Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

02 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. PRISMA Flow Diagram and Quality Assessment

3. Ecological Values of Freshwater Mussels

3.1. Water Filtration and Quality Improvement

3.2. Bio-Indicator of Environment

3.3. Bioaccumulation of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCP)

3.4. Bio-Absorption of Metals

3.5. Nutrient Cycling and Energy Transfer

3.6. Habitat Structuring and Biodiversity Enhancement

4. Economic Values of Freshwater Mussels

4.1. Mussel Flesh as Food and Its Bioactivities

4.2. Shell Powder and Its Derivatives

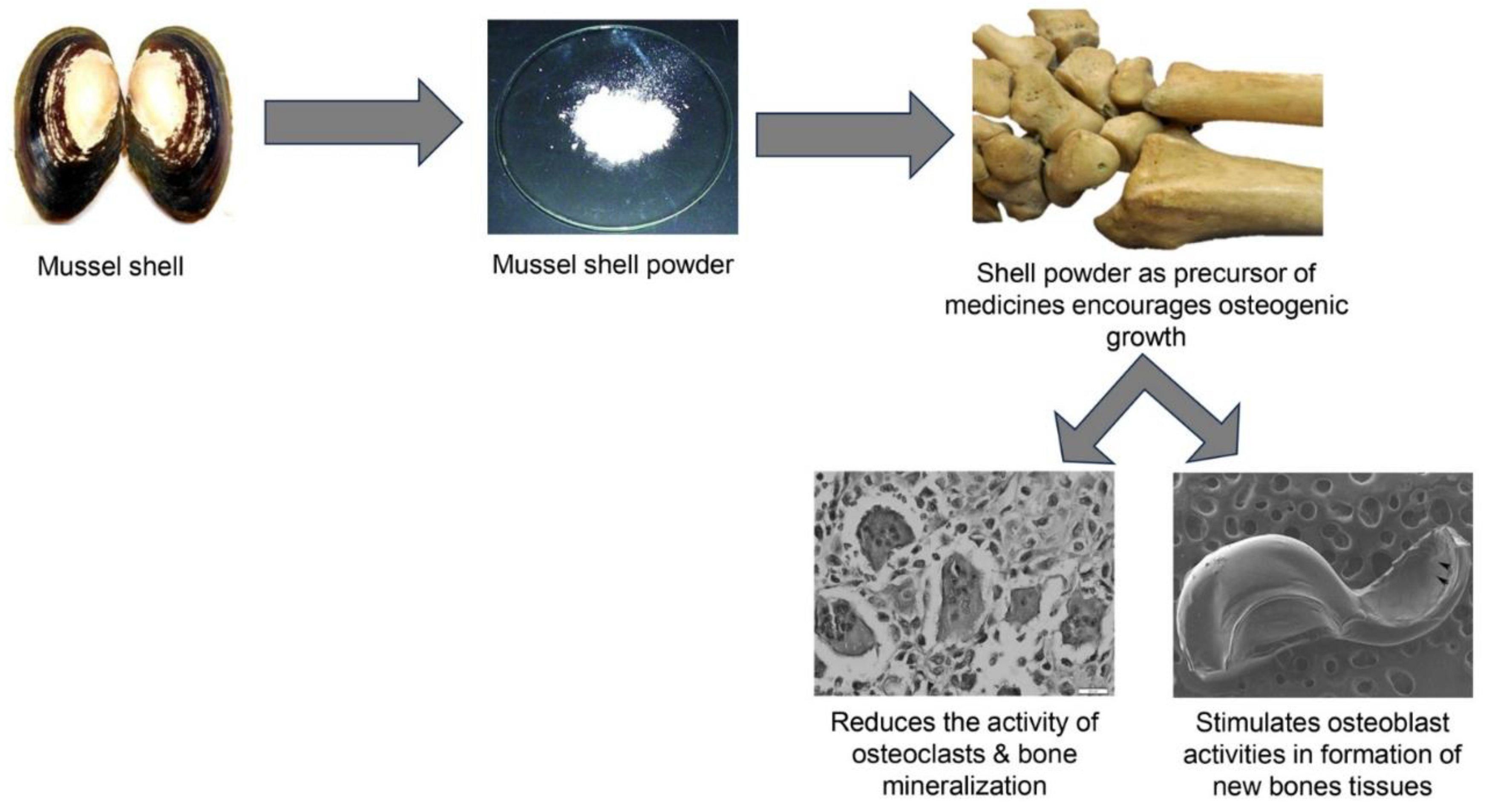

