Submitted:

29 September 2025

Posted:

30 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

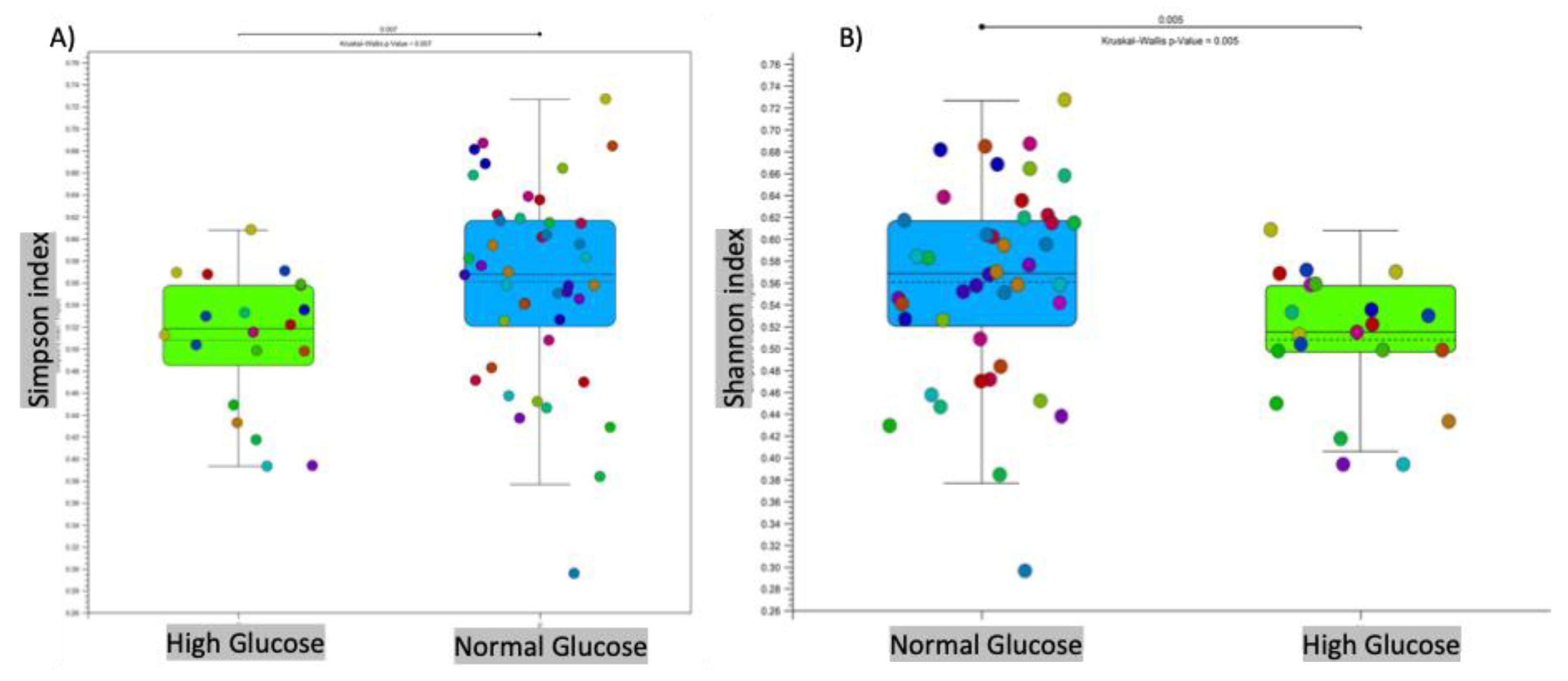

Intestinal dysbiosis has been linked to metabolic disorders, including insulin resistance and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM). T2DM typically follows a prediabetic stage, during which insulin resistance develops. During early stages of T2DM, its development can be corrected, thus potentially preventing or delaying the onset of the disease. This study aimed to compare the gut microbiome of individuals with elevated fasting blood glucose to that of individuals with glucose levels within the normal range. This study involved 65 older adults (ages 76–83 years) enrolled from the randomized controlled trial entitled the “Generation 100 Study”, all of whom consented to provide their gut microbiome samples. We employed a high-throughput sequencing of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene to obtain metagenomic microbial profiles for all participants. These profiles were then correlated with clinical measures. Overall, microbial alpha diversity was significantly reduced in the high glucose group. We have also observed distinct patterns of microbial beta diversity between high and normal glucose groups. At the phylum level, we found that Synergistes, Elusimicobia, Euryarchaeota, Verrucomicrobia, and Proteobacteria were all significantly decreased in participants with high blood glucose. Additionally, P. copri (ASV 909561) was significantly elevated (10-fold increase) in the high glucose groups, suggesting that it may serve as an early T2DM marker. In contrast to prior reports on the Fusobacterium genus, we found that it was significantly increased in the normal glucose group, with a significant 151-fold increase compared to the high glucose group. Our results indicate significant changes in the microbiome that may provide valuable insights for early intervention in pre-diabetic states.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

