Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

26 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Dietary patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet (MD) and the Western diet (WD), influence gut microbiota composition and functionality, which play important roles in energy metabolism and nutrient absorption. The gut microbiota of 19 Spanish adolescents following these diets was studied to investigate their association with microbial diversity and community structure. Functional diversity was evaluated using Biolog EcoPlates, taxonomic composition was assessed with 16S rRNA sequencing via MinION, and phenotypic responses to antibiotics were analyzed using the technic of cenoantibiogram under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Adolescents with high adherence to the MD exhibited greater functional diversity. Under aerobic conditions, no significant differences in MIC values were observed, but under anaerobic conditions, individuals with low adherence to the MD showed lower MICs for most antibiotics tested. The MD group also showed higher abundance of beneficial bacterial genera such as Paraclostridium, Anaerobutyricum, Romboutsia, and Butyricicoccus. In contrast, the WD group had a microbiota composition similar to that of the low-MD group, characterized by decreased abundance of beneficial genera and an altered microbial profile. These results suggest that the MD promotes a healthier and more balanced gut environment, potentially improving metabolic functions in adolescents. The outcomes of this study highlight opportunities for future research to deepen understanding of the long-term health implications of these dietary patterns, as well as the mechanisms regulating the composition and functionality of gut microbial communities.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

