1. Introduction

The human gut microbiome is critical to maintaining health and longevity by regulating digestion, modulating immune function, and contributing to the production of metabolites [

1]. Recent research has underscored the dynamic nature of this microbial ecosystem, highlighting how its composition and function shift over the human lifespan [

2]. In particular, age-related changes in the gut microbiome have been linked to multiple health outcomes, including disruptions in the microbial balance known as dysbiosis, increased systemic inflammation, and impaired gut barrier function [

3]. These shifts contribute to age-associated conditions and diseases such as increased frailty, metabolic disorders, and chronic inflammation [

3,

4,

5].

Gastrointestinal disorders, including inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome, are also known to profoundly disrupt the gut microbial ecosystem [

6]. These disorders are characterized by dysbiosis, loss of microbial diversity, increased pathogenic species, and compromised gut barrier integrity [

7,

8,

9]. While altered gut microbiomes characterize aging and gastrointestinal disorders, limited research explores how these two factors interact. This is critical to understand since combining the effects of aging in dysfunctional gastrointestinal individuals could accelerate dysbiosis, exacerbate inflammation, and contribute to more severe clinical outcomes.

Existing studies have predominantly focused on age-related microbial changes in healthy individuals or the microbiome alterations associated with specific gastrointestinal disorders [

2,

3,

5,

10]. To our knowledge, no one has investigated how aging influences the microbiome in individuals with pre-existing gastrointestinal conditions. This leaves unanswered questions about how these populations may experience unique microbiome shifts, potentially driving distinct disease trajectories compared to healthy controls. Understanding these compounded effects is crucial for identifying biomarkers of disease progression and potential therapeutic targets that address aging and gastrointestinal compromised individuals [

11].

To address this gap, we investigated age-related ecological and intra-species genomic variation in the gut microbiome using advanced next generation sequencing technique i.e Shotgun metagenomics. Shotgun metagenomics offers a significant advancement over traditional 16S rRNA sequencing by enabling a more comprehensive and high-resolution analysis of the microbiome. While 16S rRNA sequencing targets only a specific region of the bacterial genome and provides limited taxonomic resolution—usually to the genus level—shotgun metagenomics sequences all genomic material present in a sample. This allows for precise species- and strain-level identification, detection of non-bacterial organisms (such as viruses, fungi, and archaea), and functional annotation of microbial genes. Moreover, shotgun metagenomics enables the exploration of metabolic pathways, antibiotic resistance genes, and virulence factors, offering deep insight into the functional potential of the microbial community. This level of detail is crucial for understanding complex host-microbe interactions, nutritional influences, and disease associations in a truly systems-level context [

12,

13]

We studied the gut microbiome of total 54 individuals from different age groups suffering from gastrointestinal disorders. The analysis of the NGS data was carried out using in-house bioinformatic pipeline, PanOmiQ, that performs sequencing read quality control, taxonomic classification, and multi-locus sequence alignment to capture ecological dynamics and genomic variations in the gut microbial population. By characterizing the unique microbial shifts in this gastrointestinal-compromised cohort across different age groups, we aim to provide insight into the mechanisms underlying age-related disease progression in the presence of gastrointestinal disorders. By deepening our understanding of how aging and gastrointestinal disorders synergistically impact the gut microbiome, we hope to contribute to developing microbiome-based interventions that promote healthier aging and improved gut health outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

Sample Data Collection

As part of the BioGut program, clinical samples were received at the Genomics Facility of BioAro Inc. for next generation sequencing (NGS) and results were archived in BioAro Inc data repository with anthropometric measures and medical history of the participants. Informed consent was duly obtained from all participants, with robust measures implemented to ensure the protection of their privacy and confidentiality. In this retrospective study data were collected from the repository of BioAro Inc. for 54 individuals with different age groups ranging from 10-80 years, in accordance with ethical guidelines (HREBA.CHC-25-0013). BioGut or clinic participants' stool samples were received at the BioAro laboratory with their informed consent and prepared for DNA extraction. Genomic DNA was extracted from samples using the Zymo BIOMICS DNA Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research, Cat. No. D4300) following the manufacturer's instructions. The DNA extraction protocol involved cell lysis using enzymatic digestion and bead beating, followed by DNA purification using spin columns and washes. Purified DNA was eluted in DNase-free water. Total 54 participants data was categorized into five age groups; Adult <30: 8 samples; Adulthood 31-40: 11 samples; Adulthood 41-50: 15 samples; Adulthood 51-60: 13 samples; and Adulthood 60+: 7 samples.

Healthy Human Gut Microbiome Samples (Control) Data Collection

Data for 100 healthy control samples, was collected from the human microbiome project site (website URL:

https://hmpdacc.org/), healthy human sample (HHS) study and analyzed with PanOmiQ pipeline for the comparison of the results with gastrointestinal disease groups.

