1. Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) is a systemic, immune-mediated, multifactorial disorder triggered by the ingestion of gluten and related prolamins in genetically predisposed individuals [

1]. This disorder affects more than 7 million people in Europe, with a higher prevalence in women, with an estimated incidence of 17,4 cases per 100.000 women compared to 7,8 per 100.000 men [

2]. CD is one of the few chronic diseases where the genetic component (HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8), the implicated autoantigen (tissue transglutaminase, tTG), and the environmental trigger (gluten) have been clearly identified [

3].

Although CD has a strong hereditary component, with a familial recurrence rate of 10-15%, only 2-3% of individuals carrying the predisposition genes develop the disease, despite more than 30% of the global population carrying these genes and being exposed to gluten. This indicates that additional environmental factors are critical in its development [

4]. Research studies such as the TEDDY, EAT, and PRO-FILE studies have identified risk factors such as early viral infections (e.g., rotavirus), early introduction of gluten into the diet, and the use of antibiotics, which can alter the gut microbiota and increase susceptibility to CD [

5].

Gluten, a storage protein found primarily in wheat, constitutes between 80% and 85% of the total protein in this cereal. Its most relevant fraction, gliadin, is resistant to complete digestion by gastric, pancreatic, and intestinal enzymes, generating large peptide fragments (up to 33 amino acids) in the small intestine that can trigger immune responses in genetically predisposed individuals [

6]. Currently, the only effective therapeutic strategy for CD patients is strict adherence to a lifelong gluten-free diet (GFD) [

7].

Numerous studies have shown that a GFD significantly improves the quality of life of celiac patients, reduces clinical symptoms, and prevents long-term complications. For example, Borghini et al. [

8] reported improvements in nutrient absorption and a reduction in serum inflammatory markers in patients who strictly followed this diet. Similarly, Poslt Königová et al. [

9] indicated that a GFD reduces the risk of autoimmune complications and malignancies associated with CD, while Aljada et al. [

10] high-lighted its role in preventing malnutrition, peripheral neuropathy, and other severe complications.

The gut microbiota, an ecosystem composed of approximately 100 trillion microorganisms, plays essential roles in human health, with alterations implicated in the development and progression of CD [

11]. Key roles include the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate, compounds generated by genera like

Prevotella, which are crucial for maintaining a proper pH and possess anti-inflammatory properties [

12,

13]. In CD patients, dysbiosis may decrease SCFA production, contributing to inflammatory processes and exacerbating symptoms [

13,

14]. Additionally, genera like

Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus synthesize essential vitamins, whose deficiency is common in the dysbiosis associated with CD.

The microbiota also plays a role in protecting against pathogens by competing for nutrients and space, as well as generating bacteriocins with antimicrobial activity. Bacteria like

Akkermansia muciniphila and

Lactobacillus are essential in this function, which is affected in CD patients, increasing susceptibility to infections [

15,

16,

17]. Moreover, genera like

Bacteroides and

Enterococcus participate in immune regulation, preventing excessive inflammation and autoimmune processes, while

Akkermansia muciniphila contributes to mucus production, reinforcing the integrity of the intestinal barrier and limiting the entry of antigens and bacteria into the bloodstream [

18,

19,

20]. In CD, these functions are compromised, exacerbating inflammation and intestinal damage.

Amplicon metagenomics has revolutionized the study of gut microbial communities, allowing detailed exploration of bacterial diversity in various conditions, such as CD. This approach provides precise information about the composition through the analysis of specific DNA regions, such as

16S rRNA. This technique has proven essential for understanding how dietary and other factors can alter the gut microbiota [

21].

On the other hand, the functional diversity of the gut microbiota is a key concept in microbial stability and usually is evaluated using tools like BIOLOG. Functional diversity implies that different bacterial species can carry out similar metabolic functions, ensuring the maintenance of intestinal health even in the face of alterations in bacterial composition. This is especially important in the context of diseases like CD, where dietary or environmental changes can affect the microbiota and its functionality.

Another relevant aspect is the study of microbial communities as biomarkers and potential reservoirs of resistance genes. Gut bacteria can harbor these genes and transfer them to other strains, thereby increasing the spread of resistance mechanisms. This information is crucial for predicting how clinical interventions, such as dietary changes or the use of antibiotics, can influence antimicrobial resistance [

22].

This study aims to determine the impact of a prolonged GFD on the gut microbiota in women with CD, compared to healthy women on a standard diet, addressing aspects such as functional and taxonomic diversity and their response to clinically used antibiotics. These approaches may help to understand how adherence to a GFD may modify the gut microbiota, influencing the pathogenesis of CD, intestinal immune regulation, and interaction with antimicrobial treatments [

11,

13].