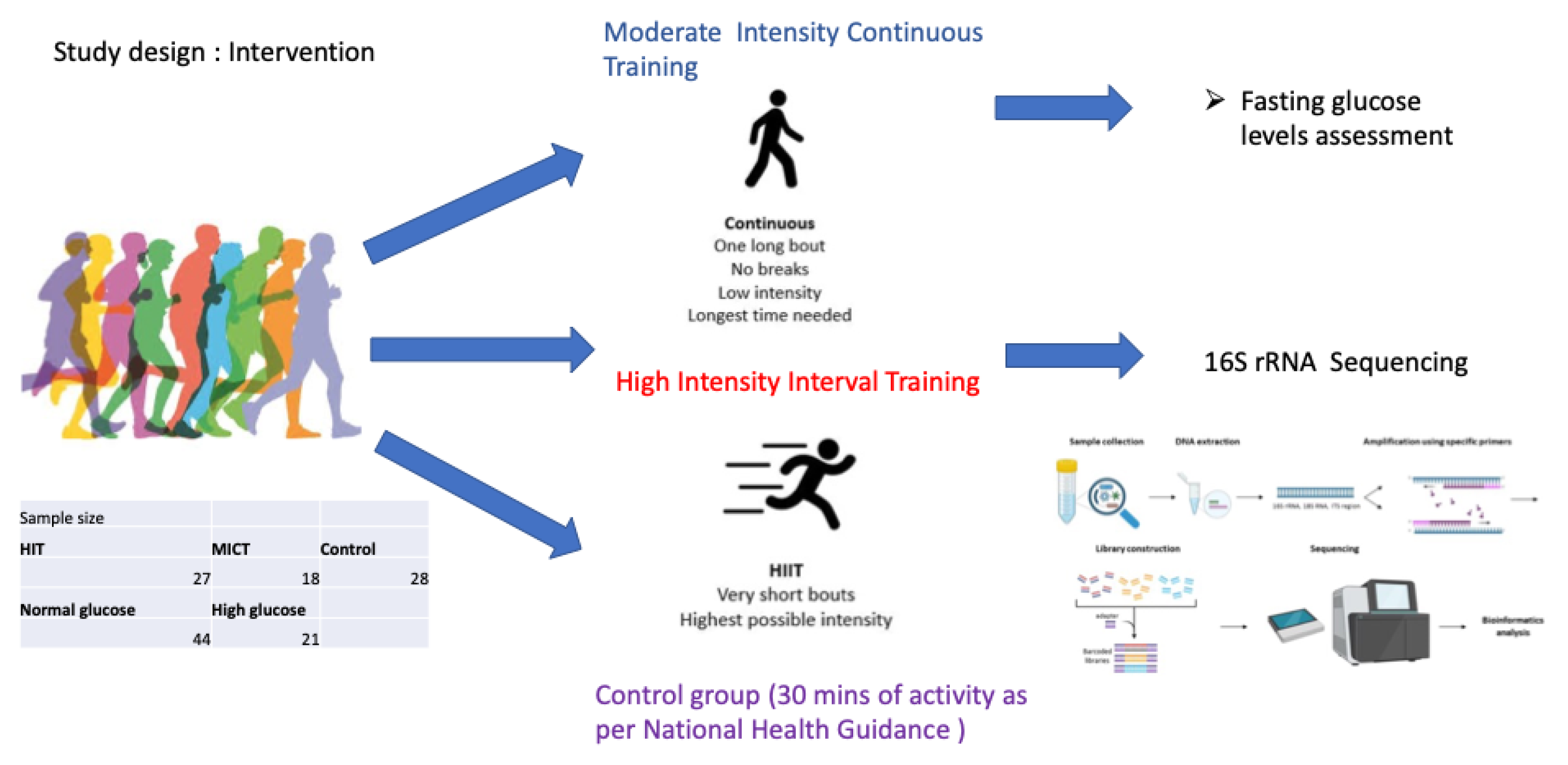

2. Materials and Methods

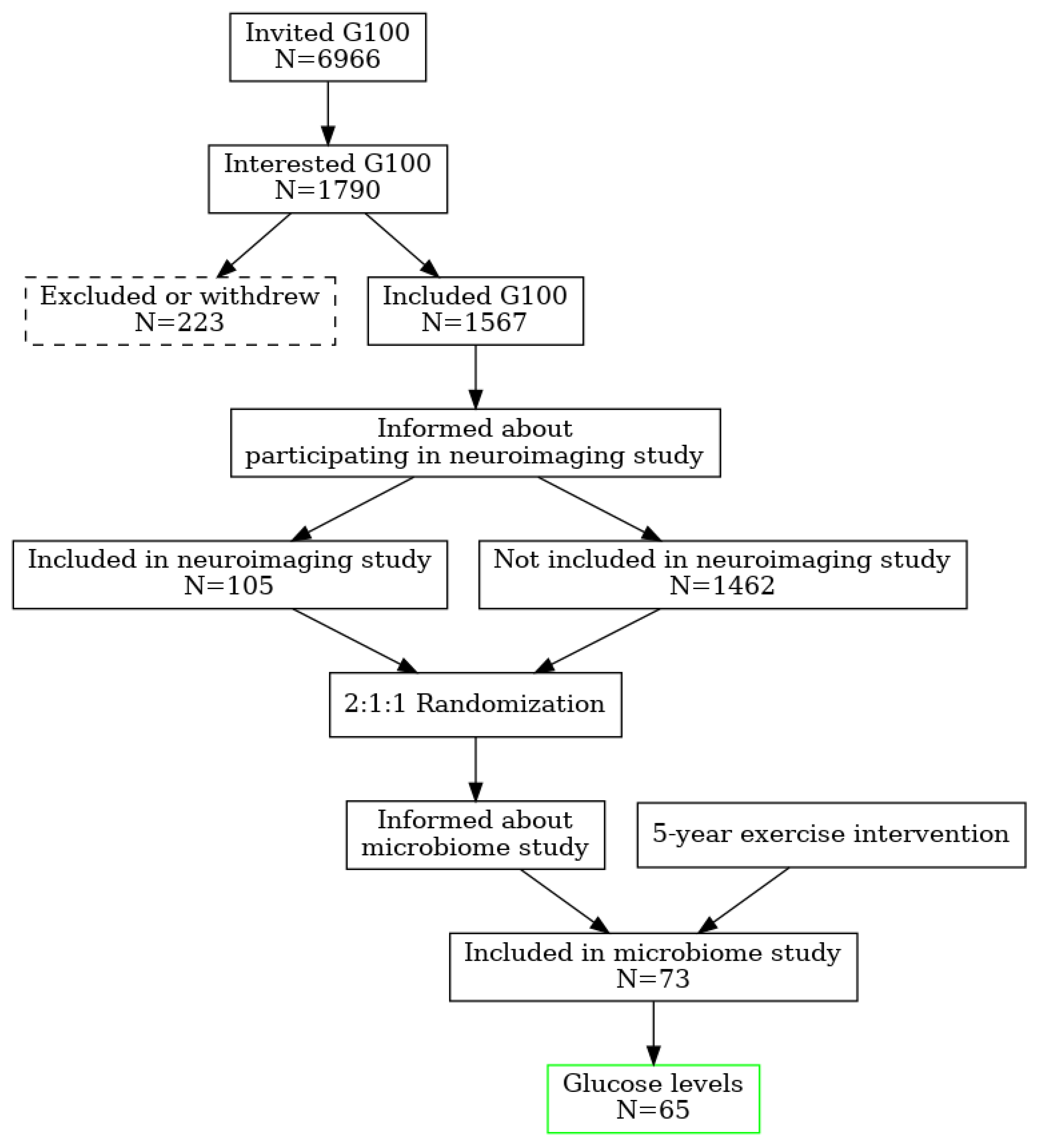

2.1. Population, Randomization, Ethics

2.2. Gut Microbiome Collection and Preparation

