1. Introduction

The testis plays a central role in spermatogenesis and androgen synthesis, which provides a precisely coordinated spermatogenesis as the foundation for male fertility. In mammals, spermatogenesis refers to A continuous process of germ cell development from spermatogonia on the basement membrane to the haploid spermatozoa [

1]. Spermatogenesis is tightly controlled by testicular somatic cells that precisely regulate the microenvironment and androgen production in testis. Leydig cells are responsible for androgen synthesis by the activity of the Luteinizing hormone receptor (Lhcgr) in response to the Luteinizing hormone (LH) [

2]. Androgen can bind to androgen receptor (AR) produced by Sertoli cells and induce the secretion of multiple energy substances and pivotal niche factors for regulating spermatogonia proliferation, spermatocyte meiosis, and spermiogenesis [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. It has been proven that androgen is crucial for the proper fate determination of germ cells [

8,

9,

10]. In addition, the testicular macrophage as a mainly immune cell population in testis, can prevent pro-inflammatory response from the testicular microenvironment to ensure the progress of steroidogenesis [

11]. In return, androgen is also known to suppress immune cell activities and maintain testicular homeostasis [

12,

13,

14,

15].

The effects of androgen deficiency and excess on gonad function and fertility is one of the popular studies in animal reproduction. Studies conducted in rats showed that exposure to endocrine-disrupting compounds (EDCs) leads to androgen reduction and immune activation in the testes [

16]. Abnormal androgen and AR action can cause a variety of reproduction disorders, including polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) in females and prostate cancer (PCa) in males[

12]. Previous study verified that ovarian fibrosis in PCOS and PCa development dependent on androgen level and AR signaling activation [

17,

18]. Blocking the function of androgen serves as the cornerstone of treatment, because the absence of androgen makes AR inactive and sequestered in the cytoplasm[

19,

20,

21]. On the other hand, androgen signaling is a key factor of anti-tumor immunity by suppressing T-cell immunity [

22]. The inhibition of AR directly improves T cell function and IFNγ production [

21]. Those studies indicated that androgen signaling has a key role in maintaining spermatogenesis and immunity function in the testis.

The ginger species may have potential treatment effects on androgen-driven disease. Anti-androgen drugs exhibit sub-optimal efficacy and immune tolerance by inhibiting AR function [

23]. Therefore, many researchers are keen to try ‘natural’ alternative materials to reduce the side effects of synthetic compounds [

24]. For example, curcumin and gingerol isolated from usual ginger species were shown capable of affecting intracellular testosterone function and exhibiting anti-PCa properties by interrupting androgen receptor signaling [

25,

26,

27]. In addition, curcumin exhibits promising potential in clinical studies and has been used for the remission of a range of diseases [

28,

29]. However, whether ginger spices affect the process of spermatogenesis is largely unknown.

Zingiber mioga (

Z. mioga namely as ranghe in China, yangha in Korea, myoga in Japan) is a traditional oriental medicine and edible spice that belongs to the ginger family [

30].

Z. mioga is usually used to treat inflammation, rheumatic disorders and gastrointestinal discomforts because of its antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties [

31,

32]. Previous studies reported that

Z. mioga water (ZMW) significantly decreased lipid synthesis and improved high-fat diet (HFD)-induced hepatic inflammation [

30,

33]. In addition,

Z. mioga flower buds also have many beneficial effects, including anticancer and antioxidant effects [

34,

35]. However, the effects of

Z. mioga on gonadal function and androgen production have not been confirmed.

In this study, we fed Z. mioga to male mice for 3 weeks to study the effects of Z. mioga on testicular development and spermatogenesis. RNA-seq and qRT-PCR experiments were employed to examine the change in testicular gene expression caused by Z. mioga feeding. This study is helpful in revealing the potential anti-androgen mechanism of ginger species and provides a reference for understanding the biological function and the rational use of Z. mioga.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Z. mioga Collection and Preparation

Z. mioga Roscoe flower buds were collected from a traditional market in Anhui Province (South of China) in September 2022 and frozen saved at West Anhui University. The frozen plants were dried in an oven at 50℃, crushed using a wall breaker, and filtered by using a 60-mesh sieve. The filter powder was stored at 4℃ and subsequently dissolved in corn oil. Feeding, testis tissue collection, and transcriptome detection of the mice were performed from Jan 20, 2023 to May 30, 2023.

2.2. Treatment of Animals

All animals used in the experiment received approval by the Ethics Committee of the West Anhui University (2023 Scientific Research Ethics Review; Approval No. 202301002; Approval date on Jan 6, 2023). CD-1 mice were purchased from the Charles River Laboratory Animal Centre (Beijing, China) and housed in a controlled environment with food and water ad libitum. The male mice, 4-6 weeks of age, were randomly divided into two groups, the treatment group received

Z. mioga powder dissolving in corn oil of daily oral doses of 250mg/kg body weight and the control group kept in the same condition and feeding with vehicles for 3 weeks (n=4, each group). The body weight of the mice was measured once a week. Euthanized when normal body weight, rough hair and eyelid inflammation were observed in the treatment group, which as humane endpoints in this study (

Figure 1A).