3. Discussion

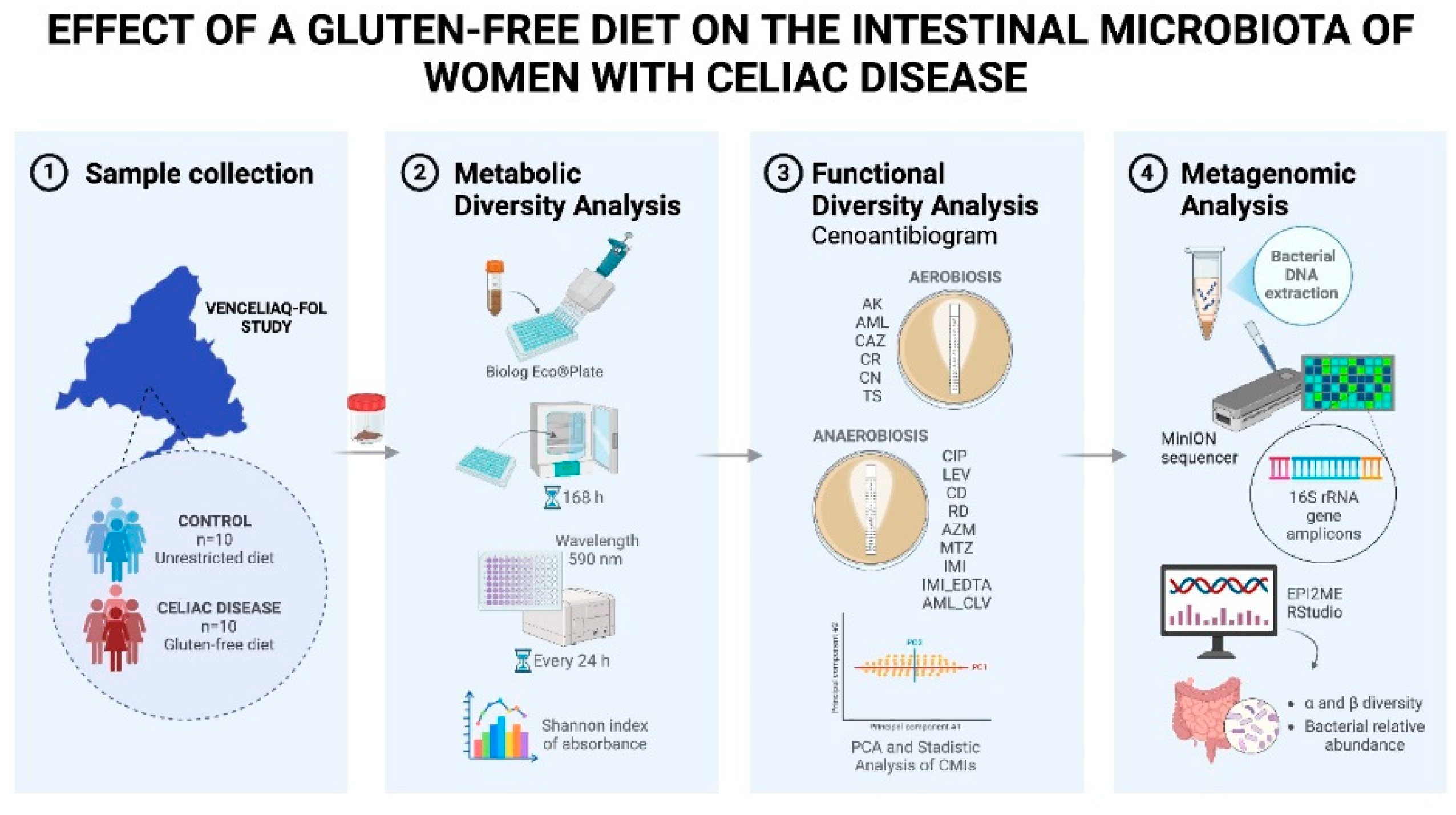

The impact of a gluten-free diet (GFD) on gut microbiota was evaluated by studying 10 women diagnosed with celiac disease (CD) who had been following a GFD for over a year, compared to a control group of 10 women on a normal diet. This comprehensive approach provided a deeper understanding of the microbial changes induced by the GFD, offering valuable insights into the interaction and functioning of gut bacteria. Although the GFD is essential for managing CD it has been debated in several studies [

10,

23] due to its fiber deficiency, especially soluble fibers like beta-glucans (found in barley), and certain types of resistant starch, because of the exclusion of whole grains and some fiber-rich vegetables. In this context, there is evidence linking a reduced intake of certain types of dietary fiber required for bacterial fermentation and the production of SCFAs like butyrate and propionate to a reduced functional capacity of the microbiota. However, our results suggest that women with CD can maintain intestinal microbial functionality similar to women on a normal diet.

Similarly, the results related to functional diversity, particularly in substrate transformation capabilities, showed no significant differences between the two study groups. This suggests that the bacterial communities of both groups have the capacity to utilize a variety of substrates similarly, indicating that dietary composition has a similar effect on individuals with different sensitivities to gluten when both groups have not been exposed to the allergen [

24]. A recent study by Melini and Melini [

25] showed that a GFD can be nutritionally adequate if it includes fiber-rich foods such as fruits, vegetables, legumes, and pseudocereals like quinoa or amaranth. These sources can compensate for the lack of fiber typically found in gluten-containing grains, supporting the idea that a well-planned GFD does not necessarily result in lower fiber intake and, therefore, a lower functionality of the microbiota [

26].