4.3. Pearl and Jewelry Industry

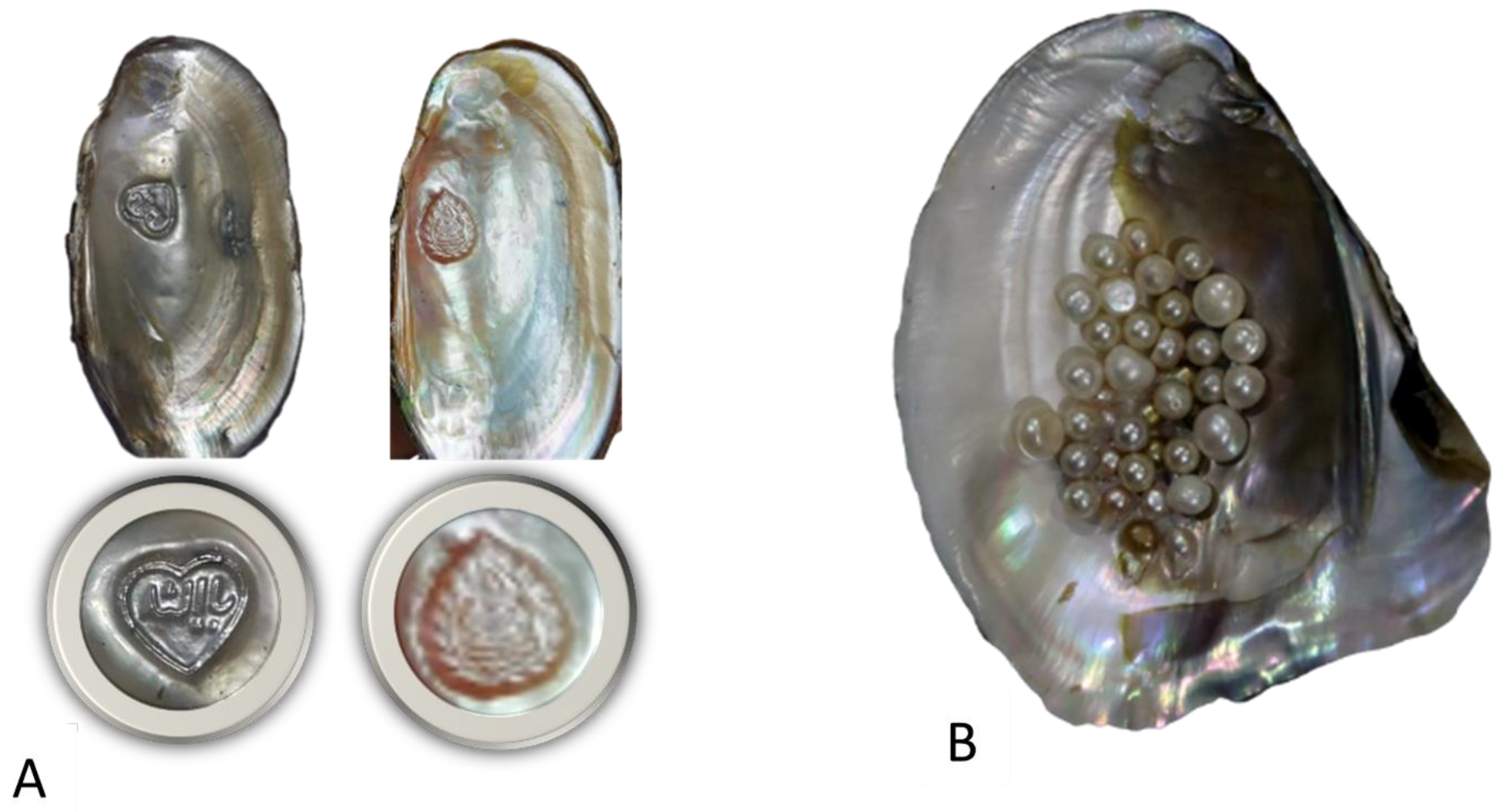

4.4. Environmental Monitoring and Socioeconomic Benefits

5. Threats to Freshwater Mussel Populations and Conservation Strategies

5.1. Habitat Destruction and Pollution

5.2. Overexploitation and Invasive Species

5.3. Habitat Protection and Restoration

5.4. Research, Monitoring and Stakeholder Engagement

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldridge, D. C., Fayle, T. M., & Jackson, N. (2007). Freshwater mussel abundance predicts the behaviour of mobile interstitial invertebrates in a soft sediment environment. Oecologia, 151(1), 115-124.