3. Results

Using shotgun metagenomic sequencing approach from MGI, DNBSeq-G400RS Sequencing [

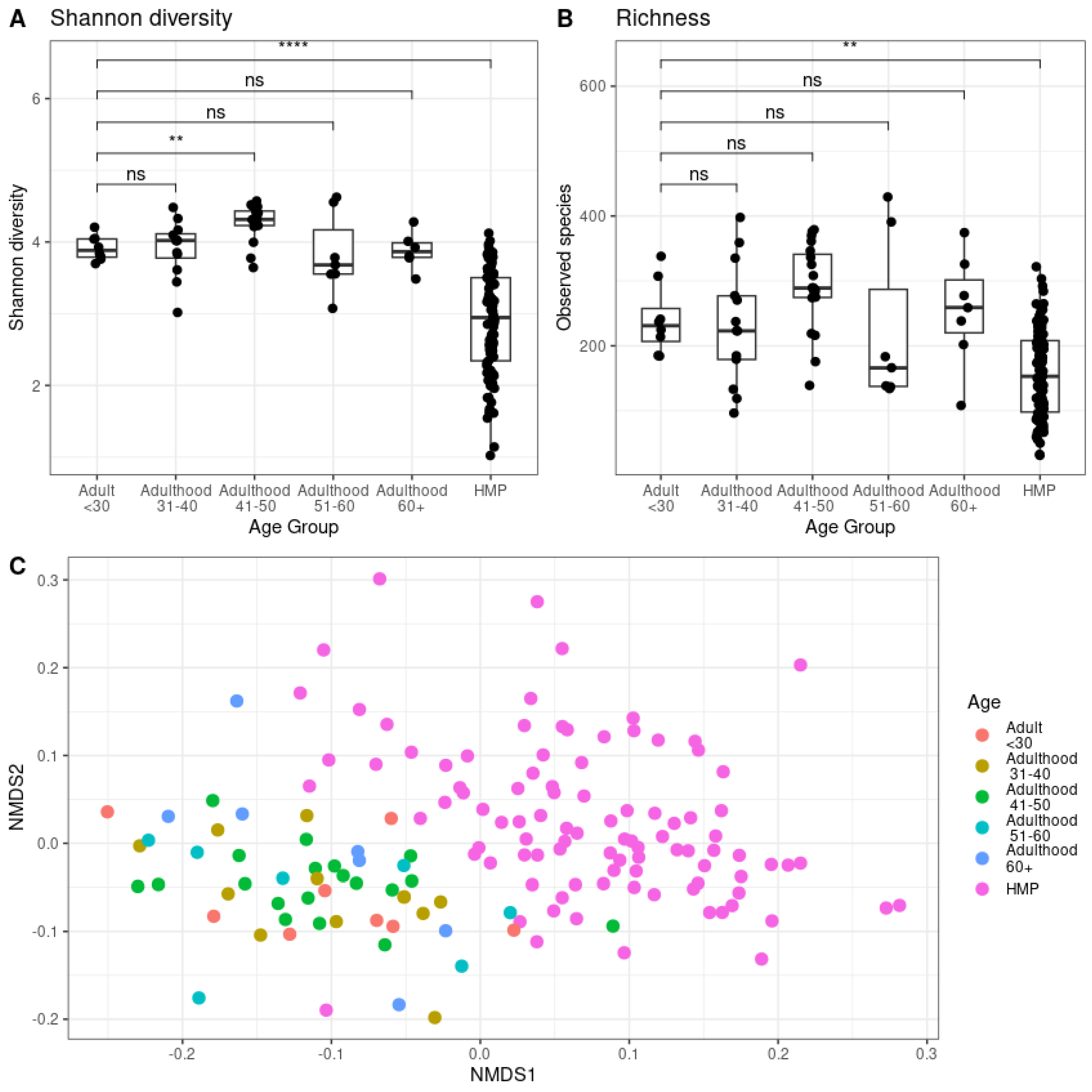

14], for generated high-quality sequencing data with a mean number of reads of 3.2 ± 1.4 million reads per sample. The Shannon diversity (Aplha diversity) analysis was performed to measure the within-sample diversity—how many different species (richness) are present and how evenly distributed (evenness) [

15] Beta diversity was performed to compare the differences in microbial composition between samples of different groups. Richness refers the number of unique species (or taxa) in the samples of different groups [

16] (). Analysis of this data revealed significant (p<0.01 and p< 0.001) differences in Shannon diversity of gut microbiome between young adults (Age group <30 years old), middle-aged adults (41-50 years old) and healthy human microbiome samples (HMP) (

Figure 1A). However, a significant difference (p<0.01) was observed in the total number of microbial species (richness) between healthy and gastrointestinal-compromised samples (

Figure 1B). Additionally, beta-diversity analysis performed using non-metric multidimensional scaling plot, demonstrated two distinct microbial clusters represented by healthy and gastrointestinal-compromised samples (

Figure 1C).