2.3. Testis Tissue Collection and RNA Extraction

After consistently feeding Z. mioga for 3 weeks, the control and treatment male mice were weighed and euthanized with 3% isoflurane, then were sacrificed via cervical dislocation(n=3, each group). Animal death was confirmed through the stoppage of breathing. Testes and epididymis were immediately removed from the body and weighed. For total RNA isolates, testis tissues were placed into 2mL sterile centrifuge tubes and dropped in liquid nitrogen and then stored at -80℃ used for RNA-seq analysis. Briefly, total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) from frozen testis tissue of the control and Z. mioga fed group. Testis tissue was grinded in liquid nitrogen and collected into 1.5 mL sterile centrifuge tubes, and 1mL Trizol was added to each testis and then incubated at room temperature (RT) for 5 min. Then 0.2 mL chloroform was added and the mixture was for 15 sec. After incubation in RT for 5 min and centrifugation at 4℃ for 10 min, the upper water phase was absorbed and transferred to a clean centrifuge tube and added to isopropyl alcohol in equal volume. Then mixture well and incubate in RT for 20 min, centrifuge at 12000rpm at 4°C for 10 min and discard the supernatant. 1mL 75% ethanol was added for washing precipitation and centrifuge at 12000rpm at 4°C for 3min. After discard the supernatant and dry at RT for 10 minutes. Finally, the total RNA was dissolved in 30μL RNase-free ddH2O and stored at -80°C. After that, the RNA was sent to Shanghai Sangon Biotech for construction library, and after quality detection, an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 high-throughput sequencer was used for sequencing.

2.4. RNA-Seq and Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) Analysis

First, the raw reads of sequencing were evaluated by FastQC, and then Trimmomatic was used to filter the low-quality sequences to obtain relatively accurate and effective data. Then, the mouse reference genome was used as the reference sequence, HISAT2 was used to compare the valid data of the sample to the mouse reference genome for statistical mapping information, and RSeQC was used to remove duplicate reads. Subsequently, Qualimap was used to calculate the proportion of raw reads in reference genome structures to obtain count reads, and StringTie was used to further quantify the expression value of each transcript through Transcripts Per Million (TPM) conversion of count reads. Finally, DESeq was used to obtain differential expression genes (DEGs), and selected DEGs were based on |log2 FoldChange| ≥1 and

q< 0.05 in a comparison. The DEGs heatmap and volcano plot were obtained by

http://www.bioinformatics.com.cn, an online platform for RNA-seq data visualization. DEGs were then subjected to enrichment analysis of Gene Ontology (GO) functions and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways.

2.5. Sperm Concentration Detection

To conduct semen quality analysis, fresh cauda epididymidis tissue was placed in 1 mL 0.9% NaCl and cut into pieces using ophthalmic scissors, then put in a 37℃ incubator for 5 min to fully release the sperm for further analyzing sperm concentration. Briefly, a 10μL sperm suspension was diluted with 490μL normal saline and mixture, then 10μL loaded into a counting chamber of blood cell count plate and sperm count was analyzed under microscopy. At least 3 biological replicates were conducted in each group (n=3).

2.6. DEGs Validation and Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA concentration and purity were quantified using a SMA4000 Spectrophotometer (Merinton Instrument, Inc), and the sample of A260/A280≥1.8 was used for reverse transcription and qRT-PCR detection. 1μg RNA was transformed to cDNA by using Maxima Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Scientific). The SYBR Green mixture was used in combination with primer pairs (10μM) (Table 1). A QuantStudioTM1 Plus Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) was used to quantify the relative abundance of target transcripts. The optimized parameters for the thermal cycler were as follows: activation at 95℃ for 3 min followed by 45 cycles of 95℃ for 15 sec, and 60℃ for 30 sec. The temperature was then gradually increased (0.5℃/s) to 95℃ to generate the melting curve. β-actin was used as a reference to normalize relative gene expression. The mRNA relative expression levels were calculated using the 2-△△CT method. For each transcript, qRT-PCR was performed in triplicate from 6 different animal samples.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All the quantitative data are presented as mean ± SEM for at least three biological replicates. Differences between control and treatment mice testis were examined using the T-test function of GraphPad Prism 5 (La Jolla, CA, USA). Differences between means were set p < 0.05 as significant.