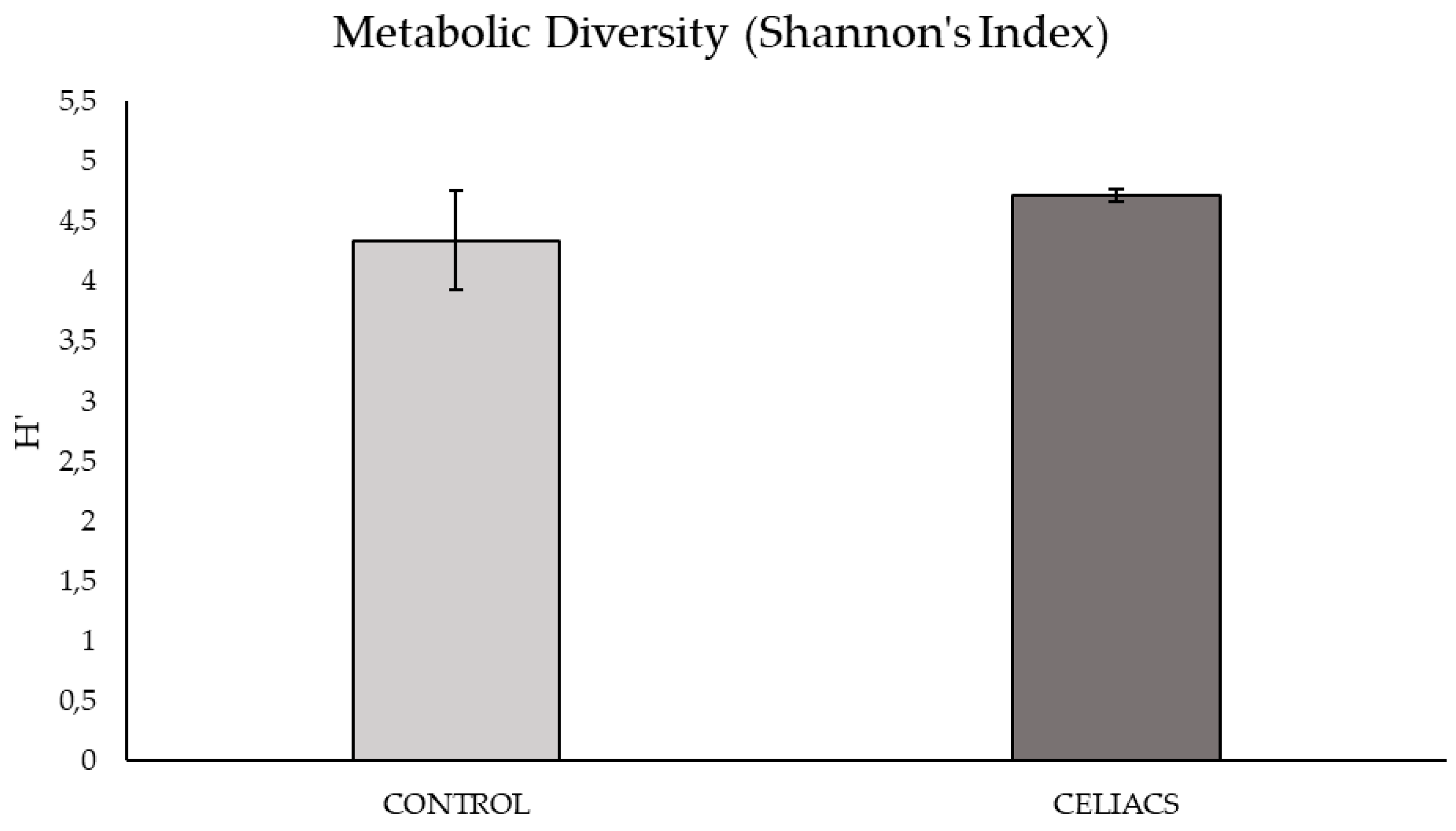

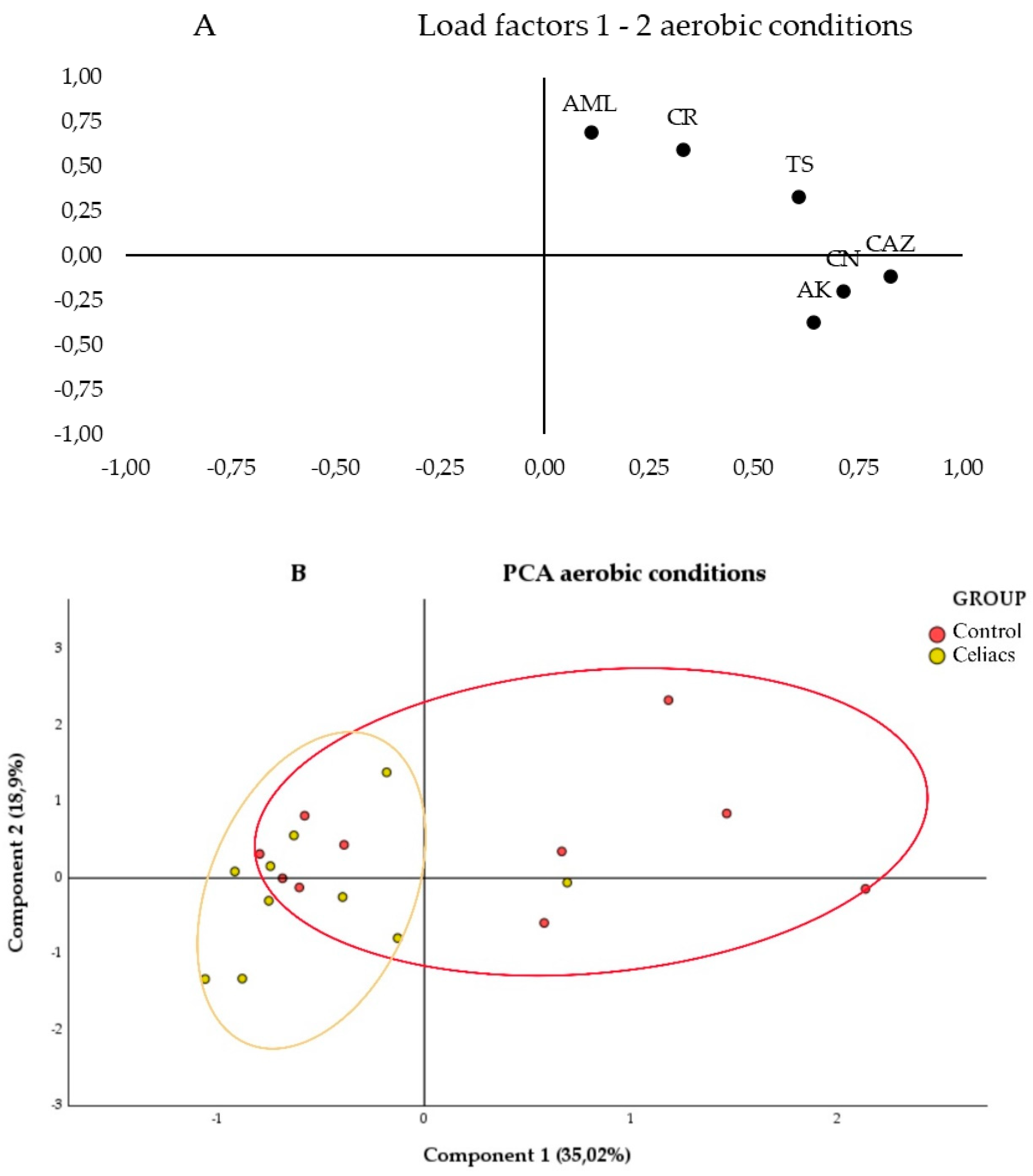

The intestine may act as a reservoir for molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. There is significant scientific interest in understanding the impact of diet on the preservation or control of the spread of resistance mechanisms shared by intestinal microbial communities. In this regard, the technique of the "cenoantibiogram", defined as the analysis of the bacterial community’s response to antibiotics, does not aim to characterize each of the different mechanisms explaining the community’s response to antibiotics but rather to assess the overall phenotypic behavior of the intestinal microbial community. In this context, the bacterial community of women with CD showed very homogeneous behavior both in aerobic conditions and in the absence of oxygen, with lower minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) to all tested antibiotics. These results suggest that prolonged adherence to a GFD in women with CD, compared to the control group, could influence the decrease in MICs to certain antibiotics. Conversely, in the control group’s bacterial community, there was a more heterogeneous antibiotic response in each sample, which suggests that a less restrictive diet may favor the proliferation of fast-growing bacteria, resulting in higher MICs.

Some studies [

27,

28] suggest that ultra-processed foods (UPFs), many of which are rich in gluten and not included in a GFD, contain simple carbohydrates. These simple sugars may favor the growth of fast-growing bacteria capable of proliferating rapidly due to the high availability of sugars. Fast-growing bacteria represent a significant public health challenge because of their ability to quickly develop and spread multiple antibiotic resistance mechanisms. Their high reproduction rates, horizontal gene transfer, biofilm formation, and rapid adaptation to antibiotic stress are key factors contributing to this problem [

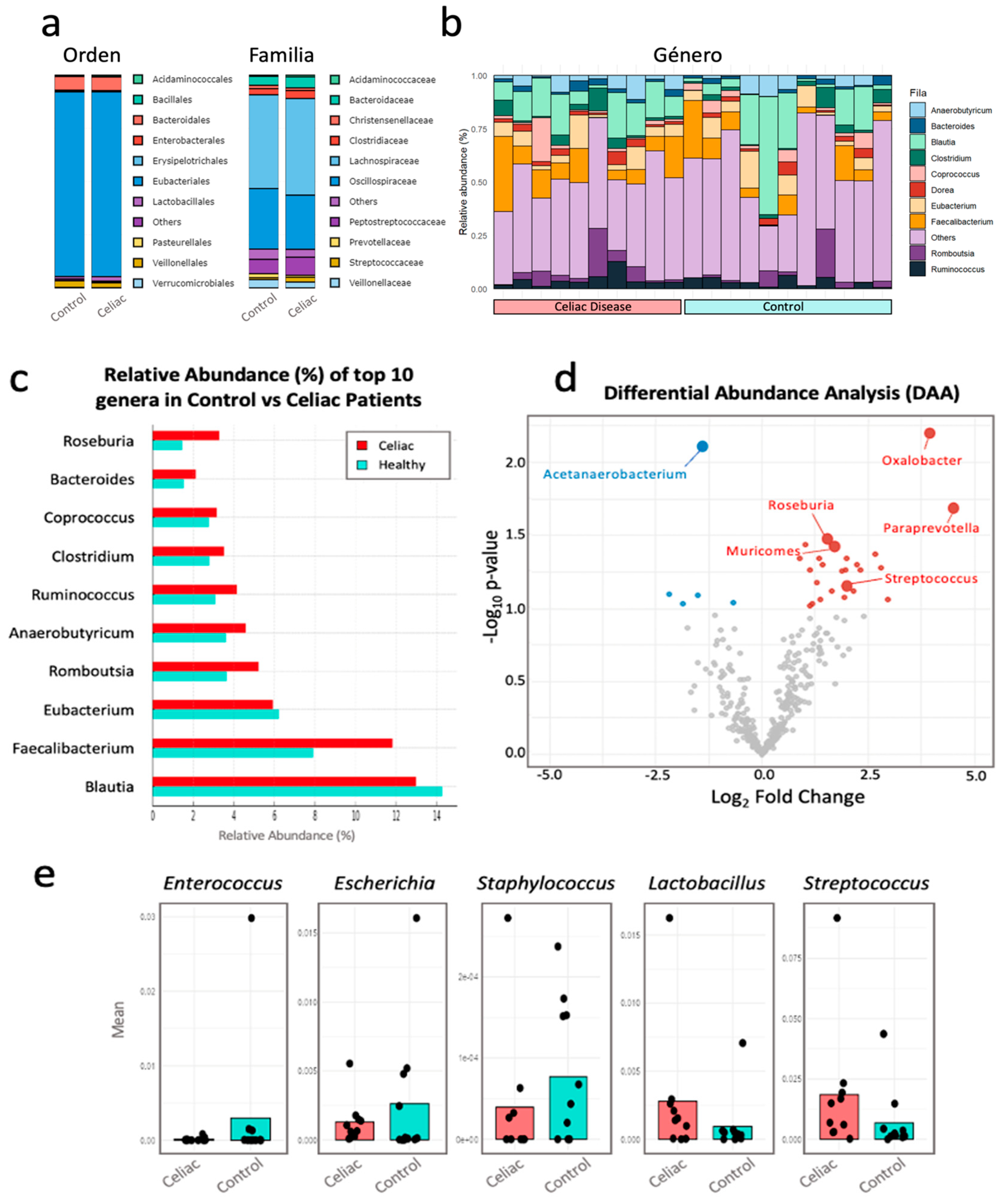

29]. Therefore, this observation could suggest that reducing the intake of these simple carbohydrates in GFDs could limit the growth of these bacteria, reducing MICs in the intestinal microbiota of celiac patients. When comparing metagenomic data, we observed a higher proportion of cultivable fast-growing bacteria, such as

Escherichia,

Enterococcus, and

Staphylococcus, in the microbiota of the control women compared to the women with celiac disease. These data support the hypothesis that adherence to a stricter GFD, compared to a normal diet, could lead to lower MICs for antibiotics and possibly lower proliferation of fast-growing bacteria.