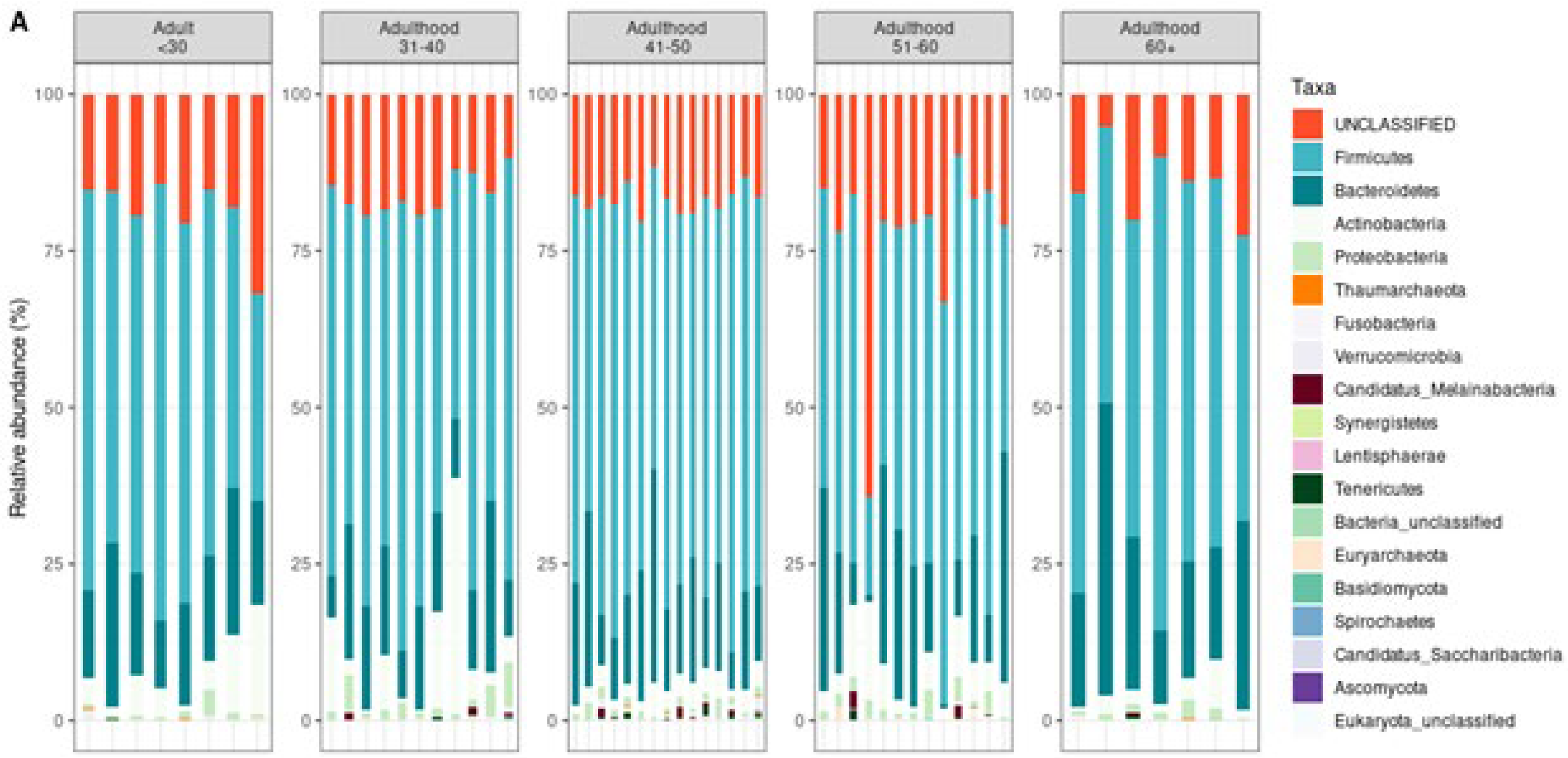

The taxonomic classification helps in understanding the composition and diversity of microbial communities in a sample. At the phylum level, it provides a broad overview of dominant microbial groups (e.g.,

Firmicutes,

Bacteroidetes,

Proteobacteria), while deeper levels like genus and species offer more specific insights into individual organisms and their potential roles in identifying shifts in microbial composition associated with health or diseas [

13] At the taxonomic level comparison (

Figure 2), we observed a distinct microbial profile at the phylum level.

