1. Introduction

The rapid development of pLEO constellations of small satellites has greatly provided communications and navigation services [

1,

2], and [

3]. These recent studies suggest that the global coverage provided by these pLEO constellations brings unprecedented opportunities for alternative positioning, navigation, and timing (AltPNT) solutions. According to GNSS, one-way time-of-flight-based navigation services require close monitoring of stable clocks, from which ranging signals are generated. Moreover, multiple, highly stable, microwave clocks onboard each satellite are further integrated with a time-keeping system. Both aspects of overcoming the behavior of satellite clocks and assembling with laboratory-based clocks to produce a timescale are paramount to tracking GNSS signals from ground reference stations around the world and the corrections for each satellite clock concerning the reference timescale distributed to users [

4,

5], and [

6].

Note that the principles behind the concept of operations for GNSS, including large and heavy clocks onboard each satellite, monitoring them from the ground, and uploading clock corrections to each satellite for distribution to the user segment, are not suitable for smaller LEO spacecraft with much shorter orbital lifetimes. However, observing each onboard clock in the pLEO constellation requires extensive tasking responsibilities from the ground-monitoring network due to the need for a global navigation service from LEO regimes. To efficiently tackle the first challenge, the foundation of the underlying GNSS timescales must be rethought from scratch. The assembly of multiple low-size, weight, and power (SWaP) clocks appears more suitable than a single high-performance clock. As for the second challenge, a new conformance framework for seamless realizations and interactions of composable and reference timescales is needed in a distributed architecture.

To this end, one of the promising paths to address the issues mentioned earlier is to adopt two-way time and frequency transfers between pLEO platforms, which facilitate the use of low SWaP clocks without resorting to large-scale ground monitoring and/or GNSS availability. Such a concept will prove to be essential to leveraging the extensive connectivity among the platforms already in place for various primary data transport applications [

7] and [

8]. As expected, radio frequency antenna and onboard terminals equipped on each pLEO platform will provide in-plane and cross-plane connections [

9]. In particular, the use of networks consisting of inter-satellite links as a media to interconnect the different pLEO platforms enables data transports, ranging measurements, and clock comparisons. It is clear that by relying on inter-satellite links, the realization of clock comparisons among small atomic clocks onboard each pLEO satellite offers potential reductions of ground monitoring requirements, allowing differential clock phase measurements to be directly input into clock ensembling algorithms [

10]. Such a capability becomes critical to supporting the on-demand generation of local realizations of pLEO time (pLEOT), i.e., a constellation timescale analogous to Global Positioning Systems time or GPST.

This article is organized as follows. As discussed in

Section 2, it turns out that the control engineering principles would provide answers to the fundamental question of how each participating pLEO platform could meet ad-hoc clock data transfer requests, by promoting autonomy increase in reprogrammability for integrated broadcasting signals for integrity, robustness, and security expected.

Section 3 describes a pLEO timescale concept, including its critical clock dynamics and frequency standards of the varying types of participant low SWaP clocks, in an attempt to create an autonomous and robust pLEO timescale that may be capable of becoming Master Clock reference signals should the need arise. It explores a networked clock system of a finite number of free-running clocks onboard cooperating pLEO platforms and related by clock-to-clock difference measurements. Clock difference measurements are then coordinated by multi-way time transfer and synchronization. In

Section 4, the implicit ensemble mean (IEM) estimation is proven to be indispensable when forming a paper clock running onboard an anchor platform within the pLEO constellation. Every corrected clocked in the pLEO constellation can now represent the IEM as accurately as possible. As shown in

Section 5, the concept of synchronization of satellites within the pLEO constellation with the pLEOT requires a real clock onboard each platform to be steered against the paper clock for the realization of the composite clock. Consequently, network update rates with distributed IEM information are essential to steering commands with minimal attention for an IEM realization.

Section 6 introduces a novel clock steering technique based on the MCV control theory, which can lead to a better understanding of stochastic control for autonomous realizations of the IEM timescale onboard each separate platform with higher performance and robustness in stochastic clock anomalies. Lastly,

Section 7 offers some remarks and conclusions.

3. pLEO Timescale Development

The development of pLEOT requires an accurate, robust, and stable timescale. Once determined, all local clocks within the pLEO constellation will be synchronized to this system time, i.e., pLEOT. In any existing GNSS system like GPS, the ground monitor network must determine the correction values for each satellite clock relative to the system time, e.g., GPST or UTC. These timing offsets are then uploaded to the constellation and broadcast to terrestrial users in the navigation message. Any anomaly of one satellite clock may affect the system time performance for all terrestrial users. Therefore, it is critical that the timing onboard each satellite is robust and reliable. As in the case of pLEO constellation, a stable onboard timing reference is not available, an alternative to improving the stability of the onboard timing is applying a clock ensembling technique to the set of clocks. Different clock types show superior performance on different averaging intervals. Furthermore, adding several clocks of engagement to the mixed ensemble achieves robustness and resiliency of the timescale as all clocks of one type act as active redundancies.

The feasibility and suitability of combining different clock types within a mixed ensemble using a Kalman filter approach allows for generating a timescale leveraging the advantages of the individual clocks, resulting in a solution of the composite clock that performs better than the best clock of the ensemble [