- Allen, D. C., & Vaughn, C. C. (2010). Complex hydraulic and substrate variables limit freshwater mussel species richness and abundance. Journal of the North American Benthological Society, 29(2), 383–394. [CrossRef]

- Allen, D. C., Vaughn, C. C., Kelly, J. F., Cooper, J. T., & Engel, M. H. (2012). Bottom-up biodiversity effects increase resource subsidy flux between ecosystems. Ecology, 93(10), 2165–2174. [CrossRef]

- Almeshal, W., Takács, A., Aradi, L., Sandil, S., Dobosy, P., & Záray, G. (2022). Comparison of freshwater mussels Unio tumidus and Unio crassus as biomonitors of microplastic contamination of Tisza River (Hungary). Environments, 9(10), 122.

- Amornrut, C., Toida, T., Imanari, T., Woo, E. R., Park, H., Linhardt, R.,... & Kim, Y. S. (1999). A new sulfated β-galactan from clams with anti-HIV activity. Carbohydrate research, 321(1-2), 121-127.

- Anthony, J. L., Downing, J. A. (2001). Exploitation trajectory of a declining fauna a century of freshwater mussel fisheries in North America. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 58(10), 2071–2090. [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, M., Garg, H., Ajithkumar, T., & Shanmugam, A. (2009). Antiproliferative heparin (glycosaminoglycans) isolated from giant clam (Tridacna maxima) and green mussel (Perna viridis). African journal of biotechnology, 8(10).

- Auclair, J., Turcotte, P., Gagnon, C., Peyrot, C., Wilkinson, K. J., & Gagné, F. (2020). Toxicological effects of inorganic nanoparticle mixtures in freshwater mussels. Environments, 7(12), 109.

- Augspurger, T., Keller, A. E., Black, M. C., Cope, W. G., & Dwyer, F. J. (2003). Water quality guidance for protection of freshwater mussels (Unionidae) from ammonia exposure. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 22(11), 2569–2575. [CrossRef]

- Augspurger, T., Keller, A. E., Black, M. C., Cope, W. G., & Dwyer, F. J. (2003). Water quality guidance for the protection of freshwater mussels (Unionidae) from ammonia exposure. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 22(11), 2569-2575.

- Baldigo, B. P., Sporn, L. A., George, S. D., & Ball, J. A. (2017). Assessment of freshwater mussel health using physical, chemical, and biological indicators in the Upper Delaware River Basin, New York. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 189(9), 459.

- Bauer, H. M., Laporte, J., Haberer, C., Michel, C., & Van Vliet, M. (2016). Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in the Seine River basin: Occurrence, bioaccumulation potential and risk to aquatic organisms. Science of the Total Environment, 542, 1-9.

- Belamy, T., Legeay, A., Etcheverria, B., Cordier, M. A., Gourves, P. Y., & Baudrimont, M. (2020). Acute toxicity of sodium chloride, nitrates, ortho-phosphates, cadmium, arsenic and aluminum for juveniles of the freshwater pearl mussel: Margaritifera margaritifera (L. 1758). Environments, 7(6), 48.

- Blaise, C., Gagné, F., Pellerin, J., Hansen, P. D., & Trottier, S. (2002). Molluscan shellfish biomarker study of the Quebec harbor dredging project. Environmental Toxicology, 17(3), 170-186.

- Bogan, A. E. (2008). Global diversity of freshwater mussels (Mollusca, Bivalvia) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia, 595(1), 139–147. [CrossRef]

- Buddensiek, V., Engel, H., Wachtler, K., & Wacker, K. (1993). Studies on the chemistry of artificial river water suitable for rearing young freshwater pearl mussels (Margaritifera margaritifera L.). Archiv für Hydrobiologie, 127(1), 87-107.