However, inherent difficulties in studying the intestinal microbiota and challenges in obtaining consistent results necessitate further studies to clarify these preliminary findings. Furthermore, standardizing protocols for bacterial DNA extraction from fecal samples and the subsequent bioinformatics processing of the obtained data can facilitate better interpretation of results across research studies [

30,

31]. There is a high scientific consensus stating that Gram-positive bacteria present more difficulty in lysis and proper DNA extraction [

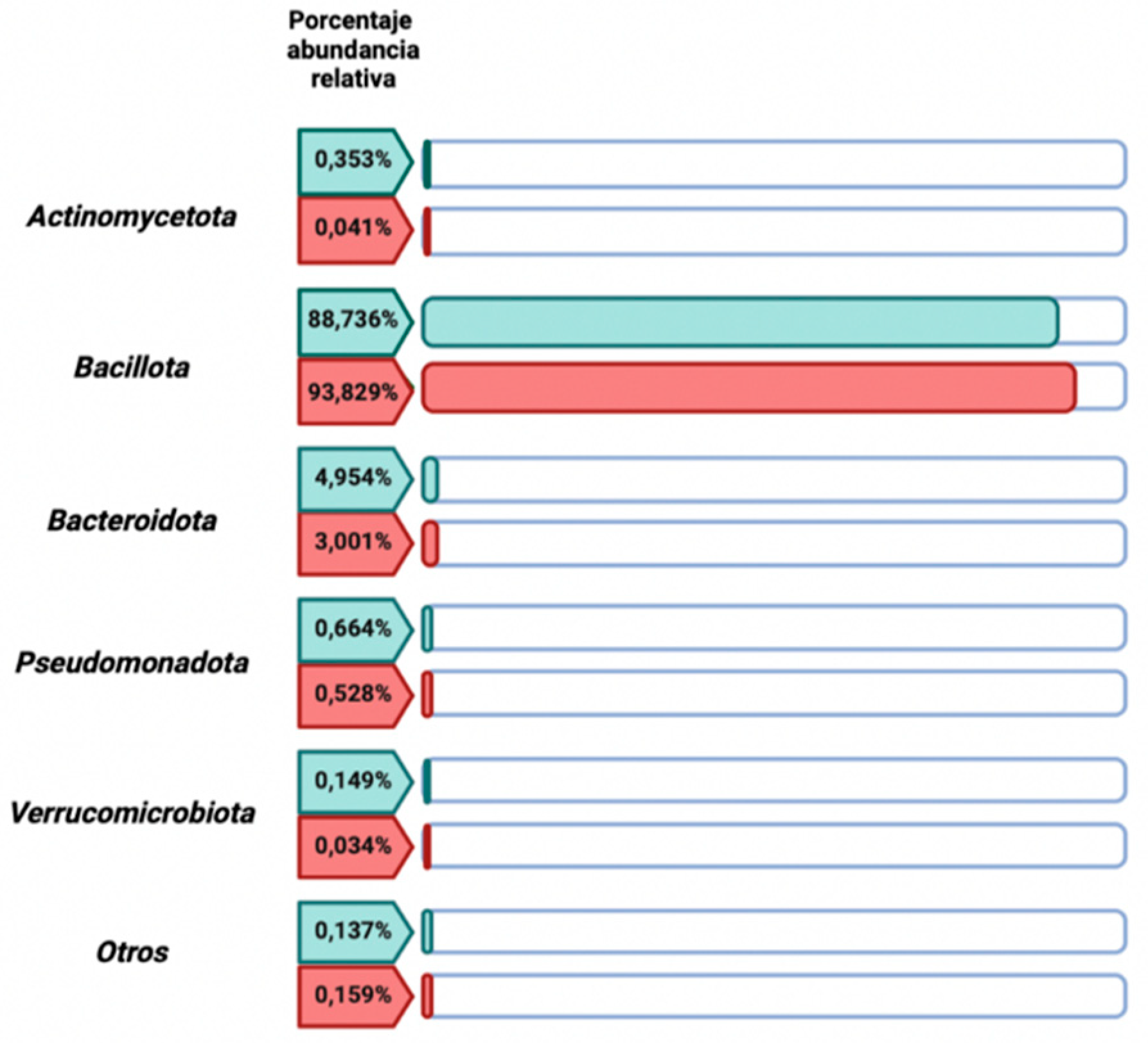

32]. In our results, high-quality sequencing and significant relative abundance of the Gram-positive phylum

Bacillota were observed in both patient groups, indicating the suitability of the process used for bacterial DNA extraction from fecal samples [

33].

