Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

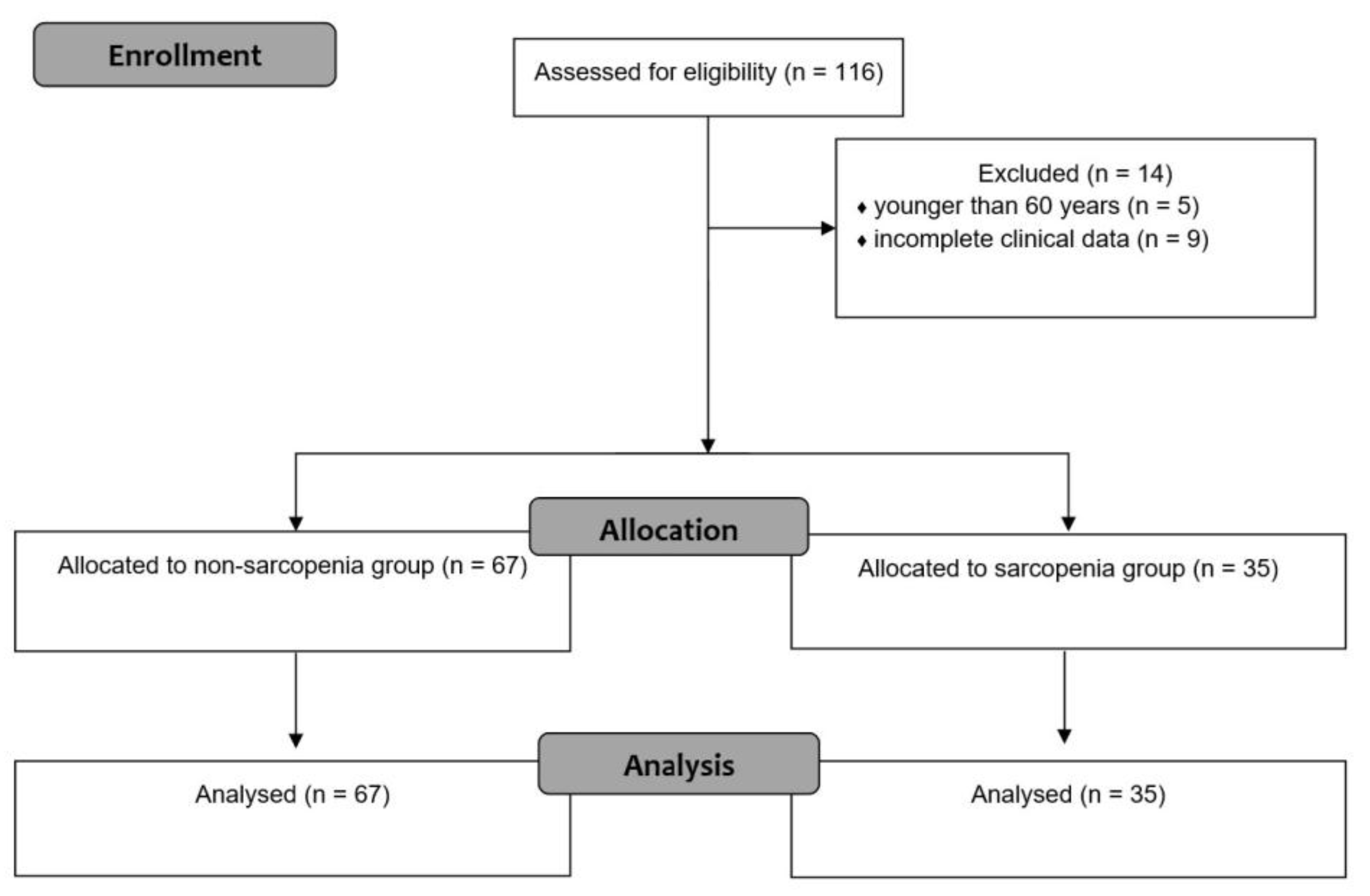

2. Materials and Methods

Radiofrequency Ablation Procedure

Clinical Data Collection

Outcome Measures

Statistical Analysis

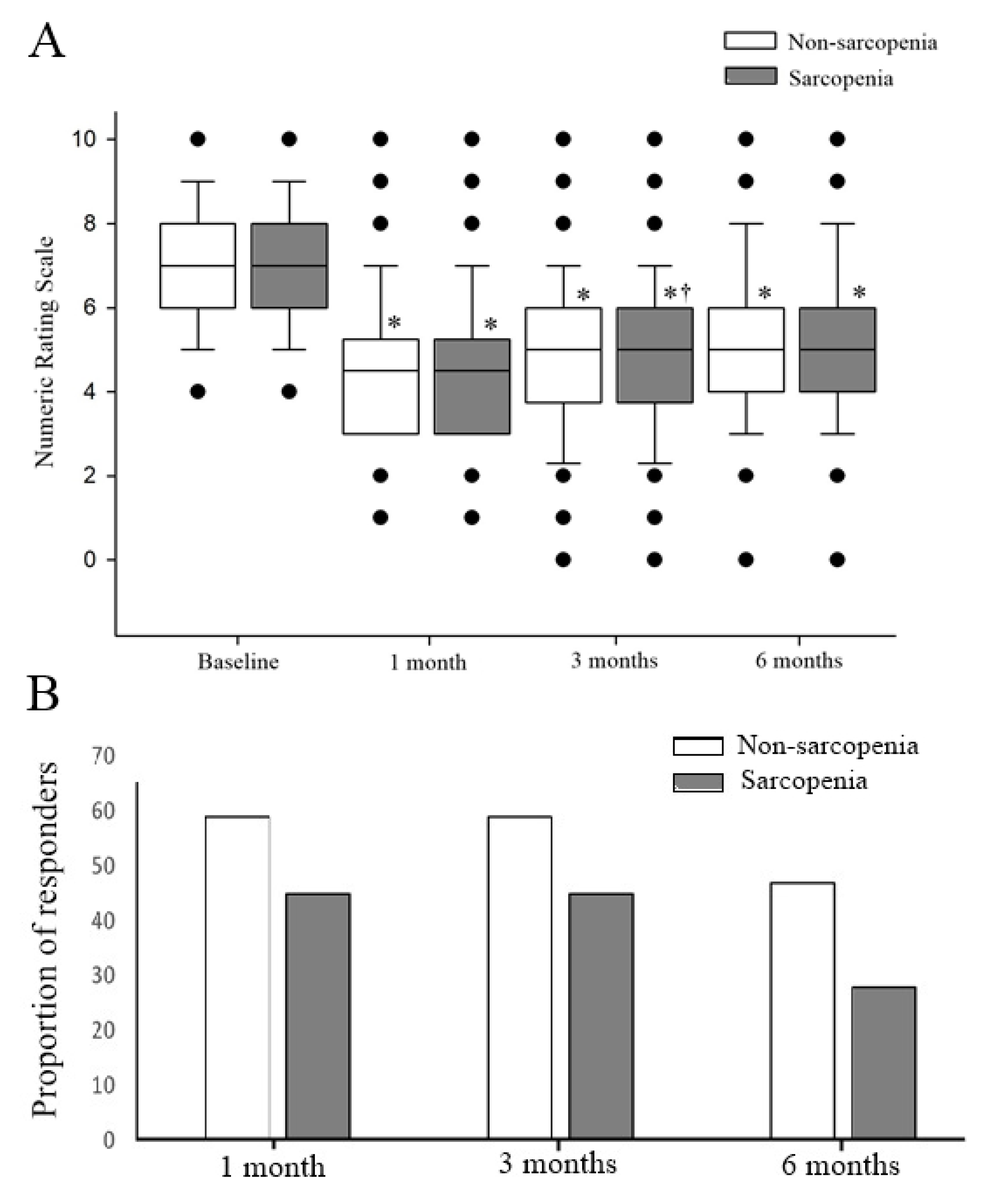

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MBB | medial branch block |

| RFA | Radiofrequency ablation |

| PMI | psoas muscle index |

| PLVI | psoas-lumbar vertebral index |

| PSMI | paraspinal muscle index |

| CT | computed tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| BMI | body mass index |