3. Results

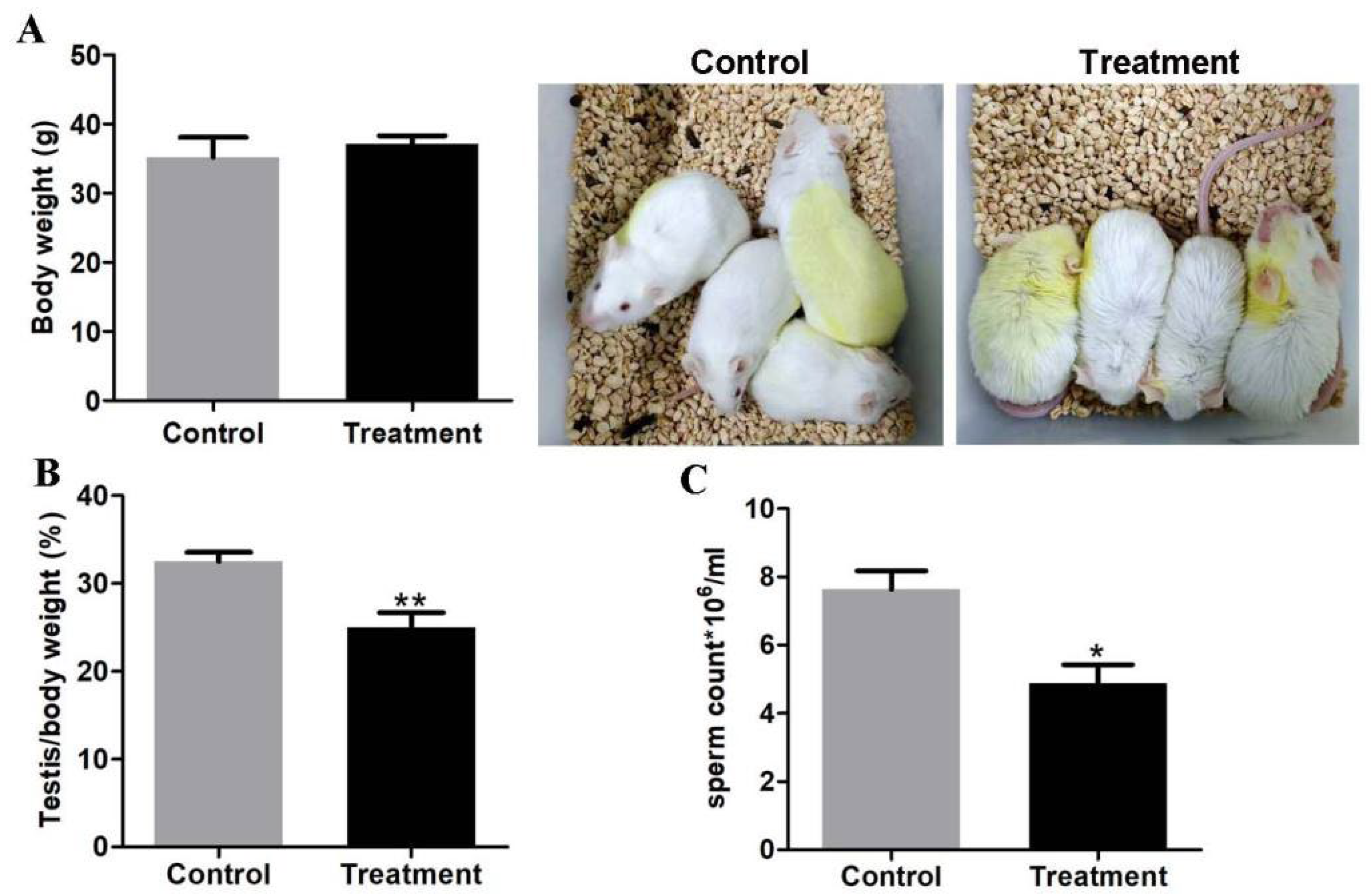

3.1. The Analysis of Testis/Body Ratio and Sperm Concentration in the Control and Treatment Groups

Compared to the control group, body weight did not change (

Figure 1A), but testis/body rate from treatment animals was greatly reduced (25%±0.01

vs 32.5%±0.01,

p < 0.01) (

Figure 1B). A detailed examination of the sperm quantity showed that the sperm concentration of epididymis in the treatment mice was significantly reduced (4.9*10

6/ml±0.6

vs 7.6*10

6/ml±0.6,

p < 0.05) (

Figure 1C). This data revealed that testis developmental and spermatogenesis function were impaired after feeding

Z. mioga.

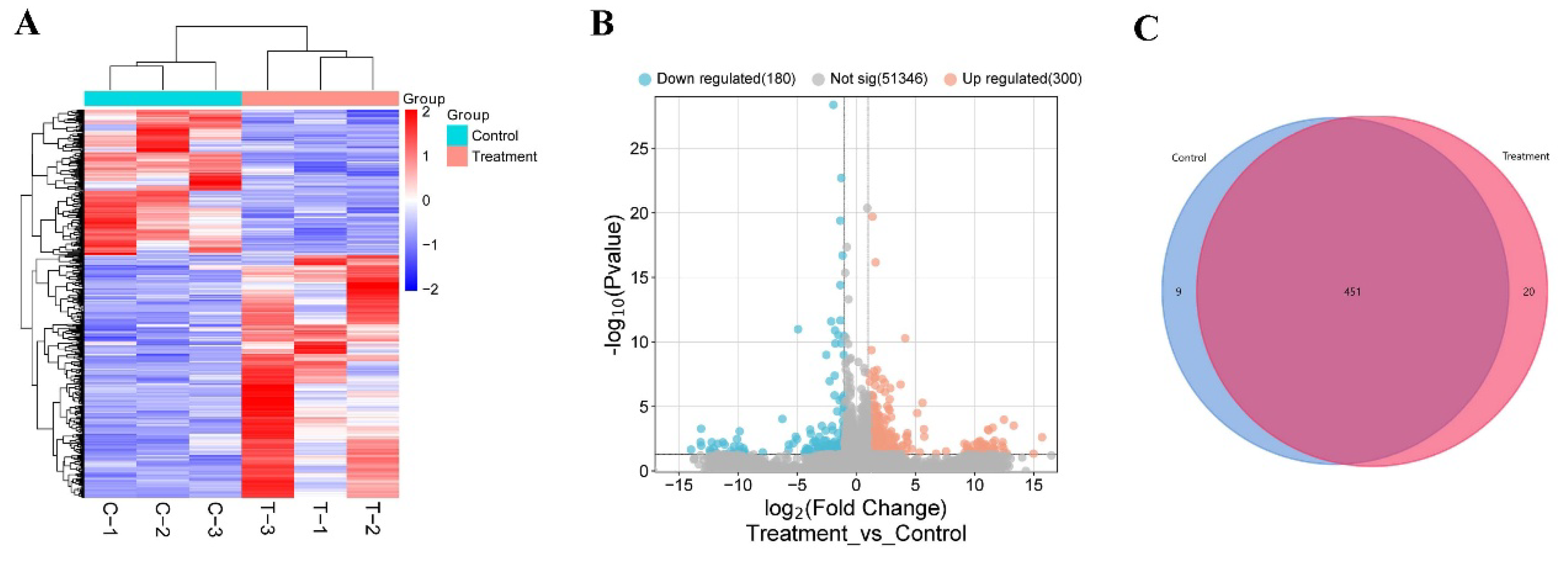

3.2. Change of Testicular Gene Expression Profile Between the Control and Treatment Groups

To detect differences in testicular gene expression between the control and treatment mice, we performed transcriptome sequencing of mouse testes. The testis gene expression profile revealed that 98.12% of raw data were mapped to the mouse reference genome and 94.32% were uniquely mapped (Table 2), and the results showed that the RNA-seq data was reliable and reproducible. Then, the DESeq R package was used for difference analysis. As a result, 480 DEGs were detected between the control and treatment testis (