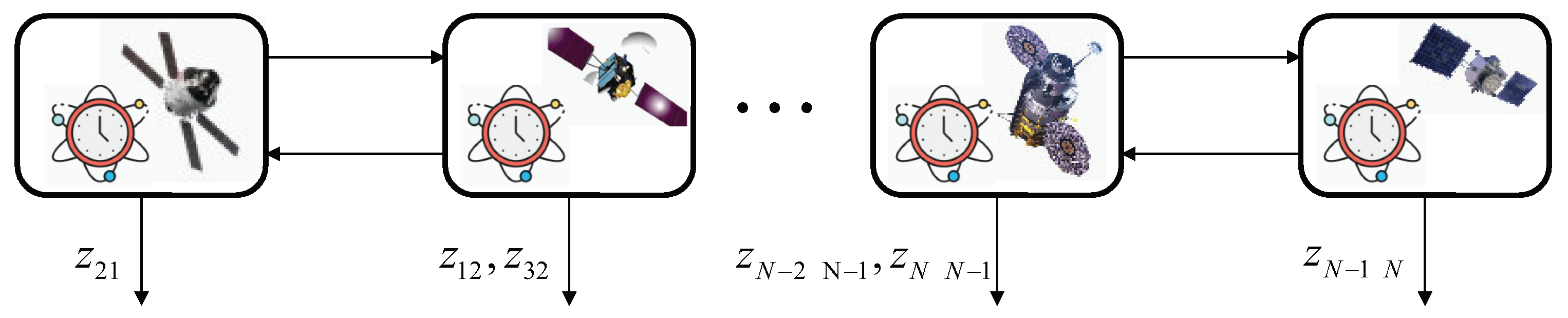

11]. As illustrated in

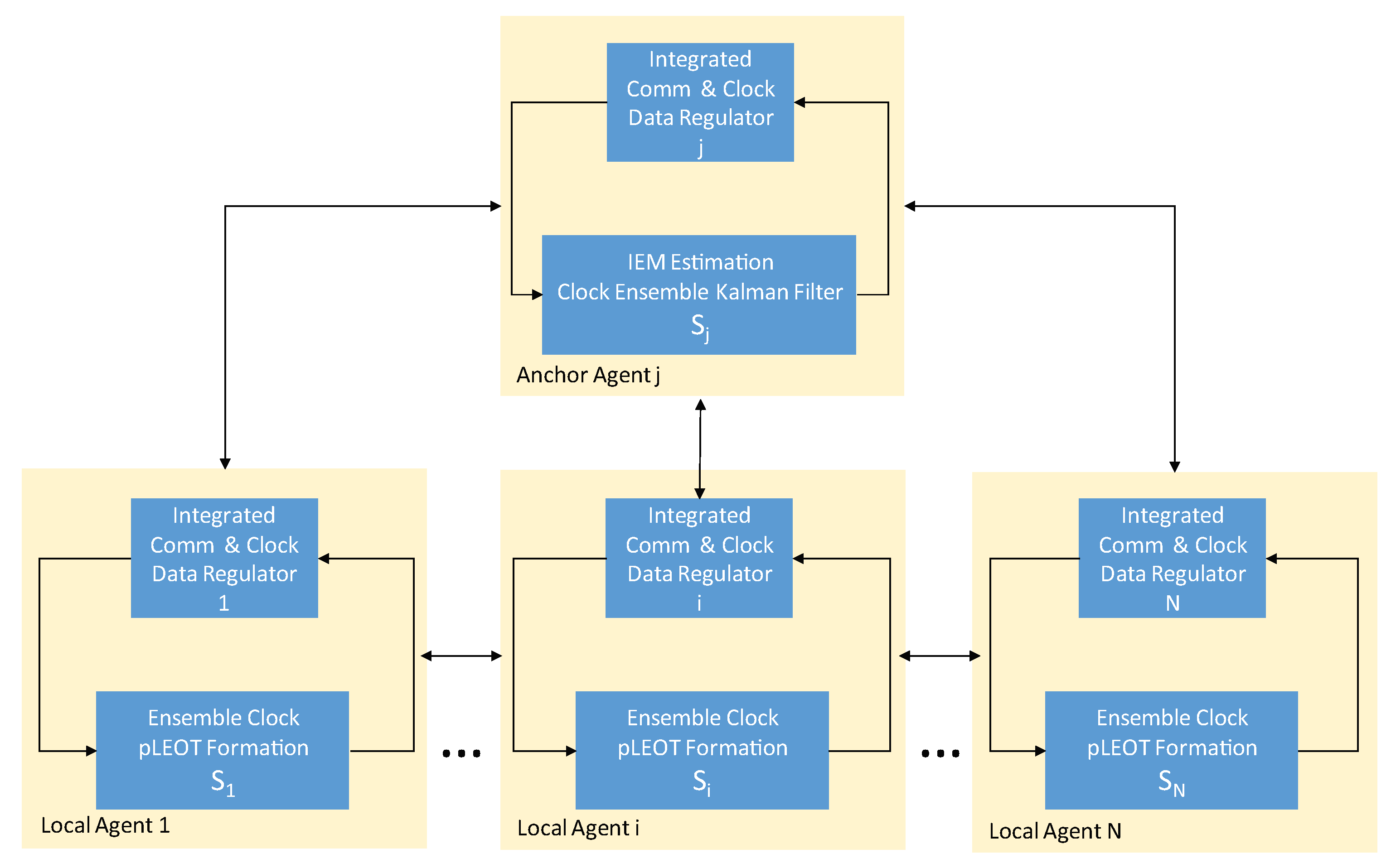

Figure 5, the conceptual architecture of a pLEOT timescale across any pLEO constellations is proposed to explore the capability concept of using all participating platforms, existing satellite communications, and inter-satellite measurements for onboard realizations of pLEOT, each using its own local low noise oscillator together with a numerically controlled oscillator signal synthesis.

3.1. Independent Physical Clocks Onboard Distributed Platforms

To approach the development of an ensemble timescale for pLEOT, usual state-space models for modern atomic clocks in a system of

N independent physical clocks are considered. In such models as depicted in [

12], it is necessary to consider no more than 3-state polynomial processes driven by white noises, involving, e.g., the phase,

, the frequency,

, and the frequency drift,

together with random walk noise processes associated with the

i-th member clock and

. Therefore, the mathematical description of member clocks onboard each platform that relates to the states is given by

where

and

are successive sample times related by the uniform rate

, e.g.,

According to (

26)-(28), each state of the actual clock approximating the behavior of a theoretical ideal clock, evolves from

to the next

by absorbing a random shock driven by the aggregate process noise consisted of

,

, and

. More specifically, they are the white frequency noise, random walk frequency noise, and the random run, respectively. The covariance of the process noise is given by

where the diffusion coefficients

,

, and

are

for

, and thus, driving the fundamental noises. Of note, the smaller the process noise covariance of an actual clock, the better the clock’s performance.

3.2. A Theoretical Ideal Clock

Brought together, an ideal clock is thus characterized by the fact that it has no process noise. In particular, an ideal zeroeth clock with the states

,

, and

is defined by the same dynamic model (

26)-(28) except that its process noises are zero, i.e.,

. Henceforth, it follows that

In other words, the physical clock processes could have been seen as deviations from the ideal clock. This view portrays that the essential role of physical clocks is to provide information on the state of an ideal clock.

3.3. Inter-Platform Measurements Enabled by High-Precision Time Synchronization

With regards to the principle of clock ensemble with measurements, the orbiting clocks are first measured against one of the ensemble clocks by clock-to-clock difference measurements. In

Figure 6, the measurements are on differences between the first states of two ensemble clocks. Actual measurements are triggered by events as determined by the physical clocks’ holdover performance. Later on, such measurements are next fed into a Kalman filter together with the extension of the covariance reduction to account for the unobservability of the clock system of

N independent clocks considered herein, wherein the sense, only the equivalent of

are separately observable from measurements.

When implementing a clock ensemble, the inputs to the clock ensemble Kalman filter are clock-to-clock difference measurements from each bi-directional radio link. For instance, differential phase measurements output from each platform between onboard

ith and

jth clocks are given by

where

is a zero-mean Gaussian measurement noise with its covariance adjusted for the behavior of the difference between clocks

i and

j.

In practice, it is also important to realize that clock measurements are likely affected by platform dynamics and relativistic effects, e.g., a phase shift between two measurements traversing in opposite directions in the same closed path, also known as the Sagnac effect [

13]. For the application of timescale realizations in pLEO, the Sagnac effect needs to be compensated for inter-platform time synchronization and thus, differential phase measurements.