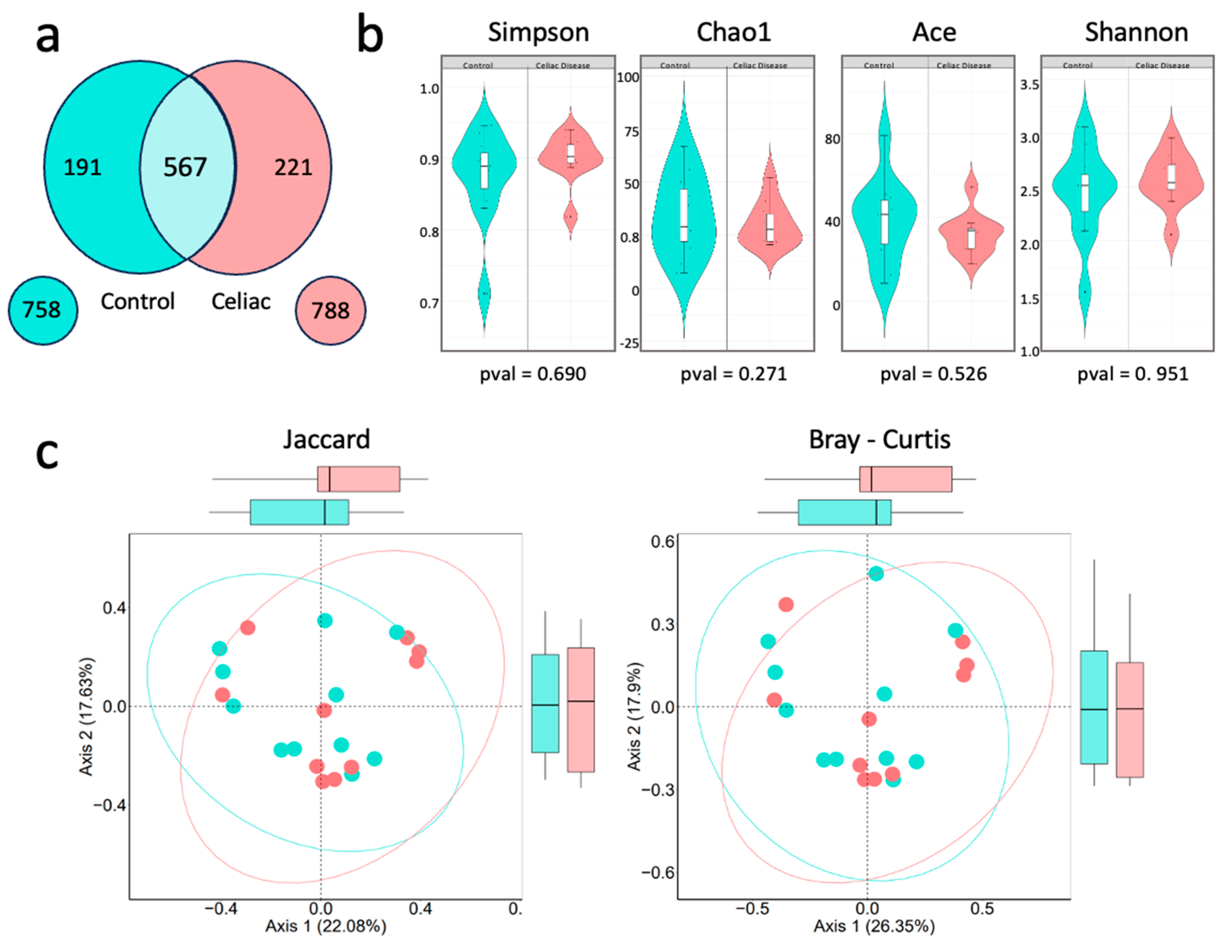

A key finding was the result obtained for both alpha and beta diversity indices. Women with CD on a GFD did not show significant differences compared to the control group in either the composition or the bacterial richness at the genus level. This supports recent studies [

7,

34] that have demonstrated that a GFD can restore microbial balance in the intestines of celiac patients, whose intestinal bacterial dysbiosis is well-documented, thereby improving the gastrointestinal clinical manifestations of the disease. Similarly, other studies suggest that a GFD can restore alpha diversity, while beta diversity differences compared to individuals on a normal diet may persist. This would indicate that celiac patients on a GFD may have a similar amount or richness of bacterial species in their intestines as control individuals, while the exact species present may differ between the two study groups [

34]. Our study did not observe these described differences, which is a positive indicator of the importance of a GFD in modulating the gut microbiota and its potential to improve the health of people with CD.

Biodiversity indices revealed a higher relative proportion of bacteria from the

Bacteroides genus compared to

Prevotella in women with CD. This increase in

Bacteroides is documented in inflammatory gastrointestinal pathologies such as CD, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis [

35]. A higher relative abundance of

Bacteroides was also observed in the metagenomic study in the women with celiac disease compared to the control group. This genus is described as pro-inflammatory, and an abundance of it may exacerbate gastrointestinal inflammatory conditions [

36]. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are components of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria like

Bacteroides. While high doses of LPS are known to induce a strong inflammatory response, recent research [

37,

38] has shown that exposure to small amounts of LPS may not trigger such acute inflammation as high doses, but sustained activation of TLR4 and NF-κB may maintain chronic production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6.

In the case of the metagenomic results obtained for

Streptococcus, another pro-inflammatory genus, a significantly higher abundance was observed in the women with celiac disease compared to the control group. The study by Maciel-Fiuza et al. [

39] highlights that

Streptococcus, in combination with

Veillonella, a genus also increased in the women with celiac disease (Table 3), can exacerbate the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-8, IL-6, and IL-10, contributing to an inflammatory state in the intestines. It is important to note that although general taxonomic diversity may be similar between women with CD and control women, alterations in specific bacterial genera may influence the inflammation and intestinal permeability characteristic of CD. These alterations may not manifest in daily symptoms if patients adhere to a GFD but highlight the importance of monitoring and maintaining a healthy balance in the gut microbiota to prevent long-term complications. Studies such as Spatola [

40] have pointed out that not all celiac patients respond completely to a GFD, with a minority of patients (approximately 10-19%) suffering from non-responsive celiac disease (NRCD), where the intestinal mucosa does not fully recover even after a year on a GFD, with persistent inflammation.

Therefore, the metagenomic results obtained in this study suggest that a GFD could restore bacterial balance in celiac patients, increasing the relative abundance of beneficial SCFA-producing bacteria, such as

Paraprevotella,

Roseburia,

Lactobacillus, or

Faecalibacterium, thus supporting other studies [

10,

41]. This could counteract the possible discussed fiber deficiency in a GFD in celiac patients, as evidenced by a similar substrate degradation capacity in celiac patients compared to the control group.

The increase in the relative abundance of the cultivable Escherichia genus and the significant rise in MICs for the tested antibiotic in anaerobiosis (IMI_EDTA) observed in the control group compared to the celiac group suggests that a non-restrictive diet increases the relative abundance of a bacterial genus known for its ability to acquire and spread antibiotic resistance genes, including carbapenemases, enzymes that degrade carbapenems. Dietary restriction may limit exposure to certain dietary and environmental factors that favor the selection and proliferation of these resistant bacteria.

It is relevant to mention that the functional redundancy of the intestinal microbiota, a concept explaining that different bacterial species can perform similar metabolic functions, ensuring functional stability despite changes in bacterial composition [

42], could explain why, despite significant differences in the relative abundance of specific bacterial genera, the overall functionality of the microbiota in women with CD is not compromised.