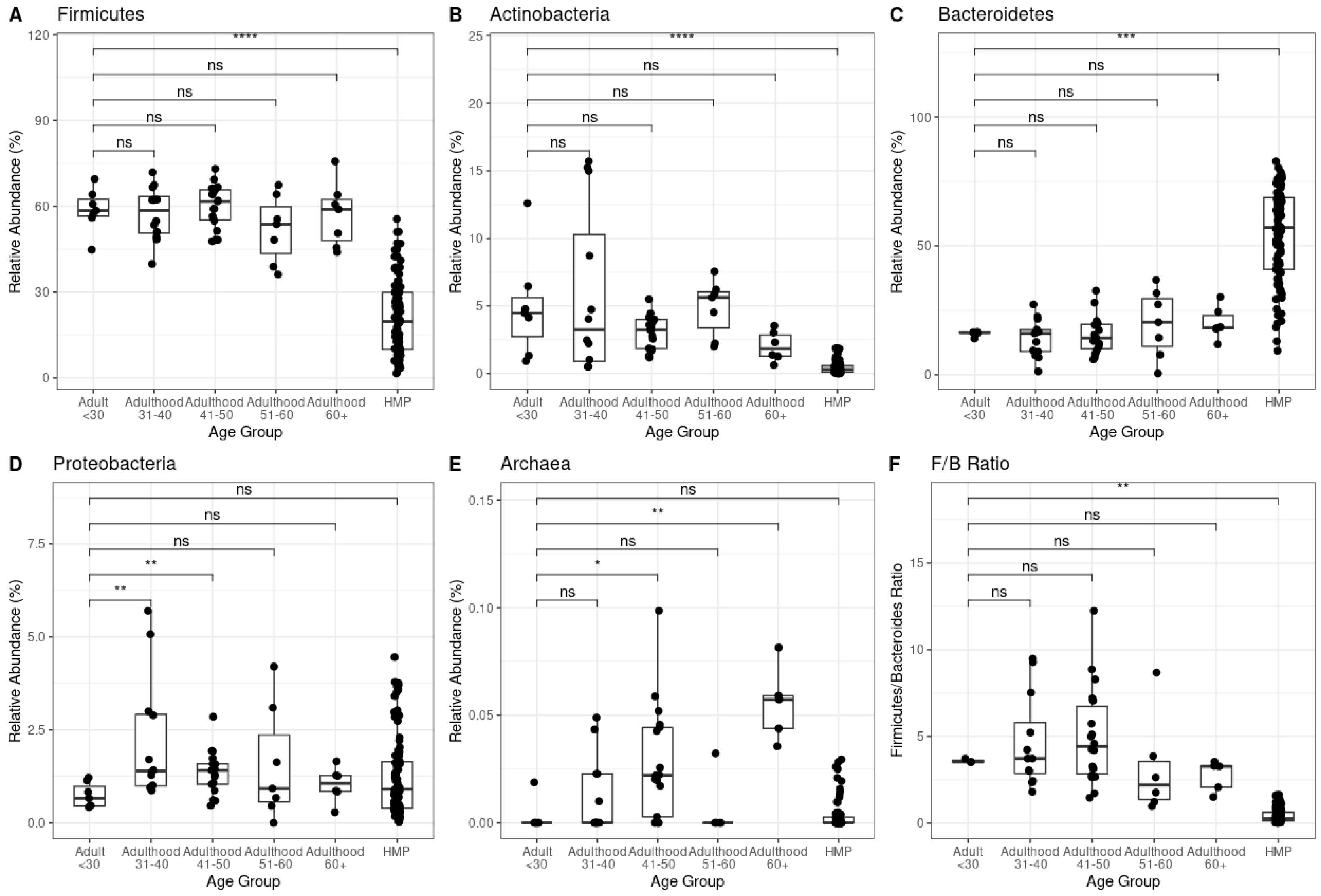

We observed that Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio from gastrointestinal-comprised samples significantly differed (p< 0.01) from healthy samples (

Figure 3A-C, F). However, Proteobacteria phyla and Archaea kingdom d not show any significant difference between condition groups but showed highly significant differences p< 0.01 between age groups within the gastrointestinal-compromised cohort (Figure3D-E).