- Buerge, I. J., Poiger, T., Müller, M. D., & Buser, H. R. (2003). Caffeine, an anthropogenic marker for wastewater contamination of surface waters. Environmental Science & Technology, 37(4), 691-700.

- Chakrabortya, I., Royb, S., Ghoshc, S., Ghoshb, M., Mukherjeed, D. C., & Sarkar, D. (2017). Solvent selection in extraction of bioactive and therapeutic components from Indian fresh water mussel Lamellidens marginalis. J. Indian Chem. Soc, 94, 993-1008.

- Chandra, S., & Chaloupka, F. J. (2003). Seasonality in cigarette sales: Patterns and implications for tobacco control. Tobacco Control, 12(1), 105-110.

- Chen, Y.-C., Lin, C.-L., Li, C.-T., and Hwang, D.-F. (2015). Structural Transformation of Oyster, Hard Clam, and Sea Urchin Shells after Calcination and Their Antibacterial Activity against Foodborne Microorganisms. Fish. Sci. 81 (4), 787–794. doi:10.1007/s12562-015-0892-5.

- Choi, J.-S., Lee, H.-J., Jin, S.-K., Lee, H.-J., and Choi, Y.-I. (2014). Effect of Oyster Shell Calcium Powder on the Quality of Restructured Pork Ham. Korean J. Food Sci. Animal Resour. 34, 372–377. doi:10.5851/kosfa.2014. 34.3.372.

- Claassen, C. (1994). Shells. Cambridge University Press.

- Cope, W. G., et al. (2008). Advances in freshwater mussel ecotoxicology. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 27(5), 1005–1012. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z., Zhang, H., Zhang, Y., & Wang, H. (2009). Chemical properties and immunostimulatory activity of a water-soluble polysaccharide from the clam of Hyriopsis cumingii Lea. Carbohydrate Polymers, 77(2), 365-369.

- Danellakis, D., Ntaikou, I., Kornaros, M., & Dailianis, S. (2011). Olive oil mill wastewater toxicity in the marine environment: alterations of stress indices in tissues of mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis. Aquatic Toxicology, 101(2), 358-366.

- Daughton, C. G. (2001). Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in the environment: overarching issues and overview.

- de Solla, S. R., Gilroy, È., Klinck, J., King, L. E., McInnis, R., Struger, J., & Backus, S. (2016). Bioaccumulation of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in wild and caged freshwater mussels. Chemosphere, 146, 486-496.

- Dhodapkar, R. S., & Gandhi, K. N. (2019). Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in aquatic environment: chemicals of emerging concern?. In Pharmaceuticals and personal care products: waste management and treatment technology (pp. 63-85). Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Du, T. T., Cheng, Y., and Zhong, C. C. (2014). Structure modification and research on antitumor activity of mussel polysaccharide. Journal of Zhejiang Ocean University, 2014(4): 354-357.

- Fan QiaoYun, F. Q., Li ChaoPin, L. C., Xu LiFa, X. L., & Wang KeXia, W. K. (2012). Antiviral effect of scallop polysaccharide on duck Hepatitis B virus.

- Farris, J. L., & Van Hassel, J. H. (2007). Freshwater bivalve ecotoxicology. CRC Press.

- Farris, J. L., Van Hassel, J. H., & Newton, T. J. (1988). Biomonitoring with freshwater mussels. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 7(4), 295-307.

- Feng, X., Jiang, S., Zhang, F., Wang, R., Zhang, T., Zhao, Y., & Zeng, M. (2021). Extraction and characterization of matrix protein from pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigs) shell and its anti-osteoporosis properties in vitro and in vivo. Food & Function, 12(19), 9066-9076.

- Galbraith, H. S., Spooner, D. E., & Vaughn, C. C. (2008). Status of rare and endangered freshwater mussels in Southeastern Oklahoma. Southwestern Naturalist, 53(1), 45–50. [CrossRef]

- Gatenby Catherine and Richards Holly, “Freshwater mussels and fish: a timeless love affair | U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.” Accessed: Oct. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.fws.gov/story/2023-05/freshwater-mussels-and-fish-timeless-love-affair.

