Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

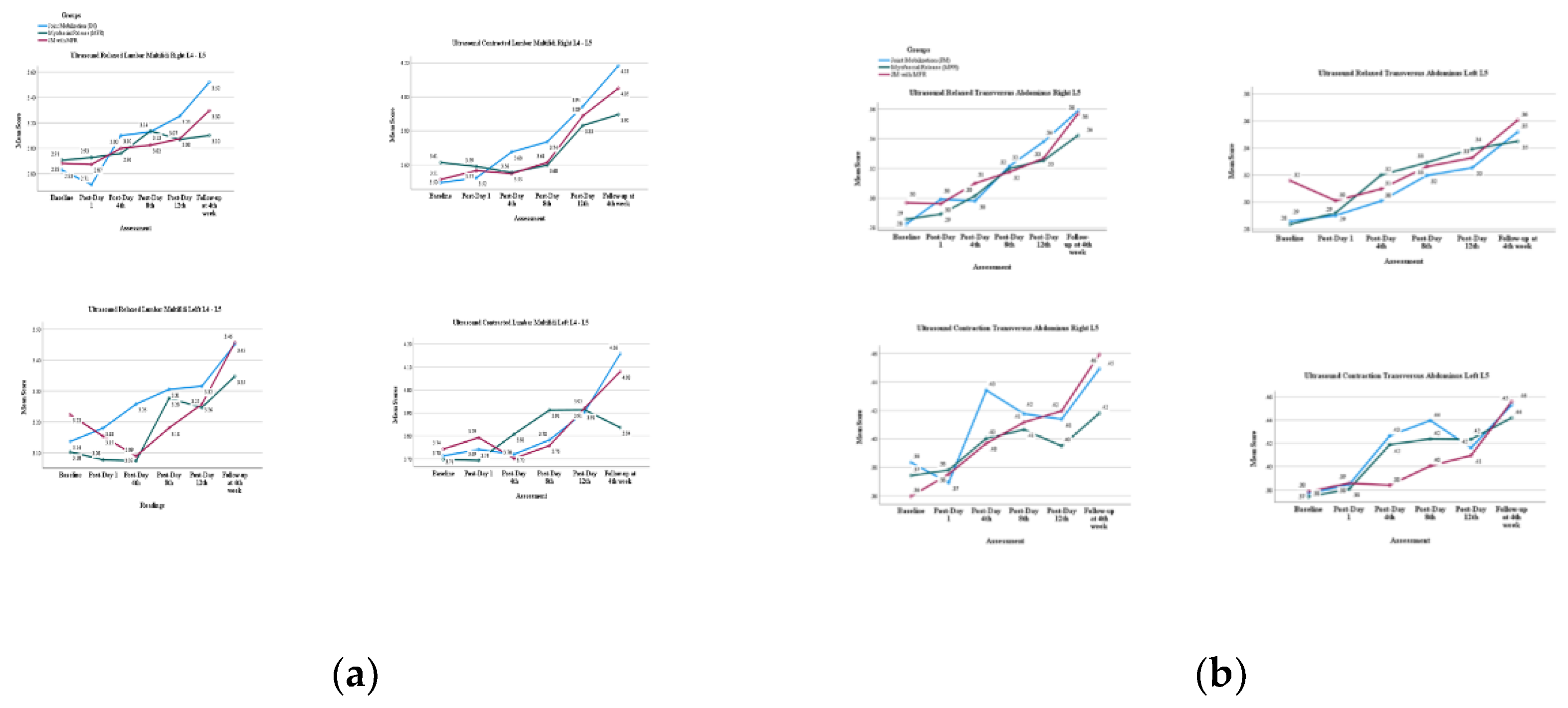

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

| Joint Mobilization (JM) (n= 28) |

Myofascial Release (MFR) (n=27) |

Joint Mobilization with Myofascial Release (JM+MFR) (n=29) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of the patient (years) | 29.07 ± 6.82 | 32.52±10.04 | 28.90±8.47 | 0.212 |