In [

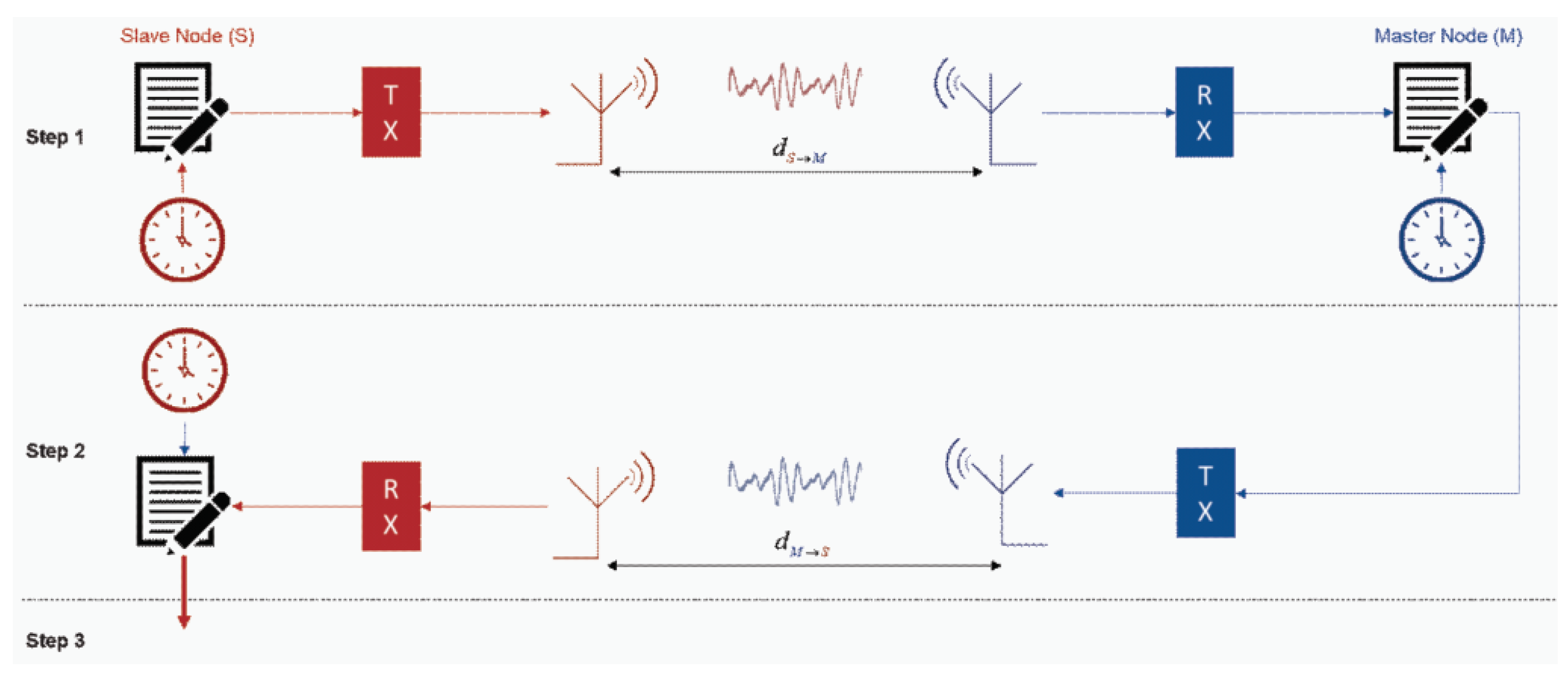

14], one immediately observes that an enhanced multi-way time-transfer (EM-WaTT) solution was proposed to handle dynamic time-coordinated situations, where inter-satellite link delays are not identical in inter-platform measurements. As shown in

Figure 7, EM-WaTT has three steps, assuming the slave platform,

j, and master platform,

i can exchange timing information via wireless inter-platform communications.

Step 1. The slave platform, j launches its time synchronization protocol by sending a message included with the transmit time stamp, to the master node, i. Upon receiving the message, the master platform, i will add the receive time stamp, on the master clock to the message.

Step 2. The master platform, i immediately sends the updated message back to the slave platform, j, which adds the receive time stamp, on the slave clock to the received message.

Step 3. The slave platform,

j will then perform the clock adjustment based on the updated message, i.e.,

where

and

denote the distances between the platforms at the transmission time of the slave and master platforms, respectively.

and

are the transmit and receive processing times of the slave platform,

j. Likewise,

and

are the receive and transmit processing time of the master platform,

i. In practical applications, these processing times are fixed on local signal processing clocks with finite clock cycles. Lastly, the speed of the radio wave is denoted by the speed of light,

c.

Thus, the clock adjustment,

at the slave platform,

j is

where

and

are the relative position and velocity vectors of the slave platform,

j with respect to the master platform,

i which are operated under the dot product of two vectors.

3.4. Generation of Multi-Platform Clock Ensemble

Recapitulating, the challenge in the timescale problem for an ensemble timescale that is composed of a clock system of separate and independent clocks as in the case of deployed AltPNT satellite systems, is to estimate the states of each of the ensemble members. Thus, clock-to-clock difference measurements between ensemble members are immediate and used to estimate the states of each member clock with respect to any one of the real clocks of the system, i.e., real clocks are random processes with non-zero process noises. Motivated by the foundational work in [

15], some key points are reviewed here with an emphasis placed on the relativization of two clocks

i and

j. Typically, the goal is to estimate the clock difference states given the model of (

34)-(36) with each measurement originally representing a difference between the readings of two clocks.

3.5. Kalman-Filter Based Clock Ensemble Solution

Under linear and Gaussian estimation environments, the Kalman filter estimates and covariances at time

provide a sufficient statistic for the clock system given all clock-to-clock measurements up to time

.