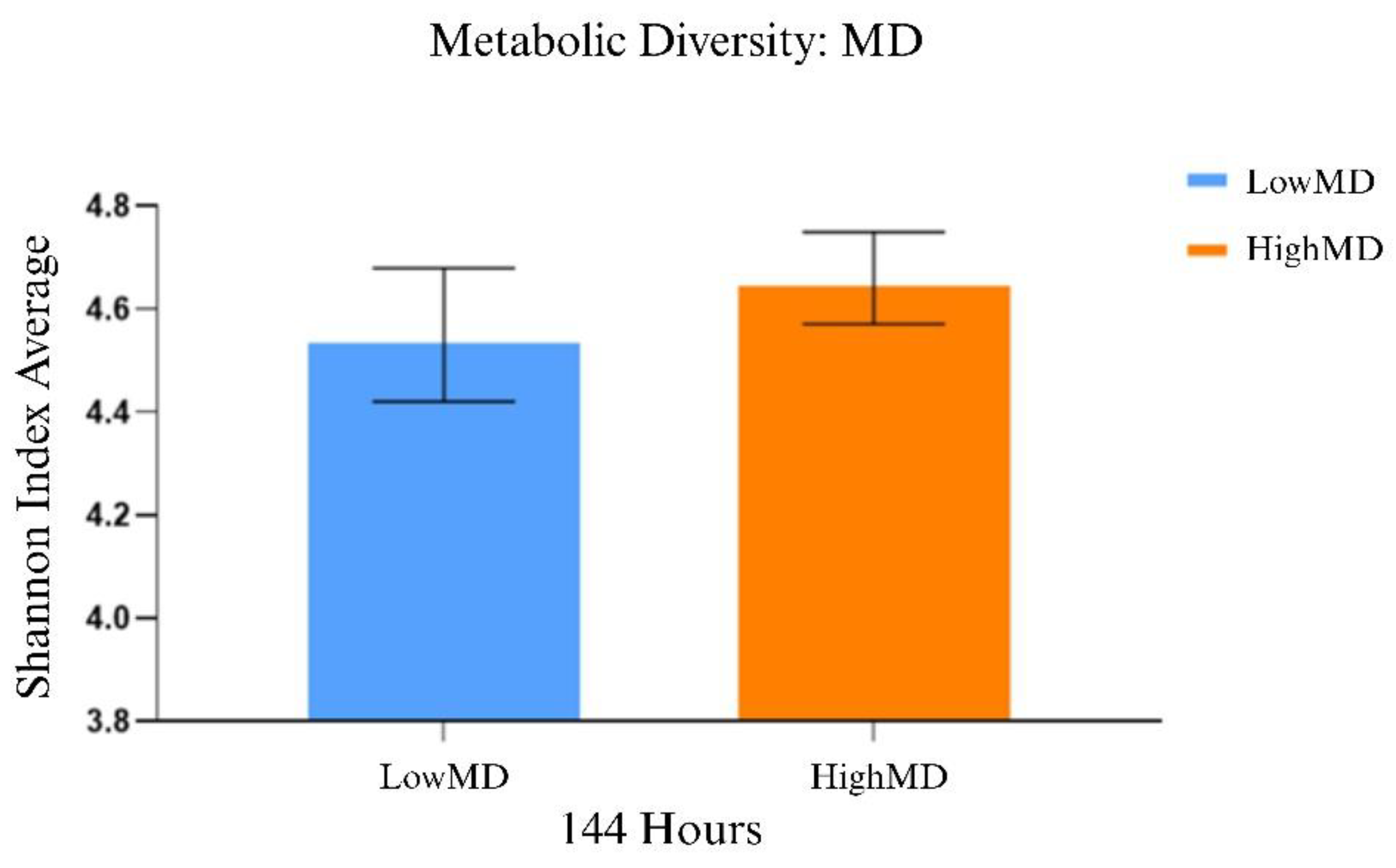

2.1. Comparative Functional Analysis of Gut Microbiota

2.2. Comparative Analysis of Antibiotic Response in Gut Microbiota

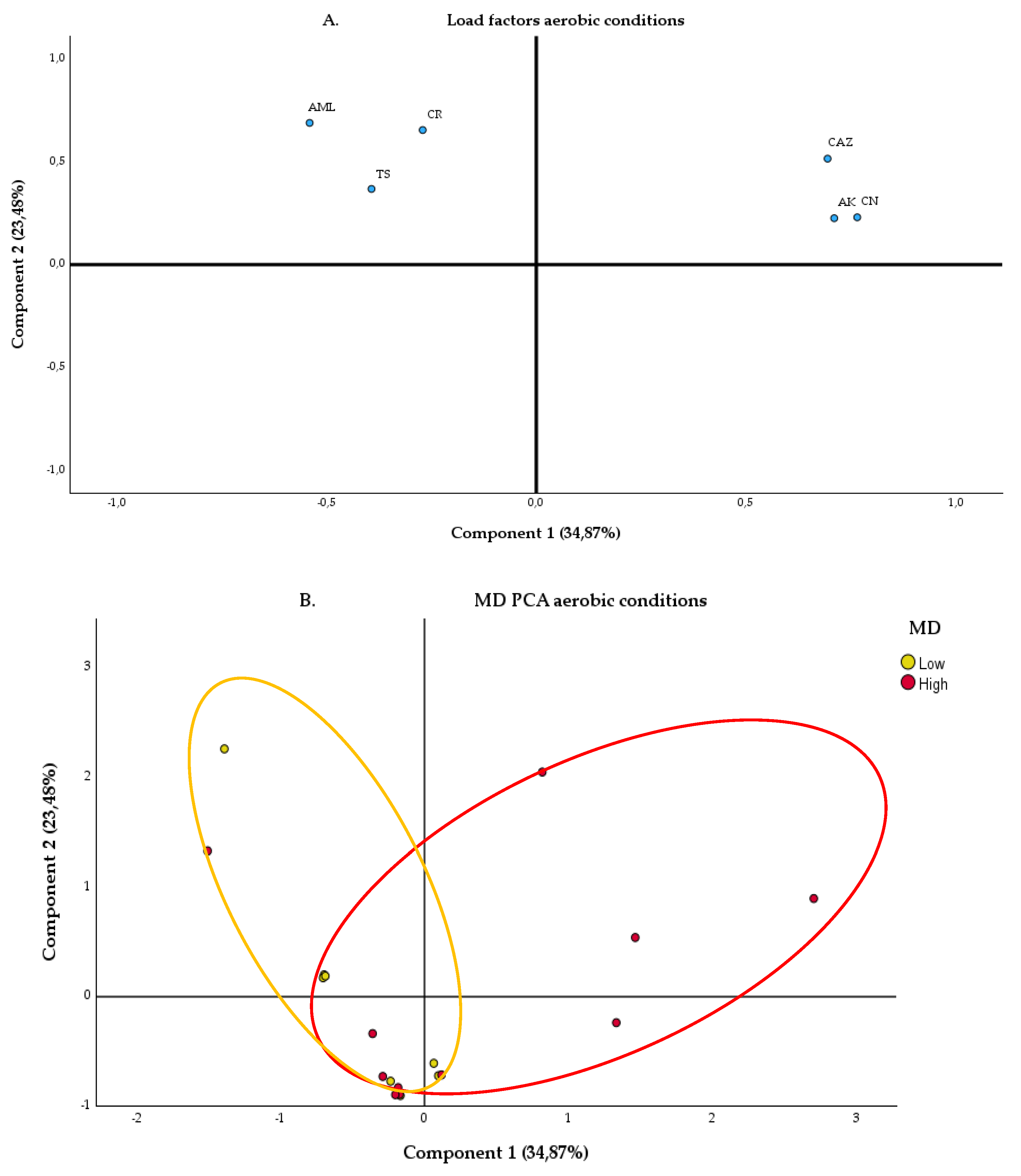