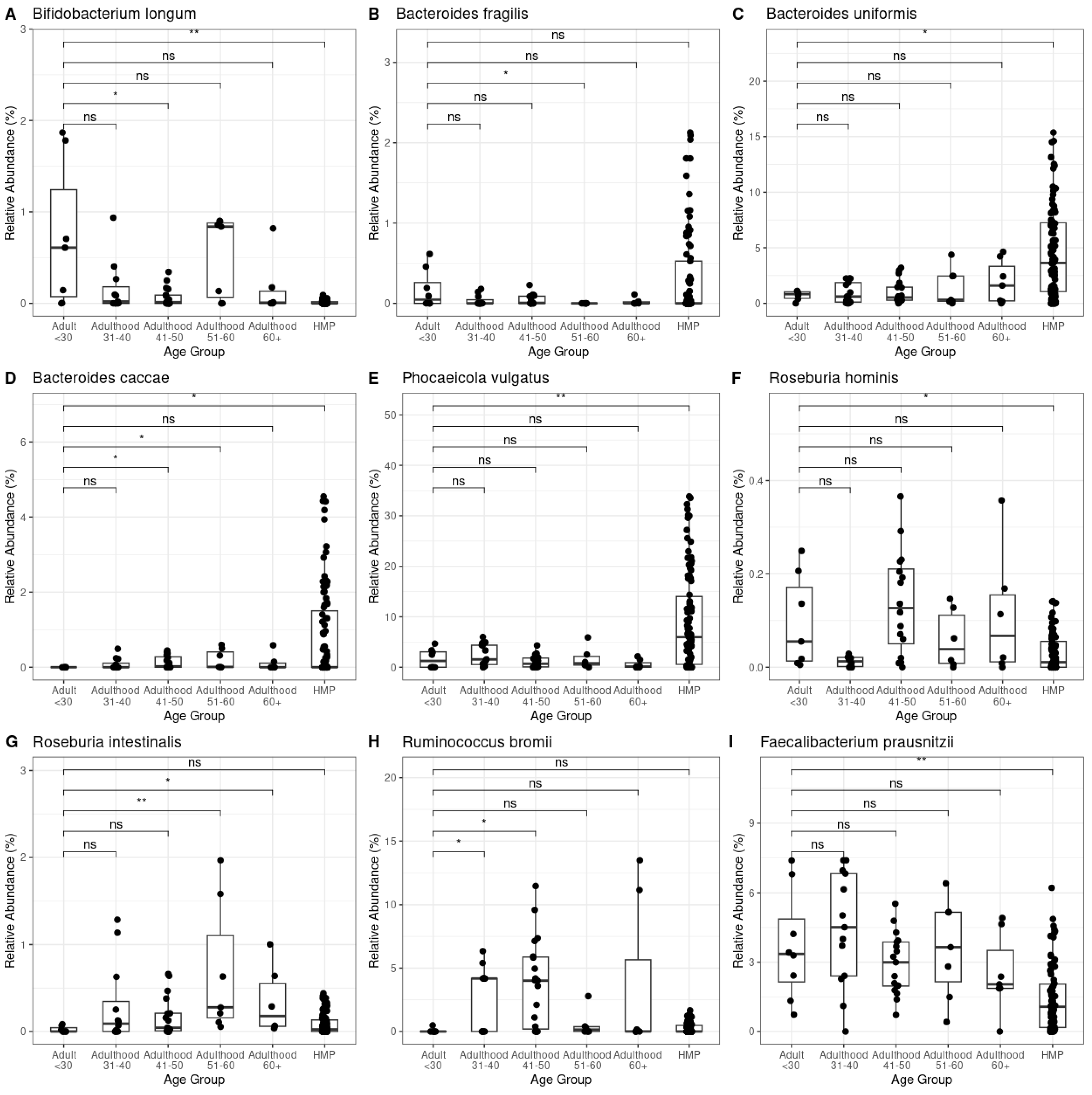

Given the observed changes at the phylum level and in the Archaea relative abundance across both age and control groups, we investigated whether these shifts were associated with variations in keystone species (key microorganisms to maintain the gut ecosystem) within the gut microbiota [

17]. We analyzed the relative abundance of over 20 keystone bacterial and archaeal species, identifying associations with different age groups and healthy control group. Notably,

Bifidobacterium longum and

Bacteroides caccae exhibited significant differences between the < 30 years old adult group and the older groups, as well as the healthy subjects group (

Figure 4A, D, Kruskal – Wallis test, p-value < 0.05). Additionally,

Bacteroides uniformis, Phocaeicola vulgatus, Roseburia hominis and

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii displayed significant differences exclusively in the healthy control group, indicating a potential role in maintaining gut health in unaffected individuals. (

Figure 4C, E, F, I; Kruskal – Wallis test, p-value < 0.05). Among individuals with gastrointestinal disorders,

Bacteroides fragilis Roseburia intestinalis and

Ruminococcus bromii significantly differed between different age groups (

Figure 4F, G, H; Kruskal – Wallis test, p-value < 0.05).