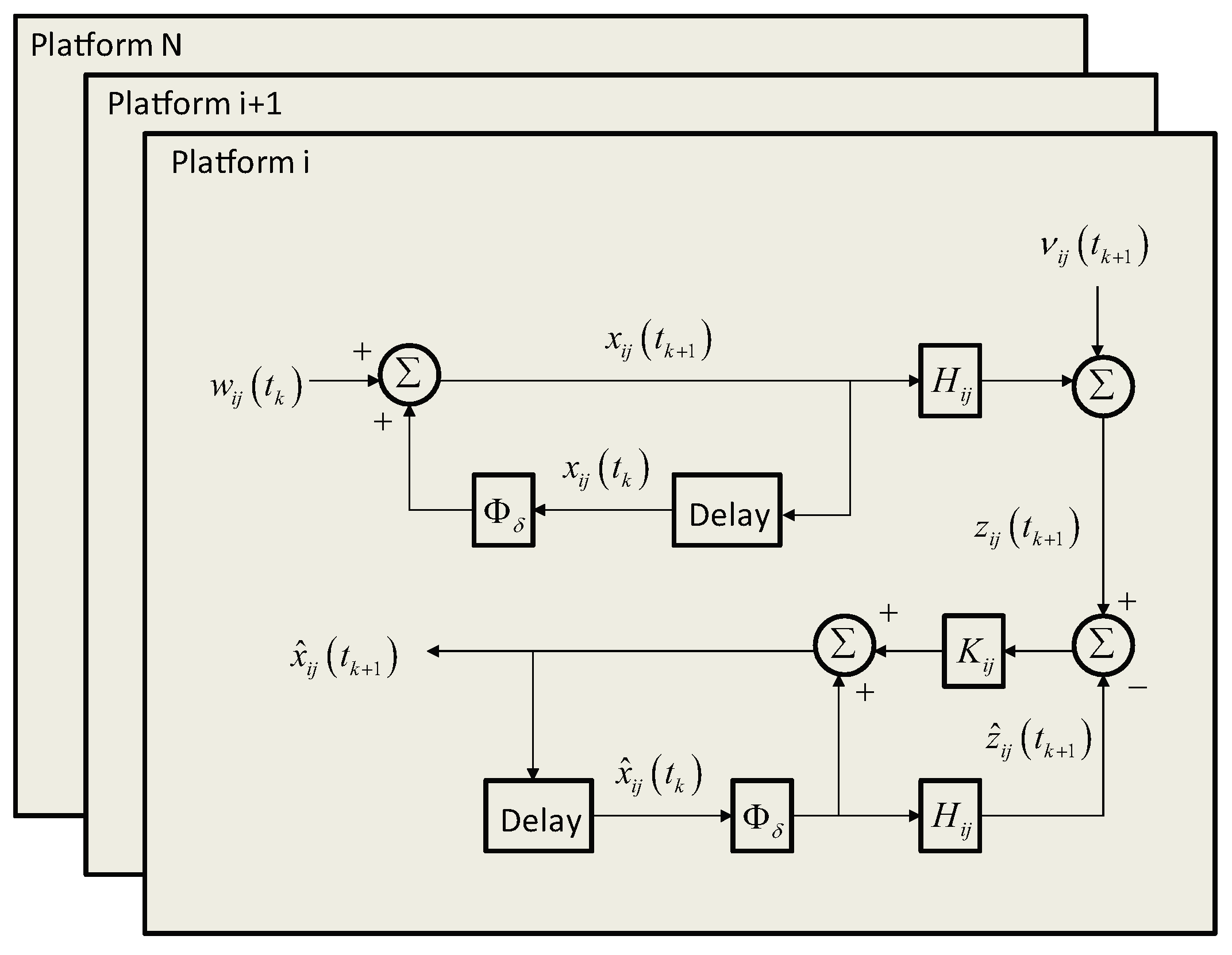

Figure 8 illustrates an approach to designing a Kalman filter- based clock ensemble.

It is necessary to define a state vector that describes the time difference states among these onboard timing systems

the noise vector,

that causes the clock states to evolve

and the state transition matrix that depends on the uniform sampling rate,

and contains the clock dynamics

Thus, the basic dynamical system (

34)-(36) is now rewritten as

Of note, the process noise,

is Gaussian with zero mean and covariance matrix,

which is the sum of

and

that are the process noise covariances specifically to each clock. The computation of these process noise covariances from Allan deviation values associated with an oscillator is described in [

16].

Additionally, the error-covariance matrix associated with the filtered estimate of

,

is given by

which can be computed recursively; just prior to a measurement and just after a measurement, e.g.,

and

.

Interestingly enough, the filtered estimate,

uses information from the measurement equation, e.g.,

where

is the observation matrix of 1 and

is a Gaussian noise with zero-mean and covariance of

.

Finally, the mean-squared filtered estimator of

,

, written in the predictor-corrector format, is

and the Kalman gain,

is specified by the set of relations

Substituting (

40) into (

43), the estimate of random shocks is

3.6. The Basic Timescale Equations

With multiple clocks onboard in a pLEO constellation, the effect of clock errors or failures can be detected and mitigated by analyzing the behavior of clock phase shocks across the relative phase measurement sets. In particular, when the clock difference process is completed for all clocks

and

, then the true behavior for the individual clock phase shocks can be examined by solving

N simultaneous equations for the

N phase shocks, i.e.,

Now, it should be realized that of all the phase shocks estimated as in (

50), the individual clock phases are given

Interestingly enough, the above result reveals another appealing feature of the proposed timescale problem: in each iteration, there is insufficient information to estimate the phase states of the individual clocks since the prior frequency state, and frequency drift state, are unknown. Yet, according to the previous result as can be seen in (48), the difference between frequency shocks is known and thus, it is necessary to estimate the individual frequency shocks for each clock. In a similar situation, the requirement applies to the individual frequency drift random shocks for each clock.

Recall that there are only

simultaneous equations for

N unknowns. The ambiguity herein is eliminated by making the same assumption about the frequency and frequency drift shocks that was made about the phase shocks in (

49)

It is easy to see that using the result (48), both frequency and frequency drift random shocks can be obtained for each clock

Consequently, one can obtain the solutions for the frequency and frequency aging by inserting the values for the random shocks from the equations (54) and (

55) into the equation (

40)

and

In essence, the algorithm for clock ensemble of (52), (

57), and (

58) starts with initial values for three states, i.e.,

,

, and

. Then, for each iteration, the phase, frequency, and frequency drift states are created when the weights associated with the phase, frequency, and frequency drift are set according to satisfying the limit theorem that the sum of the weighted random shocks approaches zero as the number of the clocks gets large.

5. Networked Control Systems with Communication Delays

As already mentioned in the previous section, the clock ensemble Kalman filter is processed at time discretization, seconds. The clock-to-clock difference data between the OCXO onboard platform i and the IEM is measured every seconds and subsequently is sent to every participating platform i and . The control value for the onboard steering is calculated and applied to the MPS after the free selectable control interval time is reached.