2.3. DNA Extraction and 16s Ribosomal RNA Sequencing

2.4. Data Quality Control and Analysis

3. Results

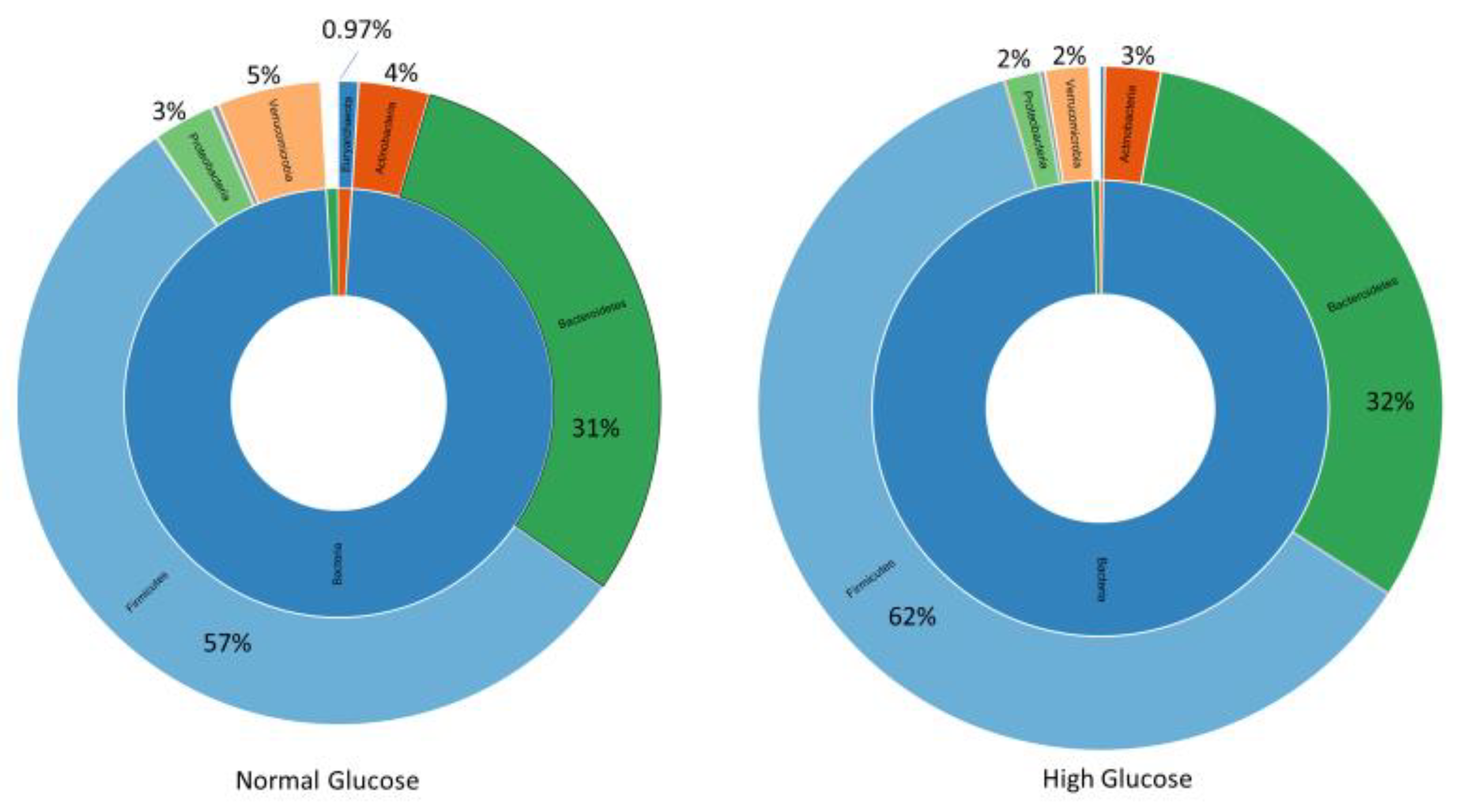

3.1. Microbial Diversity and Composition at the Phylum Level

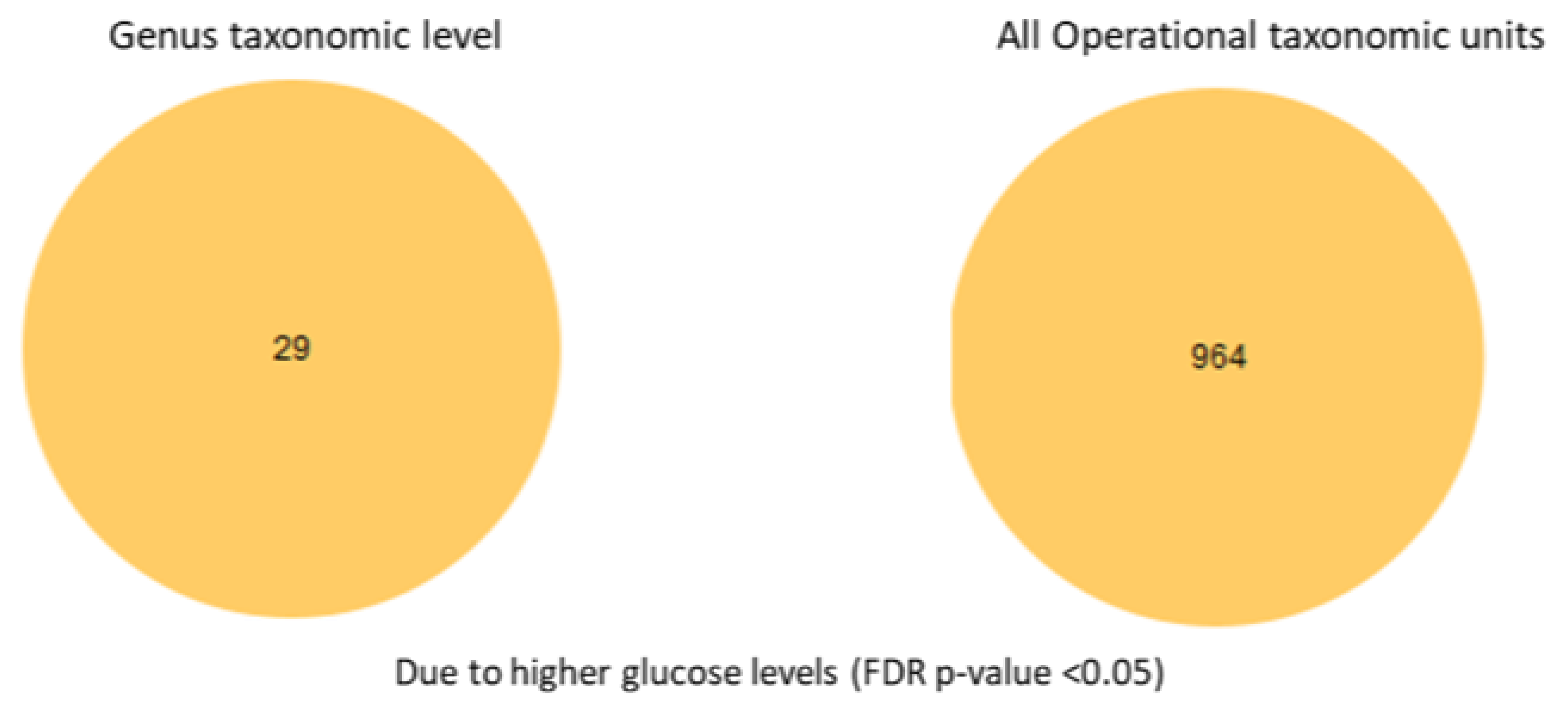

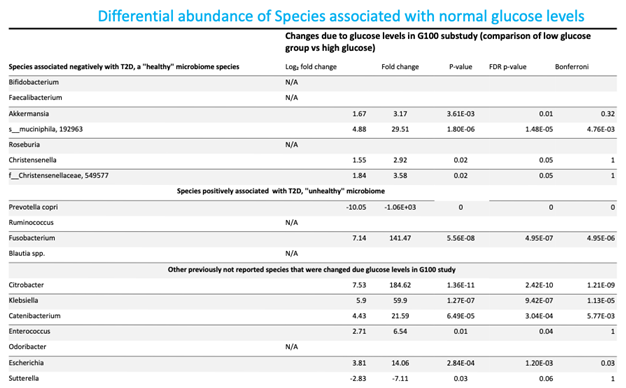

3.3. Differential Abundance Analysis at the Species Level

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, H.; Tremaroli, V.; Schmidt, C.; Lundqvist, A.; Olsson, L.M.; Krämer, M.; Gummesson, A.; Perkins, R.; Bergström, G.; Bäckhed, F. The Gut Microbiota in Prediabetes and Diabetes: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Cell Metab 2020, 32, 379-390.e3. [CrossRef]

