1. Introduction

In the first quarter of the 21

st century, the global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has expanded more than three times compared to the early 2000s [

1]. Accompanied by the rapid development of the global economy, maritime transportation has become the backbone of international trade, performing around 80% of its volume and accounting for 50% of its value [

2]. Therefore, to keep up with the massive expansion of the global economy, the demand for increasingly efficient maritime transportation has intensified. However, those vessels will easily suffer from the difficulty of navigation and maneuverability, which may lead to serious consequences. For instance, the 2021 Suez Canal obstruction by poor maneuverability of the Ever Given vessel disrupted a humongous 10 billion dollars worth of goods and a loss of 14 million dollars per day for the Egyptian Government [

3,

4]. Hence, the need for advanced technology to position and maneuver marine vessels in various situations such as docking and undocking large ships, or maneuvering offshore platforms through narrow passages, such are shown in

Figure 1.

To enhance the maneuverability of marine vessels, tugboats play a crucial role in providing pushing and pulling assisting forces [

5]. Proper coordination of multiple tugboats simplifies complex operations, improves safety, and has become increasingly important with the growing demand for offshore energy development and expanding maritime trade. Traditionally, the operation of tugboats depends on manual control, requiring skilled pilots to precisely manage the pull/push force, heading angle, or direction [

6]. Hence, coordinating multiple tugboats in complex maneuvers demands harmonious communication among operators, which is labor-intensive and poses inherent risks. However, recent improvements in autonomous tugboat technology have accelerated commercial interest [

5,

7,

8]. This shift paves the way for fully automated offshore platform transportation, offering an improvement in efficiency, safety, and minimizing human involvement.

Nevertheless, the tugboat configurations, system uncertainties, environmental disturbances, and especially, control strategies still require continuous evaluation and enhancement. For instance, existing studies often focus on specific systems with predetermined number of tugboats and configuration, leading to case-specific models and control designs that limit operational flexibility. In this study, we introduce a new approach to modeling and control system design for tugboat-assisted operations, such as docking and rescuing marine vessels. The mathematical model of a general tugboat-assisted system is first derived and then modified with a new variable vector that is beneficial for subsequent control system design. Then, a centralized control system is designed, employing the state feedback synthesis to solve the mixed control performance problem. A case study is conducted to validate the control solution.

Then, the contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

A mathematical model of a general tugboat-assisted system, applicable to any specific tugboat-assisted configuration.

A modified model incorporating new variable vectors that linearly couple the dynamics of the transported vessel and tugboats and thus, benefit for control system design process.

A centralized control scheme and control law design method for tugboat-assisted systems, based on mixed control performance, utilizing state feedback, and linear matrix inequality techniques.

Case studies validating the proposed control solution.

2. Related Studies

To develop an effective tugboat-assisted system, the tugboat configuration, and subsequently, the dynamics of the entire system need to be investigated. In [

9], a single tugboat configuration with the strategy of leader-follower is proposed and investigated. Another platform introduced in [

10,

11,

12] allows the passive vessel without rudders to be assisted by two tugboats; one in the front and the other in the back. In [

13,

14], two tugs are positioned ahead of the towed vessel. The study [

15] offers a configuration of two tow-tug placed in the front and one pushing tug on the side, hence, eliminating the yawing moment of the passive vessel. However, even with these configurations, the system dynamics remain nonholonomic.

Consequently, four-tug arrangements are commonly employed in practical applications such as [

16,

17,

18], while research [

19,

20,

21] explores six-tug combinations allowing the system to provide propulsion from multiple directions, thereby enhancing maneuverability in complex operating conditions. Nevertheless, this setup requires significant space, making it difficult to apply in narrowed or highly complex operational areas. Hence, the studies [

22,

23,

24] introduced a configuration featuring two pushing tugs and two towing tugs, all positioned on one side of the platform to optimize space occupation. By balancing opposing push/pull forces, the system maintains maneuverability comparable to traditional configurations. Additionally, [

12,

13] derived a model for the tugboat cable force and analyzed its influence on the motion of the towing tug. Unfortunately, the variation in tugboat configurations requires specific control solutions for each case, making a universal solution highly desirable.

Additionally, uncertainties and disturbances must be considered when developing a control system for stable tugboat-assisted operations. In [

21], sliding mode control system for a 3-DoF horizontal model is applied with the optimization of thrust forces and tug force directions, and the number of tugboats is arbitrary. The optimal-based allocation is again utilized in [

20], in which the adaptive control and Lyapunov-based approach is applied to ensure the stability of the fixed 6-tug system . Model predictive control is proposed in [

17], focusing on position error, heading error and velocities. In [

26], the model predictive control focuses on trajectory tracking and fuel consumption optimization; and in [

27], integrated with optimal-based and event-triggered mechanisms to ensure the stability and robustness of the system. However, in these studies, the disturbances are usually omitted, and the tugboats are a maximum of two tugs. Consensus-based [

28] offered wireless motion synchronization and load position correction produced promising results, especially in low-speed maneuvering and positioning operations mostly without the interference of disturbances. The combination of optimal-based, dynamic surface control and robust control in [

18] also provide good reference trajectory with high accuracy.