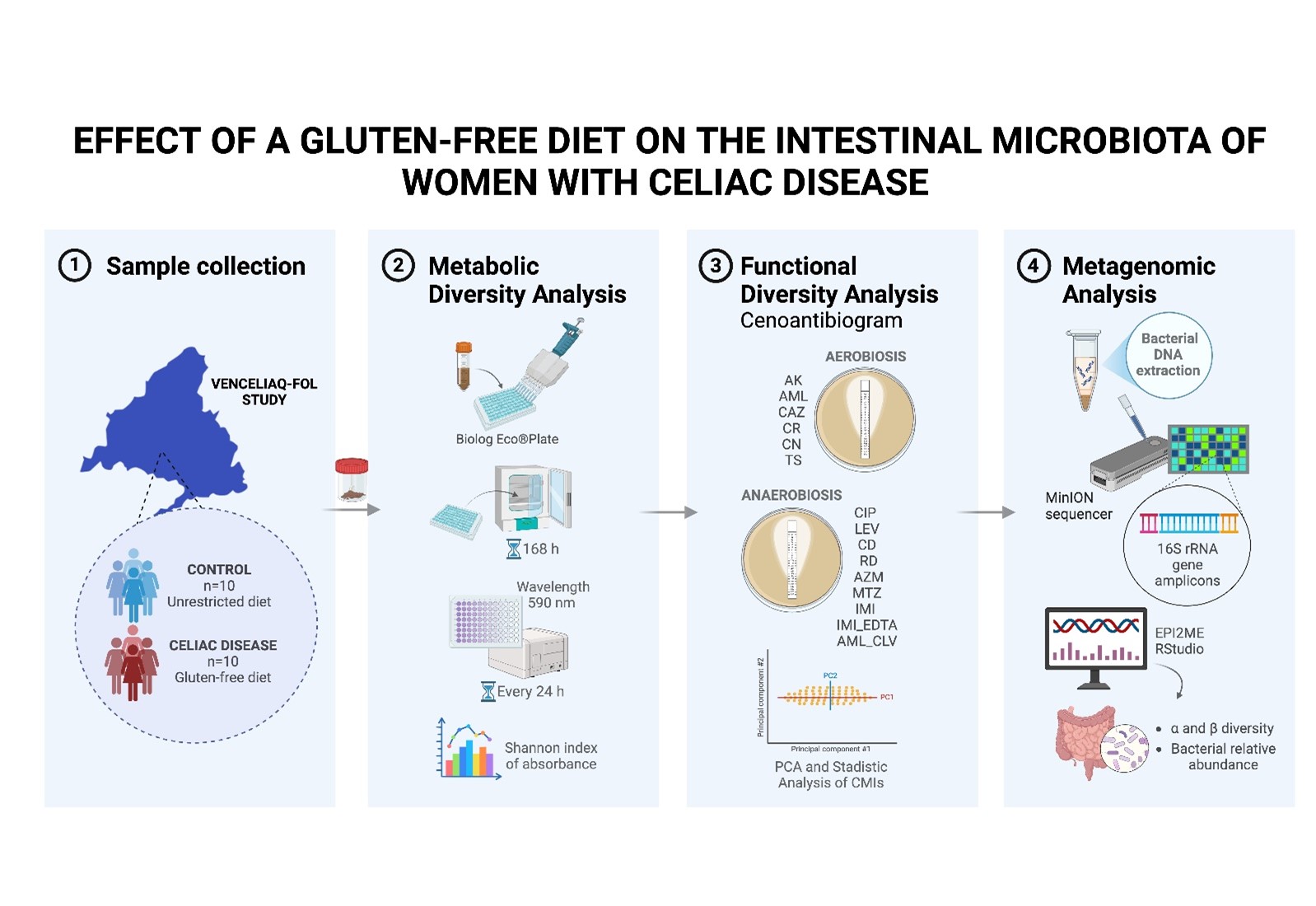

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Collection and Inclusion Criteria

In 2022, a double-blind comparative study was conducted to analyze the gut microbiota of 10 women with diagnosed celiac disease (CD) who were following a gluten-free diet for more than one year, compared to 10 control women following a normal diet. All participants were aged between 19 and 59 years.

The samples were collected by the “Food and Nutrition in Health Promotion Research Group (CEU-NutriFOOD), ref. C08/0720” research group from the CEU San Pablo University (Madrid, Spain) as part of the cross-sectional study on women, VENCELIAQ-FOL. Women with CD were identified through the Spanish Celiac Disease and Gluten Sensitivity Association in Madrid (ACSG), by distributing an informational brochure via email, social media, and the association’s publications. For the recruitment of controls, the research team collaborated with volunteers who expressed interest in participating by learning about the study through CEU-NutriFOOD staff at CEU San Pablo University (Alcorcón, Madrid, Spain) and social media. In both cases, volunteers who did not meet the inclusion criteria (

Table S4) were excluded, as well as women who were pregnant or breastfeeding. Additionally, for the control group, volunteers who tested positive for anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies (AAtTG) were excluded, as they might have undiagnosed CD. A stool sample about the size of a walnut was collected in a sterile container, ensuring it was free from urine or water contamination. The container was sealed tightly and labeled appropriately. The sample was then frozen at -80°C.

4.2. Study of Microbial Community Functionality

A 1:9 dilution of each fecal sample was prepared in saline solution (0.45% NaCl) from 2g of pure sample, and the optical density was adjusted to 0.5 McFarland (>108 CFU/mL of viable microorganisms) using a Densimat® (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Étoile, France). The Biolog Eco® plates were loaded with 135 μL per well. The plates were incubated for 168 hours at 37°C, with absorbance measurements taken every 24 hours at 590 nm using the Asys UVM340 plate reader (Biochrom Ltd, Cambridge, UK) and the Micro WinTM V3.5 software (Mikrotek Laborsysteme GmbH, Overath, Germany).

4.3. Cenoantibiogram

From the same bacterial suspension obtained under the conditions described in the previous section, flooding inoculation was performed on Mueller-Hinton agar (Condalab®, Madrid, Spain), and the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was evaluated in triplicate using antibiotic strips (ε-test). Under aerobic conditions, the following antibiotics were tested: Amikacin (AK), Amoxicillin (AML), Ceftazidime (CAZ), Cefpirome (CR), Gentamicin (CN), and Sulfamethoxazole/Trimethoprim (TS) (BioMérieux®, Marcy l'Etoile, France). The same procedure was performed under anaerobic conditions for the following antibiotics: Ciprofloxacin (CIP), Levofloxacin (LEV), Clindamycin (CD), Rifampicin (RD), Azithromycin (AZM), Metronidazole (MTZ), Imipenem (IMI), Imipenem+EDTA (IMI_EDTA), and Augmentin (AML_CLV) (BioMérieux®, Marcy l'Etoile, France). The plates were incubated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For MIC quantification, the most restrictive halo was used as the reference.

4.4. Statistical Analysis

A principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted, starting with a 2D projection of the factor loadings. The distribution of individuals in the PCA corresponds to the distribution of the factor loadings. To contrast these data, a Student’s t-test was performed to assess significant differences in MIC values between the two study groups. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (Version 30.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

To assess significant differences in MIC values between the celiac and control groups, a Student’s t-test was performed. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (Version 27.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

The raw results obtained from the absorbance measurements of the Biolog Eco® were corrected by subtracting the blank (corrected absorbance value). The r of AWCD (Average Well Color Development) was plotted against incubation time to obtain the growth curves of the microbial community in the wells of the plate. The point of incubation where microbial growth began to enter the stationary phase was selected for subsequent multivariate analyses. Additionally, using the corrected absorbance values at the selected incubation point as AWCD, the metabolic diversity of each sample was calculated using the following formula:; qi= n/N, where n is the corrected absorbance (AWCD) of each well, and N is the total absorbance of all wells.

4.5. Metagenomic Analysis

4.5.1. Bacterial DNA Extraction

Microbial DNA was extracted using the REAL Microbiome Fecal DNA kit (Durviz, Valencia, Spain), and the protocol was optimized to improve the extraction quality. DNA purity and concentration were determined using the NanoDrop One Microvolume UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

4.5.2. Amplification and Library Preparation

DNA amplification was performed using the 16S Barcoding Kit (SQK-RAB204, Oxford Nanopore Technology, Oxford, UK) following Matsuo et al. [

43]. The primers used for amplifying the full 16S gene region were the universal primers 27F (5'-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3') and 1492R (5'-TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3'), with a unique sample barcode sequence attached. PCR was carried out in a thermal cycler with the following conditions: initial denaturation (1 min, 95°C), 25 cycles of denaturation (20 s, 95°C), annealing (30 s, 55°C), and elongation (7 min, 65°C).

The PCR product was purified using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and the library was prepared according to the 16S Barcoding Kit instructions.

4.5.3. Sequencing

200 ng of a pooled library was loaded onto an R9.4.1 flow cell, and sequencing was carried out on the MinION Mk1C device (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) for 24 hours using the MinKNOW analysis software with default settings. Demultiplexing, or obtaining signals by sample, was performed using the same software. The FAST5 sequencing data (voltage change signals) were automatically processed with the Guppy software embedded in the MinKNOW interface with default settings to obtain reads in FASTQ format. Additionally, the quality of the obtained reads was assessed, with a minimum Quality Score of 8.

4.5.4. Processing and Analysis of Metagenomic Data

All the reads that passed quality control were isolated and used as input for the Fastq16S v2022.01.07 workflow from EPI2ME (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK). This protocol uses the NCBI database to return an identification based on sequences analyzed with BLAST. Subsequently, normalization was performed using Total Sum Scaling (TSS) on the CSV reports exported by EPI2ME, utilizing the R programming language and the RStudio interface Version 2023.09.1+494 (RStudio Team, 2023).

The TSS normalization was calculated using the formula: , is the normalized relative abundance of the genus in the sampl,, is the number of reads of the genus in the sample , y is the sum of reads in the sample .