Figure 2A and

Supplement Table S1), including 300 upregulated genes and 180 downregulated genes (

Figure 2B). Venn Diagram analysis showed 20 DEGs were only expressed in the testis of treatment group, and 9 DEGs were specific expressed in the testis of the control group, and 451 DEGs were expressed in both of testis tissues (

Figure 2C). Transcriptome data revealed that feeding

Z. mioga led to a decrease of sperm count by altering of testis gene expression profile.

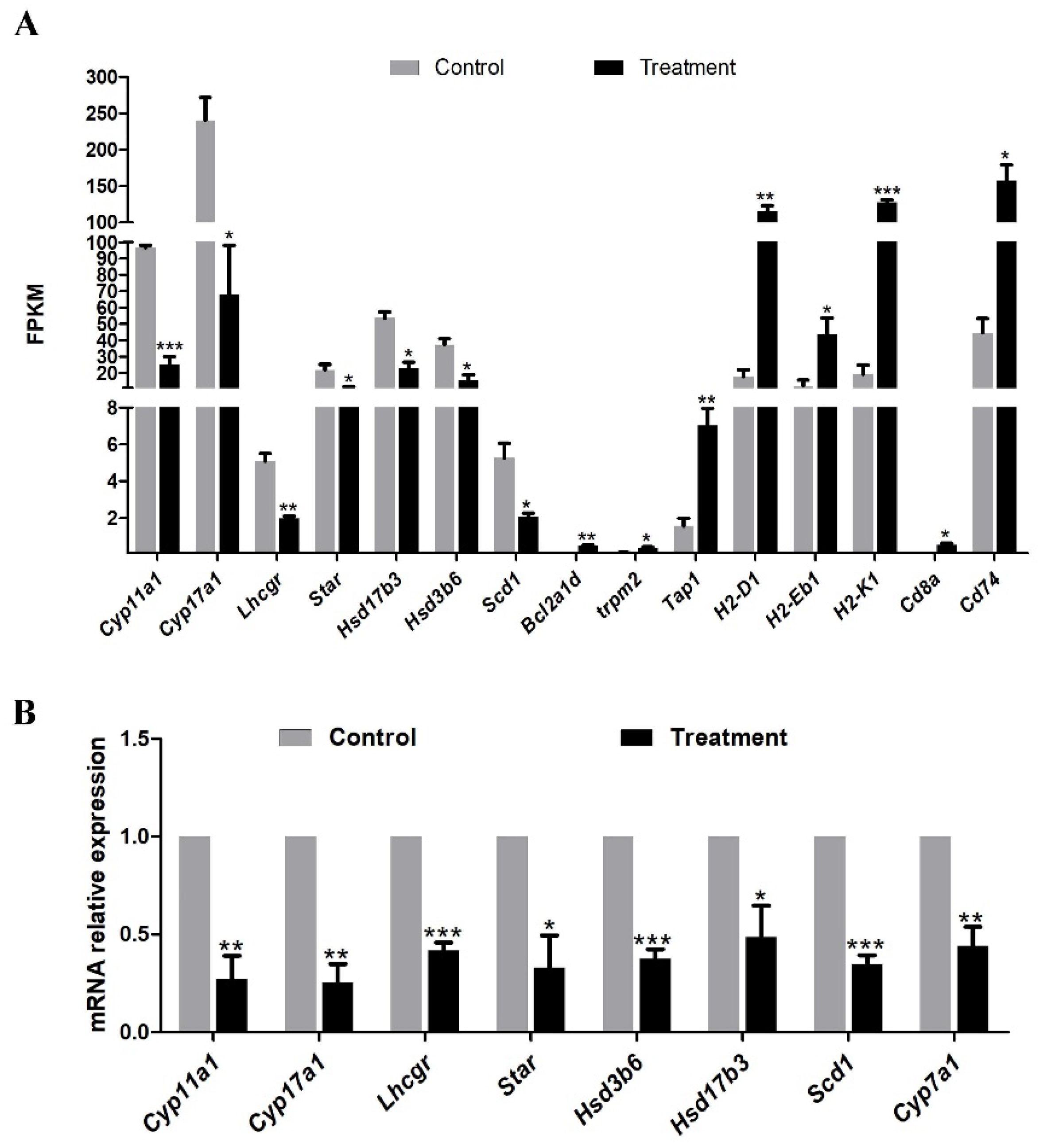

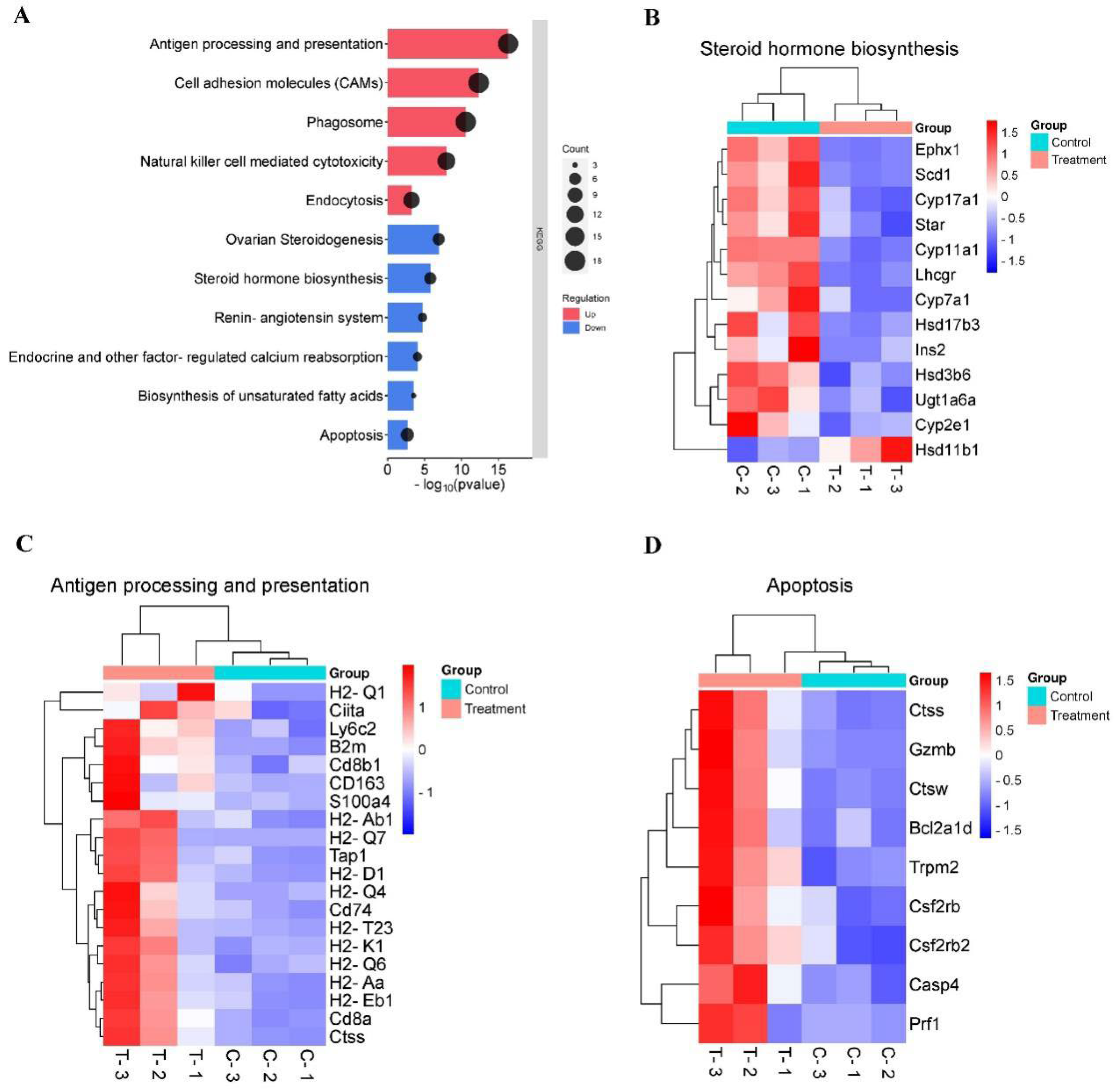

3.3. KEGG Pathway Enrichment of DEGs

KEGG pathway analysis showed that down-regulated DEGs mainly enriched in steroid hormone biosynthesis, and up-regulated DEGs primarily enriched in antigen processing and presentation (

Figure 3A). Notably, among down-regulating genes directly involved in androgen synthesis, including

Scd1,

Star,

Cyp11a1,

Hsd3b6,

Cyp17a1,

Hsd17b3,

Lhcgr, which were down-regulated by 1.34, 1.30, 1.93, 1.27, 1.81, 0.94 and 1.35-fold in testis of the treatment mice (

Figure 3B&4A). Genes that were upregulated in treatment testes included those known to play important roles in the immune system process, such as

Tap1,

H2-D1,

H2-Eb1,

H2-K1,

Cd8a and

Cd74(

Figure 3C&4A). The KEGG analysis results showed that feeding

Z. mioga may impair spermatogenesis and improve immunity function through the downregulation of androgen synthesis-related genes.

3.4. Validation of DEGs in Both of Control and Treatment Group Testis

To further validate the RNA-seq result, 8 DEGs were selected and detected by qRT-PCR. Those selected genes have key functions in the steroidogenesis pathway. The result of qRT-PCR showed that relative expression of

