.; Stubbe, J.; Palarasah, Y.; Ketelhuth, D.F.J.; Jacobsen, Ib.A.; Jensen, B.L. The Mineralocorticoid Receptor Blocker Spironolactone Lowers Plasma Interferon-γ and Interleukin-6 in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Treatment-Resistant Hypertension. Journal of Hypertension 2022, 40, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sønder, S.U.S.; Mikkelsen, M.; Rieneck, K.; Hedegaard, C.J.; Bendtzen, K. Effects of Spironolactone on Human Blood Mononuclear Cells: Mineralocorticoid Receptor Independent Effects on Gene Expression and Late Apoptosis Induction. British J Pharmacology 2006, 148, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.; Li, Y.-L. Inflammation Balance in Skeletal Muscle Damage and Repair. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1133355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenakker, K.G.M.; Ling, C.H.; Meskers, C.G.M.; De Craen, A.J.M.; Stijnen, T.; Westendorp, R.G.J.; Maier, A.B. Patterns of Muscle Strength Loss with Age in the General Population and Patients with a Chronic Inflammatory State. Ageing Research Reviews 2010, 9, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomarasca, M.; Banfi, G.; Lombardi, G. Myokines: The Endocrine Coupling of Skeletal Muscle and Bone. In Advances in Clinical Chemistry; Elsevier, 2020; Vol. 94, pp. 155–218 ISBN 978-0-12-820801-4.

- Lightfoot, A.P.; Cooper, R.G. The Role of Myokines in Muscle Health and Disease. Current Opinion in Rheumatology 2016, 28, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, S.K.; Ji, L.L.; Kavazis, A.N.; Jackson, M.J. Reactive Oxygen Species: Impact on Skeletal Muscle. In Comprehensive Physiology; Prakash, Y.S., Ed.; Wiley, 2011; pp. 941–969 ISBN 978-0-470-65071-4.

- Fulle, S.; Protasi, F.; Di Tano, G.; Pietrangelo, T.; Beltramin, A.; Boncompagni, S.; Vecchiet, L.; Fanò, G. The Contribution of Reactive Oxygen Species to Sarcopenia and Muscle Ageing. Experimental Gerontology 2004, 39, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burniston, J.; Saini, A.; Tan, L.; Goldspink, D. Aldosterone Induces Myocyte Apoptosis in the Heart and Skeletal Muscles of Rats in Vivo. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 2005, 39, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lastra, G.; Whaley-Connell, A.; Manrique, C.; Habibi, J.; Gutweiler, A.A.; Appesh, L.; Hayden, M.R.; Wei, Y.; Ferrario, C.; Sowers, J.R. Low-Dose Spironolactone Reduces Reactive Oxygen Species Generation and Improves Insulin-Stimulated Glucose Transport in Skeletal Muscle in the TG(mRen2)27 Rat. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2008, 295, E110–E116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rains, J.L.; Jain, S.K. Oxidative Stress, Insulin Signaling, and Diabetes. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2011, 50, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefranc, C.; Friederich-Persson, M.; Palacios-Ramirez, R.; Nguyen Dinh Cat, A. Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress in Obesity: Role of the Mineralocorticoid Receptor. Journal of Endocrinology 2018, 238, R143–R159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Kim, D.A.; Choi, E.; Lee, Y.S.; Park, S.J.; Kim, B.-J. Aldosterone Inhibits In Vitro Myogenesis by Increasing Intracellular Oxidative Stress via Mineralocorticoid Receptor. Endocrinol Metab 2021, 36, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefranc, C.; Friederich-Persson, M.; Braud, L.; Palacios-Ramirez, R.; Karlsson, S.; Boujardine, N.; Motterlini, R.; Jaisser, F.; Nguyen Dinh Cat, A. MR (Mineralocorticoid Receptor) Induces Adipose Tissue Senescence and Mitochondrial Dysfunction Leading to Vascular Dysfunction in Obesity. Hypertension 2019, 73, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzetti, E.; Wohlgemuth, S.E.; Lees, H.A.; Chung, H.-Y.; Giovannini, S.; Leeuwenburgh, C. Age-Related Activation of Mitochondrial Caspase-Independent Apoptotic Signaling in Rat Gastrocnemius Muscle. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development 2008, 129, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, J.; Kadakia, F.K.; Zins, J.G.; Haupt, M.; Peczkowski, K.K.; Rastogi, N.; Floyd, K.T.; Gomez-Sanchez, E.P.; Gomez-Sanchez, C.E.; Elnakish, M.T.; et al. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists in Muscular Dystrophy Mice During Aging and Exercise. JND 2018, 5, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieronne-Deperrois, M.; Guéret, A.; Djerada, Z.; Crochemore, C.; Harouki, N.; Henry, J.; Dumesnil, A.; Larchevêque, M.; Do Rego, J.; Do Rego, J.; et al. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Blockade with Finerenone Improves Heart Function and Exercise Capacity in Ovariectomized Mice. ESC Heart Failure 2021, 8, 1933–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellhoener, P.; Born, J.; Fehm, H.L.; Dodt, C. Elevated Resting and Exercise-Induced Cortisol Levels after Mineralocorticoid Receptor Blockade with Canrenoate in Healthy Humans. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2004, 89, 5048–5052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.-Z.; No, M.-H.; Heo, J.-W.; Park, D.-H.; Kang, J.-H.; Kim, S.H.; Kwak, H.-B. Role of Exercise in Age-Related Sarcopenia. J Exerc Rehabil 2018, 14, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vgontzas, A.N.; Chrousos, G.P. Sleep, the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis, and Cytokines: Multiple Interactions and Disturbances in Sleep Disorders. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America 2002, 31, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duclos, M.; Tabarin, A. Exercise and the Hypothalamo-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis. In Frontiers of Hormone Research; Lanfranco, F., Strasburger, C.J., Eds.; S. Karger AG, 2016; Vol. 47, pp. 12–26 ISBN 978-3-318-05868-0.