2.2.1. Aerobic Condition

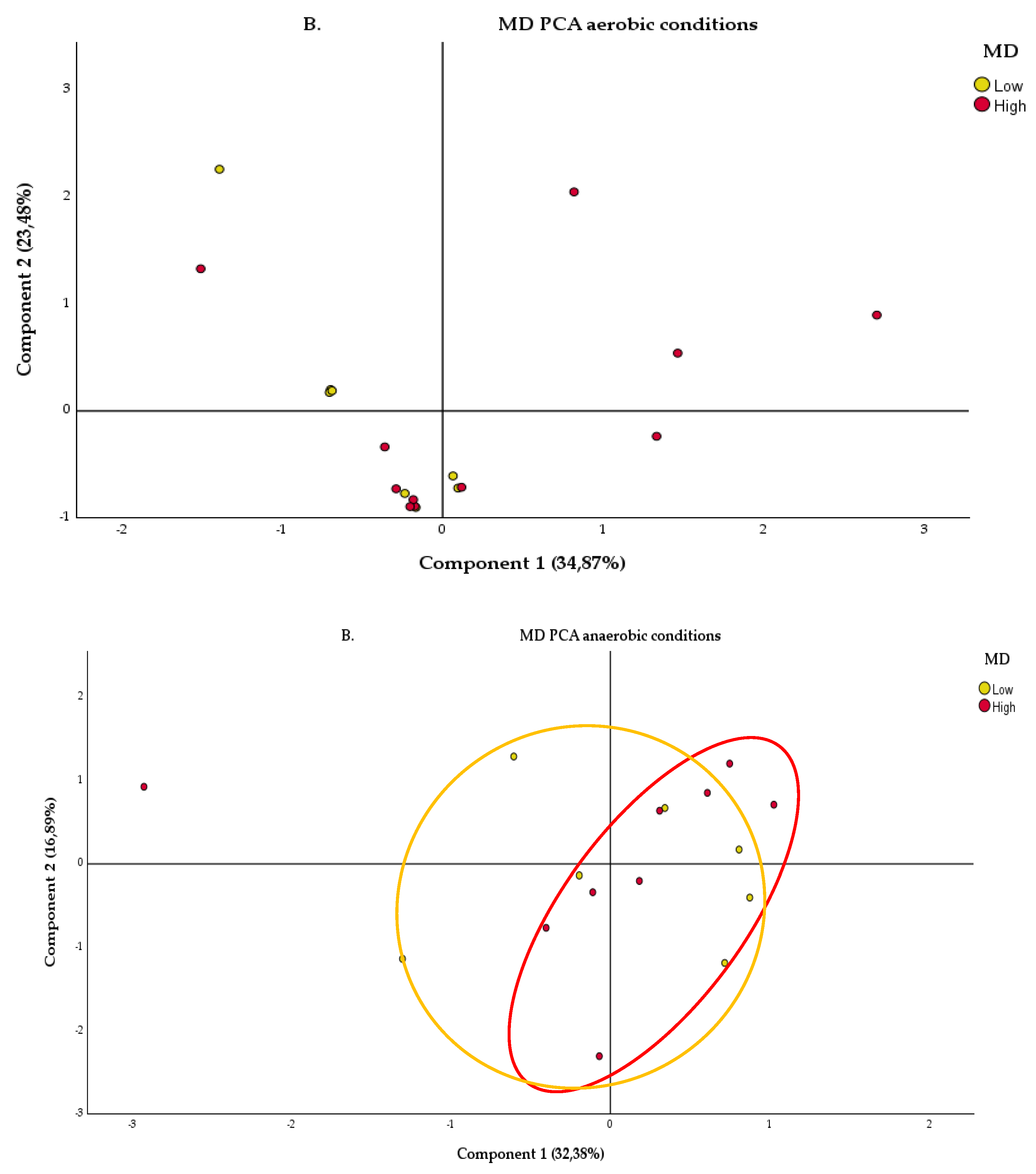

2.2.2. Anaerobic Condition

2.3. Metagenomic Analysis

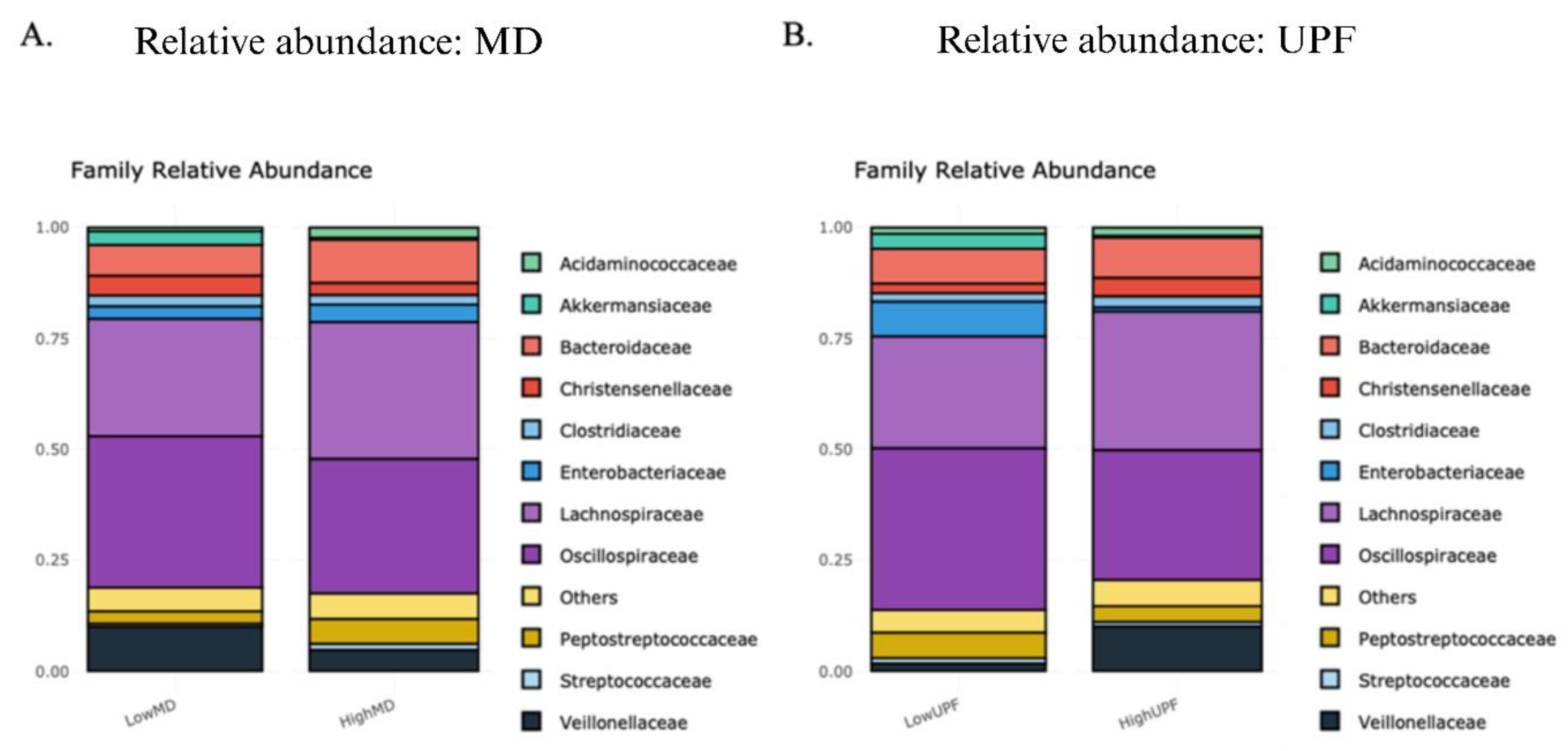

2.3.1. Relative Abundances