| Height of patient | 167.81 ± 8.12 | 162.10±6.56 | 165.12±8.07 | 0.026 |

| Weight of patient (kg) | 70.05 ± 14.68 | 68.60±13.23 | 65.08±13.53 | 0.382 |

| BMI of patient (kg/m2 ) | 25.09± 4.78 | 26.08±4.53 | 23.90±4.97 | 0.237 |

| Working hour | 9.14±2.90 | 9.33±3.56 | 9.69±4.54 | 0.855 |

| RMDQ 1 | 16.55±4.42 | 15.67±4.63 | 16.31±5.06 | 0.937 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| cLM | Contracting Lumbar Multifidus |

| cTrA | Contracting Transversus Abdominis |

| JM | Joint Mobilization |

| JM+MFR | Joint Mobilization with Myofascial Release |

| L | Left |

| LM | Lumbar Multifidus |

| MFR | Myofascial Release |

| R | Right |

| rLM | Resting Lumbar Multifidus |

| RMDQ | Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire |

| rTrA | Resting Transversus Abdominis |

| TA | Transversus Abdominis |

| USG | Ultrasonography |

References

- Harrianto R. Biomechanical aspects of nonspesific low back pain. Universa Medicina. 2010;29(3):177-87. [CrossRef]

- Meucci RD, Fassa AG, Faria NMX. Prevalence of chronic low back pain: systematic review. Revista de saude publica. 2015;49:73. [CrossRef]

- Myers T, Earls J. Fascial Release for Structural Balance, Revised Edition: Putting the Theory of Anatomy Trains into Practice: North Atlantic Books; 2017.

- Freiwald J, Magni A, Fanlo-Mazas P, Paulino E, Sequeira de Medeiros L, Moretti B, et al. A role for superficial heat therapy in the management of non-specific, mild-to-moderate low back pain in current clinical practice: A narrative review. Life. 2021;11(8):780. [CrossRef]

- Gatton M, Pearcy M, Pettet G, Evans J. A three-dimensional mathematical model of the thoracolumbar fascia and an estimate of its biomechanical effect. J Biomech. 2010;43(14):2792-7. [CrossRef]

- Wilke J, Krause F, Vogt L, Banzer W. What is evidence-based about myofascial chains: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(3):454-61. [CrossRef]

- Ożóg P, Weber-Rajek M, Radzimińska A. Effects of isolated myofascial release therapy in patients with chronic low back pain—A systematic review. J Clin Med. 2023;12(19):6143. [CrossRef]

- Arguisuelas M, Lisón J, Doménech-Fernández J, Martínez-Hurtado I, Coloma PS, Sánchez-Zuriaga D. Effects of myofascial release in erector spinae myoelectric activity and lumbar spine kinematics in non-specific chronic low back pain: Randomized controlled trial. Clin biomech. 2019;63:27-33. [CrossRef]

- Arguisuelas MD, Lisón JF, Sánchez-Zuriaga D, Martínez-Hurtado I, Doménech-Fernández J. Effects of myofascial release in nonspecific chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. Spine. 2017:. [CrossRef]

- Mehyar F, Santos M, Wilson SE, Staggs VS, Sharma NK. Immediate effect of lumbar mobilization on activity of erector spinae and lumbar multifidus muscles. J Chiropr Med. 2017;16(4):271-8. [CrossRef]

- Tamartash H, Bahrpeyma F, Dizaji MM. Effect of remote myofascial release on lumbar elasticity and pain in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: A randomized clinical trial. J Chiropr Med. 2023;22(1):52-9. [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento PR, Costa LO, Araujo AC, Poitras S, Bilodeau M. Effectiveness of interventions for non-specific low back pain in older adults. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy. 2019;105(2):147-62. [CrossRef]

- Sharma C, Sachan K. Exercise Therapy Protocols in Treatment of Non-Specific Low Back Pain-A Literature Review. Indian J Physiother Rehabil. 2024;3(4):204-11.