Cyp11a1,

Cyp17a1,

Lhcgr,

Hsd3b6,

Cyp7a1,

Hsd17b3,

Star and

Scd1 were significantly downregulated in testis tissues of the treatment group (

p < 0.05). (

Figure 4B). These results were consistent with RNA-seq data and together these findings revealed that the expression of genes regulating steroidogenesis signaling was changed in mice testis after feeding

Z. mioga.

Figure 4.

DEGs were involved in androgen synthesis and detected by Qrt-PCR in control and Z. mioga fed mice testis. (A) DEGs related to androgen biosynthesis, antigen processing and apoptosis from RNA-Seq. (B) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR validation of androgen synthesis related DEGs in testis from control and Z. mioga feed mice. Data was analyzed by means ± S.E.M. for at least 3 replicates. Significance is represented by one (p < 0.05), two (p < 0.01), and three (p < 0.001) asterisks. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of at least three independent experiments.

Figure 4.

DEGs were involved in androgen synthesis and detected by Qrt-PCR in control and Z. mioga fed mice testis. (A) DEGs related to androgen biosynthesis, antigen processing and apoptosis from RNA-Seq. (B) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR validation of androgen synthesis related DEGs in testis from control and Z. mioga feed mice. Data was analyzed by means ± S.E.M. for at least 3 replicates. Significance is represented by one (p < 0.05), two (p < 0.01), and three (p < 0.001) asterisks. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of at least three independent experiments.