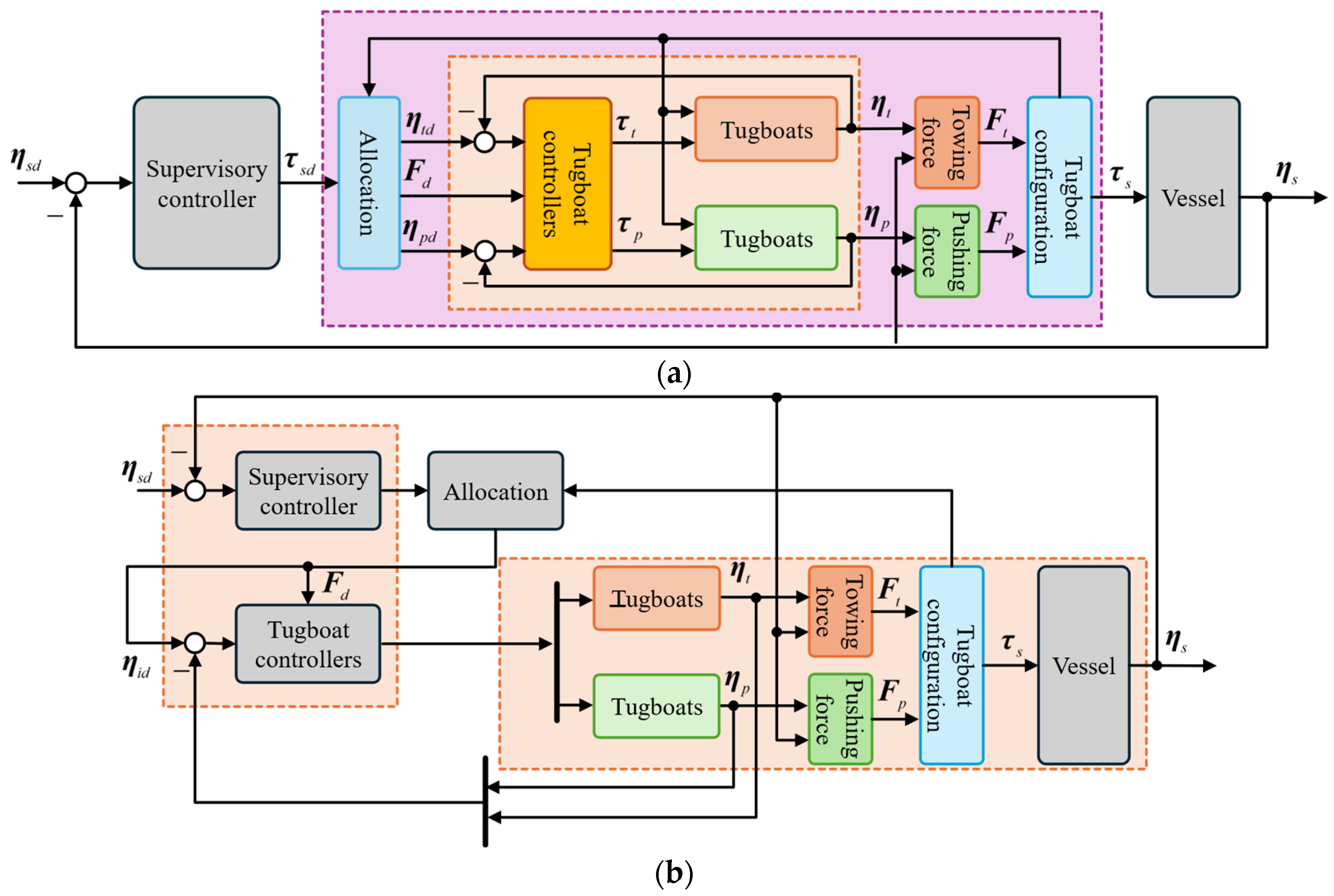

Mentioned above are decentralized control systems [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

26,

27,

28]. Although they have the benefits of flexibility, integrating different control techniques that correspond to each vessel’s unique dynamics, but suffer from the reliance on a cascade control structure, which primarily ensures input-to-state stability at best. In [

22], an approach of centralized

control, in which the platform control inputs are obtained by the control allocation based on pseudo-inverse method, is proposed. Simulation results confirmed the effectiveness of the proposed control system, but this allocation method can lead to unstable outputs, and the study's system model limitations prevented the definition of motion references for the tugs, hindering the validation of the control approach's feasibility. [

25] addressed these challenges by treating the allocation design as a constrained optimization problem and developing a robust control strategy. The results show the control allocation still affects significantly control performance.