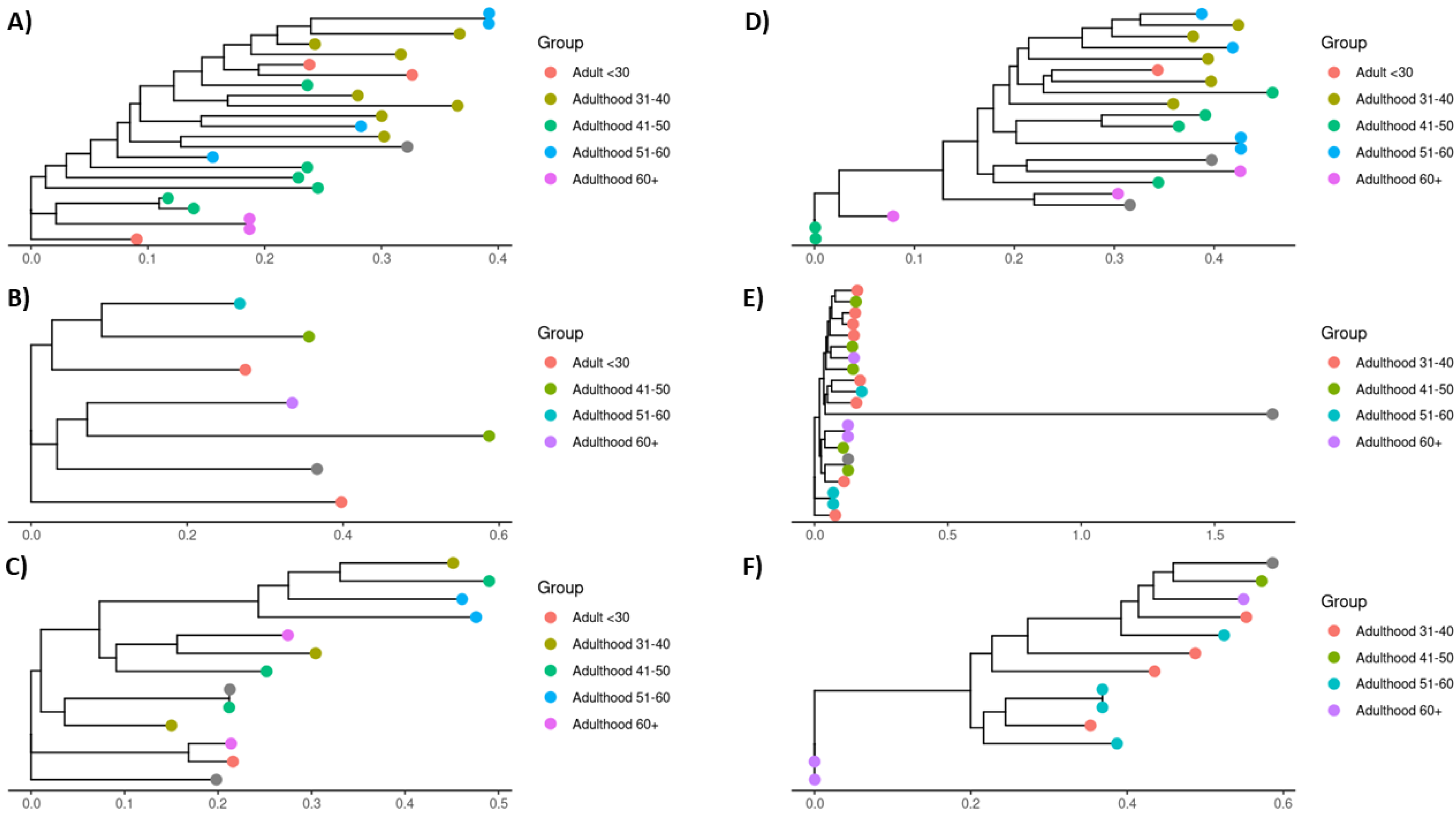

To explore whether the observed shifts in keystone species abundance were associated with intra-species genetic variations, we conducted a multi-locus sequence alignment analysis of the bacterial strains identified in each sample [

18]. This analysis aimed to uncover any genetic difference linked to aging that could explain the ecological shifts observed [

4]. However, no significant intra-species genetic variation correlated with age groups (

Figure 5).

Given this, we hypothesized that the increase in abundance in these keystone species likely represents an ecological response in the microbial community to the aged gut environment (changes in strain frequency), rather than changes driven by intra-species genetic variation [

19]. Previous studies have demonstrated that increases in the keystone species

Bacteroides caccae and

Roseburia intestinalis can reduce inflammation by modulating interactions between intestinal epithelial cells and gut microbes [

20,

21]. Therefore, we propose that increasing these species in older individuals suffering from gastrointestinal diseases may be a compensatory mechanism aimed at mitigating the pro-inflammatory state commonly associated with both aging and gastrointestinal disorders.

It is important to note that potential confounding factors, such as diet, medications, lifestyle, and other comorbidities, may have influenced the gut microbiota composition in both healthy control and gastrointestinal-compromised individuals [

22,

23]. While these variables were not the focus of this study, future research should account for these potential confounders to isolate the specific effects of aging on the gut microbiome.

4. Discussion

These results underscore the utility of our bioinformatics pipeline PanOmiQ in uncovering complex microbiome dynamics in aging and disease contexts. Further functional annotation of microbial genes in these populations is necessary to elucidate the mechanisms underlying these ecological shifts and their potential role in the progression of age-related diseases. Our findings open the door to identifying novel microbial signatures and pathways that could serve as therapeutic targets to delay or prevent the onset of age-related diseases in vulnerable populations, particularly those with gastrointestinal disorders.