- Bialosky JE, Bishop MD, Price DD, Robinson ME, George SZ. The mechanisms of manual therapy in the treatment of musculoskeletal pain: a comprehensive model. Man Ther. 2009;14(5):531-8. [CrossRef]

- Lin C-F, Jankaew A, Tsai M-C, Liao J-C. Immediate effects of thoracic mobilization versus soft tissue release on trunk motion, pain, and lumbar muscle activity in patients with chronic low back pain. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2024;40:1664-71. [CrossRef]

- Fagundes Loss J, de Souza da Silva L, Ferreira Miranda I, Groisman S, Santiago Wagner Neto E, Souza C, et al. Immediate effects of a lumbar spine manipulation on pain sensitivity and postural control in individuals with nonspecific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Chiropr Man Therap. 2020;28:1-10. [CrossRef]

- Outeda LR, Cousiño LAJ, Carrera IdC, Caeiro EML. Effect of the maitland concept techniques on low back pain: a systematic review. Coluna. 2022;21(2):e258429. [CrossRef]

- Furlan AD, Yazdi F, Tsertsvadze A, Gross A, Van Tulder M, Santaguida L, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and safety of selected complementary and alternative medicine for neck and low-back pain. EBCAM. 2012;2012(1):953139. [CrossRef]

- Bronfort G, Haas M, Evans RL, Bouter LM. Efficacy of spinal manipulation and mobilization for low back pain and neck pain: a systematic review and best evidence synthesis. Spine J. 2004;4(3):335-56. [CrossRef]

- Manheim C. The myofascial release manual. 4 ed: Taylor & Francis; 2024.

- Tozzi P, Bongiorno D, Vitturini C. Fascial release effects on patients with non-specific cervical or lumbar pain. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2011;15(4):405-16. [CrossRef]

- Ożóg P, Weber-Rajek M, Radzimińska A, Goch A. Analysis of muscle activity following the application of myofascial release techniques for low-back pain—a randomized-controlled trial. J Clin Med. 2021;10(18):4039. [CrossRef]

- Langevin HM, Konofagou EE, Badger GJ, Churchill DL, Fox JR, Ophir J, et al. Tissue displacements during acupuncture using ultrasound elastography techniques. Ultrasound Med Biol 2004;30(9):1173-83. [CrossRef]

- Tamartash H, Bahrpeyma F, Dizaji MM. Effect of Myofascial Release Technique on Lumbar Fascia Thickness and Low Back Pain: A Clinical Trial. J Mod Rehabil. 2022;16(3):244-51. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y-H, Chai H-M, Shau Y-W, Wang C-L, Wang S-F. Increased sliding of transverse abdominis during contraction after myofascial release in patients with chronic low back pain. Man ther. 2016;23:69-75. [CrossRef]

- Lopez P, Radaelli R, Taaffe DR, Newton RU, Galvão DA, Trajano GS, et al. Resistance training load effects on muscle hypertrophy and strength gain: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2020;53(6):1206. [CrossRef]