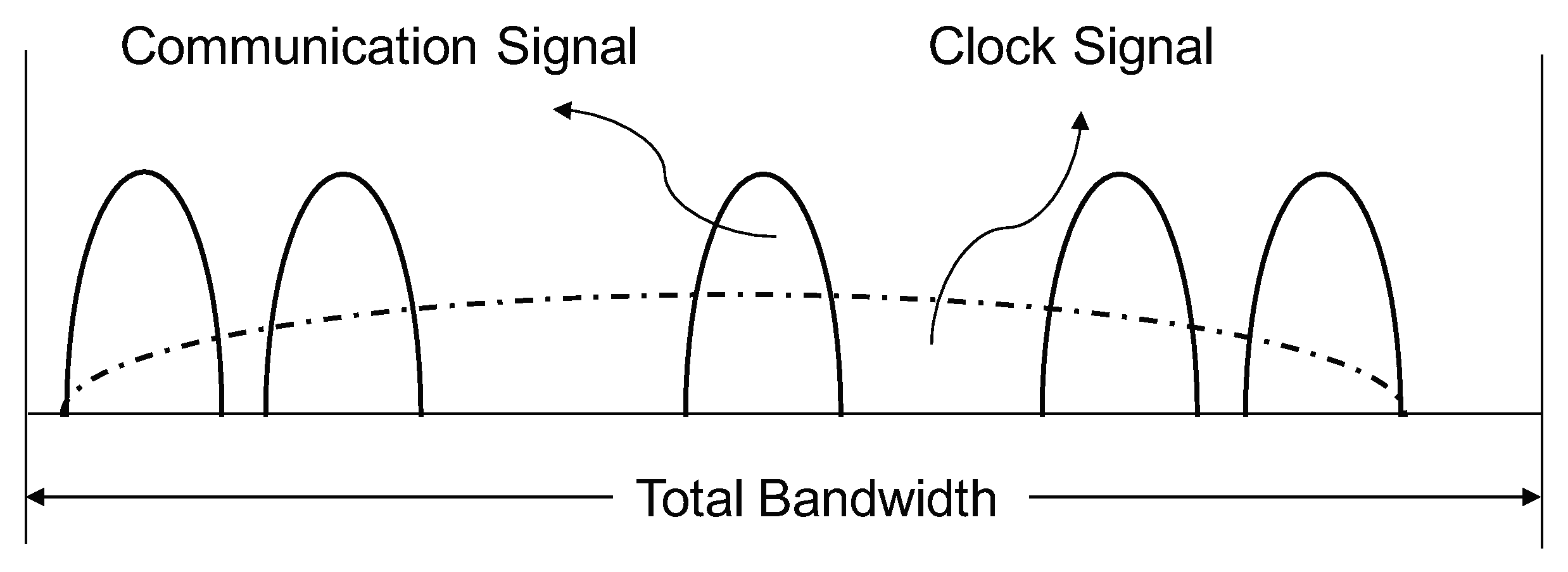

Given the foregoing, it is clear that the reduction of bandwidth necessitated by leveraging existing inter-satellite radio links in the fully connected pLEO constellation for the transfer of clock estimates from the clock ensemble Kalman filter residing onboard the anchor platform, j to all other participating platforms in the constellation is a major concern. In this research, the effect of reducing the number of data packet exchanges, between the remote sensor, called the clock ensemble Kalman filter running onboard the anchor platform, j and the steering controller or actuator associated with the local IEM realization onboard platform i.

In essence, the knowledge of the local IEM realization onboard platform,

i is used at its steering controller or actuator side to approximate the behavior of the OCXO relative to the IEM during time periods when clock estimates from the remote sensor, i.e., clock ensemble Kalman filter running on platform

j are not available. The main idea is to perform the feedback by updating the state,

of the local IEM realization model governed by (

66) using the actual state

of the ensemble clock,

i that is provided by the remote sensor, i.e., the clock ensemble Kalman filter running onboard the anchor platform,

j is given by

which in accordance of (

63), leads to

As for the rest of the control interval, the steering action is based on the local IEM realization model. The dynamics of the local IEM realization model are then incorporated in the steering controller or actuator and thus, is running open loop for a period of h seconds.

Interestingly enough, the research investigation herein presents an initial step toward onboard timing architectures in AltPNT. The analysis contains the tradeoff between open-loop and closed-loop steering controls that would support local pLEOT formation across a pLEO constellation, thus, providing potential resilient navigation services. Subsequently, networked control systems are proving to be a very valuable tool for designing control systems for steering frequency standards with minimal attention and network resources.

