1. Introduction

Entropy, as defined in classical thermodynamics [

1], quantifies the degree of disorder or randomness in a system and serves as a measure of thermal energy unavailable for performing work. The second law of thermodynamics posits that in a reversible process, the entropy of the universe remains constant, whereas in irreversible processes, it invariably changes. In statistical mechanics, entropy is further understood as the logarithmic measure of the number of microscopic configurations corresponding to a macroscopic state. These foundational concepts have long been instrumental in describing physical systems, yet they leave open questions about entropy’s role in less conventional contexts, such as gravitational phenomena.

This paper aims to extend the classical discussion of entropy by examining its interplay with gravitational repulsion, an unconventional yet increasingly significant concept, particularly in the context of cosmological phenomena such as the accelerating expansion of the universe. By doing so, we explore new dimensions of entropy and its implications for fundamental physics.

Before delving into the relationship between entropy and gravitational effects, it is essential to first revisit the conventional understanding of thermal energy and its influence on matter. Thermal energy is traditionally viewed as energy carried by infrared (IR) radiation within the electromagnetic spectrum. For instance, the Sun transfers thermal energy to the Earth predominantly via IR radiation. Temperature, as a measure of thermal energy, is inferred through observable changes in material properties, such as volume expansion or electrical resistance, which vary in proportion to thermal energy input. This proportionality, however, is depended by the material's specific heat capacity (SHC).

However, there remains a significant lack of understanding about how heat is stored within the matter, particularly at the atomic level. While specific heat capacities can be measured and quantified, the mechanisms by which heat energy is stored within an object remain poorly understood. For example, during state changes in matter, heat is absorbed or released without altering temperature—an effect known as latent heat. However, the atomic-scale dynamics underlying latent heat and its relationship to thermal energy remain elusive.

In classical theory, the thermal energy of a system is often equated with the kinetic energy of its particles [

2]. Yet, the precise mechanisms by which thermal (infrared) energy is converted into particle kinetic energy, encompassing translational, rotational, or vibrational motion, are not well-defined. While quantum mechanics provides insights into how electrons absorb energy from electromagnetic radiation, it falls short of explaining how this energy manifests as increased kinetic energy of atoms or particles in the system.

By addressing these gaps, this paper aims to enhance our understanding of thermal energy and its broader relationship with entropy, particularly in the context of gravitational repulsion. This exploration builds upon classical perspectives and lays the groundwork for a deeper investigation into entropy’s role in shaping the fundamental laws of physics.