- Randeria, S.N.; Thomson, G.J.A.; Nell, T.A.; Roberts, T.; Pretorius, E. Inflammatory Cytokines in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus as Facilitators of Hypercoagulation and Abnormal Clot Formation. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2019, 18, 72. [CrossRef]

- Chakaroun, R.M.; Massier, L.; Kovacs, P. Gut Microbiome, Intestinal Permeability, and Tissue Bacteria in Metabolic Disease: Perpetrators or Bystanders? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1082. [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, R.; Raes, J.; Arumugam, M.; Burgdorf, K.S.; Manichanh, C.; Nielsen, T.; Pons, N.; Levenez, F.; Yamada, T.; et al. A Human Gut Microbial Gene Catalogue Established by Metagenomic Sequencing. Nature 2010, 464, 59–65. [CrossRef]

- Bednarska, N.G.; Håberg, A.K. Understanding Patterns of the Gut Microbiome May Contribute to the Early Detection and Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 134. [CrossRef]

- Stensvold, D.; Viken, H.; Rognmo, Ø.; Skogvoll, E.; Steinshamn, S.; Vatten, L.J.; Coombes, J.S.; Anderssen, S.A.; Magnussen, J.; Ingebrigtsen, J.E.; et al. A Randomised Controlled Study of the Long-Term Effects of Exercise Training on Mortality in Elderly People: Study Protocol for the Generation 100 Study. BMJ Open 2015, 5. [CrossRef]

- Stensvold, D.; Viken, H.; Steinshamn, S.L.; Dalen, H.; Støylen, A.; Loennechen, J.P.; Reitlo, L.S.; Zisko, N.; Bækkerud, F.H.; Tari, A.R.; et al. Effect of Exercise Training for Five Years on All Cause Mortality in Older Adults—the Generation 100 Study: Randomised Controlled Trial. BMJ 2020, 371. [CrossRef]

- Helsedirektorate Arsrapport 2019 Available online: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rapporter/helsedirektoratet-arsrapporter/%C3%85rsrapport%202019%20-%20Helsedirektoratet.pdf/_/attachment/inline/8947572c-7f1f-4b3a-a9dd-6e165cfe014d:acc662d5e305e4c6d0f9e37f2605d8147ae94fd4/%C3%85rsrapport%202019%20-%20Helsedirektoratet.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Stensvold, D.; Viken, H.; Steinshamn, S.L.; Dalen, H.; Støylen, A.; Loennechen, J.P.; Reitlo, L.S.; Zisko, N.; Bækkerud, F.H.; Tari, A.R.; et al. Effect of Exercise Training for Five Years on All Cause Mortality in Older Adults—the Generation 100 Study: Randomised Controlled Trial. BMJ 2020, 371. [CrossRef]

- Santiago, A.; Panda, S.; Mengels, G.; Martinez, X.; Azpiroz, F.; Dore, J.; Guarner, F.; Manichanh, C. Processing Faecal Samples: A Step Forward for Standards in Microbial Community Analysis. BMC Microbiol 2014, 14. [CrossRef]

- IHMS Available online: https://human-microbiome.org/index.php?id=Sop&num=006 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Illumina IMPORTANT NOTICE This Document Provides Information for an Application for 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation Preparing 16S Ribosomal RNA Gene Amplicons for the Illumina MiSeq System.

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glöckner, F.O. Evaluation of General 16S Ribosomal RNA Gene PCR Primers for Classical and Next-Generation Sequencing-Based Diversity Studies. Nucleic Acids Res 2013, 41. [CrossRef]

- Roswell, M.; Dushoff, J.; Winfree, R. A Conceptual Guide to Measuring Species Diversity. Oikos 2021, 130, 321–338. [CrossRef]

- Hurlbert, S.H. The Nonconcept of Species Diversity: A Critique and Alternative Parameters. Ecology 1971, 52, 577–586. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, T.D. and Stephens, R.M. (1990) Sequence Logos A New Way to Display Consensus Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res, 18, 6097-100. - References - Scientific Research Publishing Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=21870 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Multiple Hypothesis Testing in Microarray Experiments on JSTOR Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3182872 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Almudevar, A. Multiple Hypothesis Testing: A Methodological Overview. Methods in Molecular Biology 2013, 972, 37–55. [CrossRef]