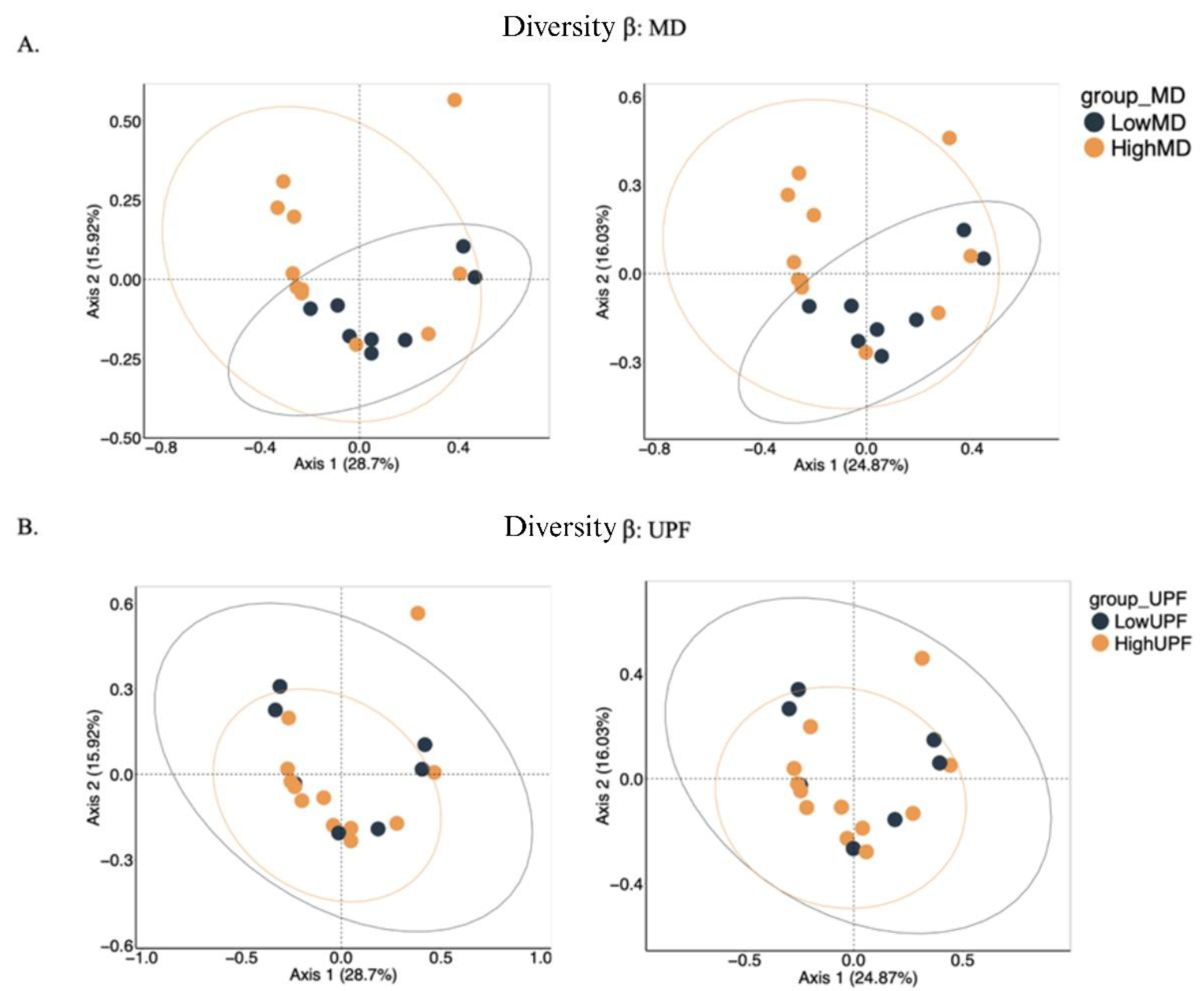

2.3.2 α and β Diversity

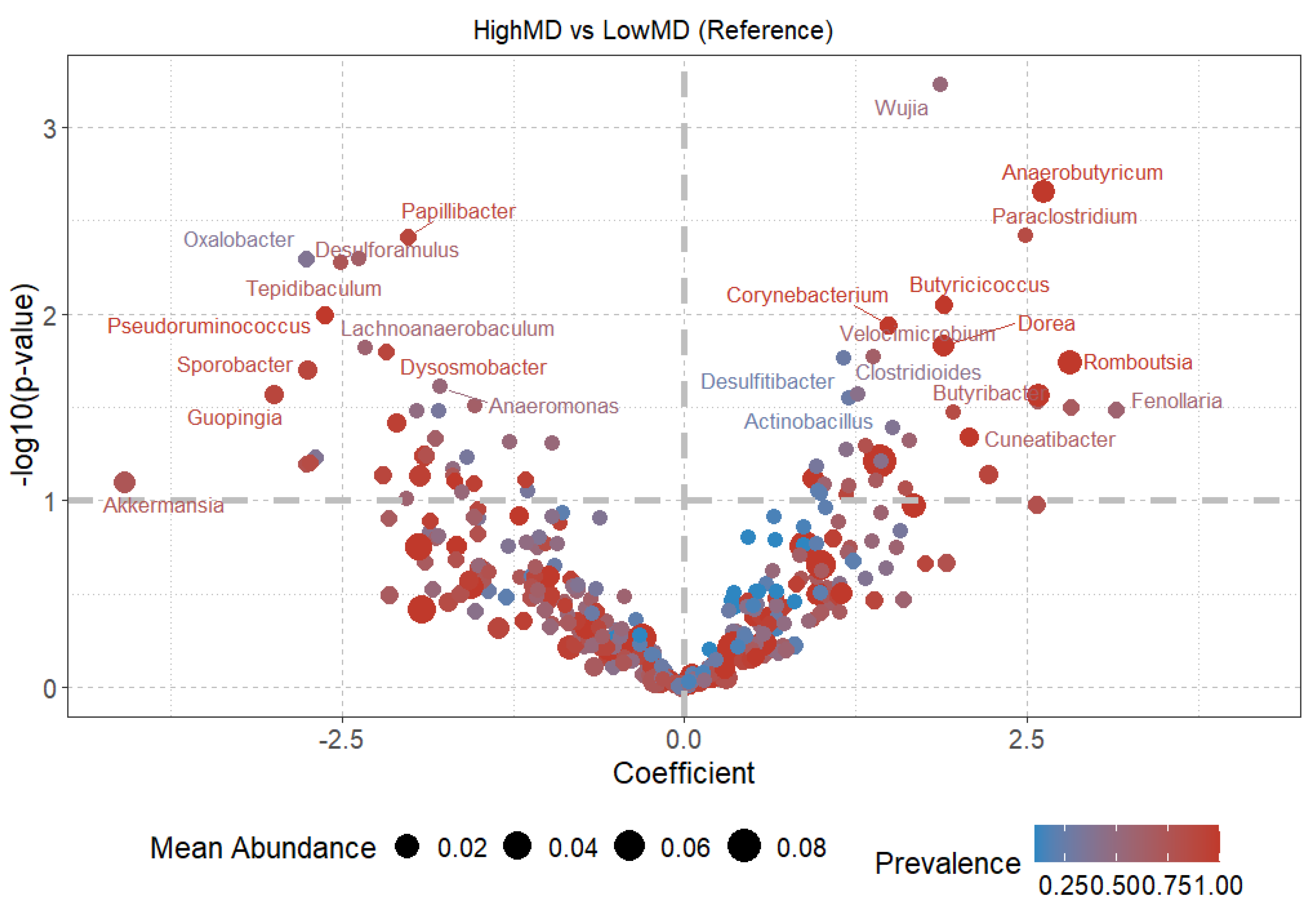

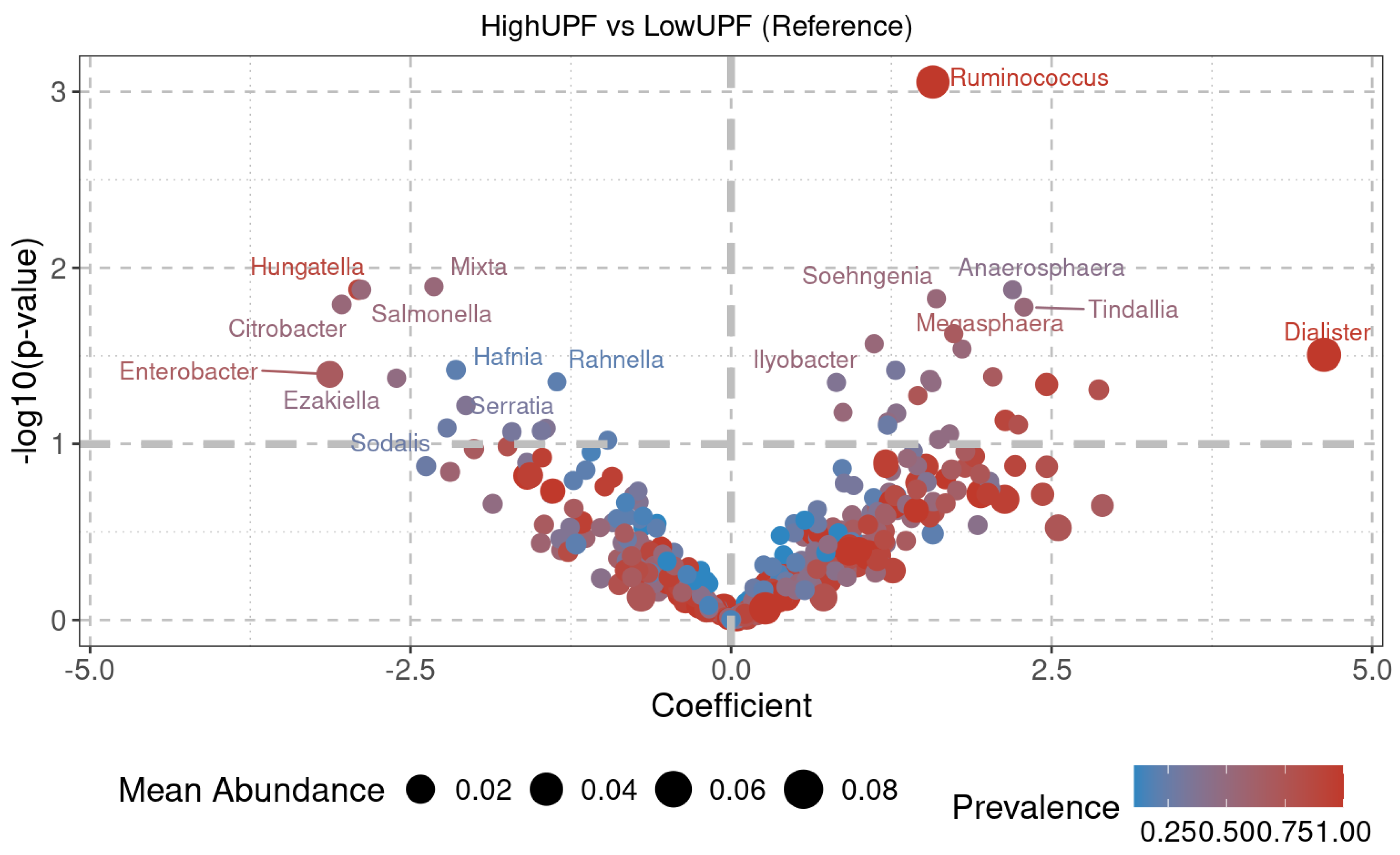

2.3.3. Diversity at the Genus Level

3. Discussion

Study Limitations:

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Sample Collection

4.2. Diet Quality Assessment

4.3. Comparative Functional Analysis of the Intestinal Microbiota

4.4. Comparative Analysis of Antibiotic Response in the Intestinal Microbiota

4.5. Metagenomic Analysis

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heintz-Buschart, A.; Wilmes, P. Human Gut Microbiome: Function Matters. Trends Microbiol 2018, 26, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, J.L.; Karl, J.P.; Oliverio, A.M.; Fu, X.; Soares, J.W.; Wolfe, B.E.; Hernandez, C.J.; Mason, J.B.; Booth, S.L. Dietary Vitamin K Is Remodeled by Gut Microbiota and Influences Community Composition. Gut Microbes 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamichhane, S.; Sen, P.; Dickens, A.M.; Orešič, M.; Bertram, H.C. Gut Metabolome Meets Microbiome: A Methodological Perspective to Understand the Relationship between Host and Microbe. Methods 2018, 149, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derovs, A.; Laivacuma, S.; Krumina, A. Targeting Microbiota: What Do We Know about It at Present? Medicina (B Aires) 2019, 55, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, M.; Blacher, E.; Elinav, E. Microbiome, Metabolites and Host Immunity. Curr Opin Microbiol 2017, 35, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budden, K.F.; Shukla, S.D.; Rehman, S.F.; Bowerman, K.L.; Keely, S.; Hugenholtz, P.; Armstrong-James, D.P.H.; Adcock, I.M.; Chotirmall, S.H.; Chung, K.F. Functional Effects of the Microbiota in Chronic Respiratory Disease. Lancet Respir Med 2019, 7, 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolph, D.; Margraf, J. Differential Effects of Trait-like Emotion Regulation Use and Situational Emotion Regulation Ability across the Affective and Anxiety Disorders Spectrum: A Transdiagnostic Examination. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 26642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardocci, M.; Leclerc, B.-S.; Louzada, M.-L.; Monteiro, C.A.; Batal, M.; Moubarac, J.-C. Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Obesity in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health 2019, 110, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, B.R.S.; Rico-Campà, A.; Romanos-Nanclares, A.; Ciriza, E.; Barbosa, K.B.F.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Martín-Calvo, N. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet Is Inversely Associated with the Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods among Spanish Children: The SENDO Project. Public Health Nutr 2021, 24, 3294–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, M.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Costanzo, S.; Pounis, G.; Persichillo, M.; Cerletti, C.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L. Mediterranean-Type Diet Is Associated with Higher Psychological Resilience in a General Adult Population: Findings from the Moli-Sani Study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2018, 72, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Gea, A.; Ruiz-Canela, M. The Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular Health. Circ Res 2019, 124, 779–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, M.; Li, X.; Wegener Parfrey, L.; Roth, B.; Ippoliti, A.; Wei, B.; Borneman, J.; McGovern, D.P.B.; Frank, D.N.; Li, E. A Modular Organization of the Human Intestinal Mucosal Microbiota and Its Association with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. PLoS One 2013, 8, e80702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization International Organizations Unite on Critical Recommendations to Combat Drug-Resistant Infections and Prevent Staggering Number of Deaths Each Year.

- Zhang, L.; Wang, P.; Huang, J.; Xing, Y.; Wong, F.S.; Suo, J.; Wen, L. Gut Microbiota and Therapy for Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, T.M.; Kabisch, S.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H.; Weickert, M.O. The Effects of the Mediterranean Diet on Health and Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamamah, S.; Iatcu, O.C.; Covasa, M. Nutrition at the Intersection between Gut Microbiota Eubiosis and Effective Management of Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrients 2024, 16, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vossen, E.W.J.; Davids, M.; Bresser, L.R.F.; Galenkamp, H.; van den Born, B.-J.H.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Levin, E.; Nieuwdorp, M.; de Goffau, M.C. Gut Microbiome Transitions across Generations in Different Ethnicities in an Urban Setting—the HELIUS Study. Microbiome 2023, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Plaza, S.; Hernández-Terán, A.; Navarro-Díaz, M.; Escalante, A.E.; Morales-Espinosa, R.; Cerritos, R. Human Gut Microbiome Across Different Lifestyles: From Hunter-Gatherers to Urban Populations. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.L.; Vlamakis, H.; Lee, J.W.J.; Besse, L.A.; Xanthakis, V.; Vasan, R.S.; Shaw, S.Y.; Xavier, R.J. Population Study of the Gut Microbiome: Associations with Diet, Lifestyle, and Cardiometabolic Disease. Genome Med 2021, 13, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, R.; Shively, C.A.; Register, T.C.; Craft, S.; Yadav, H. Gut Microbiome-Mediterranean Diet Interactions in Improving Host Health. F1000Res 2019, 8, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhrstad, M.C.W.; Tunsjø, H.; Charnock, C.; Telle-Hansen, V.H. Dietary Fiber, Gut Microbiota, and Metabolic Regulation—Current Status in Human Randomized Trials. Nutrients 2020, 12, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Global Impacts of Western Diet and Its Effects on Metabolism and Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merra, G.; Noce, A.; Marrone, G.; Cintoni, M.; Tarsitano, M.G.; Capacci, A.; De Lorenzo, A. Influence of Mediterranean Diet on Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2020, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.D.; Compher, C.; Chen, E.Z.; Smith, S.A.; Shah, R.D.; Bittinger, K.; Chehoud, C.; Albenberg, L.G.; Nessel, L.; Gilroy, E. Comparative Metabolomics in Vegans and Omnivores Reveal Constraints on Diet-Dependent Gut Microbiota Metabolite Production. Gut 2016, 65, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosés, C.; Cuevas-Sierra, A.; Quintana, S.; Riezu-Boj, J.I.; Martínez, J.A.; Milagro, F.I.; Barceló, A. Gut Microbiota Bacterial Species Associated with Mediterranean Diet-Related Food Groups in a Northern Spanish Population. Nutrients 2021, 13, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Chen, D.; Wang, F.; Fan, X.; Fan, C.; Tang, T.; Li, P.; Yang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Qi, K. An Insight into the Exploration of Proliferation of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in High-Fat Diet Induced Obesity Mice. Genomics 2021, 113, 2503–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Q.; Black, A.; Kales, S.N.; Vattem, D.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Sotos-Prieto, M. Metabolomics and Microbiomes as Potential Tools to Evaluate the Effects of the Mediterranean Diet. Nutrients 2019, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Jing, Z.; Wei, W.; Chun, Z.; Quan, Q.; Qing, Z.; Jiamin, X.; Shuwen, H. Inhibitory Effect of Sodium Butyrate on Colorectal Cancer Cells and Construction of the Related Molecular Network. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, C.; Jiang, Q.; Yin, Y. Butyrate in Energy Metabolism: There Is Still More to Learn. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 2021, 32, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangifesta, M.; Mancabelli, L.; Milani, C.; Gaiani, F.; de’Angelis, N.; de’Angelis, G.L.; van Sinderen, D.; Ventura, M.; Turroni, F. Mucosal Microbiota of Intestinal Polyps Reveals Putative Biomarkers of Colorectal Cancer. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 13974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.J.; Vangay, P.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Hillmann, B.M.; Ward, T.L.; Shields-Cutler, R.R.; Kim, A.D.; Shmagel, A.K.; Syed, A.N.; Walter, J. Daily Sampling Reveals Personalized Diet-Microbiome Associations in Humans. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 789–802.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, D.; Cárdenas, P.A.; Prado-Vivar, B.; Graham, J.P.; Trueba, G. A Longitudinal Study of Dominant E. Coli Lineages and Antimicrobial Resistance in the Gut of Children Living in an Upper Middle-Income Country. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2022, 29, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinson, J.N. V; Pinkham, N. V; Peters, G.W.; Cho, H.; Heng, J.; Rauch, M.; Broadaway, S.C.; Walk, S.T. Rethinking Gut Microbiome Residency and the Enterobacteriaceae in Healthy Human Adults. ISME J 2019, 13, 2306–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Checcucci, A.; Luise, D.; Modesto, M.; Correa, F.; Bosi, P.; Mattarelli, P.; Trevisi, P. Assessment of Biolog EcoplateTM Method for Functional Metabolic Diversity of Aerotolerant Pig Fecal Microbiota. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2021, 105, 6033–6045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benítez-Páez, A.; Portune, K.J.; Sanz, Y. Species-Level Resolution of 16S RRNA Gene Amplicons Sequenced through the MinIONTM Portable Nanopore Sequencer. Gigascience 2016, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Majem, L.; Ribas, L.; Ngo, J.; Ortega, R.M.; García, A.; Pérez-Rodrigo, C.; Aranceta, J. Food, Youth and the Mediterranean Diet in Spain. Development of KIDMED, Mediterranean Diet Quality Index in Children and Adolescents. Public Health Nutr 2004, 7, 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Perez, C.; Daimiel, L.; Climent-Mainar, C.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Corella, D.; Schröder, H.; Martinez, J.A.; Alonso-Gómez, Á.M.; Wärnberg, J. Integrative Development of a Short Screening Questionnaire of Highly Processed Food Consumption (SQ-HPF). International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2022, 19, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, J.L. Analytical Approaches to the Characterization of Samples of Microbial Communities Using Patterns of Potential C Source Utilization. Soil Biol Biochem 1996, 28, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofo, A.; Ricciuti, P. A Standardized Method for Estimating the Functional Diversity of Soil Bacterial Community by Biolog® EcoPlatesTM Assay—The Case Study of a Sustainable Olive Orchard. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marina Robas Mora; Pedro Antonio Jiménez Gómez; Carolina Valbuena; Agustín Probanza Effect of the Type of Vitis Vinifera Cultivation in the Cenophenoresistome and Metabolic Profiling (CLPP) of Edaphic Bacterial Communities. J Agric Sci Technol A 2017, 7. [CrossRef]