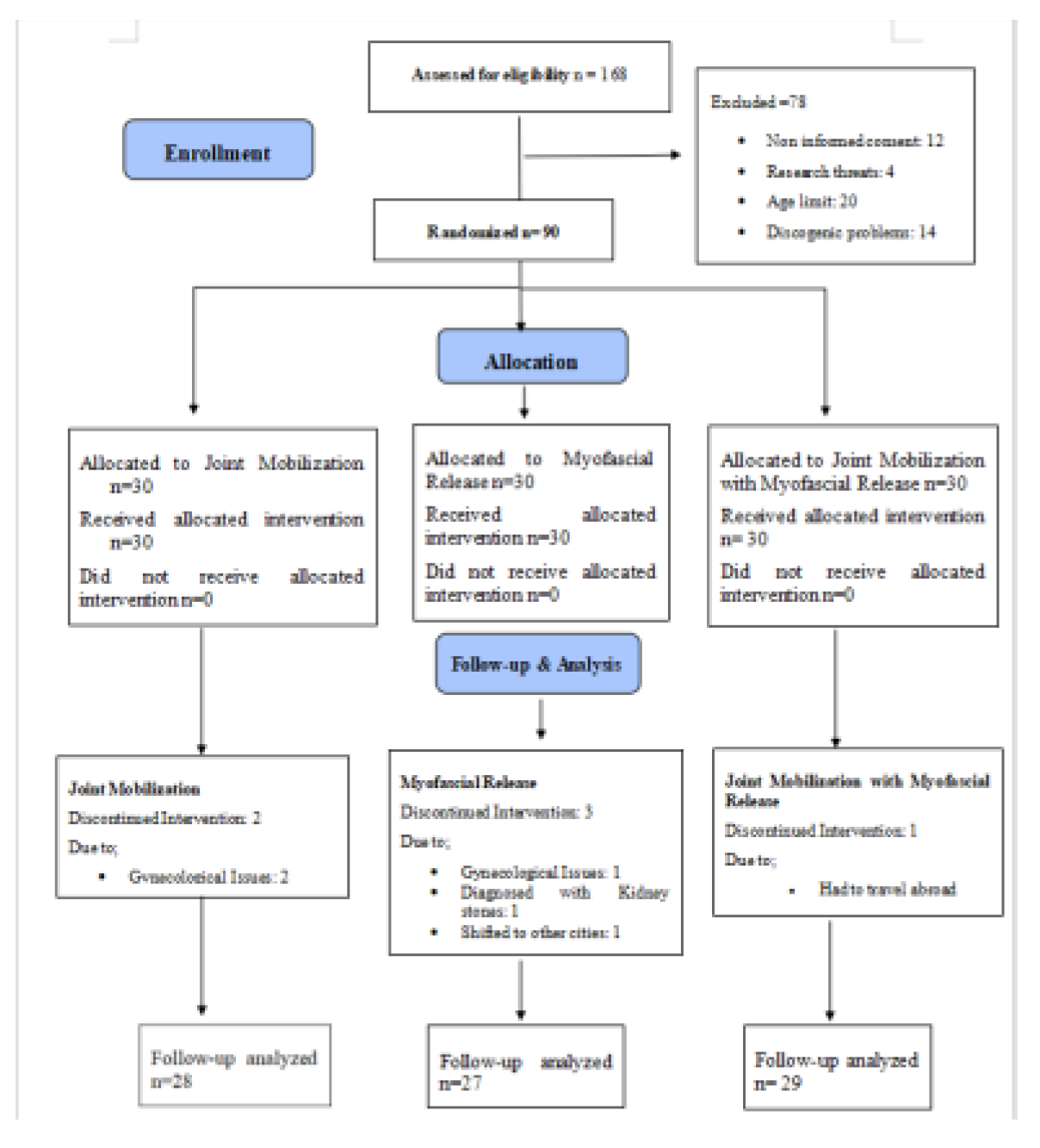

- Ngamjarus C. n4Studies: sample size calculation for an epidemiological study on a smart device. Siriraj Med J. 2016;68(3):160-70.

- Hussein DAMM, Choy APCY, Singh DD, Cardosa DMS, Mansor PM, Hasnan DN, et al. Malaysian Low Back Pain Management Guideline [Available from: https://www.masp.org.my/index.cfm?&menuid=23.

- Payares K, Lugo LH, Restrepo A. Validation of the Roland Morris questionnaire in Colombia to evaluate disability in low back pain. Spine. 2015;40(14):1108-14. [CrossRef]

- Koppenhaver SL, Hebert JJ, Fritz JM, Parent EC, Teyhen DS, Magel JS. Reliability of rehabilitative ultrasound imaging of the transversus abdominis and lumbar multifidus muscles. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(1):87-94. [CrossRef]

- Ruxton G. Allocation concealment as a potentially useful aspect of randomised experiments. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2017;71:1-3. [CrossRef]

- Narouei S, hossein Barati A, hossein Alizadeh M, Akbari A, Ghiasi F. Intrarater reliability of rehabilitative ultrasound imaging of the gluteus maximus, lumbar multifidus and transversus abdominis muscles in healthy subjects. Sport Sci 2016;1(1-2016):1-11.

- Hengeveld E, Banks K. Maitland's Vertebral Manipulation: Management of Neuromusculoskeletal Disorders-Volume 1: Health Sci; 2013.

- Barnes MF. The basic science of myofascial release: morphologic change in connective tissue. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 1997;1(4):231-8.