2. Predominant Existing Theory Relating Kinetic Energy and Thermal Energy

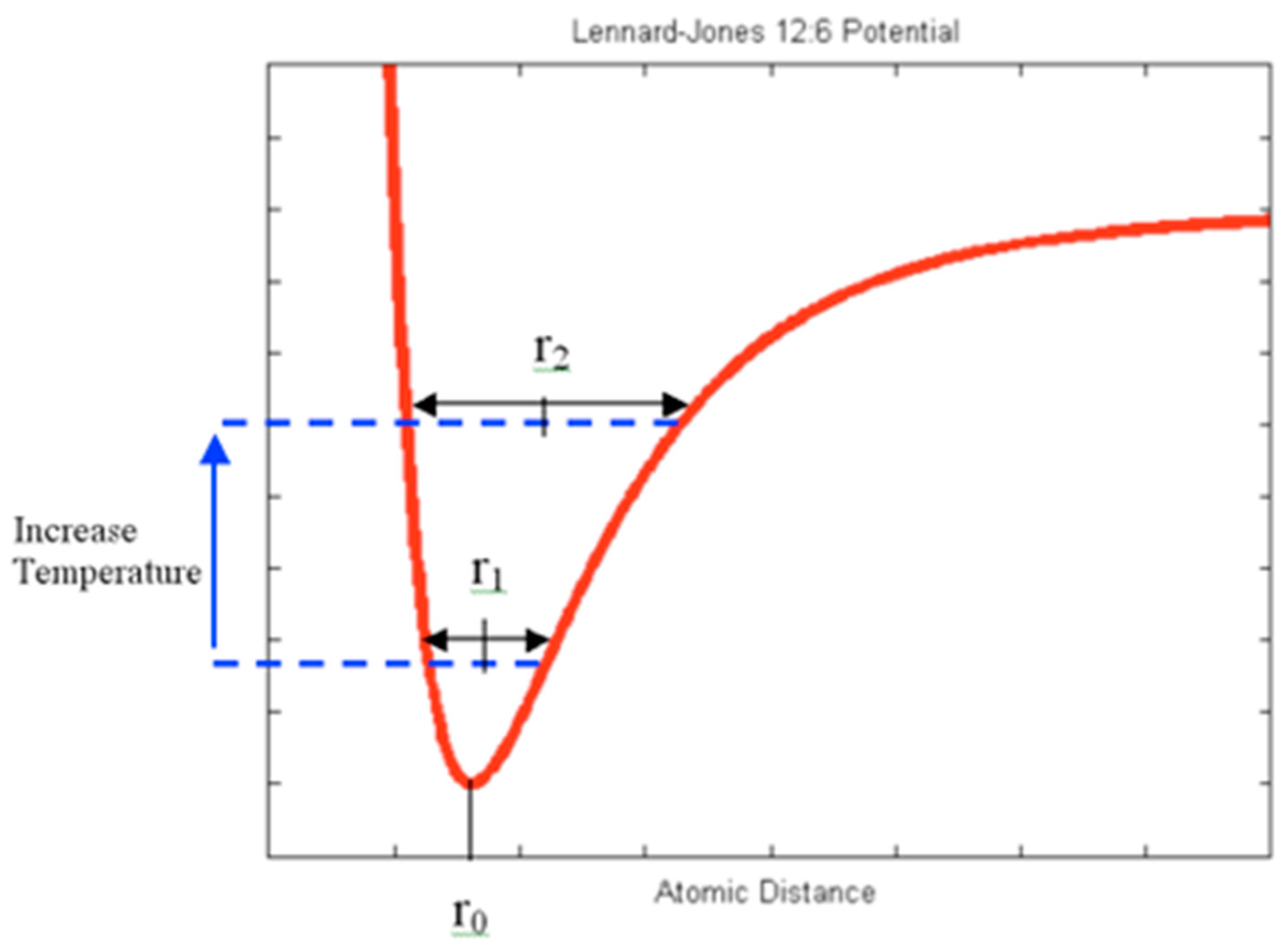

Atoms in a solid typically reside at equilibrium positions, corresponding to the minima of their potential energy curves [

3]. When the temperature increases, the amplitude of atomic vibrations also increases. Due to the symmetry of these vibrations around a median position and the inherent asymmetry of the potential energy curve, an atom’s average position shifts further from its neighbors. This shift results in a new average interatomic distance, a phenomenon illustrated by the Lennard-Jones potential curve (

Figure 1), which demonstrates the effect of anharmonicity in the potential energy.

Classical physics attributes thermal expansion to the asymmetry of the potential energy curve. This explanation effectively describes how increased thermal energy influences atomic positions and contributes to the macroscopic expansion of solids.

3. Limitations of Existing Theories

3.1. Do Fundamental Forces Depend on Temperature?

The four fundamental forces—gravitational, electromagnetic, strong nuclear, and weak nuclear—are not inherently dependent on thermal energy or temperature. At the interatomic distances relevant to solids:

Strong and weak nuclear forces; at the interatomic distances found in solid matter, the strong and weak nuclear forces are not relevant, as their influence is confined to subatomic scales.

Gravitational and electromagnetic forces are the primary contributors to atomic cohesion.

However, neither gravitational nor electromagnetic forces, as defined, vary with temperature. This raises a fundamental question: how does increasing temperature, which induces thermal expansion, affect the forces acting between atoms?

3.2. Is Interatomic Bonding Potential Related to Temperature?

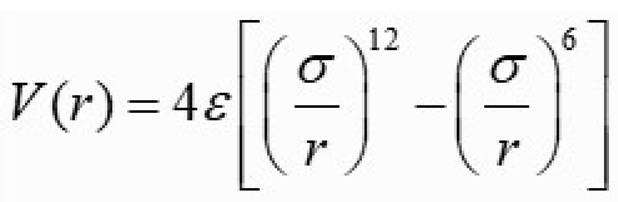

The bonding potential V(r), commonly described by the Lennard-Jones potential curve [

4,

5],

depends on interatomic distance r, the potential well depth ε (usually referred to as ‘dispersion energy’), and σ is the distance at which the particle-particle potential energy V is zero (often referred to as ‘size of the particle’).

Importantly, it could, nevertheless, be observed that Lennard-Jones potential curve is not temperature dependent!

This limitation suggests that while the curve effectively models interatomic interactions, it fails to explain how thermal energy alters bonding potential or contributes to thermal expansion.

3.3. Does Entropy Explain Thermal Expansion?

Thermodynamic explanations often attribute thermal expansion to increasing entropy, which reflects the system's growing randomness as thermal energy is added. Rising entropy is thought to drive molecules apart, thereby causing expansion.

However, existing theories do not adequately address:

4. Key Challenges in Existing Theories

The classical view that neither fundamental forces nor bonding potential depend on thermal energy creates gaps in explaining:

Moreover, several critical aspects remain unresolved:

Specific heat capacity (SHC): How thermal energy is stored at the atomic level and its dependence on SHC.

Latent heat: A convincing definition of its association with state changes in matter.