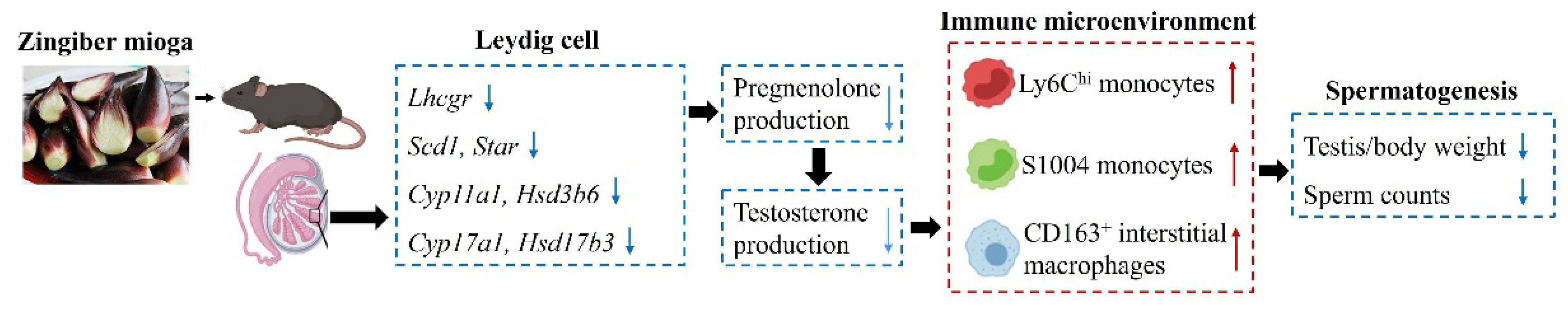

Figure 5.

The mechanism underlying a disturbing immune microenvironment and spermatogenesis by feeding Zingiber mioga in mouse testis. The upward red arrows indicate a significant increase, and the downward blue arrows indicate a significant decrease.

Figure 5.

The mechanism underlying a disturbing immune microenvironment and spermatogenesis by feeding Zingiber mioga in mouse testis. The upward red arrows indicate a significant increase, and the downward blue arrows indicate a significant decrease.

4. Discussion

This study mainly discovered the change of spermatogenesis and testicular expression profile by feeding Z. mioga in male mice. We found that feeding Z. mioga caused a significant reduction in testis/body weight and sperm concentration. A list of genes involved in androgen synthesis and immunity function were affected by feeding Z. mioga. Therefore, Z. mioga affects spermatogenesis and the testicular immune microenvironment by regulating the expression of androgen synthesis genes in mice.

Reduced expression of key enzymes involved in testosterone synthesis is the main cause of impaired spermatogenesis after feeding

Z. mioga. Testosterone as one of the androgen types and is mainly produced in Leydig cells. Cytochrome P450 Family 11 Subfamily A1 (Cyp11a1) is located in mitochondria of Leydig cell and promotes the conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone. The 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD), Cyp17a1, and 17β-HSD3 are found in endoplasmic reticulum and responsible for each intermediate easily and directly move to the next step during the proceeding of testosterone synthesis[

2]. A variety of factors that disturb cholesterol uptake and enzyme function have a great impact on the production of testosterone, including climate[

10], hypoxia[

36], age[

37] and plant extract[

25]. A previous study reported that curcumin from ginger species could decrease testosterone production by down-regulating the expression of steroidogenic acute regulatory proteins (Star), Cyp11a1 and Hsd3b2 [

25]. Our result showed that sperm concentration was significantly reduced in epididymis tubules after feeding

Z. mioga for 3 weeks. In addition, the level of genes promoting testosterone production were significantly decreased by feeding

Z. mioga, including

Scd1,

Star,

Cyp11a1,

Hsd3b6,

Cyp17a1,

Hsd17b3,

Lhcgr. Therefore, we proposed that

Z. mioga can regulate spermatogenesis by influencing testosterone production in testis.

Androgen affects the testicular immune microenvironment resulting in the altered function of testicular macrophages and compromised spermatogenesis. As the largest immune cell population, macrophage is a guardian to combat intracellular bacteria and protect steroidogenesis and the spermatogonial niche, together with Leydig cells [

38,

39]. Testicular macrophages express immunosuppressive M2 phenotype marker genes and play an important role in maintaining the testicular immune-privileged status [

11,

40]. In addition, the unique immunosuppressive phenotype and progesterone synthesis of testicular macrophages seem to be governed by testosterone [

15,

41]. Furthermore, the local feedback machinery between Leydig cells and macrophages regulates testosterone production by promoting progesterone production [

15,

42]. We observed that immunosuppressive M2 macrophage phenotype genes

CD163[

38] were significantly upregulated in treatment group. Hence, we proposed that low androgen-induced accumulation of immunosuppressive M2 macrophages could stimulate androgen synthesis by Leydig cells. Moreover, we found that blood monocyte marker genes

Ly6C and

S100a4 were upregulated along with the low expression of androgen synthesis genes in testis after feeding

Z. mioga. Similar upregulation was found in genes involved in antigen presentation and processing, including

H2D1,

H2Eb1 and

H2K1. This change in gene expression pattern indicates an immunity-activated state[

38] and is mainly responsible for regulating spermatogenesis [

43]. Together, it demonstrates that a low amount of androgen caused by feeding

Z. mioga results in the invasion of blood monocytes into the testes and the secretion of pro-inflammatory factors from macrophages, which ultimately damages spermatogenesis.