- Hicks GE, Simonsick EM, Harris TB, Newman AB, Weiner DK, Nevitt MA, et al. Trunk muscle composition as a predictor of reduced functional capacity in the health, aging and body composition study: the moderating role of back pain. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(11):1420-4. [CrossRef]

- Choi W, Lee J, Lee S. Effects of lumbar joint mobilization on trunk function, postural balance, and gait in patients with chronic stroke: A randomized pilot study. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2023;36(1):79-86. [CrossRef]

- Ajimsha M, Al-Mudahka NR, Al-Madzhar J. Effectiveness of myofascial release: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2015;19(1):102-12.

- Azadinia F, Takamjani IE, Kamyab M, Kalbassi G, Sarrafzadeh J, Parnianpour M. The effect of lumbosacral orthosis on the thickness of deep trunk muscles using ultrasound imaging: A randomized controlled trial in patients with chronic low back pain. Am J Phys Med. 2019;98(7):536-44.

- Lin C-F, Jankaew A, Tsai M-C, Liao J-C. Immediate effects of thoracic mobilization versus soft tissue release on trunk motion, pain, and lumbar muscle activity in patients with chronic low back pain. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2024;40:1664-71.

- Shah YK. The effects of myofascial manual therapy on muscle activity and blood flow in people with low back pain: University of Kent (United Kingdom); 2017.

- Brenner AK, Gill NW, Buscema CJ, Kiesel K. Improved activation of lumbar multifidus following spinal manipulation: a case report applying rehabilitative ultrasound imaging. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37(10):613-9. [CrossRef]

- Kirsebom O, Jones S, Strömberg D, Martínez-Pinedo G, Langanke K, Röpke F, et al. This is a self-archived version of an original article. This version may differ from the original in pagination and typographic details. Phys Rev Lett. 2019;123:262701. [CrossRef]

- Mikołajowski G, Pałac M, Wolny T, Linek P. Lateral abdominal muscles shear modulus and thickness measurements under controlled ultrasound probe compression by external force sensor: a comparison and reliability study. Sensors. 2021;21(12):4036. [CrossRef]

- Tsartsapakis I, Bagioka I, Fountoukidou F, Kellis E. A Comparison between Core Stability Exercises and Muscle Thickness Using Two Different Activation Maneuvers. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2024;9(2):70.

- Myers TW. Anatomy trains: myofascial meridians for manual and movement therapists: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2009.

- Bohunicky S, Rutherford L, Harrison K-L, Malone Q, Glazebrook CM, Scribbans TD. Immediate effects of myofascial release to the pectoral fascia on posture, range of motion, and muscle excitation: a crossover randomized clinical trial. J Man Manip Ther. 2024:1-11. [CrossRef]

- Pfluegler G, Kasper J, Luedtke K. The immediate effects of passive joint mobilisation on local muscle function. A systematic review of the literature. Musculoskeletal Sci Pract. 2020;45:102106. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Hodges PW. Changes in recruitment of the abdominal muscles in people with low back pain: ultrasound measurement of muscle activity. Spine. 2004;29(22):2560-6. [CrossRef]

- Hides J, Stanton W, McMahon S, Sims K, Richardson C. Effect of stabilization training on multifidus muscle cross-sectional area among young elite cricketers with low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(3):101-8.

- Nourbakhsh MR, Arab AM. Relationship between mechanical factors and incidence of low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2002;32(9):447-60. [CrossRef]

- De Martino E, Hides J, Elliott JM, Hoggarth M, Zange J, Lindsay K, et al. Lumbar muscle atrophy and increased relative intramuscular lipid concentration are not mitigated by daily artificial gravity after 60-day head-down tilt bed rest. J Appl Physiol. 2021;131(1):356-68. [CrossRef]

- Puentedura EJ, Landers MR, Hurt K, Meissner M, Mills J, Young D. Immediate effects of lumbar spine manipulation on the resting and contraction thickness of transversus abdominis in asymptomatic individuals. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41(1):13-21. [CrossRef]

- Ciccotelli J. Lumbopelvic Biomechanics and Muscle Performance in Individuals with Unilateral Transfemoral Amputation: Implications for Lower Back Pain: University of Nevada, Las Vegas; 2023.