3. System Modeling

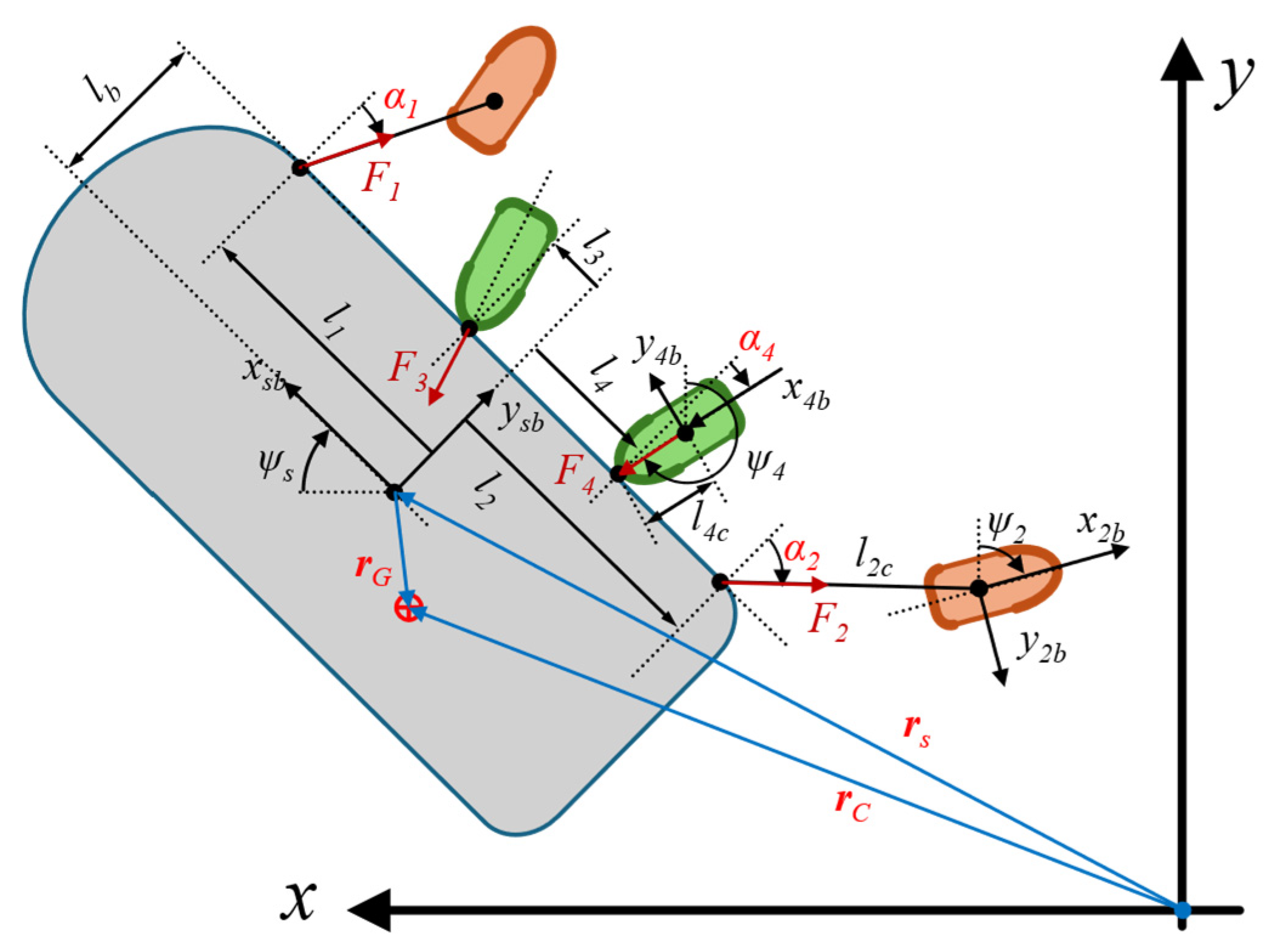

The vessel being transported lacks both propulsion and actuators to regulate its movement, requiring external assistance for maneuvering. We consider a general configuration of (

m + n) tugboats assisting the vessel’s motion (

m,

n ≥ 0).

m tugboats provide towing forces to the vessel via towing lines connecting to fixed connection points on the vessel. The

n other tugboats push the vessel by their nose on the vessel’s hull.

Figure 2 depicts an example system consisting of two towing tugboats and two other pushing boats and they are on one side of the transported vessel. The side is either at the front, for route-following tasks, or on the outer side, during berthing operations, of the vessel. The motions are described in the standard geographic reference frame and the body-fixed frames, as also elaborated in

Figure 2. In particular, the origin of each body-fixed coordinate system is located at the geometric center of the corresponding marine vehicle.

The relative positions between the vessel and the tugboats are derived from :

li : the longitudinal distance from the coordinate origin of the vessel-fixed frame to the connection point on the vessel of the towing line connected to the ith tugboat.

lib : the lateral distance from the coordinate origin of the vessel-fixed frame to the connection point on the vessel of the towing line connected to the ith tugboat.

lic : the length of the towing line, from the ith connection point connected to the ith tugboat, assumed that the end-connection point is at the coordinate origin of the tugboats.

αi : the relative angle between the towing force from the ith tugboat and the lateral axis of the vessel. It is equal to the relative angle between the towing line connected to the ith tugboat and the lateral axis of the vessel if the line is in tension.

lj : the longitudinal distance from the coordinate origin of the vessel-fixed frame to the point of application of impact force from the jth tugboat.

ljb : the lateral distance from the coordinate origin of the vessel-fixed frame to the point of application of impact force from the jth tugboat.

ljc : the longitudinal distance from the coordinate origin of the jth tugboat-fixed frame to its nose, i.e., the point of application of impact force from the tugboat.