RNA-seq data showed that several key genes related to cell death or apoptosis were differentially expressed in testis from control and treatment mice. Trpm2 may increase the susceptibility to cell death by increasing intracellular free calcium concentration [

44], which can be activated by androgen [

45]. In addition, the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 fosters trpm2 activity by inducing higher free Ca

2+ levels and decreasing mitochondrial ROS formation [

46]. Both

bcl-2 and

trpm2 were upregulated in mice fed by

Z. mioga. It implies the potential change of cell cycle and germ cell fate.

In summary, the present study revealed the important affection of Z. mioga on spermatogenesis, androgen synthesis and immunity homeostasis in testis. This study proposed to avoid eating Z. mioga or foods containing Z. mioga in men of reproductive age. In addition, the discovery of underlying regulatory mechanisms of Z. mioga in androgen production and testicular microenvironment would be beneficial to the exploitation of targeted drugs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ruina Zhang and Daolun Yu; data curation, Ruina Zhang and Naifu Chen; formal analysis, Renshu Huang and Yongping Cai; funding acquisiton, Ruina Zhang and Naifu Chen; methodology, Ruina Zhang and Renshu Huang; project administration, Ruina Zhang and Naifu Chen; visualization, Ruina Zhang; writing original draft, Ruina Zhang; writing review & editing, Ruina Zhang and Daolun Yu.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province of China (No.2108085QC136); Ruina Zhang and Daolun Yu were supported by the High-Level Talent Research Start-Up Funds of West Anhui University (No. WGKQ202001009&WGKQ2021031); Ruina Zhang was supported by the Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. WXBSH2020002&2024C862) and Domestic Visiting Program (No. wxxygnfx2023001) of West Anhui University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the West Anhui University (2023 Scientific Research Ethics Review; approval no. 202301002).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

- Smith, L.B. and W.H. Walker. The regulation of spermatogenesis by androgens. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2014, 30, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zirkin, B.R. and V. Papadopoulos. Leydig cells: formation, function, and regulation. Biol Reprod 2018, 99, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.N., H.P. Tao; et al. Ldha-Dependent Metabolic Programs in Sertoli Cells Regulate Spermiogenesis in Mouse Testis. Biology 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinohara, T., K.E. Orwig. Restoration of spermatogenesis in infertile mice by Sertoli cell transplantation. Biol Reprod 2003, 68, 1064–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, T., E. Freinkman. Periodic production of retinoic acid by meiotic and somatic cells coordinates four transitions in mouse spermatogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, E10132–E10141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larose, H., T. Kent; et al. Regulation of meiotic progression by Sertoli-cell androgen signaling. Mol Biol Cell 2020, 31, 2841–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdcraft, R.W. and R.E. Braun. Androgen receptor function is required in Sertoli cells for the terminal differentiation of haploid spermatids. Development 2004, 131, 459–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, M.Y., S.D. Yeh; et al. Differential effects of spermatogenesis and fertility in mice lacking androgen receptor in individual testis cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 18975–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, B.C., M.W. Okuyama. Steroidogenic enzymes, their products and sex steroid receptors during testis development and spermatogenesis in the domestic cat (Felis catus). J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2018, 178, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.J., G.X. Jia; et al. Testosterone-retinoic acid signaling directs spermatogonial differentiation and seasonal spermatogenesis in the Plateau pika (Ochotona curzoniae). Theriogenology 2019, 123, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhardt, A., M. Wang. Microenvironmental signals govern the cellular identity of testicular macrophages. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 2018, 104, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naamneh Elzenaty, R., T. du Toit. Basics of androgen synthesis and action. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2022, 36, 101665. [Google Scholar]

- Gubbels Bupp, M.R. and T.N. Jorgensen. Androgen-Induced Immunosuppression. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioni, B., A. Zaalberg; et al. Androgen receptor signalling in macrophages promotes TREM-1-mediated prostate cancer cell line migration and invasion. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamauchi, S., K. Yamamoto, and K. Ogawa, Testicular Macrophages Produce Progesterone De Novo Promoted by cAMP and Inhibited by M1 Polarization Inducers. Biomedicines 2022, 10.

- Broniowska, Ż., I. Tomczyk; et al. Benzophenone-2 exerts reproductive toxicity in male rats. Reprod Toxicol 2023, 120, 108450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auchus, R.J. and N. Sharifi. Sex Hormones and Prostate Cancer. Annual Review of Medicine 2020, 71, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Z. Zhu; et al. Bromodomain-containing protein 4 activates androgen receptor transcription and promotes ovarian fibrosis in PCOS. Cell Rep 2023, 42, 113090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y., E.C. Bolton. Androgens and androgen receptor signaling in prostate tumorigenesis. J Mol Endocrinol 2015, 54, R15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, K., J.M. McManus. Hormonal Therapy for Prostate Cancer. Endocr Rev 2021, 42, 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X., F. Polesso, C. Wang, A. Sehrawat, R.M. Hawkins, S.E. Murray, et al., Androgen receptor activity in T cells limits checkpoint blockade efficacy. Nature 2022, 606, 791–796. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X., L. Cheng, C. Gao, J. Chen, S. Liao, Y. Zheng, et al., Androgen Signaling Contributes to Sex Differences in Cancer by Inhibiting NF-κB Activation in T Cells and Suppressing Antitumor Immunity. Cancer Res 2023, 83, 906–921. [CrossRef]