- Geist, J. (2010). Strategies for the conservation of endangered freshwater pearl mussels (Margaritifera margaritifera L.) a synthesis of Conservation Genetics and Ecology. Hydrobiologia, 644(1), 69–88. [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. (2000). Persistence and Bioaccumulation Regulations. Canada Gazette Part II, 134(7), 607-612.

- Gutierrez, J. L., Jones, C. G., Strayer, D. L., & Iribarne, O. O. (2003). Mollusks as ecosystem engineers the role of shell production in aquatic habitats. Oikos, 101(1), 79–90. [CrossRef]

- Haag, W. R. (2009). Extreme longevity in freshwater mussels revisited: sources of bias in age estimates derived from mark–recapture experiments. Freshwater Biology, 54(7), 1474-1486.

- Haag, W. R. (2012). North American freshwater mussels natural history, ecology, and conservation. Cambridge University Press.

- Haag, W. R., & Warren, M. L. (2008). Effects of severe drought on freshwater mussel assemblages. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 137(4), 1165–1178. [CrossRef]

- Haag, W. R., & Williams, J. D. (2014). Biodiversity on the brink an assessment of conservation strategies for North American freshwater mussels. Hydrobiologia, 735(1), 45–60. [CrossRef]

- Haag, W. R., & Williams, J. D. (2014). Monitoring integrative and practical approaches for evaluating conservation status and management of freshwater mussels (Bivalvia Unionidae). Freshwater Mollusk Biology and Conservation, 17(1), 17–28. [CrossRef]

- He, N., Yang, X., Jiao, Y., Tian, L., & Zhao, Y. (2012). Characterisation of antioxidant and antiproliferative acidic polysaccharides from Chinese wolfberry fruits. Food Chemistry, 133(3), 978-989.

- He, N., Yang, X., Jiao, Y., Tian, L., & Zhao, Y. (2012). Characterisation of antioxidant and antiproliferative acidic polysaccharides from Chinese wolfberry fruits. Food Chemistry, 133(3), 978-989.

- Henderson, N. D., & Christian, A. D. (2022). Freshwater invertebrate assemblage composition and water quality assessment of an urban coastal watershed in the context of land-use land-cover and reach-scale physical habitat. Ecologies, 3(3), 376-394.

- Heydari, S., Pourashouri, P., Shabanpour, B., Shamsabadi, F. T., & Arabi, M. S. (2024). Evaluation of Freshwater Mussel (Anodonta cygnea) Protein Hydrolysates in Terms of Antibacterial Activity and Functional Properties. Waste and Biomass Valorization, 15(7), 4279-4290.

- Hossain, A., Bhattacharyya, S. R., & Aditya, G. (2015). Biosorption of cadmium by waste shell dust of fresh water mussel Lamellidens marginalis: implications for metal bioremediation. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 3(1), 1-8.

- Hou, L., Wang, Q. K., He, Y. H., Ren, D. D., Song, Y. F., Jiang, X. D., and Li, L. D. (2014). The extraction of oyster polysaccharide and its hepatoprotective effect against alcohol-induced hepatic injury in mice. Science & Technology of Food Industry, 35(22): 356.

- Howard, J. K., & Cuffey, K. M. (2003). Freshwater mussels in a California North Coast Range river: Occurrence, distribution, and controls. Journal of the North American Benthological Society, 22(1), 63-77.

- Howard, J. K., & Cuffey, K. M. (2006). The functional role of native freshwater mussels in the fluvial benthic environment. Freshwater Biology, 51(3), 460–474. [CrossRef]

- Hyung, J. H., Ahn, C. B., & Je, J. Y. (2018). Blue mussel (Mytilus edulis) protein hydrolysate promotes mouse mesenchymal stem cell differentiation into osteoblasts through up-regulation of bone morphogenetic protein. Food Chemistry, 242, 156-161.

- Keller, A. E., & Zam, S. G. (1991). The acute toxicity of selected metals to the freshwater mussel, Anodonta imbecillis, Ceriodaphnia dubia, and Pimephales promelas. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 10(8), 1139–1147. [CrossRef]

- Lemos, P., Silva, P., Sousa, C. A., & Duarte, A. J. (2024). Polluted Rivers—A Case Study in Porto, Portugal. Ecologies, 5(2), 188-197.