- Heintz-Buschart, A.; Wilmes, P. Human Gut Microbiome: Function Matters. Trends Microbiol 2018, 26, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.L.; Karl, J.P.; Oliverio, A.M.; Fu, X.; Soares, J.W.; Wolfe, B.E.; Hernandez, C.J.; Mason, J.B.; Booth, S.L. Dietary Vitamin K Is Remodeled by Gut Microbiota and Influences Community Composition. Gut Microbes 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamichhane, S.; Sen, P.; Dickens, A.M.; Orešič, M.; Bertram, H.C. Gut Metabolome Meets Microbiome: A Methodological Perspective to Understand the Relationship between Host and Microbe. Methods 2018, 149, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derovs, A.; Laivacuma, S.; Krumina, A. Targeting Microbiota: What Do We Know about It at Present? Medicina (B Aires) 2019, 55, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.; Blacher, E.; Elinav, E. Microbiome, Metabolites and Host Immunity. Curr Opin Microbiol 2017, 35, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budden, K.F.; Shukla, S.D.; Rehman, S.F.; Bowerman, K.L.; Keely, S.; Hugenholtz, P.; Armstrong-James, D.P.H.; Adcock, I.M.; Chotirmall, S.H.; Chung, K.F. Functional Effects of the Microbiota in Chronic Respiratory Disease. Lancet Respir Med 2019, 7, 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolph, D.; Margraf, J. Differential Effects of Trait-like Emotion Regulation Use and Situational Emotion Regulation Ability across the Affective and Anxiety Disorders Spectrum: A Transdiagnostic Examination. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 26642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardocci, M.; Leclerc, B.-S.; Louzada, M.-L.; Monteiro, C.A.; Batal, M.; Moubarac, J.-C. Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Obesity in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health 2019, 110, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, B.R.S.; Rico-Campà, A.; Romanos-Nanclares, A.; Ciriza, E.; Barbosa, K.B.F.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Martín-Calvo, N. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet Is Inversely Associated with the Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods among Spanish Children: The SENDO Project. Public Health Nutr 2021, 24, 3294–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, M.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Costanzo, S.; Pounis, G.; Persichillo, M.; Cerletti, C.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L. Mediterranean-Type Diet Is Associated with Higher Psychological Resilience in a General Adult Population: Findings from the Moli-Sani Study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2018, 72, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Gea, A.; Ruiz-Canela, M. The Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular Health. Circ Res 2019, 124, 779–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.; Li, X.; Wegener Parfrey, L.; Roth, B.; Ippoliti, A.; Wei, B.; Borneman, J.; McGovern, D.P.B.; Frank, D.N.; Li, E. A Modular Organization of the Human Intestinal Mucosal Microbiota and Its Association with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. PLoS One 2013, 8, e80702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization International Organizations Unite on Critical Recommendations to Combat Drug-Resistant Infections and Prevent Staggering Number of Deaths Each Year.