- Benjaminit, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol 1995, 57, 289–300. [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y. and Hochberg, Y. (1995) Controlling the False Discovery Rate A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B, 57, 289-300. - References - Scientific Research Publishing Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1425368 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Wu, H.; Lv, B.; Zhi, L.; Shao, Y.; Liu, X.; Mitteregger, M.; Chakaroun, R.; Tremaroli, V.; Hazen, S.L.; Wang, R.; et al. Nature Medicine Microbiome-Metabolome Dynamics Associated with Impaired Glucose Control and Responses to Lifestyle Changes. Nature Medicine | 2025, 31. [CrossRef]

- Keshet, A.; Segal, E. Identification of Gut Microbiome Features Associated with Host Metabolic Health in a Large Population-Based Cohort. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 1–13.

- Ortiz-Alvarez, L.; Xu, H.; Martinez-Tellez, B. Influence of Exercise on the Human Gut Microbiota of Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2020, 11, e00126. [CrossRef]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Franceschi, F.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. What Is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Diet, and Diseases. Microorganisms 2019, 7. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, L.; He, T.; Hu, H.; Song, J.; Cui, C.; Qiao, J.; Qing, L.; et al. Enterotype Bacteroides Is Associated with a High Risk in Patients with Diabetes: A Pilot Study. J Diabetes Res 2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Radjabzadeh, D.; Chen, L.; Kurilshikov, A.; Kavousi, M.; Ahmadizar, F.; Ikram, M.A.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; Zhernakova, A.; Fu, J.; et al. Association of Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes With Gut Microbial Diversity: A Microbiome-Wide Analysis From Population Studies. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4. [CrossRef]

- Ang, W.S.; Law, J.W.F.; Letchumanan, V.; Hong, K.W.; Wong, S.H.; Ab Mutalib, N.S.; Chan, K.G.; Lee, L.H.; Tan, L.T.H. A Keystone Gut Bacterium Christensenella Minuta-A Potential Biotherapeutic Agent for Obesity and Associated Metabolic Diseases. Foods 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Salguero, M. V; Al-Obaide, M.A.I.; Singh, R.; Siepmann, T.; Vasylyeva, T.L. Dysbiosis of Gram-Negative Gut Microbiota and the Associated Serum Lipopolysaccharide Exacerbates Inflammation in Type 2 Diabetic Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Exp Ther Med 2019, 18, 3461. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Xin, Y. Function of Akkermansia Muciniphila in Type 2 Diabetes and Related Diseases. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1172400. [CrossRef]

- Ghotaslou, R.; Nabizadeh, E.; Memar, M.Y.; Law, W.M.H.; Ozma, M.A.; Abdi, M.; Yekani, M.; Kadkhoda, H.; hosseinpour, R.; Bafadam, S.; et al. The Metabolic, Protective, and Immune Functions of Akkermansia Muciniphila. Microbiol Res 2023, 266, 127245. [CrossRef]

- Depommier, C.; Everard, A.; Druart, C.; Plovier, H.; Van Hul, M.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Falony, G.; Raes, J.; Maiter, D.; Delzenne, N.M.; et al. Supplementation with Akkermansia Muciniphila in Overweight and Obese Human Volunteers: A Proof-of-Concept Exploratory Study. Nat Med 2019, 25, 1096-+. [CrossRef]

- Shin, N.-R.; Lee, J.-C.; Lee, H.-Y.; Kim, M.-S.; Whon, T.W.; Lee, M.-S.; Bae, J.-W. An Increase in the Akkermansia Spp. Population Induced by Metformin Treatment Improves Glucose Homeostasis in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Gut 2014, 63, 727–735. [CrossRef]

- Gurung, M.; Li, Z.; You, H.; Rodrigues, R.; Jump, D.B.; Morgun, A.; Shulzhenko, N. Role of Gut Microbiota in Type 2 Diabetes Pathophysiology. EBioMedicine 2020, 51, 102590. [CrossRef]

- Moreira de Gouveia, M.I.; Bernalier-Donadille, A.; Jubelin, G. Enterobacteriaceae in the Human Gut: Dynamics and Ecological Roles in Health and Disease. Biology (Basel) 2024, 13, 142. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).