| NRS | Numeric Rating Scale |

| CSA | cross-sectional area |

References

- Manchikanti, L.; Kosanovic, R.; Pampati, V.; Cash, K.A.; Soin, A.; Kaye, A.D.; Hirsch, J.A. Low Back Pain and Diagnostic Lumbar Facet Joint Nerve Blocks: Assessment of Prevalence, False-Positive Rates, and a Philosophical Paradigm Shift from an Acute to a Chronic Pain Model. Pain Physician 2020, 23, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laplante, B.L.; Ketchum, J.M.; Saullo, T.R.; DePalma, M.J. Multivariable analysis of the relationship between pain referral patterns and the source of chronic low back pain. Pain Physician 2012, 15, 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Manchikanti, L.; Pampati, V.; Soin, A.; Vanaparthy, R.; Sanapati, M.R.; Kaye, A.D.; Hirsch, J.A. Trends of Expenditures and Utilization of Facet Joint Interventions in Fee-For-Service (FFS) Medicare Population from 2009-2018. Pain Physician 2020, 23, S129–S147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, D.; Yong, R.J.; Cohen, S.P.; Stojanovic, M.P. Medial Branch Blocks and Radiofrequency Ablation for Low Back Pain from Facet Joints. N Engl J Med 2023, 389, e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.P.; Doshi, T.L.; Kurihara, C.; Dolomisiewicz, E.; Liu, R.C.; Dawson, T.C.; Hager, N.; Durbhakula, S.; Verdun, A.V.; Hodgson, J.A.; et al. Waddell (Nonorganic) Signs and Their Association With Interventional Treatment Outcomes for Low Back Pain. Anesth Analg 2021, 132, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.P.; Hurley, R.W.; Christo, P.J.; Winkley, J.; Mohiuddin, M.M.; Stojanovic, M.P. Clinical predictors of success and failure for lumbar facet radiofrequency denervation. Clin J Pain 2007, 23, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.W.; Pritzlaff, S.; Jung, M.J.; Ghosh, P.; Hagedorn, J.M.; Tate, J.; Scarfo, K.; Strand, N.; Chakravarthy, K.; Sayed, D.; et al. Latest Evidence-Based Application for Radiofrequency Neurotomy (LEARN): Best Practice Guidelines from the American Society of Pain and Neuroscience (ASPN). J Pain Res 2021, 14, 2807–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Liu, B.; Gu, F.; Sima, L. Radiofrequency Denervation on Lumbar Facet Joint Pain in the Elderly: A Randomized Controlled Prospective Trial. Pain Physician 2022, 25, 569–576. [Google Scholar]