- Barker PJ, Guggenheimer KT, Grkovic I, Briggs CA, Jones DC, Thomas CDL, et al. Effects of tensioning the lumbar fasciae on segmental stiffness during flexion and extension: Young Investigator Award winner. Spine. 2006;31(4):397-405. [CrossRef]

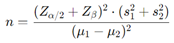

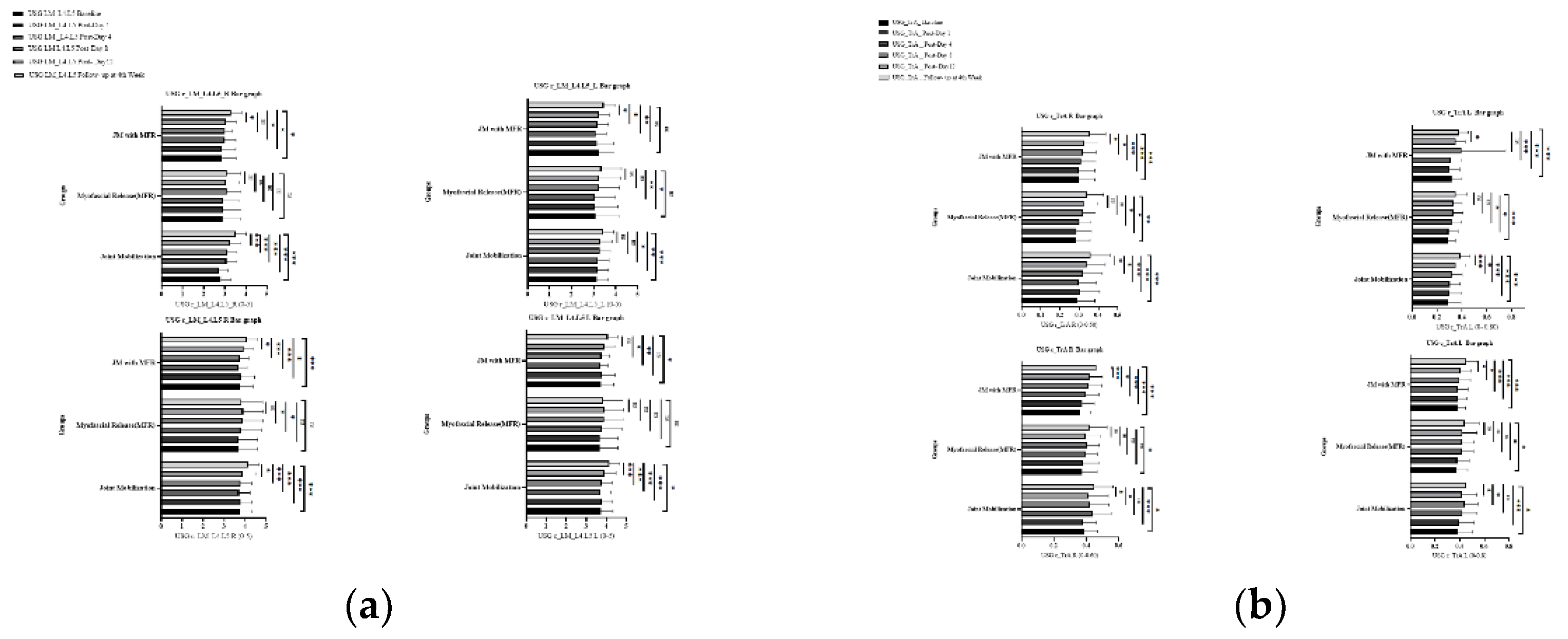

| Assessment | RM-ANOVA | Time main effect | Group Main effect | Time *Group interaction effect | |||||||||||||

| Groups | Baseline | Post-Day 1 | Post-Day 4th | Post-Day 8th | Post-Day 12th | Follow-up in 4th week | Sig. | F-value (Effect Size) | Sig. | F-value (Effect Size) | Sig. | F-value (Effect Size) | Sig. | ||||