- Zhang, L.; Wang, P.; Huang, J.; Xing, Y.; Wong, F.S.; Suo, J.; Wen, L. Gut Microbiota and Therapy for Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, T.M.; Kabisch, S.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H.; Weickert, M.O. The Effects of the Mediterranean Diet on Health and Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamamah, S.; Iatcu, O.C.; Covasa, M. Nutrition at the Intersection between Gut Microbiota Eubiosis and Effective Management of Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrients 2024, 16, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vossen, E.W.J.; Davids, M.; Bresser, L.R.F.; Galenkamp, H.; van den Born, B.-J.H.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Levin, E.; Nieuwdorp, M.; de Goffau, M.C. Gut Microbiome Transitions across Generations in Different Ethnicities in an Urban Setting—the HELIUS Study. Microbiome 2023, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Plaza, S.; Hernández-Terán, A.; Navarro-Díaz, M.; Escalante, A.E.; Morales-Espinosa, R.; Cerritos, R. Human Gut Microbiome Across Different Lifestyles: From Hunter-Gatherers to Urban Populations. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.L.; Vlamakis, H.; Lee, J.W.J.; Besse, L.A.; Xanthakis, V.; Vasan, R.S.; Shaw, S.Y.; Xavier, R.J. Population Study of the Gut Microbiome: Associations with Diet, Lifestyle, and Cardiometabolic Disease. Genome Med 2021, 13, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, R.; Shively, C.A.; Register, T.C.; Craft, S.; Yadav, H. Gut Microbiome-Mediterranean Diet Interactions in Improving Host Health. F1000Res 2019, 8, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhrstad, M.C.W.; Tunsjø, H.; Charnock, C.; Telle-Hansen, V.H. Dietary Fiber, Gut Microbiota, and Metabolic Regulation—Current Status in Human Randomized Trials. Nutrients 2020, 12, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Global Impacts of Western Diet and Its Effects on Metabolism and Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merra, G.; Noce, A.; Marrone, G.; Cintoni, M.; Tarsitano, M.G.; Capacci, A.; De Lorenzo, A. Influence of Mediterranean Diet on Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2020, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.D.; Compher, C.; Chen, E.Z.; Smith, S.A.; Shah, R.D.; Bittinger, K.; Chehoud, C.; Albenberg, L.G.; Nessel, L.; Gilroy, E. Comparative Metabolomics in Vegans and Omnivores Reveal Constraints on Diet-Dependent Gut Microbiota Metabolite Production. Gut 2016, 65, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosés, C.; Cuevas-Sierra, A.; Quintana, S.; Riezu-Boj, J.I.; Martínez, J.A.; Milagro, F.I.; Barceló, A. Gut Microbiota Bacterial Species Associated with Mediterranean Diet-Related Food Groups in a Northern Spanish Population. Nutrients 2021, 13, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Chen, D.; Wang, F.; Fan, X.; Fan, C.; Tang, T.; Li, P.; Yang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Qi, K. An Insight into the Exploration of Proliferation of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in High-Fat Diet Induced Obesity Mice. Genomics 2021, 113, 2503–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Q.; Black, A.; Kales, S.N.; Vattem, D.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Sotos-Prieto, M. Metabolomics and Microbiomes as Potential Tools to Evaluate the Effects of the Mediterranean Diet. Nutrients 2019, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Jing, Z.; Wei, W.; Chun, Z.; Quan, Q.; Qing, Z.; Jiamin, X.; Shuwen, H. Inhibitory Effect of Sodium Butyrate on Colorectal Cancer Cells and Construction of the Related Molecular Network. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, C.; Jiang, Q.; Yin, Y. Butyrate in Energy Metabolism: There Is Still More to Learn. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 2021, 32, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangifesta, M.; Mancabelli, L.; Milani, C.; Gaiani, F.; de’Angelis, N.; de’Angelis, G.L.; van Sinderen, D.; Ventura, M.; Turroni, F. Mucosal Microbiota of Intestinal Polyps Reveals Putative Biomarkers of Colorectal Cancer. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 13974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.J.; Vangay, P.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Hillmann, B.M.; Ward, T.L.; Shields-Cutler, R.R.; Kim, A.D.; Shmagel, A.K.; Syed, A.N.; Walter, J. Daily Sampling Reveals Personalized Diet-Microbiome Associations in Humans. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 789–802.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, D.; Cárdenas, P.A.; Prado-Vivar, B.; Graham, J.P.; Trueba, G. A Longitudinal Study of Dominant E. Coli Lineages and Antimicrobial Resistance in the Gut of Children Living in an Upper Middle-Income Country. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2022, 29, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinson, J.N. V; Pinkham, N. V; Peters, G.W.; Cho, H.; Heng, J.; Rauch, M.; Broadaway, S.C.; Walk, S.T. Rethinking Gut Microbiome Residency and the Enterobacteriaceae in Healthy Human Adults. ISME J 2019, 13, 2306–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Checcucci, A.; Luise, D.; Modesto, M.; Correa, F.; Bosi, P.; Mattarelli, P.; Trevisi, P. Assessment of Biolog EcoplateTM Method for Functional Metabolic Diversity of Aerotolerant Pig Fecal Microbiota. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2021, 105, 6033–6045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benítez-Páez, A.; Portune, K.J.; Sanz, Y. Species-Level Resolution of 16S RRNA Gene Amplicons Sequenced through the MinIONTM Portable Nanopore Sequencer. Gigascience 2016, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra-Majem, L.; Ribas, L.; Ngo, J.; Ortega, R.M.; García, A.; Pérez-Rodrigo, C.; Aranceta, J. Food, Youth and the Mediterranean Diet in Spain. Development of KIDMED, Mediterranean Diet Quality Index in Children and Adolescents. Public Health Nutr 2004, 7, 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Perez, C.; Daimiel, L.; Climent-Mainar, C.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Corella, D.; Schröder, H.; Martinez, J.A.; Alonso-Gómez, Á.M.; Wärnberg, J. Integrative Development of a Short Screening Questionnaire of Highly Processed Food Consumption (SQ-HPF). International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2022, 19, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, J.L. Analytical Approaches to the Characterization of Samples of Microbial Communities Using Patterns of Potential C Source Utilization. Soil Biol Biochem 1996, 28, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofo, A.; Ricciuti, P. A Standardized Method for Estimating the Functional Diversity of Soil Bacterial Community by Biolog® EcoPlatesTM Assay—The Case Study of a Sustainable Olive Orchard. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marina Robas Mora; Pedro Antonio Jiménez Gómez; Carolina Valbuena; Agustín Probanza Effect of the Type of Vitis Vinifera Cultivation in the Cenophenoresistome and Metabolic Profiling (CLPP) of Edaphic Bacterial Communities. J Agric Sci Technol A 2017, 7. [CrossRef]

- Heintz-Buschart, A.; Wilmes, P. Human Gut Microbiome: Function Matters. Trends Microbiol 2018, 26, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.L.; Karl, J.P.; Oliverio, A.M.; Fu, X.; Soares, J.W.; Wolfe, B.E.; Hernandez, C.J.; Mason, J.B.; Booth, S.L. Dietary Vitamin K Is Remodeled by Gut Microbiota and Influences Community Composition. Gut Microbes 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, S.; Sen, P.; Dickens, A.M.; Orešič, M.; Bertram, H.C. Gut Metabolome Meets Microbiome: A Methodological Perspective to Understand the Relationship between Host and Microbe. Methods 2018, 149, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derovs, A.; Laivacuma, S.; Krumina, A. Targeting Microbiota: What Do We Know about It at Present? Medicina (B Aires) 2019, 55, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, M.; Blacher, E.; Elinav, E. Microbiome, Metabolites and Host Immunity. Curr Opin Microbiol 2017, 35, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budden, K.F.; Shukla, S.D.; Rehman, S.F.; Bowerman, K.L.; Keely, S.; Hugenholtz, P.; Armstrong-James, D.P.H.; Adcock, I.M.; Chotirmall, S.H.; Chung, K.F. Functional Effects of the Microbiota in Chronic Respiratory Disease. Lancet Respir Med 2019, 7, 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adolph, D.; Margraf, J. Differential Effects of Trait-like Emotion Regulation Use and Situational Emotion Regulation Ability across the Affective and Anxiety Disorders Spectrum: A Transdiagnostic Examination. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 26642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardocci, M.; Leclerc, B.-S.; Louzada, M.-L.; Monteiro, C.A.; Batal, M.; Moubarac, J.-C. Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Obesity in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health 2019, 110, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, B.R.S.; Rico-Campà, A.; Romanos-Nanclares, A.; Ciriza, E.; Barbosa, K.B.F.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Martín-Calvo, N. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet Is Inversely Associated with the Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods among Spanish Children: The SENDO Project. Public Health Nutr 2021, 24, 3294–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, M.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Costanzo, S.; Pounis, G.; Persichillo, M.; Cerletti, C.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L. Mediterranean-Type Diet Is Associated with Higher Psychological Resilience in a General Adult Population: Findings from the Moli-Sani Study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2018, 72, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Gea, A.; Ruiz-Canela, M. The Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular Health. Circ Res 2019, 124, 779–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.; Li, X.; Wegener Parfrey, L.; Roth, B.; Ippoliti, A.; Wei, B.; Borneman, J.; McGovern, D.P.B.; Frank, D.N.; Li, E. A Modular Organization of the Human Intestinal Mucosal Microbiota and Its Association with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. PLoS One 2013, 8, e80702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization International Organizations Unite on Critical Recommendations to Combat Drug-Resistant Infections and Prevent Staggering Number of Deaths Each Year.