- Li, J. B., Yuan, X. F., and Hou, G. (2009). Effects of mussel polysaccharide on alcoholic hepatic injury in mice. Food Science & Technology, 2009(4): 188-190.

- Liang, H., Zhou, B., Li, J., Pei, Y., & Li, B. (2016). Coordination-driven multilayer of phosvitin-polyphenol functional nanofibrous membranes: antioxidant and biomineralization applications for tissue engineering. RSC advances, 6(101), 98935-98944.

- Linehan, L.G., T.P. O’Connor and G. Burnell: Seasonal variation in the chemical composition and fatty acid profile of Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas). Food Chem., 64, 211-214 (1999).

- Livingstone, D. R., Chipman, J. K., Lowe, D. M., Minier, C., & Pipe, R. K. (2000). Development of biomarkers to detect the effects of organic pollution on aquatic invertebrates: recent molecular, genotoxic, cellular and immunological studies on the common mussel (Mytilus edulis L.) and other mytilids. International Journal of Environment and Pollution, 13(1-6), 56-91.

- Lopes-Lima, M., et al. (2017). Conservation status of freshwater mussels in Europe state of the art and future challenges. Biological Reviews, 92(1), 572–607. [CrossRef]

- Lydeard, C., & Mayden, R. L. (1995). A diverse and endangered aquatic ecosystem of the Southeast United States. Conservation Biology, 9(4), 800–805. [CrossRef]

- Matsue, H., Takaya, Y., Uchisawa, H., Naraoka, T., Okuzaki, B. I., Narumi, F.,... & Sasaki, J. I. (1997). Antitumor peptidoglycan with new carbohydrate structure from squid Ink. In Food Factors for Cancer Prevention (pp. 331-336). Springer Japan.

- McCall, P. L., & Tevesz, M. J. S. (1982). The effects of benthos on physical properties of freshwater sediments. In McCall, P. L., & Tevesz, M. J. S. (Eds.), Animal-sediment relations the biogenic alteration of sediments (pp. 105–176). Springer.

- Metcalfe, C. D., Chu, S., Judt, C., Li, H., Oakes, K. D., Servos, M. R., & Andrews, D. M. (2010). Antidepressants and their metabolites in municipal wastewater, and downstream exposure in an urban watershed. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 29(1), 79-89.

- Meyer, B.J., N.J. Mann, J.L. Lewis, G.C. Milligan, A.J. Sinclair and P.R. Howe: Dietary intakes and food sources of omega-6 and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Lipids, 38, 391-398 (2003).

- Miller, A. K., Reed, S. M., & Huffnagle, K. (2017). Microplastic ingestion by freshwater mussels in the Laurentian Great Lakes: Implications for ecological health and water quality monitoring. Environmental Pollution, 225, 52-59.

- Miyamoto, H., Miyashita, T., Okushima, M., Nakano, S., Morita, T., & Matsushiro, A. (1996). A carbonic anhydrase from the nacreous layer in oyster pearls. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 93(18), 9657-9660.

- Modesto, V., Ilarri, M., Souza, A. T., Lopes-Lima, M., Douda, K., Clavero, M., & Sousa, R. (2018). Fish and mussels: importance of fish for freshwater mussel conservation. Fish and Fisheries, 19(2), 244-259.

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M.,... & Prisma-P Group. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic reviews, 4, 1-9.

- Naimo, T. J. (1995). A review of the effects of heavy metals on freshwater mussels. Ecotoxicology, 4(6), 341–362. [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. (2008). Hydrology, ecology, and fishes of the Klamath River Basin. The National Academies Press.

- Natural and Cultured Pearls Market Size, Share, Scope, Trends And Forecast 2030. (2024, July). Verified Market Reports. https://www.verifiedmarketreports.com/product/natural-and-cultured-pearls-market-size-and-forecast/.

- Newton, T. J., & Bartsch, M. R. (2007). Lethal and sublethal effects of ammonia to juvenile Lampsilis mussels (Unionidae) in sediment and water-only exposures. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 26(10), 2057–2065. [CrossRef]

- Pipe, R. K., & Coles, J. A. (1995). Environmental contaminants influencing immunefunction in marine bivalve molluscs. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 5(8), 581-595.