Thermal energy and temperature: The precise relationship between these concepts.

To separate two atoms bound by attractive forces, an external force must be applied. Fundamentally, the attractive forces arise from either gravitational or electromagnetic interactions. However, gravitational forces are negligible compared to electromagnetic forces (gravitational force is extremely weak - about 10−36 weaker than the electromagnetic force), which raises further ambiguities, as not all atoms in matter are bound by electromagnetic interactions alone.

5. Toward a New Perspective: Gravitational Repulsion

The incorporation of gravitational repulsion, alongside gravitational attraction, may provide a more comprehensive framework for addressing these ambiguities. By examining the thermodynamic implications of gravitational interactions, this paper explores an alternative approach to understanding the interplay between thermal energy, entropy, and atomic cohesion.

6. What Causes Gravitational Repulsion?

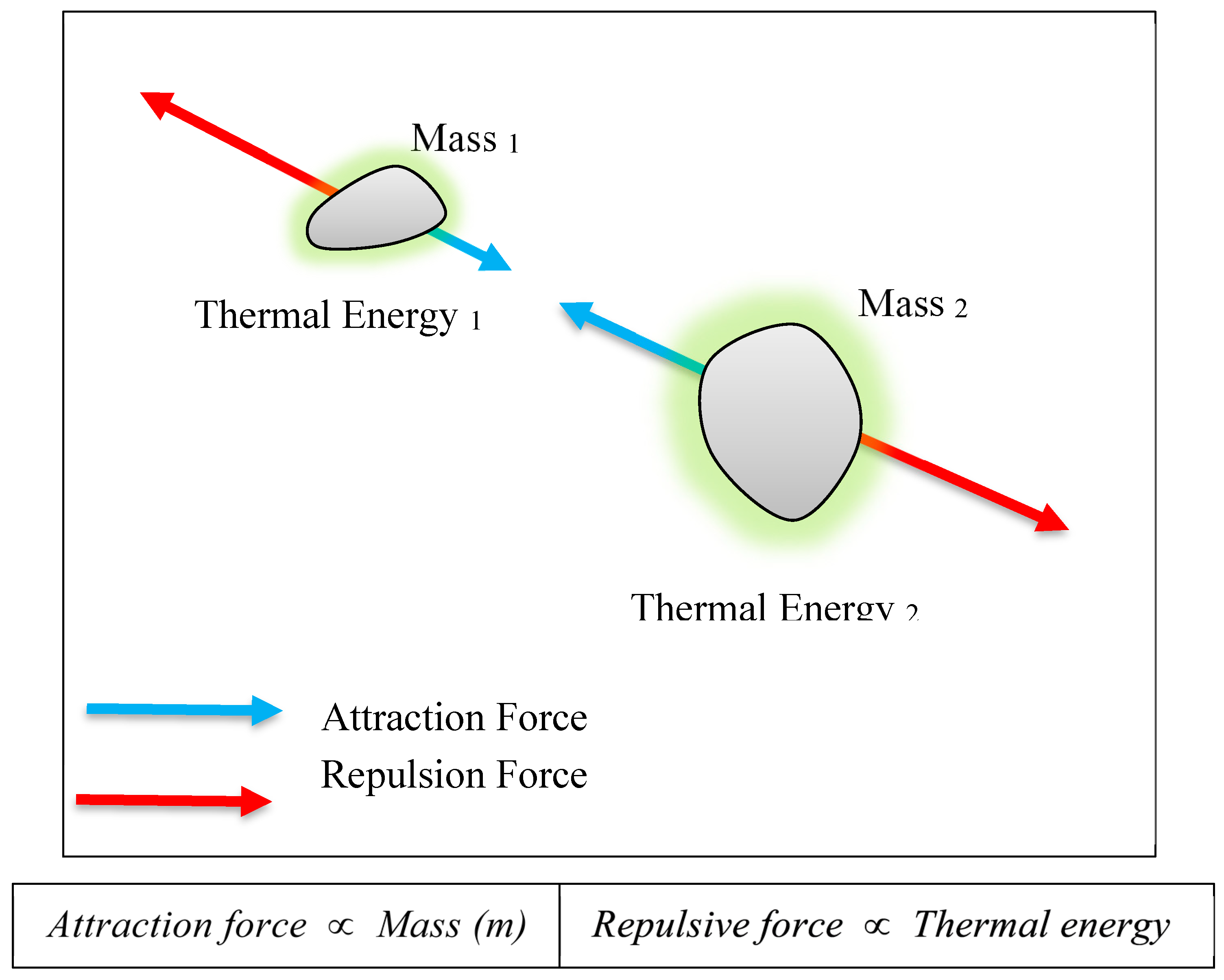

A new fundamental force, referred to as

Gravitational Repulsion Force (or Antigravity) [

6,

7], is proposed to be inherently repulsive and directly proportional to the thermal energy of matter. As thermal energy increases, this repulsive force intensifies, causing atoms or molecules to move farther apart. Unlike gravitational attraction, which arises from mass, gravitational repulsion is proposed to be driven by thermal energy. This dynamic is illustrated in

Figure 2.