- Falco, F.J.; Manchikanti, L.; Datta, S.; Sehgal, N.; Geffert, S.; Onyewu, O.; Zhu, J.; Coubarous, S.; Hameed, M.; Ward, S.P.; et al. An update of the effectiveness of therapeutic lumbar facet joint interventions. Pain Physician 2012, 15, E909–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, M.V.; Colson, J.D.; Sehgal, N.; Dunbar, E.E.; Epter, R. A systematic review of therapeutic facet joint interventions in chronic spinal pain. Pain Physician 2007, 10, 229–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyere, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentov, I.; Kaplan, S.J.; Pham, T.N.; Reed, M.J. Frailty assessment: from clinical to radiological tools. Br J Anaesth 2019, 123, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Baeyens, J.P.; Bauer, J.M.; Boirie, Y.; Cederholm, T.; Landi, F.; Martin, F.C.; Michel, J.P.; Rolland, Y.; Schneider, S.M.; et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing 2010, 39, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, N.; Spolverato, G.; Gupta, R.; Margonis, G.A.; Kim, Y.; Wagner, D.; Rezaee, N.; Weiss, M.J.; Wolfgang, C.L.; Makary, M.M.; et al. Impact Total Psoas Volume on Short- and Long-Term Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Curative Resection for Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: a New Tool to Assess Sarcopenia. J Gastrointest Surg 2015, 19, 1593–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebbeling, L.; Grabo, D.J.; Shashaty, M.; Dua, R.; Sonnad, S.S.; Sims, C.A.; Pascual, J.L.; Schwab, C.W.; Holena, D.N. Psoas:lumbar vertebra index: central sarcopenia independently predicts morbidity in elderly trauma patients. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2014, 40, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinter, Z.W.; Salmons, H.I.t.; Townsley, S.; Omar, A.; Freedman, B.A.; Currier, B.L.; Elder, B.D.; Nassr, A.N.; Bydon, M.; Wagner, S.C.; et al. Multifidus Sarcopenia Is Associated With Worse Patient-reported Outcomes Following Posterior Cervical Decompression and Fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2022, 47, 1426–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodge, G.A.; Goenka, U.; Jajodia, S.; Agarwal, R.; Afzalpurkar, S.; Roy, A.; Goenka, M.K. Psoas Muscle Index: A Simple and Reliable Method of Sarcopenia Assessment on Computed Tomography Scan in Chronic Liver Disease and its Impact on Mortality. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2023, 13, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, T.; Miyake, M.; Hori, S.; Ichikawa, K.; Omori, C.; Iemura, Y.; Owari, T.; Itami, Y.; Nakai, Y.; Anai, S.; et al. Clinical Impact of Sarcopenia and Inflammatory/Nutritional Markers in Patients with Unresectable Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma Treated with Pembrolizumab. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukagoshi, M.; Yokobori, T.; Yajima, T.; Maeno, T.; Shimizu, K.; Mogi, A.; Araki, K.; Harimoto, N.; Shirabe, K.; Kaira, K. Skeletal muscle mass predicts the outcome of nivolumab treatment for non-small cell lung cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99, e19059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Kim, W.Y.; Park, H.K.; Kim, M.C.; Jung, W.; Ko, B.S. Simple Age Specific Cutoff Value for Sarcopenia Evaluated by Computed Tomography. Ann Nutr Metab 2017, 71, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.W.; Koh, W.U.; Kim, H.T.; Ro, Y.J.; Kim, H.J. Low Psoas Lumbar Vertebral Index Is Associated with Mortality after Hip Fracture Surgery in Elderly Patients: A Retrospective Analysis. J Pers Med 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, S.M.; Chae, J.S.; Lee, H.J.; Cho, S.; Im, J. Association of Psoas: Lumbar Vertebral Index (PLVI) with Postherpetic Neuralgia in Patients Aged 60 and Older with Herpes Zoster. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.J.; Kim, C.S.; Kim, S.; Yoon, S.H.; Koh, J.; Kim, Y.K.; Choi, S.S.; Shin, J.W.; Kim, D.H. Association between fatty infiltration in the cervical multifidus and treatment response following cervical interlaminar epidural steroid injection. Korean J Pain 2023, 36, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Park, S.J.; Yoon, K.B.; Jun, E.K.; Cho, J.; Kim, H.J. Influence of Handgrip Strength and Psoas Muscle Index on Analgesic Efficacy of Epidural Steroid Injection in Patients With Degenerative Lumbar Spinal Disease. Pain Physician 2022, 25, E1105–E1113. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J.; Rho, M.; Yoon, K.B.; Jo, M.; Lee, D.W.; Kim, S.H. Influence of cross-sectional area and fat infiltration of paraspinal muscles on analgesic efficacy of epidural steroid injection in elderly patients. Pain Pract 2022, 22, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inose, H.; Yamada, T.; Hirai, T.; Yoshii, T.; Abe, Y.; Okawa, A. The impact of sarcopenia on the results of lumbar spinal surgery. Osteoporos Sarcopenia 2018, 4, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zundert, J.; Mekhail, N.; Vanelderen, P.; van Kleef, M. Diagnostic medial branch blocks before lumbar radiofrequency zygapophysial (facet) joint denervation: benefit or burden? Anesthesiology 2010, 113, 276–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrogowski, J.; Wrzosek, A.; Wordliczek, J. Radiofrequency denervation with or without addition of pentoxifylline or methylprednisolone for chronic lumbar zygapophysial joint pain. Pharmacol Rep 2005, 57, 475–480. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin, R.H.; Turk, D.C.; Wyrwich, K.W.; Beaton, D.; Cleeland, C.S.; Farrar, J.T.; Haythornthwaite, J.A.; Jensen, M.P.; Kerns, R.D.; Ader, D.N.; et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain 2008, 9, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.A.; Kwon, H.J.; Lee, K.; Son, M.G.; Kim, H.; Choi, S.S.; Shin, J.W.; Kim, D.H. Impact of Sarcopenia on Percutaneous Epidural Balloon Neuroplasty in Patients with Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: A Retrospective Analysis. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zager, Y.; Khalilieh, S.; Ganaiem, O.; Gorgov, E.; Horesh, N.; Anteby, R.; Kopylov, U.; Jacoby, H.; Dreznik, Y.; Dori, A.; et al. Low psoas muscle area is associated with postoperative complications in Crohn's disease. Int J Colorectal Dis 2021, 36, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Kim, S.H.; Jo, M.; Jung, H.E.; Bae, J.; Kim, H.J. Evaluation of Paraspinal Muscle Degeneration on Pain Relief after Percutaneous Epidural Adhesiolysis in Patients with Degenerative Lumbar Spinal Disease. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gellhorn, A.C.; Katz, J.N.; Suri, P. Osteoarthritis of the spine: the facet joints. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2013, 9, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, L.; Thoresen, H.; Neckelmann, G.; Furunes, H.; Hellum, C.; Espeland, A. Facet arthropathy evaluation: CT or MRI? Eur Radiol 2019, 29, 4990–4998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.B.; Park, S.W.; Lee, Y.S.; Nam, T.K.; Park, Y.S.; Kim, Y.B. The Effects of Spinopelvic Parameters and Paraspinal Muscle Degeneration on S1 Screw Loosening. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2015, 58, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.A.; Wong, W.S.; Zheng, Y.; Leow, B.H.W.; Low, Y.L.; Tan, L.F.; Teo, K.; Nga, V.D.W.; Yeo, T.T.; Lim, M.J.R. Effect of psoas muscle index on early postoperative outcomes in surgically treated spinal tumours in an Asian population. J Clin Neurosci 2024, 126, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernik, M.N.; Hicks, W.H.; Akbik, O.S.; Nguyen, M.L.; Luu, I.; Traylor, J.I.; Deme, P.R.; Dosselman, L.J.; Hall, K.; Wingfield, S.A.; et al. Psoas Muscle Index as a Predictor of Perioperative Outcomes in Geriatric Patients Undergoing Spine Surgery. Global Spine J 2023, 13, 2016–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourassa-Moreau, E.; Versteeg, A.; Moskven, E.; Charest-Morin, R.; Flexman, A.; Ailon, T.; Dalkilic, T.; Fisher, C.; Dea, N.; Boyd, M.; et al. Sarcopenia, but not frailty, predicts early mortality and adverse events after emergent surgery for metastatic disease of the spine. Spine J 2020, 20, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gakhar, H.; Dhillon, A.; Blackwell, J.; Hussain, K.; Bommireddy, R.; Klezl, Z.; Williams, J. Study investigating the role of skeletal muscle mass estimation in metastatic spinal cord compression. Eur Spine J 2015, 24, 2150–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Zhu, H.; Huang, B.; Li, J.; Liu, G.; Jiao, G.; Chen, G. MRI-based central sarcopenia negatively impacts the therapeutic effectiveness of single-segment lumbar fusion surgery in the elderly. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Liu, J.; Zhu, H.; Wang, J.; Wan, H.; Huang, B.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, G. Lower psoas mass indicates worse prognosis in percutaneous vertebroplasty-treated osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 13880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruffilli, A.; Manzetti, M.; Cerasoli, T.; Barile, F.; Viroli, G.; Traversari, M.; Salamanna, F.; Fini, M.; Faldini, C. Osteopenia and Sarcopenia as Potential Risk Factors for Surgical Site Infection after Posterior Lumbar Fusion: A Retrospective Study. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffilli, A.; Manzetti, M.; Barile, F.; Ialuna, M.; Cerasoli, T.; Viroli, G.; Salamanna, F.; Contartese, D.; Giavaresi, G.; Faldini, C. Complications after Posterior Lumbar Fusion for Degenerative Disc Disease: Sarcopenia and Osteopenia as Independent Risk Factors for Infection and Proximal Junctional Disease. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Xue, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Gao, J.; Mi, J.; Yang, H.; Zhou, F.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J. Impact of Paraspinal Sarcopenia on Clinical Outcomes in Intervertebral Disc Degeneration Patients Following Percutaneous Transforaminal Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy. Orthop Surg 2025, 17, 1332–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Jiang, K.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z. Correlation of the Features of the Lumbar Multifidus Muscle With Facet Joint Osteoarthritis. Orthopedics 2017, 40, e793–e800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbik, O.S.; Al-Adli, N.; Pernik, M.N.; Hicks, W.H.; Hall, K.; Aoun, S.G.; Bagley, C.A. A Comparative Analysis of Frailty, Disability, and Sarcopenia With Patient Characteristics and Outcomes in Adult Spinal Deformity Surgery. Global Spine J 2023, 13, 2345–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, J.C.; Wagner, S.C.; Sebastian, A.; Casper, D.S.; Mangan, J.; Stull, J.; Hilibrand, A.S.; Vaccaro, A.R.; Kepler, C. Sarcopenia does not affect clinical outcomes following lumbar fusion. J Clin Neurosci 2019, 64, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teichtahl, A.J.; Urquhart, D.M.; Wang, Y.; Wluka, A.E.; Wijethilake, P.; O'Sullivan, R.; Cicuttini, F.M. Fat infiltration of paraspinal muscles is associated with low back pain, disability, and structural abnormalities in community-based adults. Spine J 2015, 15, 1593–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markwalder, T.M.; Merat, M. The lumbar and lumbosacral facet-syndrome. Diagnostic measures, surgical treatment and results in 119 patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1994, 128, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, F.; Namdari, B.; Dupler, S.; Kovac, M.F.; Makarova, N.; Dalton, J.E.; Turan, A. No difference in pain reduction after epidural steroid injections in diabetic versus nondiabetic patients: A retrospective cohort study. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2016, 32, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streitberger, K.; Muller, T.; Eichenberger, U.; Trelle, S.; Curatolo, M. Factors determining the success of radiofrequency denervation in lumbar facet joint pain: a prospective study. Eur Spine J 2011, 20, 2160–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Corral, A.; Montori, V.M.; Somers, V.K.; Korinek, J.; Thomas, R.J.; Allison, T.G.; Mookadam, F.; Lopez-Jimenez, F. Association of bodyweight with total mortality and with cardiovascular events in coronary artery disease: a systematic review of cohort studies. Lancet 2006, 368, 666–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.T.; Lee, T.M.; Han, D.S.; Chang, K.V. The Prevalence of Sarcopenia and Its Impact on Clinical Outcomes in Lumbar Degenerative Spine Disease-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalichman, L.; Hunter, D.J. Diagnosis and conservative management of degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. Eur Spine J 2008, 17, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Non-sarcopenia (N = 67) | Sarcopenia (N = 35) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 77.00 [11.00] | 73.00 [10.00] | 0.086 |