- Ricciardi, A., Neves, R. J., & Rasmussen, J. B. (1998). Impending extinctions of North American freshwater mussels (Unionoida) following the zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha) invasion. Journal of Animal Ecology, 67(4), 613–619. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J. S., & Béraud, E. (2014). Effects of riparian forest harvest on streams a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Ecology, 51(6), 1712–1721. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, K., Park, K., Park, K., and Seo, J. (2019). Oyster Shell Disposal: Potential as a Novel Ecofriendly Antimicrobial Agent for Packaging : a Mini Review. Korean. J. packag. Sci. Technol. 25, 57–62. doi:10.20909/kopast.2019.25.2.57.

- Song, S. Y., Sun, L. M., Zhu, B. W., Niu, H. L., and Yang, J. F. (2012). Antioxidant and immunomodulating activities of polysaccharide from scallop gonad. Food Science, 33(5): 248-251.

- Song, S. Y., Sun, L. M., Zhu, B. W., Niu, H. L., and Yang, J. F. (2012). Antioxidant and immunomodulating activities of polysaccharide from scallop gonad. Food Science, 33(5): 248-251.

- Sonowal, J., & Kardong, D. (2020). Nutritional evaluation of freshwater bivalve, Lamellidens spp. from the upper Brahmaputra basin, Assam with special reference to dietary essential amino acids, omega fatty acids and minerals. Journal of Environmental Biology, 41(4), 931-941.

- Spooner, D. E., & Vaughn, C. C. (2006). Context-dependent effects of freshwater mussels on stream benthic communities. Freshwater Biology, 51(6), 1016–1024. [CrossRef]

- Strayer, D. L. (1999). Effects of alien species on freshwater mollusks in North America. Journal of the North American Benthological Society, 18(1), 74–98. [CrossRef]

- Strayer, D. L. (2014). Understanding how nutrient cycles and freshwater mussels (Unionoida) affect each other. Hydrobiologia, 735(1), 277–292. [CrossRef]

- Strayer, D. L., & Malcom, H. M. (2007). Shell decay rates of native and alien freshwater bivalves and implications for habitat engineering. Freshwater Biology, 52(8), 1611–1617. [CrossRef]

- Strayer, D. L., & Smith, D. R. (2003). A guide to sampling freshwater mussel populations. American Fisheries Society.

- Strayer, D. L., Caraco, N. F., Cole, J. J., Findlay, S., & Pace, M. L. (1999). Transformation of freshwater ecosystems by bivalves: A case study of zebra mussels in the Hudson River. BioScience, 49(1), 19-27.

- Strayer, D. L., Dudgeon, D. (2010). Freshwater biodiversity conservation recent progress and future challenges. Journal of the North American Benthological Society, 29(1), 344–358. [CrossRef]

- Sun, F., & Liu, S. (2003). Effects of glycosaminoglycan from scallop skirt on foam cell formation and its function. Journal of Medical Postgraduates.

- Tan, K., Lu, S. Y., Tan, K., Ransangan, J., Cai, X., & Cheong, K. L. (2023). Bioactivity of polysaccharides derived from bivalves. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 126096.

- Tat Wai, K., O’Sullivan, A. D., & Bello-Mendoza, R. (2024). Nitrogen and Phosphorus Removal from Wastewater Using Calcareous Waste Shells—A Systematic Literature Review. Environments, 11(6), 119.

- Ulagesan, S., Krishnan, S., Nam, T. J., & Choi, Y. H. (2022). A review of bioactive compounds in oyster shell and tissues. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 10, 913839.

- Upadhyay, A., Thiyagarajan, V., and Thiyagarajan, V. (2016). Proteomic Characterization of Oyster Shell Organic Matrix Proteins (OMP). Bioinformation 12, 266–278. doi:10.6026/97320630012266.

- Vaughn, C. C. (2018). Ecosystem services provided by freshwater mussels. Hydrobiologia, 810(1), 15–27. [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, C. C., & Hakenkamp, C. C. (2001). The functional role of burrowing bivalves in freshwater ecosystems. Freshwater Biology, 46(11), 1431–1446. [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, C. C., & Spooner, D. E. (2006). Unionid mussels influence macroinvertebrate assemblage structure in streams. Journal of the North American Benthological Society, 25(3), 691–700. [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, C. C., Nichols, S. J., & Spooner, D. E. (2008). Community and foodweb ecology of freshwater mussels. Journal of the North American Benthological Society, 27(2), 409-423.