- Zhang, L.; Wang, P.; Huang, J.; Xing, Y.; Wong, F.S.; Suo, J.; Wen, L. Gut Microbiota and Therapy for Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, T.M.; Kabisch, S.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H.; Weickert, M.O. The Effects of the Mediterranean Diet on Health and Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamamah, S.; Iatcu, O.C.; Covasa, M. Nutrition at the Intersection between Gut Microbiota Eubiosis and Effective Management of Type 2 Diabetes. Nutrients 2024, 16, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Vossen, E.W.J.; Davids, M.; Bresser, L.R.F.; Galenkamp, H.; van den Born, B.-J.H.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Levin, E.; Nieuwdorp, M.; de Goffau, M.C. Gut Microbiome Transitions across Generations in Different Ethnicities in an Urban Setting—the HELIUS Study. Microbiome 2023, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosas-Plaza, S.; Hernández-Terán, A.; Navarro-Díaz, M.; Escalante, A.E.; Morales-Espinosa, R.; Cerritos, R. Human Gut Microbiome Across Different Lifestyles: From Hunter-Gatherers to Urban Populations. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.L.; Vlamakis, H.; Lee, J.W.J.; Besse, L.A.; Xanthakis, V.; Vasan, R.S.; Shaw, S.Y.; Xavier, R.J. Population Study of the Gut Microbiome: Associations with Diet, Lifestyle, and Cardiometabolic Disease. Genome Med 2021, 13, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, R.; Shively, C.A.; Register, T.C.; Craft, S.; Yadav, H. Gut Microbiome-Mediterranean Diet Interactions in Improving Host Health. F1000Res 2019, 8, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhrstad, M.C.W.; Tunsjø, H.; Charnock, C.; Telle-Hansen, V.H. Dietary Fiber, Gut Microbiota, and Metabolic Regulation—Current Status in Human Randomized Trials. Nutrients 2020, 12, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Global Impacts of Western Diet and Its Effects on Metabolism and Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merra, G.; Noce, A.; Marrone, G.; Cintoni, M.; Tarsitano, M.G.; Capacci, A.; De Lorenzo, A. Influence of Mediterranean Diet on Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2020, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.D.; Compher, C.; Chen, E.Z.; Smith, S.A.; Shah, R.D.; Bittinger, K.; Chehoud, C.; Albenberg, L.G.; Nessel, L.; Gilroy, E. Comparative Metabolomics in Vegans and Omnivores Reveal Constraints on Diet-Dependent Gut Microbiota Metabolite Production. Gut 2016, 65, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosés, C.; Cuevas-Sierra, A.; Quintana, S.; Riezu-Boj, J.I.; Martínez, J.A.; Milagro, F.I.; Barceló, A. Gut Microbiota Bacterial Species Associated with Mediterranean Diet-Related Food Groups in a Northern Spanish Population. Nutrients 2021, 13, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Chen, D.; Wang, F.; Fan, X.; Fan, C.; Tang, T.; Li, P.; Yang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Qi, K. An Insight into the Exploration of Proliferation of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in High-Fat Diet Induced Obesity Mice. Genomics 2021, 113, 2503–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Black, A.; Kales, S.N.; Vattem, D.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Sotos-Prieto, M. Metabolomics and Microbiomes as Potential Tools to Evaluate the Effects of the Mediterranean Diet. Nutrients 2019, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, Y.; Jing, Z.; Wei, W.; Chun, Z.; Quan, Q.; Qing, Z.; Jiamin, X.; Shuwen, H. Inhibitory Effect of Sodium Butyrate on Colorectal Cancer Cells and Construction of the Related Molecular Network. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, C.; Jiang, Q.; Yin, Y. Butyrate in Energy Metabolism: There Is Still More to Learn. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 2021, 32, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangifesta, M.; Mancabelli, L.; Milani, C.; Gaiani, F.; de’Angelis, N.; de’Angelis, G.L.; van Sinderen, D.; Ventura, M.; Turroni, F. Mucosal Microbiota of Intestinal Polyps Reveals Putative Biomarkers of Colorectal Cancer. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 13974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.J.; Vangay, P.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Hillmann, B.M.; Ward, T.L.; Shields-Cutler, R.R.; Kim, A.D.; Shmagel, A.K.; Syed, A.N.; Walter, J. Daily Sampling Reveals Personalized Diet-Microbiome Associations in Humans. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 789–802.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, D.; Cárdenas, P.A.; Prado-Vivar, B.; Graham, J.P.; Trueba, G. A Longitudinal Study of Dominant E. Coli Lineages and Antimicrobial Resistance in the Gut of Children Living in an Upper Middle-Income Country. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2022, 29, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinson, J.N. V; Pinkham, N. V; Peters, G.W.; Cho, H.; Heng, J.; Rauch, M.; Broadaway, S.C.; Walk, S.T. Rethinking Gut Microbiome Residency and the Enterobacteriaceae in Healthy Human Adults. ISME J 2019, 13, 2306–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checcucci, A.; Luise, D.; Modesto, M.; Correa, F.; Bosi, P.; Mattarelli, P.; Trevisi, P. Assessment of Biolog EcoplateTM Method for Functional Metabolic Diversity of Aerotolerant Pig Fecal Microbiota. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2021, 105, 6033–6045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Páez, A.; Portune, K.J.; Sanz, Y. Species-Level Resolution of 16S RRNA Gene Amplicons Sequenced through the MinIONTM Portable Nanopore Sequencer. Gigascience 2016, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra-Majem, L.; Ribas, L.; Ngo, J.; Ortega, R.M.; García, A.; Pérez-Rodrigo, C.; Aranceta, J. Food, Youth and the Mediterranean Diet in Spain. Development of KIDMED, Mediterranean Diet Quality Index in Children and Adolescents. Public Health Nutr 2004, 7, 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Perez, C.; Daimiel, L.; Climent-Mainar, C.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Corella, D.; Schröder, H.; Martinez, J.A.; Alonso-Gómez, Á.M.; Wärnberg, J. Integrative Development of a Short Screening Questionnaire of Highly Processed Food Consumption (SQ-HPF). International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2022, 19, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garland, J.L. Analytical Approaches to the Characterization of Samples of Microbial Communities Using Patterns of Potential C Source Utilization. Soil Biol Biochem 1996, 28, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofo, A.; Ricciuti, P. A Standardized Method for Estimating the Functional Diversity of Soil Bacterial Community by Biolog® EcoPlatesTM Assay—The Case Study of a Sustainable Olive Orchard. Applied Sciences 2019, 9, 4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marina Robas Mora; Pedro Antonio Jiménez Gómez; Carolina Valbuena; Agustín Probanza Effect of the Type of Vitis Vinifera Cultivation in the Cenophenoresistome and Metabolic Profiling (CLPP) of Edaphic Bacterial Communities. J Agric Sci Technol A 2017, 7. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).