| USG2 | rTrA | R | L5 | JM | 0.28±0.09 | 0.31±-0.10 | 0.30±0.09 | 0.32±0.10 | 0.34±0.10 | 0.36±0.10 | 0.001 | 19.57 (0.207) | 0.000 | 0.244 (0.006) | 0.784 | 0.36 (0.009) | 0.904 |

| MFR | 0.28±0.07 | 0.29±0.08 | 0.30±0.06 | 0.32±0.06 | 0.33±0.07 | 0.34±0.08 | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| JM+MFR | 0.29±0.08 | 0.30±0.09 | 0.31±0.08 | 0.32±0.70 | 0.33±0.07 | 0.35±0.08 | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Sig. | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.82 | 0.97 | 0.82 | 0.76 | |||||||||||

| L | JM | 0.28 ±0.09 | 0.30±0.10 | 0.30±0.08 | 0.32±0.08 | 0.33±0.08 | 0.35 ±0.07 | 0.001 | 43.76 (0.369) | 0.016 | 0.273 (0.034) | 0.273 | 0.39 (0.10) | 0.646 | |||

| MFR | 0.28 ±0.06 | 0.29±0.08 | 0.32±0.08 | 0.33±0.08 | 0.34±0.35 | 0.34 ±0.09 | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| JM+MFR | 0.32 ±0.08 | 0.30±0.08 | 0.31±0.08 | 0.40±0.35 | 0.33±0.08 | 0.36 ±0.07 | 0.227 | ||||||||||

| Sig. | 0.30 | 0.92 | 0.72 | 0.37 | 0.82 | 0.75 | |||||||||||

| cTrA | R | L5 | JM | 0.38±0.08 | 0.38±0.09 | 0.44±0.11 | 0.42±0.12 | 0.41±0.12 | 0.44±0.11 | 0.001 | 17.19 (0.186) | 0.000 | 0.229 (0.006) | 0.796 | 1.33 (0.034) | 0.235 | |

| MFR | 0.37±0.09 | 0.38±0.10 | 0.40±0.70 | 0.41±0.07 | 0.40±0.10 | 0.41±0.10 | 0.090 | ||||||||||

| JM+MFR | 0.35±0.06 | 0.38±0.07 | 0.40±0.08 | 0.41±0.08 | 0.42±0.08 | 0.45±0.09 | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Sig. | 0.44 | 0.99 | 0.15 | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.33 | |||||||||||

| L | JM | 0.37 ±0.12 | 0.39±0.13 | 0.42±0.12 | 0.44±0.11 | 0.42±0.12 | 0.45 ±0.11 | 0.008 | 17.69 (0.191) | 0.221 | 0.056 (0.001) | 0.936 | 1.12 (0.029) | 0.350 | |||

| MFR | 0.37±0.09 | 0.38±0.10 | 0.42±0.10 | 0.42±0.10 | 0.42±0.12 | 0.44 ±0.12 | 0.004 | ||||||||||

| JM+MFR | 0.37 ±0.06 | 0.39±0.07 | 0.38±0.08 | 0.40±0.09 | 0.41±0.08 | 0.45 ±0.09 | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Sig. | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.89 | 0.87 | |||||||||||

| rLM | R | L4.L5 | JM | 3.52±0.54 | 2.73±0.43 | 3.08±0.50 | 3.12±0.47 | 3.25±0.53 | 4.18±0.58 | 0.001 | 1.52 (0.020) | 0.001 | 1.490 (0.038) | 0.232 | 1.49 (0.038) | 0.231 | |

| MFR | 3.59±0.84 | 2.92±0.88 | 2.92±0.73 | 3.10±0.69 | 3.07±0.59 | 3.89±0.76 | 0.265 | ||||||||||

| JM+MFR | 3.51±0.55 | 2.87±0.64 | 3.00±0.52 | 3.02±0.35 | 3.08±0.47 | 4.05±0.53 | 0.008 | ||||||||||

| Sig. | 0.92 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.03 | |||||||||||

| L | JM | 3.14 ±0.53 | 3.18±0.49 | 3.21±0.49 | 3.28±0.47 | 3.32±0.52 | 3.45 ±0.47 | 0.047 | 6.34 (0.078) | 0.001 | 0.288 (0.008) | 0.751 | 0.846 (0.015) | 0.736 | |||