The alpha diversity indices at the taxonomic genus level, including the Shannon indices.(

), Simpson (

), Chao 1 (

) andACE (

) were calculated in RStudio using the “MicrobiomeStat” analysis package to evaluate richness and diversity within the samples (intrasample). Additionally, beta diversity at the taxonomic genus level was calculated using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity (

) and Jaccard index(

), also calculated with “MicrobiomeStat,” to compare diversity between different samples and study groups (intersample). To identify differences in taxon abundance between groups, the statistical method LinDA (Linear Discriminant Analysis) from the “MicrobiomeStat” package, as described by Zhou et al. [

44], was used.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, (AAE), (UMN), (RMM) (RSP) and (JGP); methodology, (RBM), (RSP), (MMM) (DIR) ; software, (GRD), (AHJ); validation, (RMM), (JGP) and (RSP); formal analysis, (AHJ), (GRD) and (MMM); investigation, (MMM), (DIR), and (RSP); resources, (UMN), (AAE), (RMM) and (JGP); data curation, (GRD), (AHJ), and (RSP); writing—original draft preparation (GDR), (MMM); writing—review and editing, (MMM), (RSP); visualization, (DGR), (AHJ); supervision, (DIR); project administration, (UMN), (AAE), (RMM), (RSP) and (JGP); funding acquisition, (RMM), (AAE) and (JGP). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 2.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of the samples under aerobic conditions using different antibiotics. A) 2D loading plot showing the influence of each antibiotic on the first two principal components, where each variable represents the antibiotics used under aerobic conditions: Amikacin (AK), Amoxicillin (AML), Ceftazidime (CAZ), Cefpirome (CR), Gentamicin (CN), and Sulfamethoxazole/Trimethoprim (TS). B) PCA plot representing the distribution and variation trends of the Control group (Red) and the Celiac group (Yellow) samples under aerobic conditions, in the 2D plane defined by the first two principal components, which explain the majority of the model (53.92% variance), in the context of the bacterial community.

Figure 2.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of the samples under aerobic conditions using different antibiotics. A) 2D loading plot showing the influence of each antibiotic on the first two principal components, where each variable represents the antibiotics used under aerobic conditions: Amikacin (AK), Amoxicillin (AML), Ceftazidime (CAZ), Cefpirome (CR), Gentamicin (CN), and Sulfamethoxazole/Trimethoprim (TS). B) PCA plot representing the distribution and variation trends of the Control group (Red) and the Celiac group (Yellow) samples under aerobic conditions, in the 2D plane defined by the first two principal components, which explain the majority of the model (53.92% variance), in the context of the bacterial community.

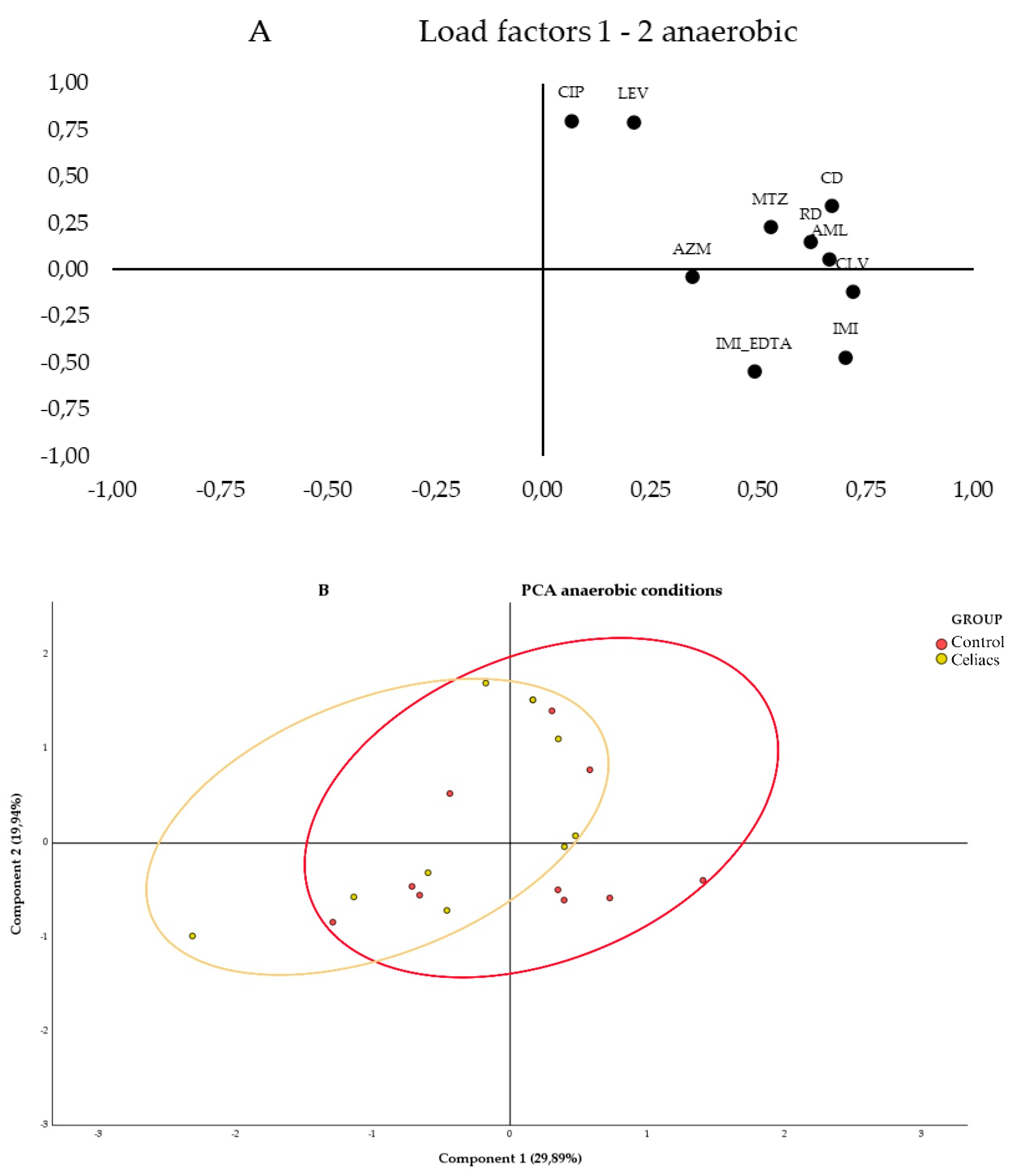

Figure 3.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of the samples under anaerobic conditions using different antibiotics. A) 2D loadings plot showing the influence of each antibiotic on the first two principal components, where each variable represents the antibiotics used under anaerobic conditions: Ciprofloxacin (CIP), Levofloxacin (LEV), Clindamycin (CD), Rifampicin (RD), Azithromycin (AZM), Metronidazole (MTZ), Imipenem (IMI), Imipenem+EDTA (IMI_EDTA), and Augmentin (AML_CLV). B) PCA plot representing the distribution and variation trends of the Control (Red) and Celiac (Celiac) group samples in the space defined by the first two principal components, which explain the majority of the model (49,83% of the variance), within the context of the bacterial community.

Figure 3.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of the samples under anaerobic conditions using different antibiotics. A) 2D loadings plot showing the influence of each antibiotic on the first two principal components, where each variable represents the antibiotics used under anaerobic conditions: Ciprofloxacin (CIP), Levofloxacin (LEV), Clindamycin (CD), Rifampicin (RD), Azithromycin (AZM), Metronidazole (MTZ), Imipenem (IMI), Imipenem+EDTA (IMI_EDTA), and Augmentin (AML_CLV). B) PCA plot representing the distribution and variation trends of the Control (Red) and Celiac (Celiac) group samples in the space defined by the first two principal components, which explain the majority of the model (49,83% of the variance), within the context of the bacterial community.