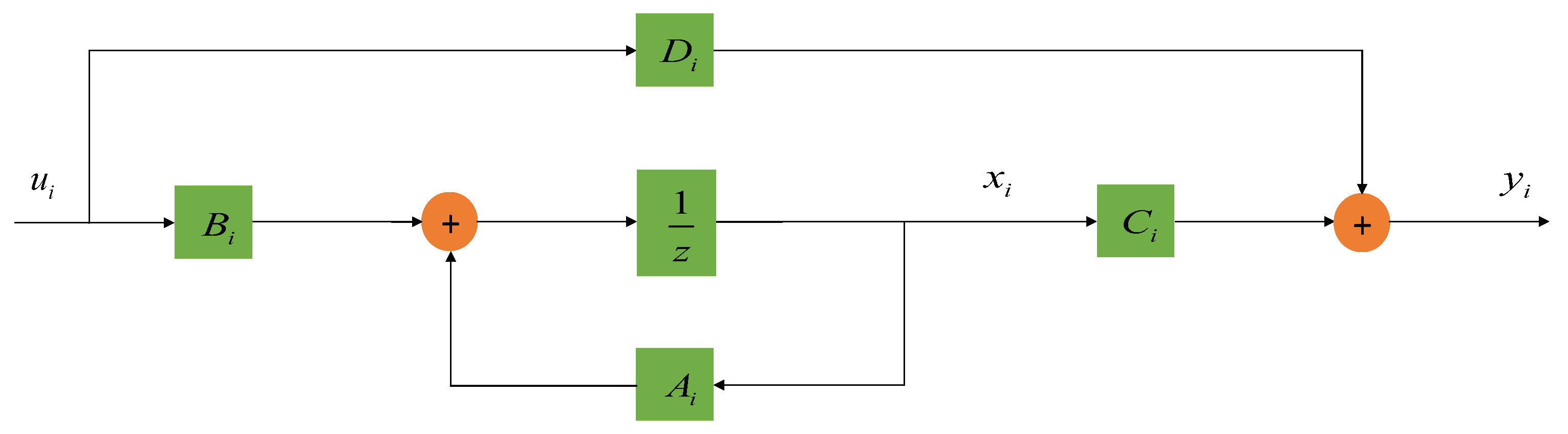

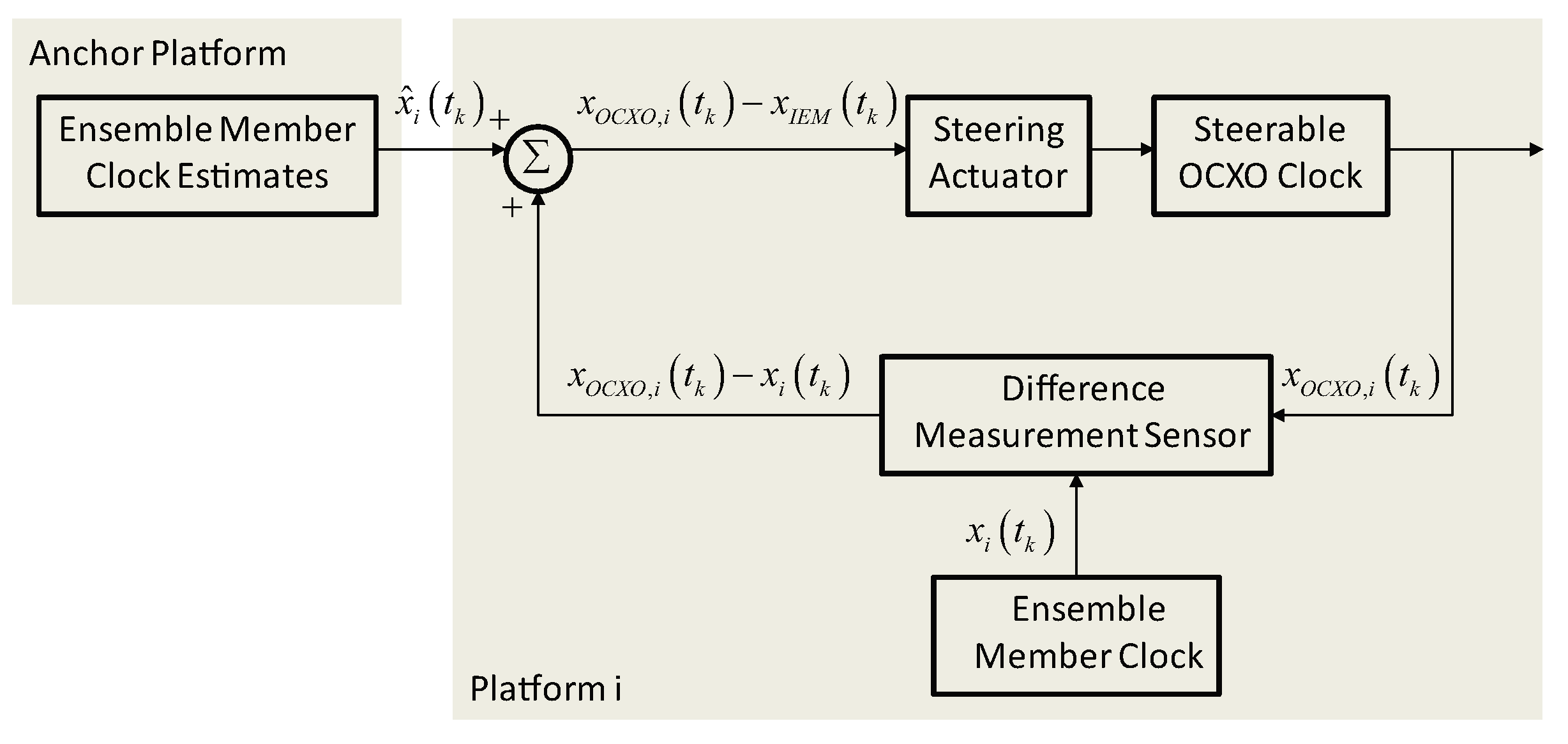

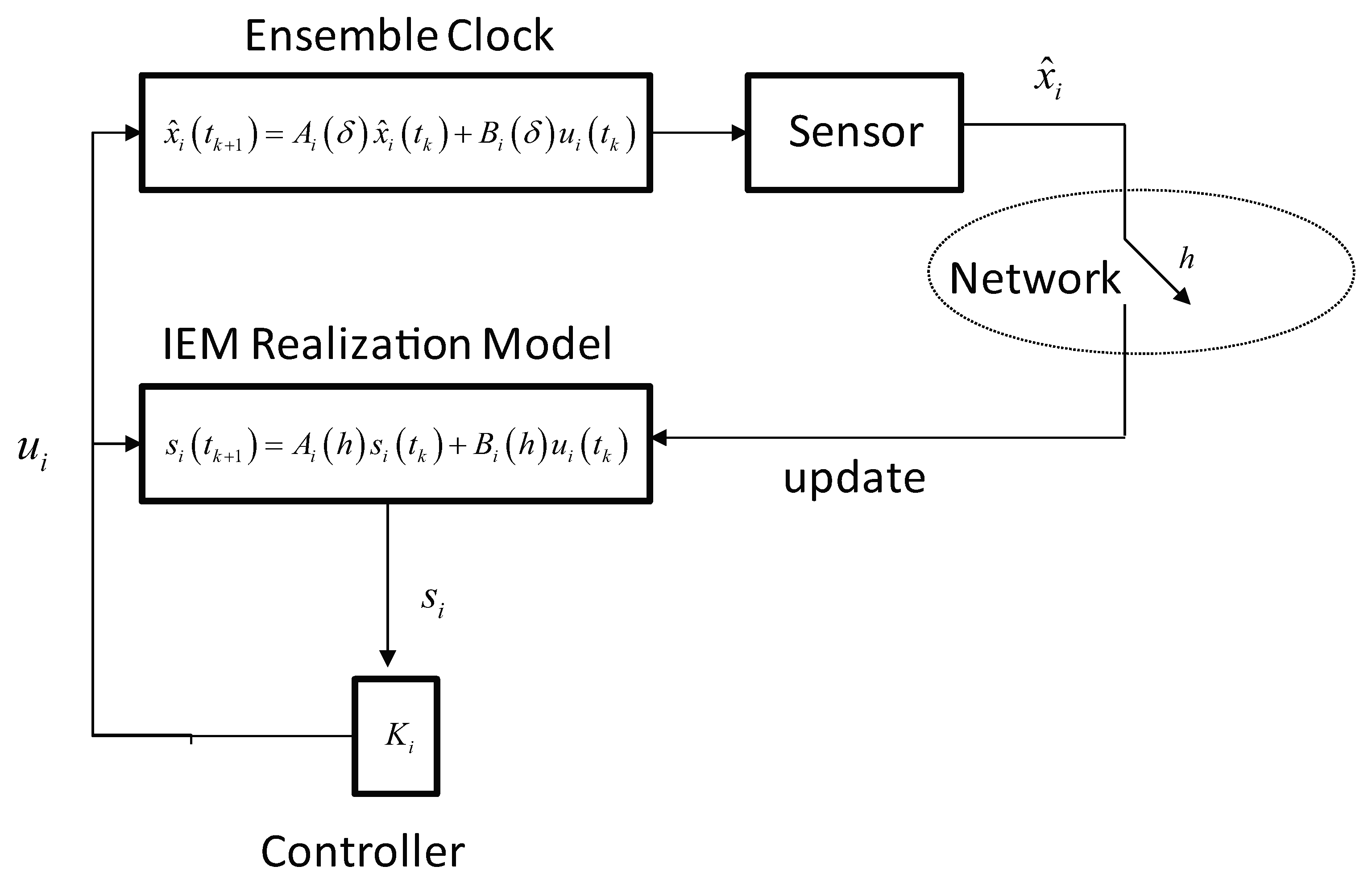

Consider a feedback networked control system of

Figure 10, where the actual IEM estimate behavior is described by

where

and the update time

with

for all

k.

Also, the local IEM realization model is given by

Clearly, as shown in

Figure 10, the remote sensor onboard platform

j has the full state,

available. It will send the state information through the inter-satellite radio links every

h seconds.

Finally, the onboard controller,

for clock steering by

where one further observes that the gain matrix,

affects how quickly the signal transitions from the free-running behavior of the local OCXO clock to the IEM estimate.

The state error,

is defined as

The analysis that follows, was motivated by the work [

19]. For each

i and

, the state error,

represents the difference between the OCXO state and the IEM. The modeling error matrices

and

denote the difference between the actual ensemble member clock and its remote IEM realization model.