7. Explanation of Gravitational Repulsion and Gravitational Attraction

Research on gravitational repulsion indicates that both gravitational attraction and repulsion forces are significant within gas molecules [

8]. For example, at approximately 333 K and 1 atm, these forces are estimated to be on the order of 10

32and 10

29, respectively. These magnitudes far exceed the gravitational forces traditionally calculated between gas molecules.

Classical theory misinterprets the observed gravitational force as a weak force because it fails to account for the fact that the observed force in nature is the result of both gravitational attraction and repulsion. These opposing forces are nearly equal and exist in a state of dynamic equilibrium. This equilibrium manifests across both micro and macro scales.

If the combined attractive forces (gravitational attraction + electromagnetic force) outweigh the repulsive force, interatomic or intermolecular bonds remain intact, and thermal expansion occurs as the temperature rises. This expansion reflects the manifestation of thermal energy through the alteration of interatomic distances.

8. Redefining Entropy with Gravitational Repulsion

Thermal energy in matter is proposed to influence gravitational repulsion, altering the balance between attraction and repulsion forces. This interplay affects interatomic and intermolecular distances, impacting the bonds within matter. The contribution of thermal energy to the repulsion force distributes matter across space, suggesting that thermal energy represents unusable energy required to maintain a specific state of matter.

This interpretation aligns with the thermodynamic definition of entropy:

"Entropy is the disorder or randomness in a system and a measure of the system's thermal energy that is unavailable for work." (i.e. This thermal energy is used to maintain the distance/space among particles in the matter)

The framework of gravitational repulsion offers a new perspective on entropy, linking it to the balance of fundamental forces influenced by thermal energy.

9. Entropy and Gravitational Dynamics

Gravitational forces, traditionally understood as purely attractive, are reimagined within this framework to include repulsive effects, particularly in the context of cosmological phenomena. Entropy in gravitational systems exhibits unique characteristics:

-

Gravitational Clustering and Entropy Increase

Conventional gravitational interactions lead to clustering, which may locally decrease entropy but increase it globally by forming more complex structures.

-

Repulsion and Entropy Redistribution

Gravitational repulsion, as observed in the accelerating expansion of the universe [

7], redistributes entropy by spreading matter and energy across larger volumes. This redistribution increases the overall entropy of the system.

-

Cosmological Implications

In an expanding universe dominated by repulsive forces [

7], entropy associated with phenomena like the cosmic horizon and vacuum energy plays a pivotal role. A deeper understanding of these contributions is essential for developing a comprehensive thermodynamic model of the cosmos.

10. Conclusions

Revisiting the concept of entropy in the context of gravitational repulsion opens new avenues for theoretical exploration. By bridging thermodynamics and gravitational forces, this perspective enhances our understanding of entropy’s role in the universe. Future research should focus on refining mathematical models that link entropy with gravitational dynamics and on gathering observational evidence to validate these theoretical constructs.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

G. Piyadasa was financially supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada. The author acknowledges A. Gole and U. Annakkage for continual support of this work. Extensive edits by D. Darshi De Saram and G. S. Palathirathna Wirasinha improved the quality of this paper.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings are included as references within the article. Additional data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Van Wylen, G.J.; Sonntag, R.E. Fundamentals of Classical Thermodynamics; Wiley: 1973.

- Halliday, D.; Resnick, R.; Walker, J. Fundamentals of Physics; Wiley: 2013.

- Xiangliang; Siagian, S.; Basar, K.; Sakuma, T.; Takahashi, H.; Igawa, N.; Ishii, Y. Inter-atomic distance and temperature dependence of correlation effects among thermal displacements. Solid State Ionics 2009, 180, 480–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Wendland, M. On the history of key empirical intermolecular potentials. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2023, 573, 113876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenhard, J.; Stephan, S.; Hasse, H. On the History of the Lennard-Jones Potential. Annalen der Physik 2024, 536, 2400115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamini Piyadasa, C.K. Antigravity, a major phenomenon in nature yet to be recognized. Physics Essays 2019, 32, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piyadasa, C.K.G. Antigravity, an answer to nature’s phenomena including the expansion of the universe. Advances of High Energy Physics, Special issue : Dark Matter and Dark Energy in General Relativity and Modified Theories of Gravity 2020, 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piyadasa, C. Insights of Gravitational Phenomena: A Study Applying Thermodynamic Properties of Gases. Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).