αj : the relative angle between the pushing force from the jth tugboat and the vessel’s lateral axis. Generally, the pushing resultant consists of a normal force and a tangent friction force between the tugboat’s nose and the vessel’s hull. Without slippage between the two surfaces, the pushing force is in line with the longitudinal axis of the tugboat.

Furthermore, the assisting forces generated by the ith towing tugboat and the jth pushing tugboat are denoted by Fi and Fj, respectively. Additionally, vector depicts the deviation of the vessel’s mass center from its geometry center, which results in two corresponding position vectors and .

Then, the motion equations of the transported vessel are written as follows:

where

is the vector of position and heading angle of the vessel in the reference frame, and

contains the surge, sway and yaw velocities. The kinematic relationship between frames is provided by the rotation matrix

given by:

where

and

for simplification.

represents the vessel’s mass and inertia,

is the Coriolis and centripetal matrix, and

is the total damping matrix. Particularly,

and

, with the former elements parameterized from the vessel’s rigid body and the latter elements being the added mass due to the inertia of the surrounding water. They are written as follows:

In which, the rigid-body mass is

ms, the moment of inertia about the vertical axis of the vessel-fixed frame is

Iz, and the vessel’s center of gravity is at

. The notation SNAME [

29] is used for the remaining hydrodynamic added mass forces in the above matrices.

Finally, the vector of actuating forces and moment is , corresponding to the surge force, sway force, and yaw moment, respectively. In the case of the tugboat-assisting system, , with F being the vector of assisting forces from the tugboats and being the configuration matrix of these forces acting on the vessel. One can see that the elements of depend on the relative angles, represented by the relative angles vector , and the distance from the origin of the vessel-fixed frame to the connection points/ points of applications, i.e., l. Finally, are those of environmental disturbances.

The dynamics of the

ith towing tugboats (

i = 1 ~ m), can be derived in a similar manner and result in:

Especially, the term

is the reaction of the tugboat assisting force with the magnitude

. Based on the geometrical relationship among the ships,

is derived as follows:

For each

ith towing tugboat, we consider

being the connection point to the towing line and it is fixed in the vessel-fixed frame. Let

is the distance between the point

to the coordinate origin

of the

tugboat.

means that the

ith towing line is in tensioned, i.e.,

and vice versa, if

,

(the towing lines are considered as weightless). The geometry constraints between the points are as follows:

On the other hand, for the

jth pushing tugboat in the system:

is the point of application of the

jth pushing force. In this case,

depends on the relative position of the vessel and the pushing tugboat. The vessel and the

jth pushing tugboat are in contact if the distance between

and

,

, meaning that

. Thus, if

,

. Additionally, the model of interaction forces, i.e., towing forces and pushing forces between the vessel and the tugs, have been thoroughly derived, for example, [

30]. Therefore, they are adopted for this paper.

5. Case Studies

The proposed control strategy is validated with the tugboat configuration given in

Figure 2. The case study consists of two tugboats towing an oil tanker via towing lines while two others push it in the opposite direction. All tugboats are positioned on the outer side of the tanker, towing tugs are outside, and two pushing tugs are inside, and perform a docking operation. This arrangement allows for sufficient maneuverability by adjusting the amplitude and angle of impact of the towing and pushing forces. The safe and effective movement of the tanker is achieved through the control of the corresponding tugboats. From

Figure 2, one can write the configuration matrix of the tugboats, and subsequently, the actuating forces and moment acting on the assisted tanker, as follows:

The specifications of the tanker are adopted from the well-known ESSO 190000 dwt tanker from [

32]. The tugboats are referred to [

30] and [

33], which is based on a realistic tugboat model with Azimuthal Stern Drive (Z-Drive) propulsion system. These references present full-scale and model-scale tugboats whose hydrodynamic behavior and interaction characteristics have been extensively validated through numerical and experimental studies. The primary parameters adopted in our simulation are summarized in

Table 1.

The detailed hydrodynamic derivatives are listed in [

32], [

30] and [

33]. The model of the entire system is obtained following the procedure introduced in previous sections. Additionally, to take into account the model uncertainties and environmental disturbances, we consider that the center of the gravity of the tanker does not coincide with its coordinate origin. Hence,

xG and

yG are the uncertain parameters in the tanker’s mass and inertia matrix.

The optimal state-feedback is obtained for this uncertain system by minimizing , where is the RMS gain of the transfer function from to given in Equation (22), and is the H2 norm of the transfer function from to . is chosen for the trade-off between the two criteria. The linear matrix inequality technique is used for the state-feedback synthesis problem with uncertainties.