- Singaravelu, I., H. Spitz, M. Mahoney, Z. Dong, and N. Kotagiri, Antiandrogen Therapy Radiosensitizes Androgen Receptor-Positive Cancers to (18)F-FDG. J Nucl Med 2022, 63, 1177–1183. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, P. and S. Ramasamy, An update on plant derived anti-androgens. Int J Endocrinol Metab 2012, 10, 497–502. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ide, H., Y. Lu, T. Noguchi, S. Muto, H. Okada, S. Kawato, et al., Modulation of AKR1C2 by curcumin decreases testosterone production in prostate cancer. Cancer Sci 2018, 109, 1230–1238. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.Y., J.E. Lim, and J.H. Hong, Curcumin interrupts the interaction between the androgen receptor and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2010, 13, 343–9. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, Y., S. Prasad, C. Tripathi, M. Singh, J. George, and N. Kalra, In vitro and in vivo modulation of testosterone mediated alterations in apoptosis related proteins by [6]-gingerol. Mol Nutr Food Res 2007, 51, 1492–502. [CrossRef]

- Akaberi, M., A. Sahebkar, and S.A. Emami, Turmeric and Curcumin: From Traditional to Modern Medicine. Adv Exp Med Biol 2021, 1291, 15–39.

- Mollazadeh, H., A.F.G. Cicero, C.N. Blesso, M. Pirro, M. Majeed, and A. Sahebkar, Immune modulation by curcumin: The role of interleukin-10. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2019, 59, 89–101. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.H., J. Ahn, Y.J. Jang, T.Y. Ha, and C.H. Jung, Zingiber mioga reduces weight gain, insulin resistance and hepatic gluconeogenesis in diet-induced obese mice. Exp Ther Med 2016, 12, 369–376. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, N.R., I.S. Shin, C.M. Jeon, J.M. Hong, O.K. Kwon, H.S. Kim, et al., Zingiber mioga (Thunb.) Roscoe attenuates allergic asthma induced by ovalbumin challenge. Mol Med Rep 2015, 12, 4538–4545. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, M., Y. Ozawa, Y. Uda, F. Yamada, Y. Morimitsu, Y. Nakamura, et al., Antimicrobial activities of diterpene dialdehydes, constituents from myoga (Zingiber mioga Roscoe), and their quantitative analysis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2004, 68, 1601–4. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H., D.H. Lee, H.I. Choi, J. Ahn, Y.J. Jang, T.Y. Ha, et al., Synergistic lipid-lowering effects of Zingiber mioga and Hippophae rhamnoides extracts. Exp Ther Med 2020, 20, 2270–2278.

- Miyoshi, N., Y. Nakamura, Y. Ueda, M. Abe, Y. Ozawa, K. Uchida, et al., Dietary ginger constituents, galanals A and B, are potent apoptosis inducers in Human T lymphoma Jurkat cells. Cancer Lett 2003, 199, 113–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.W., A. Murakami, M. Abe, Y. Ozawa, Y. Morimitsu, M.V. Williams, et al., Suppressive effects of mioga ginger and ginger constituents on reactive oxygen and nitrogen species generation, and the expression of inducible pro-inflammatory genes in macrophages. Antioxid Redox Signal 2005, 7, 1621–9.

- Li, S. and Q.E. Yang, Hypobaric hypoxia exposure alters transcriptome in mouse testis and impairs spermatogenesis in offspring. Gene 2022, 823, 146390. [CrossRef]

- Gao, F., G. Li, C. Liu, H. Gao, H. Wang, W. Liu, et al., Autophagy regulates testosterone synthesis by facilitating cholesterol uptake in Leydig cells. J Cell Biol 2018, 217, 2103–2119. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mossadegh-Keller, N., R. Gentek, G. Gimenez, S. Bigot, S. Mailfert, and M.H. Sieweke, Developmental origin and maintenance of distinct testicular macrophage populations. J Exp Med 2017, 214, 2829–2841. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., H. Wang, and P.K. Chu, Enhancing macrophages to combat intracellular bacteria. The Innovation Life 2023, 1, 100027. [CrossRef]

- Mossadegh-Keller, N. and M.H. Sieweke, Testicular macrophages: Guardians of fertility. Cell Immunol 2018, 330, 120–125. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., M. Fijak, H. Hossain, M. Markmann, R.M. Nüsing, G. Lochnit, et al., Characterization of the Micro-Environment of the Testis that Shapes the Phenotype and Function of Testicular Macrophages. The Journal of Immunology 2017, 198, 4327–4340. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becerra-Díaz, M., A.B. Strickland, A. Keselman, and N.M. Heller, Androgen and Androgen Receptor as Enhancers of M2 Macrophage Polarization in Allergic Lung Inflammation. J Immunol 2018, 201, 2923–2933. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M., M. Fijak, H. Hossain, M. Markmann, R.M. Nüsing, G. Lochnit, et al., Characterization of the Micro-Environment of the Testis that Shapes the Phenotype and Function of Testicular Macrophages. J Immunol 2017, 198, 4327–4340. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naziroğlu, M. and A. Lückhoff, A calcium influx pathway regulated separately by oxidative stress and ADP-Ribose in TRPM2 channels: single channel events. Neurochem Res 2008, 33, 1256–62. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, T., T.A. Macey, N. Quillinan, J. Klawitter, A.L. Perraud, R.J. Traystman, et al., Androgen and PARP-1 regulation of TRPM2 channels after ischemic injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013, 33, 1549–55. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klumpp, D., M. Misovic, K. Szteyn, E. Shumilina, J. Rudner, and S.M. Huber, Targeting TRPM2 Channels Impairs Radiation-Induced Cell Cycle Arrest and Fosters Cell Death of T Cell Leukemia Cells in a Bcl-2-Dependent Manner. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 2016, 8026702. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).