Of note, the local IEM realization model

i is updated every

h seconds, i.e.,

for

, this resetting of the state error every update time is key of networked control platforms herein. It can be shown that the dynamics of the local IEM realization system,

i for

can be described by

where

Moreover, the discrete state-feedback system (

73) is globally exponentially stable around the solution

if and only if the eigenvalues of

are inside the unit circle. Herein, the most essential implication of the result (

74) and (

75) is the necessary and sufficient condition for stability of (

73). This result refers to the maximum transfer time or the smallest frequency at which the network and the anchor platform must update the state in the remote steering controller,

i associated with the separate platform

i and

under consideration. That is, an upper bound for

h, called the update time for its local reference timescale, pLEOT

i steered to the global IEM timescale running onboard platform

j.

6. Onboard Steering Commands via Miminal-Cost-Variance Control

Given the outlook of all pLEO platforms attempting to generate their local IEM realizations for pLEOT, each platform will steer its own local reference clock, for example, an autonomous robust timescale as realized by the versus the IEM estimation. In addition to the controller update rate, h as mentioned previously, there is another tuning parameter, called the controller gain, used for steering the correspondent OCXO signal response to the IEM estimate. Generally speaking, a larger gain is expected to yield larger frequency corrections for any given offsets of the OCXO from the IEM estimate, thus, resulting in a more accurate realization of the IEM. To this end, the elements of controller gain, that determine the responsiveness of the autonomous remote timescale system running onboard platform i are designed via the Minimal-Cost-Variance (MCV) control theory.

Recall that the discrete-time state-space counterpart of a local IEM realization model (

70) that is completely controllable, is governed by

where the states of the steering control system (

76) consist of the phase and frequency of the steered OCXO clock onboard platform

i. The steering commands,

, which are fed to the actuator, such as a MPS. The available output signals or measurements are typically the phase deviation,

between the local OCXO oscillator and the IEM estimation. The controller,

operates on the actuator to minimize, for example, the phase deviation,

. Noise parameters associated with both OCXO and IEM clocks are determined according to measured Allan deviation curves. The realization of these noises is represented by the zero-mean Gaussian process noise,

its covariance matrix given by

.

Moreover, one of several requirements can be set on the clock steering onboard each platform versus the IEM estimation, for instance, the image of the performance indicator is suggestive, evoking a convex cost function for selecting a steering policy, a quadratic cost function supported by a belief that the relative penalties assessed to the phase and frequency deviations and steering efforts pertaining to a local reference clock,

i can be optimized for all time

k in a finite horizon,

. To be credible, such penalties have to be responsive to the clock steering operations attempting to drive the phase and frequency deviations toward zero; e.g.,

where the weighting coefficients associated with the steering efforts,

and the phase and frequency deviations,

are positive and bounded. In general, if

is large compared to

, the penalty is large for the controller and/or actuator attempting to drive both phase and frequency deviations toward zero to rapidly. On the other hand, if

is large compared to

, the controller faces a small penalty for a large steering effort and the system is driven toward zero more quickly.

A further concern now involves clock steering operations in attempting to meet request performance specifications for precision and reliability of local reference timescales onboard separate platforms. One of stringent time metrological requirements may be chosen by the designer therefore to steer only once, rather than to repeatedly perform the same operation [

20]. Accepting this mandate immediately suggests the consideration of MCV control paradigm to be the most natural steering technique for clock and timescale adjustments, in which the variance of the performance measure (

2) is minimized while the expected value of the performance measure is constrained prior.

As an aide to the reader, this section should be seen as an important signpost representing the theory of MCV control. It is the foundation for determining ways to design new steering control laws that could meet design objectives for autonomous, resilient, and remote timing systems by affecting the probability distribution of the performance measure for the realization of IEM estimates in desirable ways. In particular, the emphasis on minimizing the variance of

while its mean is forced to obey a constraint has a bearing on the current setting; e.g.,

is minimized, while

where

denotes the conditional expectation operator and the actual data

measured from local frequency standards onboard separate platforms with

and

.

The fundamental concern of

is with practical considerations, including desired response, permissible deviations from the desired response, complexity of the clock steering controller, etc. How to proceed, given this general assessment? It turns out the choice of

is not entirely arbitrary. It must be selected such that it is always greater than

At this moment, it may be shown that for the special class of linear-quadratic problem, the mean value constraint is intuitively given by

where

and

is a symmetric and nonnegative matrix. Moreover, both

and

should be selected such that

where

is as given by (

81).

Of note, a recursion equation for the optimal variance cost calls for the standard procedure for this type of problems; first, the constraint equation is appended to the expression to be minimized by means of a Lagrange multiplier,

, and then the resulting equation is embedded into the more general class of problems where

is a variable rather than a fixed initial time. Clearly, the solution of the more general problem leads trivially to the solution of the problem posed herein. Consequently, it is desired to find

and the clock steering policy be of the form

,

, such that

is minimized, where

is a Lagrange multiplier, and where the four pre-multiplying

has been introduced just for convenience. Note that

contains all the information available to clock and timescale adjustments at a time

k and the form chosen for

together with a boundedness requirement contributes to the definition of the class of admissible steering controls.

Before proceeding with the development of the recursion equation, however, let

,

, and let

where

signifies “variance cost.”

In order to prevent mathematical details from obscuring the concepts to be analyzed, some of the steps leading to the recursion equation for the variance cost has been relegated to [

20]. At this stage, the assumption of linear control laws leads naturally to optimal quadratic costs, that is, for linear control laws it is always possible to write,

where

and

are symmetric and nonnegative real-valued matrices and whereas

. Thus, for

, it follows

Aside from the relevance of

for

, to the terminal conditions given by

,

,

, and

, some mathematical manipulations further yield

Performing the minimization with respect to

for the

i-th clock steering, the optimal minimal-cost-variance controller

for clock and timescale adjustments are given by

where, for

and

Using the MCV controller (

89) for clock and timescale adjustments and performing the minimization in terms of

the mean constraint is obtained as follows

and the variance

where

and

.

At present, as has been evident all along, concerns about the control solution explaining the minimum nature of the expected value of a finite-time horizon quadratic cost as in the minimum mean cost control, have receded from the investigation of new clock steering methods herein. The focus is now on the minimum variance cost problem, whereupon for each selection of , , the solution of the recursion equations implies a mean value of the performance measure as well as its corresponding minimum variance and optimal control law. Securing such effective , is a principal goal of validating several such sets of expected values, minimum variances, and optimal steering laws. Putting this observation in its most contemporary assertion the claim is that the minimum mean problem is a particular case of the problem herein solved, namely, it is the solution of the recursion equations in the limit as approaches infinity, .