The results of this study demonstrate significant changes in the gut microbiome composition across different ages and health conditions. The observed shifts in microbial diversity, richness, and beta diversity suggest a distinct microbial profile in healthy individuals compared to those with gastrointestinal disorders. At the taxonomic level, we observed significant differences in Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratios between healthy and gastrointestinal-compromised samples, aligning with previously reported, where dysbiotic states are characterized by increased firmicutes / Bacteroidetes ratio [

6,

21].

The increased abundance of keystone species such as

Bifidobacterium longum, Bacteroides caccae, Roseburia intestinalis, Ruminococcus bromii, and

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in older individuals with gastrointestinal disorders may reflect a compensatory mechanism designed to reduce the pro-inflammatory state typically linked to both aging and gastrointestinal condition [

20]. Further functional annotation of microbial genes associated with aging in this population may reveal potential implications for understanding the mechanisms underlying age-related disease progression. This research opened the possibility to seek and identify novel microbial signatures and pathways that may serve as potential therapeutic targets to help prevent or slow the progression of age-related diseases in this vulnerable population [

25,

26].

This study highlights the increase in relative abundance of Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria and Archaea in disease conditions. Notably, these findings could represent a characteristic marker of the progression of gastrointestinal diseases during the aging process and health assessment in individuals with gastrointestinal disorders.

Finally, the lack of significant intra-species genetic variation suggests that the differences in keystone species abundance are likely driven by ecological factors rather than genetic adaptation to the aged gut [27]. This finding reveals the importance of exploring microbiome dynamics beyond genetic factors and focusing on how environmental changes in the host influence microbial composition and function.

It is essential to note that potential confounding factors, such as diet, medications, lifestyle, and other comorbidities, may have influenced the gut microbiota composition. Future research should account for these potential confounders to isolate the specific effects of aging on the gut microbiome in gastrointestinal-compromised individuals.

5. Conclusions

These findings highlight the effectiveness of our bioinformatics pipeline, PanOmiQ, in revealing the intricate dynamics of microbiomes associated with aging and disease. By leveraging this tool, we were able to detect subtle ecological shifts within microbial communities. However, more functional annotation of microbial genes across the populations under study is necessary to completely comprehend the biological significance of these changes. Such analyses will help clarify the molecular mechanisms driving these microbiome alterations and their possible contributions to the onset and progression of age-related diseases Crucially, our study establishes the foundation for the identification of new microbial biomarkers and metabolic pathways, which could be developed into therapeutic targets aimed at delaying or preventing age-associated conditions—particularly in at-risk groups, such as individuals suffering from gastrointestinal disorders.

Future research should also aim to understand better the specific host-microbiome interactions driving these compensatory microbiota changes. Expanding research on the role of keystone species, such as Bacteroides caccae and Roseburia intestinalis, could yield valuable insights into how the gut microbiome helps regulate inflammation and overall health in aging individuals. Identifying microbial pathways with therapeutic potential could provide new avenues for preventing or treating age-related health issues, ultimately improving the quality of life for aging populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.D.D.A., M.B.T and R.S.; methodology, F.D.D.A, PB, KD, RC, and M.B.T.; software, F.D.D.A; validation, F.D.D.A., M.B.T, P.B., K.D. and R.S.; formal analysis, F.D.D.A, M.B.T and R.S; investigation, F.D.D.A, and M.B.T; resources, A.K. and C.H.; data curation, F.D.D.A, P.B, K.D. and RC; writing—original draft preparation, F.D.D.A.; writing—review and editing, M.B.T, R.S.. and A.K; visualization, F.D.D.A.; supervision, M.B.T, R.S., C.H. andA.K.; project incharge, M.B.T.; funding acquisition, A.K. and C.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MITACs, grant number IT37639

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

This is a collaborative project between BioAro Inc, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada and University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada.

References

- Gilbert, J.A.; Blaser, M.J.; Caporaso, J.G.; Jansson, J.K.; Lynch, S.V.; Knight, R. Current Understanding of the Human Microbiome. Nat Med 2018, 24, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haran, J.P.; McCormick, B.A. Aging, Frailty, and the Microbiome: How Dysbiosis Influences Human Aging and Disease. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, T.S.; Shanahan, F.; O’Toole, P.W. The Gut Microbiome as a Modulator of Healthy Ageing. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 19, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleman, F.D.D.; Valenzano, D.R. Microbiome Evolution during Host Aging. PLoS Pathog 2019, 15, e1007727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragonnaud, E.; Biragyn, A. Gut Microbiota as the Key Controllers of “Healthy” Aging of Elderly People. Immunity & Ageing 2021, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.-X.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in Health and Diseases. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanning, N.; Edwinson, A.L.; Ceuleers, H.; Peters, S.A.; De Man, J.G.; Hassett, L.C.; De Winter, B.Y.; Grover, M. Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2021, 14, 1756284821993586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehandru, S.; Colombel, J.-F. The Intestinal Barrier, an Arbitrator Turned Provocateur in IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 18, 83–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.-H.; Lee, K.; Shim, J.O. Gut Bacterial Dysbiosis in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Case-Control Study and a Cross-Cohort Analysis Using Publicly Available Data Sets. Microbiology Spectrum 2023, 11, e02125–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadzadeh, R.; Mahnert, A.; Shinde, T.; Kumpitsch, C.; Weinberger, V.; Schmidt, H.; Moissl-Eichinger, C. Age-Related Dynamics of Methanogenic Archaea in the Human Gut Microbiome: Implications for Longevity and Health 2024.Wu, W.K.K.; Yu, J. Microbiota-Based Biomarkers and Therapeutics for Cancer Management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024, 21, 72–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan R, Rani A, Metwally A, McGee HS, Perkins DL. Analysis of the microbiome: Advantages of whole genome shotgun versus 16S amplicon sequencing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun [Internet]. 2015 Jan 22 [cited 2025 Jul 14];469(4):967. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4830092/.