Figure 4.

Bacterial diversity. a) Venn diagram at the genus level. The light blue center shows the bacterial genera shared between both study groups. b) Bacterial alpha diversity at the genus level, performed with the Simpson, ACE, Chao1, and Shannon tests. c) Bacterial beta diversity at the genus level. On the left, the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index and on the right, the Jaccard index.

Figure 4.

Bacterial diversity. a) Venn diagram at the genus level. The light blue center shows the bacterial genera shared between both study groups. b) Bacterial alpha diversity at the genus level, performed with the Simpson, ACE, Chao1, and Shannon tests. c) Bacterial beta diversity at the genus level. On the left, the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index and on the right, the Jaccard index.

Figure 5.

Relative abundance percentage of the 5 most representative phyla of the human gut microbiota in the control group versus the women with celiac disease study group. Image created with Biorender.

Figure 5.

Relative abundance percentage of the 5 most representative phyla of the human gut microbiota in the control group versus the women with celiac disease study group. Image created with Biorender.

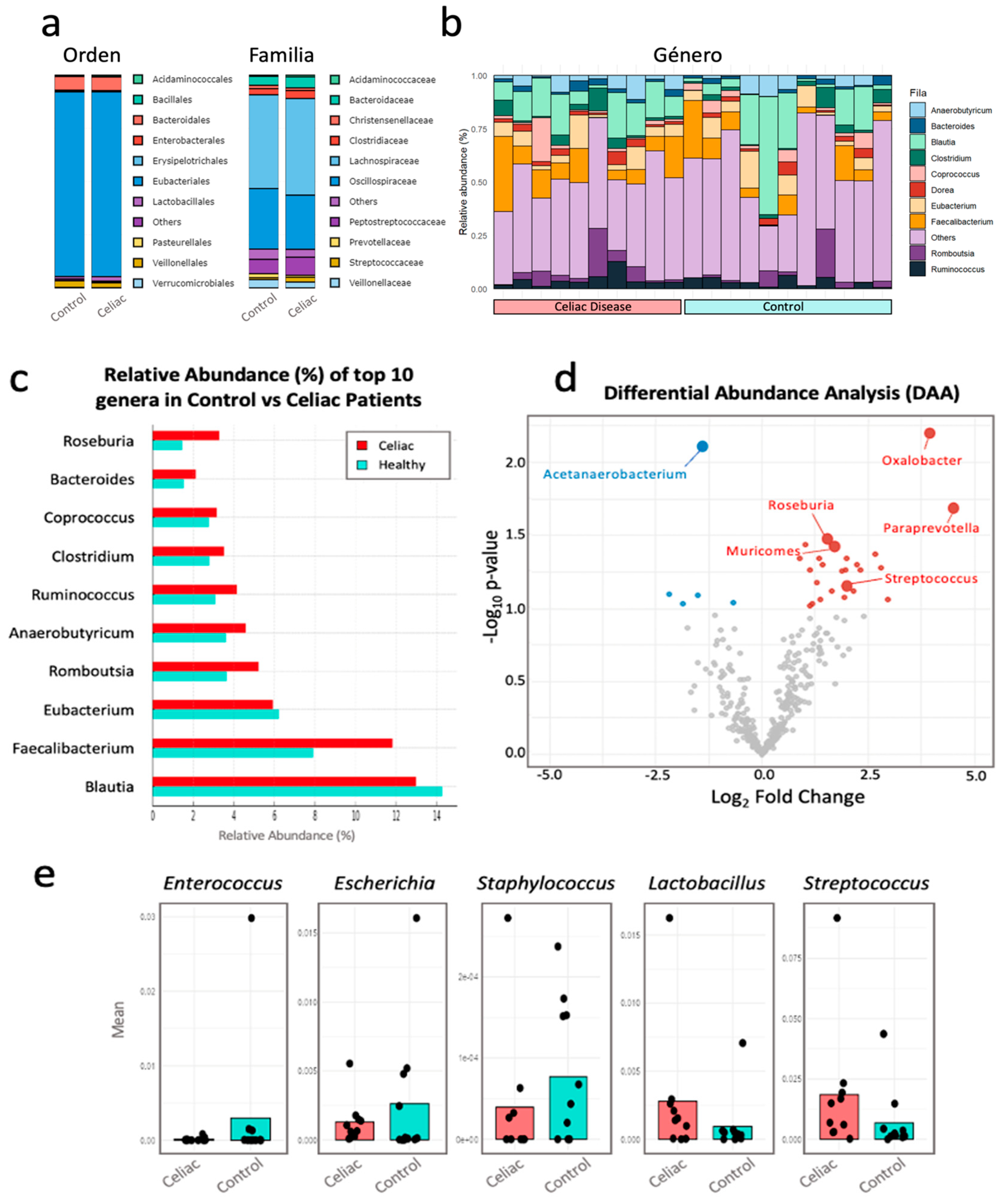

Figure 6.

Comparative analysis of the microbiota composition at different taxonomic levels. a) Comparative bar chart showing the top 10 families and orders with the highest relative abundance, considering those with a relative abundance greater than 0,03 in at least 7 samples. b) Stacked bar chart representing the relative abundance of the top 10 genera within each sample from the Celiac and Control groups. c) Bar chart showing the top 10 genera with the highest relative abundance, considering those with a relative abundance greater than 0,/5903 in at least 7 samples. d) Volcano plot displaying the differential analysis of the relative abundance of bacterial genera using the LinDA method for the Control group (in blue) and the Celiac group (in red), with a cutoff p-value of 0,06. The X-axis represents the log2 Fold Change, indicating the magnitude of change in relative abundance. Positive values on this axis indicate greater abundance in the Celiac group, while negative values indicate greater abundance in the Control group. The Y-axis represents -log10(p-value), where higher values indicate greater statistical significance. e) Boxplot representing cultivable genera: Lactobacillus, Enterococcus, Escherichia, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus.

Figure 6.

Comparative analysis of the microbiota composition at different taxonomic levels. a) Comparative bar chart showing the top 10 families and orders with the highest relative abundance, considering those with a relative abundance greater than 0,03 in at least 7 samples. b) Stacked bar chart representing the relative abundance of the top 10 genera within each sample from the Celiac and Control groups. c) Bar chart showing the top 10 genera with the highest relative abundance, considering those with a relative abundance greater than 0,/5903 in at least 7 samples. d) Volcano plot displaying the differential analysis of the relative abundance of bacterial genera using the LinDA method for the Control group (in blue) and the Celiac group (in red), with a cutoff p-value of 0,06. The X-axis represents the log2 Fold Change, indicating the magnitude of change in relative abundance. Positive values on this axis indicate greater abundance in the Celiac group, while negative values indicate greater abundance in the Control group. The Y-axis represents -log10(p-value), where higher values indicate greater statistical significance. e) Boxplot representing cultivable genera: Lactobacillus, Enterococcus, Escherichia, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus.

Table 1.

Biodiversity Index Values Calculated from the Logarithmic Difference of the Relative Abundance of Each Bacterial Taxon.

Table 1.

Biodiversity Index Values Calculated from the Logarithmic Difference of the Relative Abundance of Each Bacterial Taxon.

| |

Group of study |

| Index |

Control |

Celiacs |

| log Bacillota - log Bacteroidetes

|

1,253 |

1,494 |

| log Bacteroides - log Prevotella

|

-0,094 |

0,617 |