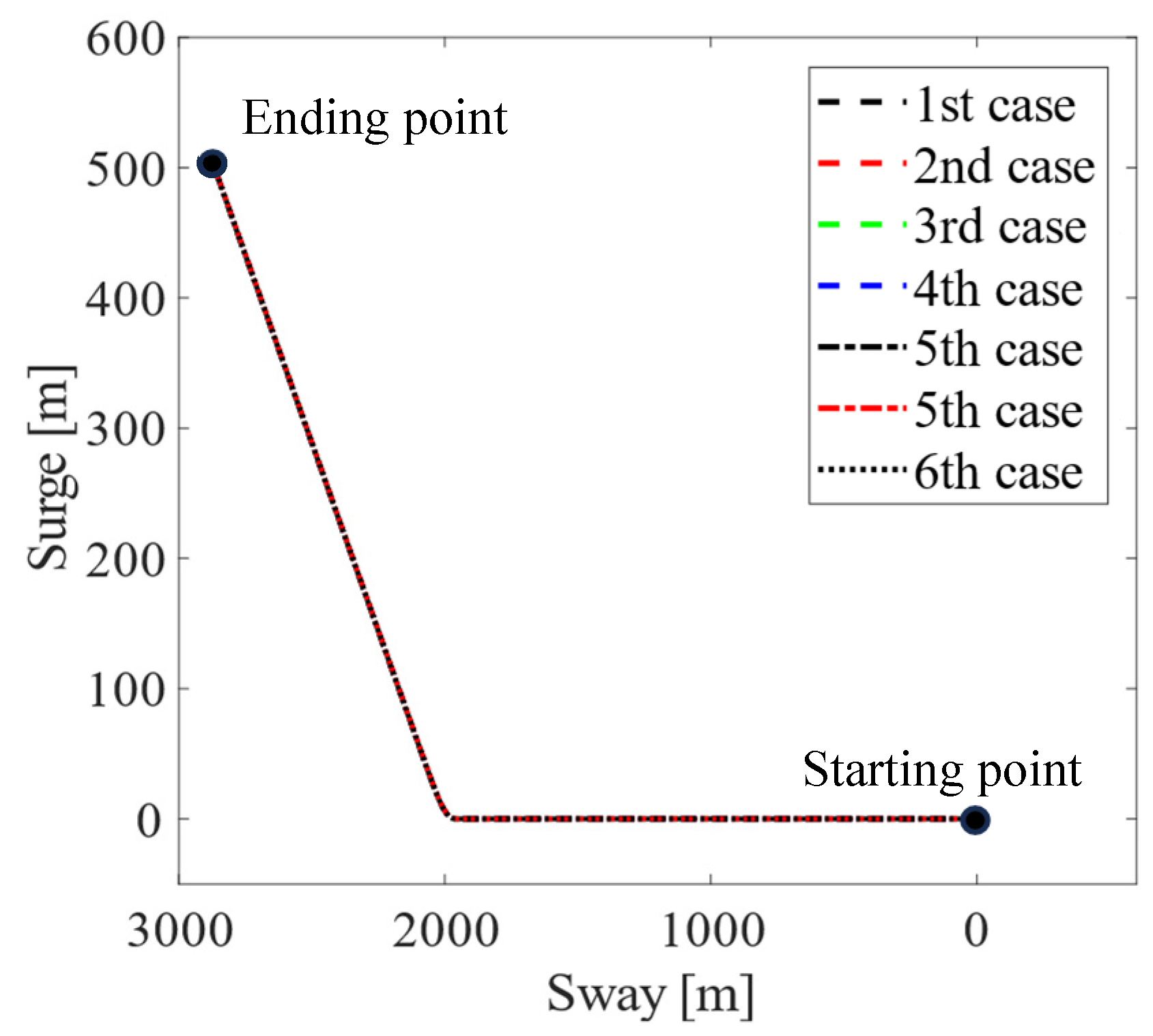

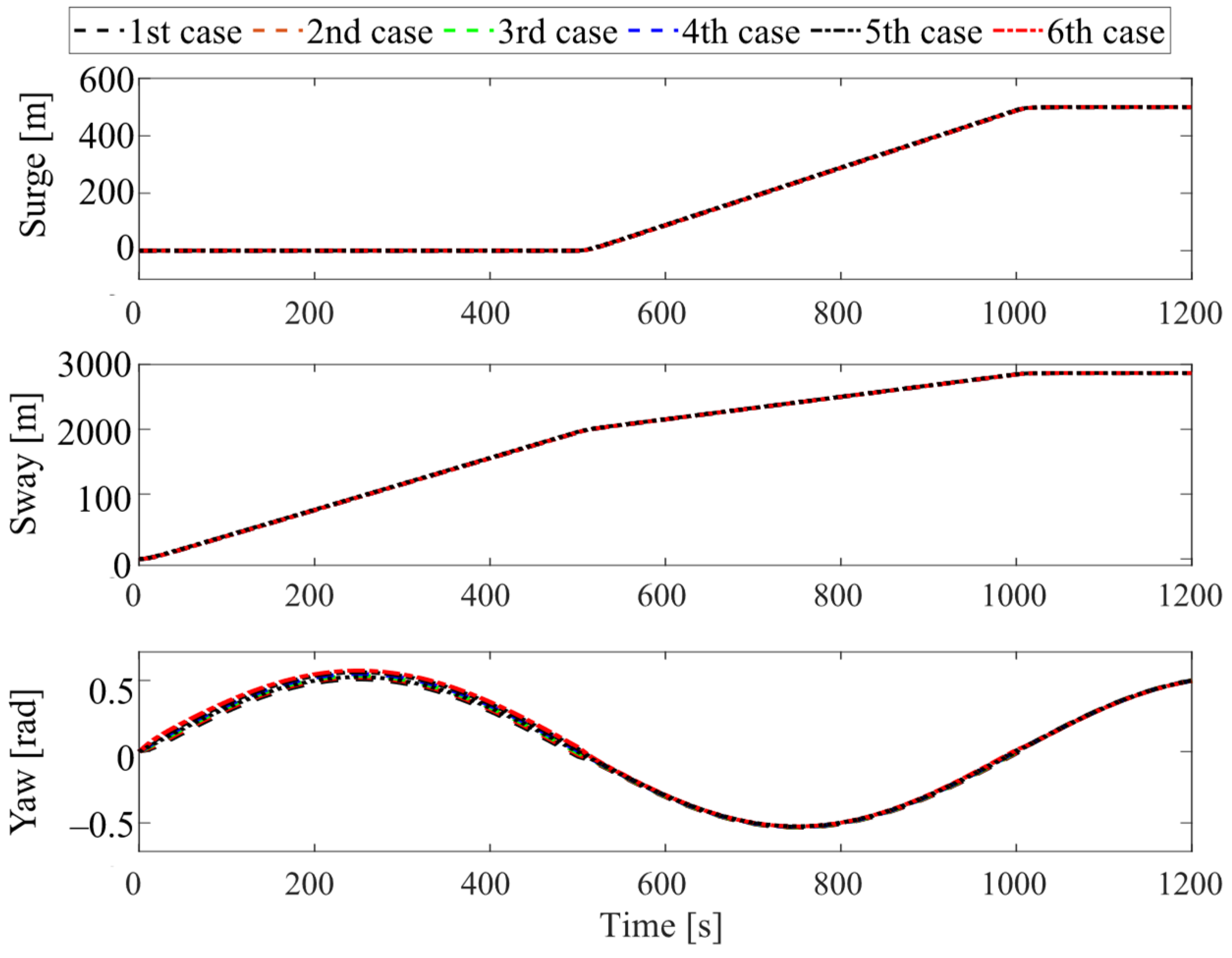

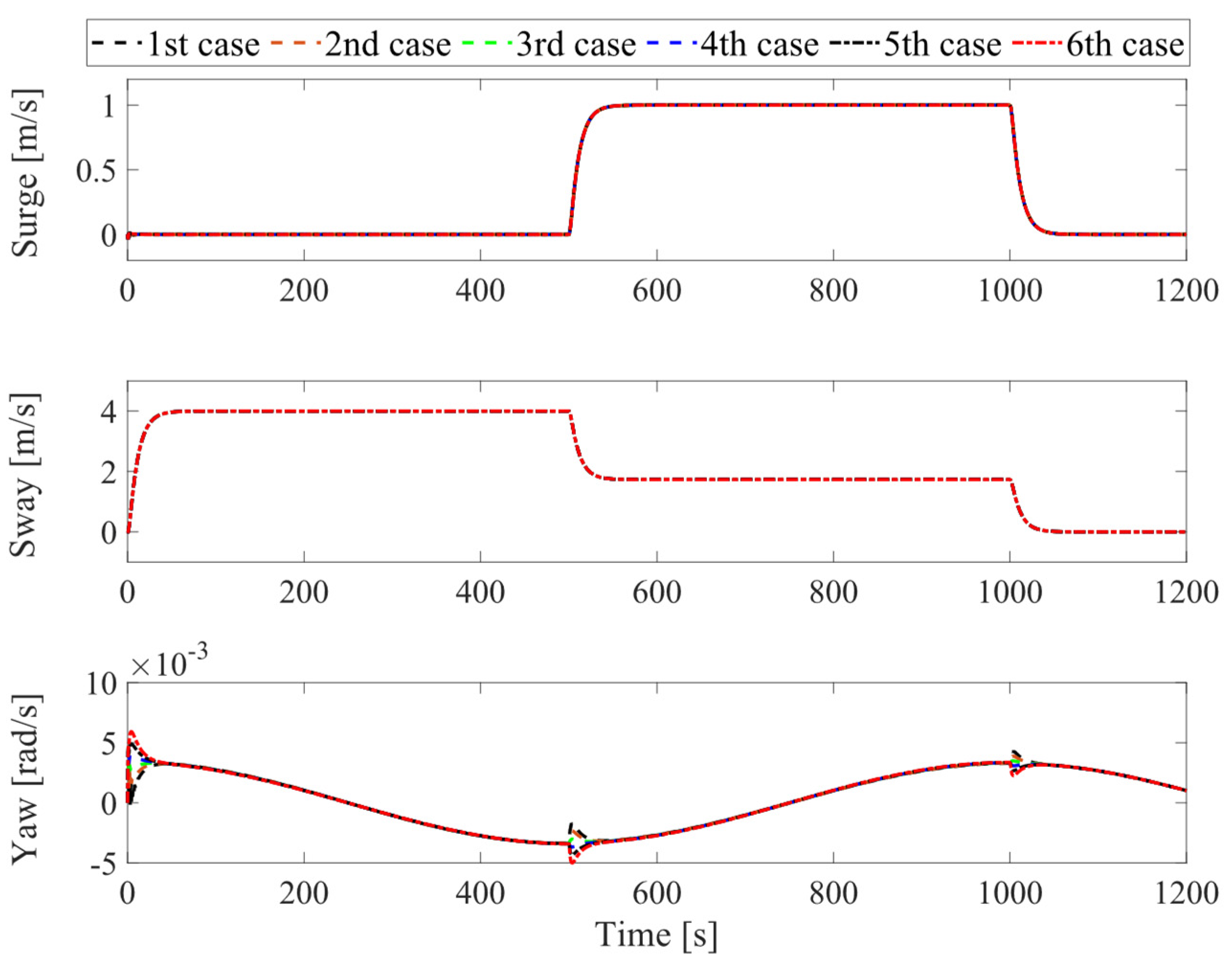

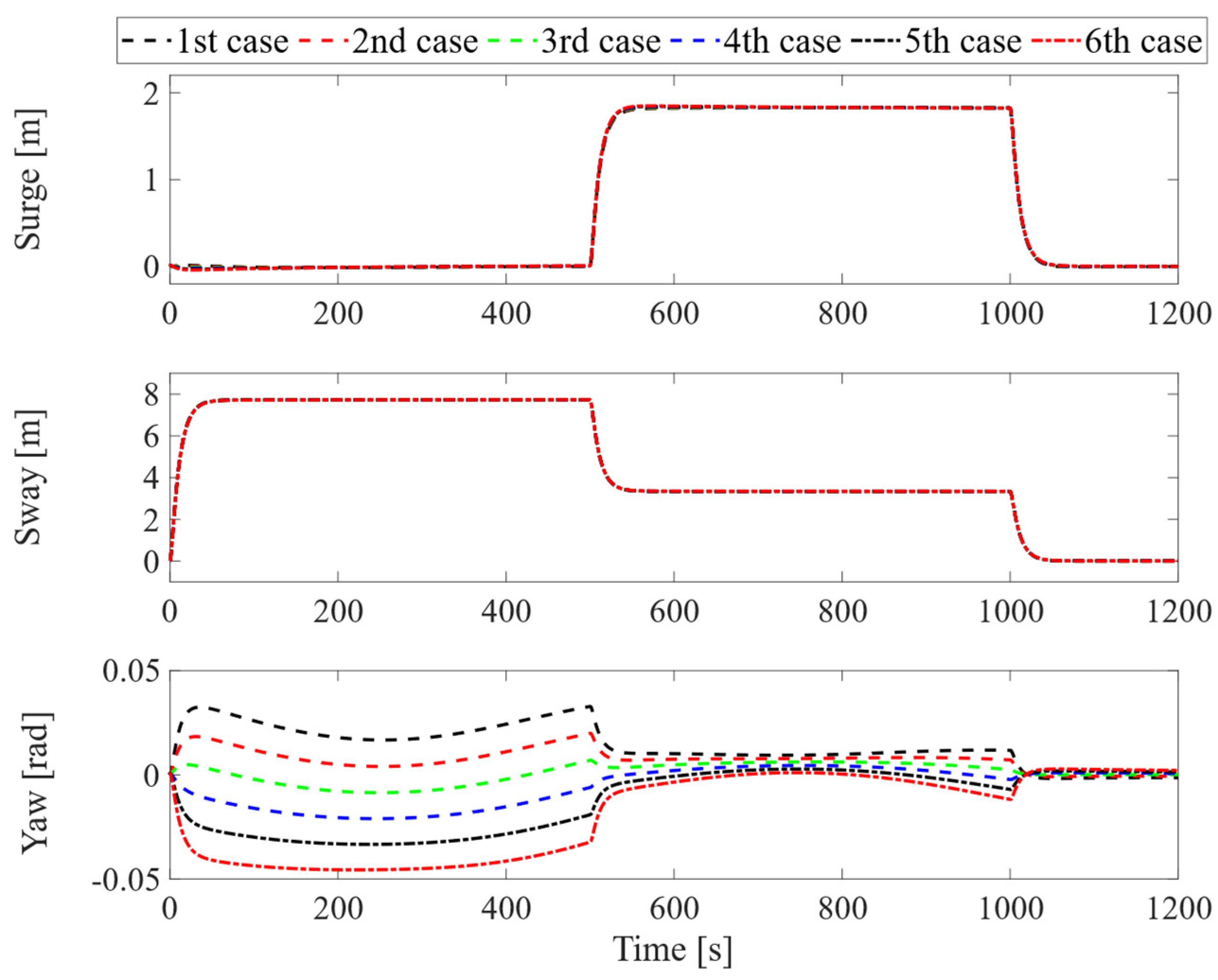

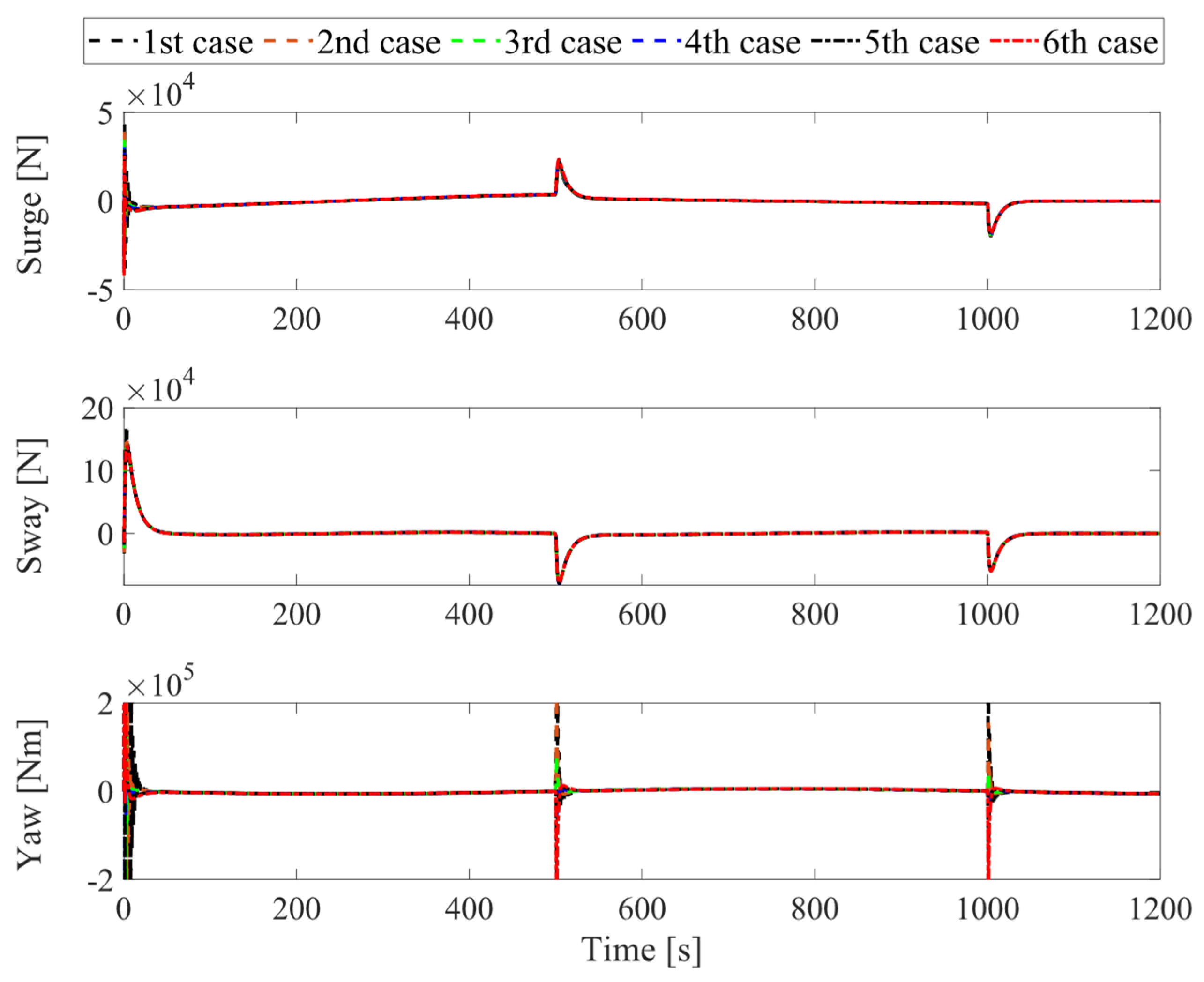

A docking scenario is considered for this case study. The tanker moves from its original position (initial surge, sway, and yaw positions are zero) to follow the desired docking trajectory within 1200 [s]. The responses of the assisted tanker are presented in the following figures Figures 4~8. In particular,

Figure 4 shows the two-dimensional horizontal motions of the vessel observed from the top-down view. The controlled translational position and yaw angle responses are indicated in