- Knight R, Vrbanac A, Taylor BC, Aksenov A, Callewaert C, Debelius J, et al. Best practices for analysing microbiomes. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2018 16:7 [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Jul 14];16(7):410–22. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41579-018-0029-9.

- Anslan, S.; Mikryukov, V.; Armolaitis, K.; Ankuda, J.; Lazdina, D.; Makovskis, K.; Vesterdal, L.; Schmidt, I.K.; Tedersoo, L. Highly Comparable Metabarcoding Results from MGI-Tech and Illumina Sequencing Platforms. PeerJ 2021, 9, e12254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim BR, Shin J, Guevarra RB, Lee JH, Kim DW, Seol KH, et al. Deciphering Diversity Indices for a Better Understanding of Microbial Communities. J Microbiol Biotechnol [Internet]. 2017 Dec 28 [cited 2025 Jul 14];27(12):2089–93. Available from: https://www.jmb.or.kr/journal/view.html?doi=10.4014/jmb.1709.09027.

- Lozupone C, Knight R. UniFrac: a New Phylogenetic Method for Comparing Microbial Communities. Appl Environ Microbiol [Internet]. 2005 Dec [cited 2025 Jul 14];71(12):8228. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1317376/.

- Fisher, C.K.; Mehta, P. Identifying Keystone Species in the Human Gut Microbiome from Metagenomic Timeseries Using Sparse Linear Regression. PLoS One 2014, 9, e102451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Míguez, A.; Beghini, F.; Cumbo, F.; McIver, L.J.; Thompson, K.N.; Zolfo, M.; Manghi, P.; Dubois, L.; Huang, K.D.; Thomas, A.M.; et al. Extending and Improving Metagenomic Taxonomic Profiling with Uncharacterized Species Using MetaPhlAn 4. Nat Biotechnol 2023, 41, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagpal, R.; Mainali, R.; Ahmadi, S.; Wang, S.; Singh, R.; Kavanagh, K.; Kitzman, D.W.; Kushugulova, A.; Marotta, F.; Yadav, H. Gut Microbiome and Aging: Physiological and Mechanistic Insights. Nutr Healthy Aging 4, 267–285. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, F.; Cheng, Y.; Ruan, G.; Fan, L.; Tian, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Chen, D.; Wei, Y. New Pathway Ameliorating Ulcerative Colitis: Focus on Roseburia Intestinalis and the Gut–Brain Axis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2021, 14, 17562848211004469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, H.; Saier, M.H. Gut Bacteroides Species in Health and Disease. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1848158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gacesa, R.; Kurilshikov, A.; Vich Vila, A.; Sinha, T.; Klaassen, M. a. Y.; Bolte, L.A.; Andreu-Sánchez, S.; Chen, L.; Collij, V.; Hu, S.; et al. Environmental Factors Shaping the Gut Microbiome in a Dutch Population. Nature 2022, 604, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ren, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, B.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, B.; Liu, W.; et al. Lifestyle Patterns Influence the Composition of the Gut Microbiome in a Healthy Chinese Population. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 14425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So, D.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Whelan, K. Probiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Review of Mechanisms and Effectiveness. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2023, 39, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renson, A.; Mullan Harris, K.; Dowd, J.B.; Gaydosh, L.; McQueen, M.B.; Krauter, K.S.; Shannahan, M.; Aiello, A.E. Early Signs of Gut Microbiome Aging: Biomarkers of Inflammation, Metabolism, and Macromolecular Damage in Young Adulthood. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2020, 75, 1258–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, W.; Lu, W. Achieving Healthy Aging through Gut Microbiota-Directed Dietary Intervention: Focusing on Microbial Biomarkers and Host Mechanisms. Journal of Advanced Research 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Good, B.H.; Rosenfeld, L.B. Eco-Evolutionary Feedbacks in the Human Gut Microbiome. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 7146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).