- Piovezan, R.D.; Abucham, J.; Dos Santos, R.V.T.; Mello, M.T.; Tufik, S.; Poyares, D. The Impact of Sleep on Age-Related Sarcopenia: Possible Connections and Clinical Implications. Ageing Research Reviews 2015, 23, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valaiyapathi, B.; Calhoun, D.A. Role of Mineralocorticoid Receptors in Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Metabolic Syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep 2018, 20, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattilo, M.; Antunes, H.K.M.; Medeiros, A.; Mônico Neto, M.; Souza, H.S.; Tufik, S.; De Mello, M.T. Sleep and Muscle Recovery: Endocrinological and Molecular Basis for a New and Promising Hypothesis. Medical Hypotheses 2011, 77, 220–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolezal, B.A.; Neufeld, E.V.; Boland, D.M.; Martin, J.L.; Cooper, C.B. Interrelationship between Sleep and Exercise: A Systematic Review. Advances in Preventive Medicine 2017, 2017, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghouts, L.B.; Keizer, H.A. Exercise and Insulin Sensitivity: A Review. Int J Sports Med 2000, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peake, J.M.; Della Gatta, P.; Suzuki, K.; Nieman, D.C. Cytokine Expression and Secretion by Skeletal Muscle Cells: Regulatory Mechanisms and Exercise Effects. Exerc Immunol Rev 2015, 21, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hurst, C.; Robinson, S.M.; Witham, M.D.; Dodds, R.M.; Granic, A.; Buckland, C.; De Biase, S.; Finnegan, S.; Rochester, L.; Skelton, D.A.; et al. Resistance Exercise as a Treatment for Sarcopenia: Prescription and Delivery. Age and Ageing 2022, 51, afac003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafael-Fortney, J.A.; Chimanji, N.S.; Schill, K.E.; Martin, C.D.; Murray, J.D.; Ganguly, R.; Stangland, J.E.; Tran, T.; Xu, Y.; Canan, B.D.; et al. Early Treatment With Lisinopril and Spironolactone Preserves Cardiac and Skeletal Muscle in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Mice. Circulation 2011, 124, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitt, B.; Zannad, F.; Remme, W.J.; Cody, R.; Castaigne, A.; Perez, A.; Palensky, J.; Wittes, J. The Effect of Spironolactone on Morbidity and Mortality in Patients with Severe Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 1999, 341, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spirduso, W.W.; Cronin, D.L. Exercise Dose-Response Effects on Quality of Life and Independent Living in Older Adults: Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 2001, 33, S598–S608. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).