- Wang, H. T., Liu, S., Ju, C. X., and Yu, N. (2006). Study in the protection effects of oyster glycosaminoglycan on vascular endothelial cell injury Progress in Modern Biomedicine, 6(9): 33-35.

- Wang, L. C., Di, L. Q., Li, J. S., Hu, L. H., Cheng, J. M., & Wu, H. (2019). Elaboration in type, primary structure, and bioactivity of polysaccharides derived from mollusks. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 59(7), 1091-1114.

- Watters, G. T. (2000). Freshwater mussels and water quality a review of the effects of hydrologic and instream habitat alterations. Proceedings of the First Freshwater Mollusk Conservation Society Symposium, 261–274.

- Williams, J. D., Warren, M. L., Cummings, K. S., Harris, J. L., & Neves, R. J. (1993). Conservation status of freshwater mussels of the United States and Canada. Fisheries, 18(9), 6–22. [CrossRef]

- Woo, E. R., Kim, W. S., & Kim, Y. S. (2001). Virus-cell fusion inhibitory activity for the polysaccharides from various Korean edible clams. Archives of pharmacal research, 24, 514-517.

- Xing, R., Qin, Y., Guan, X., Liu, S., Yu, H., and Li, P. (2013). Comparison of Antifungal Activities of Scallop Shell, Oyster Shell and Their Pyrolyzed Products. Egypt. J. Aquatic Res. 39, 83–90. doi:10.1016/j.ejar.2013.07.003.

- Yin, H. L., Yuan, M. A., Wang, L., Sun, Y. M., Yu, Y. H., and Zhu, B. W. (2007). The extraction of and scavenging hydroxyl free radicals by scallop viscus polysaccharide. Fisheries Science, 26(5): 255-258.

- Yu, N., Liu, S., and Han, J. J. (2008). The deppressive effect of glycosaminoglycan from scallop on type-I herpes simplex virus. Acta Academiae Medicinae Qingdao Universitatis, 44(2): 111-113.

- Yuan, Q., Zhao, L., Cha, Q., Sun, Y., Ye, H., & Zeng, X. (2015). Structural characterization and immunostimulatory activity of a homogeneous polysaccharide from Sinonovacula constricta. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 63(36), 7986-7994.

- Zhang, D., Wang, C., Wu, H., Xie, J., Du, L., Xia, Z.,... & Wei, D. (2013). Three sulphated polysaccharides isolated from the mucilage of mud snail, Bullacta exarata philippi: Characterization and antitumour activity. Food chemistry, 138(1), 306-314.

- Zhang, J., Liu, S., Su, Y., and Yang, S. G. (2006). Effects of scallp skirt glycosaminoglycan on function of vascular endothelial cells with oxidiation damages in culture. Chinese Pharmaceutical Journal, 41(13): 990-993.

- Zhang, L., Liu, W., Han, B., Sun, J., & Wang, D. (2008). Isolation and characterization of antitumor polysaccharides from the marine mollusk Ruditapes philippinarum. European Food Research and Technology, 227, 103-110.

- Zhao, J., Zhou, D. Y., Yang, J. F., Song, S., Zhang, T., Zhu, C.,... & Zhu, B. W. (2016). Effects of abalone (Haliotis discus hannai Ino) gonad polysaccharides on cholecystokinin release in STC-1 cells and its signaling mechanism. Carbohydrate polymers, 151, 268-273.

- Zhu, B. W., Zhou, D. Y., Li, T., Yan, S., Yang, J. F., Li, D. M.,... & Murata, Y. (2010). Chemical composition and free radical scavenging activities of a sulphated polysaccharide extracted from abalone gonad (Haliotis Discus Hannai Ino). Food Chemistry, 121(3), 712-718.

- Zieritz, A., & Lopes-Lima, M. (2018). Biological diversity of freshwater mussels (Bivalvia Unionida) in Southeast Asia and Africa. In Bogan, A. E., et al. (Eds.), Freshwater mollusks of the world a distribution atlas. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).