Figure 5, while its rate of change is depicted in

Figure 6. Moreover, the black dotted line represents the desired reference. In addition, the tracking errors are illustrated in

Figure 7. Finally,

Figure 8 shows the control effort acting on the head to guide the vessel following the desired reference. For the sake of clarity, the remaining lines of these figures follow the convention: the black dashed line, the red dashed line, the green dashed line, the blue dashed line, the black dashed-dotted line, and the red dashed-dotted line correspond to 6 pairs (

xG,

yG) values, increasing from the smallest value (

,

) to the largest value (

,

), and evenly distributed into 6 pairs. In the remaining figures, we refer to these 6 pairs in order, with the smallest value corresponding to 1

st case, and the largest value corresponding to 6

th case.

In conclusion, as observed from the motion control responses in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, the proposed control system demonstrates good stability and tracking performance, even in the presence of the tanker’s uncertainties. Particularly, in

Figure 7, at the stage around 500

th [s] and 1000

th [s], the tracking error of the controlled yaw angle has a tendency to deviate from the desired tracking route, as the results from the change of

x-,

y-directions of the vessel during the tracking period. However, the tracking errors of all vessel’s motions always remain overall at a very small value. In

Figure 8, except for the departure stage, where the vessel requires sufficiently large forces and torques to transition from the steady state, the overall effort during operations remains consistently low. Hence, one can conclude that the proposed control system can achieve robust motion control performance, implying ensured fast and safe operation in further practical implementations.