| Sex (M/F) | 19 (28.4) / 48 (71.6) | 7 (20.0) / 28 (80.0) | 0.358 |

| Height (cm) | 155.00 [11.00] | 155.00 [8.00] | 0.748 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.00 [4.00] | 22.00 [4.00] | 0.000 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 17 (25.4) | 4 (11.4) | 0.098 |

| Surgery history | 15 (22.4) | 2 (5.7) | 0.032 |

| Compression fracture | 11 (16.4) | 6 (17.1) | 0.926 |

| Spondylolisthesis | 32 (47.8) | 9 (25.7) | 0.031 |

| Duration (months) | 8.00 [19.00] | 14.00 [30.00] | 0.152 |

| Number of levels treated (2 / 3 / 4) | 28 (42) / 36 (54) / 3 (4) | 15 (43) / 18 (51) / 2 (6) | 0.951 |

| Laterality (Left / Right) | 39 (58.2) / 28 (41.8) | 17 (48.6) / 18 (54.4) | 0.353 |

| PLVI | 0.597 ± 0.179 | 0.470 ± 0.154 | 0.001 |

| PSMI (mm²/m²) | |||

| Ipsilateral | 2780.02 [1014.80] | 2388.90 [727.40] | 0.000 |

| Contralateral | 2878.90 [823.10] | 2461.08 [580.41] | 0.000 |

| Variable | Reference group | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 months after RFA | ||||

| Duration | - | 0.982 | 0.961–1.004 | 0.110 |

| Surgery history | No surgery history | 0.246 | 0.065–0933 | 0.039 |

| 6 months after RFA | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | No diabetes mellitus | 0.298 | 0.104–0.853 | 0.024 |

| Surgery history | No surgery history | 0.165 | 0.046–0.589 | 0.006 |

| PMI | - | 1.003 | 1.000–1.006 | 0.042 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).