| MFR | 3.07 ±1.06 | 3.05±1.05 | 3.05±0.94 | 3.24±0.92 | 3.25±0.97 | 3.35 ±0.91 | 0.063 | ||||||||||

| JM+MFR | 3.22 ±0.72 | 3.15±0.75 | 3.10±0.49 | 3.18±0.48 | 3.26±0.45 | 3.45 ±0.53 | 0.093 | ||||||||||

| Sig. | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.83 | 0.92 | 0.79 | |||||||||||

| cLM | R | L4.L5 | JM | 3.53±0.54 | 3.56±0.49 | 3.68±0.48 | 3.74±0.51 | 3.95±0.66 | 4.18±0.59 | 0.001 | 17.98 (0.193) | 0.000 | 0.316 (0.008) | 0.730 | 1.01 (0.026) | 0.417 | |

| MFR | 3.59±0.84 | 3.58±0.85 | 3.52±0.81 | 3.55±0.81 | 3.83±0.70 | 3.89±0.76 | 0.063 | ||||||||||

| JM+MFR | 3.51±0.55 | 3.57±0.58 | 3.55±0.43 | 3.61±0.44 | 3.89±0.40 | 4.05±0.53 | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Sig. | 0.87 | 0.99 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.79 | 0.26 | |||||||||||

| L | JM | 3.74 ±0.58 | 3.78±0.54 | 3.71±0.53 | 3.78±0.52 | 3.91±0.58 | 4.16 ±0.51 | 0.003 | 6.19 (0.76) | 0.001 | 0.239 (0.003) | 0.890 | 1.102 (0.029) | 0.360 | |||

| MFR | 3.68 ±0.89 | 3.68±0.91 | 3.80±0.97 | 3.88±0.95 | 3.91±0.95 | 3.82 ±0.98 | 0.287 | ||||||||||

| JM+MFR | 3.74 ±0.63 | 3.79±0.65 | 3.70±0.38 | 3.76±0.42 | 3.92±0.49 | 4.10 ±0.48 | 0.037 | ||||||||||

| Sig. | 0.94 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.99 | 0.22 | |||||||||||

| Percentage change | Multiple Comparison Test -Mean Difference with significance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JOINT MOBILIZATION (JM) | MYOFASCIAL RELEASE (MFR) | JOINT MOBILIZATION with MYOFASCIAL RELEASE (JM+MFR) | (JM) vs (MFR) | (JM) vs (JM+MFR) | (MFR) vs (JM+MFR) | ||||

| Mean ± S.D | M.D (Sig.) | ||||||||

| USG 3 | rTrA | R | L5 | 21.4±28.3 | 34.9±29.8 | 33.0±35.5 | 0.006 (1.00) | -0.0010 (1.00) | -0.0067 (1.00) |

| L | 32.49±51.28 | 30.27±34.55 | 25.19±33.59 | -0.0059 (1.00) | -0.0236 (0.62) | -0.0177 (1.00) | |||

| cTrA | R | L5 | 18.6±24.2 | 25.4±29.7 | 22.9±31.2 | 0.016 (1.00) | 0.0075 (1.00) | -0.0084 (1.00) | |

| L | 29.56±37.45 | 29.03±32.43 | 22.72±26.95 | 0.0056 (1.00) | 0.0137 (1.00) | 0.0081 (1.00) | |||

| rLM | R | L4.L5 | 22.9±26.1 | 18.9±33.0 | 21.9±28.5 | 0.075 (1.00) | -0.066 (0.87) | -0.0087 (0.99) | |

| L | 12.36±17.56 | 13.47±29.08 | 13.40±30.76 | 0.087 (1.00) | 0.0476 (1.00) | -0.039 (1.00) | |||

| cLM | R | L4.L5 | 15.6±20.6 | 20.9±31.0 | 18.2±22.9 | 0.078 (1.00) | 0.063 (1.00) | -0.016 (1.00) | |

| L | 13.56±22.04 | 7.65±20.99 | 1.85±24.51 | 0.026 (1.00) | 0.004 (1.00) | -0.023 (1.00) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).