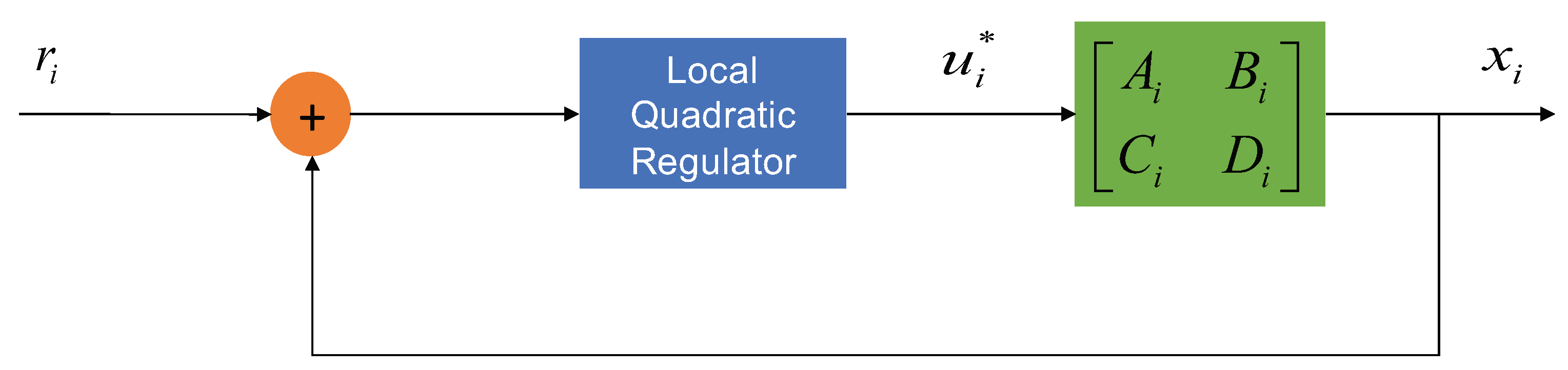

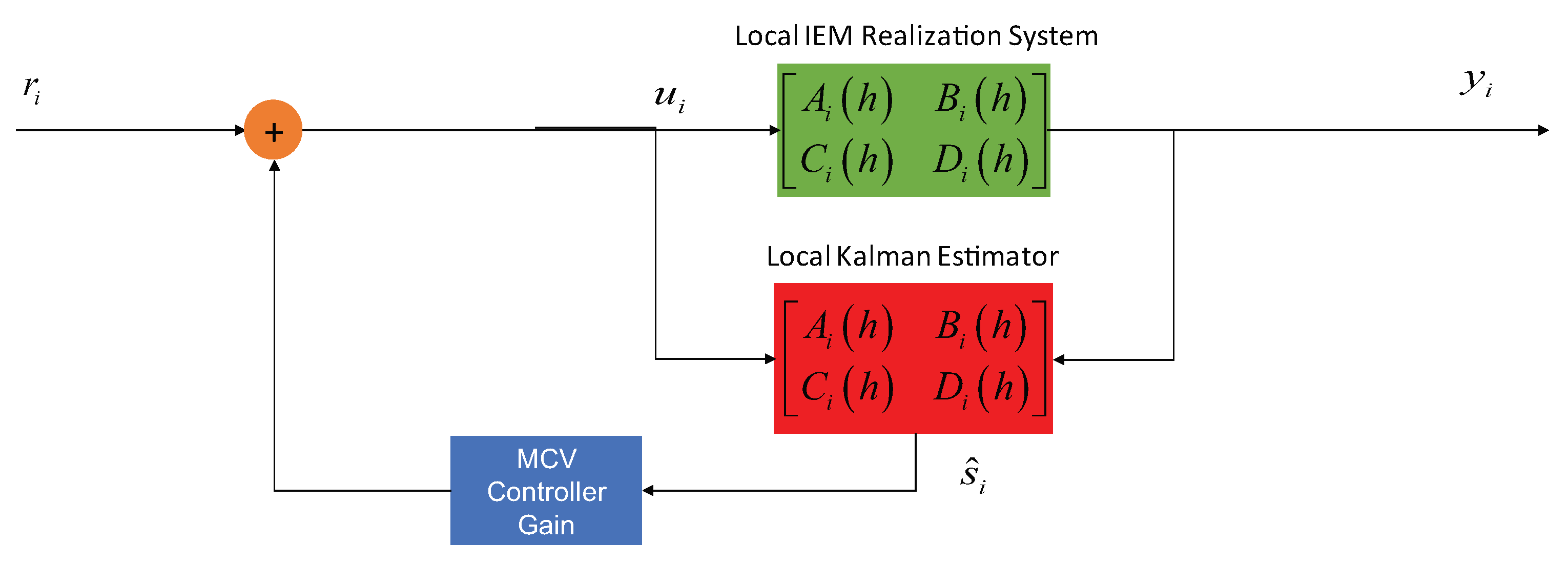

Under suitable conditions where both process and measurement noises are Gaussian, the design of stochastic control herein can be further extended and thus divided into two separate problems, one of optimal control with full state information and one of filtering. The remainder of the research investigation is to present a framework for the separation principle, which is more in line with basic engineering thinking, e.g., the optimal feedback law for steering commands is linear in the data feedback and given by

where

is obtained by a local Kalman state estimator. Each platform

i in

Figure 11 uses the steering command (

92) based on the Kalman state estimator for feedback frequency adjustments to ensure the phase offset between the steerable OCXO and the IEM estimate driven to zero.

7. Conclusions

The article has introduced the reader to an emergent timescale concept in AltPNT and some technical challenges in the new area of onboard ensemble timescale autonomy based primarily on inter-platform measurements. Admittedly, the preliminary findings herein have been an overly simplified presentation. Hopefully, they have generated heightened interest in the generation and realization of onboard ensemble timescales across pLEO constellations.

In particular, AltPNT is the key to enabling proliferated constellations intended to be reconstituted on a 3-5-year basis. It was shown that ensembling across pLEO constellations can be achieved by on-orbit assembly of flexible ensemble timescales, using the autonomous networked control of timescale realizations during and after the placement of critical information about the IEM estimation on inter-platform communication networks. The use of existing satellite crosslinks and tradeoffs between open-loop and closed-loop control manifests in the control interval and thus, becomes a dominant parameter of clock steering.

Moreover, it should be emphasized that a deep understanding of how to achieve high-precision time synchronization, resolving first-order Doppler effects on the frequency changes about received signals as a function of relative position and velocity between platforms, was investigated and is quite distinct from the existing literature on clock ensemble generation and realization. Resilient dissemination of precision timing from a distributed architecture was proposed with discreet communications between the anchor platform and separate platforms. The discreetness of IEM dissemination and data transport performance is not affected due to optimal power allocation between timing and data transports.

The autonomous assembly of active MCV controllers is the central element of steering one frequency standard very tightly to another, thus creating an onboard low SWaP timescale backup in phase and on frequency with the IEM reference. The robustness of the MCV algorithm allows reliable timescale realizations of the method even though the constituent noise processes are stochastic and performance measures are uncertain beyond the expected value.

Needless to say, the findings herein show promise in enabling some core capability concepts to achieve operational effectiveness and efficiency for ad-hoc and non-dedicated pLEOT over crosslink satellite communications under extreme radio conditions of GNSS outages, leveraging local autonomous agents running onboard pLEO constellations. These local agents provide the deep integration of communication and PNT services at the physical layer, by regulator policies derived from incumbent data link layers for link capacity resource forecasts.